|

|

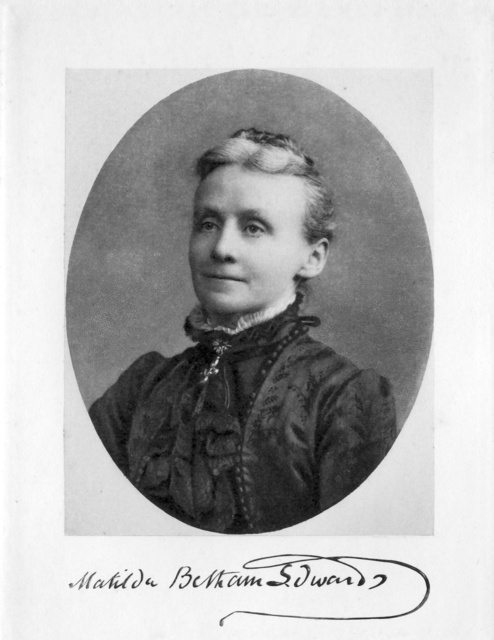

Photographed by Barraud.

MATILDA

BETHAM-EDWARDS

(1836-1919) |

――――♦――――

MATILDA

BETHAM-EDWARDS

was an English novelist, travel writer, Francophile and, overall,

a prolific author.

Born on 4th March, 1836, at Westerfield, Suffolk, she was the

fourth daughter of Edward Edwards (1808-64), a farmer, and Barbara

(1806-48), daughter of the Revd. William Betham (1749–1839),

antiquary. Miss Betham-Edwards hyphenated her name to include

her mother's maiden name.

Self-educated until the age of ten, she then attended a

school in Ipswich, where her French teacher first kindled her

interest in France. Later she moved to London where she came

into contact with literary personalities of the day among whom were

Henry James, Frederic Harrison, Clement Shorter (who became her

literary executor), Coventry Patmore, Sarah Grand, and others. She also became a close friend

of Barbara Leigh Bodichon and George Eliot.

In her sixty-two years as an active writer, Miss

Betham-Edwards wrote articles for newspapers, short stories, and

poems; also, many novels, children's books, books about travel (in

Wales, Germany, Greece, Spain, and Africa) and about France.

However, she believed that she would be remembered for her novels,

regarding 'Forestalled' (1880) and 'Love and Marriage' (1884) as her

best; Lord Broughton judged 'Kitty' the finest novel he

ever read while Frederic Harrison singled out 'Kitty', 'Dr Jacob',

and 'John and I'. Her writing also showed great interest in public

education, opportunities for women, cultural facilities in towns,

and positivism.

|

"What, however, would Burgundy be

like without the vine? To accustomed eyes the

vine, whether growing in the plain, on rocky hill-side,

or trellised as in Italy, must ever be one of the most

beautiful things in the world. The just

appreciable, yet never-to-be-forgotten fragrance of its

flowers in early summer, the extraordinary luxuriance of

its rich green waxen-like leaves, its unrivalled

fruit—alike the gold and the purple—are not more

striking than the beauty of the foliage clothing slope

and ridge. Especially on September afternoons,

towards sunset, is the effect of a vineyard

unforgettable. The leaves are then interpenetrated

with warm golden light, and whilst the edges seem almost

transparent, as if transmuted into thin plates of beaten

gold, all the rest of the plant—the thousand plants

between you and the sun—are deep-hued as the purpling

fruit hid in the greenery."

The vine, from . . .

Unfrequented France. |

Her interests ranged widely, particularly her commitment to

France and the French. Of Huguenot descent, she considered

France her second native land and made it her mission to bring about

better understanding and sympathy between the two countries which

shared her allegiance. The French government made her an

Officier de l’Instruction Publique de France in recognition of

her untiring efforts towards the establishment of a genuine and

lasting entente cordiale, and she was awarded a medal at the

Anglo-French Exhibition of 1908. Before her death she was

granted the belated honour of a civil list pension by the British

government.

After her death, Miss Betham-Edwards' work mostly disappeared

from view until the publication, in 2006, of Professor Joan Rees's biography, 'Matilda Betham-Edwards: Novelist, Travel Writer and

Francophile' (Hastings Press, ISBN: 1904109012). Modern

reprints of Miss Betham-Edwards' books are now becoming available.

The following magazine article and obituary (The Times)

provide more details about her life and character; her own account is given in

the accompanying on-line transcriptions of her autobiography, 'Reminiscences' (1898), and

of her posthumously published 'Mid-Victorian

Memories' (1919). Her friend, Mrs Sarah Grand, wrote a an

interesting and informative Personal

Sketch.

――――♦――――

|

Standards of conduct, Miss

Betham-Edwards remarks, differed in the middle of the

century from those now generally accepted.

"For instance, walking one day at Ipswich, we met a

labourer's wife and her two daughters, girls of twelve

and fourteen.

"'So Mrs P――', said my eldest sister, 'you have been

shopping?'

"'No, Miss,' replied the good woman, with an

unmistakable air of self-approval, 'but I am anxious to

do my girls all the good I can, so I have just taken

them to see a man hanged.'" |

――――♦――――

From . . . .

THE WOMAN'S SIGNAL

11th March, 1897.

MISS BETHAM EDWARDS.

A PERSONAL SKETCH.

BY FREDERICK DOLMAN.

HASTINGS, in

recent years has become a favourite place of abode for literary and

scientific people. Miss Matilda Betham-Edwards who has resided

there since 1869, is one of a circle which included the late Mr.

Coventry Patmore, Mr. Dykes Campbell, the editor of "Coleridge," Dr.

Elizabeth Blackwell, Mr. R. O. Prowse, author of "The Fatal

Reservation," Mr. H. G. Detmold, the artist, Mr. T. Parkin, F.R.G.S.,

&c., founder of the Hastings Natural History Society, and others of

intellectual distinction. Miss Betham-Edward's residence on

the East Cliff, overlooking the old town, reminds one of her first

novel, "The White House by the Sea," of which a new edition was

called for only the other day.

Miss Betham-Edwards has no family connections with Hastings;

she went there in the first place for health, secondly in order to

be near her life-long friend, the late Madame Bodichon, whose house

was at Robertsbridge, a few miles from the seaside resort, and she

has been induced to stay there by an admirable climate and the

pleasant social intercourse to which I have referred. Her

family belonged to Suffolk; her father was a farmer at Westerfield,

near Ipswich, where her girlhood was spent. Miss

Betham-Edwards' early life, like that of many another of

intellectual tastes, would have been terribly dull but for books.

There was no one in the village whom she could make a friend; even

the clergyman, as she remembers him, was rough and uncultivated.

Her father was, fortunately, an exception to his class at that time

in possessing an excellent library. Before she was in her

teens Miss Betham-Edwards had read all Shakespeare, Scott, and

Addison's "Spectator," whilst she knew about half "Paradise Lost" by

heart. Apart from reading, the greatest pleasure of this rural

life were the occasional visits of her cousin, the late Miss Amelia

B. Edwards, who afterwards became famous as an Egyptologist, when

the two girls would talk in their room into the night—there were so

many subjects on which they wanted to exchange ideas. In after

years, when they both became well known, the similarity of their

names caused some contention between them, which, however, was too

good-humoured to disturb their friendship. There were constant

errors of confusion between "Miss Amelia B. Edwards" and "Miss

Betham-Edwards." The latter would not give up Betham "because

it was her mother's maiden name and carried with it some literary

associations of her family. Her maternal aunt and godmother,

Matilda Betham, was the friend of the Lambs, Coleridge and Southey,

and was herself the compiler of a biography of famous women, which

had some vogue in its day. Her cousin, on the other hand,

would neither drop the B nor use her name in full, Amelia

Blanford Edwards. Consequently, their common friend, Miss

Power Cobbe, used to say, wittily, that they had both a bee in their

bonnet.

|

"Sweet and pastoral as was the

landscape, it had yet elements of grandeur.

Something of the ruggedness as well as the gracious

smile of an Alpine scene was here. Far away, the

rocky parapets shutting in the valley showed grandiose

forms, woods of larch and pine lifted their arrowy

crests against the sky, and many a mountain stream might

be seen tumbling perpendicularly down shelving rock or

green hillside. And nowhere in the world could

knolls be found softer, turf more dazzlingly bright,

rivulets more crystal clear, richer, more umbrageous

shadow. Not a trace was now left of the flat,

scorched, commonplace region just quitted. While

just before it seemed as if the plain were interminable,

so travellers might fancy now that the windings of the

valley would never come to an end either. We might

well wish it to wind on for ever, Nature here treating

her worshippers as conjurors deal with rustics at a

fair, every freshly displayed marvel surpassing the

last. At each turn the valley grew fairer and

fairer, and the world seemed remoter and more

forgotten."

The Val-Suzon, from . . .

Unfrequented France |

Miss Betham-Edwards' keen interest in France, which her

friendship with Madame Bodichon (whom Miss Betham-Edwards describes

as "by temperament and marriage French," though by parentage

British) did so much to foster, had its origin in the chance

circumstance that the school to which she was sent as a child was

conducted by a lady who had spent many years of her life across the

Channel. From her she learned to speak and write the language

with ease, Miss Betham-Edwards having the gift of the linguist.

She is now mistress of German, Italian, and Spanish; whilst ever

since her girlhood she has delighted in the originals of Latin and

Greek authors. Her exotic reading is a striking proof of what

women could do even in the days when Girton and Somerville were only

visions of the future.

The room in which Miss Betham-Edwards writes her novels

overlooks the whole of the old part of Hastings, from the Fish

Market to the Pier. Even Beachy Head can be seen on a clear

day, and Miss Betham-Edwards sometimes fancies that she discerns the

coast-line of her beloved France, 40 miles distant. On the

walls are water-colour sketches made by Madame Bodichon, in the

course of the travels she and the novelist were wont to enjoy

together. In the centre, just above a long bookcase, hangs the

brevet, conferring on Miss Betham-Edwards the title of "Officier de

I'Instruction Publique de France." She is the only

Englishwoman to whom the French Government has given this honour,

which testifies, of course, to its appreciation of the books Miss

Betham-Edwards published on the social condition of France.

The comparatively small room is not overcrowded with books,

but what Miss Betham-Edwards has are all of the best. "Now and

again I have to weed out my library," she says with a smile, "or I

should be driven out of home by the books I accumulate."

Her own works, in their various editions, fill several

shelves in the little corridor. There are the orthodox three

library volumes, picture boards, Tauchnitz editions, foreign

translations in palter covers, and American pirates. You can

count over twenty different novels.

Miss Betham-Edwards once gave me a sketch of her "day."

"In summer I rise at 6.30 a.m., take half an hour's stroll on

the Downs, read for half an hour some favourite classic (I have now

in hand the Prometheus of Æschylus, which I almost know by heart),

then I work till 1 p.m., allowing no interruption. A little

rest after lunch, a walk, tea—often partaken with a sympathetic

friend or friends, sometimes the excuse for a little reunion.

Then, from five to eight in my study again, this time to read, not

write, and give myself the relaxation of a little music.

Occasional visits to London or elsewhere, two months or more in

France every year; this is my existence.

"If I am asked," Miss Betham-Edwards adds, "my opinion as to

the secret of a happy life, I should say, first and foremost, the

conviction of accomplishing conscientiously what as an individual

you are most fitted for; next, the cultivation of the widest

intellectual, moral, and social sympathies (especially in the matter

of friendships); and lastly, freedom from what I will call social

superstitions—that is, indifference to superficial conventionalities

and the verdict of the vulgar, in other words, the preservation of

one's freedom, of what the French call "une vie de dégagée."

Miss Betham-Edwards takes a keen interest in public affairs,

which she regards—as readers of her lately-published book, "France

of To-day," will know—from the standpoint of advanced Liberalism.

On many occasions she has been asked to take part in various public

movements. On one occasion, I believe, she was asked to stand

as a candidate for the School Board. She could not be

diverted, however, from her literary work. But in thinking of

this she says:--

"How hard it is in these days of working at high pressure for

all possessed of strong convictions to hold aloof from sympathetic

workers and good causes, to adhere uncompromisingly to Goethe's

maxim, 'An der nachsten musmann denken' ('We must stick to

the matter in hand ')."

"Madame Bodichon, your loved friend, was, I believe, one of

the early workers for the higher education and other rights of women

?"

"Yes, she and Miss Emily Davies between them matured the

scheme of Girton. The pair discussed the matter morning, noon,

and night, and the result was the opening of the first college for

women, the temporary premises at Hitchin that afterwards grew into

Girton. It was the self-sacrifice of those two that carried

out the plan, for Madame Bodichon contributed £1,000 to the

initiatory outlay, and Miss Emily Davies freely undertook the

onerous post of resident principal. Madame Bodichon, too, set

on foot the amendment of the Married Women's Property laws, getting

up the first petition for their alteration."

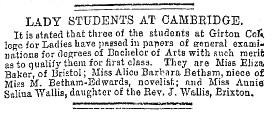

Leeds Mercury, 19th June,

1875.

"She was, herself, I believe, happily married ? "

"Very happily—Dr. Bodichon was a man of no mean attainments,

and was in the fullest sympathy with his wife's aims. Again,

it is worth mention that she was as beautiful and healthful in

person as in mind. She was, even in middle-life, 'fresh as a

rose,' with magnificent complexion, golden hair and beaming blue

eyes. She was a model for Titian."

"So that she could richly well afford to despise the silly

saying, 'Women's Rights are Men's Lefts.' "

"Then she was so joyous and light-hearted, though gifted with

a tender readiness to feel others' woes. 'It is a benediction

to see you,' said Browning to her once; and it was so still after

her health failed, and to the very last in her sick-room—living, not

there, but in the large life of others, the future of humanity.

She bequeathed £15,000 to Girton, and £1,000 to Bedford College.

I have several times since her death had to call the attention of

editors and writers to her work, for she took no care of her own

reputation in what she did, and desired no praise, and hence she has

not been properly appreciated."

"To live in hearts we leave behind is not to die," and the

reader will value the generous love that Miss Betham-Edwards

testifies to her friend.

――――♦――――

TIMES

7th January, 1919.

DEATH OF MISS BETHAM-EDWARDS.

――――♦――――

AN INTERPRETER OF FRANCE.

Miss Matilda Betham-Edwards, who died at Hastings on

Saturday, was a prolific writer, especially on French rural life.

She was the daughter of a Suffolk farmer, and her mother, the niece

of Sir William Betham, Ulster King-at-Arms, was the Barbara Betham

to whom Mary Lamb addressed many charming letters. Amelia

Blandford Edwards, the novelist who wrote charming books of travel,

and finally achieved fame as an Egyptologist, was her first cousin.

In the manor-house in which she grew up there was a library

which she describes as "small but priceless." It included the

Waverley Novels, the "Spectator," "Don Quixote," "The Vicar of

Wakefield," "Robinson Crusoe," and "Gulliver's Travels." On

these excellent models Miss Edwards unconsciously formed her taste,

if not her style. She began to write before she was out of her

teens, and had finished her first novel—"The White House by the

Sea"—soon after her 20th birthday. As there was no parcel post

in those days, the family grocer arranged for its conveyance to

London, where it was quickly accepted for publication on terms more

advantageous to the publisher than to the author. The book has

passed through several editions—the first appearing in 1857, and the

last, we believe, in 1891—but Miss Edwards received no farthing of

profit, but only "25 copies of new one, two, and three-volume

novels" from the pens of her rivals.

Her professional literary career, however, did not begin

immediately. Her first experience of life was as a "pupil-

teacher" in a Peckham seminary for young ladies—an unsatisfactory

establishment in which she was uncomfortable, and would have been

unhappy, had it not been for the opportunity of cementing her

friendship with her cousin, who was, at that time, an organist in a

small London church. Her cousin's father, a retired officer

who had fought at Corunna, lived near Colebrooke-row—an address

famous through its memories of Charles Lamb—and it was as a visitor

to his house that Miss Edwards began to acquire her knowledge of the

metropolis. She left London to study German at Württemberg,

Frankfort-on-the-Main, Vienna, and Heidelberg, and French in Paris.

It was while she was at Frankfort that a scandal connected with the

English church furnished her with the plot of "Dr. Jacob," though

she did not write the story until some time afterwards [Ed.—pub.

1864]; and she also received, while in Germany, an offer of

marriage from a Hungarian patriot, and a proposal that she should

become the adopted daughter of a roving Englishwoman of large means.

She declined both propositions, and, on her father's death, returned

to Suffolk, and undertook the management of his farm, in partnership

with an unmarried sister. It was during this period of her

life that she received her first literary remuneration, a cheque for

£5 for a poem contributed to Household Words, and still a

favourite at "penny readings." Even more precious to her than

the £5 was the encouraging letter from Charles Dickens which

accompanied it.

On her sister's death she decided to give up the farm and

live in London, and there she soon made many friends of great

eminence. She was a guest, sometimes, at Lord Houghton's

famous breakfast parties; and she enjoyed the intimacy of George

Eliot and Mme. Bodichon. She, George Eliot, and G. H. Lewes

were at Ventnor together in the winter of 1870-1871, and were

invited to an entertainment described as "a serious tea" by another

author, Miss Sewell, who kept a girls' school there.

TRAVELS IN FRANCE.

Thus, by degrees, under pleasant auspices, and without much

conscious effort, Miss Edwards found her métier. She

had no inconsiderable popularity as a novelist, though her fiction

lacked the highest distinction; but a long sojourn in the house of a

French family at Nantes in 1875 launched her on the path which she

was to follow most successfully. Thenceforward she became an

interpreter of France and the French to England and the English.

She travelled in every part of the country, and wrote books about

all her journeys. "East of Paris," "Anglo-French

Reminiscences," "Home Life in France," "Literary Rambles in France"

are the titles of a few of them. She went even as far as the

Cevennes and the gorges of the Tarn, and was never tired of

insisting that France, in virtue of its historical and literary

associations, was a more interesting country in which to travel than

Switzerland, whither tourists were driven in personally conducted

flocks. She had her rivals, or rather colleagues—Mr.

Baring-Gould and Mr. Harrison Barker, for instance—but her

enthusiasm, her humour, and her definite point of view made her, in

many ways, the most interesting writer in the group. She was

one of the few Englishwomen who have known how to make themselves

welcome in French houses; and she took sides, in a gossipy way, but

not without a spice of bitterness, in the controversies which divide

French opinion, more particularly in the provinces. Her

Suffolk observations and experiences had made her a Radical and an

"advanced" thinker on religious problems. The late Bishop

Ryle—not Bishop then of Liverpool—had in vain tossed her from his

passing gig a tract with the alarming title, "Why will you go to

Hell?"

"The upholding of slavery in Suffolk pulpits during the War

of Secession," she has written, "for once and for all alienated me

from the Church of England. Nor did Nonconformist chapel or

Friends' meeting-house attract. I remained unattached."

And she continued unattached in France. Her friends there were

unattached—Republican and anti-Clerical pillars of provincial

bourgeoisie—and she adopted their doctrines and preached them:

doctrines which she summarizes as "the religion of Voltaire,"

adding, "and, as experience teaches us, an excellent religion too."

Converts were a particular abomination to her; and the attitude of

the Catholic Church towards education progress excited her derision.

Her view of these matters is common enough in France nowadays; but

she adopted it at a date when the MacMahon reaction was at its

height and the triumph of Catholicism seemed assured.

Of late years Miss Edwards had lived quietly at Hastings.

France had made her an Officier de L'Instruction Publique, and

England had awarded her a Civil List Pension.

――――♦――――

BIBLIOGRAPHY

――――♦――――

|

The

White House by the Sea (1857)

Holidays Among the Mountains (or Scenes and Stories of Wales) (1860)

Little Bird Red and Little Bird Blue (verse drama) (1861)

John and I (1862)

Snow-Flakes and the stories they told

the children (ca. 1862)

Dr. Jacob (1864)

A Winter with the Swallows (1867)

Through Spain to the Sahara (1868)

Kitty (1869)

The Sylvestres (1871)

Felicia (1875)

Bridget (1877)

Brother Gabriel (1878)

Six Life Stories of Famous Women (1880)

Forestalled (1880)

Pearla (1883)

Half-Way (1886)

Next of Kin Wanted (1887)

The Parting of the Ways (1888)

For One and the World (1889)

A Romance of the Wire (1891)

Edition of Arthur Young’s Travels in France (1892)

Romance of a French Parsonage (1892)

France of To-Day (1892)

The Curb of Honour (1893)

A Romance of Dijon (1894)

The Golden Bee and other Recitations (1895)

Autobiography of Arthur Young - edited (1898)

Reminiscences (1898)

The Lord of the Harvest (1899)

Anglo-French Reminiscences (1900)

A Suffolk Courtship (1900)

Mock Beggars’ Hall (1902)

Barham Brocklebank (1903)

A Humble Lover (1903)

Home Life in France (1905)

Martha Rose (1906)

Poems (1907)

A Close Ring (1907)

Literary Rambles in France (1907)

Unfrequented France

(1910)

Friendly Faces of Three Nationalities (1911)

In French Africa (1912)

From an Islington Window (1914)

Hearts of Alsace (1916)

Twentieth Century France (1917)

French Fireside Poetry (1919)

Mid-Victorian Memories (1919) |

|