|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER IV.

OLD LONDON BRIDGE.

|

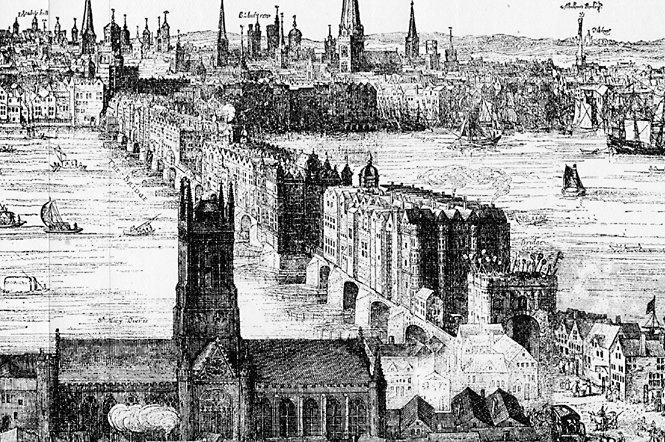

Old London Bridge, from a panorama of London by Claes

Van Visscher, 1616. Southwark Cathedral is in the foreground.

The spiked heads of executed criminals can be seen above the

Southwark gatehouse. Picture Wikipedia.

THE erection of

the old stone bridge across the Thames at London, was the most

formidable enterprise of the kind undertaken in England during the

Middle Ages. It was a work of great magnitude and difficulty,

in consequence of the rapid rise and fall of the tides in the river,

but it was one of essential importance as connecting the fertile

districts lying to the south of the Thames, directly with the

population of the metropolis.

As in all similar cases, the ferry (where the river could not

be forded) preceded the bridge. The Romans first established a

trajectus on the Thames, thus connecting their station in London

with their military road to Dover. Dion Cassius makes mention

of a bridge over the Thames at the time of the expedition of the

Emperor Claudius in A.D. 44. It may have been of boats, or it

may have been constructed on piles, for the Romans frequently

constructed bridges of this sort in order to maintain their

communications.

After the departure of the Romans the bridge ceased to exist,

and the Saxons continued to pass across from one side of the river

to the other by means of a ferry. The name of one of the

masters of the ancient ferry has descended to us in a tradition of a

singular character. [p.70]

This was John Overy, the father of the foundress of St. Mary's

church in Southwark. The property in the ferry, with its

revenues, having become the possession of the adjoining college of

priests of St. Mary's, they determined on the bold enterprise of

erecting a bridge of timber across the river. The first

mention of this structure is contained in the laws of Ethelred,

where the tolls of vessels coming to Billingsgate ad pontem

are fixed and defined. William of Malmesbury states that, in

994, Sweyn, the Danish king, when sailing up the river to the attack

of London, ran foul of the bridge with his ships, and in the contest

which subsequently ensued between the Londoners on the north and the

Danes on the south of the river, the bridge was destroyed.

It seems, however, to have been repaired by the time that

Canute sailed up the Thames with his fleet several years later; for,

finding the bridge to be an obstacle in his way, he adopted the bold

expedient of cutting a wide ditch or canal from near Dockhead, at

Redriff, through the marshes on the south side of the river,

westward to the lower end of Chelsea Reach, through which he drew

his ships and completed the blockade of the city. Not long

after, in 1091, the timber-bridge was entirely swept away by a

flood; but the provision of so great a convenience was found

indispensable, and William Rufus levied a heavy tax for its

rebuilding.

Again, in 1097, a new timber-bridge rose upon the ruins of

the old one; but fifty years later we find it destroyed by a fire

which broke out in a tenement near London Stone, and burnt down all

the houses eastward as far as Aldgate, and from thence to the south

bank of the river, including the Bridge. It was again patched

up; but it was found so costly to maintain the wooden structure, and

it ran so much risk from fire and floods, that it was eventually

determined to build a bridge of stone upon nearly the same site; and

the work was accordingly begun by one Peter, the chaplain of St.

Mary's, Colechurch, in the Poultry, in the year 1176.

One of the most important considerations in building a bridge

across a deep and rapid river is the security of its foundations.

Comparatively few of the older bridges failed from the unskilful

construction of their arches, but many were undermined and carried

away by floods where the foundation of the piers was insecure.

The period at which Old London Bridge was built is so remote, and

the records left of the mode of conducting the work are so meagre,

that it is impossible, even were it desirable, to give any detailed

account of the building. Some writers have supposed that the

whole course of the river was diverted in the line of Canute's canal

above referred to, and that the bed of the Thames was thus laid dry

to enable the foundations of the piers to be got in. [p.72]

This expedient has frequently been adopted in building bridges

across streams of moderate size; but it is scarcely probable that it

was employed in this case. When the foundations of the old

bridge were taken up, it was ascertained that strong elm piles had

been driven deep into the bed of the river as closely as possible,

and large blocks of stone were cast into the interior spaces.

Long planks, strongly bolted, were placed over the piles, and on

these the bases of the piers were laid, the lowermost being bedded

in pitch, whilst outside of all was placed the pile-work, called

starlings, for the purpose of breaking the rush of the water and

protecting the foundation piles.

Another statement was long current—that London Bridge was

built on wool-packs arising from the circumstance that a tax was

levied by the King upon wool, skins, and leather, passing over the

bridge, towards defraying the cost of its construction. The

bridge was in a measure regarded as a national work, and for more

than two centuries after its erection, tribute continued to be

levied upon the inhabitants of the counties nearest the metropolis

for its maintenance and repair. Liberal gifts and donations

were also made with the same object, until at length the Bridge

Estates yielded a large annual income.

Not less than thirty-three years were occupied in the

erection of this important structure. It was begun in the

reign of Henry II., carried on during that of Richard I., and

finished in the eleventh year of King John, 1209. Before then,

however, the agčd priest, its architect, died, and he was buried in

the crypt of the chapel which had by that time been erected over the

centre pier. At his death another priest, a Frenchman, called

Isenbert, who had displayed much skill in constructing the bridges

at Saintes and Rochelle, was recommended by the King as his

successor. But his appointment was not confirmed by the Mayor

and citizens of London, who deputed three of their own body to

superintend the finishing of the work—the chief difficulties

connected with which had indeed already been surmounted.

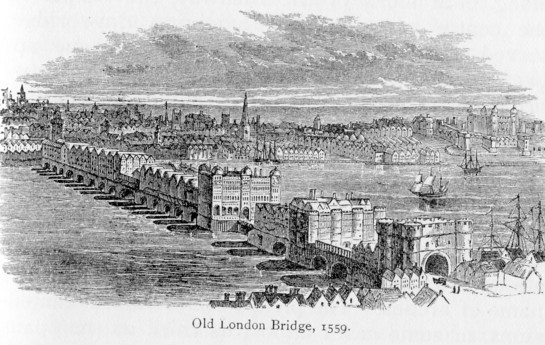

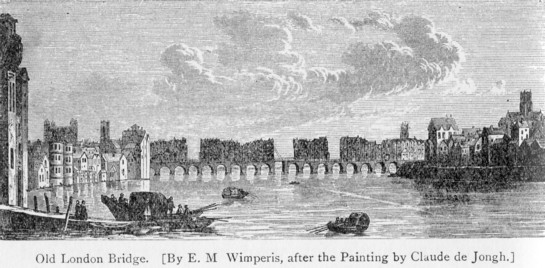

The bridge, when finished, was a remarkable and curious work.

That it possessed the elements of stability and strength was

sufficiently proved by the fact that upon it the traffic of London

was safely borne across the river for more than six hundred years.

But it was an unsightly mass of masonry, so far as the bridge was

concerned; although the overhanging buildings, extending along both

sides of the roadway, the chapel on the centre pier, and the

adjoining drawbridge, served to give it an exceedingly picturesque

appearance. One of the houses adjoining the drawbridge was

dignified with the name of Nonsuch House: it was said to have been

constructed in Holland and brought over in pieces, when it was set

up without mortar or iron, being held together solely by wooden

pegs.

The piers of the bridge were so close, and the arches so low,

that at high water they resembled a long low series of culverts

hardly deserving the name of arches. The piers were of various

dimensions, in some cases almost as thick as the spans of the arches

which they supported were wide. The structure might be

compared to a very strong stone embankment built across the river,

perforated by a number of small openings, through which the water

rushed with tremendous force as the tide was rising or falling, the

power thus produced being at a later period economised and employed

in some of the arches to work water-engines. The bridge had

not less than twenty arches, including the drawbridge, some of them

being too narrow to admit of the passage of boats of any kind.

This great obstruction of the stream, at a point where the

river is about the narrowest, had the effect of producing a series

of cataracts at the rise and fall of each tide, so that what was

called "the roar of the bridge" was heard a long way off. The

feat of "shooting the bridge" was in those days attended with

considerable danger, and lives were frequently lost in the attempt.

Hence prudent passengers, who took a boat for down river, usually

landed above the bridge and walked to the nearest wharf below, where

they again embarked. The more venturous risked "shooting the

bridge," and thus boats were frequently swamped and their passengers

drowned. In 1428 John Mowbray, second Duke of Norfolk, when

passing under one of the arches, ran his boat upon the pile-work,

and had very nearly perished; but leaping on to one of the

starlings, he was then hauled up to the bridge by ropes let down to

him for the purpose. The risk attending this operation of

shooting the bridge explains the old proverb, that "London Bridge

was made for wise men to go over, and fools to go under."

Perhaps the most singular feature of the old bridge was its

upper platform, consisting of two rows of houses with a narrow

roadway between, the chapel and drawbridge, and the turreted

battlements at either end. The length of the roadway was 926

feet, and from end to end it was enclosed by the lofty

timber-houses, which were held together by arches crossing overhead

from one range to the other and thus keeping the whole in position.

The street was narrow, dark, and dangerous. There were only

three openings between the houses on either side, provided with

balustrades, from which a view of the river and its shipping might

be obtained, as well as of the rear of the houses themselves, which

overhung the parapets and completely hid the arches from sight.

On the centre pier was the chapel with its tower, and at the

ends of the bridge were the gatehouses, on which the grim heads of

traitors and unfortunate partisans were stuck upon poles until a

comparatively recent period. Hentzner, a German traveller,

counted above thirty heads displayed upon them as late as the year

1598.

The drawbridge was another curious feature. It occupied

the fourteenth arch from the north end, and provided an opening of

about thirty feet. It was used for purposes of defence as well

as to provide for the passage of masted ships. When Jack Cade

was told of the army marching against him, Shakespeare makes him

say, "Let's go fight with them; but first go and set London Bridge

on fire." But Cade's project having failed, his head was taken

off and placed upon a pole, amongst those of other traitors, over

the southern gatehouse, with his face looking towards Kent.

The bridge was also used as a place of public punishment.

Persons found guilty of practising witchcraft were compelled to do

penance there. No less a personage than Eleanor Cobham,

Duchess of Gloucester, was exposed upon the bridge in 1440, for the

alleged crime of witchcraft.

The bridge had a long history and many vicissitudes. It

had scarcely been completed ere the timber-houses upon it were

consumed by a fire, and the bridge was thus at once stripped of its

cumbrous load. But, as the revenues required for its

maintenance and repair were in a great measure derived from the

rental of the houses, which let for high sums, they were shortly

after erected in even more cumbersome forms than before, and were

for a long time principally inhabited by pin-and needle-makers.

At a very early period the bridge showed signs of weakness.

Before it had stood a hundred years, a patent was issued by Edward

I., authorising its speedy repair, in order "to prevent its sudden

fall and the destruction of innumerable people dwelling thereon."

Tolls were authorised to be taken—for every man crossing, a

farthing; for every horseman, a penny; for every pack carried on a

horse, one half-penny. There was not a word of vehicles, which

did not as yet exist. The repairs done to the structure do not

seem to have been of much effect; for in 1281 five of the arches,

with the buildings over them, were carried away by a flood following

a thaw, and the repairs had to be begun again on a more extensive

scale than before. At a subsequent period Stowe's gate, tower,

and arches, at the Southwark side, fell into the river.

After repeated patching, the bridge nevertheless continued to

hang together for several centuries longer. It witnessed the

processions of priests, the jousting of knights, the march of

Kentish rebels, the triumphal march of Henry V. into the City after

the battle of Agincourt, the funeral procession of the same monarch

when borne to his royal tomb in Westminster Abbey, and the entrance

to the metropolis of his successor after being crowned King of

France at Notre Dame. Generation after generation of toiling

men and women passed over the bridge, wearing its tracks deep with

their feet, and sometimes moistening them with their tears.

Still the old bridge stood on, almost down to our own day; for we

shall find in the lives of Smeaton and Rennie, that these eminent

engineers, amongst others, were called upon from time to time to

direct its repair; until at last the old structure, which had served

its purpose so long, was condemned and taken down, and the

magnificent New London Bridge was erected in its stead.

It was long before any second bridge was built over the

Thames near London. The advantages derived from the current of

traffic passing through the City from a district extending for fifty

or sixty miles on all sides of London, were felt to be of such

importance that the citizens would not readily part with them.

Bridges were regarded as the best feeders of towns and cities, and

wherever one was erected, all the avenues by which it was approached

became speedily converted into streets of valuable houses. At

the two ends of the Thames Bridge were London and Southwark; at Tyne

Bridge, Newcastle and Gateshead; and at the Medway Bridge, Rochester

and Strood. But London was extending westward with such rapid

strides, and the population of Westminster as well as Lambeth had so

much increased, that the provision of an additional bridge for those

districts came to be regarded as a matter of absolute necessity.

An attempt was made with this object in the reign of Charles

II., but the project was vigorously resisted by the citizens of

London. They waited upon his Majesty in state, and implored

him to oppose the measure; and, on his compliance with the petition,

their expression of gratitude towards him was as great as if he had

delivered the City from a famine, or a plague, or a great fire, or

some such overwhelming calamity. It is not improbable that the

citizens secured his Majesty's support by the offer of money, which

he very much wanted at the time; for we find from the records of the

Common Council, of date the 25th October, 1664, that upon advancing

by way of loan, the sum of Ł100,000 to Charles II., the citizens

took occasion to thank his Majesty in the following terms for

preventing the erection of the new bridge at Westminster:—

"And withal to represent unto his Majesty the City's

great sense and apprehension of, and most humble thanks for, the

great instance of his Majesty's good and favour towards them

expressed in preventing of the new bridge proposed to be built over

the river of Thames betwixt Lambeth and Westminster, which, as is

conceived, would have been of dangerous consequence to the state of

this city." [p.79]

A few years later, in 1671, a similar project was attempted,

and a bill was brought into the House of Commons to enable a bridge

to be erected over the Thames as far west as Putney. But the

Corporation of London was again up in arms, protesting against the

establishment of any bridge which should enable the traffic

to pass from one side of the river to the other without going

through the City. The debate on the subject is exceedingly

curious, as read by the light of the present day. Mr. Love

declared the opinion of the Lord Mayor to be, "that if carts were to

go over the proposed new bridge, London would be destroyed."

Sir William Thompson opposed it because it "would make the skirts of

London too big for the body," besides producing sands and shelves in

the river, and affecting the below-bridge navigation, which would

cause the ships to lie as low down as Woolwich; whilst Mr. Boscawen

opposed the bill, because, if conceded, there might be a claim set

up for even a third bridge, at Lambeth, or some other point.

[p.80] The bill was thrown

out on these grounds by a majority of 67 to 54; and for nearly a

hundred years more, London had no second bridge, notwithstanding

that the old structure was so narrow that there was not room on it

for two carts to pass each other! Since that time, however,

twelve bridges have been thrown across the river between Putney and

the City, and London is not yet destroyed! Indeed the cry

still is for more bridges.

The second bridge was built in 1738-50, nearly opposite the

palace of Westminster. During the many centuries that had

elapsed since old London Bridge had been erected, the science of

bridge-building had made but little progress in England. The

principal structures were of wood. Trees, merely squared, were

laid side by side, at right angles with the stream, supported on

perpendicular piles, the roadway being planked over and covered with

gravel. Old Battersea Bridge was an example of the primitive

structures by means of which many of our wide rivers long continued

to be crossed. Few were built of stone, and these, of a

comparatively rude kind, were principally situated upon the main

lines of road; but they were usually liable to be swept away by the

first heavy flood. During the period referred to, however, the

science of construction had made great progress in France, and from

the practice of French engineers our best models continued for some

time longer to be drawn. Hence, when the sanction of

Parliament was at length obtained for a second bridge to be built

across the Thames, Labelye, the French engineer, a native of

Switzerland, was employed to design and execute the work.

It will have been observed that the chief difficulty with the

early bridge-builders was, in securing proper foundations for their

piers. A common practice was to sink baskets of small

dimensions, full of stones, in the bed of the river, and on these,

when raised above water, the foundations were laid. But where

the bottom was composed of loose, shifting material, such as sand,

it will be obvious that a firm basis could scarcely be secured by

such a method. The plan adopted by Labelye, though considered an

improvement at the time, was even inferior to the method employed by

Peter of Colchurch in founding the piers of old London Bridge in the

thirteenth century. For, clumsy though the latter structure

was, it stood more than six hundred years, whilst Westminster Bridge

had not been erected a century before it exhibited signs of giving

way; and it is already destroyed.

|

Westminster Bridge around 1750. Picture Wikipedia.

|

Labelye's method of founding his piers was as follows.

He had a sufficient number of large caissons, or water-tight chests,

prepared on shore, of such form as to fit close alongside of each

other. They were then floated on rafts over the spots destined

for the piers, where they were permanently sunk. The top of

each caisson, when sunk, being above high-water mark, the masonry

was commenced within it, and carried up to a level with the stream,

when the timber sides were removed and the pier was left resting

firmly on the bottom grating. The foundations were then

protected by sheet-piling, that is by a row of timbers driven firmly

side by side into the earth all round the piers.

Westminster Bridge was originally intended for a wooden

bridge, but the design was subsequently altered to one of stone,

Labelye considering it necessary to have a great weight of masonry

in order to keep his caissons at the proper level. To add to

this weight, the engineer added a lofty parapet, which Grosley a

French traveller, gravely asserted was placed there for the purpose

of preventing the Londoners from committing suicide!

Not many years after Westminster Bridge had been opened, the

London Common Council, in order to facilitate the passage of traffic

across the Thames as near to the centre of the City as possible,

applied to Parliament for powers to construct a bridge at

Blackfriars; and the requisite Act having been passed, the works

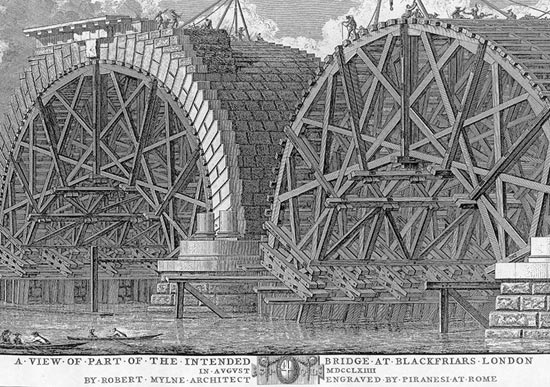

were commenced in 1760, and finished in 1769. The architect

and engineer of Blackfriars Bridge was Robert Mylne; and a noble

piece of masonry it was. The principal new feature in this

structure was the elliptical arch, [p.83]

which Mr. Mylne was the first to introduce into England.

The innovation gave rise to a lively controversy at the time,

in which Dr. Johnson took part,—in opposition to Mr. Mylne, and in

support of his friend Gwyn, who was the designer of a rival plan.

Boswell, in his 'Life of Johnson,' defends the design of Mylne, and

adds, "it is well known that not only has Blackfriars Bridge never

sunk either in its foundation or in its arches, which were so much

the subject of contest, but any injuries which it has suffered from

the effects of severe frosts, have been already, in some measure,

repaired with sounder stone, and every necessary renewal can be

completed at a moderate expense."

This was written in 1791, only twenty years after the bridge

had been opened; and, though it may have been true then, it is so no

longer. When the numerous heavy piers of old London Bridge

which acted as a dam across the river—had been removed, the

low-water mark above-bridge fell five feet. The

velocity of the unimpeded tide, sweeping up and down the Thames

twice in every twenty-four hours, and the consequent increased scour

along the bed of the river, soon began to grind away the foundations

both of Blackfriars and Westminster Bridges; and they exhibited the

unsightly appearance of numerous props and centerings to prevent the

further subsidence of their foundations. Hence Labelye's

bridge at Westminster, and Mylne's bridge at Blackfriars, have since

been pulled down, in order to make room for newer bridges.

|

Blackfriars Bridge under construction, 1764. Picture Wikipedia.

|

Robert Mylne, the engineer above referred to, was the

descendant of a long line of Scotch masons and architects. The

originator of the family was an Aberdeen man, who erected some of

the principal churches and towers in that city, some three hundred

years ago. His son was master mason to James VI.; he built a

bridge over the Tay at Perth, which was swept away by a spate; and

executed many other works, which were more successful. His

son, and son's son, were also master masons. The latter

rebuilt the cross at Perth, which had been destroyed in Oliver

Cromwell's time for the purpose of building the Citadel. The

cross has since been demolished as a hindrance to traffic.

Robert Mylne, the architect who built Blackfriars Bridge, was

lineally descended from the master mason of James VI. In his

youthhood he travelled abroad, and joined the Academy of St. Luke at

Rome. He remained there five years, and received the chief

prize in the highest class of architecture. After the building

of Blackfriars Bridge, he was appointed surveyor of St. Paul's

Cathedral; and at his death he was buried by the side of Sir

Christopher Wren.

Mr. Mylne also held the office of engineer to the New River

Company, in which he was succeeded by his son, and afterwards by his

"son's son."

――――♦――――

CHAPTER V.

WILLIAM EDWARDS, BRIDGE BUILDER.

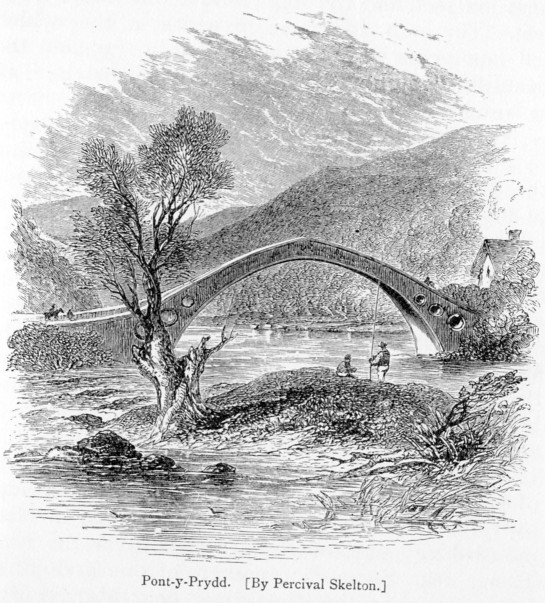

THE difficulties

encountered by the early bridge builders cannot be better

illustrated than by a brief history of the life of William Edwards,

architect of Pont-y-Prydd—a remarkable work erected at Newbridge, in

South Wales, about the middle of last century.

Edwards was born in 1719, in a small farmhouse in the parish

of Eglwysilan, in Glamorganshire. His father died when William

was only two years old; but his mother, who was an industrious,

well-doing woman, kept on the farm, and piously and virtuously

brought up her family. William's literary culture was confined

to Welsh, which he could read and write from his early youth; but as

he grew older he also learnt to read and write English, though more

imperfectly. He had the character of being obstinate,

stubborn, and self-willed in his boyhood,—qualities which, under the

guidance of virtue and piety, became developed into inflexible

courage and resolution in his manhood. Until eighteen years of

age he was regarded as a wild, headstrong fellow, with little

promise of good in him; but he was gradually tamed and disciplined

by hard work, and as he grew older he became thoughtful and sedate

even beyond his years.

Edwards's first ordinary employment was common farm-work; but

at the same time he was a diligent self-educator, taking lessons in

arithmetic from a neighbour in the evenings. It happened that,

in the ordinary course of affairs, he had occasion to repair the

dry-stone walls about the farm. He took particular pleasure in

this kind of work, and very soon became remarkably handy at it; but

he always longed to do better. Some masons having come into

the neighbourhood to build a smithy, Edwards would occasionally

leave his farm-work and take his stand in the field where the masons

were employed, eagerly watching them while they worked. He

admired the way in which they handled their tools and prepared the

stones for the building. One thing that he particularly noted

was the way in which they dressed the rough blocks by means of the

pointed end of the mason's hammer. He tried to do the same,

but failed, his hammer-point not being steeled. He then

inquired and ascertained the cause of his failure, and went to a

smith and had a steeled point added to his hammer. With this

he succeeded in dressing his stones much more neatly and quickly

than he had been able to do before.

Practice and application, and the desire to excel, even in

dry-stone wall building, inevitably carry a man onward; and Edwards

soon became so expert in this sort of work, that he was extensively

employed in repairing and building dry-stone walls for the

neighbouring farmers. His walls were observed to be so neat,

so firm, and so serviceable, that he was everywhere in request, and

his earnings were regularly added to the common stock of his mother

and brothers, who carried on the business of the farm. He

began to consider himself fitted for something better than

continuing this rough sort of work; and he thought that, instead of

being a mere builder of dry-stone walls, he might even undertake to

become a builder of houses.

An opportunity occurred of erecting a little workshop for a

neighbour, and Edwards acquitted himself so well, that he gained

much praise for his skill. Thus proving his ability in small

things, he was shortly entrusted with the execution of works of

greater importance. He had scarcely reached the age of

twenty-one when he was employed to build an iron forge at Cardiff,

and while carrying on the work he lodged with a blind man, named

Rosser, by trade a baker. Rosser knew the English language,

which as yet Edwards did not; and, what was more, the blind man

could teach it to others. The young mason determined to take

lessons of his landlord; and such was his assiduity and perseverance

during his leisure hours, that he very shortly contrived to master

the new language.

When he had completed his contract, which he did to the

entire satisfaction of his employers, he regularly entered upon the

business of a house-builder on a considerable scale, and very

shortly there was not a building of any magnitude or importance in

the neighbourhood—whether it were a mansion, a mill, or an iron

forge—which he was not willing as well as competent to undertake.

During his leisure he took great pleasure in studying the

ruins of Caerphilly Castle, near to where he lived. This castle was

once the largest in the kingdom, next to Windsor, and its ruins are

still of great extent, covering an area of about thirty acres.

Its walls are of prodigious thickness, and its leaning tower has

stood for centuries, inclining as much as eleven feet out of the

perpendicular, held together principally by the strength of its

cement. This old castle was the college in which Edwards

studied the principles of masonry; and he himself was accustomed to

say that he had derived more advantage from wandering about the

ruins, observing the methods adopted by the ancient builders, the

manner in which they had hewed, dressed, and set their stones, than

from all the other instruction he received. It was while

employed in erecting a mill in his own parish that he first applied

the knowledge he had gained by studying the ruins of Caerphilly, in

the construction of an arch. The mill was finished to

admiration, and professional builders pronounced Edwards's arch to

be an excellent piece of masonry.

Employment now flowed in upon him, and when any work of more

than ordinary difficulty was proposed, application was usually made

to William Edwards. Hence, in 1746, when it was proposed to

throw a bridge over the river Taff, he was employed to build it; and

though he was only twenty-seven years old, and had not yet built any

bridge, he had the courage at once to undertake the work. The

bridge was built of three arches, in a style superior to anything of

the kind that had been erected in the neighbourhood; the stones were

excellently dressed and closely jointed; the arches were light and

elegant, and supposed to be sufficiently substantial for the duty

they had to perform, and as a whole the erection was much admired,

and greatly added to the fame of its builder.

It would appear, however, that Edwards had not sufficiently

provided for the passage of the floods, which in certain seasons

rush down from the Brecknock Beacon mountains with great

impetuosity. Above Newbridge several rivers of considerable

capacity, such as the Crue, the Bargold Taff, and the Cynon, besides

numberless brooks descending rapidly from the high grounds,

contribute to swell the torrent so as to render it almost

irresistible. The piers of Edwards's new bridge unfortunately

proved a serious obstruction in the way of a heavy flood which swept

down the valley about two years and a half after the bridge had been

completed. Trees were torn up by the roots and carried down

the stream, lodging athwart the piers, where brushwood, haystacks

and field-gates, becoming firmly stuck amongst their branches,

choked up their arches and fairly dammed the torrent. The

waters rapidly accumulated above the bridge and rose to the

parapets; the sides of the valley being steep, left no room for

their escape, and the tremendous force finally swept away arches and

piers together, carrying the materials far down the river.

This destruction of his first bridge was doubtless a terrible

blow to the builder, who was bound in sureties to maintain it for a

period of seven years. But worse even than the loss of his

time and labour was the failure of his design, the most distressing

of all things to the man who takes a proper pride in his calling.

He resolved, however, to fulfil his contract, and began the building

of a second bridge of only one arch, to avoid the defect which had

proved the ruin of the first.

This second bridge, without piers, was a much more difficult

work than the first, in consequence of the wide span of the arch,

which was not less than 140 feet, the segment of a circle of 170

feet in diameter. No such extensive span had yet been

attempted in England; and even on the Continent, where the science

of bridge-building was much better understood, the only bridges of

larger span were of ancient construction, chiefly Roman.

Michael Angelo's beautiful bridge of the Rialto, at Venice, was the

largest span attempted in modern times, and its width was only about

100 feet.

The result of Edwards's daring experiment proved its extreme

difficulty. He succeeded in finishing the arch, but had not

added the parapets, when the tremendous pressure of the masonry over

the haunches forced them down, the light crown of the bridge sprang

up, the key stones were forced out, and a second time the labour of

Edwards was lost, and his masonry lay a ruin at the bottom of the

river. Yet not altogether lost: for by failure he learnt

experience, dearly bought though it had been.

The undaunted man determined to try again. Twice he had

failed, yet he was not utterly defeated in his resources. He

would try a new expedient, and he believed he should eventually

succeed. Fortunately his friends believed in him too, for they

generously came forward and helped him with the means of building

his third bridge, which proved a complete success. The courage

and skill of Edwards were crowned at last.

The plan which he adopted of more equally balancing the work

and relieving the severe thrust upon the haunches, was to introduce

three cylindrical holes or tunnels in the masonry at those parts of

the bridge. The same plan is found to have been adopted in

some of the ancient bridges, and Perronet, the great French

engineer, not only formed such tunnels over the haunches, but

occasionally in the piers themselves. Where Edwards gained his

information as to the expedient, or whether he had gathered it from

his own bitter experience, is not known; but it answered his

purpose. Three cylindrical holes were built over each

haunch—the lowest and outermost nine feet in diameter, the next six

feet, and the highest and innermost three feet. The arch, the

same in width as that which fell four years before, was finished in

1755, and the beautiful "rainbow bridge" lightly spans the Taff at

Newbridge to this day.

The singular inflexibility of purpose displayed by our

engineer in grappling with and overcoming the difficulties

encountered by him in the erection of his first bridge, became the

subject of general interest throughout Wales. When it was

finished and opened for public traffic, and the news spread abroad

that the extraordinary arch of Pont-y-Prydd at last stood firm as

the rocks on which it rested, strangers flocked from all parts to

view it, and the Welsh people, as was natural, became proud of their

countryman. Employment flowed in upon him, and he went on building

bridge after bridge in all parts of South Wales.

Among the more important of the later works of Edwards were

the large and handsome bridge over the river Usk, at the town of Usk,

in Monmouthshire; one, of three arches, over the river Tame, near

Swansea; another, of one arch of 95 feet span, over the same river

near Morriston; a third, with an arch of 8o feet, at Pont-cer-Tame,

several miles higher up; and Bettws and Llandovery Bridges, in the

county of Caermarthen, the latter of 84 feet span. He also built

Aberavon Bridge, in Glamorganshire, with an arch of 7o feet span;

and Glasbury Bridge, of four arches, over the Wye, near Hay, in

Brecknockshire, which was afterwards carried away by one of the

floods so common in the district.

|

The Usk Bridge over the River Usk: built in 1746-52 to a design by William

Edwards.

© Copyright

Philip Halling and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

Edwards's strong judgment and keen observant faculties,

ripened by experience, enabled him, as he grew older, to introduce

many improvements in his bridges. He flattened his arches, so

as to render the passage of vehicles over them more easy than in the

case of Pont-y-Prydd, the steepness on either side of which was

found to be so great an obstacle, that it was afterwards found

necessary to supersede its use by a more level bridge erected on

modern principles. Hence his later works presented a

considerable improvement in this respect upon his earlier ones; and

while he continued to be equally careful in providing ample

water-way under the arching, and to erect his bridges with a view to

the greatest possible durability, he took increasing pains to

provide a more capacious and level roadway over them, and to render

them in all ways more easy and convenient for public use.

Besides his numerous bridges, Edwards continued, during the

remainder of his long life, to erect smelting-houses, forges, and

buildings of various kinds for purposes of manufacture. Nor

did his building business exclusively occupy his time, for, in

addition to his profession of building engineer, he carried on the

business of a farmer until the close of his life. Not even on

Sundays did he cease from his labours. The Sabbath was no day

of rest for him, but his labours then were all labours of love.

In 1750 he became an ordained preacher amongst the

Independents. Shortly after, he was chosen minister of the

congregation to which he belonged, and he continued to hold the

office for about forty years, until his death. He occasionally

preached in the neighbouring meeting-houses: amongst others, in that

of Mr. Rees, the father of Abraham Rees, editor of the well-known 'Encyclopedia.'

This meeting-house was one of the numerous buildings erected by

Edwards himself.

He always preached in Welsh, and his discourses are said to

have been simple, sensible, and full of loving-kindness. His

fellow-countryman Malkin [p.96]

says of him, that, though a Calvinist, he was one of a very liberal

description; indeed, he carried his charity so far that many persons

suspected he had changed his opinions, and for that reason spoke

very unhandsomely of him. As he grew older he became

increasingly charitable, and tolerant of other men's views, avoiding

points of doctrinal difference, but urging and enforcing that the

love of God and of our neighbour is the aim and end of all religion.

Holding it to be the duty of every religious society to contribute

liberally of their means to the support of their ministry, he

regularly took the stipulated salary which his congregation allowed

to their preachers, but distributed the whole of it amongst the

poorer members of his church, often adding to it largely from his

own means.

This worthy engineer died at the advanced age of seventy,

respected and beloved by men of all parties; and he was buried in

the churchyard of his native parish of Eglwysilan, amidst the graves

of his children. Three of his sons were, like their father,

eminent bridge-builders: David having constructed the fine

five-arched bridge over the Usk at Newport, as well as the bridges

at Llandilo, Edwinsford, Pontloyrig, Bedwas, and other places.

Indeed, William Edwards may be said to have fairly inaugurated the

revival of the art of bridge-building in England. After his

time, it was taken up by Smeaton, Rennie, and Telford, and its

progress will accordingly be described in connection with the lives

and works of those distinguished engineers.

――――♦――――

LIFE OF JOHN SMEATON.

____________

CHAPTER I.

SMEATON'S BOYHOOD AND EDUCATION.

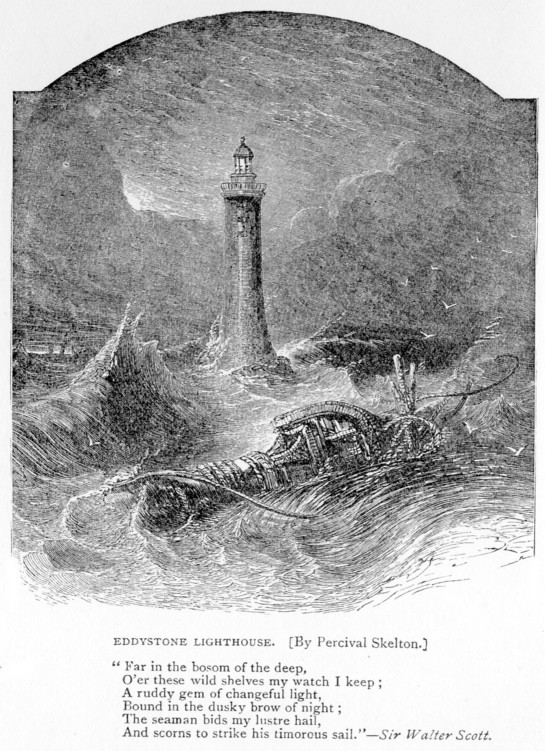

THE engineer of

the Eddystone Lighthouse was Brindley's junior by only eight years.

They frequently met in consultation upon important engineering

undertakings; sometimes Smeaton advising that Brindley should be

called in, and Brindley, on his part, recommending Smeaton.

They were, in fact, during their lifetime, the leading men in their

profession; and at Brindley's death Smeaton succeeded to much of his

business as consulting engineer in connection with the construction

of canals and of public works generally.

Smeaton had the great advantage over Brindley of a good

education and bringing up. He had not, like the Macclesfield

millwright, to force his way up through the obstructions of poverty,

toil, and parental neglect; but was led gently by the hand from his

earliest years, and carefully trained and cultured after the best

methods then known. But Smeaton, not less than Brindley, was

impelled to the career on which he entered, by a like innate genius

for construction, which displayed itself at a very early age; and,

being permitted to follow his own bent, his force of character and

strong natural ability, diligently cultivated by study and

experience, eventually carried him to the very highest eminence as

an engineer.

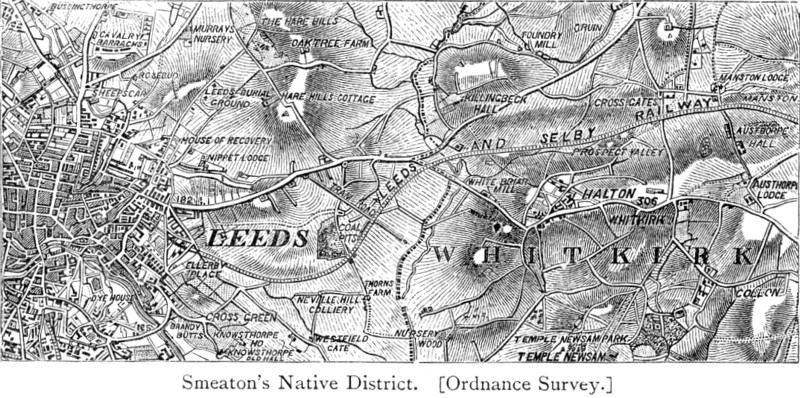

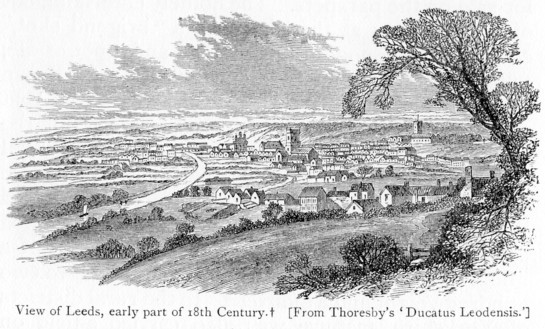

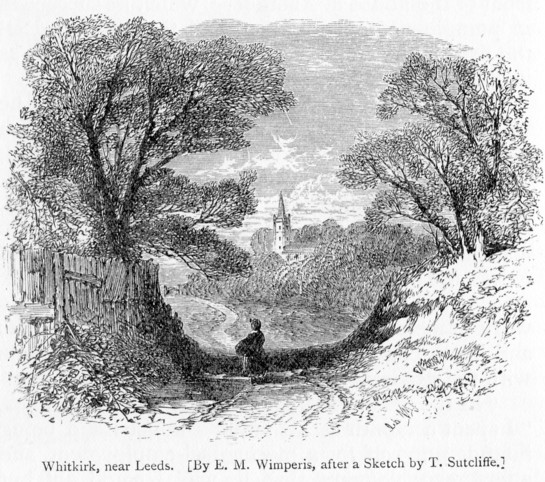

John Smeaton was born at Austhorpe Lodge, near Leeds, on the

8th of June, 1724, his father being a respectable attorney

practising in that town. The house in which the future

engineer was born was built by his grandfather John Smeaton, who is

described on the tablet to his memory erected in the neighbouring

parish church of Whitkirk, as "late of York."

|

|

Leeds was then a place of small importance, compared with

what it is now. The principal streets were those still known

as Briggate, leading to the bridge; Kirkgate, leading to the parish

church; and Swinegate, leading to the old castle. Beyond those

streets lay a wide extent of open fields. Boar Lane, now

nearly the centre of the town, was a kind of airy suburb, in which

the principal merchants resided; and the back of the houses in the

upper part of Briggate, now the main street, looked into the

country, [p.102] or to "the Park,"

on which Park Square, Park Row, and Park Lane (now containing the

new Town Hall), have since been built. There were also green

fields, with pleasant footpaths, between the parish church and the

river Aire, through certain gardens, then, as now, named "The

Calls," though the gardens exist no longer.

The clothing trade of the town was then so small that the

cloth market was held in the open air upon the bridge, where the

cloth was exposed for sale on the parapets. The homely

entertainment of the clothiers at that day was a "brigend shot,"

consisting of a noggin of porridge and a pot of ale, followed by a

twopenny trencher of meat. Down to the year 1730, the bridge

was so narrow that only one cart could pass over it at a time.

But the number of wheeled vehicles then in use was so small that the

inconvenience was scarcely felt. The whole of the cloth was

brought to market on men's and horses' backs. [p.103-1]

Coals were in like manner carried from the pits on horseback, the

stated weight of a "horse-pack" being eighteen stone, or equal to

two hundredweight and a quarter. [p.103-2]

In the rural districts of Yorkshire, manure was also carried a-field

on horses' backs, and sometimes on women's backs, while the men sat

at home knitting. [p.104-1]

The cloth-packs were carried by the "bell-horses," or packhorses;

and this mode of conveyance continued until towards the end of last

century. Scatcherd says the pack-horses only ceased to travel

about the year 1794.

[p.104-2]

The Leeds men, it seems, were not considered so "quick" as

those of Bradford, then a much smaller place, and comparatively of

the dimensions of a village. It was long before the Leeds

people provided themselves with a market for their cloth. The

first was on Mill Hill, afterwards removed to the Calls; and

finally, in 1757, they erected a large hall for the market in the

Park, now known as the Coloured Cloth Hall. But even then the

place remained comparatively rural as regards its extent and its

surrounding country.

Smeaton was greatly favoured in his home and his family.

He received his first education at his mother's knees; and when not

occupied with his lessons he led the life of a healthy, happy

country boy. Austhorpe was then quite in the country, the only

houses in the neighbourhood being those of the little hamlet of

Whitkirk, with the large old mansion of Temple Newsam, surrounded by

its noble park and woods, close at hand. Young Smeaton was not

much given to boyish sports, and early displayed a thoughtfulness

beyond his years. Most children are naturally fond of building

up miniature fabrics, and perhaps still more so of pulling them

down. But little Smeaton seemed to have a more than ordinary

love of contrivance, and that mainly for its own sake. He was

never so happy as when put in possession of any cutting-tool, by

which he could make his little imitations of houses, pumps, and

windmills. Even while a boy in petticoats, he was continually

dividing circles and squares, and the only playthings in which he

seemed to take any real pleasure, were the models of things that

would "work."

When any carpenters or masons were employed in the

neighbourhood of his father's house, the inquisitive boy was sure to

be amongst them, watching the men, and observing how they handled

their tools. He would also bother the workpeople with

questions, many of which they could not answer, nor even understand.

His life-long friend, Mr. Holmes, [p.105]

who knew him in his youth, has related that having one day observed

some millwrights at work, he was seen shortly after, to the great

alarm of his family, fixing something like a windmill on the top of

his father's barn. On another occasion, when watching some

workmen fixing a pump in the village, he was so lucky as to procure

from them a piece of bored pipe, which he succeeded in fashioning

into a working pump that actually raised water. His odd

cleverness, however, does not seem to have been appreciated; and it

is told of him that amongst the other boys he was known as "Fooely

Smeaton;" for, though forward enough in putting questions to the

workpeople, among boys of his own age he was remarkably shy, and, as

they thought, stupid.

At a proper age the boy was sent to school at Leeds.

The town then possessed, as it still does, the great advantage of an

excellent Free Grammar School, founded by the benefactions of

Catholics in early times, afterwards greatly augmented by the

endowment of one John Harrison, a native of the town, about the

period of the Reformation. At this school Smeaton is supposed

to have received the best part of his school instruction, and it is

said that his progress in geometry and arithmetic was very decided,

but, as before, the chief part of his education was conducted at

home, amongst his tools and his model machines. There he was

incessantly busy whenever he had a spare moment.

Indeed, his mechanical ingenuity sometimes led him to play

tricks which involved him in trouble. Thus, it happened that

some mechanics came into the neighbourhood to erect a

"fire-engine,"—as the steam-engine was then called—for the purpose

of pumping water from the Garforth coal-mines; and Smeaton made

daily visits to them for the purpose of watching their operations.

Carefully observing their methods, he proceeded to make a miniature

engine at home, provided with pumps and other apparatus, and he even

succeeded in getting it set to work before the colliery engine was

ready. He first tried its powers upon one of the fish-ponds in

front of the house at Austhorpe, which he succeeded in pumping

completely dry, and thereby killed all the fish in the pond, very

much to the surprise as well as the annoyance of his father.

But his father seems to have been indulgent, if he was not

proud of his boy, for he provided him with a workshop in an

outhouse, where he hammered, filed, and chiselled, very much to his

heart's content. Working on in this way, young Smeaton

contrived, by the time he had reached his fifteenth year, to make a

turning-lathe, on which he turned wood and ivory, and made presents

of little boxes and other articles to his various friends. He

also learned to work in metals, which he fused and forged himself;

and by the age of eighteen, he could handle tools with the

expertness of any regular smith or joiner.

"In the year 1742," says his friend, Mr. Holmes, "I spent a

month at his father's house; and being intended myself for a

mechanical employment, and a few years younger than he was, I could

not but view his works with astonishment. He forged his iron

and steel, and melted his metal. He had tools of every sort

for working in wood, ivory, and metals. He had made a lathe,

by which he cut a perpetual screw in brass,—a thing little known at

that day, and which, I believe, was the invention of Mr. Henry

Hindley, of York, with whom I served my apprenticeship. Mr.

Hindley was a man of the most communicative disposition, a great

lover of mechanics, and of the most fertile genius. Mr.

Smeaton soon became acquainted with him, and spent many a night at

Mr. Hindley's house till daylight, conversing on these subjects."

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

SMEATON LEARNS THE TRADE OF MATHEMATICAL

INSTRUMENT MAKER.

YOUNG

SMEATON left school in

his sixteenth year, and from that time he was employed in his

father's office, copying legal documents, and passing through the

necessary preliminary training to fit him to follow the profession

of an attorney. Mr. Smeaton, having a good connection in his

native town, naturally desired that his only son should succeed him.

But the youth took no pleasure in Law: his heart was in his workshop

with his tools. Though he mechanically travelled to the office

daily, worked assiduously at his desk, and then travelled back again

to Austhorpe, he every day felt more and more the irksomeness of his

employment.

Partly to wean him from his mechanical pursuits at home,

which often engrossed his attention half the night, and partly to

give him the best legal education which it was in his power to

bestow, Mr. Smeaton sent his son to London towards the end of the

year 1742; and for a short time he occupied himself, in conformity

with his parent's wishes, in attending the Courts in Westminster

Hall. But at length he could not repress his strong desire to

pursue some mechanical occupation, and in a firm but respectful

memorial to his father, he fully set forth his views as to the

particular calling which he wished to follow, in preference to the

profession of the law.

The father's heart was touched, and probably also his good

sense was influenced, by the son's earnest appeal; and he wrote

back, giving his assent, though not without his strong expression of

regret as to the course which his son desired to adopt. No

doubt he thought that in giving up the position of a member of a

learned and lucrative profession, and descending to the level of a

mechanical workman, his son was performing an act of great folly;

for there was no such thing then as the profession of a civil

engineer. Almost the only mechanical work of importance done

at that time was executed by millwrights and others, at labourers'

wages, as we have already seen in the Life of Brindley. The

educated classes eschewed mechanical callings, which were neither

regarded as honourable nor remunerative; and that Smeaton should

have felt so strongly impelled to depart from the usual course and

enter upon such a line of occupation, must be attributed entirely to

his innate love of construction, or, as he himself expressed it to

his father, the "bent of his genius."

When he received his father's letter, the young man

experienced the joy of a prisoner on hearing of his reprieve, and he

lost no time in exercising his new-found liberty. He sought

out for himself a philosophical instrument maker, who could give him

instruction in the business he proposed to follow, and entered into

his service,—his father being at the expense of his maintenance.

In due course of time, he was enabled to earn sufficient wages to

maintain himself; but his father continued to assist him liberally

on every occasion when money was required either for purposes of

instruction or of business.

Young Smeaton did not live a mere workman's life. He

frequented the society of educated men, and was a regular attendant

of the meetings of the Royal Society. In 1750, he lodged in

Great Turnstile, a passage leading from the south side of Holborn to

the east side of Lincoln's Inn Fields; and shortly after, when he

commenced business as mathematical instrument maker on his own

account, he lodged in Furnival's Inn Court, from which his earlier

papers read before the Royal Society were dated.

During the same year in which he began business, and when he

was only twenty-six, he read a communication before the Royal

Society, descriptive of his own and Dr. Gowin Knight's improvements

in the mariner's compass. In the year following (1751) we find

him engaged in a boat on the Serpentine river, performing

experiments with a machine of his invention, for the purpose of

measuring the way of a ship at sea. With the same object he

made a voyage down the Thames, in a small sailing vessel, to several

leagues beyond the Nore; and he afterwards made a short cruise in

the 'Fortune' sloop of war, testing his instruments by the way.

His attention as yet seems to have been confined chiefly to

the improvement of mathematical instruments used for purposes of

navigation or astronomical observation. In the year 1752,

however, he enlarged the range of his experiments; for we find him,

in April, reading a paper before the Royal Society, descriptive of

some improvements which he had contrived in the air-pump. [p.112]

On the 11th of June following, he read another paper, descriptive of

an improvement which he had made in ship-tackle by the construction

of pulleys, by means of which one man might easily raise a ton

weight; and on the 9th of November, he read a third paper,

descriptive of M. De Moura's experiments on Savary's steam-engine.

In the course of the same year he was busily occupied in

performing a series of experiments, on which his admirable paper was

founded, read before the same Society, and for which he received

their Gold Medal in 1759—entitled "An Experimental Inquiry

concerning the Natural Powers of Water and Wind to turn Mills and

other Machines depending on a Circular Motion." This paper was

very carefully elaborated, and is justly regarded as the most

masterly report that has ever been published on the subject.

To accomplish all this, and at the same time to carry on his

business, necessarily involved great application and industry.

Indeed, Smeaton was throughout his life an indefatigable

student,—bent, above all things, on self-improvement. One of

his maxims was, that "the abilities of the individual are a debt due

to the common stock of public happiness;" and the steadfastness with

which he devoted himself to useful work, in which at the same time

he found his own happiness, shows that this maxim was no mere

lip-utterance on his part, but formed the very mainspring of his

life. From an early period he carefully laid out his time with

a view to getting the most good out of it. So much was set

apart for study, so much for practical experiments, so much for

business, and so much for rest and relaxation.

We infer that Smeaton could not have done much business as a

philosophical instrument maker, from the considerable portion of his

time which he devoted to study and experiments. Probably he

already felt that, in the course of the development of English

industry, a field was opening before him of a more important

character than any that was likely to present itself in the

mathematical instrument line. He accordingly seems early to

have turned his attention to engineering, and, amongst other

branches of study, he devoted several hours daily to the acquisition

of French, in order that he might be able to read for himself the

works on that science which were then only to be found in that and

the Italian language. He had, however, a further object in

studying French, which was to enable him to make a journey which he

contemplated into the Low Countries, for the purpose of inspecting

the great canal works of the foreign engineers.

Accordingly, in 1754, he set out for Holland, and traversed

that country and Belgium, travelling mostly on foot and in

treckschuyts, or canal boats, both for the sake of economy, and that

he might more closely inspect the engineering works of the districts

through which he passed. He there found himself in a country

which had been, as it were, raked out of the very sea,—for which

Nature had done so little, and skill and industry so much.

From Rotterdam he went by Delft and the Hague to Amsterdam,

and as far north as Helder, narrowly inspecting the vast dykes

raised round the land to secure it against the clutches of the sea,

from which it had been originally won. At Amsterdam he was

astonished at the amount of harbour and dock accommodation, existing

at a time when London as yet possessed no conveniences of the

sort,—though indeed it always had its magnificent Thames.

Passing round the country by Utrecht, he proceeded to the great

sea-sluices at Brill and Helvoetsluys, by means of which the inland

waters discharged themselves, at the same time that the sea-waters

were securely dammed out.

Seventeen years later, he made use of the experience which he

had acquired in the course of his careful inspection of these great

works, in illustrating and enforcing the recommendations contained

in his elaborate report on the best means of improving Dover

Harbour. He made careful memoranda during his journey, to

which he was often accustomed to refer, and they proved of great

practical value to him in the course of his subsequent extensive

employment as a canal and harbour engineer.

Shortly after his return to England in 1755, an opportunity

occurred for the exercise of that genius in construction which

Smeaton had so carefully disciplined and cultivated; and it proved

the turning point in his fortunes, as well as the great event of his

professional life.

――――♦――――

|

CHAPTER III.

THE EDDYSTONE ROCK—WINSTANLEY'S AND RUDYERD'S

LIGHTHOUSES.

|

THE Eddystone

forms the crest of an extensive reef of rocks which rise up in deep

water about fourteen miles S.S.W. of Plymouth Harbour. Being

well out at sea, the rocks are nearly in a line with Lizard Head and

Start Point; and besides being in the way of ships bound for

Plymouth Sound, they lie in the very direction of vessels coasting

up and down the English Channel. At low water, several long

low reefs of gneiss are visible, jagged and black but at high water

they are almost completely submerged. Lying in a sloping

manner towards the south-west quarter, from which the heaviest seas

come, the waves in stormy weather come tumbling up the slope and

break over their crest with tremendous violence. The water

boils and eddies amongst the reefs, and hence the name which they

have borne from the earliest times of the Eddystone Rock.

It may readily be imagined that this reef, whilst unprotected

by any beacon, was a source of great danger to the mariner.

Many a ship coming in from the Atlantic was dashed to pieces there,

almost within sight of land, and all that came ashore was only dead

bodies and floating wreck. To avoid this terrible rock, the

navigator was accustomed to give it as wide a berth as possible, and

homeward-bound ships accordingly entered the Channel on a much more

southern parallel of latitude than they now do. In his

solicitude to avoid the one danger, the sailor too often ran foul of

another; and hence the numerous wrecks which formerly occurred along

the French coast, more particularly upon the dangerous rocks which

surround the Islands of Jersey, Guernsey, and Alderney.

We have already described the rude expedients adopted in

early times to light up certain of the more dangerous parts of the

coast, and referred to the privilege granted to private persons who

erected lighthouses, of levying tolls on passing shipping. [p.116]

It was long before any private adventurer was found ready to

undertake so daring an enterprise as the erection of a lighthouse on

the Eddystone, where only a little crest of rock was visible at high

water, scarcely capable of affording foothold for a structure of the

very narrowest basis.

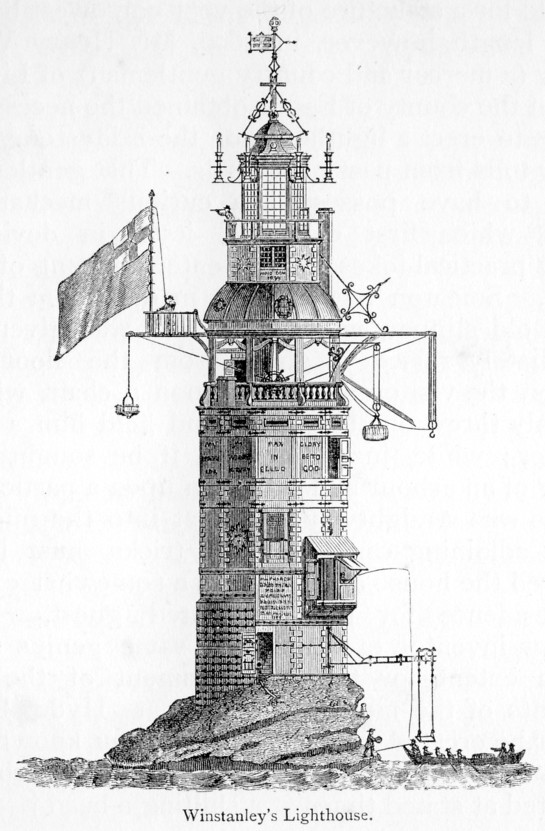

At length, however, in 1696, Mr. Henry Winstanley (a mercer

and country gentleman), of Littlebury, in the county of Essex,

obtained the necessary powers to erect a lighthouse on the

Eddystone, and to levy tolls from passing vessels. That

gentleman seems to have possessed a curious mechanical genius, which

first displayed itself in devising sundry practical jokes for the

entertainment of his guests. Smeaton tells us that in one room

there lay an old slipper, which, if a kick was given it, immediately

raised a ghost from the floor; in another, the visitor sat down upon

a chair, which suddenly threw out two arms and held him a fast

prisoner; while, in the garden, if he sought the shelter of an

arbour and sat down upon a particular seat, he was straightway set

afloat into the middle of the adjoining canal. [p.117-1]

These tricks must have rendered the house at Littlebury a somewhat

exciting residence for the uninitiated guest. The amateur

inventor exercised the same genius to a certain extent for the

entertainment of the inhabitants of the metropolis, and at Hyde Park

Corner he erected a variety of jets d'eau, known by the name of

Winstanley's Waterworks, which he exhibited at stated times at a

shilling a-head. [p.117-2]

This whimsicality of the man in some measure accounts for the

oddity of the wooden building erected by him on the Eddystone rock;

and it is matter of surprise that it should have stood the severe

weather of the English Channel for several seasons. The

building was begun in the year 1696, and finished in four years.

It must necessarily have been a work attended with great difficulty

as well as danger, as operations could only be carried on during

fine weather, when the sea was comparatively smooth. The first

summer was wholly spent in making twelve holes in the rock, and

fastening twelve irons in them by which to hold fast the

superstructure. "Even in summer," Winstanley says, "the

weather would at times prove so bad, that for ten or fourteen days

together the sea would be so raging about these rocks, caused by

outwinds and the running of the ground seas coming from the main

ocean, that although the weather should seem and be most calm in

other places, yet here it would mount and fly more than two hundred

feet, as has been so found since there was lodgment on the place,

and therefore all our works were constantly buried at those times,

and exposed to the mercy of the seas."

The second summer was spent in making a solid pillar, twelve

feet high and fourteen feet in diameter, on which to build the

lighthouse. In the third year, all the upper work was erected

to the vane, which was eighty feet above the foundation. In

the midsummer of that year Winstanley ventured to take up his

lodging with the workmen in the lighthouse; but a storm arose, and

eleven days passed before any boats could come near them.

During that period the sea washed in upon Winstanley and his

companions, wetting all their clothing and provisions, and carrying

off many of their materials. By the time the boats could land,

the party were reduced almost to their last crust; but happily, the

building stood, apparently firm. Finally, the light was

exhibited on the summit of the building on the 14th of November,

1698.

The fourth year was occupied in strengthening the building

round the foundations, making all solid nearly to a height of twenty

feet, and also in raising the upper part of the lighthouse forty

feet, to keep it well out of the wash of the sea. This timber

erection, when finished, somewhat resembled a Chinese pagoda, with

open galleries and numerous fantastic projections. The main

gallery under the light was so wide and open, that an old gentleman

who remembered both Winstanley and his lighthouse, afterwards told

Smeaton, that it was "possible for a six-oared boat to be lifted up

on a wave, and driven clear through the open gallery into the sea on

the other side." In the perspective print of the lighthouse,

published by the architect after its erection, he complacently

represented himself as fishing out of the kitchen-window!

When Winstanley had brought his work to completion, he is

said to have expressed himself so satisfied as to its strength, that

he only wished he might be there in the fiercest storm that ever

blew. In this wish he was not disappointed, though the result

was entirely the reverse of the builder's anticipations. In

November, 1703, Winstanley went off to the lighthouse to superintend

some repairs which had become necessary, and he was still in the

place with the lightkeepers, when, on the night of the 26th, a storm

of unparalleled fury burst along the coast. As day broke on

the morning of the 27th, people on shore anxiously looked in the

direction of the rock to see if Winstanley's structure had withstood

the fury of the gale; but not a vestige of it remained. The

lighthouse and its builder had been swept completely away.

The building had, in fact, been deficient in every element of

stability, and its form was such as to render it peculiarly liable

to damage from the violence both of wind and water.

"Nevertheless," as Smeaton generously observes, "it was no small

degree of heroic merit in Winstanley to undertake a piece of work

which had before been deemed impracticable, and, by the success

which attended his endeavours, to show mankind that the erection of

such a building was not in itself a thing of that kind." He

may, indeed, be said to have paved the way for the more successful

enterprise of Smeaton himself; and his failure was not without its

influence in inducing that great mechanic to exercise the care which

he did, in devising a structure that should withstand the most

violent force of the sea on the south coast. Shortly after

Winstanley's lighthouse had been swept away, the 'Winchelsea,' a

richly-laden homeward-bound Virginiaman, was wrecked on the

Eddystone rock, and almost every soul on board perished; so that the

erection of a lighthouse upon the dangerous reef remained as much a

necessity as ever.

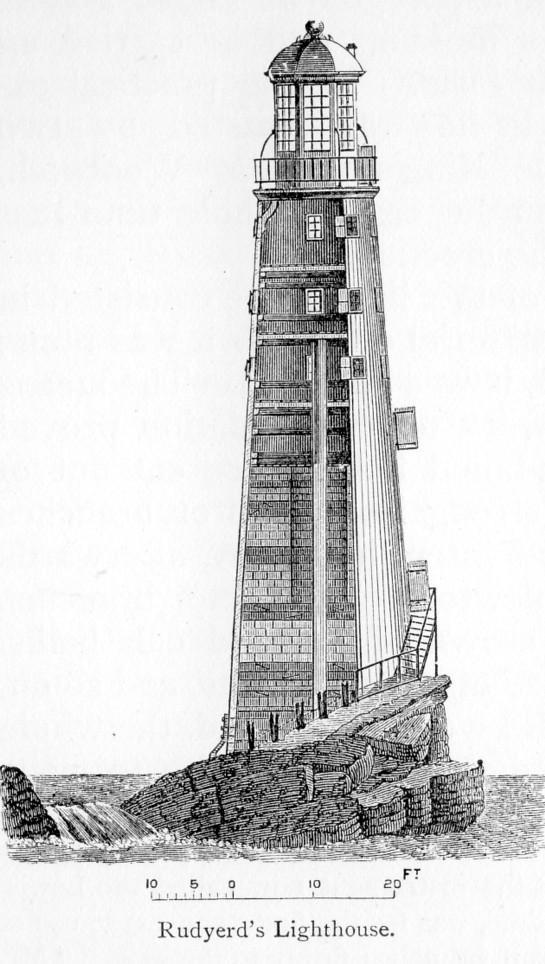

A new architect was not long in making his appearance.

He did not, however, come from the class of architects, or builders,

or even of mechanics: and, as for the class of engineers, it had not

yet sprung into existence. The projector of the next

lighthouse for the Eddystone was again a London mercer, who kept a

silk-shop on Ludgate Hill. John Rudyerd—for such was his

name—was, however, a man of unquestionable genius, and possessed of

much force of character. He was the son of a Cornish labourer

whom nobody would employ,—his character was so bad; and the rest of

the family were no better, being looked upon in their neighbourhood

as "a worthless set of ragged beggars." John seems to have

been the one sound chick in the whole brood. He had a

naturally clear head and honest heart, and succeeded in withstanding

the bad example of his family. When his brothers went out

a-pilfering, he refused to accompany them, and hence they regarded

him as sullen and obstinate. They ill-used him, and he ran

away. Fortunately he succeeded in getting into the service of

a gentleman at Plymouth, who saw something promising in his

appearance. The boy conducted himself so well in the capacity

of a servant, that he was allowed to learn reading, writing, and

accounts; and he proved so quick and intelligent, that his kind

master eventually placed him in a situation where his talents could

have better scope for exercise than in his service, and he succeeded

in thus laying the foundation of the young man's future success in

life.

We are not informed of the steps by which Rudyerd worked his

way upward, until we find him called from his silk-mercer's shop to

undertake the rebuilding of the Eddystone Lighthouse. But it

is probable that by this time he had become known for his mechanical

skill in design, if not in construction, as well as for his

thoroughly practical and reliable character as a man of business;

and that for these reasons, amongst others, he was selected to

conduct this difficult and responsible undertaking.

After the lapse of about three years from the destruction of

Winstanley's fabric, the Brethren of the Trinity, in 1706, obtained

an Act of Parliament enabling them to rebuild the lighthouse, with

power to grant a lease to the undertaker. It was taken by one

Captain Lovet for a period of ninety-nine years, and he it was that

found out and employed Rudyerd. His design of the new

structure was simple but masterly. He selected the form that

offered the least possible resistance to the force of the winds and

the waves, avoiding the open galleries and projections of his

predecessor. Instead of a polygon he chose a cone for the

outline of his building, and he carried up the elevation in that

form. In the practical execution of the work he was assisted

by two shipwrights from the King's yard at Woolwich, who worked with

him during the whole time that he was occupied in the erection.

The main defect of the lighthouse consisted in the faultiness

of the material of which it was built; for, like Winstanley's, it

was of wood. The means employed to fix the work to its

foundation proved quite efficient; dove-tailed holes were cut out of

the rock, into which strong iron bolts or branches were keyed, [p.123]

and the interstices were afterwards filled with molten pewter.

To these branches were firmly fixed a crown of squared oak balks,

and across these a set of shorter balks, and so on, till a basement

of solid wood was raised, the whole being firmly fitted and tied

together with trenails and screw-bolts. At the same time, to

increase the weight and vertical pressure of the building, and

thereby present a greater resistance to any disturbing external

force, Rudyerd introduced numerous courses of Cornish moorstone, as

well jointed as possible, and cramped with iron. It is not

necessary to follow the details of the construction further than to

state, that outside the solid timber and stone courses strong

upright timbers were fixed, and carried up as the work proceeded,

binding the whole firmly together.

Within these upright timbers the rooms of the lighthouse were

formed, the floor of the lowest, the storeroom, being situated

twenty-seven feet above the highest side of the rock. The

upper part of the building comprehended four rooms, one above

another, chiefly formed by the upright outside timbers, scarfed that

is, the ends overlapping, and firmly fastened together. The

whole building was, indeed, an admirable piece of ship-carpentry,

excepting only the moorstone, which was merely introduced, as it

were, by way of ballast. The outer timbers were tightly

caulked with oakum, like a ship, and the whole was payed over with

pitch. Upon the roof of the main column Rudyerd fixed his

lantern, which was lit by candles, seventy feet above the highest

side of the foundation, which was of a sloping form. From its

lowest side to the summit of the ball fixed on the top of the

building was ninety-two feet, the timber-column resting on a base of

twenty-three feet four inches. "The whole building," says

Smeaton, "consisted of a simple figure, being an elegant frustum of

a cone, unbroken by any projecting ornament, or anything whereon the

violence of the storms could lay hold." The structure was

completely finished in 1709, though the light was exhibited in the

lantern as early as the 28th of July, 1706. [p.125]

That the building erected by Rudyerd was on the whole well

adapted for the purpose for which it was intended, was proved by the

fact that it served as a lighthouse for ships navigating the English

Channel, and withstood the fierce storms which rage along that part

of the coast, for a period of nearly fifty years. The

lighthouse was at first attended by only two men, as their duty

required no more. During the night they kept watch by turns

for four hours alternately, snuffing and renewing the candles.

It happened, however, that one of the keepers took ill and died, and

only one man remained to do the work. He hoisted the flag as a

signal to those on land to come off to his assistance; but the sea

was running so high at the time, that no boat could live in the

vicinity of the rock; and the rough weather lasted for nearly a

month.

What was the surviving man to do with the dead body of his

comrade? The thought struck him that if he threw it into the

sea, he might be charged with murder. He determined,

therefore, to keep the corpse in the lighthouse until a boat could

come off from the shore. One may imagine the horrors endured

by the surviving lightkeeper during that long, dismal month.

At last the boat came off, but the weather was still so rough that a

landing was only effected with the greatest difficulty. By

this time the effluvia rising from the corpse was overpowering; it

filled the apartments of the lighthouse, and it was all that the men

could do to get the body disposed of by throwing it into the sea.

The circumstance afterwards induced the proprietors to employ a

third man to supply the place of a disabled or dead keeper. [p.126]

The chief defect of Rudyerd's building, as we have already