|

LIVES

OF

SMEATON AND RENNIE.

____________

INTRODUCTORY CHAPTERS.

CHAPTER I.

SHIPPING AND HARBOURS.

THE Commercial

greatness of England is of almost as modern a character as its

Engineering. England had very little foreign commerce before

the middle of last century. It did not begin to assume any

special importance until the steam-engine had been invented by James

Watt.

The Maritime greatness of England is also of comparatively

recent growth. Although the sea is now regarded as the

national business of Englishmen, scarce two centuries have elapsed

since England was unable to defend her coasts against foreign

pirates.

At a time when Spain, Holland, France, Genoa, and Venice were

great maritime powers, England was almost without a fleet, its trade

with other countries being conducted principally in foreign ships.

Until the middle of the sixteenth century, the Foreign Company of

Merchant Adventurers monopolized almost the entire foreign trade of

London. Their headquarters were in the Hanse Towns of Germany,

and they carried on their trade with England under the protection of

a special code of mercantile law. They occupied large premises

in Upper Thames Street, London—where they had their Guildhall,

dwellings, and warehouses, surrounded by a strong wall,—together

with a wharf on the Thames. [p.2-1]

The privileges of the foreign merchants were withdrawn in

1552, because they were considered prejudicial to the growth of

native commerce; but what the state of the English merchant navy was

about that time, may be inferred from the fact stated by the

Secretary to the English Company of Merchant Adventurers, that in

1540 there were not more than four merchant ships of above

200 tons each, belonging to the river Thames! [p.2-2]

Bristol, then next in importance to London, possessed several

large foreign-built ships; but the principal craft belonging to that

port was only of from 50 to 100 tons burden. In Queen

Elizabeth's time Liverpool was a poor decayed town, and petitioned,

in 1571, to be relieved from a royal subsidy; the entire shipping of

the place amounting to only 223 tons,—the largest vessel being only

of 40 tons burden.

It is astonishing, however, to find what bold and daring

things were done by the Englishmen who navigated these ships.

The sea-going blood was in them, and wherever the ship would float,

the seamen were ready to go. Sir Humphry Gilbert crossed the

Atlantic, and sailed along the coast of America in the 'Squirrel,'

of only 10 tons! Sir Francis Drake's fleet, which left the

English shores for the circumnavigation of the globe, consisted of

five vessels, the largest of which was not of 100 tons burden. [p.3]

In those early days, the Companies of English Merchants seem

to have laid the foundations of our colonial greatness. They

were most enterprising in the discoveries which they promoted.

Thus the Merchant Adventurers of the Muscovy Company endeavoured to

find a way, by the North-East Sea, to Japan and China. The

brave navigator Hudson made his first voyage into the Frozen Seas in

an ill-found little little craft of about 80 tons, accompanied by a

crew of twelve men and a boy. Arthur Pet and Charles Jackman

penetrated to the Kara Sea through the Tugor Strait, in two little

ships—one of 40 tons, with nine men and a boy, and the other in a

boat of 20 tons, with five men and a boy.

Martin Frobisher was another of these early maritime heroes.

Under the patronage of some private persons, and of the Company of

Foreign Merchants, he set out, in the reign of Elizabeth, to

discover the North-West Passage to China. His fleet consisted

of two small craft of 24 tons each—scarcely the size of Thames

yachts, and both poorly found—accompanied by a pinnace of 10 tons!

And some years later—for the discovery of the North-West Passage

seems to have continued the dream of mariners down to our own

time—Robert Fotherby, in 1615, assisted by the East India Company

and the Company of Foreign Merchants, set out in the 'Richard,'

accompanied by Robert Baffin as his pilot, to discover the same

passage to glory and wealth.

The royal navy was on a par with the mercantile; and at the

time when the Spanish Armada bore down upon the English coast, it

consisted of only twenty-three ships, eight of which were under 120

tons. There were only nine of 500 tons and upwards, the ship

of the greatest burden being of 1000 tons, carrying only forty guns.

The principal part of the fleet which held at bay the Armada until

the storms had scattered it, were coasting-vessels of small burden,

belonging to Lyme, Weymouth, and other ports along the southern

coast. Of the whole seventy-five vessels which constituted the

squadron under the Lord Admiral and Sir Francis Drake, not fewer

than sixty were from 400 tons down to as low as 20 tons. About

the same period, the small but flourishing republic of Venice

possessed a fleet of more than three thousand vessels of various

kinds, carrying upwards of thirty-six thousand seamen.

The English navy, however, made gradual progress. Its

growth was quickened by the commercial spirit of the people.

In 1613 there were ten vessels of 200 tons belonging to the port of

London. The suppression of the foreign monopoly of the

carrying trade had the effect of giving a considerable impetus to

the English shipping business; and by the year 1640 we find the

number of ships and sailors more than trebled. We had not yet,

however, obtained our proper ascendency. Van Tromp was still

able to sail up the Channel with a broom at his masthead, showing

that he had swept his English foes from off the seas. The

Dutch, in fact, then displayed those qualities of commercial

enterprise, adventurous discovery, and fighting power at sea, on

which the English people now pride themselves.

The Dutch not only beat our fleets, but fished our coasts,

just as the English, Scotch, and French fishermen now fish the

coasts of Ireland; and the Dutch then upbraided us for our idleness

and stupidity, as we now upbraid the Irish. The writer of a

pamphlet published in 1614,—"Tobias Gentleman, a fisherman and

mariner,"—pointed to the great amount of wealth yearly taken out of

His Majesty's seas by the Hollanders, whereby they had grown rich

and powerful, possessed of a great fleet, and were able to dictate

terms to the Spaniards; whereas the English coasting people were

poor, idle, and negligent, and constrained even to beg bread of the

"plump Hollanders." Tobias was indignant at seeing the

foreigners, whose industry and diligence he nevertheless praised,

using our seas as a rich treasury, and drawing wealth from them as

from a gold-mine. Six hundred Dutch busses, of some six score

tons each, were employed in the herring-fishery along the British

coast,—from the mouth of the Thames as far north as

Shetland,—besides numerous others in the cod-fishery; protected by

some twenty, thirty, and even forty ships of war to prevent their

being pillaged by the Dunkirkers, who were the chief pirates of

those times.

That these Dutchmen should come into our markets and sell us

our own fish, carrying away great quantities of gold and silver,

whilst English ships lay rotting, was a thing that, Mr. Gentleman

thought, should not be borne. "It is much to be lamented," he

said, "though we have such a plentiful Country and Store of able and

idle people, that not one of His Majesty's Subjects is there to be

seen, all the whole Summer, to fish or to take one Herring: but only

the North-sea Boats of the Sea-coast Towns, that go to take Cods;

they do take so many as they need to bait their Hooks, and no more.

We are daily scorned by these Hollanders for being so negligent of

our Profit and careless of our Fishing; and they do daily flout us

that be the poor Fishermen of England, to our Faces at sea, calling

to us and saying, Ya English, ya zall or oud scone dragien,

which in English is this: You English, we will make you

glad to wear our old shoes." [p.6]

From this curious tract it would appear that much even of our

commonest English industry is of modern growth; and that the herring

fishery, which it might be supposed was indigenous in England, is as

modern as most other branches of employment. Down to about the

end of last century the only fishing was conducted close in-shore,

the fishermen shooting the nets from their small cobles; and it was

not until the year 1787 that the Yarmouth men began the deep-sea

herring fishery. [p.7-1]

Another remarkable feature of those early times was the

piracy which prevailed round the English coasts. The seas were

as unsafe as the roads, and a system of plundering passing ships was

as common as that of robbing mail-coaches. Sea-roving

doubtless ran in the blood of the coast population, themselves the

descendants of the pirate Northmen. There were many daring

spirits amongst them, and when a bold leader started up and fitted

out a ship to make a dash at Spanish galleons, or a descent on the

French coast, he had never a lack of desperadoes to follow

him—thorough-going seamen, equally ready to brave the storm and the

battle—to face the hurricanes of the Atlantic in a cock boat, or to

fight against any odds. Hence Scaliger, when describing the

English of his day, said of them, "They make excellent sailors and

pirates" "Nulli' melius piraticam exercent quam Angli." [p.7-2]

Drake sailed along the Spanish main, sacked the Spanish

towns, burnt the Spanish ships, and carried off their gold, although

no declaration of war had yet been made by Elizabeth against Spain.

Drake's vessels were the property of private persons, who sent them

forth upon adventure on the high seas; and there were not wanting

others to follow his example, especially after war had been declared

between the two countries. The records of the Corporation of

London contain some curious entries relative to the fitting out of

ships, which were sent to sea, for the capture of Spanish galleons

and the subsequent division of the spoil. In 1593 we find a

richly-laden carrack captured by Sir Walter Raleigh, and brought

into the Thames a prize. On the 15th of November, in that

year, a Committee was appointed "on behalf of such of the City

Companies as had ventured in the late fleet, to join with such

honourable personages as the Queen hath appointed, to take a perfect

view of all such goods, prizes, spices, jewels, pearls, treasures,

&c., lately taken in the carrack, and to make sale and division

thereof" [p.8] It appears

that about £12,000 (then about four times the value of our present

money) was divided amongst the Companies who had adventured, and

that about £8,000 was similarly netted by them on a subsequent

occasion.

Similar ventures were often made, both before and after

Raleigh's time. In Richard II.'s reign, one Philpot hired a

thousand men and sent them to sea, where they captured fifteen rich

Spanish vessels.[p.9-1]

Harry Page, of Poole, ravaged the coasts of Spain, France, and

Flanders, bringing home the plunder of many churches, numerous

prisoners, and prizes laden with rich cargoes.

But the piratical propensity was not only displayed against

our continental neighbours, but by the seagoing population of one

town against those of another. In 1342 Yarmouth and Hull sent

out a piratical fleet against London and Bristol; and ports as near

each other as Lyme and Dartmouth, in the adjoining counties of

Dorset and Devon, waged deadly feud and strove to capture each

other's vessels. [p.9-2]

The sailors of the Cinque Ports were at war with those of

Yarmouth, and in Edward I.'s reign, regular safe conducts were

granted to certain Cinque Ports vessels requiring to visit that

port, as if it were an enemy's. The Yarmouth men were even at

war with those of Lowestoft, Camden relating of them that "they

often engaged their neighbours, the Lestoffenses, or men of

Lowestoff, in sea-fights, with great slaughter on both sides."

Robert de Battayle, of Winchelsea, plundered a passing ship

belonging to some merchants of Sherborne; but the feat must have

been regarded as creditable, for a few years later his townsmen

chose him for their mayor. At the end of the sixteenth century

three noted pirates—Hamilton, Twittie, and Purser—ravaged the coasts

of the south-western counties. In 1582 Purser attacked the

ships, both English and French, riding in Weymouth Harbour, and

carried off a Rochelle ship of 60 tons. But Weymouth itself

also sent out piratical vessels, which picked up many rich prizes.

Down even to the middle of the seventeenth century piracy was

quite common along the Devonshire coast. The weakness of the

royal navy is sufficiently obvious from the fact that Turks and

Algerines sailed along the Channel, up the Severn, and into the

Irish Sea, capturing ships; while the Dunkirk pirates assailed with

impunity the east coast towns, from Dover to Berwick-upon-Tweed.

The Emperor of Morocco was even bribed to cease from his piratical

expeditions and to protect British trade; and the bribe continued to

be paid until the year 1690. Sea-robbers were masters of the

Channel as late as the reign of Charles I. [p.10]

When piracy was at last put a stop to along the English

coasts, the more desperate pirates took service under the Turks,

while many more sailed away to the West India Islands and turned

buccaneers. [p.11] Hugh

Miller, in his autobiography,

speaks of his great-grandfather, John Feddes, as "one of the last of

the buccaneers;" and he states that the house in which he himself

was born "had been built, he had every reason to believe, with

Spanish gold."

Such being the early state of British shipping, there was

very little need of harbours. The navigable tidal rivers were

found amply sufficient for the accommodation of the shipping, then

of comparatively small burden, by means of which trade was then

carried on. London possessed a great advantage in her fine

river, the Thames, up which the natural power of the tide lifted

vessels of the largest burden into the heart of the land, and

lowered others down again to the sea, twice in every twenty-four

hours. The river served as harbour, dock, and depot in one,

and provided ample waterway, with abundant quay accommodation, which

sufficiently served the purposes of trade down almost to our own

day.

Among the early ports, Bristol ranked next in importance to

London: it was also provided with a convenient river, the Avon, up

which ships were floated by the tide to port. At the siege of

Calais, in Edward III.'s time, Bristol furnished almost as many

ships and mariners as London; and it went on increasing in

importance down to the end of the seventeenth century.

Liverpool was then scarcely known as a seaport, and, indeed, was

little better than a fishing village. Before the art of

engineering had advanced so far as to enable harbour walls to be

built in deep water, the tidal rivers sufficiently answered the

purpose of harbours. Hence London on the Thames, Bristol on

the Avon, Hull on the river Hull, Chester (the principal

shipping-port for Ireland) on the Dee, Gloucester on the Severn,

Boston on the Witham, and Newcastle on the Tyne.

At Bristol the ships lay upon the mud at low water, the

course of the river Froom having been turned, in early times, in

order to make "a softe and whosy (oozy) harboure for grete shippes;"

and the habit of lying on the mud made the Bristol ships so bulge

and swell out, that until quite recently "a Bristol hog" could be

recognised by the practised sailor's eye far off at sea.

Bristol was only provided with floating docks at the beginning of

the present century, long after Liverpool had overcome the

difficulties of the currents in the Mersey, and provided for herself

a system of docks, now considered superior to everything else of the

kind in the world.

The ample line of the British coast, broken by innumerable

deep-water bays and inlets, also afforded considerable convenience

for the shipping of early times. The small size of the craft

enabled them to be beached with ease, and the utmost that was done

in the way of harbour works was to empty large stones roughly into

the sea so as to form a breakwater or a pier at the harbour head.

But the sea was found a fickle and dangerous neighbour, and those

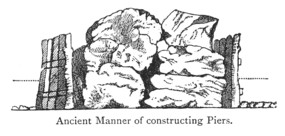

early works were often washed away. Mr. Roberts gives the

rough representation, shown in the annexed cut, of the mode of

constructing the ancient pier at Lyme Regis; and most probably the

same method was pursued elsewhere.

The rocks which lay upon the shore were floated over the line

of the proposed sea-work by means of casks, and dropped into their

places. Strong oak piles were then driven into the ground

along either side of the rocks for the purpose of holding them

together. Great reliance was placed upon timber, and

especially upon oak.

The Cob or harbour at Lyme Regis [p.13]

was so successfully put together in this way, that Queen Mary

ordered the workmen to be impressed and forwarded to Dover, to

execute a similar work for the protection of the harbour at that

place. They were next employed at Hastings, where they reared a pier

of huge rocks edgeways, but without timber. But the seas of the

ensuing winter completely overthrew the structure; and again, in

1597, the workmen erected another pier, using much timber in

cross-dogs, bars, and braces. The work was thirty feet high, "bewtyfull

to behold, huge, invariable, and unremoveable in the judgment of all

beholders;" but on the next All Saints day a storm upon a spring

tide scattered the whole, and to this day Hastings remains without a

stone pier. |

The Cob at Lyme Regis [p.14].

© Copyright

David Lally and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

Among the numerous fine natural harbours on the south coast

were those of Portsmouth, Plymouth; Weymouth, Falmouth, and

Dartmouth, all situated at the mouths of rivers or bays, as their

names indicate. None of them had piers until a comparatively

recent date, the only landing-places at Portsmouth and Southampton

being on "the Hard." The Cinque Ports, on the coast of Kent,

were mostly beach harbours, and were constantly liable to be choked

up by the gradual movement of the shingle up Channel; so that

Winchelsea, Romsey, and Hythe thus became completely lost. For

the same reason Dover was always a port most difficult to be

preserved. The shingle, rolling along the coast by the

south-westerly winds, blocked up the port by a bank which extended

from east to west, until the pent-up inland waters, collecting

behind it, forced their way to sea, thus maintaining an opening more

or less partial.

Various attempts were made to preserve Dover Harbour in early

times, the most important improvements being those conducted by Sir

John Thompson, master of the Maison Dieu in the reign of Henry VIII.

He enclosed a small basin with a quay by driving two rows of piles

into the sea bottom as far out as the Mole Rock, and filling in the

interstices with blocks of stone and chalk. The stones were

floated along shore from Folkestone by means of empty casks, as at

Lyme. It is said that not less than £50,000 were expended on

these works; but the imperfect manner in which they were constructed

may be inferred from the fact that the sea very soon made several

breaches in the wall and the pier, and the beach accumulated, as

before, all round the bay, so that a boat drawing only four feet of

water could scarcely enter the harbour.

Foreign engineers were then called in—amongst others,

Ferdinand Poins, a Fleming, and Thomas Diggs, who had studied

harbour construction in the Netherlands; and various additions were

made by them to the works in the reigns of Elizabeth and James.

The harbour was always, however, in danger of becoming silted up

down to our own times; and the improvement of it formed the subject

of repeated reports of Perry, Smeaton, Rennie, and

Telford.

Along the east coast of England, the early harbours were few

and bad. Thoresby relates that in his time (1682) Whitby, in

Yorkshire, possessed a harbour formed by a rough quay projecting at

the mouth of the river; but he adds that there was no other haven

for ships between that place and Yarmouth, in Norfolk.

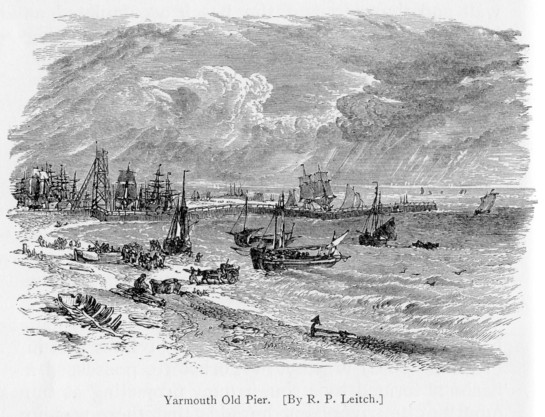

Yarmouth has, like Dover, been the subject of much unavailing

engineering, in consequence of the peculiar difficulties of its

situation. It stands on the banks of the rivers Yare and Burr,

from the former of which it received its name. It was always

liable to be silted up by the sands which abound along shore.

Nevertheless it continued to maintain some trade; and down to the

time of Henry VIII. it was regarded as the most important maritime

town along the east coast. But the channels leading to it were

so liable to become choked up, that its prosperity was very

irregular, and sometimes its navigation was all but lost.

The Yarmouth people were reduced to even greater straits than

ordinary in the reign of Elizabeth, when they adopted the usual

expedient of sending abroad for an engineer of reputation to recover

their navigation; and Joyse Johnson, a celebrated man in his day,

came over from Holland to direct the works. He caused a strong

pier of piles to be formed, which had the effect of directing the

current in such a manner, in a north-easterly direction, as to give

a temporary relief. The difficulty, however, was not

surmounted, as we still find the inhabitants fighting against the

sea-banks which hemmed in the port, during the reigns of James and

Charles, and even during the Commonwealth; until eventually a south

pier was formed, the continuation of which, in a fine curve, was

carried up the river, and formed an extensive wharf, affording

considerable accommodation and security for shipping. The

original north pier was subsequently abandoned, and a new north pier

was erected, on a plan chiefly intended to assist in warping ships

into the harbour.

Yarmouth long had a weather-beaten jetty—a great favourite

with landscape painters—which extended into the sea on the eastern

side of the town. On this site a jetty was built in 1560, with

a crane at the end to facilitate the landing of goods. It was

rebuilt in 1808, and became one of the principal landing-places on

the east coast. Exiled sovereigns landed there to seek the

shelter of England, and embarked there to seek the returning loyalty

of their subjects. Nelson twice landed there, amidst

enthusiasm, to receive the embraces of his countrymen.

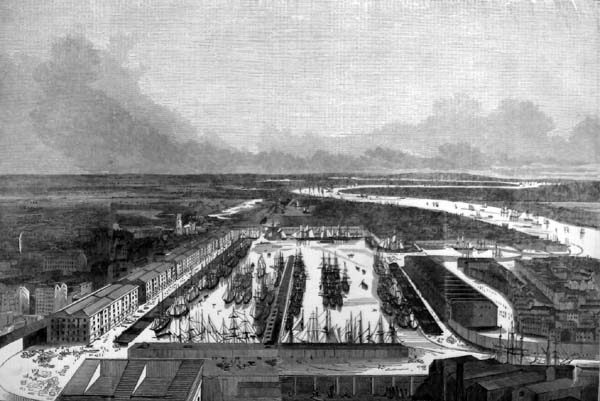

The English docks, which are now the pride of English

engineers, have for the most part been constructed during the

present century. Liverpool set the example of dock-making at

the beginning of last century, and it has continued to keep the lead

of all other towns and cities to this day. The first dock

constructed in Great Britain was "The Old Dock" at Liverpool, under

the powers of an Act passed in the eighth year of Queen Anne's

reign, [p.18] when the population

of the town was under 6,000 in number. The Liverpool people

were perhaps forced by necessity to make the dock. Sandbanks

were closing up the Dee, and driving the little shipping there was

from Chester to Liverpool. But the ships, when lying in the

rapid current of the Mersey—which was also exposed to the heavy

gales from the westward—could not easily be unloaded; and it was

consequently found necessary to make inlets or docks along the

strand, for the purpose of giving the ships shelter during the

process of loading and unloading. Hence the first Act to

provide Liverpool with a dock. It not only afforded 652 feet

of quay space for the shipping, but it was shut in from the tides by

means of dock-gates, and was consequently a floating dock. In

1760 the Salthouse Dock was opened, and still later the George's

Dock. Dry docks were also provided, open to each tide, and

these are now mostly used for the purposes of the coasting-trade.

The King's Floating Dock was opened in 1785, and the Queen's

Dock in 1789. Then followed the great Prince's Dock, which was

opened in 1821, when the Old Dock, which could only accommodate

smaller ships, was filled up, and the modern Custom House was

erected on its site. The docks, which have since then been

constructed in Liverpool, are of immense magnitude. They

occupy about 300 acres, and are able to accommodate shipping of more

than five millions of tons burden.

There was no public dock on the Thames until the beginning of

the present century. There were two private docks: one, the

Greenland Dock, for whaling ships; the other, Mr. Perry's dock, for

the accommodation of East India ships. The Greenland Dock is

said to have included the commencement of Canute's Trench, stated,

on the authority of Stowe, to have been cut early in the eleventh

century from thence to Battersea. Mr. Perry was a

ship-builder, who constructed his private dock at Blackwall, for the

purpose of getting the East India shipping out of the river, and

placing them, and the traffic they contained, under lock and key.

Before there were any public docks on the Thames, the

merchandise was kept afloat in barges, for want of room to discharge

it at the legal quays. An Indiaman of 800 tons could scarcely

be delivered of her cargo in less than a month, and the goods had

then to be lightered from Blackwall nearly to London Bridge.

In addition to the rapid increase of foreign trade towards the end

of last century, there was also a rapid increase in the coal trade.

A strong prejudice had long existed in London and elsewhere,

as to the use of "sea-coal." Edward I. issued a proclamation

against its use, and a man was actually hanged during his reign, for

committing the crime of burning it within the limits of the City.

But as the forests became consumed for the production of "charre

coal" for domestic purposes, and for iron-smelting, [p.19]

there was no alternative but to fall back upon the rich stores of

coal found in the northern parts of England.

Then it was that the Newcastle coal shipping-trade sprang

into importance, and has ever since proved the principal nursery of

our seamen. The fleets of colliers entering the Thames, added

to the other shipping, caused a great throng of vessels in the

river; and what with the coal-lighters and merchandise-barges,—which

carried the goods and coal up the river,—and the warehouses and

coal-yards on shore, it became a very crowded and often a very

confused scene. The merchandise, borne from the vessels to the

warehouses, became liable to serious depredations; and the losses

from this cause, as well as the over-crowding of the river, at

length led to the provision of floating docks at various points, and

to a further vast development of the port of London.

The Thames was, for a long time, not only the harbour, but

the great silent highway of the Metropolis. The city lay

mostly along the banks of the river, and the streets and roads long

continued so bad, that passengers desiring to proceed eastward or

westward, almost invariably went by boat. There were also

ferry-boats constantly plying from side to side of the river, and so

long as London Bridge presented the only means of crossing by coach

or on foot, the number of persons daily using the ferries was

necessarily very considerable. A horse-ferry plied between

Lambeth Palace and Mill-bank, the tolls of which belonged to the

Archbishop of Canterbury, and there was another across the river at

Hungerford, both being rendered comparatively unnecessary when the

second bridge was erected at Westminster. The extent of the

river traffic may be inferred from the circumstance stated by Stowe,

that in his time the Watermen's Company could at any time furnish

twenty thousand men for the fleet. But as the streets of the

metropolis were improved, as more bridges were built, and when the

use of coaches had extended—against which the watermen strongly

protested—their numbers rapidly diminished, until at length they

have almost become extinct. |

London Docks in 1845. Illustrated London News.

|

While the engineering and shipbuilding of England were in so

backward a state, comparatively little use was made of the sea for

the purposes of travelling. The state of the roads prevented

travelling by land; the state of the ships prevented travelling by

sea. Travelling by road was accompanied by the risk of highway

robbery, and travelling by sea was accompanied by the risks of

piracy and shipwreck.

At the present time, when a steamship can make the voyage

between England and Australia with such regularity that you may

count upon her arrival almost within three days, and when steamers

of thousands of tons burden sail almost daily between New York and

Liverpool, and their arrival may be depended upon to a day and

almost to an hour, the loss of time in long and even short voyages,

would now be regarded as something extraordinary. A passage

might be made in a Leith smack between London and Edinburgh in four

or five days; but during contrary winds, it might last for three or

four weeks; and the smack might in the meanwhile be driven over to

the coasts of Norway. At the beginning of the present century

it took six weeks to bring the North Cork regiment of militia from

Cork Harbour to Colchester.

There was a considerable difference in getting from London to

the Continent in the old times and the new. The ancient

Continental route used to be through Gravesend Manor, belonging to

the Abbot of Tower Hill, who, "finding that by the continual

recourse to and from Calais, the passage by water between London and

Gravesend was much frequented, both for the great ease, good, cheap,

and speedy transportation (requiring not one whole tide), made offer

to the young King Richard the Second, that if he would be pleased to

grant unto the inhabitants of Gravesend and Milton the privilege

that none should transport any passengers by water from Gravesend to

London but they only, in their own boats, then should they, of these

two parishes, undertake to carry all such passengers, either for

twopence each one with his farthell (a truss of straw) or otherwise,

making the whole fare or passage worth four shillings." [p.22]

To this proposal the King consented, and hence the route to and from

the Continent long continued to be by Gravesend. Ambassadors

to the Court usually took boat at Gravesend for London; and perhaps

a finer entrance into the great Capital of the kingdom could not

have been selected.

The comfort of the Long Ferry for the commoner sorts of

people could not, however, have been very great. The

passengers were required to bring with them their respective trusses

of straw to lie on. They were also, when the tide was low,

under the necessity of landing in the mud a mile or two short of

their destination, and either wade their way to shore or pay for

being carried thither on the backs of mud-larks. The boatmen

only rendered themselves liable to a penalty if they landed the

passengers more than two miles short of their destination!

Fielding has left an account, in his 'Voyage to Lisbon,' of

the tediousness and discomfort of voyaging, about the middle of last

century. His ship was fixed to sail from opposite the Tower

Wharf at a certain time, when Fielding, ghastly and ill, was rowed

off to it in a wherry, running the gantlope through rows of sailors

and water-men, who jeered and insulted him as he passed. The

ship, however, did not set out for several days, and Fielding was

compelled to spend the intervening time in the confines of Wapping

and Redriff. The vessel at length sailed, and, reaching

Gravesend, anchored for the night. Next evening they sailed

for the Nore, and the day after that they anchored off Deal, and lay

there for a week. It took four days more to beat down Channel

to Ryde, where Fielding was landed in the mud fifteen days after his

embarkation at the Tower; and a long, long time elapsed before the

termination of his voyage at Lisbon.

When coaches began to run upon the improved road between

London and Dover, passing by Blackheath and Dartford to Rochester

and Canterbury, the principal part of the continental traffic was

diverted from Gravesend, though the comfort of the journey does not

seem to have been very much improved. Smollett gives a rather

dismal account of his progress from London to Boulogne in 1763,

which presents a curious contrast to the facilities of travelling by

the modern Boulogne steam route. After tediously grumbling his

way through Rochester and Canterbury, fleeced by every innkeeper on

the road, he at last reached Dover in a very bad temper. He

pronounced the place to be a den of thieves, where the people live

by piracy in time of war, and by smuggling and fleecing strangers in

time of peace. He did them the justice, however, to admit,

that "they make no distinction between foreigners and natives.

Without all doubt a man cannot be much worse lodged and worse

treated in any part of Europe; nor will he in any other place meet

with more flagrant instances of fraud, imposition, and brutality.

One would imagine they had formed a general conspiracy against all

those who go to or return from the Continent."

But Smollett's troubles had scarcely yet begun, as he found

to his cost before he reached Boulogne. He sent for the master

of the packet-boat—a comfortless tub, called a Folkestone cutter—and

hired it to carry him across the Strait for six guineas, the master

demanding eight. "We embarked," he says, "between six and

seven in the evening, and found ourselves in a most wretched hovel.

The cabin was so small that a dog could hardly turn in it, and the

beds put me in mind of the holes described in some catacombs, in

which the bodies of the dead were deposited, being thrust in with

the feet foremost: there was no getting into them but endways, and

indeed they seemed so dirty, that nothing but extreme necessity

could have obliged me to use them. We sat up all night in a

most uncomfortable situation, tossed about by the sea, cold and

cramped, and weary and languishing for want of sleep. At three

in the morning the master came down and told us we were just off the

harbour of Boulogne; but the wind blowing off shore he could not

possibly enter, and therefore advised us to go ashore in the boat."

Smollett went on deck, when the master pointed out through

the spray raised by the scud of the sea where the harbour's mouth

lay. The passengers were so impatient to get on shore, that

after paying the captain and "gratifying the crew" (which was no

easy matter in those days), they committed themselves to the ship's

boat to be rowed on shore. They had scarcely, however, got

half way to land, before they perceived a boat coming off to meet

them, which the captain pronounced to be the French boat, and that

it would be necessary to shift from the one small boat to the other

in the open sea, "it being a privilege of the boatmen of Boulogne to

carry all passengers ashore."

Smollett then proceeds:—

"This was no time or place to remonstrate. The

French boat came alongside, half filled with water, and we were

handed from the one to the other. We were then obliged to lie

upon our oars till the captain's boat went on board, and returned

from the ship with a packet of letters: we were then rowed a long

league in a rough sea, against wind and tide, before we reached the

harbour, where we landed, benumbed with cold, and the women

excessively sick. From our landing-place we were obliged to

walk very near a mile to the inn where we purposed to lodge,

attended by six or seven men and women, barelegged, carrying our

baggage. This boat cost me a guinea, besides paying

exorbitantly the people who carried our things; so that the

inhabitants of Dover and Boulogne seem to be of the same kidney, and

indeed they understand one another perfectly well." [p.26]

The passage of the ferry between England and France continued

much the same until a comparatively recent period; Fowell Buxton

relating that as late as the year 1817 the packet in which he sailed

from Dover to Boulogne drifted about in the Channel for two days and

two nights, and only reached the port of Calais when every morsel of

food on board had been consumed. Steam has entirely altered

this state of things, as every traveller knows; and the same passage

is now easily and regularly made four times a day, both ways, in

about two hours.

The passage of ferries in the northern parts of England was

equally tedious, uncomfortable, and often dangerous. In 'A

Tour through England in 1765,' it is stated that at Liverpool

passengers were carried to and from the ferry-boats which plied

three times a day to the opposite shore, "on the backs of men, who

wade knee-deep in the mud to take them out of the boats."

Between Hull and Barton a packet plied once a day across the

Humber, the travellers wading to the boats through a long reach of

mud; but whether the voyage would occupy two hours or a day, no one

could predict when embarking. If the weather looked

threatening, the travellers would take up their abode at the

miserable inn on the Barton side until the wind abated. Now

the voyage is regularly and frequently performed every day, to and

from New Holland, in less than half-an-hour.

The ferry of the Frith of Forth was also a formidable affair,

and a voyage to Fife was often full of peril. The passage to

Kinghorn or Burntisland was made in an open boat or a pinnace, and

the boatmen usually waited, it might be for hours, until sufficient

passengers had assembled to go across. The difficulty of

passing the Forth ferries was experienced by Mr. Rennie as late as

1808, when returning across the Frith from Pettycur, where he had

been examining the harbour with a view to its improvement for the

packet-boats which plied between there and Leith. "The wind

blew fresh," he says, "from about three points westward of South,

and after beating about in the Frith for nearly three hours, we were

obliged to return to Pettycur; and, to save time, I went round by

Queen's Ferry," a place nine miles to the westward, from whence it

was three miles across the Forth, and then other nine miles to

Edinburgh; the distance directly across from Pettycur being only

seven miles. This state of things, we need scarcely add, has

been entirely altered by the facilities afforded by modern steam

navigation.

The passage of the Bristol Channel was equally uncertain and

dangerous. Gilpin gives a graphic account of the perils of his

voyage across from Cardiff in 1770, in his 'Observations on the

River Wye.' On descending towards the beach he heard the

ferryman winding his horn, as a signal to bring down the horses.

The old ferry-boat was usually furnished with falling ends for the

admission of cattle and heavy articles; and where the ferry was

across a river, there was usually a chain passing along the side of

the boat on pulleys, and fixed to each bank, by which it was hauled

across. But from Cardiff to the other side of the Bristol

Channel was several miles, and it was accordingly rather of the

nature of a voyage. The same morning on which Gilpin crossed,

the ferry-boat had made one ineffectual attempt to make the farther

side at high water; but after toiling three hours against the wind,

it had been obliged to put back.

When the horses were all on board, the horn again sounded for

the passengers. "A very multifarious company assembled," says

Gilpin,

"and a miserable walk we had to the boat, through

sludge, and over shelving, slippery rocks. When we got to it

we found eleven horses on board and above thirty people; and our

chaise (which we had intended to convert into a cabin during the

voyage) slung into the shrouds. The boat, after some

struggling with the shelves, at length gained the Channel. After

beating about for near two hours against the wind, our voyage

concluded, as it began, with an uncomfortable walk backwards through

the sludge to high-water mark."

The passage of this ferry was often attended with loss of

life when the tide ran strong and the wind blew up Channel.

Moreover, the ferrymen were by no means skilful in the management of

the boat. A British admiral, who arrived at one of these

ferries, and intended to cross, observing the boat as she worked her

way from the other side, declared that he durst not trust himself to

the seamanship of such fellows as managed her; and turning his

horse, he rode some fifty miles round by Gloucester!

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

BEACONS AND LIGHTHOUSES.

LIKE our docks

and harbours, our lighthouses are among the youngest triumphs of

modern engineering. Everything in England is young. We

are an old people, but a young nation. Our trade is young; our

mechanical power is young; our engineering is young; and the

civilisation of what are called "the masses" has scarcely begun.

Not a hundred years have elapsed since the best prize that could

befall the barbarians of Devon and Cornwall was a rich shipwreck,

and when false lights were displayed on shore to lure the passing

vessel to its destruction. [p.30]

The lighting up of our coast by means of beacons and

lighthouses for the purpose of insuring greater safety to ships

approaching our shores by night, received very little attention in

early times. So long as the mercantile navy was comparatively

insignificant, and the amount of our foreign trade was but small,

the lighting up of our shores after dark was of much less importance

than it is now.

It was only when the commerce of the country began to develop

itself—when our merchants sent out their vessels richly freighted to

all parts of the world, and the sea was made a great highway for

English trade and commerce—that it became a matter of absolute

necessity, as well as of simple economy, to render the sea highway

as safe as possible, by planting lighthouses upon all the dangerous

rocks and headlands round the coast.

The idea of the Lighthouse is, of course, very old. The

ancient commercial nations were familiar with its use. They

erected, a tower on some dangerous part of the coast, which was a

landmark by day and a lighthouse by night. The Phœnicians,

though they did not go far out to sea, but crept cautiously along

shore, had marks by which they could easily sail along from one part

of the shore to another. The Colossus of Rhodes is supposed to

have been a gigantic brazen statue, surmounted by a hand bearing a

lighted chauffer, for the guidance

The most distinguished of the early lighthouses was that

erected on the Island of Pharos, at the mouth of the Nile. The

island is now connected with the mainland, and forms the site of the

modern Alexandria. From that early lighthouse, all subsequent

ones built by the Romans were called after the name of the

island—Pharos. Many were erected along the most frequented

parts of the Latin coast. One of the most remarkable was that

built by Claudius at Ostea the chief port of ancient Rome.

Pliny mentions those built at Ravenna, Pozziola, and Messina; and

also the Pharos of the Isle of Capri, which was overthrown by an

earthquake a few days before the death of Tiberius.[p.32]

The Pharos of Alexandria: an impression by German

archaeologist Prof. H. Thiersch (1909) [p.31].

Picture Wikipedia.

The most important lighthouses erected by the Romans in the

North of Europe were those erected on the heights above Boulogne,

and on the heights above Dover. Their object was to light

vessels passing across the Channel from one port to the other, and

also those passing from the coasts of France to their stations at

Portus Rutupiæ (now Richborough), near Sandwich, or to Regulbium

(now known as Reculvers) on the Thames, by way of the channel which

then separated the Isle of Thanet from the mainland.

The tower at Boulogne is supposed to have been erected by

Caligula. The original name was the Turris Ardens, but

this eventually became corrupted into Tour d'Ordre. It

was repaired by Charlemagne in the ninth century, and continued to

exist until the sixteenth century, when Boulogne was in the hands of

the English. It was then surrounded by ramparts, and provided

with artillery, which were used to command the town and the entrance

to the port. Quarries have been dug out where it stood, the

cliff has also fallen away, and the site of the Tour d'Ordre has

long been destroyed.

From a description of the Pharos left by Claude Châtillon,

engineer of Henry IV., it would appear that it was built about a

stone's throw from the edge of the cliff, above and overlooking the

high tower and the castle. The tower was octagonal in shape.

At the base it was 192 feet in circumference, and about 64 in

diameter. It was constructed of grey stone, with thin red

brick, and yellow stones laid across at intervals. It was

built in two stories, each retiring about a foot and half inside the

other, so that it had, in some measure, the form of a pyramid.

Each story had an opening towards the sea, of about the size of an

ordinary door. There is also supposed to have been a chamber

to contain the light, above the two stories, which, however, had

ceased to exist at the date at which it was examined by M.

Châtillon.

|

The Pharos at Dover Castle.

© Copyright

Steve Brown and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

The sister Pharos at Dover is of a similar character to that which

existed at Boulogne. It is also of Roman build, as is apparent

by the foundations being laid in a bed of clay, and by the Roman

tiles, of the usual depth, laid in tiers across the work, and

falling into each other like a half-dovetail, thereby rendering them

close and compact. The Pharos occupies the highest point of

the lofty rock on which the castle is built, and commands the

English Channel as far as the eye can see. The coast of

France, with Cape Grinez in the foreground, lies exactly opposite.

The tower is octagonal without, and square within. At the base

it is about 33 feet in diameter, and, originally, it may have been

about 72 feet high. At the summit it has three round holes on

the three exterior sides, evidently for the purpose of a look-out,

or for showing a light seawards.

Bede seems to have been under the impression that the Romans,

during their long stay in Britain, erected lighthouses at different

parts of the coast. Thus he interprets Streonshalh (the name

of Whitby, in Yorkshire, in his time) into Sinus Fari, the

bay of the lighthouse. The Romans had a road from York to

Dunum Sinus, now Dunsley Bay, a few miles to the north-west of

Whitby; and on an eminence in the midst of the village of Dunsley

there still remain the ruins of a building which at one time may

have been the guide-tower to the navigation, and thus gave rise to

Bede's name of the Bay. [p.34]

Bede also relates that, before the Romans left, they built

towers along the sea-coast to the southward, because there also the

irruptions of the barbarians were apprehended, "and so they took

leave of their friends, never to return again." [p.35]

The southern coast of England was in those days subject to the

frequent attacks of Frisian and Saxon pirates—and hence the

appointment, during the Roman days, of a Duke of the Saxon

shore—which shore included the opposite coasts of both France and

England. The towers may have been erected along the English

shore, as our Martello towers were erected some seventy years

ago—and they may, possibly, have been used as lighthouses for the

purpose of warning the people inland of the appearance of the

pirates; but this is merely a supposition.

Many centuries elapsed after the Romans had left England,

before anything further was done to light up the coasts by night.

There was no necessity for doing so. The country had no

commerce, no shipping, and was very thinly peopled. What

civilisation the Romans had left was rapidly dying out. Then

foreigners began to land from the opposite coasts. They

planted themselves firmly on the soil, and made Britain their home.

It took a long time for them to grow into a maritime people.

They merely came across in boats from the nearest points of the

opposite coast; and, with a fair wind, the voyage might be made in

daylight within a few hours.

It was not until the piratical Northmen began to cruise along

our shores, that beacons and fire-towers began to be erected along

the coasts, sometimes by the natives to warn the people inland

against their arrival, and at other times by the pirates themselves

to guide them on their way. The Norsemen knew every headland

along the coast; and the names they gave them are retained to this

day. From Dungeness and Grinez in the South, to Caithness in

Scotland, and the Naze in Norway, the names of the headlands round

the German Ocean are mostly of Norse derivation. The Northmen

were among the first to navigate the Irish Sea, and along the west

coast of England and the east coast of Ireland, they gave names to

most of the projecting headlands along the coast.

Near the entrance to the river Boyne, there is a solid mass

of masonry known as "The Finger," an ancient landmark, and probably

a fire-beacon, erected by the Northmen, who then held possession of

Dublin, of Wexford, of Waterford, and of Limerick, and had extensive

colonies settled in different parts of Ireland. On the

opposite coast, in England and Wales, they had similar beacons and

fire-towers. Near St. Ann's Head, at the northern entrance to

Milford Haven, in Wales, there are the remains of an ancient beacon

and lighthouse, which was all the more necessary to give light to

the Norse ships entering the port,—as Milford Haven was the

favourite piratical station of the Northmen, from which they made

their descents upon Ireland, or on the Western Counties of England

from Cornwall to Gloucester.

The Northmen had also settlements in the Isle of Man and the

Northern Counties of England. At the entrance to Morecambe Bay

there is a small island called the Isle of Walney, at the southern

end of which is a place still called Peel. It was originally

so called because of a pile or tower that served for a lighthouse to

guide the Northmen on their voyages from the Isle of Man to

Lancaster; and the neighbouring headland became known as Fire-ness

or Furness, which it retains to this day. Flamborough, on the

eastern coast of England, was also in early times used by the Danes

or Northmen as a lighthouse; and the name speaks of the rude fires

of coal or wood that used to "flame" by night on that dangerous

headland.[p.37] The Danes

held a large area of nearly three thousand acres, enclosed by a

formidable rampart—still called the Danes' Dyke. They

most probably occupied it permanently, or, at all events, between

the successive arrivals of their fleets; when it was necessary to

light up the headland to direct their ships to the landing-place

situated in the bay immediately under the Head.

South of Flamborough is a very dangerous part of the coast

adjoining the northern entrance to the Humber. It is a narrow

tapering neck of land, about two miles in length, over which the sea

sweeps in high tides. The neck ends in Spurn Head. The

first occupant of this place was a courageous hermit, who built a

chapel to pray for poor mariners, and exposed a light in his windows

to guide them up the Humber at night. Another anchorite,

Richard Reedburrow, afterwards built a tower for a beacon, which is

said to have been the first lighthouse built on that part of the

coast.

In ancient times, fires were also lighted for the guidance of

seamen, at Foulness, near Cromer, at Lowestoft-ness, and at

Orford-ness—all Norse names. A long spit of land lies between

the river Alde and the long sea near Orford—extending from near

Aldborough to Haversgate Island—which was always a source of danger

to mariners. A lantern used to be hung out at a part of the

narrow strip of land, still called the Lantern Marshes, where two

splendid lighthouses have since been erected.

The first idea of a lighthouse, said Professor Faraday, is

the candle in the cottage window, guiding the husband across the

water or the pathless moor. But on Orfordness a lantern

answered the same purpose. The main point was the production

of a steady light; and it mattered not whether it was given forth by

a candle, a lantern, pitch-pots, coals, or oil. Wood was also

frequently employed; but it was found too perishable. Lambarde

says of the lights shown along the coast, that "before the time of

Edward III. they were made of great stacks of wood; but about the

eleventh yeere of his raigne it was ordained that in our shyre

(Kent) they should be high standards with their pitch-pots." [p.38]

Many attempts were made to light up the south coast at the

most dangerous places. Some six hundred years since, when

Winchelsea—now several miles inland—was a seaport, Henry III. issued

a precept commanding that every ship laden with merchandise going to

that port for the two following years, should pay two pence for the

maintenance of the light there, for the safety of sailors entering

by night, unless it were shown that the Barons had been accustomed

to maintain that light at their own cost. [p.39]

It appears that the Barons were in certain cases required to

maintain the fire-lights, and to receive the sum of two pence from

each vessel, usually called "fire-pence."

One of the most dangerous parts of the south coast was

Dungeness, consisting of a long low bank of shingle, running far out

into the sea, and not easily discernible at night. It is not

known when the first light was shown on this part of the coast; but

Lambarde makes mention of its being lit up by beacons in the time of

Edward III. Speaking of Dungeness, Lambarde says, "Before this

neshe lieth a flat into the sea, threatening great danger to

sailors. In the reign of Edward III. it was first ordered that

beacons in this country should have their pitch-pots, and that they

should no longer be made of wood-stacks or piles, as they be yet in

Wiltshire and elsewhere." It has been observed, upon this

passage, that the statement of Lambarde must imply that either a

beacon was now first erected on the Ness Point, or that there had

previously been one composed of wood, for which a pitch-pot was now

introduced, as being considered preferable. [p.40]

While these beacons were used to light up the coast for the

benefit of mariners, they were also used for the purpose of alarming

the nation when a foreign invasion was expected. When Richard

II. succeeded Edward III. in 1377, fire-beacons were ordered to be

established along the south coast, the keepers of which were

enjoined to set them on fire so soon as they saw the enemy's vessels

approach. England was at that time without a fleet, and

notwithstanding that the hill of St. Catherine's in the Isle of

Wight was furnished with a chantry and a lighthouse, where a priest

was maintained to say mass and keep the light burning, the French,

nevertheless, landed and carried away a great deal of spoil, as they

afterwards did at Winchelsea, Plymouth, Dartmouth, and elsewhere.

Pitch-pots were not found to serve for coast-lights. In

heavy storms, when lights were of the greatest value, the pitch-pots

would either be blown out or drowned out, and then all would be

darkness again. Coal was next introduced. It was set

fire to, on an open chauffer, and fed from time to time by the

lighthouse keepers. Wood continued to be used where coal was

not available. Thus the Tour de Cordouan, off the

south-western coast of France, long continued to be lit up by oak

billets brought from the Gascon forests. But the English coast

was mostly lit up by coal. In fact it is not so long since

coal became disused. It was only in 1822 that the last coal

fire, at Saint Bees, was extinguished. The last man who

attended the coal beacon at Harwich—where the fuel was burnt in an

open grate, with a pair of bellows attached—was alive only a few

years ago. [p.41] The

lighthouses at Spurn Point, and on the Isle of May at the entrance

to the Firth of Forth, also continued, until a recent period, to be

lit up by coal-chauffers. The light, also, which these coal

fires gave was very uncertain. When stirred, they emitted a

bright blaze, and then sunk into almost utter darkness until again

roused by the attendants.

A long time elapsed before anything practical was done to

light up the coasts at night. The Trinity House was indeed

established by Henry VIII. in 1515; but it was at first more of a

monastic institution than a lighthouse association. It was

denominated "The Brotherhood of the Most Glorious and Undividable

Trinity." The brethren prayed for the mariners at sea, but

they did not erect lighthouses. Their duties were enlarged by

subsequent sovereigns. They had to appoint pilots for the

Thames, collect dues for ballast, and erect lights and signals.

They attended rather to the navigation of the Thames, than to the

lighting of ships along the coast. The only step they took for

the purpose of lighting up the coast, was the granting of leases

from the Crown, for a definite number of years, to private persons

willing to find the means of building and maintaining lights, in

consideration of which, authority was given them to levy tolls on

passing shipping.

The erection of lights became a matter of speculation as well

as of political jobbing. A speculative man would propose to

erect a lighthouse just as he might propose to sink a coal-mine.

If there was a dangerous rock at sea, in front of a seaport, any man

might propose to the Trinity House to erect a building there for the

purpose of guiding ships, in which case he was allowed to levy dues

on the ships that passed. Or, if he had political influence,

he might use it for the purpose of obtaining a lighthouse.

Thus a memorandum was found in the diary of Lord Grenville, to watch

the king into a good humour, that he might "ask him for a

lighthouse."

There was a combination of philanthropy with speculativeness,

in erecting a lighthouse. The object was to save human life,

though its net result was that it should pay its constructor a large

profit. When a lighthouse was erected on the Smalls Rock in

the Bristol Channel, it was through the instrumentality of Mr.

Phillips of Liverpool, a member of the Society of Friends. His

object was to erect, at his sole risk and expense, a work that

should be "a great holy good to serve and save humanity." The

lighthouse was erected at considerable risk, and it was a

strange-looking barracoon when finished. It doubtless saved

the lives of many seamen; but it also served the purposes of its

erector, who derived a large income from it during his lifetime;

and, after his death, his representatives obtained from the Trinity

House not less than £170,000 by way of compensation for handing it

over to the Corporation.

There was another dangerous rock in the way of the shipping

bound for Liverpool—the Skerries Islands, north-east of Holyhead.

A privilege was granted to a private speculator to erect a

lighthouse there; and the dues received by the owner were so large

that the Trinity Board were compelled to give him £450,000 for the

rock and lighthouse, when they took it into their own hands! A

wooden lighthouse was also erected in 1698 on the Eddystone Rock as

a matter of speculation; but that was soon swept away by the sea. [p.43-1]

The coasts of Cornwall and Devon were also lit up about the same

period; for we are informed, in the Travels of the Grand Duke Cosmo

in England about two centuries ago, that the Plymouth shipping "paid

fourpence per ton for the lights which were in the lighthouses at

night." [p.43-2]

We also find from the records of the Corporation of Rye, that

a light was hung out from the south-east angle of the castellated

building in that town, called the Ypres Tower, as a guide for

vessels entering the harbour in the night-time, and that not being

found sufficient, another light was ordered by the Corporation "to

be hung out o' nights on the south-west corner of the church, for a

guide to vessels entering the port." A beacon to rouse the

inhabitants in case of invasion was also kindled in the old oak-tree

still remaining in the neighbouring churchyard at Playden. A

light-pot used to be hung out from the spire of old Arundel Church

for the purpose of guiding vessels entering the harbour of

Littlehampton after dark, and the iron support of the rude apparatus

is still to be seen there. [p.44]

That lights were used for the guidance of ships may also be

learnt from the practice which then prevailed among the wreckers

along the Cornish coast of displaying false lights, and thus luring

passing vessels to their destruction; the shipwreck season being

long regarded as the harvest season in Cornwall. With the

increase of navigation, the erection of lighthouses at the more

dangerous parts of the coast became a matter of urgent necessity;

and it was such necessity, as we shall afterwards find, which

brought to light the genius of Smeaton.

Until the erection of the Eddystone Lighthouse by that

engineer, the only stone lighthouse in Europe was the fine Tour de

Cordouan, built on a flat rock off the mouth of the Garonne in the

Bay of Biscay. It was finished and lit up more than two

hundred and fifty years ago; and, though one of the earliest, it

continues one of the most splendid structures of the kind in

existence. It replaced a lighthouse founded by the English on

the rock in 1362-71, while the Black Prince was Governor of Guienne.

|

Cordouan lighthouse: designed by Louis de Foix and completed in

1611.

Picture: Wikimedia Commons.

|

The present stone building was begun by Louis de Foix, one of

the architects of the Escurial, in 1584, in the time of Henry III.,

and was continued all through the reign of Henry IV., being finally

completed in 1611, in the reign of Louis XIII. Its height

originally was 169 feet French; but in 1727 it was raised to the

height of 175 feet French, or 1861 feet English. The building

exhibits that taste for magnificence in construction which attained

its meridian in France under Louis XIV. The tower does not

receive the shock of the waves, but is protected at the base by a

wall of circumvallation, which encloses the apartments for the

attendants. It is not conical like the Eddystone, but is

constructed in three successive stages, angular in the interior, and

consequently more susceptible of decoration than the simple and

solid structures of Smeaton, Rennie, and Stevenson.

The Tour de Cordouan is further memorable as the first

lighthouse in which a revolving light was ever exhibited.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

OLD BRIDGES.

IN a country such

as Britain, full of running streams, bridges form an essential part

of every system of roads connecting the various districts of the

kingdom with each other. So long as the population was scanty

and the intercourse between different parts of the country was of a

limited character, the necessity for bridges, by which the

continuity of the tracks was preserved, was probably little felt.

The shallow and broad parts of rivers, provided with a gravelly

bottom, were naturally selected as the places for fords, which could

be easily waded by men or horses when the water was low; and even in

the worst case, when the waters were out, they could be crossed by

swimming.

Towns and villages sprang up at these fordable places, along

the main lines of communication, the names of many of which survive

to this day and indicate their origin. Thus, along the line of

road between London and Dover, there was first Deep Ford, now

Deptford, at the crossing of the Ravensbourne—next Crayford on the

river Cray—Dartford on the Darent—and Aylesford on the Medway, part

of the pilgrim's road between the west of England and Becket's

shrine at Canterbury. In all other directions round London it

was the same. Thus, eastward, there was Stratford [p.48-1]

on the Lea, Romford on the Bourne, and Chelmsford on the Chelmer.

Westward were Brentford and Twyford on the Brent, Watford on the

Colne, and Oxenford or Oxford on the Isis. [p.48-2]

And along the line of the Great North Road, crossing as it did the

large streams descending from the high lands of the centre of

England towards the North Sea, the fords were very numerous. At

Hertford the Maran was crossed, at Bedford the Ouse, at Stamford the

Welland, and so on through the northern counties of England.

|

|

As population and travelling increased, the expedient of the

Bridge was adopted, to enable rivers of moderate width to be crossed

dryshod. An uprooted tree thrown across a narrow stream was

probably the first bridge; and he would probably be considered an

ingenious man who laid down a couple of trees, fixed upon them a

cross-planking, and thus enabled foot-passengers and pack-horses to

cross from one bank to the other. But these loose timber

structures were very apt to be swept away by the rains of autumn,

and the continuous track would again become completely broken.

In a rough district, where rocky streams with rugged banks had to be

crossed, such interruptions must necessarily have led to

considerable inconvenience, and hence arose the idea of tying the

rocky gorges together by means of stone bridges of a solid and

permanent character.

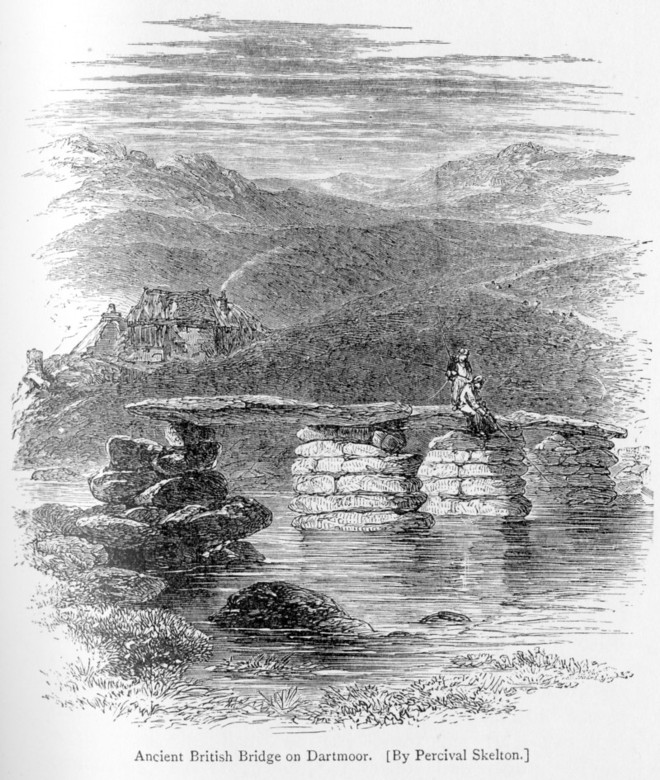

The first of such bridges in Britain were probably those

erected across the streams of Dartmoor. The rivers of that

district are rapid and turbulent in winter, and come sweeping down

from the hills with great fury. The deep gorges worn by them

in the rocks amidst which they run, prevented their being forded in

the usual way; and the ordinary expedient of bridging the gaps in

the track by means of felled trees thrown across, was found

impracticable in a district where no trees grew. But there was

an abundance of granite blocks, which not only afforded the means of

forming solid piers, but were also of sufficient size to be laid in

a tabular form from one pier to another, so as to constitute a solid

enough road for horsemen and foot-passengers. Hence the

Egyptian-looking Cyclopean bridges of Dartmoor; a series of

structures—most probably coeval with the building of Stonehenge—of

the greatest possible interest.

|

A "clapper bridge"; this at Postbridge, Dartmoor [p.49].

Photo: Editor.

|

One of the largest of these bridges is that crossing the East

Dart, near Post Bridge, on the road between Moreton and Tavistock,

of which a representation is given on the preceding page.

Though the structure is rude, it is yet of a most durable character,

otherwise it could not have withstood the fury of the Dart for full

twenty centuries, as it most probably has done. The bridge is

of three piers, each consisting of six layers of granite-slabs above

the foundation. One of the side piers, by accident or design,

has unfortunately been displaced, and the tabular slabs originally

placed upon it now lie in the bottom of the river. Each of the

table stones is about fifteen feet long and six feet wide, the whole

structure being held together merely by the weight of the blocks.

There are other more perfect specimens of these Cyclopean

bridges in existence on Dartmoor, but none of a size equal to that

above delineated. For instance, there is one of three

openings, in a very complete state, in the neighbourhood of

Sittaford Tor, spanning the North Teign: it is twenty-seven feet

long, with a roadway seven feet wide, and, like the others, is

entirely formed of granite blocks. There is another over the

Cowsic, near Two Bridges, presenting five openings: this bridge is

thirty-seven feet long and four feet broad, but it is only about

three feet and a half above the surface; nevertheless it has firmly

withstood the moorland torrents of centuries. There is a

fourth on the Blackabrook, consisting of a single stone or clam.

We believe that no structures resembling these bridges have been

found in any other part of Britain, or even in Brittany, so

celebrated for its aboriginal remains. The only bridges at all

approaching them in character are found in Ancient Egypt,—to which,

indeed, they bear a striking resemblance.

Although the Romans were great bridge-builders, it is not

certain that they erected any arched stone bridges [p.52]

during their occupation in England, though it is probable that they

built numerous timber bridges upon stone piers. The most

important were those of Rochester, Newcastle, and London. Not

many years since, when a railway-bridge was being built across the

Medway at Rochester, the workmen came upon the foundations of the

ancient work in a place where no such foundations were looked for,

and their solidity caused considerable interruption to the work.

So at Newcastle, when the old bridge over the Tyne was taken down in

1771, the foundations of the piers, which were laid on piles of fine

black oak, in a perfect state of preservation, were found to be of

Roman masonry. Similar bridges were erected at different

points along the lines of the Roman military roads wherever a river

had to be crossed; and it is probable that the town of Pontefract (Pons

fractus) derived its name from a broken Roman bridge in that

neighbourhood, the remains of which were visible in the time of

Leland.

It is not known when the English people began to build stone

bridges, after the Roman bridges had become destroyed. The

history of England was a blank for several hundred years after the

Romans left. We know next to nothing of the people who

occupied the country; we can only guess at the successive migrations

of the foreigners who settled in it. The probability is, that

at first they were, for the most part, barbarians, who neither built

bridges nor repaired the roads which the Romans had left behind

them. Civilisation recommenced with the Church. The

early Churchmen were not only the first people who could read and

write English, but they were the principal agriculturists,

gardeners, and masons. They were the first church-builders, as

they were also, probably, the first bridge-builders.

Thus, we hear of St. Swithin, Bishop of Winchester, building

a bridge over the Itchin at that city in the ninth century. He

planned the bridge, and caused it to be built at his own expense.

As St. Swithin "had necessarily to go abroad upon spiritual matters,

as ever, so in this instance, he cared for the common advantage of

the citizens, and built a bridge of stone arches at the east gate of

the city, a work which will not easily decay." [p.54]

Bridges were also constructed, most probably through the

influence of the Churchmen, at Lincoln, Durham, and other

ecclesiastical cities. These early bridges were useful, but

not graceful. They resembled a long, low series of culverts,

hardly deserving the name of arches, with intervening piers of

greater thickness than the span of the arch they were built to

support. They were a sort of stone embankments perforated by a

multitude of small openings to let the water through. The

piers had thus very little more to support than their own weight.

Quantity was substituted for quality, and mass for elegance.

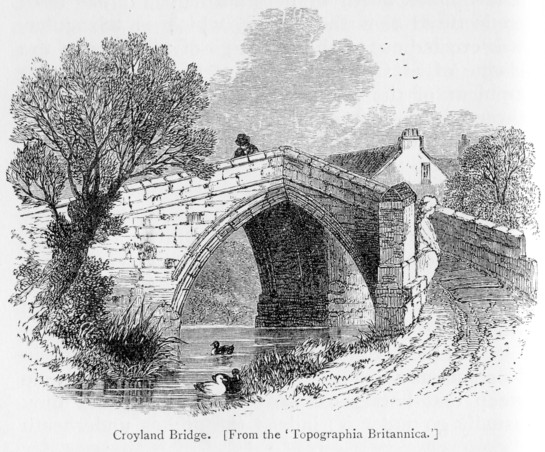

An early bridge, which some allege to be the earliest arched

stone bridge existing in England, is the singular-looking structure

still standing in the immediate neighbourhood of Croyland Abbey, a

few miles north of Peterborough. It has been conjectured that

the bridge, which is triangular, was erected out of the offerings of

pilgrims to the shrine of St. Guthlac, the saint of the Fens, as an

emblem of the Trinity. [p.55]

The bridge stands on three piers, from each of which springs the

segment of a circular arch, all the segments meeting at a point in

the centre. It is situated at the junction of the three

principal streets of the little town, which was originally built on

piles; and along those streets the waters of the Nene, the Welland,

and the Catwater respectively, used to flow and meet under the

bridge. Carrying out the Trinitarian illustration, each pier

of the bridge was said to stand in a different county: one in

Lincoln, the second in Cambridge, and the third in Northampton.

The road over the bridge is so steep that horses can scarcely cross

it, and they usually go under it; indeed the arches underneath are

now quite dry. This curious structure is referred to in an

ancient charter of the year 943, although the precise date of its

erection is unknown. On the south-west wing, facing the London

road, is a sitting figure, carved in stone, very much battered about

the face by the mischievous boys of the place. The figure has

a globe or orb in its hand. It is supposed to be a statue of

King Ethelbald, though it is commonly spoken of in the village as

Oliver Cromwell holding a penny loaf!

|

Trinity Bridge, Crowland. [p.57]

Picture Wikipedia.

|

The first ordinary road-bridge of which we have any authentic

account is that erected at Stratford over the river Lea, several

miles to the east of London. The road into Essex by the Old