|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER VII.

I BREAKFASTED in the travellers' room with three

gentlemen from Edinburgh; and then, accompanied by a boy, whom I had

engaged to carry my bag, set out to explore. The morning was

ominously hot and breathless; and while the sea lay moveless in the calm,

as a floor of polished marble, mountain, and rock, and distant island,

seemed tremulous all over, through a wavy medium of thick rising vapour.

I judged from the first that my course of exploration for the day was

destined to terminate abruptly; and as my arrangements with Mr Swanson

left me, for this part of the country, no second day to calculate upon, I

hurried over deposits which in other circumstances I would have examined

more carefully,—content with a glance. Accustomed in most instances

to take long aims, as Cuddy Headrig did, when he steadied his musket on a

rest behind the hedge, and sent his ball through Laird Oliphant's

forehead, I had on this occasion to shoot flying; and so, selecting a

large object for a mark, that I might run the less risk of missing, I

strove to acquaint myself rather with the general structure of the

district than with the organisms of its various fossiliferous beds.

The long narrow island of Rasay lies parallel to the coast of

Skye, like a vessel laid along a wharf, but drawn out from it, as if to

suffer another vessel of the same size to take her berth between; and on

the eastern shores of both Skye and Rasay we find the same Oolitic

deposits tilted up at nearly the same angle. The section presented

on the eastern coast of the one is nearly a duplicate of the section

presented on the eastern coast of the other. During one of the

severer frosts of last winter I passed along a shallow pond, studded along

the sides with boulder stones. It had been frozen over; and then,

from the evaporation so common in protracted frosts, the water had shrunk,

and the sheet of ice which had sunk down over the central portion of the

pond exhibited what a geologist would term very considerable marks of

disturbance among the boulders at the edges. Over one sharp-backed

boulder there lay a sheet tilted up like the lid of a chest half-raised;

and over another boulder immediately behind it there lay another up-tilted

sheet, like the lid of a second half-open chest; and in both sheets, the

edges, lying in nearly parallel lines, presented a range of miniature

cliff's to the shore. Now, in the two up-tilted ice-sheets of this

pond I recognised a model of the fundamental Oolitic deposits Rasay and

Skye. The mainland of Scotland had its representative in the crisp

snow-covered shore of the pond, with its belt of faded sedges; the place

of Rasay was indicated by the inner, that of Skye by the outer boulder;

while the ice-sheets, with their shoreward-turned line of cliffs,

represented the Oolitic beds, that turn to the mainland their dizzy range

of precipices, varying from six to eight hundred feet in height, and then,

sloping outwards and downwards, disappear under mountain wildernesses of

overlying trap. And it was along a portion of the range of cliff

that forms the outermost of the two up-tilted lines, and which presents in

this district of Skye a frontage of nearly twenty continuous miles to the

long Sound of Rasay, that my to-day's course of exploration lay.

From the top of the cliff the surface slopes downwards for about two miles

into the interior, like the half-raised chest-lid of my illustration

sloping towards the hinges, or the up-tilted icetable of the boulder

sloping towards the centre of the pond; and the depression behind forms a

flat moory valley, full fifteen miles in length, occupied by a chain of

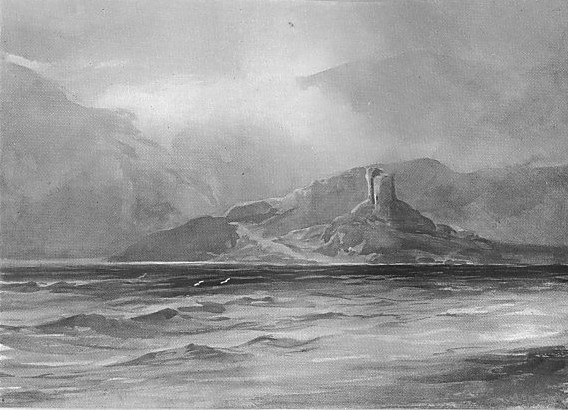

dark bogs and treeless lochans. A long line of trap-hills rises over

it, in one of which, considerably in advance of the others, I recognised

the Storr of Skye, famous among lovers of the picturesque for its strange

group of mingled pinnacles and towers; while directly crossing into the

valley from the Sound, and then running southwards for about two miles

along its bottom, is the noble sea-arm, Loch Portree, in which, as

indicated by the name (the King's Port) a Scottish king of the olden time,

in his voyage round his dominions, cast anchor. The opening of the

loch is singularly majestic; the cliffs tower high on either side in

graceful magnificence: but from the peculiar inward slope of the land, all

within, as the loch reaches the line of the valley, becomes tame and low,

and a black dreary moor stretches from the flat terminal basin into the

interior. The opening of Loch Portree is a palace gateway, erected

in front of some homely suburb, that occupies the place which the palace

itself should have occupied.

|

|

|

The Storr of Skye. |

There was, however, no such mixture of the homely and the

magnificent in the route I had selected to explore. It lay under the

escarpment of the cliff; and I purposed pursuing it from Portree to Holm,

a distance of about six miles, and then returning by the flat interior

valley. On the one hand rose a sloping rampart, full seven hundred

feet in height, striped longitudinally with alternating bands of white

sandstone and dark shale, and capped atop by a continuous coping of trap,

that lacked not massy tower, and overhanging turret, and projecting

sentry-box; while, on the other hand, spreading outwards in the calm from

the line of dark trap-rocks below, like a mirror from its carved frame of

black oak, lay the Sound of Rasay, with its noble background of island and

main rising bold on the east, and its long mountain vista opening to the

south. The first fossiliferous deposit which gave me occasion this

morning to use my hammer occurs near the opening of the loch, beside an

old Celtic burying-ground, in the form of a thick bed of hard sandstone,

charged with Belemnites,—a bed that must at one time have existed as a

widely-spread accumulation of sand,—the bottom, mayhap, of some extensive

bay of the Oolite, resembling the Loch Portree of the present day, in

which eddy tides deposited the sand swept along by the tidal currents of

some neighbouring sound, and which swarmed as thickly with Cephalopoda as

the loch swarmed this day with minute purple-tinged Medusæ.

I found detached on the shore, immediately below this bed, a piece of

calcareous fissile sandstone, abounding in small sulcated Terebratulæ,

identical, apparently, with the Terebratula of a specimen in my collection

from the inferior Oolite of Yorkshire. A colony of this delicate

Brachiopod must have once lain moored near this spot, like a fleet of

long- prowed galleys at anchor, each one with its cable of many strands

extended earthwards from the single dead-eye in its umbone. For a

full mile after rounding the northern boundary of the loch, we find the

immense escarpment composed from top to bottom exclusively of trap; but

then the Oolite again begins to appear, and about two miles further on the

section becomes truly magnificent,—one of the finest sections of this

formation exhibited anywhere in Britain, perhaps in the world. In a ravine

furrowed in the face of the declivity by the headlong descent of a small

stream, we may trace all the beds of the system in succession, from the Cornbrash, an upper deposit of the Lower Oolite, down to the Lias, the for

mation on which the Oolite rests. The only modifying circumstance to the

geologist is, that though the sandstone beds run continuously along the

cliff for miles together, distinct as the white bands in a piece of onyx,

the intervening beds of shale are swarded over, save where we here and

there see them laid bare in some abrupter acclivity or deeper watercourse.

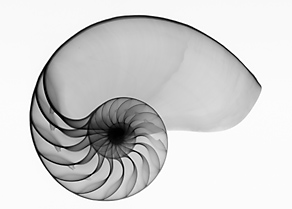

In the shale we find numerous minute Ammonites, sorely weathered; in the

sandstone, Belemnites, some of them of great size; and dark carbonaceous

markings, passing not unfrequently into a glossy cubical coal. At the foot

of the cliff I picked up an ammonite of considerable size and well-marked

character,—the Ammonites Murchisonœ, first discovered on this

coast by Sir R. Murchison about fifteen years ago. It measures, when

full grown, from six to seven inches in diameter: the inner whorls, which

are broadly visible, are ribbed; whereas the two, and sometimes the three

outer ones, are smooth,—a marked characteristic of the species. My

specimen merely enabled me to examine the peculiarities of the shell just

a little more minutely than I could have done in the pages of Sowerby; for

such was its state of decay, that it fell to pieces in my hands. I

had now come full in view of the rocky island of Holm, when the altered

appearance of the heavens led me to deliberate, just as I was warming in

the work of exploration, whether, after all, it might not be well to scale

the cliffs, and strike directly on the inn. It was nearly three

o'clock; the sky had been gradually darkening since noon, as if one thin

covering of gauze after another had been drawn over it; hill and island

had first dimmed and then disappeared in the landscape; and now the sun

stood up right over the fast-contracting vista of the Sound, round and

lightless as the moon in a haze; and the downward cataract-like streaming

of the gray vapour on the horizon showed that there the rain had already

broken, and was descending in torrents. We had been thirsty in the

hot sun, and had found the springs few and scanty; but the boy now assured

me, in very broken English, that we were to get a great deal more water

than would be good for us, and that it might be advisable to get out of

its way. And so, climbing to the top of the cliffs, along a

water-course, we reached the ridge, just as the fog came rolling downwards

from the peaked brow of the Storr into the flat moory pea valley, and the

melancholy lochans roughened and darkened in the rain. We were both

particularly wet ere we reached Portree.

|

|

|

Sir Roderick Murchison, Scottish geologist.

(1792-1871) |

In exploring our Scotch formations, I have had frequent

occasion, in Ross, Sutherland, Caithness, and now once more in Skye, to

pass over ground described by Sir R. Murchison; and in every instance

have I found myself immensely his

debtor. His descriptions possess the merit of being true: they are simple

outlines often, that leave much to be filled up by after discovery; but,

like those outlines of the skilful geographer that fix the place of some

island or strait, though they may not entirely define it, they always

indicate the exact position in the scale of the formations to which they

refer. They leave a good deal to be done in the way of mapping out the

interior of a deposit, if I may so speak; but they leave

nothing to be done in the way of ascertaining its place. The work

accomplished is bona fide work,—actual, solid, not to be done over again,—work

such as could be achieved in only

the school of Dr William Smith, the father of English Geology. I have

found much to admire, too, in the sections of

Sir R. Murchison. His section of this part of the coast, for example,

strikes from the extreme northern part of Skye to the island of Holm,

thence to Scrapidale in Rasay, thence along part of the coast of Scalpa,

thence direct through the middle of Pabba, and thence to the shore of the

Bay of Laing. The line thus taken includes, in regular sequence in the

descending order, the whole Oolitic deposits of the Hebrides, from the Cornbrash, with its overlying freshwater outliers of mayhap the Weald,

down to where the Lower Lias rests on

the primary red sandstones of Sleat. It would have cost M'Culloch less

exploration to have written a volume than it must have cost Sir R.

Murchison to draw this single line;

but the line once drawn, is work done to the hands of all after explorers.

I have followed repeatedly in the track of another geologist, of, however,

a very different school, who explored, at a comparatively recent period,

the deposits of not

a few of our Scotch counties. But his labours, in at least the

fossiliferous formations, seem to have accomplished nothing for

Geology,—I am afraid, even less than nothing. So far as they had

influence at all, it must have been to throw back the science. A geologist

who could have asserted only three years ago ("Geognostical Account of

Banffshire," 1842), that the Old Red Sandstone of Scotland forms merely "a part of the great coal deposit," could have known marvellously little of

the fossils of the one system, and nothing whatever of those of the other. Had he examined ere he decided, instead of deciding without any intention

of examining, he would have found that, while both systems abound in

organic remains, they do not possess, in Scotland at least, a single

species in common, and that even their types of being, viewed in the

group, are essentially distinct.

The three Edinburgh gentlemen whom I had met at breakfast were still in

the inn. One of them I had seen before, as one of the guests at a Wesleyan

soiree, though I saw he failed to remember that I had been there as a

guest too. The

two other gentlemen were altogether strangers to me. One of them,—a man

on the right side of forty, and a superb specimen of the powerful,

six-feet-two-inch Norman Celt,—I set down as a scion of some old Highland

family, who, as the broadsword had gone out, carried on the internal wars

of the country with the formidable artillery of Statute and Decision. The

other, a gentleman more advanced in life, I predicated to be a Highland

proprietor, the uncle of the younger of the two,—a man whose name, as he

had an air of business about him, occurred, in all probability, in the

Almanac, in the list of Scotch advocates. Both were of course high

Tories,—I was quite sure of that,—zealous in behalf of the Establishment,

though previous to the Disruption they had not cared for it a pin's

point,—and prepared to justify the virtual suppression of the toleration

laws in the case of the Free Church. I was thus decidedly guilty of

what old Dr More calls a pro-sopolepsia,—i.e. of the crime of judging men by

their looks. At dinner, however, we gradually ate ourselves into

conversation: we differed, and disputed, and agreed, and then differed, disputed, and agreed again. I found first, that my chance

companions were really not very high Tories; and then, that they were not

Tories at all; and then, that the younger of the two was very much a

Whig, and the more advanced in life,—strange as the fact might

seem,—very considerably a Presbyterian Whig; and finally, that this

latter gentleman, whom I had set down as an intolerant Highland

proprietor, was a respected writer to the signet, a Free Church elder in

Edinburgh; and that the other, his equally intolerant nephew, was an

Edinburgh advocate, of vigorous talent, much an enemy of all oppression,

and a brother contributor of my

own to one of the Quarterlies. Of all my surmisings regarding the stranger

gentlemen, only two points held true,—they were both gentlemen of the

law, and both had Celtic blood

in their veins. The evening passed pleasantly; and I can now recommend

from experience, to the hapless traveller who gets thoroughly wet thirty

miles from a change of dress, that some of the best things he can resort

to in the circumstances are, a warm room, a warm glass, and agreeable

companions.

On the morrow I behoved to return to isle Ornsay, to set out on the

following day, with my friend the minister, for Rum, where he purposed

preaching on the Sabbath. To have lost a day would have been to lose the

opportunity of exploring the island, perhaps for ever; and, to make all

sure, I had taken a seat in the mail gig, from the postman who drives it,

ere going to bed, on the morning of my arrival; and now,

when it drove up, I went to take my place in it. The post-master of the

village, a lean, hungry-looking man, interfered to prevent me. I had

secured my seat, I said, two days previous. Ah, but I had not secured it

from him. "I know nothing of you, I replied; but I secured it from one

who deemed himself authorized to receive the fare; was he so?"

"Yes." "Could you have received it?" "No." "Show

me a copy of your regulations." "I have no copy of regulations; but I

have given the place in the gig to another." "Just so; and what say you,

postman?" "That you took the place from me, and that he has no right to

give a place to any one: I carry the Portree letters to him, but he has

nothing to do with the passengers." A person present, the proprietor or stabler of the horse, I believe, also interfered on the same side; but

what Carlyle terms the "gigmanity" of the postmaster was all at

stake,—his whole influence in the mail-gig of Portree; and so he argued,

and threatened withal, and, what was the more serious part of the

business, the person he had given the seat to had taken possession of the

gig; and so we had to compound the matter by carrying

a passenger additional. The incident is scarce worth relating; but the

postmaster was so vehement and terrible, so defiant of us all,—post, stabler, and simple passenger,—and so justly impressed with the

importance of being postmaster of Portree, that, as I am in the way of

describing rare specimens at any rate, I must refer to him among the rest,

as if he had been one of the minor carnivore of a Skye deposit,—a

cuttlefish, that preyed on the weaker molluscs, or a hungry polypus,

terrible among the animalculæ.

We drove heavily, and had to dismount and walk afoot over every steeper

acclivity; but I carried my hammer, and only grieved that in some one or

two localities the road should have been so level. I regretted it in

especial on the southern and eastern side of Loch Sligachan, where I could

see

from my seat, as we drove past, the dark blue rocks in the water-courses

on each side the road, studded over with that characteristic shell of the

Lias, the Gryphœa incurva, and that the dry-stone fences in the moor

above exhibit fossils that might figure in a museum. But we rattled by. At Broadford, twenty-five miles from Portree, and nine miles from isle Ornsay,

I partook of a hospitable meal in the house of an acquaintance; and in

little more than two hours after

was with my friend the minister at isle Ornsay. The night

wore pleasantly by. Mrs Swanson, a niece of the late Dr Smith of Campbelton, so well known for his Celtic researches and his exquisite

translations of ancient Celtic poetry, I found

deeply versed in the legendary lore of the Highlands. The minister showed

me a fine specimen of Pterichthys which I had disinterred for him, out of

my first discovered fossiliferous deposit of the Old Red Sandstone,

exactly thirteen years before, and full seven years ere I had introduced

the creature

to the notice of Agassiz. And the minister's daughter, a little chubby

girl of three summers, taking part in the general entertainment, strove to

make her Gaelic sound as like

English as she could, in my especial behalf. I remembered, as I listened

to the unintelligible prattle of the little thing, unprovided with a word

of English, that just eighteen years before, her father had had no Gaelic,

and wondered what he would have thought, could he have been told, when he

first sat down to study it, the story of his island charge in Eigg, and

his Free Church yacht the Betsey. Nineteen years before, we had been

engaged in beating over the Eathie Lias together, collecting Belemnites,

Ammonites, and fossil wood, and striving in friendly emulation the one to

surpass the other in the variety and excellence of our specimens. Our

leisure hours were snatched, at the time, from college studies by the one,

from the mallet by the other: there were

few of them that we did not spend together, and that we

were not mutually the better for so spending. I at least owe much to these

hours,—among other things, views of theologic truth, that determined the

side I have taken in our ecclesiastical controversy. Our courses at an

after period lay diverse; the young minister had greatly more important

business to pursue than any which the geologic field furnishes; and so our

amicable rivalry ceased early. In the words in which an English poet

addresses his brother,—the clergyman who sat for the picture in the "Deserted Village,"—my friend "entered on a sacred office, where the

harvest is great and the labourers are few, and left to me a field in

which the labourers are many, and the harvest scarce worth carrying away."

Next day at noon we weighed anchor, and stood out for Rum, a run of about

twenty-five miles. A kind friend had, we found, sent aboard in our behalf

two pieces of rare antiquity,—rare anywhere, but especially rare in the

lockers of the Betsey,—in the agreeable form of two bottles of semifossil

Madeira,—Madeira that had actually existed in the grape exactly half a

century before, at the time when Robespierre was startling Paris from its

propriety, by mutilating at the neck the busts of other people, and

multiplying casts and medals of his own; and we found it, explored in

moderation, no bad study for geologists, especially in coarse weather,

when they had got wet and somewhat fatigued. It was like Landlord

Boniface's ale, mild as milk, had exchanged its distinctive flavour as

Madeira for a better one, and filled the cabin with fragrance every time

the cork was drawn. Old observant Homer must have smelt some such liquor

somewhere, or he could never have described so well the still more ancient

and venerable wine with which wily Ulysses beguiled one-eyed Polypheme:—

|

Unmingled wine,

Mellifluous, undecaying, and divine,

Which now, some ages from his race concealed,

The hoary sire in gratitude revealed. * * *

Scarce twenty measures from the living stream

To cool one cup sufficed: the goblet crowned,

Breathed aromatic fragrances around.

|

Winds were light and variable. As we reached the middle of the sound

opposite Armadale, there fell a dead calm; and the Betsey, more actively

idle than the ship manned by the Ancient Mariner, dropped sternwards along

the tide, to

the dull music of the flapping sail. The minister spent the day in the

cabin, engaged with his discourse for the morrow; and I, that he might

suffer as little from interruption as possible, mis-spent it upon the deck. I tried fishing with the yacht's set

of lines, but there were no fish to bite,—got into the boat, but there

were no neighbouring islands to visit,—and sent half a dozen

pistol-bullets after a shoal of porpoises, which, coming from the Free

Church yacht, must have astonished the fat sleek fellows pretty

considerably, but did them,

I am afraid, no serious damage. As the evening began to close gloomy and gray, a tumbling swell came heaving in right ahead from the west; and a

bank of cloud, which had been gradually rising higher and darker over the

horizon in the same direction, first changed its abrupt edge atop for a

diffused and broken line, and then spread itself over the central

heavens. The calm was evidently not to be a calm long; and the minister

issued orders that the gaff-topsail should be taken down, and the storm

jib bent; and that we should lower our topmast, and have all tight and

ready for a smart

gale a-head. At half-past ten, however, the Betsey was still pitching to

the swell, with not a breath of wind to act on the diminished canvass, and

with but the solitary circumstance in her favour, that the tide ran no

longer against her, as before. The cabin was full of all manner of creakings; the close lamp swung to and fro over the head of my friend;

and a refractory Concordance, after having twice travelled

from him along the entire length of the table, flung itself pettishly upon

the floor. I got into my snug bed about eleven; and at twelve, the

minister, after poring sufficiently over his notes, and drawing the final

score, turned into his. In a brief hour after, on came the gale, in a

style worthy of its previous hours of preparation; and my friend,—his

Saturday's work in his ministerial capacity well over when he had

completed his two discourses,—had to begin the Sabbath morning early as

the morning itself began, by taking his stand

at the helm, in his capacity of skipper of the Betsey. With the prospect

of the services of the Sabbath before him, and after working all Saturday

to boot, it was rather hard to set him down to a midnight spell at the

helm, but he could not be wanted at such a time, as we had no other such

helmsman aboard. The gale, thickened with rain, came down, shrieking like

a maniac, from off the peaked hills of Rum, striking away the tops of the

long ridgy billows that had risen in the calm to indicate its approach,

and then carrying them in sheets of spray aslant the furrowed surface,

like snow-drift hurried across a frozen field. But the Betsey, with her

storm-jib set, and her mainsail reefed to the cross, kept her weather bow

bravely to the blast, and gained on it with every tack. She had been the

pleasure yacht, in her day, of a man of fortune, who had used, in running

south with her at times as far as Lisbon, to encounter, on not worse terms

than the stateliest of her neighbours in the voyage, the swell of the Bay

of Biscay; and she still kept true to her old character, with but this

drawback, that she had now got somewhat crazy in her fastenings, and made

rather more water in a heavy sea

than her one little pump could conveniently keep under. As the fitful gust

struck her headlong, as if it had been some invisible missile hurled at us

from off the hill-tops, she stooped her head lower and lower, like old

stately Hardyknute under the blow of the "King of Norse," till at length

the lee chain-plate rustled sharp through the foam; but, like a staunch Free

Churchwoman, the lowlier she bent, the more steadfastly did she hold her

head to the storm. The strength of the opposition served but to speed her

on all the more surely to the

desired haven. At five o'clock in the morning we cast anchor in Loch Scresort,—the only harbour of Rum in which a vessel can moor,—within two

hundred yards of the shore, having, with the exception of the minister,

gained no loss in the gale. He, luckless man, had parted from his

excellent sou-wester; a

sudden gust had seized it by the flap, and hurried it away far to the lee.

He had yielded it to the winds, as he had done the temporalities, but much

more unwillingly, and less as a free agent. Should any conscientious

mariner pick up anywhere in the Atlantic a serviceable ochre-coloured sou-wester,

not at all the worse for the wear, I give him to wit that he holds Free

Church property, and that he is heartily welcome to hold it, leaving it to

himself to consider whether a benefaction to its full value, deducting

salvage, is not owing, in honour, to the Sustentation Fund.

It was ten o'clock ere the more fatigued aboard could muster resolution

enough to quit their beds a second time; and then it behoved the minister

to prepare for his Sabbath labours ashore. The gale still blew in fierce

gusts from the hills, and the rain pattered like small shot on the deck. Loch Scresort, by no means one of our finer island lochs, viewed under any

circumstances, looked particularly dismal this morning. It forms the

opening of a dreary moorland valley, bounded on one of its sides, to the

mouth of the loch, by a homely ridge of Old Red Sandstone, and on the

other by a line of dark augitic hills, that attain, at the distance of

about

a mile from the sea; an elevation of two thousand feet. Along the slopes

of the sandstone ridge I could discern, through the haze, numerous green

patches, that had once supported a dense population, long since "cleared

off" to the backwoods of America, but not one inhabited dwelling; while

along a black moory acclivity under the hills on the other side I could

see several groups of turf cottages, with here and there a minute speck of

raw-looking corn beside them, that, judging from its colour, seemed to

have but a slight chance of ripening. The hill-tops were lost in cloud and

storm; and ever and anon as a heavier shower came sweeping down on the

wind, the intervening hollows closed up their gloomy vistas, and all was

fog and rhime to the water's edge. Bad as the morning was, however, we

could see the people wending their way, in threes and fours, through the

dark moor, to the place of worship,—a black turf hovel, like the meeting-house in Eigg. The appearance of the Betsey in the loch had been the

gathering signal; and the Free Church islanders—three-fourths of the

entire population—had all come out to meet their minister.

On going ashore, we found the place nearly filled. My friend preached two

long energetic discourses, and then returned to the yacht, a "worn and

weary man." The studies of the previous day, and the fatigues of the

previous night, added to his pulpit duties, had so fairly prostrated his

strength, that the sternest teetotaller in the kingdom would scarce have

forbidden him a glass of our fifty-year-old Madeira. But even

the fifty-year-old Madeira proved no specific in the case. He was

suffering under excruciating headache, and had to stretch himself in his

bed, with eyes shut but sleepless, waiting till the fit should

pass,—every pulse that beat in his temples a throb of pain.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE geology of the island of Rum is simple, but

curious. Let the reader take, if he can, from twelve to fifteen

trap-hills, varying from one thousand to two thousand three hundred feet

in height; let him pack them closely and squarely together, like

rum-bottles in a case-basket; let him surround them with a frame of Old

Red Sandstone, measuring rather more than seven miles on the side, in the

way the basket surrounds the bottles; then let him set them down in the

sea a dozen miles off the land,—and he shall have produced a second island

of Rum, similar in structure to the existing one. In the actual

island, however, there is a defect in the inclosing basket of sandstone:

the basket, complete on three of its sides, wants the fourth; and the side

opposite to the gap which the fourth should have occupied is thicker than

the two other sides put together. Where I now write there is an old

dark-coloured picture on the wall before me. I take off one of the

four bars of which the frame is composed,—the end-bar,—and stick it on to

the end-bar opposite, and then the picture is fully framed on two of its

sides, and doubly framed on a third, but the fourth side lacks framing

altogether. And such is the geology of the island of Rum. We

find the one loch of the island,—that in which the Betsey lies at

anchor,—and the long withdrawing valley, of which the loch is merely a

prolongation, occurring in the double sandstone bar: it seems to mark—to

return to my illustration—the line in which the superadded piece of frame

has been stuck on to the frame proper. The origin of the island is

illustrated by its structure: it has left its story legibly written, and

we have but to run our eye over the characters and read. An extended

sea-bottom, composed of Old Red Sandstone, already tilted up by previous

convulsions, so that the strata presented their edges, tier beyond tier,

like roofing slate laid aslant on a floor, became a centre of Plutonic

activity. The molten trap broke through at various times, and

presenting various appearances, but in nearly the same centre; here

existing as an augitic rock, there as a syenite, yonder as a basalt or

amygdaloid. At one place it uptilted the sandstone; at another it

overflowed it: the dark central masses raised their heads above the

surface, higher and higher with every earthquake throe from beneath; till

at length the gigantic Ben More attained to its present altitude of two

thousand three hundred feet over the sea-level, and the sandstone, borne

up from beneath like floating sea-wrack on the back of a porpoise, reached

in long outside bands its elevation of from six to eight hundred.

And such is the piece of history, composed in silent but expressive

language, and inscribed in the old geologic character, on the rocks of

Rum.

The wind lowered and the rain ceased during the night, and

the morning of Monday was clear, bracing, and breezy. The island of

Rum is chiefly famous among mineralogists for its heliotropes or

bloodstones; and we proposed devoting the greater part of the day to an

examination of the hill of Scuir More, in which they occur, and which lies

on the opposite side of the island, about eight miles from the mooring

ground of the Betsey. Ere setting out, however, I found time enough,

by rising some two or three hours before breakfast, to explore the Red

Sandstones on the southern side of the loch. They lie in this bar of

the frame, to return once more to my old illustration,—as if it had been

cut out of a piece of cross-grained deal, in which the annular bands,

instead of ranging lengthwise, ran diagonally from side to side; stratum

leans over stratum, dipping towards the west at an angle of about thirty

degrees; and as in a continuous line of more than seven miles there seem

no breaks or repetitions in the strata, the thickness of the deposit must

be enormous,—not less, I should suppose, than from six to eight thousand

feet. Like the Lower Old Red Sandstones of Cromarty and Moray, the

red arenaceous strata occur in thick beds, separated from each other by

bands of a grayish-coloured stratified clay, on the planes of which I

could trace with great distinctness ripple markings; but in vain did I

explore their numerous folds for the plates, scales, and fucoid

impressions which abound in the gray argillaceous beds of the shores of

the Moray and Cromarty Friths. It would, however, be rash to

pronounce them non-fossiliferous, after the hasty search of a single

morning,—unpardonably so in one who had spent very many mornings in

putting to the question the gray stratified beds of Ross and Cromarty, ere

he succeeded in extorting from them the secret of their organic riches.

|

|

|

Louis Agassiz, Swiss-born geologist

(1807-73). |

We set out about half-past ten for Scuir More, through

the Red Sandstone valley in which Loch Scresort terminates, with one of Mr

Swanson's s people, a young active lad of twenty, for our guide. In

passing upwards for nearly a mile along the stream that falls into the

upper part of the loch, and lays bare the strata, we saw no change in the

character of the sand stone. Red arenaceous beds of great thickness

alternate with grayish-coloured bands, composed of a ripple-marked

micaceous slate and a stratified clay. For a depth of full three

thousand feet, and I know not how much more,—for I lacked time to trace it

further,—the deposit presents no other variety: the thick red bed of at

least a hundred yards succeeds the thin gray band of from three to six

feet, and is succeeded by a similar gray band in turn. The

ripple-marks I found as sharply relieved in some of the folds as if the

wavy undulations to which they owed their origin had passed over them

within the hour. The comparatively small size of their alternating

ridges and furrows give evidence that the waters beneath which they had

formed had been of no very profound depth. In the upper part of the

valley, which is bare, trackless, and solitary, with a high monotonous

sandstone ridge bounding it on the one side, and a line of gloomy

trap-hills rising over it on the other, the edges of the strata, where

they protrude through the mingled heath and moss, exhibit the mysterious

scratchings and polishings now so generally connected with the glacial

theory of Agassiz. The scratchings run in nearly the line of the

valley, which exhibits no trace of moraines; and they seem to have been

produced rather by the operation of those extensively developed causes,

whatever their nature, that have at once left their mark on the sides and

summits of some of our highest hills, and the rocks and boulders of some

of our most extended plains, than by the agency of forces limited to the

locality. They testify, Agassiz would perhaps say, not regarding the

existence of some local glacier that descended from the higher grounds

into the valley, but respecting the existence of the great polar glacier.

I felt, however, in this bleak and solitary hollow, with the grooved and

polished platforms at my feet, stretching away amid the heath, like flat

tombstones in a graveyard, that I had arrived at one geologic inscription

to which I still wanted the key. The vesicular structure of the

traps on the one hand, identical with that of so many of our modern

lavas,—the ripple-markings of the arenaceous beds on the other,

indistinguishable from those of the sea-banks on our coasts,—the upturned

strata and the overlying trap,—told all their several stories of fire, or

wave, or terrible convulsion, and told them simply and clearly; but here

was a story not clearly told. It summoned up doubtful, ever-shifting

visions,—now of a vast ice continent, abutting on this far isle of the

Hebrides from the role, and trampling heavily over it, now of the wild

rush of a turbid, mountain-high flood breaking in from the west, and

hurling athwart the torn surface, rocks, and stones, and clay,—now of a

dreary ocean rising high along the hills, and bearing onward with its

winds and currents, huge icebergs, that now brushed the mountain-sides,

and now grated along the bottom of the submerged valleys. The

inscription on the polished surfaces, with its careless mixture of groove

and scratch, is an inscription of very various readings.

We passed along a transverse hollow, and then began to ascend

a hill-side, from the ridge of which the water sheds to the opposite shore

of the island, and on which we catch our first glimpse of Scuir More,

standing up over the sea, like a pyramid shorn of its top. A brown

lizard, nearly five inches in length, startled by our approach, ran

hurriedly across the path; and our guide, possessed by the general

Highland belief that the creature is poisonous, and injures cattle, struck

at it with a switch, and cut it in two immediately behind the hinder legs.

The upper half, containing all that anatomists regard as the vitals,

heart, brain, and viscera, all the main nerves, and all the larger

arteries, lay stunned by the blow, as if dead; nor did it manifest any

signs of vitality so long as we remained beside it; whereas the lower

half, as if the whole life of the animal had retired into it, continued

dancing upon the moss for a full minute after, like a young eel scooped

out of some stream, and thrown upon the bank; and then lay wriggling and

palpitating for about half a minute more. There are few things more

inexplicable in the province of the naturalist than the phenomenon of what

may be termed divided life,—vitality broken into two, and yet continuing

to exist as vitality in both the dissevered pieces. We see in the

nobler animals mere glimpses of the phenomenon,—mere indications of it,

doubtfully apparent for at most a few minutes. The blood drawn from

the human arm by the lancet continues to live in the cup until it has

cooled and begun to coagulate; and when head and body have parted company

under the guillotine, both exhibit for a brief space such unequivocal

signs of life, that the question arose in France during the horrors of the

Revolution, whether there might not be some glimmering of consciousness

attendant at the same time on the fearfully opening and shutting eyes and

mouth of the one, and the beating heart and jerking neck of the other.

The lower we descend in the scale of being, the more striking the

instances which we receive of this divisibility of the vital principle.

I have seen the two halves of the heart of a ray pulsating for a full

quarter of an hour after they had been separated from the body and from

each other. The blood circulates in the hind leg of a frog for many

minutes after the removal of the heart, which meanwhile keeps up an

independent motion of its own. Vitality can be so divided in the

earthworm, that, as demonstrated by the experiments of Spalanzani, each of

the severed parts carries life enough away to set it up as an independent

animal; while the polypus, a creature of still more imperfect

organization, and with the vivacious principle more equally diffused over

it, may be multiplied by its pieces nearly as readily as a gooseberry bush

by its slips. It was sufficiently curious, however, to see, in the

case of this brown lizard, the least vital half of the creature so much

more vivacious, apparently, than the half which contained the heart and

brain. It is not improbable, however, that the presence of these

organs had only the effect of rendering the upper portion which contained

them more capable of being thrown into a state of insensibility. A

blow dealt one of the vertebrata of the head at once renders it

insensible. It is after this mode the fisherman kills the salmon

captured in his wear, and a single blow, when well directed, is always

sufficient; but no single blow has the same effect on the earthworm; and

here it was vitality in the inferior portion of the reptile,—the earthworm

portion of it, if I may so speak,—that refused to participate in the state

of syncope into which the vitality of the superior portion had been

thrown. The nice and delicate vitality of the brain seems to impart

to the whole system in connection with it an aptitude for dying

suddenly,—a susceptibility of instant death, which would be wanting

without it. The heart of the rabbit continues to beat regularly long

after the brain has been removed by careful excision, if respiration be

artificially kept up; but if, instead of amputating the head, the brain be

crushed in its place by a sudden blow of a hammer, the heart ceases its

motion at once. And such seemed to be the principle illustrated

here. But why the agonized dancing on the sward of the inferior part

of the reptile?—why its after painful writhing and wriggling? The

young eel scooped from the stream, whose motions it resembled, is

impressed by terror, and can feel pain; was it also impressed by terror,

or susceptible of suffering? We see in the case of both exactly the

same signs,—the dancing, the writhing, the wriggling; but are we to

interpret them after the same manner? In the small red-headed

earthworm divided by Spalanzani, that in three months got upper

extremities to its lower part, and lower extremities, in as many weeks, to

its upper part, the dividing blow must have dealt duplicate feelings,—pain

and terror to the portion below, and pain and terror to the portion above,

so far, at least, as a creature so low in the scale was susceptible of

these feelings; but are we to hold that the leaping, wriggling tail of the

reptile possessed in any degree a similar susceptibility? I can

propound the riddle, but who shall resolve it? It may be added, that

this brown lizard was the only recent saurian I chanced to see in the

Hebrides, and that, though large for its kind, its whole bulk did not

nearly equal that of a single vertebral joint of the fossil saurians of

Eigg. The reptile, since his deposition from the first place in the

scale of creation, has sunk sadly in those parts: the ex-monarch has

become a low plebeian.

We came down upon the coast through a swampy valley,

terminating in the interior in a frowning wall of basalt, and bounded on

the south, where it opens to the sea, by the Scuir More. The Scuir

is a precipitous mountain, that rises from twelve to fifteen hundred feet

direct over the beach. M'Culloch describes it as inaccessible, and

states that it is only among the debris at its base that its heliotropes

can be procured; but the distinguished mineralogist must have had

considerably less skill in climbing rocks than in describing them, as,

indeed, some of his descriptions, though generally very admirable,

abundantly testify. I am inclined to infer from his book, after

having passed over much of the ground which he describes, that he must

have been a man of the type so well hit off by Burns in his portrait of

Captain Grose,—round, rosy, short-legged, quick of eye but slow of foot,

quite as indifferent a climber as Bailie Nicol Jarvie, and disposed at

times, like the elderly gentleman drawn by Crabbe, to prefer the view at

the hill-foot to the prospect from its summit. I found little

difficulty in scaling the sides of Scuir More for a thousand feet

upwards,—in one part by a route rarely attempted before,—and in ensconcing

myself among the blood stones. They occur in the amygdaloidal trap

of which the upper part of the hill is mainly composed, in great numbers,

and occasionally in bulky masses; but it is rare to find other than small

specimens that would be recognised as of value by the lapidary. The

inclosing rock must have been as thickly vesicular in its original state

as the scoria of a glass-house; and all the vesicles, large and small,

like the retorts and receivers of a laboratory, have been vessels in which

some curious chemical process has been carried on. Many of them we

find filled with a white semi-translucent or opaque chalcedony; many more

with a pure green earth, which, where exposed to the bleaching influences

of the weather, exhibits a fine verdigris hue, but which in the fresh

fracture is generally of an olive green, or of a brownish or reddish

colour. I have never yet seen a rock in which this earth was so

abundant as in the amygdaloid of Scuir More. For yards together in

some places we see it projecting from the surface in round globules, that

very much resemble green pease, and that occur as thickly in the inclosing

mass as pebbles in an Old Red Sandstone conglomerate. The heliotrope

has formed among it in centres, to which the chalcedony seems to have been

drawn, as if by molecular attraction. We find a mass, varying from

the size of a walnut to that of a man's head, occupying some larger

vesicle or crevice of the amygdaloid, and all the smaller vesicles around

it, for an inch or two, filled with what we may venture to term satellite

heliotropes, some of them as minute as grains of wild mustard, and all of

them more or less earthy, generally in proportion to their distance from

the first formed heliotrope in the middle. No one can see them in

their place in the rock, with the abundant green earth all around, and the

chalcedony, in its uncoloured state, filling up so many of the larger

cavities, without acquiescing in the conclusion respecting the origin of

the gem first suggested by Werner, and afterwards adopted and illustrated

by M'Culloch. The heliotrope is merely a chalcedony, stained in the

forming with an infusion of green earth, as the coloured waters in the

apothecary's window are stained by the infusions, vegetable and mineral,

from which they derive their ornamental character. The red mottlings

which so heighten the beauty of the stone occur in comparatively few of

the specimens of Scuir More. They are minute jasperous formations,

independent of the inclosing mass; and, from their resemblance to streaks

and spots of blood, suggest the name by which the heliotrope is popularly

known. I succeeded in making up, among the crags, a set of specimens

curiously illustrative of the origin of the gem. One specimen

consists of white, uncoloured chalcedony; a second, of a rich

verdigrishued green earth; a third, of chalcedony barely tinged with

green; a fourth, of chalcedony tinged just a shade more deeply; a fifth,

tinged more deeply still; a sixth, of a deep green on one side, and scarce

at all coloured on the other; and a seventh, dark and richly toned,—a true

bloodstone,—thickly streaked and mottled with red jasper. In the

chemical process that rendered the Scuir More a mountain of gems there

were two deteriorating circumstances, which operated to the disadvantage

of its larger heliotropes: the green earth, as if insufficiently stirred

in the mixing, has gathered, in many of them, into minute soft globules,

like air-bubbles in glass, that render them valueless for the purposes of

the lapidary, by filling them all over with little cavities; and in not a

few of the others, an infiltration of lime, that refused to incorporate

with the chalcedonic mass, exists in thin glassy films and veins, that,

from their comparative softness, have a nearly similar effect with the

impalpable green earth in roughing the surface under the burnisher.

We find figured by M'Culloch, in his "Western Islands," the

internal cavity of a pebble of Scuir More, which he picked up on the beach

below, and which had been formed evidently within one of the larger

vesicles of the amygdaloid. He describes it as curiously

illustrative of a various chemistry: the outer crust is composed of a

pale-zoned agate, inclosing a cavity, from the upper side of which there

depends a group of chalcedonic stalactites, some of them, as in ancient

spar caves, reaching to the floor; and bearing on its under side a large

crystal of carbonate of lime, that the longer stalactites pass through.

In the vesicle in which this hollow pebble was formed three consecutive

processes must have gone on. First, a process of infiltration coated

the interior all around with layer after layer, now of one mineral

substance, now of another, as a plasterer coats over the sides and ceiling

of a room with successive layers of lime, putty, and stucco; and had this

process gone on, the whole cell would have been filled with a pale-zoned

agate. But it ceased, and a new process began. A chalcedonic infiltration

gradually entered from above; and, instead of coating over the walls,

roof, and floor, it hardened into a group of spear-like stalactites, that

lengthened by slow degrees, till some of them had traversed the entire

cavity from top to bottom. And then this second process ceased like

the first, and a third commenced. An infiltration of lime took

place; and the minute calcareous molecules, under the influence of the law

of crystallization, built themselves up on the floor into a large

smooth-sided rhomb, resembling a closed sarcophagus resting in the middle

of some Egyptian cemetery. And then, the limestone crystal

completed, there ensued no after change. As shown by some other

specimens, however, there was a yet farther process: a pure quartzose

deposition took place, that coated not a few of the calcareous rhombs with

sprigs of rock-crystal. I found in the Scuir More several cellular

agates in which similar processes had gone on,—none of them quite so fine,

however, as the one figured by M'Culloch; but there seemed no lack of

evidence regarding the strange and multifarious chemistry that had been

carried on in the vesicular cavities of this mountain, as in the retorts

of some vast laboratory. Here was a vesicle filled with green

earth,—there a vesicle filled with calcareous spar,—yonder a vesicle

crusted round on a thin chalcedonic shell with rock-crystal,—in one cavity

an agate had been elaborated, in another a heliotrope, in a third a

milk-white chalcedony, in a fourth a jasper. On what principle, and

under what direction, have results so various taken place in vesicles of

the same rock, that in many instances occur scarce half an inch apart?

Why, for instance, should that vesicle have elaborated only green earth,

and the vesicle separated from it by a partition barely a line in

thickness, have elaborated only chalcedony? Why should this chamber

contain only a quartzose compound of oxygen and silica, and that second

chamber beside it contain only a calcareous compound of lime and carbonic

acid? What law directed infiltrations so diverse to seek out for

themselves vesicles in such close neighbourhood, and to keep, in so many

instances, each to its own vesicle? I can but state the problem,—not

solve it. The groups of heliotropes clustered each around its bulky

centrical mass seem to show that the principle of molecular attraction may

be operative in very dense mediæ,—in a

hard amygdaloidal trap even; and it seems not improbable, that to this

law, which draws atom to its kindred atom, as clansmen of old used to

speed at the mustering signal to their gathering place, the various

chemistry of the vesicles may owe its variety.

I shall attempt stating the chemical problem furnished by the

vesicles here in a mechanical form. Let us suppose that every

vesicle was a chamber furnished with a door, and that beside every door

there watched, as in the draught doors of our coal-pits, some one to open

and shut it, as circumstances might require. Let us suppose further,

that for a certain time an infusion of green earth pervaded the

surrounding mass, and percolated through it, and that every door was

opened to receive a portion of the infusion. We find that no vesicle

wants its coating of this earthy mineral. The coating received,

however, one-half the doors shut, while the other half remained agap, and

filled with green earth entirely. Next followed a series of

alternate infusions of chalcedony, jasper, and quartz; many doors opened

and received some two or three coatings, that form around the vesicles

skull-like shells of agate, and then shut; a few remained open, and became

as entirely occupied with agate as many of the previous ones had become

filled with green earth. Then an ample in fusion of chalcedony

pervaded the mass. Numerous doors again opened; some took in a

portion of the chalcedony, and then shut; some remained open, and became

filled with it; and many more that had been previously filled by the green

earth opened their doors again, and the chalcedony pervading the green

porous mass, converted it into heliotrope. Then an infusion of lime

took place. Doors opened, many of which had been hitherto shut, save

for a short time, when the green earth infusion obtained, and became

filled with lime; other doors opened for a brief space, and received lime

enough to form a few crystals. Last of all, there was a pure

quartzose infusion, and doors opened, some for a longer time, some for a

shorter, just as on previous occasions. Now, by mechanical means of

this character,—by such an arrangement of successive infusions, and such a

device of shutting and opening of doors,—the phenomena exhibited by the

vesicles could be produced. There is no difficulty in working the

problem mechanically, if we be allowed to assume in our data successive

infusions, well-fitted doors, and watchful door-keepers; and if any one

can work it chemically,—certainly without door-keepers, but with such

doors and such infusions as he can show to have existed,—he shall have

cleared up the mystery of the Scuir More. I have given their various

cargoes to all its many vesicles by mechanical means, at no expense of

ingenuity whatever. Are there any of my readers prepared to give it

to them by means purely chemical?

There is a solitary house in the opening of the valley, over

which the Scuir More stands sentinel,—a house so solitary, that the entire

breadth of the island intervenes between it and the nearest human

dwelling. It is inhabited by a shepherd and his wife,—the sole

representatives in the valley of a numerous population, long since

expatriated to make way for a few flocks of sheep, but whose ranges of

little fields may still be seen green amid the heath on both sides, for

nearly a mile upwards from the opening. After descending along the

precipices of the Scuir, we struck across the valley, and, on scaling the

opposite slope, sat down on the summit to rest us, about a hundred yards

over the house of the shepherd. He had seen us from below, when

engaged among the bloodstones, and had seen, withal, that we were not

coming his way; and, "on hospitable thoughts intent," he climbed to where

we sat, accompanied by his wife, she bearing a vast bowl of milk, and he a

basket of bread and cheese. And we found the refreshment most

seasonable, after our long hours of toil, and with a rough journey still

before us. It is an excellent circumstance, that hospitality grows

best where it is most needed. In the thick of men it dwindles and

disappears, like fruits in the thick of a wood; but where man is planted

sparsely, it blossoms and matures, like apples on a standard or espalier.

It flourishes where the inn and the lodging-house cannot exist, and dies

out where they thrive and multiply.

We reached the cross valley in the interior of the island

about half an hour before sunset. The evening was clear, calm,

golden-tinted; even wild heaths and rude rocks had assumed a flush of

transient beauty; and the emerald-green patches on the hill-sides, barred

by the plough lengthwise, diagonally, and transverse, had borrowed an

aspect of soft and velvety richness, from the mellowed light and the

broadening shadows. All was solitary. We could see among the

deserted fields the grass-grown foundations of cottages razed to the

ground; but the valley, more desolate than that which we had left, had not

even its single inhabited dwelling: it seemed as if man had done with it

for ever. The island, eighteen years before, had been divested of

its inhabitants, amounting at the time to rather more than four hundred

souls, to make way for one sheep-farmer and eight thousand sheep.

All the aborigines of Rum crossed the Atlantic; and at the close of 1828,

the entire population consisted of but the sheep-farmer, and a few

shepherds, his servants: the island of Rum reckoned up scarce a single

family at this period for every five square miles of area which it

contained. But depopulation on so extreme a scale was found

inconvenient; the place had been rendered too thoroughly a desert for the

comfort of the occupant; and on the occasion of a clearing which took

place shortly after in Skye, he accommodated some ten or twelve of the

ejected families with sites for cottages, and pasturage for a few cows, on

the bit of morass beside Loch Scresort, on which I had seen their humble

dwellings. But the whole of the once peopled interior remains a

wilderness, without inhabitant,—all the more lonely in its aspect from the

circumstance that the solitary valleys, with their plough-furrowed

patches, and their ruined heaps of stone, open upon shores every whit as

solitary as themselves, and that the wide untrodden sea stretches drearily

around. The armies of the insect world were sporting in the light

this evening by millions; a brown stream that runs through the valley

yielded an incessant poppling sound, from the myriads of fish that were

ceaselessly leaping in the pools, beguiled by the quick glancing wings of

green and gold that fluttered over them; along a distant hill-side there

ran what seemed the ruins of a gray-stone fence, erected, says tradition,

in a remote age, to facilitate the hunting of the deer; there were fields

on which the heath and moss of the surrounding moorlands were fast

encroaching, that had borne many a successive harvest; and prostrate

cottages, that had been the scenes of christenings, and bridals, and

blythe new-year's days,—all seemed to bespeak the place a fitting

habitation for man, in which not only the necessaries, but also a few of

the luxuries of life, might be procured; but in the entire prospect not a

man nor a man's dwelling could the eye command. The landscape was

one without figures. I do not much like extermination carried out so

thoroughly and on system;—it seems bad policy; and I have not succeeded in

thinking any the better of it though assured by the economists that there

are more than people enough in Scotland still. There are, I believe,

more than enough in our workhouses,—more than enough on our

pauper-rolls,—more than enough huddled up, disreputable, useless, and

unhappy, in the miasmatic alleys and typhoid courts of our large towns;

but I have yet to learn how arguments for local depopulation are to be

drawn from facts such as these. A brave and hardy people, favourably

placed for the development of all that is excellent in human nature, form

the glory and strength of a country; a people sunk into an abyss of

degradation and misery, and in which it is the whole tendency of external

circumstances to sink them yet deeper, constitute its weakness and its

shame; and I cannot quite see on what principle the ominous increase which

is taking place among us in the worse class, is to form our solace or

apology for the wholesale expatriation of the better. It did not

seem as if the depopulation of Rum had tended much to any one's advantage.

The single sheep-farmer who had occupied the holdings of so many had been

unfortunate in his speculations, and had left the island: the proprietor,

his landlord, seemed to have been as little fortunate as the tenant, for

the island itself was in the market; and a report went current at the time

that it was on the eve of being purchased by some wealthy Englishman, who

purposed converting it into a deer-forest. How strange a cycle!

Uninhabited originally save by wild animals, it became at an early period

a home of men, who, as the gray wall on the hill-side testified, derived,

in part at least, their sustenance from the chase. They broke in

from the waste the furrowed patches on the slopes of tile valleys,—they

reared. herds of cattle and flocks of sheep,—their number increased to

nearly five hundred souls,—they enjoyed the average happiness of human

creatures in the present imperfect state of being,—they contributed their

portion of hardy and vigorous manhood to the armies of the country,—and a

few of their more adventurous spirits, impatient of the narrow bounds

which confined them, and a course of life little varied by incident,

emigrated to America. Then came the change of system so general in

the Highlands; and the island lost all its original inhabitants, on a wool

and mutton speculation, inhabitants, the descendants of men who had chased

the deer on its hills five hundred years before, and who, though they

recognised some wild island lord as their superior, and did him service,

had regarded the place as indisputably their own. And now yet

another change was on the eve of ensuing, and the island was to return to

its original state, as a home of wild animals, where a few hunters from

the mainland might enjoy the chase for a month or two every twelvemonth,

but which could form no permanent place of human abode. Once more, a

strange and surely most melancholy cycle!

There was light enough left, as we reached the upper part of

Loch Scresort, to show us a shoal of small silver-coated trout, leaping by

scores at the effluence of the little stream along which we had set out in

the morning on our expedition. There was a net stretched across

where the play was thickest; and we learned that the haul of the previous

tide had amounted to several hundreds. On reaching the Betsey, we

found a pail and basket laid against the companion-head,—the basket

containing about two dozen small trout,—the minister's unsolicited teind

of the morning draught; the pail filled with razor-fish of great size.

The people of my friend are far from wealthy; there is scarce any

circulating medium in Rum and the cottars in Eigg contrive barely enough

to earn at the harvest in the Lowlands, money sufficient to clear with

their landlord at rent-day. Their contributions for ecclesiastical

purposes make no great figure, therefore, in the lists of the Sustentation

Fund. But of what they have they give willingly and in a kindly

spirit; and if baskets of small trout, or pailfuls of spout-fish, went

current in the Free Church, there would, I am certain, be a percentage of

both the fish and the mollusc, derived from the Small Isles, in the

half-yearly sustentation dividends. We found the supply of

both,—especially as provisions were beginning to run short in the lockers

of the Betsey,—quite deserving of our gratitude. The razor-fish had

been brought us by the worthy catechist of the island. He had gone

to the ebb in our special behalf, and had spent a tide in laboriously

filling the pail with these "treasures hid in the sand;" thoroughly aware,

like the old exiled Puritan, who eked out his meals in a time of scarcity

with the oysters of New England, that even the razor-fish, under this

head, is included in the promises. There is a peculiarity in the

razor-fish of Rum that I have not marked in the razor-fish of our eastern

coasts. The gills of the animal, instead of bearing the general colour of

its other parts, like those of the oyster, are of a deep green colour,

resembling, when examined by the microscope, the fringe of a green

curtain.

We were told by John Stewart, that the expatriated

inhabitants of Rum used to catch trout by a simple device of ancient

standing, which preceded the introduction of nets into the island, and

which, it is possible, may in other localities have not only preceded the

use of the net, but may have also suggested it: it had at least the

appearance of being a first beginning of invention in this direction.

The islanders gathered large quantities of heath, and then tying it

loosely into bundles, and stripping it of its softer leafage, they laid

the bundles across the stream on a little mound held down by stones, with

the tops of the heath turned upwards to the current. The water rose

against the mound for a foot or eighteen inches, and then murmured over

and through, occasioning an expansion among the hard elastic sprays.

Next a party of the islanders came down the stream, beating the banks and

pools, and sending a still thickening shoal of trout before them, that, on

reaching the miniature dam formed by the bundles, darted forward for

shelter, as if to a hollow bank, and stuck among the slim hard branches,

as they would in the meshes of a net. The stones were then hastily

thrown off,—the bundles pitched ashore,—the better fish, to the amount not

unfrequently of several scores, secured,—and the young fry returned to the

stream, to take care of themselves, and grow bigger. We fared richly

this evening, after our hard day's labour, on tea and trout; and as the

minister had to attend a meeting of the Presbytery of Skye on the

following Wednesday, we sailed next morning for Glenelg, whence he

purposed taking the steamer for Portree. Winds were light and

baffling, and the currents, like capricious friends, neutralized at one

time the assistance which they lent us at another. It was dark night

ere we had passed Isle Ornsay, and morning broke as we cast anchor in the

Bay of Glenelg. At ten o'clock the steamer heaved-to in the bay to

land a few passengers, and the minister went on board, leaving me in

charge of the Betsey, to follow him, when the tide set in, through the

Kyles of Skye.

CHAPTER IX.

NO sailing vessel attempts threading the Kyles of

Skye from the south in the face of an adverse tide. The currents of

Kyle Rhea care little for the wind-filled sail, and battle at times, on

scarce unequal terms, with the steam-propelled paddle. The Toward

Castle this morning had such a struggle to force her way inwards as may be

seen maintained at the door of some place of public meeting during the

heat of some agitating controversy, when seat and passage within can hold

no more, and a disappointed crowd press eagerly for admission from

without. Viewed from the anchoring place at Glenelg, the opening of

the Kyle presents the appearance of the bottom of a landlocked bay;—the

hills of Skye seem leaning against those of the mainland: and the

tide-buffeted steamer looked this morning as if boring her way into the

earth like a disinterred mole, only at a rate vastly slower. First,

however, with a progress resembling that of the minute-hand of a clock,

the bows disappeared amid the heath, then the midships, then the

quarter-deck and stern, and then, last of all, the red tip of the

sun-brightened union jack that streamed gaudily behind. I had at

least two hours before me ere the Betsey might attempt weighing anchor;

and, that they might leave some mark, I went and spent them ashore in the

opening of Glenelg,—a gneiss district, nearly identical in structure with

the district of Knock and Isle Ornsay. The upper part of the valley

is bare and treeless, but not such its character where it opens to the

sea; the hills are richly wooded; and cottages and corn-fields, with here

and there a reach of the lively little river, peep out from among the

trees. A group of tall roofless buildings, with a strong wall in

front, form the central point in the landscape: these are the dismantled

Bernera Barracks, built, like the line of forts in the great Caledonian

Valley,--Fort George, Fort Augustus, and Fort William,--to overawe the

Highlands at a time when the loyalty of the Highlander pointed to a king

beyond the water; but all use for them has long gone by, and they now lie

in dreary ruin,--mere sheltering places for the toad and the bat. I

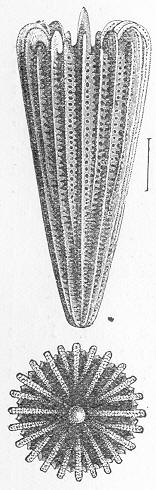

found in a loose silt on the banks of the river, at some little distance

below tide-mark, a bed of shells and coral, which might belong, I at first

supposed, to some secondary formation, but which I ascertained, on

examination, to be a mere recent deposit, not so old by many centuries as

our last raised sea-beaches. There occurs in various localities on

these western coasts, especially on the shores of the island of Pabba, a

sprig coral, considerably larger in size than any I have elsewhere seen in

Scotland; and it was from its great abundance in this bed of silt that I

was at first led to deem the deposit an ancient one.

|

|

|

Bernera Barracks, Glenelg, strategically located to

control the crossing at Kylerhea, it was built to house a garrison

of 200 soldiers. |

We weighed anchor about noon, and entered the opening of Kyle

Rhea. Vessel after vessel, to the number of eight or ten in all, had

been arriving in the course of the morning, and dropping anchor, nearer

the opening or farther away, each according to its sailing ability, to

await the turn of the tide; and we now found ourselves one of the

components of a little fleet, with some five or six vessels sweeping up

the Kyle before us, and some three or four driving on behind. Never,

except perhaps in a Highland river big in flood, have I seen such a tide.

It danced and wheeled, and came boiling in huge masses from the bottom;

and now our bows heaved abruptly round in one direction, and now they

jerked as suddenly round in another; and, though there blew a moderate

breeze at the time, the helm failed to keep the sails steadily full.

But whether our sheets bellied out, or flapped right in the wind's eye, on

we swept in the tideway, like a cork caught during a thunder shower in one

of the rapids of the High Street. At one point the Kyle is little

more than a quarter of a mile in breadth; and here, in the powerful eddie

which ran along the shore, we saw a group of small fishing-boats pursuing

a shoal of sillocks in a style that blent all the liveliness of the chase

with the specific interest of the angle. The shoal, restless as the

tides among which it disported, now rose in the boilings of one eddie, now

beat the water into foam amid the stiller dimplings of another. The

boats hurried from spot to spot wherever the quick glittering scales

appeared. For a few seconds rods would be cast thick and fast, as if

employed in beating the water, and captured fish glanced bright to the

sun; and then the take would cease, and the play rise elsewhere, and oars

would flash out amain, as the little fleet again dashed into the heart of

the shoal. As the Kyle widened, the force of the current diminished,

and sail and helm again became things of positive importance. The

wind blew a-head, steady though not strong; and the Betsey, with

companions in the voyage against which to measure herself, began to show

her paces. First she passed one bulky vessel, then another: she lay

closer to the wind than any of her fellows, glided more quickly through

the water, turned in her stays like Lady Betty in a minuet; and, ere we

had reached Kyle Akin, the fleet in the middle of which we had started

were toiling far behind us, all save one vessel, a stately brig; and just

as we were going to pass her too, she cast anchor, to await the change of

the tide, which runs from the west during flood at Kyle Akin, as it runs

from the east through Kyle Rhea. The wind had freshened; and as it

was now within two hours of full sea, the force of the current had

somewhat abated; and so we kept on our course, tacking in scant room,

however, and making but little way. A few vessels attempted

following us, but, after an inefficient tack or two, they fell back on the

anchoring ground, leaving the Betsey to buffet the currents alone.

Tack followed tack sharp and quick in the narrows, with an iron-bound

coast on either hand. We had frequent and delicate turning: now we

lost fifty yards, now we gained a hundred. John Stewart held the

helm; and as none of us had ever sailed the way before, I had the vessel's

chart spread out on the companion-head before me, and told him when to

wear and when to hold on his way,--at what places we might run up almost

to the rock edge, and at what places it was safest to give the land a good

offing. Hurrah for the Free Church yacht Betsey! and hurrah once

more! We cleared the Kyle, leaving a whole fleet tide-bound behind

us; and, stretching out at one long tack into the open sea, bore, at the

next, right into the bay at Broadford, where we cast anchor for the night,

within two hundred yards of the shore. Provisions were running

short; and so I had to make a late dinner this evening on some of the

razor-fish of Rum, topped by a dish of tea. But there is always

rather more appetite than food in the country;--such, at least, is the

common result under the present mode of distribution: the hunger overlaps