|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER IV.

THERE had been rain during the night; and when I

first got on deck, a little after seven, a low stratum of mist, that

completely enveloped the Scuir, and truncated both the eminence on which

it stands and the opposite height, stretched like a ruler across the flat

valley which indents so deeply the middle of the island. But the

fogs melted away as the morning rose, and ere our breakfast was

satisfactorily discussed, the last thin wreath had disappeared from around

the columned front of the rock-tower of Eigg, and a powerful sun looked

down on moist slopes and dank hollows, from which there arose in the calm

a hazy vapour, that, while it softened the lower features of the

landscape, left the bold outline relieved against a clear sky.

Accompanied by our attendant of the previous day, bearing bag and hammer,

we set out a little before eleven for the north-western side of the

island, by a road which winds along the central hollow. My friend

showed me as we went, that on the edge of an eminence, on which the

traveller journeying westwards catches the last glimpse of the chapel of

St Donan, there had once been a rude cross erected, and another rude cross

on an eminence on which he catches the last glimpse of the first; and that

there had thus been a chain of stations formed from sea to sea, like the

sights of a land-surveyor, from one of which a second could be seen, and a

third from the second, till, last of all, the emphatically holy point of

the island,—the burial place of the old Culdee,—came full in view. The

unsteady devotion, that journeyed, fancy-bound, along the heights, to

gloat over a dead man's bones, had its clue to carry it on in a straight

line. Its trail was on the ground; it glided snakelike from cross to

cross, in quest of dust; and, without its finger-posts to guide it, would

have wandered devious. It is surely a better devotion that, instead of

thus creeping over the earth to a mouldy sepulchre, can at once launch

into the sky, secure of finding Him who arose from one. In less than an

hour we were descending on the Bay of Laig, a semicircular indentation of

the coast about a mile in length, and, where it opens to the main sea,

nearly two miles in breadth; with the noble island of Rum rising high in

front, like some vast breakwater; and a meniscus of comparatively level

land, walled in behind by a semicircular rampart of continuous precipice,

sweeping round its shores. There are few finer scenes in the Hebrides than

that furnished by this island bay and its picturesque

accompaniments,—none that break more unexpectedly on the traveller who

descends upon it from the east; and rarely has it been seen to greater

advantage than on the delicate day, so soft, and yet so sunshiny and

clear, on which I paid it my first visit.

The island of Rum, with its abrupt sea-wall of rock, and its

steep-pointed hills, that attain, immediately over the sea, an elevation

of more than two thousand feet, loomed bold and high in the offing, some

five miles away, but apparently much nearer. The four tall summits of the

island rose clear against the sky, like a group of pyramids; its lower

slopes and precipices, variegated and relieved by graceful alternations of

light and shadow, and resting on their blue basement of sea, stood out

with equal distinctness; but the entire middle space from end to end was

hidden in a long horizontal stratum of gray cloud, edged atop with a

lacing of silver. Such was the aspect of the noble breakwater in front. Fully two-thirds of the semicircular rampart of rock which shuts in the

crescent-shaped plain directly opposite lay in deep shadow; but the sun

shone softly on the plain itself; brightening up many a dingy cottage, and

many a green patch of corn; and the bay below stretched out, sparkling in

the light. There is no part of the island so thickly inhabited as this

flat meniscus. It is composed almost entirely of Oolitic rocks, and bears

atop, especially where an ancient oyster-bed of great depth forms the

subsoil, a kindly and fertile mould. The cottages lie in groups; and, save

where a few bogs, which it would be no very difficult matter to drain,

interpose their rough shag of dark green, and break the continuity, the

plain around them waves with corn. Lying fair, green, and populous within

the sweep of its inaccessible rampart of rock, at least twice as lofty as

the ramparts of Babylon of old, it reminds one of the suburbs of some

ancient city lying embosomed, with all its dwellings and fields, within

some roomy crescent of the city wall. We passed, ere we entered on the

level, a steep-sided narrow dell, through which a small stream finds its

way from the higher grounds, and which terminates at the upper end in an

abrupt precipice, and a lofty but very slim cascade. "One of the few

superstitions that still linger on the island," said my friend the

minister, "is associated with that wild hollow. It is believed that

shortly before a death takes place among the inhabitants, a tall withered

female may be seen in the twilight, just yonder where the rocks open,

washing a shroud in the stream. John, there, will perhaps tell you how she

was spoken to on one occasion, by an over-bold, over-inquisitive islander,

curious to know whose shroud she was preparing; and how she more than

satisfied his curiosity, by telling him it was his own. It is a not uninteresting fact," added the

minister, "that my poor people, since they have become more earnest about

their religion, think very little about ghosts and spectres: their faith

in the realities of the unseen world seems to have banished from their

minds much of their old belief in its phantoms."

In the rude fences that separate from each other the little

farms in this plain, we find frequent fragments of the oyster-bed,

hardened into a tolerably compact limestone. It is seen to most

advantage, however, in some of the deeper cuttings in the fields, where

the surrounding matrix exists merely as an incoherent shale; and the

shells may be picked out as entire as when they lay, ages before, in the

mud, which we still see retaining around them its original colour.

They are small, thin, triangular, much resembling in form some specimens

of the Ostrea

deltoidea, but greatly less in size. The nearest resembling shell in Sowerby

is the Ostrea acuminata,—an oyster of the clay that underlies

the great Oolite of Bath. Few of the shells exceed an inch and half in

length, and the majority fall short of an inch. What they lack in bulk,

however, they make up in number. They are massed as thickly together, to

the depth of several feet, as shells on the heap at the door of a Newhaven

fisherman, and extend over many acres. Where they lie open we can still

detect the triangular disc of the hinge, with the single impression of the

adductor muscle; and the foliaceous character of the shell remains in

most instances as distinct as if it had undergone no mineral change. I

have seen nowhere in Scotland, among the secondary formations, so

unequivocal an oyster-bed; nor do such beds seem to be at all common in

formations older than the Tertiary in England, though the oyster itself is

sufficiently so. We find Mantell stating, in his recent work ("Medals of

Creation"), after first describing an immense oyster-bed of the London

Basin, that underlies the city (for what is now London was once an

oyster-bed), that in the chalk below, though it contains several species

of Ostrea, the shells are diffused promiscuously throughout the general

mass. Leaving, however, these oysters of the Oolite, which never net inclosed nor drag disturbed, though they must have formed the food of many

an extinct order of fish,—mayhap reptile,—we pass on in a south-western

direction, descending in the geological scale as we go, until we reach the

southern side of the Bay of Laig. And there, far below tidemark, we find a dark-coloured argillaceous shale of the Lias, greatly obscured by boulders

of trap,—the only deposit of the Liasic formation in the island.

A line of trap-hills that rises along the shore seems as if

it had strewed half its materials over the beach. The rugged blocks lie

thick as stones in a causeway, down to the line of low ebb,—memorials of

a time when the surf dashed against the shattered bases of the trap-hills,

now elevated considerably beyond its reach; and we can catch but partial

glimpses of the shale below. Wherever access to it can be had, we find it

richly fossiliferous; but its organisms, with the exception of its

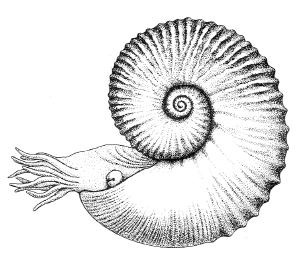

Belemnites, are very imperfectly preserved. I dug up from under the

trap-blocks some of the common Liasic Ammonites of the north-eastern coast

of Scotland, a few of the septa of a large Nautilus, broken pieces of

wood, and half-effaced casts of what seems a branched coral; but only

minute portions of the shells have been converted into stone; here and

there a few chambers in the whorls of an Ammonite or Nautilus, though the

outline of the entire organism lies impressed in the shale; and the

ligneous and Polyparious fossils we find in a still greater state of

decay. The Belemnite alone, as is common with this robust fossil,—so

often the sole survivor of its many contemporaries,—has preserved its

structure entire. I disinterred from the shale good specimens of the

Belemnite sulcatus and Belemnite elongatus, and found, detached on the

surface of the bed, a fragment of a singularly large Belemnite a full

inch and a quarter in diameter, the species of which I could not

determine.

|

|

|

| Ammonite |

Bivalve |

|

|

| Belemnite |

|

Returning by the track we came, we reach the bottom of the

bay, which we find much obscured with sand and shingle; and pass

northwards along its side, under a range of low sandstone precipices, with

interposing grassy slopes, in which the fertile Oolitic meniscus descends

to the beach. The sandstone, white and soft, and occurring in thick beds,

much resembles that of the Oolite of Sutherland. We detect in it few

traces of fossils; now and then a carbonaceous marking, and now and then

what seems a thin vein of coal, but which proves to be merely the bark of

some woody stem, converted into a glossy bituminous lignite, like that of Brora. But in beds of a blue clay, intercalated with the sandstone, we

find fossils in abundance, of a character less obscure. We spent a full

half-hour in picking out shells from the bottom of a long dock-like hollow

among the rocks, in which a bed of clay has yielded to the waves, while

the strata on either side stand up over it like low wharfs on the opposite

sides of a river. The shells, though exceedingly fragile,—for they

partake of the nature of the clayey matrix in which they are embedded,—rise as entire as when they had died among the mud, years, mayhap ages,

ere the sandstone had been deposited over them; and we were enabled at

once to detect their extreme dissimilarity, as a group, to the shells of

the Liasic deposit we had so lately quitted. We did not find in this bed a

single Ammonite, Belemnite, or Nautilus; but chalky Bivalves, resembling

our existing Tellina, in vast abundance, mixed with what seem to be a

small Buccinum and a minute Trochus, with numerous rather equivocal

fragments of a shell resembling an Oiliva. So thickly do they lie

clustered together in this deposit, that in some patches where the

sad-coloured argillaceous ground is washed bare by the sea, it seems

marbled with them into a light gray tint. The group more nearly resembles

in type a recent one than any I have yet seen in a secondary deposit,

except perhaps in the Weald of Moray, where we find in one of the layers a Planorbia scarce distinguishable from those of our ponds and ditches,

mingled with a Paludina that seems as nearly modelled after the existing

form. From the absence of the more characteristic shells of the Oolite, I

am inclined to deem the deposit one of estuary origin. Its clays were

probably thrown down, like the silts of so many of our rivers, in some

shallow bay, where the waters of a descending stream mingled with those of

the sea, and where, though shells nearly akin to our existing periwinkles

and whelks congregated thickly, the Belemnite, scared by the brackish

water, never plied its semi-cartilaginous fins, or the Nautilus or

Ammonite hoisted its membranaceous sail.

We pass on towards the north. A thick bed of an extremely

soft white sandstone presents here, for nearly half a mile together, its

front to the waves, and exhibits, under the incessant wear of the surf,

many singularly grotesque combinations of form. The low precipices;

undermined at the base, beetle over like the sides of stranded vessels. One of the projecting promontories we find hollowed through and through by

a tall rugged archway; while the outer pier of the arch,—if pier we may

term it,—worn to a skeleton, and jutting outwards with a knee-like angle,

presents the appearance of a thin ungainly leg and splay foot, advanced,

as if in awkward courtesy, to the breakers. But in a winter or two,

judging from its present degree of attenuation, and the yielding nature of

its material, which resembles a damaged mass of arrowroot consolidated by

lying in the leaky hold of a vessel, its persevering courtesies will be

over, and pier and archway must lie in shapeless fragments on the beach. Wherever the surf has broken into the upper surface of this sandstone bed,

and worn it down to nearly the level of the shore, what seem a number

of double ramparts, fronting each other, and separated by deep square

ditches exactly parallel in the sides, traverse the irregular level in

every direction. The ditches vary in width from one to twelve feet; and

the ramparts, rising from three to six feet over them, are perpendicular

as the walls of houses, where they front each other, and descend on the

opposite sides in irregular slopes. The iron block, with square groove and

projecting ears, that receives the bar of a railway, and connects it with

the stone below, represents not inadequately a section of one of these

ditches with its ramparts. They form here the sole remains of dykes of an

earthy trap, which, though at one time in a state of such high fusion that

they converted the portions of soft sandstone in immediate contact with

them into the consistence of quartz rock, have long since mouldered away,

leaving but the hollow rectilinear rents which they had occupied,

surmounted by the indurated walls which they had baked. Some of the most

curious appearances, however, connected with the sandstone, though they

occur chiefly in an upper bed, are exhibited by what seem fields of

petrified mushrooms, of a gigantic size, that spread out in some places

for hundreds of yards under the high-water level. These apparent mushrooms

stand on thick squat stems, from a foot to eighteen inches in height: the

heads are round, like those of toad-stools, and vary from one foot to

nearly two yards in diameter. In some specimens we find two heads joined

together in a form resembling a squat figure of eight, of what printers

term the Egyptian type, or, to borrow the illustration of M'Culloch, "like

the ancient military projectile known by the name of double-headed shot;"

in other specimens three heads have coalesced in a trefoil shape, or

rather in a shape like that of an ace of clubs divested of the stem. By

much the greater number, however, are spherical. They are composed of

concretionary masses, consolidated, like the walls of the dykes, though

under some different process, into a hard siliceous stone, that has

resisted those disintegrating influences of the weather and the surf under

which the yielding matrix in which they were embedded has worn from around

them. Here and there we find them lying detached on the beach, like huge

shot, compared with which the greenstone balls of Mons Meg are but marbles

for children to play with; in other cases they project from the mural

front of rampart-like precipices, as if they had been showered into them

by the ordnance of some besieging battery, and had stuck fast in the

mason-work. Abbotsford has been described as a romance in stone and lime:

we have here, on the shores of Laig, what seems a wild but agreeable tale,

of the extravagant cast of "Christabel," or the "Rhyme of the Ancient

Mariner," fretted into sandstone. But by far the most curious part of the

story remains to be told.

The hollows and fissures of the lower sandstone bed we find

filled with a fine quartzose sand, which, from its pure white colour, and

the clearness with which the minute particles reflect the light, reminds

one of accumulations of potato-flour drying in the sun. It is formed

almost entirely of disintegrated particles of the soft sandstone; and as

we at first find it occurring in mere handfuls, that seem as if they had

been detached from the mass during the last few tides, we begin to marvel

to what quarter the missing materials of the many hundred cubic yards of

rock, ground down along the shore in this bed during the last century or

two, have been conveyed away. As we pass on northwards, however, we see

the white sand occurring in much larger quantities,—here heaped up in

little bent-covered hillocks above the reach of the tide,—there

stretching out in level, ripple-marked wastes into the waves,—yonder

rising in flat narrow spits among the shallows. At length we reach a

small, irregularly-formed bay, a few hundred feet across, floored with it

from side to side; and see it, on the one hand, descending deep into the

sea, that exhibits over its whiteness a lighter tint of green, and, on the

other, encroaching on the land, in the form of drifted banks, covered with

the plants common to our tracts of sandy downs. The sandstone bed that has

been worn down to form it contains no fossils, save here and there a

carbonaceous stem; but in an underlying harder stratum we occasionally

find a few shells; and, with a specimen in my hand charged with a group of

bivalves resembling the existing conchifera of our sandy beaches, I was

turning aside this sand of the Oolite, so curiously reduced to its

original state, and marking how nearly the recent shells that lay embedded

in it resembled the extinct ones that had lain in it so long before, when

I became aware of a peculiar sound that it yielded to the tread, as my

companions paced over it. I struck it obliquely with my foot, where the

surface lay dry and incoherent in the sun, and the sound elicited was a

shrill sonorous note, somewhat resembling that produced by a waxed thread,

when tightened between the teeth and the hand, and tipped by the nail of

the forefinger. I walked over it, striking it obliquely at each step, and

with every blow the shrill note was repeated. My companions joined me; and

we performed a concert, in which, if we could boast of but little variety

in the tones produced, we might at least challenge all Europe for an

instrument of the kind which produced them. It seemed less wonderful that

there should be music in the granite of Memnon, than in the loose Oolitic

sand of the Bay of Laig. As we marched over the drier tracts, an incessant

woo, woo, woo, rose from the surface, that might be heard in the calm some

twenty or thirty yards away; and we found that where a damp semi-coherent

stratum lay at the depth of three or four inches beneath, and all was dry

and incoherent above, the tones were loudest and sharpest, and most easily

evoked by the foot. Our discovery,—for I trust I may regard it as

such,—adds a third locality to two previously known ones, in which what

may be termed the musical sand,—no unmeet counterpart to the "singing

water" of the tale,—has now been found. And as the island of

Eigg is considerably more accessible than Jabel Nakous in Arabia

Petruæa, or Reg-Rawan

in the neighbourhood of Cabul, there must be facilities presented through

the discovery which did not exist hitherto, for examining the phenomenon

in acoustics which it exhibits,—a phenomenon, it may be added, which some

of our greatest masters of the science have confessed their inability to

explain.

Jabel Nakous, or the "Mountain of the Bell," is

situated about three miles from the shores of the Gulf of Suez, in that

land of wonders which witnessed for forty years the journeyings of the

Israelites, and in which the granite peaks of Sinai and Horeb overlook an

arid wilderness of rock and sand. It had been known for many ages by the

wild Arab of the desert, that there rose at times from this hill a

strange, inexplicable music. As he leads his camel past in the heat of

the day, a sound like the first low tones of an

Æolian harp stirs the hot breezeless air. It swells louder

and louder in progressive undulations, till at length the dry baked earth

seems to vibrate under foot, and the startled animal snorts and rears, and

struggles to break away. According to the Arabian account of the

phenomenon, says Sir David Brewster, in his "Letters on Natural Magic,"

there is a convent miraculously preserved in the bowels of the hill; and

the sounds are said to be those of the "Nakous, a long metallic

ruler, suspended horizontally, which the priest strikes with a hammer, for

the purpose of assembling the monks to prayer." There exists a

tradition that on one occasion a wandering Greek saw the mountain open,

and that, entering by the gap, he descended into the subterranean convent,

where he found beautiful gardens and fountains of delicious water, and

brought with him to the upper world, on his return, fragments of

consecrated bread. The first European traveller who visited Jabel

Nakous, says Sir David, was M. Seetzen, a German. He journeyed

for several hours over arid sands, and under ranges of precipices

inscribed by mysterious characters, that tell, haply, of the wanderings of

Israel under Moses. And reaching, about noon, the base of the

musical fountain, he found it composed of a white friable sandstone, and

presenting on two of its sides sandy declivities. He watched beside

it for an hour and a quarter, and then heard, for the first time, a low

undulating sound, somewhat resembling that of a humming top, which rose

and fell, and ceased and began, and then ceased again; and in an hour and

three quarters after, when in the act of climbing along the declivity, he

heard the sound yet louder and more prolonged. It seemed as if

issuing from under his knees, beneath which the sand, disturbed by his

efforts, was sliding downwards along the surface of the rock.

Concluding that the sliding sand was the cause of the sounds, not an

effect of the vibrations which they occasioned, he climbed to the top of

one of the declivities, and, sliding downwards, exerted himself with hands

and feet to set the sand in motion. The effect produced far exceeded

his expectations: the incoherent sand rolled under and around in a vast

sheet; and so loud was the noise produced, that "the earth seemed to

tremble beneath him to such a degree, that he states he should certainly

have been afraid if he had been ignorant of the cause." At the time

Sir David Brewster wrote (1832), the only other European who had visited

Jabel Nakous was Mr Gray, of

University College, Oxford. This gentleman describes the noises he heard,

but which he was unable to trace to their producing cause, as "beginning

with a low continuous murmuring sound, which seemed to rise beneath his

feet," but "which gradually changed into pulsations as it became louder,

so as to resemble the striking of a clock, and became so strong at the end

of five minutes as to detach the sand." The Mountain of the Bell has been

since carefully explored by Lieutenant J. Welsted of the Indian navy; and

the reader may see it exhibited in a fine lithograph, in his travels, as a

vast irregularly-conical mass of broken stone, somewhat resembling one of

our Highland cairns, though, of course, on a scale immensely more huge,

with a steep angular slope of sand resting in a hollow in one of its

sides, and rising to nearly its apex. "It forms," says Lieutenant Welsted,

"one of a ridge of low calcareous hills, at a distance of three and a half

miles from the beach, to which a sandy plain, extending with a gentle rise

to their base, connects them. Its height, about four hundred feet, as well

as the material of which it is composed,—a light-coloured friable

sandstone,—is about the same as the rest of the chain; but an inclined

plane of almost impalpable sand rises at an angle of forty degrees with

the horizon, and is bounded by a semicircle of rocks, presenting broken,

abrupt, and pinnacled forms, and extending to the base of this remarkable

hill. Although their shape and arrangement in some respects may be said to

resemble a whispering gallery, yet I determined by experiment that their

irregular surface renders them but ill adapted for the production of an

echo. Seated at a rock at the base of the sloping eminence, I directed one

of the Bedouins to ascend; and it was not until he had reached some

distance that I perceived the sand in motion, rolling down the hill to the

depth of a foot. It did not, however, descend in one continued stream;

but, as the Arab scrambled up, it spread out laterally and upwards, until

a considerable portion of the surface was in motion. At their commencement

the sounds might be compared to the faint strains of an

Æolian harp when

its strings first catch the breeze: as the sand became more violently

agitated by the increased velocity of the descent, the noise more nearly

resembled that produced by drawing the moistened fingers over glass. As it

reached the base, the reverberations attained the loudness of distant

thunder, causing the rock on which we were seated to vibrate; and our

camels,—animals not easily frightened,—became so alarmed, that it was

with difficulty their drivers could restrain them."

"The hill of Reg-Rawan, or the 'Moving Sand,"' says the late

Sir Alexander Burnes, by whom the place was visited in the autumn of 1837, and who has recorded his visit in a brief paper, illustrated by a rude

lithographic view, in the "Journal of the Asiatic Society" for 1838, "is about forty miles north of Cabul, towards Hindu-kush,

and near the base of the mountains." It rises to the height of about

four hundred feet, in an angle formed by the junction of two ridges of

hills; and a sheet of sand, "pure as that of the seashore," and which

slopes in an angle of forty degrees, reclines against it from base to

summit. As represented in the lithograph, there projects over the

steep sandy slope on each side, as in "the Mountain of the Bell," still

steeper barriers of rock; and we are told by Sir Alexander, that though

"the mountains here are generally composed of granite or mica, at Reg-Rawan

there is sandstone and lime." The situation of the sand is curious,

he adds: it is seen from a great distance; and as there is none other in

the neighbourhood, "it might almost be imagined, from its appearance, that

the hill had been cut in two, and that the sand had gushed forth as from a

sand-bag." "When set in motion by a body of people who slide down

it, a sound is emitted. On the first trial we distinctly heard two

loud hollow sounds, such as would be given by a large drum;"—"there is an

echo in the place; and the inhabitants have a belief that the sounds are

only heard on Friday, when the saint of Reg-Rawan, who is interred hard by, permits." The

phenomenon, like the resembling one in Arabia, seems to have attracted

attention among the inhabitants of the country at an early period; and

the notice of an eastern annalist, the Emperor Baber, who flourished late

in the fifteenth century, and, like Cæsar, conquered and recorded his

conquests, still survives. He describes it as the Khwaja Reg-Rawan, "a

small hill, in which there is a line of sandy ground reaching from the top

to the bottom," from which there "issues in the summer season the sound

of drums and nagarets." In connection with the fact that the musical

sand of Eigg is composed of a disintegrated sandstone of the Oolite, it is

not quite unworthy of notice that sandstone and lime enter into the

composition of the hill of Reg-Rawan,—that the district in which

the hill is situated is not a sandy one,—and that its slope of sonorous

sand seems as if it had issued from its side. These various

circumstances, taken together, lead to the inference that the sand may

have originated in the decomposition of the rock beneath. It is

further noticeable, that the Jabel Nakous is composed of a white friable sandstone, resembling that of

the white friable bed of the Bay of Laig, and that it belongs to nearly

the same geological era. I owe to the kindness of Dr Wilson of Bombay, two

specimens which he picked up in Arabia Petræa, of spines of Cidarites of

the mace-formed type so common in the Chalk and Oolite, but so rare in the

older formations. Dr Wilson informs me that they are of frequent

occurrence in the desert of Arabia Petræa, where they are termed by the

Arabs petrified olives; that nummulites are also abundant in the district; and that the various secondary rocks he examined in his route through it

seem to belong to the Cretaceous group. It appears not improbable,

therefore, that all the sonorous sand in the world yet discovered is

formed, like that of Eigg, of disintegrated sandstone; and at least

two-thirds of it of the disintegrated sandstone of secondary formations,

newer than the Lias. But how it should be at all sonorous, what ever its

age or origin, seems yet to be discovered. There are few substances that

appear worse suited than sand to communicate to the atmosphere those

vibratory undulations that are the producing causes of sound: the grains,

even when sonorous individually, seem, from their inevitable contact with

each other, to exist under the influence of that simple law in acoustics

which arrests the tones of the ringing glass or struck bell, immediately

as they are but touched by some foreign body, such as the hand or finger. The one grain, ever in contact with several other grains, is a glass or

bell on which the hand always rest. And the difficulty has been felt and

acknowledged. Sir John Herschel, in referring to the phenomenon of the Jabel Nakous, in his "Treatise on Sound," in the "Encyclopædia

Metropolitana," describes it as to him "utterly inexplicable;" and Sir

David Brewster, whom I had the pleasure of meeting in December last,

assured me it was not less a puzzle to him than to Sir John. An eastern

traveller, who attributes its production to "a reduplication of impulse

setting air in vibration in a focus of echo," means, I suppose, saying

nearly the same thing as the two philosophers, and merely conveys his

meaning in a less simple style.

I have not yet procured what I expect to procure soon,—sand

enough from the musical bay at Laig to enable me to make its sonorous

qualities the subject of experiment at home. It seems doubtful whether a

small quantity set in motion on an artificial slope will serve to evolve the phenomena which have rendered

the Mountain of the Bell so famous. Lieutenant Welsted informs us,

that when his Bedouin first set the sand in motion, there was scarce any

perceptible sound heard —it was rolling downwards for many yards around

him to the depth of a foot, ere the music arose; and it is questionable

whether the effect could be elicited with some fifty or sixty pounds

weight of the sand of Eigg, on a slope of but at most a few feet, which it

took many hundredweight of the sand of Jabel Nakous, and a slope of many

yards, to produce. But in the stillness of a close room, it is just

possible that it may.* I have, however, little doubt, that from small

quantities the sounds evoked by the foot on the shore may be reproduced:

enough will lie within the reach of experiment to demonstrate the strange

difference which exists between this sonorous sand of the Oolite, and the

common unsonorous sand of our sea-beaches; and it is certainly worth while

examining into the nature and producing causes of a phenomenon so curious

in itself, and which has been characterized by one of the most

distinguished of living philosophers as "the most celebrated of all the

acoustic wonders which the natural world presents to us." In the

forthcoming number of the "North British Review,"—which appears on Monday

first,*—the reader will find the sonorous sand of Eigg referred to, in an

article the authorship of which will scarce be mistaken. "We have

here," says the writer, after first describing the sounds of Jabel

Nakous, and then referring to those of Eigg, "the phenomenon in its simple

state, disembarrassed from reflecting rocks, from a hard bed beneath, and

from Cracks and cavities that might be supposed to admit the sand; and

indicating as its cause, either the accumulated vibrations of the air when

struck by the driven sand, or the accumulated sounds occasioned by the

mutual impact of the particles of sand against each other. If a

musket-ball passing through the air emits a whistling note, each

individual particle of sand must do the same, however faint be the note

which it yields; and the accumulation of these infinitesimal vibrations

must constitute an audible sound; varying with the number and velocity of

the moving particles. In like manner, if two plates of silex or quartz,

which are but large crystals of sand, give out a musical sound when

mutually struck, the impact or collision of two minute crystals or

particles of sand must do the same, in however inferior a degree; and the

union of all these sounds, though singly imperceptible, may constitute the

musical notes of the Bell Mountain, or the lesser sounds of the trodden

sea-beach at Eigg."

Here is a vigorous effort made to unlock the difficulty. I

should, however, have mentioned to the philosophic writer,—what I

inadvertently failed to do,—that the sounds elicited from the sand of

Eigg seem as directly evoked by the slant blow dealt it by the foot, as

the sounds similarly evoked from a highly waxed floor, or a board strewed

over with ground rosin. The sharp shrill note follows the stroke,

altogether independently of the grains driven into the air. My omission

may serve to show how much safer it is for those minds of the observant

order, that serve as hands and eyes to the reflective ones, to prefer

incurring the risk of being even tediously minute in their descriptions,

to the danger of being inadequately brief in them. But, alas! for purposes

of exact science, rarely are verbal descriptions other than inadequate. Let us just look, for example, at the various accounts given us of

Jubel Nakous. There are strange sounds heard proceeding from a hill in

Arabia, and various travellers set themselves to describe them. The tones

are those of the convent Nakous, says the wild Arab;—there must be a

convent buried under the hill. More like the sounds of a humming top,

remarks a phlegmatic German traveller. Not quite like them, says an

English one in an Oxford gown; they resemble rather the striking of a

clock. Nay, listen just a little longer and more carefully, says a second

Englishman, with epaulettes on his shoulder: "the sounds at their

commencement may be compared to the faint strains of an

Æolian harp when

its strings first catch the breeze," but anon, as the agitation of the

sand increases, they "more nearly resemble those produced by drawing the

moistened fingers over glass." Not at all, exclaims the warlike Zahor

Ed-Din Muhammad Baber, twirling his whiskers: "I know a similar hill in

the country towards Hindu-kush: it is the sound of drums and nagarets that

issues from the sand." All we really know of this often-described music of

the desert, after reading all the descriptions, is, that its tones bear

certain analogies to certain other tones,—analogies that seem stronger in

one direction to one ear, and stronger in another direction to an ear

differently, constituted, but which do not exactly resemble any other

sounds in nature. The strange music of Jubel Nakous, as a

combination of tones, is essentially unique.

* March 31, 1845.

CHAPTER V.

WE leave behind us the musical sand, and reach the

point of the promontory which forms the northern extremity of the Bay of

Laig. Wherever the beach has been swept bare, we see it floored with

trap-dykes worn down to the level, but in most places accumulations of

huge blocks of various composition cover it up, concealing the nature of

the rock beneath. The long semicircular wall of precipice which,

sweeping inwards at the bottom of the bay, leaves to the inhabitants

between its base and the beach their fertile meniscus of land, here abuts

upon the coast. We see its dark forehead many hundred feet overhead,

and the grassy platform beneath, now narrowed to a mere talus, sweeping

upwards to its base from the shore,—steep, broken, lined thick with

horizontal pathways, mottled over with ponderous masses of rock.

Among the blocks that load the beach, and render our onward

progress difficult and laborious, we detect occasional fragments of an

amygdaloidal basalt, charged with a white zeolite, consisting of crystals

so extremely slender, that the balls, with their light fibrous contents,

remind us of cotton apples divested of the seeds. There occur,

though more rarely, masses of a hard white sandstone, abounding in

vegetable impressions, which, from their sculptured markings, recall to

memory the Sigilaria of the Coal Measures. Here and there, too, we

find fragments of a calcareous stone, so largely charged with compressed

shells, chiefly bivalves, that it may be regarded as a shell breccia.

There occur, besides, slabs of fibrous limestone, exactly resembling the

limestone of the ichthyolite beds of the Lower Old Red; and blocks of a

hard gray stone, of silky lustre in the fresh fracture, thickly speckled

with carbonaceous markings. These fragmentary masses,—all of them,

at least, except the fibrous limestone, which occurs in mere plank-like

bands,—represent distinct beds, of which this part of the island is

composed, and which present their edges, like courses of ashlar in a

building, in the splendid section that stretches from the tall brow of the

precipice to the beach; though in the slopes of the talus, where the lower

beds appear in but occasional protrusions and landslips, we find some

difficulty in tracing their order of succession.

Near the base of the slope, where the soil has been

undermined and the rock laid bare by the waves, there occur beds of a

bituminous black shale,—resembling the dark shales so common in the Coal

Measures,—that seem to be of freshwater or estuary origin. Their

fossils, though numerous, are ill preserved; but we detect in them scales

and plates of fishes, at least two species of minute bivalves, one of

which very much resembles a Cyclas; and in some of the fragments, shells

of Cypris lie embedded in considerable abundance. After all that has

been said and written by way of accounting for those alternations of

lacustrine with marine remains which are of such frequent occurrence in

the various formations, secondary and tertiary, from the Coal Measures

downwards, it does seem strange enough that the estuary, or fresh-water

lake, should so often in the old geologic periods have changed places with

the sea. It is comparatively easy to conceive that the inner

Hebrides should have once existed as a broad ocean-sound, bounded on one

or either side by Oolitic islands, from which streams descended, sweeping

with them, to the marine depths, productions, animal and vegetable, of the

land. But it is less easy to conceive, that in that sound, the area

covered by the ocean one year should have been covered by a fresh-water

lake in perhaps the next, and then by the ocean again a few years after.

And yet among the Oolitic deposits of the Hebrides evidence seems to exist

that changes of this nature actually took place. I am not inclined

to found much on the apparently fresh-water character of the bituminous

shales of Eigg —the embedded fossils are all too obscure to be admitted in

evidence: but there can exist no doubt, that fresh-water, or at least

estuary formations, do occur among the marine Oolites of the Hebrides.

Sir R. Murchison, one of the most cautious, as he is certainly one of the

most distinguished, of living geologists, found in a northern district of

Skye, in 1826, a deposit containing Cyclas, Paludina, Neritina,—all shells

of unequivocally fresh-water origin,—which must have been formed, he

concludes, in either a lake or estuary. What had been sea at one

period had been estuary or lake at another. In every case, however,

in which these intercalated deposits are restricted to single strata of no

great thickness, it is perhaps safer to refer their formation to the

agency of temporary land-floods, than to that of violent changes of

level,—now elevating and now depressing the surface. There occur,

for instance, among the marine Oolites of Brora,—the discovery of Mr

Robertson of Inverugie,—two strata containing fresh-water fossils in

abundance; but the one stratum is little more than an inch in

thickness,—the other little more than a foot; and it seems considerably

more probable, that such deposits should have owed their existence to

extraordinary land-floods, like those which in 1829 devastated the

province of Moray, and covered over whole miles of marine beach with the

spoils of land and river, than that a sea-bottom should have been

elevated, for their production, into a fresh water lake, and then let down

into a sea-bottom again. We find it recorded in the "Shepherd's

Calendar," that after the thaw which followed the great snow-storm of

1794, there were found on a part of the sands of the Solway Frith known as

the Beds of Esk, where the tide disgorges much of what is thrown into it

by the rivers, "one thousand eight hundred and forty sheep, nine black

cattle, three horses, two men, one woman, forty-five dogs, and one hundred

and eighty hares, besides a number of meaner animals." A similar

storm in an earlier time, with a soft sea-bottom prepared to receive and

retain its spoils, would have formed a fresh-water stratum intercalated in

a marine deposit.

Rounding the promontory, we lose sight of the Bay of Laig,

and find the narrow front of the island that now presents itself

exhibiting the appearance of a huge bastion. The green talus slopes

upwards, as its basement, for full three hundred feet; and a noble wall of

perpendicular rock, that towers over and beyond for at least four hundred

feet more, forms the rampart. Save towards the sea, the view is of

but limited extent: we see it restricted, on the landward side, to the

bold face of the bastion; and in a narrow and broken dell that runs nearly

parallel to the shore for a few hundred yards between the top of the talus

and the base of the rampart,—a true covered way,—we see but the rampart

alone. But the dizzy front of black basalt, dark as night, save

where a broad belt of light-coloured sandstone traverses it in an angular

direction, like a white sash thrown across a funeral robe,—the fantastic

peaks and turrets in which the rock terminates atop,—the masses of broken

ruins, roughened with moss and lichen, that have fallen from above, and

lie scattered at its base,—the extreme loneliness of the place, for we

have left behind us every trace of the human family,—and the expanse of

solitary sea which it commands,—all conspire to render the scene a

profoundly imposing one. It is one of those scenes in which man

feels that he is little, and that nature is great. There is no

precipice in the island in which the puffin so delights to build as among

the dark pinnacles overhead, or around which the silence is so frequently

broken by the harsh scream of the eagle. The sun had got far adown

the sky ere we had reached the covered way at the base of the rock.

All lay dark below; and the red light atop, half-absorbed by the dingy

hues of the stone, shone with a gleam so faint and melancholy, that it

served but to deepen the effect of the shadows.

The puffin, a comparatively rare bird in the inner Hebrides,

builds, I was told, in great numbers in the continuous line of precipice

which, after sweeping for a full mile round the Bay of Laig, forms the

pinnacled rampart here, and then, turning another angle of the island,

runs on parallel to the coast for about six miles more. In former

times the puffin furnished the islanders, as in St Kilda, with a staple

article of food, in those hungry months of summer in which the stores of

the old crop had begun to fail, and the new crop had not yet ripened; and

the people of Eigg, taught by their necessities, were bold cragsmen.

But men do not peril life and limb for the mere sake of a meal, save when

they cannot help it; and the introduction of the potato has done much to

put out the practice of climbing for the bird, except among a few young

lads, who find excitement enough in the work to pursue it for its own

sake, as an amusement. I found among the islanders what was said to

be a piece of the natural history of the puffin, sufficiently apocryphal

to remind one of the famous passage in the history of the barnacle, which

traced the lineage of the bird to one of the pedunculated cirripedes, and

the lineage of the cirripede to a log of wood. The puffin feeds its

young, say the islanders, on an oily scum of the sea, which renders it

such an unwieldy mass of fat, that about the time when it should be

beginning to fly, it becomes unable to get out of its hole. The

parent bird, not in the least puzzled, however, treats the case

medicinally, and,—like mothers of another two-legged genus, who, when

their daughters get over-stout, put them through a course of reducing

acids to bring them down,—feeds it on sorrel-leaves for several days

together, till, like a boxer under training, it gets thinned to the proper

weight, and becomes able not only to get out of its cell, but also to

employ its wings.

We pass through the hollow, and, reaching the farther edge of

the bastion, towards the east, see a new range of prospect opening before

us. There is first a long unbroken wall of precipice,—a continuation

of the tall rampart overhead,—relieved along its irregular upper line by

the blue sky. We mark the talus widening at its base, and expanding,

as on the shores of the Bay of Laig, into an irregular grassy platform,

that, sinking midway into a ditch-like hollow, rises again towards the

sea, and presents to the waves a perpendicular precipice of red stone.

The sinking sun shone brightly this evening; and the warm hues of the

precipice, which bears the name of Ru-Stoir,—the Red

Head,—strikingly contrasted with the pale and dark tints of the

alternating basalts and sandstones in the taller cliff behind. The

ditch-like hollow, which seems to indicate the line of a fault, cuts off

this red headland from all the other rocks of the island, from which it

appears to differ as considerably in texture as in hue. It consists

mainly of thick beds of a pale red stone, which M'Culloch regarded as a

trap, and which, intercalated with here and there a thin band of shale,

and presenting not a few of the mineralogical appearances of what

geologists of the school of the late Mr Cunningham term Primary Old Red

Sandstone, in some cases has been laid down as a deposit of Old Red

proper, abutting in the line of a fault on the neighbouring Oolites and

basalts. In the geological map which I carried with me,—not one of

high authority, however,—I found it actually coloured as a patch of this

ancient system The Old Red Sandstone is largely developed in the

neighbouring island of Rum, in the line of which the Ru-Stoir seems

to have a more direct bearing than any of the other deposits of Eigg; and

yet the conclusion regarding this red headland merely adds one proof more

to the many furnished already, of the inadequacy of mineralogical

testimony, when taken in evidence regarding the eras of the geologist.

The hard red beds of Ru-Stoir belong, as I was fortunate enough

this evening to ascertain, not to the ages of the Coccosteus and

Pterichthys, but to the far later ages of the Plesiosaurus and the fossil

crocodile. I found them associated with more reptilian remains, of a

character more unequivocal, than have been yet exhibited by any other

deposit in Scotland.

What first strikes the eye, in approaching the Ru-Stoir

from the west, is the columnar character of the stone. The

precipices rise immediately over the sea, in rude colonnades of from

thirty to fifty feet in height; single pillars, that have fallen from

their places in the line, and exhibit a tenacity rare among the

trap-rocks,—for they occur in unbroken lengths of from ten to twelve

feet,—lie scattered below; and in several places where the waves have

joined issue with the precipices in the line on which the base of the

columns rest, and swept away the supporting foundation, the colonnades

open into roomy caverns, that resound to the dash of the sea.

Wherever the spray lashes, the pale red hue of the stone prevails, and the

angles of the polygonal shafts are rounded; while higher up all is

sharp-edged, and the unweathered surface is covered by a gray coat of

lichens. The tenacity of the prostrate columns first drew my

attention. The builder scant of materials would have experienced no

difficulty in finding among them sufficient lintels for apertures from

eight to twelve feet in width. I was next struck with the peculiar

composition of the stone: it much rather resembles an altered sandstone,

in at least the weathered specimens, than a trap, and yet there seemed

nothing to indicate that it was an Old Red Sandstone. Its

columnar structure bore evidence to the action of great heat; and its pale

red colour was exactly that which the Oolitic sandstones of the island,

with their slight ochreous tinge, would assume in a common fire. And

so I set myself to look for fossils. In the columnar stone itself I

expected none, as none occur in vast beds of the unaltered sandstones, out

of some one of which I supposed it might possibly have been formed; and

none I found: but in a rolled block of altered shale of a much deeper red

than the general mass, and much more resembling Old Red Sandstone, I

succeeded in detecting several shells, identical with those of the deposit

of blue clay described in a former chapter. There occurred in it the

small univalve resembling a Trochus, together with the oblong bivalve,

somewhat like a Tellina; and, spread thickly throughout the block, lay

fragments of coprolitic matter, and the scales and teeth of fishes.

Night was coming on, and the tide had risen on the beach; but I hammered

lustily, and laid open in the dark red shale a vertebral joint, a rib, and

a parallelogramical fragment of solid bone, none of which could have

belonged to any fish. It was an interesting moment for the curtain

to drop over the promontory of Ru-Stoir: I had thus already found

in connection with it well nigh as many reptilian remains as had been

found in all Scotland before,—for there could exist no doubt that the

bones I laid open were such; and still more interesting discoveries

promised to await the coming morning and a less hasty survey. We

found a hospitable meal awaiting us at a picturesque old two-storey house,

with, what is rare in the island, a clump of trees beside it, which rises

on the northern angle of the Oolitic meniscus; and after our day's s hard

work in the fresh sea-air, we did ample justice to the viands. Dark

night had long set in ere we reached our vessel.

Next day was Saturday; and it behoved my friend the

minister,—as scrupulously careful in his pulpit preparations for the

islanders of Eigg as if his congregation were an Edinburgh one,—to remain

on board, and study his discourse for the morrow. I found, however,

no unmeet companion for my excursion in his trusty mate John Stewart.

John had not very much English, and I had no Gaelic; but we contrived to

understand one another wonderfully well; and ere evening I had taught him

to be quite as expert in hunting dead crocodiles as myself. We

reached the Ru-Stoir, and set hard to work with hammer and chisel.

The fragments of red shale were strewed thickly along the shore for at

least three quarters of a mile;—wherever the red columnar rock appeared,

there lay the shale, in water-worn blocks, more or less indurated; but the

beach was covered over with shingle and detached masses of rock, and we

could nowhere find it in situ. A winter storm powerful enough to

wash the beach bare might do much to assist the explorer. There is a

piece of shore on the eastern coast of Scotland, on which for years

together I used to pick up nodular masses of lime containing fish of the

Old Red Sandstone; but nowhere in the neighbourhood could I find the

ichthyolite bed in which they had originally formed. The storm of a

single night swept the beach; and in the morning the ichthyolites lay

revealed in situ under a stratum of shingle which I had a hundred

times examined, but which, though scarce a foot in thickness, had

concealed from me the ichthyolite bed for five twelvemonths together!

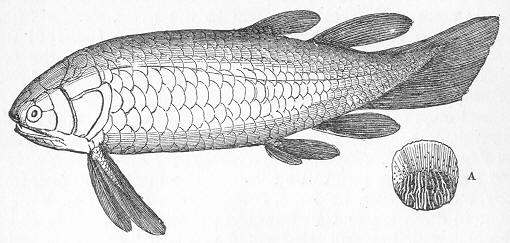

Wherever the altered shale of Ru-Stoir has been thrown

on the beach, and exposed to the influences of the weather, we find it

fretted over with minute organisms, mostly the scales, plates, bones, and

teeth of fishes. The organisms, as is frequently the case, seem

indestructible, while the hard matrix in which they are embedded has

weathered from around them. Some of the scales present the

rhomboidal outline, and closely resemble those of the Lepidotus Minor

of the Weald; others approximate in shape to an isosceles triangle.

The teeth are of various forms: some of them, evidently palatal, are mere

blunted protuberances glittering with enamel—some of them present the

usual slim, thorn-like type common in the teeth of the existing fish of

our coasts,—some again are squat and angular, and rest on rectilinear

bases, prolonged considerably on each side of the body of the tooth, like

the rim of a hat or the flat head of a scupper nail. Of the

occipital plates, some present a smooth enamelled surface, while some are

thickly tuberculated,—each tubercle bearing a minute depression in its

apex, like a crater on the summit of a rounded hill. We find

reptilian bones in abundance,—a thing new to Scotch geology,—and in a

state of keeping peculiarly fine. They not a little puzzled John

Stewart: he could not resist the evidence of his senses: they were bones,

he said, real bones,—there could be no doubt of that: there were the

joints of a back-bone, with the hole the brain-marrow had passed through;

and there were shankbones and ribs, and fishes' teeth; but how, he

wondered, had they all got into the very heart of the hard red stones?

He had seen what was called wood, he said, dug out of the side of the

Scuir, without being quite certain whether it was wood or no; but there

could be no uncertainty here. I laid open numerous vertebræ

of various forms,—some with long spinous processes rising over the body or

centrum of the bone,—which I found in every instance, unlike that

of the Ichthyosaurus, only moderately concave on the articulating faces;

in others the spinous process seemed altogether wanting. Only two of

the number bore any mark of the suture which unites, in most reptiles, the

annular process to the centrum; in the others both centrum and process

seemed anchylosed, as in quadrupeds, into one bone; and there remained no

scar to show that the suture had ever existed. In some specimens the

ribs seem to have been articulated to the sides of the centrum; in others

there is a transverse process, but no marks of articulation. Some of

the vertebræ are evidently dorsal, some

cervical, one apparently caudal; and almost all agree in showing in front

two little eyelets, to which the great descending artery seems to have

sent out blood-vessels in pairs. The more entire ribs I was lucky

enough to disinter as in those of crocodileans, double heads; and a part

of a fibula, about four inches in length, seems also to belong to this

ancient family. A large proportion of the other bones are evidently

Plesiosaurian. I found the head of the flat humerus so

characteristic of the extinct order to which the Plesiosaurus has been

assigned, and two digital bones of the paddle, that, from their

comparatively slender and slightly curved form, so unlike the digitals of

its cogener the Ichthyosaurus, could have belonged evidently to no other

reptile. I observed, too, in the slightly-curved articulations of

not a few of the vertebræ, the gentle

convexity in the concave centre, which, if not peculiar to the

Plesiosaurus, is at least held to distinguish it from most of its

contemporaries. Among the various nondescript organisms of the

shale, I laid open a smooth angular bone, hollowed something like a

grocer's scoop; a three-pronged caltrop-looking bone, that seems to have

formed part of a pelvic arch; another angular bone, much massier than the

first, regarding the probable position of which I could not form a

conjecture, but which some of my geological friends deem cerebral; an

extremely dense bone, imperfect at each end, which presents the appearance

of a cylinder slightly flattened; and various curious fragments, which,

with what flattened our scotch museums have not acquired,—entire reptilian

fossils for the purposes of comparison,—might, I doubt not, be easily

assigned to their proper places. It was in vain that, leaving John

to collect the scattered pieces of shale in which the bones occurred, I

set myself again and again to discover the bed from which they had been

detached. The tide had fallen; and a range of skerries lay

temptingly off, scarce a hundred yards from the water's edge: the

shale-beds might be among them, with Plesiosauri and crocodiles stretching

entire; and fain would I have swam off to them, as I had done oftener than

once elsewhere, with my hammer in my teeth, and with shirt and drawers in

my hat; but a tall brown forest of kelp and tangle, in which even a seal

might drown, rose thick and perilous round both shore and skerries; a

slight swell was felting the long fronds together; and I deemed it better,

on the whole, that the discoveries I had already made should be recorded,

than that they should be lost to geology, mayhap for a whole age, in the

attempt to extend them.

The water, beautifully transparent, permitted the eye to

penetrate into its green depths for many fathoms around, though every

object presented, through the agitated surface, an uncertain and

fluctuating outline. I could see, however, the pink-coloured urchin

warping himself up, by his many cables, along the steep rock-sides; the

green crab stalking along the gravelly bottom; a scull of small rock-cod

darting hither and thither among the tangle-roots; and a few large medusæ

slowly flapping their continuous fins of gelatine in the opener spaces, a

few inches under the surface. Many carious families had their

representatives within the patch of sea which the eye commanded; but the

strange creatures that had once inhabited it by thousands, and whose bones

still lay sepulchred on its shores, had none. How strange, that the

identical sea heaving around stack and skerry in this remote corner of the

Hebrides should have once been thronged by reptile shapes more strange

than poet ever imagined,—dragons, gorgons, and chimeras! Perhaps of

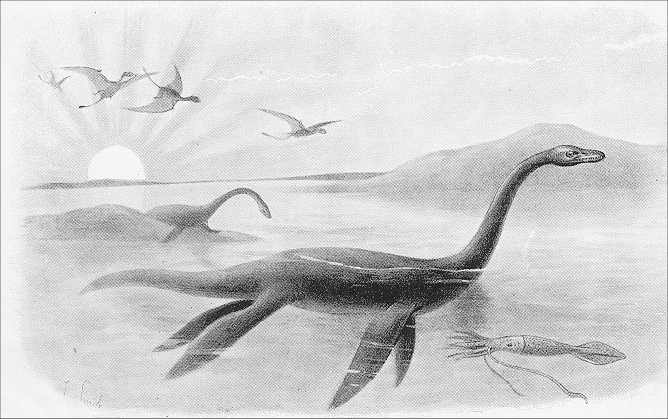

all the extinct reptiles, the Plesiosaurus was the most extraordinary.

An English geologist has described it, grotesquely enough, and yet in most

happily, as a snake threaded through a tortoise. And here, on

this very spot, must these monstrous dragons have disported and fed; here

must they have raised their little reptile heads and long swan-like necks

over the surface, to watch an antagonist or select a victim; here must

they have warred and wedded, and pursued all the various instincts of

their unknown natures. A strange story, surely, considering it is a

true one! I may mention in the passing, that some of the fragments

of the shale in which the remains are embedded have been baked by the

intense heat into an exceedingly hard, dark-coloured stone, somewhat

resembling basalt. I must add further, that I by no means determine

the rock with sand which we find it associated to be in reality an altered

sandstone. Such is the appearance which it presents where weathered;

but its general aspect is that of a porphyritic trap. Be it what it

may, the fact is not at all affected, that the shores, wherever it occurs

on this tract of insular coast, are strewed with reptilian remains of the

Oolite.

|

|

Plesiosaurus |

The day passed pleasantly in the work of exploration and

discovery; the sun had already declined far in the West; and, bearing with

us our better fossils, we set out, on our return, by the opposite route to

that along the Bay of Laig, which we had now thrice walked over. The

grassy talus so often mentioned continues to run on the eastern side of

the island for about six miles, between the sea and the inaccessible

rampart of precipice behind. It varies in breadth from about two to

four hundred yards; the rampart rises over it from three to five hundred

feet; and a noble expanse of sea, closed in the distance by a still nobler

curtain of blue hills, spreads away from its base: and it was along this

grassy talus that homeward road lay. Let the Edinburgh reader

imagine the fine walk under Salisbury Crags lengthened some twenty

times,—the line of precipices above heightened some five or six times,—the

gravelly slope at the base not much increased in altitude, but developed

transversely into a green undulating belt of hilly pasture, with here and

there a sunny slope level enough for the plough, and here and there a

rough wilderness of detached crags and broken banks; let him further

imagine the sea sweeping around the base of this talus, with the nearest

opposite land—bold, bare, and undulating atop—some six or eight miles

distant; and he will have no very inadequate idea of the peculiar and

striking scenery through which, this evening, our homeward route lay.

I have scarce ever walked over a more solitary tract. The sea shuts

it in on the one hand, and the rampart of rocks on the other; there occurs

along its entire length no other human dwelling than a lonely summer

shieling; for full one-half the way we saw no trace of man; and the

wildness of the few cattle which we occasionally startled in the hollows

showed us that man was no very frequent visitor among them. About

half an hour before sunset we reached the midway shieling.

Rarely have I seen a more interesting spot, or one that, from

its utter loneliness, so impressed the imagination. The shieling, a

rude low-roofed erection of turf and stone, with a door in the centre some

five feet in height or so, but with no window, rose on the grassy slope

immediately in front of the vast continuous rampart. A slim pillar

of smoke ascends from the roof, in the calm, faint and blue within the

shadow of the precipice, but it caught the sun-light in its ascent, and

blushed, ere it melted into the ether, a ruddy brown. A streamlet

came pouring from above in a long white thread, that maintained its

continuity unbroken for at least two-thirds of the way; and then,

untwisting into a shower of detached drops, that pattered loud and

vehemently in a rocky recess, it again gathered itself up into a lively

little stream, and, sweeping past the shieling, expanded in front into a

circular pond, at which a few milch cows were leisurely slaking their

thirst. The whole grassy talus, with a strip, mayhap a hundred yards

wide, of deep green sea, lay within the shadow of the tall rampart; but

the red light fell, for many a mile beyond, on the glassy surface; and the

distant Cuchullin Rills, so dark at other times, had all their prominent

slopes and jutting precipices tipped with bronze; while here and there a

mist streak, converted into bright flame, stretched along their peaks, or

rested on their sides. Save the lonely shieling, not a human

dwelling was in sight. An island girl of eighteen, more than merely

good-looking, though much embrowned by the sun, had come to the door to

see who the unwonted visitors might be, and recognised in John Stewart an

old acquaintance. John informed her in her own language that I was

Mr Swanson's sworn friend, and not a Moderate, but one of their own

people, and that I had fasted all day, and had come for a drink of milk.

The name of her minister proved a strongly recommendatory one: I have not

yet seen the true Celtic interjection of welcome,—the kindly "O o

o,"—attempted on paper; but I had a very agreeable specimen of it on this

occasion, viva voce. And as she set herself to prepare for us

a rich bowl of mingled milk and cream, John and I entered the shieling.

There was a turf fire at the one end, at which there sat two little girls,

engaged in keeping up the blaze under a large pot, but sadly diverted from

their work by our entrance; while the other end was occupied by a bed of

dry straw, spread on the floor from wall to wall, and fenced off at the

foot by a line of stones. The middle space was occupied by the

utensils and produce of the dairy,—flat wooden vessels of milk, a butter

churn, and a tub half-filled with curd; while a few cheeses, soft from the

press, lay on a shelf above. The little girls were but occasional

visitors, who had come out of a juvenile frolic, to pass the night in the

place; but I was informed by John that the shieling had two other inmates,

young women, like the one so hospitably engaged in our behalf, who were

out at the milking, and that they lived here all alone for several months

every year, when the pasturage was at its best, employed in making butter

and cheese for their master, worthy Mr M'Donald of Keill. They must

often feel lonely when night has closed darkly over mountain and sea, or

in those dreary days of mist and rain so common in the Hebrides, when

nought may be seen save the few shapeless crags that stud the nearer

hillocks around them, and nought heard save the moaning of the wind in the

precipices above, or the measured dash of the wave on the wild beach

below. And yet they would do ill to exchange their solitary life and

rude shieling for the village dwellings and gregarious habits of the

females who ply their rural labours in bands among the rich fields of the

Lowlands, or for the unwholesome back-room and weary task-work of the city

seamstress. The sun-light was fading from the higher hill-tops of

Skye and Glenelg, as we bade farewell to the lonely shieling and the

hospitable island girl.

The evening deepened as we hurried southwards along the

scarce visible pathway, or paused for a few seconds to examine some

shattered block, bulky as a Highland cottage, that had fallen from the

precipice above. Now that the whole landscape lay equally in shadow,

one of the more picturesque peculiarities of the continuous rampart came

out more strongly as a feature of the scene than when a strip of shade

rested along the face of the rock, imparting to it a retiring character,

and all was sunshine beyond. A thick bed of white sandstone, as

continuous as the rampart itself; runs nearly horizontally about midway in

the precipice for mile after mile, and, standing out in strong contrast

with the dark-coloured trap above and below, reminds one of a belt of

white hewn work in a basalt house-front, or rather—for there occurs above

a second continuous strip, of an olive hue, the colour assumed, on

weathering, by a bed of amygdaloid—of a piece of dingy old-fashioned

furniture, inlaid with one stringed belt of bleached holly, and another of

faded green-wood. At some of the more accessible points I climbed to

the line of white belting, and found it to consist of the same soft

quartzy sandstone that in the Bay of Laig furnishes the musical sand.

Lower down there occur, alternating with the trap, beds of shale and of

blue clay, but they are lost mostly in the talus. Ill adapted to resist

the frosts and rains of winter, their exposed edges have mouldered into a

loose soil, now thickly covered over with herbage; and, but for the

circumstance that we occasionally find them laid bare by a water-course,

we would scarce be aware of their existence at all. The shale

exhibits everywhere, as on the opposite side of the Ru-Stoir, faint

impressions of a minute shell resembling a Cyclas, and ill-preserved

fragments of fish-scales. The blue clay I found at one spot where

the pathway had cut deep into the hill-side, richly charged with bivalves

of the species I had seen so abundant in the resembling clay of the Bay of

Laig; but the closing twilight prevented me from ascertaining whether it

also contained the characteristic univalves of the deposit, and whether

its shells,—for they seem identical with those of the altered shales of

the Ru-Stoir,—might not be associated, like these, with reptilian

remains. Night fell fast, and the streaks of mist that had mottled

the hills at sunset began to spread gray over the heavens in a continuous

curtain; but there was light enough left to show me that the trap became

more columnar as we neared our journey's end. One especial jutting

in the rock presented in the gloom the appearance of an ancient portico,

with pediment and cornice, such as the traveller sees on the hill-sides of

Petræa in front of some old tomb but it

may possibly appear less architectural by day. At length, passing

from under the long line of rampart, just as the stars that had begun to

twinkle over it were disappearing, one after one, in the thickening

vapour, we reached the little bay of Kildonan, and found the boat waiting

us on the beach. My friend the minister, as I entered the cabin,

gathered up his notes from the table, and gave orders for the tea-kettle;

and I spread out before him—a happy man—an array of fossils new to Scotch

Geology. No one not an enthusiastic geologist or a zealous Roman

Catholic can really know how vast an amount of interest may attach to a

few old bones. Has the reader ever heard how fossil relics once saved the

dwelling of a monk, in a time of great general calamity, when all his

other relics proved of no avail whatever?

Thomas Campbell, when asked for a toast in a society of

authors, gave the memory of Napoleon Bonaparte; significantly adding, "he

once hung a bookseller." On a nearly similar principle I would be

disposed to propose among geologists a grateful bumper in honour of the

revolutionary army that besieged Maestricht. That city, some

seventy-five or eighty years ago, had its zealous naturalist in the person

of M. Hoffmann, a diligent excavator in the quarries of St Peter's

mountain, long celebrated for its extraordinary fossils. Geology, as

a science, had no existence at the time; but Hoffmann was doing, in a

quiet way, all he could to give it a beginning —he was transferring from

the rock to his cabinet, shells, and corals, and crustacea, and the teeth

and scales of fishes, with now and then the vertebræ,

and now and then the limb-bone, of a reptile. And as he honestly

remunerated all the workmen he employed, and did no manner of harm to any

one, no one heeded him. On one eventful morning, however, his

friends the quarriers laid bare a most extraordinary fossil,—the occipital

plates of an enormous saurian, with jaws four and a half feet long,

bristling over with teeth, like chevaux de frise; and after

Hoffmann, who got the block in which it lay embedded, out entire, and

transferred to his house, had spent week after week in painfully relieving

it from the mass, all Maestricht began to speak of it as something really

wonderful. There is a cathedral on St Peter's mountain,—the mountain

itself is church-land; and the lazy canon, awakened by the general talk,

laid claim to poor Hoffmann's wonderful fossil as his property. He

was lord of the manor, he said, and the mountain and all that it contained

belonged to him. Hoffmann defended his fossil as he best could in an

expensive lawsuit; but the judges found the law clean against him; the

huge reptile head was declared to be "treasure trove" escheat to the lord

of the manor; and Hoffmann, half broken-hearted, with but his labour and

the lawyer's bills for his pains, saw it transferred by rude hands from

its place in his museum, to the residence of the grasping churchman.

The huge fossil head experienced the fate of Dr Chalmers' two hundred

churches. Hoffmann was a philosopher, however, and he continued to

observe and collect as before; but he never found such another fossil; and

at length, in the midst of his ingenious labours, the vital energies

failed within him, and he broke down and died. The useless canon

lived on. The French Revolution broke out; the republican army

invested Maestricht; the batteries were opened; and shot and shell fell

thick on the devoted city. But in one especial quarter there

alighted neither shot nor shell. All was safe around the canon's

house. Ordinary relics would have availed him nothing in the

circumstances,—no, not "the three kings of Cologne," had he possessed the

three kings entire, or the jaw-bones of the "eleven thousand virgins;" but

there was virtue in the jaw-bones of the Mosasaurus, and safety in their

neighbourhood. The French savans, like all the other

savans of Europe, had heard of Hoffmann's fossil, and the French

artillery had been directed to play wide of the place where it lay.

Maestricht surrendered; the fossil was found secreted in a vault, and sent

away to the Jardin des Plantes at Paris, maugre the canon, to