|

ADVENTURES AT BLACKPOOL.

|

EH, BILL! COME TO BLACKPOOL.

EH,

BILL, come to Blackpool! an' bring

thi Wife, Mary,

Hoo looks fairly run deawn wi' moilin' through t' day;

An' bring Jack an' Nelly — that curly-nobbed fairy —

That cowf ut hoo's getten ull soon pass away.

It's lively just neaw — for there's crowds o' folk

walkin'

Up an' deawn th' Promenade fro' mornin' till neet;

They're as happy as con be, lowfin' an' tawkin' —

By gum, Blackpool just neaw's a rally grand seet!

Come on to Blackpool — yo' may spend a nice hower

In a sail fro' th' North Pier to Fleetwood an' back;

Or a grand afternoon i' roamin' through th' Tower,

For th' monkeys an' tigers ull pleose yore Jack.

Yo' may goo on to th' piers — there's skatin' an' dancin',

Or ride to th' South Shore, an' get fun eaut o' th' fair;

Or tak' th' childer on t' sands, an' jine i' their

prancin',

An' help um build castles — theau's built some i'th' air

Get ready: come neaw! for I've getten a notion

Ut a sniff o'th' briny ull do yo aw good;

An' breathin' th' ozone fro' th' owd rollickin' ocean

Is th' reet soart o' physic to tingle one's blood.

Yo want'en a change — maybe Fayther Time's markin'

A notch in his stick as each yer ebbs away;

So pack up thi luggage, tha connot keep warkin' —

If tha o'erdraws Natur, tha'll have to repay.

So come on to Blackpool, yo'll never repent it,

It's a rare bracin' place for owd folk an' young,

This invite's i' good faith, tha'll be glad as I sent

it,

It's a good salve for dumps to mix up wi' t'thrung.

It's a lovely sayside for rest or for pleasure,

Wi' th' waves rowlin' high or just lavin' one's feet;

Yo' may strowl upo' th' cliffs — get health without

measure,

So come, an' durnt miss such a glorious treat.

LANGFORD SAUNDERS |

CHAPTER I.

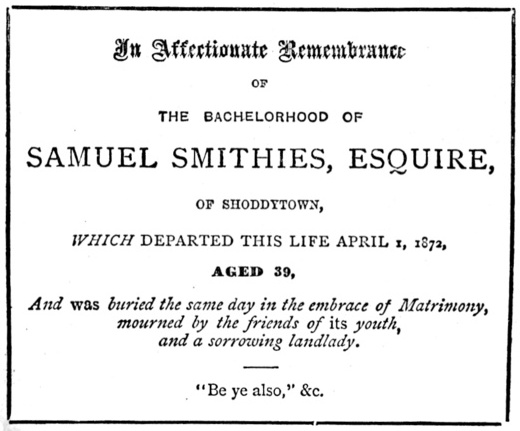

SAM

SMITHIES has turned up

again; and moore than that, he's getten hissel' hooked. If yo'

wanten me t' be a bit plainer, he's ta'en to hissel' a "rib" ut he

didno' keaunt on th' last time we yerd abeaut him. Made me get to

know this, someb'dy sent me a mournin' card a week or two sin' with

this on—

"What a pity!" eaur Sal said, when hoo'd read th' card.

"What is?" I said, seein' ut hoo're knockin' her yead again a

gravestone.

"Wheay ut he's deead," hoo said, pooin a face as would ha been quite

lung enoogh for th' deeath of a rich uncle. "He looked likely enoogh

when he're livin'."

"Theaw's getten howd o' th' wrung end o' that lot," I said. "Sam's nobbut put his neck in a noose."

"What, an' hanged hissel'?" hoo said, wi' a shudder.

"Hanged hissel' i' one sense, but not in another," I said. "He taks

his wynt just same as he did, I dar'say; but for liberty o' limb,

an' havin' his own road, he's as deead as a dur-nail."

"Prison?" the owd un said, throwin' up her e'en in a mystarious way.

"Reet, owd jockey, this time," I said. "Sam's a prisoner in his own heause. He's getten

wed. That's what he's gone an' done."

Hoo whizzed hersel' reaund when hoo yerd that; threw the card i' th'

fire, an' dashed into th' loomheause.

"Bobbins!" hoo sheauted, in a snappy way. "Knock that lad off th'

stoo' if he doesno' get on with his wyndin'. Yo'r o alike; that's

what yo' are." Then her shuttle went as fast as her tongue does

sometimes.

Just as I're ponderin' abeaut things, and wonderin' if I should set

mysel' reet wi' Sam neaw he'd happened this misfortin', Dick, th'

hostler, popt in, an' said I're wanted at th' Owd Bell. I snaiked my

hat off th' peg at once, an' shot eaut o' th' heause while eaur

Sal's loom wur gooin', for t' see whoa it wur ut wanted me. When I geet deawn to th' owd rallyin'-shop whoa should I find theere but

Sam Smithies an' his new wife, lookin' as breet an' as glossy, they

wur, as a pair o' buzzerts. I're rayther gloppent, I con tell yo',

but I must put th' best face on't I could.

"Ab," Sam said, gettin howd o' my hont, an' shakin' it in his owd-fashint way, "let bygones be by-gones. Heaw arta? This is my

wife. Minnie, love, Ab-o'-th'-Yate." An' he turned to his

new rib,

an' grinned like a doancin'-mesther.

"Do, sir?" his wife whispered, as if spakin' gradely would ha'

brasted her. And hoo offered me a kid gloove, as if

hoo wanted me to poo it off her hont.

I said I're toll-loll, and hoped hoo're th' same.

" 'K you! How is Mrs. Fletcher?"

"Quite remarkable," I said.

" 'K you! Would you—a—." I couldno' exactly catch what hoo whispered

beside; but, aimin' rooghly at th' mark, I said—

"Well, I'd as lief have a pint as owt yo' con set me."

"I mean, would you have the kindness to introduce me to—a—Missis

Fletcher?" hoo said, a bit leauder this time, ut fotcht some colour

i' my face. I could see I'd put my foout in't, as us'al.

"Ay," I said; "I'd do that in a minit, if hoo're here."

"Can't you send?"

"Here, Dick," Sam said to th' hostler, "goo an' fetch th' owd

stockin-mender, too, an' they con have a bit of a confab while we

looken at th' picthurs."

"Sam-u-el!"his wife said. An' hoo messurt him wi' her e'en fro' his

toppin to his boots. I could see by that hoo're puttin' th' break

on, in her way.

Well, Dick th' hostler wur sent up to th' fowt for eaur Sal; but

he must ha' made a mess of his arrand, for had to come back hissel',

an' in a bit of a fluster, too. Eaur Sal sent word ut if anybody

wanted to see her they must go up to th' cote, as hoo couldno'

purtend to leave th' neest, an' let th' eggs go cowd.

This wur a riddle to Sam's wife; but when I explained to her ut th'

owd lass were upo' th' push wi' her wark, becose Whissundy wur close

on, hoo said hood goo up an' see her, hersel', if anybody would show

her th' road. So Dick the hostler wur shopt again; an' he must ha'

done his wark gradely this time, becose he showed me a sixpence when

he coome back, an' gan me a wink ut I could quite understond.

As soon as Sam an' me had getten peearcht by eaursels, i' th' owd

way, wi' two picthurs afore us, ut didno' go feaw wi' starin' at, he

gan me a slap upo' th' knee ut made me jump, an' axt me what I thowt

abeaut his bargain.

"Hoo's a beauncer," I said, "if I mun look at her in a stable leet. Wheere hast' piked her up?"

"Wheere dost think?" he said.

"Not at Number two, Gloster Terrace, Hyde Park?" I said. Sam gan me

a look ut went through me.

"Ab," he said, givin' his lip a bit of a worryin', "no moore o' that! Keep off sore places. If theau will hit me strike it wheere's seaund.

Her ut theau coed Lady Mary Constance Stanhope is no' fit to

lace my wife's stays."

"I'm fain to yer it," I said; "an as theau's made sich a good

bargain theau con afford to forgive me. But whoa is hoo, and wheere didt' leet on her?" I could see he're fairly brastin' for t' tell me

o abeaut her, an happen a great deeal more than he knew.

"Hoo's my wife neaw," he said; "but hoo wur a barmaid at a hotel i'

Manchester when I met wi' her at fust."

"Oh, wur hoo?" I said. "Theau's bin middlin' lucky i' that job,

Sam; becose barmaids generally han their e'en abeaut 'em, an' winno'

be pi'ked up wi' tinkers. Theau didno' tell her as mich as I could

ha' towd her abeaut thee. Whor!"

"Husht!" he said, an' winked.

"Oh, I am not one to set mischief agate between mon an' wife," I

said. "Theau may trust Ab."

"Theau doesno' live in a steel heause thysel'," Sam said; "so theau

hadno' better begin a-cloddin" (throwing sods or stones.)

"I think," I said, "we'd noather on us best say nowt. Quietness is th' best,' as th' Owd Poot says. But wheere art livin' neaw?"

"Ive takken a heause within a mile o' here," he said; "but I thowt

I'd bring th' wife a-lookin' at it afore I closed th' bargain. Hoo

likes th' place fust rate. We's be neighbours again, theau sees."

"Ay, but theau dar'no' find thy road here as oft as theau used to

do," I said; "an' it winno' do for thee t' carry on i' th' bar as

I've seen thee do mony a time. Yond woman favvors look-in' after

thee, an' hookin' thy cheean up a link or two."

"That's what I took her for," he said. "I wanted th' break puttin'

on, or else I should ha' bin at th' bottom o' th' broo afore my

time. Well, han yo're Sarah an' thee bin off anywheere this—I

con hardly co it summer?"

"Dost meean to some sae-side, or summat?" I axt.

"Ay; Blackpool, or anywheere."

"Nawe," I said; "but if th' weather changes for th' better eaur Sall

'll be gruntin' in a week or two. Folk conno' stood fine weather

awhoam neaw."

"My new rib—I con hardly co' her an owd un yet—is goooin' to New

Brighton next week," Sam said. "Theau'd better let yore Sarah goo wi'

her. I know hoo'll ax her to goo; that's what hoo's gone a-seein'

her for."

"Hoo con goo anywheere hoo likes when hoo's emptied her loom," I

said. "I never meddle wi' noather her gooin'-eaut nor her comin'-in;

if I did, hoo'd have her own road after o."

"It'll be o reet then?"

"Ay."

"That'll do. Neaw, then, just hearken me," an' Sam hutched his

cheear close to mine, and whispered: "When they'n getten nicely

away," he said, "thee an' me con slip off to Blackpool, an' shake a

lose leg for a week. Dar' theau try it on?"

"I dar' do owt ut theau dar'," I said.

"Agreed on, then," Sam said. "I'll stond ex's. But th' wives munno'

get to know abeaut it, noather. If they dun there'll be th' very Owd

Lad to play."

"It winno' get eaut through me," I said. "My leease o' comfort is

rayther too temporairy for that; an' if yond woman isno' th' mesther

o' thee neaw, theau may calkilate hoo will be afore lung; so it ud

be dangerous for thee if theau split."

"Honour bright, Ab!" he said.

So we'd another pint a-piece; an' afore we'd finished that, an' said

o we could like t' ha said, Sam's wife coome sailin' in, wi' a bunch

o' wall-flowers in her hont ut eaur Sal had gar her. I could see by

that ut they'd getten on weel t'gether, an' wur very likely as thick

as inklewayvers afore they'd known one another five minits. Women

con manage a job o' that sort better than men. Hoo said th' owd rib

wur a "delightful person," an' no' quite as owd as hoo expected

findin' her. Eaur Sal had consented to goo wi' her to New Brighton

if I should ha' no objections; an' hoo thowt hoo'd be a "very

pleasant companion" for her. "A sedate and motherly body," an' I dunno' know what th' owd lass wurno' beside. A woman's opinion o'

women is summat like th' weather, subject to changes.

Sam winked at me, and I winked back again; an' I fancied I could see

a bit o' mischief just abeaut bein' put i' th' brewin'-tub.

Well, we had to part to meet again, as th' owd sung says. Sam would tak' care ut ther' nowt went wrung o' his part; an' if I'd keep my

own keaunsel, and mind what I're doin', things would goo on as nice

as ninepence. So we shaked honds an' parted; Sam an' his wife gooin'

a-seein' heaw th' papper-daubers wur gettin' on ut their new

heause, an' me to see heaw my owd hearthstone picthur looked wi New

Brighton in her yead.

I fund th' owd lass quite brisk, knockin' away at her loom as if

hoo'd shake it to pieces. Hoo towd me what a nice eaut hoo'd a

chance o' havin' if I'd nobbut give my consent to it; but hoo should

goo whether I consented or not. Heaw did I intend makkin' my time

away while hoo're off? I couldno' do better, hoo thowt, than stick

fast to my loom for th' week; and then when hoo coome back I could

have a day to mysel' i' th' "Boggart Hole Cloof," if I wanted a haliday.

I agreed wi' her ut that would be a very nice arrangement,

partikilar th' Cloof bizness. Very likely Sam Smithies would come

o'er an' spend th' day wi' me; an' we could sit under th' trees

drinkin' churn-milk an' hearknin' th' brids sing, till we'rn as

happy as two foos. Th' owd lass looked quite angel-faced at that,

an' thowt Sam an' me wur comin' to eaur senses. Hoo're sure Sam wur,

or else he'd never ha' getten howd o' sich a nice lady as he had for

a wife; not he.

O' this way we humbugged one another till bedtime.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

TH' day coome ut

eaur Sal and Sam Smithies' wife had to set eaut for New Brighton.

It wurno' one o' th' finest mornin's I'd seen i' my time. Th'

wynt wur raythur blustery, and seemed to have a bit of a notion o'

gettin' up a storm. Donkeys turned their tails to'ard th'

hedge, an' lambs favvort thinkin' they'd come-n i' th' wo'ld afore

mint wur ripe. Th' rain kept off, for a wonder, though ther an

ugly cleaud or two lumberin' abeaut th' sky, lookin' as if they

wanted to spoil somebody's clooas. Ther a cab sent for th' owd

rib; and a rare wakes it made i' Walmsley Fowt. O th' childer

abeaut wanted to ride; an' they co'ed it a "four-wheeled

feel-loss-o'-speed." It took the biggest part of an heaur for

t' get th' owd lass off; hoo had to get in an' eaut so oft, through

forgettin' summat. At lung length hoo geet sattled deawn in

her seeat, wi' her box eautside, fastened wi' a strap, an' a noggin

o' gin in a alegar bottle inside, for t' keep th' wynt fro' blowin'

through th' nicks o' th' cab window. Th' last words hoo said

to me, as hoo beawled out o' th' fowt, wur—

"Ab, thee stick to thy loom while I'm away, an' I winno'

begrudge thee a day to thysel' when I come back."

"Reet, owd crayther," I said; "we'n manage as weel as we're

able. Send me word heaw theau'rt getten on, an' if I dunno'

write back it'll be becose I'm too busy. Ta, tah!" An

off hoo went, like a queen.

Th' owd damsel had no sooner getten eaut o' th' seet than I

slipt deawn to th' Owd Bell, wheere I expected meetin' Sam Smithies,

fore t' mak' eaur arrangements for gooin' to Blackpool th' day

after. Sam turned up in abeaut twenty minits wi' a carpet-bag

for me, an' a spyin'-glass for hissel', ut he'd borrowed somewheere.

We'd mony a crack o' laafin o'er what we'rn gooin' to do; an when

Sam towd me ut his wife advised him to stick to bizness while hoo're

away, an' not ha' so mich o' th' smell o' 'bacco-reech in his clooas

when hoo coome back, we'd ha' gradely yawp eaut.

Th' day went roogher as it grew owder, so that when neet

coome th' wynt blew what Sam co'ed "big guns." He thowt eaur

wives would be stoppin' i' Liverpool that neet. They'd never

cross o'er to New Brighton while th' weather wur so roogh. But

th' mornin' after it wur a deeal quieter. It looked very

promisin' for Blackpool, if it would nobbut keep on. Eaur

childer thowt I're followin' their mother; an' I didno' contradict 'em,

but said I met no' come back above a day afore her. They'rn 'i

fine glee o'er bein' laft by theirsels. They said they could

mak' th' porritch any thickness, an' have as mich traycle to 'em as

they'd a mind. It's a grand thing for childer to ha' liberty

to deeal wi' their stomachs as they liken.

We crept quietly off to Manchester, an' as quietly we took

eaur seeats i' th' train for Blackpool; Sam Smithies lookin' quite

fidgetty till th' engine whistled. When we began a movin' he

threw up his arms in a wild fashin, an' said—

"Theigher, Ab, we're safe. Eaut wi' that 'lubricator!"'

I had to carry th' "lubricator," as Sam co'ed a bottle o'

whiskey, an' he carried th' cigars. So we supt and smooked,

and wur as merry as a gang o' sondknockers, till we geet to Prest'n.

Then we tumbled o'er th' hedge into th' land o' Nod, wheere we

tarried till we'rn wakkent up at Poult'n fort' give up eaur tickets.

Th' next stage wur Blackpool, where we fund th' sky as breet as a

new-polished dish-cover, an' th' waves rowlin' o'er one another like

a hay-meadow on th' spree. I'd four or five women howd on me

directly, axin' me if I wanted lodgin's. They may co'

Blackpool a healthy place, but there must be a good deeal o'

widows theere, or else they wouldno' ha' poo'd me abeaut as they

did. Sam shoothert 'em off like a pack o' beggars, an' said we

mustno' bother wi' common folk; we must go to an hotel, an' be

grand. Ther one, a new un, kept by a friend of his wife's, ut

wur a bar-manager at th' same place as hoo're at hersel' once, an'

we must go theere. He coed it th' "Darby Hotel."

Anywheere wur reet for me, bein' as I'd nowt to pay; so to th'

"Darby" we went, and I fund we'd getten a nice shop on't. I

felt mysel' awhoam in a snifter; an' when we'd had a wesh, an' a

tidy sort of a waistcoat-tightenin', Ab wur as reet as a wooden

clock.

"Neaw, then, owd swell!" Sam said, after we'd made eaursels

comfortable,"we're no' gooin' t' sit fuddlin' o' th' time we're i'

Blackpool, if other folk dun. Let's have a blow i' some

gradely wynt. What dost' say abeaut a strowl as far as Uncle

Tom's Cabin while th' weather's fine?"

"Anywheere for me so as I'm th' reet end up," I said.

"I hope Uncle Tom 'll be awhoam."

"Come on, then. It's a good brisk walk theere an' back;

but we shanno' be choked wi' shoddy dust upo' th' road, an' that's

summat. There'll be some fun stirrin', I dar'say."

So to Uncle Tom's Cabin we went, gooin' deawn by th' lower

road, for t' save tow-brass. Sam didno' believe i' payin' tow

(toll) for one pair o' legs, as if we'd bin hosses or jackasses.

It wur a breezy walk, I con tell yo'; an' what wi' my hat fittin'

rayther slack, an' my cooat-laps flappin' abeaut my ears, I'd a busy

time on't. Sam, seein' heaw I're bothert wi' havin' t' howd my

arms up, poo'd eaut abeaut a yard and a-hauve o' blue ribbin', ut

he'd saved eaut o' owd Dizzy's do-ment, an' passin it o'er th' gable

end o' my hat, tee'd it under my chopper, ut made me look like a

pace-egger. It wur fun to Sam, an' to mony a one beside, seein'

me donned up i' royal colours, as if I're leeadin' th' British fleet

up. Some youngsters we met on th' road—I think they must ha'

bin nail-getherers fro' Chow-bent [Ed.—now Atherton], or

weight tarrers fro' Owdham—set up a sheaut when they see'd me; an'

one said—

"See yo', lads, this men's ta'en th' fust prize i' th' donkey

show. Let's give him three cheers."

So they gan me three cheers, for which I could like to ha'

thanked 'em wi' my clogs, if I'd had 'em wi' me.

When we geet to Uncle Tom's Cabin we fund they a lot o' folk

theere ut had come-n moore for a frolic than for any good they

expected to get eaut o' sae-wynt. They'rn doancin', young an'

owd, to th' tootlin' of a band; an' Sam an' me went in wi' th' lot,

as brisk as th' best on 'em. We'd one another for partners as

lung as th' women would alleaw us; an' that, yo'r sure, wouldno' be

lung. After th' fust twell, we'rn collared, neck and crop, by

two women i' black—no' quite th' hondsomest ut ever I'd clapt my

e'en on, but wi' little bit moore than their share o' divulment in 'em—an'

we'rn whizzed reaund like peg-tops, till I leet bang wi' my yead

again th' cabin, and seed sae an' lond runnin' after one another as

if they'rn tryin' which could get to Ameriky th' fust. That

wur th' finish o' my doancin'; an' if it had bin th' finish o' th'

spree, nob'dy would ever ha' yerd abeaut eaur gooin' to Blackpool.

But wheer women are mischief 's sure to be. I've fund it so,

at any rate; an' my exparience didno' begin yesterday.

"Are you hurt?" my owd damsel said to me, seein' ut I're a

bit dazed wi' my bang.

"No' mich," I said. "I've a collar-booan an' a rib or

two missin', that's o. If anybody finds 'em I hope they'n turn

'em up."

"Dear me!" hoo said, lookin' abeaut her as if hoo'd dropt

her—her—what-dun-they-co'-it—improver, or summat, "Whatever

must we do?"

"Never mind, owd crayther," I said; "I've a lot moore to

change on, so ut it doesno' matter mich."

Hoo gan me a quiet slap i' th' face for that, an said I're a

"funny fellow." Happen I am to some folk. I wur to her,

at any rate; for after that I couldno' shake her off. Whatever

I said to her, it wur no use. When I thowt I'd put th' capper

on by tellin' her I'd a wife and sixteen childer, hoo said I met as

well ha' towd her fifty. Hoo didno' believe ut I're wed at o.

Even when Sam put in an' said I'd missed th' keaunt o' my family by

an odd twin ut I hadno' reckont, hoo wouldno' swallow a word.

If I'd had a wife, hoo're sure hoo'd ha bin wi' me if hoo're owt

like other wives. I'd forgetter then ut it wur lip

(leap) year. But when I did bethink mysel', I could see

danger i' th' look-eaut.

After this bit of a marlock we went a-seein' Uncle Tom, an'

fund him a jolly sort of a chap, an' one ut could sing a good sung

when he're wanted. He towd us he'd built th' cabin hissel',

an' th' greaund it stood on wur one time coed "Little Lunnon," an'

wur a rallyin' shop for th' lads an' wenches o' Blackpool o' Sunday

neets an' pastimes. Th' fust consarn wur summat like a black-pae

shop, slated wi' a rag. Ther no "penky" sowd theere at that

time. Nowt nobbut gingybread and nuts. After that he put

a bit o' wood reaund his carcase, an' a gradely roof o'er his yead.

Then strangers began a-comin'; an' if they could find a level yard

or two o' greaund they'rn sure to begin a-doancin on it. Chus

heaw big he made his cote it kept bein' too little till it geet to

what it is neaw. He'd as mich ale an' stuff i' stock as would

fuddle o Blackpool for a week, an' he didno' think any on't would be

alleawed to go seaur. But he sowd a deeal o' cakes an' things

to childer ut coome a-swingin' upo' th' swings, an' lookin' for

shells upo' th' sands. Owd Neptune had gan him notice every

winter for mony a year ut he should want th' greaund after a

while; an' he're a londlord ut nob'dy would think o' shootin'; not

even thoose mad yorneys ut thinken abeaut nowt nobbut pistils an'

cowd leead if they conno' have their own road i' everythin', an' mak

everybody think as they thinken',—leatheryeads!

Leeavin' Uncle Tom's Cabin, an' slippin' th' women i' black,

we made eaur way to'ard th' owd pier, an' had a penn'oth o wynt fro'

th' top end; my blue ribbin bein' fun for everybody we met.

Sam had a squint through his spyin'-glass; an' he said he could see

a boat wi' two women in it far eaut to'ard Liverpool. One had

a fat humbrell wi' her, an' wur middlin' plump hersel'; an' th'

tother favvort hoo'd bin browt up to pumpin' ale, an' messurin'

whiskey. They'rn comin this road at a deuce of a rate.

He calkilated they'd lond i' Blackpool in abeaut an heaur, if they'd

luck.

"They're never th' wives, surely, Sam," I said. An' I

began a-feelin' rayther quire abeaut th' top storey o' my stomach.

If wo'rn nobbled there'd be a bit of a dogbattle comin' off, an' a

bullbait too, an' what besides I couldno' tell. "Con theau mak

'em eaut yet?" I said.

"I'm feart I con mak' 'em eaut too weel," he said, rubbin th'

end o' th' glass wi' his napkin. "Had thy wife a green an

black shawl on, Ab?"

"Hoo had," I said; "a pattern as big as a flag."

"We're dropt on then," he said, very sayriously. "Look

for thysel'."

I geet howd o' th' glass, and poked it o'er a rail; then shut

one e'e, and put it to th' end o' th' glass.

"I con see nowt nobbut darkness," I said. "My e'en

munno' be o' th' reet sort for spyin' wi'."

"Why, theau yorney, theau's shut th' wrung e'e," Sam said.

An' so I had.

I swapt peepers, an' looked again. This time I could

see dayleet, if I could see nowt else.

"Just aim at yond speck i' th' distance," Sam said; "an' howd

th' glass steady. Theau'rt o of a wakker."

"An' so would theau be," I said, "if theau'd th' white

Sargent just getten howd o' thy collar and I feel as if mine wur i'

th' grip o'ready. I con see nowt yet, nobbut th' sae rowlin'

abeaut. Howd! Neaw I see summat. Nowt like a boat,

noather. It's more like a big dog muzzle o' th' top of a

three-legs."

"Ay, it's th' beacon o' th' end o' th' new pier," Sam said.

"Let me have another peep."

So he geet howd o' th' glass again, and had another squint;

and when he'd looked abeaut a minit he said—

"By my stockin's, Ab, it's domino wi' us; I con see 'em neaw

as plain as I con see thee. What mun we do?"

"I'm off back this minit, if there's a train," I said.

"I'd as lief meet th' Garmans as eaur Sal here. Come, shut

that bobbin-sucker up, and let's be off."

"Howd," Sam said; "let's see if they look anyways poorly fust.

Ha!—um!—they are no' women. They're two fishermen. I con

see 'em drawin' a net neaw."

"I wish they'd throw it o'er thee," I said, "for puttin' me

this fluster." It's my belief he'd seen nowt at o.

Noather his wife nor mine would ha' ventured upo' th' sae i' that

weather, I're sure. But I're feart for o that.

After comin' off th' pier we'd a strowl upo' what they co'en

the "Promenade." That's wheere folk do nowt but walk an' ride

abeaut, an' stare at one another in a genteel fashin. We could

see men i'clooas they wouldno' be seen wearin' abeaut whoam; and

women strollopin' abeaut in a way ut i' Walmsley Fowt would be coed

brazent. But then they'rn ladies; an' I reckon that mak's a

bit o' difference. Some wur ridin' jackasses; an' th' poor

things ut wur carryin' 'em wur havin' their skins pown wi' sticks

till, as Sam towd me, when they dee'n it'll come off their booans i'

ready-made leather. A great looberin' foo' i' specktekles, an'

ut could hardly keep his feet off th' greaund, passed us, stroddlin'

across a bit of a ragged rottan ut had barely gan o'er suckin'; and

its legs wabbled abeaut as if they'rn goin' t' snap. A lad wur

busy palin' it wi' a thick stick till yure flew, but th' little

thing could hardly totter on chus heaw he mauled it.

"Theau doesno' know heaw to droive a donkey," Sam said to th'

lad. "Theau does nowt but tickle it. Just land me th'

stick, an' I'll mak' him goo smartly."

"Sam, dunno' thee ill-use th' poor crayther," I said; "it's

badly enoogh off as it is."

But he geet howd o' th' stick wi' a firm an' savage-lookin'

grip, an' aimin a blow ut I calkilated would ha' knocked a bigger

animal deawn than that poor brute, catcht th' rider just below his

jacket buttons, an' made him fly o'er th' donkey's yead like a

hunter o'er a fence.

"Beg pardon," Sam said to th' chap, ut wur rubbin' a sore

place, an' starin o'er his specktekles. "Sorry I missed my

aim, but this animal is so very stupid. I know him of old.

Hope you're not much hurt."

"Rather," th' chap said, twistin' his meauth under one ear,

an' rubbin'; "but it can't be helped, I suppose. Accidents

will happen." He favvort havin' some deauts abeaut it bein' an

accident, too, but I reckon he didno' know heaw to mend hissel'

after he'd messurt Sam's weight. Heawever, he'd had enoogh o'

ridin' for that beaut, an' he turned away, leeavin' Sam an' me welly

brastin wi' fun. Th' donkey looked as fain as owt, an'

exercised it ears an' tail quite briskly.

"Yond mon'll no' go t' sleep this next hauve-heaur," Sam

said, as we went on. "He'll be sore for mony a day, I'll bet.

An' sarve him reet, too, for a lung slammockin' cauve! I could

like t' read th' same lesson to a lot moore yorneys. Better

than writin' to newspappers abeaut 'em. Heaw he flew!

He's rubbin' yet." An' he wur.

We coome to an owd-fashint sort of a heause, wi' a

churn-milk-and-traycle-coloured front, ut I could see wur co'ed "Oak

Cottage," an' ut somb'dy o' th' name o' "Samuel Laycock" lived at

it, an' took likenesses. A mon ut favvort bein' made eaut o'

humbrell wire wur potterin abeaut amung some picthurs ut wur in a

glass case fixed to th' railins i' th' front o' th' heause.

He're stript in his shirt sleeves, an' wur bare-yead. Thinkin'

he met tell me summat abeaut thoose ut lived theere, I axt him if he

knew Sam Laycock. He said he thowt he did.

"Is he owt akin to him ut writes po'try? " I axt.

"Th' same potato," he said.

"Never, surely!" I said.

"Yo'n find they're booath one."

"Dost think I could get to have a peep at him?" I said.

"Well, if yo'n mak' yor hont into a telescope, an' look at me,"

he said, "yo'n see his wife's husbant." An' he gan me a squint

eaut of abeaut th' twentieth part o' one e'e, as if here usin a

spyin'-glass hissel'.

"Theau doesno' say!" I said, quite in a gloppent way.

"Well, I'm fain t' see thee, owd lad!—that I am. Let's

have a wag o' thy pen-howder." An' we shaked honds heartily,

while Sam Smithies wur lookin' at th' likenesses. "An' theau

writes po'try?"

"A bit; sometimes."

"Dost think theau could manufactur a line or two abeaut

me?" I said.

He twitched up his snuffer as a hoss does it tail when flees

are plaguin' it; an' givin' me another pin-yead look eaut o'th'

telescope peeper, said—

"I'll try."

"Blaze away, then," I said.

He scrat his toppin abeaut a minit, an' then he said—

|

Ther' coome a stranger to my dur;—

At fast aw wondered who he wur;

But when aw seed his knobbly pate,

Thinks aw t' mysel'—that's Ab-o'-th' Yate. |

"Brayvo!" I said. "Po'try an' fortin-tellin' come'n as

nattural to thee as atin' and drinkin'. But theau'rt no' doin'

mich i' th' jingle line neaw, I think?"

"Nawe; I ha' no time," he said. "Folk ut come a-seein'

me, an' stoppin' at my heause—I tak' in visitors, yo' seen—find me

as mich as I con do wi' takkin their likenesses. Th' day's

rayther too far gone neaw, or else I could like t' ha' ta'en

someb'dy's ut I've been wantin' to see a good while."

"Wait till t' morn, an' theaus't have a fling at me," I said;

"an, I'll bring this tother chap wi' me. I darno' tell thee

whoa he is neaw; but he's a great mon!"

"Is he?" Laycock said, wi' another screwin up o' one side of

his jib.

"Ay," I said, "theau'll be surprised when theau yers his

name." An' wishin' one another a good afternoon we parted for

t' meet again th' day after.

Neet wur comin' on, an' Sam Smithies thowt it wur time to be

creepin' to eaur cote, an' flyin' up. So we turned eaur toes

to'ard th' Darby Hotel, an' ordered a dacent sort of a neet-cap for

a finisher. We could do wi' a bit o' supper, Sam thowt, an' I

felt th' same. So it wur ordered at once.

"There are two ladies taking supper in the dining-room up

stairs," th' londlady said. "I don't think they'd have any

objections to your joining them, if you've no objections. They

appear to be nice people."

"Moore an' th' merrier," Sam said, jumpin' up. "Come

on, Ab; let's goo an' peg into some provender; theau looks middlin'

sharp set. We'n have a bottle o' thy favourite pop

for't wesh it deawn with."

"O reet!" I said, an' upstairs we went.

When we geet into th' dinin'-reaum whoa should we find sittin'

at th' table but thoose two widows i' black ut we'd bin doancin'

with at Uncle Tom's Cabin.

"We're met again, ladies," Sam said, in his swaggerin',

beauncin' way. "Would you permit us to join you?"

"Yes, and welcome," one on 'em said, with an ancient grin.

"Thank you!" So Sam an' me dropt deawn to th' table,

aside o' one another, wi' th' women no' far off us. Sam carved

at some cowd salmon, an' then ut th' beef; an' I kept him at his

wark middin' stiffly. Yo may be sure they a bit o' talk gooin'

on at th' same time; an' th' ladies helped us at th' pop,

till their tongues geet as lose as a women's club-neet. They'd

bin seechin us, they said, ever sin they missed us at Uncle Tom's

Cabin; but little did they think we'rn stoppin' at th' same place.

It wur like a thing ut must be, they said, an' they tittert an'

purtended to shawm like two country wenches at a weddin'. We'd

hard wark to keep 'em at arm's length, I con tell yo; but when Sam

towd 'em we'rn members of a "Married Men's Protection Society," an'

i' full benefits, they behaved theirsels a bit moore becominly.

Or else they'd getten so far as to co Sam a "duck," an me a "goose;"

an' it wur "dear" this and "dear" th' tother, very nee every word.

We'd another bottle o "fizz;" an' then th' clatter went on famously.

"Can you drive, dear?" one o' th' women said to Sam, quite

languishinly.

"Like a circus," Sam said.

"Then suppose we've a carriage to-morrow, an' go to Lytham?

Beautiful drive."

"Agreed on," Sam said, an' he winked at me.

"I feel ready for any mortal thing," I said. Th' "fizz"

wur gettin' howd on me, yo seen.

"Deelightful! Oh, we shall have such fun!" an' they

slapt their honds as if they'd just yerd ut someb'dy had left em a

fortin.

I didno' feel quite sure ut it would be so very "deelightful"

becose I'd a bit of a misgivin, o' someheaw, ut o wouldno' be

straightforrad. Heawever, things wur gettin' on bravely so

far; an' I sang, an' Sam sang, an' I believe th' women would ha'

tuned their pipes wi' a bit o' pressin'. I geet up an' made a

bit of a speech, praisin' th' owd damsels for their beauty an' their

young looks, till I calkilated they'd smash th' lookinglass next

time they stood i' th' front o' one. As a finisher up, I

filled a glass o' pop for't drink their health. Sam did

th' same; an' I framed mysel' for th' job, like th' cheearmon of a

pig-show dinner.

I'd getten howd o' my glass, un wur just sayin'—"Ladies,"

when th' dur oppent, an' in marched eaur Sal an' Sam's wife, like a

pair o' boggarts.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

"OH, my!" th' owd

rib soiked.

"Goodness me!" Sam Smithies' wife said.

"Ab!"

"Sam-u-el!" And then ther three or four seconds o'

sultry quietness, same as ther is sometimes before a heavy clap o'

thunner.

I think ut any sort of a reaum, an' speshly at a public-heause,

owt to have two durs to it, so ut there'd be a better chance o'

gettin' eaut i' case o' fire, or summat as dangerous. A second

dur would ha' bin very ready i' eaur case; but bein' as ther nobbut

one, an' that blockaded wi' two fifty-gunners, turned broadside on

us, th' best thing we could do wur to lay deawn arms, an' give

eaursel's up to th' tender mercies o' th' enemy.

"What does all this mean?" Sam's wife said, lookin' fust at

us an' then at th' widows.

"Ay, what does it meean?" eaur Sal said, clearin' for action.

Noather Sam nor me could say just then what it did meean, for we'rn

booath on us knockt of a lump.

"What are you doing here?" Sam's wife screeamed eaut in her

topmost key, an' givin' Sam a witherin' look.

"What art theau doin' here?" my owd blossom sheauted,

makkin' a rustle of her bonnet ribbins.

"In such company as this, too!" Sam's wife went on.

"Two women with 'em!" eaur Sal hinted, rayther strungly.

"Is there something wrong?" one o' th' widows axt, with a

very innocent look.

"Something wrong!" Sam's wife said, savagely.

"Summat wrung!" th' owd rib followed up, an warmin' upo' th'

road. "There's nowt reet here, I'm sure."

"I ask you again, all of you, what does this mean?" Sam's

wife said, wi' another pitch on her top note.

"I should like to know what this intrusion means," one

o' th' widows said, lookin' a bit nettled after th' fust surprise

wur o'er.

"Yes, indeed!" tother damsel said, throwin' her yead back

like a hee-mettled tit when it's bin blown wi' a run.

"Intrusion!" Sam's wife gan eaut, rippin' her gloves

off, as if hoo'd bin scauded. "The idea—the idea that we

should be supposed to be intruding!"

"We did not send for you," widow number one said, as

quietly as if hoo'd bin givin' a poorly body some physic; "and the

gentlemen assured us they were alone."

"Send for us!" eaur Sal skriked eaut, givin' a

flourish of her humbrell ut looked dangerous. "If yo' thinken

yo'n moore right to eaur husbants than we han, tak' 'em. Yo'r

welcome to mine, at any rate."

"Husbands!" booath widows said, starin' at one another like

throttled earwigs.

"Yes, husbands!" Sam's wife said, gettin' howd o' her share

o' creation's peerage by th' collar, an' shakin' his champagne up.

"That gentleman," one o'th' widows said, pointin' to Sam,

"assured us they were both single men." Then hoo gan me a look

ut I could hardly read th' meeanin' on.

"What a thumper!" I said. An' I struck th' table wi' my

fist. "Didno' I tell yo' at Uncle Tom's Cabin ut I'd a wife

an' sixteen childer?"

"Seventeen, Ab! Seventeen, owd cockalorum!" Sam

sheauted. He'd gone as fuddled as a foo' o at once; an' chus

heaw his wife shaked him he wouldno' spake another word, so I're

laft for't feight th' battle eaut mysel'.

"Are you this gentleman's wife?" widow number two said to

eaur Sal, at th' same time pointin' at me.

"I'm this foo's wife," th' owd un said savagely "moore's

th' pity I should be, wi' sich carryins-on as these."

"And is it really true that you have seventeen children?"

"I'll let him know whether I have or not;" an' th' owd

stockinmender set to an' began a-palin' me abeaut th' shoothers wi'

her humbrell, till I thowt hoo'd ne'er ha' gan o'er. "This is

yor gooin' to Boggart Hole Cloof," hoo said, after hoo'd made her

humbrell look like a crow-neest ut's bin i' some heavy weather.

"I can believe owt abeaut thee neaw ut's bad enoogh, theau great

bobbin-hat!" an' hoo gan me a finishin' welt wi' her ruffled

gingham. "Nice, very nice, ut as soon as one turns one's back

they mun come a-gallivantin' here. Heaw did yo' leet on

'em? I'll believe yo' neaw, afore oather o' these—these—I

dunno' know what to co 'em."

"Speak for your own husband, Missis Fletcher," Sam's wife

said, givin' her human bargain a rooghish sort of a cuddle, fort'

wakken him up. Brave woman, that.

"We met them at Uncle Tom's Cabin," widow number one said;

an' hoo spoke like a pa'son. "They chose us as partners in a

dance, and so conducted themselves as to lead us to suppose they

were single men. There was nothing more than that, I can

assure you. My friend and I have been staying here several

days, and were at supper this evening—alone, mind you—when, to our

surprise, these gentlemen walk into the room, and ask if they might

be allowed to take supper at the same table. Now you know

everything."

Noather eaur Sal nor Sam's wife had a word to say to that;

an' number one went on.

"We are staying at this hotel; this is a public dining-room,

and we have a right to the use of it unmolested by anyone.

Good night!" Wi' that they booath rose fro' their cheears, an'

makkin a sort of a duckin' bow at th' dur, sailed eaut o' th' reaum.

"An' a nice pair o' blossoms I dar' say yo are," th' owd un

said when th' widows had laft us. Then hoo set at me wi' o her

moral teeth, an' would draw eaut a confession. I towd her th'

truth o abeaut it, leeavin' a good lump for Sam to face up when

he're sober. I whitewesht mysel' famously; an' geet th' owd

ticket so far reconciled ut hoo'd drink a glass o' "fizz," an' taste

a bit o' salmon. Sam's wife coome reaund, too, after a

slatterin o' e'e-wayter; an' three eaut o' th' four on us seemed to

get i' th' humour for takkin things as they coome. One hardly

knows when it's rainin' heaw soon th' owd Sun may peep eaut.

Just as I're finishin' my peeace-makkin a waiter coome in,

an' said we'rn wanted deawn stairs. Sam wakkent up in a crack,

an' looked as if he'd never tasted o' nowt that neet; an' his wife

took his arm like one ut could forgive owt ut coome short o' murder.

Eaur Sal said hoo'd mend o' that when hoo'd catcht him in as mich

lumber as I'd bin in mysel'. Thank thee, Sarah!

Well, we went deawn th' stairs, o four on us, an' fund it wur

th' two widows ut wanted a bit moore of eaur company. I fancy

th' londlady had bin explainin things to'em. They'rn sit in a

parlour by theirsels, an' looked as demure as two owdfashint stone

angels. They rose up as we went into th' reaum, an' begged

eaur pardon for a start; but it wur "the ladies only" ut they wanted

to see, a piece o' news ut wur quite welcome to th' "gentlemen."

Sam gan me th' wink, an' shoothert me eaut o' th' reaum; and then we

went into th' bar for t' wait till sich times as this she parlyment

had done their bizness. If I mun spake for Sam we felt like

two lads ut had just missed a good threshin', an' getten off wi'

nowt but a bit o' strung talkin' to. No deaut th' wust wur

o'er as far as we'rn consarned eaur two sels; but we expected yerrin'

a mixture o' leaud tongue waggin' i' th' parlour, if it didno' come

to a tumblin' abeaut o' furnitur, an' a bit o' finger-nail exercise.

Heawever, ther nowt o' that sort as yet, an' things looked promisin'.

We geet eaur pipes, an' an extry neetcap apiece, while we planned

summat for gettin' up th' matrimonial weather in a sort o' good

haytime. Sam thowt takken 'em a havin' their likenesses done

would be as good a thing as owt, for ther' nothin' a woman liked

better than lookin' at her own face, speshly if hoo considered it a

nice un, as what woman doesno'? I fell into his way o' thinkin'

quite natturally; an' it wur agreed on at once. We'd getten'

eaursels in a mess, an' we must fleawnder eaut on't as best we

could. Sam had a bit o' knowledge o' woman nathur as weel as

mysel' I fund.

"Yond parlyment's very quiet," he said, after we'd swallowed

eaur neetcaps, an' ordered two fresh uns knit.

"Th' dur happen fits close, an' winno let th' seaund come

eaut," I said. I could hardly think ut four women could be

t'gether as lung as they'd bin witheaut makkin a noise ut one met

ha' yerd a fielt off; speshly when they'rn debatin' upo "woman's

reets," as no deaut they wur.

"Whoa could have expected sich a drop-on as this?" Sam said,

lookin' slyly up fro' his pipe.

"No' me, theau'rt sure," I said. "If I had expected owt

o' th' sort, I'd sooner ha' had my neck brokken than ha come'n here;

that I would. I wonder heaw they'n fund us eaut, or what

they're doin' here?" for it looked so strange ut we should be dropt

on o' th' plan we wur.

"I con see it straightforrad," Sam said, wi' a knowin' puff

of his pipe. "Th' weather's bin too roogh for 'em to go to New

Brighton, so they'n come'n to Blackpool. This heause wur sure

to be th' fust place my wife would come to, bein' an owd friend o'

th' londlady's."

"Neaw I con see," I said; "I didno' think o' that. It

maks it no better for us, noather."

"Oh, we'se get o'er it," Sam said, quite consolinly.

"Theau's bin in as big a hobble as this mony a time, or else theau's

bin lucky."

"Nay, never!" I said. "I've bin i' one or two queer

scrapes, I'll alleaw, but ther no women consarned in 'em.

Whenever there's a woman i' th' question it's the very Owd Lad

hissel. That theau'll find eaut when theau's had another do or

two o' this sort. An' it's happen noane o'er yet, if we

thinken it is. I've mony a time thowt a cracker had spent

itsel' becose it's bin quiet an' I could see no blaze; but when I've

getten howd on't its gan a fizz an' a frap, an' darted abeaut th'

fowt as briskly as ever. Women are not a bit unlike crackers."

Just then we'rn booath on us started wi' a noise ut coome fro

th' parlour. It wur eaur Sal singin' th' "Jolly Angler."

"Yer thee, by — (summat)" Sam said, jumpin' up, an' smashin'

his pipe on th' table. "If that doesno' cap owd Harry!

Hoo is singin', is not hoo?"

"There's no mistake abeaut yond pipe," I said, feelin' as

fain as if someb'dy had gan me a new pair o' clogs. I con yer

th' owd shakin warble quite plain. There should be a bit o'

difference between singin' an' spittin fire."

"An' heaw the dickens has that bin browt abeaut?" Sam said,

lookin' quite bewildert.

"Nay," I said, "there's no akeuntin' for what a lot o' women

will do when they getten t'gether. I'm noane surprised,

if theau art; not a bit."

"We'st ha' to goo an' join 'em, neaw, at anyrate," Sam said,

jertin across th' reaum wi' a slur; "so come on, owd swell."

"Just let her ribship finish her singin' fust," I said,

feelin' a bit o' respect for th' owd crayther's performance. "Hoo'll

not be above ten minits lunger. Theau should yer her sing 'Th'

Gardener;' that lasts twenty." But 'th owd lass finished off

wi' a flourish, an' then we ventured into th' parlour.

Talk abeaut a jubilee, or th' comin' of a fust babby!

Eh, dear! Nowt could ha' byetten th' finishin' up o' that neet.

Th' women had getten their wine afore 'em, like a board o' guardians

after there's bin a new rate collected; an' it favvort as if no

little on't had bin put o' one side. Eaur Sal's face wur like

a piece o' mahogany; an' th' way ut hoo coome at me, an' threw her

arms reaund my neck, towd its own tale. Sam's wife kept hoidin'

her face in her napkin, bein' young at sich like wark; an' it wur

fun to see heaw o four bonnets had getten writhen abeaut their yeads.

"What a pity," Sam said o' one side to me, "ut drink should

be th' cause o' so mich misery i'th wo'ld, when a sope 'll set

things to reets like this."

"Ay; it's a corker—is nor it?" I said.

"Come, Ab," eaur Sal said, stretchin' hersel' like a

butcher's wife at a merrymeal, "theau'll ha' to let these ladies yer

what theau con do."

Ladies! An heaur before that they'rn ready to

scrat one anothers' e'en eaut; an' neaw they'rn as thick as

cooarters. Thoose widows had seen a bit o' th' wo'ld, an' knew

summat o' what a woman wur made on, or else they couldno' ha'

managed a job o' that sort so readily. I begin to think now ut

feightin', whether between two yorneys in a tap-reaum or two nations

in a fielt (yorneys just th' same) never sattled a difference sin'

Cain won his fust battle wi' their Abel. Hard blows never wur

intended to mak' a wrung reet. But I fund I should ha' to sing

summat, an' as singin's anytime pleasanter than fratchin', I wesht

my organ-pipes eaut wi' a gargle o' red port, an' brasted off wi'—

|

SEEIN' DOUBLE.

A lord on a pony rode by t'other day,

When he spied a fair damsel, and to her did say,

"My fair one, whose pigglings are those in yon sty?"

"They belung to th' owd soo, sir," the girl made reply.

Derry down.

"You're rather sharp-witted," the lord then did say;

"But, by the same rule, who may own you, I pray?"

"My mother," she said, with a blush on her cheek;

"But Jammie o' Nancy's 'll claim me next week."

Derry down.

"Who's Jammie o' Nancy's?" the nobleman said.

"Is he some wealthy squire, or gentleman bred?"

"He's noane a rich squire," the maiden said she,

"But owd Nancy at th' Top lad, an' skens o' one e'e."

Derry down.

"Why should you prefer one that squints?" the lord said.

"Becose one ut looks straight has less use for his yead;

But he that con see o'er two hedges at once,

Con mind two folks' bizness, or else he's a dunce."

Derry down.

"Well answered," the lord said, and straightway rode he;

"That's a hint for my meddling, I plainly can see.

Now, what shall I give you your favour to gain?"

"A seet o' yo'r back," said the maid with disdain.

Derry down.

The week that came next found the couple at church;

They were met by the lord as they entered the porch,

Who promised them there that when twins blest their lot

A good acre of land he would add to their plot.

Derry down.

In a year after that the young couple were blest—

A child in the cradle lay sucking its fist,

When the mother, one day, thus accosted the lord—

"I' that matter o' twins will yo' stick to yo'r word?"

Derry down.

"But I only see one," said the lord with a smile,

And the youngster he took from its cradle the while.

"Yo'r done," said the dame, " 'less yo'r bargain yo'

rue;

Yo' may nobbut see one, but eaur Jammie sees two."

Derry down. |

"Down, down, derry down!" eaur Sal piped eaut, givin' th' chorus

twice o'er as a finisher. "I believe I'm beginnin' a-seein' double

mysel'," hoo said, blinkin' at me with a rowlin' sort of a look. I

con see two Abs. Whether they're booath mine or not I dunno' know. One's a good un, at anyrate, obbut he's too fond o' gooin' to th'

Owd Bell; an' he isno' quite as young as he used to be, moore's the

pity. Bless'em booath! Ladies, bless yo' too! Yo'r a good sort. I

wish I could find a husbant a-piece for yo'. Tidy-iddle-de-come-again; women con dance as well as th' men. Misses Smi'ies,

let's goo;" an' th' owd craythur geet up, very

uncertainly, off her cheear.

"Wheere art' off to, neaw?" I said, catchin' howd on her by th'

elbows, and steadyin' her rowlin' motion.

"Uncle Tom's Cabin," hoo said, puttin' one foout upo' th' fender,

an' lookin' i' th' fire-place, as if hoo'd getten a notion in her

yead ut Uncle Tom's Cabin wur somewheer up th' chimdy.

"I think a journey up Timber-street to Bedford would suit thee

better than gooin' to Uncle Tom's Cabin, at eleven o'clock at neet,"

I said. An' I took her by the shoothers, an' walked her into th'

lobby. A young woman met us wi' a candle, an' said hoo'd see her

ribship safe londed upstairs. Sam's wife bid th' widows good neet,

an' followed; an' it wurno' mony minits afore ther another flittin',

leeavin' Sam an' me th' mesthurs o' th' fielt. As soon as we'd getten by eaursels, Sam nudged me, an' settin' up a dumb crack o'

laafin, said—

"Ab, we'n managed that job bravely. Let's have another neetcap. Cock-a-doodle-do!"

――――♦――――

CHAPTER IV.

AFTER a neet's

rest, brokken neaw an' then by a seaund o', "Bless eaur Ab an' th'

childer!" buzzin' i' my ear, I geet up an' shaked th' dew off my

wings afore anybody else wur stirrin'. It wur a grand mornin',

rayther cool for th' time o' th' year, but as fresh as a rose, an'

sweet like one. I thowt I'd have a bathe while th' beach wur quiet,

for I've my own notions abeaut dacency, an' they're a bit strict,

too. Th' owd rib wur slum'merin' seaundly; so I donned mysel', an'

crept away witheaut her knowin'. Sam Smithies must ha' yerd me; for

he co'ed eaut, as I're gooin deawn th' stairs—

"Wheer art' off to, Ab?"

"I'm gooin' a-seein' if I con find a shell or two for th' childer,"

I said. I didno' want him to know ut I're gooin' a-bathin'. He met

happen be up to some sort o' mischief if he did.

"O reet—away wi thee!" he said; an' I took his advice.

I went deawn to th' beach, an' fund two bathin' chaps, wi' their two

vans, lookin' eaut for th' "early worm." I shopt one on 'em at

once, an' meaunted my road into his machine. I're doft in a snifter,

an' puttin' on sich bathin' gear as they han for men, we set off on eaur journey to th' wayter.

Th' tide were middlin' far eaut, an' ther a nice rowl o' sae. I fund

I should ha' to goo a lung distance afore ther any danger o' bein'

dreawnt, unless I laid mysel' deawn, a thing I wurno' likely to do,

for reeasons yo'n soon larn. Th' mornin' air an' th' wayter t'gether

made me feel a bit chilly at fust, but I'd hopes ut that would goo

away i' time; so I dashed in, an' waded forrad to wheere th' sae wur

deeper, feelin' my road carefully, for fear a shark should have a

snap at me, though I'd never yerd o' sich like animals bein' seen

abeaut Blackpool.

I'd no sooner getten my fust plunge o'er, an' th' wayter eaut

o' my ears, than I see'd th' tother van rowlin' deawn to'ard mine.

I wur to ha' company, after o, it seemed. What surprised me,

an' made me feel rayther nervous, a woman geet eaut o' th' van, and

made a plunge into th' wayter, as if hoo're used to sich like wark.

Hoo'd a red geawn on, an' I thowt by that hoo must be no common

body. After th' fust duckin', hoo struck eaut to'ard me,

takkin strides like a she giant; for to my thinkin' hoo're as big as

one. What age hoo're likely to be I couldno' say, becose hoo'd

her yead an' th' bottom part of her face tee'd up in a white napkin.

I didno' like o' my shop by a good deeal, un I thowt it very wrong

ut women should be alleawed to be so undacent as to come wheer men

are, when there's plenty o' reaum i'th' sae ut they con have to

theirsels. Heawever, I must mak th' best on't, so I waded as

far eaut as I du'st, th' tide bein' low, an' th' greaund flat.

But, as far as I went th' owd besom kept getten' narr me; an' th'

plungin' and rowlin' hoo did i'th' wayter wur summat fair cappin'.

I made a fleaunder i'th' wayter, as if I'd bin a capital

swimmer, settin' my yead to'ard her, like a ship in a good wynt.

I'd flummax her, if I could. That wouldno' do. Hoo

seemed to challenge me to come on, chus what I did. Once I

thowt hoo put her thumb to her nose, for t' show me bacon.

That wur a piece o' unmannerliness I couldno' stond at o, but I

didno' like tellin' her hoo're no lady for t' behave as hoo did.

I're not i' love wi' my sitiwation, I con tell yo; an' I

began to have some misgivins ut it wur done o' purpose. Swim I

couldno', nobbut abeaut three strokes at a twell, or else I'd ha'

gone a hauve a mile furr eaut, sooner than ha' bin thowt I're i'

other folk's road. As it wur, I'd my shoothers just buried, wi'

neaw an' then a wave comin' slap into my meauth, an lappin' reaund

my yead like a weet teawel. Th' owd porpus, I see'd, could

swim like a cork; an' hoo did a sail reaund, sometimes leetin' for a

rest, and droivin' me into fresh territory. If hoo'd nobbut

get a bit furr eaut int' th' sae, I'd heave my anchor an' steer for

t' shore, as I'd getten rayther wakkery abeaut the gills, an' ther a

sprinklin' o' stragglers upo' th' sond, watchin th' fun, as I thowt.

Th' bathin' chap kept sheautin' eaut to me for t' keep at a proper

distance, if I're a gentleman—a thing I'd like to ha' done, if

others would ha' letten me.

As a forlorn hope I'd purtend to dive, wi' my yead set to'ard

the owd dame. I'd mak her believe I could come up within a

yard or so o' wheere hoo wur. But it wur no use; I fund I're

blockaded, an' I're kept dodgin' abeaut for twenty minits or so,

like a duck ut's bein' followed wi' a dog. At last, when I'd

hawve dreawnt mysel' wi' tryin' the experiment, an' when my limbs

wur as numb as if I'd bin lapt in a sno-bo, I spied my opportunity,

an' off I plashed to'ard th' shore as fast as I could paddle mysel'

through th' wayter. Just as I're meauntin' th' ladder o' th'

van someb'dy fro' th' shore sheauted eaut I're gettin' i' the wrung

shop; an' as I're feart a mistake o' that sort met end afore th'

magistrates, I plashed off to th' tother consarn in a dule of a

hurry. Theere I shut mysel' up, an' took my wynt a bit; then I

set-to an' gan my husk a god scrubbin wi' a teawel for t' set my

blood agate a-workin gradely. A mon seein' me get into my

kennel browt the hoss deawn, an' yoked it to the van. Summat

he said beaut me sheautin through a peephole for t' let him know

when I're ready for bein' londed. A very good contrivance, I

thowt; an' so far everythin' looked reet; but when I coome to look

reawnd for my clooas I seed a yeap o' silk or summat piled up in a

corner, an' ut favvort havin' dropt off a peg; an' ther a bundil

lapt up in a newspapper at side on't. I didno' want no

scrubbin' then, for th' seet o' that made me break eawt a-sweeatin'

like a coach hoss, an' set my blood a-tinglin' like a lot o' little

bells. I'd getten into th' wrung box after o.

"Heigh!" I sheauted through th' peephole. "Stop that

hoss; I'm i' th' wrung boose."

"All right, sir. Caum aup!" th' mon said. And

then I felt a jerk, an' yerd th' wheels grindin' amung th' stones,

an' I fund I're bein' drawn up to th' shore in a dule of a pickle.

I sheauted through th' peephole again, but it wur no use; I met as

weel ha sheauted to th' pier.

"I'm i' th' wrung van, I tell yo."

"Caum aup!"

"Let me eaut o' this cote."

"Caum aup!"

It wur no use; as oft as I sheauted for him t' stop, it wur "Caum

aup" to th' hoss, an' things wur' gettin' moore desperate every turn

o' th' wheels. I oppent th' dur an looked eaut. I seed

th' woman wur just climbin' th' steps o' th' tother van.

In another minit or two I should be i' th' honds o' th'

police—that wur sartin. I made a last attempt to be yerd, as

"Sister Ann" did when Blue Beart wur gooin' to shorten his wife by

th' toppin'. I lapt th' silk dress reaund my carcase, an'

climbin' eaut o' th' van dur I made another trial o' my lungs."

"Heigh, bathin'-felly," I sheauted, "back me into th' sae

again. I'm i' th' wrung box."

Th' mon must ha' bin as deeaf as a shopkeeper when th' book's

full, for chus heaw I sheawted th' van kept gooin', till at last I

yerd a "Who-oy," an' felt a jerk.

"Neaw for it!" I said to mysel', when I fund I're drawn up to

th' beach, an' could yer folk talkin'. "If ever theau wur in a

mess, Ab, theau'rt i' one neaw." An' I sit mysel' deawn upo'

th' bundil, an' began my meditations, like Robi'son Crusoe when

he're shipwrecked. Th' owd doxy must be a whacker, I thowt,

for her boots wur two inches lunger than my foout, an' quite of a

monly shape. I shouldno' like to meet her upo' th' promenade,

an' her get to know whoa I wur. Her nails would be i' th' road

o' my face, I felt sure. Just as I're calkilatin' th' exact

minit ut th' dur would be ript oppen, an' my carcase hauled eaut, th'

bathin' chap looked in, an' axt me if I're takkin' up my lodgings

theere. I towd him it wur as likely as not, unless I'd some

sort o' gears to put on different to what I could find. An' I

pointed to th' silk dress ut were hangin' abeaut my shoothers.

He oppent a meauth as wide as a cauve, an' after makkin' a noise

like one, said—

"Yo'r i' th' wrong burth."

"Tell me summat I dunno' know," I said, crabbily. "I

sheauted till one lung gan way for yo' t' stop, but yo' oather

couldno' or wouldno' yer me. What mun be done?"

"I durn know," he said, pokin' his fingers under an oil-case

hat, an' scrattin'. "What made yo' get in?"

"I're gettin' i' th' tother," I said; "but some yorney or

other sheauted I're gooin wrung; so I swapt. It sarves yo'

reet for puttin' th' vans so close t'gether."

"Yo'r under a fine o' forty shillin' if I wus to report yo',"

he said, wi' a very comfortin' grin.

"Report away," I said, gettin' savager; for I're shiverin'

like a beggar in a ginnel. "It's noane o' my faut. I

sheauted when I fund th' mistake eaut, but yo'd getten yor ears full

o' sond or summat, for yo' kept jiggin' on chus what sort of a noise

I made."

"I dirn'd hear yo'," he said.

"Becose yo' wouldno'; that's abeaut it," I said. "But I

reckon it's o as one neaw. I'm in for it, an' I mun get eaut

on't o' some plan."

"The lady's sure to send for a bobby," th' mon said, wi'

another comfortin' grin ut raiched fro' one ear to th' tother.

"Had a fellow locked up tother night for on'y lookin' at her."

"Hoo conno' find me a wur shop than this," I said, "unless

hoo shipwrecks me at once. Conno' some plan be shapt ut we con

swap beaut any moore bother? It's nobbut a mistake when o's

said an' done."

He looked to'ard th' tother van for a minute or so, an' then

he said—

"Signal! Hond me that riggin' eaut; the old girl's

blowin' a gale, I con see."

I honded him th' dress, an' th' bundil, an' th' boots eaut in

a crack, an' towd him for t' square things up as weel as he could,

an' I'd stond a pint for him when I geet eaut o' limbo.

Th' mon set off on his arrand wi' a deautful shake of his

yead ut I didno' relish, an' leeavin' me like a new Adam, sowd up to

th' last rag an' turned eaut o' th' dur. In abeaut ten minutes

he coome back wi' a very comfortin' piece o' news for me. Th'

owd besom wouldno' part wi' my clooas till a policeman were fotcht,

an' summat done for gettin' me eaut o' one prison int' another.

A very quire feelin' coome o'er me, I con tell yo; an' I wondered

heaw th' forty shillin' an' costs would be mustered. Heawever,

summat must be done, an' soon too, or else I should find mysel' i'

th' Blackpool summer-heause; so I said—

"Goo as far as th' Darby Hotel, an' ax for Sammul Smithies.

If he's in tell him heaw I'm fixt, an' ut I should like him to come

deawn."

"All right!" he said, an' off he went.

It looked like a hauve an hour afore th' chap coome back, an'

I're i' deauts as to whether he'd turn up at o. At last I yerd

his shoon maulin' amung th' stones, an' then they a laaf ut I'd yerd

mony a time before. Sam Smithies wur with him, an' I felt as

if th' prison durs wur oppenin'.

"Heaw art' gettin on, owd swell?" Sam said, peepin' into th'

van, as if he'd bin gooin reaund a menagerie.

"I'm ready for a wrostle, if theau con find anybody o' my

weight," I said, as cheerfully as I could under th' circumstances.

"Theaur't come'n to a queer shop for getherin' shells," Sam

said, peevishly.

"Let's ha' noane o' thy allin' " (bantering), I said; "things

are quite bad enoogh."

"Theau'rt in a nice pickle, if theau could nobbut see thysel',"

Sam said, hardly able to howd fro' laafin. "Heaw dost' like

bein' a prisoner?"

"Well, I dunno' like this sort of a prison dress," I said.

"It's rayther too thin for this sort of a summer. It met do

for th' Indies, but hardly suited to Blackpool."

"Here's a change for thee, then." An' he chuckt a

bundil in, wi' my hat an' my shoon, ut made me feel quite a new mon.

"Theau may thank me for this," he said. "If I'd bin away

they'd ha' wheeled thee off to th' lockups just as theau art, th'

van an' o. Theau'll happen mind better next time theau comes

a-bathin'."

"I'se never trust my carcase i' one o' these consarns again,"

I said, "theau may depend on't. If I do they may wheel me into

th' sae, an' bait for sharks wi' me."

"Heawever did t' come to mak this mistake?" Sam said, puttin'

a glass to his e'e, as if he'd bin a magistrate, an' I're his

prisoner.

"It wurno' my doin's at o," I said. "I wanted to have a

quiet duck, an' that's what I bathed so soon this mornin' for.

This mon knows, too, ut I did my best for t' keep eaut o' th' road,

but they wouldno' let me."

"Th' magistrates wouldno' ha' believed that tale, Ab, if

theau'd gone afore 'em," Sam said, with a shake of his noddle.

"I're watchin' thee o th' time, an' should ha' bin an ugly witness

again thee if I hadno' bin a chum o' thine. What'll thy wife

think?"

"I reckon theau'll break thy neck for t' tell her!" I said,

knowin' at the' same time ut he wouldno' lose a minit.

"There'll be no 'casion for me to tell her," Sam said.

"It's gooin' through Blackpool neaw like th' news of a murder."

"Ay, that's it," I said; "hobble number two. It's quite

time I paid a visit to Walmsley Fowt for a change of air. If I

stop here mich longer I'se be i' some mischief I conno' get eaut on

so weel."

"Well, be sharp, an' let's get th' sheautin' o'er," Sam said,

lookin' reaund th' corner o' th' van; "theau's had mony a public

reception, an' this is likely to be one ut'll raise thy hat an inch

taller. We owt to have had a band for't leead up."

"Theau'll do i'stead of a band," I said rayther

savagely. "Theau'rt as fain o' this job as if someb'dy had

laft thee a fortin. I shouldno' wonder if theau's had summat

to do wi' bringin' it abeaut."

"Ay; thoose are th' thanks I get for helpin' thee eaut of a

scrape," Sam said; an' he put on a look as innocent as a newborn

babby. "But on wi' thy duds," he said, "I con forgie thee."

Wi' mich pooin', an' haulin', an' rippin', an' I dar'say

swearin', if th' truth wur towd, I geet inside my clooas once moore,

and made a desperate jump eaut o' th' van. I'stead o' there

bein' a creawd o' folk abeaut, I fund ther nobbut an odd straggler

or two, an' ut didno' seem to know what a grand play had bin acted

upo' th' sond. I felt better satisfied when I see'd that; an'

when Sam towd me he'd made it reet wi' th' owd duchess, an' ut

there'd be no pooin' up afore th' magistrates, I began to tak' my

wynt a bit moore regilar.

"What sort of a crayther does hoo look like?" I axt Sam,

becose he must ha' seen her.

"Hoo's a ripper," he said. An' he held his hont abeaut

a foout o'er his yead. "Hoo taks a boot as big as mine; an I'm

considered to have a big foout."

Natturally enoogh I looked deawn at Sam's feet, and gan a

start, as if someb'dy had prickt me. Then I looked at his

face, an' fro' theere deawn to his feet again, for I'd seen summat

ut had gan my inside a twist. If he wurno' wearin' th' same

boots as I'd seen i' th' bathin' van, they'rn th' twin pair.

Had I bin sowd again? Ay, an' cleean too, for he gan eaut a

crack o' laafin ut met ha' bin yerd fro' one pier to th' tother.

He confessed at once ut it wur him, an' not a woman, ut had put me i'

sich a fluster. He'd followed me fro' th' hotel, takkin with

him one of his wife's dresses, an' her bathin' geawn. Th'

dress he'd hung up i'th' van, for t' leead me to believe it wur a

woman's, and th' bundil I'd sit on wur his own clooas. Booath

bathin' chaps wur in at th' mischief, an' one on 'em, I fund,

wurno quite as deeaf as he portended to be. I knew it wur no

use sayin' nowt. I're fairly sowd, an' it would be fun for th'

Owd Bell for a Month or two. Ther one comfort, heawever—ther

nowt said abeaut it i' Blackpool.

"I consider neaw," Sam said, as we'rn gooin up to th' hotel,

"ut we're as nee straight wi' one another as we con be. Theaws

had th' upper hond o' me ever sin we'rn at th' Exhibition. If

ever theau's th' luck to get another score I'll forgive thee.

Lord, what an object theau looked wi' th' dress o'er thy shoothers;

an' what a noise theau made when theau're sheautin' for th' van to

stop! I're as nee being dreawnt as a toucher wi' laafin' at

thee. 'Heigh, stop that hoss; stop that hoss! I'm i'th

wrung boose; I'm i' th' wrung boose.'"

"Say nowt no moore abeawt it," I said. "I'll give in ut

I'm fairly byetten. Let's goo an' ha' some breakfast.

Theau conno' lick me at that."

――――♦――――

CHAPTER V.

MY bathin'

adventure, I fund, had one good effect: if it had made me look like

a foo', it had browt sich sunshoine i'th' Darby Hotel as had happen

never bin seen theere afore.

Th' women had just come'n deawn th' stairs when Sam Smithies

an' me had getten back fro' th' beach, an' wur lookin' eaut for us

at th' bottom o'th' street, becose th' breakfast wur ready, an' th'

Blackpool air had made 'em a bit sharp-set. Th' owd rib

complained of a smatterin' o' yead-wartch, ut hoo shows wur browt on

through havin' her bonnet-strengs teed too tight on ackeawnt o'th'

wynt. It couldno' be th' wine hoo'd had, hoo're sure. I

didno' feel quite so sartin mysel' ut th' wine had had nowt to do wi'

th' mischief; but as ther peeace i'th' camp, I'd let it pass for th'

bonnet-strengs. Sam's wife looked like a wench ut had bin

catcht coortin th' first time, an' couldno' forshawm to face her

neighbours up th' mornin' after. Hoo'd plenty o' colour in her

face ut hadno' bin caused by noather sae wynt nor Blackpool sun.

Sam said hoo're like a fleawer ut had gone to bed a lily an' getten

up a pink; a remark ut geet him a nice slap i'th' face for makkin'

it. Th' widows looked as if they'd never ailt nowt i' their

lives, an' never would ail nowt. They'd a bit o' fresh bloom

on their cheeks ut I hadno' seen afore, an' ut took a year or two

off their calendar; an' th' way they brushed abeaut, an' looked

after th' breakfast showed they knew moore o' what they co'en

life than con be seen i Walmsley Fowt.

There met never ha' bin a row th' neet afore, th' women looked so

gradely wi' one another. It wur "Missis This" an' "Missis That," an'

what their ailments had bin through life, as if they'd bin owd

friends, parted for a time, an' browt t'gether again by th'

strangest o' accidents. It wur far better, I thowt, than if we'd bin

o' one family, come to Blackpool t'gether, for t' spend a hum-a-drum

week or so i' green spectekles an' yallow shoon; then goo whoam wi'

th' satisfaction o' havin' bathed once every day, ridden donkeys

twice, an' gan everybody abeaut us as much trouble as could be made;

as if that wur th' greatest pleasure ut could be had at th'

sae-side. But for o that, it wur an experiment ut I shouldno' like

to try o'er again, an' ut happen wouldno' come off reet once eaut of

a hundert trials.

"Get it o'er afore theau chokes thysel'," I said to Sam as we sat

deawn to breakfast. I could see his crop wur swellin' eaut, like

blowin' a foot-bo up, wi' summat he had to let eaut. "Theau'll ha'

no reaum for thy coffee if theau doesno' use thy tongue for a

stomach-pump, an' empty eaut."

Wi' that he set up a crack o' laaffin' ut seaunded moore like

cowghfin, an' ut made his wife jump up an' slap him on th' back, as

if hoo thowt he'd getten a crust in his throat an' wur chokin'. When

he'd come reaund, and had two bits ov after-claps, he set to an'

towd th' skit he'd had wi' me o'er bathin'. I thowt eaur Sal wur

shapin for bein' vexed at th' fust, as hoo gan me a shot fro' her

e'en ut had mony a time bin th' beginnin ov a storm; but when Sam

sheauted—"Heigh, bathin felly, back me into th' sae again, I'm i'th'

wrong box"—an' th' tother women gan eaut a skreeak ut made 'em

twitch up their stays as if they'rn brastin, th' owd lass unscrewed

her index, an' speauted her coffee reet into th' fireplace. I laafed

too as weel as I could; but a deeal on't went again th' grain, an'

we'd summat like a hauve-a-dozen merry peeals reaund th' table, ut

caused folk ut wur passin' th' hotel to stop an' look up at th'

window, an' as good as ax one another heaw mich it wur to go in. Everybody's coffee went cowd for th' want o' swallowin'; an' as

hungry as no deaut we wur, eawr jaws had summat else to do than

grind buttercakes.

"Theau great yorney!" th' owd un said as soon as hoo'd getten as

mich wynt back as would mak' three words. "I wonder what sort of a foo' they're mak' on thee next. Theau'll ha' to wear dadins

(leading-strings) yet, or else be led by th' hont. I'd ha' gan

summat for t' ha' had thee portergrapht when theau'd th' dress lapt reaund thy carcase. Thy yure ud want some chep beef, I know. There

will be one good thing come eaut on't, at any rate; theau darno' go

to th' Owd Bell yet awhile. Theau'rt sure to yer abeaut it if t'

does."

"What would anybody else ha' done if they'd bin i'th' same

predickyment?" I said, feelin' a bit nettled at th' fun they'rn

makkin on me.

"Done, sure!" hoo humphed. "Dost' think any woman would ha' carried

on as Sam did?"

"Well, I do think," I said, "ut when folk are away fro' whoam, men

are th' modester o'th' two. What dun yo' think?" an' I turned to th'

widows.

One on 'em nodded, as good as to say hoo thowt as I thowt, an' th'

other said—

"You're right, Mister Fletcher." (I wonder heaw hoo getten t' know

my name.) "I know from my own experience that what you say is quite

true, though I speak it to the shame of my own sex."

I'd won that point fairly.

An' neaw it coome to heaw must we spend th' day, wheere must we goo,

an' sich like; things ut I expected Sam an' me would ha' t' sattle.

I fund, heawever, ut th' women had laid th' plans eaut afore we'd a

chance o' namin' owt o'th' sort; an' when Sam said a walk as far as

"Raikes Ho" would be a nice eaut, they gan us to understood they

wouldno' shank it a yard nowheere: they'd have a carriage if they

nobbut went to th' bottom o'th' street. Heaw everybody tries to be

grand, I thowt.

"A carriage will only hold four," Sam said, lookin' reaund an'

purtendin' to keaunt th' company, as if he didno' know at th' same

time ut ther six on us.

"We nobbut wanten one ut'll howd four," eawr Sal said, wi' a fause

sort of a grin.

"But we can't do less than ask these ladies," Sam said, lookin' at

th' widows.

"Th' ladies han axt us; neaw then," th' owd rib said, trumpin' Sam's

king. Then ther a titterin' went reawnd th' table, an' some meeanin'

looks wur swapt amung th' women.

"I may as well tell you, dear," Sam's wife said—(eaur Sal nudged me

an' whisperd, "Yer thee, Ab, hoo co'es him 'dear': I'll

co thee chucky.")—"I may as well tell you, dear, that the ladies have asked

us to have a drive with them to the Strawberry Gardens, and you can

go where you please; which, I dare say, is an arrangement you won't

object to."

Sam turned up his e'en an' soiked.

"Now you won't, dear, will you now? As you've been so very attentive

since we came ("Humph!" eaur Sal said), we've agreed to a—a—"

"To poo their collars off, an' let 'em run abeawt th' fowt," th' owd

un said, seein' ut her better-larnt friend wur fast for a word or

two.

"'K you, Missis Fletcher," Sam's wife said, with a bow; "what a

happy way you have of expressing yourself! How sorry the gentlemen

look, don't they?" An' hoo geet howd ov her lord's bears an' poo'd

it.

"I shall break my heart, love," Sam said, rommin' a hontful of his

knuckles into his e'en, as a choilt does when it's skrikin' for a

buttercake.

"It's bigger odds on thee breakin' thy neck," I said, thinkin' I'd

just put him one in while I'd a chance.

"There'll be moore doancin' than skrikin', will there no', chucky?" eaur Sal said; an' hoo gan me a pluck at my left whisker ut made me

wince.

"Reet, owd ticket!" I said; an expression ut made th' "ladies" oppen

their e'en, as if they hadno' bin used to sich sweet an' lovin'

words.

After a bit moore o' this pleasant croodlin—a thing ut seemed to mak'

th' widows wish their own husbants wur theere—we agreed, Sam an' me,

ut we'd let th' women do their own for an heaur or two; but they

mustno' expect ut sich a great sacrifice o' th' feelins o' two lovin'

husbants could be made every day. We happen met see through it this

time wi' a bit o' philosophisin', but th' consequences of a second

experiment could noather be weighed nor keaunted. But life wur beset

wi' trials, Sam said; an' partin wur sich sweet sorrow; an'—fare

thee well, an' if for ever, still for ever fare thee well!

"Let's goo deawn th' stairs an' have a bitter, Ab. Tie a stone to th'

neck o' grief, an' drown it in the bowl."

"I'm ready for doin' a deed o' that sort any minit," I said; for I

could hardly howd fro' yawpin eawt.

"Lead a-on, then!" Sam said, gettin' up fro' th' table, an' brushin'

th' crumbs off his waistcoat. "The time will come!