|

THE SLAVE-HOLDERS' WAR.

――♦――

THE following address was delivered in the ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE

Town Hall, on Monday, November 16, 1863, by ERNEST JONES,

Esq., and has been printed by the Union and Emancipation Committee of

Ashton, at the desire of the friends of freedom in that town, and of those

in Halifax, Huddersfield, Manchester, and many other places.

The meeting was most numerously attended, the large hall

being densely crowded in every part.

HUGH MASON, Esq.,

occupied the chair—and during the addresses he and Mr. Ernest Jones.

delivered, both those gentlemen were most enthusiastically applauded.

THE CHAIRMAN, on

coming forward, remarked that in that crowded meeting, and in that heated

atmosphere, he was sure they would agree with him that it was important

for all of them, for the comfort of the lecturer, and for the comfort of

themselves, that they should maintain good order. He knew that in making

that appeal, he was making an appeal to men who, on former occasions, when

they had assembled to discuss a great and important subject, had been

quite equal to the occasion. He was called upon that night to take the

chair on an occasion when the placard was headed "The Slave-holders' War." He was also called upon to preside when the lecturer was his learnèd

friend Mr. Ernest Jones—a name which was not strange to the working people

of Lancashire. There was at his right hand a man who was a most

accomplished scholar—who was most sound as a politician, and who was

second to none in this country as a philanthropist. The name of Ernest

Jones had been uttered in times past with affection and reverence by the

working people of Lancashire. Ernest Jones, in times past, was recognised

as one of the great leaders of the working people of England when they

were struggling for political rights—and therefore he (the chairman) felt

proud that night to stand by his side, and to be identified with a man who

had come forward to uphold a cause which, in his opinion, was one of the

holiest which could be pleaded in this country or in any other. This was

the first time in the course of a war in the United States of America

which had now been carried on for upwards of two years, that he had taken

the chair on such an occasion as the present. He was not a member of the

Southern Club. He was not a member of the Union and Emancipation Society. He wished to be distinctly understood. He was one of the earliest members

of the Emancipation Society of London. He was one of its first

subscribers, and he had the honour to be one of its vice-presidents, and

he continued a member of the Emancipation Society to the present day; but

he had not felt it to be his duty, and he had not felt it to be sound

policy to identify himself with the society termed the Union and

Emancipation Society, though that society included in its ranks a

considerable number of men with whom he had the pleasure to work on many

important subjects. He must tell them that he was a strong admirer and an

ardent advocate of that policy of neutrality which had characterised the

proceedings of the British cabinet and the British parliament; and it was

because he wished that policy to be continued, and because he saw there

was an attempt made in various parts of this country to influence the

government to departs from that policy of neutrality, that he had felt it

his duty to come forward, and to take the opportunity of saying that the

policy of neutrality which had characterised the government of this

country was one which he most ardently hoped would be continued; and he

hoped, and believed, and felt convinced that the voice of the people, and

especially the voice of the people of Lancashire, would warmly support the

policy of neutrality of the British government. With regard to the

question of union, his own individual opinion was that it was secondary to

the question of the emancipation of the slaves. If they asked him what his

individual opinion was with regard to the union being maintained, he did

not hesitate to tell them frankly and after the fullest consideration,

that in his humble opinion it would be a calamity to civilisation, and it

would be a calamity to religion, if that hitherto great and united

republic should be split into fragments. But with regard to the opinion of

the people of America on the question of the union, he would say that it

was entirely in the hands of the people of America to settle; and that it

was not a question for us to entertain in any active way either on one

side or the other. They had heard it stated in various parts of the

country—and it had been emphatically told to the cotton operatives of

Lancashire—that so long as the war in America continued, so long would

the distress prevail in the manufacturing districts. Now, he claimed to

have an opinion upon that subject as well as some other people, and he

declared it to be his opinion, at all events—and he had given no little

attention to the matter—that whether the war in America continued or not,

the question of distress in the manufacturing districts, as connected with

an imperfect and insufficient supply of cotton, was a question altogether

independent of that war; and he would tell them, as a purchaser and a

consumer of cotton, that he had taken a course—and he believed it had been

the right course—that in all his calculations, and in all his actions as a

buyer of cotton and as a seller of yarn, the question of the war had not

exercised the slightest influence whatever upon his conduct. He had had

the opinion from the first, that come what would as regarded secession, or

as regarded re-union, the emancipation of the black was an accomplished

fact, and that for a time at least, and for years to come, with the great

staple industry of that country disorganised, the production of cotton in

America would be reduced comparatively to a nonentity; and he believed it

would be, in the end, one of the happiest things that ever came to the

cotton trade of Lancashire that it had been set free from dependence upon

a supply of slave-grown cotton. With respect to the continuance of the

distress, he would tell them that he had seen figures that day reported in

the Central Relief Committee from the highest authorities that could be

found in Lancashire, that the distress in the country was considerably

diminishing, and had been immensely diminished within the last nine

months—that whereas in January last the pauperism—and he did not use that

word in an offensive sense, but he used it as it was used

colloquially—that whereas nine months ago the pauperism of the cotton

districts was 25 per cent of the population, the pauperism of these

districts was now only 9 per cent. of the population. And if the distress

had diminished to that extent during the continuance of the war, it was a

groundless and baseless statement for any man to get up and say that so

long as the American war continued the distress in the cotton districts of

Lancashire would also continue. He had no doubt whatever that in a time

before very long, they would have the spindles and looms of Lancashire

working as actively as ever they did work, with free-grown cotton,

irrespective of the slave-grown cotton of the Southern States of America. Now, with respect to the emancipation of the slaves, he found some people

getting up and stating that they were for the emancipation of the negro. And wherever they went, they found that though there were many people

strongly in favour of the success of the Southerners they were at the same

time friends to the freedom of the black. But they heard the statement made

from time to time that it would be the worst calamity that could happen to

the blacks if they were to be emancipated before they were Christianised.—

Now, he demurred entirely to the blacks, in this country at all events,

being treated as goods and chattels. The blacks—the men to whom God had

given a never-dying soul—he demurred to the statement that these men were

not to be consulted as to whether they were fit or not for emancipation. "But," says somebody, "we will very gladly give them emancipation when

they have been Christianised." Were they not Christianised? Perhaps not. And whose fault was it that they were not Christianised? Who had kept from

them the Bible? He had the pleasure of having in his family five little

children, and he was quite sure that he was addressing at that moment not

only fathers, but mothers of families in Ashton-under-Lyne, and he would

say to them, if they brought up their children in ignorance of

Christianity, in ignorance of education, and with an utter disregard to

all the attainments and ornaments of life, were their children to be

blamed and reproached for the faults of their parent? So he would say with

reference to those people who claimed to have the control of the black

man. Should the black man, who was the goods and the chattels of certain

individuals in the Southern States of America, be reproached because his

master had kept him in ignorance? But were they not Christianised? What

said the Confederate clergy of America? He would read to them an extract

from an extraordinary document, signed by doctors of divinity, and masters

of art, and almost all the Confederate clergy in the Southern States; and

let those men be the judges upon this question. It was said in this

country that the blacks were not Christianised. Hear what the

Confederate clergy of America said as to the blacks:―

"Most of us have grown up from childhood among the slaves. All of us have

preached to and taught them the word of life, have administered to them

the ordinances of the

Christian church, and sincerely love them as souls for whom Christ died. We go among them freely, we know them in health and in sickness, in labour

and in rest, from

infancy to old age. There are hundreds of thousands, both of white men and

coloured, who are not strangers to the blood that bought them."

|

|

|

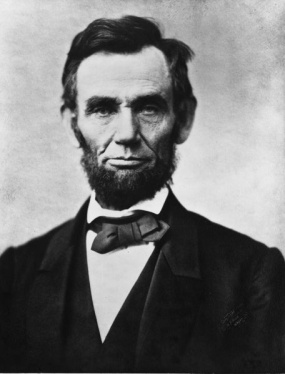

Abraham Lincoln (1809-65),

sixteenth President of the United States. |

In opposition to that, men stood up there and elsewhere to assert that the

blacks were not Christianised. He, however, had quoted the recorded words

of the clergy of the

Confederate States of America. They had heard it stated that the blacks in

the South were much better treated than the blacks in the North. That had

been said a thousand

times. Then, he would ask: How was it that the blacks in the North who were

so badly treated, never ran away to the slaveholder of the South, but the

blacks of the South were

continually attempting to run away to the more oppressed region of the

North? Hence the fugitive slave law. Now, they had been told that the

colonies of America were once

in allegiance to this country—that those colonies seceded—therefore the

Southern States had a right to secede from the union. There was no doubt

that the colonies of

America did secede from the mother country of Great Britain. The colonists

appealed to the sword, and the sword was the arbiter of their destinies.

The colonists of America,

numbering short of four millions of people, on their own ground, and with

a good cause vanquished the disciplined hosts of Great Britain. They won

their freedom, and they

had maintained it ever since. Then, he would say, by parity of reasoning,

that as the Southern States of America had appealed to the sword, let the

sword decide.—As the

inhabitants of the Southern States of America had waged war, or had

rebelled against their allegiance to the government of the country, let

them abide by the conditions which

they themselves had adopted, but let us in this country by all means keep

aloof. If the Southern people of America could conquer their independence,

let them have their

independence; but if the Southern people of America could not conquer

their independence, let them submit to the conditions to which they had

appealed. But this had been

termed a war; he would rather say it was a rebellion. Most assuredly it

was a rebellion of the minority against the majority. Most assuredly it

was the attempt to establish a

new government against the government already in existence; and if the

Southern States of America felt it to be their interest and duty to

secede, why did they not take the

occasion when they had a slave-holding president, and a slaveholding

majority in the senate? How was it that so long as they were in the

majority, so long as their president

was a slaveholding president—as nearly every president had been until the

time of Abraham Lincoln—so long as they had a majority in the senate and

in the congress, so

long as they not only had a vote—white man in the South against white man

in the North, but even the people that were termed goods and chattels were

counted also as

votes for the southern people, every five slaves counting three votes—so

long they appeared to be content with the union, but when the Abolition

party became so strong as to

influence the return of an abolitionist president, then, and then only did

the southern people think it right to secede. But some people say, "Have

they not a right to secede?

Does not the constitution provide for it? Are they not sovereign states,

with sovereign rights?" Why, then, did they not appeal to the

constitution for secession? How was it they fired the first shot and drew

the first sword before making an appeal

to the constitution? And it was only when they had been worsted on the

field of battle—it was only when the circle in which they moved had

gradually been circumscribed

smaller and smaller—it was only when their fortunes were becoming

adverse—it was only when they had given up all hopes of recognition from

Great Britain, and all hopes of

intervention from France—then and then only did they appeal to the

sympathies and to the humanity of the people of Europe. The time, however,

had gone by when the

southern people, with any grounds of reason, could make such an appeal. God grant that this devastating war might shortly be brought to a close. There was not a man in this

room—not a man in the country—who did not bewail the devastation, and the

misery, and the orphanage, and the loss of life caused by this sad and

desolating war. But

there was a great principle at stake when we were appealed to. We said to

the southern people, "Do you intend to perpetuate slavery as the corner

stone of your new

constitution?" "Well," say some people, "we believe that if the

Southerners were made independent, slavery would be the sooner abolished." He could only say that this was a

very strange mode of reasoning. He knew that in the Northern States of

America there was an intelligent, and an active and enlightened, and a

greatly increasing party of

Abolitionists; but he had yet to learn that in the Southern States there

was an Abolitionist party, however small. Tell him the man in the Southern

States of America who was

for promoting the abolition of slavery. What said Jefferson Davis, the

so-called President of the Southern States? Listen to his words before the

time of secession, in the

senate of the United States of America, in December, 1860.

"The belief existing in the northern mind that negroes are, under our

government, entitled to political equality with white men, must be

dispelled, and northern men and northern

states must cease to disturb our domestic tranquillity, or assail our

rights of property, and so impair our national interests, or a dissolution

of the union must be inevitable."

These were the words of Jefferson Davis; very frank, and clear, and

distinct; there was no mistake about them. And what said Vice-President

Stevens at the same time? He

said,

"Our new government is founded upon—its foundations are laid—its corner

stone rests upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white

man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. Thus our new government is the first in the history of the world, (God

grant it might be the last)—based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth. It is upon

this our social fabrics is firmly planted, and I cannot permit myself to

doubt the ultimate success of the

full recognition of this principle throughout the civilised and

enlightened world. This stone"—listen to the blasphemous expression—"this

stone, which was rejected by the first

builders, has become the chief stone of the corner of our new edifice. It

is the Lord's doing, and marvellous in our eyes."

|

|

|

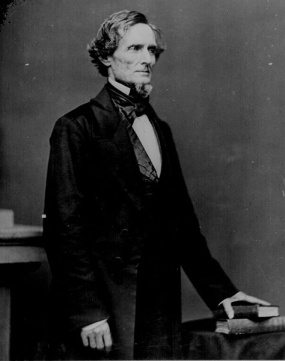

Jefferson Davis (1808-89),

President of the Confederate States, 1861-5. |

Such was the language of Mr. Vice-President Stevens. Now, it was

impossible to have been an indifferent spectator of the public action, and

an indifferent listener to the public

opinion of our

own country upon this great question, and he found that day, as he had

found on former occasions, that the men who battled for free trade in

corn, who battled for free trade in

knowledge, who battled to remove the political disabilities, and the civil

and religious disabilities of the people of this country—he found they

were the self-same men who were

battling in behalf of the emancipation of the slave. He also found what he did

not find on a former occasion. He had no hesitation in saying, that the

great mass of the intellect of this country was in favour of the

emancipation of the slaves, and against

the rebellion of the South. He was aware that he could point to individuals

whom he regretted to see identifying themselves with a cause which, in

his humble opinion,

was an unjust one; but, in the main, the intellect of this country, the

great orators of this country, were in favour of the slave being

emancipated, and against the success of

the rebellion of the South; and he could not doubt that, sustained by the

voice of the people of England, the efforts of those men to whom he had

alluded, battling as they were

doing in the public journals and upon the public platforms—he had no doubt

whatever of the ultimate success of the cause they had espoused.

He had now great pleasure in introducing the lecturer.

ERNEST JONES, Esq., then spoke

as follows:—

THE important subject submitted to our consideration appears to me to

divide itself naturally under three heads,—1st, The origin and object of

the war; 2nd, The right of the

Confederate States to secede; 3rd, The probable results of the struggle to

North America and to ourselves, and our own duty under the circumstances. In discussing this

matter, I purpose giving you, not my own opinions merely, but the

declarations of the South's own lips, and facts which will be accepted as

such on all hands. I will bring the

South itself into this hall, let it plead its own cause, and you shall be

its judges.

1. THE ORIGIN AND OBJECT OF THE

WAR.

That you may the better understand the origin and object of the war, I

must remind you of the nature of the struggle that had been progressing

for a long time in the United

States.

In the North, an abolition party had sprung into existence, and from small

beginnings gradually obtained great strength and influence. Its object

was, the extinction of slavery

throughout the Union. The South, on the contrary, was seeking to increase

its power, and for this purpose, to extend the institution of domestic

slavery. The means by which this was to be accomplished were as

follows:—

The entire Union consisted of states and territories, the territories

being tracts of land that had not yet attained a population sufficient to

enable them to be admitted to the

sisterhood of states. As soon as the requisite population (124,000) was

then obtained, a territory might claim to become a state. The question

arose: should the territories

thus created into states, be slave or free? The South contended for the

formers, because every state sends two Senators to Congress, irrespective

of population; and each

new slave state would thus give the South two additional votes, to swell

its majority above the North. In 1850, the admission of California as a

free state, endangered Southern supremacy, and from this moment the

struggle assumed a peculiar intensity. It was the desire for the

creation of new slave states that caused the South to attempt the re-opening of the slave trade, for which it made the most strenuous efforts.

If the new territories could be filled with slaves, the requisite

population might be attained for the

formation of new states on the basis of slavery. Therefore James Williams,

U.S. minister to Turkey of a Southern Executive, declared in his "South

Vindicated," that

"Slavery demands new territories, which territories would be cheaply

earned by war."

Therefore the Hon. L. W. Spratt, of South Carolina, said:

"The revival of the slave trade will give political power to the South—imported slaves will give increase of representation to the national

legislature—more slaves will give us

more states, and it is therefore within the power of the untutored savages

we bring from Africa to restore to the South the influence she has lost by

the suppression of the slave

trade."

Therefore Vice-President Stevens said in 1857:

"We can divide Texas into five slave states, and it is plain that, unless

the number of the African stock be increased we have not the population

and might as well abandon the

race with our brothers of the North in the colonisation of the

territories."

Therefore Governor Adams, of South Carolina, in 1857, in his address

denounced the prohibition against trading in slavery, and said it

interfered with the essential interests of

the South.

Therefore the "Chief Press" of South Carolina said:—

"We propose, as a leading principle of southern policy, to re-open and

legitimise the slave trade."

In 1858, the convention at Baltimore openly discussed the re-opening of

this trade. The convention of 1859, held at Vicksburg, voted by a large

majority publicly to restore the

African slave trade in defiance of law. An African Labour Supply

Association was formed, under the presidency of Mr. De Bow, of the "Southern Review;" the State of Georgia

offered a premium of 25 dollars for the best specimen of a live African

imported within 12 months; Louisiana propounded a kindred policy;

Alabama formed a league of

United Southerners to re-open the prohibited trade, and the same year

1859, Arkansas State Legislature voted such re-opening by a large majority.

It is true that since the secession the Confederates disclaim the

importation of more negroes from Africa, but the reasons for this are

manifest enough: any unlimited increase

of slave population would be dangerous in an empire whose area is

circumscribed—the disproportion between white and black must not be too

apparent. It was proposed in

Ancient Rome to give a distinctive dress to the servile population. "Beware!" said a veteran statesman, "lest they should see how numerous

they are!" Again, the slave-holders know that a large importation of negroes would lower the price of

slaves, and depreciate their "property," and the wily monopolists thus

keep up the value of their

chattels. But while the struggle was one of votes between the North and

South, then the slave-trade was a stepping stone to power, and no means

were too horrible to be

employed. For this the South plunged the Union into the Mexican war,—for

this the Texas annexation,—for this the irruption of the "border

ruffians,"—for this the Cuban raids

and the filibustering of Walker. As soon as the Confederate States should

be independent, and have room to expand, so soon the slave-trade would

once more become a

leading object.

The struggle therefore virtually was:—Shall the new territories be slave

states or free? Shall the curse of slavery expand without a limit? Shall

the freedom of the Northern

States themselves be crushed before the ever growing colossus of the

South, or shall every new state that rises on the continent of America be

baptised in the light of liberty,

and help to drive the night of slavery from the South itself?

To meet this issue the republican platforms of Fremont and Lincoln were

constructed. I will give three of the principal clauses from the

latter:—

§ 7. The new dogma that the constitution, by its own force, carries slavery into any or all the territories, is a dangerous heresy.

§ 8. The normal condition of all the territories of the U S is freedom. As

our republican fathers, when they abolished slavery in all our national

territories ordained that "no

person should be depraved of life liberty, or property, without due course

of law," it becomes our duty to maintain this principle inviolate; and we

deny the authority of

Congress, of the territorial legislatures, or of individuals, to give

existence to slavery in any territory of the United States.

§ 9. That we brand the recent re-opening of the African slave-trade under

cover of our national flag, aided by perversions of judicial power, as a

crime against humanity, and a

burning shame to our country and our age; and we call on Congress to take

prompt and efficient measures for the total and final suppression of that

execrable traffic.

Having now endeavoured to shew you the exact nature of the struggle

between North and South, let us see what is said of it by the South

itself. Some gentlemen here tell you

that the Confederates do not urge the war for slavery, but for free-trade,

for altered tariffs, or for independence. Surely, the leaders of the

Southern Government, the Southern

Senates, Presidents, Conventions, pulpit, press, and platform, know the

South's own meaning better than a few amateur politicians here in England,

3000 miles removed

from the scene of conflict! I'll take the word of the South in preference

to theirs. Then listen to its utterance: what does it say before the

sword is drawn?

In 1856, when the contest was between the republican abolitionist Fremont,

and the pro-slavery democrat Buchanan, the Richmond Enquirer (which may be

called the Moniteur of the South) wrote thus:—

"If Fremont is elected, the Union will not last an hour after Pierce's

(the then President's) term of office expires."

Preston Brooks, who represented South Carolina, and

assaulted that eminent man, Sumner, in the Congress House, said in the

same year:—

"The only mode available for meeting it [the issue between slavery and

freedom] is just to tear the constitution of the United States, [thus

admitting that the constitution did not

provide for slavery] trample it under foot and form a Southern

Confederacy, every state of which shall be a slave-holding state."

Jefferson Davis, the Confederate President, spoke thus at Jackson,

Mississippi, in 1858:

"If an abolitionist be chosen President, you will have to consider whether

you will permit the government to pass into the hands of your enemies. In

that event, in such manner

as should be most expedient, I should deem it your duty to provide for

your safety outside the union "

Buchanan, the Southern President, in his message of December 3rd, 1860,

proclaimed that:

"The long-continued and intemperate interference of the Northern people

with the question of slavery in the Southern States, has at length

produced its natural effects. The

immediate peril arises from the incessant and violent agitation of the

slavery question throughout the North for the last quarter of a century,

which has at length produced its

malign influence on the slaves, and inspired them with vague notions of

freedom."

Iverson, representative of Georgia, explained that the rebellion was made

"To avoid universal emancipation by the federal government, and to obtain

nothing short of congressional protection to slavery in the territories."

Benjamin, representative of Louisiana, observed:

"We are prepared to await the issue that slaves are property and entitled

to the protection of the government in the territories."

Toombs, representative of Georgia, was

"Determined to fight for the protection of slave property in the

territories," and exclaimed that "Georgia was on the war path."

Chingman, representative for North Carolina, said

"The issue which North Carolina and Kentucky have to determine, is,

whether there shall be a manly resistance now, or whether our states shall

become free negro

communities."

Clay, representing Alabama, declared

"The Republican platform is a declaration of war, for it asserts that our

negroes are entitled to liberty and equality with white men. Must we live

by choice or compulsion under

those who present us with the alternative of an irrepressible conflict in

defence of our firesides, or the freedom of our slaves, and their

admission to social equality ?"

Wigfall, on behalf of Texas, maintained that

"Man has a right to property in man, and we say our slaves are our

properly."

Then, to the North he made the following offer:—

"If you wish to settle this matter, declare that slaves are property and,

like other property, entitled to be protected in every quarter of the

globe. Say this, and the difficulty is

settled."

These were the utterances of the South,—that was what its representatives

said before the sword was drawn—thus they heralded the conflict,—thus they

announced its

cause. Shall I believe them, or the gentlemen here, who say that the very

leaders of the movement uttered falsehoods, when they stated for what the

movement was

commenced?

But they did not merely tell us for what they would draw the sword,—they

also said on what terms they would leave it in the scabbard. The

CRITTENDEN COMPROMISE was

offered. The following were the terms of adjustment it proposed:—

1. That by amendment of the constitution, [thus admitting the constitution

did not provide for slavery, but required to be amended to permits it]

Slavery should be allowed in all territories south of latitude 36°

30'!

2. That Congress should have no power to abolish slavery in the States

permitting it.

3. That slavery should be sanctioned in the district of Columbia, while it

existed in Virginia and Maryland, and that the officers of Government and

members of Congress should not be prohibited from bringing their slaves

there, and holding them there as such.

4. That Congress should have no power to hinder the transportation of

slaves from state to state.

5. That Congress should have full power to pay the owners of fugitive

slaves their full value, where the national officer was prevented from

arresting the fugitive.

6. That Congress should NEVER have the power of interfering with slavery

in the States where it was then permitted.

7. That the right to have property in man should be legal not only in the

territories then in possession, but in all territories to be thereafter

acquired.

|

|

|

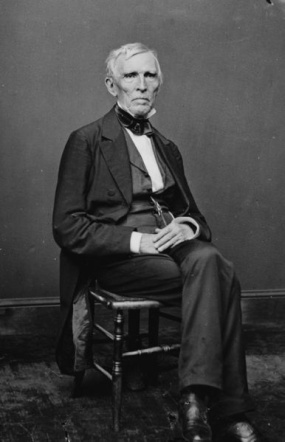

John Jordan Crittenden (1786 –1863),

American statesman from Kentucky. |

But the evidence does not stop here. Not merely has the South told us for

what it was about to draw the sword, not only has it stated on what terms

it would leave that sword

indrawn, but, when waving it in its red right hand, it has issued the

ultimatum, the last condition on which it would restore it to the

scabbard. The following is JEFFERSON

DAVIS'S ULTIMATUM to the Congress of the United States:—

"That it shall be resolved by amendment of the Constitution [again that

word "amendment"] that property in slaves, recognised as such by the

local law of any state, shall

stand on the same footing in all CONSTITUTIONAL AND FEDERAL relations as

any other property so recognised, and, like other property, not be subject

to be divested or

impaired by the local law of any other State, either in escape thereto, or

transit, or sojourn of the owner therein, and, in no case whatever, shall

such property be subject to be

divested or impaired by any legislative act of the United States, or any

of the territories thereof."

Nay! more than this. Mr. Cobden has informed us that

"Whilst Congress was sitting, and when the country was in the agony of

suspense, fearing the impending rupture, congress appointed a committee of

their body, comprising

thirty-three members, being one representative from every state then in

the Union. That Committee, called the Committee of Thirty-three, sat from

December 14th, 1860, to

Januarys 14th, 1861. They where instructed by congress to inquire into

the perilous state of the Union, and try to devise some means by which the

catastrophe of a

secession could be averted. They issued a report of their proceedings which

contains 43 pages.

"The members from the Southern States, the representatives of the Slave

States, were invited by the representatives of the Free States to state

candidly and frankly what

were the terms they required in order that they might continue peaceably

in the Union. In every page you see their propositions brought forward, and

from beginning to end

there is not one syllable said about tariff or taxation. From the

beginning to end there is not a grievance alleged but that which was

connected with the maintenance of slavery.

There are propositions calling on the North to give increased security for

the maintenance of that institution; they are invited to extend the area

of slavery, to make laws by

which fugitive slaves might be given up; they are pressed to make

treaties with foreign powers by which foreign powers shall give up

fugitive slaves but, from beginning to

end, no grievance is mentioned except connected with slavery,—it is slavery, slavery, slavery, from the beginning to the end "

But the tide of evidence flows onward still. The leading confederate

states published formal "Secession Ordinances," in which they set forth

the causes that, as they

maintained, justified their separation. What did the states themselves say

was the cause of their secession?

SOUTH CAROLINA issued its ordinance on the 20th of December, 1860, after

Lincoln's election, but before his inauguration, so eager was it to secede. This ordinance gives

the following reasons as the cause of South Carolina's secession:—

That the fugitive slaves had not been recovered from the free states. That

the slave hunter had not been assisted in re-capturing the slaves.

That the free states had not caused their officers to become

slave-catchers in pursuance of the fugitive slave law.

That the right of property in man had been denounced as sinful.

That societies for teaching abolition principles had been openly allowed

for twenty-five years.

That by Lincoln's election this anti-slavery agitation had received the

aid of the President, and that Lincoln had said "Government cannot endure

half slave, half free," and "Slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction."

ALABAMA on the 11th January, 1861, TEXAS on the 1st of February, 1861,

VIRGINIA on the 17th April, 1861, issued secession ordinances to similar

effect.

Then, when victory crowned its earliest efforts, when, after having like a

midnight burglar stolen on the ships and arsenals of the Union, after

having, under Buchanan, a

Southern President, (and having had Jefferson Davis, the present

Confederate President, as federal minister at war,) placed southern

officers in command of federal forts, of

federal regiments and of federal dockyards, after having during a long

conspiracy of four years drawn the best trained soldiers of the Union

within its ranks, and created and

disciplined a formidable force,—when after this it met and conquered in

one bloody field the raw and sudden levies of the too confiding and unwary

north—then it issued its

loud notes of triumph, and, as before battle it announced for what it

meant to draw the sword, so after victory it told us for what the sword

was drawn.

Then, STEPHENS, the Vice-President of the

Confederate States proclaimed, at the great seceding convention at

Montgomery:

"Our new Government is founded on the great truth, its foundations are

laid, its corner stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not

equal to the white,—that slavery is

his natural and normal condition. Our Government is the first in the

history of the world, based upon this great physical and moral truth. This

stone, which was rejected by the

first builders, is become the chief stone of the corner in our new edifice.

It is the Lord's doing, and marvellous in our eyes."

Then JAMES WILLIAMS in his "South Vindicated"

said:—

"For the institution of slavery pure and simple, the South drew the sword."

Then the RICHMOND ENQUIRER, of

May 28th, 1863, wrote:—

"For liberty, equality and fraternity, we have distinctly substituted

slavery, subordination and government. There are slave races born to

serve—master races born to govern. Our Confederacy is a God-sent missionary

to the nations."

Then DR. PALMER, the popular Southern divine, preached:—

"The providential Southern trust is to perpetuate the institution of

Domestic Slavery as at present existing, with freest scope for its natural

development. We should at once lift

ourselves intelligently to the highest moral ground, and proclaim to all

the world that we hold this trust from God, and in its occupancy are

prepared to stand or fall. It is a duty

we owe to ourselves, to our slaves, and to Almighty God (! !) to preserve

and transmit our existing system of domestic Servitude, with the right

unchallenged by man to go

and root itself wherever Providence and nature may carry it."

Then one hundred MINISTERS OF THE GOSPEL and theological professors of the

Confederate States, in an address to Christians throughout the world,

adopted at a

conference in the city of Richmond, issued their blasphemous manifesto

upon slavery:—

"The practical plan for benefiting the African race must be the

Providential, the Scriptural plan—We adopt that plan in the south—We

regard abolitionism as an interference

with the plans of Divine Providence."

Thus the South attunes its notes of triumph in its first days of

short-lived victory; and the seal is set on its professions by the

Constitution that it frames. What is the distinctive

feature of that new Constitution as distinguished from the old? Slavery.

The Federal Constitution does not provide for slavery—the Southern enacts

it. Judge the South by its crowning work, that Constitution, to obtain

which it opened the veins of

America, and deluged all its soil with blood.

Section 2 § 1, enacts:—All citizens may travel about the Confederacy

with their slaves, and the right of property in such slaves shall not

thereby be impaired.

§ 3. No slaves escaping to another State, shall in consequence of any State

law become free, but shall be delivered up to the owner.

Section 3. § 3. The Confederacy may acquire new territories. In all such

territories slavery SHALL be.

Yes; this is the object of the deadly struggle: the new empire to be one

vast prison; not on one of its chambers shall the foot of freedom fall, no

hope shall beckon through its

dungeon bars, and wherever its accursed flag shall wave, there slavery

"SHALL BE."

Who now says slavery was not the cause, the origin, the aim, the object of

this war? The South has spoken,—are we to believe it? For slavery it

said it would draw the

sword. For slavery, it proposed its compromise. For slavery, it proclaimed

its ultimatum. For slavery, it issued its ordinances; and for slavery, it

framed its constitution. Can

tongue of man speak plainer? Does the poor innocent swear it is a sinner,

while all the time it is a saint ? Have its press, its pulpit, and its

platform lied? Are its compromises and ultimatums, its ordinances and

constitutions, all enormous falsehoods? Does it know its own meaning, and

does it speak its own mind? Or do gentlemen here, 3,000 miles

from the scene of action, whose feet have never trodden American soil,

whose ears have never heard the groan of the negro, and whose eyes have

never seen the blood of

the slave, know more about the objects of the war than the very men who

started it, the Senates that decreed it, the President who proclaimed it,

and the States that justified it? Shall we believe the great criminal himself, who cries "Guilty" before

the tribunal of History,—"guilty," not in a bated voice, but glorying in

his crime. Or are we to believe the

quibbling lawyer, who, bribed with his cotton fee, is yet ashamed of his

own client, and makes himself the apologist of a liar, that he may not

appear the confederate of a

knave?

They have another cry, however, our English Southerners. They say, "We,

too, are as much against slavery as you are; but the best way to put an

end to it is to help the South

to secede: as soon as it is independent, the South itself will extinguish

slavery." Then why did it not extinguish it years ago, when it had its

majorities in Congress? Why did it

lash, and tar, and maim every apostle of liberty who dared to set his foot

on Southern soil? Why did it levy war to maintain slavery, if it only

desired to abolish it? Why did it

rise against the North for wanting the very thing they say the South

itself is seeking? Why did it make slavery the corner-stone of its new

temple, if it is to be pulled down as

soon as it is built?

Then, when they fail in this false argument, when they cannot vindicate

their own character, they try to blacken their opponents, I suppose, on

the principle that two blacks will make a white. They say: "The North,

too, holds slaves, as there are slave-holding states on the northern side. Why

should you oppose the South for having that which the North has also?"

Yes, there are two or three slave states on the side of the North—and

what does this prove? That

every slave state, bad as it might be, was not quite bad enough to secede

and plunge the Union into a sea of blood even for the sake of preserving

its

domestic institution,—that infamy was reserved for the seceders only!

Honour to those slave states, that, even with a certainty of the abolition

of slavery, support the

abolitionist against their own notion of self-interest. And what would

these men have the North do? Go to war with the loyal Slave States to

abolish their slavery! throw so

many more millions into the tanks of their opponents; lengthen the

struggle by so many more months of battle—deepen the sea of slaughter, by

so many more rivers of blood? Why these are the very men who inveigh

against the armed resistance of the North, even for self-defence! These

are the men who say you should let the South go, with all

its slavery, with all its infamy, with all its blasphemy, sooner than shed

a drop of human blood—and yet these consistent reasoners ask the North to

alienate its allies, to confiscate their slave property, which means war,

desperate and internecine war, and by driving them into antagonism, firmly

root slavery for ever in the border states. No! the North enacts a nobler

and holier part. The sword

for those who have drawn the sword; but our moral example for those who,

though erring brethren, have maintained the peace. Honour to the North,

that has not allowed any

wild passions to drive it from the path of equity and brotherhood. With

physical force in the one hand and moral force in the other, it knows

equally where to strike, and when to

guide. The border states lie between the two great scenes of conflict—the

battle fields of the South and the morale victories of the

North. Our armies on the one side, our example on the other,—and can you

doubt that slavery is doomed in the loyal border states? Can you doubt

that the North is pursuing

the wisest, the noblest, and the most Christian course? Is it the course

best calculated to extinguish slavery along the borders? If it is, then

the North has nobly done its duty.

We are, however, told that the war is made not for that which every

Southern voice proclaims its origin and object,—but for Tariffs—for Free

Trade—for Independence! Let

us analyse these assertions.

The South was predominant for a long series of years, until Lincoln's

election—it was, as is well known, all-powerful in the Union, powerful

enough to elect its own Presidents,

to return majorities to Congress, to obtain the Missouri compromise; to

plunge into the Seminole war, in which 40 millions of Federal dollars were

expended, that 200 or 300

southern slaves might be re-captured; to drag the Union into the Mexican

war; to annex Texas; to pass the fugitive slave law; to wrest the Dred

Scott decision.

Did it then urge Free Trade measures? Nay! that free-trading South

assisted to pass the tariff of 1842, more protective than any other except

the Morill Tariff. And what for?

Because these Free-Traders got protection by it for their own products: it

was a protection tariff for the sugar of Louisiana, for the hemp of

Kentucky, for the lead of Missouri,

for the rice of Carolina! These are the Free-Trader's with whom you are

asked to sympathise.

If Free-Trade was the object of the war, why did the South submit under

the tariffs of 1842 and 1846, and rise under that of 1857—which it passed

itself—nay! which was the

second tariff in succession that was passed by Southern votes? Yes! yes! these Free-Traders can vote Protection Tariffs too. Those two last-named

tariffs were carried by

the South against the opposition of the North. For the tariff of 1846

these were 50 Northern votes, to 73 against it, being a Northern majority

of 23 against the measure; but

there were 64 Southern votes for it, to 22 against it, being a Southern

majority of 42 in its favour. For the tariff of 1857 there were 60

Northern votes, against it 65, being a

Northern majority of 5 against, it; but there were 63 Southern votes for

it, to 7 against, being a Southern majority of 56 in its favour. This

tariff, as I have said, taxed foreign rice

15 p : c : to the benefit of the South Carolina rice growers, and made

similar protective provisions for sugar, and other southern products. Are

not these Southerners

exemplary Free-traders? But some of their apologists here will tell you

that, as these last-named tariffs were less prohibitive than former ones,

the South voted for them on a

Free-trade principle, and the North against them on protective grounds. It

is rather peculiar, then, that these tariffs were, specially protective of

southern products! Oh! they are excellent

Free-traders.

But if these tariffs were free-trade measures, and the secession was for

free-trade and not for slavery, why did the South secede when it was

passing free-trade laws, and

never stir a finger when protection ruled the day? Oh! its apologists

are most consistent reasoners!

Nay! if Free-trade is the object of secession, why is it confined to

Southern States? Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, produce nothing

which European competition can

endanger. An artificial enhancement of European produce is to them as

great an injury as it is to South Carolina or Alabama; yet, all these

States are arrayed on the side of

the North.

Again: if Free-trade is the object of secession, why did the South never

apply to the President to veto the Protection tariffs! They had Southern

Administrations, Southern

Presidents, for many years. What Southern voice asked them to use their

power and stop the obnoxious laws? Oh! the South is a model for

Free-trade,

But we are directed specially to the Morill tariff, undoubtedly a most

protective measure, and we are told, that was passed by the North. So it

was; but why? Because the

Southern Senators withdrew en masse before it was voted—the men who might

have prevented it all went away, and their English apologists coolly

complain of the measure

they did not choose to hinder. No! I am wrong; they did not all

leave,—one remained: Toombs, the man who represented Georgia—Toombs, the

violent war man, now

holding a command in Jefferson Davis's army, and he voted for it! This

departure of the Southern men before the vote was taken, was a secession

trick, that they might be

able to complain of the tariff, should they find it necessary to use this

as a secession cry. But they did not use it, and for a very good reason.

The Southern people are not

fools, and would have said to them, "Why did you abandon your posts, and

allow that law to pass, if you come to us complaining of it now?"

Oh, Englishmen sympathise with the Free-trading South! What was the first

commercial law it passed after

secession. The imposition of a heavy duty on the export of all cotton, and

they are actually seeking to raise a large part of their revenue by a

protective law. That is their first act. Oh! they are

excellent Free-traders!

But you are further told that, irrespective of slavery and free-trade you

should put an end to the war, because war is such a horrible and

unchristian thing, and, therefore, you

should given succour to the South. War

is a great crime, but those who first make it are the criminals. If

they abhor the carnage let them

tell those, who commenced it, to lay down their arms. The house of the

State is broken into by burglars, the master of the house is attacked, and

he defends himself, and you

are asked, forsooth, to call on him to lay down his arms before the

burglar, instead of the burglar being ordered to lay down his arms to him! War is a great crime, but war in

self-defence is a great duty, and the North never struck till it was

stricken. If the North was in fault, its fault was unwise, uncalled for

long-suffering and forbearance. It was not

the first shot fired on Fort Sumter by the South that was the beginning of

Southern aggression. For years it had been preparing, for years it had

taken virtually

the field, and the cannon of Charleston was but the signal of onset for an

army that had long been ranged in arms against the North. Yes! war is a great crime—war for tyranny, for

oppression, for injustice—but war for freedom is a holy thing—above all,

war for the freedom of another—war for the freedom of the weak—war for the rights of humanity and the

laws of God! Oh! the Italians were great criminals at Magenta and Palestro! Oh the Hungarians were

great criminals at Szolnok and Komorn! Such criminals at this moment are

the Circassians and the Poles. But give us more such criminals, Oh God! Crown their arms with

victory, and slavery both white and black will soon be banished from this

earth.

But they have another cry, these men of the pro-Southern platforms here. They tell us that the South is fighting for independence, and ask your

sympathy because it fights so

well.

For independence! Then why did they offer the Crittenden Compromise to

remain in the Union if slavery was conceded?

Independence! Then why did they offer Jefferson Davis's ultimatum? Was

that for independence or for slavery? It was for fetters, not for

freedom, that they made their

offer—it was for the lash, not for liberty, that their ultimatum issued.

Independence! aye! independence to maim the slave—independence to renew

the slave trade—independence to spread slavery over the earth that God made free,—the

independence of Satan to create a hell and spread its confines to the

gates of heaven. "But they

fight well." They do. So does the wolf when it rends the lamb; so does the

tiger when it tears the hind; so—but too often—does crowned tyranny

against despairing justice. So

did the Austrians in Italy;—yet I'm for the Italians. So do the Russians

in Poland;—yet I'm for the Poles! But they are not the only gallant

fighters. I believe the North can fight

a little too. Aye! thank Heaven! for once the might is with the

right,—yet strange it is some men can see the bravery only on the evil

side, and never cheer save when the

devil makes a hit.

2. THE RIGHT TO SECEDE.

The Southern apologists say, however, that irrespective of slavery or

free-trade, their clients had a right to secede. On what ground? "Oh,"

say they, "the states are

sovereign and can do as they like"—The constitution gives them no such

right. On the contrary, it takes all such power away. By the first

constitution of November, 1777, the

States preserved their sovereignty, and such rights as were not delegated

to the

general congress—(in itself an important reservation); but this was found

to work badly. Washington wrote the celebrated letter of 1783, pointing

out the evil, and the present

constitution of the United States was passed on the 4th of March, 1789 for

the especial purpose of putting an end to the independent

sovereignty of the States. This it does most effectually. The Preamble

says: "we, the people of the United States, ordain and establish this

constitution for the United States of

America"—a constitution established by the whole people for all the

States; and that constitution specially and succinctly takes away every

attribute of sovereignty from each

individual State.

ART. 1 prohibits all taxes and duties between States, all treaties and

alliances by States, all coining of money, all emission of bills of

credit, all duties on exports and imports,

all duty on tonnage, all keeping of troops or ships of war in time of

peace, all agreements with a foreign power, all acts of war (unless

actually invaded and no time existing for

delay) on the part of any State, and all agreements or compacts of one

State with another, without the consent of Congress.

ART. 6 says: This constitution shall be the supreme law of the land, and

the judges of every State shall be bound thereby, anything in the

constitution or laws of any State to

the contrary notwithstanding.

ART. 5 provides for the amendment of the constitution on the sole

condition that three-fourths of the States of the entire Union, after long

and great formalities, consent to

such amendment,—thus clearly taking away the power of any individual State

to separate from the bonds of union the constitution imposed.

Who will now maintain that the States were individually sovereign, and

could by right secede of their own will?

How did the South itself construe this Constitution? What do the slave

States themselves say of it?

VIRGINIA was the first to set about altering this evil of

State-sovereignty. In the Virginia Convention, assembled to

ratify the Constitution, Patrick Henry opposed it because it took

State-sovereignty away! Yet, hearing this, Virginia voted for it

on that very ground!

What did SOUTH CAROLINA, the State that inaugurated secession, say? It

declared in 1828, in a document drawn up by John C. Calhoun, the great

secessionist, that

"By the adoption of the Federal Constitution, the State had modified its

original right of sovereignty, whereby its individual consent was

necessary to any change in its political

condition, and by becoming a member of the Union had placed that power in

the hands of three-fourths of the States, in whom the highest power known

to the Constitution

actually resides."

Chancellor Kent, one of American's greatest lawyers, writes as follows:—

"The great and fundamental defect of the Confederation of 1777, which led

to its eventual overthrow, was that, in imitation of all former

Confederacies, it carried the decrees

of the Federal Council: to the States in their sovereign capacity. The past

and incurable defect of all former federal governments, is that they were

sovereignties over

sovereignties. The first efforts to relieve the people of the country from

this state of national degradation and ruin came from Virginia."

Judge Story, says:—

"There was no reservation of right on the part of any State to dissolve

its connection or to suspend the operation of the Constitution as to

itself."

Mr. Benton, a southern man, one of the fathers of the democratic party,

and for thirty years a representative in Congress, tells us that:—

"At the time of its first appearance the right of secession was repulsed

and repudiated by the democracy generally, and in a large degree by the

federal party, the difference

between a Union and a League being better understood at the time when so

many of the fathers of the new governments where alive. The leading

language in respect to it, South of the Potomac was, that no State had a right to withdraw from the

Union, and that any attempt to dissolve it, or obstruct the action of

Constitutional laws

was treason."

The same views were propounded by Presidents Madison, Jefferson, Jackson,

by the representatives of the secession and slave States, Randolph,

Millson, and Teake, of

Virginia Nicholson of Maryland; Kennedy of the same State; Rousseau of

Kentucky; Hamilton of Texas; Etheredge of Tennessee; and by many other

leading southern men,

including Stephens himself, the Vice-President of the Southern Confederacy.

Thus much for the right of secession. The States are, in fact, municipally

independent, but politically provincial. The Constitution speaks for

itself, and needs no further

comment, but I have quoted the utterances of leading Southern men and

States, that it may be seen how it was expounded by the South itself.

Did these men understand it?—Did its framers know the constitution they

themselves made?—Did the men who were born under it, and lived under its

provisions—did the

Chancellors and Judges, the Presidents, and Senators, who administered and

applied its laws, comprehend its meaning—or was it left to them all to be

enlightened by the

superior sagacity of pro-South amateurs in England, who are now kind

enough to explain to the shades of Washington and his compeers, the

meaning of their own

Constitution.

But the right of secession may be urged from a higher stand. I fully

endorse the "sacred right of insurrection." It is not to be lightly

used—but on good and adequate ground

insurrection

is morle than a right—it is a duty. In some cases rebellion to man is

obedience to God. But to justify rebellion, two conditions are indispensible,—firstly: there must be an

intolerable grievance; and, secondly, every moral, legal, and

constitutional means for obtaining redress, must have been exhausted

before the sword is drawn. Then a people

has a right to rebel, and God defend the rebels.

Is this the case with the South? Did it use the Constitutional means at

its disposal? The Constitution gives, as I have already stated, the right

of the veto to the President.

Southern Presidents held office—did the South make an appeal for the veto? The Constitution gives, as I have said before, a power of amendment, by

its 5th Article: did the

South seek redress by the means of that power? No: the veto was the

surprise of Norfolk navy-yard—its petition was the bombardment of Fort

Sumter! Even before the

Crittenden Compromise was offered, it was maturing insurrection; when the

Jefferson Davis Ultimatum was issued, it was an armed insurgent.

Even if it suffered under grievances, the South as we have seen, was bound

to seek relief from them by Constitutional means; but had it any

grievances? Let the South itself

answer.

The Governor of Florida declared:—

"The rebellion was made without complaint of wrong or injustice."

Rousseau, of Kentucky, asserted:

"Our government has oppressed no man, neither has it burdened us a

feather's weight."

Kennedy, of Maryland, said, in May 1861:—

"Maryland has no cause for revolution; no man can lay his hand on his

heart and say 'this government of ours has ever done him wrong.'"

Holman, of Indiana, a democrat, told his hearers:—

"No intolerable oppression exists. Therefore, if the government is

overturned, it will be without justification or excuse."

Millson, of Virginia, Hamilton of Texas, and

Etheredge all maintained that

"There was no just cause for rebellion, no oppression, no tyranny."

The People of Virginia, in convention at Wheelhouse, spoke to the same

effect

The Convention of the Border States, at Frankfort, uttered the same

sentiment in the face of the United South, and

Mr. Stephens himself, the present Vice-President of the Confederate

States, on the 14th November, 1860, made the following memorable statement

in the Georgia State

convention:—

"This government of our fathers, with all its defects, comes nearer the

object of all good government than any other on the face of the earth.

Have

we not at the South, as well

as the North, grown great, prosperous and happy under its operation? Has

any part of the world ever shewn such rapid progress in the development of

wealth and all the

material resources of national power and greatness as the Southern States

have undr the general government?"

In the Georgia State Convention, held in January, 1861, to decide on

secession, Mr Stephens said further:

"What right has the north assailed? What interest of the South has been

invaded? What justice has been denied? What claim founded in Justice and

right has been

withheld? Can anyone name one governmental act of wrong deliberately and

purposely done by the government of Washington of which the South has a

right to complain? I

challenge the answer. Now for you to attempt to overthrow such a government

as this, under which we have lived for more than three quarters of a

century, in which we

have gained our wealth, our stand as a nation, our domestic safety while

the

elements of perils are around us, with peace and prosperity accompanied

with unbounded prosperity and rights unassailed, is the height of madness,

folly and wickedness."

Thus much for the right of secession. Insurrection without warranty of

law, insurrection without legal attempt at redress, insurrection without

grievance, is rebellion.

But this rebellion of the South is worse than any that history has

recorded—for not only is it a rebellion without cause, but a rebellion for

impunity to commit the blackest crime.

Nay! it had not, to start with, the sanction of its own majority. It is a

rebellion not of the South against the North alone, but a rebellion of the

South against itself. The

Presidential vote of 1860 was cast virtually on the question of Union or

Secession. The Unionist candidates were Lincoln, Douglas, and Bell. The

votes, taking the whole

Union, were as follows:—

|

For Lincoln,

Republican, Anti-Slavery Unionist |

1,857,610 |

|

Douglas, Squatter Sovereignty, Unionist |

1,365,976 |

|

Bell, Union-saving Whig |

590,631 |

|

Total Union Votes |

3,814,217 |

|

For

Breckenridge, Secessionist |

847,953 |

|

Majority against Secession |

2,966,264 |

But in the Secession States themselves, how stood the votes? In those very

States the votes were divided between Douglas and Bell, the Unionists, on

the one side, and

Breckenridge on the other.

|

The Votes

for the two former were . . . . |

679,498 |

|

For the

Secessionist, Breckenridge . . . . |

540,871 |

|

Shewing in

the Seceding States themselves a clear |

|

|

majority against Secession of. . . . . |

138,627 |

3.—THE RESULTS OF THE WAR AND THE

INTERESTS OF THE ENGLISH PEOPLE.

Failing on all other ground, the apologists of the South tray to enlist

our sympathies by saying,—1st, that the North is giving way, that it is

overwhelmed with debt, exhausted in

men, money and resources, and cannot hold out much longer. 2nd, that the

struggle is so frightful and so hopeless for the North, that it ought to

be stopped; and 3rdly, that to

"stop the war" is the way to "get the cotton."

We will successively consider these propositions.

Is the North overwhelmed with debt? On the 1st of September, 1863, its

debt was 1,200,000,000 dollars, less than one-fourth of the debt of

England. This American debt

however, we are reminded, was incurred in two years, while England's took

forty to accumulate. True. I accept the comparison—but during that time

England raised 63 per

cent. of its total outlay by taxation, while America has so raised only

14⅓ p.c. True,

but America, (I mean the loyal Northern States alone) have over Great

Britain as during that period an advantage of 28 per cent. in property, 30

per cent. in population, and 110

per cent. in annual produce. True, but with their ordinary resources,

without raising an extraordinary tax, or burdening the people one

feather's weight, the Northern States

could pay off this debt in less than 16 years! Yes! the North is still

practically untaxed, untouched, undrained. Such it is actually. But what

is its rate of progress? The

increase of wealth in the loyal States alone was from

|

1840 to 1850 .. 64 p c

1850 to 1860... 126 pc |

What was the increase of the wealth of Great Britain during the same

period? Only 37 p.c.

What was the increase of the Southern States? Only 3 p.c. and in that

they reckon the increase of slave property, which is in fact their

weakness, not their strength—their

poverty, not their riches, as you will see hereafter.

But you may say this increase was before the war. So it was—and what has

it been since the war? Take the great war year 1861-1862. The North has

never before been so

prosperous. Its material well-being has grown with unparalleled rapidity. From beef to books, from books to beef, the progress has been alike

remarkable. In that year, the

booksellers' circulars show an unprecedented rise in the demand for

literature. In that year, besides supporting all its armies in the field,

the North exported 80,000,000 dollars'

worth of breadstuffs more than it ever exported in any one year before. In

that year, the depositors in the Savings' Banks exceeded by 28,842 the

number of depositors that

had ever been annually recorded. In that year the amounts deposited were

5,618,235 dollars more than other year had ever witnessed.

Does that look like being overwhelmed with debt? Nay the very debt is a

guarantee of Northern strength and a bond of union between North and West. The money borrowed,

is borrowed not from foreigners, but by the government from the people:

it is a national vote of confidence in the administration; every dollar

subscribed is a pledge of loyalty

from the subscriber; it is a link connecting West and North. From Mexico

to Maine the loan has been subscribed for, and while the South seeks to

separate West and North by

an iron sword, West and North are sealing their eternal union with a ring

of gold

If you reflect, you will see that the capital of the North is

inexhaustible, alike in land, in men, in bullion. In land:—one thousand

million acres of public lands are still at the

disposal of the government. In men:—24 millions of people inhabit the

Loyal States—increasing at the rate of 50 p.c. in every decade. In bullion:—the gold regions of the North

extend 1,100 miles in length, 1,100 miles in breadth,—1,000 square miles

of gold-enshrining soil—land fruitful to support a teeming population,

leaving its surplus labour to the

golden harvest. Such is the power of the North—such is its wealth. The

granite mountains are its treasure chests, whose ingots illimitable labour

coins in the sparkling gold of

the waving wheatfield, and the silvery tissues of the untiring loom.

What has the South to array against this? An average of 3 p.c. of wealth

against 126 p.c., seven million whites and

four million blacks, against 24 millions. Nay! not four

million blacks. The negroes are its weakness. The slaves require an army to

watch them, taking away from the rebel numbers in the field. Nay! not

seven million whites. They

had seven millions, while their confines still remained untouched. But

county after county, state after state, with all their population, white

and black, have been wrested from

the southern grasp,—leaving diminished numbers with perishing resources to

meet the ever-growing power of their foe. Where are the gold regions—where

are the public

lands of the South? Nay! while the riches of Northern soil become

greater every year, the South is decaying beneath the curse of slavery. Slavery exhausts the soil. The

slave system is practicable only where labour is carried on in masses. The

slaves are trained to one especial kind of toil. Under this system, the

rotation of crops is

impracticable, and therefore the planter tries to make as much out of the

land in as short a time as possible. Therefore sugar follows sugar, rice

succeeds rice, and cotton

cotton—and the soil rapidly becomes impoverished. The South teems with

worn-out plantations and exhausted soil.

Such being the relative strength of the combatants, is the perseverance of

the North equal to its resources? Let the last vote tell; the republican

majority, the Union Party, the

party determined to enforce Union and Emancipation in America, has carried

the last election by majorities such as it has never known before, and

where democratic falterers

were hitherto in the ascendant, abolitionists and unionists have been

elected by overwhelming.

The Southern advocates in England farther say, "Stop the War," that we

may "get the cotton"—and they back their words by pointing to the horrors

of the struggle, and urging

that it is to the interest of English working-men to recognise the South.

"Stop the War!"—so say I—would to heaven it could be stopped on a just

basis!—and therefore I say, leave the North alone to stop it.

"Stop the war?"—Will those gentlemen be kind enough to tell us how they

propose to do this? I have never heard that yet. Is it by the

"recognition" which they advocate? What

does this recognition mean? How will it stop the war? They must intend one

of two things; either bare recognition on paper, or recognition backed by

arms. If the former, will

recognition alone dismount a single battery, sink one monitor, or silence

a solitary gun? A clever way, certainly, "to stop the war!" It won't do

that, but I'll tell you what it will

do—disgrace the English people for ever—make them the abettors of the

vilest criminals that ever stained the page of history,—and bring down on

the heads of those base

allies the hatred of the noblest republic the world has ever known. No!

gentlemen! if we needs must sell ourselves to the devil, let us, at least,

get something for our bargain!

"Stop the war!" No! it would create another. Do you

think America would ever forgive that recognition?

England undoubtedly can hold its own—but, if we are to plunge into a

conflict—do let us, at least, be on the right side, not the wrong. On the

side of freedom, not of slavery;

on the side of a good government, not on that of unjustified rebellion.

But, if their recognition means anything, it means armed intervention. If

it don't it means worse than nothing. "Break the blockade and get the

cotton," that is what it means.

Do you know what that would cost? England's commerce—swept by privateers

from off the seas. Debt, taxation, and misery for all time to come. You

know the price of the

Crimean war; an American war would cost three times as much. Who would

pay that? You the people; you the shopkeeping and working classes of

this country; you and

your children's children through all posterity burdened with a crushing

load of taxes—and for what? Perhaps that the subscribers to the cotton

loan may save the guilty

guineas they have invested in the devil's bank of slavery in the South.

Which do you think the most profitable course, to wait a little longer for

the cotton, or to buy it at such a cost?

And these are the men who cry out against the horrors of war with forty

parson power, who enveigh against the bloodshed and would plunge us into a

war and slaughter ten

times more horrible than that which they denounce! Are these safe

councillors? They would give us carnage instead of cotton, taxation

instead of trade, and want instead of

wages.

But would you get the cotton even by these means? If we are to have it, we

want our supply to rest on a safe basis. If so, I say separation of the

South from the North destroys

our cotton manufacture—union alone can save it. Two rival States, parted

against the will of the more powerful and parted through foreign

interference—would never be long at peace. Every steamer might bring us tidings of a fresh rupture; we should look

forward to every mail with fear, not with hope—lest each new telegram

should announce to us

another conflict—another war—a new blockade—a fresh panic for our cotton

mills—and the old battle of misery and destitution have to be fought once

more.

And yet you are told, it is to the interest of working-men to recognise

the South!

Working-men! I say the South is your enemy—the enemy of your trade, the

foe of your freedom—a standing threat to your prosperity.

Is it for the slaveholders to appeal to working-men for sympathy? Slave

labour is a direct aggression on the free labour of the world. It competes

with you in the world's

market, and

you must crush it, or it will ruin you. Not yet, perhaps, but

ere long. Free scope for the development of slave labour would produce such

a labour surplus in the North that immigration would become impossible. Is

not America the