|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER III.

MAY MERTON FINDS A FRIEND.

I ENTERED Madame's room

with no little trepidation, and saw my poor little school-fellow

sitting on a stool. She did not exhibit any violent grief, but

there was a painfully forlorn expression about her always wistful

face; and though she did not cry, she would neither eat nor take any

notice of our caresses.

When the school-bell rang, Madame sent me down; for I was of

no use. The teachers inquired after the poor child, and one of

them said, that though she was very sorry for the poor ayah, she

thought her removal was by no means to be regretted on the child's

account; because as long as that foreign woman was about her, she

would never have thoroughly settled at school, nor attached herself

to those who had the responsibility of her teaching. I could

not tell how this might be, but I thought that, even to a child, it

must be a terrible thing to lose the only person whom she deeply

loved, and with whom she was thoroughly at home. I hoped she

would now begin to attach herself to us, and soon get over the loss

of her ayah.

But from day to day, when I saw her, she was still pining and

fretting, sometimes moping on her little stool, sometimes crying in

Massey's arms, and constantly becoming thinner and paler, losing her

appetite, and refusing to do as she was bid.

At first Madame hoped she would soon forget her grief, but

when three or four weeks had passed away, and still the tiny face

grew thin, and the little sorrowful voice was heard wailing in the

night, she became seriously unhappy about the child; for she was too

young to be reasoned with, too ill to be punished, and too far away

from her parents to be sent home. Sometimes they would take

her out for a drive, or think to amuse her by bringing her down into

the garden, but after taking a few steps she would put her wasted

hand to her side, and say in a piteous voice, 'It hurts here; it

always hurts here,' and beg to be taken in again. Her medical

attendant said it was extremely bad for her to fret and cry.

He assured Madame he could do nothing for her unless she was kept

calm and cheerful; an easy thing to say, but difficult to

accomplish, for every dose of medicine cost a contention and a

passion of tears that almost exhausted her feeble frame; and though

she was tempted with many dainties, she could hardly eat enough to

sustain life.

Madame was accustomed to be implicitly obeyed, and scarcely

knew how to deal with this poor infant, who set her authority

utterly at naught, and was not to be flattered or caressed into

submission. She had not been well brought up, and though when

in health she had yielded to an influence that kept the boldest

spirits in order, she now ceased to care for praise or blame, and

all her original wilfulness came back again.

Madame was evidently quite wretched, and was losing

confidence in herself altogether. She caused each teacher in

turn to try her powers with the child, then she called in the elder

girls, and encouraged them to exert themselves to make the little

sufferer take her medicine. But all was of no avail; low fever

came on, and life seemed actually to depend on a docility that it

was quite hopeless to expect from her.

Yet the wilfulness of a little child does not alienate

affection. There was still something sweet in the baby

resentment that blamed 'all the cruel ladies' for taking away her

mamma and her nurse. The little voice, in all its sorrow, was

still silvery and touching, and the wistful features were still

pretty, though marred by tears and illness.

It was about this time that Miss Black came among us, but, as

I have said before, her coming attracted little attention; our

thoughts, when not occupied with the child, were all given to

Caroline. Miss Black always inquired with great interest about

the poor little creature, but Madame never thought of asking her to

come and see her, because she was a stranger.

One night, when we were all quite unhappy about our little

school-fellow, I was called in to see if I could make her take her

food by talking Hindustani to her. I did not succeed, but as

Madame did not desire me to withdraw, I sat by the bed thinking how

mournful all this was, and wishing there was something more useful

for me to do than snuffing the candle which stood on a small table

beside her.

Poor little child! I remember her wailing voice as she

sat half-upright in her bed, peevishly refusing either to take her

supper or to lie down and sleep, when the door into our bedroom was

softly pushed open, and Miss Black came in, with a long white

dressing-gown on.

I thought she came to see what she could do to help us, but

apparently it was not the case. Miss Black did not look at us,

but at something soft that lay upon her arm, and she swept close up

to the bed without saying a word. Madame, utterly dispirited,

was weeping behind the curtain. The child paused in her low

cry, arrested by the sight of the stranger, and said, 'Who's that,

with her best frock on?'

'I've got something so pretty here,' said Miss Black, still

looking down upon her arm; 'I don't know whether I shall show it to

anybody.' She seemed to consider, and in the meantime the

child regarded her with fixed and wondering attention.

'If I knew of any very good child, perhaps I should show

these little things to her,' said Miss Black, pretending to talk to

herself

'Wee, wee, wee!' cried the things on her arm.

'But I daresay nobody wants to see them,' she continued.

'I want to see them,' said the child, checking a long sob.

'Ah!' said Miss Black, 'they seem very hungry, poor little

things!'

'Weeweewee!'

'Oh! do show them to me,' sobbed the child; and when Miss

Black took up two tiny kittens by the neck, set them on the bed, and

let them creep towards her, she was so delighted that she began to

laugh, and try to feed them with some of the bread and milk which

she had been vainly implored to eat for her supper.

'Oh! they cannot eat bread,' said Miss Black quietly, 'they

are too young; but when we have emptied the saucer, they shall have

some milk in it.'

She sat by the child and supported her feeble frame.

'Now, then,' she said, 'let us eat this,' and she held the spoon to

the child's mouth, which was opened half unconsciously; for Miss

Black had begun to relate a wonderful story about four white kittens

who lived in a hay-loft. The child listened with rapt

attention till the supper was eaten, when the tale came to a sudden

conclusion; then some milk was poured into the saucer, and the real

kittens were fed.

When they had lapped every drop of the milk, Miss Black

produced a little basket and a piece of flannel, in which she let

the child help to place these playthings that had appeared so

opportunely.

'Now then,' she said, let us put them on the table, and you

shall sit on my knee, and peep at them, while Miss West shakes up

the pillow, and makes the bed all smooth and comfortable.'

No objection was made to this arrangement, but the little

wasted arms were held out, and the child, almost too weak now to

rise, tried to creep away from the pillows to her new friend,

suffering herself to be nursed and fondled till she could be placed

comfortably in her bed again. Then, indeed, her face changed,

and she said in a piteous tone, 'But I don't want you to go away.

I want you to get into my bed. Will you?'

Miss Black darted a glance at Madame, who nodded assent.

'O yes!' she said. 'I should like to sleep in your pretty bed

very much.'

'And I may see the kittens to-morrow?'

'O yes!' repeated Miss Black, lying down beside the child,

whose chest still heaved every now and then with a deep sob, but who

was so completely wearied and faint for want of sleep, and the

comfort-cherishing that children so much require, that now she was

with some one who could manage her, she fell at once into a deep

sleep, and her little wayward face began to look calm and almost

happy.

Madame had kept completely in the background from the moment

of Miss Black's entrance, and when she saw that the child would soon

be asleep, she made a sign to me to remain perfectly still.

She looked so happy, when at length she came up to the bed, and

shading the candle with her hand, drew back the curtain, and saw her

poor little pupil fast asleep.

'Ah! this has been a terrible anxiety to me,' she murmured,

and then she stooped and kissed Miss Black, a thing I had never

seen her do to any pupils but the little ones. 'I am greatly

indebted to you, my dear,' I heard her say; 'you have relieved me

from great dread for this desolate child.'

Miss Black cautiously turned her face upon the pillow the

child's long curls were spread somewhat forlornly across her

forehead, she parted them with her soft hand; the little creature

was in a most healing slumber, and she said, 'I would take the

greatest care of her, Madame, if you would take some rest.

Will you trust me?'

Madame could not make up her mind to leave the room, but she

dismissed me to mine, and took possession of the other bed in the

nursery. She was soon asleep, and the door being left ajar, I

could see distinctly the little child and her new nurse, and I

wondered what it was that had given Miss Black such ascendency.

I do not think anything more transpired than what I have narrated,

and all her art seemed to have consisted in first surprising and

then amusing.

But at fifteen one does not reason much, nor spend the

precious midnight hours in any abstract speculations. I fell

asleep, and did not wake till we were called, when I found the door

shut between us, and was not told anything about the child till

after breakfast, when Belle waylaid a maid-servant as she came down

stairs, and heard from her that the physician had already paid his

visit; that he thought the child better, though extremely weak, and

had as usual requested that she might be kept as cheerful as

possible.

But about ten minutes before the first school-bell rang, Miss

Quain desired me to carry Miss Black's exercise-book and some ink

into the nursery, as 'Madame had given her leave to write her

exercise there. I went up and saw the little patient lying in

bed, looking decidedly better, and listening to a story,

― a story, namely, concerning a

young cock-sparrow, of rebellious turn of mind, who would insist

upon hopping under a hand glass, which a gardener had propped up

with a piece of wood. His mother, in forcible and affecting

language, had entreated him not to enter that dangerous place; but

this deluded bird, when she was not looking, went in. The

gardener came and shut the glass, and the sparrow was obliged to sit

inside, peeping through the glass and flapping his wings, with

nothing to eat, while his good, obedient brothers and sisters had

some little ants and some juicy caterpillars for their dinner.

This story, though it does not sound probable, nor of very

absorbing interest, was precisely suited to the infantine listener,

who remarked concerning the sparrow, that if he would not do as he

was bid, it served him quite right to be shut in there; and then,

while I was assisting Miss Black with her toilette, she tried to

make further acquaintance with her new friend by asking what her

name was.

'Oh, I have such a long name,' said Miss Black, that I don't

think such a little girl as you could say it; my name is Christiana

Frances.'

'Say it again,' asked the child.

The name was repeated, and, after pondering it silently for

awhile, the child said distinctly, in her sweet treble voice, 'Miss

Christiana Frances, will you say my little name now? May

Merton is my name.'

'Little May Merton, I love you very much,' said Miss Black. '

'And will you sleep in my bed to-night, Miss Christiana

Frances?' pleaded the little creature.

'O yes, if you are good,' replied Miss Black, who well knew

that Madame would be too happy to permit it.

'I am good,' said the child, glancing towards an empty

medicine glass; 'and you said you would tell me another story.'

But this other story, my readers, I regret that I cannot lay before

you, though it was doubtless of surpassing interest; for the bell

rang, and I left little May to the companionship of her

benefactress.

I feel that I have passed over the first appearance of Miss

Black among us, as if it had been a matter of very small importance.

It seemed to be so in the first instance, for though she

could easily make her way among children, she was particularly

reserved intentionally reserved among us; but as she is to play

a somewhat important part in the little scenes which I am about to

describe, I will try to give a sketch of her appearance and manner.

She was rather older than most school-girls, being nearly

seventeen years of age. She had only come into the house for

the sake of learning accomplishments, and was treated more like a

parlour boarder than a mere pupil, though she slept in our room, and

took her music and German lessons with us. Her appearance was

elegant and agreeable, perhaps somewhat pretty. I speak of her

as I saw her at first, for afterwards affection clothed her

deservedly with many charms. She was very womanly in manner

and character, and looked quite grown up, though she had a slender,

girlish figure. The hair and complexion were extremely fair,

yet she had black eyebrows, which met, and gave her sometimes, when

she was deep in thought, a severe expression. There was a

certain self-possession and calm about her which was not altogether

free from pride, and which made us, from the first, fond of

contrasting her character with that of Caroline, who was so winning

and engaging, and who could refuse a kindness in a manner more

flattering than the simple gravity with which Miss Black would grant

it.

Caroline seemed often bent on pleasing and winning all

suffrages for herself. Miss Black was never trying to please,

though she was often trying to do good. Moreover, she was

deeply affectionate; it seemed to be as essential to her happiness

to find people on whom she could lavish her care and attentive love,

as it was to Caroline to excite and receive the affection of others.

Caroline was clever, Miss Black was intellectual, and by far

the most gifted pupil that Madame had ever received; but in spite of

the difference in their age, she was not equal to Caroline in that

peculiar tact, and that superior knowledge of character, by which

this singular young creature obtained for herself so much power.

Caroline always chose the most acceptable species of flattery to

bestow on each school-fellow whom she wished to influence, and found

the readiest way to their hearts, without yielding in return

one-half of the affection that she received.

'Oh, what a name!' exclaimed Caroline, when I told her Miss

Black's Christian name; for we, school-girl like, had tried to find

it out, but had not hitherto succeeded.

'Christiana reminds me of the Pilgrim's Progress. I

shall always feel inclined to address her in antiquated fashion.

Prithee, good Christiana, lend me thy French Dictionary.'

'But Frances is a pretty name,' I observed; 'and she says

that is the name she is called by.'

'I shall always call her by both,' said Caroline 'Christiana

is a moral name, and Frances is an intellectual name. She is a

perfect mass of morality and cleverness, far too much so for my

taste "stuffed with honourable parts," as that old gentleman

says.'

'You don't mean Shakspere?' I exclaimed.

'I mean the man whose scenes and things we read sometimes,

and whose picture has a turn-down collar yes, Shakspere, to be

sure; I thought at first it was Chaucer, but now I remember it

isn't. Well, if the said Christiana Frances likes to sit up in

the nursery with May, telling stories of cock-robins, instead of

cultivating the acquaintance of her equals, I have nothing to say

against it, I am sure.'

'No,' I remarked; 'you always said, that as far as you were

concerned, any one might patronize May who was willing.'

CHAPTER IV.

MISS BLACK.

IN looking back

on those days which followed the illness of little May, I can

scarcely recall her image without that of Miss Black; 'My Miss

Christiana Frances,' as May always called her.

Madame, at Miss Black's own request, permitted her to take up

her abode in the nursery, as her bedroom; and shortly afterwards my

bed also was moved there, and a friendship gradually grew between

us, which enabled me to appreciate and love her character.

Those were happy days for May and me. My old friends,

with the exception of Belle, had all left The Willows; and some of

the new-comers often made me extremely uncomfortable, by quizzing

me, and laughing at me, if ever they found me indulging my love of

reading, or secretly studying any subject, by myself. Frances,

on the contrary, used to encourage and help me; and when I

complained of the teazing I endured, she used to sympathize with me,

though it evidently surprised her that I should care for it.

When she saw me hardly beset by Caroline and the elder girls, she

would sometimes enter the lists with me, and turn the tables upon my

tormentors; for she had considerable wit, and used to adopt the

quaint language which Caroline had sometimes addressed her in,

because of her name, and use it much more drolly than any of her

companions.

About this time four of the girls, myself among them, formed

a club, which we called, 'Them Mental Improvement Club,' a

childish thing, no doubt, but well meant, and for which we used to

write original articles in prose and poetry. When Caroline

discovered this club, she was very merciless upon us, partly, no

doubt, pretty dunce, because she could not write well enough (as we

were pleased to think) to be worthy of a place in it.

The club sometimes met in the coach-house, sometimes in a

bedroom, in short, anywhere that seemed to offer a safe asylum from

the ridicule of those who were not members. But I am bound, as

a faithful historian, to say that the 'mental improvers,' as

Caroline called us, were so made game of, and, metaphorically

speaking, so hunted down by her, that they were on the point of

dissolving, when one day a certain picture was discovered pinned to

the head of Caroline's bed. This picture was duly headed in

old English letters, 'Third Meeting of the Mental Improvers, with

Miss C. B., as Aquarius, pouring cold water on the concern.'

In the centre of the picture were four girls huddled together, and

reading from a paper. The unknown artist had expended a great

deal of trouble in making the figures extremely sweet and pretty.

Standing over them, with a huge watering-pot, was a ludicrous and

hideous caricature of Aquarius, with a face so like Caroline's, that

it was impossible to mistake it. A certain air of malice was

imparted to the features of Aquarius, as the streams of water came

pouring down, which by no means impaired the likeness.

Poor Caroline was deeply disgusted at the highly unflattering

likeness of herself; perhaps she was still more annoyed at the

beauty of the four girls seated on the ground. Their dress and

hair were represented as by no means disordered by the shower (for

artists will take liberties with nature and possibility); on the

contrary, the general air of Aquarius reminded one of the most dirty

and common-looking of little maids-of-all-work. Underneath

were these words:

'C. B. returns thanks to her friends and the public

for their distinguished patronage, and hopes, by unwearied efforts

to merit its continuance. N.B. Shower-baths gratis

every Wednesday afternoon.'

Wednesday afternoon was the time when we met. We all

thought in our inmost hearts that there was but one person in the

house who was artist enough to have made this really clever drawing.

No one said who she thought it was; and when she whom we suspected,

knocked at the door and came through the bedroom of the second class

with May in her arms, and a countenance of settled gravity, we were

a little puzzled. However, we never asked for any explanation;

for the members of the club would have felt it something like

vanity, to take for granted that those lovely young creatures on the

ground were meant for them; and as for Caroline, she was much too

politic openly to betray any anger; that would have been to admit

that she acknowledged the likeness and the character.

It was soon evident to all the school that Caroline

considered Miss Black in the light of a rival, though, as the latter

was remarkably independent, and scarcely ever interfered with

others, there was for a long time time very little opportunity for

showing it.

In the meantime little May got quite well, and grew plump and

rosy, though she was still so extremely small, that the girls used

to say they thought all her growth went into her hair; rather an

unscientific way, perhaps, of accounting for her infantine

proportions. Her hair was of very unusual length and beauty,

and I well remember that when we used to pass our fingers through

the loose curls and straighten them, they would reach to the hem of

her frock.

Pretty little May, she was always a pet amongst us, and so

light that it required no great strength to carry her about.

Frances spent many an hour that winter in carrying her out in the

garden, when the sun shone. Though cheerful and well now, she

was very tender, and easily fatigued; but endowed with a spirit and

a will strong enough for a creature five times her size.

Her improvement, under the care of Frances, was surprising,

and there was something extremely pretty and almost touching, in the

confiding way in which she gave her whole heart to her. Her

devotion was fully repaid, for we all felt that Frances loved this

morsel of a child more than all the rest of the household put

together. She was certainly an engaging and desirable little

plaything, and we all, including Caroline, liked to amuse ourselves

with her now and then, when she was well and good-tempered; but we

always gave her back to Frances when we were tired of her, as the

person to whom she naturally belonged, and whose duty it was to

attend to her. Her kindness to May was soon looked upon even

by Madame as a kind of duty. Yet I must do her the justice to

say that she did not tire of it. All the trouble she took in

teaching, cherishing, dressing, playing with, and telling stories to

'her child,' seemed to cost her very little effort. She was

systematically good to little May, not only when she was droll and

tractable, but when she was naughty, troublesome, and cross, as all

children are at times.

Some of the girls used to wonder how Frances could bestow so

much trouble on the child: I never did. I used to think of a

speech made to me a few months before, by a little cousin of mine.

'I think,' said this child, with grave contempt 'I think I shall

dig a hole and bury my doll.'

'Poor thing!' said I, 'what has she done?'

'Why,' replied the child, in a sharp tone of injured feeling,

'she's no use at all. I'm always saying, "How do you do?" to

her, and she she never says, "Very well, thank you."'

Now little May was a doll that could say, 'Very well, thank

you.' She was by no means a passive plaything.

If Frances left the door open, she invariably ran out, and

had to be brought back laughing and shrieking. If Frances left

her ink in an accessible place, May would dip a pen into it; and if

a drawing was at hand, May would put some finishing touches to it;

if not, she would wipe the pen on her pinafore. If she saw

Frances at work, she would seat herself beside her, on her mora

(stool), and quietly taking a needle and a long thread from the

cushion, would lift up some small article, such as a lace collar or

a pinafore, and begin to stitch through and through it, drawing up

the thread till the whole was one shapeless mass of crumples and

tangles, like a particularly bad ball; then she would proudly hand

it up to the unconscious Frances, exclaiming, 'There, I've mended

him, I want another to do.'

Frances obtained for herself the privilege, as she considered

it, of always being allowed to put May to bed; and before carrying

her up-stairs, she used to take off her shoes and socks, and warm

the child's tiny feet in her hands by the schoolroom fire. Oh,

the brushing and smoothing that those long, silky curls required; no

one but Frances would have found any pleasure in such a task; and

then, when she had tucked up her little charge and kissed her, she

always told her a story out of the Bible before she went away.

It was astonishing how much of scriptural incident and character the

child soon acquired in this way, and how many hymns and texts she

learned almost spontaneously. Indeed, it was not wonderful

that Frances should have taught her best that in which she took the

deepest interest, religion. She had none of that false shame

which prevents so many school-girls from daring to profess any

interest in this most important of all subjects, even when they feel

it strongly, and are unhappy at their own want of courage which

leads them to conceal it. The girls became aware that Frances

thought a good deal on matters that concerned the soul, just as

easily and quickly as they did that Frances wished to be a good

German scholar; for though neither fact was announced, both were

evident to any one with the slightest observation.

Little May reaped the benefit of this openness, which had a

most salutary effect in the school, and the more so, as it was not

inconsistent with that natural reserve which Frances seldom laid

aside. She quietly admitted her religious impressions, but she

never enlarged upon them.

Many a delightful evening in the spring-time, when I have

entered our bedroom, I have seen little May lying in her pretty bed,

and Frances reclining beside her, with her cheek on the same pillow,

telling those evening stories till the child gradually closed her

eyes and fell asleep in the broad daylight.

May had been at school about eight months, when one morning

Caroline received a letter by the Indian mail, from Mrs. Merton.

She gave a message to little May from her mamma, but it amounted to

little more than her best love, and that of the child's father.

Caroline, however, read the letter with deep interest and a

heightened colour, which gave us the impression that there was

something more than usual in it. School-time was at hand, so

we could hear nothing about it then; but we did not doubt that

Caroline, who was eminently sociable in disposition, and completely

unable to keep a secret, would tell us the contents of the letter

when she had an opportunity.

It was as we had expected. After school, Caroline was

walking in the orchard, conning her letter, when she met little

Nannette coming out of the hop-garden with an armful of cow-parsley

for her rabbits; and she sent her to us, to ask if we would join

her. There were six of us together, and we forthwith went and

found Caroline under a great apple-tree, seated upon the moss,

reading her letter. The tree was thick with pink flowers, the

sky was very blue above, and the orchard was full of bees that had

come out to rifle the blossoms.

The day, though remarkably clear and sunny, was somewhat

cold. We were all clad in the large shepherd's-plaid shawls,

which were our garden wear during the cold months; and as we wished

to hear the letter comfortably, we began when we arrived, to make a

kind of tent for ourselves, taking off three of these scarf-shawls,

and tying one end of each to a long hop-pole, which we then stuck

into the ground, making the whole safe and warm by laying stones to

steady the ends which were on the ground. Having thus erected

a shelter of the most desirable kind, with its back to the wind, its

opening to the sun, a beautiful tree overhead, and a pretty view of

the hop-plantation before us, we collected a quantity of dry leaves,

and carefully packed ourselves among them like birds in a nest,

covering up the whole community with the other four shawls.

Caroline then began her communication in these words: 'Sir Aimias

Merton is dead.'

'Dead! That old bachelor dead, of whom we had heard

such strange things. Who lived all his days in his own lodge,

hoarding his money. Who made his housekeeper give him half of

what she got by showing the house. Who refused his young

brother money enough to buy his commission; and who had been known

to make only one present, a present of an old mourning-ring to the

said brother's bride, muttering that he hoped there would not be a

large family, to eat him out of house and home!'

'Yes,' Caroline said, 'he was dead, and his brother had come

into the estate, and the whole of his princely fortune. Sir

Aimias had heard that living was remarkably cheap at Smyrna, and he

had actually set out and walked the greater part of the way to that

somewhat outlandish city, and no doubt done the remainder of the

journey with due regard to economy. He had lived there very

comfortably, because very cheaply, for some months, till he was

taken ill of a fever, and so died.'

'But does Mrs. Merton tell you all this?' asked one of the

party.

'Not exactly in the words I have used, my dear,' said

Caroline, laughing. 'She says: "Our brother took a pedestrian

tour across Europe, and then made his way down to Smyrna;" that is a

respectful way of saying that he tramped, as the policemen

called it, part of the way, and begged perhaps (who knows?), the

remainder.'

'What a change for Mrs. Merton!'

'And what a change for the Baronet! Mrs. Merton says

they are both coming back directly, and she hopes they shall reach

England by the beginning of the Midsummer holidays.' Here

Caroline paused.

'And they will go to live in that beautiful house,' said one

of us; 'that house which poor Sir Aimias kept in such fine order,

but never occupied himself.'

'Yes,' said Caroline, 'and Mrs. Merton says she shall have

May and me to spend the holidays there with her.'

'May and me!'it sounded rather odd; I thought, not a

customary combination.

'I wonder whether they will let May return to school,'

remarked Belle l'Estrange.

'Not likely,' said another; 'and what a grief that will be to

Frances!'

'Oh, Frances is going to leave soon herself,' interrupted

Caroline hastily; 'she will only stay till Christmas.'

'Does Mrs. Merton say anything about inviting Frances also to

stay with her?' I inquired.

'How should she,' replied Caroline, incautiously, 'when she

never heard her name?'

'Never heard her name!' I exclaimed; 'why, I thought you

wrote often to Mrs. Merton, Caroline.'

Caroline turned her head till her bright eyes rested upon me.

There was something deliberate in the action; and she conveyed a

good deal of tranquil surprise into her survey, which was perhaps

intended to punish me for my audacity; and certainly abashed me

greatly, and made me blush up to the roots of my hair, and feel that

I had not a word to say for myself.

'I used to write occasionally, just to tell Mrs. Merton that

May was well,' said she, speaking slowly, and with an air of

distaste and languor. 'It was a trouble, of course, but I did

it; sometimes I put in the names of her primers, and the pot-hooks

she was doing; but I have not much time for writing, and no talent

for it, as you mental improvers have; and of course I cannot

give sketches of scenes, and occupations, and characters here, as

Sophia can; and besides, I had no reason to think they would be

interesting, if I could.'

It was pretty evident, then, that Caroline, in writing to

Mrs. Merton, had never even mentioned the name of Frances; and

though we were always inclined to take the very best view we

possibly could of everything that Caroline did, there was an awkward

silence now, which Belle at length broke, by charitably remarking,

'Of course, Cary, dear, you could not have known how soon Mrs.

Merton was coming home.'

Caroline gladly caught at this straw, and cleverly turned it

to her advantage.

'Of course not,' she said gaily, and with her own fascinating

smile; 'but Sophia seems to expect people to have prescience.

Ah! my little presidentess of the "mental improvers," you show a

marvellous partisanship; you are quite in the interest of the female

pilgrim. You think I ought to have given the exact pedigree

and description of Frances, in person, mind, and manners, just as

I should have done, if had known that she was so soon to meet

Mrs. Merton.'

She looked under my hat as she said it, and I do not know how

it was, but I certainly felt as if I had done something foolish; and

when she laughed and kissed me, I was so much ashamed that I could

not help turning away my face.

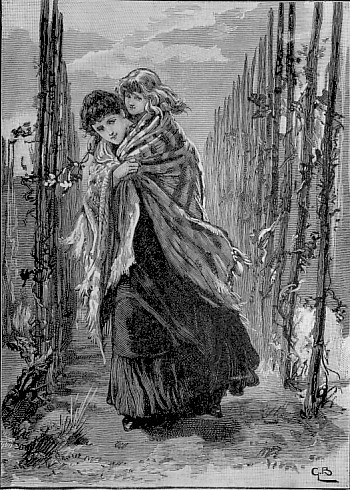

I turned it towards the entrance of our little tent, and

there I saw in the distance Frances walking between the hop-poles,

carrying little May. She also was enveloped in her scarf of

shepherd's plaid, and she had wound it gipsy-like about herself and

the child, so that only the merry little face peeped out over her

shoulder, for she was carrying her pick-a-pack; and I shall not soon

forget how pretty they looked as they came towards us, through the

lengthening perspective of the hop-poles.

May had the sweetest little voice possible; Frances had

taught her to sing several simple songs, and used to sing second to

her; now her high childish notes, so clear and pretty, sounded like

fairy bells in the air, while the deep tones of Frances' contralto

voice, though fine, were not so audible at that distance.

'Pretty little May,' said Caroline, in a regretful tone; 'how

seldom one has an opportunity of getting her to play with! I

think Frances really does usurp her rather too much.'

I cannot describe how much this speech grated upon my

feelings. Frances had never refused to give up the child when

any of the girls had wished to play with her; but seldom had

Caroline wished for her, for she was not naturally fond of children.

'I could not think where you all were,' exclaimed Frances,

stopping before the opening of our tent.

'No,' said May, repeating her words; 'we could not tink

where you all were.'

'Comical little parrot,' said Caroline; 'just put her down,

Frances, and let her come in here.'

'Yes; I want to get into that funny little house,' said May.

Accordingly Frances began to unwind herself and the child, and

finally set her down in the very midst of us, all warm and rosy

after her ride.

'Take care of her,' said Frances, addressing us generally,

'and mind she does not get her feet damp in coming home.'

'I'll carry her in,' said Caroline.

'Very well, if you will undertake her, I shall go,' remarked

Frances; 'for I am rather behind-hand with my German.'

So Frances nodded, and went her way; little May was left with

us, and very droll and amusing she was, till she began to grow tired

of the tent, and then she said she wanted to go in, she wanted to

find her Miss Christiana Frances.

'What do you want with her?' said Caroline; 'look at me, am

not I quite as pretty as Frances?'

May laughed scornfully, as if quite amused at the notion that

any one could be so pretty as Frances. 'No,' she said, 'you're

not half such a pretty lady. I want to go.'

Though she was a mere baby, Caroline was evidently annoyed at

this uncomplimentary speech.

'I hope a certain individual does not try to set this little

thing against me,' she said, in a doubtful tone.

'The idea!' I exclaimed, almost as scornfully as little May

had done; 'how can you lend your mind to such a wild fancy,

Caroline? Why should she try to set her against any one; she

is quite above it; and besides, the child of course prefers

her so infinitely to any of us, that I am sure she never has the

slightest cause for any feeling of jealousy.'

'You are warm, my little Sophia,' said Caroline; but this

time I did not feel ashamed.

'Besides, Caroline,' observed one of our school fellows, who

was by no means aware of the dangerous ground she was treading on,

'why, above all people, should she try to set her against you, who

never interfere with her by any chance, never want to have the

child, and scarcely ever take any notice of her?'

'Pooh!' said Caroline, impatiently.

'I want to go,' repeated May, who was now patting Caroline's

cheek, by way of attracting her attention.

'What for?'

'I want my Miss Christiana Frances; and she said she would

open the drawer to-day, and let me look in it.'

'What drawer?' inquired Caroline.

Upon this I explained that May had often asked to see her

ayah's gowns, bangles, etc., but that Madame had not permitted this

hitherto; now her leave had been obtained, and Frances was going to

show them to her.

'Oh,' said Caroline, whose natural disinclination to trouble

herself with children was still strong within her, though she

evidently wished just now, for obvious reasons, to stand well with

little May. Well, I suppose I must take this child in, as I

promised;' and she rose, half reluctantly, saying, with a

half-smile, 'What little plagues children are!'

'And so is ladies great plagues,' exclaimed May; and then,

delighted with her repartee, she repeated it with fits of baby

laughter; and was carried off by Caroline, vociferating that ladies

were great plagues.

I do not know that she was more droll and shrewd than many

children of her age, but as she certainly was not much more than

half their size, she seemed incomparably more so; and to hear such a

little atom bandy jokes with us, as she often did, was one of the

most comical things possible.

CHAPTER V.

CAROLINE'S WILFULNESS.

SO little May was

carried off by Caroline, and we stayed awhile longer in our tent,

the day being a half-holiday. I remember that we discussed the

motives and conduct of Caroline in having avoided the mention of

Frances as a friend to May, in writing to the child's mother; and

that most of us excused her, or attempted to show that it was purely

accidental this silence. After awhile we dispersed, the others

to their birds in the coach-house, and I to my room, still called

the nursery; on entering I found Caroline and little May there, and

to my surprise saw that the chest of drawers, which contained the

ayah's possessions, had been opened, and that the contents were some

of them scattered on the chairs, the floor, and the beds. May,

with a wistful expression, which I had not seen on her face for a

long time, was gazing earnestly into an open drawer, and Caroline

was curiously examining the different articles.

'How did you get these drawers opened?' I exclaimed.

'Oh, they are quite common locks,' said Caroline. 'I

took a key from one of the drawers of the other chest and put it in,

and it opened without any difficulty.'

'But will Frances like your showing the things while she is

away?' I inquired. 'I know that Madame gave her the key, with

many directions about showing the things very cautiously, for fear

of exciting the child.'

Caroline looked a little alarmed, but answered, 'Then if

Frances expects to be present when they are shown, she should not

keep the poor child waiting so long. Madame gave her the key

as soon as morning lessons were over, and she has left the child,

and does not come to open the drawers; so as the little creature

said she wished to see themII undertook to show them to her.'

I replied that Frances was in the school-room, doing a German

exercise, and probably did not know that May was come in; and I

wondered that Caroline should not have called Frances, rather than

have at once obeyed the caprice of the child, who was, I observed,

though saying nothing, in highest state of excitement, the very

state that Madame vas solicitous by all possible means to avoid.

'I cannot get these things over my hands,' said Caroline, who

had taken up the silver bangles that the ayah had worn; what small

hands and wrists that woman must have had!'

I drew near and looked at the white muslin banyans or

jackets; the wide paunjammahs, which form part of the dress of her

order, and are sometimes made, as they were in this instance, of

rich Benares silk, the curious tortoise-shell combs, which she had

worn in her hair, and the long scarfs or veils of muslin which she

used to throw over her head and shoulders. I saw also the Soam

pebbles, the small silver pawn-box that she had used; for she was

very, very fond of chewing pawn, the rosare, or fringed cotton

quilt, on which she had sat while engaged in shampooing her little

beebee, a purse full of rupees, many strings of cowries, a small

six-sided box, made of straw, and ornamented at the top with a

representation of the cheel, or Brahminee kite, beautifully wrought

on it, also in straw; this box was filled with strange little pieces

of metal, of various shapes and sizes, and I supposed them to be

charms.

Besides all these things, and many more, which I have

forgotten, there were lying on the beds some beautiful jindilly

muslins, gauzes, pieces of striped Benares silk, small Indian scarfs,

grass handkerchiefs, Delhi shawls, pieces of kinquab (a superb kind

of Indian silk), a Trichinopoly chain, a Bombay workbox, chains,

bracelets, agates, and gold and coral ornaments, which had doubtless

been given into the care of the faithful ayah, for the child's use

as she grew older.

I know not what visions of infancy, or what distinct

recollections of the dead ayah and her distant parents, the sight of

these things may have awakened in the breast of little May, but she

continued to gaze at them like one fascinated, till Caroline

happened to say, 'What a curious smell there is about everything

that comes from the East! it is not sandalwood. What is it?'

'I do not know,' I replied; 'but I noticed it about all May's

clothes at first, and the ayah seemed always to waft it as she

walked. It must be some kind of spice.'

Caroline had put on a Benares silk slip of widely striped

silk, she had drawn round her one of the Indian shawls, it looked

very well on her slender form, and she was just completing her

costume, by fastening a muslin veil on her head, when the child,

attracted by our voices, turned round, and starting at the sight of

her, laughed at first, and held out her arms, but in another moment

she was evidently frightened, and began to scream most violently.

Caroline, who did not know how thoroughly the child was

excited, hoped to quiet her with a few kisses, and when these

failed, she first scolded, then entreated, but all to no purpose;

then being afraid of being seen by Madame, whose approval of what

she had done was doubtful, she ran to the drawers, flung them open,

and began to throw in the costly articles which she had so

unceremoniously taken from their concealment; but her purpose was

not wholly accomplished when Frances, attracted by the screams of

her nursling, flew into the room, and breathlessly demanded to know

what was the matter.

Caroline, discovered dressed in this strange costume, in

another person's room, and proving herself so unfit for the office

she had taken upon herself, was so angry, and so ashamed of her

ridiculous position, that she would not say a word, and I was

obliged to explain the matter as well as I could in the interval of

little May's piercing screams.

'I did not know you had brought May in,' said Frances, rather

coldly, and at the same time drawing the key from her pocket.

Caroline neither looked at her nor made any answer. 'I was

perfectly ready to show these drawers to her,' she continued; and

then added firmly, 'May, if you are not quiet I shall be exceedingly

angry.'

'Poor little thing!' exclaimed Caroline, indignantly; 'how

can you speak so crossly to her? don't you see that she cannot

help sobbing? she has no power to prevent it.'

'Yes, she has,' said Frances, addressing herself more to the

child than to Caroline, and speaking steadily, but not unkindly.

'May can stop, and she must; she will be extremely ill if she goes

on screaming in this way. May, do you hear me?'

The child, awed by the unusual manner and expression of

Frances, tried to do as she was bid, and would no doubt have

succeeded, being assisted by her surprise, if Caroline had not

murmured some excuses, remarking, most injudiciously, 'She may stop

for a moment, but she is sure to begin again. I know she

will.'

Of course, upon this the child did begin again, and Frances

instantly took her up, carried her out of the room, and shut the

door behind her.

There was both indignation and dignity in her manner as she

did this, and if Caroline felt herself reproved, it was probably no

more than Frances intended.

'Insolence!' exclaimed Caroline, 'insolence! What right

has she to assume those miserable airs of superiority over me,

carrying off May as if my presence was improper for her, and

treating me like an ignorant child? Insolence! but I will

have her yet I'll have her back again, even if I have to appeal to

Madame. Frances, indeed; what is she that she is to thwart me,

and get the upper hand in everything? I will enter the lists

with her, and we shall soon see who will win. May shall be my

child again before she is a fortnight older.' And, to my great

surprise, she burst into a passion of tears, and hurried to little

May's bed, laying her head down on the pillow, sobbing and covering

her beautiful eyes with the ayah's muslin veil.

I did not at all suppose that she was serious when she spoke

of appealing to Madame, and of having the little May back again, for

she was too indolent, I thought, to desire seriously a charge that

was sure to be so troublesome; I therefore looked on her speech as

an outbreak of mingled indignation, mortification, and passion.

And, when she threw herself on the bed, I could not help feeling

amused; for I thought it childish in her to have a fit of crying,

and show her temper so openly, because she had been vexed.

Most of the girls, I thought, would have been too proud for such an

exhibition; and I looked on very composedly, wondering what would be

done next, till presently the pretty way in which she bemoaned

herself, wishing she had never come to this place this sorrowful

place where it was never really warm, and where the people were as

cold as the weather; where no one understood her, and no one really

loved her; declaring that she was the most unhappy person possible,

and that no half-holiday had ever before been so sorrowful, worked

on my feelings to such a degree, that before I knew what I was

about, I was at her side, begging her to be comforted, and was

caressing her, quite forgetting whether she was right or wrong, and

was lifting up her face, and entreating her to be comforted.

'You used to love me before Frances came,' sobbed Caroline,

'but now now you always take part with her.'

I was so completely beguiled, that I thought of nothing but

how to comfort her, and only answered that I loved both very much,

and hoped she would forget this little scene, and be friendly

towards Frances.

Caroline laid her head on my bosom, and, after a great great

deal more comforting, caressing, was induced to rise, dry her eyes,

and smile again. She stood up, and with my help, divested

herself of the rich silken petticoat, the Indian shawl, and the

ayah's veil, which she had fastened on with some long silver pins,

probably intended for that purpose. Then she walked to the

glass to arrange her hair, still looking very pensive; but her first

remark, on seeing herself therein reflected, struck me as so very

irrelevant, and so completely beneath the dignity of such a heroine

in distress as she had just been enacting, that I could not help

bursting into a sudden laugh.

'Well, I don't look much worse for my crying fit,' was the

remark in question; 'but if I were Frances, I would never cry at all

it really swells up her eyelids, and makes her nose so red, that

she looks quite ugly after it. What can you be laughing at,

Sophia?'

'I cannot help it.'

'You are not laughing at me, surely? you are, I believe!

What is the reason?tell me, this instant, you little quiz.'

'Because as people are not supposed to cry if they can help

it, or unless they are really in sorrow, it seemed so droll to

suppose that they consider whether it will be unbecoming or not, and

act accordingly.'

'Ah! one ought to be more cautious what one says to you,

presidentess; such a straightforward, simple person as myself cannot

get on with you at all; you are always weighing and criticising.

This glass hangs in a very bad light!'

'Caroline, I want to say something to you.'

'Well, say it, then.'

'You think I observe my friends too closely. I must

tell you something that I have observed about you.'

'If it is an agreeable thing, you may.'

'But it is not an agreeable thing altogether, yet as it

concerns me as well as yourself, I must tell you, because not

telling it sometimes makes me feel as if I were deceitful.'

'Does it make you feel as if you were blushing violently?

because you are.'

'Well, I do not care; I shall tell you notwithstanding.'

'I agree with you that you are deceitful, presidentess; for

you say you don't care, and you do. You shan't tell me.'

So saying, Caroline walked up to me, and laying her hands on my

shoulders, looked into my eyes and laughed, repeating, 'You shall

not tell me; I dare you to it.'

'You have a habit,' I began; but Caroline quickly stopped my

mouth by clapping her hand upon it, exclaiming, 'Oh, you tiresome

girl, I cannot bear your scruples, and your principles, and your

things; you must have caught them of Frances; you were such a

charming little creature before she came.'

She would not remove her hand till I ceased to make attempts

at speaking, and then she pathetically begged me to help her in

putting away the Indian articles, which I accordingly began to do,

and they supplied us with conversation till the last shawl was

folded, and the last jewel carefully put away. Then Caroline

sat down on the side of the bed with an air of the deepest

consideration, and said to me, 'After all, presidentess, I think I

have a curiosity to hear what you meant to tell me.'

'Perhaps it was that you are, in my opinion, a very

capricious creature.'

'Perhaps it was no such thing; come, tell me, for I like you

to talk confidentially to me as you used to do before that Frances

came. I think there is no one in the house that I feel so fond

of as I do of you.'

'Oh, but you said that to Belle yesterday, that very same

thing; for she repeated it to me in great triumph.'

Caroline laughed, and answered, not a whit abashed: 'Well, I

daresay I felt very fond of her when I said it; but now I want to

hear this; tell me, only mind it is not to be anything

disagreeable.'

'In that case, I am to invent something to tell you, I

suppose; for I told you what I did mean to say was disagreeable.'

'It really is very provoking of you to tease me in this way,'

said Caroline, earnestly, 'when you know that I never can sleep at

night if anything puzzles me.'

I saw she was determined to be told, but my courage failed

me, for I felt more strongly than I had ever done before that

Caroline would never forgive me if I really let her see what grave

faults I had perceived in her character; strange to say, I also felt

more than ever those nameless attractions which had drawn me to her

from the first.

'Come, begin,' she exclaimed, drawing me towards her, and

making me sit by her on the little bed. 'I know it is

something agreeable after all; and if it is not, I shall be in such

a passion.'

She spoke in joke, but did not think how soon it would be

true in earnest.

'I did not like to tell you,' I began, 'because we have been

so affectionate and friendly just now; it was only this, that you

have a habit of making out, at least you seem to take for granted,

whenever we show you how much we love you you have a habit, you '

'Well, come to the point,' said Caroline, laughing, and don't

blush.'

'Why, you seem to take for granted,' I exclaimed, with a

mighty effort, 'that if people love others, they must needs think

them perfect; you think when we are affectionate, at least when I

am, that I entirely approve of what you may have been doing that I

think you quite in the right.'

'If you do love me, you must think me right,' said

Caroline. 'You must take my part in your mind. No one

can love me, and yet see faults in me.'

'Do you see no faults in me?' I ventured to inquire.

'O yes!' was the frank rejoinder, 'but then that's

different. I see faults sometimes, no doubt.'

'But I, loving you more than you love me, ought not to see

any in you; is that it?' I asked.

Caroline laughed again; but I had, perhaps, come so near to

what she had meant, when she made that incautious speech, that she

felt embarrassed, and only repeated that she had always accustomed

to have people like her, and not see her faults; and she was sure if

I loved her I could not see them.

'But,' I said, 'I beg your pardon, I often see them and yet

sometimes for want of courage, and sometimes because you appear to

expect it, and often remark that a friend is always

short-sighted to defects, I have let you think I considered you

quite right when I have blamed you in my heart; and you are often so

affectionate to me that I am sure you do not know what I sometimes

think.'

'If I understand you aright,' said Caroline, 'I suppose this

is your way of telling me that you do not care for me as much as you

have often pretended to do.'

'If you think so,' I replied, 'you do not understand me at

all.'

It was one of Caroline's peculiarities to be remarkably

sensitive to blame; she could not bear to be found fault with in the

most trivial matter. She now looked surprised, and even

coloured, a thing that rarely occurred with her. 'I don't

know what you mean,' she said, 'unless you give me an instance.'

I answered, in some trepidation, 'I thought it wrong in you

to express a determination to get May away from Frances, yet I tried

to comfort you when you were so vexed, and you thought, I believe,

that I approved.'

Caroline had pushed me slightly from her, and withdrew her

arm as I began to speak; and the moment I was done, 'Express a

determination!' she repeated, passionately. 'Yes, I do express

a determination; I will strive with Frances, by all means, open and

underhand; she shall not treat me as she has done for nothing.

May, I will have. Frances may do without her as well as she

can.'

The point in discussion was already lost sight of between us,

and the old grievance recurred to. 'Then you will be very

wrong, and very unkind,' I exclaimed, in great heat. 'You will

be more than unkind, you will be wicked.'

'Wicked!' cried Caroline, starting up with sparkling eyes.

'What do you dare to say? What do you mean? How unkind?

How wicked?'

'It would be wicked,' I repeated, 'because it would be

stealing.' I said this word in a very low tone.

Caroline caught it up sarcastically, and repeated it with a

bitter laugh. 'Stealing! as if that tiresome, plain,

uninteresting child was worth stealing.'

'The more unkind, then,' I exclaimed, 'if you think so, to

steal her from Frances, to whom she is so lovely, so interesting,

and so precious. I say, it will be stealing, and if you do it

intentionally, as you say you mean to do, it will be quite as

wicked, and quite as mean, as it would be to steal one of those

Indian shawls, or to steal May's diamond locket that her papa left

for her.'

'Insolent girl! Insolent creature!' cried Caroline,

drawing herself up to her full height, and looking down on me as I

sat nervously on the side of the bed. 'And so, I suppose indeed

I can have no doubt,' she added with ineffable scorn, 'that this

conversation this pleasing and affectionate conversation, will be

repeated to Frances Frances, whom you can esteem no doubt of it

at all. I hope you will not forget to mention that you

yourself confessed to being deceitful, and if you will also say that

I quite agree with you, it will add to the obligation.'

'I shall not mention a word of it,' I replied, swelling with

pride and mortification; 'it has been strictly confidential, and I

can only wish now, very sincerely, that it might have ended

differently.'

Caroline was walking about the room in such a passion as I

had never seen her in, though she was naturally of a very excitable

disposition; her eyes sparkled, her cheeks were suffused with

crimson, her whole figure seemed to dilate; and she replied, in a

tone of the bitterest contempt, that, for her part, she wondered how

such a conversation could end otherwise than by a cessation of all

friendliness on the part of the injured party; that she was

thankful for this dιnouement,

and for the avowal of my sentiments; adding, in a very galling

manner, that she had quite long enough nourished a serpent in her

bosom; 'and as to this strictly confidential conversation,' she

repeated, 'it may be kept to yourself for a time; but I mistake you

and your sincerity very much if Frances does not know the whole of

it within a week.'

'I shall not repeat a word of it to her, either now or at any

future time,' I repeated, passionately.

'As you please,' Caroline began, and paused suddenly in her

excited pacing of the chamber; presently adding, more calmly, though

still in an angry tone, 'I never asked you to make such a solemn

and deliberate promise; but since you have thought proper to

do so, of your own accord, I suppose you have some reason for it.'

As she went on with this sentence, she spoke more slowly, and

with unusual emphasis, as if she wished fully to impress on my mind

that I had made this promise, and also as if its importance to

herself unfolded itself more and more. I was forcibly struck

by this change, and this sudden coolness, where there had been so

much passion. I perceived that now she had this promise she

was quite at her ease, and it pained me inexpressibly to perceive

that no part of her excitement and agitation had arisen from her

quarrel with me, and this unceremonious breaking up of our

friendship, but only from the fear of my, repeating her words; and I

was so vexed, and so heart-sore, at the utter loss of her affection,

that though I could now esteem her less than ever, I could not help

shedding some very bitter tears when I saw her take up a fan, and

walk about near the windows to cool herself, then go to the glass,

smooth her hair, and arrange her ribbons with elaborate care, and

finally walk out of the room without deigning to bestow on me one

look or one word.

Many sorrowful feelings combined to make me glad to remain

alone for awhile after Caroline had left me; I reproached myself for

the clumsy way in which I had managed my part in the conversation,

and wept with wounded affection, and perhaps also injured pride,

and, like Caroline, I thought this was the most miserable

half-holiday I had ever passed. At length, when the redness

that Caroline had spoken of was faded from my features, I stole

down-stairs, and perceiving, through the staircase window, that most

of the girls were still in the garden, I took my way to the

schoolroom, that I might be alone, and there I saw what?

Why, Caroline and Frances sitting together, doing a piece of

bead-work, and talking in the most amicable manner possible!

Remarkable sight! I was too bashful to come close, but

sat down at the first desk. Caroline had perhaps made some

kind of apology to Frances; for the latter looked pleased, and

little May sat at her feet, quite happy again, and trying to thread

some very large beads, but continually scattering them, and

scrambling under the table to pick them up. At last, taking

advantage of a pause in the discourse, she leaned against Frances's

knee, and exclaimed, without any preface, 'But when is she to come?

she is such a long time coming.'

'I told you,' said Frances, 'that she should come whenever

you could count a hundred, without making a mistake.'

'Will she have blue eyes?' proceeded May; 'will she have blue

eyes, Miss Christiana Frances?'

'Blue eyes and flaxen hair,' replied Frances, 'and two little

pink shoes that will take on and off.'

'Oh! I do want her so much.'

'What is the child talking of?' asked Caroline.

'Of a wax doll that I have promised her when she can count a

hundred, for she has been very idle lately; and when she has learned

this one thing, not before, I shall give her the doll for a reward.'

'Not before,' sighed little May; 'and her frock is to be a

white frock, Miss Christiana Frances? Oh! I wish she

would come to-night.'

Frances smiled. 'Well, begin then,' she said, 'one,

two, three, and if you go on properly to a hundred she shall come

to-night.' By this she convinced me that the doll was already

in her possession, and ready to be given at a moment's notice.

I am very much mistaken if the same idea did not strike Caroline,

for she also smiled and said, 'I never should have patience

to keep back anything that I was teased for.' This she said in

French, and Frances answered, 'I have passed my word.'

May began to count, Frances took her up on her knees; the

little creature laid her head on her bosom as on a place of tried

security, and when she reached sixteen she stopped, and had to be

prompted, and then Frances discovered that her feet were cold, and

took off her shoes to warm them, and a great deal of kissing and

caressing went on between them; upon seeing which, a cloud passed

over Caroline's brow.

'Let me warm them for you,' she presently said.

'Oh, no, thank you!' said Frances; 'I could not think of

troubling you.' She spoke exactly as she might have done if

May had been her sister, her natural charge. Now, May, go on.'

'Shall she come, then, when I can count up to trenty?'

pleaded the child.

Frances shook her head.

'But mayn't she come, if I kiss you a great many times?' said

May suddenly, as if a bright idea had struck her.

'She may come when you can count a hundred,' repeated

Frances.

'Then I will do it right, Miss Christiana Frances,'

exclaimed May, with a mighty sigh, and she immediately counted up to

nineteen without once stopping even to take breath.

All the remainder of that evening Caroline was particularly

friendly to Frances. The next day Madame, having occasion to

drive into the town, invited Caroline and another of the pupils to

accompany her. I happened to hear Madame ask them whether they

wished her to buy anything; for, when this was the case, she always

chose to know it beforehand.

I was standing close to Madame at the time, holding her

gloves, and therefore I could not fail to hear the answers; one I

have forgotten, the other struck me forcibly, it was Caroline's, and

given in a particularly low voice: 'She wished to buy a doll,' she

said.

CHAPTER VI.

CAROLINE'S INTERFERENCE.

I REMARKED, at

the conclusion of my last chapter, that Madame drove away in the

pony-chaise with Caroline, and I soon forgot my speculations about

the doll, which the latter had expressed a wish to purchase.

How did I contrive so easily to forget a thing in its nature so

interesting? Why, my dear readers, I think at this distance of

time I can venture to confide to you, that having then reached the

ripe age of fifteen, I was deeply engaged in the writing of a grand

epic poem, upon which I worked on all holidays and half-holidays.

Some of my school-fellows gave me their select opinions upon

it, when I afterwards read it to them in the hayloft, over the place

where our caged birds were kept; they said they thought it very

fine; they also said they did not exactly understand it; I am happy

to say that I had the strength of mind to burn it shortly after

leaving school.

On this half-holiday, as the pony-chaise disappeared, I crept

into the said hayloft, and then taking out my pocket ink glass and

my little folio, began to write; and was deep in the distressing

scenes of the death of my hero, whom I was causing to die in the

most affecting manner, weeping abundantly myself over the cruelty of

his enemies, and quite sobbing at the noble courage and resignation

that I was making him display, when I thought I heard the least

possible creaking behind me, and the least possible soupηon

of a gentle titter.

Perched as I was upon the square-cut blocks of hay, crying

piteously, so that the tears blotted my page, my bonnet lying beside

me, and the whole loft radiant with dusty sunbeams, could anything

be more ridiculous than my position, or, unfortunately, more

conspicuous, if any of the girls were watching me from the top of

the ladder-like stairs? To say that I blushed till the very

back of my neck was rosy, would but half describe my glowing shame.

I did not dare to turn round, and was almost wishing that my

noble hero had never been invented, when suddenly, 'All hands pass

pocket-handkerchiefs?' cried a voice that I knew, 'to dry the Muse's

tears.'

We were reading just then in class the history of the last

naval war, and used to adopt its sea phrases as well as we could.

Instantly a pocket-handkerchief, rolled up like a bail,

struck me on the back; another flew over my head; more, more; there

were eight of them flying about me; and after this shower the owners

rushed in pell-mell, and flung themselves on the hay in convulsions

of laughter some had their shoes in their hands, having taken them

off below that they might ascend more gently; some kissed and

apologized; some with mock gravity wiped my cheeks, and then tried

to read the blotted manuscript, adroitly substituting pieces of the

Italian grammar where it baffled their efforts at deciphering.

They were all in ecstasies at my discovered absurdity; and as

for me, when the first moments of shame were over, I laughed more

than any of them, and was extremely anxious to disavow my poetic

fervour, and to make humble apologies for having deserted those

gifted spirits, my school-fellows, for the sake of writing verses in

a hayloft.

We went into the garden and amused ourselves in various ways,

till the afternoon suddenly clouding, we betook ourselves to the

house; the elder girls withdrew to the dining-parlour; the little

ones to the schoolroom, and I only of the upper class went with

them, for I was helping them to make a tiny grotto, which was to be

presented to Madame on her birthday, and the shells for which we

sorted on the window-sills of this long room,

We were all kneeling on the floor, sedulously intent on our

sorting, with the exception of little May, whom Frances had just

sent in, and who was playing about the room, jumping over the

hassocks, when the pony-chaise drove up, and immediately after

Caroline came in, with a large silver-paper parcel in her hand.

Now I have before adverted to the fact that I was at that

time remarkably small for my years; consequently, when Caroline

glanced round, I can scarcely doubt that she overlooked my

individual presence, only thinking that all the little ones were

there at their play, for I have since believed that if she had seen

me, she would have used more caution in what she said.

She was blooming with air and exercise, and her lovely hazel

eyes sparkled as if she were excited. 'Where is May?' she

inquired.

Several fingers pointed under the table, and presently out

crept May, shaking back her extremely long curls, and bearing a

hassock in her arms. The little creature was flushed with the

effort. Caroline smiled pleasantly on her, and said, 'Where do

you think I have been, you tiny thing?'

May answered, in a matter-of-fact way, that she knew.

'Oh, then, you don't want to hear anything about it?'

observed Caroline; 'nor to be told what I have got in this parcel?'

May, upon this, put down the hassock, and came close to where

Caroline had seated herself on a form.

'You cannot guess what is inside there?' asked Caroline,

laying her hand upon the softly rustling paper.

'I can guess,' cried an eager looker-on from the window-seat.

'And I am sure I know,' exclaimed another. The folded toy was

as lovely a doll as ever enriched the eyes of a little mortal.

'Look at it,' said Caroline, 'I will just undo a piece of the

paper.' She did so, and displayed a flaxen-haired beauty, with

smiling red lips, and gay blue eyes.

'A doll!' said May, gravely laying one finger on its face, in

her own peculiarly infantine manner.

'She is nearly as tall as you are,' said Caroline; 'I wonder

who she is for?'

'I wonder who she is for?' repeated the fascinated child,

looking down on the doll's face.

'Well, I will tell you,' replied Caroline; 'here, take her,

she is for you.'

May looked at her, and then putting her hands behind her,

said wistfully, 'My doll's not coming today, because I didn't count

a hundred; perhaps she's coming to-morrow.'

'This is your doll,' persisted Caroline, laughing; 'is she

not a beauty?'

'But I only did it right up to eighty-one,' said the child;

'and my Miss Christiana Frances said my doll might not come till

to-morrow.'

'You silly little thing,' said Caroline, colouring and

laughing; 'look, this is a doll that I am going to give you; it is a

present from me; when you can count a hundred, Miss Christiana

Frances can give you another doll, if she likes, but this is yours

now here, I bought it for you; kiss me and take it.'

May seemed now to understand, and with a rapturous laugh she

sprung to Caroline, and threw her arms about her neck and kissed

her. Caroline took her up and gave her the great doll, and

praised it, pointing out its beauty and its good qualities.

The child blushed for joy. 'Are you sure she is my doll?' she

exclaimed; 'and what will Miss Christiana Frances say?'

Caroline made an impatient gesture, and replied Miss Black

can give you a doll when she likes, May, and I can give you one when

I like: it does not at all matter to me what other people do; and

look, here is something more for you: so saying, she produced a

paper of sugared almonds. 'There,' she continued, 'these are

for you, all for you, because you are the youngest little girl in

the school, and you are my little pet. Kiss me.'

May readily did as she was desired, and forthwith opened the

tempting paper, and began to eat an almond.

'Nannette has a pocket in her best frock,' she observed to

her new friend.

'Would you like to have one in your frock to keep your

almonds in?' asked Caroline.

'O yes!' replied May, confidingly; 'and I shall ask my Miss

Chris-tiana Frances to make me a little pocket, and perhaps she

will, if I'm good.'

'If you're good! poor little thing,' said Caroline, with

ill-timed pity; 'well, May, I will make you a pocket, for little

girls cannot always be good.''

'No,' said May, simply; 'I wasn't good when I sucked the

paints.'

'What paints?' asked Caroline.

'Those little paints in my Miss Chris-tiana's box; I thought

they were chocolates, and I bit them.'

'Yes, and she made her lips all blue,' said Nannette,

breaking into the conversation, 'and when Massey washed her, the

soap got into her mouth.'

This cheering conclusion to the affair being brought forward,

May observed, in a deeply reflective tone, 'I shall not suck the

paints any more.'

Caroline laughed. 'Well, May,' she said, 'you may go

and fetch my work-box, and I will make you a pocket now.'

May's delight was very great. She ran for the box, and

a little pocket was set in hand instantly Caroline talking

pleasantly while at work about the doll, and how she would make a

frock and a hat for her, while May prattled in a confiding way that

she had not shown her before.

'There,' she said, when the pocket was sewed in, 'now,

whenever you want anything, little one, you may come to me, and I

daresay I shall be able to do it for you.'

'Yes,' said May, 'when my Miss Chris-tiana Frances hasn't

time:' and then, indicating the kind of thing she generally wanted

doing, she said, 'Can you play at Loto, and draw cats and two little

kittens, Miss Baker; and can you draw pigs with curly tails?'

'Oh, I can do a great many things for little girls who love

me,' said Caroline.

'I love you,' responded May.

'Are you sure you do?' asked Caroline.

'O yes, I love you very much indeed to-day,' replied the

frank little creature, and added, 'I didn't love you any of the

other days.'

'Do you love me as much as Miss Christiana Frances?' asked

Caroline.

May laughed as if she considered the question absurd, but

presently said, in a consoling tone, 'I can't yet, but perhaps I

will soon.'

'You small oddity!' said Caroline, 'do you remember seeing

that pretty little locket that I wear sometimes?'

'O yes,' answered the child. 'You mean that one that I

opened when I saw it in your box, and you slapped me, and said I

wasn't to touch it.'

This was rather an awkward recollection, but Caroline passed