|

[Previous Page]

Two Ways of telling a Story.

WHO is this?

A careless little midshipman, idling about in a great city, with his

pockets full of money.

He is waiting for the coach: it comes up presently, and he

gets on the top of it, and begins to look about him.

They soon leave the chimney-pots behind them his eyes wander

with delight over the harvest fields, he smells the honeysuckle in

the hedge-row, and he wishes he was down among the hazel bushes,

that he might strip them of the milky nuts; then he sees a great

wain piled up with barley, and he wishes he was seated on the top of

it; then they go through a little wood, and he likes to see the

chequered shadows of the trees lying across the white road; and then

a squirrel runs up a bough, and he cannot forbear to whoop and

halloo, though he cannot chase it to its nest.

The other passengers are delighted with his simplicity and

childlike glee; and they encourage him to talk to them about the sea

and ships, especially Her Majesty's ship The Asp, wherein he

has the honour to sail. In the jargon of the sea, he describes

her many perfections, and enlarges on her peculiar advantages; he

then confides to them how a certain middy, having been ordered to

the mast-head as a punishment, had seen, while sitting on the

top-mast cross-trees, something uncommonly like the sea-serpent—but,

finding this hint received with incredulous smiles, he begins to

tell them how he hopes that, some day, he shall be promoted to have

charge of the poop. The passengers hope he will have that

honour; they have no doubt he deserves it. His cheeks flush

with pleasure to hear them say so, and he little thinks that they

have no notion in what "that honour" may happen to consist.

The coach stops: the little midshipman, with his hands in his

pockets, sits rattling his money, and singing. There is a poor

woman standing by the door of the village inn; she looks careworn,

and well she may, for, in the spring, her husband went up to London

to seek for work. He got work, and she was expecting soon to

join him there, when, alas! a fellow-workman wrote her word how he

had met with an accident, how he was very ill, and wanted his wife

to come and nurse him. But she has two young children, and is

destitute; she must walk up all the way, and she is sick at heart

when she thinks that perhaps he may die among strangers before she

can reach him.

She does not think of begging, but seeing the boy's eyes

attracted to her, she makes him a curtsy, and he withdraws his hand

and throws her down a sovereign. She looks at it with

incredulous joy, and then she looks at him.

"It's all right," he says, and the coach starts again, while,

full of gratitude, she hires a cart to again her across the country

to the railway, that the next night she may sit by the bedside of

her sick husband.

The midshipman knows nothing about that; and he never will

know.

The passengers go on talking—the little midshipman has told

them who he is, and where he is going; but there is one man who has

never joined in the conversation; he is dark-looking and restless;

he sits apart; he has seen the glitter of the falling coin, and now

he watches the boy more narrowly than before.

He is a strong man, resolute and determined the boy with the

pockets full of money will be no match for him. He has told

the other passengers that his father's house is the parsonage of Y―,

the coach goes within five miles of it, and he means to get down at

the nearest point, and walk, or rather run over to his home, through

the great wood.

The man decides to get down too, and go through the wood; he

will rob the little midshipman perhaps, if he cries out or

struggles, he will do worse. The boy, he thinks, will have no

chance against him; it is quite impossible that he can escape; the

way is lonely, and the sun will be down.

No. There seems indeed little chance of escape; the

half-fledged bird just fluttering down from its nest has no more

chance against the keen-eyed hawk than the little light-hearted

sailor boy will have against him.

And now they reach the village where the boy is to alight.

He wishes the other passengers "good evening," and runs lightly down

between the scattered houses. The man has got down also, and

is following.

The path lies through the village churchyard; there is

evening service, and the door is wide open, for it is warm.

The little midshipman steals up the porch, looks in, and listens.

The clergyman has just risen from his knees in the pulpit, and is

giving out his text. Thirteen months have passed since the boy

was within a house off prayer; and a feeling of pleasure and awe

induces him to stand still and listen.

"Are not two sparrows (he hears) sold for a farthing? and one

of them shall not fall on the ground without your Father. But

the very hairs of your head are all numbered. Fear ye not,

therefore, ye are of more value than many sparrows."

He hears the opening sentences of the sermon and then he

remembers his home, and comes softly out of the porch, full of a

calm and serious pleasure. The clergyman has reminded him of his

father, and his careless heart is now filled with the echoes of his

voice and of his prayers. He thinks on what the clergyman

said, of the care of our heavenly Father for us; he remembers how,

when he left home, his father prayed that he might be preserved

through every danger; he does not remember any particular danger

that he has been exposed to, excepting in the great storm; but he is

grateful that he has come home in safety, and he hopes whenever he

shall be in danger—which he supposes he shall be some day—he hopes

that then the providence of God will watch over him and protect him.

And so he presses onward to the entrance of the wood.

The man is there before him. He has pushed himself into the

thicket, and cut a heavy stake; he suffers the boy to go on before,

and then he comes out, falls into the path and follows him.

It is too light at present for his deed of darkness, and too

near the entrance of the wood, but he knows that shortly the path

will branch off into two, and the right one for the boy to take will

be dark and lonely.

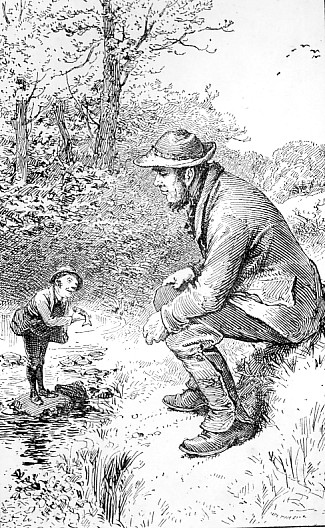

But what prompts the little midshipman, when not fifty yards

from the branching of the path, to break into a sudden run? It

is not fear, he never dreams of danger. Some sudden impulse,

or some wild wish for home, makes him dash off suddenly after his

saunter, with a whoop and a bound. On he goes, as if running a

race; the path bends, and the man loses sight of him. "But I

shall have him yet," he thinks; "he cannot keep this pace up long."

The boy has nearly reached the place where the path divides,

when he puts up a young white owl that can scarcely fly, and it goes

whirring along, close to the ground, before him. He gains upon

it; another moment, and it will be his. Now it gets the start

again; they come to the branching of the paths, and the bird goes

down the wrong one. The temptation to follow is too strong to

be resisted; he knows that somewhere, deep in the wood, there is a

cross track by which he can get into the path he has left; it is

only to run a little faster and he shall be at home nearly as soon.

On he rushes; the path takes a bend, and he is just out of

sight when his pursuer comes where the paths divide. The boy

has turned to the right; the man takes the left, and the faster they

both run the farther they are asunder.

The white owl still leads him on; the path gets darker and

narrower; at last he finds that he has missed it altogether, and his

feet are on the soft ground. He flounders about among the

trees and stumps, vexed with himself, and panting after his race.

At last he hits upon another track, and pushes on as fast as he can.

The ground begins sensibly to descend—he has lost his way—but he

keeps bearing to the left; and, though it is now dark, he thinks

that he must reach the main path sooner or later.

He does not know this part of the wood, but he runs on.

O little midshipman! why did you chase that owl? If you had

kept in the path with the dark man behind you, there was a chance

that you might have outrun him; or, if he had overtaken some passing

wayfarer might have heard your cries, and come to save you.

Now you are running on straight to your death, for the forest water

is deep and black at the bottom of this hill. O that the moon

might come out and show it to you!

The moon is under a thick canopy of heavy black clouds; and

there is not a star to glitter on the water and make it visible.

The fern is soft under his feet as he runs and slips down the

sloping hill. At last he strikes his foot against a stone,

stumbles and falls. Two minutes more and he will roll into the

black water.

"Heyday!" cries the boy, "what's this? Oh, how it tears

my hands! Oh, this thorn-bush! Oh! my arms! I

can't get free!" He struggles and pants. "All this comes

of leaving the path," he says; "I shouldn't have cared for rolling

down if it hadn't been for this bush. The fern was soft

enough. I'll never stray in a wood at night again.

There, free at last! And my jacket nearly torn off my back!"

With a good deal of patience, and a great many scratches, he

gets free of the thorn which had arrested his progress, when his

feet were within a yard of the water, manages to scramble up the

bank, and makes the best of his way through the wood.

And now, as the clouds move slowly onward, the moon shows her

face on the black surface of the water; and the little white owl

comes and hoots, and flutters over it like a wandering snowdrift.

But the boy is deep in the wood again, and knows nothing of the

danger from which he has escaped.

All this time the dark passenger follows the main track, and

believes that his prey is before him. At last he hears a

crashing of dead boughs, and presently the little midshipman's voice

not fifty yards before him. Yes, it is too true; the boy is in

the cross track. He will pass the cottage in the wood

directly, and after that his pursuer will come upon him.

The boy bounds into the path; but, as he passes the cottage,

he is so thirsty, and so hot, that he thinks he must ask the

inhabitants if they can sell him a glass of ale.

He enters without ceremony. "Ale?" says the woodman,

who is sitting at his supper. "No, we have no ale; but perhaps

my wife can give thee a drink of milk. Come in." So he

comes in, and shuts the door; and, while he sits waiting for the

milk, footsteps pass. They are the footsteps of his pursuer,

who goes on with the stake in his hand, and is angry and impatient

that he has not yet come up with him.

The woman goes to her little dairy for the milk, and the boy

thinks she is a long time. He drinks it, thanks her, and takes

his leave.

Fast and fast the man runs on, and, as fast as he can, the

boy runs after him. It is very dark, but there is a yellow

streak in the sky, where the moon is ploughing up a furrowed mass of

grey cloud, and one or two stars are blinking through the branches

of the trees.

Fast the boy follows, and fast the man runs on, with his

weapon in his hand. Suddenly he hears the joyous whoop—not

before, but behind him. He stops and listens breathlessly.

Yes, it is so. He pushes himself into the thicket, and raises

his stake to strike when the boy shall pass.

On he comes, running lightly, with his hands in his pockets.

A sound strikes at the same instant on the ears of both; and the boy

turns back from the very jaws of death to listen. It is the

sound of wheels, and it draws rapidly nearer. A man comes up,

driving a little gig.

"Hallo!" he says, in a loud, cheerful voice. "What!

benighted, youngster?"

"Oh, is it you, Mr. Davis?" says the boy; "no, I am not

benighted; or, at any rate, I know my way out of the wood."

The man draws farther back among the shrubs. "Why,

bless the boy," he hears the farmer say, "to think of our meeting in

this way. The parson told me he was in hopes of seeing thee

some day this week. I'll give thee a lift. This is a

lone place to be in this time o' night."

"Lone!" says the boy, laughing. "I don't mind that;

and, if you know the way, it's as safe as the quarter-deck."

So he gets into the farmer's gig, and is once more out of

reach of the pursuer. But the man knows that the farmer's

house is a quarter of a mile nearer than the parsonage, and in that

quarter of a mile there is still a chance of committing the robbery.

He determines still to make the attempt, and cuts across the wood

with such rapid strides that he reaches the farmer's gate just as

the gig drives up to it.

"Well, thank you, farmer," says the midshipman, as he

prepares to get down.

"I wish you good-night, gentlemen," says the man, when he

passes.

"Good-night, friend," the farmer replies. "I say, my

boy, it's a dark night enough; but I have a mind to drive you on to

the parsonage, and hear the rest of this long tale of yours about

the sea-serpent."

The little wheels go on again. They pass the man; and

he stands still in the road to listen till the sound dies away.

Then he flings his stake into the hedge, and goes back again.

His evil purposes have all been frustrated—the thoughtless boy has

baffled him at every turn.

And now the little midshipman is at home—the joyful meeting

has taken place; and when they have all admired his growth, and

decided whom he is like, and measured his height on the

window-frame, and seen him eat his supper, they begin to question

him about his adventures, more for the pleasure of hearing him talk

than any curiosity.

"Adventures!" says the boy, seated between his father and

mother on a sofa. "Why, ma, I did write you an account of the

voyage, and there's nothing else to tell. Nothing happened

to-day at least nothing particular."

"You came by the coach we told you of?" asks his father.

"Oh yes, papa; and when we had got about twenty miles there

came up a beggar, while we changed horses, and I threw down (as I

thought) a shilling, but, as it fell, I saw it was a sovereign.

She was very honest, and showed me what it was, but I didn't take it

back, for you know, mamma, it's a long time since I gave anything to

anybody."

"Very true, my boy," his mother answers; "but you should not

be careless with your money and few beggars are worthy objects of

charity."

"I suppose you got down at the cross-roads? says his elder

brother.

"Yes, and went through the wood. I should have been

here sooner if I hadn't lost my way there."

"Lost your way!" says his mother, alarmed.

"My dear boy, you should not have left the path at dusk."

"Oh, ma," says the little midshipman, with a smile, "you're

always thinking we're in danger. If you could see me sometimes

sitting at the jib-boom end, or across the main-top-mast

cross-trees, you would be frightened. But what danger

can there be in a wood?"

"Well, my boy," she answers, "I don't wish to be

over-anxious, and to make my children uncomfortable by my fears.

What did you stray from the path for?"

"Only to chase a little owl, mamma: but I didn't catch her

after all. I got a roll down a bank, and caught my jacket

against a thorn bush, which was rather unlucky. Ah! three

large holes I see in my sleeve. And so I scrambled up again,

and got into the path, and asked at the cottage for some beer.

What a time the woman kept me, to be sure! I thought it would

never come. But very soon after, Mr. Davis drove up in his

gig, and he brought me on to the gate."

"And so this account of your adventures being brought to a

close," his father says, "we discover that there were no adventures

to tell!"

"No, papa, nothing happened; nothing particular, I mean."

Nothing particular! If they could have known, they

would have thought lightly in comparison of the dangers of "the

jib-boom end and the maintop-mast cross-trees." But they did

not know, any more than we do, of the dangers that hourly beset us.

Some few dangers we are aware of, and we do what we can to provide

against them; but for the greater portion, "our eyes are held that

we cannot see." We walk securely under His guidance, without

whom "not a sparrow falleth to the ground!" and when we have had

escapes that the angels have admired at, we come home and say,

perhaps, that "nothing has happened; at least nothing particular."

It is not well that our minds should be much exercised about

these hidden dangers, since they are so many and so great that no

human art or foresight can prevent them. But it is very well

that we should reflect constantly on that loving Providence which

watches every footstep of a track always balancing between time and

eternity; and that such reflections should make us both happy and

afraid—afraid of trusting our souls and bodies too much to any

earthly guide, or earthly security—happy from the knowledge that

there is One with whom we may trust them wholly, and with whom the

very hairs of our head are all numbered. Without such trust,

how can we rest or be at peace? but with it we may say with the

Psalmist, "I will both lay me down in peace, and sleep, for thou,

Lord, only makest me dwell in safety!"

――――♦――――

The One-Eyed Servant.

Do you see those two pretty cottages on opposite sides of the

Common? How bright their windows are, and how prettily the

vines trail over them! A year ago one of them was the dirtiest

and most forlorn-looking place you can imagine, and its mistress the

most untidy woman.

She was once sitting at her cottage door with her arms

folded, as if she were deep in thought, though, to look at her face,

one would not have supposed she was doing more than idly watching

the swallows as they floated about in the hot, clear air. Her

gown was torn and shabby, her shoes down at heel; the little curtain

in her casement, which had once been fresh and white, had a great

rent in it; and altogether she looked poor and forlorn.

She sat some time, gazing across the common, when all on a

sudden she heard a little noise, like stitching, near the ground.

She looked down, and sitting on the border, under a wall-flower

bush, she saw the funniest little man possible, with a blue coat, a

yellow waistcoat, and red boots; he had got a small shoe on his lap,

and he was stitching away at it with all his might.

"Good-morning, mistress!" said the little man. "A very

fine day. Why may you be looking so earnestly across the

common?"

"I was looking at my neighbour's cottage," said the young

woman.

"What! Tom, the gardener's wife?—little Polly, she used

to be called; and a very pretty cottage it is too! Looks

thriving, doesn't it?"

"She was always lucky," said Bella (for that was the young

wife's name); "and her husband is always good to her."

"They were both good husbands at first," interrupted the

little cobbler, without stopping." Reach me my awl, mistress,

will you, for you seem to have nothing to do: it lies close by your

foot."

"Well, I can't say but they were both very good husbands at

first," replied Bella, reaching the awl with a sigh; "but mine has

changed for the worse, and hers for the better; and then, look how

she thrives. Only to think of our both being married on the

same day; and now I've nothing, and she has two pigs, and a—"

"And a lot of flax that she spun in the winter," interrupted

the cobbler; "and a Sunday gown, as good green stuff as ever was

seen, and, to my knowledge, a handsome silk handkerchief for an

apron; and a red waistcoat for her good man, with three rows of blue

glass buttons, and a flitch of bacon in the chimney, and a rope of

onions."

"Oh, she's a lucky woman!" exclaimed Bella.

"Ay, and a tea-tray, with Daniel in the lion's den upon it,"

continued the cobbler: "and a fat baby in the cradle."

"Oh, I'm sure I don't envy her that last," said Bella,

pettishly. "I've little enough for myself and my husband,

letting alone children."

"Why, mistress, isn't your husband in work?" asked the

cobbler.

"No; he's at the alehouse."

"Why, how's that? he used to be very sober. Can't he

get work?"

"His last master wouldn't keep him, because he was so

shabby."

"Humph!" said the little man. "He's a groom, is he not?

Well, as I was saying, your neighbour opposite thrives; but no

wonder! Well, I've nothing to do with other people's secrets;

but I could tell you, only I'm busy, and must go."

"Could tell me what?" cried the young wife. "Oh,

good cobbler, don't go, for I've nothing to do. Pray tell me

why it's no wonder that she should thrive?"

"Well," said he, "it's no business of mine, you know, but, as

I said before, it's no wonder people thrive who have a servant—a

hard-working one, too—who is always helping them."

"A servant!" repeated Bella—"my neighbour has a servant!

No wonder, then, everything looks so neat about her; but I

never saw this servant. I think you must be mistaken; besides,

how could she afford to pay her wages?"

"She has a servant, I say," repeated the cobbler; "a one-eyed

servant—but she pays her no wages, to my certain knowledge.

Well, good-morning, mistress, I must go."

"Do stop one minute," cried Bella, urgently—"where did she

get this servant?"

"Oh, I don't know," said the cobbler, "servants are plentiful

enough; and Polly uses hers well, I can tell you."

"And what does she do for her?"

"Do for her? Why, all sorts of things—I think she's the

cause of her prosperity. To my knowledge she never refuses to

do anything—keeps Tom's and Polly's clothes in beautiful order, and

the baby's."

"Dear me!" said Bella, in an envious tone, and holding up

both her hands; "well, she is a lucky woman, and I always said so.

She takes good care I shall never see her servant. What sort

of a servant is she, and how came she to have only one eye?"

"It runs in her family," replied the cobbler, stitching

busily; "they are all so—one eye apiece; yet they make a very good

use of it, and Polly's servant has four cousins who are blind—stone

blind; no eyes at all; and they sometimes come and help her.

I've seen them in the cottage myself, and that's how Polly gets a

good deal of her money. They work for her, and she takes what

they make to market, and buys all those handsome things."

"Only think," said Bella, almost ready to cry with vexation,

"and I've not got a soul to do anything for me; how hard it

is!" and she took up her apron to wipe away her tears.

The cobbler looked attentively at her. "Well, you are

to be pitied, certainly," he said, "and if I were not in such a

hurry—"

"Oh, do go on, pray—were you going to say you could help me?

I've heard that your people are fond of curds and whey, and fresh

gooseberry syllabub. Now, if you would help me, trust me that

there should be the most beautiful curds and whey set every night

for you on the hearth; and nobody should ever look when you went and

came."

"Why, you see," said the cobbler, hesitating, "my people are

extremely particular about—in short, about—cleanliness, mistress;

and your house is not what one would call very clean. No

offence, I hope?"

Bella blushed deeply—"Well, but it should be always clean if

you would—every day of my life I would wash the floor, and sand it,

and the hearth should be whitewashed as white as snow, and the

windows cleaned."

"Well," said the cobbler, seeming to consider, "well, then, I

should not wonder if I could meet with a one-eyed servant for you,

like your neighbour's; but it may be several days before I can and

mind, mistress, I'm to have a dish of curds."

"Yes, and some whipped cream, too," replied Bella, full of

joy.

The cobbler then took up his tools, wrapped them in his

leather apron, walked behind the wallflower, and disappeared.

Bella was so delighted, she could not sleep that night for

joy. Her husband scarcely knew the house, she had made it so

bright and clean; and by night she had washed the curtain, cleaned

the window, rubbed the fire-irons, sanded the floor, and set a great

jug of hawthorn in blossom on the hearth.

The next morning Bella kept a sharp look-out both for the

tiny cobbler and on her neighbour's house, to see whether she could

possibly catch a glimpse of the one-eyed servant. But,

no—nothing could she see but her neighbour sitting on her

rocking-chair, with her baby on her knee, working.

At last, when she was quite tired, she heard the voice of the

cobbler outside. She ran to the door, and cried out―

"Oh do, pray, come in, sir, only look at my house!"

"Really," said the cobbler, looking round, "I declare I

should hardly have known it—the sun can shine brightly now through

the clear glass and what a sweet smell of hawthorn!"

"Well, and my one-eyed servant?" asked Bella—"you remember, I

hope, that I can't pay her any wages—have you met with one that will

come?"

"All's right," replied the little man, nodding. "I've

got her with me."

"Got her with you?" repeated Bella, looking round, "I see

nobody."

"Look, here she is!" said the cobbler, holding up something

in his hand.

Would you believe it? the one-eyed servant was nothing but a

Needle.

――――♦――――

The Lonely Rock.

THREE summers ago

I had a severe illness, and on recovering from it, my father took me

for change of air, not to one of our pretty townish watering-places,

but up to the very North of Scotland, to a place which he had

himself delighted in when a boy, a lonely farmhouse, standing on the

shore of a rocky bay in one of the Orkneys.

My father is a Highlander, and though he has lived in England

from his early youth, he retains, not only a strong love for his own

country, but a belief in its healthfulness; he is fond of indulging

the fancy that scenery which the fathers have delighted in, will not

strike on the senses of the children as something new and strange,

but they will enter the hereditary region with a half-formed notion

that they must have seen it before, and it will possess a soothing

power over them which is better than familiarity itself.

I had often heard my father express this idea, but had

neither understood nor believed in it. The listlessness of

illness made me indifferent as to what became of me, and during our

steam voyage I cared neither to move nor to look about me. But

the result proved that my father was right. It was dark when

we reached our destination, but I no sooner opened my eyes the next

morning than a delightful home-feeling came over me; I could not

look about me enough, and yet nothing was sufficiently unexpected to

cause me the least surprise.

It was August, the finest part of the northern summer; and as

I lay on pillows, looking out across the bay, I enjoyed that perfect

quietude and peace so grateful to those who have lately suffered

from the turmoil and restlessness of fever. I had imagined

myself always surrounded by shifting, hurrying crowds, always

oppressed by the gaze of unbidden guests; how complete and welcome

was this change, this seclusion! No one but my father and the

young servant whom we had brought with us could speak a word that I

understood, and I could fall asleep and wake again, quite secure

from the slightest interruption.

By the first blush of dawn I used to wake up, and lie

watching that quiet bay; there would be the shady crags, dark and

rocky, lifting and stretching themselves as if to protect and

embrace the water, which, perhaps, would be lying utterly still, or

just lapping against them, and softly swaying to and fro the long

banners of sea-weed which floated out from them.

Or, perhaps, a thin mist would be hanging across the entrance

of the bay, like a curtain drawn from cliff to cliff; presently this

snowy curtain would turn of an amber colour, and glow towards the

centre; once I wondered if that sudden glow could be a ship on fire,

and watched it in fear, but I soon saw the gigantic sun thrust

himself up, so near, as it seemed, that the farthest cliffs as they

melted into the mist appeared farther off than he—so near, that it

was surprising to count the number of little fishing-boats that

crossed between me and his great disc; still more surprising to

watch how fast he receded, growing so refulgent that he dazzled my

eyes, while the mist began to waver up and down, curl itself, and

roll away to sea, till on a sudden up sprang a little breeze, and

the water, which had been white, streaked here and there with a line

of yellow, was blue almost before I could mark the change, and

covered with brisk little ripples, and the mist had melted back into

some half-dozen caverns, within which it soon receded and was lost.

I used to lie and learn that beautiful bay by heart. In

the afternoon the water was often of a pale sea-green, and the

precipitous cliffs were speckled with multitudes of sea-birds, and

bright in the sunshine I loved to watch at a distance the small

mountain goats climbing from point to point; wherever there was a

strip of grass I was sure to see their white breasts; but above all

things, I love to watch the long wavy reflection of a tall black

rock which was perfectly isolated, and stood out to sea in the very

centre of the bay. I was the more occupied in fancy with this

rock, because, unlike the other features of the landscape, it never

changed.

The sea was white, it was yellow, it was green, it was blue;

the sea was gone a long way off, and the sands were bare; the sea

was come back again, was rushing up between every little rock, and

powdering the tops of them with spray; the sea was clear as a

mirror, and white gulls were swimming on it by thousands; the sea

was restless, and the rocking boats were tossing up and down on it.

And the cliffs? In moonlight they were castles and they were

ships; in sunshine they were black, brown, blue, green, and ruddy,

according to the clouds and the height of the sun. Their

shadows, too, now a narrow strip at their bases, now an

overshadowing mass, gave endless variety to the scene.

But this one black rock out at sea never seemed to change. In

appearance at that distance it was a massive column, square and

bending inward at the centre, so as to make it lean towards the

northern shore. Considering this changeless character, it was

rather strange that in my dreams, still vivid from recent illness,

this column always assumed the likeness of a man. A stern man

it seemed to be, with head sunk on his breast, and arms gathered

under the folds of a dark heavy mantle; yet when I awoke and looked

out over the bay, the blue moonbeams would not drop on my rock, or

its reflection, in such a way as to make it any other than the bare,

bleak, bending thing that I always saw it.

In a week I was able to come out of doors, and wander by the

help of my father's arm along the strip of yellow sand by the sea.

How delightful was the feeling of leaf, pebble, sand, or sea-weed to

my hand, which so long had been used to nothing but the soft linen

of my pillow! How beautiful and fresh everything looked out of

doors; how delicious was the sound of the little inch-deep waves as

they ran and spread briskly out over the flat green floors of the

caverns; how still more delicious the crisp rustling of the

displaced pebbles, when these capricious waves receded!

And the caverns! How I stood looking into them, sunny

and warm as they were at the entrance, and gloomily grand within.

What a pleasure it was to think that the world should be so full of

beautiful places, even where few had cared to look at them; how

wonderful to think that the self-same echo, which answered my voice

when I sang to it, was always dying there, ready to be spoken with,

though rarely invoked but by the winds and the waves; that ever

since the Deluge, perhaps, it had possessed this power to mock human

utterance, but unless it had caught up and repeated the cries of

some drowning fisher-boy, or shipwrecked mariner, and sent them back

again more wild than before, its mocking syllables and marvellous

cadences had never been tested but by me

And the first sail in a boat was a pleasure which can never

be forgotten.

It was a still afternoon when we stepped into that boat, so

still that we had oars as well as the flapping sail; I had wished to

row out to sea as far as the rock, and now I was to have my wish.

On and on we went, looking by turns into the various clefts and

caverns; at last we stood out into the middle of the bay, and very

soon we had left the cliffs altogether behind. We were out in

the open sea, but still the rock was far before us; it became

taller, larger, and more important, but yet it presented the same

outline, and precisely the same aspect, when, after another

half-hour's rowing, we drew near it, and I could hear the water

lapping against its inhospitable sides.

The men rested on their oars, and allowed the boat to drift

down towards it. There it stood, high, lonely, inaccessible.

I looked up; there was scarcely a crevice where a sea-fowl could

have built, not a level slip large enough for human foot to stand

upon, nor projection for hand or drowning man to seize on.

Shipwreck and death it had often caused, it was the dread and

scourge of the bay, but it yielded no shelter nor food for beast or

bird, not a blade of grass waved there—nothing stood there.

We rowed several times round it, and every moment I became

more impressed with its peculiar character and situation, so

completely aloof from everything else—even another rock as hard and

black as itself, standing near it, would have been apparent

companionship. If one goat had fed there, if one sea-bird had

nestled there, if one rope of tangled sea-weed had rooted there, and

floated out on the surging water to meet the swimmer's hand—but no;

I looked, and there was not one. The water washed up against

it, and it flung back the water; the wind blew against it, and it

would not echo the wind; its very shadow was useless, for it dropped

upon nothing that wanted shade. By day the fisherman looked at

it only to steer clear of it, and by night, if he struck against it,

he went down. Hard, dreary, bleak! I looked at it as we

floated slowly towards home; there it stood rearing up its desolate

head, a forcible image, and a true one, of a thoroughly selfish, a

thoroughly unfeeling and isolated human heart.

Now let us go back a long time, and talk about things which

happened before we were born. I do not mean centuries ago,

when the sea-kings, in their voyages plundering that coast, drove by

night upon the rock and went down. That is not the long time

ago of which I want to speak; nor of that other long time ago, when

two whaling vessels, large and deeply laden, bounded against it in a

storm, and beat up against it till the raging waves tore them to

pieces, and splitting and grinding every beam and spar, scarcely

threw one piece of wreck on the shore which was as long as the

bodies of the mariners. I am not going to tell of the many

fishing-boats which went out and were seen no more—of the many brave

men that hard by that fatal place went under the surging water—of

the many toiling rowers that made, as they thought, straight for

home, and struck, and had only time for one cry—"The Rock! the

Rock!" The long time ago of which I mean to tell was a wild

night in March, during which, in a fisherman's hut ashore, sat a

young girl at her spinning-wheel, and looked out on the dark driving

clouds, and listened, trembling, to the wind and the sea.

The morning light dawned at last. One boat that should

have been riding on the troubled waves was missing—her father's

boat! and half a mile from his cottage, her father's body was washed

up on the shore.

This happened fifty years ago, and fifty years is a long time

in the life of a human being; fifty years is a long time to go on in

such a course, as the woman did of whom I am speaking. She

watched her father's body, according to the custom of her people,

till he was laid in the grave. Then she lay down on her bed

and slept, and by night got up and set a candle in her casement, as

a beacon to the fishermen and a guide. She sat by the candle

all night, and trimmed it, and span; then when day dawned she went

to bed and slept in the sunshine.

So many hanks as she had spun before for her daily bread, she

span still, and one over, to buy her nightly candle; and from that

time to this, for fifty years, through youth, maturity, and old age,

she has turned night into day, and in the snowstorms of winter,

through driving mists, deceptive moonlight, and solemn darkness,

that northern harbour has never once been without the light of her

candle.

How many lives she saved by this candle, or how many a meal

she won by it for the starving families of the boatmen, it is

impossible to say; how many a dark night the fisherman, depending on

it, went fearlessly forth, cannot now be told. There it stood,

regular as a lighthouse, steady as constant care could make it.

Always brighter when daylight waned, they had only to keep it

constantly in view and they were safe; there was but one thing that

could intercept it, and that was the rock. However far they

might have stretched out to sea, they had only to bear down straight

for that lighted window, and they were sure of a safe entrance into

the harbour.

Fifty years of life and labour—fifty years of sleeping in the

sunshine—fifty years of watching and self-denial, and all to feed

the flame and trim the wick of that one candle! But if we look

upon the recorded lives of great men, and just men, and wise men,

few of them can show fifty years of worthier, certainly not of more

successful labour. Little, indeed, of the "midnight oil"

consumed during the last half century so worthily deserved the

trimming. Happy woman—and but for the dreaded rock her great

charity might never have been called into exercise!

But what do the boatmen and the boatmen's wives think of

this? Do they pay the woman?

No, they are very poor; but poor or rich, they know better

than that.

Do they thank her?

No. Perhaps they feel that thanks of theirs would be

inadequate to express their obligations, or, perhaps, long years

have made the lighted casement so familiar, that they look on it as

a matter of course.

Sometimes the fishermen lay fish on her threshold, and set a

child to watch it for her till she wakes; sometimes their wives

steal into her cottage, now she is getting old, and spin a hank or

two of thread for her while she slumbers; and they teach their

children to pass her hut quietly, and not to sing and shout before

her door, lest they should disturb her. That is all.

Their thanks are not looked for—scarcely supposed to be due.

Their grateful deeds are more than she expects, and as much as she

desires.

How often in the far distance of my English home I have awoke

in a wild winter night, and, while the wind and storm were rising,

have thought of that northern bay, with the waves dashing against

the rock, and have pictured to myself the casement, and the candle

nursed by that bending, aged figure! How delightful to know

that through her untiring charity the rock had long lost more than

half its terrors, and to consider that, curse though it may be to

all besides, it has most surely proved a blessing to her!

You, too, may perhaps think with advantage on the character

of this woman, and contrast it with the mission of the rock.

There are many degrees between them. Few, like the rock, stand

up wholly to work ruin and destruction; few, like the woman, "let

their light shine" so brightly for good. But to one of the

many degrees between them we must all most certainly belong—we all

lean towards the woman or the rock. On such characters you do

well to speculate with me, for you have not been cheated into

sympathy with ideal shipwreck or imaginary kindness. There is

many a rock elsewhere as perilous as the one I have told you

of—perhaps there are many such women; but for this one, whose story

is before you, pray that her candle may burn a little longer, since

this record of her charity is true.

――――♦――――

The Minnows with Silver Tails.

THERE was a

cuckoo-clock hanging in Tom Turner's cottage. When it struck

One, Tom's wife laid the baby in the cradle, and took a saucepan off

the fire, from which came a very savoury smell.

Her two little children, who had been playing in the open

doorway, ran to the table, and began softly to drum upon it with

their pewter spoons, looking eagerly at their mother as she turned a

nice little piece of pork into a dish, and set greens and potatoes

round it. They fetched the salt; then they set a chair for

their father; brought their own stools; and pulled their mother's

rocking-chair close to the table.

"Run to the door, Billy," said the mother, "and see if

father's coming." Billy ran to the door; and, after the

fashion of little children, looked first the right way, and then the

wrong way, but no father was to be seen.

Presently the mother followed him, and shaded her eyes with

her hand, for the sun was hot. "If father doesn't come soon,"

she observed, "the apple-dumpling will be too much done, by a deal."

"There he is!" cried the little boy, "he is coming round by

the wood; and now he's going over the bridge. O father! make

haste, and have some apple-dumpling."

"Tom," said his wife, as he came near, "art tired to-day?"

"Uncommon tired," said Tom, and he threw himself on the

bench, in the shadow of the thatch.

"Has anything gone wrong?" asked his wife "what's the

matter?"

"Matter?" repeated Tom, "is anything the matter? The

matter is this, mother, that I'm a miserable hard-worked slave; and

he clapped his hands upon his knees, and muttered in a deep voice,

which frightened the children—"a miserable slave!"

"Bless us!" said his wife, and could not make out what he

meant.

"A miserable, ill-used slave," continued Tom, "and always

have been."

"Always have been?" said his wife, "why, father, I thought

thou used to say, at the election time, that thou wast a free-born

Briton?"

"Women have no business with politics," said Tom, getting up

rather sulkily. And whether it was the force of habit, or the

smell of the dinner, that made him do it, has not been ascertained,

but it is certain that he walked into the house, ate plenty of pork

and greens, and then took a tolerable share in demolishing the

apple-dumpling.

When the little children were gone out to play, his wife said

to him, "Tom, I hope thou and master haven't had words to-day?"

"Master," said Tom, "yes, a pretty master he has been;

and a pretty slave I've been. Don't talk to me of masters."

"O Tom, Tom," cried his wife, "but he's been a good master to

you; fourteen shillings a week, regular wages—that's not a thing to

make a sneer at; and think how warm the children are lapped up o'

winter nights, and you with as good shoes to your feet as ever keep

him out of the mud."

"What of that?" said Tom, "isn't my labour worth the money?

I'm not beholden to my employer. He gets as good from me as he

gives."

"Very like, Tom. There's not a man for miles round that

can match you at a graft; and as to early peas—but if master can't

do without you, I'm sure you can't do without him. Oh dear, to

think that you and he should have had words!"

"We've had no words," said Tom, impatiently; "but I'm sick of

being at another man's beck and call. It's Tom do this,' and

'Tom do that,' and nothing but work, work, work, from Monday morning

till Saturday night; and I was thinking, as I walked over to Squire

Morton's to ask for the turnip seed for master— I was thinking,

Sally, that I am nothing but a poor working man after all. In

short, I'm a slave, and my spirit won't stand it."

So saying, Tom flung himself out at the cottage door, and his

wife thought he was going back to his work as usual. But she

was mistaken; he walked to the wood, and there, when he came to the

border of a little tinkling stream, he sat down, and began to brood

over his grievances. It was a very hot day.

"Now, I'll tell you what," said Tom to himself, "it's a great

deal pleasanter sitting here in the shade than broiling over celery

trenches; and then thinning of wall fruit, with a baking sun at

one's back, and a hot wall before one's eyes. But I'm a

miserable slave. I must either work or see 'em starve; a very

hard lot it is to be a working-man. But it is not only the

work that I complain of, but being obliged to work just as he

pleases. It's enough to spoil any man's temper to be told to

dig up those asparagus beds just when they were getting to be the

very pride of the parish. And what for? Why, to make

room for Madam's new gravel walk, that she mayn't wet her feet going

over the grass. Now, I ask you," continued Tom, still talking

to himself, "whether that isn't enough to spoil any man's temper?"

"Ahem!" said a voice close to him.

Tom started, and to his great surprise, saw a small man,

about the size of his own baby, sitting composedly at his elbow.

He was dressed in green—green hat, green coat, and green shoes.

He had very bright black eyes, and they twinkled very much as he

looked at Tom and smiled.

"Servant, sir!" said Tom, edging himself a little further

off.

"Miserable slave," said the small man, "art thou so far lost

to the noble sense of freedom that thy very salutation acknowledges

a mere stranger as thy master?"

"Who are you," said Tom, "and how dare you call me a slave?"

"Tom," said the small man, with a knowing look, "don't speak

roughly. Keep your rough words for your wife, my man, she is

bound to bear them—what else is she for, in fact?"

"I'll thank you to let my affairs alone," interrupted Tom,

shortly.

"Tom, I'm your friend; I think I can help you out of your

difficulty. I admire your spirit. Would I demean

myself to work for a master, and attend to all his whims?" As

he said this the small man stooped and looked very earnestly into

the stream. Drip, drip, drip, went the water over a little

fall in the stones, and wetted the watercresses till they shone in

the light, while the leaves fluttered overhead and chequered the

moss with glittering spots of sunshine. Tom watched the small

man with earnest attention as he turned over the leaves of the

tresses. At last he saw him snatch something, which looked

like a little fish, out of the water, and put it in his pocket.

"It's my belief, Tom," he said, resuming the conversation,

"that you have been puzzling your head with what people call

Political Economy."

"Never heard of such a thing," said Tom. "But I've been

thinking that I don't see why I'm to work any more than those that

employ me."

"Why, you see, Tom, you must have money. Now it seems

to me that there are but four ways of getting money: there's

Stealing—"

"Which won't suit me," interrupted Tom.

"Very good. Then there's Borrowing—"

"Which I don't want to do."

"And there's Begging—"

"No, thank you," said Tom, stoutly.

"And there's giving money's worth for the money; that is to

say, Work, Labour."

"Your words are as fine as a sermon," said Tom.

"But look here, Tom," proceeded the man in green, drawing his

hand out of his pocket, and showing a little dripping fish in his

palm, "what do you call this?"

"I call it a very small minnow," said Tom.

"And do you see anything special about its tail?"

"It looks uncommon bright," answered Tom, stooping to look at

it.

"It does," said the man in green, "and now I'll tell you a

secret, for I'm resolved to be your friend. Every minnow in

this stream—they are very scarce, mind you—but every one of them has

a silver tail."

"You don't say so," exclaimed Tom, opening his eyes very

wide; "fishing for minnows, and being one's own master, would be a

great deal pleasanter than the sort of life I have been leading this

many a day."

"Well, keep the secret as to where you get them; and much

good may it do you," said the man in green. "Farewell, I wish

you joy of your freedom." So saying he walked away, leaving

Tom on the brink of the stream, full of joy and pride.

He went to his master, and told him that he had an

opportunity for bettering himself, and should not work for

him any longer. The next day he rose with the dawn, and went

to work to search for minnows. But of all the minnows in the

world never were any so nimble as those with silver tails.

They were very shy too, and had as many turns and doubles as a hare;

what a life they led him! They made him troll up the stream

for miles; then, just as he thought his chase was at an end, and he

was sure of them, they would leap quite out of the water, and dart

down the stream again like little silver arrows. Miles and

miles he went, tired, and wet, and hungry. He came home late

in the evening completely wearied and footsore, with only three

minnows in his pocket, each with a silver tail.

"But at any rate," he said to himself, as he lay down in his

bed, "though they lead me a pretty life, and I have to work harder

than ever, yet I certainly am free; no man can order me about now."

This went on for a whole week; he worked very hard; but on

Saturday afternoon he had only caught fourteen minnows.

"If it wasn't for the pride of the thing," he said to

himself, "I'd have no more to do with fishing for minnows.

This is the hardest work I ever did. I am quite a slave to

them. I rush up and down, I dodge in and out, I splash myself,

and fret myself, and broil myself in the sun, and all for the sake

of a dumb thing, that gets the better of me with a wag of its fins.

But it's no use standing here talking; I must set off to the town

and sell them, or Sally will wonder why I don't bring her the week's

money." So he walked to the town, and offered his fish for

sale as great curiosities.

"Very pretty," said the first people he showed them to; but

"they never bought anything that was not useful."

"Were they good to eat?" asked the woman at the next house.

"No! Then they would not have them."

"Much too dear," said a third.

"And not so very curious," said a fourth; "but they hoped he

had come by them honestly." At the fifth house they said, "O!

pooh!" when he exhibited them. "No, no, they were not quite so

silly as to believe there were fish in the world with silver tails;

if there had been, they should often have heard of them before."

At the sixth house they were such a very long time turning

over his fish, pinching their tails, bargaining and discussing them,

that he ventured to remonstrate, and request that they would make

more haste. Thereupon they said that if he did not choose to

wait their pleasure, they would not purchase at all. So they

shut the door upon him, and as this soured his temper, he spoke

rather roughly at the next two houses, and was dismissed at once as

a very rude, uncivil person.

But, after all, his fish were really great curiosities; and

when he had exhibited them all over the town, set them out in all

lights, praised their perfections, and taken immense pains to

conceal his impatience and ill temper, he at length contrived to

sell them all, and got exactly fourteen shillings for them, and no

more.

"Now, I'll tell you what, Tom Turner," he said to himself,

"in my opinion you've been making a great fool of yourself, and I

only hope Sally will not find it out. You was tired of being a

workingman, and that man in green has cheated you into doing the

hardest week's work you ever did in your life by making you believe

it was more free-like and easier. Well, you said you didn't

mind it, because you had no master; but I've found out this

afternoon, Tom, and I don't mind your knowing it, that every one of

those customers of yours was your master just the same. Why!

you were at the beck of every man, woman, and child that came near

you—obliged to be in a good temper, too, which was very

aggravating."

"True, Tom," said the man in green, starting up in his path,

"I knew you were a man of sense; look you, you're all

working-men, and you must all please your customers. Your

master was your customer; what he bought of you was your work.

Well, you must let the work be such as will please the customer."

"All working-men; how do you make that out?" said Tom,

chinking the fourteen shillings in his hand. "Is my master a

working-man? and has he got a master of his own? Nonsense!"

"No nonsense at all;—he works with his head, keeps his books,

and manages his great works. He has many masters, else why was

he nearly ruined last year?"

"He was nearly ruined because he made some new-fangled kind

of patterns at his works, and people would not buy them," said Tom.

"Well, in a way of speaking, then, he works to please his masters,

poor fellow! He is, as one may say, a fellow-servant, and

plagued with very awkward masters! So I should not mind his

being my master, and I think I'll go and tell him so."

"I would, Tom," said the man in green. "Tell him you

have not been able to better yourself, and you have no

objection now to dig up the asparagus bed."

So Tom trudged home to his wife, gave her the money he had

earned, got his old master to take him back, and kept secret his

adventures with the man in green, and the fish with the silver

tails.

――――♦――――

The Golden Opportunity.

NOT many things

have happened to me in the course of my life which can be called

events. One great event, as I then thought it, happened when I

was eight years old. On that birthday I first possessed a

piece of gold.

How well I remember the occasion! I had a holiday, and

was reading aloud to my mother. The book was the "Life of

Howard, the philanthropist." I was interested in it, though

the style was considerably above my comprehension; at last I came to

the following sentence, which I could make nothing of: "He could not

let slip such a golden opportunity for doing good."

"What is a golden opportunity?" I inquired.

"It means a very good opportunity."

"But, mamma, why do they call it golden?"

My mamma smiled, and said it was a figurative expression;

"Gold is very valuable and very uncommon; this opportunity was a

very valuable and uncommon one; we can express that in one word, by

calling it a golden opportunity."

I pondered upon the information for some time, and then made

a reply to the effect, that all the golden opportunities seemed to

happen to very rich people, or people who lived a long time ago, or

else to great men, whose lives we can read in books—very great men,

such as Wilberforce and Howard; but they never happened to real

people, whom we could see every day, nor to children.

"To children like you, Orris?" said my mother; "why, what

kind of a golden opportunity are you wishing for just now?"

My reply was childish enough.

"If I were a great man I should like to sail after the slave

ships, fight them, and take back the poor slaves to their own

country. Or I should like to do something like what Quintus

Curtius did. Not exactly like that; because you know, mamma,

if I were to jump into a gulf, that would not really make it close."

"No," said my mother, "it would not."

"And, besides," I reasoned, "if it had closed, I

should never have known of the good I had done, because I should

have been killed."

"Certainly," said my mother; I saw her smile, and thinking it

was at the folly of my last wish, hastened to bring forward a wiser

one.

"I think I should like to be a great lady, and then if there

had been a bad harvest, and all the poor people on my lord's land

were nearly starving, I should like to come down to them with a

purse full of money, and divide it among them. But you see,

mamma, I have no golden opportunities."

"My dear, we all have some opportunities for doing good, and

they are golden, or not, according to the use we make of them."

"But, mamma, we cannot get people released out of prison, as

Howard did."

"No, but sometimes, by instructing them in their duty, by

providing them with work, so that they shall earn bread enough, and

not be tempted, and driven by hunger to steal, we can prevent some

people from being ever put in prison."

My mother continued to explain that those who really desired

to do good never wanted opportunities, and that the difference

between Howard and other people was more in perseverance and

earnestness than in circumstances. But I do not profess to

remember much of what she said; I only know that, very shortly, she

took me into my grandfather's study, and sitting down, began busily

to mend a heap of pens which lay beside him on the table.

He was correcting proof-sheets, and, knowing that I must not

talk, I stood awhile very quietly watching him.

Presently I saw him mark out a letter in the page, make a

long stroke in the margin, and write a letter d beside it.

Curiosity was too much for my prudence; I could not help

saying―

"Grandpapa, what did you write that letter d for?"

"There was a letter too much in the word, child," he replied;

I spell 'potatoes' with only one p, and I want the

printer to put out the second."

"Then d stands for don't, I suppose," was my

next observation; "it means don't put it in."

"Yes, child, yes; something like that."

If it had not been my birthday I should not have had courage

to interrupt him again. "But, grandpapa, 'do' begins

with d, so how is the printer to know whether you mean 'do'

or 'don't'?"

My grandfather said "Pshaw!" turned short round upon my

mother, and asked her if she had heard what I said?

My mother admitted that it was a childish observation.

"Childish!" repeated my grandfather, "childish! she'll never

be anything but a child—never; she has no reasoning faculties at

all." When my grandfather was displeased with me, he never

scolded me for the fault of the moment, but inveighed against me

in the peice, as a draper would say.

"Did you ever talk nonsense at her age—ever play with

a penny doll, and sing to a kitten? I should think not."

"I was of a different disposition," said my mother, gently.

"Ay," said the old man, "that you were. Why, I wouldn't

trust this child, as I trusted you, for the world; you were quite a

little woman, could pay bills, or take charge of keys; but this

child has no discretion—no head-piece. She says things that

are wide of the mark. She's—well, my dear, I didn't mean to

vex you—she's a nice child enough, but, bless me, she never

thinks, and never reasons about anything."

He was mistaken. I was thinking and reasoning at that

moment. I was thinking how delightful it would be if I might

have the cellar keys, and all the other keys hanging to my side, so

that everyone might see that I was trusted with them; and I was

reasoning, that perhaps my mother had behaved like a little woman,

because she was treated like one.

"My dear, I did not mean that she was worse than many other

children," repeated my grandfather; "come here, child, and I'll kiss

you."

My mother pleaded, by way of apology for me, "She has a very

good memory."

"Memory! ay, there's another disadvantage. She

remembers everything; she's a mere parrot. Why, when you, at

her age, wanted a punishment, if I set you twenty lines of poetry,

they'd keep you quiet for an hour. Set this child eighty—knows

'em directly, and there's time wasted in hearing her say 'em into

the bargain."

"I hope she will become more thoughtful as she grows older,"

said my mother gently.

"I hope she will; there's room for improvement. Come

and sit on my knee, child. So this is your birthday.

Well, I suppose I must give you some present or other. Leave

the child with me, my dear. I'll take care of her. But I

won't detain you, for the proofs are all ready. Open the door

for your mother, Orris. Ah! you'll never be anything like

her—never."

I did as he desired, and then my grandfather, looking at me

with comical gravity, took out a leathern purse, and dived with his

fingers among the contents. "When I was a little boy, as old

as you are, nobody gave me any money."

Encouraged by his returning good-humour, I drew closer and

peeped into the purse. There were as many as six or eight

sovereigns in it. I thought what a rich man my grandfather

was, and when he took out a small coin and laid it on my palm, I

could scarcely believe it was for me.

"Do you know what that is, child?"

"A half-sovereign, grandpapa."

"Well, do you think you could spend it?"

"Oh yes, grandpapa."

"'Oh yes!' and she opens her eyes! Ah, child, child!

that money was worth ten shillings when it was in my purse, and I

wouldn't give sixpence for anything it will buy, now it has once

touched your little fingers."

"Did you give it me to spend exactly as I like, grandpapa?"

"To be sure, child—there, take it—it's worth nothing to you,

my dear."

"Nothing to me! The half-sovereign worth nothing to me!

why, grandpapa?"

"Nothing worth mentioning; you have no real wants; you have

clothes, food, and shelter, without this half-sovereign."

"Oh yes; but, grandpapa, I think it must be worth ten times

as much to me as to you; I have only this one, and you have

quantities; I shouldn't wonder if you have thirty or forty

half-sovereigns, and a great many shillings and half-crowns besides,

to spend every year."

"I shouldn't wonder!"

"And I have only one. I can't think, grand-papa, what

you do with all your money; if I had it I would buy so many

delightful things with it."

"No doubt! kaleidoscopes and magic lanterns, and all sorts of

trash. But, unfortunately, you have not got it; you have only

one half-sovereign to throw away."

"But perhaps I shall not throw it away; perhaps I shall try

and do some good with it."

"Do some good with it! Bless you, my dear, if you do

but try to do some good with it, I shall not call it thrown away."

I then related what I had been reading, and had nearly

concluded when the housemaid came in. She laid a crumbled

piece of paper by his desk, and with it a shilling and a penny,

saying, "There's the change, sir, out of your shoemaker's bill."

My grandfather took it up, looked at it, and remarked that

the shilling was a new one. Then, with a generosity which I

really am at a loss to account for, he actually, and on the spot,

gave me both the shilling and the penny.

There they lay in the palm of my hand, gold, silver, and

copper. He then gave me another kiss and abruptly dismissed

me, saying that he had more writing to do; and I walked along the

little passage with an exultation of heart that a queen might have

envied, to show this unheard-of wealth to my mother.

I remember laying the three coins upon a little table, and

dancing round it, singing, "There's a golden opportunity! and

there's a silver opportunity! and there's a copper opportunity!" and

having continued this exercise till I was quite tired, I spent the

rest of the morning in making three little silk bags, one for each

of them, previously rubbing the penny with sand-paper, to make it

bright and clean.

Visions and dreams floated through my brain as to the good I

was to do with this property. They were vain-glorious, but not

selfish; but they were none of them fulfilled, and need not be

recorded. The next day, just as my lessons were finished, papa

came in with his hat and stick in his hand; he was going to walk to

the town, and offered to take me with him.

It was always a treat to walk out with my father, especially

when he went to the town. I liked to look in at the

shop-windows and admire their various contents.

To the town therefore we went. My father was going to

the Mechanics' Institute, and could not take me in with him, but

there was a certain basket maker, with whose wife I was often left

on these occasions. To this good woman he brought me, and went

away, promising not to be long.

And now, dear reader, whoever you may be, I beseech you judge

not too harshly of me; remember I was but a child, and it is certain

that if you are not a child yourself, there was a time when you were

one. Next door to the basket-maker's there was a toy-shop, and

in its window I espied several new and very handsome toys.

"Mr. Miller's window looks uncommon gay," said the old

basket-maker, observing the direction of my eyes.

"Uncommon," repeated his wife those new gimcracks from London

is handsome surely."

"Wife," said the old man, "there's no harm in missy's just

taking a look at 'em—eh?"

"Not a bit in the world, bless her," said the old woman; "I

know she'll go no further, and come back here when she's looked 'em

over."

"Oh yes, indeed I will. Mrs. Stebbs, may I go?"

The old woman nodded assent, and I was soon before the window.

Splendid visions! Oh, the enviable position of Mr.

Miller! How wonderful that he was not always playing with his

toys, showing himself his magic lanterns, setting out his puzzles,

and winding up his musical boxes. Still more wonderful, that

he could bear to part with them for mere money!

I was lost in admiration when Mr. Miller's voice made me

start—"Wouldn't you like to step inside, miss?"

He said this so affably that I felt myself quite welcome, and

was beguiled into entering. In an instant he was behind the

counter. "What is the little article I can have the pleasure,

miss—"

"Oh!" I replied, blushing deeply, "I do not want to buy

anything this morning, Mr. Miller."

"Indeed, miss, that's rather a pity. I'm sorry,

miss, I confess, on your account. I should like to have

served you, while I have goods about me that I'm proud of. In

a week or two," and he looked pompously about him, "I should say in

less time than that, they'll all be cleared out."

"What! will they all be gone—all sold?" I exclaimed in

dismay.

"Just so, miss, such is the appreciation of the public;" and

he carelessly took up a little cedar stick and played "The Blue

Bells of Scotland" on the glass keys of a plaything piano.

"This," he observed, coolly throwing down the stick and

taking up an accordion, "this delightful little instrument is

half-a-guinea—equal to the finest notes of the hautboy." He

drew it out, and in his skilful hands it "discoursed" music, which I

thought the most excellent I had ever heard.

But what is the use of minutely describing my temptation?

In ten minutes the accordion was folded up in silver paper, and I

had parted with my cherished half-sovereign.

As we walked home, I enlarged on the delight I should have in

playing on my accordion. "It is so easy, papa; you have only

to draw it in and out; I can even play it at dinner-time, if you

like, between the meat and the puddings. You know the queen

has a band, papa, to play while she dines, and so can you."

My father abruptly declined this liberal offer so did my

grandfather, when I repeated it to him, but I was relieved to find

that he was not in the least surprised at the way in which I had

spent his present. This, however, did not prevent my feeling

sundry twinges of regret when I remembered all my good intentions.

But, alas! my accordion soon cost me tears of bitter disappointment.

Whether from its faults, or my own, I could not tell, but draw it

out, and twist it about as I might, it would not play "The Blue

Bells of Scotland," or any other of my favourite tunes. It was

just like the piano, every tune must be learned; there was no music

inside which only wanted winding out of it, as you wind the tunes

out of barrel organs.

My mother coming in some time during that melancholy

afternoon, found me sitting at the foot of my little bed holding my

accordion, and shedding over it some of the most bitter tears that

shame and repentance had yet wrung from me.

She looked astonished, and asked, "What is the matter, my

child?"

"Oh, mamma," I replied, as well as my sobs would let me, "I

have bought this thing which won't play, and I have given Mr. Miller

my golden opportunity."

"What, have you spent your half-sovereign? I thought

you were going to put poor little Patty Morgan to school with it,

and give her a new frock and tippet."

My tears fell afresh at this, and I thought how pretty little

Patty would have looked in the new frock, and that I should have put

it on for her myself. My mother sat down by me, took away the

toy, and dried my eyes. "Now, you see, my child," she

observed, "one great difference between those who are earnestly

desirous to do good, and those who only wish it lightly. You

had what you were wishing for—a good opportunity; for a child like

you, an unusual opportunity for doing good. You had the means

of putting a poor little orphan to school for one whole year—think

of that, Orris! In one whole year she might have learned a

great deal about the God who made her, and who gave His Son to die

for her, and His Spirit to make her holy. One whole year would

have gone a great way towards teaching her to read the Bible; in one

year she might have learned a great many hymns, and a great many

useful things, which would have been of service to her when she was

old enough to get her own living. And for what have you thrown

all this good from you and from her?"

"I am very, very sorry. I did not mean to buy the

accordion; I forgot, when I heard Mr. Miller playing upon it, that I

had better not listen; and I never remembered what I had done till

it was mine, and folded up in paper."

"You forgot till it was too late?"

"Yes, mamma; but, oh, I am so sorry. I am sure I shall

never do so any more."

"Do not say so, my child; I fear it will happen again, many,

many times."

"Many times? Oh, mamma! I will never go into Mr.

Miller's shop again."

"My dear child, do you think there is nothing in the world

that can tempt you but Mr. Miller's shop?"

"Even if I go there," I sobbed, in the bitterness of my

sorrow, "it will not matter now, for I have now no half-sovereign

left to spend; but if I had another, and he were to show me the most

beautiful toys in the world, I would not buy them after this, not if

they would play of themselves."

"My dear, that may be true; you, perhaps, would not be

tempted again when you were on your guard; but you know, Orris, you

do not wish for another toy of that kind. Are there no

temptations against which you are not on your guard?"

I thought my mother spoke in a tone of sorrow. I knew

she lamented my volatile disposition; and crying afresh, I said to

her, "Oh, mamma, do you think that all my life I shall never do any

good at all?"

"If you try in your own strength I scarcely think you will.

Certainly you will do no good which will be acceptable to God."

"Did I try in my own strength to-day?"

"What do you think, Orris? I leave it to you to

decide."

"I am afraid I did."

"I am afraid so too: but you must not cry and sob in this

way. Let this morning's experience show you how open you are

to temptation. To let it make you think you shall never yield

to such temptation again is the worst thing you can do you need help

from above; seek it, my dear child, otherwise all your good

resolutions will come to nothing."

"And if I do seek it, mamma?"

"Then, weak as you are, you will certainly be able to

accomplish something. It is impossible for me to take away

your volatile disposition, and make you thoughtful and steady, but

'width God all things are possible.'"

"It is a great pity that at the very moment when I want to

think about right things, and good things, all sorts of nonsense

comes into my head. Grandpa says I am just like a whirlgig;

and, besides, that I can never help laughing when I ought not, and I

am always having lessons set me for running about and making such a

noise when baby is asleep."

"My dear child, you must not be discontented, these are

certainly disadvantages; they will give you a great deal of trouble,

and myself too; but you have one advantage that all children are not

blessed with."

"What is that, mamma?"

"There are times when you sincerely wish to do good."

"Yes, I think I really do, mamma; I had better fold up this

thing, and put it away, for it only vexes me to see it. I am

sorry I have lost my golden opportunity."

And so, not without tears, the toy was put away. The

silver and the copper remained, but there was an end of my golden

opportunity.

My birthday had been gone by a week, and still the shilling

and the penny lay folded in their silken shrines.

I had quite recovered my spirits, and was beginning to think

how I should spend them, particularly the shilling, for I scarcely

thought any good could be done with such a small sum as a penny.

Now there was a poor Irish boy in our neighbourhood, who had come

with the reapers, and been left behind with a hurt in his leg.

My mother had often been to see him. While he was

confined to his bed, she went regularly to read with him, and

sometimes she sent me with our nursemaid to take him a dinner.

He was now much better, and could get about a little.

To my mother's surprise she found that he could read perfectly well.