|

[Previous Page]

-XX-

THE ORIGIN OF THE "WHOLESALE."

ONE of the distinctions of Rochdale is that it gave

practical form and force to the idea of a Federation of Purchasers, which

ultimately took the style and title of "The North of England Co-operative

Wholesale Society," otherwise known as the Great Manchester Wholesale

Association.

Of course no one foresaw the great ascendancy which one day would be

attained by this Society. It is very seldom that anyone does see the

ascendancy of anything while it is upon the ground. When it is soaring

over the mountain tops, the prophets of its failures declare that they

predicted its rise, and now believe they made it float.

Of course somebody began everything, and we shall see in due course to

whom the originating the wholesale ought to be mainly ascribed. Mr. A.

Greenwood's own history of attempts to promote a wholesale agency, given

in his published "Plan," on which the Purchasing Federation of the north

of England has been founded, relates that "an attempt in that direction

was made (1850) by the Christian Socialists, conspicuous amongst whom were

Edward Vansittart Neale, Professor F. D. Maurice, the Rev. Canon Kingsley,

J. M. Ludlow, Thomas Hughes, Q.C., J. F. Furnival, Joseph Woodin, and

Lloyd Jones. They instituted the Central Co-operative Agency for the

purpose of "counteracting the system of

adulteration and fraud prevailing

in trade, and for supplying to co-operative stores a quality of goods that

could be relied upon, and in the highest state of purity." The

agency did not succeed, and had to be given up, entailing great loss to

its promoters. There was a remnant of the agency left, known as the

firm of Woodin & Co., Sherborne Lane [now of Archer Street], London.

The main object here is to trace the part Rochdale took in

giving effect to the idea. The records preserved in the long-buried

pages of Toad Lane minute books were never very ample. Mr. Smithies, who

was the secretary of the Store in its earlier days, had the Pioneer way of

no more wasting words than money. Frugality in speech is certainly a

virtue, though not usually counted in the list of meritorious economies. Mr. Bamford remarks that "Mr. Smithies evidently never contemplated any

one looking up his records for information in after years." Writers of

minutes in these days might check some tediousness by noticing to this

effect Mr. Smithies' muscular brevity of style. The first entry concerning

the wholesale was made in July, 1853, to this effect:—"That Joseph Clegg

look after the wholesale department." There either was then a

wholesale of some kind in existence, or one was there and then agreed

upon; but only Dr. Darwin himself could trace the descent of the wholesale

species from anterior records here. Mr. Bamford conjectures that the

resolution refers only to the drapery department, as there are frequent

references to the drapery business suggesting it. At a general

members' meeting on September 18th of the same year, it was resolved "to

accept the terms of the conference, and become the Central Depot."

This conference is one supposed to have been held at Leeds. At a

general meeting of members, held the following month, October 23rd, 1853,

the first laws of the wholesale were adopted. The terms in which

they were expressed have interest now. They were as follows:—

" 1.—The business of the Society shall be divided into two departments,

the wholesale and the retail.

"2.—The wholesale department shall be for the purpose of supplying those

members who desire to have their goods in large quantities.

"3.—This

department shall be managed by a committee of eight persons and the three

trustees of the Society, who shall meet every Wednesday evening at

half-past seven o'clock; they shall have the control of the buying and

selling of such goods as are agreed upon by the Board of Directors to be

kept in stock by that department. This committee shall be chosen at the

quarterly meetings in April and October, four retiring alternately.

" 4.—The said department shall be charged with interest after the

rate of five per cent. per annum, for such capital as may be advanced by

the Board of Directors.

"5.—The profits arising from this department, after paying for the cost

of management and other expenses, including interest aforesaid, shall be

divided quarterly into three parts, one of which shall be reserved to meet

any loss that may arise in the course of trade, until it shall equal the

fixed stock required, and the remaining two-thirds shall be divided

amongst the members in proportion to the amount of their purchases in the

said department [leaving out the workers]." [55]

(Signed) JOHN COCKCROFT,

ABRAHAM GREENWOOD,

WILLIAM COOPER,

JAMES SMITHIES, Secretary.

Of course these rules had to be registered, and it is not until the first

Board meeting in 1855 that any reference is made to them, which is done in

these words:—"Resolved,—That we now go on under the new laws." A

quarterly meeting in February following confirmed

this resolution. The next clear reference to the wholesale of that day was

in a minute of a quarterly meeting held April 2nd, 1855, appointing the

following persons as a wholesale committee:—Thomas Hallows, Ed. Farrand,

J. K. Clegg, Jonathan Crabtree, Jno. Aspden, James Meanock, Charles Clegg,

and Ed. Holt. At the Board meeting held April 5th, 1855, the following

minute was passed:—"That the Board meet the wholesale committee next Wednesday night, at half-past seven." The fluctuating fortunes of the

earlier wholesale experiments were many. In the minutes of the Board

meeting held November 8th, 1855, it was resolved, "That a special meeting

be called to take into consideration the propriety of altering the law

relating to the wholesale department." On December 17th, of the same year,

the committee resolved:—"That it is the opinion of the Board that the

15th, 16th, and 17th laws, relating to the whole

sale department, ought to be repealed." At the ensuing quarterly meeting

(January 7th, 1856), at which Mr. Abraham Greenwood was elected president,

the seventh resolution is "That the wholesale department be continued;"

and a committee of seven were appointed "to inquire into the grievances

complained of in the present system

of carrying on the wholesale department." The following persons

constituted the committee:—Samuel Stott, John Morton, John Mitchell,

Edward Farrand, John Nuttall, James Tweedale, and A.

Howard. On March 3rd, 1856, the following were appointed delegates to

attend a Wholesale Conference:—Abraham Hill, David Hill,

Samuel Fielding, and William Ellis. No mention is made of the place where

the conference was held, but the scheme of a new

wholesale society appears to have been discussed there, for at the

quarterly meeting held April 7th, 1856, the members passed the following

resolution:—"That our delegates support the proposition of each member

taking out four shares of £5 each for one representative, at the Wholesale

Conference to be held on April 12th." At an adjourned meeting the

report of the committee appointed to inquire into certain grievances was

accepted with thanks. At a general meeting held May 5th, 1856, the

following persons were appointed on the wholesale committee:—Thomas Lord,

Edward Lord, William Huddlestone, and Jonathan Woolfenden. At the next

Board meeting a committee appears to have been appointed to draw up rules

for a wholesale society, but the names are not given. At the next

quarterly meeting these rules appear to have been considered, as there

is a resolution expunging the word "suggest" from rule 25. The following

resolution was also passed:—"That our Society invest £1,500 in the North

of England Wholesale Society." Mr. Jonathan Crabtree

was appointed the representative. The earlier years in which the wholesale

project was maturing will be of more interest hereafter than now.

On July 7th, 1856, there is a resolution of the quarterly meeting,

empowering the delegates to the Wholesale Conference "to support the laws

drawn up by the committee for a wholesale society, at the next delegate

meeting to be held on July 12th, 1856." On September 4th, 1856, the Board

gave Mr. Cooper authority "to collect the expenses incurred by the

wholesale depot from the various stores." On December 7th, 1857, the

following persons were appointed a committee "to inquire into the

wholesale department":—William Diggle, Samuel

Fielding, Matthew Ormerod, David Hill, and Edmund Hill. The report of this

committee was presented to the quarterly meeting on January 4th, 1858, and

it was decided that the report "be legibly written out and posted in some

conspicuous place, to be read by the

members, and reconsidered at next monthly meeting." The next resolution

passed at the same meeting is, "That the laws relating to the wholesale

department be suspended for an indefinite period." The Board, at its

meeting three days afterwards, decided "That the resolution of the

quarterly meeting respecting the wholesale department be carried out

forthwith." One of the minutes at the adjourned quarterly meeting, held

March 1st, 1858, is, "That the report of the committee appointed to

inquire into the wholesale department be not received."

At the conclusion of the ordinary business of the quarterly meeting, held

April 5th, 1858, the meeting was made special "for the purpose of

rescinding the laws relating to the wholesale department, numbered 13, 14,

15, 16, and 17." The meeting does not appear to have done what it was

called to do, however, for the decision it came to was "That the wholesale

department be not altered." The interpretation of this, Mr Crabtree

thinks, is that we will not kill the Rochdale wholesale department, but let it die quietly. No further

reference is made to it till March 7th, 1859, when a general meeting

passed the following resolution:— "That the question of re-opening the

wholesale department be postponed to an indefinite period." This is the

last reference the minutes contain to the wholesale in connection with the

Equitable Pioneers' Society. In 1863, during the formation period of the

North of England Society, delegates appear to have been regularly

appointed at Rochdale to attend the meetings, and considerable interest

was manifested.

These were the Aztec days of the wholesale idea. The giant we

now know was not yet born. Failure of the idea which cost so much to carry

forward, came in London, as the reader will see below.

Fluctuation beset it in Rochdale. At length a new wholesale arose, whose

statue was as that of Og, King of Bashan, nine cubits and a span (Was not

that his measure?).

The effort made by the Equitable Pioneers' Society in 1852, by initiating

a wholesale department (as has already been related), originated for

supplying goods to its members in large quantities, and also with a view

to supplying the co-operative stores of Lancashire and Yorkshire, whose

small capital did not enable them to purchase in the best market, nor

command the services of what is indispensable to any store—a good buyer,

who knew the markets, and what, how, and where to buy. The Pioneers'

Society invited other stores to co-operate in carrying out practically the

idea of a wholesale establishment, offering at the same time to find the

necessary

amount of capital for conducting the wholesale business. A few stores did

join, but they never gave that hearty support necessary to make the scheme

thoroughly successful. Notwithstanding this counteracting influence, the

wholesale department, from the beginning, paid interest, not only on

capital, but dividends, to the members

trading in this department. However, after a time the demon of all

working-class movements hitherto—jealousy—crept in here. The stores

dealing with the wholesale department of the Pioneers' Society thought it

had some advantage over them; while on the other side, a large number of

the members of the Pioneers' Society imagined they were giving privileges

to the other stores which a due regard to their immediate interests did

not warrant them in be

stowing. Mr. Greenwood's opinion is that the Central Co-operative Agency

and the Equitable Pioneers' Wholesale Department must inevitably have

failed, from their efforts being too soon in the order of co-operative

development.

The above is as brilliant a bit of genuine trade jealousy as the reader

will meet with in ten years' reading. If a society purchasing from the

Pioneers got an advantage thereby, what did it matter that the Pioneers

got an advantage also? If they did not they ought, as it would be a

security that the arrangement could be maintained. Discontent may be

founded on facts, and well founded thereon; but jealousy, vigorous and

virulent, is best sustained on entire ignorance, and generally begins by

imagining its facts—a good plan, too, because then you get them to your mind. Thus it came to pass that the

Pioneers' wholesale scheme, like that of the London Central

Agency, disappeared. Mr. Greenwood, with clear discernment, saw that both

the London and Rochdale wholesale projects must fail,

being too early in the field. When the London Central began there were not

sufficient stores in England to support it, nor when the Rochdalians renewed the attempt in 1852. Therefore Mr. Greenwood waited

ten years, until 1863, when there were 300 co-operative stores in the

United Kingdom, when he demonstrated the possibility of successfully

commencing the great North of England Wholesale Society.

The argument by which Mr. Greenwood commended the new plan of 1864 was of

the same texture as the addition table, usually considered a trustworthy

material. There were in 1861 in the adjacent counties of Lancashire,

Yorkshire, and Cheshire, 120 stores, and an aggregate of 40,000 members;

26 of the largest of these stores did

business to the amount of £800,000. It was, therefore, calculated that if

the weekly expenditure of 40,000 members averaged 10s. weekly (and it was

known to exceed that), it would represent £20,000

weekly, or more than one million a year. There was plainly, then, an ample

field for a wholesale agency to act in.

A calculation was made by Mr. Greenwood of the quantity

of commodities of the grocery kind required to supply the 40,000 members

of co-operative stores then associated in the northern districts.

The calculations were made on the data of goods actually sold in one

quarter at the Rochdale Pioneer Society, in 1863, when it had 3,500

members. This was it:—

|

Kinds of

Articles. |

One Week's

Consumption |

Weekly

Money

Value |

Yearly

Money

Value |

| |

Pounds

(lbs.) |

£ |

£ |

|

Coffee |

6,923 |

266 |

13,832 |

|

Tea |

5,951 |

991 |

51,532 |

|

Tobacco |

4,125 |

825 |

42,900 |

|

Snuff |

108 |

22 |

1,144 |

|

Pepper |

243 |

15 |

780 |

|

|

Hundredweights

(Cwts.) |

|

|

|

Sugar |

1,400 |

3,500 |

182,000 |

|

Syrup, &c. |

400 |

350 |

18,200 |

|

Currants |

107 |

160 |

8,320 |

|

Butter |

717 |

3,440 |

178,880 |

|

Soap |

338 |

524 |

27,248 |

|

|

Totals |

£10,093 |

£524,836 |

There are mentioned in the tables several articles any one of which would

of itself be sufficient to make an agency profitable. The agency would, at

the beginning, supply those articles only upon which there

was a sure profit. It will be seen from the statistics given that the

state of the movement permitted, and, in fact, warranted, a further step

being taken in wholesale progress.

That was Mr. Greenwood's argument. Within the knowledge of the new race of

constructive co-operators, the wholesale house has been twice put up, and

had come down again, because it had not sufficient solid ground to stand

upon. So far as it was in my power to encourage those attempting to

establish the co-operative wholesale, I did it by advising them ever to

plead that they were simply re-establishing it. The best way of inclining

the timid and unenterprising to attempt a new thing is by showing them

that it has been done before, or how nearly it has been done already.

"Men must be taught as though you taught them not,

And things proposed as

new as things forgot." |

No doubt, in this way, we actually encouraged people to suppose that

nothing original or distinctive was being accomplished. Since it required

careful financial demonstration and much perseverance to prove and enforce

it, it was practically quite a new adventure.

The Rochdale Pioneers' Society had then nine grocery branches, all

supplied and managed from the Central Store in Toad Lane. The transactions

between the branches and the Central Store are very simply managed. The

head shopman at each branch makes out a list of all the things wanted on a

form provided for the purpose, and forwards it to the Central Store. The

manager upon receiving it gives directions to the railway or canal

company, where the Store goods are lying, to send the parcels of articles

required to

each branch named on the delivery order. The Central Store in Rochdale

stood in precisely the same relation to its branches as the proposed

agency would do to the federated societies.

Mr. Greenwood pointed to this accomplished fact, and it was finally

resolved to attempt for the third time the formation of a new wholesale

agency. A company was formed under the title of the "North of England

Co-operative Wholesale Industrial and Provident Society Limited." The Wholesale has now become like the historic and

untraceable Nile—the Lord of Stores, as Mr. Stanley calls the great river

the Lord of Floods. By the assistance of explorers, Mr. S. Bamford, Mr.

James Crabtree, and Mr. A. Howard, as adventurous in their way as any who

have preceded Mr. Stanley, we have been able to trace the sources of the

great commercial water which irrigates all the stores it touches, as the

Nile itself irrigates the shores it laps.

There were in the Rochdale Society, in 1864, when the Manchester Wholesale

took a tangible shape, many who had steadfastly opposed the development of

the wholesale department. These belonged largely to the new members, who

did not look with favour upon the establishment of a Wholesale Society at

all, and, although not strong enough to prevent the Rochdale Society from

taking up

shares, were successful in hindering the development of a business

connection such as the movement naturally expected from Rochdale. The

influence of Rochdale in the wholesale appears in this, that it looked to

Rochdale for officers. Mr. Samuel Ashworth, the manager of the Rochdale

Store, was solicited to take charge of the Wholesale

Society's business in Manchester. The wholesale department in connection

with the Rochdale Society had ceased operations at that

time. He was unwilling to go unless the committee of the Rochdale Society

would undertake to reinstate him in his position provided

the experiment did not succeed. [56] This guarantee not being consented to,

he did not go. Some months later he had another opportunity of going to

Manchester, which he accepted. [57]

We need not discuss here the Jumbo Farm theory [58] of the origin of the

wholesale at certain meetings held there. That the subject

was considered there, as at other places, there is no doubt. Mr. Marcroft,

himself connected with the wholesale, supposes that it was devised at

meetings held at that peculiar farm. But the road of our narrative lies

through official facts. At the first meeting of the North of England

Wholesale Society, held in Union Chambers, Manchester, December 10th,

1863, Mr. Thomas Cheetham was appointed Chairman, and Mr. Abram Greenwood,

President; James Smithies, Treasurer; John C. Edwards, Secretary. Messrs.

John Shelton, William Marcroft, Charles Howarth, and Thomas Cheetham were

the Committee. Here are a cluster mostly of familiar and

historic names in constructive co-operation. Four years later a resolution

was come to that the prospectus of the Wholesale Agency should be publicly

advertised. The following extract from the Society's minutes shows when

and in what terms it was resolved upon:—

Copy of first minutes of adjourned committee meeting, March 2nd, 1867:—

"Present: A. Greenwood, James Crabtree, John Hilton, James Smithies,

Edward Hooson, Edward Thomason.

"Resolved: lst—That the prospectus be published as an advertisement in

the Co-operator until further notice."

The concluding part of this advertisement, which first appeared March

15th, 1867, contained the following words:—

"[Mr. Abraham Greenwood, of Rochdale,

must be regarded as the principal originator of the Co-operative Wholesale

Society, of which he has ever since been the President.] In the

Co-operator for March, 1863 (vol. 3), Mr. Greenwood propounded his

plan for a

wholesale agency, which, with some modifications, formed the basis of the

present admirable organisation."

The first part, which is put here in brackets, was drawn by Mr. Smithies

and Mr. Edwards, two of the most competent persons who could have written

it, for their knowledge of its truth is undoubtable, and their concurrence

in the statement is conclusive. The part following the brackets was

written by Mr. Henry Pitman, as there were copies of the Co-operator

mentioned on hand, which it was thought desirable should be further

circulated. This conclusive and unchallenged testimony, repeated year

after year, renders future

doubt or denial absurd. When the notice was discontinued, it was done on

the authority of the following minute:—

Copy of first minute of committee meeting, held October 16th, 1869:—

"Present: Messrs. Greenwood, Baxter, Fox, Hooson, Crabtree, Thomason,

Sutcliffe, Swindels, and Marcroft.

"Resolved: lst—That no co-operative or other agency be added to our

advertisements in the Co-operator."

No objection was raised at this meeting, or had been at any meeting, as to

the fact of the authorship of the wholesale. Neither Mr. Marcroft nor any

other person raised a question as to its truth. It was discontinued, Mr.

Crabtree explains, not because its truth was ever questioned, but because

it was deemed no longer necessary. It was suggested that there was no further need for it to appear, "as it would now have served all that was intended."

No historic fact could well be more conclusively established, more

continuously advertised by common consent, than this has been, that Mr.

Greenwood was the "principal originator" of the wholesale.

All who had personal knowledge of the development of co-operation during

the past thirty years were quite aware that the credit of originating the

wholesale, and the working and organisation, belonged to Abraham Greenwood

more than to anyone else. The conclusive and well-written letter of Mr.

Edwards, in the Co-operative News of July 17th, 1875, is quite sufficient

testimony to set that matter at rest. Only those—to use Mr. Edwards'

expression—who had a strong weakness for believing, in spite of evidence

to the contrary, could entertain a reasonable doubt thereupon. Next to

Abraham Greenwood I should place James Smithies. Smithies, like most of

the early co-operators, was a modest man; but though modest he was not

weak, and he could always be depended upon to indicate justly what share

each of his colleagues had borne in their common work. He had himself

devised plans for federating purchasers. He had collected copies of the

plans of others. He was for years secretary of committees for giving

effect to the idea.

In a movement in which an important development is carried out mainly by

the sagacity and persistent efforts of one person, it is in the interest

of all that credit should be given where it has been

earned. When Mr. Abram Greenwood first drew up the scheme of it, and put

into coherent form the fragmentary conceptions of others, he set forth,

for the first time, an intelligent scheme of working principles. He had,

to use his phrase, "to stand the fire of the criticism, doubt, and

distrust of the plan, of which no one else was willing to undertake the

responsibility or defence of. Since it became successful, sponsors for

it and originators of it have sprung up from Jumbo Farm to Cronkey Shaw,

and generally elsewhere.

Mr. Howard has an ingenious theory that the nature of the residences of

the co-operators can be determined from the books of the stores, which

record the amount of their savings. Those members who have the highest

balances are found to be persons who live upon the hills which abound in

the town. If a member has a low

balance, he is found to live in the low lands. If his balance is high,

so is the altitude of the place where he resides. If a member has

no balance, it ought to follow that he lives underground. I am told the

figures in some societies do favour this theory, and that high

balances and elevated dwellings do go together. If this be true, it is

probably owing to the greater clearness of the climate on the hill, better

enabling members to see their way to save. I remember now that Mr.

Greenwood always lived in some elevated part of the town, which, no doubt,

enabled him to take comprehensive views of the wholesale before the

cogitators of Jumbo Farm (which, if I remember rightly, is a low-lying

place) got sight of it.

The sense in which it appears to me Mr. Greenwood is to be regarded as the

main founder of the wholesale is that of his having been the advocate of

it, and known to be distinctively the advocate of it, during more years

than any other person laying claim to its origination. He kept it in mind

himself from the time (1850) when the project was first formally discussed

in Rochdale and London, and during all subsequent years of its trial,

which preceded its final establishment in 1864. He not only kept the idea

in his own mind, but kept it in the minds of others, when otherwise it

would have lain in abeyance. His calculations mainly proved it to be a

feasible undertaking. His statement of the possible mode of working it was

the first which seemed complete and practicable. James Smithies, William

Cooper, Lloyd Jones, George Booth, W. Marcroft, Mr. Ashworth, Charles

Howarth, Thomas Cheetham, Mr. Edwards, Mr. Stott, William Nuttall, and of

later years, James Crabtree, A. Howard, J. T. W. Mitchell, and others,

should all in fairness be included; whose sagacity and energy have

contributed to its origination and development. All the leading thinkers

of the Rochdale Store were undoubtedly concerned in furthering the great

project by plans, suggestions, and advocacy.

If I could collect a list of all the names of persons who have promoted

the prosperity of the wholesale, I should insert them. Mr. Field, of Mossley, was on the committee three or four years, and

was deemed a good member. Mr. John Hilton also served four or five ,years. Mr. Marcroft, as we have seen, was upon it. Mr. Charles Howarth, who was

also upon the committee, ceased after a time to be so, because he was a

dealer in soda, which was some

times purchased by the agency. Mr. Edwards shared in the heat and burden

of the service of the wholesale four or five years. Several names occur

incidentally in committees which have been quoted, which the co-operative

reader will recognise as those of

distinguished promoters of the wholesale. Mr. Mitchell, of Rochdale, and

Mr. James Crabtree, of Heckmondwike (who has both faith and pride in

co-operative principle), have both been chairmen of the wholesale.

-XXI-

CO-OPERATIVE ADMINISTRATION.

THE Almanacs of the Pioneers' Store—quite worthy of

being preserved and bound for reference—give a curious picture of its

progress, vicissitudes, and the manner of the Pioneer mind from time to

time. The 1854 Almanac gives a complete statement of the "objects

and rules" of the Society, as they stood in force exactly in the tenth

year of its existence. They are expressed with clearness and

conciseness. All clearness is not concise, and some conciseness is not

clear; but these Almanac expositions possess both, as the reader has seen

on p. 11.

By the rules of the Society a person proposed and his

character and qualifications duly discussed, and not accepted, had his

entrance shilling returned. The good-natured Society debated his merits

and demerits gratuitously. One would imagine that a person whose virtues

were not generally admitted, or not very obvious, would gladly pay a

shilling for having them inquired into by this willing association, so

that he might know how he stood among his class. Each member has to take

five one-pound shares. How many stores have languished for years, flabby

in pocket and lean in limb; because its shabby-minded members starved it

by hardly subscribing one pound each. Many societies are pale in the face

for want of the nourishment of capital which a wise five-pound rule would

have brought it. [59] These are the Rochdale

rules:—

"2. Any person desirous of becoming a

member of this Society shall be proposed and seconded by two members, and

if approved of at the next general meeting by a majority then present,

shall be admitted to membership. A person proposed and not making

his appearance within two months shall forfeit his proposition money, and

shall not be admitted to membership unless again proposed. Each

person, on the night of his admission, shall appear personally in the

meeting-room, and state his willingness to take out five shares of one

pound each, and conform to the laws of the Society, and pay a deposit of

not less than one shilling.

"3. That each member shall have five shares in the capital of

the Society, and not more than fifty shares.

"4. That the capital be raised in shares of one pound each.

"5. That each member pay not less than threepence per week,

or three shillings and threepence quarterly, until he have five shares in

the capital of the Society. Any member neglecting to pay as above,

except through sickness, distress, or want of employment, shall be fined

threepence.

"6. That two pounds of each member's investment be permanent

or fixed capital.

"7. That three pounds may be withdrawn at the discretion of

the Board.

"8. That members may withdraw any sum due to them above five

pounds according to the following scale of notice:—One pound five

shillings on application to the Board; one pound five shillings to two

pounds ten shillings, two weeks. And larger sums on giving longer

notice; from forty to forty-five pounds being to be had or twelve months'

notice.

"16. That meetings on the first Monday in January, April,

July, and October be the quarterly meetings of the Society, at which

meetings the officers shall make their quarterly report, in which shall be

specified the amount of funds and value of stock possessed by the Society.

"23. [60] The officers of this Society

shall not in any case, nor any pretence, either sell or purchase any

article except for ready money. Any officer acting contrary to this

law shall be fined 10s., and be disqualified from performing the duties of

such office.

"32. That the profits realised by the Society be divided

thus:—Interest at the rate of 5 per cent. per annum shall be paid on all

shares paid up previous to the quarter commencing. The remainder

shall be divided amongst the members in proportion to the amount of their

purchases at the Store during the quarter."

The last is the rule which introduced into England and into

all store practices the new policy of dividing profits on purchases.

The 1854 Almanac also contained the economical

announcement, of which the like had never appeared in Great Britain (and

would be difficult to find elsewhere in 1877), namely, that the news-room,

a bounteously filled room in those days, abounding in dailies, weeklies,

and quarterlies, was open from nine in the morning until nine at night, at

a charge of twopence per month. As this room was, and still is, open

on Sundays as well as week days, this gave an average of 2,520 hours'

reading for twopence; or 600 hours, with fire and light, for one

halfpenny. Co-operative information is the cheapest the working

class over found, if regard be had to convenience of hour and day; and the

quality of it is higher, because two-sided, than gentlemen can usually

command. More wanting in intellectual boldness than workmen,

gentlemen's news-rooms and libraries are subjected to clerical censorship,

who, with the best intentions, impose the impotence of half-knowledge upon

the members who do not think it "good taste" to object to it or demand

"forbidden books." In all Scotland there is not a single public

library or news-room, in city, or club, or college, where periodicals and

books on both sides of theology and politics can be seen. Nor would

co-operators be in the freer and manlier state they are, did not their own

money buy their books, and build their news-rooms and libraries, and their

own members administer their affairs themselves. Owing nothing to

anyone, they fear nobody, nor suffer intellectual control by any.

The honourable feature of the Pioneers is that they did

not go back, they went forward. The Almanac, the yearly manifesto of

the Society, said:—"The objects of this Society are the social and

intellectual advancement of its members. It provides its members

with groceries, butchers' meat, drapery goods, clothing, shoes, clogs.

They have competent workmen on the premises to do the work of the members

and execute all repairs. The profits are divided quarterly: 1st,

interest, five per cent. per annum on all paid-up shares; 2nd, 2½

per cent. off net profits for educational purposes; remaining

profits divided amongst the members in proportion to money expended.

For the intellectual improvement of the members a library has been formed,

consisting (1877) of more than 3,000 volumes. The library is free to

all the members."

Mark, the objects are "the social and intellectual

improvement of members," as well as their secular betterance.

"Social and intellectual" improvement was a wholesale phrase put there or

kept there by Mr. Abram Howard.

Their library soon grew to 3,000 volumes. The

newspapers and periodicals increased in number; and they have discovered

how to make reading cheaper than 2,000 hours of it for twopence.

Reading is now "free," and the library thrown into that. The Almanac

of 1861 announces that globes, maps, microscopes, and telescopes are now

added, so that the co-operator can look into things small and great, far

and near. The gentlemen of Rochdale had no such institution for

their use.

It is that golden rule for the division of profits which

includes 2½ per cent. off net gains for

educational purposes, which has exalted the Rochdale Society above all

others, made its wise example so valuable, brought it so many friends, so

much fame, and kept it from being overrun by fools or uninformed members,

who else would long ere this have destroyed it, on the ground that

intelligence does not pay. Not having any themselves, and not

knowing what it means, they naturally take this view. They think

dividends sufficient without knowledge, not knowing that without knowledge

there would be no dividends, either in co-operative stores or elsewhere.

When the cotton famine began to gnash its lean jaws in 1862,

the forecasting and confident co-operators came out—in that penurious

year above all others—with their golden Almanac. Mr. Smithies

and Mr. Cooper both sent me copies with pride. It was printed in

gold on a blue ground. It mentioned a "Wholesale warehouse at 8 Toad

Lane, and, for the first time, gave a central compartment to the

educational department." It recounted that the library had grown to 5,000

volumes, that a reference library of most valuable works had been added,

that the news-room contained fourteen daily papers, thirty-two weeklies,

and monthlies and quarterlies of all

kinds, representing all opinions in politics and religion. The co-operators

wisely set themselves against being made into half-minded

men. They would not imitate those timid creatures who are afraid to know

the other side of the question, and go squinting at truth all their days,

never looking it square in the face, so that when they

meet it right plain in their way they do not know it. Opera glasses,

atlases, and stereoscopes are now provided for the use of members, and for

a small fee they can take them away, as well as microscopes

and telescopes. The slave war was then waging, and if a slave owner's agent

came their way, as many of them did, the co-operators had telescopes to

discern his approach, and microscopic instruments ready to examine him

when he arrived.

Things generally had a vagabond appearance in

Lancashire. The outlook for an operative was bad, and destined to be

worse. The golden Almanac said so, and gave this excellent advice to

co-operators:—

"1. Let your earnings be spent only on strict necessaries. Cut off

everything else.

"2. Withdraw sparingly of your accumulated savings.

"3. Make the best use of the time thrown on your hands for your

intellectual improvement, means for which are provided in our library and

news-rooms.

"4. Add to the honour of our movement, by waiting patiently for the better

time which will one day come"

And they did wait. No venal or other agitators ever won co-operators to

join in any clamour that the Government should intervene on behalf of the

south, in order to bring cotton to Lancashire and

Yorkshire. A week's clamour would have turned the scale against

the slave. It made the nation proud of English working men to see the

stout and generous silence they kept. The advice I have quoted was

addressed "to the co-operators of Rochdale and the nation." It is the only

time they acted on their well-earned authority to speak in this manner to

the outside world.

A Sick and Burial Society was commenced before 1860. Provision

for relief during sickness and also for decent interment at the death of

any of its members are the cares of the co-operators. None but members of

the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers, or their families, can enter this Society; but a member may withdraw from the Pioneers' Society without losing his

or her membership in this. Contributions, of course, vary according to age; and the tables are based upon authorised calculations. The Pioneers have

always had among them a creditable taste for temperance, and had the

Society's meetings held at the board-room to prevent pay nights turning

into tippling nights at a beerhouse, which soon brings members on the

"box" of the sick club. The founders of the Society were too shrewd to

think that anything would be saved by insuring saturated subscribers. Dry

members pay best. The Almanac of 1862 stated that "meeting at

public-houses was neither suitable nor consistent with the objects of a

sick and burial society—an appetite for drink and company bring on

disease and premature death." The Pioneers meant their arrangements to be

"suitable and consistent with a society whose interest rather is the

prevention of sickness and burials. Tippling is alone suitable and

consistent with a society whose objects

are promoting sickness and burial. Temperance in drink is sensible; it is

fuddling which is foolishness."

A House Society is another feature of Pioneer organisation. Improvement

in England grows fast out of grievance. Reason seldom or never creates it. If, indeed, pure intellect discovers a new course, it generally remains

barren until some irritation drives men into it. The Land and House

Society began this way. One of its founders relates that a certain

gentleman who was a shopkeeper, was also an owner of cottages, some of

which were occupied by members of "co-operative societies," who were in

the habit of receiving store profits. He, in an unwise hour, declared that

"they should not have all the dividends to themselves; he would have a

part of them by advancing their rents 3d. per week." If it be weak to wait

for an outrage before you do a sensible thing, it is undoubtedly a proof

of some spirit to take steps to make the repetition of the outrage, when

it does occur, impossible in the future. This is what the

Pioneers soon did. They formed a society, and began to buy land and put up

houses for themselves. Their rules give power to build, buy, and sell

houses, workshops, mills, factories, or to purchase, lease, or rent land

upon which to erect such property. Their proposed

capital was £25,000, in shares of £1. Thirty-six cottages were put

up before 1867, covering the whole of the land they then held. Their

erections were an improvement on the generality of cottages then built. Subsequently they have built a co-operative town.

The Irish Times of 1868 remarked in a leader by the editor,—"We have

before us an Almanac for 1868, published for the use and information of

its members by the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers' Society, Limited. It is a

sheet Almanac, illustrated with a view of 'The new Central Store,' a

cut-stone building 70 feet high, and

bearing some resemblance to the stately edifice belonging to the Hibernian

Bank, in College Green. This building cost the Rochdale Pioneers

£17,000. Some idea of the wonderful effects of the co-operative

system, duly and honourably carried out, may be formed from some facts

stated by the Directors, who are all working men, in an address published

in the Almanac."

After recounting what the business and profits of the Society then were,

the editor adds:—

"The capital is so large and so rapidly increases that the Directors are

now spending £10,000 as a beginning in the erection of a good class of

cottage houses for artisans, and they have purchased a small estate within

the borough of Rochdale, which is to be laid out for building immediately.

The quality and construction of the houses are greatly superior to any

erected for the working class in Rochdale before the Pioneer time,"

excepting, perhaps, a pleasant, wide-windowed and healthy range erected by

Mr. Bright for his workpeople.

The early co-operators in Rochdale took with regard to their buildings

what used to be called "the bare-bone utilitarian view," like that which

Abram Combe took at Orbiston. They were content that their store should be

of the plainest kind, indeed, they had an early resolution on their

minutes, "not to spend a farthing on finery." This was a wise resolution

then, because they had not the farthing by them. Besides, the instinct of

art hardly existed among the

working class in those days. They thought refinement of taste belonged

alone to the rich; they did not know that the rich were often vulgar, and

that refinement was a property of the mind, and that the

poor might have it as well as the wealthy. They did not know that

plainness, grimness, and ugliness were more expensive than modest

comeliness and modest taste. Their central stores and their branch stores

are well and substantially built now; but had it occurred to their

architects, they might have made them brighter, and still more

graceful, at less expense. It would be a benefit to society if a few

architects were publicly hanged in half-a-dozen places, as Voltaire said

of Admiral Byng, "for the encouragement of others."

The observations by the Irish editor quoted, are all founded upon one

Almanac, that of 1868. Much that has been written upon Rochdale has been

suggested in like manner by a stray copy of this annual calendar of the

year falling under the notice of persons who became

interested by its unexpected contents. The Almanac has been the

annual manifesto of the Store. It has been the sole historical publication

of the Store.

In Part I. of this history, the part published twenty years ago, at

p. 58,

it is represented that the loan asked of Mr. Coningham, then M. P. for

Brighton, fell through because their securities were naturally required to

be submitted to the examination of Mr. Coningham's solicitor, and the

"Board refused to have anything to do with a lawyer." No doubt this

distrust of lawyers existed. But this was not the exact reason why the

solicited loan came to an end. It is not of moment now;

but I am unwilling to leave on record unrevised any statement which

subsequent information has shown me to be incorrect. Mr. Coningham has

sent to me the following letter which he received at the time, and which

puts the fact accurately:—

13, George Street, Rochdale,

14th October, 1851.

Sir,—I am directed by

the members of the "Rochdale District Corn Mill Society" to return their

thanks for your offer and anxious desire to meet their wishes relative to

the loan of £500.

You will find by the enclosed letter we received from your solicitor,

Edward Tyler, Esq., however willing we may be we cannot give the property

of the Society in security. This the members regret, for it precludes them

from getting that help which they at this time greatly require. But yet

the members would esteem it a great favour if you, on the good faith of

the Society, advance to it £200, to be repaid by quarterly instalments of

£50, which would repay the loan in 12 months.—Respectfully yours,

W. Coningham, Esq. ABRAHAM GREENWOOD.

When Abraham Lincoln became

President of America, his familiar-tongued countrymen dropped out the "ha,"

and reduced him to the more manageable name of "Abram." Since Mr.

Greenwood has oft been president of the various wholesale and other

co-operative projects, he also has been called "Abram," and it has been

the above letter, bearing Mr. Coningham's endorsement (I send the original

to the printer), written twenty-six years ago, that enables me to furnish

historical proof that Mr. Greenwood's rightful name is the good old

resonant, Hebraic, patriarchal, three-syllabled name of Abraham, the most

honoured name in Lancashire neat to "Mesopotamia."

In the first part of this history, mention was made of the Christian

Socialists, the professors, lawyers, clergymen, and other members of that

party. It is a duty to acknowledge now how much the movement has been

indebted to the generous zeal and devotion which, during the twenty

succeeding years, they have continued to promote, which in various places,

in this narrative and elsewhere, has been ungrudgingly acknowledged.

On Mr. Ashworth's appointment at the Wholesale, Manchester, Mr. Brierley,

of the Brickfield Equitable Society, became manager. He began his duties

when the progress of the Society was in full course. The local policy was

changed. New notions of making dividend by seeking cheaper markets, with

risk of worse quality, were permitted.

The rules were altered to the effect that interest on invested capital of

five per cent. should only be paid in certain fixed proportion to the

amount of the member's quarterly purchases of provisions

or goods at the Store. Thus, if a member had invested £60 in the capital

of the Store, and his purchases amounted to only £1 a week during the

quarter, he only received interest on £8 of his capital

invested, and the other £47 paid him nothing. One reason for this

singular rule was a distrust or jealousy of capitalists. It is a curious

feature in the working class that at one time their great grievance is

that they have no capital (which is always a grievance to any persons in

that state), and, next, they use all their ingenuity to devise rules for

getting rid of capital, which we wanted for establishing co-operative workshops. They grow afraid of their friend. The

rules herein questioned had the merit of answering the purpose intended. The members who could not eat up to the required amount, and could not

otherwise augment their purchases sufficiently,

began to draw out their capital which yielded no return. The result was

that, in 1869-70, £100,000 were withdrawn, and £30,000 more

was under notice. It will surprise the un-co-operative reader to find that

the members of the Store had so large an amount of money. In due time good

sense got uppermost, as it often has done in Rochdale. The members had the

disturbing rule rescinded. [61] From June, 1870, business and prosperity

returned to its usual standard

of growth; the capital has more than doubled again. Mr. Joseph Booth, of

the Hyde Store, son of Mr. George Booth, of Middleton,

has succeeded as manager. Mr. Brierley set up a rival society in the

town, of which he is manager. But the Rochdale Society continues to

prosper in its own enduring way.

About the years 1859 and 1860, Mr John Bright took, as he had often done

before, considerable interest in the progress of the Pioneers' Society. He

knew several of the workpeople of his firm with whom, as old servants, he

was on friendly and conversational terms; and sometimes the affairs of the

Store were the topic of his remarks. He said some of his friends in the

Metropolis and other parts of the country expressed doubts as to the

financial soundness of the Society, and based their doubts upon the fact

that the accounts were only

audited by members. He hi himself had no misgiving concerning them; but he

thought it might give confidence to other persons who were both willing

and able to speak well of the movement, but who desired to be certain that

the statements made were verified

by some acknowledged public auditor. This was talked about among the

leading members, and ultimately, on the appointment of the auditors in

January, 1861, the matter was mentioned, and the appointment of a public

accountant was moved and carried, mainly through the influence of the

reported remarks of Mr. Bright.

Mr. Frank Hunter, of Bacup, was appointed. The books were not entered up

in a systematic manner, and Mr. Hunter had to bring out the whole of the

strength of his office. The great number of the entries in the share

accounts were more than he was prepared to find, and the number of the

entries in the share accounts were such as he had had no former experience

of. He wanted to take all the books away, but could not be permitted. When

Mr. Hunter's report was produced it

showed a sum of £200 unaccounted for. Mr. Cooper said it could not be

correct, but the error could only be discovered by a fresh

audit. Mr. Ashworth and the President went to see Mr. Hunter

to ask him to show them how he had arrived at the result. He

could give no particulars. He had corrected a number of members' share

books without keeping account of the corrections, nor could

he give any clue to the mystery. After much trouble and research it was

discovered that Mr. Hunter had made a mistake by inserting on the credit

side of the trade account an item of £70 odd as sales, which ought to have

been entered on the debit side of purchases. It is not difficult to

understand that if an auditor puts down £70 as received which the cashier

had actually paid, that would make an error against him of £140. But

all the cash was there. Mr. Hunter acknowledged in a letter his

mistake, and the Society was satisfied. Since that time the Society

has been satisfied with the audits made by those appointed; besides,

auditors have subsequently been better paid. [62]

It will be clear to the reader that Mr. Bright did great service to the

Society by the discerning practical suggestion which he made. At that time

doubts were often expressed as to whether co-operators, being working men,

understood enough of book-keeping to render a sound financial statement of

their affairs. This short story, the financial verification of the

Rochdale Society, is a necessary part of its history.

The following table shows at a glance the progress which the Society has

made from 1844 onwards:—

|

Year |

Members |

Funds (£) |

Business (£) |

Profits incl.

interest (£) |

|

1844 |

28 |

28 |

… |

… |

|

1845 |

74 |

181 |

710 |

22 |

|

1846 |

80 |

252 |

1,146 |

80 |

|

1847 |

110 |

286 |

1,924 |

72 |

|

1848 |

149 |

397 |

2,276 |

117 |

|

1849 |

390 |

1,193 |

6,611 |

561 |

|

1850 |

600 |

2,289 |

13,179 |

880 |

|

1851 |

630 |

2,785 |

17,633 |

990 |

|

1852 |

680 |

3,471 |

16,352 |

1,206 |

|

1853 |

720 |

5,848 |

22,700 |

1,674 |

|

1854 |

900 |

7,712 |

33,374 |

1,763 |

|

1855 |

1,400 |

11,032 |

44,902 |

3,109 |

|

1856 |

1,600 |

12,920 |

63,197 |

3,921 |

|

1857 |

1,850 |

15,142 |

79,789 |

5,470 |

|

1858 |

1,950 |

18,160 |

74,680 |

6,284 |

|

1859 |

2,703 |

27,060 |

104,012 |

10,739 |

|

1860 |

3,450 |

37,710 |

152,063 |

15,906 |

|

1861 |

3,900 |

42,295 |

176,206 |

18,020 |

|

1862 |

3,501 |

38,465 |

141,074 |

17,564 |

|

1863 |

4,013 |

49,961 |

158,632 |

19,671 |

|

1864 |

4,747 |

62,105 |

174,937 |

22,717 |

|

1865 |

5,326 |

78,778 |

196,234 |

25,156 |

|

1866 |

6,246 |

99,989 |

249,122 |

31,931 |

|

1867 |

6,823 |

128,435 |

284,912 |

41,619 |

|

1868 |

6,731 |

123,233 |

390,900 |

37,459 |

|

1869 |

5,809 |

93,423 |

236,438 |

28,642 |

|

1870 |

5,560 |

80,291 |

223,021 |

25,209 |

|

1871 |

6,021 |

107,500 |

246,522 |

29,026 |

|

1872 |

6,444 |

132,912 |

267,577 |

33,640 |

|

1873 |

7,021 |

160,886 |

287,212 |

38,749 |

|

1874 |

7,639 |

192,814 |

298,888 |

40,679 |

|

1875 |

8,415 |

225,682 |

305,657 |

48,212 |

|

1876 |

8,892 |

254,000 |

305,190 |

50,668 |

|

1877 |

9,722 |

280,275 |

311,754 |

51,648 |

|

1878 |

10,187 |

292,344 |

298,679 |

52,694 |

|

1879 |

10,427 |

288,035 |

270,072 |

49,751 |

|

1880 |

10,613 |

292,570 |

283,665 |

48,545 |

|

1881 |

10,697 |

302,151 |

272,142 |

46,242 |

|

1882 |

10,894 |

315,243 |

274,627 |

47,608 |

|

1883 |

11,050 |

326,875 |

276,456 |

51,599 |

|

1884 |

11,161 |

329,470 |

262,270 |

50,268 |

|

1885 |

11,084 |

324,645 |

252,072 |

45,254 |

|

1886 |

10,984 |

321,678 |

246,031 |

44,111 |

|

1887 |

11,152 |

338,100 |

256,736 |

46,047 |

|

1888 |

11,278 |

344,669 |

267,726 |

47,119 |

|

1889 |

11,342 |

353,470 |

270,685 |

47,263 |

|

1890 |

11,352 |

362,358 |

270,583 |

47,764 |

|

1891 |

11,647 |

370,792 |

296,025 |

52,198 |

The progress of the Store shown in columns was first done on my

suggestion, and Mr. T. S. Mill put in his "Principles of Political

Economy" this table down to 1860.

-XXII-

THE BRANCH STORE AGITATION.

THE Society soon came to possess fourteen or more

Branch Stores and nearly as many news-rooms. But how came these

Branches into being? Did they come by spontaneous generation or

evolution, or development of species process, silently and naturally; or

were they the offspring of discussion, with agitation for accoucheur?

The following facts will enable the reader to judge:—

It was in the year 1856, when the receipts at the two Central

Stores had amounted to £1,000 per week, that the members began to talk of

having shops opened in other parts of the town, more convenient to their

residences.

Many of the members lived at great distances, and the labour

of carrying their weekly purchases from the stores in Toad Lane had been

freely undertaken while there was no economy in having more than one shop.

But now the shop was crowded every night, and the day was scarcely long

enough for the shopmen to make the necessary preparations for the night's

work.

Discussions arose on which part of the town the first Branch

should be opened; it was soon decided. A numerously signed memorial

from the members on the Castleton side of the town was presented to the

quarterly meeting, held in June, 1856. The prayer of the

memorialists was granted, themselves being at the meeting in great

strength to promote it and support it by their votes. Indeed, this

has been the case in the opening of nearly all the Branches, and is a

notable feature in the democratic character of our institution.

A shop in Oldham Road was procured, and was opened No. 1

Branch for the sale of grocery goods on the 7th day of October of the same

year. The business at this new Branch soon outgrew the premises

which the committee had rented, and it was soon seen that further steps

would have to be taken in the same direction.

There was on the Castleton side of the town a society which

had been formed in the earlier years of the Pioneers' Society. It

was called "The Castleton Co-operative Society." It was doing but a

small business. I believe it was in the year 1855 it was irregularly

assessed by the Income Tax Commissioners on a profit of £45, and compelled

to pay at that time.

The greater popularity of the larger society threatened to

swallow up this small society, and now when the Branch movement had begun,

an agitation was set on foot for amalgamation. The result was that

the business and premises of the Castleton Society were taken up by the

Pioneers, and the Store was opened on March 7th, 1857, as the No. 2 School

Lane Branch. It still retains the name, although a new store has

been built in another street a considerable distance away.

The new idea of Branches gained ground so fast that two more

were opened within the next few weeks, No. 3, in Whitworth Road within ten

minutes' walk of the Toad Lane Stores, and the first on the same side of

the town; and No. 4, Pinfold Branch, being in another part of the township

of Castleton.

The latter Branch was opened on the 2nd June, 1857, but no

further steps were taken in this direction till the beginning of the year

1859. Although great relief had been given to the Central Stores by

the opening of the four Branches, yet the increase of members and business

continued at such a rate that further relief was now found to be

necessary.

The Castleton side of the town was well served. Only

one Branch had been established on the same side as the Central was

situated, and it was now argued that they might extend in the Spotland

direction. After some opposition, and great difficulty in finding a

suitable shop, the Spotland Bridge Branch, No. 5, commenced business on

the 17th February, 1859.

The agitation for another Branch at Bamford was immediately

commenced. This was, indeed, an agitation, inasmuch as it involved a

new principle—that of the Pioneers opening shops in the neighbourhood of

other societies.

At a small village, situate but a short distance from

Bamford, there was one of those small societies formed very early in the

new history of the movement, and must have been in existence a

considerable number of years at the time when the memorial for a Branch at

Bamford was being signed. The memorial was signed by a great many of

the members of the Hooley Bridge Society, and a great many more opposed

it. It was seen at once that if the Pioneers opened a shop here it

would be the death-blow to their small Society. The principle of

self-government was set against the principle of economy on the side of

the memorialists. While on the side of their opponents in the town

it was urged that it would not be fair to charge the Society's funds with

the cost of carrying the goods to such an outlying Branch, when members

who lived at great distances in other directions had to carry their own,

but more especially would it be wrong to open such a Branch so near a

neighbouring society at which the memorialists could not only make their

purchases, but where they could take a more active share in the management

than was possible for them to do in the Rochdale Society.

The memorialists, however, succeeded, and at the April

Quarterly Meeting, in 1859, it was decided to open a shop at Bamford.

The announcement of the voting was received with an outburst of applause

from the supporters of the memorial.

No one seems to have thought of the danger of this example of

overlapping which has wrought much mischief since. A Store is better

than a Branch since the Store develops local energy and business

education. A federation of Stores around a wholesale centre is

better than Branches.

I have dwelt longer on the circumstances attending the

opening of the No. 6 Bamford Branch (which took place on May 26th, 1859),

because it settled the principle that the Society might safely carry its

Branches to such places beyond the boundaries of the town where the

members residing in the neighbourhood could guarantee a certain weekly

business, such as would give fair employment to a shopman.

The sixteen Society's Branches were opened as follows:—

|

Oldham Road |

No. 1 in |

1856 |

|

School Lane Branch |

2 |

1857 |

|

Whitworth Road |

3 |

1857 |

|

Pinfold |

4 |

1857 |

|

Spotland Bridge Branch |

5 |

1859 |

|

Bamford Branch |

6 |

1859 |

|

Wardleworth Brow |

7 |

1860 |

|

Bluepits |

8 |

1860 |

|

Buersil |

9 |

1864 (?) |

|

Shawclough |

10 |

1866 |

|

Sudden |

11 |

1869 |

|

Newbold |

12 |

1872 |

|

Milkstone |

13 |

1872 |

|

Slattocks |

14 |

1873 |

|

Gravel Hole |

15 |

1874 |

|

Norden |

16 |

1875 |

At ten out of the sixteen there are commodious shops, which

the Society has built from its own funds, and two more where the premises

are its own by purchase. At the remaining four the business is

conducted in rented shops. There are news-rooms at twelve of them,

and preparation is being made at another. [63]

Four or five of the branches do a business under £2,000 per quarter, but

the rest vary from that sum to £5,500 per quarter.

The Branch system has been of great service to the members,

and there is no doubt but it has been a principal means of the rapid and

ultimately secure development of the Society's progress.

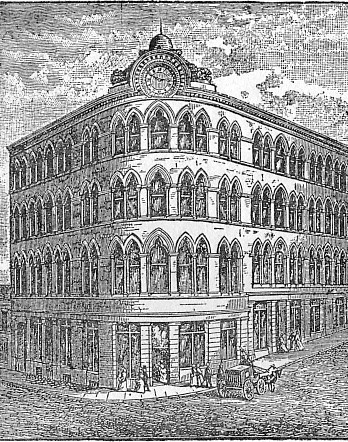

The Central Store from which the Branches radiate is a very

interesting building. There is a meeting-room at the top, covering

the whole area of the building. It is capable of seating at least 1,400

persons, and has often held meetings of 2,000 and upwards. This

meeting-room affords a commanding view of the town which is seen from 15

lofty windows. The library contains 12,000 volumes.

The building was commenced in the beginning of 1866, and

opened in September, 1867. The whole cost including site was

£13,360; all or the greater part of the cost has long since been defrayed.

The premises at ten of the Branches belonging to the Society were erected

at a cost of upwards of £14,000, including fixtures. Close to the

river, and in a central part of the town, are the Society's manufacturing

departments, newly arranged and rebuilt, comprising tobacco manufacturing;

bread, biscuit, and cake baking; the business of pork butchering, currant

cleaning, coffee roasting, coffee and pepper grinding; and in the same

yard are the stables and slaughter houses; the whole being so arranged

that the produce of each department can be delivered at the shops when

wanted with the precision of a machine.

The business of the Society was £311,754, and the members

numbered 9,722 at the end of 1877; profits, £51,648. The Society

constitutes an important part of the town, which numbers 65,000

inhabitants.

|

|

|

|

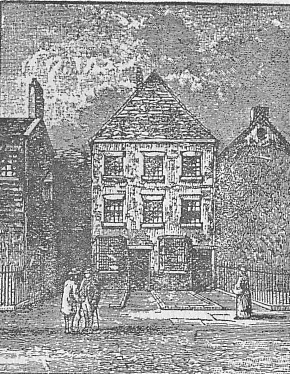

Central

Store, Toad Lane, in 1844 (left) and in 1868. |

It was a festive day when the Central Stores were opened.

I invited Colonel R. J. Hinton, of Washington, to be present, who had

drilled and taken part in training coloured regiments in the Slave War for

freedom, in America. He was witness of the proceedings, and spoke in

the theatre. [64] The Central Store stands at the

junction of St. Mary's Gate and Toad Lane, presenting a copious frontage

to both roads, and raising its head higher than any building in the town.

Standing on the site of the old theatre and the Temperance Hall, all know

the place, and if they did not they can see it. It has been proposed

to erect an observatory upon it, and furnish it with powerful telescopes.

The immense range of view from the top will make it the finest observatory

in Lancashire. Speeches were delivered at the Theatre Royal, the

Mayor, Mr. J. Robinson, presiding. Mr. John Bright, M.P., sent a

cordial letter, being unable to be in Rochdale that day. Earl Russel,

Lord Stanley, Mr. Goldwin Smith, Mr. T. B. Potter, M.P. for the borough,

Mr. Jacob Bright, and others, sent words of acknowledgment or

congratulation. Mr. Thomas Hughes, M.P., Mr. Walter Morrison, M.P.,

Mr. E. V. Neale, Mr. E. O. Greening, the Rev. W. N. Molesworth, the Rev.

J. Freeston, and the present writer, were among the speakers.

Twenty-three years before the co-operators had commenced their humble and

doubtful career in Toad Lane, and that day, September 28th, 1867, they

obtained acknowledged ascendency in the town. They had become the

greatest trading body in it; their Central Store tower, like Saul, head

and shoulders above every other establishment about it.

The Rev. Mr. Molesworth said he regarded that celebration as

of European importance. Throughout the Continent co-operation had

spread rapidly since they had adopted the principles of the Rochdale

Pioneers. All true believers in co-operation turn their eyes to

Rochdale as the Mecca and Medina of the system.

Mr. Morrison, M.P., said that nothing could be done by the

Pioneers in a corner. It was, therefore, important that they should

maintain their reputation. If other societies saw that Rochdale

departed from its first faith, they would plead their eminent example for

departing also.

At this meeting Mr. John Brierley, the Secretary, read an

elaborate report. It ended with this passage:—"In 1855 a

Manufacturing Society was established in this town chiefly by the members

of the Store. Its principle was to apportion the profits made—in

part to capital and in part to labour. This Society made great

success in its earlier years, but the capitalist shareholder began to

think the worker had too much profit, so the bounty to labour was

abolished. (Loud cries of "shame." [65]) But we

hope ere long to see it re-adopted (hear, hear, and cheers), and the

principles of co-operation fully developed, believing that it is fraught

with incalculable blessings to the people."

Mr. Hughes accepted this as a promise that efforts would be

made to restore the character of the Manufacturing Society.

Mr. William Cooper spoke, and in alluding to Mr. Neale

described him as "their own lawyer," for whose services they were all

grateful.

Mr. Councillor Smithies said that the Pioneers, who were

registered under the Friendly Societies Act of 1845, had applied for an

amendment of the law which would enable them to devote a tenth of their

net profits to educational purposes; but, notwithstanding the services of

Mr. Hughes and Mr. Neale, the proposed rule was vetoed by Mr. Tidd Pratt,

the registrar.

The co-operators had never been hosts before on so large a

scale, and had never before been able to invite such distinguished guests

as those to whom they sent invitations. The chief guests had the

choice of two dinners. One was provided for them at the Central

Stores, and another by the Mayor, with whom, as the intention of his

worship was to show courtesy to the Pioneers by making their visitors his

guests, they dined. After the speech, multitudes of people went to

the soiree at the Stores, and the ball at the Public Hall.

-XXIII-

OTHER CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ROCHDALE PIONEERS.

THERE is no doubt that the persistence of leading

Rochdale Co-operators in maturing the "Wholesale" entitles their Store to

be regarded as the practical founder of it. They furnished those who

conceived the idea in its working form, put it in motion, and kept it in

motion.

Long before, Rochdale had the merit to demonstrate the value

of the principle of dividing profits upon purchases instead of upon

shares. Mr. Alexander Campbell, of Glasgow, was an advocate of this

principle. It was first stated by Mr. Campbell in 1822, and

afterwards put by him in the rules of the Cambuslang Society of 1829.

The principle was in the rules of the Melthan Mills Society of 1827, as

Mr. Nuttall has shown: yet it would never have been in Rochdale save for

Mr. Howarth. He re-discovered it, and was certainly the first to

appreciate its importance, and to urge its adoption there. Double

discovery is very common in literature, mechanics, and commerce.

Poets and authors often hit upon ideas which have occurred to others

before they were born, and of whose writings they had no knowledge.

Bell, in Scotland, and Fulton, in America, both discovered the steamship

at the same time. No doubt Mr. Howarth himself originated the very

idea in Rochdale which Mr. Campbell had long before thought of. But

they made nothing of it in Scotland. Indeed, they did not know they

had it among them, until Rochdale successes with it made it of the nature

of a famous discovery. Many discoveries of great pith and moment are

made over and over again, and die over and over again. At last the

old idea, being re-born, falls into the hands of knowing nurses, who bring

the doubtful "bairn" up until it grows strong, tall, and rich. It is

wonderful then what a number of parents the young man finds he had!

This plan of sharing profits with the consumer, without whom no profits

could be made, ensured a following for a store. It gave the customer

an interest in the concern. Other societies soon adopted the same

rule, but none made so much of it as Rochdale has done. The use

other stores of that day put it to would never have given it distinction.

Indeed, the division of profit idea would never have made the noise it

has, but for the Rochdale way of carrying it out. It has been the

ever-growing amounts of profit that attracted the pecuniary eye of the

country to it there. The early co-operators there, having a

world-amending scheme in view, foresaw that money would be required for

that purpose, and this led them to adopt a plan of saving all they gained.

After paying capitalists five per cent. it was open to the co-operators to

sell their goods without further profit, which would have given to each

purchaser his articles at almost cost prices. The consumer would

thus have had, in another form, his full share of advantage by buying at

the Store. The other plan open to them to adopt was to charge the

current prices for all goods sold, and save for the customer the

difference of profit accruing. This plan they adopted; though it was

theoretical and somewhat Utopian, and not likely to be so popular with

members generally, who like cheap articles, who prefer to know what they

save, and to have it at once. Uneducated people do not believe in

saving; they have no confidence in it; they do not believe in an unknown,

untried committee saving money for them; they want it the moment it is

available. With them a penny in hand is worth twenty in the bush.

In one of his lectures on capital and labour, Mr. Holmes, of

Leeds, relates a before-told but still instructive story:—"During one of

the Irish famines, Mr. Forster (the father of the then M.P. for Bradford)

went out there, as the agent of the Society of Friends, to give special

relief, and found the people at one place famished down to chewing

seaweed. He asked them if there was no fish in the sea; they replied

'Yes,' but said 'they could not get them, as they had neither boats nor

nets.' Mr. Forster provided them with boats and nets, upon which

they eagerly inquired, 'Who's to pay us our day's wages?' Mr.

Forster told them 'the fish they got would pay them their wages,' but they

declined to go out on these problematical conditions, and it was not until

Mr. Forster guaranteed them their wages that they set off. The

consequence was that a good trade was carried on, and Mr. Forster soon

found that the boats and nets were cleared—all paid for—and that plenty of

money might be made. He offered the men the boats and nets free of