|

HISTORY OF THE

ROCHDALE EQUITABLE PIONEERS.

__________

PART I.—1844-1857.

-I-

THE FIRST EFFORTS, AND THE KIND OF PEOPLE WHO MADE THEM.

HUMAN nature must be different in Rochdale from what

it is elsewhere. There must have been a special creation of

mechanics in this inexplicable district of Lancashire—in no other way can

you account for the fact that they have mastered the art of acting

together, and holding together, as no other set of workmen in Great

Britain have done. They have acted upon Sir Robert Peel's memorable

advice; they have "taken their own affairs into their own hands;" and what

is more to the purpose, they have kept them in their own hands.

The working class are not considered to be very rich in the

quality of self-trust, or mutual trust. The business habit is not

thought to be their forte. The art of creating a large concern, and

governing all its complications, is not usually supposed to belong to

them. The problem of association has many times been tried among the

people, and as many times it has virtually failed. Mr. Robert Owen

has not accomplished half he intended. The "Christian Socialists,"

inspired by eloquent rectors, and directed by transcendent professors,

aided by the lawyer mind and the merchant mind, and what was of no small

importance, the very purse of Fortunatus himself, [1]

have made but poor work of association. They have hardly drawn a

single tooth from the dragon of competition. So far from having

scotched that ponderous snake, they appear to have added to its vitality,

and to have convinced parliamentary political economists that competitive

strife is the eternal and only self-acting principle of society.

True, reports come to us ever and anon that in America something has been

accomplished in the way of association. Far away in the backwoods a

tribe of bipeds—some mysterious cross between the German and the

Yankee—have been heard of, known to men as Shakers, who are supposed to

have killed the fatted calf of co-operation, and to be rich in corn, and

oil, and wine, and—to their honour be it said—in foundlings and orphans,

whom their sympathy collects, and their benevolence rears. But then

the Shakers have a narrow creed and no wives. They abhor matrimony

and free inquiry. But in the constituency till lately represented by

Mr. Edward Miall, there is liberality of opinion—Susannahs who might

tempt the elders again—and rosy-cheeked children, wild as heather and

plentiful as buttercups. Under all the (agreeable) disadvantages of

matrimony and independent thought, certain working men in Rochdale have

practised the art of self-help, and of keeping the "wolf from the door."

That animal, supposed to have been extirpated in the days of Ethelbert, is

still found shoving himself in our crowded towns, and may be seen any day

prowling on the outskirts of civilisation.

At the close of the year 1843, on one of those damp, dark,

dense, dismal, disagreeable days, which no Frenchman can be got to

admire—such days as occur towards November, when the daylight is all used

up, and the sun has given up all

attempt at shining, either in disgust or despair—a few poor weavers out

of employ, and nearly out of food and quite out of heart with the social

state, met together to discover what they could do to better their

industrial condition. Manufacturers had capital, and shopkeepers the

advantage of stock; how could they succeed without either? Should

they avail themselves of the poor-law? that were dependence; of

emigration? that seemed like transportation for the crime of having been

born poor. What should they do? They would commence the battle

of life on their own account. They would, as far as they were

concerned, supersede tradesmen, millowners, and capitalists: without

experience, or knowledge, or funds, they would turn merchants and

manufacturers. The subscription list was handed round—the Stock

Exchange would not think much of the result. A dozen of these Liliputian capitalists put down a weekly subscription of twopence each—a

sum which these Rochdale Rothschilds did not know how to pay. After

fifty-two "calls" had been made upon these magnificent shareholders, they

would not have enough in their bank to buy a sack of oatmeal with: yet

these poor men now own mills, and warehouses, and keep a grocer's shop,

where they take £76,000 [2] a-year over the counter in

ready money. Their "Cash Sales" of £19,389, recorded in their last

quarterly report which we subjoin, show their ready money receipts to

reach £1,400 a week.

Thus is the origin of the Rochdale Store, which has

transcended all co-operative stores established in Great Britain, is to be

traced to the unsuccessful efforts of certain weavers to improve their

wages. Near the close of the year 1843, the flannel trade—one of

the principal manufactures of Rochdale—was brisk. At this

auspicious juncture the weavers, who were, and are still, a badly paid

class of labourers, took it into their heads to ask for an advance of

wages. If their masters could afford it at all, they could probably

afford it then. Their workpeople thought so, and the employers of

Rochdale, who are certainly among the best of their class, seemed to be of

the same opinion. Nearly each employer to whom the important

question was put, at once expressed his willingness to concede an advance,

provided his neighbouring employers did the same. But how was the

consent of the others to be induced—and the collective agreement of all

to be guaranteed to each? The thing seemed simple in theory, but was

anything but simple in practice. Masters are not always courteous,

and workpeople are not proverbially tacticians. Weavers do not

negotiate with their superiors by letter; a personal interview is commonly

the warlike expedient hit upon—an interview which the servant obtrudes

and the master suffers. An employer has no

à priori fondness for these kind of

deputations, as a demand for an advance of wages he cannot afford may ruin

him as quickly and completely as a fall may distress the workmen.

However, to set the thing going in a practical and a kind way, one or two

firms, with a generosity the men still remember with gratitude, offered an

advance of wages to their own workpeople, upon trial, to see whether

example would induce the employers generally to imitate it. In case

general compliance could not be obtained, this special and experimental

advance was to be taken off again. Hereupon the Trades' Union

Committee, who had asked the advance on behalf of the flannel weavers,

held, in their humble way, a grand consultation of "ways and means."

English mechanics are not conspirators, and the working class have never

been distinguished for their diplomatic successes. The plan of

action adopted by our committee in this case did not involve many

subtleties. After speech-making enough to save the nation, it was

agreed that one employer at a time should be asked for the advance of

wages, and if he did not comply, the weavers in his employ were "to

strike" or "turn out," and the said "strikers" and "turn outs" were to be

supported by a subscription of twopence per week from each weaver who had

the good fortune to remain at work. This plan, if it lacked grace,

had the merit of being a neat and summary way of proceeding; and if it

presented no great attraction to the masters, it certainly presented fewer

to the men. At least Mrs Jones with six children, and Mrs Smith with

ten, could not be much in love with the twopenny prospect held out to

them, especially as they had experienced something of the kind before, and

had never been heard to very much commend it.

The next thing was to carry out the plan. Of course, a

deputation of masters waiting upon their colleagues would be the courteous

and proper thing, but obviously quite out of the question. A

deputation of employers could accomplish more in one day with employers

than a deputation of all the men could accomplish in a month. This,

however, was not to be expected; and a deputation of workmen on this

embassy was an interesting and adventurous affair.

A trades' deputation, in the old time, was a sort of forlorn

hope of industry—worse than the forlorn hope of war; for if the

volunteers of war succeed, they commonly win renown, or save themselves;

but the men who volunteered on trades' deputations were often sacrificed

in the act, or were marked men ever after. In war both armies

respect the "forlorn hope," but in industrial conflicts the pioneer deputy

was exposed to subsequent retaliation on the part of millowners, who did

not admire him; and—let it be said in impartiality, sad as the fact

is—the said deputy was exposed often to the wanton distrust of those who

employed him. A trades' deputation was commonly composed of

intelligent and active workmen; or, as employers naturally thought them,

"dissatisfied, troublesome fellows." While on deputation duty, of

course, they must be absent from work. During this time they must be

supported by their fellow workmen. They were then open to the

reproach of living on the wages of their fellows, of loving deputation

employment better than their own proper work, which indeed was sometimes

the case. Alas! poor trade deputy—he had a hard lot! He had

for a time given up the service of one master for the service of a

thousand. He was now in the employ of his fellows, half of whom

criticised his conduct quite as severely as his employer, and begrudged

him his wages more. And when he returned to his work he often found

there was no work for him. In his absence his overlooker had

contrived (by orders) to supply his place, and betrayed no anxiety to

accommodate him with a new one. He then tried other mills, but he

found no one in want of his services. The poor devil set off to

surrounding districts, but his character had gone before him. He

might get an old fellow-workman (now an overlooker) to set him on, at a

distance from his residence, and he had perhaps to walk five or six miles

home to his supper, and be back at his mill by six o'clock next morning.

At last he removed his family near his new employ. By this time it

had reached his new employer's ears that he had a "leader of the Trades'

Union" in his mill. His employer calculated that the new advance of

wages had cost him altogether a thousand pounds last year. He

considered the weaver, smuggled into his mill, the cause of that.

He walked round and "took stock" of him. The next week the man was

on the move again. After a while he would fall into the state of

being "always out of work." No wonder if the wife, who generally has

the worst of it, with her increasing family and decreasing means, began to

reproach her husband with having ruined himself and beggared his family by

"his trade unioning." As he was daily out looking for work he would

be sometimes "treated" by old comrades, and he naturally fell in with the

only sympathy he got. A "row" perhaps occurred at the public-house,

and somehow or other he would be mixed up with it. In ordinary

circumstances the case would be dismissed—but the bench was mainly

composed of employers. The unlucky prisoner at the bar had been

known to at least one of the magistrates before as a "troublesome" fellow,

under other circumstances. It is not quite clear that he was the

guilty person in this case; but as in the opinion of the master-magistrate

he was quite likely to have been guilty, he gave him the benefit of the

doubt, and the poor fellow stood "remanded" or "committed." The

chief shareholder of the Mildam Chronicle was commonly a millowner.

The reporter had a cue in that direction, and next day a significant

paragraph, with a heading to this effect, "The notorious Tom Spindle in

trouble," carried consternation through the ranks of his old associates.

The next week the editor had a short article upon the "kind of leadership

to which misguided working men submit themselves." The case was dead

against poor Spindle. Tom's character was gone. And if he were

detained long in prison, his family was gone too. Mrs. Spindle had

been turned out of her house, no rent being forthcoming. She would

apply to the parish for support for her children, where she soon found

that the relieving officers had no very exalted opinion of the virtues of

her husband. Tom at length returned, and now he would be looked upon

by all who had the power to help him, as a "worthless character," as well

as a "troublesome fellow." His fate was for the future precarious.

By odd helps and occasional employment when hands were short he eked out

his existence. The present writer has shared the humble hospitality

of many such, and has listened half the night away with them, as they have

recounted the old story. Beaten, consumptive, and poor, they had

lost none of their old courage, though all their strength was over, and a

dull despair of better days drew them nearer and nearer to the grave.

Some of these ruined deputationists have emigrated, and these lines will

recall in distant lands, in the swamps of the Mississippi, in the huts of

a Bendigo digging, and in the "claims" of California, old times and

fruitless struggles, which sent them penniless and heart-broken from the

mills and mines of the old country. In the new land where they now

dwell—a strange dream land to them—their thoughts turn from

pine-forests, night fires, and revolvers, to the old villages, the

smoke-choked towns, and soot-begrimed monotony in which their early life

was spent. Others of the abolished deputationists of whom we speak

turned news vendors or small shopkeepers. Assisted with a few

shillings by their neighbours—in some cases self-helped by their own

previous thrift—they have set up for themselves, have been fortunate,

grown independent, and trace all their good fortune to that day which cost

them their loss of employment.

-II-

APPOINTMENT OF A DEPUTATION TO MASTERS—GREAT DEBATE IN THE

FLANNEL WEAVERS' PARLIAMENT.

SO much will enable the reader to understand the hopes and

fears which agitated the Rochdale Flannel Weavers' Committee, when they

appointed their deputation to wait upon the masters. "Who shall go?"

No sooner was this question put than the loudest orators were hushed.

Cries of "We will never submit"—"We will see whether the masters are to

have it their own way for ever," etc, etc, etc—were at once silenced.

Five minutes ago everybody was forward—nobody was forward now. As

in the old fable, all the mice agreed that the cat ought to be belled, but

who was to bell the cat? The collective wisdom of the

Parliament of mice found that a perplexing question. Has the reader

seen a popular political meeting when some grand question of party power

had to be discussed? How defiant ran the speeches! how militant was

the enthusiasm! Patriotism seemed to be turning up its sleeves, and

the country about to be saved that night. Of a sudden some practical

fellow, who has seen that kind of thing before, suggests that the

deliverance of the country will involve some little affair of

subscriptions—and proposes at once to circulate a list. The sudden

descent of the police, nor a discharge of arms from the Chelsea

Pensioners, would not produce so decorous a silence, nor so miraculous a

satisfaction with things as they are, as this little step. An effect

something like this is produced in a Trades' Committee, when the test

question is put, "Who will go on the deputation?" The men knew that

they should not be directly dismissed from their employ, but

indirectly their fate would probably be sealed. The first

fault—the first accidental neglect of duty—would be the pretex of

dismissal. Like the archbishop in "Gil Blas," who dismissed his

critic—not on account of his candour; his grace esteemed him for

that—but he preferred a young man with a little more judgment. So

the employer has no abstract objection to the workman, seeking to better

his condition—he rather applauds that kind of thing—he merely disputes

the special method taken to accomplish it. The reader, therefore,

understands why our Committee suddenly paused when a mouse was wanted to

bell the cat. Some masters—indeed many masters—are as considerate,

as self-sacrificing, as any workmen are, and they often incur risks and

losses to keep their people in employ, which their people never know, and,

in many cases, would not appreciate if they did. Many Trades'

Unionists are ignorant, inconsiderate, and perversely antagonistic.

It would be equally false to condemn all masters as to praise all men.

But after all allowances are made, the men have the worst of it.

They make things bad for themselves and for their masters by their want of

knowledge. If they do not form some kind of Trades' Union they

cannot save their wages, and if they do form Unions they cannot save

themselves. Industry in England is a chopping machine, and the poor

man is always under the knife.

We will now tell how the Flannel Weavers of Rochdale, whose

historians we are, have contrived to extricate themselves somewhat.

Our Trades' Committee numbered, as all these committees do, a

few plucky fellows, and a deputation was eventually appointed, and set off

on their mission. Many employers made the required advance, but

others, rather than do so, would let their works stop. This

resistance proved fatal to the scheme, seconded as it was by the

impetuosity of the weavers themselves, who did not understand that you

cannot fight capital without capital. The only chance you have is to

use your brains, and unless your brains are good for something, are well

informed and well disciplined, the chance is a very poor one. Our

flannel weavers did not use their brains but their passions. It is

easier to hate than to think, and the men did what they could do

best—they determined to retaliate, and turned out in greater numbers than

their comrades at work were able or willing to support. The cooler

and wiser heads advised more caution. But among the working class a

majority are found who vote moderation to be treachery. The weavers

failed at this time to raise their wages, and their employers succeeded,

not so much because they were right, as because their opponents were

impetuous.

At this period the views of Mr Robert Owen, which had been

often advocated in

Rochdale, were recurred to by the weavers. Socialist advocates,

whatever faults they else might have, had at least done one service to

employers—they had taught workmen to reason upon their condition—they

had shown them that commerce was a system, and that masters were slaves of

it as well as men. The masters' chains were perhaps of silver, while

the workmen's were of copper, but masters could not always do quite as

they would any more than their servants. And if the men became

masters to-morrow, they would be found doing pretty much as masters now

do. Circumstances alter cases, and the Social Reformers sought to

alter the circumstances in order to improve the cases. The merit of

their own scheme of improvement might be questionable, but the Socialism

of this period marked the time when industrial agitation first took to

reasoning. [3] Ebenezer Elliott's epigram, which

he once repeated as an argument to the present writer, pointed to

doctrines that certainly never existed in England:—

|

"What is a Communist? One who hath yearnings

For equal division of unequal earnings;

Idler or bungler, or both, he is willing

To fork out his penny, and pocket your shilling." |

The English working class have no weakness in the way of idleness; they

never become dangerous until they have nothing to do. Their

revolutionary cry is always "more work!" They never ask for

bread half so eagerly as they ask for employment. Communists in

England were never either "idlers or bunglers." When the Bishop of

Exeter troubled Parliament, in 1840, with a motion for the suppression of

Socialism, an inquiry was sent to the police authorities of the principal

towns as to the character of the persons holding those opinions (the same

who built in Manchester the Hall of Science, now the Free Library, at an

expense of £6000 or £7000). The answer was that these persons

consisted of the most skilled, well-conducted, and intelligent of the

working class. Sir Charles Shaw sent to the Manchester Social

Institution for some one to call upon him, that he might make inquiries

relative to special proceedings. Mr. Lloyd Jones went to him, and

Sir Charles Shaw said, that when he took office as the superintendent of

the police of that district, he gave orders that the religious profession

of every individual taken to the station-house should be noted; and he had

had prisoners of all religious denominations, but never one Socialist.

Sir C Shaw said, also, that he was in the habit of purchasing all the

publications of the Society, and he was convinced, that if they had not

influenced the public mind very materially, the outbreaks at the time,

when they wanted to introduce the "general holiday," would have been much

worse than they were, and he was quite willing to state that before the

government, if he should be called upon to give an opinion.

The followers of Mr Owen were never the "idlers," but the

philanthropic. They might be dreamers, but they were not knaves.

They protested against competition as leading to immorality. Their

objections to it were theoretically acquired. They were none of them

afraid of competition, for out of the Socialists of 1840 have proceeded

the most enterprising emigrants, and the most spirited men of business who

have risen from the working classes. The world is dotted with them

at the present hour, and the history of Rochdale Pioneers is another proof

that they were not "bunglers." No popular movement in England ever

produced so many persons able to take care of themselves as the agitation

of Social Reform. Moreover, the pages of the New Moral World

and the Northern Star of this period amply testify that the Social

Reformers were opposed to "strikes," as an untutored and often frantic

method of industrial rectification; as wanting foresight, calculation, and

fitness; often a waste of money. And when a strike led, as they

often have done, to workmen preventing those who were willing to work from

doing so, the strike became indefensible save in view of the fact that

employers did the same by Unionist workmen.

As there was a general feeling that the masters who had

refused their demands had not done them justice, they resolved to attain

it in some other way. They were, as Emerson expresses it, "English

enough never to think of giving up." Hereupon they fell back upon

that talismanic and inevitable twopence, with which Rochdale manifestly

thinks the world can be saved. It was resolved to continue the old

subscription of twopence a week, with a view to commence manufacturing,

and becoming their own employers. As they were few in number, they

found that their banking account of twopences was likely to be a long time

in accumulating, and some of the committee began to despair; and, as

nothing is too small for poverty to covet, some of them proposed to divide

the small sum collected.

At this period a Sunday afternoon discussion used to be held

in the Temperance or Chartist Reading Room. Into this arena some

members of the weavers' committee carried their anxieties and projects,

and the question was formally proposed, "What are the best means of

improving the condition of the people?" It would be too long to

report the anxious and Babel disputation. Each orator, as in more

illustrious assemblies, had his own infallible specific for the

deliverance of mankind. The Teetotalers argued that the right thing

to do was to go in for total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks, and

to apply the wages they earned exclusively to the support of their

families. This was all very well but it implied that everything was

right in the industrial world, and that the mechanic had nothing to do but

to keep sober in order to grow rich; it implied that work was sufficiently

plentiful and sufficiently paid for; and that masters, on the whole, were

sufficiently considerate of the workman's interests. As all these

points were unhappily contradicted by the experience of everyone

concerned, the Teetotal project did not take effect in that form.

Next, the Chartists pleaded that agitation, until they got

the People's Charter, was the only honest thing to attempt, and the only

likely thing to succeed. Universal Suffrage once obtained, people

would be their own law makers, and, therefore, could remove any grievance

at will. This was another desirable project somewhat overrated.

It implies that all other agitations should be suspended while this

proceeds. It implies that public felicity can be voted at

discretion, and assumes that acts of parliament are omnipotent over human

happiness. Social progress, however, is no invention of the House of

Commons, nor would a Chartist parliament be able to abolish all our

grievances at will; but Chartists having to suffer as well as other

classes, ought to be allowed an equal opportunity of trying their hand at

parliamentary salvation. The Universal Suffrage agitation scheme was

looked upon very favourably by the committee, and would probably have been

adopted, had not the Socialists argued that the day of redemption would

prove to be considerably adjourned if they waited till all the people took

the Pledge, and the government went in for the Charter. They,

therefore, suggested that the weavers should co-operate and use such means

as they had at command to improve their condition, without ceasing to be

either Teetotalers or Chartists.

In the end it came about that the Flannel Weavers' Committee

took the advice of the advocates of Co-operation. James Daly,

Charles Howarth, James Smithies, John Hill and John Bent, appear to be the

names of those who in this way assisted the committee. Meetings were

held, and plans for a Co-operative Provision Store were determined upon.

So far from there being any desire to evade responsibility, as working

class commentators in Parliament usually assume, these communistic

teetotal-political co-operators coveted from the first a legal position;

they determined that the society should be enrolled under Acts of

Parliament (10th Geo IV., c. 56, and 4th and 5th William IV., c. 40).

-III-

THE DOFFERS APPEAR AT THE OPENING DAY—MORAL BUYING AS WELL

AS MORAL SELLING.

NEXT, our weavers determined that the Society should transact its business

upon

what they denominated the "ready money principle." It might be suspected

that the

weekly accumulation of twopences would not enable them to give much

credit; but

the determination arose chiefly from moral considerations. It was a part

of their

socialistic education to regard credit as a social evil—as a sign of the

anxiety,

excitement, and fraud of competition. As Social Reformers, they had been

taught to

believe that it would be better for society, that commercial transactions

would be

simpler and honester, if credit were abolished. This was a radical

objection to credit. [4] However advantageous and

indispensable

credit is in general commerce, it would have been a fatal instrument in

their hands.

Some of them would object to take an oath, and the magistrate would object

to

administer it; thus they would be at the mercy of the dishonest who would

come in

and plunder them, as happens daily now where the claim turns upon the

oath.

Besides, some of them had a tenderness with respect to suing, and would

rather

lose money than go to law to get it; they, therefore, prudently fortified

themselves by

setting their faces against all credit, and from this resolution they have

never

departed.

From the Rational Sick and Burial Society's laws, a Manchester communistic

production, they borrowed all the features applicable to their project,

and with

alterations and additions their Society was registered, October 24th,

1844, under the

title of the "Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers." Marvellous as has

been their

subsequent success, their early dream was much more stupendous—in fact,

it

amounted to world making. [5] Our Pioneers set forth their designs in the following

amusing

language, to which designs the Society has mainly adhered, and has

reiterated the

same terms much nearer the day of their accomplishment (in the Society's Almanack

for 1854). These Pioneers, in 1844, declared the views of their

Association thus:—

"The objects and plans of this Society are to form arrangements for the

pecuniary

benefit and the improvement of the social and domestic condition of its

members, by

raising a sufficient amount of capital in shares of one pound each, to

bring into operation the following plans and arrangements:—

"The establishment of a Store for the sale of provisions, clothing, etc.

"The building, purchasing, or erecting a number of houses, in which those

members,

desiring to assist each other in improving their domestic and social

condition, may

reside.

"To commence the manufacture of such articles as the Society may determine

upon,

for the employment of such members as may be without employment, or who

may

be suffering in consequence of repeated reductions in their wages.

"As a further benefit and security to the members of this Society, the

Society shall

purchase or rent an estate or estates of land, which shall be cultivated

by the

members who may be out of employment, or whose labour may be badly

remunerated."

Then follows a project which no nation has ever attempted, and no

enthusiasts yet carried out:—

"That, as soon as practicable, this Society shall proceed to arrange the

powers of

production, distribution, education, and government; or, in other words,

to establish a

self-supporting home-colony of united interests, or assist other societies

in

establishing such colonies."

Here was a grand paper constitution for re-arranging the powers of

production and

distribution, which it has taken fifteen years of dreary and patient

labour to advance

half way.

Then follows a minor but characteristic proposition:—

"That, for the promotion of sobriety, a Temperance Hotel be opened in one

of the

Society's houses as soon as convenient."

If these grand projects were to take effect any sooner than universal

Teetotalism or

universal Chartism, it was quite clear that some activity must take place

in the

collection of the twopences. The difficulty in all working class movements

is the

collection of means. At this time the members of the "Equitable Pioneer

Society"

numbered about forty subscribers, living in various parts of the town, and

many of

them in the suburbs. The collector of the forty subscriptions would

probably have to

travel twenty miles; only a man with the devotion of a missionary could be

expected

to undertake this task. This is always the impediment in the way of

working class

subscriptions. If a man's time were worth anything at all he had better

subscribe the

whole money than collect it. But there was no other way open to them; and,

irksome

as it was, some undertook it, and, to their honour, performed what they

undertook. [6] Three

collectors were

appointed, who visited the members at their residences every Sunday; the

town

being divided into three districts. To accelerate proceedings an

innovation was

made, which must at the time have created considerable excitement. The

ancient

twopence was departed from, and the subscription raised to threepence. The co-operators

were evidently growing ambitious. At length the formidable sum of £28

was accumulated, and, with this capital the new world that was to be, was

commenced.

Fifteen years ago, Toad Lane, Rochdale, was not a very inviting street. Its name did

it no injustice. The ground floor of a warehouse in Toad Lane was the

place selected

in which to commence operations. Lancashire warehouses were not then the

grand

things they have since become, and the ground floor of "Mr Dunlop's

premises," here

employed, was obtained upon a lease of three years at £10 per annum. Mr

William

Cooper was appointed "cashier;" his duties were very light at first. Samuel Ashworth

was dignified with the title of "salesman;" his commodities consisted of

infinitesimal quantities of "flour, butter, sugar, and oatmeal." [7] The entire quantity would hardly stock, a

homeopathic

grocer's shop, for after purchasing and consistently paying for the

necessary fixtures,

£14 or £15 was all they had to invest in stock. And on one desperate

evening—it was

the longest evening of the year—the 21st of December, 1844, the

"Equitable

Pioneers" commenced business; and the few who remember the commencement,

look back upon their present opulence and success with a smile at their

extraordinary opening day. It had got wind among the tradesmen of the town

that

their competitors were in the field, and many a curious eye was that day

turned up

Toad Lane, looking for the appearance of the enemy; but, like other

enemies of more

historic renown, they were rather shy of appearing. A few of the

co-operators had

clandestinely assembled to witness their own denouement; and there they

stood, in

that dismal lower room of the warehouse, like the conspirators under Guy

Fawkes in

the Parliamentary cellars, debating on whom should devolve the temerity of

taking

down the shutters, and displaying their humble preparations. One did not

like to do it,

and another did not like to be seen in the shop when it was done: however,

having

gone so far there was no choice but to go farther, and at length one bold

fellow,

utterly reckless of consequences, rushed at the shutters, and in a few

minutes Toad

Lane was in a titter. Lancashire has its gamins as well as Paris—in

fact, all towns

have their characteristic urchins, who display a precocious sense of the

ridiculous.

The "doffers" are the gamins of Rochdale. The "doffers" are lads from ten

to fifteen, who take off full bobbins from the spindles, and put them on

empty ones. [8] Like

steam to the engine, they are the indispensable accessories to the mills. When they

are absent the men have to play, and often when the men want a holiday,

the

"doffers" get to understand it by some of those signs very well understood

in the

freemasonry of the factory craft, and the young rascals run away in a

body, and, of

course, the men have to play until the rebellious urchins return to their

allegiance. On

the night when our Store was opened, the "doffers" came out strong in Toad

Lane—peeping with ridiculous impertinence round the corners, ventilating their

opinion at

the top of their voices, or standing before the door, inspecting, with

pertinacious

insolence, the scanty arrangement of butter and oatmeal: at length, they

exclaimed

in a chorus, "Aye! the owd weaver's shop is opened at last."

Since that time two generations of "doffers" have bought their butter and

oatmeal at

the "owd weaver's shop," and many a bountiful and wholesome meal, and many

a

warm jacket have they had from that Store, which articles would never have

reached

their stomachs or their shoulders, had it not been for the provident

temerity of the co-operative

weavers.

Very speedily, however, our embryo co-operators discovered that they had

more

serious obstacles to contend with than derision of the "doffers." The

smallness of

their capital compelled them to purchase their commodities in small

quantities, and

at disadvantage both of quality and price. In addition to this, some of

their own

members were in debt to their own shopkeepers, and they neither could, nor

dare,

trade with the Store. And as always happens in these humble movements,

many of

the members did not see the wisdom of promoting their own interests, or

were

diverted from doing it, if it cost them a little trouble, or involved some

temporary

sacrifice. Of course the quality of the goods was sometimes inferior, and

sometimes

the price was a trifle high. These considerations, temporary and trifling

compared

with the object sought, would often deter some from becoming purchasers,

for

whose exclusive benefit the Store was projected. If the husband saw what

his duty

was, he could not always bring his wife to see it; and unless the wife is

thoroughly

sensible, and thoroughly interested in the welfare of such a movement, its

success

must be very limited. If the wife will take a little trouble, and bear

with the temporary

sacrifice of buying now and then an article she does not quite like, and

will send a

little farther for her purchases than perhaps suits her convenience, and

will

sometimes agree to pay a little more for them than the shop next door

would charge,

the co-operative stores might always become successful. Pure quality,

good weight,

honest measure, and fair dealing within the establishment, buying without

haggling,

and selling without fraud, are sources of moral and physical satisfaction

of far more

consequence to a well-trained person than a farthing in the pound cheaper

which the

same goods might elsewhere cost. How heavily are we taxed to put down vice

when

it has grown up—yet how reluctant are we to tax ourselves ever so

lightly to prevent

it arising. If there are to be moral sellers, there must be moral buyers. It is idle to

distinguish the seller as an indirect cheat, so long as the customer is

but an

ambiguous knave. Those dealers who make it a point always to sell cheaper

than

any one else, must make up their minds to the risk of dishonesty, to the

driving of

hard bargains, or of stooping to adulterations [Ed.― see

adulteration, The

Commonwealth, 6 Oct., 1866]. Our little Store thought

more of

improving the moral character of trade than of making large profits. In

this respect

they have educated their associates and customers to a higher point of

character.

The first members of the Store were not all sensible of this, and their

support was

consequently slender, like their knowledge. But a staunch section of them

were true

co-operators, and would come far or near to make their purchases, and,

whether the

price was high or low, the quality good or bad, they bought, because it

was their duty

to buy. The men were determined, and the women no less enthusiastic,

willing, and

content.

Those members of the Store who were true to their own duty, were naturally

impatient that all the other members should do the same; they expected

that every

other member should buy at the Store whatever the Store sold, that the

said member

purchased elsewhere. Not content with wishing this, they sought to compel

all

members to become traders with the Store; and James Daly, the then

secretary,

brought forward a resolution to the effect that those members who did not

trade with

the Store should be paid out. Charles Howarth opposed this motion, on the

ground

that it would destroy the free action of the members. He desired

co-operation to

advance he said he would do all he could to promote it; that freedom was a

principle

which he liked absolutely, and, rather than give it up, he would forego

the

advantages of co-operation. It will be seen, as our little history

progresses, that this

love of principle has never died out, nor, indeed, been impaired amid

these resolute co-operators. James Daly's motion was withdrawn.

-IV-

THE SOCIETY TRIED BY TWO WELL-KNOWN DIFFICULTIES—PREJUDICE AND

SECTARIANISM.

IN March, 1845, it was resolved that a license for

the sale of tea and tobacco be taken out for the next quarter, in the name

of Charles Howarth. This step evidently involved the employment of

more capital; for though the members had increased, funds had not

increased sufficiently for this purpose. The members, in public

meeting assembled, were made aware of this fact; then, for the second time

in the history of the Rochdale Store, do we hear of any member being in

possession of more than twopence. One member "promised to find"

half-a-crown. "Promised to find" is the phrase employed on the

occasion—it was not "promised to pay, or subscribe, or advance."

"Promised to find" probably alluded to the effort required to produce a

larger sum than twopence in those parts. Another member "promised to

find" five shillings, and another "promised to find" a pound. This

last announcement was received with no mean surprise, and the rich and

reckless man who made the promise was regarded with double veneration, as

being at once a millionaire and a martyr. [9]

Other members "promised to find" various sums in proportion to their

means, and in due time the husbands could get from the Store the solace of

tobacco, and wives the solace of tea. At the close of 1845 the store

numbered upwards of eighty members, and possessed a capital of £181 12s.

3d. [10] At first the Store paid 2.5 per cent.

interest on money borrowed, then 4 per cent. After paying this

interest, and the small expenses of management, all profits made were

divided among the purchasers at the Store, in proportion to the amount

expended; and the members soon began to appreciate this very palpable and

desirable addition to their income. Instead of their getting into

debt at the grocer's, the Store was becoming a savings' bank to the

members, and saved money for them without trouble to themselves. The

weekly receipt for goods sold during the quarter ending December, 1845,

averaged upwards of £30.

"The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, held in Toad

Lane, in the Parish of

Rochdale, in the County of Lancaster," made up its mind that a capital of

£1,000 must be raised for the establishment of the Store. This sum

was to be raised by £1 shares, of which each member should be required to

hold four and no more. In case more than £1,000 was required, it was

to be lawful for a member to hold five shares. At the commencement

of the Store, it was allowed a member to have any number of shares under

fifty-one. The chances of any member availing himself of this

opportunity were very dreary. But the officers were ordered, and

empowered, and commanded to buy down all fifty-pound shares with all

convenient speed; and any member holding more than four shares was

compelled to sell the surplus at their original cost of £1, when applied

to by the officers of the Society. But should a member be thrown out

of employment, he was then allowed to sell his shares to the Board of

Directors, or other member, by arrangement, which would enable him to

obtain a higher value. Each member of the Society, on his admission

night, had to appear personally in the meeting-room and state his

willingness to take out four shares of £1 each, and to pay a deposit of

not less than threepence per share, or one shilling, and to pay not less

than threepence per week after, and to allow all interests and profits

that might be due to him to remain in the funds until the amount was equal

to four shares in the capital.

Any member neglecting his payments was to be liable to a

fine, except the neglect arose from distress, sickness, or want of

employment.

When overtaken by distress, a member was allowed to sell all

his shares, save one.

The earliest rules of the Society, printed in 1844, have, of

course, undergone successive amendments; but the germs of all their

existing rules were there. Every member was to be formally proposed,

his name, trade, and residence made known

to everyone concerned, and a general meeting effected his election.

The officers of the Society included a President, Treasurer,

and Secretary, elected half-yearly, with three Trustees and five

Directors. Auditors as usual.

The officers and Directors were to meet, every Thursday

evening, at eight o'clock, in the committee room of the Weavers' Arms,

Yorkshire Street. Then followed all the heavy regulations, common to

enrolled societies, for taking care of money before they had it. The

only hearty thing in the whole rules, and which does not give tic doloreux

in reading it, is an appointment that an annual general meeting shall be

holden on the "first market Tuesday," at which a dinner shall be

provided at one shilling each, to celebrate the anniversary of the grand

opening of the Store. At which occasion, no doubt, though the

present historian has not the report before him, the first sentiment given

was "Th'owd weyvurs' shop," followed by a chorus from the "doffers."

|

|

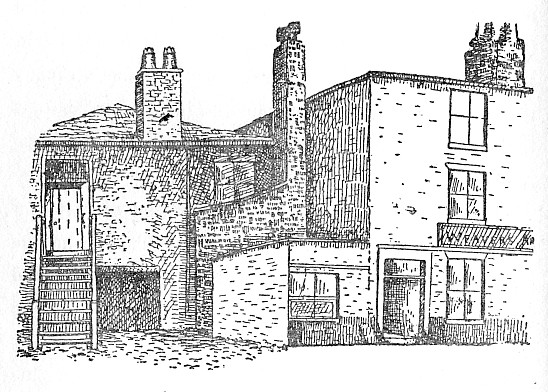

The Socialist Institute.

The Weavers' Arms. |

The gustativeness of the members appears not to have

sustained an annual dinner, for in 1847 [11] we find

records of the annual celebration assuming the form of a "tea party," to

which, in right propagandist spirit, certain Bacup co-operators were

invited.

The store itself was ordered to be opened to the

public (who never came in those days at all) on the evenings of Mondays

and Saturdays only—from seven to nine on Mondays, from six to eleven on

Saturdays. It would appear from this arrangement that the poor

flannel weavers only bought twice a week in those times. A dreadful

string of fines is attached to the laws of 1844. The value of a

Trustee or Director may be estimated by the fact, that his fine for

non-attendance was sixpence. It is plain that the Society expected

to lose only half-a-crown if the whole five ran away. However, they

proved to be worth more than the very humble price they put upon

themselves. Under their management members rapidly increased, and

the Store was opened (March 3, 1845) on additional days, and for a greater

number of hours:—

|

Monday from 4 to 9 p.m.

Wednesday from 7 to 9 p.m.

Thursday from 8 to 10 p.m.

Friday from

7 to 9 p.m.

Saturday from 1 to 11 p.m. |

On February 2nd, 1846, it was resolved that the Store be

opened on Saturday afternoons for the meeting of members; an indication

that the business of the Store was becoming interesting, and required more

attention than the weavers were able

to give it after their long day's labour was over. In the October of

this year, the Store commenced selling butcher's meat. For the three

years 1846-8, the Store was tried by dullness, apathy, and public

distress. It made slow, but it made certain progress under them all.

Very few new members were added during 1846; but the capital of the

Society increased to £252 7s. 1½d., with

weekly receipts for goods averaging £34 for the December quarter.

In case of distress occurring to a member, we have seen that

he was permitted to dispose of his shares, retaining only one.

During 1847 trade was bad, and many of the members withdrew part of their

shares. Nothing can better show the soundness of the advantages

created by the Society than the fact that the first time trade became bad,

and provisions dear, the members rapidly increased. The people felt

the pinch, and it made them look out for the best means of making a little

go far; and finding that the payment of a shilling entrance money, and

threepence a week afterwards—which sum being paid on account of their

shares, was really money saved—would enable them to join the Store; they

saw that doing so was quite within their means, and much to their

advantage. Accordingly, many availed themselves of the opportunity

of buying their goods at the Store. The Store thereby encouraged

habits of providence, and saved the funds of the parish. At the

close of 1847, 110 members were on the books, and the capital had

increased to £286 15s. 3½d., and the

weekly receipts for goods during the December quarter were £36. An

increase of £34 of capital, and £2 a week in receipts during twelve

months, was no great thing to boast of; but this was accomplished during a

year of bad trade and dear food, which might have been expected to ruin

the Society: it was plain that the co-operative waggon was surely, if

slowly, toiling up the hill. The next minute of the Society's

history is unexpected and cheering.

The year 1848 commenced with great "distress" cases and an

accession of new members. Contributions were now no longer collected

from the members at their homes. There was one place now where every

member met, at least once a week, and that was at the Store, and the

cashier made the appointed collection from each when he appeared at the

desk. Neither revolutions abroad, nor excitement nor distress at

home, disturbed the progress of this wise and peaceful experiment.

The members increased to 140, the capital increased to £397, and the

weekly receipts for goods sold in the December quarter rose to £80; being

an increase of £44 a week over the previous year in the amount of sales.

The lower room of the old warehouse was now too small for the

business, so the whole building, consisting of three stories and an attic,

was taken by these enterprising co-operators, on lease for twenty-one

years.

More new members were added to the Society in 1849. The

second-floor became the meeting-room of the members, and also a sort of

news-room, for on August 20th, it was resolved—"That Messrs. James Nuttall,

Henry Green, Abraham Greenwood, George Adcroft, James Hill, and Robert

Taylor, be a committee to open a stall for the sale of books, periodicals,

newspapers, etc.; the profits to be applied to the furnishing the members'

room with newspapers and books." At the close of 1849 the number of

members had reached three hundred and ninety. The capital now

amounted to £1193 19s. 1d., and the weekly receipts for goods had risen to

£179.

In the next year a very old enemy of social peace appeared in

Rochdale. The religious element began to contend for exclusiveness.

The rapid increase of the members had brought together numbers holding

evangelical views, and who had not been reared in a school of practical

toleration. These had no idea of allowing to their colleagues the

freedom their colleagues allowed to them, and they proposed to close the

meeting room on Sundays, and forbid religious controversy. The

liberal and sturdy co-operators, whose good sense and devotion had created

the secular advantages of which the religious accession had chosen to

avail itself, were wholly averse to this restriction. They valued

mental freedom more than any personal gain, and they could not help

regarding with dismay the introduction of this fatal source of discord,

which had broken up so many Friendly Societies, and often frustrated the

fairest prospects of mutual improvement. The matter was brought

before a general meeting, on February 4th, 1850. We give the dates

of the leading incidents we record, for they are historic days in the

career of our Store. On the date here quoted, it was resolved, for

the welfare of the Society:—-"That every member shall have full liberty to

speak his sentiments on all subjects when brought before the

meetings at a proper time, and in a proper manner; and all subjects

shall be legitimate when properly proposed." The tautology of

this memorable resolution shows the emphasis of alarm under which it was

passed, and the endeavour to secure by reiteration of terms a liberty so

essential to conscience and to progress. The founders of the Society

were justly apprehensive that its principles would be overthrown by an

indiscriminate influx of members, who knew nothing of the toleration upon

which all co-operation must be founded, and they moved and carried:—"That

no propositions be taken for new members after next general meeting for

six months ensuing." From this time peace has prevailed on this

subject.

Very early in the history of co-operation—as far back as

1832—the Co-operative Congress, held in London in that year, wisely agreed

to this resolution:—"Whereas, the co-operative world contains persons of

all religious sects, and of all political parties, it is unanimously

resolved, that Co-operators, as such, are not identified with any

religious, irreligious, or political tenets whatever; neither those of Mr.

Owen, nor of any other individual." [12]

Sectarianism is at all times the bane of public unity.

Without toleration of all opinion, popular co-operation is impossible.

These theological storms over, the Society continued its

success. The members increased in 1850 to six hundred; the capital

of the Society, in cash and stock, rose to £2299 10s. 5d., and the cash

received during the December quarter amounted to £4397 17s., or £338 per

week.

In April, 1851, seven years after its commencement, the Store

was open, for the first time, all day. Mr. William Cooper was

appointed superintendent; John Rudman and James Standring shopmen.

This year the members of the Store were six hundred and

thirty; its capital £2785; its weekly sales £308. Somewhat

less than in 1850.

The next year, 1852, the increase of members' capital and

receipts was marked, and they have gone on since increasing at a rate

beyond all expectation. To what extent we shall show in Tables of

Results in another chapter.

-V-

ENEMIES WITHIN AND ENEMIES WITHOUT, AND HOW THEY WERE ALL

CONQUERED.

THE moral miracle performed by our co-operatives of

Rochdale is, that they have had the good sense to differ without

disagreeing; to dissent from each other without separating; to hate at

times, and yet always hold together. In most working classes, and,

indeed, in most public societies of all classes, a number of curious

persons are found, who appear born under a disagreeable star; who breathe

hostility, distrust, and dissension: whose tones are always harsh: it is

no fault of theirs, they never mean it, but they cannot help it; their

organs of speech are cracked, and no melodious sound can come out of them;

their native note is a moral squeak; they are never cordial, and never

satisfied; the restless convolutions of their skin denote "a difference of

opinion;" their very lips hang in the form of a "carp;" the muscles of

their face are "drawn up" in the shape of an amendment, and their wrinkled

brows frown with an "entirely new principle of action;" they are a species

of social porcupines, whose quills eternally stick out; whose vision is

inverted; who see everything upside down; who place every subject in water

to inspect it, where the straightest rod appears hopelessly bent; who know

that every word has two meanings, and who take always the one you do not

intend; who know that no statement can include everything, and who always

fix upon whatever you omit, and ignore whatever you assert; who join a

society ostensibly to co-operate with it, but really to do nothing but

criticise it, without attempting patiently to improve that of which they

complain; who, instead of seeking strength to use it in mutual defence,

look for weakness to expose it to the common enemy; who make every

associate sensible of perpetual dissatisfaction, until membership with

them becomes a penal infliction, and you feel that you are sure of more

peace and more respect among your opponents than among your friends; who

predict to everybody that the thing must fail, until they make it

impossible that it can succeed, and then take credit for their treacherous

foresight, and ask your gratitude and respect for the very help which

hampered you; they are friends who act as the fire brigade of the party;

they always carry a water engine with them, and under the suspicion that

your cause is in a constant conflagration, splash and drench you from

morning till night, until every member is in an everlasting state of drip;

who believe that co-operation is another word for organised irritation,

and who, instead of showing the blind the way, and helping the lame along,

and giving the weak a lift, and imparting courage to the timid, and

confidence to the despairing, spend their time in sticking pins into the

tender, treading on the toes of the gouty, pushing the lame down stairs,

leaving those in the dark behind, telling the fearful that they may well

be afraid, and assuring the despairing that it is "all up." A

sprinkling of these "damned good-natured friends" belong to most

societies; they are few in number, but indestructible; they are the

highwaymen of progress, who alarm every traveller, and make you stand and

deliver your hopes; they are the Iagoes and Turpins of democracy, and only

wise men and strong men can evade them or defy them. The Rochdale

co-operators understand them very well—they met them—bore with

them—worked with them—worked in spite of them—looked upon them as the

accidents of progress, gave them a pleasant word and a merry smile, and

passed on before them; they answered them not by word but by act, as

Diogenes refuted Zeno. When Zeno said there was no motion, Diogenes

answered him by moving. When adverse critics, with Briarian

hands, pointed to failure, the Rochdale co-operators replied by

succeeding.

Whoever joins a popular society ought to be made aware of

this curious species of colleagues whom we have described. You can

get on with them very well if they do not take you by surprise.

Indeed, they are useful in their way; they are the dead weights with which

the social architect tries the strength of his new building. We

mention them because they existed in Rochdale, and that fact serves to

show that our co-operators enjoyed no favour from nature or accident.

They were tried like other men, and had to combat the ordinary human

difficulties. Take two examples.

Of course the members' meetings are little parliaments of

working men—not very little parliaments now, for they include thrice the

number of members composing the House of Commons. All the mutual

criticisms in which Englishmen proverbially indulge, and the grumblings

said to be our national characteristic, and the petty jealousies of

democracies, are reproduced on these occasions, though not upon the fatal

scale so common among the working class. Here, in the parliament of

our Store, the leader of the opposition sometimes shows no mercy to the

leader in power; and Rochdale Gladstones or Disraelies very freely

criticise the quarterly budget of the Sir George Cornewall Lewis of the

day. At one time there was our friend Ben, a member of the Store so

known, who was never satisfied with anything—and yet he never complained

of anything. He looked his disapproval, but never spoke it. He

was suspicious of everybody in a degree, it would seem, too great for

utterance. He went about everywhere, he inspected everything, and

doubted everything. He shook his dissent, not from his tongue, but

his head. It was at one time thought that the management must sink

under his portentous disapprobation. With more wisdom than usually

falls to critics, he refrained from speaking until he knew what he had to

say. After two years of this weighty travail the clouds dispersed,

and Ben found speech and confidence together. He found that his

profits had increased notwithstanding his distrust, and he could no longer

find in his heart to frown upon the Store which was making him rich.

At last he went up to the cashier to draw his profits, and he came down,

like Moses from the mount, with his face shining.

Another guardian of the democratic weal fulminated

heroically. The very opposite of Ben, he almost astounded the Store

by his ceaseless and stentorian speeches. The Times newspaper

would not contain a report of his quarterly orations. He could not

prove that anything was wrong, but he could not believe that all was

right. He was invited to attend a meeting of the Board; indeed, if

we have studied the chronicles of the Store correctly, he was appointed a

member of the Board, that he might not only see the right thing done, but

do it; but he was too indignant to do his duty, and he was so committed to

dissatisfaction that above all things he was afraid of being undeceived;

and, during his whole period of office, he actually sat with his back to

the Board, and in that somewhat unfriendly and inconvenient attitude he

delivered his respective opinions. Whether, like the hare, he had

ears behind has not been certified; but, unless he had eyes behind, he

never could have seen what took place. A more perfect member of an

opposition has rarely appeared. He was made by nature to conduct an

antagonism. At length he was bribed into content—bribed by the only

legitimate bribery—the bribery of success. When the dividends came

in behind him, he turned round to look at them, and he pocketed his

"brass" and his wrath together; and, though he has never been brought to

confess that things are going right, he has long ceased to say that they

are going wrong.

The Store very early began to exercise educational functions.

Besides supplying the members with provisions, the Store became a meeting

place, where almost every member met each other every evening after

working hours. Here there was harmony because there was equality.

Every member was equal in right, and was allowed to express his opinions

on whatever topic he took an interest in. Religion and politics, the

terrors of Mechanics' Institutions, were here common subjects of

discussion, and harmless because they were open. In other respects the

co-operators acquired business confidence as well as business habits. The

Board was open to everybody, and, in fact, everybody went everywhere.

Distrust dies out where nothing is concealed. Confidence and honest pride

sprung up, for every member was a master—he was at once purchaser and

proprietor. But all did not go smoothly on. Besides the natural obstacles

which exist, ignorance and inexperience created others.

Poverty is a greater impediment to social success than even

prejudice. With a small capital you cannot buy good articles nor

cheap ones. What is bought at a small Store will probably be worse

and dearer than the same articles elsewhere. This discourages the

poor. With them every penny must tell, and every penny extra they

pay for goods seems to them a tax, and they will not often incur it.

It is of no use that you show them that it and more will come back again

as profit at the end of the quarter. They do not believe in the

end of the quarter—they distrust the promise of profits. The

loss of the penny to-day is near—the gain of sixpence three months hence

is remote. Thus you have to educate the very poor before you can

serve them. The humbler your means the greater your

difficulties—you have to teach as well as to save the very poor.

One would think that a customer ought to be content when he is his own

shopkeeper; on the contrary, he is not satisfied with the price he charges

himself. Intelligent contentment is the slowest plant that grows

upon the soil of ignorance.

Some of the male members, and no wonder that many of the

women also, thought meanly of the Store. They had been accustomed to

fine shops, and the Toad Lane warehouse was repulsive to them; but after a

time the women became conscious of the pride of paying ready money for

their goods, and of feeling that the Store was their own, and they began

to take equal interest with their husbands. As usually happens in

these cases, the members who rendered no support to the new undertaking

when it most wanted support, made up by making more complaints than

anybody else, thus rendering no help themselves and discouraging those who

did. It has been a triumph of penetration and good sense to inspire

these contributors with a habit of supporting that, which, in its turn,

supports them so well. There are times still when a cheaper article

has its attraction for the Store purchaser, when he forgets the supreme

advantage of knowing that his food is good, or his garment as stout as it

can be made. He will sometimes forget the moral satisfaction derived

from knowing that the article he can buy from the Store has, as far as the

Store can influence it, been produced by some workman, who, in his turn,

was paid at some living rate for his labour. Now and then, the

higgler will appear at the little co-operative stores around, and the

Store dealers will believe them, and prefer their goods to the supplies to

be had from the Store, because they are some fraction cheaper; without

their being able to know what adulteration, or hard bargaining elsewhere,

has been practised to effect the reduction.

Any person passing through the manufacturing districts of

Lancashire will be struck with the great number of small provision shops;

many of them dealing in drapery goods as well as food. From these

shops the operatives, to a great extent, spread their tables and cover

their backs. Unfortunately, with them the credit system is the rule,

and ready money the exception. The majority of the people trading at

these shops have what is called a "Strap Book," which, of course, is

always taken when anything is fetched, and balanced as often as the

operatives receive their wages, which is generally weekly, but in many

cases fortnightly. A balance is generally left due to the

shopkeeper, thus a great number of operatives are always less or more in

debt. When trade becomes slack he goes deeper and deeper, until he

is irretrievably involved. When his work fails altogether, he is

obliged to remove to another district, and of course to trade with another

Shop, unless at great inconvenience he sends all the distance to the old

shop.

It sometimes happens that an honest weaver will prefer all

this trouble to forsaking a house that has trusted him. One instance

has been mentioned to the present writer, in which a family that had

removed from a village on one side of the town to one on the opposite

side, continued for years to send a distance of two miles and a half to

the old shop for their provisions, although in doing so they had to pass

through the town of Rochdale, where they could have obtained the same

things cheaper. This is in every way a grateful and honourable fact,

and the history of the working class includes crowds of them.

We are bound to relate that the capital of the Store would

have increased somewhat more rapidly, had not many of its members at that

time been absorbed by the land company of Feargus O'Connor. Many

members of the Store were also shareholders in that concern, and as that

company was considered by them to be more feasible, and calculated sooner

to place its members in a state of permanent independence, much of the

zeal and enthusiasm necessary to the success of a new society were lost to

the co-operative cause.

The practice of keeping up a national debt in this country,

on the interest of which so many are enabled to live at the expense of

industrious taxpayers, and the often immoral speculations of the Stock

Exchange, have produced an absurd and injurious reaction on the part of

many honest people. Many co-operative experiments have failed through want

of capital, because the members thought, it immoral to take interest, and

yet they had not sufficient zeal to lend their money without interest. Others have had a moral objection to paying interest, and as money was not

to be had without, of course these virtuous people did nothing—they were

too moral to be useful. All this showed frightful ignorance of political

economy. If nobody practised thrift and self-denial in order to create

capital, society must remain in perpetual barbarism; and if capital is

refused interest as compensation for its risk, it would never be available

for the use of others; it would be simply hoarded in uselessness, instead

of being the great instrument of civilisation and national power. The

class of reformers who made these mistakes were first reclaimed to

intelligent appreciation of industrial science by Mr. Stuart Mill's

"Principles of Political Economy, with some of their applications to

Social Philosophy." Most of these "applications" were new to them, and

though made with the just austerity of science, they manifested so deep a

consideration for the progress of the people, and a human element so fresh

and sincere, that prejudice was first dispelled by sympathy, and error

afterwards by argument.

The principle of co-operation—so moralising to the

individual as a discipline, and so

advantageous to the State in its results—with what difficulty has it

made its way in

the world! Regarded by the statesman as some terrible form of political

combination,

and by the rich as a scheme of spoliation; denounced in Parliament,

written against

by political economists, preached against by the clergy; the co-operative

idea, as

opposed to the competitive, has had to struggle, and has yet to struggle

its way into

industry and commerce. Statesmen might spare themselves the gratuitous

anxiety

they have often manifested for the suppression of new opinion. Experience

ought to

have shown them that wherever one man endeavours to set up a new idea, ten

men

at once rise up to put it down; not always because they think it bad, but

because,

whether good or bad, they do not want the existing order of things

altered. They will

hate truth itself, even if they know it to be truth, if truth gives them

trouble. The

statesman ought to have higher taste, even if he has not higher

employment, than to

join the vulgar and officious crowd in hampering or hunting honest

innovation. There

is, of course, a prejudice felt at first on the part of shopkeepers

against co-operative

societies. That sort of feeling exists which we find among mechanics

against the

introduction of machinery, which, for want of better arrangements, is sure

to injure

them first, however it may benefit the general public afterwards. But,

owing to the

good sense of the co-operators, and not less to the good sense of the

shopkeepers

of Rochdale, no unfriendliness worth mentioning has ever existed between

them.

The co-operators were humbly bent on improving their own condition, and at

first

their success in that way was so trivial as not to be worth the trouble of

jealousy. For

the first three or four years after the commencement of the Store, its

operations

produced no appreciable effect upon the retail trade of the town. The

receipts of the

Store in 1847, four years after its commencement, were only £36 a week;

about the

receipt of a single average shop, and five or ten times less than the

receipts of some

shops. But of late years, no doubt, the shopkeepers, especially smaller

ones, have

felt its effects. In some instances shops have been closed in consequence. The

members of the Store extend out into the suburbs, a distance of one or two

miles

from the town. It has happened in the case of at least one suburban

shopkeeper,

that half the people for a mile round him had become Store purchasers. This, of

course, would affect his business. The good feeling prevailing among the

tradesmen

of the town has been owing somewhat to a display of unexpected good sense

and

moderation on the part of the co-operators, who have kept themselves free

from the

greed of mere trade and the vices of rivalry. If the prices of grocery in

the town rose,

the Store raised its charges to the same level. It never would, even in

appearance,

nor even in self-defence, use its machinery to undersell others; and when

tradesmen

lowered, as instances often occurred, their prices in order to undersell

the Store, and

show to the town that they could sell cheaper than any society of weavers:

and when

they made a boast of doing so, and invited the customers of the Store to

deal with

them in preference, or taunted the dealers at the Store with the higher

prices they

had to pay, the Store never at any time, neither in its days of weakness

nor of

strength, would reduce any of its prices. It passed by, would not

recognise, would in

no way imitate this ruinous and vexatious, but common resource of

competition. The

Store conducted an honest trade—it charged an honest average price—it

sought no

rivalry, nor would it be drawn into any, although the means of winning

were quite as

much in its hands as in the hands of its opponents. The prudent maxims of

the

members were, "To be safe we must sell at a profit." "To be honest we must

sell at a

profit." "If we sell sugar without profit, we must take advantage covertly

in the sale of

some other articles to cover that loss." "We will not act covertly; we

will not trade

without profit whatever others may do; we will not profess to sell cheaper

than

others; we profess to sell honestly"—and this policy has conquered.

Some manufacturers were as much opposed to the co-operators' Store as the

shopkeepers—not knowing exactly what to make of it. Some were influenced

by

reports made to them by prejudiced persons—some had vague notions of

their men

acquiring a troublesome independence. But this apprehension was of short

duration,

and was set at rest by the good sense of others. One employer was advised

to

discharge some of his men for dealing at the Store, who serviceably

answered, "He

did not see why he should. So long as his men did their duty, it was no