|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER LVIII.

UNSUSPECTED SPIES.

(1855.)

SPIES are of two classes—those in the pay of despotism, and those who

watch and report upon the proceedings of the enemies of the people. The

vocation of the spy is at best a repulsive pursuit. Deceit, false

pretences, and treachery constitute the capital of the business, and its

success is the success of a traitor. In war it has its only justification. Where murder is the object of both sides, treachery does not count; it

may abridge, or prevent, worse disasters. But in peace it is doing evil

that good may come, and introduces baseness into policy. In avowed war the

spy of a forlorn hope of a patriotic cause is a pathetic figure. He lives

under a double suspicion, and his life is in peril at the hands of foe and

friend. He is killed if discovered by the enemy, and he often shares the

same fate from his friends, who suspect him from observing his intercourse

with the foe. Bound by his mission of secrecy and peril, he is unable to

explain himself to any who may be ignorant by whose instruction he acts. And when he succeeds in what he has undertaken, he may find that those to

whom he looked for defence and honour may have themselves perished in the

same conflict before his dangerous undertaking is over.

The spies of which I write are the venal and baser sort. Some of them do

not restrict themselves to discovering plots, but devise them and seduce

men to engage in them, in order to betray them.

One of these was Edwards, the spy of Fleet Street, who was employed to

prevent the publication of Thomas Paine's works, by finding out the

persons engaged in their secret issue, or, failing that, to implicate

Richard Carlile in some plot by which he might be got rid of. Edwards,

under which name this spy went, was a clever man, who took a room opposite Carlile's shop, professing to be a sculptor, an art for which he had

talent. Avowing great sympathy with Carlile's intrepid efforts for freeing

the press, and not less admiration for the author of "The Rights of Man,"

he made a statue of Paine in proof of his sincerity, and presented it to Carlile, who made it one of the ornaments of his shop. The statue is now

an ornament in one of the ancient halls of Northumberland. Edwards did not

succeed with Carlile, who had such plentiful experience with Government

prosecutions as to have vigilant suspicion of all overtures from

strangers.

There were several spies in the pay of the Government in the Chartist

agitation of 1839. They attended at the meetings of the Chartist Union,

whose leaders were against physical force and sought the extension of the

suffrage by moral means. These spies sent to congenial papers reports of

venomous speeches which were never made, leading the public to regard the

speakers as wild and dangerous insurgents. The Morning Chronicle was one

of the papers open to these reporters. One morning a leader appeared

saying—"If the ruffianly language held at the Snow Hill meeting on

Friday night—language so foul, so flagitious [which was never uttered],

that we reluctantly sullied our columns with expressions which reflect

scandal upon an assembly of Englishmen, and are calculated to bring the

privilege of free discussion itself into odium and disgrace—if such 'open

and advised speaking' is to pass with impunity, then truly the law is a

dead letter, and the Government deserves all the contempt with which it is

assailed,"

The Morning Chronicle described two meetings held at Farringdon Hall,

Snow Hill, as "Chartist and Irish Confederate gatherings." They had been

neither. They were called by the Co-operative League, a body bent more on

social reform than political agitation. The meeting, on Friday night,

stated to have been held at the "King's Arms" Tavern, Snow Hill, was held

in Farringdon Hall, a building quite distinct from the tavern. It was

stated that several of the Foot Guards were there. Only one was present,

and he in undress uniform. Mr. Ewen was announced as chairman.

The chairman was Mr. Youll. Mr. Walter, reported to have seconded

the resolution, was Mr. Cooper; and an indecent expression attributed to

Mr. Shorter was never uttered by him. It was stated, also, that the

Co-operative League was under the auspices of Douglas Jerrold and William Howitt, who were never seen or heard of in connection with the body. These

facts were made known at the time, but with little effect.

About that period there was a small black man bearing the absurd name of

Cuffy—a name, however derived or acquired, he foolishly retained, though

continually ridiculed by adversaries because of the appellation. He was

about the stature of George Odgers, who, many will remember, was once

nearly elected member for Southwark. Cuffy was a victim of spy

machinations, and was transported. His name contributed to convict him,

yet he was an honest, well-conducted man, and much sympathy was felt for

him. Mr. Cobden showed him respect by employing Mrs. Cuffy in some

domestic office in his household.

The favourite and most successful device of the spies was to advise

"speaking out." Their cry was, "The time has come to let the Government

know what men think!" Measured and reasonable speech, calculated to

impress power without irritating it, was described "as mealy-mouthedness,"

and men were sent to meetings to applaud, on a secret signal, any outrage

of speech by which both speaker and meeting were made to compromise the

cause advocated, and justify the repression by force and prosecution,

which "friends of order" were always ready to counsel. Their policy was

to alarm the timid, who knew nothing of the facts, by a terror which did

not exist, and who therefore gave their vote for "strong measures" for

exterminating a small struggling party with right and misfortune on their

side. Then there would appear among the Radicals a plausible person

affecting to burn with patriotic indignation, and professing to have

military and chemical knowledge which he would place at their service. By

judiciously giving a subscription to their fund, which he represented as

coming from persons who did not wish to be known, he acquired confidence,

and created the impression that there were powerful persons in the

background willing to aid, provided a blow was struck which would "prove

to the Government that the people were in earnest." One of these knaves

produced an explosive liquid, which he said could be poured into the

sewers, and, being ignited, would blow up London from below. This satanic

preparation was tried in a cellar in Judd Street, while I was taking tea

in the back parlour above. I did not know at the time of the operation

going on below, or it might have interfered with my satisfaction in the

repast on which I was engaged.

Another person induced to join in this subterranean plot was a young

enthusiast, who had impetuosity without experience, and who was afterwards

the subject of many friendly attentions from a Conservative peer. The

enthusiast is still living, and there is no reason to suppose that he was

not an honest man. He was the type of the men, ardent without foresight,

who come into this lumbering, slow-moving world, and are indignant that it

does not mend its ways all at once. Their honourable but uninstructed

ardour is the material upon which a treacherous spy selects to work. The

two spies I next describe were of a superior class. I had personal

communication with them extending over several years.

One went under the name of André, a suspicious name, for Washington

hanged one of the family. This André was as fat as a Frenchman could be. He was handsome, literally smooth-faced, and mellow; he was quite

globular, and when he moved he vibrated like a locomotive jelly. His

speech was as soft as his skin. He had an unaffected suavity of manner,

and an accent of honesty and enthusiasm which entirely beguiled you, save

for a certain vagueness of statement which warned you to wait for its

interpretation in action before you entirely trusted it. He had large

commercial views with an indefinite outline, a faculty for finance

proposals difficult to fathom, and an instinct for the friendship of men

who, possessing money, had philanthropic aspirations without business

experience. He first appeared as the friend and counsellor of a group of

generous minded disciples of Professor Maurice, who became known as

Christian Socialists. When they became interested in the organization and

the extension of co-operation, his subtle penetration enabled him to see

that a business agency might be founded in London for the supply of

stores. There was then no Wholesale Buying Society such as that afterwards

founded in the North, and which has attained great magnitude. Premises

were taken in Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, which became costly by the

alterations made for the transaction of wholesale business before there

existed stores sufficiently numerous to support the agency created for

serving them. The antecedents of André, so far as they were known, were

calculated to inspire confidence in him. When a young man, he was one of

the enthusiastic followers of St. Simon, in Paris, distinguished for

intrepidity and devotion in their cause, and he had created a strong

impression by his eloquence and propagandist fervour. It was difficult to

conceive that a rotund gentleman of luxurious habits could ever have been

an ardent apostle; but, with all his soft obesity, he had the energy of

Count Fosco, whom Wilkie Collins has depicted in his "Woman in White,"

and, like that energetic hero, was not unacquainted with secret

conspiracies. When Enfantin and other leading St. Simonians sought

effacement, he sought employment—without delicacy or scruple as to the

nature of it. He came to England on a political mission devised by the

conspirators of the Empire. He was, I believe, an agent in the

purchase of the Morning Chronicle in the interest of the French usurper, but this

was unknown to the gentlemen of the party with whom he connected himself. His business here was that of a spy of the Empire.

The better to effect this object, and to justify his

secret employment, it was necessary that he could prove his acquaintance

with insurgent parties in England, and his connection with so respectable

a body of social agitators as the disciples of Mr. Maurice not only ensured him from

suspicion, but afforded him the means of influencing popular opinion in

favour of his political paymaster. He became acquainted with famous

Chartist leaders, and, as I was personally acquainted with the friends of

Mazzini and Garibaldi, he showed me many acts of courtesy.

At that time Christian Socialists were generously promoting the interests

of working men and desirous of establishing co-operative workshops.

As many of these existed in France, and many were subsequently subsidised

by the Emperor with a view to making the Empire popular with working men,

André, who had been among them, had precisely that kind of knowledge

useful to gentlemen who honestly thought that working men would become

more interested in Christianity if they were better cared for, and a

considerable fortune was expended by one of the most generous of the

party, Mr. E. V. Neale, in establishing co-operative workshops. They did

not sufficiently appreciate that the elevation of the working men can only

be affected by education within, rather than from without, and that their

training is most sure when they employ and risk their own capital. Working

men may be aided in their efforts, but they quickliest acquire prudence

when they peril their own money as well as that of others.

André inspired me with a feeling of friendliness towards him which has

never left me. He was the greatest artist in espionage of any spy I have

known. He never asked me for any information which would have awakened

suspicion in me, but he gave me opportunities of mentioning things. As,

however, my habit was to consider as their own the affairs of others in

which I was in any way concerned, I never added to André's political

knowledge, but I have no doubt he knew how to turn his acquaintance with

me to his private professional advantage, and in ways of which I was

unconscious.

As I had never seen Oxford, and had a great desire to learn something of

its interior life, André had penetration enough to see that a visit there

would be agreeable to me. He had a personal interest in influencing the

Dean of Oriel as a subscriber to the capital of a new business project of

his own, which he called by the well-chosen title of the "Universal

Purveyor." The Dean, like many other excellent Christians, believed that

the neglect of the social condition of the people was the cause of popular

alienation from Christianity. It never occurred to them that its evidences

were defective, and that the alienation the Christian deplored arose in

most minds from difficulties it presented to the understanding. The

interest I took in any proposal of theirs tending to infuse morality into

trade, giving the workmen participation in the profit of his industry,

appeared to them to proceed from growing reconcilement to church tenets,

especially as I openly honoured and worked willingly with any Christian

person who would render help in this direction. André knew how to colour

that action with theological hope. Accordingly, he took me down to

Oxford, where I became for awhile the guest of the Rev. Charles Marriott, then

Dean of Oriel. I then saw Oxford for the first time, and the happy days I

stayed there will always dwell in my memory. The rooms occupied by

Mr. Ward, who afterwards became a convert to Rome, were entered through

the Dean's chambers, and when we were dining Mr. Ward would sometimes have

occasion to pass through. Only once, when he was entering, did I

catch a glimpse of his florid face and well-fed figure, so different from

Mr. Marriott, who was pallid, thin, and gentle in speech and manners.

As Mr. Ward passed through, he carried his hat on the side of his face—a

delicate consideration, so that Mr. Marriott's guests might not be under

conscious observation. I thought it betokened a gentlemanly instinct, but

it also prevented us from observing him.

One day Mr. Marriott conducted me round several of the colleges, showing

me things he thought might interest me, and we discoursed on the way on

matters of opinion. I told him that I did not share the confidence he had

in the premises of his faith, though desiring as much as himself to know

the will of Deity, and to do it when I did know it. I was restrained by

the difficulty I had of knowing what the Infinite Will might be, except

through the works of nature and the necessity of justice, truth and

kindness in society. I remember he paused in his walk, and, turning to me,

said: "Mr. Holyoake, I would rather reason with a thinking atheist than

with a Dissenting minister. I find the minister has always a little

infallibility of his own which you can never reach; while the atheist,

who proceeds upon reason, is open to reason, and there is a common ground

upon which evidence can operate."

By this time much of the wealth of the Christian Socialists had been

dissipated. André appeared alone as the projector of the Universal

Purveyor. His prospectuses were models of plausibility and just

sentiments, of which the only thing certain was the expensiveness of

putting them into practice. As I approved of his professed object, he had

a right to count on my aid; but he sought it in a form for which I was

unprepared. It was that I should put my name to a bill for him to

negotiate in the City to meet some immediate requirement of his business. I explained to him the rule on which I acted in such cases, which was

never to put my name to a bill unless I was able to pay it if the drawer

did not, and was willing to pay it if he could not.

Some time afterwards he returned to Paris, and when, subsequently I

inquired for him there, on grounds of friendship, I heard he was in a

Government office under the Empire. When the Empire happily fell, it

transpired that he was in the pay of the Emperor as Director of the Secret

Bureau of Espionage, where his personal knowledge of the English parties

and press rendered him a competent and useful agent. He had been a spy all

the while he was in England. The last I heard of him was a report of his

death, which was probable, as he was too fat to live long; but the report

may have been but a form of effacing himself peculiar, to the St. Simonian

order to which he formerly belonged. It is a resort of many, no longer

solicitous of personal recognition, to put in circulation a rumour of

their decease.

A man of a different stamp, inasmuch as he had scruples

of honour, was a certain Major W----, in whom I had more trust, because he

had more ingenuousness of manner, and by reason of the company in which I

found him. He professed to me to be an agent of Mazzini, to whom I

believe he was really attached. He never awakened more than a

transient suspicion in that penetrating Italian leader. The major

often came to me to give me information, intending to enlist my confidence

in his zeal. Now and then he would make me a present of a new patent

pen, or some other little novelty which he thought might interest me.

He was a well-built, good-looking man of about forty, possessing

considerable strength. He lived at Fulham, in comfortable lodgings,

and always appeared to have means. This observation led me to

inquire, from his friends, whence they were derived, as at the Café d'Etoile, Windmill Street, I often found the

major playing billiards with other foreigners, manifestly having time on

his hands and money to spend. Occasionally he disappeared, at the time of

the rising of the Italian patriots or some affair of Garibaldi's, when he

would send me a small paragraph for insertion in the papers. Sometimes

there would appear from other hands a paragraph in the incidental way of

news, stating that Major W---- had been wounded, which probably never

occurred. When the Empire fell, and the list of Napoleon's agents found at

the Tuileries was published, we were all very much surprised to find, in

addition to the name of André, that of the major. There was no doubt that

he communicated to the enemy information of the forces and resources of

the insurgents. But there was reason to believe that he made, as many

other Italian spies were known to do, a resolution never to betray

Mazzini, nor compromise any movement under his instructions.

A sensuous obesity had much to do with André's success. Fatness is a

force in politics, though its influence is overlooked. Cassius would never

have been suspected by Cæsar had he not been lean. Blatant bulk without

sense goes further with a popular audience than bones with intelligence. The Tichborne Claimant would never have had so many followers had he been

thin. A fat person is always graceful; his motions are without angularity,

even the inclination of the head is self-limited; the nerves themselves

are so embedded that they betray no emotion on the surface. This was shown

in the Claimant, who, when his friends and the noble lord who was his

supporter returned to his chambers in Jermyn Street, all depressed and

unmanned by the adverse turn affairs were taking, the Claimant was

entirely unperturbed, maintaining an easy air, which shamed and reassured

his dismayed friends. A peer could not have manifested more dignity, or a

philosopher more calmness. It was all owing to the physical impossibility

of his manifesting solicitude.

CHAPTER LIX.

UNPUBLISHED LETTERS OF WALTER SAVAGE PAGE LANDOR.

(1856-7.)

WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR, whose age at his death exceeded ninety, enjoyed for

seventy years reputation as a poet. As is the case of few poets, he

excelled in prose as well as verse. In all his life there was hardly any

tyranny against which his brave spirit did not utter an indignant protest. In early manhood, after he had dealt with his patrimony in land with more

than princely splendour, he led a troop to join the Spanish patriots who

rose against Napoleon I. On every act of national heroism he lavished

splendid praise. Late in life an action was brought against him by a lady

in Bath, who had provoked him by acts which he regarded as implying

meanness and ingratitude. Against her he wrote verses with a satiric

vigour which belonged to him alone, which even Swift did not equal. Judgment was given against Landor, when he asked me to print for him a

justification of himself, and desired me to transmit copies to certain

persons whose names and addresses he gave me. Though he knew his

publication would involve him in serious consequences if traced to him, he

made no stipulation that I should keep the commission secret. Nor did I

(though, as printer, I was liable in law in like manner) make any

stipulation for indemnity. In applying to me, I supposed he had reason to

believe that he could trust me in a matter where confidence might be of

importance to him. I had Landor's manuscript copied in my own house, so

that no printer should by chance see the original manuscript in the

office. My brother Austin, whom in all these things I could trust as I

could trust myself, set up and printed with his own hands Landor's

defence, so that none save he and I ever saw the pamphlet, until the post

delivered copies at their destination. A reward of £200 was offered for

the discovery of the printer, without result. Twelve years later, Landor

being then dead, I told Lord Houghton I was the printer of his "defence,"

but until this day I have mentioned it to no one else.

In his first letter to me, Landor contemplated my publishing the copies,

but this idea was soon abandoned, as appears in his letters. The action

against him, which had then recently been decided, had cost him more than

£1,500, and another action might arise had I placed the "Defence" on

sale.

The eight-paged octavo pamphlet bore the title—

|

MR. LANDOR'S REMARKS

on a

SUIT PREFERRED AGAINST HIM

at the

SUMMER ASSIZES IN TAUNTON, 1858,

Illustrating the

APPENDIX TO HIS HELLENICS. |

Landor's first

letter to me was the following:—

"FLORENCE, March, 22, 1859.

"SIR,—I know not whether you will think it worth your while to publish

the papers I enclose. Curiosity, I am assured, will induce many to

purchase it, my name being not quite unknown to the public. For my own

part, I can only offer you five pounds for 100 copies—the rest will

remain yours. The esteem in which I have ever held you induces me to make

this proposal.—I am, sir, very obediently yours,

"W. S. LANDOR.

“No action was brought against the tradesmen for their

reports, which I twice published in Bath, and the publications were bought

up by Mr. H. Yescombe; nor dared he produce them in his action against me. The action

was for verses which the judge would not permit to be recited in court,

where two falsifications might be pointed out, one of which (as a juryman

is reported to have said), would have altered the case, and, of course,

the verdict.

W.S.L."

Landor did not take into account that further indictable matter after the

conviction would be regarded by the Court very seriously. The "falsification" he refers to in the preceding letter is a curious instance of the value of a comma. The appellation

which the lady who brought the action against him took to herself was Caina, which is in Dante a region of hell. The judge did not remember the

meaning of the name, and appears to have assumed that Landor applied it to

her. Landor, using Milton's allegory of "Sin and Death," whose offspring

would not be fair to look upon, alluded to a young lady whom he considered

had been ill-treated by Caina, and wrote:—

|

"Thou hast made her pale and thin

As the child of Death by Sin." |

"That is, begotten by Death on Sin. But the plaintiff's lawyer," Landor

said, "inserted a comma which was not to be found in his lines." The

lawyer, by placing a comma after Death, would make it appear that Caina

was guilty of some horrid sin. The jury found out too late what had

been done. After he had received a proof of his "Defence," to use

his own term, he wrote:—

"Your letter has highly gratified me. Would you kindly take the trouble to

send copies to the following?—

|

To Phinn, M.P. ........................................................................

|

3 |

|

Monckton Milnes, M.P............................................................ |

3 |

|

The Judge whosoever he was (It was Baron Channell)... |

3 |

|

Lord

Brougham

........................................................................ |

3 |

|

Mr. Hall, Highgate................................................................... |

3 |

And the principal periodicals, newspapers, &c., Leigh Hunt, Linton, and

whoso else you please. The rest to me at Florence."

In another letter he further directed me to send copies to other persons,

and named the papers he wished to receive them—Times, Daily News,

Literary Gazette, Examiner, Edinburgh Review,

Quarterly Review. John Forster, Montague Square, 3 copies; Kossuth, Admiral Gawen, Sir W. Napier, Scinde House, Clapham Park, 3 copies; 20 to Florence; the

remainder to Charles Empson, Esq., The Walks, Bath.

In a further letter he wrote, saying:—

"DEAR SIR,—I

forgot, it seems to me, a few persons to whom it seems desirable a part of

my hundred copies should be sent:—

3 to Mr. Carbonell, Camden Street, Camden Town.

3 to Mrs. West, Ruthen Castle, Denbighshire.

3 to some Masters in Chancery, whose sorry adversaries have tried to

obtain an injunction that nothing should be paid to me or my family out of

my estate.—I remain, Dear Sir, truly yours,

W. S. LANDOR."

As I had become unwell from overwork, my brother Austin reported what had

been done, and the following letter Landor wrote to him:—

"DEAR SIR,—I am grieved to hear of your brother's illness. I very much

esteem him, and hope he may soon regain his usual health.

"Many thanks for your care in sending the copies according to my

direction.

"I know nothing of the American publishers, but will inform my friends in

that country that they may obtain copies from New York. My opinion is that

many would be sold in that country. I am, Dear Sir, yours very truly, W.

S. LANDOR.

"Mr. AUSTIN HOLYOAKE.

"Pray send 3 or 4. copies to J. Forster, Esq., Montague Square, London"

(not remembering that he had mentioned them before). His next letter was to me:—

"MY DEAR SIR,—I am as sorry to hear of your continued illness as at my

failure of obtaining redress in my grievous wrongs. It may be necessary

that the title page containing

your name should be torn off; but surely then it would be quite safe to

send a dozen copies to Captain Brickman, Beaufort Buildings, Bath, with my

compliments. Could not the whole come out as printed at Genoa? This is

suggested to me as being safe and practicable. Of what is now printed,

send me a dozen, without the title page containing your name. I have

promised them to friends about to leave Rome and Florence for a tour in

Switzerland.—I remain, my Dear Sir, with high esteem, yours, W. S. LANDOR."

In the letters I quote of Landor's in relation to his defence, I omit many

remarks and also names which, however justifiable they were from his pen

in relation to his own cause, I, who have no resentment to pursue, do not

reproduce. They would be painful to others or the survivors of others. Forster in his "Life of Landor" quotes some letters which ought to have

been omitted for the same reason. What is true, unless it has public

interest or instruction, should have no place either in history or

biography; and what is known to be untrue, and which Landor, being a man

of good faith, would not persist in when it was shown to be untrue, should

be precluded from repetition.

The next letter I quote in full:—

FLORENCE, Oct. 5.

"My DEAR SIR.—On the tenth of last month I wrote a few lines to you

enclosing a letter, in reply to a very polite one, remonstrating on mine

to Emerson. A few days ago, I found my few lines intended for you in my

desk. Pray let me hear, at your leisure, whether this reply ever reached

you; for several of my prepared letters entrusted to a servant never

arrived at their destination.—Believe me, Dear Sir, very truly and

thankfully yours, W. S. LANDOR."

Forster, in his "Life of Landor," if I remember rightly, relates that

Emerson had seen some wonderful microscopes in Florence, and spoke of the

uses to which they were applied; but he found that Landor despised

entomology, yet in the same breath said, "The sublime was in a grain of

dust": which anticipated the fine saying by Herschel about the microscope

and telescope being explorers of the infinite "in both directions."

So far as I know, Landor's reply to the friend who remonstrated with him

concerning his letter to Emerson has not been published. It covers four

large quarto pages. Singularly, being from Landor, it was against the

impending war for the extinction of negro slavery. It is a remarkable

defence of the Southern side of the argument. I cite here only a few

sentences in which his bright precision is visible in every one:—

"Interest is a stronger bond of concord than affinity. Beware of

inculcating unintelligible doctrines. Men quarrel most fiercely about what

they least understand. Laws are religion; let these be intelligible and

uncostly. It is pleasanter at all times to converse on literature than on

politics. However, on neither subject are men always dispassionate and

judicious. They form opinions hastily and crudely, and defend them

frequently on ground ill chosen. Few scholars are critics, few critics are

philosophers, and few philosophers look with equal care on both sides of a

question."

One day I received the following letter:—

"6, CLIFFORD

STREET, July 7, 1872.

"DEAR Mr. HOLYOAKE, I remember well having a little talk with you. At

what time of the day are you at home, as I should like to renew the

acquaintance.—I am yours sincerely,

"HOUGHTON."

I answered Lord Houghton, saying I should appreciate the honour of his

calling. Ordinarily I was at 20, Cockspur Street, where I then resided,

from 5 to 9 p.m. When the House of Commons sat in the morning, I was home

much earlier; but it was an act of mercy to say that my chambers were at

the top. Once there it was a pinnacle from which could be seen all the

kingdom of London and the glory thereof; but I include no other feature

in the reference, remembering Lord Brougham's admonition, "Beware of

Analogy."

Afterwards Lord Houghton asked me "to give him the pleasure of

breakfasting with him at Clifford Street at 10.30 on Saturday next, the

20th instant."

The breakfast justified the celebrity Lord Houghton's morning repasts had

obtained. Several breakfasts and dinners remain in my mind. Even the

flavour as well as the charm I can recall; but for profusion and variety

of joints, birds, fish, wines, fruits, coffee, and cigars, Lord Houghton's

breakfast exceeded all. I remember the astonishment he expressed to a new

footman who brought in coffee half an hour before the birds and wine

ended. On an easel near the table was a new portrait in oil of Landor,

which was shown to every one. This led me to mention that I had several

letters of Landor's, at which Lord Houghton expressed great interest, and

I promised he should see some of them. I made up a parcel, with notes

explaining them. Being precious in my eyes, I left them myself at his

house. I heard no more of them. At times I sat behind him when he came to

the Peers' Gallery in the Commons, and expected he would refer to them. At

length I wrote and asked for their return. In July, 1873, he wrote from

the House of Lords to say, "he was distressed to find that, acting on the

supposition that I had given him the Landor MSS., he had bound some of

them up with one of his books. If worth while, he would take them out

again and send them." As he had never acknowledged their receipt, I did

not understand how he came by the impression that I had given them to him. It was as proofs of Landor's confidence in me that I most valued them, and

also as evidence of the risks I was willing to incur for him. The letters

his lordship had bound up I told him "I was quite content should remain in

his possession, as it would be a pleasure to think they would be preserved

by him." As Lord Houghton was a valued friend of Landor's, I felt that he

was a congenial custodian of relics of him. He sent me copies of the

letters he retained, and others which accompanied them he returned,

writing:—

"FRYSTON HALL, FERRYBRIDGE, Nov. 28, 1873.

"MY DEAR SIR,—I am obliged for the loan and the gift. I am afraid Landor's repute still remains in the world of men of letters, and not in

that of national literature. There is no doubt that with him the thing

said is less important than his manner of saying it. Every day we become

less and less careful of style for its own sake.—Yours sincerely,

"HOUGHTON."

On such a subject no opinion of mine is comparable with Lord Houghton's;

nevertheless, I own I value Landor's writing for its sense as well as its

style, and think that his "repute" in "national literature" is higher and

more assured than Lord Houghton supposed.

Landor did me the honour to write to me many times (after the affair of

his pamphlet) on Italian affairs. Some communications I sent to the

Newcastle Chronicle where they would be more influential than in any

paper of mine; some, relating more to social life and character than to

public affairs, I inserted in the journal I edited. Landor made scarcely a

correction in his proofs. He was sure of what he wanted to say, and said

it in unchangeable terms. He seldom dated his letters. In one from Scena,

July 3 (during the Italian struggle), he remarks:—"If I had any

photograph, I would gladly send it you. Three were sent to me from Bath,

but I know not the name of the artist. Ladies have all three." He wrote

with enthusiasm of Garibaldi, saying, "I hope Sicily may become

independent, and that Garibaldi will condescend to be its king under the

protection of Italy and England." The following sonnet he sent me ends

with a fine line on Garibaldi:—

|

"SICARIA.

Again her brow Sicaria rears

Above the tombs: Two thousand years

Have smitten sore her beauteous breast,

And war forbidden her to rest.

Yet war at last becomes her friend,

And shouts aloud

'Thy grief shall end.

Sicaria! hear me! rise again!

A homeless hero breaks thy chain.'" |

Walter Savage Landor I admired for his force, simplicity, directness, and

the wonderful compression of his style: for his singular fearlessness,

determination of thought, and his Paganism. As I was precluded from

engagements on the press by reason of my name, I adopted that of "Landor

Praed." Landor in his graceful way sent me his authority to use it, for

reasons I may not repeat, as they existed alone in his generosity of

judgment.

One night near the end of his days, after Charles Dickens and John Forster

had left him on their last visit, he wrote his own epitaph in these noble

words:—

|

"I strove with none—for none were worth my strife:

Nature I loved, and, next to Nature, Art.

I've warmed both hands before the fire of life:

It sinks, and I am ready to depart." |

He said, in his incomparable way, "Phocion conquered with few soldiers,

and he convinced with few words. I know of no better description of a

great captain or a great orator," which might be said of himself.

CHAPTER LX.

IN CHARGE OF BOMBSHELLS.

(1856.)

IT was at Ginger's Hotel, which then stood near

Westminster Bridge, that I first saw the bombs whose construction was

perfected afterwards for use in Paris, in the attempt to kill the Emperor

Napoleon III. The bombs were in sections then. When strangers

came into the coffee-room, Dr. Bernard laid them back on the seat between

him and a friend. Understanding machine work, I could judge whether

they were well devised for their purpose, which was my reason for being

there. At a later stage I was told that Mazzini thought they might

be useful in the unequal warfare carried on in Italy, where the insurgent

forces of liberty were almost armless. [20]

He who gave the order in Birmingham for their manufacture,

also gave his name and address at the same time, and went down to see the

maker when there was delay through doubt as to the kind of construction

specified. He used no disguise or concealment of any kind. He

acted just as an inventor might act who wanted a new kind of military

weapon made. When two of the shells were afterwards delivered to me

to make experiment with, I understood that they were a new weapon for

military warfare in Italy, to be used from the house tops by insurgents,

when the enemy might be in the streets firing into houses, as the Louis

Napoleon troops did in the days of the Presidential butchery in Paris at

the coup d'état of 1852. At the time of the meeting at

Ginger's Hotel, if there was any thought of operating in Paris, the design

was known only to the six persons ultimately concerned—among whom neither

myself nor Mazzini was included.

When the war-balls came into my hands I had small conception

of what I had undertaken in consenting to test them. The detonating

powder with which they were filled had been prepared for quick explosion.

"Elizabeth," a courageous young woman engaged in the household in which

Orsini resided, had, well knowing the danger, superintended the drying of

the powder before the kitchen fire, where, had accident happened, she had

been heard of no more, and any persons above would have been made

uncomfortable. Percussion caps were on the nipples of the shells

(which, like porcupine quills, stuck out all round them) when I received

them. Their bulk being from four to five inches in diameter, they

were heavy enough to be quite a little load to carry about; and thinking

that any force used in removing the caps, which were firmly fixed, might

cause an explosion, for which I was not provided, I left them on.

Deeming it best to carry them apart, lest coming into collision with each

other they might give me premature trouble, I put one into each of the

side pockets of my coat. As I went along the street it occurred to

me, that it was undesirable to fall down, as I might not be found when I

wanted to get up. When I arrived at home I packed the bombs

considerately in a small, harmless-looking black brief bag; but where to

put the bag was the question. I had no closet which I was accustomed

to lock, and to do it might occasion questions to be put which I did not

want to answer, as the truth might create apprehension that the

inscrutable things might go off of themselves, which for all I knew they

might. This was, however, the only futile apprehension that occurred

to me, for my wife made no trouble about the matter, and found a place of

safety for the parcel. She had respect for those for whom I acted,

and readily aided.

The next morning found me setting off to Sheffield, where I

had an engagement to lecture, and in which town I had proposed to try this

new weapon of war. The insurgent leaders of that day had no funds to

spare; and by choosing a time when I had to travel anyhow, it avoided the

expense of a special journey. The selection of Sheffield was made by

me as being a noisy manufacturing town, where the addition to its uproar

of a bomb going off would be little noticeable. Going on the journey

out to the railway station, I did not take a cab through fear the cabman

or porter might snatch up the bomb-bag in which I had placed the shells,

and afterwards throw it down carelessly. So I carried that bag in

one hand and my portmanteau in the other. At the station I found

opportunity of putting the contents of the bag into my pockets. I

was afraid of the bag in the carriage: it required so much watching.

A passenger might at any minute suddenly remove it to make room for some

box which might strike against it, and as suddenly disperse the travellers

themselves. Besides, I could never leave the train for refreshment,

with the bag in it; and the third-class journey was long in those days

from London to Sheffield—the Midland Company not having set the generous

example of carrying third-class passengers with swift trains. With a

shell as large as a Dutch cheese in each pocket, I looked like John Gilpin

when he rode with the wine kegs on either side of him. But I passed

very well as one who had made ample provision for his journey. My

only anxiety was that some mechanic with his carpenter's or plumber's

basket might choose to sit down by my side, when a projecting hammer or

chisel might be the cause of an unexpected disturbance. For the same

reason I thought it wiser not to sit in the corner of the carriage, where

one of my pockets oscillating against the side by sudden motion of the

train might occasion difficulties there.

On arriving at Sheffield the trouble did not end. In

the house where I lodged new perplexities arose. I might ask for a

closet in which I might lock up my peculiar luggage, but my landlady might

have a duplicate key and be just curious to see what I was so careful in

securing; and thus some accident might ensue upon the discovery.

This fear deterred me from that expedient. My watchfulness kept me a

prisoner in the house, and when I went below to write I took the bag and

placed it on the table, keeping pens and paper in the same receptacle to

divert attention from the other contents. Sunday was an entirely

troublesome day with my percussioned companions, because I had to carry

the bag twice to the morning and evening lecture and place it upon the

table before me while I spoke. As I took my notes and papers from

the bag, its presence on the table was a matter of course. It was

not prudent to put it under the table, lest the toes of some excited

adversary might kick against it there. Had my opponents, who were

numerous at that period, had any idea of the contents of my bag, they

would have been very brief in their observations. At night I was

again solicitous, fearing something should occur in the house, where there

were many inmates.

Monday was welcome to me when I could take one of the

missives out with me and seek a place for its explosion. As I might

need to move rapidly after throwing it, I concealed the one I left behind

between the mattress and the bed in my room, after the bed was made for

the day. Had anything happened to me to prevent my return, the next

lodger sleeping in the bed had found something quite inexplicable under

him. I had lived in Sheffield and knew my way about, having walked

through its suburbs with Ebenezer Elliott

and other rambling friends of that time. But I had never

observed the roads with a view to present requirements. I walked in

various directions until afternoon, before finding a sufficiently straight

road, without houses upon it. It was necessary to command with my

eye a long sweep of way, since I must operate in the middle thereof, and

be sure that no person could enter upon it from either extreme without my

seeing him. Besides, I had to examine both sides of the road to be

certain there was no lane or bye-path by which unseen persons could emerge

and be struck by any flying fragment about at that minute. After all

my trouble, pedestrians, or vehicles, or horsemen, were continually coming

into sight; and I had to return home without making any attempt that day.

And night was useless, it being more dangerous for my purpose than day.

Had I had a companion to keep watch with me, we might have found an

opportunity; but it was my duty not to trust any one with a knowledge of

my object. There was no knowing what alarm he might take at being in

my company with the uncertain missives I bore about me.

The next day I took a different course—that of selecting a

disused quarry, as that would test the quality of the bombs under the most

favourable circumstances. If one would not explode by its own

momentum of descent on so hard a floor, it would show that its

construction was an entire failure. The quarry was in an immediate

suburb, not very far from the centre of the town. There were several

villas in sight of it, with gardens that came near to the verge of it.

What would be the amount of noise I should create, or what would be the

effect of it, I could not tell. I had to trust that it might pass

among other commotions to which Sheffield was subject. Having

examined the quarry to ensure that there was no one in it, and finding no

one above, I threw the bomb from the top—from a point where I could

shelter myself in case the explosion brought any fragments my way.

The sound was very great, and reverberated around. Expecting people

would run from their houses, I quickly arose and sauntered away. I

met a person hastening towards the spot. "Did you hear that great

noise?" he asked. "Oh, yes!" I answered. "I think it came from

the quarry," he replied. "Had it come from there I must have seen

it," I answered, "as I passed by it. It might be some cannon firing.

If you can show me a pathway to yonder field, we should see if there is

anything going on there." He turned and went with me, but we found

nothing there. I was desirous he should not get to the quarry until

the smoke had disappeared. Later in the day I returned to the place,

lest some portions of convexed-nippled iron should lie about, which being

found might excite curiosity; but nothing was to be seen. I posted a

paper to London, without address or signature, saying:

"My two companions

behaved as well as could be expected. One has said nothing; perhaps

through not having an opportunity. The other, being put upon his

mettle, went off in high dudgeon. He was heard of immediately after,

but has not since been seen."

Finding the deposited shell in the bed where I had left it, I returned to

town with it, when it was proposed that I should take another shell with

the one I had, and proceed to Devon, where dwelt one who had the courage

for any affair advancing the war of liberty. For this journey I

received thirty-two shillings, as the distance was great; and this was the

cost of the third-class fare. It was the only expense to which I put

the projectors of these wandering experiments. The object was to

ascertain whether the new grenades would really explode, when thrown as

high as a man could throw them, and falling on an ordinary road. The

journey West was less troublesome than that to the North, as the railway

carriages were less crowded, and mechanics carrying tools were much fewer.

My friend lived in "The Den." This was the actual name of his

residence, and not inappropriate, considering the nature of the business

we had on hand, when we two issued from it. The vigilance falling to

me was much diminished, as my host could take care of my "brief bag" when

I needed personal liberty.

We soon found a suitable highway. My friend watched the

way, and, being tall, could take a wide range of view; but it was

necessary to choose a field which had a stone fence, where, after throwing

the bomb into the air, I could at once lie down and be protected while the

fierce fragments flew around. There was, however, little need of the

precaution, as no explosion followed. The nipples buried themselves

in the earth, and the obstinate shell remained fixed and silent. I

had not foreseen this, and it was necessary to remain on the ground a

while lest the thing might go off after some time. It was not

possible to wait long, for a signal told me a passenger was descried.

The difficulty then was to get the perverse ball out of the earth, since

plucking it might occasion an abrasion of the cap, and cause it to burst

while I was over it. Happily, I restored the wilful shell to my

pocket and I went to meet the traveller to ask him "if he knew where there

was a good place for football about "—in case he had observed the unusual

movements on the way.

Having no taste for further trials on the common roads, we

found opportunities of throwing the two portable thunderbolts on a really

hard surface, where, with loud report, every fragment flew into

untraceable space. It was not without satisfaction that I saw, or

rather heard, the last of my perplexing companions. My next report

to London said:—

"Leniency of

treatment was quite thrown away upon our two companions. As a man

makes his bed, so he must lie upon it; still out of consideration, we

wished it to be not absolutely hard. But that did just no good

whatever. The harder treatment had to be tried: and I am glad to say

it proved entirely successful. But nothing otherwise would do."

The result of the experiments was that the bombs in the first state in

which they were perfected were proved to be inefficient; unless thrown to

a great altitude in the air they would not explode on an ordinary roadway.

If the percussion caps did act, they failed to ignite the contents of the

shell. Except upon a well macadamized and hardened ground, or upon

flagstones, they could not be depended upon for the purposes for which

they were intended. They would not answer for ordinary military

operations, where the surface might be soft ground or grass land.

Whether the bombs used in Paris were improved, or whether the choice of

Rue Lepelletier, where the ground was firm, was determined by the

experiments upon which I reported I never inquired. [21]

If my report ever became known to any one concerned in that affair, it

probably had some instructive result.

CHAPTER LXI.

ORSINI THE CONSPIRATOR.

(1856.)

OIRSINI was an egotist, but, like Benvenuto Cellini,

he had something to boast of. His love of heroic distinction helped

to make him a patriot; the passion for renown helped him to excel all

other patriots in daring and in doing things of which Italian patriotism

may always be proud. The escape of Baron Trenck was not more

wonderful than Orsini's escape from the impregnable fortress of San

Giorgio. The narrative of his astonishing adventures, published

under the title of "The Austrian's Dungeon," and translated by Madame

Mario, shows, in force of narration, that he was a good writer as well as

an intrepid soldier. When it was ready for the press he came to me,

through the instructions he had received, for suggestions as to the best

mode of issuing it. I see him now as he stood in the shop in Fleet

Street, the sun falling upon his dark hair, bronzed features, and glance

of fire. I told him I would bring out his book gladly, but that

Routledge was able to put many more thousands into the market than I was,

and would no doubt give him £50 for the MS., which, though it did not

amount to much, was of moment to an exile. Routledge did give him

£50. The title, "The Austrian Dungeons in Italy," was one of

interest at the period, but, if reprinted under the title of "The

Wonderful Escape of Orsini," or some other which indicated its

marvellousness, it would have interest in the literature of adventure as

permanent as Silvio Pellico's story. There were heroes in Italy all

about. Bystanders took Orsini, lame and stained with mud and blood,

on the morning of his escape, and secreted him with a certainty of

themselves suffering torture and death in the same fortress, were they

discovered. The whole district was then overrun with spies. He

who realises this will appreciate the courage and resource of the peasant

people—only to be matched in Ireland. I know of no single book

concerning Italy which more stirs the blood of indignation at Austrian

subjugation than Orsini's narrative. The address appended to his

book (he could give his address in England) was 2, Cambridge Terrace, Hyde

Park, July 10, 1856. A year later he was headless.

|

|

|

Felice Orsini

(1819-58) |

Felice Orsini relates that an Austrian colonel was one day galloping

through Mercato di Mezzo, followed by a large dog. A youth of

sixteen was passing by with a smaller dog, which was attacked by the

colonel's and almost killed. To save his dog, the youth picked up a

stone and hurled it at the colonel's. By chance it struck its head,

and it fell dead. By order of this colonel the youth was arrested

and sentenced to 30 blows on the cavaletto, which meant 90 strokes of the

bastinado—for three strokes counted as one blow. When the

unfortunate youth was removed from the Cavaletto he was dead. On the

following day the colonel was sitting with some of his fellow officers in

the Cafe dei Grigioni. A man suddenly appeared in their midst, and

after despatching the colonel with several stabs of his poniard,

disappeared before any one could arrest him. This was the father of

the boy who had died under the bastinado. That was a righteous

assassination. Orsini, by his attempt to destroy the French usurper,

intended also to avenge Italy upon the false President of the Republic who

sent troops to put down the heroic Republic of Rome. Orsini perilled

his head to do for France what thousands wished done, and no one else

attempted, with the same determination. When Cato visited the palace

of a tyrant and saw the persons he put to death, and the terror of the

citizens who approached him, he asked, "Why does not some one kill this

man?" Orsini came forward in like case to do it. Those who

engage in political assassination should have no hesitation in sacrificing

themselves. If they are careful for their own welfare, they lose

their lives all the same. By using bombs, Orsini imperilled the

lives of others, and, being wounded by a fragment which filled his eyes

with blood, was unable to complete his design. After his execution

at La Roquette, a compromising article appeared in the Westminster

Review, upon which I addressed the following letter:

"147, FLEET STREET, June 1, 1860.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE 'WESTMINSTER REVIEW.'

"DEAR SIR,—On

the part of the colleagues and friends of Orsini, I am requested to

solicit your attention to the following passages in the Review for

January, 1860. We believe we shall not appeal to you in vain to do

justice to the dead. What is asked is the correction or proof of the

statements questioned.

"You say—'Through a confidential agent, he (Louis Napoleon) conveyed a

solemn assurance of his intentions to Orsini, who had been a member of the

same Carbonaro conspiracy in 1831 with the Emperor. Orsini declared

himself satisfied with this communication. He gave the persons who

brought it a. list of friends in Italy, whose co-operation was to be

sought at the proper time, and then wrote as the testament of his dying

convictions the famous letter, pointing to Napoleon III. as the

coming liberator of his country, which was printed in Turin, having been

sent thither by the Emperor for publication. Soon followed the

interview at Plombieres with Count Cavour, and the project succeeded

rapidly towards execution.'

"In connection with this statement, I submit the following facts:—

"Orsini was not born until the end of December, 1819.

"In 1831, when he is alleged to be a joint conspirator with Louis

Napoleon, Orsini was a boy at school, being only eleven years of age; and

he remained at school until 1836—until he was sixteen.

"It was not until 1843 that he was a member of any secret society.

"He never was a member with the Emperor. He never was a Carbonaro at

all.

"He never saw Louis Napoleon before the year 1857.

"The 'famous letter' referred to was not in Orsini's French. He did

not write French well. The letter appeared in pure Florentine

Italian. Orsini was educated as a Bolognese, and was by no means a

master of good Italian.

"Without proof it is not to be believed that Orsini, of all men, would

'give a list of his friends' to the man whom he sought to kill. He

was not the man to do it to save his own life. Was he likely to have

done it when his life was not to be saved? Without proof, no assertion of

this kind is to be believed. It is a serious calumny upon Orsini,

and to be resented.

"Again you state that—'The Emperor learnt at Milan, from the mouth of his

own couriers. . . . and especially of that

confidential one whom we have repeatedly mentioned, and who brought to

Milan the discouraging results of his interview with Orsini's friends,

whom he had found deaf to Bonapartist suggestions.'

"No doubt they were found 'deaf.' Were they ever found at all? No such

persons have ever been visited. A confidential agent of the Orsini

party has been sent over the whole ground, each capi or chief of

sections has been inquired of, and the answer of each is that no

Bonapartist emissary nor any such pretended communication has ever reached

them. The 'confidential one' whom the writer 'repeatedly mentioned'

was M. Pietri.

"The Westminster Review has given too many proofs of its profound

sympathy with Continental liberty, and for those who have given their

lives to promote it, for the friends of Orsini to be under any other

impression than that you have been mislead or misinformed of the facts of

Felice Orsini's character and career.—

Yours faithfully, G. J. HOLYOAKE."

With his usual fairness and promptness the editor inserted this letter at

the end of the next issue of the Westminster Review, regretting

that he had inserted the communication, which he believed at the time to

be trustworthy.

When in England Orsini was for many weeks the guest of a

friend in the North, whose doors were always open to exiles. His

daily habit was to ride through the country, and his fine figure and

handsome resolute face was met by passengers as he galloped through

splendid scenes and over sterile moors where the volcanoes of industry

reminded him of those of his own brighter land.

When Madame Herwegh presented Orsini with white gloves, he

laid them aside to wear on the morning of his execution, although he was

then free. He had so often been near death that he thought death

always near him, and, as it was impossible for him to cease to conspire

for the freedom of Italy, he regarded himself as destined to the scaffold.

He had known the perils of prisons—he had mastered the language of stone

walls—the language of misery—by which the last messages of the condemned

are struck from cell to cell. When the last hour came and Pierri,

who was with him, faltered, Orsini, not only undaunted but bright and

daring as was his wont in danger, counselled Pierri to be of good courage

and acquit himself as a patriot should.

CHAPTER LXII.

A FRENCH JACOBIN IN LONDON.

(1856.)

|

|

|

Louis Napoleon

(1808-73) |

FROM

1851 to 1856 we had a real French Jacobin active in England, sprung like a

Revolutionary Phœnix from the ashes of the Parisian clubs of 1793—Dr.

Simon "Bernard le Clubiste," as he signed himself in his first letter to

The Times. Dr. Bernard was born in Carcasonne in 1817.

A physician by education, he, as surgeon on board a man-of-war, displayed

intrepidity in two or more sea battles. He was a Phalansterist of

the school of Fourier. He edited insurgent papers, and was chairman

of the club of the Bazaar Bonne Nouvelle, where he addressed five

thousand people nightly. Unintimidated when his colleagues were

shot, he carried the agitation to Belgium, and was soon in prison and on

his trial there. He got into trouble about Robert Blum, the

publisher, who was shot by the Austrians in Vienna. Eight

prosecutions had spent their rage upon him, when in 1851 he came to

England, and practised as a physician at 40, Regent Circus, Piccadilly,

London. Before two years were well gone he was in Newgate. His

knowledge of the physiology of elocution, in which he excelled, and of the

cure of the impediments of speech, would soon have brought him fame and

fortune. His skill in Belgium had brought him great renown. We

who knew him, liked him for his simplicity, genuineness, and courage.

Becoming involved in the Orsini affair, he was tried for his life at the

Old Bailey, in London, and would have been condemned had it not been for

the defiant spirit of a city of London jury, who would not convict any one

at the bidding of a foreign power. Louis Napoleon, the usurper, was

understood to ask that Dr. Bernard should be put upon his trial, which was

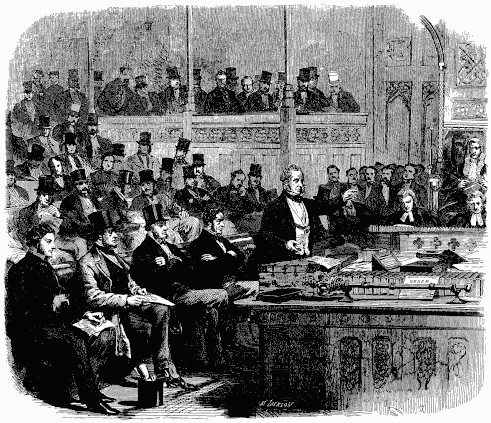

done. The case lasted five days. Edwin James, an advocate

politically popular in his time, defended the doctor. I was in

court, and heard with amazement his ornate appeal so materially destitute

of facts. He was unacquainted with what he was supposed to know, or

might have known—and should have known. The Attorney-General, Sir

Fitzroy Kelly, who prosecuted, made it a point of horror that a letter

from Orsini found in Dr. Bernard's room inquired "How about the Red and

Co.," which the jury were told, with upturned eyes and uplifted hands,

referred to the "Red Republic," for which the doctor and his terrific

correspondent were plotting. All the while Orsini's letter merely

inquired after a lady, the colour of whose hair he exaggerated because she

had refused his offer to marry her. He always afterwards referred to

the committee of which the lady was a member as the "Red and Co."

Mr. Edwin James had no explanation to give. He had not

inquired into the facts of the case which a question would have elicited.

The Attorney-General Kelly was he who shed tears before the jury in

attesting the innocence of the Quaker, Tawell, who had confessed to Kelly

that he had murdered the woman at Berkhampstead, for which Tawell was

hanged. From Sir Fitzroy, pious without scruples, Dr. Bernard had

nothing to expect. Edwin James, his counsel, trusted entirely to the

hereditary spirit of English defiance of foreign dictation, and modelled

his appeal to the jury on the famous reply of Mirabeau to the message of

the king. Fortunately for Dr. Bernard, this intrepid eloquence

succeeded. Spoken in a loud, strong, imperious voice, the following

is the passage which won, or justified, the verdict:—

"Gentlemen, I need not remind you that it has been of the greatest

advantage to this country that her free shores have been open to exiles

from other lands. The revocation of the Edict of Nantes drove to our

shores the Saurins, the Romillys, and the Laboucheres, who have shed a

lustre on this country. Will you, then, at the bidding of a

neighbouring despot, destroy the asylum which aliens have hitherto

enjoyed? Let me urge you to let the verdict be your own, uninfluenced by

the ridiculous fears of French armaments or French invasions, such as were

raised in Peltier's case. You, gentlemen, will not be intimidated;

you will not pervert and wrest the law of England to please a foreign

dictator! No. Tell the prosecutor in this case that the

jury-box is the sanctuary of English liberty. Tell him that on this

spot your predecessors have resisted the arbitrary power of the Crown,

backed by the influence of Crown-serving and time-serving judges.

Tell him that under every difficulty and danger your predecessors have

secured the political liberties of the people. Tell him that the

verdicts of English juries are founded on the eternal and immutable

principles of justice. Tell him that, panoplied in that armour, no

threat of armament or invasion can awe you. Tell him that, though

600,000 French bayonets glittered before you, though the roar of French

cannon thundered in your ears, you will return a verdict which your own

breasts and consciences will sanctify and approve, careless whether that

verdict pleases or, displeases a foreign despot, or secures or shakes, and

destroys for ever the throne which a tyrant has built upon the ruins of

the liberty of a once free and mighty people."

Lord Campbell—one of those Whigs who apologise for their honourable

sympathy with liberty by acts which Tories might covet, and then wonder

why they are not popular—summed up for conviction. As the jury were

about to retire, Dr. Bernard, lifting his hands and standing erect in the

dock, exclaimed with great fervour, "I declare the words which have been

used by the judge are not correct, and that the balls taken by Georgi to

Brussels were not those which were taken to Paris. I have brought no

evidence here, because I am not accustomed to compromise any person.

I declare that I am not the hirer of assassins, that Rudio has declared in

Paris, on his trial, that he asked himself to go to Orsini. I was

not the hirer of assassins. Of the blood of the victims of the 14th

of January there is nothing on my heart any more than on any one here.

We want only to crush despotism and tyranny everywhere. I have

conspired—I will conspire everywhere—because it is my duty, my sacred

duty, as of every one; but never, never, will I be a murderer,"

On the verdict of acquittal being given, men waved their

hats, the members of the bar cheered, ladies stood on their seats and

waved their handkerchiefs or their bonnets, and cheered again, and again,

the crowd outside catching indications of the nature of the verdict, sent

back in still louder cheers, their greetings at the result.

"At length," says The Times reporter, "silence was

restored, and Bernard, whose eye sparkled, and whose frame quivered with

intense emotion, said, in a loud voice, "I do declare that this verdict is

the truth, and it proves that in England there will be always liberty to

crush tyranny. All honour to an English jury!"

Thus the great Jacobin escaped being hanged. Unhappily

he came to a more lamentable end. A bewitching angelic traitor was

sent as a spy to beguile him, and to her, in fatal confidence, he spoke of

his friends. When he found that they were seized one by one and

shot, he realized his irremediable error, lost his reason, and so died.

Dr. Bernard had every virtue save prudence. I observed

with apprehension that he would talk in a loud voice in the streets, of

things it were best to whisper with circumspection in private. It

suggested itself to me that if I conspired it would be well to watch the

ways of him I conspired with. Dr. Bernard had that fervour which

made him imagine all the world had come to his opinion, and took the town

into his confidence. Partly it was England that misled him, he could

not imagine that spies were in English streets.

Edwin James was not a man of many scruples. When he was

a candidate for Marylebone he spoke one day at the usual hustings at the

Regent's Park end of Portland Place. His adversary put himself

forward as a "Resident Candidate," when James exclaimed, "I may be one day

a happy resident—but, alas! as yet I have no wife and family." "You

old incubator," exclaimed a loud-mouthed and abrupt elector, "you have

three families in the borough already, and you know it!" The "gentle

Edwin" was not abashed, but laughed and spoke on. The electors knew

when they voted for him that he would sell them if he could get a price

for them, calculating that, if he could not, he would serve them well.

In which they were right. Within twenty minutes of his entering the

House of Commons after being declared duly elected, I heard him take part

in a debate, and offer himself to Lord John Russell. But Lord John,

when the opportunity came to him, would not buy, and James remained a

popular member—until Lord Yarborough gave him the choice of leaving

England or being indicted here. He went to New York, where the

enemies of the Republic said the bar had fewer scruples as to its

associates. Edwin James found to the contrary. After many

years banishment he returned to England. Re-admission at the bar

being impossible, he began a new legal career, and kept terms in a

solicitor's office, to come up for examination as a new candidate. I

often met him walking to the city at an early hour, pale, sedate,

unostentatious—his ruddiness, grossness, and pomposity gone out of him.

I felt respect for his courage and perseverance. Death intervened,

and he came to his end without attaining his purpose.

CHAPTER LXIII.

THE STORY OF CARLO DE RUDIO.

(1857-62.)

RUDIO—"Count Carlo de Rudio" [22] he called himself,

but there was little of the "Count" about him—was an Italian, and one of

the shell-bearers when Orsini and Pierri made their attack on the Emperor

Louis Napoleon in Paris. Rudio bore a shell, but whether he threw it

is doubtful. "He could not get near enough," he said. Though

deported to Guiana for his reputed share in the transaction, he escaped,

it was believed by connivance of the French authorities there. In a

small boat he managed to reach the English colony of Berbice, and after

wards worked his passage to England. Dr. Bernard stated on his trial

at the Old Bailey that Rudio came and was not sought. Why he came,

or who sent him, demanded scrutiny by those who received him before

employing him, or suffering his participation. He may have been

impelled to join in the enterprize by patriotism, and afterwards have

shrunk from the consequences. The Daily Telegraph of August

30, 1861, described him as one who "betrayed his confederates," and stated

that "the revelations he made were of considerable help towards the

prosecution of Dr. Bernard." The allusion must be to information

given at the time of Rudio's own apprehension. Nothing transpired at

Bernard's trial as to "revelations" made by him.

In England Rudio afterwards asked my advice and aid to bring out a Life of

himself, of which some pretentious numbers appeared. Probably I

published some numbers for him. He went about lecturing. At

some places, as the Telegraph reported, he complained that he was

underpaid for his expedition to Paris, and that "Dr. Bernard only gave him

£14 and his railway ticket"; further, that "Mazzini refused to recommend

him to the Revolutionary Committee." Making these statements looked

like the act of a traitor. It was, as far as his word could go,

fixing on Dr. Bernard a complicity of which he had been acquitted by a

jury, and doing so in a form which no one had attempted to prove against

him. Though Rudio's words did not affect Mazzini, who refused to

recognize him, they served to give the public the impression that Rudio

had a right to look to Mazzini as a patron. My wish was to decline

any communication with Rudio, and I would have done so but for the request

of a friend of Dr. Bernard, who, too generously commiserating Rudio's

condition, besought me and also Mazzini to aid him.

Mazzini, always forgiving to his enemies, had pity for Rudio,

because he was an Italian who had, peradventure, entered into conspiracy

and peril for his country, and because he thought that probably fear had

led him to betray others. At that time attempts were made in

Parliament, and in the press of the governing classes, to connect Mazzini

with every act of insurgency or outrage in Europe, as was afterwards done

towards Mr. Parnell with respect to Ireland. Yet Mazzini incurred

the peril of affording a colourable

pretext for this imputation against him, as he had often done, from

motives of humanity.

One of Rudio's letters to me was the following:—

"4, FELIX PLACE, BARKER GATE, NOTTINGHAM,

"Feb. 16, 1861.

"DEAR SIR,—I have received a letter from your friend, —, which tells me

that you offer yourself to help me in my publication. Of course my

letter is to let you know that my

publication cannot go further for the want of pecuniary means, and I am

obliged to leave off, as I have resolved to leave this town and go

elsewhere, where I hope I shall find

means of subsistence for myself and my poor unhappy family. But, as

I am without the most necessary means of carrying out my views, I will

take the liberty to make

you an offer; and that would be

to sell you the copywrite of my pamphlet, leaving at your consciousness

the value of it. I assure you, dear sir, that no man of my condition

has more suffered than I, in this

last few months especially. Many a day we have been without any

thing to eat—without coal to warm us; twice some propositions very

brilliant has been offered to me; but

them was brilliant to those that have another heart than mine. With

strength of mind I have rejected them, and preferred to suffer than become

a spy. To you, then, I

appeal as a man of religious and political principles equally to those

that I am proud to have; no, sir, no human power shall have the chance of

turning me out of that path

that I have been for twelve years. Death only shall put a stop at my

principles, but until I shall have a drop of blood in my veins I shall

always be ready to run against the

danger for the benefit of our noble cause, though I have been repayed with

the blackest of ingratitude. Still I will pessever while my heart

still beats within me, and the taske I

have undertaken is unaccomplished. Hoping of a reply, I with my wife

and child, send our best expression of gratitude, and believe me, Dear

Sir, your truly and fellowman,

"C. CARLO DE RUDIO.

"P.S.—I hope you will excuse my bad styl of the English language; I have a

great presentiment, 'and that is only the aliment that keeps me a life,'

that I shall no longer stay

without that my person will again be sacrificed for the great principle of

patriotism, liberty, and honour."

This letter, creditably written for one in humble society who had taught

himself, had the fault of protesting his fidelity to one who did not

question it, nor believe it. Interest in

the American Civil War led Rudio to wish to go to that country. By