|

[Previous page]

CHAPTER XIX.

A ROLL-CALL OF IMPRISONED FRIENDS.

(1840-1890)

IF the reader knew how many of my friends have been

imprisoned, or have come to a worse end, suspicion would arise as to the

prudence of proceeding further in my narrative. If no proof of such

assertion is given, it may seem pretentiousness to make it; if it be

substantiated, it may be said that I present a sort of Newgate Calendar of

my friends, whereas the list of their names is mainly a roll-call of

honourable penalties incurred in the service of society. To some I

may recur in separate chapters.

The most illustrious were Garibaldi and Mazzini. Garibaldi had known

imprisonment and torture. From youth to mature age he lived in an

atmosphere of peril; his days passed in battle, in flight, in exile, in

want, in adventure, and in the face of death by flood and field.

Mazzini, greater than Garibaldi, as his sword had been blind had not the

pen of Mazzini given it eyes, underwent vicissitudes of which imprisonment

was the least forlorn and perilous. Mazzini was not merely the great

devisor of action on behalf of liberty, but the inspirer of public passion

which made Italian Unity possible. His life was sought in three

nations. Only an Italian could have kept his head on his shoulders

under such a fierce, organized, imperial, protracted competition for it.

Alberto Mario, the husband of Jessie Meriton White, was several times in

Italian prisons, an intrepid soldier and Republican leader. He was

the confidant of Garibaldi, by whose side he fought in his most

adventurous campaigns, and was a brilliant disciple of Mazzini. He

was an orator as well as a soldier. Handsome, enthusiastic, and

incorruptible, he exercised immense influence.

Orsini, who, like Garibaldi, had a passion for fatal

enterprises, was beheaded. Pierri, without having any such passion,

perished in the same way. Rudio only escaped the headsman's axe, it

was said, by betraying his colleagues. Bottesini was one day called

upon to play at the Tuileries, when Count Bacciocchi, Master of Ceremonies

to Napoleon III., examined his double bass to see whether it contained

Orsini bombs. Orsini headless was a terror to despots.

Aurelio Saffi, second Triumvir with Mazzini, shared the

perils of the defence of Rome, and exile in England. He succeeded

his great friend in representing the Republican principle with similar

refinement, force, and fidelity. In his later years he was a

professor in Bologna, and lived amid the winepresses and vineyards of

Forli, honoured, as I found when last his guest there, as foremost of

those whose intrepidity and devotion contributed to the freedom of Italy.

I had friendly and personal relations with several eminent

Frenchmen who were in peril oft for freedom. Dr. Simon

Bernard, known, like Blanqui, as a stormy petrel of revolution on the

Continent, was involved in the Orsini affair, and his name became noised

over the world. Dr. Bernard, as the reader will see, was in

trouble before he took refuge in England. Eight prosecutions had

been instituted against him; twice he had been condemned to imprisonment,

and here he narrowly escaped the hangman. Some who were personally

in contact with him came to share his danger.

Ledru Rollin was an exile here to escape the same fate.

We always held him in honour, as Mazzini said he was the only Frenchman

who sacrificed his political position for a country not his own—namely,

for justice to Italy. I had the honour to defend him when in

England. Mazzini never ceased to inspire friendships for him.

Rollin was too little in England to understand us. Mr. Horace

Mayhew's famous letters in the Morning Chronicle on the condition of the

industrious classes in London, misled Rollin into the belief that England

was played out. He was confirmed in this belief by the speeches of

Tory orators in Parliament, who were always saying, when any measure of

reform was proposed, that the British Constitution was exploded, and that

the sun of England was going down for ever. He did not know that the

Tories are the professional defamers of the land. During more than

half a century, to my knowledge, the sun of England has set for ever every

year, and has always turned up again in the next spring. These

whimsical predictions so bewildered Ledru Rollin that he published a book

on the "Decadence of England," which caused him loss of prestige among us.

He never observed that England had still vitality, since it was able to

protect him against the wrath of the emperor of his own land, who would

have pursued him here had he dared.

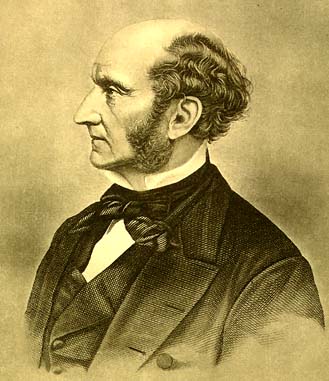

Louis Blanc I knew during all the years of his exile, and was

invited by his family to his burial in Père la Chaise. Next to

Mazzini, he was master, not only of the English tongue, but of English

ways of thought, and understood the land. He made no mistake like

Ledru Rollin. Louis Blanc showed me original records of the great

French Revolution, amid which were letters stained with the blood of those

who had written them. Louis Blanc was a small man, but he was so

entirely a man—you never thought of his stature. He had an

impressive face, a firm mouth, and was without any of that assumption of

manner which small men often wear lest you should not recognize their

importance. Louis Blanc had conscious power which needed no

assertion. Though he acquired English staidness of deportment, his

French fire broke out in platform speech. He was the greatest

expositor of Republicanism, democratic and social, of his day. When

Louis Blanc was first an exile here, he was not credited with the fine

qualities he possessed, which became apparent in the protracted years of

exile. Seventeen years after the Presidential treachery of 1852, the

electors of the Seine, Marseilles, and other places besought him to

reappear in Parliament, but he would take no oath of allegiance to the

Usurper. He answered, "The distinction of Republicanism is

inflexibility of principles—its love of the straight line—its solicitude

for human dignity, and its passion for equality." In reply to the

suggestion that he should take the oath, he remarked, "The oath, it is

said, is an idle formality. Let us not repeat this word too often,

if we desire to raise the standard of public morality. There is one

man, the Emperor, who has considered it a 'mere formality,' and France

knows what has come of that." Louis Blanc added, "A noble example is

an act." St. Just said, "Those who do nothing are strong"—when

action is dishonour. Louis Blanc remained an exile until the fall of

the emperor.

|

|

|

Louis Blanc

(1811-82) |

Louis Blanc had a brother, Charles, who was a member of the French

Academy. M. Pailleron, who succeeded him, thus described both:

"Charles was exuberant, passionate, even violent; but easily

resigned, amiable at bottom, and above everything good—a reed, painted

like iron. Louis, on the contrary, was gentle, humble, timid,

polite, almost obsequious; yet beneath this mild exterior tenacious,

resolute, rebellious—iron, painted so as to resemble a reed."

Of Carlo de Rudio and his troubles I have written in another

chapter. He set himself forth as "Count" de Rudio, but if he were a

count, his education had been neglected.

Victor Schœlcher, a stormy exile upon whom the French Emperor

tried to lay hands, was a frequent visitor to the Reasoner office, and a

frequent subscriber to our insurgent funds. He was a man of high

character and strange experience, and in his day had rendered the State

important service. After the fall of Louis Napoleon at Sedan,

Schœlcher returned to France, and was accorded the dignity of a Senator.

There are pretentious friends of the advance of society who, when they

cannot do what they would, do nothing. Schœlcher, when he could not

do all he wished, did what he could.

Ulric de Fonvielle, my friend and sometime host, accompanied

Victor Noir on a visit to Prince Pierre Napoleon, who shot Victor Noir

dead, and fired twice at Ulric de Fonvielle. A very uncivil

gentleman was Prince Pierre Napoleon. Wilfrid de Fonvielle, an elder

brother of Ulric, and I have been friends for nearly forty years. He

was another stormy petrel of the Revolution, both on land and in the air,

being an adventurous balloonist at the siege of Paris—distinguished for

intrepidity and volcanic ardour, and as a barricadist, a journalist, a man

of science, and author of notable books.

The brothers Reclus have both been in peril and prison as

philosophical anarchists. To Elie Reclus, because it had valued

memories for him, I gave a fine copy of the only portrait of Robert Owen

in which that famous social philosopher appeared as a gentleman—an aspect

belonging to him which all other engravings of him missed. Reclus,

in his last letter to me, said:—

"MY

DEAR FRIEND,—I

went to the Congresses of Lausanne and Geneva, where I saw your name in

the hotel Gibbon des Bergues, but not your person. Afterwards I

stayed in Auvergne, and now I must, in three or four days hence, be in

Normandy. If you were here on the 15th, I might still have the joy

of seeing you. My brother Elisée, whom I expect daily from a tour in

the Pyrenees, will be here, and, I daresay, you will soon become friends

together. I write to MM. Bewsdeley and Henry Schmahl, who are

earnest co-operators, announcing to them your visit, and I trust they will

be of some service to you. At the Credit au Travail, rue Baillet 3

(behind St. Germain l'Auxerrois, near to the Rue de Rivoli), the

accountant, Mr. Joseph Gaud, will be apprised of your arrival."

Felix Pyat I never saw, though I was his publisher. He could never

have kept his head upon his shoulders in France, and I incurred the risk

of imprisonment in defending his right to use his head in England by

publishing, in the face of prosecution, his "Letter on Parliament and the

Press."

Martin Nadaud was a Parisian workman who came to England for

security. His intelligence, integrity, and manliness won for him the

esteem of Mazzini. He worked at his trade in England, still giving

his spare time to promoting freedom both in France and Italy. I

found him in 1880 holding a permanent office in the French Parliament

House, of which he was a member, always true to his order—the honest Order

of Industry.

Alexander Herzen, the accomplished Russian who sent the

Kolokol (the Bell) through the dominions of the Czar, had left

Russia for good reasons. We met first at Southampton, where he was

seeking information, which I gave him, where the meeting would take place

in the Isle of Wight between Garibaldi and Mazzini. A greater than

Herzen was Karl Blind, whom I have still the pleasure to count among my

friends. Before he did us the honour to reside in England, now

nearly forty years ago, he had had terrible trials, experiencing casemate

incarceration. Since then his name is known in every nation and in

every literature where the lovers of freedom breathe.

Then there was Dr. Arnold Ruge, of the Frankfort

Parliament, who escaped to us to avoid the fate of Blum, the bookseller,

who was shot. He resided many years in Brighton, and I had the

honour to publish a work which he wrote for me.

The giant Bakounine, who had fled from Russian prisons, was

an oft visitor at Fleet Street.

Heinzen was another Russian propagandist, familiar with the

interior of a fortress, who was a welcome visitor at the Reasoner

office. He afterwards went to America, and was the author of many

determined pamphlets on insurgency, displaying power and originality.

One published in Chicago bore the unpleasant title of "Murder and

Liberty."

Prince Krapotkin is the most accomplished anarchist, save the

Recluses, whom I have known. No one who does not know the prince can

imagine how bright, ardent, wise, and human he is. But the

impression his writings give you is that his many attainments are tempered

by dynamite. Prince Krapotin is familiar with prisons: still he

neither swerves nor fears.

Wilhelm Weitling was a German Communist. His "Gospel of

Poor Sinners" was a book of force and original thought. He said he

learned English from two works of mine ("Practical Grammar" and "Public

Speaking") when first an exile in England. At some expense, I had

his speeches translated and printed in the Movement when he first

spoke in London, and thinking to serve him by enabling him to send copies

to America, where he was going, I presented him with some. He,

however, violently resented the act as a great affront, thinking I assumed

that he had the vanity to diffuse his own speeches. He first taught

me that foreigners were apt to be alien in mind as well as race, until

naturalized by intercourse and knowledge. He came to England with

the reputation of a "dangerous Communist." His liking of prison life

in Germany did not grow by what it fed upon; so he, in 1848, tried London

for a change, being expelled from Switzerland at the instigation of the

German Government. In one of his speeches in our John Street

Institution in London (held by disciples of Robert Owen) he said what was

new then, and is not yet old—that "there will neither be equality nor

justice so long as those who labour are poorer than those who govern."

Wilhelm Weitling was born at Magdeburg in 1808, and died in America in

1871. He was the first after Babœuf who gave to Socialism a fighting

policy, and his proceedings and apostolic advocacy were anxiously watched

by various European Governments. In 1834 he formed the "League of

the Proscribed." This was followed by a "League of the Just," a less

happy and more pretentious

title in the eyes of outsiders. Weitling was the leader of this

League when he came to England. With all his public ardency, he

followed his own industry for subsistence. He came one day to make

my wife a dress, and I remember how surprised she was to be asked to take

off her gown that he might more accurately make the measurement. Men

dressmakers and their German customs were unknown to us. Weitling

edited a journal in 1841 in which he advocated the formation of a

cooperative society. Politics was with him a means to a social end.

Louis Kossuth, the Hungarian leader, acquired more rapidly than Blanc a

wonderful mastery of English, but he never understood, any more than

Garibaldi, our illogical freedom, or the mysteries of our political

constitution. I published a bust of the Magyar orator, made for me

by Signor Bezzi, and cheap editions of Kossuth's speeches. Kossuth

would have been shot on sight had the Austrians got sight of him.

Kossuth's wife, like Garibaldi's Anita, suffered the vicissitudes of war

and flight. Though less inflexible than Mazzini or Blanc, and though

he entered into political relations with the French Usurper, who was not

to be trusted on his word any more than his oath, yet Kossuth gave proof

of integrity when peril menaced him. His generals, Bern and Kemetty,

adopted the Mahomedan faith for the sake of Ottoman protection.

Kossuth bravely refused. Bern, when an exile in England, lived near

me, a little off the Euston Road, and I used to meet him as he walked

where Bolivar had walked before him, on the broad pavement that runs

through Euston Square. Kossuth had studied English in the fortress

of Buda. No orator ever spoke in a foreign tongue with the effect

with which he spoke in England. His ideas were as remarkable as his

manner, and were an addition to our knowledge, as Toulmin Smith and

Professor F. W. Newman testified.

Francis Pulzsky, the Hungarian Prime Minister under the

Kossuth Government, narrowly escaped being shot by the Austrians.

His youngest son, who wore a picturesque Hungarian dress at evening

parties, which well became his handsome face, was a frequent visitor at my

house while a student at the London University. Once or twice I

dined with his father, who showed me six or seven iron-clasped chests,

containing the Royal jewels and the Hungarian crown, which he had with him

in an upper room of his house at Highgate (the second or third house at

the bottom of Swain's Lane). Madame Pulzsky was a remarkably small,

gentle lady, and you wondered that her sons should be men of fine stature.

We conversed at table upon the noble moderation of the French in the

Revolution of 1848, in not executing those who would have executed them

had they been victors. The Usurper who, by the leniency of

Republicans came into power, made short work with the Republicans, and

shot and transported them by thousands. Madame Pulzsky had seen so

many of her friends destroyed that she distrusted the policy of leniency,

and said to me, "Mr. Holyoake, if we come into power again, we will cut

all the throats we spared before!" The energy with which this was said by

so gentle a lady was very impressive. I contented myself by

answering that leniency did fail sometimes, and so did relentlessness, but

I believed that in the long run the cause of liberty gains more by pardon

than by death.

Among leaders of opinion whom I knew who incurred peril in

America, the chief was Lloyd Garrison, who was dragged through Boston

streets with a rope round his neck, and was imprisoned by the mayor to

save him being lynched. In 1879 I had pride in speaking in Stacey

Hall on the platform from which he was pulled down. Mr. Quincy, the

son of the mayor who saved Garrison, was in the chair. Mr. Garrison

lived to find himself honoured in two worlds—in America, and on this

"aged" side of the Atlantic. Lord John Russell spoke at a public

breakfast given to Garrison, and Mr. Bright made the most eloquent of all

the brief speeches I ever heard from him, and read a passage from the New

Testament as I have never heard it read before or since—comparing the

persecutions of Garrison with those of the Apostles. About 1850-2,

he published in the Liberator a letter from Mr.

W. J. Linton

against me. But Lloyd Garrison was incapable of being mean or

unfair, and published a reply from his valued correspondent, Edward

Search. Harriet Martineau was also a reader of the Liberator,

and as soon as she saw the Linton letter she wrote a most generous

vindication of me—which was her custom towards any friend whom she knew to

be unjustly assailed.

Others who were not hanged came, like Garrison, near to it,

and deserve regard when they knowingly took that risk for the service of

the unfriended slave, as Harriet Martineau did when in America. Men

shrank from the peril she incurred, though men were ready to risk their

lives in her defence. To prevent danger to them, she forewent

journeys she contemplated, as her death was arranged for her on her way.

Had the peril been hers alone, she would never have drawn back.

Not less did George Thompson risk death. Of him I heard

Lord Brougham say "he had the most persuasive voice of any orator he ever

listened to." And his competent testimony was confirmed by all who

heard Thompson. On his two first visits to America, speaking for the

slave, he was hunted to be "hanged on a sour apple-tree." On his

third visit he dwelt with my friend, Mr. Seth Hunt, at his home under

Mount Holyoke. He slept in the "Prophet's Chamber," where others in

peril had slept before; and which in happier days I had the honour to

occupy. But were I to mention all my friends who succoured the

hunted and condemned, I must include here certain Englishmen, Colonel

Hinton, of Washington; Mr. W. H. Ashurst; Mr. R. A. Cooper, of Norwich;

Major Evans Bell, and many others. George Thompson afterwards became

M.P. for the Tower Hamlets. Had his personal fortune enabled

him to remain in the House of Commons, he would have become eminent there.

Mr. F. W. Chesson, who continued through another generation the same noble

exertions on behalf of the oppressed and unfriended in many nations,

married Thompson's daughter.

Since Toussaint L'Ouverture, whose tragic story has been written by

Harriet Martineau in "The Hour and the Man," there has been no nobler

champion of the coloured race than Frederic Douglas. He was born

under sentence—the dread sentence of slavery—a doom of lifelong

imprisonment without hope of ending. When wandering homeless at

night about Peoria, no minister would open his doors to the slave (though

Douglas was himself a preacher), when a passenger told him to knock at

Colonel Robert Ingersoll's gate, and he would find shelter and welcome

under the generous heretic's roof. It was in Ingersoll's house that

I spent my first evening with the noble slave, who was then Provost

Marshal of Washington. The colonel produced his choicest champagne

to celebrate the event. It is told in the annals of slavery, that

when Douglas was assailed and hissed on the platform by slave-owners, he

paused, and then said, "Yes, a hiss is what you always hear when the

waters of truth drop on the fires of hell." This saying is also

ascribed to Clay, another orator for the freedom of the slave; but it

shows the quality of Douglas on the platform that the splendid retort

should be related of him.

CHAPTER XX.

ENGLISH AND IRISH AGITATORS WHO GAVE TROUBLE TO JURIES AND JUDGES.

(1840-1890.)

THE reader will observe that some names are

mentioned only incidentally, and others at more length. Some

described here briefly are in other chapters further mentioned.

Another friend whom I knew, bearing a memorable name—Leigh

Hunt—was imprisoned, as all the world knows, for his boldness in reminding

a certain Royal personage that personal morality would be as useful in

those of high as in those of humble station. Leigh Hunt's career was

before my time, but I had the honour to know him in his later years, and

still read with pride a published letter which he addressed to me.

From his earlier years to his closing day, he never swerved from the

perilous principle of saying what he thought right and knew to be useful,

regardless of that cowardly policy of waiting on public opinion until the

right thing can be done safely.

Madame Jessie White Mario was the first distinguished

platform speaker among Englishwomen. When she first spoke on Italian

questions, women had not spoken in public with the view of influencing

State affairs. Madame Mario was more than Miss Nightingale at

Scutari; she went with Garibaldi's expedition and rescued the wounded

under fire. She was imprisoned in Genoa five months in 1857, in

Ferrara where Tasso was incarcerated, and in Rome. As well as aiding

by her intrepid services the cause of Italy, she wrote vindicatory lives

of the distinguished heroes whose names, before all others represent the

unity of that wondrous land. She told me at Lendinara that, should a

war arise between England and Italy, she had become so much Italian that

she could not live and see Italy suffer; yet she was at the same time

English at heart, and could not bear the thought that her native land

should fail. Therefore, should war occur, she should apply at St.

Peter's Gate for some retreat in his dominions. Madame Mario has

published works of authority on the lives of Mazzini, Garibaldi, Dr.

Bertani, and others. It was "To Miss J. Meriton White that Walter

Savage Landor addressed the following letter, which caused great

disquietude in the Tuileries. It first appeared in the Atlas

newspaper under the intrepid editorship of Mr. Henry J. Slack:

"At the present

time I have only One Hundred Pounds of ready money at my disposal, and am

never likely to have so much in future. Of this, I transmit FIVE to

you, towards 'the acquisition of 10,000 Muskets to be given to

the First Italian Province which shall rise.' The remaining £95,

I reserve for the Family of the First Patriot who asserts the dignity and

performs the duty of tyrannicide. Abject men have cried out against

me for my commendation of this Virtue, the highest of which a man is

capable, and now the most imperative. Is it not an absurdity to

remind us that usurpers will rise up afresh? Do not all transgressors? And

must we therefore lay aside the terrors of chastisement, or give a

Ticket of Leave to the most atrocious criminals? Shall the laws be

subverted, and we be told that we act against them, or without their

sanction, when none are left us, and when guided by Eternal justice we

smite down the subvertor? Three or four blows, instantaneous and

simultaneous, may save the world many years of war and degradation.

If it is unsafe to rob a Citizen, shall it be safe to rob a People?"

Before enumerating political advocates in England, insurgent publishers

claim notice who, in a sense, made the advocates what they were, and

created for them their auditors. Foremost among them—greatest, most

determined and impassable of them all—was Richard Carlile, my friend and

adviser at my own trial at Gloucester, and who had himself been imprisoned

nine years and four months. In the "Dictionary of National

Biography," I have written Carlile's life. Acts of defiance of the

evil Governments of his day, in which Carlile persisted, had been visited

by a long term of transportation, as happened to Muir and Palmer. It

was Carlile's intrepid publication of prohibited books which established

the freedom of the press in England.

Next to him, and contemporaneous with him, was Henry

Hetherington. The first time I spoke at a graveside was at Kensal

Green, when Hetherington was buried amid a concourse of 2,000 persons.

The Times said of him that he was one of a band "who were familiar

with the inside of every gaol in the kingdom." Hetherington made no

parade, no defiance, but was immovable. He did for the unstamped

press what Carlile did for Freethought works. A disciple of Robert

Owen, Hetherington was always for reason; but he had the courage of

reason, which he was capable of infusing into others—for 500 persons were

imprisoned for selling his unstamped papers. He defended trades

unions when they were illegal, and had the merit of defining the policy

which co-operative advocates of profit-sharing labour have maintained

since.

James Watson was my first publisher. He was imprisoned

several times for his persistence in publishing prohibited books and

newspapers. Between Watson and Hetherington a remarkable friendship

existed. Both published some earlier works for me, but neither would

publish without understanding that it was consistent with the business

interest of the other that he should do it.

John Cleave incurred imprisonment. He was a rotund,

energetic, Radical publisher, and was the third of the trio of newsvendors

whose names were known in every town and village in the three

kingdoms—"Hetherington, Watson, and Cleave." Henry Vincent married

Cleave's daughter. Cleave did not give others an impression that he

had a passion for risk; but Watson and Hetherington, whenever peril came

to others which they ought to share, placed themselves at once in the

front rank of jeopardy.

Abel Heywood, in earlier years, published a work for me.

The name of Heywood in the provinces was as famous as that of Hetherington

in London. Heywood was imprisoned for the sale of unstamped

publications. He was afterwards Mayor of Manchester, and the Queen

was dissuaded from visiting the city during his mayoralty as she intended,

by those who resented his steadfast and honourable defence of public

liberty: though, had her Majesty known it, it was a reason why she should

have done honour to a mayoralty held by one whose services reflected

distinction on her reign.

One of my earliest friends in Birmingham was John Collins, a

Birmingham local preacher, whose hand I held as a boy when we walked

together to Harborne, a village four miles from Birmingham, where he went

to preach on a Sunday, and I to teach in the Sunday School the little I

knew. He was imprisoned two years in Warwick Gaol for making

speeches on behalf of Chartism.

Another friend of mine, at whose grave I afterwards spoke,

was William Lovett. He was imprisoned also two years at the same

time as Collins, and in the same gaol. They were both what was known

in their days as "Moral Force" Chartists, in contradistinction to

"Physical Force" agitators. In those days there was only a

middle-class suffrage, composed (as W. J. Fox said in the House of

Commons) of the "Worshipful Company of Ten-pound Householders."

Moral force was before its time then. Now the people have a free

vote, a free platform, a free press, and the ballot-box—if they cannot get

what they want without physical force, they do not understand their

business. Lovett and Collins composed in prison, and afterwards

published, a well-thought-out scheme for the political education of

working-class politicians. Collins, like Attwood, Salt, and

O'Connor, died from failure of mental power. It was a justification

of those who sought redress by violence that, avoiding it and advocating

moral force alone, they should be condemned to imprisonment all the same.

|

|

|

Thomas Cooper

(1805-92) |

"Thomas Cooper, the Chartist," as he proudly wrote on the

title-page of his remarkable poem "The Purgatory of Suicides," was

imprisoned two years in Stafford Gaol. During fifty years over which

our friendship has extended, there has been change of conviction in him,

but never of honest principle. Mr. Cooper preceded and exceeded

Lovett and Collins in the political instruction of the people, and had

himself a passion for self-education which has made his name eminent by

his attainments. His name is in all booksellers' catalogues, and his

praise is in all the churches. Poems, novels, essays, sermons, are

departments of literature in which he has been distinguished.

Henry Vincent appeared among us in John Frost's days. I

have the sword which Frost wore when he commenced his ill-fated

insurrection in Newport. It was taken from him by Colonel Napier.

Vincent was an ardent, inflammatory orator, who said as much against

Christianity as against political oppression. All the while he was a

Christian at heart, and, like Thomas Cooper, a greater advocate than he

was a heretic—being a heretic from indignation rather than from

intellectual conviction. Vincent's imprisonment was in Monmouth

Gaol. He afterwards was an occasional preacher in Liberal Dissenting

churches, but, like all men who have been for a time on the other side, he

never returned again to the dark valley of unseeing faith, but dwelt on

the hills of orthodoxy, where some light of reason falls. He

ultimately acquired a cultivated style of oratory, and became a celebrated

lecturer both in England and America. His orations, for the quality

of his speeches entitled them to that term, were mainly expositions of

political principles. He married, as has been said, the daughter of

John Cleave.

|

|

Ernest Jones

(1819-69) |

Ernest Jones was notable alike for impassioned oratory and poetic

inspiration. By birth, culture, and sacrifice, he lent distinction

to the Chartist cause he espoused. Thomas Carlyle went to see him

through the bars of the prison where he was confined two years. We

never knew whether Jones was Hanoverian or English by birth, but he was

always English in his advocacy and sympathies. Carlyle had no

discernment that he was a man of genius who had resigned affluent

prospects for penury and principles, and who, in great vicissitude, never

turned back. The only time I ever spoke on Nelson's Monument in

Trafalgar Square was in commemoration of his premature death.

Joseph Rayner Stephens, the greatest orator on the Chartist

side, was imprisoned in York Castle. Stephens was a Tory, not of the

baser sort who seek personal power for purposes of political supremacy,

but of the nobler kind who desire to see power in the hands of the wise

(which they take themselves to be) for the improvement of the condition

and the better contentment of the people. Stephens was for the

Crown, but he was for the people, come what might of the Crown. On

the platform he was a master of assemblies. In conversation he

excelled all men I have known. He saw all that was in the words he

used and all round the subject upon which he spoke. His easy

precision resembled that of Lord Westbury. Stephens did vehemently

teach armed resistance, not against public order, but against public

wrong. The Government did not see the distinction—no wonder the

people did not.

I had but limited acquaintanceship with Richard Oastler,

although great admiration for his personal character. In spite of

his Toryism, I had a regard for him, on account of his humanity and real

interest in the welfare of factory children. I first knew him when

visiting George White at Queen's Bench Prison, where Mr. Oastler was also

confined. Like Joseph Rayner Stephens, his great colleague, he cared

for throne and factory children, but for children first and children most.

William Prouting Roberts, whom we called the "Miners'

Attorney-General," was one who incurred six months' imprisonment at

Devizes for his defence of labour. He was the terror of many a local

Bench, and defended many a miner and weaver who otherwise had had no

redress or deliverance.

The most volcanic voice in the Chartist movement was that of

G. J. Mantle. When I was with Mr. J. S. Mill at the Agricultural

Hall, Islington, in the Hyde-Park-railing days, Mill could not be heard

far into the vast valley of people there assembled; the outer concourse

was lost in the deep shadows of the great hall which two fierce lights on

the platform deepened. Then Mantle was chosen to read the

resolutions to be passed. His sentences seemed shot from a culverin.

His throat opened like the mouth of a tunnel. No doubt the jury

heard his defence long before (1839-40), when he was accorded two years'

imprisonment for speeches made to Hyde Park Chartists. The judge

embellished his sentence by a few graceful words (common among judges, who

are never political), saying—"It was you who made seditious speeches, and

were a party to the conspiracy and riot. It is true you were not at

the latter in body, but your spirit was there; you sounded the trumpet,

but you were not in the van, and it is always so with people like you.

You are a young man with a very voluble tongue and an empty head, as most

mob orators are. I advise you to study more and speak less—to know,

if you can be made to know, that a boy of twenty-two is not the person to

alter, the constitution of this country."

|

|

|

(1817-97) |

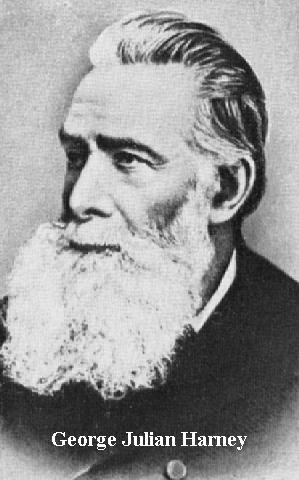

George Julian Harney was early in prison. He was in the heart of the

Chartist movement, and always a picturesque figure in it. His

fervour of speech and his ubiquitous activity made him widely known and

popular. It was long hoped he would be the historian of the

movement, of which he knew more than any other leader. His first

wife, who died early, came from Mauchline. She was tall, beautiful,

and of high spirit, a brave counsellor in all risks and a resolute sharer

of any consequences. Harney was worthy of the heroic companionship

it was his good fortune to possess. His last publication in England

was the Red Republican, a title which admitted of no mistake,

and he was the first Chartist who adopted Louis Blanc's motto—"The

Republic, Democratic and Social."

James, afterwards Alderman, Williams, of Sunderland, was a

bookseller, printer, and publicist, and one of the few Chartist agitators

in those ardent days who thought that political passion was the better for

being controlled by good sense. At Durham Assizes he was sentenced

to six months' imprisonment. He defended himself. The jury had

recommended leniency on the ground of his being a young man.

Williams said he claimed no consideration on that ground, as what he had

done was the result of calm deliberation. He only claimed

consideration on the ground of the utility of his public conduct.

Williams was counted too intellectual in his advocacy, and fell below the

level of orators of passion; but at the bar he was in respect of courage

far above most of the men of passion, who, like O'Connor and some others,

denied what they had said.

Irish leaders of English political agitation were daring,

eloquent, inspiring, impetuous, and dangerous—dangerous because they were

impatient, and impatient here because, despairing in their own land, they

naturally incited insurgency here which might lead to liberty in Ireland.

Feargus O'Connor, a man more powerfully built than O'Connell,

whom he succeeded as a political advocate in England, was imprisoned for

two years in York Castle. O'Connor was the most impetuous and most

patient of all the tribunes who ever led the English Chartists. In

the Northern Star he let every rival speak, and had the grand

strength of indifference to what any one said against him in his own

columns. Logic was not his strong point, and he had colossal

incoherence.

Thomas Ainge Devyr, an energetic and fertile Irish leader of

English Chartism, would have been imprisoned a long time by Lord Abinger

had he not fled to America. His bail was estreated in his absence.

He was the earliest of the advocates of land and landlord reform in

Ireland, and claimed, with some truth, to be the originator of the land

theories that afterwards became famous. The Northern Liberator,

edited by him before his flight from Newcastle-on-Tyne to America, was the

most readable of all the insurgent newspapers of that period.

James Bronterre O'Brien, who excelled all the Chartist

leaders in passion of speech and invective, was sentenced to nine months'

imprisonment at the Liverpool Assizes. He was the only Chartist who

comprehended fully how large a share, social, financial, and commercial,

error contributes to the suffering of the people.

For George White I had as much regard as for any Irish leader

among the Chartists. He was so frank, generous, and brave.

Whenever the early Socialists were in trouble with their theological

adversaries, White would bring up his "Old Guard" and man the hall during

a debate to see fair play. In one case in Birmingham they attended

five nights, at Beardsworth Repository, from seven to eleven o'clock.

Though poor men, they paid for their own admission. He said to me

that whenever I was in any danger of ill-usage on the platform I was to

send him word and he would bring up the "Old Guard." This he never

failed to do. When he was imprisoned in London, my wife used to make

pies for him and take them to him at the Queen's Bench. They were

very welcome to him, as he always had a precarious revenue. He died

ultimately in the Infirmary in Sheffield, I have no doubt dreaming of pies

to come, for he was very desolate. He was the personification of

energy, physical and mental, possessing a vigorous frame and bright eyes,

with a ready, trenchant speech which had the prance of the war-horse in

it, neighing for battle. Like other Chartists, he took money from

the Tories, the better to enable him to destroy the Whigs, whom he

distrusted—because they went tardily on the way of redress. He

opposed the Whigs more than he did the Tories, who never set out that way

at all. The father of Lord Cranbrook (it was said by Bradford

colleagues), partly from kindness to White, and otherwise for his

political services, allowed him many years a small stipend—besides special

aid when Anti-Corn Law League meetings required to be broken up.

CHAPTER XXI.

A FURTHER CALENDAR OF FRIENDS WHOSE FATE NEEDS EXPLANATION.

(1840-1890.)

AMONG the following inhabitants of the prison-house

are valued friends and colleagues of my own. Others I knew and had

certain relations with, but without approving or condoning what they had

done. One whom I was bound by ties of friendship to save if I could,

sent me a petition to sign, as I was known to the Minister to whom it was

addressed. But I declined, as the plea drawn up by the petitioner

justified his act. I did not agree with the justification, and could

not ask a minister to condone an offence which a jury had recognized as

harmful to the secular interests of the public. At the same time I

drew up another petition asking for mitigation of sentence on other

grounds which could fairly be pleaded.

Mr. Charles Southwell had been out with Sir de Lacy Evans in

the Spanish expedition. He was imprisoned in 1840 for twelve months,

in Bristol Gaol, for an article in the Oracle of Reason, entitled

the "Jew Book." He was sentenced by Sir Charles Wetherell, the "Old

Bags" of Hone. I took the vacant editorship and came to a similar

end. Mr. Southwell was the youngest of thirty-six children, and was

the liveliest of them all. In this he resembled Bishop Bathurst, who

was one of thirty-six children by the same father; but Charles Southwell

resembled the bishop in no other particular. Mr. Southwell was for

some time upon the stage, and was a good actor. He was, like myself,

a social missionary lecturing upon Mr. Owen's system of society. He

had great versatility—infinite animation, chivalry, and daring. When

Bishop Philpotts intimidated two social missionaries into taking the oath

as licensed preachers to avoid certain disabilities, I and Charles

Southwell protested against and refused to swear to the thing which was

not. On one occasion he undertook to deliver a lecture for the

benefit of prisoners in Edinburgh, in the interests of the

Anti-Persecution Union. He did lecture, and for an hour and a half a

large audience was delighted with his wit, vivacity, and discursiveness.

At the conclusion of his address, I said, "Why, Southwell, you never

mentioned the subject of your lecture!" He answered, "Well, I quite

forgot it." So did we all while he was speaking. He died in

Auckland, New Zealand; but though he had ceased to advocate his

principles, he maintained them in his death.

George Adams was imprisoned in Gloucester Gaol for publishing

the Oracle of Reason from friendship for me. Mrs.

Harriet Adams, his wife, was also imprisoned for like cause. She was

handsome, intelligent, and of invincible spirit. Both died at

Watertown, in America.

Miss Matilda Roalfe, at a time when persecution in Edinburgh

prevailed, went from London to conduct a small publishing business, though

the previous owner of the shop was imprisoned. She also was

sentenced to be imprisoned sixty days (1843) for the publication of

prohibited Freethought works. She was confined in an unclean cell,

and her life was imperilled by religious tumult on her release on bail.

On her trial she cross-examined the witness with good judgment. She

was told that if she pleaded she was unaware of the nature of the books

she sold she might escape. This she would not do. She was

instructed by her legal friends that there were serious legal flaws in the

proceedings against her. She declined to seek escape on technical

grounds, but stood on the right of freedom of the press in honest

criticism and speculation. She was as remarkable for quiet courage

as for good sense. She made no complaint and no submission.

She afterwards became the wife of a valued friend of mine, who, next to my

brother Austin, was my most trusted assistant at the Fleet Street house.

Mrs. Emma Martin was another lady distinguished in her

day as a platform speaker on questions of social reform, at whose grave I

spoke. She suffered brief imprisonments. She was a handsome

woman, of brilliant talent and courage.

Thomas Finlay was a man of sixty years of age when I first

knew him. He was of good presence, intelligence, and devotion to

principle. He made a case with a glass frame and placed in it a copy

of the Bible in large type, open at a part which he thought unfit to be

found in a sacred book, and placed it where it could be read by passers-by

in a main street in Edinburgh. For this he was imprisoned and the

Bible also. I have the copy which was sent to me, bearing the

imprimatur of the Procurator-Fiscal certifying its legal detention for

blasphemy. Finlay defended himself in a speech of considerable

length, but was sentenced to six months' imprisonment. He had a

daughter married to Mr. Henry Robinson, of Edinburgh, who was agent for

works I published. He also was imprisoned by the Edinburgh

authorities.

Thomas Pooley, the Cornish well-sinker, whom I aided in

rescuing from twenty-one months' imprisonment, was an honest, indomitable,

incoherent man, whose career the reader may see described in another

chapter.

Thomas Paterson was a young Scotchman who also went out with

Sir de Lacy Evans in the Spanish expedition, to which Southwell also

belonged, but they were unknown to each other at that time. They

were afterwards colleagues in the defence of free opinion and underwent

similar imprisonment. Paterson's chief imprisonment was in Scotland,

where he went as a volunteer during the Edinburgh prosecutions, being

imprisoned fifteen months in 1843. While I was a stationed lecturer

in Sheffield he lived in my house nine months, and was known as my

"curate," as I engaged him to assist me in the schools conducted in

connection with my lectureship at the Rockingham Street Hall. No

danger and no imprisonment intimidated Paterson. In any project of

peril in which I was concerned, he was always a volunteer. For this

reason I remained his friend until his death, which brought me trouble, as

Paterson published attacks on friends of mine from which I entirely

dissented. This he did without my knowing it, but as my friendliness

with him was known, I was considered as concurring in his opinion, and

thus I lost friends.

Mr. G. W. Foote was imprisoned for publishing Biblical

caricatures not worse than the caricatures which theological adversaries

deal in without reproach, and, indeed, with popular approval. Mr.

Ramsay, an intelligent and hard-working propagandist, was imprisoned in

like manner for selling them. I did what I could to induce Sir Wm.

Harcourt to release them on the grounds that, were they chargeable with

misplaced ridicule, the consequences fell upon their cause, and it was no

business of the State to protect Freethinkers from the excess of their

own enthusiasm, and that, since Christians were allowed unbridled license

to ridicule their adversaries, and did it, both parties should be

imprisoned, or neither.

The most unjust of all prosecutions of the kind was that of

Edward Truelove, a man not only of blameless, but honourable life, who had

been a bookseller and publisher for nearly half a century. He was

imprisoned four months for selling Robert Dale Owen's little work on

"Physiology in Relation to Morals"—the most ascetic, reasonably-written of

all pamphlets on the limitation of families that have been published for

forty years. The sensuality is all on the side of those who object

to the principle of such works. Mr. Truelove, though of advanced

age, bravely refused to compromise the right of free publication of

opinion, and sustained the traditions of the school of Carlile, Watson,

and Hetherington.

Mr. J. B. Langley was a publicist with whom I was associated

for more than thirty years. He had the passion of public service,

and, like all who have it, he neglected his own interest to advance it.

He was imprisoned for the violation of an Act never put in force before,

and which, if honestly put in operation, would imprison hundreds of

persons in the city of London who are counted of good commercial fame, and

who would share the same fate. Mr. John Bright and Mr. Samuel Morley

contributed to a fund to enable Mr. Langley to go to the coast for a time

when free, he having many friends who knew how a forlorn hope or

struggling cause could always command his services day or night, near or

far. Indeed, it had been better for him had he given more time to

his own business and less to the public cause. Mr. Langley was one

of the minor poets, as well as a ready public speaker.

Mr. Swindlehurst, a very hard worker for social improvement,

was imprisoned in like manner from a like cause.

Robert Southey, who was hanged at Maidstone, was not one of

my friends, but I was an adviser of his, and endeavoured to assist him.

He killed seven persons, and was very deservedly executed. I have

known many who earned the gallows in their effort to obtain notoriety, but

Southey was the only one who chose it for that purpose.

Gerald Supple, named elsewhere, a journalistic colleague, was

sentenced to be hanged for shooting two persons and killing the wrong one.

He had ability, chivalry, and courage worthy of his country. He came

from Dublin.

Rudolph Herzel was a tall, thoughtful-looking secretary to a

Secular Society at Leeds. Ardent, intelligent, enthusiastic,

devoted, always ready to go to the front, he offered himself to me to

serve on any forlorn hope, in conspiracy or battle. I declined to

dispose of any man's life, and did no more on his request than inform him

where conflict was impending, but the choice of entering upon it must be

his own. He afterwards went out during the Italian war, and was no

more heard of by me.

One whom I do not name, but who had many claims on my regard,

got involved in the unwise defence of some persons, unknown to me, in

serious railway robberies. I have no doubt he acted from some

mistaken sense of justice, and wrote a letter intimidatory of the

authorities who were investigating the robberies, with which he could not

possibly have been concerned. One morning I saw in The Times

a lithographed letter with an offer of £300 reward for discovery of the

writer. I knew at a glance who he was and remonstrated with him.

He wrote, with a fearless defiance natural to him, saying, he knew I

needed money, and that I was quite at liberty to give information as to

the authorship of the letter, and he not only should not reproach me, but

be glad if he could be of service to me. My answer was that I never

took blood-money, especially that of one I had treated as a friend.

He was imprisoned several times subsequently, but never on that or any

similar account, and sometimes from causes creditable to him. A

curious thing occurred in connection with the letter referred to.

Having to go to Scotland I took his self-inculpating letter and a copy of

The Times containing the lithograph letter with me, intending to

give both to him. I never removed them from my trunk. Some

days after my arrival at my destination I sought them, but they, alas!

were not there. In what way they could have been abstracted or lost

I never could make out. My anxiety lest they had fallen into

dangerous hands was very great. What became of them I never knew.

Fortunately nothing resulted from their loss.

Now, I have fulfilled my promise to justify my assertion that

I have had so many questionable friends that the reader might feel

reasonable alarm at continuing the perusal of these pages. In this

and the two preceding chapters I have enumerated sixty-eight persons in

whom the State took personal interest. In enumerating those who were

hanged, I have said nothing of others who, in the opinion of confident, if

not competent observers, ought to have ended that way. But every man

who had knowledge of public affairs knows a great number of these also.

I have confined myself, with one or two exceptions, to those who nobly

incurred peril. In my memory are many more whom, perhaps, I ought to

mention; but I have cited enough to prove my intimation that I am a person

of suspicious acquaintances. But it is a good rule in autobiography,

as in debate, to state your case, clear your case, prove your case, and

then cease. To do more is to weary the reader, and that is the prime

crime a writer can commit.

CHAPTER XXII.

THE FOUNDER OF SOCIAL IDEAS IN ENGLAND.

(1841-1858.)

HAVING been for more than half a century concerned

in the advocacy of Robert Owen's "New Views of Society," which attracted a

band of adherents when first announced, I think it is relevant that I

should give some account of this class of social ideas.

Just as Thomas Paine was the founder of political ideas among

the people of England, Robert Owen was also the founder of social ideas

among them. He who first conceives a new idea has merit and

distinction; but he is the founder of it who puts it into the minds of men

by proving its practicability. Mr. Owen did this at New Lanark, and

convinced numerous persons that the improvement of society was possible by

wise material means. There were social ideas in England before the

days of Owen, as there were political ideas before the days of Paine; but

Owen gave social ideas form and force. His passion was the

organization of labour, and to cover the land with self-supporting cities

of industry, in which well-devised material condition should render

ethical life possible, in which labour should be, as far as possible, done

by machinery, and education, recreation, and competence should be enjoyed

by all. Instead of communities working for the world, they should

work for themselves, and keep in their own hands the fruit of their

labour; and commerce should be an exchange of surplus wealth, and not a

necessity of existence. All this Owen believed to be practicable.

At New Lanark he virtually or indirectly supplied to his workpeople, with

splendid munificence and practical judgment, all the conditions which gave

dignity to labour. Excepting by Godin of Guise, no workmen have ever

been so well treated, instructed, and cared for as at New Lanark.

Co-operation as a form of social amelioration and of profit

existed in an intermittent way before New Lanark; but it was the

advantages of the stores Owen incited that was the beginning of

working-class co-operation. His followers intended the store to be a

means of raising the industrious class, but many think of it now merely as

a means of serving themselves. Still, the nobler portion are true to

the earlier ideal of dividing profits in store and workshop, of rendering

the members self-helping, intelligent, honest, and generous, and abating,

if not superseding competition and meanness.

During all the discussions upon Mr. Owen's views, I do not

remember notice being taken of Thomas Holcroft, the actor, who might have

been cited as a precursor of Mr. Owen. Holcroft, mostly self-taught,

familiar with hardship, vicissitude, and adventure, became an author,

actor, and playwriter of distinction. He expressed views of

remarkable similarity to those of Owen. Holcroft was a friend of

political and moral improvement, but he wished it to be gradual and

rational, because he believed no other could be effectual. He

deplored all provocation and invective. All that he wished was the

free and dispassionate discussion of the great principles relating to

human happiness, trusting to the power of reason to make itself heard, not

doubting the result. He believed the truth had a natural superiority

over error, if truth could only be stated; that if once discovered it

must, being left to itself, soon spread and triumph. "Men," he said,

"do not become what by nature they are meant to be, but what society makes

them."

Actors, apart from their profession, are mostly idealess; and

the few who are capable of interest in human affairs outside the stage,

are mostly so timid of their popularity that they are acquiescent, often

subservient, to conventional ideas. Not so Holcroft. When it

was dangerous to have independent theological or social opinions, he was

as bold as Owen at a later day. He did not conceal that he was a

Necessarian. He was one of a few moralists who took a chapel in

Margaret Street, Cavendish Square, with a view to found an Ethical Church.

One of his sayings was this: "The only enemy I encounter is error, and

that with no weapon but words. My constant theme has been, 'Let

error be taught, not whipped.'" Owen but put this philosophy into a

system, and based public agitation upon the Holcroft principle.

Owen's habit of mind and principle are there expressed. Lord

Brougham, in his famous address to the Glasgow University in 1825,

declared the same principle when he said no man was any more answerable

for his belief than for the height of his stature or the colour of his

hair. Brougham, being a life-long friend of Owen, had often heard

this from him. Holcroft was born 1745, died 1809.

Robert Owen was a remarkable instance of a man at once Tory

and revolutionary. He held with the government of the few, but,

being a philanthropist, he meant that the government of the few should be

the government of the good. It cannot be said that he, like Burke,

was incapable of conceiving the existence of good social arrangements

apart from kings and courts. It may be said that he never thought

upon the subject. He found power in their hands, and he went to them

to exercise it in the interests of his "system." He was conservative

as respected their power, but conservative of nothing else. He would

revolutionize both religion and society—indeed, clear the world out of the

way—to make room for his "new views." He visited the chief courts of

Europe. Because nothing immediately came of it, it was said he was

not believed in. But there is evidence that he was believed in.

He was listened to because he proposed that crowned heads should introduce

his system into their states, urging that it would ensure contentment and

material comfort among their people, and by giving rulers the control and

patronage of social life, would secure them in their dignity.

Owen's fine temper was owing to his principle. He

always thought of the unseen chain which links every man to his destiny.

His fine manners were owing to natural self-possession and to his

observation. When a youth behind Mr. McGuffog's counter at Stamford,

the chief draper's shop in the town, he "watched the manners and studied

the characters of the nobility when they were under the least restraint."

It ever fell to me to entertain many eminent men, even by accident; but

the first was Robert Owen. His object was to meet a professor and

some young students at the London University. Two of them were Mr.

Percy Greg and Mr. Michael Foster, both of whom afterwards became eminent.

There were some publicists present, and Mr. W. J. Birch, author of the

"Philosophy and Religion of Shakspeare," all good conversationalists.

Mr. Owen was the best talker of the party. Perhaps it was that they

deferred to him, or submitted to him, because of his age and public

career; but he displayed more variety and vivacity than they. He

spoke naturally as one who had authority. But his courtesy was never

suspended by his earnestness. Owen, being a Welshman, had all the

fervour and pertinacity, without the impetuosity of his race. Though

he had made his own fortune by insight and energy, his fine manners came

by instinct. He was successively a draper's counterman, a clerk, a

manager, a trader and manufacturer; but he kept himself free from the

hurry and unrest of manner which the eagerness of gain and the solicitude

of loss, impart to the commercial class, and which mark the difference

between their manners and those of gentlemen. There are both sorts

in the House of Commons. As a rule, you know on sight the members

who have made their own fortunes. If you accost them, they are apt

to start as though they were arrested. An interview is an

encroachment. They do not conceal that they are thinking of their

time as they answer you. They look at their minutes as though they

were loans, and only part with them if they are likely to bear interest.

There are business men in Parliament who are born with the instinct of

progress without hurry. But they are the exception.

A gentleman has no master, and is neither driven nor hurries

as though he had some one to obey. Mr. Owen had this charm of

repose. He had a clear and abiding conception that men had no

substantial interest in being base; and that when they were base, it was

an intrinsic misfortune arising from inherited tendency, or acquired from

contact with untoward circumstances. This belief made him patient

with dishonesty; but dishonesty never blinded him nor imposed upon him.

He could see as far into a rogue as any man. His theory of the

influences of heredity and circumstances gave him a key to character.

Miss Martineau had frequent visits from Mr. Owen, who, she said, "always

interested her by his candour and cheerfulness. His benevolence and

charming manners would make him the most popular man in England if he

could but distinguish between assertion and argument, and refrain from

wearying his friends with his monotonous doctrine." It is a

peculiarity in some Welshmen that, if refuted in argument and they admit

the refutation to be conclusive, their previous conviction returns to

them, and they reassert it as though it had never been answered. I

observed this in Welshmen in America, where there is no market for

abandoned ideas, and no time for returning to errors. Mr. Owen had

this recurrency of anterior ideas, but in him it seemed earnestness rather

than mere iteration. Besides, it was consistency in him, seeing that

he never thought confutation of his views possible, and never met with it.

Because he insisted on these far-reaching principles, which

were sufficient to recast the social policy of the nation, he was

described disparagingly as "a man of one idea." I never shared this

objection to persons of one idea, having known so many who had none.

Many people have but fragments of ideas, and no complete conception of

any.

Mr. Owen's fault was that he repeated his great idea in the

same words. It is variety of statement of the same thing—if there be

truth in it—which conquers conviction.

CHAPTER XXIII.

FURTHER CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PHILOSOPHER OF NEW LANARK.

(1841-1858.)

Mr. OWEN'S sense of fame lay in his ideas.

They formed a world in which he dwelt, and he thought others who saw them

would be as enchanted as he was. But others did not see them, and he

took no adequate means to enable them to see them. James Mill and

Francis Place revised his famous "Essays on the Formation of Character,"

of which he sent a copy to the first Napoleon. Mr. Owen published

nothing else so striking or vigorous. Yet he could speak on the

platform impressively and with a dignity and force which commanded the

admiration of cultivated adversaries.

Like Turner, Owen had an earlier and a later manner.

His memoirs—never completed—were written apparently when Robert Fulton's

death was recent. They have incident, historic surprises, and the

charm of genuine autobiography; but when he wrote of his principles, he

lacked altogether Cobbett's faculty of "talking with the pen," which is

the source of literary engagingness. It was said of Montaigne that

"his sentences were vascular and alive, and if you pricked them they

bled." If you pricked Mr. Owen's, when he wrote on his "System," you

lost your needle in the wool. He had the altruistic fervour as

strongly as Comte, but Owen was without the artistic instinct of style,

which sees an inapt word as a false tint in a picture or as an error in

drawing.

His "Lectures on Marriage" he permitted to be printed in a

note-taker's unskilful terms, and did not correct them, which subjected

him and his adherents also to misapprehension. Everybody knows that

love must always be free, and, if left to take its own course, is

generally ready to accept the responsibility of its choice. People

will put up with the ills they bring upon themselves, but will resent

happiness proposed by others; just as a nation will be more content with

the bad government of their own contriving than they will be under better

laws imposed upon them by foreigners. Polygamous relations are

inconsistent with delicacy or refinement. Miscellaneousness and love

are incompatible terms. Love is an absolute preference. Mr.

Owen regarded affection as essential to chastity; but his deprecation of

priestly marriages set many against marriage itself. This was owing

more to the newness of his doctrine in those days, which led to

misconception on the part of some, and was wilfully perverted by others.

He claimed for the poor facilities of divorce equal to those accorded to

the rich. To some extent this has been conceded by law, which has

tended to increase marriage by rendering it less a terror. The new

liberty produced license, as all new liberty does; yet the license is not

chargeable upon the liberty, nor upon those who advocated it: but upon the

reaction from unlimited bondage.

Owen's philanthropy was owing to his principles.

Whether wealth is acquired by chance or fraud—as a good deal of wealth

is—or owing to inheritance without merit, or to greater capacity than

other men have, it is alike the gift of destiny, and Mr. Owen held that

those less fortunate should be assisted to improvement in their condition

by the favourites of fate. Seeing that every man would be better

than he is were his condition in life devised for his betterment, Owen's

advice was not to hate men, but to change the system which makes them what

they are or keeps them from moral advancement. For these reasons he

was against all attempts at improvement by violence. Force was not

reformation. In his mind reason and better social arrangements were

the only remedy.

In the autumn of 1845 I sent to Mr. Owen (he being then in

America) a copy of my first book on his social philosophy, and the method

of stating it on the platform. It was entitled "Rationalism,"

treated from an Individualist point of view. Mr. Owen's party were

then known as "Rational Religionists." Solicitous of the opinion of

the master, I asked him, in case he approved of it, to please to tell me

so, and permit me to say so. In 1848, he being again in England, I

sent him a further copy, as possibly the other never reached him. He

kindly answered as follows:

"COX'S HOTEL,

JERMYN STREET,

"March 18, 1848.

"MY

DEAR SIR,

-Many thanks for your note, papers, and book, which came here last night

only, although your note is dated 3rd inst. I am just now

overwhelmed with most important public business, which will more than

occupy every moment of my time until I return from Paris. As soon as

I shall have leisure for both reading and study, I will attend to your

'Rationalism,' and give my opinion of it.

"Yours, my dear sir,

"Very truly and affectionately,

"ROBT. OWEN.

"P.S.—Keep up the type of the first 500 copies" [alluding

to a work I was printing for him].

Always intent on the diffusion of his views, I conclude he never found

time to give me the opinion I sought.

In another letter he had told me that Mr. Cobden had

presented to Parliament a petition from him. I do not possess any

letter in which he referred to the opinion he promised to give me; but I

inferred from his continued friendship that he did not much dissent from

what I had said in "Rationalism," or he would have made time to do so; for

when, in a proof of an article I had sent him (he contributed several to

the Reasoner I was then editing), his sharp eye detected the words

"misery, producing circumstances," he desired me to tell the printer to

remove the comma and put a hyphen in its place, that it might read

"misery-producing circumstances." On one occasion he held £10 scrip

in the Fleet Street house.

In 1847, Mr. Owen was a candidate for the representation of

Marylebone. The principles he offered to advocate are notable

to-day, as showing how well he understood the political needs of the

nation, and how much he was in advance of his times:—

-

A graduated property tax equal to the national

expenditure.

-

The abolition of all other taxes.

-

No taxation without representation.

-

Free trade with all the world.

-

National education for all who desire it.

-

National beneficial employment for all who require it.

-

Full and complete freedom of religion under every name by

which men may call themselves.

-

A national circulating medium, under the supervision and

control of Parliament, that could be increased or diminished as wealth

for circulation increased or diminished; and that should be, by its

ample security, unchangeable in its value.

-

National military training for all male children in

schools, that the country may be protected against foreign invasion,

without the present heavy permanent military expenditure.

Mr. Owen was afterwards a candidate for the City of London. I, being

a freeman, was one of his nominators, and attended at the Guildhall, at

his request, to propose or second him on the day of election.

For many weeks I published an advertisement of the

commencement of the Millennium in 1855. This I continued at his

request until March 25th. But up to quarter day no sign of it

appeared. I received payment for the advertisement in the

Reasoner, which, had I believed the Millennium was so near, I should

not have taken.

CHAPTER XXIV.

THE OWEN FAMILY.

Mr. OWEN had three sons who had distinction in their

day. One was employed by the United States Government on geological

survey of territories, another fought in the war of the Rebellion, and

died by injudiciously tasting embalming water, brought to him for

analysis. Robert Dale, his eldest son, came to be United States

Minister at Naples, and delighted King Bomba with spiritual seances

until Garibaldi swept the tyrant and the spirits away. The

minister's daughter Rosamond became Mrs. Oliphant—a bright young

lady who wrote a singularly wise pamphlet on the Rights of Women.

|

|

|

Robert Dale Owen

(1801-77) |

American papers, who best knew the facts concerning Robert Dale Owen,

explained that for a period before his death he suffered from excitement

of the brain, ascribed to overwork in his youth. He was, from his

youth upward, a man of absolute moral courage, and to the end of his days

he maintained the reputation of it. As soon as he was deceived by

the Spiritist, Katie King, he published a card and said so, and warned

people not to believe what he had said about that fascinating impostor.

A man of less courage would have said nothing, in the hope that the public

would the sooner forget it. It is clear now, that spiritism did not

affect his mind; his mind was affected before he presented gold rings to

feminine spirits. Towards the end of his days he fancied himself the

Marquis of Breadalbane, and proposed coming over to Scotland to take

possession of his estates. He had a great scheme for recasting the

art of war by raising armies of gentlemen only, and proposed himself to go

to the then raging East and settle things there on a very superior plan.

He believed himself in possession of extraordinary powers of riding and

fighting, and had a number of amusing illusions. But he was not a

common madman; he was mad like a philosopher—he had a picturesque

insanity. After he had charmed his friends by his odd speculations,

he would spend a few days in analyzing them, and wondering how they arose

in his mind. He very coolly and skilfully dissected his own crazes.

The activity of the brain had become at times incontrollable; still his

was a very superior kind of aberration. In politics, Robert Dale

Owen was not a force so much as an ornament, and never fulfilled the

promise of his youth in being a leader of men. In his Freethought

writings he excelled all his contemporaries in finish of expression.

CHAPTER XXV.

THE MYSTERIOUS PARCEL LEFT AT THE “MANCHESTER GUARDIAN" OFFICE.

(1841.)

WHEN a book was issued some years ago in London, in

defence of small families, it bore a disagreeable title, and I suggested

to the author that "Elements of Social Science" would be a better one,

which he adopted. Afterwards Prof. Newman pointed out in his

discerning way, in letters to the Reasoner, that the author's

doctrine included a principle which would lead to evil: as it implied that

seduction might be a physiological necessity. The merciful aim of

the work was so far frustrated by its execution. To any similar work

the objection made by me related solely to its expression. This I

made clear in the book "John Stuart Mill, as the Working Classes knew

him." On a question such as family limitation, delicacy of phrase

and purity of taste are everything. They are themselves safeguards

of morality. Foolishness of thought, coarseness of illustration,

deter from acts of the highest prudence and repel instead of attracting

serious attention.

Nations, as well as persons, are on some subjects

comparatively without the sense of taste. Joseph Barker, whom many

readers know, was entirely deficient in it. In his first book,

"Memoirs of a Man," he gave incredible and unquotable instances of it, and

elsewhere also. Americans, as a rule, are far less reticent on

domestic questions than Englishmen. Scotland is notable in the same

way; I have heard at public assemblies there things said before a mixed

audience, by educated persons, which no class in England could anywhere be

found to utter. We have reservation it is not well to disregard,

since it is a sentiment of civilization, and means moral refinement.

It was from Scotland this subject first came into England. In these

days of Board schools and science lectures, physiology can be explained to

girls, whatever they need to know, by lady physicians. Youths should

be taught by a medical professor in the same way; and no course of

education should be considered complete until a series of select class

lectures had been given, so that domestic knowledge should be insured of

all that can affect, for good or evil, the future of the human race.