|

[Previous

Page]

The Derby Congress.

CHAPTER XIII.

|

|

|

J. B. REST,

Secretary. |

THE

Derby Congress—the sixteenth of the series—was memorable in two ways:

(1) For its official presidential vindication of profit-sharing; (2) For

being the occasion of the formation of a Co-partnership association which

has since acquired extension and permanence.

It was expected that the distinction of the Derby Congress

would be an Inaugural Address by Lord Shaftesbury. Unfortunately the years

of generous and strenuous duty, which he had imposed upon himself, in the

interest of unfriended workers, had too much impaired his health for him

to fulfil the office

of president. Lord Shaftesbury was a nobleman of two

natures. In politics he would withhold power from workmen. In humanity he

would withhold nothing from them which

could do them good. In theology he knew no measure. Upon Professor

Seeley's book, "Ecce Homo," he pronounced a judgment, [6] which would

inevitably have handed over the luckless but liberal professor to Torquemada—the cruelest of all the inquisitors. Yet Lord Shaftesbury—was

so courteous, tender, and friendly to Dissent that he laid more foundation

stones of Dissenting Chapels than any other man. Should England one day,

like some other ancient kingdom, share the fate of lost civilisations and

explorers come to it and excavate its ruins, they will come upon so many

stones deposited by

Lord Shaftesbury and bearing his name, that they will write home and

report they have discovered the English King of the last dynasty. Whatever

contradictions the biographer may have to record in the character of Lord Shaftesbury, everything will be forgiven him in history by reason of his

generous love and noble exertions on behalf of factory children, for whom

he procured the Ten Hours Bill, and worked to improve the condition of

women, as well as children, in mines and collieries. Public health,

emigration, and ragged schools were subjects of his generous solicitude. Penny banks, drinking fountains, and model lodging-houses also engaged his

kindly solicitude. Lord Shaftesbury was one of the earliest slum

explorers. He was essentially and exclusively a social reformer, and took

no part in political amelioration. He believed that working people only

clamoured for political enfranchisement, because they were ill-used and

uncomfortable, not because of any manly aspiration for such power as

should enable them to have a political voice in the determination of their

own destiny; just as the Christian socialist believed that alienation of

working people from the Church was due to social hardship and neglect,

and not to intelligent conviction of error of doctrine. We owe the noble

service they rendered to co-operation to this belief—just as the working

class owed Lord Shaftesbury's great services

to a similar persuasion. There was undoubtedly a deep and honourable

sentiment of humanity in the heart, both of the conservative, socialist,

and Christian philanthropist. Just as George Eliot's "Adam Bede" and

"Felix Holt" were Positivist Chartists, Kingsley's "Alton Locke" was a

Churchman's

Chartist. They were no more like the true Chartist than a hardy mountain

plant is like a hothouse tulip. The Chartists to be met in conventions,

who, like the writer, were taught by Francis John Arthur Roebuck and John

Stuart Mill, had political independence, self reliance, and co-operation

in their blood.

Lord Shaftesbury's sympathy with co-operators was a moral affinity. He

expressed the opinion, which had little acceptance in his day, that the

agencies for planting Christianity among heathen nations should include "the secular missionary who must precede the Christian teacher, to prepare

the soil by social amelioration, before the seeds of Christianity could

take root." As co-operation was devoted to the science of material

betterment, Lord Shaftesbury did not hesitate to identify

himself with it. Like Faraday he had a dual mind. Faraday reasoned like a Sandemanian on questions of faith, and like a philosopher on questions of

science. Lord Shaftesbury took, we have said, no interest in political

progress, but in social progress he reasoned like a philanthropist.

In Lord Shaftesbury's absence, through failure of health, Mr. Sedley

Taylor, M.A., of Cambridge, delivered the Inaugural Address at the

Congress. If he did not invent, he had popularised that wholesome term of

industrial advocacy—"profit sharing." Before, and since, we have had

inaugural addresses delivered to Congress by Presidents who were half

hearted as respects the participation of profit—by some who spoke with an

evasive heart—by some with an alien heart—and by some with no heart at

all. But Mr. Sedley Taylor had a whole heart on the subject, with nothing

dubious about him. At the Leicester Congress (which preceded by a few

years the one at Derby), Mr. Auberon Herbert spoke as an Individualist, to

whom co-operative altruism seemed unknown. So little was he in sympathy

with the principle of participation, which alone makes co-operation worth

having (as all stores know), that he said, in his own salient way, that "he thought we must regard him as the

'Devil's Advocate.'" It fell to the

writer to speak to the vote of thanks to him, who said that if it were

true he was the Devil's Advocate, it proved the good taste and sagacity of

Satan to send such an agreeable and seductive representative among us. Mr. Sedley Taylor who had nothing doubtful or Satanic in him—proved to be a

substantial, straightforward advocate of the principle which made the

co-operative movement and endowed it with a message to Labour, now heard

in no uncertain tones, and in louder voice from year to year. This was the

main co-operative distinction of the Derby Congress, especially as it was

there the Labour Association was formed.

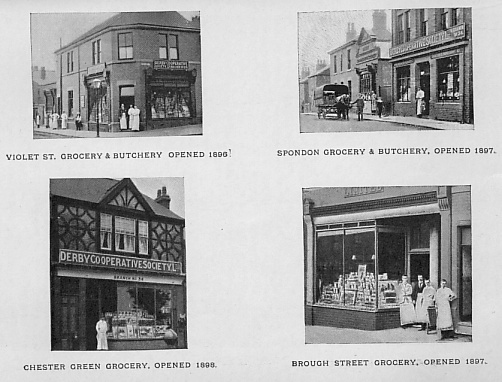

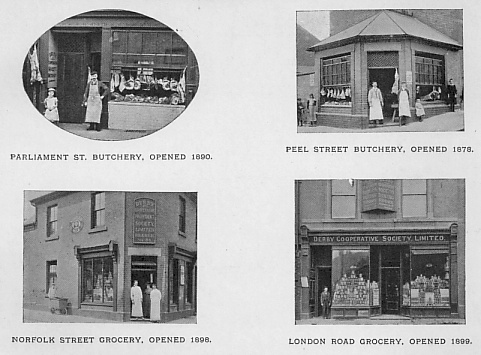

The Derby Society published a handsome little volume entitled the "Congress Guide Book." It was preceded by an illustrated historical survey

of the ancient town of Derby and its environs, "All about Derby;" the

historical part was a separate book by Edward Bradbury and Richard Keen

which was incorporated, by arrangement, for information of delegates. Mr. Scotton was the author of the co-operative portion of the volume, which,

enabled the delegates to understand the rise, progress, vicissitudes, and

successes of the growing society

of co-operators, who were the liberal and courteous host of all who

attended the Congress. It is a distinction for any society to attain a

position which justifies it giving an invitation to the whole co-operative

body to hold an Annual Congress in its midst; and it is a distinction to a

society that its position should be thus officially recognised, and its

invitation accepted. In justification of the society, the editor of the

Record made a financial summary of its business from January of 1873, to

the January of 1883. During that ten years it had received for goods

sold the sum of £846,011. 11s., on which was realised a profit of

£105,138. 1s., which had been divided as follows:—

|

Paid as Dividends on Members' Purchases |

£75,667 |

3 |

9 |

|

Paid as Dividends on Non-members' Purchases |

2,922 |

17 |

10 |

|

Interest on Members' Capital |

19,222 |

19 |

5 |

|

Since 1876 for Educational Purposes |

577 |

5 |

7 |

|

For Depreciation of Property |

3,009 |

10 |

2 |

|

For Depreciation of Working Plant |

3,735 |

4 |

3 |

|

TOTAL |

105,138 |

1 |

0 |

It will be of interest to the new members of the society if we here

recount incidents of the Congress.

Pleasant Derby was filled early on Monday morning, June 2nd, 1884, with

familiar faces. In every hotel in which a visitor looked to greet old

friends he found groups of distinguished co-operators. Many had travelled

during the night. Mrs. H. R. Bailey, Mrs. Benjamin Jones, Miss Greenwood,

Mrs. Acland, and other ladies, had been in Derby

during Sunday. On that day the Right Rev. Lord Bishop of Southwell

preached before the co-operative visitors in the Parish Church, and dwelt

usefully upon the higher aims of co-operation in terms which gave

satisfaction, instruction, and pleasure to the hearers. In the evening the

co-operators had like advantages in listening to the Rev. J. R. Stevenson,

who preached to them at St. Mary's Gate Chapel. His eloquent discourse was

frequently spoken of afterwards by the hearers.

Mr. Sedley Taylor, as has been said, delivered the presidential address,

which commanded great attention by its vivacity of delivery, and variety

of facts, showing that participation in industrial profits was a

commercial, moral, and industrial advantage.

The Bishop of Southwell and Lady Laura Ridding spent Whitsuntide in Derby,

and stayed at the Royal Hotel. There his Lordship received many visitors,

and entertained at his own request leaders of the co-operative movement,

including

Mr. Robert Hilliard and Mr. Scotton. As Lady Ridding is a daughter of the

Lord Chancellor, he attended the installation of the Bishop, and made a

remarkable speech at a meeting of the clergy, intended for an audience

elsewhere, worth repetition

and remembrance. Lord Selborne said, "Freedom, and he thanked God for it,

had now attained such a point of completeness in this country that every

man might think and say, every man might publish, whatever he would,

provided he did it with some decent respect to the feelings of others.

Authority was a . . . . less power in these days than in

former times; things depended more upon convictions. All things were put

upon their trial, and truths were being called in question. There were

dangers of social disturbance,

perhaps, all around them. How were they to be met? He thought he could see

some things which were needful for the purpose. The first was complete,

absolute, and determined justice to all men, to those with whom they

differed most, and who were the antagonists of the truth they cherished

most, absolute, unflinching, unswerving justice. The second point that was

necessary was a self-sacrificing spirit of sympathy with all sorts and

conditions of men, whether they spoke evil of you or not."

This, from a Lord Chancellor, was a noble charter of intellectual liberty. The Derby Congress will always be memorable for it.

Mr. Scotton delivered the address on the second day. Notwithstanding the

many unceasing duties he had discharged in the interest of the Congress,

he spoke with force and pertinency, and vindicated the society with great

effect from local aspersers, who had sought to prejudice it during

congress time. One anonymous adversary was "afraid the working men would

lose half the capital they had in the store." He forgot, said Mr. Scotton,

"that if they had not been members of the co-operative store, they would

not have had a bit of capital to lose." He paid a just tribute to the

local press of Derby, which has always dealt fairly and impartially by

co-operators, treating them exactly as they would any other organisation

in

the town. Master of congress business, Mr. Scotton presided over its

proceedings with marked efficiency.

Mr. Harold Cox (now the secretary of the Cobden Club) brought a letter

from the Parisian co-operators, and the United Board were empowered to

establish relations with French co-operators. Thus, the Derby Congress had

also a feature of International Co-operation.

Mr. Purcell, a Wesleyan local preacher, read a half-alarming paper on the

land question, which aroused Mr. Neale's conservatism, and he denounced

the author without any tenderness. Certainly the tenets avowed would have

compromised anyone, not a preacher. Mr. Purcell was, nevertheless, the

author of a tract of interest entitled "Five Requirements of

Co-operation." It appeared in 1877 and contains important

suggestions—since acted upon. The writer had years ago the pleasure to be

Mr. Purcell's guest, and very pleasant was the sojourn in his house. Mrs.

Purcell was a most gracious hostess, as many at this Congress found, as

she was one of the ladies, who, with Mrs. Scotton, dispensed refreshments

at the soiree.

Mr. Harold Cox, an adventurous student at Cambridge, made two

communications to the Congress with confidence and distinctness. Mr.

Bolton King, landlord of the Radbourne Manor Farm, made a short and

welcome address. The paper upon the farm was read by Mr. Johnson, a solid,

burly-looking farmer. The language was of great simplicity and precision,

the similes pertinent and fresh from the farmyard. The homely rural voice

of the reader, and his accuracy of delivery made an amusing contrast. The

good sense and associative spirit expressed in the paper were more unusual

still. Regarding the mastery of the subject and the completeness of the

information given, it was difficult to remember any previous paper on

farming which equalled it.

Ladies were more numerous than at former Congresses. It was felt that a

real part of co-operation will be in their hands. Already one or more

ladies were delegates and will very much increase the interest of the

Congress when they become occasional speakers. Ladies have addressed the

Congress in previous years.

|

|

|

W. F. TOWNSON,

Treasurer. |

One art feature of the Congress was supplied by Mr. Acland, who brought

some instructive and cleverly drawn diagrams representing the vicissitudes

of common forms of trading as compared with better security afforded by

co-operation.

The Manchester Co-operative Printers brought one of Godfrey's gripper

machines, which worked in a recess at the entrance to the Atheneum. Over

it was a long placard bearing the words "Co-operation a Cure for

Poverty." As the exhibition was free, country people came in, and they

evidently thought we were curing poverty by steam, and pressed round the

gripper with great curiosity. Photographs were taken of the Congress at

the Arboretum, which must be a pleasant reminiscence now, both of the

local leaders and visitors to the Congress, as the plate was remarkably

distinct.

Some Makers of the Society.

CHAPTER XIV.

FORMERLY history used to record only the career of

kings and leading chiefs in the field. Many of the generals were mere

knaves on horseback bent on the annexation of other people's lands. Some,

both kings and commanders, had merit and deserved a place in history. In

these later days we have come to recognise the service, heroism, and

devotion of the "rank and file" of the great army of progress—the

"unnamed demigods" as Kossuth called them, whose bones lie in unnoted

graves, but whose valour brought the victory. In co-operation all are

workers, and many who are never named after their death, are honoured in

their day and recognised in history. In a co-operative society all

officers have been workers—and are officers because they have been

workers. There is no privilege in co-operation, save that of service. This

chapter contains brief biographical notices of men who have been

conspicuously makers of the society.

If truth were told more at length and space were greater, many women would

have a place here. No men could make the sacrifices they do for the

advancement of the cause, were it not for the tolerance, or goodwill, or

aid, of their wives. The good a man may do is a good deal dependent on the

acquiescence of his wife, who often suffers neglect that he may pay more

attention to the welfare of others. There will in the future be

recognition of women in public and co-operative affairs, where, hitherto,

all honour has alone been given to men. When Mrs. Laurenson first proposed

Women's Guilds, and Miss Greenwood joined in promoting them, few, save

they, had any belief in them. They are now an important propagandist force

in the co-operative movement. All who work for a society and are true to

it, are makers of it. The following makers of the Derby Society have well

earned places in this Jubilee History.

Mr. John Riley was born July 9th, 1835, in Leicester, and was the oldest

of fifteen children. On coming to Derby, he obtained a situation in the

locomotive department of the Midland Railway. In 1859 he joined the

society, and was elected a member of the committee in 1867. In 1870 he

became chairman. The increase of business rendered a manager necessary,

and he was unanimously appointed to this office at an election in May,

1872, and held it more than fourteen years. He was one of the most

earnest, diligent, painstaking officers any society ever had. He was

always to be found at his post, and when the committee pressed him to take

relaxation, he always declined until the year of his death, when he took a

holiday in Germany and returned to his duties in excellent health. During

the time he held office the society opened twelve branches. Mr. Riley's

life had a tragic ending. He was killed in 1886 before the Albert Street

Stores. He had dismounted from his trap, when a brass band in the street

startled the horse. Mr. Riley led him a little way to soothe him, when the

noise continuing, he suddenly took fright, knocked Mr. Riley down and ran

over him. He died in a few days from the effects of his injuries, to the

lasting regret of the society which he had served so well.

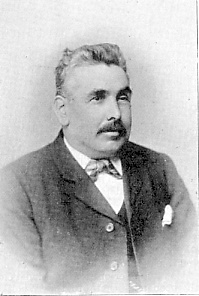

Mr. Robert Hilliard, the manager of the society, is a native of Derby, and

is essentially a self-made man, the best order of men extant. He began

life in a position from which only one of a strong nature could emerge;

but by perseverance, integrity, and hard work, he has attained to a

position of

distinction and honour. On May 5th, 1862, the name of R. Hilliard appears

in the minutes of the committee. No other name of Hilliard appears until

April 16th, 1866, when Robert Hilliard was first elected a member of the

committee. He was at that time a fitter in the employ of the Midland Railway Co. He was soon elected chairman of the Committee of

Management, which office he held eleven years. Up to 1876 the committee

elected the president each quarter, from among themselves. An alteration

of rules left the election of president

with the members at the annual meeting. Mr. Hilliard was

the first president elected under these rules. In 1886 he was appointed

manager of the society's stores, in succession to Mr. Riley, and so

successfully has he performed the duties of that office, that for the

fourteen years ending December last, the net profit made has been

£371,318. Mr. Hilliard was a member of the Board of the Midland Section of

the Co-operative Union for eight years, and only resigned that office when

he was appointed manager. Like Mr. Woodhouse he is an eloquent and

effective speaker, and was continually in request at societies' festivals

and meetings, often delivering addresses of use and brightness and power,

as has been incidentally recorded in preceding chapters.

Mr. Amos Scotton stands also in the first rank of the servants of the

society. He joined the society in 1858, thus comprising a connection with

the society of 42 years, for, with the exception of a few months, he has

been a member of the society since 1858. So far back as 1859 he was

appointed assistant secretary. In 1863 (described as then residing in New

Street) he was elected a member of the "Committee of Management"—a title

peculiar to this society, which continues to this day as the name of the

committees—the term Directors not being used. He received on that

occasion 128 votes. In 1875 he was president of the society. In the same

year he was elected a member of the Midland Section of the Central

Co-operative Board. In 1877 he became its secretary. This office he held

until 1891, when he retired from the Board. In 1890 he was elected on the

committee of the Co-operative Wholesale Society, which office he holds at

the present time.

He well remembers the time when the receipts of the society were but £150

per quarter, and he often refers with pride and pleasure to the fact that

he has lived to see the receipts £95,677 per quarter; a progress

remarkable, if not unprecedented, in the history of the movement. He hopes

to live to see the sum £100,000 a quarter. Mr. Scotton, besides editing the

Monthly Record eleven years, was the continual promoter of the society. He

willingly fulfilled any duties to which he was appointed, without

hesitation, manifestly considering himself as a servant at command of the

society whose progress was his continual incentive. In addition to

constant official work, he had made countless speeches and addresses to

this and other societies. When he ceased to be chairman of the Federal

Corn Mill in 1878, Mr. Chadwick,

chairman of the educational committee of the Leicester Society, made, as

we have recorded, a presentation to him as "a memorial of his striking

and instructive address on 'Co-operative Cottage Building,' delivered

before the Leicester Society, and in testimony of his usefulness and

long and zealous labours in the co-operative movement." Now, 22 years more

of similar service have to be added to his long and distinguished record. Those who wish to estimate the work of Sir Christopher Wren, are told on

his monument in St. Paul's Cathedral, "to look around." Those who would

form an idea of Mr. Scotton's services to the Derby Society may look

through these pages where they are again and again mentioned, under the

circumstances in which they were rendered.

Mr. George Smith joined the society in the spring of 1858, when the stores

were situated in Victoria Street, doing a business of £130 per quarter,

or an average of £10 per week. At the end of 1859, the business was

removed to Full Street. In the first quarter of the following year Mr.

Smith was elected secretary, and held office uninterruptedly for 21

years. At the time the secretary began his duties, the receipts had risen

to £16. 10s. per week. In the following year the receipts rose to £63 per

week. It was soon found necessary that the secretary should give up his

ordinary employment, and devote the whole of his time to the duties of his

office, and thus he did for nearly 22 years. He lived to see the society

grow from 350 to 4,500 members, and from one small room to a large Central

Store, with 17 branches, and 12 departments of trade. During the 21 years

this secretary held office, the society realised a profit of over

£100,000. He was a man of few words, but of sound judgment, developed and

matured by long experience. A short time prior to his last illness, he was

solicited to attend a society's meeting, and address its members. He

declined on the ground that "making speeches was not at all in his line,"

but said, "he often wished he had that gift, for then he could give many

remarkable instances how members, after joining the society, had never

invested a penny in it, though year by year their share capital had

increased until they had £100 to £150, and in many cases £200, standing to

their credit in the books." It is said talking comes by nature, wisdom by

silence. Mr. Smith had the silence and the wisdom, which a little talking

would undoubtedly have made more useful. Seeing how readily some

persons talk who have nothing to say, it is a misfortune when one who has

ideas cannot, or does not, express them. Mr. Smith was quite free from the

contempt of speech, sometimes expressed by way of self-defence by some who

lack the faculty. On the contrary, Mr. Smith had great respect for

pertinent and timely words, as he told Mr. Scotton. It may be said that

Mr. Smith had a gift of silence (a very great gift at times) and a natural

disinclination to talk. His choice was to put his thoughts into acts

instead of words—a very good preference, when the thoughts are good. Mr.

Smith died September 4th, 1881.

Mr. John Swift joined the society in 1858, in 1859 he was appointed a

trustee. This gave him a seat on the committee of management. A subsequent

Act of Parliament abolished the office of trustee, and in course of time

Mr. Swift was appointed treasurer, succeeding the late Mr. Samuel Smith. The business of the society kept constantly increasing, and in 1871 he had

to give up his employment, his whole services being required by the

society. In September, 1881, he was elected secretary on the death of the

late Mr. G. Smith, which office he held up to the time of his death with

distinction and benefit to the society. Like Mr. G. Smith he has a place

in the affection of all members who knew the store in his time. He is

always spoken of with regard, and a large portrait of him hangs in the

committee-room. It is no mean proof of his manly sense of self-help that

he rose from being a blacksmith in the workshops of the Midland Railway

Company to the position of an influential treasurer, and afterwards

secretary, of the society. Mr. Swift died 1899.

Mr. George Woodhouse, the president, is a native of Derby. He joined the

society in 1875, and thus has been a member twenty-five years. He was

elected on the board of management in February, 1884 (the Derby Congress

year), and was elected president in September, 1886, which office he has

held to the present time. In fact, he has so gained the confidence of the

members that there has not been any opposition during the whole fourteen

years of his presidency. It is relevant to record that the first year he

held this office the number of members was 5,241, at the end of last year

they were 13,179. At the end of his first year of office (1887) the

capital of the society was £83,258, at the end of last year it was

£182,763, an increase in twelve years of near £100,000.

Mr. Woodhouse was elected on the Central Co-operative Board in the year

1895, and at the present time is chairman of the Midland Section of that

Board. He is an effective speaker, and being but 47 years of age, there is

undoubtedly a useful career of co-operative work before him. His power of

advocacy and service are possessions of great advantage to the future of

the society.

Mr. J. B. Rest is a comparatively young man, but early in life his

sympathies were drawn to the co-operative movement. He became a member of

the society in 1888, and up to last year held a responsible position on

the clerical staff of the

Midland Railway Company. At the beginning of last year (1899) the secretaryship of the society became vacant by the sudden death of Mr.

Swift. Mr. Rest was elected to that position by a large majority. This was

the first election conducted on the same lines as members of the Town

Council. It is manifest he was the deliberate choice of the members, to

whom he gives every satisfaction by the promptness and civility with which

he discharges the duties of his office. Judging from his name, Mr. Rest

must have descended from an ancient Derby family, of the days when the

town was as semi-stationary as the Derwent, and not moving much faster. He, however, usefully belies his pleasant name of repose by his assiduity,

his business talents being in accord with the activity and progress of the

Derby of this century and the enterprise and onwardness of the

Co-operative Society.

Mr. Mather is another who is entitled to enumeration in this place, but

the reader will find his long and distinguished career described in the

chapter on the Midland Railway Institute.

Mr. Samuel Smith also deserves a place among the principal officers of the

society who was long connected with it. He joined it at the beginning and

was one of its early treasurers. He was a life-long teetotaler, which

fortunate persuasion has been the inspiration of so many excellent

co-operators in all our societies. The reader will remember he was the

counsellor of the George Yard pioneers, and its first president.

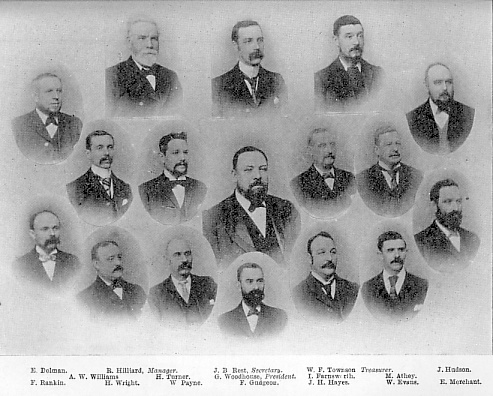

Other members of the society who in various capacities as committee-men,

and in various departments, have rendered important services are entitled

as far as it can be done to honourable enumeration.

Thomas Rushton Brown is the only survivor of the first George Yard

Society. He was born in Kensington Street, Derby, December 13th, 1826. His

father was a warehouseman to John and Charles Bakewell, grocers, Market

Head. His mother had been 13 years a servant in the same family. He

was sent to school down a yard in Sadler Gate. He tells of the dark days

of his youth—how wages were low, bread very dear; no gas in houses, only

a few small oil lamps in the street,

at very long intervals, making darkness more visible. At night watchmen

tramped the streets with their rattles and lanterns. As the reader has

seen in the chapter on George Yard, he took part in all the vicissitudes

of those patient, plodding, persevering carpenters and joiners, of which he was one. Being a builder also in a

small way, he executed various commissions for the society in alterations

made in Full Street, Park Street, and Nun Street. About 1863 he left Derby

to reside in Acton,

near London, where he has long been in business. He is still hale, active,

and bright. Mr. Brown visited Derby last year, and assisted in verifying

the sites of the earliest stores.

Mr. W. F. Townson began his career as a teacher in one of the Public

Schools of the town, an appointment he held for four years. The business

of the society increasing rapidly, it became necessary for the secretary

to have assistance, and Mr. Townson was appointed clerk in October, 1876;

and when the late Mr. Swift became secretary in 1881, Mr. Townson

succeeded him as treasurer, which office he still holds. He is a man of

rather retiring disposition (natural to a good treasurer)

but very painstaking in his work. When it is considered that during the

time he has been treasurer, the trade of the society has been £3,459,000. This sum large as it is, does not represent all that passes through his

hands—yet during the whole time of his office there has not been a single

complaint. The society may be said to have in him a very efficient,

reliable, and trustworthy officer.

Mr. M. Athey joined the society in 1877, and was elected on the committee

in 1886, thus being the senior member of the board. He has been a delegate

to local conferences, and in various ways has been an entirely useful

member of the society.

Mr. F. Gudgeon became a member of the society in 1886, and was elected a

member of the committee in 1891, and is still a member of the board,

having been re-elected each year. He represented the society at the

Woolwich Congress.

|

|

|

B. WEBSTER. |

Mr. B. Webster joined the society in 1879, was elected on the committee in

1882, retired from the committee in 1885, was re-elected in 1886, and

served until 1890. He has represented the society at the quarterly

meetings of the Wholesale Society. He was appointed, with Messrs. Hilliard

and Townson, to represent Derby at the 21st anniversary of the Wholesale

Society, and was also elected to represent the society at the Congresses

held at Dewsbury, Huddersfield,

Perth, and Peterborough. He was re-elected a member of the board in 1889,

a position he has since resigned in consequence of ill health—which, much

to the regret of his colleagues, lately ended fatally.

Mr. E. Dolman joined the society in 1878, and was elected a member of the

committee in 1892, which office he still holds. He has frequently been a

delegate to conferences and represented the society at the Congresses held

at Woolwich and Peterborough.

Mr. I. Farnsworth became a member of the society in 1880, and is the son

of one of the oldest members, his father having joined the society in

1862. Mr. I. Farnsworth was elected on the committee in 1894 and is still

in office. He was a delegate to the Derby Congress, and for several years

was an officer of the penny bank.

Mr. H. Turner joined the society in 1885, and was elected on the committee

of management in 1895, and still retains his seat on the board. He

represented the Derby Society on the Committee of the Midland Exhibition,

in 1898.

Mr. J. H. Hayes became a member of the society in 1890, and was elected on

the committee in 1895, and still retains his seat on the board. He is also

a member of the educational committee, and represented the society at

Liverpool Congress last year.

Mr. J. Hudson joined the society in 1886, and became a member of the

committee in 1896, and has frequently represented the society at local and

district conferences.

Mr. W. Payne became a member of the society in 1882, and was elected to a

seat on the committee of management in 1898. He is also a member of the

educational committee, and has frequently been a delegate to the Wholesale

Society's quarterly meetings, and represented the Derby Society at

Carlisle, in 1887, and at Perth, in 1897.

Mr. F. Rankin joined the society in 1884, and was elected to the committee

of management in February, 1899, and has represented the society at local

conferences.

Mr. W. Evans has been a member of the society since 1891, having

previously been a member of the Barnsley Society. He was elected on the

committee in May, 1899, and has represented the society at the quarterly

meetings of the Co-operative Wholesale Society.

Mr. A. W. Williams has been a member of the society since 1882, and when

the education classes were formed he became a member, and at the

examination he obtained both a prize and certificate, and was elected to a

seat on the board in August, 1899.

Mr. H. Wright joined the society in 1887, and was elected to a seat on the

board of management in November, 1899, and has represented the Derby

Society at the quarterly meetings of the Wholesale Society.

Mr. E. Merchant has been a member of the society since 1884. He was a

strong advocate of the Educational committee being a separate body from

the general committee. In May, 1898, a committee was so appointed, and at

its first meeting Mr. Merchant became its honorary secretary, a position

he held until May, 1900. He was elected a member of the general committee

in February, 1900, and was a delegate to the Huddersfield and Perth

Congresses.

Among the names of those who have, and who still work for the advancement

of the society, earlier and later workers, are W. Twigg, T. Barrodell, J.

Bradbury, W. Wilford, T. Wilson, H. Barrett, W. Hemm, F. Hickingbottom, J.

Henfrey, and J. Sherwin, to which may be added Henry Bates, for many years

the valued and esteemed manager of the Boot and Shoe department, who died

in 1883.

The oldest members on the books of the society now living, are J. Mather,

A. Scotton, Robert Hilliard, G. H. Eccleshare, and W. North.

The reader will observe a curious peculiarity in these brief sketches.

It is frequently enumerated in the illustrations of a member's career, the

growth of the society during his period of office and service. Americans

have this peculiarity in another form. In the biography of a man, his

weight avoirdupois is

frequently given. For instance, in the life of Dr. Channing, it

was stated that he weighed about 90lbs. Dr. Channing had a marvellous

voice, which made hearers wonder how so small a man should possess it. He

was so frail that he seemed merely

a voice. This item of weight does give the reader some idea of the bulk,

or otherwise, of the subject of the memoir.

A statement of the figures of the growth of the society during a member's

connection with it, does not mean that its progress was all owing to the

individual person in question, though, in some cases it may have been

largely owing, to him. Anyway it indicates the magnitude of the operations

in which he took part, and to which he was more or less a contributor, and,

in some instances, a real maker of the fortunes of the store.

The Midland Railway Institute.

CHAPTER XV.

THE Derby Co-operative Society owes much to the

frequent courtesies of the Midland Railway Company, and is glad of this

opportunity of acknowledgment. From the beginning to this day the

fortunes of the stores have been also indebted to the intelligent and

continuous support of workers at the Derby Station. It is, however,

the Railway Institute which is mainly entitled to notice in this chapter.

The company have built and maintained the Institute for the advantage of

the men who have, through its means, acquired wider knowledge—knowledge

outside that of their calling—the capacity for social as well as public

service.

The Great Midland Railway had been opened only ten years when the

co-operative society began. It was opened May 5th, 1840, and bore the name

of "The Midland Counties Railway from Derby and Nottingham to

Leicester." [7] It had naturally great influence upon the fortunes of the

town of Derby, commercially and socially. It brought life and growth to a

community which had known lethargic centuries.

It was stated at the trial of Wells and Co., in 1892, that the Midland

Railway at Derby employed 10,000 workmen. A considerable number of them

are members of the store. The chief officers of the society who, in former

and later years, have done so much to advance its usefulness, have been,

or are railway men. The success of many of our great stores elsewhere, has

been owing to railway men joining them, and

aiding them by their practical knowledge. But nowhere has this been done

to the same extent it has in Derby. Indeed, no railway company has taken

so great an interest in the co-operative welfare of those in their employ,

as the Midland directors have.

At the time of the Leicester Co-operative Congress of 1877, Mr. Ellis, the

chairman of the Midland Company, presided at one of the meetings, and made

an admirable and weighty speech. He put the practical features of

co-operation in a nutshell (his squirrel hearers knew how to get at the

kernel). Success, he explained, depended upon administration and

confidence, self-reliance, and thrift. Its merit, he said, lay in making

the best of such means as they had. This was the wise language of

instruction and encouragement, without patronage. He said his policy was

shared by all the directors. He alluded to the honourable fact that the

Midland carried the poor man as fast as his richer neighbour. It was by

the masses that the railway lived. He modestly said of himself that it was

not ability, but by honest industry and hard work that he found himself in

the position he held. He gave expression to the opinion that not

over-labour but luxury was the danger of the nation. The well-to-do were

too self-indulgent. Even the working class were luxurious, if regard be had

to the millions they wasted every year in unnecessary and enervating

drinking. This was their form of luxury. Mr. Ellis was a member of the

Society of Friends. His speech showed that the inner light of the Quakers,

though sometimes narrow, was wiser than the outer light of many less

attentive to the dictates of a cultivated conscience.

The Midland Railway was the first to attach third-class carriages to every

train, and bring the poor man to London in the same time as the gentleman,

for which they had to pay the tax on third-class fares, costing the

company £40,000 a year. Workmen travelling from London on other lines

going north, were shunted at Blisworth, or other stations, for two hours,

while the trains carrying gentlemen went by. A workman at

Newcastle-on-Tyne travelling to London had to leave at 4-45 in the

morning, and did not arrive at Euston until 8 or 9 at night. To avoid the

travelling tax, companies ran what were known as "crawling trains." A

sailor, landing at Liverpool, going to see his mother at Edinburgh or

Glasgow, had to stop at 53 stations on his way. The "poorer class" of

travellers,

as an Act of Parliament called them, had reason to be grateful to the

Midland Company who paid the tax for them, and attached third-class

carriages to their swiftest trains.

This interest in the welfare of the people at large did not end there.

Contemporaneous with it was their honourable solicitude for the

improvement and advantages of the industrial army in its employment. From

the first the Midland Directors assisted in the formation of the Institute

which is now a distinguished feature of the station, and was an attraction

to

intelligent workmen who came to them. Mr. Samuel Smith, Mr. Hilliard, Mr.

Swift, Mr. Mather, and Mr. Sutton, who mostly came from Leicester and its

neighbourhood, joined the Railway Institute almost together, as they did

eventually the Co-operative Society.

Incidents in the early history of the Railway Institute will be informing

to many readers, since very few remain who can relate them. The directors

of the railway company gave the front rooms of two cottages in Leeds

Place, rent free.

Leeds Place was at the back of the present Institute. Mr. Mather joined in

1854, and Mr. Scotton in 1855, who was then,

and up to 1890, an employee of the company. The members

paid one penny per week. They soon outgrew these premises. At the opposite

side the entrance to the general manager's office, the directors built a

large room for the shareholders' half-yearly meetings, and they gave to

the Institute all the rooms underneath rent free. This building was

formally opened by Mr. John Ellis, the then chairman of the company. In

time the place became too small, and then the directors

built the present Institute. The payment is still one penny per member per

week. Mr. Swift was for many years on the council of the Railway

Institute. There were few workmen on that council, the rest being mainly

heads of departments. Mr. Mather joined that council in 1860, and has

been connected with it ever since. His name appears as the treasurer of

the Institute—he is an old co-operator, and has been president,

committee-man, and auditor of this society. Some time after two other

workmen were elected to that body; one (Mr. John Wilson) was for many

years an auditor of the Co-operative Society.

The slender accommodation of the Institute in early years, compared with

its present opulent conveniences, makes a striking contrast. In 1856, it

occupied the front rooms in

Leeds Place. It had for a librarian, Mr. Joseph Seal, an old employee of

the company, who occupied the back rooms and acted as librarian at night,

at the close of his daily railway duties. The catalogue was then written

on pasteboard and hung on the wall of, what they were pleased to call, the

"Library." Such was the humble beginning of the Institute,

now one of the noblest features of the town. It is a handsome structure of

good architectural design, which a workman may enter with pride. It would

be taken for a gentleman's institute by any one who did not know its

democratic uses. It has a real library of a remarkable character, and a

handsome

lecture and concert hall. Paintings lend their charm to the walls. A large

oil painting of quality and character, hangs in the corridor, presented by

the present general manager of the railway, Mr. George Henry Turner. Though large, the

Institute is in process of enlargement. The refectory is worthy of a

monastery of the middle ages—which had a dispensation

from all obligation of fasting. Some railways have convenient

dining-rooms, but as destitute of brightness as a poor house

interior. This refectory is very cheery, with vistas of shining porcelain

dinner and tea ware, which delight both eye and

appetite. Refreshment is very pleasant within its walls.

The Institute is an atheneum. There are classes for shorthand, French,

and, apparently, German, as there are facilities afforded for excursions

to the Continent, for the advantage of students of French and German;

there is also a dancing class and an orchestral band. At other times

lecturers occupy the hall, whom it is worth travelling far to hear.

The library is as remarkable in its simplicity and perfection of

arrangement as all things else in the Institute. Nothing equal to it is

known to the writer elsewhere. The noble custody of books is confided to

Mr. Ernest A. Baker, M.A., who has compiled a descriptive handbook of

prose fiction in

the library. It is a work of great labour. Only a person of wide knowledge

and cultivated judgment could have compiled

it. It is a book of independent value in any household, and to any

reader—who, if he be not wise when he begins with Mr. Baker for a guide,

will be wise when he ends.

Fiction writers of France, Germany, America, Greece, Turkey, Hungary,

Italy, Spain; Jewish, Scandinavian, Asiatic, and African authors are among

those with whom we are made acquainted: and, what is more, the books are

on the shelves,

which illustrate the novelistic genius of the nations—ready for the use

of the members of the Institute. Curiosity awakened can be at once

gratified. The authors are described, the period to which their works

relate, and the local scenes they may embrace—the characteristics and

distinction of the writers. Points of relevance and interest, unthought of

by the ordinary reader, are brought under his notice. It seems as though

the whole world of fiction, in every age and clime, is opened up before

the wondering peruser. If any person wants to have enlightened and

instructive opinions of works of fiction, he cannot do better than inquire

of one of the fortunate members of the Midland Railway Institute who has

read Mr. Baker's enlightening "Handbook to Fiction."

All the opinions given, where not absolutely Mr. Baker's, are founded upon

the best public criticisms extant, and often a sentence or two is given

from a critic who is named. Next to the capacity of forming just opinions

is that of knowing when others have expressed them, and both meet in this

handbook. Bad reading is worse than loss of time. It depraves the

understanding and fills the ear with verbiage, while good reading is a

gain for ever. It forms the mind and

chastens the taste. To have the run of this Institute and the guidance of

such a librarian is a prodigy of opportunity. If co-operators attain their

dream of running the world, and establishing the best kinds of education

for their members, they would do well to get Mr. E. A. Baker to compile

the handbooks of their libraries.

It was not until 1808 that the Quakers acquired a meetinghouse in Derby. The reader of an early chapter, will remember the trouble the town took to

prohibit Quakers from entering it. It was fortunate that they did not

accomplish their perpetual exclusion, seeing the great advantages which

Quaker officials conferred upon the railway and the workmen by their

judicious and munificent management. It is singular that a Society of

Friends first acquired the name of Quaker in Derby. George Fox, whose

intrepidity was such that no charter, or intimidation, could keep him out

of any place where he chose to go—presented himself in the town in 1650. When it got a live Quaker it kept him, in the unpleasant way of

imprisoning him for twelve months in its most unwholesome gaol. One day

Mr. Justice Bennet, who was not a pleasant, but a ready-witted person, was

addressed by Fox, who told him "he ought to tremble at the word of the

Lord." Whereupon he called Fox a "quaker," a name, which for the first time was applied to Fox's

followers. It was the Justice who ought to have quaked, for Fox never

quaked before anyone however

savage, nor before any imprisonment however vindictive. But it was clever

in Justice Bennet to conceal the quaking of his own conscience by imputing

it to Fox.

[Next Page]

NOTES.

6. What the noble critic said was "The book was vomited from the mouth of

Hell." Surely something ought to be done for the man who had made Satan

sick.

7. Mr. Scotton has preserved a copy of the placard

announcing the opening. |