|

[Previous

Page]

A Libeller Brought to Book.

CHAPTER XVI.

AS a general rule co-operative societies never go to

law with outsiders, nor with themselves. In cases of difference of

opinion among members their rule provides that any question in dispute

shall be decided by arbitration. Now and then a society is assailed

by tradesmen, who disparage it by misrepresentation. When the misrepresentation

is flagrant the society may take legal steps to vindicate itself. In

one instance the Derby Society had to do this, and the story of the trial

is sufficiently instructive to be told.

In 1892, one John Wells, trading under the name of "J. Wells

and Co." issued 25,000 handbills which the Society deemed libellous, and

resolved to bring the libeller to book.

Now, the law in these cases is that a Co-operative Society

registered under the Industrial and Provident Societies Act, 1876, may sue

and be sued in the perpetual succession and a common seal. There is

no single definition of a libel which can definitely guide those concerned

as to what is libellous. Each case must be considered in the light

of its own circumstances. A society however which considers that it

has been libelled has, before commencing legal proceedings, to determine

either that—(1) It has been prejudicially affected by the written or

printed statement in such a manner as would have given a right of action

had the persons affected been private individuals instead of a society;

or, (2) That the written, or printed, statement, impeaches the credit of

the society, by imputing to it fraud or dishonesty, or any mean and

dishonourable trickery in the conduct of its business, or which in any

other manner is prejudicial to it in the way of its employment or trade.

If the libel is contained in a printed handbill or pamphlet, which does

not bear a printer's name, there is a penalty prescribed for that

omission. This law is seldom enforced, except in cases of libel.

What the law is, as respects omission of the printer's name, it may be

useful to state here, as it is far from being generally known.

With reference to the "printing and distributing of handbills which do not

bear the printer's name and place of business at the foot thereof," 2 and

3 Vict., chap. 12, section 2, provides that "every person, who after the

passing of this Act, shall print any paper or book whatsoever, which shall

be meant to be published or dispersed, and who shall not print upon the

part of every such paper, if the same shall be printed on one side only,

or upon the first and last leaf of every paper or book, which shall

consist of more than one leaf, in legible characters, his or her name and

usual place of abode or business, and every person who shall publish or

disperse, or assist in publishing or dispersing, any printed paper or

book, on which the name and place of abode of the person printing the same

shall not be printed as aforesaid, shall for every copy of such paper so

printed by him or her, forfeit a sum of not more than £5."

The action against Mr. Wells was tried before Lord Chief

Justice Coleridge, at the Derby Summer Assizes, July, 1892. The

plaintiffs were the Co-operative Society which was defended by Mr. M. C.

Buszard, Q.C., and Mr. Graham, instructed by Messrs. Moody and Woolley, of

Derby. Mr. Buszard stated that Mr. Wells was charged by the

Co-operative Society with having published a libel upon them in relation

to their business. Mr. BUSZARD said: "The society

was incorporated under the Provident Societies Act, and carried on an

extensive business in the town as retail dealers in provisions and various

other things. Mr. Wells was a rival dealer in the provision line,

carrying on a somewhat similar business in various shops. The

Co-operative Society consisted of over 8,000 members belonging entirely to

the artisan class. Their capital amounted to £106,000, accumulated

by the artisan class, on which they received interest of 5 per cent, and

for every sovereign they spent at the store they received, every quarter,

a dividend which generally amounted to 2s. 6d. Mr. Wells issued a

handbill entitled '£1,000 reward, startling but true,' then followed a

statement purported to be made under oath by Elizabeth Thompson, of No. 5

Court, Bridge Gate, Derby, who had been to the co-operative store and made

sundry purchases, at prices which were compared with the lower prices for

which it was alleged, the same things could be bought at Wells and Co.

She asked for, and had the best things which were compared with the prices

at which very inferior things were sold by Mr. Wells." A further

allegation was made against the printer (whose name Mr. Wells endeavoured

to conceal). The printer, Mr. Bacon, to whom Mr. Wells gave an order

for 25,000 bills, (being an honest printer), represented that if the bills

bore no printer's name there would be risk to him. Mr. Wells did not

want any name to appear, as his personal action in the matter might be

traced. Mr. J. H. Etherington Smith, who defended Wells, sought to

show that printers often sent out bills without their name.

Lord COLERIDGE said: "It was not of the

slightest value for them to know what other people do. What had Mr.

Bacon done? was the question."

Mr. SMITH pleaded that it was "a sort

of special advertisement."

Lord COLERIDGE said: "It was very

special, no doubt, but its alleged meaning was that the goods purchased at

the store were sold at a higher price than they could be purchased at Mr.

Well's shops, and it asked the people of Derby whether they got a fair

return for their money. He (his Lordship) did not suppose the jury

would think that was an innocent rule-of-three sum."

Mr. HENRY HOROBIN,

an assistant in the grocery store, gave evidence as to the way in which

Mrs. Thompson made her purchases. It ought to be recorded that Mrs.

Thompson regretted the use made of her, of which she was not aware.

Then Mr. JOHN SWIFT,

the secretary of the society, gave evidence. "The society," he said,

"was managed by a board principally consisting of the better class of

artisans. They had 8,100 members, the great majority of them were of

the artisan class, a large number of them were railway men (10,000 being

employed at the head-quarters of the Midland Railway Company). The

capital of the Co-operative Society was £109,231. 11s. 2d." Mr.

Swift was very exact in his detail. He said the society dealt in 209

different articles. Mr. Wells had only selected 16. The

average dividend was 2s. 5¾d. They

were more than dealers. The society had spent hundreds of pounds on

education—had given £200 towards building the new Royal Infirmary, and £50

towards building the Deaf and Dumb Institution.

Lord COLERIDGE, in summing up, gave an

admirable statement of the aims and character of the Derby Co-operative

Society. He said: "The Co-operative Society of Derby is, I have no

doubt, a very useful and excellent institution. It has 8,100 members

and a capital of nearly £110,000, and it conducts its business according

to rules, which have been circulated by many thousands, and are

accordingly well known to anybody who wants to do business with them.

I don't understand that they ever pretended to be simply and solely a

trading corporation. They did say that they were a trading

corporation, making profits by trading operations, but at the same time

doing a variety of other things. First of all, by ready-money

trading, they have an advantage in the market, but at the same time there

are certain things which they do with their money, which is not trading at

all. They subscribe to charities; they help their members in

educational matters; they do a variety of things which are not strictly

trading, but still have to do with the profits in their trading.

Everybody who joins the society knows perfectly well that the payment of

one shilling will make a man a member, and the moment he becomes a member

he knows the terms upon which he has embarked. Being a large

society, it can carry on trade with considerable advantage, and it does

carry on business at a great number of places in Derby. It is almost

impossible for a great firm, or a great house, to succeed beyond the

ordinary run of success without doing so to the disadvantage of someone.

It is the condition of things in this country. Competition, so long

as it is carried out in an honest and straightforward way, is the life and

soul of the commerce of England. Mr. Wells may do all in his power

to get everybody to deal with him. But the law says that he must not

do this by unfairly attacking the character of a rival trader. If

you do that, the law says it is not fair dealing. Anything which is

stated to a man's discredit is a slander and a libel, and if it is written

down or printed, and especially if it is printed and published, unless you

can show that what is stated or published is either privileged or true."

Lord COLERIDGE summed up in favour of

the society, and gave his opinion clearly that Mr. Wells' handbills,

representing that the society was causing the people of Derby to incur

"wicked waste," by buying at the store instead of buying at his shop, was

libellous. Thus Mr. Wells was brought to book and his tricks of

trade exposed to all the country round. The result was published by

the society in these words.

"The action for libel against Mr. John Wells, trading as J.

Wells and Co., tried before Lord Chief Justice Coleridge and a special

jury at the late assizes, resulted in a verdict for the society with 20s.

damages and costs, with an injunction restraining J. Wells and Co. from

issuing any more bills of the character of the one complained of.

The penalty action for publishing the bills without the printer's name

being on, was settled by J. Wells and Co. agreeing to pay the society £50

towards their costs in this action. We are pleased to note that the

sympathy of the great bulk of the traders in the town has been strongly

expressed in our favour." Thus Mr. Wells lost money and character by

his defamatory handbill.

It is curious to record that Mr. Wells, the assailant of the

society, had at that time numerous shops in Derby, since, he has gone

down, and left the town, while the society has multiplied its branches,

and remains in the administration of a larger business than ever.

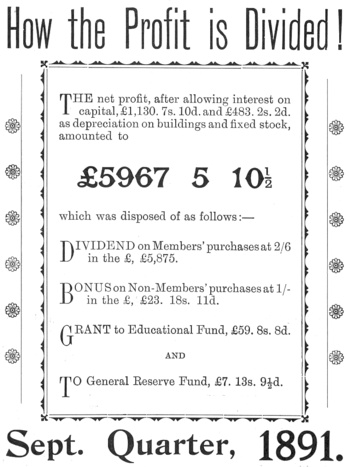

In 1891, the year before the trial, the subject of this

chapter, the Monthly Record published a very effective

advertisement worth citing. It attacked no tradesman, it made no

reflection upon anyone, but honestly showed what the society was doing.

It acted on the maxim of Antithenes: "A madman is not cured by another

running mad also."

FOUND!!

By Six Thousand Three Hundred and Seventy-seven working men in Derby an

increased share of the comforts and luxuries of life, through an

improvement in their social condition. This improvement may be

attributed to Co-operation, for in 1889 the sum of

£19,145 16 6

profit was realised by the members trading at their own shops. These

figures claim for co-operative enterprise a foremost position amongst the

commercial undertakings of the present century. Our ranks are daily

being augmented by numbers of intelligent men, who are learning that

AT THE

Co-operative Stores they may in reality "find," in the shape of dividends,

hard cash wherewith to provide against sickness, infirmity, and old age.

This knowledge alone is of immense value to the

CO-OPERATIVE

purchaser in this age of cheapness, as serious consequences sometimes

result from the use of goods of inferior quality. Thousands of

members of Co-operative

STORES

have found incalculable advantages and benefits in time of need, by having

a fund to which they could come and draw their own, and thus successfully

pass over a time of difficulty. Every working man can enjoy the same

advantages by going to the Secretary, at his office,

ALBERT STREET,

and paying 1s. 5d. entrance fees, then, after trading at the Store, they

will soon find out the benefits for themselves, and if they begin with the

new year, when it comes to its close instead of having a few candles or an

almanac for a Christmas box, they will have several pounds standing to

their credit, and will thus have provided for a "rainy day," and be in as

good a position as other men in

DERBY.

Another advertisement set forth as follows:—

Derby has not been further troubled with libellers, and enjoys friendly

relations with its neighbours, which, indeed, have in the main always,

subsisted.

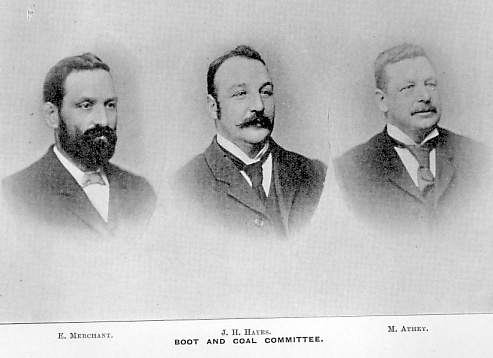

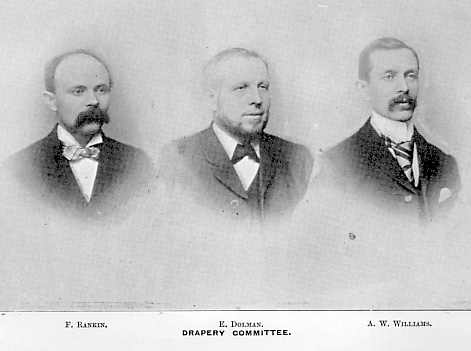

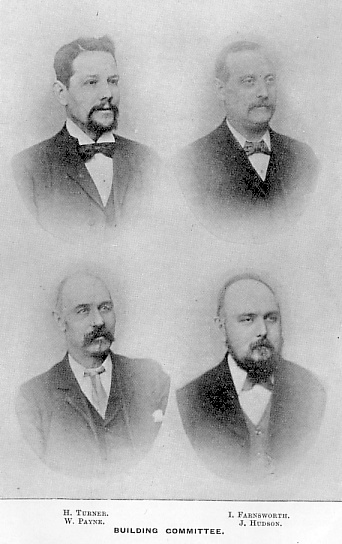

Committee of Management

CHAPTER XVII.

PRESIDENTS.

R. HILLIARD and G. WOODHOUSE (who is President at this time). These

are the first presidents appointed by the members. The committee

formerly elected their own chairman.

|

MR. |

M.

ATHEY |

Elected |

1886 |

|

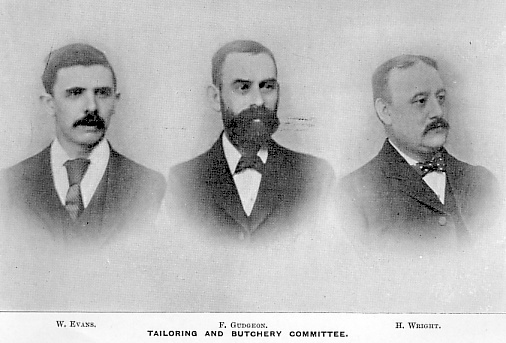

» |

F.GUDGEON |

» |

1891 |

|

» |

E.DOLMAN |

» |

1892 |

|

» |

ISAAC FARNSWORTH |

» |

1894 |

|

» |

H.TURNER |

» |

1895 |

|

» |

J.

H. HAYES |

» |

1895 |

|

» |

J.

HUDSON |

» |

1896 |

|

» |

W.PAYNE |

» |

1898 |

|

» |

F.

RANKIN |

» |

1899 |

|

» |

W.

EVANS |

» |

1899 |

|

» |

A.

W. WILLIAMS |

» |

1899 |

|

» |

H.

WRIGHT |

» |

1899 |

|

» |

E.

MERCHANT |

» |

1900 |

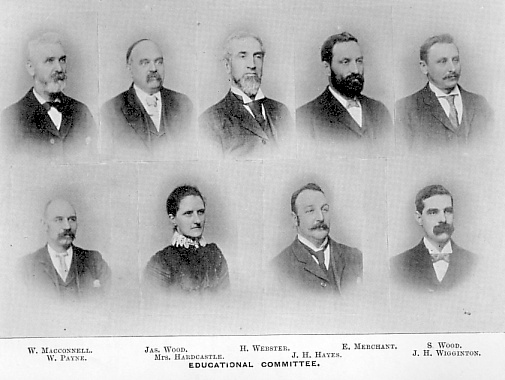

EDUCATIONAL COMMITTEE.

|

MR. |

H.

WEBSTER (CHAIRMAN) |

|

» |

J.

WOOD (TREASURER) |

|

» |

E.

MERCHANT (SECRETARY) |

|

» |

W.

PAYNE |

|

» |

J.

H. HAYES |

|

» |

W.

MACCONNELL |

|

» |

J.

H. WIGGINTON |

|

» |

S.

WOOD |

|

MRS.

|

HARDCASTLE. |

MANAGERS.

There have been but two general managers—

|

MR.

JOHN RILEY |

|

»

ROBERT HILLIARD |

TREASURERS

There have been but three treasurers—

|

MR.

SAMUEL SMITH |

|

»

JOHN SWIFT |

|

»

W. F. TOWNSON |

SECRETARIES

There have been but four secretaries during the existence of the society—

|

MR.

JAMES HENDERSON, 1849-1859 |

|

»

GEORGE SMITH, 1860-1881 |

|

»

JOHN SWIFT, 1881-1899 |

|

»

J. B. REST, 1899 |

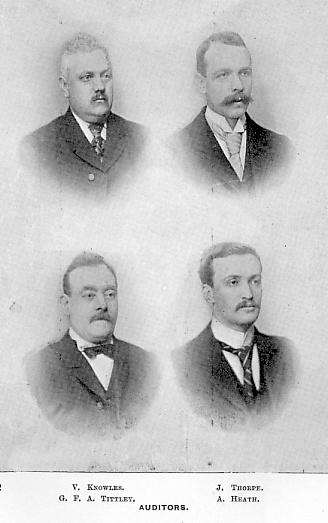

AUDITORS.

1. VICKERS KNOWLES, joined society September, 1889, elected auditor

August,

1891.

2. GEORGE F. A. TITTLEY, joined society November, 1883, elected auditor

November,

1894.

3. JOHN THORPE, joined society July, 1894, elected auditor May, 1897.

4. ARTHUR HEATH, joined society August, 1886, elected auditor November,

1899.

Distinction between Store-keeping and Shop-keeping.

CHAPTER XVIII.

IT is a duty in a special narrative of the

success—not to say triumph—of a new form of trade, to vindicate it from

the supposition of being unfair, or injurious, to its neighbours in

business. If co-operation has advantages it is owing to the

intrinsic merits of its methods, its principles and benefits conferred

upon its customer, which ordinary trading does not confer. Neither

shop-keepers as a rule, nor the general public, understand co-operation in

practice. This may be made clear by explaining the distinction

between Store-keeping and Shop-keeping. The principle on which a

shop is founded, is the profit of the proprietor. The principle on

which the store is founded, is the profit of the customer. The

principle of the shop is cheapness, generally at the expense of the

customer. The principle of the store is excellence, by which the

customer profits. The shop measures excellence by cheapness—the

store measures cheapness by excellence and trustworthiness. The

purchaser who thinks cheapness everything and thinks of nothing else, will

corrupt any seller. It is not wrong to look for cheapness—provided

the cheapness includes good quality. But he who makes cheapness the

measure of quality asks for an adulterated article—and commonly gets it.

Once a board of representative co-operators had to choose from tenders for

the erection of a large building, when, to the astonishment of all who

understood co-operation, a member, thought to have discernment, moved that

the cheapest tender

be taken, and it was. The motion was if not immoral at least

inconsistent. The board knew nothing of the principles of business

of the lowest tender, and had no moral control over the practices of the

firm; one tender came from a co-operative society, whose ability to do the

work was undoubted, and whose principles of procedure were known.

That tender was rejected because it was a little higher than the cheapest.

If members of a store all acted upon the principle of taking the cheapest

thing, it would be impossible to provide them with genuine articles.

It is worth recalling the wise words of Henry Ward Beecher,

who understood co-operation, as he did most things. His words were:

"It is the front part of the counter that corrupts the back part.

Men that sell are perverted by the men that buy. Buyers seek

'bargains' instead of being willing to render an equivalent for what they

receive."

The purchaser at a shop has no right in it. The

purchaser at a store has. He is one of the owners of it. The

buyer at a shop has no knowledge of the quality of what he buys, or whence

it comes. The buyer at a store knows, or can know, all about it.

The buyer at a shop knows nothing about its profits, and would be thought

impertinent if he asked, and would be told it was no business of his.

But it is the business of a purchaser at a store to know what its profits

are, and he has balance sheets furnished to him, from which he can know

everything. It does concern him to know what profits are made,

because he has a share of them. The accounts of a shop are secret,

the accounts of a store are open.

True, the store makes more profit than the shop, and the

shopkeeper thinks that what the store gains he loses. This is his

mistake. What we gain is not all taken from him. The store has

the larger number of customers and large numbers mean economy in expense

of administration. Besides the store buys with ready money.

That is another gain. The shop keeper mostly buys on credit.

That is a loss to him. The store takes ready money and has no bad

debts. The shop gives credit and stands to lose that way. So

the shop does not lose what the store gains. The shop does not make

it. Besides, what profit custom makes the shop-keeper keeps, while

the store gives it all to the customer and workers in it. Thus, in a

comparison of the shop and the co-operative store, the shop is not in it.

We write no word of reproach because the shop-keeping is

different from store-keeping. Each acts on a different system.

The object of this chapter is merely to show that the two systems are

intrinsically different and that co-operation has no reason to fear the

competition which it supersedes.

No doubt the shop-keeper suffers but little at our hands,

though he often charges us with being harmful to him. His enemies

are of his own household. It is the Shoolbreds and Maples, the

Whiteleys and Liptons, who, by great capital destroy all the little

dealers about them, plant shops in every town and compete with and

undersell the honest private dealer. These are the shop-keeper's

enemies. Why does he not attack them? He could do it if he had

unity and wit. And he would show more wisdom than by imputing his

difficulties to the co-operators.

The shop does not suffer from the store. Shop-keepers

seek to undersell the store—the store never seeks to undersell the shop.

It is the interest of the co-operative system not to sell below the market

rates, nor to lower the market. Every day some ill-informed person

will go into a store and say he can buy cheaper at the shops. The

shops have no customers who say they can buy cheaper at the store.

No store willingly joins in the miserable game of underselling its

neighbours. The more a customer pays at a store the more he

saves—since it all comes back to him in his dividend. Thus, the

store has no interest in underselling the shop. And the store, by

keeping up fair prices, has made the fortunes of scores of shop-keepers in

every town. Were they wiser than they are, they would see it an

advantage to them to have stores about them. We have often made

fortunes for them. They never made any fortune for us.

Much more might be said. But sufficient for the

purpose—is the evil thereof? We have merely sought to show that the

shop and the store represent two different systems, and stand side by side

each on its own merits, and the shop has in some cases inextinguishable

merits, as we might show if this were the place to do it. Anyhow,

there are now more than 42 millions of people in Great Britain, and not

two millions of co-operators. We leave to the shop-keepers 40

millions of customers. Should they not be content? Should they

begrudge us our minority of adherents?

The New Trade and the Old Trade.

CHAPTER XIX.

THE distinctions between the store and the shop,

explained in the last chapter, will appear plainer still if we compare the

new with the old methods of business. Co-operation is a new system

of trading. It supersedes the old system—which is antediluvian.

Ever since the flood shop-keepers looked to doing business with people who

did not know what they were buying. It would be unjust, and

therefore, unfair, not to own that shop-keepers have sometimes better

goods to offer than they find customers for, with sufficient knowledge to

perceive it; hence 'the saying, "If you offer pearls to swine they turn

again and rend you." Co-operators are liable to the same experience,

but they provide against this by educating their customers. The

shop-keepers neglect to do this. Mr. Augustine Birrell, M.P., has

told us that the commercial motto of the City of London is—" Beware of

the seller." With the old school the dealer's trade is often a

trick, or manœuvre, or war of wit, in

which the unskilled or uninformed purchaser goes to the wall. In

co-operation the seller, as a member of the society, appoints or controls,

or has controlling knowledge of the goods he offers at the counter, and

has no interest in cheating himself or the customers. The tradesman,

as a rule, is as honestly-minded as co-operators; but he cannot do all he

would. He is in a competitive system, in which the interest of the

dealer is first—the interest of the buyer second. The co-operator

is outside the competitive system. He is a member of another

system—quite different, in which "Each is for all and all for each"—and

no private interest has to be consulted. In true co-operation no one

benefits at the expense of others. All this is new trading, quite

the reverse of the old system. If anyone wants to see what the new

system of trading does for its customers, let him go to New Normanton;

there, five streets have been built by the store. All those

prosperous streets are owned by its customers, and owned because they have

been its customers.

The co-operator is pledged by his rules, to disclose to the purchaser

anything he knows to the disadvantage of what he offers for sale. If this

were done by those who conduct business on the old method of trading, half

the shops in every large town would have to be closed in six months. The

new trade educates its customers in the nature of commodities, so that

they may know what to buy. Do the old trade dealers do this?

The two principles recognised by the new system are participation and

education. They are quite outside the range of the old form of trade. Not

only do the purchasers at the

store share the profits, but the workers do. Participation of profit with

labour and trade; to use the language of the new South African

diplomacy—is the one principle which has

"paramountcy" in co-operation. The store is founded upon it. By mere wages

all that can be commanded is the ordinary service rendered for wages. But

a man has more to sell than

his labour. He has his skill, his goodwill, and his capacity for economy. Co-operation buys these. In the labour market of old trade nothing is

given for these profitable qualities. Where profit is accorded, there is a

claim upon their skill, goodwill, and active interests of all shop-servers

and workers. Sometimes, those who are accorded participation in gains take

it as a matter of course, and do not concern themselves, or make any

special effort to promote the prosperity of the society. Upon such persons

participation is thrown away, and they would have no right of complaint if

they found themselves exchanged for other workers, with better discernment

and a livelier appreciation of principle; for no one owes consideration to

those who show no consideration for others.

The amount of profit depends upon the sum taken in the shop, and the small

amount of leakage made in distribution. The persons who share profits in

the Derby Society include all who serve behind the counter, the grocers,

the meat tender, the drapers, the boot and shoemakers at the bench, and in

the painting and hardware shops. In the Coal Department, the

draymen who go about the streets with coal have a rate per ton. In the

winter they earn £2. 3s. and even £2. 5s. a week. In the bakehouse the men

have a rate per bag, and the total earned per week is divided according to

wages. This is substantially profit-sharing, and is conceded as a right

and as a reward for assiduity and intelligence.

Liberty was a "bonus" in England in the days of the Plantagenets,

revocable at the pleasure of the ruler. It is now a right of every man, as

profit is in true co-operation the right

of all who work by hand or brain. A certain portion of such earnings are

deposited with the society to accumulate as a provision for domestic exigence, or old age pension. The Romans discovered that labour extracted

by fear and slaughter, by torture, or intrigue, was slovenly and

insufficient, and they gave the cultivator an interest in the amount and

quality of his work.

Profit on service was first conceded to employees in 1883. There was no

resistance to it, or conflict about it. The good sense of the committee

proposed it, and the good sense of the members sustained it. Now for

examples of what this participation in profits, conceded by the Derby

Society, means. The coal trade, in the year 1885, received £101; the men

in the Grocery and Meat Departments received £136 in addition to their

ordinary wages.

During the past six years, 1894 to 1900, the amount of profit given to

shopmen is £4,382 over and above their wages.

It may be said that in many businesses, foremen and superintendents are

given a commission on profits made in their departments. This is true. But

the commission given is not a reward so much for their superior skill, but

as an inducement to get more work for less wages from those

they engage or overlook. What these heads of departments

gain the workmen lose. It is not in this way, nor in this spirit, that the

new trade acts.

Such are the advantages of the new trade, which is out of the range of the

old trade. But there is another and greater yet, and that is education. Though education stands second here among the features of the store, it

might stand

first from its importance. Hutton, the historian of the town, tells us

that in his day there was no education to be had in Derby for youths of

his class. The first Sunday School Society was not founded until 1785, six

years before Hutton

published his "History of Derby." [8] This society had

two earnest champions—Rowland Hill, the father of Sir Rowland of

Post-office renown, and Mrs. Hannah More, a famous authoress in her time. She was considered a pioneer of elementary education for the people. She

confined her curriculum to "the Bible and the Catechism and such coarse

work as may fit the children for servants." "I allow," she

says, "no writing for the poor." The poor Derby youth who under such

disadvantages made a name for himself in literature showed there was

energy and capacity in the Derby blood.

There are many who would not like to be thought enemies of education, and

they sometimes believe they are its friends, yet in their hearts they care

very little for it, and have no idea that knowledge is utility as well as

pleasure. They think

they know enough as it is. That is because they do not know how little

they know.

Freaks of intellect are as many and as entertaining as the freaks in

Barnum and Bailey's Show, though it is not possible to embody and exhibit

mental eccentricities. Some have crooked souls. They cannot think

straight, nor see straight, nor speak straight, nor walk straight, nor act

straight. Many men talk like philosophers and live like fools, but they

are not genuine idiots—only parrot philosophers. Philosophy has got into

their heads but not into their hearts, and not at all into their pockets. There are some societies which provide for knowledge as though it were a

charity, or a poor relation who could not take care of itself, whereas

knowledge is a King, and the only power which enables the lame to walk,

and the blind to see, and the impotent to act. Ignorance gives a sort of

eternity to prejudice, and perpetuity to error, and as the thoughtful

pioneers found that prejudice and error were obstacles in their way which

only education could remove, they wisely provided for it.

The advocates of the new trade in Derby early understood this. Education

was started in 1864. The society had the Old Assembly Room in Full Street,

adjoining the secretary's office, which was used as a reading-room. It had

seven news papers and a few weekly and monthly periodicals. It was free

to members. From 1877 votes were given for education and

continue to the present time. It was this faculty of intelligent

discernment which caused them to make an early minute, "That we rent a

reading-room at Full Street for the use of members from the Rev. Erskine

Clarke and H. Holmes." At a committee meeting on New Year's Day, 1868

(thirty-two years ago), they determined "to hold a public meeting at the

opening of the reading-room, and Mr. Oldham and Mr. Smith

were to solicit the Mayor to preside on the occasion." What made them do

this unless they saw that intelligence was a co-operative necessity. In

1876, twenty-four years ago, a reading-room was opened in High Street,

which was continued until the premises were taken down for a new building

on the

site. Soon after a library, well-selected, was opened for the use of

members. The educational committee knew that education was a co-operative

helper. Knowledge is power, as those know who have it. But as the Bishop

of London told us at Peterborough, many forget that "ignorance is

impotence."

Being of this opinion the Derby Society endowed their educational

committee with an income of 1 per cent of their total profits. This is

what the new trade store-keepers do. Where are the old trade shop-keepers

in our streets who do the like?

Characteristics of the Derby Society.

CHAPTER XX.

WE might call this chapter Ethical Characteristics, did there not seem to

lie in the phrase a pretention of moral perfection which, though a good

thing to aim at, is not modest to assume on this side of the millennium. Co-operators are not desirous of being classed among the goody good

people, who, as a rule, are not good for much. What co-operators stand up

for and profess, is a manly

honesty in contracts, statements, and trade. Their principles of

co-operation imply not only good-will, but as we have said, fair

participation of benefits with all who join them, and they,

as a rule, keep the contract. In statements, or profession, they, in the

main, say what they mean and mean what they say. In trade they can be

trusted for genuineness in

commodities, as far as care can compass it. Justness of weight or measure

are within every honest man's power. Excellence of material and

workmanship in articles of manufacture are their constant aim. This is

good every day trade morality, as trade goes, and better than a good deal

that is known to go, under the system of irresponsible competition. In its

earliest days co-operators believed that honesty would

pay, when not many persons in business did believe it. They accepted the

Latin maxim: "There is no expediency without honesty."

This Jubilee History, which is now drawing to a close, does not include

everything pertinent to it, from fear of its being too long for its

purpose, which purpose is that it shall be read, and not weary the reader. It is better to hear it said the book might be longer, than that the

reader should say it had been better had it been shorter.

The reader may find incidental repetitions, which if they do not chafe,

are serviceable, inasmuch as they save him from going back for references. Repetitions maybe tiresome, but obscurity is irritating. However, setting

the same things in new lights, is not repetition, but illustration and

confirmation. In a narrative of this kind the main thing is authenticity,

to secure which no pains have been spared. It is far easier to write

fiction than history. Verification of facts takes time and labour. Hours

may be spent in searching for a date, which when found, adds only two or

three figures to the page. Their presence lends confidence to the history,

though there is very little to show for it. In fiction the author can

invent his facts,

in history he has to find them. Of things unsaid it will occur to some,

that mention might have been made in the chapter on the town of Derby,

that Mr. Herbert Spencer, who has long stood in the first rank of great

thinkers, was the son of a Derby school teacher, and who lately made

important co-operative suggestions.

Among the curiosities of the "Early Records," the subject of an earlier

chapter, there are other instances than those cited. Here is one. At a

committee meeting on April 18th, 1865, it was gravely resolved—"That no

order be given to any traveller in his presence." How can an order be

given to anyone out

of his presence? Where is he when he is not present? An order may be sent

to him but cannot be given to him, unless he is present to receive it. But

when the centenary of the Derby Society comes to be written, fifty years

hence, historians of that day will find a mine of peculiarities in the

minute books, and will thank us for our consideration in having left so

much for their recital.

Though there is no evidence that the carpenters and joiners of George

Yard, knew much, if anything, of Robert Owen, those who afterwards carried

the store movement forward did. Robert Owen had been a frequent visitor to

Derby, being an intimate friend of the Strutt family. He had also

addressed audiences in the town. On one occasion he called on Mrs. Hagen,

the Quakeress, of whom mention has been made. Seeing a portrait of

himself on the wall, he asked her if she knew Robert Owen. Turning

to the picture and then to her visitor, she said in her quick way, "Why,

thou art Robert Owen." The principles which the great Apostle

of Social Ideas in England inculcated, and which became the

characteristics of the Derby Society, were few and clear. They were

these:—

1. Truth in speech, without which nobody will believe us.

2. Honesty in transaction, without which custom in our stores cannot be

retained.

3. Unity by fraternity, without which no unity is real.

4. Equity in according the gain everywhere among those whose diligence and

vigilance help to produce it.

It has been by these principles and the beneficial results which have

flowed from their application, which so many have shared, that the Derby

Society has won its 14,000 members. In one of Shakspere's most

suggestive passages he says:—

|

"Each in his own hand bears

The means to cancel his captivity." |

The Derby Society, by bearing aloft, for half a century, the standard of

co-operation, has caused the humblest member to know that he carries

within himself the golden "means" of

social extrication. Each can, at will, cancel industrial captivity, if he

has self-help in his hands and self-reliance in mind. Independence and

betterment of social condition lie that way.

In the early part of the last century industry was one vast mist, often

submerged by an obscuring sea of hopelessness. At the close of this

century, at least three headlands stand

out—Rochdale, Leeds, and Derby Co-operative Societies, each with half a

century of durability, and others, as at Hebden Bridge, showing that dry

land is appearing where labour may take refuge and live. It is the

diffusion of intelligence which has wrought the great change, by making

co-operation possible. So long as men thought there was nothing in

knowledge, there

was no progress. The Derby Society has been fortunate in its members, else

it had never attained its present ascendancy. Yet, in every society in the

land its committee of management could have done twice as much as they

have, had its members been twice as wise as they were. Co-operation is in

its

infancy. All pioneers are retarded by persons who do not see far before

them. A man who thinks he knows everything

does not know that all about him know he does not. Such persons forget

that, while they may appear wise to those who know less than themselves,

and pass for intelligent among those who know no more than themselves,

they can never conceal their ignorance from those who are better informed.

No art can hide poverty of mind, but by means of education every man can

enrich himself at will, and every person needs to be rich in knowledge who

expects to make his way successfully through the world. The pioneers of

Full Street had night-bird eyes, for they foresaw the Albert Street

Stores, altogether invisible to compeers of their day.

Who has depicted the value of education to co-operators and others as

Huxley has done? Let the reader pause for a moment over his brilliant and

burning words.

"Suppose," he says, "that it were perfectly certain that the life and

fortune of every one of us would, one day or other, depend upon his

winning or losing a game at chess. Don't you think that we should all

consider it to be a primary duty to learn at least the names and the moves

of the pieces; to have a notion of a gambit, and a keen eye for all the

means of giving and getting out of check? Do you not think that we should

look with a disapprobation amounting to scorn, upon the father who allowed

his son, or the State which allowed its members, to grow up without

knowing a pawn from a knight?

"Yet it is a very plain and elementary truth, that the life, the fortune,

and the happiness of every one of us, and, more or less, of those who are

connected with us, do depend upon our knowing something of the rules of a

game infinitely more difficult than chess. It is a game which has been

played for untold ages, every man and woman of us being one of the two

players in a game of his or her own. The chess board is the world, the

pieces are the phenomena of the universe, the rules of the game are what

we call the laws of Nature. The player

on the other side is hidden from us. We know that his play

is always fair, just, and patient. But also we know, to our cost, that he

never overlooks a mistake, or makes the smallest allowance for ignorance. To the man who plays well, the highest stakes are paid, with that sort of

overflowing generosity with which the strong shows delight in strength. And one who plays ill is checkmated, without haste, but without remorse." [9] The education the society is interested in is not only the education of

the citizen, important as that is, but the education of the co-operator in

the essential principles he professes and endeavours to extend. "A man is

ignorant," says Bishop Tenison, "whatever he may know who does not know

that which he ought to know and professes to know." The Derby Society will

always have honour for its endeavour to impart this knowledge to its

members.

But there is no reason to linger longer over incidents and principles that

have intrinsic instruction in them. A writer, like a speaker, should know

when to give over. A laboured peroration adds nothing to the force of a

speech or the dignity of a narrative, and may efface its impression. John

Stuart Mill tells us that "eventually we may, through the co-operative

principle, see our way to a change in society, which would combine the

freedom and independence of the individual with the moral, intellectual,

and economical advantages of aggregate production." Already co-operation,

like electricity, has become a new power in the commercial world,

irradiating the paths which lead to the commonwealth of co-operative

labour—the radiant land of Equity, where Justice is not blind, but seeing

and protective.

EVENING ON THE

DERWENT, DERBY.

Co-operation may be likened to the Derwent, which flows noiselessly but

unceasingly through the fields of industry, fertilising the banks made

bare and barren by arid and impoverishing competition.

Therefore, at this jubilee time we may say in the words (changing only

one) of William Morris, who devoted his art, his wealth, his genius, and

his poesy to accomplish similar ends of human betterance—

Come then, let us cast off doubting and put by ease and rest,

For the cause alone is worthy till the good days bring the best.

Ah! come, cast off all doubting, for this at least we know,

That the dawn of the day is coming, and forth the banners go. |

NOTICE BY COMMITTEE OF

MANAGEMENT

________________

ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF THE

JUBILEE

IN JULY.

________________

Of the History of the Society, written by Mr. G. J. Holyoake, assisted by

Mr. A. Scotton, 14,000 copies are being printed, and 14,000 teapots are

being made at Brownfield's Pottery, Stoke-on-Trent, one of which, with a

copy of the History, we propose to present to each member.

The Co-operative Wholesale Society have promised to send a large Jubilee

Cake, which will be exhibited in one of the shop windows in Albert Street,

and afterwards given away.

It is also intended to give the Penny Bank children a treat, during July,

and to present each one with a medal.

________________

NOTES.

8. The copy in the Free Library was published in 1791,

and is now 109 years old.

9. Huxley's Essay on "A Liberal Education."

MANCHESTER:

PRINTED BY THE CO-OPERATIVE

PRINTING

SOCIETY LIMITED,

118, CORPORATION STREET. |