|

[Previous

Page]

The Departments.

CHAPTER XI.

IT is now time to give some information concerning

the rise and growth of the Departments of the Society. A store will

not generally grow unless somebody makes it. A department grows of

itself. When stores arise they soon acquire appetites, and have to

be fed. This implies a commissariat, and a commissariat has several

departments. We enumerate, as follow, the principal ones.

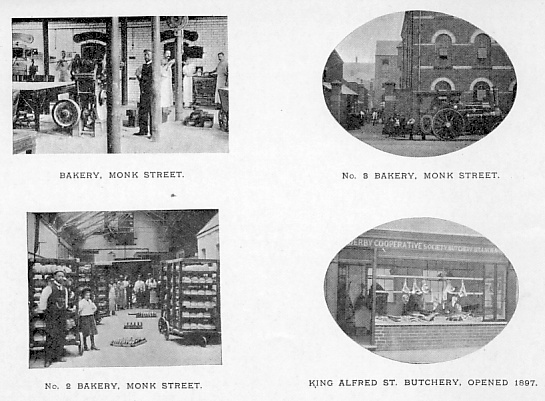

1. BAKERY.—Pledged to provide pure food, to the utmost of their

ability, as well as guarantee honesty in measure, the Derby co-operators

were always conscientious in their endeavours to fulfil these conditions.

It is this pledge and this care which have been the strength and

allurement of co-operative custom. In the rapacity and deception of

competition, which, though not universal, is so general that the customer

in the street is often uncertain into which shop to turn. Care taken

in ascertaining the qualities of whatever was sold to the members was,

from the beginning, a feature of the Derby Society.

In earlier years, at Park Street, the precaution was taken of

having samples of bread made from different kinds of flour, when the

directors resolved themselves into a Tasting Committee, and decided from

which flour their bread should be baked. We have seen that the

ingredients to be used in cakes, baked for festive parties, were carefully

considered in committee, and their proportions decided upon. In the

committee-room of the society a visitor saw, 35 years later, large buckets

of good-looking bread on trial, baked from seven kinds of flour. The

loaves were sent there from Monk Street Bakery, for tasting by the

managing committee, showing that unto 1899 there had been no remission in

this creditable precaution and care.

In 1861 (and for some years later) there existed a "Bread and

Flour Society" at the bottom of St. Mary's Gate, and the co-operators were

naturally drawn to it. But as it did not fulfil the conditions they

thought desirable, they therefore (November 29th, 1861) came to the

conclusion "That its productions were not satisfactory, and recommended to

the quarterly meeting the necessity of throwing the orders open to the

public." In January of the following year (1862) the committee

resolved to advertise for bread, and to give the Flour Society due notice

to discontinue sending any further supply. Private bakers were tried

for a time, as some of the committee were timid of taking any forward

movement. With present-day experience, it is amusing to notice how

hesitatingly the committee moved onwards. It was not until the end

of the year (December 25th, 1862) that they made up their minds to take a

bakehouse in Canal Street, at the rent of 1s. 6d. a week. Certainly,

the risk was sufficiently limited to allay the perturbations of the most

anxious. A baker was engaged at 18s. a week, and the society began

to make its own bread. This could hardly do otherwise than prove a

paying step, seeing the society had then three stores (viz.: Full Street,

Park Street, and Nun Street). In January, 1863, it was proposed "That a

man be spared from Park Street to take the bread to the other stores." The

bread trade could not help but increase as the members of the store

increased, and in January, 1865, the committee appeared with a virgin

flush of courage in their faces at a quarterly meeting, which resolved

upon erecting a bakehouse at the Park Street Store. Mr. T. R. Brown had

part in the erection of the first bakehouse owned by the society. By 1869

intrepidity had become ambition, and in June of that year the question was

raised as to the desirability of more central premises. Thirty-two votes

being given in favour of this proposition, and thirty-one against it, the

question was therefore adjourned to a special meeting, at which it was

decided to buy land in Albert Street, where a bakery could be made.

The Albert Street premises, as the reader knows, were opened in 1871. The bakehouse was constructed in the basement, which extended under the

present restaurant and boot shop. Ultimately, the Monk Street Bakery was

erected and superseded all others. The early co-operators were well among

the abbeys, nuns, and monks, having stores in streets of those names. The

society was beginning to see by electricity now, when they built their

bakery in Monk Street and started it with six continuous ovens, which were

the wonder of the members. They soon had at work a new Lindop machine,

capable of mixing 220 sacks of flour a day. They built large warehouses

for stocking flour, with flour hoist, steam engine, piggeries (never to be

left out of mind) at suitable distances, residence for the foreman. A

patent centrifugal dough-kneading machine was in due time fixed in the bakehouse. It was adopted from the increased demand for bread, and also

because it superseded the plan of mixing by hand, another instance in

which machinery ministers to purity, as the ballot box did to political

morality. Mr. Abbott is the efficient foreman of the

bakery. The great bakehouse fulfils the essential conditions

of convenience and cleanliness. There are bath-rooms and dressing-rooms

for the bakers, where the daily change of attire can be made. There are,

in fact, two distinct bakeries, each three storeys high, where 8,800

stones of bread are baked in one week. In one room there are ten ovens. There are oat-crushing and hay-chopping machinery, excellent stabling,

spacious and well ventilated; sanitary conditions being essential in every

place connected with the preparation of food.

The editor of the Monthly Record gave an interesting article on baking

ovens, which, he believed, came, like the wise men, from the East. Before

ovens were invented people had to cook like the gipsies, who put the

hedgehog, the hare, or the fowl they had "conveyed," in a coating of clay

and placed it on the fire. When the cooking was completed, feathers,

prickles, or fur came off easily, and the flavour was as perfect, as the

Emperor of China, according to Charles Lamb, found roast pig cooked by

burning down a house. The Monk Street Bakery strikes a stranger as a very

large structure, which, with the builder's yard adjoining it, occupies

nearly a whole side of a street of considerable length.

A Corn Mill was established in Leicester, 1877, by the federative aid of

several surrounding co-operative societies, the

chief of which was Derby. As it was financed by co-operative societies it

was called a "Co-operative" Corn Mill, but not in the sense in which a

store is co-operative—since it gave the workpeople no interest in its

prosperity. The enterprise of the Derby Store in co-operative endeavour,

is shown in the fact that they became a large shareholder in the "Midland

Federal Mill," besides making a loan of £1,000 to it. The engine and

shafts were of the best quality, and were supplied from the works of

Josiah Gimson and Co., large engineers of Leicester, at a cost of £2,250. The total cost of the mill was near £12,000. At the annual meeting, 1878,

Mr. Amos Scotton, president of this Midland Federal Mill, was presented

with a copy of "Old England's Worthies" by the educational department

of the

Leicester Co-operative Society. It seems that now and again societies act

pretty much like individuals, and sometimes fail to support their own

business, in store, or mill. Mr. Scotton resigned his presidency because

of what he regarded an illegal

action on the part of the committee. Whether the mill suffered by want of

enthusiasm on the part of its workers and managers, who, given no

co-operative interest in its welfare, is unknown. The Star Corn Mill at

Oldham, the Halifax, Sowerby Bridge, and others accorded no share of

profits to its servants. The reason usually assigned is that the workmen

are few and the capital employed is large, and no proportion can be

established. But the profits made by shareholders is always limited, and

it is easy to put all who labour in the mill on the same footing as

the shareholders. If there is the will there is the way. In the past year,

1899, the bread produce of Monk Street was equal to 1,664,000 quartern

loaves, and confectionery of the

value of £10,400. Everywhere an enterprising bakery creates delicacies for

the store and develops purveyor taste.

A bright store is the same to purchasers as the house

of call is to workmen, as David Urquhart designed Turkish Baths to be.

The brightness, cleanliness, and variety of things in a store, educate the

taste of the purchasers as well as proving inviting to them. This is

especially so where the dainty produce of the bakery is displayed.

An observing trade poet writes:—

|

"Of all the kinds of men there are,

The chemist is precisest far.

Though but a halfpenny you spend,

He treats you like his dearest friend

He stands beside his tiny light,

And hurries not a bit,

And folds the paper smooth and white,

And sealing—waxes it,

And hands it to you with the air

Of one who serves a millionaire." |

All this is as possible (where there is time for it) to the store keeper

as to the chemist. There is luckily not so great a demand for the

apprehensive drugs of the chemist, as for the happier commodities of the

store. Thus the store keeper has less time on his hands; but if taste be

in his heart and courtesy in his manners, he may make the purchase of the

glories of the bakery very exciting.

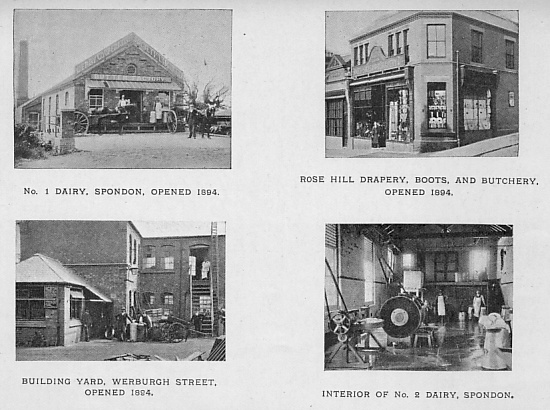

2. THE DAIRY.—Creamery is to some a prettier

name than dairy, though a dairymaid has unperishable charms. What is

more delightful than her spirited and sweet sauciness when crossing the

field with her milk pail? Her coxcomb wooer says—

|

"Then I can't marry you, my pretty maid."

"Nobody axed you, sir," she said. |

But creamery has a mellow, soothing, delicious sound. We read of a certain Jael who brought Sisera milk and butter in a lordly dish. The like can be

had at the Spondon Dairy, without the nail and the hammer of Jael.

The society bought a creamery and land at Spondon in 1894. They have

planted a portion of the land with fruit trees. In their dairy there is to

be found the most modern machines with which to prepare its products. The

milk they purchase from the farmers, to whom they are good customers. In

the summer the dairy workers make from 900 to 1,000 lbs. of butter a week. The working plant they possess would enable them to turn out double the

quantity. There are not many societies in the movement making the amount

of butter they produce.

Dairying was counted quite a new departure when first commenced by

co-operative societies. It is fortunately spreading now, but in many

places it requires a large plant and

considerable resources. It can be better carried out by large farmers than

small ones. Societies, sure of a large consumption, are more likely to

succeed; but it depends greatly on management, the possession of dairy

knowledge, and knowledge of locality. The most active co-operators are

commonly

those of the artisan class, to whom dairy knowledge is much unknown. Meat

selling was at once successful in Sheerness, 80 years ago; while many

stores since, as in Rochdale, for instance, it took a long time, and

encountered many failures before the directors there succeeded in making

the meat department pay. Dairying, as a rule, has many difficulties, but

it will, doubtless, prove a profitable department to many stores, when the

difficulties are overcome. The Derby Society knew from the first how to

surmount them.

The society has two restaurants where much of its dairy produce is

sold—one in Albert Street, before referred to, opened in December, 1890,

and one attached to the London Road Store—opened in January, 1899, near

the Midland Railway Works. It is filled for breakfast and dinner by their

workmen. The dining-room is spacious, convenient, and cheerful, and a

credit to the store.

At the Spondon Dairy the butter is made which is supplied to the store. The value of the dairy plant is £2,450. The year's produce for 1899 was in

value £5,533. The produce is sent to the society's shops and sold to the

members—milk is obtained from the farmers by contract.

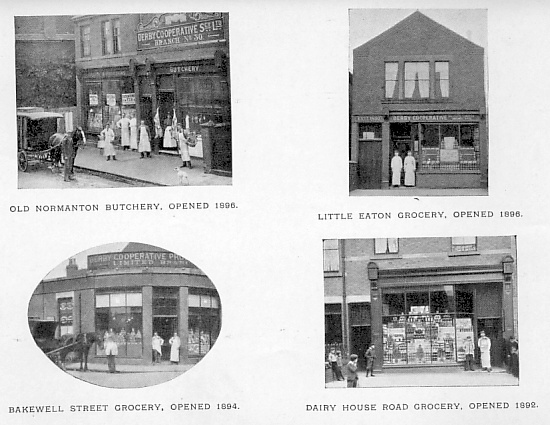

3. THE MEAT DEPARTMENT.—After what the reader has seen related in earlier

chapters, he will conclude that a Pork Preparing Department was very early

in the mind of the committee.

The art of buying is very different from the art of selling. To sell, all

one has to do is to find out what a customer will like, when he gets it. The art of buying consists in finding out what he ought to like from its

excellence. The committee very early (April 2nd, 1873) had practical

notions on this business, and gave instructions that, "when secretary and

superintendent go to market with the meat buyers, they must first deliver

to them, in writing, the number of beasts, or other animals to be bought." A necessary instruction, and in its day a prudent one. The market has its

ambitions and allurements which justify attention and precaution. Derby,

as visitors know, has a large cattle market. At the back of it are a large

number of abattoirs, owned by the Corporation. Abattoir is the French word

for "slaughter-house," which however inevitable, is not a scenic place,

which any reader wishes to have recalled, or to dwell upon. These

abattoirs can be rented, and the co-operative society holds three,

numbered 55, 67, and 74. These chambers are fitted up with every requisite

which humanity, sanitation, and business require. It has always been

counted a victory of management

in any society to make the sale of meat pay. Like dairying, it it needs

special knowledge, and experts are not easily found nor easily reared. The

success of the Derby managing

committee is seen in their last year's business. The number of animals

converted into food were, cattle, 1,341; calves, 143; sheep, 3,163; lambs,

240; pigs, 2,080; total, 6,967. Curing, mincing, and the various

preparations common to the meat trade, are parts of the society's

business. All things succulent are wholesome after their kind, save where

cereals and fruit are better.

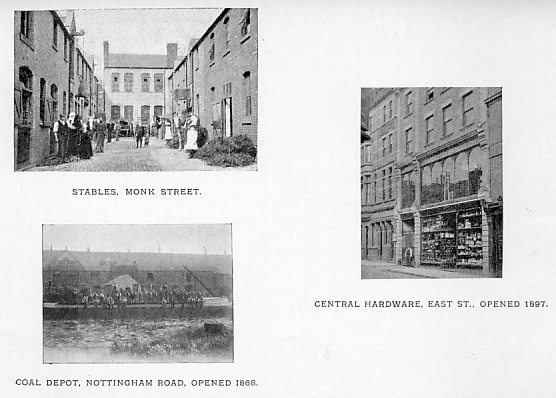

4. THE COAL TRADE.—Mr. George Iles in his remarkable work on "Flame,

Electricity, and the Camera," describes how familiarity with the affluent

use of coal, prevents our appreciating the origin of fire—the first

discovery of a new force in nature; a discovery which eventually changed

the whole aspect of the world and made society possible. A fireless world

is a savage world, and in Torrid and Arctic zones alike, man had to live

on raw meat or on field foods, cooking was impossible. The first savage

who made a flame by the friction of two sticks, put a new power into the

hands of man which made it possible to mould metals, create tools; and

afterwards by flame came steam. Coal itself was dead, until flame came to

ignite it, and give it universal life.

Coal, the ebony child of the Sun, has always been a popular subject of

barter. The society's coal trade was commenced in 1863, by a quaint

businesslike declaration, characteristic of the early providingness of the

co-operators, namely: "That we begin in the Coal trade, and members

wishing to have coal must pay into the store sums weekly, until sufficient

capital is raised, then the committee will advertise for the quantity

required, deposits to be made at the Stores on Mondays and Tuesdays."

Scattered records in the minutes show how the coal business grew. On "August 23rd, 1871, the rent of a wharf, and price of

land adjoining to be ascertained." On May 28th, 1873, another

coal boat has to be bought. "Mr. Rigby is to be written to, to learn the

price of his boat and when it may be inspected." Year by year the trade

expanded, boats, wagons, and horses

increased. In 1885 the sales of coal were over 14,000 tons.

The society has three coal depots, one at the City Road Railway Wharf, one

at the London Road Railway Wharf, and the third in Nottingham Road, which

is for barges only. All are busy with unloading barges, or starting wagons

on their daily and hourly journeys.

Better than in any detailed enumeration, the magnitude of the coal

department and the affluent possessions of the society, are shown in the

statement that there are four barges, 28 horses, and 36 wagons, and the

railway companies' wagons also used in the coal trade; and 44 workers,

besides casual assistants who are employed in emergencies of business. Horses abound—the society has 65 horses in all, including the coal with

other departments. The sale of coals yearly may be set down at

40,000 tons. For the year 1899 the amount was 39,953 tons.

Mr. Purcell is the indefatigable chief coal manager, who sends out weekly

500 bags of coal, each weighing 1 cwt. Drays are constantly going about

the town selling 1 cwt. sacks; and carts which deliver one or more tons at

the houses of members. In 1899 there were sold 595,500 sacks, representing

29,775 tons; also 10,168 tons in loads.

5. THE BUILDING SOCIETY.—Every department has its necessity and value, or

it would not exist. If there be one more important than another, in

far-reaching consequences, it

is that of building. Space, loftiness, light, ventilation, length of life,

and cheerfulness are in the builder's hands, nor can the tenant ever

escape from the influence of omissions in these respects, so long as he

remains the occupier of the tenement. Besides, if the house be unsightly,

it may affect the imagination and ideas of three generations of children,

who may reside opposite, if the house lasts for 100 years. Of course, what

the builder does is limited by the means of those for

whom the tenement is built. But builders can do much, if

they think of it. The houses erected by the building society are palaces

of sanitation and convenience, compared with what would have stood in

their place had the speculative builder put them up for profit. The

Building Department is a distinguished feature of the Co-operative

Society. It commenced in 1876 with the object of granting advances to

members to buy, or build, houses for themselves. A few years ago the

society itself started the business of builders, erecting houses for the

members, and also the store business premises. The society have for years

done painting houses and papering

rooms for members. They employ a large staff, and when the members pay for

work done they receive checks to that amount, and get the same dividend as

on their purchases in

the stores. The building department has not erected many of the stores,

but it built the freehold property of 51 blocks of

premises for business purposes, costing £81,040. It owns also 68 cottages,

which cost £14,479, and in addition it has advanced to members, since

1877, £220,000, so that the members, by paying easy instalments, become

the owners of their own houses, and on these instalments there is now

owing by members only £68,706, thus, the individual co-operators of Derby

are now the absolute owners of £151,294 worth of freehold property.

The Housing Question now occupies the attention of municipalities. From

figures recently obtained by Mr. J. C. Gray, it appears that 224

co-operative societies have built 7,956 houses, 16,082 have been built by

members, with the aid of money advanced to them by societies—the total of

co-operative houses built is therefore 24,038. The total cash advanced to

members has been £3,402,206, and the total worth of these co-operative

tenements is £5,147,526. These erections have been made under the best

sanitary arrangement which science could suggest, improving the taste, as

well as the health, of the occupiers. Life is longer, and diseases of

every description less frequent among the residents, than formerly was the

case in ordinary tenements.

When the society began street building in Derby, they gave names to the

new thoroughfares that left no doubt in the mind of any visitor that a

co-operative colony had settled there.

New Normanton is a populous suburb of Derby, composed mostly of new

streets, of which five have been built by the co-operators. Derby Street

tells its own story. Industrial Street has self-help in every syllable. Provident Street implies the thoroughfare of thrift. Co-operative Street

has unity in its name, while Society Place joins Co-operative Street and

Industrial Street together. The whole constitute the title of

the "Derby Co-operative Provident Industrial Society." It is

a real beehive town in which no drones are to be found. In Kelley's and

other directories into which the reader may look, these streets with their

unprecedented names are duly recorded.

When houses were erected the society wisely claimed the right of

citizenship for the tenants. It was objected that the occupant could not

vote until he had entirely paid for the

house. The members claimed to be owners of the properties as soon as they

obtained possession of them, and so long as they made their contract

payments for them, according to the society's rules. While they continued

their payments no one could turn them out (not even the society). They

were owners by contract, and the judge conceded the validity of the

argument, and thus the tenants were put upon the list of Parliamentary

voters.

A member who owned two freehold houses, one of which he let, could claim a

borough vote for the one in which he resided, and the county vote by

reason of being the owner of the freehold of another house. All this seems

simple enough now, but there was a time when it seemed both complex and

contestable, and it says much for the sagacity and perseverance of the

committee, that they established these claims on behalf

of their tenants. The claim made some noise in Derby of its day, it being

of local interest and also of interest to co-operative societies

elsewhere. The case was decided in the County Revision Court by the

Revising Barrister, Mr. Etherington Smith. The claimants were Frederick Hickingbottom, John Harber, Amos Scotton, Henry Pridgeon, and Joseph

Jepson, who claimed to be on the register in respect of freehold land;

they being all members of the Derby Provident Society, their claim was not

likely to go unquestioned. Indeed, the case was three times adjourned. Mr.

William Cooper, the Liberal agent, defended the claim with force and

clearness. Mr. Holland, for the Conservatives, was fertile in technical

and other objections. For instance, he cited Rule XX., relating to the

government of the co-operative society, dealing with property belonging to

a lunatic. Whether he thought membership of the society implied lunacy, or

whether the claimant of

a freehold vote was a lunatic, was not made plain. During a discussion of

two hours every element of legal confusion was let loose, as is generally

the manner of Conservative agents; the Revising Barrister, who had been in

many technical mists before, saw his way to allowing the claim, which has

never since been disputed.

The society has no vote for any of its property anywhere, as a society

cannot vote in its corporate capacity. It holds

shares in the railway company and it can send one of its members to vote

for it at half-yearly, or other meetings. There are many other societies,

who do not, but might, hold railway shares, and thus extend their

influence where it is sometimes an advantage to have influence. Before

house building became a popular part of co-operative enterprise, Mr. Scotton wrote a paper upon the subject, which was afterwards published as

a pamphlet by the Co-operative Union, and was thought to have considerable

influence in turning the attention of societies in

this important direction. In 1893, building operations took a

more determined, or more official form. A building yard was

opened, the same as at Leeds. Since when, stores have been erected for the

society, or tenements for members. At the present time they employ

bricklayers, joiners, plumbers, and labourers, 65 workmen in all. There is

also a separate

department for painting and paper-hanging. This department employs an

average of 22 men; here also checks are given and dividends paid on all

work done, an original and consistent device not elsewhere in operation,

so far as is known. Certainly it is not commonly done.

The staff of workmen employed by this society are constantly engaged in

building houses and allotting them to members for purchase by easy

payments. Checks are not

given on these payments made for the purchase of the tenement, but if any

of the 14,000 members give orders to the building department for painting

and paper-hanging, checks are given upon these bills when paid at the

office, just as on store purchases.

The Monthly Manifesto.

CHAPTER XII.

THE literary history of the society may be read in

the pages of the Monthly Record, which might be called the Monthly

Manifesto of the Industrial Co-operative Association which it represents.

In August, 1876, it was resolved to bring out a Co-operative Record,

the first number was to appear in September, and to be printed by William

Hall. The choice of editor fell on Mr. A. Scotton. A Monthly

Magazine, or Herald, or Journal, or Record, or Reporter of some kind, is

indispensable to a growing society. It is the local flag of the

cause, the standard of the party, and though a flag of industrial peace,

it is as worthy of pride and defence as a destructive flag of war.

The motto of the Monthly Record is a pair of hands

joined together, accompanied by the legend, "Unity and success go

hand-in-hand." Still, it is ever desirable to understand what the

"unity" is about. Good sense and honest purpose should dictate the object of

unity. Unity, like intelligence, is only excellent provided it is applied

to a good purpose. Intelligence in contriving evil merely makes men into

demons; but if exercised in compassing noble ends, it commands the

admiration of mankind. So, unity depends for its merit upon the object for

which persons unite. Knaves can unite as well as honest men, but the unity

of knaves, or mere speculators, forestallers, or corner-men, is

pestilential. Hence the necessity of Co-operative Records maintaining the

advocacy, by pen or speech, which may inform members that unity is not a

thing

standing alone, it must have honest purposes, noble aims, and justifiable

objects. Then, when men mean well, the more unity there is among them the

better. Right aims are the essential conditions of human effort, and unity

is, as Bishop Hall would say, a silken cord, which runs through the pearl

chain of high aspirations, binding them in sheaves of the golden grain of

progress.

Though Co-operation means combined action, and necessarily looks forward

to its success—the impulse which leads to it is individual. "It is most

astonishing"—exclaims

the editor, in an early number (September 1877)—"that the bulk of the

working class take no thought of the morrow. They most need this

preparation for the future and consider it the least." Prudence is seldom

instinctive, it is the child of reflection. It is a new sense which the

thoughtless do not

possess. It is a merit in the Record that the editor seeks to create it. His words are

"We say it advisedly, the help must come from within; it

cannot come from without, for no government in the world, however wise its

laws, or however impartially those laws may be administered, will ever be

able to raise the man who has no desire to raise himself. It is precisely

this sense of self-reliance which co-operation teaches." All this is

excellently said, and what is said is well known to all reformers; but it

needs many repetitions and much attention from educational committees. To

inspire the sense of self-help is mainly their business.

The value of a Monthly Record is that it enables the committee to

communicate with the members when it cannot meet them personally. It

furnishes the members with opportunities of expressing opinions and making

suggestions, who might not find the opportunity of doing it at quarterly

meetings, or who might shrink from the publicity of doing it if a relevant

opportunity occurred. Besides, an observing editor can make it the medium

of bringing before the members instances of outside action against them,

or of local opinion against them, desirable for them to know, and of which

otherwise they might remain ignorant and supine when they should be alert. Extracts from speeches in Parliament—speeches by prelates and notable

persons and the citation of facts of interest may be made, which would

engage the

curiosity and attention at the fireside of the members. News of the

proceedings of other co-operative societies, as well as the

progress of their own, renders the periodical record a means of comparison

of methods and improvement in advocacy. The bird that flies through the

castle hall, as the chieftain and warriors sit at table, and out of an

opposite window into the darkness, leaves a trail of light behind it,

telling of life and freedom elsewhere, which, though transient, awakens

thought.

The editor in the first number gave a declaration of co-operative policy.

He said:—"The Record was intended to be the means of spreading among the

members clearer views of co-operative truth than the new adherents would

be likely

to entertain. Co-operation meant more than an organisation

for obtaining dividends. Present and immediate gain was the first result

of the simplest form of co-operation, whereas co-operation is one of the

most important movements which is daily proving its principles to be

applicable to every department of social and industrial life."

The Record which was commenced, as we have said, in 1876, was edited for

sixteen years by Mr. Scotton. He vacated his editorial chair in August,

1892. He was voted £10 at a quarterly meeting in consideration of his

lengthened service, which amounted to a trifle over twelve shillings a

year, or one shilling a month. Considering the quality and quantity of

writing done in the way of articles, and of prevision and revision of

correspondence, it must be admitted that it was very moderate pay. Since

that time and up to the present, the Record has been conducted by the

educational committee, who receive no remuneration. 2,500 copies were

printed of

the first number. The Educational Fund was never large in those days, and

giving the number away made that little less,

and little could be afforded for conducting the paper. But the Educational

Fund ought to be large enough to afford remuneration to those whose time,

labour, and intelligence are confiscated in the interests of the society.

The conduct of the Record from the first showed that the editor possessed

real co-operative knowledge, understood its principles, both distributive

and productive. He showed that he cared alike for material and ethical

welfare; it had equity in its head and fraternity in its spirit. In the

second number of the Record he said:—"Labour's day of emancipation would

come when co-operative production was as generally adopted as co-operative

distribution is now. Then EQUITY and TRUTH will prevail in all business

transactions,"

All this is said in happy phrases. Nor was this vague evasion; it was

definite, and meant to be so. He foresaw

what many do not see now. "What we want," he said, "is that the

accumulating capital of our societies should supply the means of

co-operative production, in which the worker can take his position not

only as a worker, but as a partner in the

responsibility and the profits." This was said before "Co-partnership" was

a recognised co-operative term. There are those who think that

co-operative productions are articles produced by persons known as

co-operators. But there is no co-operative production, save where the

producer has a share in the profits

as the capitalist and the consumer have. The editor of the Monthly Record

was not only a chronicler, he was a counsellor, who had principle in his

mind.

His first editorial dealt with work of the building committee, commending

to their care "the ventilation of the houses erected for members, which

should have lofty sleeping rooms"—a few feet more in elevation costs

little in the building, but means health and extension of life to the

inmates. The editor next reminds members that they can, by means of the

store, provide themselves with houses. "Many members" he observed "had

paid for their houses over and over again,

and not a brick do they own." A co-operative township has arisen out of

this trenchant advice.

Another thing which the editor, like Mr. Hilliard, seemed to have always

at heart, was the prosperity of the Penny Bank. This is a branch for the

formation of character which the smallest society is able to cultivate,

and which no society can afford to neglect. To create the habit of thrift

is to put a small fortune in the way of the child, for in after years when

more money comes through his hands, the habit of

saving is an endowment. The first missionary book the writer read, was a

Wesleyan Magazine published at the end of the last century, it told a

story of what occurred in a merchant's

office, which he passed every day. It therefore impressed itself on the

memory. Two mission collectors called upon the

merchant to ask him for a contribution. While waiting, in an outer room

their turn to go in, they overheard the merchant

scolding a servant who had wasted a match. "It is no use waiting here,"

said one to the other, "we shall not get much from a man who thinks so

much of a lost match, we had better go." "However," said the other, "as

we have sent in our

names we had better see the gentleman who will wonder at our unexplained

departure." They went in and on hearing that they wished a subscription

for the Wesleyan Mission, "Oh! yes," he said, "I will give you ten

pounds." They gasped with astonishment, or made some noticeable sign of

wonder. The merchant asked why they seemed surprised, and they then "owned up" that when they heard him reproaching a servant for wasting a

match they had concluded they would get nothing from him. "Ah!

gentlemen," he replied, "if I had not taken care of my matches, I should

not have ten pounds to give you."

An instance is given in No. 6 of the Record, that new branches were opened

at times, on what may be described as upon public invitation. For

instance, a requisition was sent in to the committee, signed by more than

sixty inhabitants, asking that a branch store be opened in the New Zealand

and Ashbourne Road district. At other times correspondents point out

places where a new store would succeed. Members seem to have joined the

committee in the pursuit of branch-founding.

In an early number, the editor gives a Bunyan-like dialogue on a dividend

day. The characters are managed with considerable skill. Mrs. Grateful, Mr. Prudent, Mrs. Slow-to-think, and others,

whose quality of mind is indicated by their names, take part in an

interesting debate. The originality, the native quaintness, and the

polished brevity of the great Bedford Tinker is not a common endowment,

but the co-operative dialogue on his model, is not wanting in humour and

relevance.

The reports of meetings and the speeches made, contain passages of wisdom

worth consulting again. The arguments with which co-operation was

sometimes confronted, and sometimes assisted, in different stages of its

progress, are curious and have instruction still. The society has passed

beyond those stages, and the old arguments have lost their savour. They

seem now flat, stale, and unprofitable, but they were valid in their day,

and are heard again in the formation of new societies by persons but newly

acquainted with the movement. It is wisdom ever to be patient with new

inquirers. What seems elementary and of no use to those advanced in

co-operative knowledge, is of cardinal importance to new thinkers.

In an early number of the Record, members were addressed on the importance

of capitalising dividends. There occurred in it a passage excellently

expressed and relevant to all stores

and to all time. The capitalising of dividends is urged in many persuasive

sentences. In this way, by the capitalising

of dividends, the opulence of stores has come about. While on the

continent stores are mostly rented, in England they are owned, and

frequently built, in what may be called, business splendour. It is the

capitalisation of dividends which

has done this. The wonder is that every member does not save his

dividends, as an investment, seeing that he acquired the capital without

effort and accumulates it without privation. He has only to buy at the

store, which is no more trouble than buying elsewhere, and there is no

effort in that. Seeing that he receives as large a quantity of provisions

of more certain quality than the private trader can usually afford to give

him, he therefore suffers no privation, while his savings increase.

Incidents of interest concerning branches have their place in the Record. Mention is made that when the new branch at Osmaston was opened, the

shopkeepers issued a placard, or handbill, against the store, such as have

been circulated elsewhere. Though sown broadcast, the spurious seed took

no root. It did the society no harm, for £70 were taken the first week. The public understood very well that when one tradesman thinks it

necessary to decry another, it is because the other is offering some

advantages to the public which the complaining tradesman is unable or

unprepared to give.

Pages of the Record are frequently varied by co-operative and other verse. The record of business is mostly monotonous save where it is triumphant. Details are often insipid to the general reader, until success imparts to

them a flavour, when they prove very welcome.

|

|

|

G. WOODHOUSE,

President. |

Verse is always a charm in a journal, and relieves the monotony of prosaic

facts. Not that facts are in themselves prosaic, they are sometimes full

of wonder. That, however, depends upon the reader being able to understand

them. All facts are not obvious in their import, and when their import is

seen they are far from being prosaic. Mr. Cobden had an idea that all

newspapers wanted were facts, and the Morning Star paid much attention to

facts, but it did not prove popular reading. Mr. Cobden's wide, practical

knowledge, and vigorous imagination saw a world of significance, which

little interested persons with less knowledge than he possessed. If facts

are explained when they are cited, so that the reader can see what the

writer sees in them, they command attention.

There is as much poetry in "Euclid" as in "Paradise Lost," but the two

kinds of poetry are very different in their nature. Poetry is new thought

of a noble or delightful kind, or some new aspect of a thought, illumined

by imagination, vividly expressed, measured, melodious, and memorable in

its terms. It is true magazine verse does not often reach this standard,

but it may convey useful ideas in a more beguiling manner than ordinary

prose.

The Record was constantly enlivened by co-operative verse, though its

material quality was never so conspicuous as to cause Tennyson, Browning,

or Sir Lewis Morris anxiety lest they be overshadowed. Nevertheless,

there is wisdom and pleasure in the lower regions of poetry; for

instance—"Snow Flake" verse such as appeared in the Record in 1890. "Snow Flake Co-operation" is a useful

and encouraging little poem. It is an argument in verse in favour of

persons of small means, and who think they have little influence,

combining together from the similitude of snow flakes, which singly appear

to make no impression, but multiplied and combined prove sufficient to

obstruct the movements of men, and even of railway engines. The grains of

sand, and even the leaves of trees become substantial forces in

combination, and even dewdrops have their uses. The summary of the

argument is:—

|

"And so the snow flakes grow to drifts,

The grains of sand to mountains,

The leaves become a pleasant shade,

And dewdrops fed the fountains." |

The "Bit of Land" is a co-operative poem, and is adapted to the taste of

honest rural ambition. It is an imitation of Mrs. Heman's favourite poem "Where is the Better Land?" the co-operative adapter shows how the plot of

land desired is found, situated in the Kingdom of Co-operation.

The late Mr. E. T. Craig, the first nonogenarian co-operator, was not a

poet by nature, though he sometimes wrote verse. He contributed to the

Record, January, 1880, a Christmas carol of the Leeds Society, which was

the best example of his co-operative views. It might be reprinted by any

store, with changes of name. It began:—

|

"In Derby Town they have a store,

That's selling fast, and trading more,

In things you wish to wear or eat,

From Boots and Shoes, to Bread and Meat." |

These lines are not imaginative nor novel in phrase, but they were

understood by that class of humble honest workers who most need the

commodities which are the subject of Mr. Craig's verse. Then the lines

proceed with an enumeration of the edibles manufactured, and, what is not

less important, the ethical treasures of the stores which are seldom

described in so small a compass. The concluding lines tell that the

Derby co-operators—

"Have raised a noble Public Hall,

Where science teaches truth to all,

These paths all workmen hence should know,

If wealth with social worth must grow.

The Lab'rer yet shall get his own

By self-employment—that alone

Will change the world, and haply then,

Bring peace on earth, goodwill to men!" |

We learn in February, 1889, in the Record, that "one of the tellers at

the annual meeting was named Samways." Derby Society is the only one

having a member of that name. Probably no member of the Sam Weller family,

though the original from which Dickens drew that character was a

co-operator well known in London. In the pages of the journal in question,

valuable and ample reports of the proceedings of Congresses and of the

proceedings at the Wholesale Society meetings by members deputed to attend

them, readers were kept well acquainted with the life of the movement.

Many things met with in its pages bring back to the mind valued aspects of

Derby long ago, when the first store was beginning to nestle in the George

Yard. At that time the writer was the guest of Mr. Hagen, the Quaker, and

his friends invited him to deliver lectures in the town. Hagen was himself

a centre of progressive ideas, and Mrs. Hagen was the smallest and most

fragile but the most animated little lady, Quakeress or otherwise, ever

known. She was smaller than Madame Pulzsky, the wife of Kossuth's Prime

Minister, and like her the little Quakeress had a soul on fire. Her

intrepidity of ideas gave a stranger the best impression possible then, of

intellectual vitality in Derby. The writer was a guest in her house when

he held debate with Dr. F. R. Lees. At that time temperance advocates took

no part in changing the social conditions of the people whose daily misery

in workshop and poor habitations made intemperance seem a relief to many.

Caring then, as he always cared, for social means of elevation, he

advocated co-operation as the most likely means to this end. Having in

view a parliamentary remedy for intemperance, the advocates of that day

not only distrusted, any other means of reducing the evil, but derided all

attempts that way. Every one sympathised with the sentiment expressed by

Charles Lamb, who said if men could see the effect of excess they would

|

"Close their lips and ne'er undo them,

To let the deep damnation trickle thro' them." |

While the suppressive remedy was in progress there was reason for using

every means of mitigating the evil. Temperance

policy has improved since the days of Dr. Lees in Derby. Sir Wilfrid

Lawson has been its good genius.

The Record, March, 1879, reports a lecture by the writer to co-operators

in the town; Mr. R. Hilliard presided. It is reported that he candidly

confessed that in earlier years he did not think that Derby had the

capacity of co-operation in it. Co-operation was defined as that policy of

conducting business, whether of distribution, manufacturing, mining, or

shipping enterprise, in which profits were equitably shared among all who,

by skill of thought, or by skill of hand, or patient labour, contributed

to produce them. He does not remember that

that number of the Record was ever sent to him. He read it with

unforeseen satisfaction for the first time on January 16th, 1900,

twenty-one years after its delivery.

There are two kinds of reporters, one who reproduces literally what you

say—sometimes a speaker does not desire to see again his exact words—and

another order of reporters who summarises what you say and gives the

entire sense, often in language of his own. Such a reporter must be to

some extent able to make the speech himself. The ingenious editor who

reported the speech must have known what the speaker intended to say, or

better still, what he ought to have said, and

took care that the report contained it. That is the kind of report a

speaker most values.

The manifesto of the society is a mine of facts to those who can test

their value. In the first February number a writer giving the familiar

initials of "A. S." cites the fact that cast iron sold at £1 per ton,

when converted by labour into ordinary machinery is worth £5 a ton; into

ornamental work, £45 a ton; into Berlin handicraft work, £660 a ton; into

metal

buttons, £5,896 a ton. This incited C. D. Badland, M.A., to leap to his

pen, and say that the capitalist helps to buy the

tools, and feed the workman. But what is the use of being an

M.A., if you can see no more than this? The capitalist merely risks his

money, and sleeps while it is doubled and tripled by the toil of others,

while labour contributes all its power and its life, and is lucky if he

dies in the workhouse, which the poor

law guardians begrudge him. Without labour, the capitalist's

money would go with him at last to where metal melts. At best, capital is

not more than the half brother of production, and labour, the other

brother, is entitled to at least half the profits of the joint

undertaking. So, in the contest between "A.S." and "M.A.," "two to one"

on "A.S." would be safe. In this journal of the " cause " these social

tournaments are fought out before the readers.

In 1887, the Record was increased to eight pages for two months. In the

Congress year it was increased to eight pages, and afterwards, with few

exceptions, it continued to be eight

pages. Later numbers have good quantity and quality in a coloured wrapper. It has grown with the society. It may be said to have been the means of

helping the society to grow. Like the society, it has increased in

importance and interest. On one occasion, the editor makes a vigorous

outspoken defence of the policy of welcoming all contributory thought in

the movement. All thought worth anything was free thought. Ideas of piety

and politics of the most divergent kinds, were to be found in co-operative

ranks. Individual freedom of conscience was never interfered with, and

seldom obtruded. Official recognition was given to none. Only the

principles of

co-operation were official. All personal beliefs of other kinds had equal

respect under the golden equality of toleration, which, ensures the unity

which is at once, strength and peace. It may be said in lines quoted by

the editor:—

"Man, some unwrought difference sees,

And speaks of high and low,

And worships those, and tramples these,

While the same path they go." |

[Next Page] |