|

[Previous

Page]

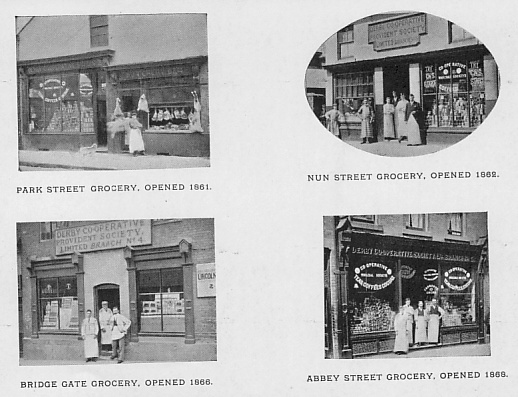

The Park Street Store.

CHAPTER VI.

|

|

|

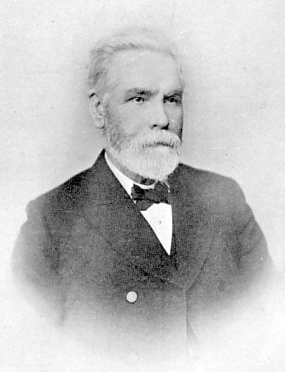

A. SCOTTON. |

LABOUR

HALL was a likely name to attract men whose object

was to raise the order of labour. It was a one storey, very plain,

conventicle-looking place. It had been used for humble purposes such

as its name implied. The entrance to it was up steps, though less

steep and rude than those of George Yard and Full Street. Victoria

Street was the only stepless store they had had. That was a ground

floor warehouse. For the first time the pioneers had now an entrance

from the street, and ranked so far with other shopkeepers, though their

customers had to climb steps, and they had no front windows in which to

show their goods. Indeed they had no wall windows at all, the

building being lighted from the roof. For the present, anyhow, they

had escaped from back yards. At the top of the steps a door opened

on to the hall floor. Underneath was a room of commensurate size,

used at times as a dancing-room. Such were the premises of the new

branch in a thoroughfare. The store remains there to this day, with

some few alterations to be hereafter indicated.

The reader has seen how the society became possessed of the

Labour Hall, and now held a freehold place of business. It was not

in good condition and needed repairs before occupation. These were

effected. It was fitted up in away befitting its modest pretension,

the work being done by members of the society after their regular day's

work was over. The first Branch was opened on Thursday, July 18th,

1861, but it was appointed to be opened on July 11th. It was ready a

week later, with regular paid servants, Mr. Hardy being shopman.

Business was done in ordinary hours, as in other shops in the town.

Mr. Scotton was appointed to assist at the opening, and felt a little

proud to be the taker of the first cash there. Afterwards he and Mr,

Swift were appointed to attend in the evenings to enrol members. The

place now ceased to be known as the Labour Hall, and became the Park

Street Co-operative Store.

The story of the first Branch has an interest all its own.

Many were the misgivings of all concerned as to the result of this

enterprise.

The first year in Full Street, despite the many disadvantages

of the place, developed unforeseen signs of growth. The first year in Park

Street proved the wisdom and intrepidity of the new venture. In the

December quarter of 1860, 290 members were enrolled, and £463. 14s. was

received in contributions for shares. In 1867 the total membership had

risen to 706, and the sales that quarter reached £2,560, an increase over

the previous quarter of £767, at which the hearts of the members greatly

rejoiced, for after paying 5 per cent on shares, and 2½ per cent for

depreciation of fixed stock, the dividend reached what in those days was

thought magnificent, 1s. 8d. in the £. The society had found the secret of

making money, and demonstrated to the town that co-operation meant profit. Previous to the opening of the Park Street Store, the receipts had been

about £63 a week. In June, 1862, the receipts had increased to £450 a

week.

This was not accomplished by sleight of hand, but by toil of hand and toil

of thought. The committee did not spare themselves. Desirous of

economising, they bethought themselves that instead of buying bacon, they might kill their own pigs.

Underneath the meeting room of the Labour Hall, which, as we have said,

was ascended by stairs, was a large room. One member fitted up a copper in

it to boil the water for scalding the pigs; but being an amateur, there

were defects in the construction of it, and it was difficult to get the

water

to boil. One evening the committee assembled at Park Street

to superintend the slaughter of a pig. The amateur butcher did not

understand his work, and was uncertain where the fatal stab should be

given. One of the committee, who thought he knew, pointed with his walking

stick to what he considered the right spot, but the pig resented the

entire proceeding, and suddenly veered round so swiftly, that the stick

pointed to the

opposite extremity of the turbulent animal. It was late before

the operations were all over, and all the committee left save two, who

remained to clear up the place a little, when they discovered all too

late, that the amateur operator had gone home taking the key of the store,

and neither knew where he lived. It was impossible to them to expose the

little property of the society unprotected, and the two committee-men sat

up all night with the pig.

Such an adventure was not likely to remain secret, and the next day the

amateur delinquents were saluted with squeals from the members, who had

learned what had happened, whereas they deserved praise rather than

ridicule for their fidelity, and for the trouble they had incurred by

their night watch for the preservation of the society's property. A

caricature of the scene, in the underground room of the Labour Hall, was

another feature of the untoward merriment. All the same there were comic

aspects in the adventure. The co-operators showed great skill in their

undertakings, but pig killing was not one of their attainments. However,

the pig killing question lasted for some time, and appeared in many

minutes. Two years later Mr. Wilford's resignation on the "Pig killing

committee" was recorded. A pig killing committee seems to have been

started. Another minute records "That Mrs. Newbold's terms are to be

ascertained, and whether she will let her pig sty." A further minute

says—"In future no refreshment whatever be allowed to any persons killing

pigs at the society's expense, and a new butcher or meat man is to be

obtained." It is clear the society suspected a leakage somewhere. Pigs

seem to have been a great trouble to the committee from the beginning.

At length it was resolved, "That the pay of the committee be 10s. a

quarter," not much certainly, less than 1s. a night, less than a mechanic

would expect for two hours over work. In the case of the committee, the

best faculties of the mind had to be employed for promotion of the

interests of the society. The nights often prolonged, deputations have to

be gone upon, and attendance in the chair or on the platform of public

meetings, often at a distance, have to be given by members of committee.

It is ever strange that working men, whose policy it is to have good

wages, are seldom forward to give good wages themselves, to those in their

service, which is setting a bad example to their employers; still, though

the resolution did not go far, it showed, on the part of members, a rising

sense of

business and self-respect, and that they no longer desired to have their

affairs managed by charity, which is always against success. The committee

became established at Park Street, and met again in a very small room. The

committee ceased any longer to meet in Full Street.

The vigilance of the committee not only brought the members profit, but

prevented loss. In 1861 the society issued paper checks representing the

amount of purchases. Counter

foils were kept in the shopman's book. A woman presented at

the Park Street Branch checks for £6. Mr. Scotton, one of the examining

committee (there were two others—Messrs. Wilford and Cresswell) found a

figure added to several, making the 1s.

check to represent 11s. The woman was arrested and when the case was

tried, the judge consulted with the counsel, and dismissed the accused. It

appeared there was no law recognising forged checks to claim dividends,

and the judge promised to communicate with the Attorney-General with a

view to got a short Act passed, making that kind of forgery penal.

An amusing incident occurred at the trial. While the judge was engaged

writing, the jury, consisting chiefly of farmers, were seriously

deliberating in the box. The judge observing them, said, "Gentlemen, what

is your difficulty, can I assist you?" The foreman replied they could not

agree whether the prisoner was guilty or not. The judge said, "Gentlemen,

the prisoner has been gone some time and is probably now, at home." They

had not noticed the dismissal

of the accused. The society considerately resolved to recommend the

prisoner to mercy, but a better termination came to her. Later the

committee adopted metal checks and no further case occurred of the kind.

A pleasant thing was done in 1863, on the occasion of the marriage of the

Prince of Wales, who has given valued proofs of his interest in the

co-operative improvement of the people. To celebrate the advent of the

Princess Alexandra, a holiday was given to all persons in the employ of

the society, and £5 were proposed by the committee that a festive dinner

should conclude the rejoicings of the day.

It is recorded "that the registered office be Park Street, according to

Act of Parliament." A committee (on which were Messrs. Scotton, Mather,

and Swift) was appointed to revise the rules, which were duly certified by

the Registrar. Revision and amendments have to be made by every

society as its business advances (as late as 1899 important amendments

were under consideration.) The society in 1863 came under the new rules. The whole of

the committee then vacated office. On voting, the following persons were

elected on the committee: W. Wilford, T. Barrodell, W. Slater, A. Scotton,

G. Wright, W. Ashindle, W. Corner, H. Barrett, T. Sherwin, T. Cresswell,

and W. Hemm, in the order here named. On July 24th, 1863, the

committee-men of each store were requested to have their names posted in

each store, for the purpose of members making complaints or asking

questions, which shows the equality cultivated in the society, and that

the suggestions made by members for improvement in any respect, would be

received with friendliness by the committee. On opening the Park Street

Branch, a manager was appointed. It is the first time a "manager" was

mentioned. They early resolved to stop giving credit, into which they had

fallen, it being contrary to co-operative profession, and opposed to

thrift, economy, and independence, for he who is in debt is owned by

somebody else.

In those days of enthusiasm, imagination was very active. The Park Street

Store being the first possession of the society, the little freehold was

thought to be capable of everything, and a question was brought before the

committee of erecting a bakehouse at Park Street. The bakehouse question

was destined often to come before the committee.

Eventually, alterations in Park Street were resolved upon, and were to be

completed in three weeks, under a penalty of £3 a day beyond that time. Mr.

Brown's contract was accepted, and a radical change of front was

contemplated. The "floor was to be made level with the street," Park

Street is the place meant though not named in the minutes. By lowering the

floor the old Hall gained in loftiness of appearance, and the old

dancing-room, the scene of festive and tragic events as we have related,

lost in height; but the shop is made level with the street, the steps are

abolished, and customers can enter as they would at other shops. The

floor-lowered room makes a commodious place of business, as may be seen to

this day.

This chapter is designed to include only the earlier days of the Park

Street Branch. The society flourished here and grew in favour with the

members, and acquired position in the town. Its march was onwards. Extension was always its watchword. In due course the committee had in

view to open

a second branch. The Dove Inn was advertised for sale by contract, the

reserve price £1,200, and the society bought it.

They were in no want of a public house. The Dove Inn was an innocent name,

but if doves drank much beer they would not be very innocent, and if

co-operators were given that way, they would not have much money to spend

at the store. There were, however, back premises attached to the Inn

property, out of which, or in which, a store could be made. There were not

many trees to be seen in Park Street, and there

were no nuns in Nun Street. It was a pretty one-syllable name, and in that

street the second branch was established.

The Nun Street Branch.

CHAPTER VII.

THE Nun Street Store was established in a building which again stood back

from the main street. The co-operators had no reason to regret coming to

the front in Park Street, but they were for the fourth time up a passage,

and the Nun Street Store, like all the previous ones (save Victoria

Street) was on a second storey, in the rear of

the Dove Inn. The ascent to the store was again up steps

from the outside. The entrance from the street was through

a narrow passage, which still remains. There were windows in the rooms

occupied by the store, but they looked into the

public house yard. The premises had been used previously

as a clubroom and dancing-room. The society converted the dancing-room

into a store, and the room beneath, which was windowless, into a

warehouse. The Nun Street Store was opened in June, 1862, and new business

soon rewarded the enterprise of the committee. Mr. Scotton—who was always

at the door or altar of a new temple when initiatory ceremonies had to be

performed—was, with Mr. Hilliard and Mr. Mather, appointed to pay the

first dividends at Nun Street. It was done in the warehouse underneath the

store.

In what a plain, humble way business had to be conducted there is seen in

circumstances under which dividends were paid. Never was a more weird or

humble

banking house. There was no gas in the warehouse, nor any

counter or desk. Two empty flour barrels were turned bottom up, and

candles put in ginger beer bottles, furnished the light whereby the

paymasters of the co-operative forces discharged their duties. But

before dividends could be paid they had to be earned. The method by

which they accrued will best be shown by continuing the narrative of the

proceedings of the directors.

The butcher, the baker, and the pig soon came into the minds

of the committee, if, indeed, they were ever out of their thoughts.

Mr. Brown was engaged to put up an oven, and the society began baking its

own bread. Baking takes precedence in the productive functions of

the store. An order was given for 300 sacks of flour. The

bakehouse was real, and was soon doing business. Next we read of a

"Baking Committee," who are instructed to examine the buns, and report.

It is notable in every department how conscientiously the

society endeavours to carry out the co-operative pledge of purity and

excellence in all things in which they deal.

In February, 1864, instructions are issued "for a Tea Party

of 500 persons." Urns are to be obtained from the Midland Railway,

who appear to be friendly to the store. Plainly there are

vegetarians on the committee, since ham sandwiches are prohibited, which

appear to have been formerly provided. The baker is to make a

specimen loaf, and say what he puts in it. The portions of currants

and raisins are enumerated, and by a special resolution he is to be

permitted to put "two eggs in each stone of bread." Truly the eggs

were not in excess. But the committee have their own ideas on that

point. Never were there such conscientious bakers. To this

day, as will be seen hereafter, the committee are honourably scrupulous as

to the quality of their provisions.

The butchers—or meat makers—largely occupy the attention of

the committee. At a later date (1871) it is ordered that they are

"to have not more than half a pound of steak allowed them on Fridays

instead of going home to dinner, and that it be left to the superintendent

to look to it." Mr. Bagnall, at a later date, is to come before the

committee, and the secretary is not to pay for the pig until after the

committee meeting. The committee are to meet at Nun Street, "to

consider an improved method of slaughtering pigs." Feelings of

humanity went with their ideas of porcine economy.

Even in matters of decoration they left nothing to

conventional fancy. The committee have special opinions thereupon.

In July, 1863, the committee, with the chairman, are desired to see to the

painting of Nun Street, which is the first mention of the Nun Street Store

in the minutes. On July 24th, it is resolved "That the windows at

Nun Street be painted white, the doors and shutters are to be of dark

grained oak in oil, the spouting and store door to be painted stone

colour." The effect of coming into the open in Park Street for

business has had its results. The committee begin to show taste and

public daintiness. Probably the committee included experts of the

brush among its members. Mr. Walker is "to have the painting of Nun

Street for £3, and no money is to be paid until the work gives

satisfaction." Another minute shows personal kindness. "Mr.

Allen is to be allowed leave of absence from Monday till Thursday morning,

9 o'clock, and that his wages be paid. Mr. Peel is to take his place

for that time." Probably some calamity had befallen his family.

In the earlier years at Nun Street the society, judging from

the minutes—from which we transcribe the following items—appeared to have

made the Post-office their bankers. On July 25th, 1865, "£150 to be

invested in the Post-office Savings Bank," on August 11th, another £50 is

paid in, on August 27th, £150 more. In 1866 another £100 was

similarly invested, and on March 13th, 1867, a further sum of £100.

As late as 1871 it was laid down as a general rule that "spare capital be

invested in the Post-office Savings Bank."

Full Street was the seat of the Executive until it was

superseded by Albert Street. In the meantime two other branches were

established, Bridge Gate, 1866, and Abbey Street, 1868. Up to that

time there were five places of business and the proceedings of the

committee applied to one, or other, or all of them, unless otherwise

specified, or indicated by dates. The incidents next enumerated are

given generally in the order of time.

Stock is to be taken (December, 1863) in each store and "each

stocktaker is to have 3s. for the day." Considering the labour,

exactness, and conscientiousness required for this duty, 3s. a day is

slender payment, unless it was an addition to wages. Dividends were

fixed for Saturday at each store. The annual report for 1864 is to

be read and an address be given, which is the first time an annual meeting

or address has been mentioned. The profits realised are to be put in

the balance sheet for 1865. A dividend is declared at 1s. 3d. in the

£. This resolution as to profits being published is judicious,

though late. Mr. Swift is to assist the secretary in getting up the

report. Mention is made of "Cottage House," in Nun Street, which is

to have a new side boiler. The society possesses house property in

1864. Several later minutes show that the society was an accessible

and liberal landlord, thoughtful for the conveniences of its tenants;

alterations are to be made at Nun Street which shows that the society is

always growing and always increasing its facilities of business. Two

hundred and fifty books are ordered for the drapery department, business

is growing there. Business is active in 1865. "Shopmen not

present at eight in the morning are to be fined 6d. One hour is

allowed for dinner." Two thousand co-operative tracts are ordered.

Public inquiry is being made about the stores which has to be satisfied.

As early as 1864 inquiries were made as to the feasibility of setting up a

branch in Cotton Lane. In 1865 the committee are to look for a

suitable place for a branch in the neighbourhood of the Osmaston Road.

Fixtures for the Bridge Gate shop were under consideration. The same

year a subcommittee was appointed to inspect the best localities for

opening branch stores. Opening new branches had become a habit.

Later, property in Abbey Street was to be inspected; also, the first place

available there or in Burton Road to be taken. The passion for

extension does not neutralise the sense of prudence. The goods at

Bridge Gate are to be insured for £150. Indeed prudence was with the

committees, as earlier stores, as we have seen, were insured. Next,

inquiries were to be made respecting land in Burleigh Street. In

1867 the trustees of the Working Men's Associations were requested to make

an offer of their property. These pleasant invitations, given from

time to time, denote open-eyed enterprise. In 1868 a musical and

literary entertainment was resolved upon, and the opening of the

reading-room, at an admission of twopence. A month later the

secretary was appointed to attend the sale of certain property, and to go

to

£550 in his biddings. In 1869 "Land is ordered to be bought in

Derwent Street and Burleigh Street, if to be had." This year the

Abbey Street Store and stock are to be insured in the Co-operative

Insurance Company for £400.

As a tea party is resolved upon earlier, Mr. Oates is to be

solicited to give an address. There is to be interim singing.

Ham sandwiches are to be restored. Ladies' tickets are 350 in

number; Children's tickets, 150. The Mayor is requested to take the

chair, but in case he refuses, Mr. T. Roe is to be asked. This shows

the society had now the consciousness of public importance. A

thousand members' books are ordered. New adherents are coming in.

"Mr. Greening is to be informed (July 1867) that two copies

of the 'Industrial Partnership Record' will be taken for the use of the

committee." A report of the proceedings of the last quarterly

meeting is to be sent to each newspaper in the town. By this time

the proceedings of the society have public interest. In 1869 the

dividend was 1s. 6d. in the £. In 1870 it had risen to 1s. 8d. in

the £.

As early as 1866 a horse and cart were bought. The

committee built a stable at the back of the Nun Street Store, and kept

there the first horse the society possessed. A frontage was now

wanted. As the Dove Inn stood at the corner of Nun Street and

William Street, as it does now, could the society have converted that into

a store, the position had been commanding? Later, Nov. 3rd, 1871,

they bought two small freehold cottages, which adjoined the passage

entrance to their store, for £260. On the site of those two cottages

they built the present Nun Street Store, which stands in the street line.

The new store cost £407 to build. This, with the purchase money of

the two cottages (which they pulled down) made the cost of the Nun Street

Store £667. Some additions raised it to £683.

Not having any desire to enter upon the publican business,

and the reconstruction of the Dove Inn being too expensive, the society

sold it to complete the purchase of the cottages.

Activity and advance of the cause came with Nun Street,

activity impossible until capital was acquired by the accumulation of

profits. Branch making continued to be a pursuit. Mr. Brown,

now of Acton, to whom reference has been made, is the one living member

who helped in the formation of the George Yard Society, and who remained

in Derby until after Nun Street Store was established, gives it as his

impression 'that the success of co-operation in those days was largely

owing to the energy, perseverance and tact of the secretary, Mr. George

Smith, and John Swift, and the good working committee, some of which

continue to this day.

George Yard, Victoria Street, Full Street, Park Street, and

Nun Street Stores are the five cardinal places in the early history of the

Derby Society. The events, romance, and character occurring there,

will always have interest. The fortunes of co-operation in Derby

were founded in those five places. For nine years Full Street Store

was the legislative chamber, whence the edicts of the committee issued for

the government of the other stores, until the Central buildings of Albert

Street arose.

Curiosities of Early Records

CHAPTER VIII

THE reader who does not give a few minutes to this

chapter will have no adequate idea of the time and labour of investigation

it has taken to put into readable order the story of the Derby Society.

The early records are a mine of curiosities and of omissions, if a mine of

omissions be conceivable. The first minute book was a thin,

coverless quarto, as it has come down to this time. Unruled,

unpaged, and incomplete. Half the pages were filled with the names

of members, their proposers and seconders, and the other half containing

all the official records for eleven years, and all the executive

proceedings of four Stores—George Yard, Victoria Street, Full Street, and

Park Street. As we have said, the minute books bore no name, or

designation. No mention was made of any place where the meetings

were held, and not often the year in which the committee met. It is

not said where they were at any time, nor where they were going to when

they thought of moving; nor is it recorded when they were doing business,

where they had moved to. The names were as mysterious as the

minutes. One member appears at various times as "Corne," "Cornes,"

"Corner." The last proved to be the right way of writing his name.

In 1856, six years after they had commenced, few transactions

are set forth, and no entries of significance. The items recorded

relate to orders for goods, and the minutes extend only to October 15th in

the year. There are no entries from October 15th, 1856, until March

19th, 1857. No other meeting is recorded until December 15th, when

an adjourned meeting is mentioned. The minutes for 1861 are signed

for the first time by the "Chairman," J. Reynolds. At that time the

payment for the services of the committee was but 5s. a quarter.

Their few Christmas boxes, hitherto received by them, were ordered to be

carried to the General Fund. The £1 each, or 4½d.

per week, for their year of late night attendances and other duties, which

often encroached on meal hours, and often occupied portions of other

nights, was not increased. Thus the door was kept open for

clandestine commissions, which have been the bane of so many societies.

It is not said or suggested by the members that this hardworking committee

sought or received, afterwards, any secret gifts, but if they had, there

would have been an excuse for it, in the face of the niggardliness of this

confiscation of the Christmas boxes, which were not harmful since they

were known. To the credit of the members, the confiscation was

rescinded. Afterwards, two members of the committee were requested

to resign for allowing, or offering to allow, credit. This was an

act of principle to forbid credit in a co-operative society, which has

honour because it inculcates thrift, teaches thrift, and seeks to deliver

its members from the degradation and slavery of debt.

The second minute book, again a thin quarto, has a cover, but

it commences without any date, or place being given. A subsequent minute

book states the year as being 1863.

After May 13th, 1862, no minutes are signed until November

24th, 1863, when W. Slater's name appears as chairman. After January

18th, 1864, no chairman's name appears until July 17th, 1865, when Samuel

Taylor signs the minutes. In the year 1865, the minutes are to be

confirmed, and that by resolution, and not by the signature of the

chairman.

The third minute book is a larger quarto, in boards, still

thin, bought apparently for its cheapness, as dilapidation seems to have

been hereditary in its binding. It gives minutes under date, October

10th, 1865 continued, but does not say where from. The last

committee meeting in the last book was dated August 25th. The last

entry in the minute book relates to a familiar question: "Resolved, that

it be left to the Pig Committee and the Secretary to determine how many

pigs shall be killed in the week." A preceding minute orders, "That

the Pig Buying Committee be allowed to make arrangements with Mrs. Newbold

for stable and pig sty." The lady's "sty" is the subject of another

minute. The ubiquitous animals are to be well taken care of, and a

sausage machine is to be bought for the meat men to make sausages.

What has been said in an earlier chapter of the just landlordism of the

society, is borne out by a minute of 1873, when the chairman and Mr.

Scotton were appointed to examine the cottage houses in Harriet Street,

and "see what wants doing." The society had regard for the needs and

comfort of tenants. They were not like Mrs. Poyser's landlord, who

looked only after the rents, and had no thought for the comforts of the

occupants.

In this third minute book, for the first time the records are

called those of the "Derby Co-operative Provident Society."

In 1861 minutes are signed by James Topham, in 1862 by John

Wheatly, in 1866 by John Riley, in 1867 by W. Wilford as chairman.

Of Taylor, Wheatly, and Wilford before named, the two first of the three

were in office but a short time, and did not long take interest in the

society's proceedings. Mr. James Mather became president April 17th,

1872. His name appears with great regularity down to July, 1873,

afterwards Mr. A. Scotton's name similarly appears as president. Mr.

Mather's long and conspicuous services are held in high estimation among

the members. No succession of presidents is traceable, only a series

of chance chairmen. This however is always the case with infantine

societies, as it is with their newspaper organs when they have them.

Their business is conducted, and their organs are written by charity, but

when the business attains to an assured income, or their news organs

command a satisfactory circulation, it is discovered that charity has no

dependence in it, and means inefficiency and loss. It pays best to

pay well all whose services are indispensable.

True, it often happens that precious services, more than

money can buy, are given for nothing by men of zeal and principle, but

such devotion cannot be demanded, and ought not to be rendered free, when

there are means of paying for them, as it would deaden the sense of

independence and self-respect in the recipients. Help which is

strength to the weak, is enervating to the strong.

Nevertheless, co-operators learned to act like gentlemen

sooner than was to be expected. When the stores attained the status

of a commercial firm, they contributed to public charity and to the relief

of public distress, like employers, and often did more than private

employers. All over the minutes are scattered records of gifts.

The Derby Society in 1869 sent a subscription to London in aid of a public

conference, which ended in holding the first Congress and in establishing

the Central Board, which the writer was appointed to propose in a special

paper. Nor was the charity of the Derby Society outside only, it

began at home. Two guineas and then three guineas a year was given

to the Infirmary, and as the society increased in means, the annual

contribution was increased to five guineas. From fraternal feeling,

which early prevailed, they made gifts in aid to societies in need of

help. This indeed was a characteristic of earlier societies in days

when co-operative societies were in their infancy. So far back as

1834 there was an old co-operative society at Foleshill, near Coventry,

familiar to Dr. John Watts and John Collier Farn, both co-operative

advocates born in Coventry. Recently, Mr. College, secretary of the

Lockhart Lane Society, at Foleshill, sent Mr. Scotton information that he

had found in an old minute book the following entry, "January 30th,

1834:—At a meeting called expressly for the purpose, James Harris in the

chair, it was moved by Thomas Wikins, and seconded by Richard Farefield,

and carried unanimously, 'That this society do give to the Derby weavers

the sum of £1, the better to enable them to withstand the tyrannous

impositions sought to be practised upon them by their employer.'—James

Harris, Chairman."

At this time the worth of this Co-operative Society was

entered at £35. 15s. 4d. It was out of that they made their generous

gift.

In 1834 Derby was the seat of the silk trade, and had many

large mills which have long since declined. The timely gift to Derby

workmen, then on strike, was made 16 years before the Derby Co-operative

Society began, that ought to have led to the formation of a co-operative

society in Derby. The Foleshill gift was made ten years before the

Rochdale Society began to popularise participation in profit among

members, which first made co-operation attractive to workmen.

One curious minute more may be sufficient to justify the

title of this chapter. The minute is as follows:—"Sept. 25th, 1867,

'That the Secretary shall not grant leave of absence to any servants,

except in cases of sickness or death, and that any servant requiring leave

of absence, between the committee nights, shall apply to the committee

over that store."' That the "sick" should give personal notice of

their condition is conceivable, but how the "dead" are to do it is not so

clear. They do not usually ask for "leave of absence," they take it,

regardless of official resolutions, or the duty of applying for permission

to die. The dead servants of the Derby Society in 1867 must have had

their wits about them, if they complied with this resolution, which

probably meant that in case of the sickness of any servant, or of death in

his family, leave of absence would be granted on due notice thereof, but

this is not said.

The fourth book of minutes is a substantially bound volume.

It opens with the proceedings of the committee of June 10th, 1861, and the

entries have a business air about them, yet it makes no mention of the

place where the committee met.

The fifth minute book is a handsome and larger volume with

the words "Minute Book" on the back, and on the side "The Derby

Co-operative Provident Society Limited" in gold letters. It

commences with the proceedings of the committee of June 19th, 1872, but

still without disclosing where the committee sat. Conspirators could

not be more reticent about their address. The records are now

businesslike, uninterrupted, and clear.

Though the minutes were irregular and often deficient during

the first 20 years, as is common with societies of working men in the

early years of a self-helping movement—they show the proceedings to be

entirely representative, as everything is done by resolutions of

committees, of which all the members are cognisant—as is the rule in

co-operative societies. It may be said of these brave if humble

actors—in the words of the Rev. Dr. Joseph Parker in his alluring story of

"A Preacher's Life," when describing Tyneside men of a similar class—"They

were honest men and useful citizens, and we must in common justice

remember that their environment was not favourable to the large mindedness

and intellectual emulation associated with life in large and prosperous

towns." Derby was not "large and prosperous" as it now is, when the

do-operative Society first began to improve the condition of working

people.

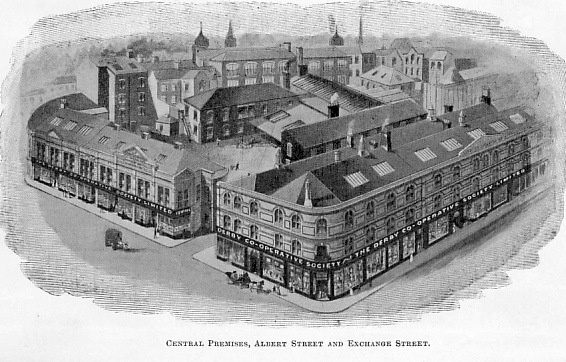

The Central Stores.

CHAPTER IX.

THE Central Stores, situated in Albert Street, and continued without break

into Exchange Street, is the most imposing commercial sight in Derby. Whether considered with regard to their origin, their extent, their

appearance, or position, they are alike notable. Were it possible for a

spectator to take a bird's eye view of the 37 branches, radiating from

this centre, he would admit that the sight is as the Scotch would say—"just wonderful."

The second of the three jubilee societies, that of Leeds, has its Central

Stores in Albion Street, and the Derby Society has its multitudinous

Central Buildings in Albert Street. Both streets begin with the first

letter of the alphabet. Leeds has, and Derby bids fair to have, branches

enough to exhaust all the remaining letters.

In Nun Street, the ambition of expansion "grew," as all good things ought,

"by what it feeds upon." As early as 1865, the committee were instructed

"to inquire the rent of suitable premises for a Central Store "The

possibility of being able to buy freehold land and build premises for

themselves did not then appear.

In 1868 it was found that a little property was to be bought in Albert

Street, on which a Central Office could be erected. In January, 1869, the

purchase was resolved upon, but not without ominous doubts being awakened.

The reader has seen what consternation was created when it was proposed to

emerge from the dreary alley in Sadler

Gate to Victoria Street. But that was surpassed by the alarm which took

possession of apprehensive members when the step

was taken to buy land and build upon it. The ruin of the society was

pronounced not only to be certain, but absolute. The romance of

co-operation has nowhere been more conspicuous than in Derby. Nobody could

prove that the projected purchase would not ruin the society. But in

co-operation, as in war, risks have to be run, and self-help

requires good judgment, and a cool calculation of chances. Is it not

Bishop Butler who says, "Probability is the guide of man," and it

requires no mean ability to estimate probability. Honest, prudent

self-help makes character. Responsibility is

a noble education. It requires thoughtful courage to face the consequences

of an important decision. Those who incur

responsibilities must meet them. They who would save others from the

results of their own actions would fill the world with fools. The members

were wary, and weighed things well. A meeting was held, and it was only

after anxious discussion that a resolution was passed authorising the

committee to buy. When this was declared carried, the oldest and most

loyal member of the society rose and declared, with some emotion, that "they had driven the first nail in the coffin of the society." But the

coffin never came up for nailing, and instead, the nail was driven into

the nascent chariot of the Central Stores. The mistaken prophet is still

one of the best members of the society, and no one rejoices more than he

that his honourable misgiving for the welfare of the society was

unfounded.

No Cassandra, nor any prophecy of disaster, deterred the society. Mr.

Moody was instructed to prepare the necessary deeds of purchase, and the

seal of the society was ordered to

be attached to the agreement. The dimensions of the property were defined,

"sixty-four feet frontage, and fifty-two feet in depth" were to be

bought, and the secretary was to pay the

deposit. Thompson and Young were to be the architects for erecting the

Central Store, which was to be three stories high.

The front of the new stores was to be of red brick, picked out with white

stone facings. Mr. Bridgart's estimate of £2,398 for the erection of the

store in Albert Street was accepted.

The contract for the Central Store was thrown open for public competition,

but the committee did not bind themselves

to accept the lowest tender, which was a wise co-operative condition. If

purchasers in a store all bound themselves to take the lowest priced

articles, taste and art and excellence would die. The worst things would

be chosen, and the store reduced to a cheap selling shop. One lesson that

needs perpetual inculcation is that members should be induced on all

occasions to measure cheapness by excellence, and not excellence by

cheapness. Of course excellent things may be cheap, but what the purchaser

has to do, is to be sure that they are excellent.

Mr. Thompson's estimate of £199 was increased by extras amounting to £273. As happens to other building enterprises, it is subsequently found that

something further is wanted—not thought of at first, and additional cost

is incurred. The committee showed fairness and good sense in conceding

the increase of charge for the inevitable extras.

By this time the branches were extending and required constant inspection,

which implied a long and fatiguing walk to visit them. Besides, the

erection of the Central Store necessitated daily oversight, so that it

became economical to provide a vehicle (which was dignified by the name of

a chariot) to enable the committee and other officers to superintend the

operations in Albert Street, and personally to promote the business of

outlying branches. Of course it was a new sensation for working men of

Derby to ride about in a chariot of their own. This was not ostentation

but necessity. The honour was that the zeal of the committee and the

earnestness of the members had rendered convenience of travel

indispensable.

Extension was still in the mind of the committee. In September, 1873, a

special general meeting was called to consider the purchase of land

adjoining Albert Street Store, belonging to Lord Belper. Had Lord Belper

shown the same objection to co-operators at Derby, as a former Lord Derby

did to Unitarians at Bury, there would have been no extension of the

Albert Street Stores.

In the days of the old Lord Derby, who often appeared in the Preston

Cockpit, and who was better versed in cock-fighting than theology, but was

unfortunately the owner of all the land in Bury suitable for the site of

an Unitarian Chapel, not a square yard would he grant for the worship of

one God. Had the application been to purchase land for the excavation of a

cockpit, it would have been conceded. His Grace had no scruples on that

head. The end of it was, the Unitarians had to wait until they could

convert a small landowner, possessing a site adapted for their purpose,

and not until then could an Unitarian Church be erected in Bury.

Fortunately, Lord Belper was a man with a different disposition. Robert

Owen, who had both visited and lectured in Derby, was very intimate with

Joseph Strutt. Perhaps some influence lay there. Doubtless had Lord Belper

listened to the opinions, or representations of shop-keepers, he might

have declined to sell his land to co-operators. But he thought working men

were as fully entitled as tradesmen to the rights of the market, and that

conducting their business on the principle of co-operation, instead of

competition, did not cancel their right of trading. It was to Lord Belper's sense of justice that the co-operators owed the possession of the

most important mercantile site then available in Derby.

The first building contained a draper's shop, a shoe shop, a grocery, a

meat shop, and a restaurant. The entrance to the dining and tea room is

now through an inviting confectionery shop. The restaurant is open to the

public, as well as to members. The tariff is low, the supply ample and of

good quality—always possible to a co-operative society, pledged to

excellence and wholesomeness. Such a house of call for refreshments, open

to anyone, is a great convenience to purchasers at the store, to market

people, and visitors to the town. Over this building was put the gilt

legend of the society—clasped hands, the emblem of brotherhood. There

must be amity in the hearts of men, before they clasp hands. The act is a

pledge of goodwill. It means that personal strife

has ceased, and unity of interest has commenced. Industry and fraternity

all sharing in the advantages—this is the device of co-operation; never

yet seen over a private shop. The private shop represents public

convenience, good as far as it goes, co-operation goes further and

represents the public good.

The seat of legislation which had severally been located in five places

(last in Full Street) was now finally established in Albert Street, and

henceforth the growth and fortunes of the society are to be found in its

initiative

But legislation never ceased. Decrees of committee are necessarily

perpetual, or government of the society could not go on. In reference to

an inquiry for terms, it was agreed to

let Committee and Tea Rooms to the School Board at £40 per annum; the

large room, when required, £20; gas and coal for £15; cleaning, £15 per

annum.

Meanwhile the extension of Albert Street Stores has been going on. No. 1

in the series was opened in 1871, No. 2 followed; the cost of the two

buildings, including the land, was £13,282. This great block was in part

occupied in 1876. It will assist the reader to fully understand the extent

of the buildings known as the Central Stores, in Albert Street and

Exchange Street, if we anticipate dates a little. No. 4 premises in

Exchange Street were opened in 1890, at the cost of £9,990. A fifth block

of premises called No. 5, is situated in East Street, and is used for

ironmongery goods. The back of these premises comes into the great

business yard belonging to the Albert Street Stores. These premises were

opened in March, 1897; their cost was £2,979, so that the whole of the

Central premises cost £27,392. Thus, these Central premises came to

contain warehouses, a large hall, lecture-room, ante-room, committee-rooms

and offices, workrooms for shoemakers, tailors, milliners, dressmakers,

and for the sale of drapery, millinery, furniture, grocery, provisions,

meat, boots, and clothing. A Crossley's 5-horse power silent gas engine

was erected in place of an old vertical noisy engine. These Central

Stores, as the reader will see in the engraving of them, have a splendid

and continuous frontage, comprising more than twenty fine shop windows, a

portion of which stand in Albert Street, and the others extend into

Exchange Street, formerly called Princes Street. East Street, where the

ironmongery establishment stands, formerly bore the ignominious name of "Bag Lane," but when the thoroughfare became dignified by well-to-do

buildings, the Corporation, desirous of extending in the town a knowledge

of the points of the compass, dismissed Bag Lane "bag and baggage," to

use Mr. Gladstone's famous Blackheath phrase, and substituted East Street.

The "yard," which has been incidentally so designated, is in reality a

serious and not a frivolous interior. It is the dwelling-place of vehicles

of all kinds and stores of all descriptions. In its various buildings,

the commissariat departments

of all the branches were established. The yard was full of business life

every hour of the day, and often well into the night.

The Derby co-operators were not only economists in

business—they were economists in celebrations, and no ceremony is

recorded when successive blocks were opened. The habit was to have a large

party at the Drill Hall every Shrove Tuesday, and one of these meetings

was made to serve for a public celebration, when one became due. But in

1876 the Shrove Tuesday Annual Tea Party took place in their new

Co-operative Hall, which was crowded above and below, by one company

succeeding another. Even the juvenile members of co-operative families had

their entertainment. In the evening speeches were made, and the president,

Mr. Hilliard, took the chair. Alluding to the practice of town grocers

giving a present of a few candles to their customers at Christmas as a

reward for their custom during the year, he said "The Co-operative

Society had given their members no candles, but had given them £7,196,

which would furnish them with burning and shining lights all the year

round." He said, what every society does not understand yet, namely, that

"The women must lead in this movement, for co-operation is essentially

a woman's question. The dividends paid during the year had clothed many a

child and brightened many a

home. It was the duty of every member to increase his or her income. England itself was of the nature of one great society, and it behoved

everyone to increase its wealth, and the man who does nothing does not

enrich the country, but takes from him who does. If everybody did their

fair share of work, he

and they would have to do a great deal less." All this was brightly and

admirably said.

The annual report announced "the establishment of a Building Department in

connection with the society. Already 14 houses had been erected, and four

previously built had been allotted to members; and about six acres of land

had been bought which would hold about 200 more. The land had been drained

and streets marked out. The branch of the Meat-making

Department had been opened on the Normanton Road. The new buildings in

Albert Street, in Princes Street (since named Exchange Street), were near

completion, which, when finished, would be the best block of buildings for

business purposes in

the town." It was stated, that by means of the Education Fund, they had

started the Derby Co-operative Record for the better information of the

members and the public. There was then in active operation, twelve

branches in the Grocery Department, three in the Butchery (in this

narrative

always spoken of as the Meat Department), three in Bakery, and one each in

Drapery, Boots, Tailoring, and also two Coal Depôts.

In the new building, the society possessed a large Lecture Hall of good

dimensions, which contains a portable gymnasium for the use of members,

when lectures, or concerts, or tea parties are not on. "A country," says

Mr. Goldwin Smith, "without towns or cities, or stately edifices, little

impresses the traveller, and never commands his admiration." This is true

of co-operation—without stores of some mark and dignity, neither its

importance, vitality, nor prosperity, is made manifest. Co-operation in

Derby fulfils these conditions.

From various causes the dividend was low in 1872, being only 1s. 6d. in

the £, made up from the Reserve Fund, it being understood that the amount

taken from the fund be replaced when the profits exceed 1s. 6d. In 1873

the dividend declared was 1s. 10d. in the £. By this time the amount

borrowed from the Reserve Fund, in July, 1872, will have been repaid. As

late as 1875, a dividend of 2s. was realised. The names of persons

admitted as members are still recorded in the minute book, as instance

Mary Grocott, Mary Hill, Messrs. Harrigen, Toft, Topley, Hines, Hindley.

The Monthly Record for information of members, was established in this

year. The public annals of the society commence in 1876. The Editor calls

attention to the Penny Bank. The Albert Street extension is beginning to

present a noble front. The fourteen houses and stores at California are

progressing satisfactorily.

Elsewhere branch operations are going on. Mr. Blood's tender for the

erection of property in Parliament Street and Stockbrook Street is to be

accepted. The committee justly consider, owing to time having been wasted

from causes known—the period of the contract be extended, and the fine

for non-fulfilment reduced from £10 to £5 per week. This year (1876) the

Building Department began. County votes were claimed and conceded.

|

|

|

R. HILLIARD,

J.P., Manager. |

The committee have been struck by a remark made at the Leicester Congress

by Mr. John Ellis, chairman of the Midland Railway, which Mr. Hilliard

commended, in one of his many speeches to branch meetings. Mr. Ellis,

speaking in a Chapel where the meeting was held, said: "It was not often

they saw a member of the Society of Friends in anything like a pulpit,"

then he made wise remarks which attracted attention in Derby. He said "success with co-operators as in every other kind of business, depended on

the management and in an eminent degree on confidence. His own interest in

their work arose from the fact that he regarded it as a movement in favour

of self-reliance, thrift, and a desire to make the best use of the means

which they, as hard workers, received as the result of their labours." Thrift, which Mr. Ellis justly commended, had

been a characteristic of Derby co-operators. Profit-making does not go far

unless Profit-saving accompanies it. This was the case in Derby for at

this time, 1876, the society had in deposit, with the Wholesale Society,

£5,000.

In the September quarter of 1877 the cash taken for goods sold was

£23,800—substantial business was being done now. Well might Mr. Hilliard

announce in the December following "that the society had been one

continued increase quarter by quarter."

A pleasant account is given in the Record, in 1878, of social life at the

Albert Street Tea and Coffee Room, opened on Saturday evenings. Mothers

and children were there, enjoying the warm refreshments; the husband was

at hand, reading the newspaper, others playing at chess and draughts. This

year a Penny Bank meeting was held, when 150 children sat down to a tea. The president of the society, Mr Hilliard, gave demonstrations in

phrenology, supplemented by a wise and genial address, and told a charming

story to the children.

In 1878 the dividend paid to members for the year amounted to £8,948. The

dividend to non-members was £220. What a miracle non-members are! Every

such person can become a member simply by consenting that the full

dividend he will then receive upon his purchases shall be applied to the

payment of a £1 share, which he will own, and receive 4 per cent interest

upon it, and ever after he will be entitled to the full dividend. Thus,

the non-members who now receive £220 would receive about £440. The wonder

is that persons so needy and greedy as poverty makes them will persist in

refusing £220 a year, which they might have. Such is the costly

eccentricity of ignorance.

For years before this, since 1872, the Co-operative News was sold at each

store and the profits divided among them to extend information among

non-members. In some societies the education committee sell the paper at a

halfpenny for this purpose.

But despite the stupidity of poverty, which in some quarters

prevailed—the good fortune of the society advanced. The editor of the

Record described 1877 as the most eventful and prosperous year in the

annals of the society. Their extensive premises in Albert Street and

Princes Street were opened, and new stores in Parliament Street and at Alvaston. That year the building department was active. That year all the

departments, millinery, dress, and mantles, were flourishing. The sales

for the year had been £98,000.

At the annual tea party in 1882 it was announced that the sales for the

past year exceeded £101,000. The profit realised exceeded £6,600. In that

year Mr. Hilliard was still president, and Mr. Swift, secretary.

The society, in 1884, about to erect 40 cottages in Cotton Lane, held a

tea party in St. Dunstan's Schoolroom, lent by the courtesy of the Rev. C.

H. Molineux. Mr. Scotton being called upon to speak on "Co-operation and

Thrift," he argued that difficult as was saving to working people, it was

possible

to them. The profits realised by co-operative societies were proof of it. About that time Lady Manners had told the world that "many ladies spent

£600 a year on their toilets alone, and £1,000 on dress, and £2,000 on

flowers for a single ball." Though the upper classes, as they were called,

set the people no example of frugality, the people must be an example to

themselves. That was the policy of self-helping co-operation.

Such was the extraordinary growth and opulence of the society, that the

leaders of the movement resolved to hold its sixteenth Congress there. The

paramount success of the society justified this, and Mr. Scotton's summary

of the position at that time well shows it.

The capital of the society now stood at £70,566. During the ten years

between 1874 and 1884 the society had paid to

its members dividends to the amount of £80,000. At this time, which

was the Congress year, the year's receipts for sales were as follows:—

|

|

£ |

s. |

d. |

|

Grocery and Provisions |

64,174 |

0 |

1 |

| Meat |

17,099 |

13 |

1 |

|

Drapery |

5,104 |

8 |

1 |

|

Millinery |

1,218 |

2 |

10½ |

|

Tailoring |

2,653 |

13 |

0 |

|

Boots and Shoes |

4,038 |

9 |

5 |

|

Furniture |

1,388 |

14 |

6 |

|

Jewellery |

48 |

7 |

1 |

|

Coals, in Loads |

3988 |

0 |

8 |

|

Coals, in Bags |

3,716 |

16 |

10 |

|

TOTAL |

103,440 |

5 |

7½ |

Profits realised during 1884 from all sources were £15,400. Subscriptions

to charitable and other objects £78, to Education Account £104. Seeing

that business folly nor ignorance could have made £15,000 of profit, £104

for education was certainly a limited concession. It was not understood

then, that intelligence is an investment which pays the highest dividend.

But this year was memorable for the first recognition of the principle of

participation in profits with employees. A recognition much in advance at

this time (1900) of many societies of pretension and importance. At the

quarterly meeting, Mr. Hilliard, the chairman, drew attention to the

Seaton Delaval Society, whose trade with the store amounted to an average

of £11. 11s. per member; but in Derby the average was a little over £5.

15s. per member. Mr. White pointed out that the Seaton Delaval Society

traded much more with the Wholesale Society than the Derby Society did,

which accounted for Seaton Delaval paying a dividend of 2s. 10d., while

the Derby Society paid only 2s. There were other reasons in the case.

Trading with the Wholesale was always a question of interest with the

Derby members. Fourteen years earlier the society resolved that the number

of shares in the North of England Co-operative Wholesale Society (which

the society had joined in 1867) be increased in consequence of the

increase in the number of members. The same year delegates were sent to

the Wholesale Society meeting for the revision of their rules. This was

the first time such delegation

had been made. In 1889 the purchases from the Wholesale for one quarter

were £8,852.

Still the society went forward as though the committee of management wore

seven-leagued boots. Next year Mr. Hilliard, at the quarterly meeting,

stated there had been an increase of members from 1,400 to 1,700 in the

Children's Saving Bank. Again, in 1887, the chairman announced that the

sales for the quarter had been more than £28,000, an increase of more than

£500 in the corresponding quarter of last year.

Among almanacs issued by the society, that of 1888 was deemed the best, as

indicating the success it recorded. It bore the title of "Victory." The

society certainly had grounds

for triumph. The success of co-operation had not only made its mark, it

had written its name in full in Derby, in a legible hand and the cause was

making itself felt throughout the county. Handel Cosham, M.P. for Bristol,

suggested that "We might do away with half the public houses and use the

other half as co-operative stores." The society had now grown

more intelligent in 1888 than it was in 1863. At the invitation of the

committee 150 employees sat down to tea in the large

hall in Albert Street. In 1863 when the committee voted £5 that the

employees and committee were to dine together on March 10th, on the

occasion of the Prince of Wales' marriage with the Danish Princess "from

over the sea"—the shops were to be closed and the shopmen to receive

their wages.

This was a graceful idea, honourable to the committee. But some unlovely

member (such as existed in those days among the working class) who could

not bear the idea that those who served them in the store should have any

enjoyment, went among others who had, or were induced to take a like view,

and got the vote of the committee disallowed, or reduced, at a

meeting of members. That class who do not know how to be generous

employers, were happily extinct in 1888, and the committee were able to

invite 150 of those who mainly make the fortunes of the store, to dine

with them. Under good management and good service, all departments of the

store flourished. In 1890 the amount taken in the Drapery department alone

for one week, at the end of November, was £403. 10s.

It is not possible to record in a portable book all the events and

incidents of half a century. But a consecutive and brilliant table of

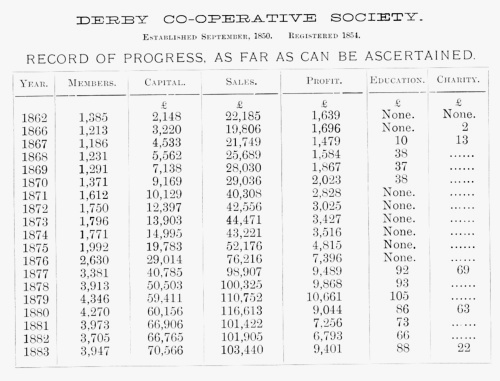

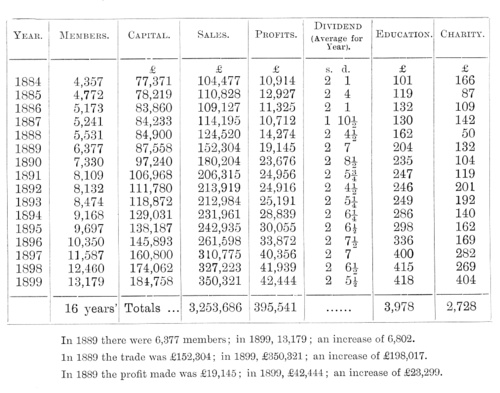

progress can be given for a long historical period. Mr. Scotton, with no

mean labour, has hunted up all the old, scattered, and forgotten balance

sheets, and with Mr. Rest has succeeded in producing a table of the

financial progress of the society for nearly 40 years. Some documents

appear to have survived from which the position of the society can be

indicated in 1862; but there are no means of giving

accurate statements for the years 1863, 1864, and 1865. It is common in

the earlier co-operative societies for the directors not to foresee the

progress possible to them, nor to think that

their humble balance sheets in the beginning may be of interest in the

future. Mr. Scotton's table shows the steady advance of the society for 34

years, under the instructive heads of members, capital, sales, profit,

education, and charity.

The reader has now before him a bird's-eye view of the progress of the

Derby Co-operative Society. It is known that night birds have eyes twice

as large as day birds; but a day bird can see the significance of these

eloquent and informing figures.

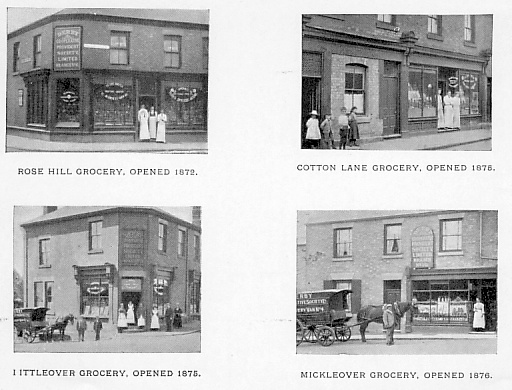

The Origin and Growth of the Branches.

CHAPTER X.

IT was Petrarch (if I remember rightly) who

apologised for writing a long letter, for the reason that he had not time

to write a short one. I have taken time to give the reader so far, a

short history of the chief events of fifty years' experience in the rise

and growth of a great store. It is easier to be prolix than to be

brief, yet brevity is a merit in this day of multitudinous activities,

providing the brevity is free from obscurity. It is of no use to put

a subject into a nutshell, unless a writer is sure that his readers are a

species of intellectual squirrels, who have time and teeth to crack the

nut. My object has rather been to hang the fruit of facts on

branches which bend low down, so that the busy man can pluck it without

trouble or delay. If even dainty fruit is hung too high, it will

never be gathered, save by readers of forethought and enterprise, who

carry ladders with them.

Fortune lies in wait for some persons, and befriends them on

the high road. Before others the goddess retreats to a "two-pair

back," where few find her. But the Derby co-operators found her

secreted in stables and lofts, in out-of-the-way yards, and they had to go

up narrow, steep, clumsy stairs, to find her. But since the Albert

Street Stores were built, the capricious goddess has shown more taste,

affableness, and courtesy, and is found now in front shops, and does not

disdain to visit the branches, distributing her bounty there.

There is no doubt a science of Co-operative Agriculture which

deals with the provision of select soil, and unadulterated seed, suitable

for the germination of branches. There is an art of branch sowing,

with well defined methods for the preparation of the soil favourable for

the seed to take root in, and a knowledge of certain chemicals, of the

nature of judicious speeches, calculated to nourish the seeds, and promote

their growth. We have an Agricultural and Horticultural Association

at Deptford, which deals with these things according to nature, which,

however, have their similitudes in propagandism. The Derby Society

have proved no mean masters of the art of co-operative agriculture.

It is a difficult art, because of its newness, to learn and apply, but by

perseverance, it can be acquired, and by skill and judgment great results

can be obtained. If at the exhibitions at the Crystal Palace

Festivals, there could be an Exhibition of Branches, Derby would take many

prizes.

Nobody surmised that the soil of Derby was naturally

favourable for this growth. But the Central Society sent out capable

explorers and prospectors, who discovered Klondike deposits and South

African gold fields of the co-operative kind, in Derby and its outlying

suburbs, which no one suspected.

At first, branch sowing yielded but a thin crop, which

scarcely showed its head above ground. But good tilling told, and at

length local stores were like Topsy, who accounted for her existence by

saying she knew nothing about being born, she "'spected she growed."

Stores seemed to spring out of the ground, after Full Street, where the

seeds of expansion were first sown. When the Carpenter Store first

took in the public, the natural fecundity of the Derby soil was revealed

and stores sprang up in many streets. No doubt when the plant was at

last observed above the earth, it was tended and watered from time to

time, until it attained self-sustaining development. The growth of

Stores and Departments will strike the reader as manifesting wonderful

spontaneity. Cooperative fertility became the marvel of the day.

Dead leaders who stood up for principle while living, have potency after

death, and it may be said of them, as was said of less useful saints, that

their bones worked miracles at their tomb. The example they had set,

the inspiration they had diffused, the co-operative seed they had sown,

were found to have a self-raising capacity. It was finely said at a

later period "Co-operation knows no frontier—it is meant for mankind."

Experience shows it can be acclimatized in any city or town, in any

district or in any land—where the people have discernment, zeal, and

patience. The Derby pioneers, when they went into what Lord Hampton

called "the open," planted orchards and ploughed fields, and, happier than

the poor husbandmen in competitive regions, they gather the fruit they

have grown, and reap the harvests they have sown. From minutes and

the Monthly Record of the society, pages may be filled with many

instances illustrative thereof.

As early as 1864 inquiries were made as to the feasibility of

setting up a branch in Cotton Lane. In 1865 new Stores were still in

the minds of the committee of management, who seemed like the typical man

of business, to sleep with one eye open in order to see how the main

chance is moving—the "main chance" with the committee was the chance of

establishing new branches.

In 1871 the committee were empowered to purchase the piece of

land at the corner of new street called Harriet Street. In June of

the same year "cottages are to be built on the spare land in Harriet

Street." In July, plans are ordered to be prepared for Rose Hill

Branch. A year later the rent of the houses in Harriet Street is

fixed at 3s. 6d. a week; and the Nun Street property is to be insured for

£300, and the Rose Hill and Bridge Gate property are to be insured—Rose

Hill property, building stock, and fixtures, for £1,150.

In 1865 "Cotton Lane was to be opened by a Tea and Public

Meeting if rooms can be had." In 1866, a Store was opened at Bridge

Gate. 1868, a Branch Store was to be opened in Abbey Street.

In 1873 it was found necessary to make a thoroughfare through Thorntree

Lane, and the committee are to consider how it can best be done. In

1875 "The shop at Allestree is to be taken. The Rev. Mr. Frith to be

written to." In the same year "Land is to be bought in Parliament

Street, belonging to Mr. Copstick, and a deposit is to be paid by the

Estate Committee." In 1876 Mickleover Branch (the first branch

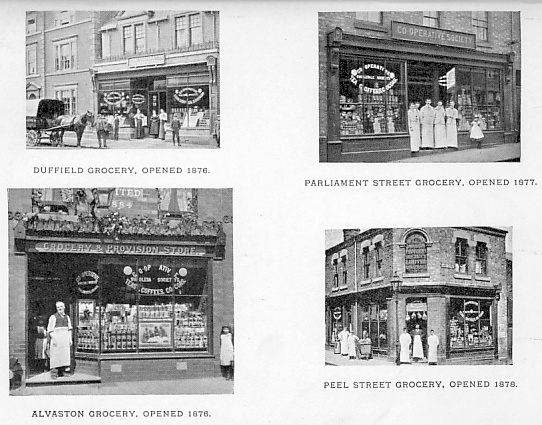

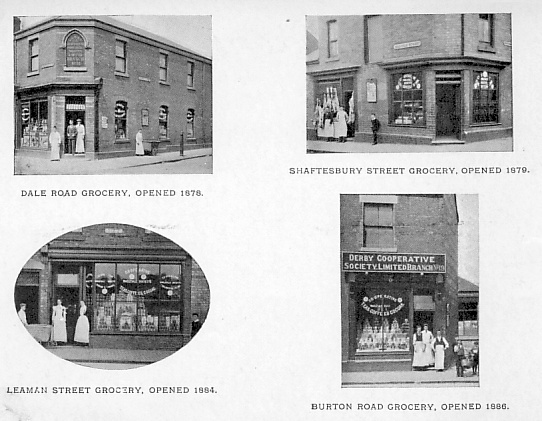

mentioned in the Monthly Record) was opened. Mr.

Hilliard was chairman of the meeting. The villages were calling for

branches. A meeting was held in the open air at Duffield, addressed

by Scotton, Swift, Garrett, and Eyre. Three members of the committee

were appointed to inquire into the desirability of opening branches in the

localities with which they were familiar—Littleover, Allestree, and

Cotton Lane. In 1876 instructions were given to Messrs. Eyre and

Garrett to take steps to open a branch store at Duffield.

Alvaston Branch was opened and celebrated by a large meeting.

In 1886, Alvaston has done a trade of nearly £8,000, and has received in

dividends £720. Duffield has received dividends of £728.

Littleover has received £756. In that year Cotton Lane, which had

been precariously mentioned in 1865, had attained to substantial notice.

The chairman stated "they were building 33 houses on their Cotton Lane

Land." In 1890 we read that "the New Shop built on the site of the

old one in Duffield was opened." Again, in 1891, we are told that

"the rebuilding of the Duffield Branch resulted in a great increase of

trade."

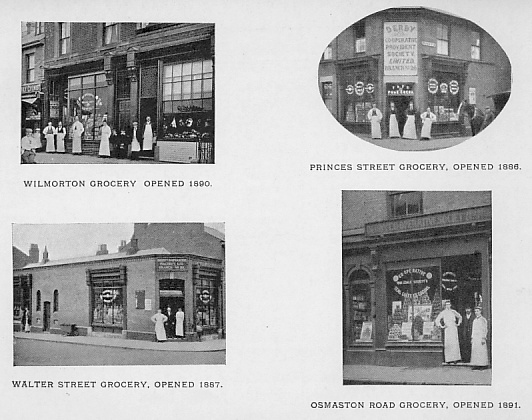

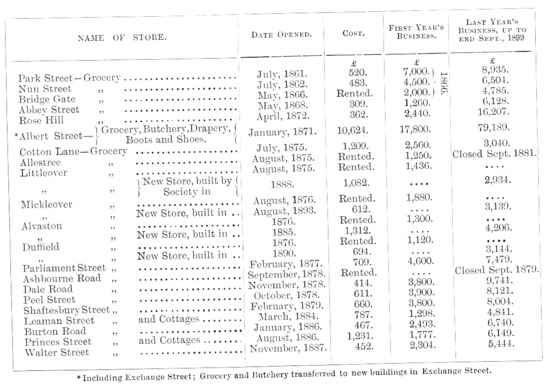

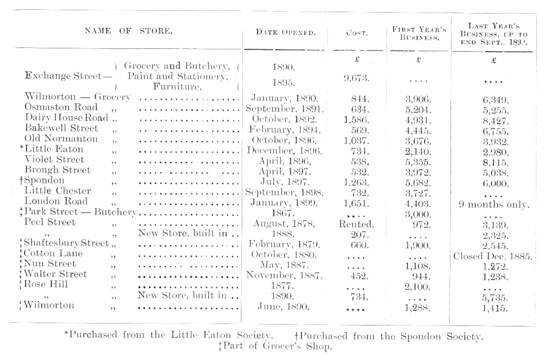

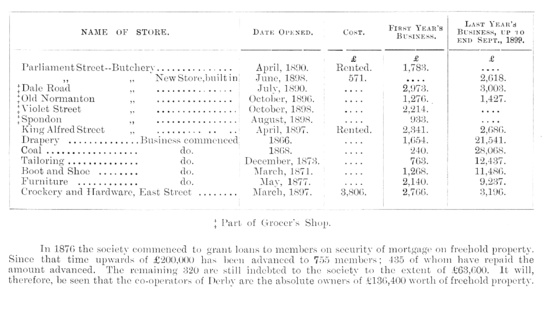

The reader has seen similar notices to these in various

pages. Indeed, they are scattered everywhere about the minutes and

publications of the society's proceedings, but not repeated here, to

obviate the monotony of their collected repetition. Mr. J. B. Rest,

the secretary, has compiled me an excellent Table of the Branches,

including the dates of their origin, their cost, the first and last year

of their business, to September, 1899. The reader will find the

Table at the end of this chapter.

The most picturesquely situated store is Bridge Gate.

It occupies part of the old Toll Gate. Could we recall all that has

been witnessed from those windows, what myriad memories of love and

tragedy, intrigue, and business would be revived! What historic scenes

has the Derwent presented upon which the Bridge House looks down! The date

of the Bridge Gate house—the date of the Bridge is conceivable, but the

Derwent is as old as England, and every yard of its banks has its romantic

history to those conversant with its past. The building occupied by the

store is irregular, with its makeshift rooms. Were it the property of the

co-operators they would soon rebuild it, and make it convenient and

graceful. Yet in such alterations as it has been possible to make, there

are light and cleanliness. These excellencies of co-operative trade are to

be observed in all the stores. In whatever state of confinement,

confusion, and ramshacklement a building was found to be when the

co-operative occupation of it began, changes were made as far as possible

in respect of light, space, drainage, and ventilation. It will be seen in

another chapter that the Building Department had always similar

considerations in view.

One or two societies were acquired which originated

independently, but without self-growing power, such as Little Eaton, taken

over in 1896, and Spondon in 1897. Spondon had been in existence 23 years

and Little Eaton 16 years when they were taken over, both at a valuation.

Both were struggling little stores. Spondon and Little Eaton are two

villages three miles from Derby. These societies were going down and would

soon have been extinct. Now, as branches of the Derby Society, they are in

a flourishing condition both as regards trade and profit.

There is the case of another addition to the list of branches. The

Melbourne Society, seven miles from Derby, had been in a poor state for

years and it is likely the members will lose all the capital they have in

it. The Derby Society have agreed to take the society over, which will be

done in this Jubilee year, and instead of having no dividend they will

have the same as the Derby Society, which averages 2s. 6d. in the £. These

societies are not annexed by any Bartle Frere process. No Rhodes and

Jameson Raid is organised against them in Derby. Overtures from them are

first made, a sort of William Penn Treaty follows and the interests valued

and paid or guaranteed before their occupancy is effected.

The good feeling of cordiality and loyalty existing between the branches

and the Central Society is due to wise, considerate, and to use a phrase

common among diplomatists at this time—"tactful administration." In

ill-governed countries there is always a party who are "against" the

government, because the government have always been against them. In

Sicily there is the Mafia Society which represents an unorganised but

perennial hostility to the governing class and all its ways. In Naples

there are the Camorra, a like irreconcilable class who are unappeasable,

because they are hopeless. There are

no Mafias or Camorra among the 37 outlying branches. They have all one

interest of common privileges and common advantages. There can be no

better tribute to the wisdom of management with which their affairs are

conducted.

The creation and federation of branches is the sign of a great society

possessing the propagandist spirit. The object of this chapter is to give

the reader some adequate conception of the extent to which this work has

been accomplished. Every branch has a history of its own, did space permit

of it being written here, a delightful and instructive book might be made,

by recounting in detail the origin, vicissitudes, growth,

and fortune of branches, and the men who built them up. A deserved

recognition in co-operative annals is due to them.

The numerous branches and departments all have managers and assistants,

and on their good sense, willingness, and courtesy, the welfare of the

society depends. The success of a branch is largely owing to the manners,

patience, and willingness, of those in charge of its business. Purchasers

naturally expect consideration as well in the shop of their own, as in the

shop of a private trader. Every customer is of the nature of a patron,

custom supports the movement in commercial respects, and he who gives his

custom, helps in making the business profitable. A forbidding countenance,

irritability, or impatience, on the part of those who serve, soon

alienates purchasers, who will not go where they think themselves

unwelcome or troublesome. A thoughtless remark which gives pain, will

create dislike, sometimes a mere tone will do it. Of course the duty of

being equable on the part of servants who are as busy as they can be, is