|

CHAPTER I.

CONCERNING BYGONES (PREFATORY)

|

|

|

(1817-1906)

Photograph by Elliott & Fry. |

IT was a saying of Dryden that "Anything, though

ever so little, which a man speaks of himself, in my opinion, is still too

much." This depends upon what a writer says. No man is

required to give an opinion of himself. Others will do that much

better, if he will wait. But if a man may not speak of himself at

all—reports of adventure, of personal endeavour, or of service, will be

largely impossible. To relate is not to praise. The two things

are quite distinct. Othello's imperishable narrative of his love of

Desdemona contained no eulogy of himself. A story of observation, of

experience, or of effort, or estimate of men or of opinions, I may venture

upon—is written for the reader alone. The writer will be an

entirely negligible quantity.

Lord Rosebery, who can make proverbs as well as cite them,

lately recalled one which has had great vogue in its day, namely, "Let

bygones be bygones." Life would be impossible or very unpleasant if

every one persisted in remembering what had better be forgotten.

Proverbs are like plants: they have a soil and climate under which alone

they flourish. Noble maxims have their limitations. Few have

universal applicability. If, for instance, the advice to "let

bygones be bygones" be taken as universally true, strange questions arise.

Are mistakes never more to teach us what to avoid? Are the errors of

others no more to be a warning to us? Is the Book of Experience to

be closed? Is no more history to be written? If so philosophy

could no longer teach wisdom by examples, for there would no longer be any

examples to go upon. If all the mistakes of mankind and all the

miscalculations of circumstance be forgotten, the warnings of the sages

will die with them.

He who has debts, or loans not repaid, or promises not kept,

or contracts unfulfilled in his memory, had better keep them there until

he has made what reparation he can. The Bygone proverb does not

apply to him. There are other derelictions of greater gravity than

fall under the head of intellectual petty larceny, such as the conscious

abandonment of principle, or desertion of a just cause, which had better

be kept in mind for rectification.

If an admiral wrecked his ships, or a general lost his army,

or a statesman ruined his country, by flagrant want of judgment—ever so

conscientiously—it is well such things should be borne in mind by those

who may renew, by fresh appointment, these opportunities of calamity.

It would be to encourage incapacity were such bygones consigned to

oblivion. It may be useless to dwell upon "spilt milk," but further

employment of the spiller may not be prudent.

Slaves of the saying, "Let bygones perish," would construct

mere political man-traps, which never act when depredators are about.

In human affairs bygones have occurred worth remembering as guides for the

future.

It is said that "greatness is thrust upon a man"—what is

meant is a position of greatness. Greatness lies in the quality of

the individual, and cannot be "thrust" on any man. It is true that

intrinsic greatness is often left unrecognised. It would be a crime

against progress were these cases, when known, consigned to forgetfulness.

Noble thoughts as well as noble acts are worth bearing in mind, however

long ago they may have occurred.

My friend Joseph Cowen, who from his youth had regarded me as

a chartered disturber of the unreasoning torpidity of the public

conscience, described me as an agitator. All the while I never was a

Pedlar of Opinions. I never asked people to adopt mine, but to

reason out their own. I merely explained the nature of what I took

to be erroneous in theological and public affairs. Neither did I

find fault with prevailing ideas, save where I could, or thought I could,

suggest other principles of action more conducive to the welfare of all

who dwell in cottages or lodgings—for whom I mainly care. I was for

equal opportunities for all men, guaranteed by law, and for equitable

participation in profit among all who, by toil of hand or brain,

contributed to the wealth of the State.

Yet, though I never obtruded my convictions, neither did I

conceal them. No public questioner ever went empty away,—if his

inquiry was relevant and I had the knowledge he sought. Sometimes,

as at Cheltenham (in 1842), when an inquiry was malicious and the reply

penal, the questioner got his answer. My maxim was that of Professor

Blackie:

"Wear thy heart not on thy sleeve,

But on just occasion

Let men know what you believe,

With breezy ventilation." |

Thus, without intending it, I came to be counted an "agitator."

As to the matter of the following pages, they relate, as all

autobiographical reminiscences do, to events that are past. But whether

they relate to acts, or events, or opinions, to tragedy or gaiety, they

are all meant to fulfil one condition—that of having instruction or

guidance of some kind in them-which bring them within the class of "

bygones worth remembering."

One day as I was walking briskly along Fleet Street, a person in greater

haste than myself running down Johnson's Court collided with me, and both

of us fell to the ground.

On rising, I said, "If you knocked me down, never mind; if I knocked you

down, I beg your pardon." He did not reciprocate my forgiveness, thinking

I had run against him

intentionally. Nevertheless, I say to any resenting reader who does me

mischief, "never mind." If I have done him any harm it has been

unwittingly, and I tender him real

apologies.

CHAPTER II

PERSONAL INCIDENTS.

THESE pages being autobiographic in their nature, something must be said

under this head.

I was born April 13, 1817, which readers complained I omitted to state

in a former work [1] of a similar kind to this, probably thinking it a "Bygone" of no importance.

*

*

*

It was in 1817 that Robert Owen informed mankind that "all the

religions in the world were in error," which was taken to mean that they

were wrong

throughout; whereas all the "Prophet of the City of London Tavern" sought

to prove was that all faiths were in error so far as they rested on the

dogma that men can believe if

they will—irrespective of evidence whatever may be the force of it before

them. Mr. Owen's now truistical statement set the dry sticks of every

church aflame for seventy years.

In many places the ashes smoulder still. By blending Theology with

Sociology, the Churches mixed two things better kept apart. Confusion

raged for years on a thousand

platforms and pulpits. I mention this matter because it was destined to

colour and occupy a large portion of my life.

*

*

*

The habit of my thoughts is to run into speeches, as the thoughts of a

poet run into verse; but if there be a more intrinsic characteristic of my

mind it is accurately described

in the words of Coleridge:

"I am by the law of my nature a Reasoner. A person who should suppose I

meant by that word, an arguer, would not only not understand me, but would

understand the

contrary of my meaning. I can take no interest whatever in hearing or

saying anything merely as a fact—merely as having happened. I must refer

to something within me

before I can regard it with any curiosity or care. I require in everything

a reason why the thing is at all, and why it is there or then rather than

elsewhere or at another time."

This may be why I entitled the first periodical edited in my name, The

Reasoner.

*

*

*

My firstborn child, Madeline, perished while I was in Gloucester Prison.

[2] There is no other word which described what

happened in 1842. In 1895 (as I had always intended), I had a brass

tablet cast bearing the simple inscription—

|

"Near this spot was buried

MADELINE,

Daughter of George Jacob and Eleanor Holyoake,

WHO PERISHED

October, 1842." |

This tablet I had placed on the wall over the grave where the poor child

lay. The grave is close to the wall. The cemetery authorities had

objections to the word "Perished."

When I explained to them the circumstances of Madeline's death, they

permitted its erection, on my paying a cemetery fee of two guineas. The

tablet will endure as long as

the cemetery wall lasts. The tablet is on the left side of the main

entrance to the cemetery, somewhat obscured by trees now.

*

*

*

Dr. Samuel Smiles published a book on Self Help in 1859. In 1857, two

years earlier, I had used the same title "Self-Help by the People." In a

later work, "Self-Help, a

Hundred Years Ago," the title was continued. I had introduced it into

Co-operation, where it became a watchword. I have wondered whether Dr.

Smiles borrowed the name

from me. He knew me in 1841, when he was editing the Leeds Times to which

I was a contributor. He must have seen in Mill's " Principles of

Political Economy," "Self-Help by the People—History of Co-operation in Rochdale," quoted in

Mill's book (book iv. chap, viii.),

The phrase "Science is the Providence of Life" was an expression I had

used in drawing up a statement of Secular Principles twenty-four years

before I found it in the poem

of Akenside's.

*

*

*

Two things of the past I may name as they indicate the age of opinions, by

many supposed to be recent. Co-operators are considered as intending the

abolition of

competition, but as what we call nature—human, animal, and insect—is

founded upon competition, nobody has the means of abolishing it. In the

first number of the Reasoner,

June 3, 1846, in the first article, I stated that Mr. Owen and his friends

proclaimed co-operation as the "Corrector of the excesses of competition

in social life"—a much more

modest undertaking than superseding it.

*

*

*

The second thing I name that I wrote in the same number of the Reasoner

is a short paper on "Moral Mathematics," setting forth that there is a

mathematics of morality as well as of lines and angles. There are

problems in morality, the right solution of which contributes as much to

mental discipline as any to be found in Euclid. These I thus set

forth—

Problem 1.

Given—an angry man to answer without being angry yourself.

Problem 2.

Given—an opponent full of bitterness and unjust insinuations to reply to

without asperity or stooping to counter insinuations.

Problem 3.

Given—your own favourite truths to state without dogmatism, and to praise

without pride, adducing with fairness the objections to them without

disparaging the judgment of

those who hold the objections.

Problem 4.

Given—an inconsistent and abusive opponent. It is required to reply to

him by argument, convincing rather than retorting. All opportunities of "thrashing" him are to be

passed by, all pain to be saved him as far as possible, and no word set

down whose object is not the opponent's improvement.

Problem 5.

Given—the error of an adversary to annihilate with the same vigour with

which you could annihilate him.

Problem 6.

Required—out of the usual materials to construct a public body, who shall

tolerate just censure and despise extravagant praise.

*

*

*

One day I found a piece of twisted paper which I picked up thinking I had

dropped it myself. I found in it a gold ring with a snake's head. It was

so modest and curious that I

wore it. Four years after, on a visit to Mr. W. H. Duignan, at Rushall

Hall, on the border of Cannock Chase, I lost it. Four days later I arrived

by train at Rugby Station with

live heavy-footed countrymen. I went to the

refreshment room. On my return only one man was

in the carriage. The sun was shining brightly on the carriage floor, and

there in the middle, lay, all glittering and conspicuous, my lost ring

unseen and untrodden. I picked

it up with incredulity and astonishment. How it came there or could come

there, or being there, how it could escape the heavy feet of the

passengers who went out, or the

eyes of the one remaining, I cannot to this day conceive. After I had lost

it, I had walked through Kidderminster, Dudley Castle, and Birmingham, and

searched for it several

times. I had dressed and undressed four times. I lost it finally during

Lord Beaconsfield's last Government, at the great Drill Hall meeting at

Blackheath, [3] in a jingo crush

made to prevent Mr. Gladstone entering to speak there

on the Eastern policy of that day. In future times should the ground be

excavated, the spot where I stood will be marked with gold—the only place

so marked by me in

this world.

It is probably vanity—though I disguise it under the name of pride—that

induces me to insert here certain incidents. Nevertheless pride is the

major motive. When I have been

near unto death, and have asked myself what has been the consolation of

this life, I found it in cherished memories of illustrious persons of

thought and action, whose

friendship I had shared. There are other incidents —as Harriet Martineau's Letter to Lloyd Garrison, Tyndall's testimony, elsewhere

quoted—which will never pass from my

memory.

*

*

*

The first dedication to me was that of a poem by Allen Davenport, 1843—an

ardent Whitechapel artisan. The tribute had value in my eyes, coming from

one of the toiling

class—and being a recognition on the part of working men of London,

that I was one of their way of thinking and could be trusted to defend the

interests of industry.

*

*

*

The next came from the theological world—a quite unexpected incident in

those days. The Rev. Henry Crosskey dedicated his "Defence of Religion "

to me. He was of the

priestly profession, but had a secular heart, and on questions of freedom

at home and abroad he could be counted upon, as though he was merely

human. The dedication

brought Mr. Crosskey into trouble with Dr. Martineau. Unitarians were

personally courteous

to heretics in private, but they made no secret that they were disinclined

to recognise them in public. Dr. Martineau shared that reservation.

Letter from Dr. James Martineau to Rev. W. H. Crosskey:—

"It is very difficult to say precisely how far our respect for honest

conviction, and indignation at a persecuting temper, should carry us in

our demonstrations towards men

unjustly denounced. I do confess that, while I would stoutly resist any ill-usage of such a man as Holyoake, or any attempt to gag him, I could

hardly dedicate a book to him:

this act seeming to imply a special sympathy and admiration directed upon

that which distinctively characterises the man. Negative defence from

injury is very different from

positive homage. After all, Holyoake's principles are undeniably more

subversive of the greatest truths and genuine basis of human life than the

most unrelenting orthodoxy.

However, it is a generous impulse to appear as the advocate of a man whom

intolerance unjustly reviles." [4]

Thus he gave the young minister to understand—that while there was

nothing wrong in his having respect for me, he need not have made it

public. At that time it was chivalry

in Mr. Crosskey to do what he did, for which I respected him all his days.

.

A third dedication I thought more of, and still value, came from the

political world, and was the first literary testimony of my interest in

it. It came from "Mark Rutherford"

(William Hale White), who knew everything I knew, and a good deal more. He

inscribed to me, 1866, a remarkable "Argument for the Extension of the

Franchise," which

had all the characteristics of statement, which have brought him renown in

later years. He said in his prefatory letter to me: "If my argument does

any service for Reform,

Reformers will have to thank you for it, as they have to thank you for a

good many other things." They were words to prize.

*

*

*

Recently a letter came from Professor Goldwin Smith,

who was Cobden's admiration and envy, as he once told me, for the power of

expressing an argument or a career in a sentence. His letter to me

was as follows:—

"You and I have lived together through many eventful and changeful years.

The world in these years has, I hope and believe, grown better than it was

when we came into it.

In respect of freedom of opinion and industrial justice, the two objects

to which your life has been most devoted, real progress has certainly been

made."

The main objects of my life are here distinguished and expressed in six

words.

*

*

*

Reviewers of the autobiographic volumes preceding these, complained that

they contained too little about myself. If they read the last four

paragraphs given here they will be

of opinion that I have said enough now.

*

*

*

At the Co-operative Congress held in Gloucester, 1879, a number of

delegates went down to see the gaol. When they arrived before it, Mr.

Abraham Greenwood, of Rochdale,

exclaimed, "Take off your hats, lads! That's where Holyoake was

imprisoned." They did so. That incident—when it was related to

me—impressed me more than any thing else

connected with Co-operation. I did not suppose those tragical six months

in that gaol were in the minds of co-operators, or that any one had

respect for them.

*

*

*

The chapter, "Things which went as they Would," shows that serving

co-operators had its inconveniences, but there were compensatory incidents

which I recount with

pleasure. One was their contribution to the Annuity of 1876, which Mr.

Hughes himself commended to them at the London Congress. It was owing to

Major Evans Bell and

Mr. Walter Morrison that the project was successful.

*

*

*

The other occurred at the Doncaster Congress, 1903. In my absence a

resolution had been passed thanking me for services I had rendered in Ten

Letters in Defence of

Co-operation. When I rose to make acknowledgment, all the large audience

stood up. It was the first time I had ever been so received anywhere,

showing that

services which seemed un-noted at the time, lived in remembrance.

Here I may cite a letter from Wendell Phillips, Of the

great American Abolitionists, Phillips, with his fine presence and

intrepid eloquence, was regarded as the "noblest Roman of them all."

Theodore Parker, he described to me as the Jupiter of the pulpit; and

Russell Lowell has drawn Lloyd Garrison, in the famous verse—

"In a dark room, unfriended and unseen,

Toiled o'er his types, a poor unlearn'd young man.

The place was low, unfurnitured and mean,

But there the freedom of a race began." |

I corresponded with them in their heroic days. It is one of the letters of

Phillips to me I quote here:—

BOSTON,

"July 22, 1874.

"MY DEAR SIR,—I ought long ago to have thanked you for sending me copies

of your pamphlets on John Stuart Mill and the Rochdale Pioneers and with so

kind and

partial a recognition of my co-operation with you in your great cause.

"That on Mill was due certainly to a just estimate of him, but how sad

that human jackals should make it necessary. That on Co-operation I read

and read again, welcoming

the light you throw on it, for one of my most hopeful stepping-stones to a

higher future. Thank you for the lesson—it cleared one or two dark

places—not the first by any

means—for I've read everything of yours I could

lay my hands on. There was one small volume on Rhetoric—'Public Speaking

and Debate,' methods of address, hints towards effective speech,

etc.—which I studied

faithfully, until some one to whom I had praised and lent it, acting

probably on something like Coleridge's rule, that books belong to those

who most need then—never returned

me my well-thumbed essay, to my keen regret. Probably you never knew that

we had printed your book. This was an American reprint—wholly

exhausted—proof that it did

good service. We reprinted, some ten years ago, one of your wisest tracts,

the 'Difficulties that obstruct Co-operation.' It did us yeoman service. But enough, I

shall beg you to accept a volume of old speeches printed long ago, because

it includes my only attempt to criticise you—which you probably never

saw. In it I will put,

when I mail it, the last and best photograph of Sumner, and if you'll

exchange, I'll add one of

"Yours faithfully, and ever,

"WENDELL PHILLIPS.

"Mr. G. J. Holyoake."

*

*

*

With Mr. Charles Bradlaugh I had personal relations all his life. I took

the chair for him at the first public lecture he delivered. I gave him

ready applause and

support. At the time of what was called his "Parliamentary struggle," I

was entirely

with him and ready to help him. It was with great reluctance and only in

defence of principle, to which I had long been committed, that I appeared

as opposed to him.

He claimed to represent Free Thought, with which I had been identified

long before his day. My conviction was that a Free Thinker should have as

much courage,

consistency, and self-respect as any Apostle, or Jew, or Catholic,

or Quaker. All had in turn refused to make a profession of opinion they

did not hold, at the peril of death, or, as in the case of O'Connell and

the Jews, at the certainty

of exclusion from Parliament. They had only to take an oath, to the terms

of which they could not honestly subscribe. Mr. Bradlaugh had no scruple

about doing

this. In the House of Commons he openly kissed the Bible, in which he did

not believe—a token of reverence he did not feel. He even administered to

himself the oath, which was contrary to his professed convictions.

This seemed to be a reflection upon the honour of Free Thought. Had

I not dissented from it, I should have been a

sharer in the scandal, and Free Thought—so far as I represented it—would

have been regarded as below the Christian or Pagan level.

The key to Mr. Bradlaugh's character, which unlocks the treasure-house of

his excellences and defects, and enables the reader to estimate him

justly, is the perception that

his one over-riding motive and ceaseless aim was the ascendancy of the

right through him. It was this passion which inspired his best efforts,

and also led to certain aberration of action. But what we have to

remember now, and permanently, is that it was ascendancy of the right in political and theological

affairs that he mainly

sought for, fought for, and vindicated. It is this which will long cause

his memory to be cherished.

At the time of his death I wrote honouring notices of his career in the

Bradford Observer and elsewhere, which were reproduced in other papers. Otherwise, I found opportunity

on platforms of showing my estimate of his character and public services. I had never forgotten an act of kindness he had, in an interval of

goodwill, done me. When

disablement and blindness came in 1876, he collected from the readers of

his journal £170 towards a proposed annuity for me. It was a great

pleasure to me to

repay that kindness by devising means (which others neither thought of nor

believed in) of adding thrice that sum to the provision being made for his

survivors. It was a merit

in him that devotion to pursuits of public usefulness did not, in his

opinion, absolve him from keeping a financial promise, as I knew, and have

heard friends who aided him

testify—a virtue not universal among propagandists. No wonder the coarse

environments of his early life lent imperiousness to his manners. In later

years, when he was in the

society of equals, where masterfulness was less possible and less

necessary, he acquired courtesy and a certain dignity—the attribute of

conscious power. He was the

greatest agitator, within the limits of law, who appeared in my time among

the working people. Of his own initiative he incurred no legal danger, and

those who followed him

were not led into it. He was a daring defender of public right, and not

without genius in discovering methods for its attainment. One form of

genius lies in discovering

developments of a principle which no one else sees. Had he lived in the

first French Revolution, he had ranked with Mirabeau and Danton. Had he

been with Paine in

America, he had spoken "Common Sense" on platforms. He died before being

able to show in Parliament the best that was in him. Though he had no

College training like

Professor Fawcett, Indian lawyers found that Mr. Bradlaugh had a quicker

and greater grasp of Indian questions than the Professor. It was no mean

distinction—it was,

indeed, a distinction any man might be proud to have won—that John Stuart

Mill should have left on record, in one of his latest works, his testimony

to Mr. Bradlaugh's

capacity, which he discerned when others did not. Like Cobbett, the

soldiers' barracks did not repress Bradlaugh's invincible passion for the

distinction of a political

career. In the House of Commons he took, both in argument and debate, a

high rank, and surpassed compeers there of a thousand times his advantages

of birth and

education. That from so low a station he should have risen so high, and,

after reaching the very platform of his splendid ambition, he should die

in the hour of his opportunity

of triumph, was one of the tragedies of public life, which touched the

heart of the nation, in whose eyes Mr. Bradlaugh had become a commanding

figure.

*

*

*

It was in connection with the controversy concerning the Oath that I

received a letter from John Stuart Mill, which when published in the Daily

News, excited much surprise.

Mr. Mill was of opinion, that the oath, being made the condition of

obtaining justice, ordinary persons might take it. But one who was known

to disbelieve the terms of it, and

had for years publicly written and spoken to that effect, had better not

take it. This was the well-known Utilitarian doctrine that the

consequences of an act are the justification

of it. Francis Place had explained to me that Bentham's doctrine aas that

the sacrifice of liberty or life was justifiable only on the ground that

the public gained by it. A

disciple should have very strong convictions who differs from his master,

and I differ with diffidence from Mr. Mill as to the propriety of carrying

the Utilitarian doctrine into the

domain of morals. Truth is higher than utility, and goes before it. Truth

is a measure of utility, and not utility the measure of truth.

Conscience is higher than consequence. We are bound first to consider what is right. There may be in

some cases, reasons which justify departure from the right. But these are

exceptions.

The general rule is—Truth has the first claim upon us.

To take an oath when you do not believe in an avenging Deity who will

enforce it, is to lie and know that you lie. This surely requires

exceptional justification. It is

nothing to the purpose to allege

that the oath is binding upon you. The security of

that are the terms of the oath. The law knows no other. To admit the terms

to be unnecessary is to abolish the oath.

*

*

*

When a youth, attending lectures at the Mechanics' Institution, I soon

discerned that the more eminent speakers were the clearer. They knew their

subjects, were masters

of the outlines, which by making bold and plain, we were instructed. Outline is the beginning of art and the charm of knowledge. Remembering

this, I found no

difficulty in teaching very little children to write in a week.

It is a great advantage to children to take care that their first notions

are true. The primary element of truth is simplicity—with children it is

their first fascination. I had only to

show them that the alphabet meant no more than a line and a circle. A

little child can make a "straight stroke" " and a round

O."

The alphabet is made up of fifteen straight line and eleven curved line

letters. The root of the fifteen straight line letters is | placed in

various ways. The root of the eleven

curved line letters is O or parts of

O and | joined together.

A is made by two straight lines leaning against each other at the top, and

a line across the middle.

H is made of two upright lines with a straight line between them.

V is made of two straight lines meeting at the bottom. If two upright

lines are added to the V it becomes

M.

Two V's put together make

W. The letters

L and T and

X and Z make

themselves, so easy is it to place the straight lines which compose them.

O makes itself. A short line makes it into

Q. If

the side of O be left open it is a

C. If two half

O's are joined together they make

S. Half O and

an upright line make D. An upright line and a half

O make P. Another half added and

B is made.

After a second or third time a child will understand the whole alphabet.

Such is the innate faculty of imitation and construction in children that

they will put the letters together themselves when the method is made

plain to them, and within a

week will compose their own name and their mother's. At the same time they

learn to read as well as to write. What they are told they are apt to

forget, what they write they

remember.

Reason is the faculty of seeing what follows as a consequence from what

is, but to define distinction well is a divine gift. My one aim was to

make things clear.

*

*

*

One of my suggestions to the young preachers, who had two sermons on

Sunday to prepare, was that they should give all their strength to the

evening discourse and

arrange with their congregation to deliver the other from one of the old

divines of English or Continental renown, which would inform as well as

delight hearers. It would

be an attraction to the outside public. Few congregations know anything of

the eloquence, the happy and splendid illustrations and passages of

thought to be found in the

fathers of the Church of every denomination. Professor Francis William

Newman, whose wide knowledge and fertility of thought had few equals in

his day, told me that he

should shrink from the responsibility of having to deliver a proficient

and worthy discourse fifty-two times a year. Anyhow, for the average

preacher, better one bright ruddy

discourse, than two pale-faced sermons every Sunday.

*

*

*

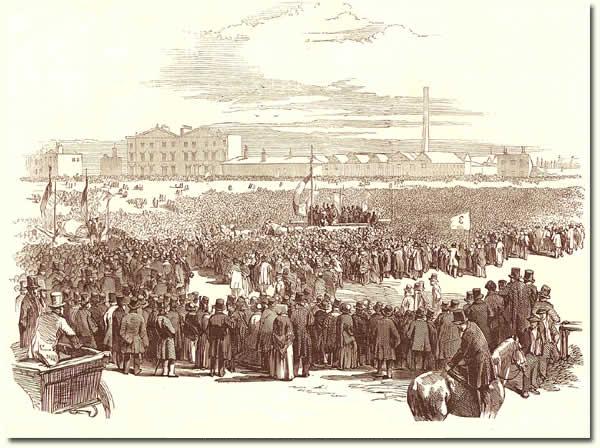

Those who remained true to Chartism till the end of it are recorded in the

following paragraph under the title of the "National Charter

Association," which appeared in Reynolds's Newspaper, January

4, 1852 :—

"On Wednesday evening last, the scrutineers appointed by the metropolitan

localities attended at the office, 14, Southampton Street, Strand, and

having inspected the votes received, gave the following as the result, in

favour of the following nine:—

Ernest Jones (who received 900 votes), Feargus O'Connor, John Arnott, T.

M. Wheeler, James Grassby, John Shaw, W. J. Linton, J. J. Bezer, G. J.

Holyoake.

"Messrs. J. B. O'Brien, Gerald Massey, and Arthur Trevelyan having

declined to serve, the votes received on their behalf have not been

recognised.

"We, the undersigned, hereby declare the nine persons first named to be

duly elected to form the Executive Committee for the ensuing year.

"JOHN WASHINGTON, City Locality.

"EDWD. JOHN LOOMES, Finsbury Locality.

"December 31, 1851."

*

*

*

After I became an octogenarian, I was asked whether my years might be

ascribed to my habits. I could only explain what my habits were. In the

first half of my life I ate

whatever came to hand, and as not enough came I easily observed moderation. But then I was disposed to be moderate on principle, having read in

the Penny Magazine, about 1830, that Dr. Abernethy told a lady "she might

eat anything eatable in moderation." In the second and later half of my

life I gave heed to Carnaro, and sought to limit each meal to the least

quantity

necessary for health. The limitation of quantity included liquids as well

as solids, decreasing the amount of both "in relation to age and

activity," as Sir Henry Thompson

advised. Not thinking much of meat, I limited that to a small amount, and

cereals to those that grow above ground. A tepid bath for the eye (on the

recommendation of the

Rev. Dr. Molesworth, of Rochdale) and a soap bath for the body every

morning ends the catalogue of my habits.

My general mode of mind has been to avoid excess in food, in pleasure, in

work, and in expectation. By not expecting much, I have been saved from

worry if nothing came.

When anything desirable did arrive, I had the double delight of

satisfaction and surprise. Shakespeare's counsel

|

"Be not troubled with the tide which bears

O'er thy contents its strong necessities,

But let determined things to destiny

Hold, unbewailed their way"— |

ought to be part of every code of health.

The conduciveness of my habits to longevity may be seen in this. More than

forty of my colleagues, all far more likely to live than myself, have long

been dead. Had I been as

strong as they, I also should have died as they did. Lacking their power

of hastening to the end, I have lingered behind.

For the rest—

|

"From my window is a glimpse of sea

Enough for me,

And every evening through the window bars

Peer in the friendly stars." |

The principles and aims of earlier years are confirmed by experience at

88. Principles are like plants and flowers. They suit only those whom they

nourish. Nothing is adapted

to everybody.

Goethe said: "When I was a youth I planted a cherry-tree, and watched its

growth with delight. Spring frost killed the blossoms, and I had to wait

another year before the

cherries were ripe—then the birds ate them—another year the caterpillars

ate them—another year a greedy neighbour stole them—another year the

blight withered them.

Nevertheless, when I have a garden again, I shall plant another

cherry-tree." My years now are "dwindling to their shortest span"; if I

should have my days over again, I shall

plant my trees again—certain that if they do grow they will yield verdure

and fruit in some of the barren places of this world.

CHAPTER III.

OTHER INSTANCES

MY first public discussion in London was with Mr.

Passmore Edwards—personally, the handsomest adversary I ever met. A

mass of wavy black hair and pleasant expression made him picturesque.

He was slim, alert, and fervid. The subject of debate was the famous

delineation of the Bottle, by George Cruikshank, which I regarded as a

libel on the wholesome virtue of Temperance. Exaggerations which

inform and do not deceive, as American humour, or Swift's Lilliputians,

Aztecs, and giants of Brobdingnag, have instruction and amusement.

The exaggeration intended to deride and intimidate those who observe

moderation is a hurtful and misleading extreme. Mr. Edwards took the

opposite view. Cruikshank could not be moderate, and he did right to

adopt the rule of absolute abstinence. It was his only salvation.

To every man or woman of the Cruikshank tendency I would preach the same

doctrine. To all others I, as fervently, commend the habit of use

without abuse. Without that power no man would live a month.

Had Mr. Edwards been of this way of thinking, there had been no debate

between us.

Mr. Edwards had much reason on his side. Mankind are

historically regarded as possessing insufficiency of brains, and it is bad

economics to put an incorrigible thief into their mouths to steal away

what brains they have.

I had respect for Mr. Edwards' side of the argument.

For when a man makes a fool of himself, or fails to keep an engagement, or

departs, in his behaviour from his best manner—through drink—he should

take the next train to the safe and serene land of Abstinence.

The first person who mentioned to me the idea of a halfpenny

newspaper was Mr. Passmore Edwards. One night as we were walking

down Fleet Street from Temple Bar, when the Bar stood where the Griffin

now stands. Mr. Edwards asked me, as I had had experience in the

publishing trade whether I thought a halfpenny newspaper would pay, which

evidently had for some time occupied his mind. The chief difficulty I

foresaw was, would newsagents give it a chance? It afterwards cost the

house of Cassells'—the first to make the experiment—many thousands. The

Workman, in which I had a department, was intended, I was told, to be a

forerunner of the halfpenny paper. But that title would never do, as I

ventured to predict. Workmen, as a rule with no partnership in profits,

had enough of work without buying a paper about it. Tradesmen,

middle-class and others, did not want to be taken for workmen, and the

Workman was discontinued. But, strange to say, the same paper issued

under the title of Work became successful. Everybody was interested

in work but not in being workmen. Such are the subtleties of titles! Their right choice—is it art or instinct? The Echo was the name

fixed upon for the first halfpenny paper. Echo of what? was not indicated. It excluded expectations of originality. Probably curiosity was the charm.

It committed no one to any side. There were always more noises about than

any one could listen to, and many were glad to hear the most articulate. I

wrote articles in the earliest numbers under the editorship of Sir Arthur

Arnold.

* *

*

The House of Allsop, as known to the world of progress in the last

century, is ended. The first who gave it public interest was Thomas Allsop,

who assisted Robert Owen in

1832 in the Gray's Inn Lane Labour Exchanges. He was a watchful assistant

of those who contributed to the public service without expecting or

receiving requital. His

admiration of genius always took the form of a gift—a rare but

encouraging form of applause. Serjeant Talfourd somewhere bears testimony

to the generous assistance Mr.

Allsop rendered to Hazlitt, Lamb, and Coleridge. To Lamb, he continually

sent gifts, and Coleridge dined at his table every Sunday for nineteen

years. Landor, who had always nobility of character, and was an impulsive

writer—represented Mr. Allsop's interest in European freedom as

proceeding from "vanity," forgetful of his own letter to Jessie Meriton

White, offering £100 to any assassin of Napoleon III.; and John Forster

preserves Landor's remark

upon Mr. Allsop, but does not, so far as I remember, give Landor's

Assassin Letter. The fact was, no man less sought publicity or disliked it

more than Mr. Allsop. When

Feargus O'Connor was elected member for Nottingham, Mr. Allsop qualified

him by conferring upon him lands bringing an income of £300. He divided

his Lincoln estate into

allotments for working men, but he never mentioned these things himself. His son Robert held his father's intellectual views. His eldest son

Thomas, who was class-mate

with Mr. Dixon Galpin at Queenwood, a considerable landowner in British

Columbia, was the philosopher of the family, and like Archbishop Whately,

had a power of stating

them with ever apt and ready illustrations.

They were like Mr. Owen, Conservative in politics; but in social and

mental matters they were intrepid in welcoming new truth. It was at

Thomas's suggestion that I omitted

his father's

name altogether in my chapter, "Mr. Secretary Walpole and the Jacobin's

Friend." [5] Landor was quite wrong, there was no "vanity" in the Allsop

family. Were Thomas Allsop the younger now living I should not write

these paragraphs. As it is, I may say that I owed to his generosity

an annuity of £100. He commenced it by a subscription of £200,

and by Mr. Robert Applegarth's friendly secretaryship, which had devotion

and inspiration in it, a committee to which the Rev. Dr. Joseph Parker,

with his intrepid tolerance,

gave his name, was formed, and an annuity of £100 was purchased for me.

* *

*

|

|

|

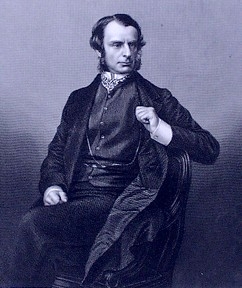

Joseph Parker

(1830-1902) |

When the Taxes on Knowledge were repealed, Mr. Collet and I attempted to

procure the repeal of the Passenger Tax on Railways. For forty years after

the imposition of the

tax of Lord Halford, 1832, the workman was taxed who went in search of an

employer. When a poor sailor, arriving in London after a long voyage,

desired to visit his poor

mother in Glasgow, the Government added to his fare a tax of three

shillings, to encourage him in filial affection. In the interests of

locomotion and trade, two or three

associations had attempted to get this pernicious tax repealed, without

success. It was remarked in Parliament in 1877 that no committee

representing the working class

asked for the repeal of this discreditable impost, which most concerned

them. This was the reason of the formation of the Travelling Tax Abolition

Committee, of which Mr. Collet became secretary and the chairman. We

were

assisted by an influential committee of civic and industrial leaders. After six years' agitation we were mainly instrumental (that was in Mr.

Gladstone's days) in obtaining the

repeal of the penny a mile tax on all third-class fares, effected by Mr.

Childers in 1883, which ever since has put into the pocket of

working-class travellers £400,000 a year,

besides the improved carriages and improved service the repeal has enabled

railway companies to give. We continued the committee many years longer in

the hope of

freeing the railways wholly from taxation, which still hampers the

directors and is obstructive of commerce. I was chairman for twenty-four

years, during which time twenty-two

of the committee died. Our memorials, interviews with ministers,

correspondence with officials, petitions to Parliament, public meetings

and various publications, involved a

large and incessant amount of work without payment of any kind. Subsequently a committee of publicists, journalists and members of

Parliament, for whom Mr. Applegarth

was the secretary, caused £80 to be given to me, in recognition of my

services. Though it represented less than £4 a year as the salary of the

chairman, it was

valuable in my eyes from the persons who gave it, as they were not the

persons much benefited by the work done, and who really taxed themselves

on behalf of others. A subscription of a halfpenny each from the

working-class travellers who had profited by the

repeal would have amounted to a handsome acknowledgment. But from them it

was impossible to collect it. Testimonials, I believe, are often given by

persons who

generously subscribe for others upon whom the obligation of making it more

properly rests.

It would seem insensibility or ingratitude not to record, that on my

eightieth birthday—now eight years ago—I was entertained at a numerously

attended dinner party in the

National Liberal Club, at which to my gratification, Mr. Walter Morrison

presided. The speakers, and distinction of many in the assembly, were a

surprise, transcending all I

had foreseen. The words of Mr. Morrison's speech, to use Tennyson's words,

were like

|

"Jewels

That on the stretch'd forefinger of all time

Sparkle forever " |

in my memory.

On my eighty-sixth birthday a reception was given me by the Ethical

Society of South Place Chapel, Finsbury—the oldest Free Thought temple in

London, where the duty of free inquiry was first proclaimed by W. J. Fox. The place was filled with

faces familiar and unfamiliar, from near and far, of artists, poets,

publicists, journalists, philosophers, as at the National Liberal Club,

but in greater numbers. Lady

Florence Dixie purchased a large and costly oil painting, [6] and sent it

for me to present to the Library of the Rationalist Press Association. Among the

letters sent was one, the last sent to a public meeting, by Herbert

Spencer. The reader will pardon the pride I have in quoting it.

Writing from 5, Percival Terrace, Brighton, March 28, 1903, Mr. Spencer

said:

"I have not been out of doors since last August, and as Mr.

Holyoake knows, it is impossible

for me to join in the Reception to be given to him on the occasion of his

eighty-sixth birthday. I can do nothing more than express my warm feeling

of concurrence. Not

dwelling upon his intellectual capacity, which is high, I would emphasise

my appreciation of his courage, sincerity, truthfulness, philanthropy, and

unwearied perseverance.

Such a combination of these qualities, it will, I think, be difficult to

find:"

* *

*

For a period I had the opportunity accorded me of

editing a daily newspaper—The Sun. The Rev. Dr. Joseph Parker had been my predecessor. I

was left at liberty to say

whatever I pleased, and I did. In one week I wrote twenty-nine articles. But opulent opportunity of working was afforded me. As I was paid ten

times as much as I had received before, I thought myself in a paradise of

, journalism.

In the correspondence of Robert Owen, now in possession of the

Co-operative Union Memorial Committee, Manchester, is the following letter

from his customary legal

adviser, who then resided at Hornsey.

"6, OLD JEWRY,

LONDON,

"February 17, 1853.

"R. OWEN, Esq.,

"DEAR SIR,—I am glad to see your handwriting upon an envelope conveying

to me a pamphlet of yours.

"Holyoake I expect will breakfast with me on Sunday morning. He comes down

by the railway to Hornsey, which leaves London at nine o'clock precisely.

"I am afraid it is too cold for you, and that the walk from the railway to

our house, which is three quarters of a mile, may not be agreeable.

"Yours truly,

"W. H. ASHURST.

"H. will return about 12 or 1."

After breakfast Mr. Owen walked briskly with me into town. He was then

eighty-two. On his way he explained to me that, when walking as I

often had done from Birmingham to Worcester, or from Huddersfield to

Sheffield—to lecture, I should find it an advantage to use the horse

road, as on the footpath there is

more unevenness and necessity of deviation to allow persons to pass, which

increases the fatigue of a day on foot. So thoughtful and practical was

the reputed visionary.

* *

*

Of letters on public affairs I confine myself to three instances. When the

South Kensington Exhibitions were in force, more than twenty thousand

visitors a day thronged the

Exhibition Road. Mothers with their children had to cross the wide Museum

Road, where policemen, stationed to protect the passengers, had enough to

do to keep their own

toes on their feet, in the undivided traffic of cabs. I wrote to the

Times

suggesting that a lamp should be erected in the middle of the wide road

serving as a light, a retreat, and

a division of traffic. All the cabmen who could write protested against

the danger, or the necessity, and possibility of the proposal. But it was

done, to the great joy of

mothers and advantage to the public.

* *

*

After the fall of the French Assassin at Sedan when Marshal Bazaine was

hanging about Europe in obscurity and ignominy, Mr. Arthur Arnold proposed

that he should be

invited to a banquet in London. Seeing that the citizens of Paris went out

at night in bands of twenty or thirty heroically to

help to raise the siege—on what ground could we offer to honour Bazaine,

who with 192,000 soldiers under his command, was afraid to attempt it?

I

asked the question in the

Press, and the proposal, which had a sentiment of chivalry in it to a

fallen general, and was commanding some concurrence—went out—like the

Marshal—into outer darkness.

* *

*

When public opinion was in the balance respecting the South American War,

Mr. Reverdy Johnson and a Copperhead colleague arrived in London and began

to do a

respectable business in public mystification. From information supplied to

me I wrote letters explaining the real nature of that sinister mission, in

consequence of which the

two emissaries of slavery made tracks for New York.

But of instances, as of other things, there must be an end.

CHAPTER IV.

FIRST STEPS IN LITERATURE

SURELY environment is the sister of heredity? Mr.

Gladstone once said to me that "The longer he lived the more he thought

of heredity." Next to heredity is environment—the moulder of mankind. My

first passion was to be a prize-fighter. Nature, however, had not made me

that way. I had no animosity of mind, and that form of contest was not to

my taste. But prize-fighting was part of the miasma the Napoleonic war had

diffused in England.

It was in the air; it was the talk of the street. "Hammer" Lane, so

called from the iron blow he could deliver, was the local hero of the Ring

in the Midlands in my youth.

He was a courtier of my eldest sister, and created in me a craving for

fistic prowess. I fought one small battle, but found that a lame wrist,

which has remained permanent,

cut me off from any prospect of renown in that pursuit. Next, to be a

circus jester

seemed to me the very king of careers. My idea was to leap into the

arena exclaiming :—

"Well, I never! Did you ever? I never

did.''

"Never did what?" the clown was to ask me, when my reply was

to be:—

"I could only disclose that before a Royal

Commission"—alluding to a political artifice then coming into vogue in

Parliament. When a Minister did not know what to say to a popular

demand, or found it inconvenient to say it if he did know, he would

suggest a Commission to inquire into it, as is done to this day.

Then the clown would demand, "What is the good of a Royal

Commission?" when the answer would be: " Every good in the world to a

Ministry, for before the Commission agreed as to the answer to be given,

the public would forget what the question was." Under this diversion

of the audience, no one noticed that no answer was given to the original

question put to the jester. Whether I could have succeeded in this

walk was never decided. It was found that I lacked the loud,

radiant, explosive voice necessary for circus effects, and I ceased to

dream of distinction there.

I suppose, like many others who could not well write

anything, I thought poetry might be my latent—very latent—faculty.

So I began. For all I knew, my genius, if I had any, might lie that

way. To "body forth things unknown," which I was told poets did,

must be delightful. To "build castles in the air"—as my means did

not enable me to pay ground rent—was at least an economical project.

So I began with a question, as new Members of Parliament do, until they

discover something to say. My first production, which I hoped would

be mistaken for a poem, was in the form of a "Question to a Pedestrian":—

|

"Saw you my Lilian pass this way?

You would know her by the ray

Of light which doth attend her.

Her eye such fire of passion hath,

That none who meet her ever pass,

But they some message send her." |

The critics said to me, as they said to Keats, to whom I bore

no other resemblance, "This sort of thing will never do. It is an

imitation of Shenstone, or of one of the Shepherd and Shepherdess School

of the Elizabethan era"—of whom I knew nothing. So I was lost to

the Muses, who, however, never missed me.

But my career was not ended. I was told there might be

an opening for me in criticism, especially of poetry, as there were many

persons great in the critical line, who could not write a verse themselves

-and yet lived to become a terror to all who could. My first effort

in this direction was upon the book of a young poet whom I knew

personally. Not venturing upon longer pieces at first, I selected

two sonnets—as the author, Emslie Duncan, called them. The opening

was very striking, and was thus expressed:—

"Great God: What is it that I see?

A figure shrimping in the sea." |

How natural is the exclamation, I began. The poet

invokes the Deity on the threshold of a great surprise. Luther did

the same in his famous hymn beginning—

"Great God! What do mine eyes behold!"

Our sonneteer may be said to have borrowed the exclamation

from Luther. [7] But we have no doubt the

exclamation of our poet is purely original. He next demands an

interpretation of his vision. It is early morning, though the poet

does not mention it (great poets are suggestive, and stoop not to detail).

An evasive grey mist spreads everywhere, like the new fiscal policy of the

Bentinckian type (then in the air), obscuring the landmarks of long-time

safety. Still there is one object visible. The poet's eye in

"fine frenzy rolling" sees something. He is not sure of the

personality that confronts him, and with agnostic precaution worthy of

Huxley, he declines to say what it is—until he knows—and so contents

himself with telling the reader it is a "figure" out shrimping. The

scene is most impressive. As amateurs say, when they do not

understand a picture they are praising, "It grows upon you." So this

marvellous sonnet grows upon the reader. If there be not imagination

and profundity here, we do not know where to look for it.

Next our poet returns to town, and in Whitechapel meets with

the statue of a lady attired only in a blouse. Notwithstanding his

astonishment he varies his abjuration, and exclaims

|

"Judge ye gods, of my surprise,

A lady naked in her chemise!" |

This is unquestionably very fine. True, there is some

contradiction in nudity and attire; but splendid contradiction is an

eternal element of poetry. What would Milton's "Paradise Lost" be

without it? The reader cannot tell whether the surprise of the poet

is at the lady or her drapery. There is no use in asking a great

poet what he meant in writing his brilliant lines. If as candid as

Browning, he would answer as Browning did, that "he had not the slightest

idea what he meant." Nothing remains for us but to congratulate the

public on the advent of a new poet who is equally great on subjects of

land or sea.

There is a good deal of reviewing done on this principle, and

reputations made by this sort of writing as fully without foundation, and

I looked forward to further employment.

The editor to whom I sent these primal specimens of my new

vocation seemed undecided what to do with them—throw them into his

waste-paper basket or submit them to his readers. I assured him I

had seen a number of criticisms less restrained than mine, on performances

quite as slender as the sonnets I had described. With kindly

consideration, lest he might be repressing a rising genius in me, he asked

me to give my opinion upon a charming little poem by Longfellow—to

commend, as he hoped I could, as a new edition in which he was interested

was about to be published.

The object of the poet, I found, was to awaken certain young

ladies, whose only fault consisted in getting up late in the morning.

The lines addressed to them, if I rightly remember, began thus:—

"Awake! Arise! and greet the day.

Angels are knocking at the door.

They are in haste and may not stay,

And once departed come no more." |

This verse reminds the readers of Omar Khayyám.

Two ideas in it are his, and the terms used are his; but I resisted this

temptation to imitate those popular critics, whose aim is not to discover

the graces of a new poet, but his plagiarisms, and to show that everybody

reproduces the ideas of everybody else, and prove that—

|

"Nothing is, and all things seem

And we the shadows of a dream"— |

and of old, antediluvian dreams. Disdaining this royal road to

critical renown, I commenced by praising the enchanting invocation of the

poet, who when the ladies heard it would leap out of bed and dress.

I observed that to the reader who did not look below the surface—did not

"read between the lines," is the favourite phrase—the poem presented some

mysteries of diction. Instead of appearing as the angel in Leigh

Hunt's "Abou Ben Adhem" did, who diffused himself in the room like a

vision, these peripatetic visitants presented themselves like celestial

postmen "knocking at the door." Then why were they out so early

themselves? Had they more calls to make than they could well

accomplish in the time allowed them? Why were they "in haste"?

No wonder mankind lack repose if angels are in a hurry. The Kingdom

of the Blest is supposed to be the land of rest. Manifestly these

morning angels had to be back by a stipulated time, and like a

tax-collector could make no second call. Apparently Longfellow's

angels are like Mr. Stead's favourite spirit Julia. They are

harassed with appointments, commissions, and cares. It is of no use

being a spirit if you cannot move about with regal leisureliness, such as

was displayed by the first Shah of Persia who visited us. The writer

has seen nothing like it in any European monarch. While in the lines

now in question supernatural misgivings of angelic perturbation are

awakened. But as an example of poetry, irrespective of its meaning

and suggestions, every reader will covet a new edition of the American

poet, and no library could be complete without a copy upon its shelves.

I had visited the poet at his Cambridge home, and was proud

of the opportunity of adding ever so small an addition to the pyramid of

regard raised to his memory.

The editor looked dubious on reading this review, and said

the higher criticism might be entertaining in theology, but the higher

criticism of poetry, which dealt with its meaning, was a different thing

and might not be well taken. In vain I suggested that a poet ought

to mean something, as Byron did, whose fascination is still real, and

there was pathos and beauty, tragedy, tenderness and courtesy enough in

the world to employ more poets than we have on hand. I received no

more commissions in the way of criticisms, and had to think of some other

vocation.

Some of the happiest evenings of younger days were spent in

the rooms of university students. It was pleasant to be near persons

who dwelt in the kingdom of knowledge, who could wander at will on the

mountain tops of science and literature, and have glimpses of unknown

lands of light which I might never see. Who has seen London under

the reign of the sun, after a sullen, fitful season, knows how wondrous is

the transformation. Like the sheen of the gods the glittering rays

descend, dispelling and absorbing the sombre clouds. A radiance

rests on turret and roof. Then hidden creatures that crawl or fly

come forth and put on golden tints. The cheerless poor emerge from

their fireless chambers with the grateful emotions of sun worshippers.

How like is all this to the change which comes over the realm

of ignorance! Light does not change vegetation more than the light

of knowledge changes the realm of the mind. The thirsty crevices of

thought drink in, as it were, the refreshing beams. Once conscious

of the liberty and power which comes of knowing—ignorance itself becomes

eager, impatient—covetous of information. Faculties unsuspected

disclose themselves. Qualities undreamed-of appear. So it came

to be my choice to enter the field of instruction. It seemed to me a

great thing to endow any, however few, in any way, however humble, with

the cheeriness and strength of ideas. True, I began to teach what I

did not know—or knew but partially—yet not without personal advantage,

since no one knows anything well until he has tried to teach it to

another. The dullest pupil will make his master sensible of defects

in his own explanation. Formerly, the dulness of a learner was

supposed to discover the necessity of a cane, whereas all it proved was

incapacity or unwillingness to take trouble—on the part of the teacher.

The result was that I wrote several elementary books of instruction.

All owed their existence, or whatever success attended them, to the

experience of the class-room.

All things have an end, as many observant people know, and

before long I turned my attention to journalism. I had read

somewhere a saying of Aristotle—"Now I mean to speak conformably to the

truth." That seems every man's duty—if he speaks at all.

Anyhow, Aristotle's words appeared to constitute a good rule for a

journalist. I had never heard or never heeded the injunction of

Byron:—

|

"Let him who speaks beware

Of whom, of what, and when, and where." |

The Aristotelian rule I had adopted soon brought me into

difficulties, probably from want of skill in applying it. It was in

propagandist journalism that I had ventured, which I mention for the

purpose of saying that it is not, as many suppose, a profitable

profession. It is excellent discipline, but it is not thought much

of by your banker. Its securities are never saleable on the Stock

Exchange. Nevertheless, the Press has its undying attraction.

It is the fame-maker. Without it noble words, as well as noble

deeds, would die. Day by day there descend from the Press ideas in

fertilising showers, falling on the parched and arid plains of life, which

in due season become verdant and variegated. Difficulties try men's

souls, but true ideas expand them. And they have done so.

Literature is a much brighter thing than it was when I first began to

meddle or "muddle" in it, as Lord Salisbury would say. Nothing was

thought classical then that was not dull. No definition of

importance was found to be utterly unintelligible until a University man

had explained it. All is different now—let us hope.

Instances of the progress of literary opinion are perhaps

more instructive and better worth remembering. In 1850, when George

Henry Lewes and Thornton Hunt included my name in their published list of

contributors to the Leader, it cost the proprietors, I had reason

to know, £2,000. It set the Rev. Dr. Jelf, of King's College, on

fire, and caused an orthodox spasm of a serious kind in Charles Kingsley

and Professor Maurice, as witness their letters of that day.

One journal projected by me in 1850 is still issued—Public

Opinion. Mr. W. H. Ashurst asked me to devise a paper I thought

the most needed. As Peel had said, "England was governed by

opinion," I suggested that this opinion should be collected. I wrote

the prospectus of the new journal, specifying that each article quoted

should be prefixed by a few words, within brackets, setting forth what

principles, party, or interest it represented—whether English or foreign.

Mr. Ashurst put the prospectus into the hands of Robert Buchanan, father

of the late Robert Buchanan, and the earlier issues followed the plan I

had defined. The object was to collect intelligent and responsible

opinion.

In 1866 the Contemporary Review announced that it

would "represent the best minds of the time on all contemporary questions,

free from narrowness, bigotry, and sectarianism." It professed "to

represent those who are not afraid of modern thought, in its varied

aspects and demands, and scorn to defend their faith by mere reticence, or

by the artifices commonly acquiesced in." This manifesto of 1866 far

surpassed in liberality any profession then known in the evangelical

world. It was at the time a bold pronouncement. When it is

considered that Samuel Morley was the most influential of the supporters

of the Contemporary, it shows that intellectual Nonconformity was

abreast of the age—as Nonconformity never was before.

In 1877 I was taken by Thomas Woolner, the sculptor, to dine

at Mr. Alfred Tennyson's (Lord Tennyson later). I believe my

invitation was owing to Mrs. Tennyson's desire to make inquiries of me

concerning the advantages of Co-operation in rural districts, in which,

like the Countess of Warwick, she was interested. The Poet Laureate

gave me a glass of sack, the royal beverage of poets, of more exquisite

flavour than I had tasted before. I did not wonder that it was

conducive to noble verse—where the faculty of it was present.

Mr. Knowles, now Sir James, founder of the Nineteenth Century and After,

was of the party, and the new review—then projected—being mentioned, it

came to pass that my name was put down among possible contributors. The

Nineteenth Century proposed to go further, and include a still wider

range of subjects, with free discussion on personal responsibility. Its

prospectus said "it would go on lines absolutely impartial and unsectarian."

The Prefatory Poem, written by Tennyson twenty-seven years ago, which may

not be in the memory of many now, was this:—

|

"Those that of late had fleeted far and fast,

To touch all shores, now leaving to the skill

Of others their old craft, seaworthy still,

Have charter'd this; where, mindful of the past,

Our true co-mates regather round the mast;

Of diverse tongues, but with a common will,

Here in this roaming moor of daffodil

And crocus, to put forth and brave the blast.

For some, descending from the sacred peak

Of hoar, high-templed Faith, have leagued again

Their lot with ours to rove the world about,

And some are wilder comrades, sworn to seek

If any golden harbour be for men

In seas of Death and sunless gulfs of Doubt."

|

Tennyson, with all his genius, never quite emerged from the theologic

caves of the conventicle. The sea of pure reason he took to be "the sea of

Death." Doubt was a "sunless gulf." He did not know that "Doubt" is a

translucent valley, where the light of Truth first reveals the deformities

of error—hidden by theological mists. The line containing the words "wilder comrades" was understood to include me. Out of the "One Hundred

Contributors," whose names were published in the Athenæum

(February 10, 1877), there were only six:—Professor Huxley, Professor

Tyndall, Professor Clifford, George Henry Lewes, myself, and

possibly Frederic Harrison, to whom the phrase could apply. If the

remaining ninety-four had any insurgency of opinion in them, it was not

then apparent to the public, who are prone to prefer a vacuum to an

insurgent idea. New ideas of moment have always been on hand in the

Nineteenth if not of the "wilder" kind.

After issuing fifty volumes of the Nineteenth Century Review, the

editor published a list of all his contributors, with the titles of the

articles written by them, introduced by these brief but memorable words:—

"More than a quarter of a century's experience has sufficiently tested the

practical efficacy of the principle upon which the Nineteenth Century was

founded, of free public discussion by writers invariably signing their

own names.

"The success which has attended and continues to attend the faithful

adherence to this principle, proves that it is not only right but

acceptable, and warrants the hope that it may extend its influence over

periodical literature, until unsigned contributions become quite

exceptional.

"No man can make an anonymous speech with his tongue, and no brave man

should desire to make one with his pen, but, having the courage of his

opinions, should be ready to face personally all

the consequences of all his utterances. Anonymous letters are everywhere

justly discredited in private life, and the tone of public life would be

raised in proportion to the disappearance of their equivalent—anonymous

articles—from public controversy."

Than the foregoing, I know of no more admirable argument against anonymity

in literature. There is nothing more unfair in controversy than permiting

writers, wearing a mask, to attack or make replies to those who give their

names—being thereby enabled to be accusative or imputative without

responsibility. There is, of course another side to this question. Persons

of superior and relevant information, unwilling to appear personally, are

thereby excluded from a hearing—which is so far a public loss.

But this evil is small compared with the vividness and care which would be

exercised if every writer felt that his reputation went with the work

which bore his name. Besides, how much slovenly thinking, which is

slovenly expressed—vexing the public ear and depraving the taste and

understanding of the reader—would never appear if the writer had to

append his signature to his production? Of course, there is good writing

done anonymously, but power and originality, if present, are never

rewarded, by fame, and no one knows who to thank for the light and

pleasure nameless writers have given. The example of the Nineteenth

Century and After is a public advantage.

CHAPTER V.

GEORGE ELIOT AND GEORGE HENRY LEWES

|

|

|

George Henry Lewes

(1817-78) |

MORE than acquaintanceship, I had affectionate

regard for George Henry Lewes and George Eliot. Lewes included me in the

public list of writers and contributors to the Leader—the first

recognition of the kind I received, and being accorded when I had only an

outcast name, both in law and literature, I have never ceased to prize it.

George Eliot's friendship, on other grounds I have had reason to value,

and when I found a vacant place at the head of their graves which lie side

by side, I bought it, that my ashes should repose there, should I die in

England.

On occasions which arose, I had vindicated both, as I knew well the

personal circumstances of their lives. When in America I found statements

made concerning them which no editor of honour should have published

without knowledge of the facts upon which they purported to be founded,

nor should he have given publicity to dishonouring statements without the

signature of a known and responsible person. On the first opportunity I

spoke with Lewes's eldest son, and asked authority to contradict them. He

thought the calumnies beneath contempt, that they sprang up in theological

soil and that they would wither of themselves, if not fertilised by

disturbance. I know of no instance of purity and generosity greater than

that displayed by George Eliot in her relation with Mr. Lewes. Edgar Allan

Poe was subject to graver defamation, widely believed for years, which was

afterwards shown to be entirely devoid of truth. George Eliot's personal

reputation will hereafter be seen to be just and luminous.

|

|

|

George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans)

(1819-80) |

For myself, I never could see what conventional opinion had to do with a

personal union founded in affection, by which nobody was wronged, nobody

distressed, and in which protection was accorded and generous provision

made for the present and future interest of every one concerned. Conventional opinion, not even in its ethical aspects, could establish

higher relations than existed in their case. There are thousands of

marriages tolerated conventionally and ecclesiastically approved, in every

way less estimable and less honourable than the distinguished union, upon

which society without justification affected to frown.

Interest in social and political liberty was an abiding feature in George

Eliot's mind. When Garibaldi was at the Crystal Palace, she asked me to

sit by her and elucidate incidents which arose.

On the publication of my first volume of the History of

Co-operation, I received the following letter from Mr. Lewes:—

THE ELMS, RICKMANSWORTH,

"Aug. 15, 1875,

"MY DEAR HOLYOAKE,—Mrs. Lewes wishes me to thank you for sending her

your book, which she is reading aloud to me every evening, much to our

pleasure and profit. The light firm touch and quiet epigram would make the

dullest subject readable; and this subject is not dull. We only regret

that you did not enter more fully into working details. Perhaps they will

come in the next volume.

"Ever yours truly,

"G. H. LEWES."

The second volume of the work mentioned supplied to her the details she

wished.

In 1877 I visited New Lanark and saw the stately rooms built by Robert

Owen, of which I sent an account to the Times. The most complete

appliances of instruction known in Europe down to 1820 are all there, as

in Mr. Owen's days. A description of them may be read in the second volume

of the "History of Co-operation" referred to. When George Eliot saw the

letter she said, "the thought of the Ruins of Education there described

filled her with sadness." I made an offer to buy the neglected and

decaying relics, which was declined. I wrote to Lord Playfair, whose

influence might procure the purchase. I endeavoured to induce the South

Kensington Museum authorities to secure them for the benefit of

educationists, but they had no funds to use for that purpose.

Some women, not distinguished for personal beauty when young, become

handsome and queenly later in life. This was so with Harriet Martineau. George Eliot did not come up to Herbert Spencer's conception of personal

charm. One day when she was living at Godstone, she drove to the station

to meet Mr. Lewes. He and I were travelling together at the time, and he

caused the train to be delayed a few minutes that I might go down into the

valley to meet his wife. I had not seen George Eliot for some years, and

was astonished at the stately grace she had acquired.

One who knew how to state a principle describes the characteristic

conviction of George Eliot, from which she never departed, and which had

abiding interest for me.

"She held as a solemn conviction—the result of a lifetime of

observation—that in proportion as the thoughts of men and women are

removed from the earth on which they live, are diverted from their own

mutual relations and responsibilities, of which they alone know anything,