|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER IV.

PROPAGANDIST USES OF INTERVIEWING.

IF electricity be the source of life, the press of

America may be compared to a vast machine for the production of

intellectual electricity, which vibrates through the nation, quickening

the life of the people. One of its original devices for this purpose

is the invention of interviewing.

American newspapers send very able men to Europe, who report

upon features and politics in society with great fidelity to facts.

To catch the humors of classes, and manner of thought of strange peoples,

is a rare acquirement—more an instinct than an acquisition. It is

one thing to satisfy readers in the country for which you write, who have

no means of testing the accuracy of what is said, it is quite a different

thing to satisfy the people whom you describe. At a time when it was

a matter of political necessity to me to understand the way in which the

"intelligent foreigner" would be impressed by English public affairs, and

the opinions formed by them of the chief acts of English legislation, I

used to find the New York "Tribune" of the first order of service.

The letters sent from London, signed "G. W. S.," though they were not

received from America until twenty days after they were written,

frequently contained an estimate of English political questions quite

fresh and instructive then—as I said elsewhere years ago. A

stranger in a country, who is a competent observer, will see many things

which will not strike an observer at home at all, nor at any time, early

or late. The gods have often been asked, but they never have given

us the gift of seeing ourselves as others see us.

Many persons do not take well to interviewers, who,

certainly, are troublesome persons to one who has no definite notions.

It is not pleasant to be asked what you mean if you do not know yourself.

It is often a very perplexing thing, even for a public speaker, to be

asked what is the purport of what he intends to say. It frequently

transpires that he has not thought of it himself. Indeed, I have

many times heard very popular speeches made, of which nobody knew what

they were about. Sometimes I have heard sermons which left the

congregation in this doubt. As a journalist, I have seen leading

articles in English newspapers which gave the reader a great deal of

trouble to discover their object. Indeed, I will not disclaim having

written such myself. Lord Westbury used to say that many persons

assumed the possession of an endowment which "they are pleased to call

their minds," which is not at all apparent to others. Persons who

have a talent for not knowing what they mean should keep out of the way of

American interviewers.

The interviewer is an inquirer, and he visits you partly from

courtesy, partly for the sake of news. He asks you questions upon

subjects which he thinks may interest the readers of the journal he

represents; he uses his own judgment as to what he will report of what you

say. If he inquires where you are going and what your object may be

in visiting certain places, and reports the particulars, persons likely to

promote your object communicate with you; and people in the towns

mentioned become aware of your visit, and bestow attentions and courtesy

which otherwise could never be rendered. If you have special ideas

you want to propagate the interviewer is your best friend. Your

views are spread all over the country. Sometimes by accident, and

sometimes by intention, he gives a provoking turn to your ideas; the

object is that you should write to his paper and correct them, that is if

he thinks a letter from you would be of interest to his journal. You

then have the opportunity of expressing yourself exactly as you wish to be

understood. An ill-tempered or unskilful writer will charge the

interviewer with unpardonable inaccuracy. It is fairer, as well as

more prudent, to assume that the error arose in your own unskilfulness in

giving impromptu answers to unexpected questions. This is likely to

be the case. If time admits of it, and you can go to the office at

the proper hour, you may revise yourself the proof of what you have said.

A little skill will enable anyone to do this by a change of word here and

there, so as not to cause what printers call "overrunning," which would

delay the office too much at a late hour. If a newspaper is disposed

to regard your views as interesting to the country, it will even permit

you to interview yourself. In that case you ask yourself the

questions you want to answer, and give your own replies; and if you

produce an interrogatory paper which is not absolutely dull, you may have

the pleasure of seeing it inserted.

Interviewers, like reporters, are of two kinds. I remember on

one occasion a Cabinet Minister, who, intending to address his

constituency in the country, was desirous to provide for an accurate

report appearing in the London papers. He inquired whether he had better

take a reporter down. I answered that it all depended upon what kind of

report he wanted to appear of his speech. If he wanted an exact report of

what he said, he must provide a shorthand writer who could follow him word

for word. Such a reporter he might find connected with a good local

journal. But if he wanted an abridgment of his speech, or a condensed

report of it, he must take some one from London—one who could perfectly

understand what he wanted to say and what he ought to say, and who could

present a statement of a speech which would be coherent and effective—a

statement that the speaker might not be ashamed of whether he said it or

not. A verbatim reporter is best if you are perfectly sure of what you

intend to say and perfectly sure of expressing it accurately and without

repetition. A verbatim reporter reports exactly what you say—errors and

all, if there be errors—but as a rule he is utterly incapable of

condensing except by omitting and making connections in his own language,

which would commonly be slipshod, incoherent, feeble; often expressing the

very opposite of what was intended. In condensing, a reporter is thrown

upon his own mind, and if he has no mind the result is commonly

commensurate therewith. An abridged report can only be done by a man of

political discernment, who can catch the style and manner of a speaker,

and reproduce his idiomatic turn of thought. A reporter of this capacity

is seldom retained about a provincial paper, except in the larger towns,

where papers are conducted with metropolitan ability; or where the editor

will undertake to condense the speech for you from a literal report.

Among the interviewers I met in America, some were quite

capable of doing this; but when they were otherwise I seldom knew what to

expect until I read it. Sometimes I read reports of interviews I did not

know again, until I reread the heading and found they related to me. I

expressed myself in a colloquial, spontaneous way, using expressions never

intended to be reproduced—supplying a variety to be selected from, merely

to give the interviewer a complete idea of what I had in my mind; and I

often found that the oddest phrases had alone made an impression upon the

interviewer, who gave the illustrations and left the ideas out. When I

wished to avoid this I had to express myself with deliberate

consideration. Then an interview is quite a useful exercise.

On one occasion, when travelling in Massachusetts, on my way

to Boston, a gentleman who had met me at the Narragansett Hotel, Fall

River, joined the train at a wayside station. Having calculated that I

should be in that train he dropped in quite "promiscuously." In the most

casual manner he found an opportunity of entering into conversation with

me, and incidentally asked me about my early religious life, and then

concerning social and political affairs in which I had been engaged. His

inquiries were in no way obtrusive, nor were they one-sided, as I, glad at

falling in with a communicative passenger, asked many questions myself.

The novelty of Boston city, which I saw that night for the first time,

soon erased all memory of the conversation.

The next morning I read in the Boston "Herald" an article

beginning—"There arrived last night at the Adams House an English

visitor;" and then followed a description of my career and views, and what

the writer was pleased to consider my public services, remarkably well

expressed. The character of the article laid me under obligation to the

writer, who was clearly a master in the art of interviewing. His materials

were retained in a trained memory; he respected what might be counted as

private particulars of an unguarded and friendly conversation, and

presented to the public exactly what a gentleman might relate, and what a

visitor concerned might even find gratification in seeing told.

One example of interviewing may explain its character, uses,

and vicissitudes, than further description. I retain the first paragraph

of the following passage from the New York "Tribune," because it admits

that at least I had paid the country in which I was a stranger the

compliment of endeavoring to understand its public affairs:

"Mr. Holyoake is remarkably well versed

in American politics, and is as ardent a Republican as if he had lived all

his life here, and had taken part in the great struggles against slavery

and rebellion. The Democratic party he likens to the Tory party in

England. It will take England, he says, a generation to make good the

mischief the Tories have done during the seven years they have been in

power, and he predicts a like misfortune if the party of reaction should

be allowed to get possession of this Government. The other day, a recent

convert from Republicanism to Democracy was defending his change by

arguing that the country would never be at peace until the South was fully

reincorporated into the Union, and that that could only be done by giving

it the responsibility of power in the Government. Mr. Holyoake listened

attentively to the argument, and replied: 'That is as if the crew of a

good ship which had made a prosperous voyage and beaten off a gang of

pirates, should say, 'the only way to get on with these fellows is to

invite them on board and ask them to run the vessel.' The first thing the

pirates would de on coming on board would be to cut the throats of the

crew.'

"Mr. Holyoake says Lord Beaconsfield has been filibustering

in a shameful manner in Afghanistan and Africa. 'The average Englishman

was attached to the monarchy,' he said to a Tribune reporter the other

day, while discussing this subject. 'We regarded the crown as a graceful

ornament of the State, occupying the ambition of the aristocracy, and

quite harmless to the liberties of the people.' Now we discover this is

false. 'When the English people killed Charles I. they did not kill the

prerogatives of the crown. They only frightened his successors from using

these prerogatives. Beaconsfield has shown us that treaties can be made,

wars waged, and the country committed to any infamy, without parliament

knowing anything about it. Beaconsfield flattered the Queen with the title

of Empress, jeopardizing the succession of her son. Gladstone served the

crown faithfully, and made it respected. In return the Queen said to

Beaconsfield that Gladstone was neither mentally nor morally fitted to

govern, thus intimating that he was insane and dishonest—he, the truest,

clearest-headed man in all England. If there were no other escape from an

irresponsible government, I would drown the royal family in the Thames,

yet no man has more respect for the Queen than I, and I have a much better

opinion of the Prince of Wales than many have."

One passage in this paragraph was erroneously rendered. As it

includes an unfair charge against Lord Beaconsfield, which I would no more

make abroad than I would at home, I wrote to the editor, saying:

|

|

|

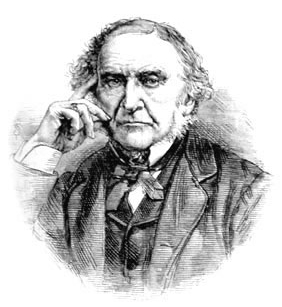

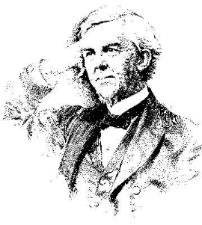

William Ewart Gladstone

(1809-98) |

"Were it customary, I should desire to

express my obligations to the Tribune reporter for the trouble he has

taken to render in your impression of Monday, November 10, the general

purport of the conversations I had the pleasure to have with him. Yet,

either from my habitual rapidity of speech on subjects which interest me,

or from misplacement of some note, an error of statement occurs which it

is my duty to ask your permission to correct.

"It was not her Majesty the Queen who said to Lord

Beaconsfield that 'Mr. Gladstone was not either mentally or morally

fitted to govern.' It was Lord Beaconsfield who said this of the Queen. I

well remember it was not long before his accession to power; and that the

remark was the wonder of the week as to what he could mean by it. It was

the remembrance of this which occasioned so much astonishment among all

classes in England that her Majesty should pay a personal visit to one who

had thus spoken of her. The English people, who have political gratitude,

were jealous that her Majesty should accord a distinction to Lord

Beaconsfield which she was not known to have paid to Mr. Gladstone—a real

friend of the crown, and who had served the nation with splendid

disinterestedness and tireless devotion. Besides, if such a remark as the

one in question had been made by the Queen to Lord Beaconsfield, his

lordship must be inferred to be the reporter of it. That is impossible;

because a minister of the crown in England never reports words of the

Queen without her permission. No one among us can conceive of the Queen as

having made such a remark as that cited, of a minister so eminent as Mr.

Gladstone. Indeed, the delicacy, womanly consideration, and graciousness

of her Majesty's language, in whatever she is known to have said, is

matter of household admiration in England. Indeed, the best Republicans I

know have, as I have, a sort of reverence for the personal character of

the Queen, and at the same time an increasing disbelief in the efficacy or

usefulness of the political functions which the Queen has inherited.

|

|

|

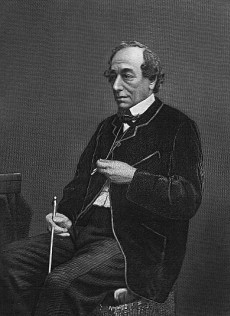

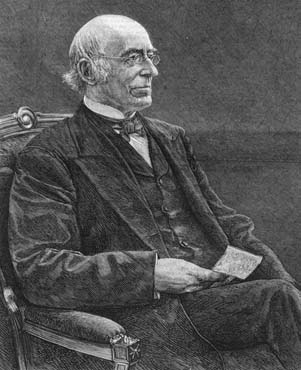

Benjamin Disraeli, Lord Beaconsfield

(1804-81) |

"It is our pride to keep these things quite distinct in

England. Great as is my dislike of the rule of Lord Beaconsfield, greater

is therefore the obligation upon me not to use any phrase which implies

personal injustice to him. Doubtless he believes he is promoting the

rightful interests of England; but my difficulty in perceiving it is, I

believe, incurable."

A change of phrase or mistake in a term may lend an air of

ferocity to your language which was never in your mind. When I wrote the

above letter I had not observed that I was committed to "drowning the

royal family in the Thames." It was the crown and not the "royal family"

which I proposed conditionally to sink in the London Bosphorus. There was

no intention of desire to misrepresent anything I had said, and the

explanation sent was promptly and prominently inserted in the "Tribune,"

in which the interview appeared.

The singular speech about the queen was made by Mr. Disraeli

at a Tory dinner at Aylesbury. The reporters were so astonished at it that

they hesitated to transcribe it, and I have since been informed that one

of them went to Mr. Disraeli and asked permission to read it to him, to be

sure of its correctness. He assented to its accuracy.

This statement of Lord Beaconsfield seemed, when read in

America, quite astounding; and incredulity arose as to whether he really

said it. It was thought that I was under some erroneous impression. When I

returned to England I mentioned it to some "well-informed" politicians,

who did not recollect having heard of it. It was not pleasant to leave it

to be supposed that I had made abroad a statement that could not be

verified at home. As looking up the newspapers of nine years ago involved

some trouble, I mentioned the matter to a "better informed politician,"

who said the fact was recorded in Irving's "Annals of Our Time." Lord

Beaconsfield's speech was made thirteen days before the great fire of

Chicago. To save me trouble my friend looked up the facts and sent me this

information:

|

|

|

Queeen Victoria with Disraeli |

The text of the speech, as reported in

the "Standard" and the "Daily Telegraph" of September 27th, 1871, runs

thus: "The health of the queen has for several years been the subject of

anxiety to those about her. . . . . I do not think we can conceal from

ourselves that a still longer time must elapse before Her Majesty will be

able to resume the performance of those public and active duties which it

was once her pride and pleasure to fulfil..... The fact is that we cannot

conceal from ourselves that Her Majesty is physically and morally

incapacitated from performing those duties."

The "Times" and the "Daily News" omit the words "and

morally." Mr. Joseph Irving, in the Supplement to his "Annals of Our

Time," gives a paragraph that contains the phrase in full.

The "Times" omitted the strange word "morally," probably

doubting that it could be said. The "Daily News" omitted it, probably

believing it would be offensive to the Queen, as well it might be. Not

long since Lord Sherbrooke, then the Rt. Hon. Robert Lowe, M. P., was

required to make a public apology for a mere incidental reference to Her

Majesty—a trifle compared to this outrage by Lord Beaconsfield. Had

language such as he used been spoken by a political leader in America of

the lady who is at the head of the State, our aristocratic journalists

would have written very instructive comments on American political

comments.

In Washington the one inquiry of the interviewer of the

"Daily Post" was, "How long would the Beaconsfield Government last?" They

had learned in Washington

from the English jingo journals that the Tories believed that the nation

was impatient to renew their lease of power. My answer was that the people

did not look upon the Beaconsfield Government as English. The Zulu and

Afghan invasions they regarded as the last wars of the Pentateuch, and

that at the next election Mr. Gladstone would be premier again if he

chose. He was disliked by Tories, and by a minority of Liberals, for his

sincerity—a quality new and unmanageable by politicians—but a great

majority of the people absolutely revered him for that reason. These

remarks were published in the Washington "Daily Post," October 27, 1879,

nearly six months before the fall of Lord Beaconsfield, and when very few

persons believed its end was near.

What is the state of Republican sentiment in England? was

another question of the interviewer. My reply was that we had always been

told that the Premier was virtually King, and that as he was responsible

to Parliament, we had a virtual Republic. But Lord Beaconsfield had

discovered to us that there were sleeping powers of the Crown which might

be ignited like a torpedo and blow up the virtual Republic any

morning—sleeping powers which any traitor or theorist who happened to be

Premier could constitutionally advise the revival of. During his

administration, therefore, he created fifty Republicans from conviction

for one that existed before from sentiment.

Our great political parties in England are as interesting to

an American as theirs are to Englishmen. Being asked for definitions of

political parties in England, my answer was this: The Conservatives keep

from the people all they can; the Liberals give all they think

practicable: the Radicals demand all they think right.

At Kansas City I had to give my opinion of Mr. Parnell, and

Irish Home Rule, and to explain whether I thought him sincere. I answered

that I knew no reason why he should not be, seeing that Home Rule in local

affairs is not an unreasonable demand. The difficulty of giving up Ireland

entirely, was the belief that it would be handed over to the occupation of

the French, as many of the leaders were spiteful to the English; and that

would put England to the trouble of fighting both nations. For a long time

past we had treated the Irish better than they would treat us if we were

in their hands. We had relieved them from an Established Church, and given

them a better land law than we had ourselves. In England, now, we regarded

Ireland as the Land of the Free, and thought of emigrating to it

ourselves, instead of coming to America. Events since prove that Ireland

is entitled to further and substantial improvement in her land laws, and

will get it.

But interviewing did not all turn on politics. Industrial,

and especially co-operative questions were still more frequent. It was in

this way, and by the ability and generous trouble of interviewers, that

the facts concerning co-operation and its progress in England came to be,

for the first time, generally diffused over the United States. I did not

know then what Lord Beaconsfield had written in his "Endymion," or it

would have confirmed all and more than all I ventured to say of the future

of the great movement. I mean where Lord Beaconsfield represents his new

hero, "Endymion," as conversing with one of Mr. Cobden's workmen at his

print works in Manchester, when the workman said that there was something

better than Free Trade, that would one day carry all before it, and that

was "Co-operation." This is a very remarkable statement from so competent

an observer of the advancing forces of society.

The only time when I took advantage of the facilities of

interviewing to say anything personal to myself was when I was asked

concerning the writings of mine on Co-operation. The questions and answers

as they appeared were as follows.

"Is your book on Co-operation to be had

in this country?"

"My first book, called the 'History of the Equitable Pioneers

of Rochdale,' published in 1857, was brought out in this country by the 'Tribune.' I presume it is out of print now. It was said to have caused the

establishment of over two hundred co-operative stores in England within

two years after its appearance. With many other English authors of far

more consequence than myself, I have promoted a law of international

copyright; but I for one have something to say in favor of pirating. My

'History of Co-operation in England from 1812 to 1878' is published by Lippincott. It took me ten years to write it and cost £1,000 ($5,000),

counting what I might have earned otherwise in the time, and the cost for

printing it. I never expect to see my money again. Gain by it never

entered my mind. Now if some enterprising American house will pirate it, I

will gladly relinquish my copyright. Possibly I might gain repute, and

certainly it might do good; for the critics who said it was not

instructive said it was amusing, and those who said it was not amusing

said it was instructive. If any one had written the history of the past

sixty years of the working class after serfdom was abolished and hired

service commenced, how the book would be valued now! My calculation was

that two hundred years hence, when co-operation has superseded hired labor

by self-employment, some one will find my book in the British Museum and

reprint it, as an utterly unknown work. A friendly pirate might cause the

book to be read a little earlier."

If these details have not wearied the reader, before reaching

the end of them, he may see reason to share my opinion as to the

propagandist uses of interviewing, and the generous facilities of

publicity it affords to strangers.

CHAPTER V.

MEN OF ACTION IN BOSTON.

THERE are men of thought and action in most cities.

They abound in New York, in Chicago, in Cincinnati; but it is a different

kind of thought from that which excites the interest of a stranger in

Boston. In Bayard Taylor's translation of "Faust," the lines occur—

|

When the crowd sways, unbelieving,

Show the daring will that warms,

He is crowned with all achieving

Who perceives and then performs. |

But the merit of this discernment altogether depends upon the quality of

the thought which is converted into social force. The people who perceive

what is right and do not do it, are more numerous than is supposed. Next

to the knaves, those philosophers are the most contemptible who, seeing

the errors of the multitude, keep their wisdom to themselves. It is more

respectable to be a fool than to have knowledge and be indifferent to the

duty it imposes of generously diffusing it, and raising the level of

social and public life thereby. The only philosophers worth honoring are

they who, like Petrarch, have a passion "for setting forth the law of

their own minds, and employ their understandings and acquirements in that

mode and direction in which they may most benefit the largest number

possible of their fellow-creatures."

The greatest of modern Italians, Mazzini, had a favorite

phrase, "Thought and Action." In public affairs thought which does

not imply action, or lead to it, or incite it and mean it, is not to be

counted in the forces of opinion. The distinction of Boston is that

its thought seems always meant for political or moral action. It is

this purpose which, more than its general intellectual brightness, has

given this city dignity and influence beyond that of any other in America.

It led the war of independence; it led the war against slavery. Its

philosophers think, and even its minstrels sing, heroic ballads of

improvement. Other cities carry palms of great achievements which

make their names memorable, but Boston is a city of inspiration.

|

|

|

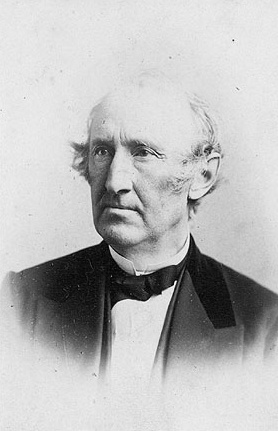

Wendell Phillips

(1811-84) |

If I had a personal object in visiting America, it was

to meet Mr. Wendell Phillips, whose intrepid eloquence, confronting

dangerous majorities, and animating forlorn hopes, has ever been

generously exerted on behalf of the slave, black or white, in bondage to

planter or capitalist. As the only oration he had delivered against

any one, out of his own land, was a reply to certain "Ion" letters of

mine, in 1854, on "Methods of Anti-slavery Advocacy," I presented myself

at his door, as his ancient and alien adversary; and the historic sights

of Boston were made more memorable in my eyes, because they were shown me

by him. Men who had heard Mr. Phillips and the most famous orators

of Europe, regarded him as excelling in the mighty career of speech, which

resembles the torrent rather than the volcano, in its inherent impetus and

splendid rush. While I was in Boston, he was engaged by the Church

of the Sacred Heart to deliver an oration on "Daniel O'Connell." I

desired it to be communicated to the authorities concerned, that if they

would arrange a time for the oration when I could be present, I would

become a votary of the Roman Catholic Church. Unfortunately they did

not attach sufficient importance to my adhesion, and it never fell to my

lot to hear him.

In many cities, from English as well as Americans among all

classes, I was told that I "ought not to leave the country without hearing

Phillips." This was never said to me of any other speaker.

Stories I oft heard told of his perils and triumphs on the platform,

exceed anything I know in the annals of oratory. One of his

repartees has lately appeared in English papers. It occurred in

the days when all the churches preached in favor of slavery. One day

a minister met Mr. Phillips, and, thinking to be smart and unpleasant,

said to him, "If your business is to promote the freedom of slaves, why do

you not go South and attend to your business?" May I ask what is

your business?" said Mr. Phillips. "Oh, my business is to preach the

gospel, and save souls from hell." "Then, why do you not go to hell

and attend to your business?" was Mr. Phillips' answer; and the point of

the reply was that it was about as pleasant and quite as safe to go down

South at that time pleading for slaves among planters, as visiting the

Satanic kingdom would be; and the preacher knew it. It may be said

of Wendell Phillips as was said of Luther, "God honored him by making all

the worst men his enemies."

As my business in America was idleness, and the only exercise

I intended to take was sleep—never having had a season of recreation

before—I did not see half the men of mark I might have met in Boston.

|

|

|

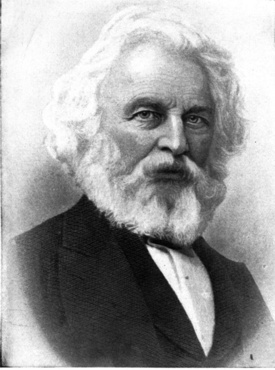

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

(1807-82) |

One morning, after taking me to Bunker's Hill, and

repeating a passage from Webster's splendid oration there when the

monument on it was completed, Mr. Phillips showed me the Auburn Cemetery,

where I was surprised to see the tomb of Spurzheim, he said, "Hard by

lives Mr. Longfellow, in an old English mansion, formerly occupied for a

time by General Washington," and there I had the pleasure to converse for

a short time with the poet, whose works are in many co-operative

libraries, and whose poems of inspiration I had oft heard recited on their

platforms. Longfellow's bearded and august face gives him the

appearance now of a Jupiter of poetry. Mr. Lowell's house lies not far

away among the trees of Cambridge, but he was in Europe then. We are

all glad he is the American Minister in London now.

The diffidence Mr. Phillips reproached me with of not

visiting persons I wished to see without some colorable pretext, was

nearly fatal to my seeing Mr. Emerson. Several mornings Mr. Phillips went

with me to the libraries and book stores, where Mr. Emerson was sure to be

found when he came up to Boston from Concord, but without meeting with

him. One day at the library, Mr. Phillips introduced me to a banker,

saying, "This is my friend, Mr. Holyoake, from London. He has never said

a word about it, but I suspect he is a believer in 'hard money,' which is

the one virtue which you will have to save you." "Yes, I

may escape by that," replied the banker, addressing me; "but your friend,

Mr. Phillips, has so many virtues, which we all recognize, that his future

is secure, despite his one sin of believing in 'paper currency."'

|

|

|

Ralph Waldo Emerson

(1803-82) |

It came to pass that Mr. Stevens, of Cambridge, gave me a letter to Dr.

Allcot, of Concord, asking him to take me to see Mr. Emerson. So, in

company with my friend, Mr. Verity, formerly of Lancashire, I, not knowing

the way, set out to Concord. The way thereto, and the place itself, were

as bright as the historical associations of the town. If ever Concord made

up its mind to be content, it would be in that pleasant spot where water

and wood, spacious plains, quiet villas, and fairy roads abound. Mr.

Emerson's daughter being from home, the philosopher received us himself. Pictures and works of art, which it was good to look upon, were just

numerous enough to be part of the household. Touching, like an enchanter,

a panel, which was not noticeable, it slid away, and we entered the study,

which no one could see without interest. Though tall, Mr. Emerson is still

erect, and has the bright eye and calm grace of manner we knew when he was

in England long years ago. In European eyes, his position among men of

letters in America is as that of Carlyle among English writers; with the

added quality, as I think, of greater braveness of thought and clearness

of sympathy. The impression among many, to whom I spoke in America, I

found to be that while Carlyle inspires you to do something, not clearly

defined, when you have read Emerson you know what you have to do. However,

Mr. Emerson would admit nothing that would challenge the completer merits

of

his illustrious friend at Chelsea. He showed me the later and earlier

portraits of Carlyle which he most cherished; made affectionate inquiries

concerning him personally, and as to whether I knew of anything that had

proceeded from

his pen which he had not in his library. Friends had told me that age

seemed now a little to impair Mr. Emerson's memory, but I found his

recollection of England accurate

and full of detail. A fine portrait of him, which Mr. Wendell Phillips

presented to me, has been generally thought by those who have not seen

Emerson to be a portrait of Mr. Gladstone, whom he certainly very much

resembles

now. Englishmen told me with pride that in the dark days of the war, when

American audiences were indignant at England, Emerson would put in his

lectures some generous passage concerning this country, and raising

himself erect, pronounce it in a defiant tone, as though he threw the

words at his audience. More than any other writer Emerson gives me the

impression of one who sees facts alive and knows their ways and who writes

nothing that is mean or poor.

One morning there appeared in the New York "Tribune" the following

paragraph:

A day or two ago there met in State Street, Boston—on the spot where the

famous massacre took place—Mr. Wendell Phillips, Mr. George Jacob

Holyoake, and the son of Mr, John Bright. Mr. Phillips, who was showing

Mr. Holyoake the historic spots of Boston, had stopped his carriage there,

when Mr. Bright came up with a friend. On being introduced to Mr.

Phillips, a very cordial greeting took

place. "I am very glad to meet you, Mr. Bright," Mr. Phillips said,

"but I would rather meet your father." "My father is better worth

meeting," modestly answered Mr. Bright. "I wish you could persuade your father to visit us," said Mr. Phillips. "I am afraid he does

not like, or fears the sea," was the reply. "We should be content if he

would come and make us just one speech," added Mr. Phillips.

"Ah," said Mr. Bright, "I think my father fears that more." Mr. Bright

is taller than his illustrious father, but has his massiveness and force

of carriage. The expression of his features is that of his mother. In a

speech he made a year ago in his native town, he displayed quite his

father's vigor and fire.

Mr. Phillips asked me afterwards who wrote the paragraph, saying he did

not. Mr. Bright, he said, plainly did

not, nor did his friend. I answered that being a stranger in America, I

could not be expected to be able to throw light

upon the ways of their native journalism so soon. One thing the writer

might have added which struck me at the time; I observed that Mr. Phillips

stood with his hat off

all the time of the conversation. Not Mr. Evarts' message to Mr. Bright

from the American people, gave me a deeper sense of the sincerity of the

regard felt for him, than this fine act of courtesy in a man so eminent as

Mr. Phillips, a man of noble presence and Roman head standing uncovered in

a public square, expressing thereby his respect for young Mr.

Bright, for his own and his father's sake. The man and the act were

national.

|

|

|

The Parker House Hotel, Boston |

Parker House, Boston, which Dickens thought in his day the most

comfortable he found in the States, is frequented by English visitors

still. An improved "elevator" put up here, was talked of when I was in the

city, and I wished to

try it. Luckily I was absent when it was first tested, as it came down

with some adventurous reporters in it, who were battered and bruised as

much as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza were on the night on which they slept

at the inn-keeper's, after the affair with the Yangusians. Had I been in the Parker

House that day, I should certainly have shared in that peremptory descent.

This reminds me that, when at Kansas City, I desired to enter a sugar

bakery there, partly to see if I could learn anything to the advantage of

the co-operative manager of the Crumpsall Works at home, and partly to

escape from the heat of the sun, the ovens of the bakery being cool

compared with the street that day. However, being invited to take a drive

through a suburban road, bearing then, or formerly, the pleasant name of "Murderer's Lane," where, I was assured, some one had been assassinated at

every twenty-five yards, I went, and before I returned next day the sugar

bakery had fallen down, burying five persons, including visitors, in its ruins.

But it is not my intention to relate either curious escapes which occur to

all who travel, nor yet the adventures into which the disability of

blindness inevitably leads. They are not amusing—they are not even

credible to those who see. So little are men sensible of the blessing of

sight—which is a blessing because a protection—that they have an

ignorant, not to say brutal, incredulity of the dangers which pursue the

unseeing. Such a one, crossing a street, flees from a sound of wheels far

off, and runs under noiseless wheels near. I have seen Lord Palmerston, at

seventy-six, cheerily evade the cabs of Palace-yard where a youth with dim

sight had surely been run down. You go in a cab by night—a collision

occurs. He who can see, opens the door and leaps out, and takes another

when the one he was in is

smashed up, while he who cannot see must sit there, since the danger of

moving is the same as that of remaining.

A person with half-sight takes the mist or the shadow in the roadway at

night to be real vehicles, and has to stand still until help comes,

although there is nothing in the way. When living on the Marine Parade at

Brighton, if I returned home after dark I would creep by the houses, or

railings, or walls, until I arrived at the terrace where I dwelt. Only a

narrow roadway lay between me and the door. Listening along the ground to

be sure that no footsteps or wheel was in motion, I would dart across the

road. Immediately a cab was upon me; it seemed as though it started from

the ground. The fact was, the cabmen were lying still, and seeing me

suddenly in the road, moved forward, believing I wanted one. Thus the most

commonplace incident to those who can see, becomes a terror to those who

cannot. When I count my beads I never forget a prayer

for the wise oculist who saves lives by his skill. In America and in

Canada, I had watchful friends near me to whom I owed my safety. Of what

occurred at other times I relate no more, as it could only interest the

few who are exposed

to like peril. Only one thing I shall say, that the blindness has taught

me, as nothing else ever did, how much we are under the dominion of the

senses where we least expect it. To this hour I cannot believe in the dark

that any persons can see me, because I cannot perceive them. Though my

reason tells me the contrary, I cannot shake off the impression.

I know a statesman who incurred years of dislike and contempt from persons

who had served him, and whom he

passed on public occasions as though he disowned them. I

shared the feeling of dislike myself: I, years afterwards, discovered that

he was simply near-sighted, and never saw those whom he was thought to

shun. Alas! what friendships are severed by mere misconception or

ignorance as to the conditions under which others live and move and have

their being. On the other hand, I never felt myself so deep a sense of the

kindness of unknown people in every condition of life as when I found that

I never made an appeal in any land to a gentleman or lady, to crossing

sweeper or cabman, to boy or girl, to thief or harlot, or any one I took

to be a ruffian, to take me across a thoroughfare in the dark who did not

do it in the promptest and kindest manner.

The Mayor of Boston, with what I thought very great courtesy, volunteered

to give me a day to drive me about the city, when I should have seen many

places which I hope at another time to visit; but the men who make the

value of Boston interested me mainly then.

One day Mr. Phillips took me to see General Butler—who appeared to me to

reside everywhere—who had a great deal to tell relating to the industrial

relations of the people. The burly and animated General, of wayward

reputation, took his seat upon a stool in his office, and told me things

of great interest for the space of an hour. On leaving, a friend asked me

"what I said to General Butler." I answered, "You ought to ask me what he

said to me; I never had the opportunity of saying a word." The person to

whom I spoke laughed, as though he thought he ought to have foreseen that.

I had a desire to see Dr. O. Wendell Holmes, who has delighted us so long

in England by his charming stories. Besides being a physician, he is a man

of genius and vivacity. On attaining his seventieth year a dinner of congratulation was given him at Boston. He made his acknowledgments

in a

series of verses, which proved to be a new and graceful version of "Pity

the Sorrows of a Poor Old Man." Of course the verses had touches of

tenderness and fancy, which are never absent from Dr. Holmes' poetry.

|

|

|

Dr. O. Wendell Holmes

(1811-94) |

All

his resources of physiological knowledge, as a physician, were brought

into requisition in describing the tremors, discomforts, and bending

feebleness of threescore years and ten. Admirers of Dr. Holmes in England,

know with what agitation and sympathy they read of what they must have

thought the last appearance in this world of the pathetic and venerable

poet. Being with a friend who met Dr. Holmes in the street, I put an

anxious question to him as to the appearance and condition of that

sorrowful songster, when the welcome assurance was given that he was

perfectly upright, and as lithe and active a gentleman as one would wish

to meet; and there is no doubt that the "Autocrat of the Breakfast Table"

will be found diffusing wisdom and laughter from his morning chair for

many years to come. The doctor's seventieth birthday verses certainly show

that the spirit of poesy is as strong in him as ever, and that the

description of his own feebleness was a part of his art, employed to

heighten the sentiment of his verse, and as a contrast between his burthen

of pitiful words, and his own radiancy of health and song. It is true that

the people of America do not, as a rule, live as long as people in

England,

but that is owing to causes quite within their control. They have pursuits

which interest them more than longevity.

Among the pleasant Sundays in

Boston was one I spent with Colonel T. W. Higginson, who took me to the

house of a lady at Cambridge, where a large number of guests assembled to

hear the hostess read a paper on "An Ancient French Poet." I never

understood till then what I had heard Mr. Moncure Conway say, that Colonel

Higginson, besides being a man of letters, excelled as an interpreter of

an assembly. At intervals, when deference, or delicacy, or inaptness of

thought, caused vacuity in the criticisms of those present, he spoke as

though the occasion was created for him. I thought of what he says of his

hero in his novel

of "Malbone": "Manhood is never commonplace, and he

was a person to whom one could anchor. When he came into the room, you

felt as if a good many people had been added to the company."

|

|

|

William Lloyd Garrison

(1805-79) |

In Boston I met the Hon. Josiah Quincy, whose name we are now familiar

with in England as that of a real advocate of co-operation, and under

whose influence a co-operative store has been established in Boston. While

I was there a statue of his father was erected before the State House in

the city—the Quincys being a family of historic celebrity in those parts. A meeting being held of a great building society on the Philadelphian

plan, which Mr. Quincy had introduced into Boston, he being chairman,

asked me to speak to the assembly on co-operation. It was my first speech

on

the subject in America. The place was the Stacy Hall. The platform was the

one from which Lloyd Garrison had been dragged to be hanged, in the evil

anti-slavery days.

The door is built up now through which he was taken, but I could see it

from the platform where I stood. To save Garrison, the Mayor ordered him

to be taken to jail, and Mr. Quincy, being on the spot in his carriage,

took Garrison into it and conveyed him to prison. Garrison's clothes were

nearly torn from his body, and the rope was put around his neck ready to

hang him. In stature and features Mr. Quincy resembles very much George

Thompson, the English anti-slavery advocate, whom we all knew.

Afterwards, I delivered my first American lecture on co-operation in that

room. Nobody asked me: it was done of my own wilfulness. If the story of

co-operation was to be told in America for the first time by an

Englishman, who was at the beginning of it, I preferred telling it in

Stacy Hall. When I saw some persons present, besides Mr. Quincy, who

presided, I was astonished, and by that time I understood the rage and

enthusiasm of the old slave owners, who climbed up those narrow and

never-ending stairs in search of Mr. Garrison. Had I been he, I should

have thought myself perfectly safe at that inaccessible elevation.

It will be long before I forget the pleasure of meeting Mrs. Theodore

Parker, the wife of the great preacher. I had not before met in America so

bright and gentle a lady. She showed me her husband's study, with

everything as he last sat in it and the last entry he made in his diary in

Florence, where he died. From his writing-room window, in the house where

he lived when he preached his famous sermons, he could see the room where

Lloyd Garrison set up his anti-slavery press. The room where—

|

Unfriended and unseen

Toiled o'er his types a poor unlearned young man;

The place was dark, unfurnitured and mean.

Yet there the freedom of a race began.

|

After Theodore Parker's death his biographer found letters of mine

addressed to him some years before the slave war broke out, in which I had

apologized to him far having objected to the vehemence of his language

against slaveholders, as I knew that he intended war. As Mr. Parker was

not known to entertain at that time the idea of war, his biographer wished

to see what reply he made to me. He

had not written to me that such was his intention. The language he

employed I foresaw must lead to war. I concluded that he intended it, and

on that ground regarded his language as consistent with that end and no

longer to be questioned.

The Rev. Francis Ellingwood Abbott, the editor of the "Index," interested

me greatly. He displayed great capacity, and a Puritan force and pride in

the integrity of the

principles he represented. I know no one in England who has his fine

enthusiasm for liberal and religious progress. As he was the leader in a

contest with great forces opposed to him, I knew, through him, other

persons whose conversation gave me the impression that higher thought and

action are still characteristics of Boston.

In that insurgent city I met the most animated little clergyman I ever

knew, the Rev. Photius Fisk, formerly a chaplain in the American navy, and

a generous friend of slaves, who puts up monuments to those who suffered

for them. One was to Captain Jonathan Walker, of the Branded

Hand. He had helped some slaves to escape. Heavy chains were riveted upon

him, his cell was without bed or table: a slave had cut his throat to

avoid a worse death, and Captain Walker had to sleep on the bloody floor. His sentence was twelve months' imprisonment for each of the seven slaves

he had tried to free. His hands were branded

with a double S, made red hot. One blacksmith refused to make it; another,

who made it, refused his forge to heat it. In Missouri three men were

sentenced to twelve years' imprisonment each for the same offences. Photius Fisk was a brave chaplain, who would bury them when none others

would and put up monuments to their memories. I never knew what paternal

slavery was so vividly as when I heard him describe it. The Rev. Charles

Tory, a Congregational

minister, died in his cell in the same cause. His beautiful

wife prayed that he might be liberated to die. His dead body was sent to

her.

Salem, where they hanged the witches, is not far from Boston, and is the

prettiest town of verdure and water which superstition ever made terrible. Dr. Oliver took me down to see his father, General Oliver, who was Mayor

of Salem, and who showed me the witch houses, in which the rooms are still

unchanged, where the poor creatures were brought in for trial. There is

preserved in Salem the first church built by Puritans. It is a small

wooden structure, which might hold one hundred people. It has a gallery

without any entrance or staircase to it. How the active Puritan Fathers

climbed into it does not appear. The mount where they hanged the poor

witches is being encircled now with streets and houses; but the spot

itself should

be preserved as atonement ground. It is impossible to conceive that any

human being could sleep on that melancholy mound.

General R. K. Oliver was a name I had known in England in connection with

questions of international industry. The social wisdom of his

conversation, now that I had the pleasure to be his guest, impressed me

very distinctly. He explained to me that when he had charge of the Bureau

of Labor of Massachusetts, he counselled workmen to provide themselves

with competence in declining years, defining "competence" as that sum

which, if invested in days of health and work, would procure an income at

a given age, equal to their average income, and sufficient to maintain

them in the station in which they have moved. This is what I mean by wise

talk—conversation which moves steadily to new issues, and in which

material terms are rendered definite. "Competence" is a term on many

tongues. General Oliver was the first person whom I heard define it as he

used it.

Two letters which I addressed to the public papers in Boston I venture to

cite, because the misconception which could arise in so intelligent a city

may arise elsewhere. One was upon the "Rights of Minorities and the

limits of Toleration." It appeared in the Boston "Herald" as follows:

In the report you did me the honor to make of my address at the Parker

Memorial, on Sunday last, occur the words "Lord John Russell has declared

that the minority has no rights." No doubt the fault was my own, not

speaking distinctly at that point. What I intended to convey was a meaning

the very opposite of this. I said we were all grateful to Lord John for

being the first nobleman of

influence to maintain that the minority had rights. Earl Russell well knew

that I was one who did him honor for his action in this matter, and I

would not like that Lady Russell, who takes interest in public affairs as

her illustrious husband did, should read those words and suppose that I

had forgotten the obligations we were all under to Earl Russell in this

matter—obligations which I had personally acknowledged during his

lifetime. I see it stated in your journal that "Mr. Holyoake would have

obscene books treated with contemptuous toleration." On the contrary, I

maintained the right and duty of the State to suppress them, whereas (as

respects books of opinion, occupying the borderland between science and

repulsiveness, which the imbecility of their authors has so confused that

an equal fanaticism grows up to suppress them and maintain them), the Lord

Chief Justice of England lately declared that such publications were best

left alone, as prosecution increased their noisomeness. I defined as

contemptuous toleration, non-interference with these polecat opinions,

which was justifiable only as the lesser of the two evils. For myself I

regard the authors of these questionable books, whatever may be their

intentions, as the traitors of free thought, who obscure what should be

kept jealously clear—the line of demarcation between liberty and license.

The other letter was upon "Useful and Useless Truth." It appeared in the

Boston "Transcript," saying:

In the comment you made upon an expression I am supposed to have used in

my address at the Parker Memorial, on Sunday, you express wonder at its

purport. I do not wonder that you wonder at it. You regard me as saying

that one of the nuisances of the platform was a man who spoke from belief

in the truth of what he was saying. Of course a man ought to have belief

in the truth of what

he says. What I pointed out was that he ought to have more. He ought to

have knowledge of the truth; what he speaks ought to be well ascertained

truth—vital truth—relevant truth. It ought to be as

Grote used to express it—"reasoned truth." There is important

truth and unimportant truth; there is wise truth and silly truth; there is

truth relevant to the question at issue, and a foolish truth relative to

nothing. What I said was, that persons were nuisances of the platform who

did not know this, and who thought that their honest but crude impression

of truth was a sufficient justification of public speech.

CHAPTER VI.

CITY OF HOLYOKE—DISCOURSES.

MY visiting the City of Holyoke was quite

accidental. I was unaware there was a city of that name till I rode

through it on my way to Florence with my friend Mr. Seth Hunt, the

treasurer of the Connecticut City Railroad, whose offices in Springfield

were in the building in which John Brown was in business, some years

before the affair at Harper's Ferry for which he was hanged. Springfield

is as pretty as its name. There was a company in the city which proposed

to supply all the houses with heat—to lay on warm air just as we lay on

gas and water in Great Britain. I sent word to them to come over and warm

England. They would establish depots of warm air in Birmingham, or other

midland towns in our country, and make all our cities comfortable for a

consideration. They have perfected the art of house comfort in America to

a degree to which we are strangers. They not only warm the railway cars in America, they warm the railway depots. In Philadelphia I found

a great railway hall, where hundreds of people could wait for cars, warm

in every part, even when the great doors were open. At a junction station

in Canada, where I arrived once at midnight, every room I

entered was warm. All about it people could lie down and

sleep in comfort. On returning to England I experienced more discomfort

from cold in a midday journey from Liverpool to London, than I encountered

day or night in the remotest parts I wandered into in America and Canada,

during months of travel.

Holyoke stands on the banks of the Connecticut River. It is a young city,

which grows faster than Jonah's gourd. My invitation to deliver the first

lecture on co-operation in it came from some citizens; but the

arrangements were finally made by countrymen of my own, Mr. Goodenough and

others; but the mayor, who is owner of the theatre, assured me he would

have given it free for the lecture had it not been engaged that night.

The city stands in sight of Mount Holyoke, which overlooks the splendid

and fertile valleys through which the silver snake-like river winds 400

miles. The early Puritans who had the sagacity to settle there, had like

the old monks at home, a fine eye for settlements of profitable beauty. Moses saw not a finer sight from Pisgar, than Elizur Holyoke from the

mount from which he looked.

Being told that probably the town was named after some ancestor of mine I

said if that was so I should be glad to collect the rents, as I had never

been that way before. The variation in our names I said might be accounted

for. The early settler, whose name the mountain and town bear, probably

lost the "a" out of his name in the long voyage over the Atlantic in those

days, or had it shot by the Indians when he arrived. My branch of the

family was plainly Druidical, as the name implies, and as the pedigree

might

show—had it been preserved. The American branch may have been phonetic in

taste, and have eliminated the "a" on principle. Edward, the son of Elizur

Holyoke, became president of the Harvard University. He was born in 1689,

and died in 1769, living eighty years.

His son, Dr. Edward Augustus Holyoke, who was born in 1728, lived until

1829. He began to practice medicine at Salem in 1749, continuing in that

profession more than seventy years. He was an acute and learned physician

and

a good surgeon. He performed a surgical operation at the

age of ninety-two. Even after he had attained his hundredth year, he was

interested in the investigation of medical subjects, and wrote letters

which show that his understanding was still clear and strong. On his

hundredth birthday about fifty of his medical brethren of Boston and Salem

gave him a public dinner, when he appeared at the table with a firm step,

smoked his pipe, and proposed a characteristic toast to the assembly. It

is clear that the climate did not kill these early settlers prematurely in

those days, or it was not so vicious then as it is supposed to be now.

In the old church at the foot of Mount Holyoke one of the regicides of

Charles the First's time was buried. He was sheltered by the clergyman, an

old college friend of his in England. He remained concealed in the

rectory. The country being then held by the English, it was unsafe for him

to go abroad, and his existence was unknown in the village. One day, when

everybody was at church, the old military King-killer, looking out from

his eyrie, espied Indians advancing at some distant point, with a view to

attack the settlement. He seized his sword, ran down, mounted a

horse, rode right away to the church, rushed in, and announced to the

congregation their danger. Worshippers in those days went armed to church. The old hero remounted his horse and marshalled the plan of defence not a

moment too soon, for the Indians were upon them. His white hair and beard

streaming in the wind, he fought in the front. The moment victory was

secured he rode straight away—only the clergyman knew where. As he had

never been seen before, and was never seen afterwards, the honest

worshippers deemed him a prophet sent by the Lord for their deliverance. There are many good miracles of earlier days

not so well attested as this. I relate the tradition as I heard it on the

banks of the Connecticut River.

The first time I spoke to a congregation was at the Free Church, Florence,

Massachusetts. It was delivered in the Cosmian Hall, a pretty name coined

out of the word Cosmos. The student of the order of nature in

England would be called a Cosmist—Cosmian is a much more euphonious derivation. The hall is very large, and the most imposing in the city. It stands on a

plain at the lower

end of Florence. The Cosmian Hall having bells, and the Wesleyan Chapel

not having any, the Cosmian bells ring for the Wesleyan worshippers. I was

asked in the morning to meet the teachers of the Sunday School, and make a

little speech to them. Afterwards I was asked to attend the Sunday Schools

and make another speech to the pupils. This constantly occurred to me in

other churches; the object was to enable the children to hear and see the

stranger who had come amongst them. In the afternoon, I addressed a

congregation in the large and handsome hall devoted to

that purpose. At night, I met for the fourth time an assembly which was

considered a reception, in one of the rooms of the hall where, for two

hours, we talked over the practical and ethical side of co-operation,

about which many intelligent inquiries were made.

Americans are merciful critics. They judge that a stranger does not know

all at once where he is, in that spacious and unaccustomed country, and

pardon unattached ideas in his speech. My eyes and my mind alike wandered

in my speeches that day. Mr. Charlton had come down more than 1,000 miles

to meet me at Springfield, to hear me lecture, as he said, once again. Notice of his arrival lay at a depot, which was not communicated to me

until I had left for Florence, where, however, he would also come. Every

knock at Mr. Hill's door (the house of my host) I went out to answer; on

every tramcar stopping before it I listened for the creaking of the gate;

every carriage driving to the Cosmian Hall on Sunday reawakened my

expectation; every tall stranger who entered the church while I was

speaking attracted my attention. It was thirty years since we had met, and

I knew not into what form and appearance America had converted my former

Tyneside friend in that time. After arriving at Springfield he was

summoned to a railway convention at Chicago, which I could not know. It

was some weeks later, and hundreds of miles away, before we met. One night

I was feeling my way in alarm amid walls of railway carriages at

Rochester, neither knowing where I was going nor how to return, when a

lofty figure accosted me in tones which I knew again. A confluence of

trains had arrived that hour, and my friend had had my

name proclaimed in each, but as no such creature had ever been heard of in

those parts, no response could be had, until I was discovered in the

railway ravine through which the last passengers must pass.

The verdant gaiety of Florence still lingers in my memory no less than the

hospitality accorded me there. The negligence of scenery in the city

charmed me. In England Nature has its hair in curl papers. In America

its locks wave wild. It was, I believe, in Florence where I first entered

an American school house. It had broad floors and bay windows, from which

the children could see the beauty of the scenery around them. The teachers

to whom I spoke expressed astonishment at hearing that in England we built

dead walls round our gardens lest the passers by should see the verdure,

and built them round even little children's schools lest they should see

from their playground a flower-girl pass, or a green thing on a market

gardener's barrow.

I visited Mr. Seth Hunt at his house, where he entertained George Thompson

under shadow of the Holyoke Mountains, in the evil days of the

anti-slavery cause when his life was in peril. It was not far from Mr.

Hunt's house to where the Rev. Jonathan Edwards dwelt. In a spot of

wondrous calmness and beauty in those days, with wood, river, and mountain

before him, he fabricated the iron-bound doctrines which have cast a halo

of horror round his name, and makes the stranger tread the streets for the

first time with terror.

The Rev. Mr. Haynes of Providence invited me to speak in his church. My

subject there was "Unregarded Aspects

of Human Nature." In the evening there met at the house of Mr. Frost, a

member of the church, whose guest I was, a considerable number of the

congregation, to whom I was requested to explain the character and

proceedings of our co-operative societies.

|

|

|

Memorial Hall, Boston |

In America, they seem to number the churches as they do the streets. The

Memorial Hall, in Boston, where I spoke twice, bore the name of the 28th

or 38th Congregational Church. Some Churches are called Free Churches, to

denote, as I understood, that in America, even Churches, free nowhere

else, may be free there. In Florence, in Boston, in Providence, in

Chicago, in Cincinnati, the piety of the worshippers, was simple, manly,

and fearless. They did not, as we do in England, pay any attention to what

people thought of them. There was a sense of reverence,

truth, conscience, and duty. They thought that saints were more wholesome

when clean, more acceptable to Heaven when intelligent, more happy for

being free, and their hopes hereafter were strong in proportion to their

efforts to promote human welfare here. In no instance was I asked what

I should say. At no time was any condition suggested even

as to the form of service I should adopt. They did me the honor to believe

that it was impossible that I could abuse their trust by speaking on

controversial points, while the whole field of secular morality lay before

me, upon which, if any new light can be thrown, it is the interest of

every

Church to know it. The singular thing was, that believing that

co-operation had some moral and therefore religious element in it, they

were wishful to hear of that.

[Next Page] |