|

CHAPTER VII.

WANDERING IN FIVE GREAT CITIES.

|

|

|

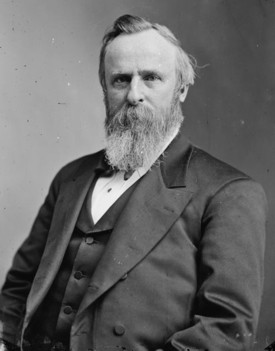

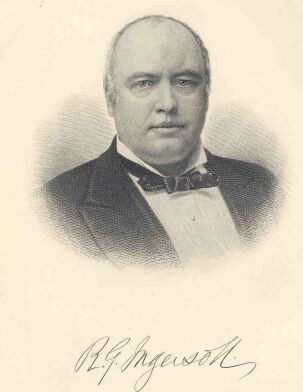

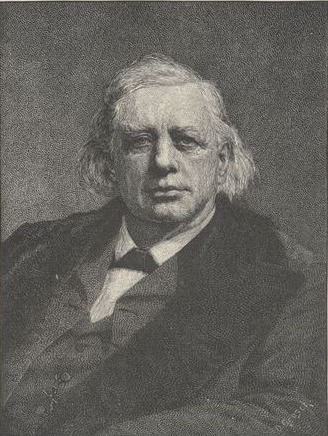

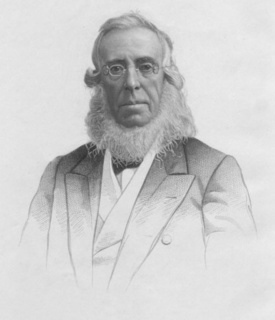

Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll

(1833-99) |

AWAKENING

one night in a railway car, and looking through my bed window and thinking

the scenery rather stationary, I learned that we were on the Alleghany

Mountains, and that the train had got off the track. As I promised

at home not to take this route, I betook myself to sleep again, not

wishing to be killed awake in violation of my compact. The next

evening, while gazing at Harper's Ferry in the moonlight, which had great

interest for me, I heard my name called out in the car, which—since I had

seen no one for nearly two days that I knew—surprised me. It was a

telegram from Colonel Ingersoll, apprising me I should be five hours late

at Washington, and that on arriving there I should find his carriage and

two colored servants at the station, who would wait until I came, and take

me to his house in Lafayette Square. How he should find out where I

was, and how late I should be, which I did not know myself, excited my

curiosity as much as this thoughtfulness gave me pleasure. He had

sent me a letter telling me I was not to leave America until I had seen

some of the famous politicians of Washington, and that if I would come and

stay with him, he and Mrs. Ingersoll would make me "real happy," all of

which came true. It was midnight when I reached Washington, where I

found the carriage and the pleasant Ethiopian attendants of whom I had

received information five hours before.

That was a pleasant day when I went down the sleepy Potomac

to visit Mount Vernon, the former home of General Washington. On the

one end is dreamy, quiet Maryland; on the other lies the rival coast of

bright Virginia. Mount Vernon was utterly unlike what I expected.

Near the entrance of the Washington Estate is the tomb of the great,

crownless king. Beyond, is a modest, picturesque country house, with

various quaint structures, built of English brick, standing on an elevated

plateau, commanding many views of the winding Potomac and open views of

country. The cosy, pleasant rooms where the General lived, the

chamber where he died, the chamber where General Lafayette slept, remained

as they were in their days. In one of the kitchens where the repasts

were cooked for the General's guests he used to give a dinner to his

slaves on Christmas Day, and their feasting lasted as long into the night

as their log fire took to burn out. The artful slaves had an

ingenious device for prolonging the time of their entertainment.

They provided a solid chunk of wood for the Christmas log, and put it to

soak in water a week or two before the festive day, so that it took

unknown hours to burn out, during which time they were their own masters.

No doubt they kept it pretty damp when it gave signs of burning out too

soon. At the death of the General, Mrs. Washington went into the

uppermost rooms of the house, and there she lived until her death.

There is still the aperture in the lower part of the door which she had

cut for her favorite cats to pass through. The custodian, who showed

us the rooms, said he was sorry he could not show us the cats. The

pleasantry was not said for the first time; but it was said so well, and

so freshly spoken, as were all the descriptions he gave us, that they

seemed made new for the occasion.

A light, well-built gateway, through which Washington used to

drive as he entered his farm, needed some years ago to be replaced, and a

few boys in Wisconsin collected money for the purpose, and brought it all

the way themselves. One, of them, I remember, was named Merrill.

They exhibited the greatest delight on beholding the new gateway, when

erected. Their names ought to be written on the lintel in honor of

their bright and auspicious enthusiasm.

Lineal Americans are mostly as quick as four-eyed people, and

seem to see at the back of their heads. We are apt to think ourselves

railroad driven, they regard us as very deliberate in business; but their

activity, like their morals and religions, is a good deal geographical. Washington seems to be a lotus land. I went into one of the coiffeur rooms

of an hotel to have my hair cut. It was growing long, and I was afraid of

being mistaken for a poet, which, unless you happen to be the real thing,

leads to social difficulties at editorial offices which it is always my

custom to frequent. The sun was shining brightly in mid-afternoon when I

entered the hair-dresser's hall. By the time I emerged, the shades of

evening were setting in. Delilah was not half so long, in her wanton

treachery, in cutting off Sampson's locks as York they had cut my head off

in less time. The Washington operator seemed, like Gerard Dhow when he

painted a brush, to work upon a single hair at a time. Now and then he

went away to drink ice water to refresh his minute energies. When at

length I returned home, Mrs. Ingersoll told me that the silk mercers sold

ribbons at the same rate, and that it sometimes required a morning to buy

a yard. All this is very pleasant when you give your mind to it. Washington is the lotus land of business. Shaving certainly is a fine art

in America. I wondered at first how so rapid a people contrived to lie so

still upon the barber's cushion so long a time, in the Northern hotels

where I watched them. The reason I discovered to be that American shaving

is as pleasant as a Turkish bath.

|

|

|

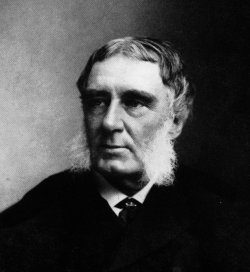

President Rutherford Birchard Hayes

(1822-93) |

I spent time, which seemed far too short, with the Sovereigns

of Industry. At the request of their district council, made at the

suggestion of General Mussey and Major Ford, I spoke one night in a very

handsome hall upon the "English Features of Co-operation," and met many

distinguished persons. My visit to the White House, where I saw the

President, Mrs. Hayes, and General Sherman, I have related in the

"Nineteenth Century." The

Museum of Patents, of Education, and many other places had features of

interest, which I should describe had I found opportunity of making myself

sure concerning them. Washington is full of wonders. General Eaton, who,

if I remember rightly, is at the head of the museum, showed me treasures

of instruction. I thought that if he was at South Kensington he would find

some in the "Nineteenth Century," means of recovering those earlier relics

of educational apparatus which lie at New Lanark. The story of their

condition, George Eliot told me, in the last letter she wrote to me, had

to her mind "a tragic impressiveness."

Mr. George W. Child (everybody in America seems to have three

names; the first and last, as I think I have observed before, are always

put in full; the second is represented by its initial letter only) I saw

but for a short time, and was surprised to find him young and fresh

looking. His chief office in the "Ledger" buildings presented features of

substantial grace and of European art which refreshed the eye to see. What

was to me proof of yet nobler taste was that lofty ceilings, spacious

rooms, light, air, and baths were provided for the work-people; that he

had omitted to reduce the printers' wages when their own union had

sanctioned it. Two weeks' vacation are allowed, and the full wages paid in

advance, and a liberal present of money made besides. On Christmas Day,

also, every man, woman, and boy receives a further present. Our

co-operative stores and manufacturing societies do not do better than

this. This was done by one who, as a Baltimore boy at fourteen, got

himself a place in a book store, beginning life in that self-reliant way. It is rarely that workmen who have become masters themselves treat their

own workmen in the spirit of gentlemen.

When Mr. Child bought the "Ledger" of Philadelphia he

excluded from its columns all reports which could not be read in a family,

or that poison and inflame the passions of young men, and all scandal,

slang, and immoral advertisements. He doubled the price of the paper, and

increased the rates of advertising. The paper was at a low ebb when he

took it; it sank lower now. His friends warned him that this would never

do; that popularity meant sensation; that common people would not buy

common sense, nor would advertisers prefer a journal of good taste. Nevertheless, Mr. Child went on. He engaged good writers, paid good wages,

and made a great paying paper. People in England would not expect this

could be done in America. I know nothing in journalism more honorable than

Mr. Child's sagacity and courage herein, or to the good sense of the

people of Philadelphia who gave their support to this unwonted and

unexpected enterprise.

In that city the co-operators were to make arrangements for

my lecture, but it fell to my unfailing friends, Mr. Worsley and Mr. T.

Stevenson (both formerly of England) to do it. As I wished to go to

Reading, in Pennsylvania, the directors of the railway offered me a

special engine to take me there, and gave me introductions in Reading, to

secure me seeing objects of interest. I said I intended to stay all night,

my object being to be present at one of Col. Ingersoll's lectures before

my return. The answer was: "The engine shall stay for you and bring you

back next day." If I could recall it, I should mention the name of a

Philadelphia gentleman, who, quite unknown to me previously, showed me

costly courtesies, who appeared to know everybody, who introduced me to

the Mayor, and took me to see the famous halls where the historic relics

of American liberty are deposited, and where the Declaration of

Independence was signed. In one of them I saw an oil

painting of Thomas Payne. How it came there, or why it remained there,

nobody knew. It was more intellectual than Romney's portrait of him, which

we cherish in England. It was the only State memorial of the great

Englishman I saw in America.

While at Philadelphia I paid a visit to the Maple Spring

Hotel of Wissahickon, occupied until his death by Joseph Smith, the "sheepmaker,"

described in my "History of Cooperation," and who died a few days after

having had read to him (to his great satisfaction, as I was glad to learn)

my account of his career in England. Mrs. Smith and her family still

occupy the hotel. It was midnight when I entered it. Though anxious to see

his museum it was not until next morning that I cared to do it. The

objects in it were carved by his own hand, out of laurel roots, which

abound on the banks of the sparkling Wissahickon, before which his hotel

stands. In 1839 I saw the Social Hall he built at Salford, which showed

conventional prettiness in the use of colored glass, and I believed Mr.

Smith had no originality, except that of humorous audacity on the

platform.

I expected to find his museum common-place and pretentious. Whereas, I found the various rooms bearing the appearance of a forest of

ingenuity, which a day's study would not exhaust. There was nothing tricky

about it. Its objects were as unexpected as the scenes in the Garden of

Eden must have been to Adam. Noah's ark never contained such creatures. Dore never produced a wandering Jew so weird as the laurel Hebrew who

strode through these mimic woods. Scenes from the Old Testament, groups of

American orators, statesmen, and railway directors started up in the

strange underwood, or held forth in the branches of trees. Dr. Darwin

would require a new theory of evolution to account for the wonderful

creatures-beasts, birds, and insects—which confront you everywhere.

An American Dante, if there be such a one, might find ample

material for a new poem in this wooden inferno. The mind of man never

conceived such grotesque creatures before; yet this was the work of in old

agitator, executed between his seventieth and eightieth year, with no

material but roots of trees, with no instrument but his pocket-knife and a

pot of paint, and no resource but his marvellous imagination. There were

snakes that would fill you with terror; stump orators that would convulse

you with laughter. His Satanic Majesty strode on horseback; Mrs. Beelzebub

is the quaintest old lady conceivable. The foreign devils all had a

special individuality. There was the Mohammedan devil, the Indian devil

practicing the Grecian bend, the Russian devil eating a broiled Turk, the

Irish devil bound for Donnybrook fair, the French devil practicing a

polka, the Dutch devil calling for more beer, the Chinese devil delivering

a Fourth of July oration. I observed no American devil—let us hope they

have not one. Mr. Smith's description of his creations endowed every

creature with living attributes. He illustrated his favorite doctrine of

man being the creature of circumstances, by saying it was coming to live

in the Schuylkill County which first developed in him the latent,

slumbering organ of Rootology. The Wissahickon Museum was the most

original thing I saw in America. I never felt so much the value of a man

of energy, as when I missed his animated face as I entered the spacious

Hall of St. George to speak, and saw it scarcely half full. Had he been

living he would have had it crowded. He had the contagious enthusiasm of a

hundred men in him. It was the Hall of the Sons of St. George, a powerful

association, composed, I understand, wholly or mainly of Englishmen,

having lodges after the manner of the Odd Fellows. Their hall is the

handsomest I spoke in in America. A fine, full-length painting of the

Queen of England hangs in the centre of the platform. Philadelphia is

enviable for many things, and especially for having two mighty rivers

running through it—the Delaware and the Schuylkill. No wonder they

extorted from the Irishman who first saw them the exclamation—"They were

wonderful rivers for so young a country."

An "open letter" was addressed to me in a Philadelphian paper

by Mr. Thomas Stephenson, characterized by those qualities of frankness

and kindness which made interesting his communications to the press in

the old country. It related to topics upon which I was told people in

Philadelphia would like to hear my opinions. In my answer published in

"The Trades," I said "I regarded advocacy as an art by which truth is

presented with clearness and fairness. Conciliation simply means

intellectual justice to those who differ from you, and this should be

observed towards all opponents, whether they observe it towards us or not. As to speaking in Philadelphia, I shall only have time to treat of

co-operation. My rule is always to speak on what I undertake to speak,

and not on any other subject. As to other opinions of mine, I am too

dainty and too proud to indulge any one with a word upon them unless it is

desired to hear them. I am not a hawker of opinions. I regard new truth as

a treasure to be displayed only as a privilege."

When my letter appeared in the journal to which it was

addressed, I was amused to observe that it was two-thirds longer than when

I wrote it. The editor had come to the conclusion that I had made it short

from want of time on my travels, and had kindly enlarged it for me. It no

doubt gave the readers a better idea of my versatility and originality,

for it contained two styles and two kinds of thought, and dealt with

topics of which I had no knowledge.

Cincinnati is certainly an alluring city. Its enterprising

motto is "L'audace toujours l'audace." Let us hope it will have

the audacity to get rid of the smoke, which is accumulating in it. On

looking down upon it from the hills, it reminded me of Sheffield. Away out

of the town there is an elevated cemetery of surpassing beauty, a perfect

park of the dead. My object there was to visit the grave of a young man,

the son of a valued friend of my student days in Birmingham. The youth had

won real friends in Cincinnati, who, together with his comrades, had put

up a handsome memorial of him. A railway line runs through the cemetery.

But so great and umbrageous is the place that the railway scarcely mars

its beauty. My lost friend desired his grave to be within sound of the

passing carriages, which, with a touch of Pagan poetry, he associated with

the return journey home, of which he thought he should be conscious as he

slept. I went also to a grave in Hamilton, Canada, with Mr. Charlton, to

lay flowers on the last resting place of his daughter; and was surprised

to find there also that the grave plot purchased by a family was large,

like the field of Machpelah, purchased by Abraham.

In Cincinnati, I had the pleasure to meet with the family of

my old friend and coadjutor in London, Mr. Robert Leblond. One morning I

went to hear the Rev. Charles W. Wendte, the Unitarian minister, a man of

fine parts and devotional inspiration. It was the harvest festival of the

church. All around the altar was a splendid affluence of the rich fruits

of the season, some of which were given to me. The discourse was upon the

cheerful character of Jewish festivals, which I knew not before were so

alluring. In the afternoon Mr. Wendte occupied the chair at Pike's Opera

House, where I delivered the first address of the season to the Unity

Club, a society which gives ten-cent lectures to the people on Sunday

afternoon. I was given £15 for a discourse of one hour, the largest sum I

ever received for an address. I generally spoke in America for the

pleasure of speaking, but the churches always volunteered me what was

called the "pulpit fee," which varied according to the resources of the

congregation.

The Cincinnati "Commercial," which permitted me to explain in

its columns practical details of co-operation, recorded that I "advised

those who would help in the progress of society, to stand close to truth.

It has been said that truth will take care of itself if let alone. Still,

in view of misadventure, we had better keep near to her."

In Cincinnati, where I was the guest of Mrs. Wilder, I

observed that, in directing me to places I had to visit, she said, "Go

east, go west," from this point or that. I told her that such directions

did not assist me in the least. In Scotland, this peculiar language was

common, but in England it was never heard. "Then, how do you go about,"

she inquired, "if not by the compass?" I replied, England was, as she had

heard, a small country, and we had no room for the points of the compass. "Then, what do you do when you ask your way?" she said. I answered, "We

ask for the place we want to go to." If we asked a policeman in the

streets whether we should turn east or west, he would inquire of his

superintendent if he knew such a place. We ask for Chelsea, or Islington,

or Whitechapel. We have in London an East End and a West End, but they are

names of districts, not of a geographical quarter. We have no North End,

no South End, and nobody conceives that Southwark is in the south. If

Board Schools were to teach such things, we should have Lord Sandon, or

some other Tory, make a motion in Parliament to lower the standard of

education, lest the common people should know too much, and be

discontented with that station to which God had called them. Mrs. Wilder

said, in a kindly and pitying way. "The English are a strange people." Writing to Mrs. Wilder, afterwards, I dated my letter "West of Somewhere,"

saying she would know where I was though I did not.

Good Americans are said to go to Paris when they die; but it

appears to depend upon whether they have been to Chicago first. I like,

the pleasant egotism of its citizens. All towns are not fortunate in their

names. The syllables in New York come together like a nut-cracker, and

Boston is quite a mouthful, almost beyond management; but Chicago is the

most musical, full-spoken name a great city ever bore. A place with such a

name could not be poor or mean.

The Chicago "Tribune" had an amusing paper entitled "A

Bamboozled Reformer," founded upon an interview with me, furnished by its

own reporter. It did not mean that the reporter had set me on wrong

tracks, but that members of the State Socialist party had, who happened

not to have been near me. With the customary fairness of the American

press, the next day the editor printed a letter from me, which he put

under the title "Mr. Holyoake Explains." What I explained was, that while

his observations were clever and just upon what I was reported to have

said, I never said it. By some fault of expression on my part the

interviewer misconceived my meaning.

The fairness and ability with which his report was made left

no doubt that the fault must have been mine. Addressing the editor, I

added: "My impressions agree with yours, that employers in America

recognize in their work-people claims of equality beyond that of any other

country, but upon that I know too little to express an opinion, and

expressed none. What I said was that in England strikes were often

produced by acts of contempt of the claims of men, and prolonged and

embittered by words of outrage which impute dishonoring motives and

intentions to them. I have neither met nor have any knowledge of the

Socialist leaders whom you name. If their objects and methods are such as

you describe, they know well that they are not mine. At the same time, if

their objects are, as I should suppose them to be, to improve the

condition of labor and secure it a fair and permanent proportion of its

fruits, I should approve of those objects. Co-operation, in which I am

interested, seeks the same ends, but by self-help, by reason; not by

violence, but by creating new wealth—not confiscating any which exists,

which would be fatal to the security of the property of workmen when they

acquire it. The policy of co-operation, which has met with the approval of

the great leaders of the two great parties in England—Mr. Gladstone and

Earl Derby—is not likely to be one of confiscation, or unfair or

unfriendly to the rightful interest of employers. You are quite wrong in

thinking that I come here to promote the emigration of the idle to this

country. The idle are they with whom I have no sympathy, and they are

precisely the people who never think of emigrating. While I think there

are better methods open to industry than that of strikes, I pray you to

permit me to state that many of those who have engaged in strikes have

been the most honest and industrious men I have known."

This and other incidental quotations serve to preserve in

these pages a substantial record of what was said on cooperation during

my visit.

In Chicago I had the pleasure of receiving an invitation from

the Rev. Brooke Herford, whose name is widely known and regarded in

Manchester, and whom I found distinguished in Chicago for the usefulness

we have recognized in England. I was surprised to find his church so

large, handsome, and cathedral-like in the interior, without the coldness

of aspect common to cathedrals. The Chicago "Tribune," the day after my

visit, contained the following passage:

The pulpit of the Church of the Messiah (the Rev. Brooke

Herford's church), at the corner of Michigan avenue and Twenty-third

street, was occupied on last evening by Mr. George Jacob Holyoake, of

London, England, who delivered a lecture on "Co-operation." In introducing

him the pastor stated that Mr. Holyoake had been a friend of his of thirty

years' standing. As he (the pastor) had, in the days of their early

acquaintance, been accorded the privilege of preaching from secular

pulpits, so, now, he was glad of the opportunity to have a secular subject

presented by Mr. Holyoake from his pulpit.

Ithaca is not a great city, except in the distinction of

being the seat of the Cornell University, the most perfectly secular

university that I have known. They there teach the arts of usefulness as

well as learning, and rear the students to be citizens as well as

scholars.

Professor White, the President of the Cornell University, was

absent in Europe, he being appointed United States Minister to a foreign

court. The acting president is the Rev. Dr. Russell. His daughter, the

wife of the Rev. Mr. Sharmann of Plymouth (England), had given me a letter

of introduction to her father. The train which brings you to Ithaca

travels round and round a mountain, so that I saw the stars shining over

the valley of Ithaca three times before arriving at the station.

Professor Russell met me, and drove me to the pretty and

learned eminence on which the president's house stands, and around which

the University buildings are spread. After dinner we fell to discoursing

on co-operation, the Professor having long years ago taken an interest in

it. He asked me if I would address the students upon it. It never occurred

to me to speak at the University, and I asked naturally what I could say. "Say what you have been saying to me," was the answer.

Next morning at 10 o'clock a written notice affixed on the

chapel door told the students that Mr. Holyoake would address them there

at 12 o'clock. Including fifty ladies who graduate there, four hundred and

fifty students were present. Every seat was filled as the president

entered, who was received with what resounded against the roof like a

hailstorm of cheers. I never heard anything so distinct and consentaneous

elsewhere. I was about to join in the cheers when I remembered what befell

Mark Twain, when he was one of the guests at a Mansion House dinner in

London, who relates that a gentleman at his side was discoursing to him

on the religious prospects of Great Britain in the future, when he heard a

loud clapping of hands at the name of some guest being announced. The

applause swept Mr. Twain into its vortex and he arose and clapped his

hands. "Who is it I am cheering?" he asked of his friend. "It is

yourself," was the reply. The students were not specially cheering, but

some of their applause was probably intended as an expression of their

hospitality to their visitor.

As my address in the University Church was upon the "Moral

Effects of Co-operation upon Industrial and Commercial Society," from

fifty to sixty members of the Social Science Club met at the president's

house by his invitation in the evening, when, during a conversation of

three hours, the policy and practice of co-operation were discussed.

CHAPTER VIII.

AMERICAN ORATORS.

THERE are many persons who have no very bright idea

of American oratory. The splendid roll of Webster's eloquence is known but

to few. The popular idea of an American orator is of a vivacious speaker

who smells a rat, sees it floating in the air, and nips it in the bud. Yet

there is speaking in America which is not volubilityspeaking which

presents that swift compression of words, that newness and force of

thought, that freshness of facts and display of imminent consequences by a

luminous imagination, compelling the hearer to action—which all men

agree to call oratory.

The public speaker is clear, full, ready, and exact. His

province is to instruct and satisfy the understanding. The orator inspires

the passions. When the speaker ceases the hearer sees what has to be done;

when the orator ceases they do it.

|

|

|

George William Curtis

(1824-92) |

On the day I had the honor of an interview with President

Hayes, at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, the Seventh Regiment held a fair in its

new armory. Speeches were made by Mayor Cooper and George William Curtis. President Hayes was escorted by the regiment from the Fifth Avenue

Hotel to the armory. Mr. Curtis I everywhere heard spoken of as a

politician of principle and integrity. Being unable to accept his

invitation to visit him at his seat, at Ashfield, I have no personal

knowledge of his manner of speaking, save from the few words he spoke at

the Saratoga Convention. The following are the passages from his oration

at the Armory Fair. No volunteer can read it without pride. We have no

such speech made to soldiers in England. There is no "bunkum" in its

chaste and vigorous words. The New York papers reported that Mr. Curtis

was welcomed with great cheering, and his voice rang out clear and strong,

arresting the attention of the crowd that had become restless under its

inability to hear the Mayor. Mr. Curtis said:

"This brilliant presence and the splendid spectacle of

to-day's parade recall another scene. Through the proud music of pealing

bugles and beating drums that filled the air as we came hither, I heard

other drums and other bugles marking another march. Under a waving canopy

of red, white, and blue, through "a tempest of cheers two miles long," as

Theodore Winthrop said, amid fervent prayers, exulting hopes, and

passionate farewells, the Seventh Regiment marched down Broadway, on the

19th of April, eighteen years ago. When you marched, New York went to the

war. Its patriotism, its loyalty, its unquailing heart, its imperial will,

moved in your glittering ranks. As you went you carried the flag of

national union, but when you and your comrades of the army and navy

returned, the stars and stripes shone not only with the greatness of a

nation, but with the glory of its universal liberty.

These are traditions that will long be cherished in this

noble hall. In great and sudden emergencies the State militia is the

nucleus and vanguard of the volunteer army. Properly organized, it

furnishes the trained skill, the military habit and knowledge, without

which patriotic zeal is but wind blowing upon the sails of a ship without

a rudder. No public money is more economically spent, no private aid is

more worthily given, than that for supporting the militia amply,

generously, and in the highest discipline. Other countries maintain

enormous armies by enormous taxation. The citizen suffers that the soldier

may live. Our kinder fate enables us, at an insignificant cost, to provide

in the National Guard not only the material of an army, but a school of

officers to command it. A regiment like the Seventh, and the other

renowned regiments of the city, is not only in its degree the model of an

admirable army, but it is a military normal school. It teaches the

teacher. Six hundred and six members of this regiment received commissions

as officers in the volunteer army; three rose to be major-generals,

nineteen to be brigadiers, twenty-nine to be colonels, and forty-five

lieutenant-colonels.

Mr. Commander, on this happy day every circumstance is

auspicious. The Mayor of the city in which your immediate duties lie,

presides over the vast and brilliant assembly which throngs these

beautiful bazaars. The Chief Magistrate of the Union, who may, in a sudden

danger, call you into the national service, leaving the National Capital,

gladly dignifies the occasion with his presence. Great officers of the

United States and of the State are here to attest their grateful interest

in the prosperity of the New York Militia and National Guard. So should it

be, for in the hands of this gallant regiment the flag of the Union and

the flag of the State are intertwined. Their honor and their glory are

inseparable. The welfare of the States is the happiness of the Union. The

power of the Union is the security of the States. God save the State of

New York! God save the United States of America!

I have twice abridged this speech and twice restored it. I

give it now as it was spoken. Soldiers in England will read it with

interest for its fine animation, and civilians for its instruction as

respects the military policy of a republic. Last year Mr. Curtis made an

oration on unveiling a statue of Robert Burns in the Central Park at New

York. No oration that I read at the time of the Centenary of Burns

equalled this in splendor of expression and discrimination between what

was unwise in the poet's life and imperishable in his genius.

|

|

|

Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll

(1833-99) |

The next example I quote is also inspired by military

memories. The orator is Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll. Some orators have

argument without wit; some have wit without humor; some have humor without

pathos; some have pathos without passion; some have passion without

imagination. Ingersoll has all these qualities. Everybody knows this in

America. Mr. James White, formerly M.P. for Brighton, who traveled in

America when Ingersoll made campaign speeches for Hayes, told me that no

orations at that time had the character and originality of Ingersoll's,

whose late campaign speeches for President Garfield displayed yet greater

qualities. During the nights that we sat up together in Washington,

telling stories of propagandist adventure, I heard the Colonel relate

things which others present had heard before. Yet every one was as much

moved to indignation and laughter as I was, who heard them for the first

time. The following speech was made at the great banquet given to General

Grant in Chicago, on his return from Europe. Sherman and Sheridan also sat

at the table. The speech is in the Colonel's graver mood, the subject

being in memory of the soldiers who fell in the great war for the freedom

of the colored race. Col. Ingersoll said:

When slavery in the savagery of the

lash, and the insanity of secession confronted the civilization of our

country, the question, "Will the great Republic defend itself?" was asked

by every lover of mankind. The soldiers of the Republic were not seekers

for vulgar glory, neither were they animated by the hope of plunder or

love of conquest. They were the defenders of humanity, the destroyers of

prejudice, the breakers of chains, and, in the name of the future, slew

the monster of their time. They blotted out from our statute books the

laws passed by hypocrites at the instigation of robbers, and tore with

brave and indignant hands from the Constitution of the United States, that

infamous clause that made men the catchers of their fellow men. They made

it possible for judges to be just, for statesmen to be humane, and for

politicians to be honest. They broke the shackles from the limbs of

slaves, from the souls of masters, and from the Northern brain. They kept

our country on the map of the world and our flag in Heaven. They rolled

the stone from the sepulchre of progress, and found therein two angels

clad in shining garments—nationality and liberty.

The soldiers were the saviors of the Republic; they were the

liberators of men. In writing the Proclamation of Emancipation, Lincoln,

greatest of our mighty dead, whose memory is as gentle as a summer air

when reapers sing amid gathered sheaves, copied with the pen what the

grand hands of brave comrades had written with their swords. Grander than

the Greek, nobler than the Roman, the soldiers of the Republic, with

patriotism as careless as the air, fought for the rights of others, for

the nobility of labor, and battled that a mother should own her child,

that arrogant idleness might not scar the back of patient toil, and that

our country should not be a many-headed monster, made of warring states,

but a nation, sovereign, grand, and free. Blond was as water, money was as

leaves, and life was only common air, until one flag floated over one

Republic, without a master and without a slave. There is another question

still. Will all the wounds of war be healed? I answer, yes. The Southern

people must submit, not to the dictation of the North, but to a nation's

will and the verdict of mankind. Freedom conquered them, and freedom will

cultivate their fields, will educate their children, will weave robes of

wealth, will execute the laws, and fill their land with happy homes. The

soldiers of the Union saved the South as well as the North. They gave us a

nation. They gave us liberty here, and their grand victories have made

tyranny the world over as insecure as snow upon the lips of volcanos.

And now let us drink to the volunteers, to those who sleep in unknown and

sunken graves, whose names are known only to the hearts they loved and

left—of those who oft in happy dreams can see the footsteps of return. Let us drink to those who died where lifeless famine mocked at want. Let

us drink to the maimed, whose scars give to modesty a tongue. Let us drink

to those who dared and gave to chance the care and keeping of their lives. Let us drink to all the living and to all the dead—to Sherman, and to

Sheridan, and to Grant, the laureled soldiers of this world, and last to

Lincoln, whose life, like a bow of peace, spans and arches all the clouds

of war.

|

|

|

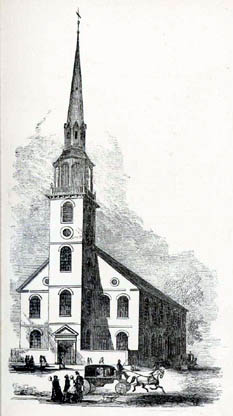

Old South Meeting House, Boston |

Only one volume of the orations of Wendell Phillips has been published. In

1875 he presented to me the last copy which remained. A new edition is now

spoken of, which, if annotated, would certainly greatly interest English

readers. The passages I quote are from subsequent orations, which appeared

in occasional pamphlets at the time. The qualities of Mr. Phillips'

speaking, I have already described. The quality of thought in these

passages is so unlike what Englishmen expect in an American speech, that,

on reading them, I sent copies to a great orator at home, who was not

likely to have seen them. In Washington Street, Boston, stands the Old

South Church, which, in its day, was probably the finest church, or one of

the finest in the United States. The owners proposed to sell it, as its

site had become valuable for commercial purposes. The price they put upon

it was $450,000. Many patriotic ladies in Boston were desirous of saving

it, and Mr. Phillips was asked to deliver orations with a view to obtain

the necessary funds. He made one oration in the State House, with a view

to induce the State to buy it, and another in the church itself, commonly

spoken of as the Old South. The funds came to hand eventually, and the

church was saved. The passage first following is from the speech in the

Old South Meeting House. The statement of the terrors excited by the idea

of universal suffrage, the nature of the courage which took the risk of

it, has never been put so vividly by any other orator. Mr. Phillips said:

I think that the State, on the broadest consideration of

duty, is bound to give its citizens something more than the knowledge of

arithmetic and geography. It does well to supplement the common school and

the university with that monument at Concord. I passed through your hall

as I came up. For what has the State set up the bust of Lincoln there? A

fortnight ago I looked in the face of Sam Adams in the Rotunda at

Washington. What did the State send that statue there for? It was only a

sentiment! For what did she spend ten thousand dollars in setting up a

brand new piece of marble, commemorating the man who spoke those words

under the roof of the Old South? It will take a hundred years to make it

venerable. It will take one hundred years to make that monument on Boston

Common venerable. You have got the hundred years funded in the Old South,

which you cannot duplicate, which you cannot create. A package was found

among the papers of Dean Swift, that old fierce hater, his soul full of

gall, who faced England in her maddest hour, and defeated her with his

pen, charged with a lightning hotter than Junius. Wrapped up amid his

choicest treasures was found a lock of hair. "Only a woman's hair," was

the motto. Deep down in that heart, full of strength, fury, and passion,

there lay this fountain of sentiment; undoubtedly it colored and gave

strength to all that character. When they flung the heart of Wallace ahead

in the battle, and said, "Lead, as you have always done!" what was the

sentiment that made a hundred Scotchmen fall dead over it to protect it

from capture? When Nelson, on the broad sea, a thousand miles off

telegraphed, "England expects every man to do his duty," what made every

sailor a hero? If you had given him a brand new flag of yesterday, would

it have stirred the blood like that which had faced the battle and the

breeze a thousand years? No, indeed! Nothing but a sentiment, but it made

every sailor a Nelson.

They say the Old South is ugly. I should be ashamed to know

whether it is ugly or handsome. Does a man love his mother because she is

handsome? Could any man see that his mother was ugly? Must we remodel Sam

Adams on a Chesterfield pattern? Would you scuttle the "Mayflower," if you

found her Dutch in her build?

But they say the Old South is not the Old South. Dr. Ellis

told us how few of the old bricks remained, which was the original corner,

and which really heard Warren. They say the human body changes in seven

years. Half a million of men gathered in London streets to look at Grant. The hero of Appomattox was not there;

that body had changed twice, it was only the soul. The soul of the Old

South is there, no matter how many or few of the original bricks remain.

It does not change faster than the human body; and yet all the science in

the world could not have prevented London from hurrahing for Grant, or

from being nobler when it had done so. Once in his life the most brutal

had felt the distant and the unseen, and done homage to the ideal.

The next passage is from his oration in the State House, with the object

of inducing the Government of Massachusetts to save the historic old

church. Mr. Phillips reasoned thus:

The times which President Eliot has so

eloquently described were hours of great courage. When Sam Adams and

Warren stood under that old roof, knowing that, with a little town behind

them, and thirteen sparse colonies, they were defying the strongest

Government, and the most obstinate race in Europe, it was a very brave

hour. When they set troops in rank against Great Britain, a few years

later, it was reckless daring. History and poetry have done full justice

to that element in the character of our fathers, nothing more than

justice. We can hardly appreciate the courage with which a man in ordinary

life steps out of the ranks, makes a crisis, while no opinion has yet been

ripened to protect him, not knowing whether the mass will rise to that

level which shall make it safe—make a revolution instead of a mere

revolt. But there was a much bolder element in our fathers' career than

the courage which set an army in the field—than even the courage which

faced arrest and imprisonment, and a trial before a London jury. That, as

I think, was the daring which rested this Government, after the battle was

gained, on the character of the masses—on the suffrage of every

individual man. That was an in finitely higher and serener courage. You

must remember, Mr. Chairman, no State had ever risked it.

There never had been a practical statesman who advised it. No

previous experiment threw any light on that untried and desperate venture. Greece had her republics—they were narrowed to a race, and rested on

slaves. Switzerland had her republics—they were the republics of

families. Holland had her republic—it was a republic of land-owners. Our

fathers were to cut loose from property, from the anchorage of landed

estates; they were to risk what no State had ever risked before, what all

human experience and all statesmanship considered stark madness. Jefferson

and Sam Adams, representing two leading States, may be supposed to have

looked out on their future, and contemplated cutting loose from all that

the world had regarded as safe—property, privileged classes, a muzzled

press. It was a pathless sea. But they had that serene faith in God, that

it was safe to trust a man with the rights He gave him. These forty

millions of people have at last achieved what no race, no nation, no age,

hitherto has succeeded in doing. We have founded a Republic on the

unlimited suffrage of the millions. We have actually worked out the

problem that man, as God created him, may be trusted with self-government. We have shown the world that a Church without a bishop, and a State

without a king is an actual, real, everyday possibility.

A hundred years ago our fathers announced this sublime, and

as it seemed then, foolhardy declaration, that God intended all men to be

free and equal—all men, without restriction, without qualification,

without limit. A hundred years have rolled away since that venturous

declaration, and to-day, with a territory that joins ocean to ocean, with

forty millions of people, with two wars behind her, with the grand

achievement of having grappled with the fearful disease that threatened

her central life, and broken four millions of her fetters, the great

Republic, stronger than ever, launches into the second century of her

existence. The history of the world has no such chapter, in its breadth,

its depth, its significance, or its bearing on future history.

France has proved, and it has been proved in a variety of

cases, that the sort of education that makes a State safe is the

education, the training that results in character. It is the education

that is mixed up with this much abused element which y you call

"sentiment." It is the education that is rooted in emotions, of slow

growth, the result of a variety, an infinite variety of causes; the

influence of books, of example, of a devout love of truth, reverence for

great men, and sympathy for their unselfish lives; the influence of a

living faith, the study of nature, keeping the heart fresh by the sight of

human suffering and efforts to relieve it; surrendering one's self to the

emotions which link us to the past and interest us in the future, and thus

lift us above the narrowness of petty and present cases; using ourselves

to remember that there is something better than gain and more sacred than

life.

Never before was "sentiment," which "practical" men are

accustomed to contemn, so brilliantly vindicated, or its place and

influence on national character so discerningly and vividly described.

CHAPTER IX.

FAMOUS PREACHERS.

THE pulpits in the places of worship I visited were

not like the English preaching barrels, but were rather altars, with space

around them, so that the preacher had full freedom of motion: and like the

Precenter's desk in Scotch churches, the American pulpits are lower than

ours, so that the minister is among the people. Over the reading desk in

Mr. Herford's pulpit, in Chicago, a gas jet is made to burn. The light is

concealed from the spectator so that the countenance of the preacher can

be seen unconfused by a blaze of light. At the same time its strong rays

fall on the pages before him, so that he sees with certainty. This

contrivance, I observed, is a common appendage to an American pulpit,

though unknown in England.

When I was in Hamilton, the first city in Canada you reach

after leaving Niagara, the Mayor had kindly come down to the Grand Hotel

to take me to visit the Fair. As I stepped into his carriage, he said, "That is the Rev. Mr. Beecher sitting in the shade at your door." Thereupon

I said, "I must go and speak to him." In the angle of the portico sat a

gentleman reading a newspaper: he was dressed in black, and wearing a

wide-brimmed white felt hat that served to intercept the stray rays of the

fierce sun on the letterpress. Approaching him I said, "Mr. Beecher,

eighteen years ago you told me that when I was next near to you, I was to

come to you, and not write to you. This is the first time since, that I

have had the opportunity of seeing you—how do you do?" He rose, looked

at me with his dark, bright eyes, and shaking hands with me very cordially

said, "I am delighted to see you—but who are you?" I answered, "Mr.

Holyoake, of London." "Are you," he said, "George Jacob Holyoake?" Upon

answering "yes," I found I had no reason to regret the abruptness with

which I had introduced myself. He desired me, when next I returned to New

York, to let him know my address, as he wished to have a morning

conversation with me. Some weeks later, being again in New York, I sent

him the information, but no reply or visit followed. One Sunday morning I

went over the water to hear him preach in his church at Brooklyn. The

church was very crowded, and when my friend who accompanied me, mentioned

to one of the officers of the church that I was a stranger from London,

and desirous of hearing the famous preacher, a convenient seat was found

or made for me.

While we were singing I looked over the hymn, in which were

the following lines:

|

Let Heaven begin the solemn word,

And send it dreadful down to hell.

|

It was a hymn of Dr. Watts's. If I remember rightly these

were among the lines we sang. I wondered how a man of Mr. Beecher's

cultivated taste could admit lines so painful and discordant to appear in

a hymn book of his church. The solemn words of religion ought not to be

"dreadful," and if they were "dreadful " there must be enough of misery in

hell without sending them there. Mr. Beecher's discourse, like all he

delivers, was very remarkable. With the greater part I could entirely

coincide. It contained a vivid description of the scantiness of the

general records of Christianity so far as it was promulgated by the

scriptural founder. Christ had written nothing himself. Those who

professed to record what he said were themselves mostly illiterate. No

stenography existed in Judea. Though we are told the world would not

contain all the books if his sayings were fully reported, we have but a

comparatively brief record of them; we cannot, therefore, fully judge of

their beauty, completeness, nor variety. Through whose hands the apostolic

records have passed, what changes they sustained, what interpolations they

have suffered, no man can tell. It was impossible not to be impressed in favor of Christianity preached with this manly candor.

The discourse was founded upon a text where Christ takes

leave of his disciples, promising to communicate with them on another

occasion fuller particulars of his mission. His crucifixion following, a

fuller communication was never made. Hence, argued the preacher, we know

not all that really was in the mind of Christ. After mentioning two

cardinal subjects upon which Christ would have undoubtedly spoken, had his

life been prolonged, the preacher came to the third. All along, he had

spoken in an undertone, low and clear, which penetrated to every part of

the chapel, then breaking into his familiar loudness and finished emphasis

of tone, and looking down to where I sat, he said, "The third subject

upon which Christ would have spoken, foreseeing, as he must have done, the

future needs of society—would have been Co-operation." I was startled at

the communication. I had heard that Mr. Beecher had a quick eye to

perceive and identify strangers in his congregation. He certainly could

not have known that I should be there, and if his introduction of

co-operation was a coincidence, it was remarkable, and if designed after

becoming aware of my being there, it was a masterpiece of facility of

resource. What he said was expressed as an inseparable part of narration,

which was delivered throughout with unerring, unhesitating precision. His

language, manner, and action were more finished than when I heard him in

Exeter Hall, in the days of the civil war. His preaching is entirely that

of a gentleman as well as an orator; and from what I read of lectures of

his delivered elsewhere, while I was in the States, I judge that his

reputation depended, not only upon his excellence as a speaker, but upon

the boldness and originality of idea found more or less in every address.

There are other preachers in America who preach with perhaps

equal brilliance, but I heard of no one who speaks so frequently with such

sustained newness of thought. What he said upon co-operation, as a new

element promising to instil more morality into commercial life, showed a

complete comprehension of its character. The sacrament followed the

morning service on that day, and as I could not be a communicant I left,

as my presence there could only have implied a curiosity inconsistent with

the spirit of the ceremony. As a hearer in the church I was, as it were, a

natural guest of the congregation, while only those of a common conviction

could be properly present at a communion service. Otherwise I should have

remained, for the sake of speaking with Mr. Beecher again at the close.

Anyhow, I caused information to reach him that day of the hours I should

be happy to see him at the Hoffmann House, or when I could call upon him

at Brooklyn Heights, if that was more convenient to him, but Mr. Beecher

made no sign.

A few weeks later, being again in Boston, I mentioned to

Wendell Phillips the circumstance. "O," he said, "that is just like

Beecher. A friend of his, who had been to Europe, met with some choice

ecclesiastical engravings, which he believed it would give Mr. Beecher

great pleasure to possess. They were of some value, and after he had had

them mounted he sent them to him. Months elapsed, and he had no

acknowledgment of them. At length he sent a note saying he did not desire

to trouble Mr. Beecher to write a letter to him, but he should be glad of

just a word by which he might know that the parcel had not mis-carried. No

answer arrived. One day, some three months later, the presenter of the

engravings was passing down the Lexington Avenue, at a point where the

streets cross at right angles: a gentleman, rapidly walking, came in

collision with him, and who, prodding him on the breast, said, 'I got your

parcel,' and darted on. It was Mr. Beecher, and that was his

acknowledgment." Mr. Phillips said Mr. Beecher was a busy man, upon whom

so many public and private duties were pressed, that his desire to serve

the many often deprived him of the opportunity, which would be very

pleasant to him, of showing courtesy to individuals. Though we never met

more, Mr. Beecher sent me a very genial letter on my leaving America,

which, being characteristic of the writer, I may cite here:

|

|

|

Henry Ward Beecher

(1813-87) |

BROOKLYN, N.

Y., 124 Columbia Heights.

Dear Sir: I did want to see you,

and set several days to call, but the pressure of home duties obliterated

every arrangement I had made, and you will go home leaving me only two

snatches of a sight of you.

You will leave a good impression behind you. I admire your

prudence and your good spirit, and am deeply interested in the cause that

you have so much at heart. The egg once hatched can never get back to egg

again. The working men of the world can never get back to what are called

the "good old days." They must go forward. In finding the path the

pioneers will make many circuits and track back again a good many times. While my mind naturally has led me to think more of the intellectual and

moral elevation of the common people than of their commercial and

industrial necessities, I have not been unmindful of these other things,

and have rejoiced to see such experiments made as those which you narrate. In every feasible plan for the enlargement of the great under mass of men

I am with you heart and hand.

I hope the sea may deal gently with you. May He "who hath His way in the

whirlwind and in the storm, who sitteth King upon the flood," preserve you

and let you see prosperity for all the rest of your days. Very cordially

yours,

HENRY WARD

BEECHER.

It is clear from this letter that Mr. Beecher remembered seeing me at

Hamilton, Ontario, and in Brooklyn Church. The "prudence" referred to was

merely that of keeping the subject of co-operation clear of other things. This was simply my duty. It is a main condition of advocacy not to let the

subject get confused in the public mind with any other subject. For a new

idea to be distinctly apprehended it must be seen many times, always seen

distinctly, and seen by itself.

A short quotation from an address by Mr. Beecher on the "New Profession,"

meaning that of the teacher, I take from a Montreal report in the "Daily

Witness." It is an example of his oratory on the platform:

Governments abroad were largely engaged

in protecting themselves; the citizen was respected and feared abroad; the

public feeling was that men were chiefly valuable as the stuff with which

to build the State. In America the theory was reversed; here the

individual man was the central figure, the nation his servant. In Europe

the emphasis was put on the Government of a nation; in this country on the

man. The great forces now working in this country were those which tended

to elevate man and make him better and nobler. We were developing the

manhood of intelligence among the people. The emigrants had been eggs in

Europe, they were hatched here. He held that the school was the stomach of

the Republic. The schools of America were that stomach by which all

nations were digested and assimilated into Americans.

Education should be compulsory. The free common schools

should be the best in every community. It was a burning shame when public

schools were not as good as private ones. It was the foundation of the

American idea of the development of manhood that the public school and all

its appendages should be better than can be found anywhere else. Its

architecture ought to be better than that of the church; its rooms ought

to be better than the best in our houses. It was the duty of every

commonwealth to make its school houses gems of art. He believed that

democratic simplicity in this respect was absurd. He had hated the school

house where he had attended, and had never learned anything, and he

abhorred it to this hour. We should not permit the injustice of

instructing children in theologies. It had been said that would be

godless, but it was not so. Was a carpenter's shop godless? The churches

and the households should teach theology. It was not at all the work of

the public schools. It did not follow that we should let the child go

without any religious education. Let us teach him honesty, frugality,

uprightness, and obedience to God and His law. Our schools should have the

full force of professional instruction. They could not do their work while

they were the mere stopping-places for non-professional men and women. In

law and medicine we require experience and professional talent, and it

ought to be the same in teaching. The profession of teaching should rise

in dignity. Its members should have larger pay. Of all parsimony none was

more contemptible than that which asked who was the cheapest teacher.

The Rev. Dr. Robert Collyer, well regarded in England as in America, is of

commanding stature, and has what in an Englishman is always to be

admired—when found—confidence without arrogance. Dr. Bartol, in

describing Dr. Channing, the famous Boston preacher, stated his weight to

be about one hundred pounds. If oratory goes by weight, Dr. Collyer holds

no mean rank. When Dr. Channing, the slender, gave out the line of the

hymn:

Angel, roll that stone away,

the congregation thought they heard it rumbling on its way. If Dr. Collyer

gave out the line they would really have heard it move—there is such

genial authority in his voice. When the deputation from a spacious church

in New York came to Chicago, to invite Dr. Collyer to be their minister,

they had but one misgiving "would his voice fill the place." "If that is

all," said the Doctor, "I shall do, for my voice is cramped in Chicago." His voice would reach across a prairie. If John the Baptist spoke with his

pleasant power, I do not wonder that the desert was crowded with hearers. Strong sense borne on a strong voice is influential speaking. When weighty

sense sets out on a weak voice, it falls to the ground before it reaches

half the hearers. At Dr. Collyer's church, in New York, I met the

Poughkeepsie Seer, Andrew Jackson Davis. I never met a Seer in the flesh,

before, and was surprised to find that he was graceful, pleasant and

human. I congratulated him on the advantage he had over all of us, in

having the secrets of two worlds at his disposal.

The Rev. Robert Collyer was one of the few ministers who felt

that it was his duty to protest against slavery, come what might. He told

the deacons of his congregation of his intent, who prayed him to

reconsider it, as he would "burst up the church." He answered like an

Anglo-American, "Then it has got to burst." He entered his pulpit in

Chicago, and began his protesting sermon. The war was coming then, but had

not broken out. He had not spoken long before he observed a commotion at

the end of the church. The hearers were conversing from pew to pew; the

buzzing voices travelled near to him. He thought the church was about to "burst up" before he had made his protest, when, seeing that he was

ignorant of the cause of the commotion, a hearer leaped up and called out

that the "Southerners had fired upon Fort Sumter." That was the news that

had set the worshippers on fire. All the church leaped up with

inconceivable emotion. "Then," said the brave preacher, "I shall take a

new text —'Let him who has no sword sell his garment and buy one."' Then

all the church went mad—Mr. Collyer said he was as mad as any of

them—and the choir sang "Yankee Doodle." The church witnessed a similar

scene for several Sundays. The churches were freed in a night from the

yoke of slavery, and religion has been sweeter in America ever since. Not

only the almighty dollar was forgotten, but every family in the North, in

the highest class as well as the humblest, gave a father or a son to die

in the noblest war ever waged for freedom.

Englishmen must have an imperishable respect for America,

which made these sacrifices for a generous sentiment. They fought for the

freedom of a race which could not requite them, whom they did not like,

and whose management would bring untold trouble upon them for years to

come. But they would no longer bear the shame of holding human beings in

slavery.

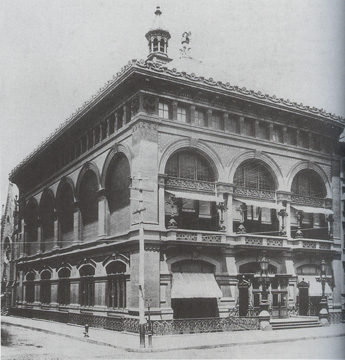

One of the remarkable preachers of New York is the Rev. Dr.

Felix Adler, who was some time professor at Cornell University. His father

was an eminent Rabbi, but his son, Dr. Felix, while retaining all the

passion and fervor of the Jewish faith, no longer insists upon its

ceremonials, but rather upon the moral holiness of life. He is the founder

of a Church of Ethical Culture, which meets in the Chickering Hall, New

York. The congregation includes a large proportion of Jews, and at the

morning service, at which I was present, there were 1,000 to 1,500 persons

assembled. The platform had no assistance from art, which it wanted. But

the preacher soon caused you to forget that. Professor Adler is a slender,

middle-statured gentleman, apparently thirty or thirty-five years of age,

with a glistening eye and sleepy features, denoting rather latent passion

than langor. His voice is pleasant, with a sincere tone. Stepping towards

the front, but not in the centre of the copious stage of Chickering Hall,

without altar, book, or note, he spoke for an hour with eloquence and

enthusiasm, which held everybody in attention.

|

|

|

|

|

Chickering Hall, New York |

I never heard a discourse anywhere like his as to ideas. His argument set

forth that the Church believed in morality, not because God required it,

but because humanity needed it; not because it might be rewarded

hereafter, but because the reward of right-doing was here, and because the

neglect of it followed every man like the shadow of an evil spirit, from

which there was no escape. The love of God and the hope of future life

were graces of conviction. God has not set his bow in the clouds more

palpably than he has set the sign of morality in every house, in every

street. Men may disbelieve the priests, but they cannot disbelieve their

own daily experience. The gods had not left morality dependent upon the

rise and fall of Churches. The philosopher was a greater teacher of

morality than the theologian. Since the death of my friend, the Rev.

Thomas Binney, who taught men "How to make the best of both worlds," I

have heard from no pulpit arguments like those of the Rev. Dr. Adler. The

Church of culture and morality proves itself to be one of charity and

enthusiasm. One of the congregation, Mr. Joseph Seligman, had given

$10,000 for promoting the kinder-garden schools of the Church, which had

great repute.

CHAPTER X.

CO-OPERATION IN THE NEW WORLD.

|

|

|

Robert Collyer

(1823-1912) |

THE

reader has already seen some description of the meeting at Cooper

Institute, New York, which was the most important meeting on co-operation

in which I was concerned. It was there I first met Dr. Robert

Collyer, who presided. The address I delivered was reprinted in many

papers, and in the "Worker," in which it occupied nine columns.

Professor Raymond stated they had commenced the Cooper Union Lectures for

the year, earlier than usual, as I was about to return to England, and

they wished to commence with an address on co-operation. Mr. Thomas

Ainge Devyr, of the "Irish World," who was on the platform, was the first

to advocate in Ireland that doctrine of Land Reform which has since

occupied so much public attention. About 1858, three years before

the slave war broke out in America, he sent me from New York a printed

statement of the causes whose operations would end in war. It

was a perfect political prophecy.

|

|

|

Peter Fennimore Cooper

(1791-1883) |

Mr. Devyr raised some question at the Cooper

Union as to its administration, when Mr. Peter Cooper, the founder, arose,

handed to me his overcoat, and advancing to the front, spoke in a clear,

frank voice, and without digression, vindicating his management by

statistical facts which showed an accurate memory. "We educate," he

said, "2,000 people here, and now I am building a new story for the

purpose of affording education to 1,000 more. But I am glad," he

added, "to hear suggestions which may enable me to make the place more

useful. As I grow older I hope to profit by sound advice (if I get

it). I am only now in my eighty-ninth year." Thus pleasantly

the practical patriarch of New York closed the discussion. He bears

a striking resemblance to Sir Josiah Mason; of Birmingham, who is but five

years his junior, and who has equally distinguished himself by discerning

educational munificence. Mr. Cooper told me that his mother's house

in her earlier years was barricaded against the attack of Indians in New

York, which carries the memory a long way back.

The author of "Our Visit to Hindostan," relates that at Ulwar,

the political agent wished to plant an avenue of trees on either side of

the road in front of the shops, for the purpose of giving shade, and had

decided to put in peepul trees, which are considered sacred by the Hindoos;

but the bunniahs, or native shopkeepers, one and all declared that

if this were done they would not take the shops, and, when pressed for a

reason, replied it was because they could not tell untruths or swear

falsely under their shade, adding, "And how can we carry on business

otherwise?" The force of this argument seems to have been

acknowledged, as the point was yielded, and other trees were planted

instead. This was the moral of my lecture. I contended that

co-operators could permit the peepul to be planted before their stores, as

they could do business under their shade, having no taste and no interest

in telling "untruths," or "swearing falsely" in business.

Co-operative inspiration is that which Wendell Phillips has defined in his

oration on Garrison—it is character. Co-operation is not merely a

search for dollars—it is a search for honesty and equity in trade.

How can a man worship the good God of honesty in his church who has been

cheating all the week over his counter or in his counting-house?

Next I endeavored to make clear the distinction between co-operation and

State Socialism. The adventures which befel me in consequence will

be found in another chapter.

One passage in the interview recorded in the "Tribune" was

the following: "Have you a purchasing agency in New York?" "Yes. The

English co-operators have been doing business in New York for five years.

Mr. Gledhill, the trusted agent of the great Co-operative Wholesale

Society of Manchester, has occupied offices at No. 14 Broadway, since

1874. During the past year we have made £10,000 or $50,000 of profit

upon cheese alone bought in the New York market. I find that since

May last Mr. Gledhill has shipped from this city 60,000 boxes of cheese to

Liverpool for the consumption of the co-operators of England, and, as the

cheese no doubt has a good republican flavor, American principles are

being rapidly assimilated into the British constitution." This was

the first intimation the citizens of New York had of the residence in

their midst of an official representative of the Co-operative Wholesale

Society of Manchester, in England.

The Oneida community no entreaty induced me to go near.

My main reason was that a visit from me would have been in the papers, and

it would have been thought at once that co-operation was some form of

communism. It was my duty to take care that co-operation should be

seen as a distinct thing. The communist may be a co-operator, but

the co-operator may not be a communist. Of all forms of communism in

America, I least liked Oneidaism, with its special sexual theory which

nobody can explain. While I was there, Mr. J. H. Noyes, the leader

of this society, announced what he called a "change of platform." He

had given up, he said, the practice of "complex marriages" in deference to

the public sentiment "evidently rising against it." Public sentiment

always rose against it. He stated that their society would in future

take Paul's platform, which permits marriage, but allows celibacy.

It was stated, privately, that Mr. Noyes's son, who was a physician,

refused to subject his wife to "complex marriage," and that this was the

cause of its abandonment. If the devisor of Oneidaism was convinced

that complex marriage was wrong, it was manly to relinquish it.

Since, however, he admitted that he did not renounce the belief in his

principle, the abandonment of it was therefore indefensible. The

Mormons behaved with more courage and consistency, and refused to follow

Mr. Noyes's example, saying, "Why should we abandon our position unless we

are convinced we are in error?"

Since leaving America I have received many reports of public

meetings, held in New York and elsewhere, to introduce co-operation on the

English plan. There appears no prejudice against any scheme which is

good, whatever country it may originate in. There would be more English

features introduced into both America and Canada than there are, "were it

not," as an intelligent observer told me in Ottawa, "that many Englishmen

come over there filled with bitterness towards their own country, which

tends to discourage the introduction of improvements on the English plan.

Nevertheless, co-operation has certainly won many friends. Articles upon

it, or reports concerning it, continually appear in the American papers. The idea of a Wholesale Agency supplying genuine articles to the stores

seemed to most persons one worth realizing. Mr. A. R. Foote and the Rev.

Dr. Rylance, of New York, have commenced to create a Wholesale Agency

there. Everything in America seems to be adulterated—the certainty that

it will be, if it can be, seems to be taken for granted. If co-operation

takes root and changes this it will amount to the commercial re-education

of the people.

Roughly speaking, no commodity can be trusted. Quinine pills

are not real, candles are short of weight, and silk short of the yard. Indeed, if stores were opened on the English plan—of genuineness of

quantity and quality—they would be distrusted. The public would suspect

any store which proposed to treat them honestly. They would think that

somewhere the snake of interest lay concealed. Yet there is reason to

think that this distrust will be overcome, for there is no difficulty

which discourages an American when he has fairly made up his mind that the

thing he has in hand ought to be "put through." If the people do resolve

upon association they mean it, and one or more of the active associates

bear the name of "organizing members." This term has been introduced into

England now, but in America they have long had the actual person. In New

York the gentleman who is one of the foremost in co-operative advocacy,

Mr. Allan R. Foote, has a genius for organization. He has written and

published a scheme of a wholesale society and of co-operative stores, and

written co-operative pamphlets which are interesting, brief and wise in

expression, as well as business-like. The following are some of the

sentences he prints as mottoes in his small books of "Co-operative Laws":

"1. To grow rich, earn money fairly. 2. Spend less than you

earn. 3. Hold on to the difference. The first requires muscle; the second,

self-denial; the third, brains."

"The competition of the individual system is for every man to see how much

money he can divert into his own pocket from the pockets of those who

labor for him. The only competition possible in commercial co-operation is

to see which store will put and keep the most money into the pockets of

those who support it."

"If any man counsels you that you can gain wealth any other way except by

working and saving, he is your enemy." "If a man owns a sovereign, he is

a sovereign to that extent. If a man owes a sovereign, he is a slave to

that extent."

These are maxims worthy of consideration elsewhere than in

America, and the ideas expressed have never been put better anywhere. "Lectures on Social Questions," including Competition, Communism,

Co-operation, and the Relation of Christianity to Socialism, are a series

of the luminous discourses delivered by the Rev. Dr. J. H. Rylance in St.

Mark's Church, New York, which would be read with great interest in

England.

The custom of a store is called the "patronage" of it. It is