|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER VIII.

A QUEER MAN.

TOM

OLLISON found his two

days’ visit to Stockley Mill all too short for the wonders and

delights of the quiet, deeply stored, old-world life, which seemed

to him rather fresh than new, because he had known it before in

story and poem. He seemed almost to have lived before through that

Christmas morn, when the household from the mill walked over the

snow, gleaming in the sunshine, to the little, ivy-covered church. Surely the rich glow of the old painted windows was not something he

had never seen before! And the voices of the choir and the

school-children singing, “O come, all ye faithful,” came to him like

an echo from a dream. And when the simple service was over, and

after the silent prayer which follows the benediction, as the little

congregation stood up in obeisance to the squire as he passed down

the aisle, Robert Sinclair kept his seat, but Tom Ollison stood up

with the rest, and did not feel the less, but the more of a man for

doing so. For the stately, white-haired old gentleman was clearly “a

father in Israel,” an aristocrat, “one of the best,” as the

dictionaries tell us. And as Tom glanced round the crowd, where the

very poorest looked comfortable and well-cared for, and as he

thought of the scores of happy homes outside, he reflected that much

that he saw must be due to the just and gentle rule of the Manor

House, and that a reverent and kindly courtesy was as due from these

people to this worthy successor of worthy sires as it is from

children to a parent, and that any guest should join in the good

customs of a community, as he would in those of a household.

The squire had nods and smiles for all around, but he also had

friendly words for the aged, the infirm, and the widow, and little

caresses for the widow’s children, which left something solid in the

little hands after he had drawn his own away.

“The worst of it is, that the squire hasn’t a son to come after

him,” Mrs. Black had told Tom, as they walked home. “When he dies

the estate will go to a distant kinsman, whom none of us know. When

the squire was young he fell in love with a poor earl’s daughter,

and she liked him, and her folks were pleased, knowing his family

was older than hers, and thinking that Stockley Hall would be an

honourable, quiet down-sitting for her. But she’d lived on the edge

of the Court, poor thing, and had got a hankering after the

extravagance and gaiety she couldn’t rightly share in, because the

earl was so short o’ money. And there came by a rich iron-master — it

was just when railroads were doing their best or their worst in the

country — who could have bought up Stockley with little more than

one year’s income. And the iron-master fancied her ladyship, and she

threw over the squire, and took him. And the squire never looked at

anybody in that way since. I’ve heard say that some have asked him

whether it wasn’t the duty of one in his place to marry and keep up

the old line; but that he made answer, that was the squire’s duty,

but the man’s duty came first, and that was to marry no woman unless

he loved her.”

“I only wonder he’d ever cared for such as that lady must have

been,” rejoined Tom, the rash and inexperienced. “She must have been

a mean, low-minded sort.”

Mrs. Black gave a superior smile. “Ah! there’s mysteries in falling

in love,” she said. “Them that has done it wisest will always tell

you that it wasn’t of their own guidance. It all comes from above.

‘A prudent wife is from the Lord‘ — his best blessing to a man. But

his next best is to keep away an imprudent one, and that’s what a

vain, foolish woman always is.”

“But this lady seemed to know how to look after money,” said

Tom, “and ‘prudence’ sounds as if it meant that.”

Mrs. Black laughed. “That’s what the parson said one

Sunday,” she replied. “He said exactly that — that people

thought prudence meant looking after money; and that their idea of

looking after money was getting it to spend on one’s self, or to

keep to please one’s self. ‘Whereas,’ said parson, ‘prudence

means providence, or foreseeing, looking after the real things that

we really want — love, and wisdom, and true comfort, and trying to

secure them for as many as we can.’ I’ve always remembered

what parson said about that, because I’d been feeling after it in my

own mind, and it was like suddenly hearing a tune that has been

running in one’s head, but that one couldn’t quite catch.”

“It’s the sight o’ parson and o’ his own ways that’s kept me

in mind o’ those words,” said Mr. Black. “When you’ve got a

pretty picture it’s well to have a sound wall to hang it on.

There’s the parsonage, young gentleman,” and the good miller pointed

to a long, low cottage standing in a bowery garden, not unlike his

own home at the mill. “If you want to know what is in a

shilling, and what can be made to come out of a shilling, don’t go

to the poorest folk i’ Stockley; go there.”

Tom eagerly drank in all the homely wisdom. The good

seed fell on ground prepared for it. Now everybody should be

always prepared to sow, because nobody knows where good ground may

be. Sometimes there are a few inches of it in the midst of a

morass or in the cleft of a rock. But God’s field of the world

needs all sorts of agricultural labour besides sowing. It has

ground which must be broken up by steady discipline, ground which

must be manured by heavy experiences, ground which must be altered

by the bitter chemistry of loss and remorse.

Robert Sinclair walked beside the Blacks, and hearing them

“go off,” as he put it to himself, “into their usual chatter,”

relapsed into a train of thought of his own — a calculation as to

the sum which would be produced by a certain rate of interest on a

certain sum of money in a given term of years.

Let not those who speak wisely lay too much unction to their

souls! If they do see of the fruit of their lips, let them

remember that there must have been as much wisdom in the ears that

heard as in the tongue which uttered. “As an earring of gold,

and an ornament of fine gold, so is a wise reprover upon an obedient

ear.” But if the earring falls into the gutter, it will only

be trodden under foot.

And then the pleasant visit was over. Mrs. Black

herself stepped down to the railway station with Robert Sinclair to

see the young guest away. Stockley people were never afraid of

seeming too civil or too kind. And just at the last minute

Stack the miller’s man appeared, carrying a big hamper to be stowed

under Tom’s seat in the train, Mrs. Black vouchsafing no explanation

except that “nobody should ever come into the country without

carrying a bit of it back to the town.” And Tom was whirled

off, nodding back to her waving handkerchief; and somehow father and

Clegga Farm did not seem quite so far away, now he had made friends

with these kind people nearer at hand.

Very dark and dismal looked the London streets as Tom wended

his way through them towards Penman Row. And yet, so

inscrutable is the human heart, Tom felt that this temporary going

away from it had made the dull old house there seem more homelike.

It had certainly flashed into Tom’s mind, when Robert expressed his

determination to leave the mill, that this might give him a chance

of quitting the gloomy shop and its not very congenial labours, and

of taking Robert’s vacated place. But the thought had only

come to be dismissed. Peter Sandison was his father’s friend,

who had made generous terms with him for his father’s sake.

And Peter Sandison looked at him with sad eyes. And it was

said that Peter Sandison did not believe in God! Strange

reasons these for loyalty and love! But then loyalty and love

so often grow best from no reason — which means generally but reason

too deep for words, or even for defined thought.

Our lives are never fairly poised or truly rich, unless there

is something outside our own orbit which we can love and enjoy

without coveting to possess. What would the earth be without

the sunbeams? But what would happen to the earth if it at once

rushed off to join the sun? Tom felt that Penman Row should be

cheerful enough when one’s work was there, and while one had

memories of Clegga and thoughts of Stockley to carry with one into

it. The gloom and the perpetually shifting crowd of strange

faces had already ceased to oppress the soul of this son of the

rocks and the sea. They began to stimulate his imagination,

suggesting to him that human life could overmatch nature in every

mood and aspect.

Mr. Sandison met Tom with a smile and a kindly word. He

looked happier than he had done on Christmas eve, so that Tom hoped

that he had enjoyed himself after his own fashion. It was not

for the youth to guess or to fathom that the dreariness of his

master’s lonely wandering among the holiday crowds, his aimless

watching of happy groups, had merely ended in a sad thankfulness

that another Christmas of his allotted number had gone by.

Early in his dismal Christmas stroll, Mr. Sandison had come

in front of an open door, over which was painted, “Refuge for

destitute strangers.” Saying to himself that the omission of

the descriptive adjective would have spared paint, politeness, and

pain, he yet went in, half out of curiosity, and half out of a

strange yearning both towards those who needed such help and those

who rendered it. A Christmas breakfast had been given, and

when Mr. Sandison entered between the delivery of little addresses,

ladies and gentlemen were moving to and fro amid the pathetic crowd.

The bookseller quietly ranged himself among the battered women and

broken men, who were accepting precept and exhortation with all the

meekness with which the defeated are expected to take whatever the

victors give. His own shabby, carelessly used coat easily

seemed the threadbare garment of a decent poverty, and there was

scarcely a visage there more rugged and worn than his. A

dressy little woman, wearing more ornaments and falderals about her

than she could have decently sported in a drawing-room, and

flaunting them in the face of those monuments of human misery,

“because the poor don’t like you to come among them shabby, you

know,” fussed up to the new arrival. She had whispered to a

friend that this looked “an interesting case,” one of the sort that

might figure in a paragraph on “university men to be found in the

kitchens of common lodging-houses.” Her little figure stood

beside Mr. Sandison’s gaunt dignity, like a gaily painted shanty

under the grey wall of a noble ruin. She gave a perky little

cough, and opened her mission.

“Is it not very nice for you to have a room like this to come

to?” she said. “Don’t you think it is very kind of all these

dear people to leave their own beautiful homes to come here to

welcome you just like friends? Is it not something to be very

thankful for?”

“Madam,” replied Mr. Sandison with a melancholy humour, “in

my old-fashioned school of manners, the guests gave the hosts

voluntary thanks: the hosts did not suggest them. But it is

some years since I have mingled in any society, and ways seem

changed.”

The lady did not quite understand him. She only knew

that she did not get the gush of gratitude which she expected, and

she was in a measure disconcerted. “I’m afraid you have not

had a very happy life, poor man,” she remarked, and there was at

least as much blame as pity in her tone.

“Madam, I am quite sure of that,” said Mr. Sandison.

“Is not that partly your own fault?” she inquired. “Do

you love God? If you love him you must be happy.”

“I want to find somebody who believes in him,” answered Mr.

Sandison. “How can we love whom we do not know?”

The lady thought she had got into an incident after her own

heart. She fussed all over. She seemed no longer one

woman, but rather twenty crowding round him.

“My dear man,” she cried, “surely you have found what you

seek! We all believe in God here. Is not our love for

our poor and afflicted brothers and sisters the best proof of our

faith?“

Mr. Sandison pointed grimly to the words above the door.

“Is that what you call your brothers and sisters?” he asked.

“How can they be destitute if all your hearts are really full of

love for them? Take out that word — that adjective, which must

be bitterest to bear where it is truest. And what do you know

of me which gives you any right to think that you can exhort me?

I am older than you by many years. You see that I am sad and

careworn; you think me poor. All these points, madam, should

on the face of them rather invite you to ask to learn of me.

You simply feel that you must be wiser than me because you believe

yourself to be more fortunate and richer. Madam, was Jesus

Christ himself fortunate and rich? If you saw him to-day you

would not call him Master, you would call him a destitute stranger,

and ask him to thank you for amusing yourself with feeding him and

preaching to him.”

The lady shrank back. Her small face grew pale.

As Peter Sandison turned: and strode from the room, she whispered,

“One of those dreadful socialists, I do believe. You cannot

think what awful things he said! He spoke quite coarsely.

The more we do for these people, the more they hate us. The

world is growing very wicked.”

But when, after all was over, a paper was found in the plate

in the lobby, on which was written, “To be used for the refuge of my

brothers and sisters whose names I do not know,” and in which were

folded two sovereigns, then the lady remembered that a certain

radical and “peculiar” viscount was addicted to frequenting such

assemblies in disguise. “Dear man,” she sighed, “he would be

such a gain if we could bring him round altogether to our side — to

the right side. He spoke so cleverly. I saw at once that

there was something most remarkable about him. Those people

cannot disguise themselves, do what they may. A practised eye

sees a subtle something!”

What would she have done had she known that this was no

viscount, no out-at-elbows university man, not even an interesting

and picturesque criminal, but just plain Peter Sandison, bookseller,

of Penman Row!

Later on, during Christmas Day, he had strayed into a church,

and had sat down in a corner where the dust was thick upon the

cushions, and damp and mildew had seized on the prayer-books with

names of dead people, and dates of forgotten anniversaries on their

discoloured fly-leaves. Peter Sandison had smiled a weird

smile when the preacher, a mild young man newly ordained, after

dwelling on the blessings given to most at this season richly to

enjoy, had gone on to speak of “resignation,” and to suggest cheer

for those whose joys were of the things gone past: “Let them still

thank God for those joys,” he had said; “let them be content to wait

without them for a while, measuring by their sweetest memory the

joys which hope has in store.” And Mr. Sandison had wandered

out again — there had been no word for him. He did not know

that he had been disappointed: he would have denied that he expected

anything.

When Tom came back from Stockley he carried his hamper into

the parlour, and asked Grace’s aid in unfastening it. The

master seemed to suspect what was going forward, for he came in too.

“Won’t you invite me to see your gifts, Ollison?” he said.

“I didn’t think of troubling you, sir,” Tom answered

delighted.

“What’s the good of stuffing a basket with rubbish like

this?” observed Grace, lifting out first some small holly boughs,

rich with berries. But Mr. Sandison lifted them tenderly, as

if he wouldn’t knock off a berry for the world, and — smelled them.

“La! don’t you know they haven’t no scent?“ snapped Grace.

“They have a country freshness,” said Mr. Sandison gravely,

knowing that only Tom would hear his words.

“That’s more like the thing,” Grace went on, lifting out a

plump pullet. “And here’s eggs; and here’s apples; and here’s

a pot of jelly. These folks are a-making up to you for

something, Master Tom.”

“They are such good people,” remarked Tom to his master,

unheeding the old woman’s words, “and Stockley is such a pretty

place — oh! beautiful, one can scarcely believe in it.”

“Don’t you wish that you and your Shetland comrade could

exchange?” asked Mr. Sandison coolly.

“No,” said Tom, as honestly as stoutly, “I like sticking to

my own lot.”

“But if Stockley had been your lot you wouldn’t have wished

to exchange it,” persisted the bookseller.

“No, sir, I shouldn’t,” Tom answered, “and I’d have stayed at

Clegga if I could —but I half think I’m glad I couldn’t; I’d never

have known the best of Clegga if I hadn’t come away.”

Mr. Sandison laughed, and then sighed. Grace came back

from storing the good things in her pantry. She now carried a

parcel in her hand, and as she came in, Mr. Sandison rose and went

out of the parlour into the shop.

I’m going to show you the grand present I got this time,”

said the old woman. “It came just as you went away.” She

spread out a thick grey shawl, fine in texture, and delicate in hue.

“You see there’s somebody feels I’m worthy a good present,” she went

on, “though I believe the master thinks they must be fools for their

pains, for he’ll hardly throw a look at it. But it’s odd how

everything gets taken advantage of, and put to bad purposes in this

world. Of course it has got talked about, how I’ve had these

beautiful things sent to me by somebody unbeknown. Indeed,

I’ve told many of the young hussies round that it was a good lesson

to them, that if they did their duty it would get recognized

somehow. An’ now them worthless Shands, in Penman Court, are

making believe that the like has happened to them! Set them

up! I can see through it!”

Grace was folding up her shawl with elaborate care while she

talked.

“They just wanted some Christmas feasting,” she proceeded.

“And what with their perpetual poor mouth about misfortunes, and

their debts, and so forth, they thought it would not do to get some

above board. Indeed, I don’t know how they could get it honest

— and lies come in particularly handy to hide worse things!”

“What can be worse than a lie?” asked Tom. But of

course Grace did not hear.

“So they gave out that on Christmas eve there was a ring at

their bell, and when they went to the door, there was a basket

there, with all sorts of good things in it — a turkey and a plum

pudding, and six mince pies — and what do ye think? (that's the way

liars always overdo it!) a bottle of rich gravy to be heated and

served with the bird! ‘There, that’ll do,’ said I, when Mrs. Shand

showed me that, ‘Gratitude,’ says I, ‘ought to be enough to season

charity, without gravy,’ and on she went holding up a beautiful bag

of ready-made stuffing as well. It made me sick to see her, it

really did! As if anybody would go giving turkeys and gravy to

poor miserable objects that haven’t, and never could have, no right

to such things.”

As Tom went off to his bed that night, he could not help

wondering who it was that so faithfully remembered Grace, and what

she could have done to win their affection and respect. And

then he remembered that God, who cares for everybody, reaches each

by some human hand, though it may give but a chill and a clumsy

touch. “We look at God through those who love us,” he said to

himself. “I always see him behind father, as it were. I

wonder whether anybody will ever be able to see him behind me?“

CHAPTER IX.

MR. SANDISON’S QUESTION.

IT was not very

long before Robert Sinclair received his eagerly expected invitation

to “spend an evening” with the Branders. There was in it a

clause directing him “to bring his young Shetland friend with him.”

But, in the mean time, Robert thought fit to ignore that clause.

He could feel quite sure Mr. Brander had only put it in as a matter

of course — probably imagining that the two youths were living

together, or at all events, seeing each other every day. It

was certainly very kind of Mr. Brander to invite him, thought

Robert, it was quite supererogatory kindness that he should also

invite Tom Ollison. It was not good policy to be very ready to

force one’s friends upon those who might be willing, out of civility

to one, to extend their hospitality to them. If he found that

Mr. Brander proved the sincerity of his invitation to Tom by

repeating it, then it would be time enough to take him, and he was

sure it would be pleasanter for Tom not to be taken to a stranger's

house, until an old friend had a sure footing in it.

But Robert was thrown into a little perplexity by the

Branders' invitation, which was given in the free-and-easy style of

some wealthy people who are quite above consideration of the

limitations of train service and such-like trifles. It was

simply impossible that anybody limited to such arrangements could

come in and out, from Stockley to Bayswater, “to spend an evening.”

If the Branders had been staying in such “a corner” they might have

done it with their own carriage and horses, though they would

probably have preferred to “put up” for the night at some London

hotel. But Robert had no equipage, and to go to an hotel

involved an outlay which made him reflect, though he decided that it

must be made, rather than that such an invitation should be

forfeited. He felt the Branders' want of consideration almost

like a compliment, it seemed as if they saw him on a level with

themselves, and forgot that he had not all the same advantages.

“One can't expect those who don't have to trouble about such

trifles to remember them for others,” he decided.

Still, he did shrink from hotel charges. If he had to

pay them, he would have to withdraw from the savings bank the trifle

he had already deposited there. To be sure, he argued, one

saved that one might invest, and such an extravagance must be

regarded in the light of an investment, for the favour of the

Branders represented to him the road to fortune. But still,

would it not be possible to spare the savings for some other

investment? For if he was to grow into intimacy with the

Branders, he would need many little things, since one must not

parade poverty before rich people. Why should he not ask Tom

Ollison to take him in for one night? This seemed to him a

happy inspiration. He knew Tom had a room to himself, and that

Mr. Sandison was a Shetland man, a bachelor, and one of whom Tom

spoke kindly. His employer had already given Tom a pleasant

holiday. Why should not Tom's employer do him a favour?

The favour was asked and readily granted, so readily and

cheerfully that Robert, according to his nature, decided that the

favour was all on his side, and "that Mr. Sandison and Tom must be

really glad of any change to enliven them.” The only person

who did not seem delighted was Grace, who was not by nature an

entertainer of strangers. One would have thought that she

feared lest Robert might be deaf like herself, for she certainly

wrote her grumpiness so plainly on her visage, that nobody but the

blind could have doubted it. It had occurred to Robert that

this arrangement of spending the night at Mr. Sandison’s

house might prove very convenient and economical for him, during the

several visits which he foresaw he was likely to pay to the

Branders, before that happy consummation of his leaving Stockley

altogether, towards which he was steadily feeling his way.

Grace's sour face first suggested to him a possible check to this

nice little plan. He judged that neither the master nor Tom

would find it very pleasant to have him for a guest, if she set

herself against him on the score of giving her extra trouble.

So he made up his mind to fee Grace; it was economy to give her an

occasional shilling, rather than to spend at least three or four

shillings on "beds and breakfasts." He rather thought that

Grace would draw back from his offered bounty, and that even if she

took it, he would score by it, and by bespeaking her good graces

prevent any necessity for similar propitiation too often. But

though Grace had really expected nothing, she was equal to the

occasion, and to him. Her skinny fingers closed over the coin

as if the dourer was a matter of course. She uttered no

thanks, but looked at it in a way which made Robert feel that she

thought it ought to have been half a crown. By that diplomacy,

Grace secured a repetition of the gift on each of Robert's visits.

She was as greedy of gain as he was, though her ambition was limited

to a few pounds, while his imagination rose to thousands — sometimes

of mere capital — but more and more often of income!

Robert's visits to the Branders and his thrifty retreat from

their grandeur to Mr. Sandison's homely hospitality were repeated

several times, before he attained the desire of his heart and

secured the offer of a seat in Mr. Brander's office. Naturally

the lads exchanged sundry confidences as they lay in the darkness of

the wide attic, into which a stray moonbeam might steal and illumine

the old wheel, which Robert said ought without delay to be put to

its best use, as firewood. Robert soon divined that the master

of the house was "queer;" indeed Grace seldom allowed anybody to

have any doubts on that subject. Tom was led into a solemn

whisper of her assertion that Mr. Sandison did not believe in God,

and hoped for no hereafter. Robert opined “that such notions

would do him no good in his business,” but conjectured that probably

he did not mind that, since he was doubtless a miser and rich enough

already, and would very likely leave Tom all his money if he did not

offend him.

Then he proceeded to tell Tom, who lay dumbstruck, that after

all, he believed he had found out that Mr. Brander was as glad to

secure his services as he was to give them to him. Mr. Brander

was evidently getting tired of over-application to the details of

his business, and he clearly had an aversion to taking a partner and

a strong mistrust of his own head clerk. Robert Sinclair could

quite understand his having a desire to take up some very young man,

whom he could train into his own ways and from whom he need fear

nothing for years, by which time he would have made their interests

identical. Robert Sinclair giggled at that point and Tom

Ollison felt utterly mystified.

Robert went on to say that he thought there seemed to have

been a marvellous intervention of Providence for the purpose of

securing him a career and a fortune. He believed that under

the circumstances it was very advantageous to him to have come from

Shetland — it gave the stock- broking office in the city a delicate

aroma of that “island of mine,” and of “the castle on my estate,” of

which he had already shrewdly observed Mr. Brander liked to boast.

Also, doubtless, Mr. Brander felt that his promotion of a young man

from Shetland would make him popular there, and serve to facilitate

his dealings with a primitive people, apt to distrust strangers, and

to connect gentlemen dealing in finance with those “lawyers” whom

they have held in abhorrence for all generations.

And then Robert went on to talk about Etta Brander. She

went much into society, he said. He heard she was out nearly

every evening, either at a dance, a conversazione, or a concert.

But he noticed he was always invited when she was to be at home.

He thought Mr. Brander was very fond of Etta. He should not

wonder if the father would be very glad for his daughter to marry

somebody who would be, so to say, in the family, and would have only

mutual interests — always provided of course that he was in a

position and had talents, suitable to the family and fit to promote

its fortunes. It was strange—was it not?—and Robert gave

another little laugh, how often the old stories made success run on

these lines! Even Hogarth’s good apprentice marries his

master’s daughter. All that used to seem to him too much in

the region of romance, unexpected, illogical, not to be looked for,

but he saw now that it was in an almost inevitable sequence, not due

to weak indulgence in foolish romance, rather perhaps to wise

restraint from it. And there Robert actually sighed — having

already adopted the singular affectation of offering one’s self a

sacrifice to one’s own ambition and passion for “getting on.”

Well, Etta Brander was certainly a pretty girl — and he supposed she

was clever—and the realities of life must always be considered, and

one had one’s duty to them to carry out.

And there Robert stopped short, checked by Tom’s dead

silence. It only made him feel that he was making a fool of

himself — that probably Tom was quietly laughing at him as one “who

was counting his chickens before they were hatched.” He became

suddenly conscious that his strain of talk was weak and foolish,

that it might even be bad policy. It was the last time for

many years that Robert Sinclair was betrayed into such forecasting

confidences.

In reality Tom was silent, not in mirth, but in misery.

He did not think of Robert’s words in any special connection with

Robert. They might be either true or false concerning Robert’s

future, and yet there might be a truth in them very damaging to what

had always seemed to Tom such a pretty ideal — the humble lad,

heart-smitten by the maiden above him, silently doing his duty

without any hope of her, till gradually duty brought him out beside

love, on a level with her! Misty castles in the air had often

risen on poor Tom’s own mind, all the more silvery and ethereal,

perhaps, because there was no possibility of his putting an exact

foundation under them. Sweet faces had glanced upon his vision

from those wonderful surging waves of London life (from whence do

glance some of the sweetest faces of the whole earth), and Tom had

thought how would it have been if the dim, silent old house in

Penman Row had been lit by the good beauty of a daughter? He

and she might have been such close friends; she might easily have

liked him a little if her father praised him. And then perhaps

some day, when the master grew too old and tired for his work and

thought regretfully of leaving the old place, Tom might have asked

eagerly, “Why should not they all stay on together?” and father too

might have liked to come down from Clegga, and the two old friends

and schoolfellows could have smoked a quiet pipe together, and

perhaps have made a little fun of the young people, with their grand

new theories, and their daily practice humbly halting after.

Dreams! dreams! And in his own particular case, Tom Ollison

had always known these were nothing more, for the house in Penman

Row was a lonely one, and his father’s friend was a kinless man.

But if there is something vexatious in having a night vision of

angels and heavenly music and beauty dissected down into a nightmare

remembrance of Twelfth-day cakes and Christmas numbers, can there

not rise an untold bitterness when youthful ideals of loving service

and loving triumph are declared to be mere euphuisms for worldly

prudence and success? Poor young people, who have not yet

acted out their own little drama on the stage of life, are terribly

susceptible to any whisper that life has no drama at all, but only a

very cleverly managed marionette show.

Robert had fairly left Stockley and had even been for many

months in Mr. Brander’s office within a stone’s throw of the Stock

Exchange, before he saw fit to tell Tom that the stockbroker had

been constantly asking when the other young Shetlander was coming to

put his feet under the mahogany of his dining-room in Ormolu Square,

Kensington. Tom was not very eager to accept the invitation.

Perhaps he lacked a laudable desire to see society in all its

phases; perhaps he believed in the quaint fable about the danger of

the golden jar and the china one floating too near each other;

perhaps he was like that Shunamite woman who was so tamely content

“to dwell among her own people.”

But when Mr. Sandison heard of the invitation, he bade Tom accept

it.

“Take a rich man’s kindness for what it is worth,” he said, in his

grim way. “He can’t go without half his crust that he may offer it

to you, that is not in his power. But he does his little best when

he orders

another partridge for your pleasure.”

Mr. Sandison had such slight delight in personal conversation that

he had actually never heard the name of Robert Sinclair's new friend

and patron up to this point. Now Tom mentioned it casually.

The master bent down lower over his desk and seemed so absorbed in

his papers that Tom did not think he was any longer interested in

the matter. Suddenly, however, he looked up and said in his very

harshest manner, — “Have these — Branders — any children?“

“One,” answered Tom briefly. What could it be in the dry manner of

the old bachelor which made the hot blood tingle on the youth’s

cheek.

“Son or daughter?” asked Mr. Sandison.

“One daughter,” Tom replied again.

Mr. Sandison went on with his writing. And his thoughts were trite

enough, for he only reflected that the world is a little place, and

goes round, so that whomsoever we have met once, we may certainly

look to

meet again, and that life is a history that repeats itself, so that

as we turn and watch those who come after us, we are apt to see them

fall into the same pits which waylaid ourselves. It is our business

to cry out and

warn them of their danger. Mr. Sandison knew that a word from him,

hinting that this visit to the Branders had better not be made,

would have been rather welcome to Tom than otherwise. But then, how

can we be quite

sure that there is still a pit at the same turning in life where

there was one in our time? Alas, we cannot be quite sure, until we

see the runner tumble in, and then our warning is too late! But if

we cry out too soon, we

may but turn him aside from a pit which has been filled in, and is

now quite safe, and startle him on to some ground unknown to us,

where there may be gins and traps we wot not of [Ed.―archaic

use meaning 'not aware of']. A careful and

thrifty youth may be

developed into a miser by the warnings of a spendthrift against the

extravagance which ruined himself. A reserved nature may grow

unsocial and self-righteous under the exhortations of the

enthusiastic and warm-hearted who have suffered themselves to be easily misled by bad

companions. It is an old truth, that our experience is for

ourselves, we cannot teach it or bequeath it. Frantic efforts to do

either more often lead to harm

than good.

Yet the wisdom earned by past mistakes and sufferings is not wasted. What we are is the result of what we have been, and what we have

done; and what we are will always tell as the most powerful warning

and encouragement to those who follow.

Mr. Sandison went on with his writing, and held his peace a while

longer.

Had he any right to infer that what certain people were twenty years

ago they still remained? Was he himself the same man now that he had

been then? And had he any just reason for judging that a child

must resemble its parents? Had he not sometimes, in bitter rebellion

against the very doctrine, been ready to assert its flat opposite? How was it that just now, when an ancient wrong was astir in his

heart, it seemed

so likely to be true? Oh! how often he himself had had to hear it! Might he not take his revenge on the world, and assert it this once? It would be but saying it once for a hundred times he had heard it,

and in such a

percentage as that it must surely be true! Besides, what was the use

of setting his own private feeling against the accepted wisdom of

the world? The wisdom of the world had always triumphed over his

feeling, why

should he not let it have its way now, when it beat time with his

own passionate bitterness?

No, never! Though the cruel law of hereditary bondage might be true

in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, yet there was his own feeling

against it, and that must count for something. If the inexorable

laws of

the dumb universe do bind iron chains about the race that struggles

among them, that is enough no need that humanity should add another

link to its own fetters.

In the white heat of a personal agony his own heart had beaten out a

passionate protest against the easy verdict of a heartless world. In

a moment of suffering from an old personal wrong, should he throw

down his own arms and snatch at the base weapon from which he had

striven to defend himself? No; such was not even a meet opportunity

for him to admit that the weapon might not be all base, that there

might be

some temper in its metal.

To honest hearts, that which they have condemned as a lie is never

so hateful as when it presents itself in their own interest. And yet

there was a fiery indignation within him which would not keep wholly

silent.

Bitterness against his own enemies, against facts which had darkened

his own life and wrecked his own faith, he could suppress, if he

could not conquer. But he could not help saying, —

“Go out into the world as much as you choose, Tom, only never care

for anybody or trust anybody. Study your kind as you would the wild

beasts at a show, and be good to them, only always feed them through

the

wires of a wise indifference. You may hold up flaming hoops for them

to jump through if you like, then they will fear and obey you but

don’t begin to caress them, unless you do so as an experiment in

getting bitten. So

much for the world of ‘affairs,’ as the French call it. As for the

social world, when you go there take a mosquito net as part of your

outfit. And remember it is the female insects who sting.”

Tom said not a word in answer to this tirade. It did not make him

really think a whit less of humanity, as the perusal of some chatty

newspaper articles, or the hearing of some playful,

semi-philanthropic

speeches might have done. It only made him realize that there are

terrible risks to be run on the field of human life, and that he

need not be too sure of escaping where his father’s old friend had

certainly received some

deadly wounds.

How much cynicism is the growth of individual pain! He who is too

proud or too gentle to name or to wound his own foe is rather apt to

curse or to lament on a grand scale. Woe be to those whose deeds

turn

their brethren into accusers of the world or of society, of their

sex or of their rank

“You had better have something to eat before you go to their grand

late dinner,” said the bookseller, with a return to something like

his ordinary manner. “You remember what our chapter said last night,

‘When

thou sittest to eat with a ruler consider diligently what is before

thee, and put a knife to thy throat, if thou be a man given to

appetite.’ It’s a mistake to want anything, or to seem to want it,

in this world. But repose of

manner and patience of mind are apt to depend a good deal on being

somewhat satisfied beforehand.”

Tom could feel clearly enough that his master’s words came from

thoughts which were quite behind his little act of household

consideration.

There had been some friction earlier in that day in the household in

Penman Row. Grace had detected the youthful London shopboy in the

act of pilfering from her larder, and Grace had been for sending off

for

the police, and giving the lad “a lesson,” which might well leave

him with no power to learn anything else but evil for the remainder

of his days. Mr. Sandison had entirely vetoed this plan; he had had

the boy into his

counting-house, and had told him, in a few simple words, that this

sort of thing must be first punished, and must then cease. He had

told him that his act was a shameful one, only that he was young and

foolish, and

that he had not got to be ashamed of it (the lad was trembling

abjectly) so much as to take care that it, or anything of a similar

kind, should never happen again.

“If I had had a son of my own he might have done the same, till he

knew better,” Mr. Sandison had said. “And if he had done so I must

have punished him to help him to know better, and to show him at

once

that evil must end in pain sooner or later. Then, and not before, I

should have forgiven him, and then I should have trusted him again. So if I am to forgive you I must punish you. Therefore if you wish

forgiveness you will

ask me to cane you. I give you ten minutes to think about it.”

The lad stood mute and shamefaced for about two minutes. Then he

went into the shop and brought back a cane, which he put into his

master’s hand. Mr. Sandison shut the counting-house door upon them

both. When the lad came out his face was pale and shining.

Grace was vexed. “No good would come of it,” she prophesied. “Fred

would only be more cunning in his dishonesty. She wondered her

master could soil his hands chastising such trash! It would serve him

right if Fred turned on him, and brought some friend to say that he

had been unlawfully assaulted and beaten. Only Fred had no friends,

and what could one expect of the like o’ that? She had told the

master from the

first that there would be nothing but heartbreak in having one of

those children about the place.”

Grace could not hear, but she could see the interrogation on Tom’s

face, as he said aside, half to himself, half to Mr. Sandison.

“Those children! What on earth does she mean?”

“Why, didn’t you know Fred was an illegitimate child,” she snarled,

“a workhouse foundling, the very worst sort of a bad kind?”

Tom reflected for a moment. He had learned terrible facts of human

life since he had lived in London. He had wondered sometimes how he

could bear to go quietly to his peaceful bed while he knew of the

tragedies and horrors being enacted within a stone’s throw of Penman

Row.

“Isn’t all that way of thinking awfully cruel?“ he said to Mr.

Sandison in a low voice. “Is it not awfully unjust“ he added

emphatically, as if the sum of all evil was in that word. “And how

it seems wrought into

public opinion, into its common phraseology even! Why should the

very brand of shame be put on the one who did not win it for

himself? Why should we say that such a one is an illegitimate child? Should we not say

rather that he had the misfortune to have illegitimate parents?”

Mr. Sandison did not answer. Tom looked up, fearing that his plain

speech had been somehow in fault. There was a strange expression on

the bookseller’s face, a curious, pained half-smile, such as one

might give who had so strained his vision in watching for something,

that when it came in sight he could scarcely believe his eyes.

“Tom,” he said slowly, “did your father ever tell you anything about

me?”

“No, sir,” answered Tom in some surprise, “except about what friends

you both were,” he added ingenuously.

“Thank you, Tom,” said Mr. Sandison after a moment’s pause. “Now go;

it is time that you started for your visit to Ormolu Square.”

As Tom passed out of the house, after he had made his simple toilet,

he saw his master standing at the dining-room window. He had opened

it, and having collected a little handful of crumbs from the

bread-basket, he was spreading these on the sill. There were a few

sparrows that lived among the eaves of the dismal yard.

CHAPTER X.

IN ORMOLU SQUARE.

ORMOLU

SQUARE was a big block of pretentious buildings of the kind

which at that time were being rapidly erected in what had hitherto

been a quiet, old-world suburb. Since then, they have trampled it

out

of existence, nothing remaining now even to tell its story, save

here and there a rather dilapidated ornamental cottage, on which

evidently nothing is spent for repairs, and which is only lingering

on a respited existence

till somebody dies or somebody comes of age. But at the time of Tom Ollison’s first visit to the Branders, the locality was still full

of stately houses, mellowed by age, and set behind gardens as prim

and as quaint as

the garden of Stockley Mill and scarcely less luxuriant, while a

pleasant rustic flavour hung about the dairies and market-gardens

with which the place then abounded. Tom had been informed that he

might rely on

Robert’s being in Ormolu Square before him, because that thriving

young gentleman would accompany his principal home from the office. He often did so. There could be no doubt that he was a great

favourite with Mr.

Brander, of whose views concerning him and his future he had not

formed a very mistaken estimate, though probably that gentleman

would have been startled to find that another mind could give such

definiteness to

thoughts which lay dim and nebulous as dreams in his own. There was

another reason for the grace Robert had found in his employer's

eyes, which would not have been so flattering to that ambitious

youth. This was,

that Mr. Brander felt thoroughly at his ease with him. He could

think aloud with Robert Sinclair. There were reasons why it was not

with everybody that he could do this with comfort to himself. There

were men who

admired his “sharpness” and envied his success, who he knew would

have been ready with sneer and ridicule, to detect him in the little

lapses of phrase or manner which are held to betray the self-made

man, when

they are observed in one, though they may pass unnoticed or with

indulgence if displayed by a boor of long descent. There were other

men who he knew honoured his unflagging industry and perseverance,

who would

have turned with disgust from some unguarded admission of the

principles and the objects on which and towards which he worked.

There were others—his own head clerk was one—who while ready enough

to abet

him in all his mercenary schemes, had yet a singular and cynical

knack of turning them inside out, and making painfully manifest

their seamy side, which he would willingly have ignored.

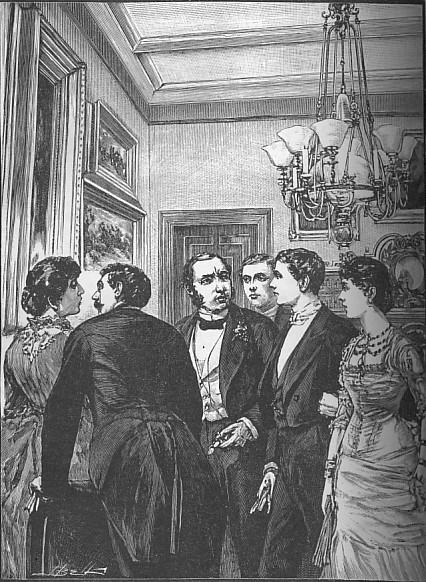

"In Ormolu Square."

Robert had none of these disadvantages. While his own manners were

quiet and agreeable — thanks to his father's teaching and his

mother's training — he had yet lived among simple folk, and

occasional slips on his

part in phrases or etiquette set Mr. Brander at ease concerning

those solecisms, on which the comments of his own wife and daughter

kept him forever sore. Again, very different as were his views of

morality from

those in which the young man had been reared, they clearly never

startled Robert; he gave them a moment's reflection and adopted them

as if they had been his own from his birth. And lastly, he never

disturbed his

patron in that belief in his own generosity and good-nature in which

Mr. Brander delighted to hug himself.

Twenty times a day did the stockbroker say to himself that “that boy

was born to get on.” Sometimes he said so — not to himself. Such

prophecies have a tendency to self-fulfilment. They give prestige;

they influence

the opinions and the actions of others. The head clerk regarded

Robert Sinclair with a half-suspicious interest; the other office

myrmidons were deferent. Everybody inferred that his “people” had

“placed him” with Mr.

Brander; Robert took care not to disturb such an inference. And yet

had the truth been known, it might have almost been to his advantage; for people believed in Mr. Brander's investments, — they always

turned out

so well for himself,—and nobody would have suspected him of

investing kindness without very good reasons of his own.

The door of the house in Ormolu Square was opened by a manservant,

who, if he was not too stolid to notice anything, must have wondered

to see the swift fading of a smile on Tom's face; for he had

expected to be

admitted by Kirsty Mail. He had never dreamed of menservants, and

had felt sure that among the women she would have been on the

watch to do this courtesy to her fellow-islander.

He was led up the stone staircase and ushered into the great

drawing-room, big, and bright, and perplexing with mirrors on every

side. Mr. Brander met him with a cordial hand-shake, though perhaps

there was not the

best of breeding in his remark that “this is rather different from

where we met first, isn't it?” He presented him to Mrs. Brander, and

to Etta (who made a feint as of having never seen him before), to a

young man whom

he called Captain Carson, and he finished off by saying jovially

that he did not suppose he needed to be introduced to Robert. Then

he said, with a sudden change to fretful impatience, “When will

dinner be ready?” This

made Tom turn hot all over, as if he had kept the family waiting,

though he knew that according to his own watch and to all the clocks

which he had passed on the way he was on the early side of

punctuality. Fortunately

it was not many minutes before the manservant announced that "dinner

was on the table," and the whole party adjourned in formal

procession to the dining-room.

This room was as big and as bright as the other, only its walls were

more subdued in colour, and instead of the dazzling mirrors they

were hung with battle-pieces in oil, and with two full-length

portraits of the master

and mistress of the house. The artist had "done his best" for them

both, but there was nothing in either face to balance the wonderful

technical dexterity he had thrown into Mr. Brander's dress-coat and

Mrs. Brander's

brocaded train, and into other points which should have been mere

accessories to the human interest. Probably the lady had been a

pretty girl in the days when her husband had been a good-looking

young fellow, but

in middle life, when faces ought to grow grand as the gentle

processes of time develop the invisible but indelible’ record of the

years that are past, she was only paltry and petty, as he was proud

and petulant.

Mr. Brander saw Tom’s eyes rest on these pictures.

“Ah, you know who those are, I see,” he said. “Pretty good, I

reckon, aren’t they? — and so they should be for the money they

cost. Three hundred pounds apiece, not a penny less, though I let

him exhibit

‘em in the gallery, which ought to have done him good, for a lot of

my friends saw them there, and it set them up to get their portraits

taken too. Advertisement is the soul of trade. But he seemed to

think the obligation

was on my side in that matter too.”

“Exhibition in that gallery is like the hallmark on jewellery,”

observed Captain Carson with a drawl of perfect indifference, as if

his remark was quite spontaneous and in response to nothing. “When

you come to

sell those pictures, the fact of their exhibition there will

increase your chances of getting back some of your money.”

“So I was given to understand,” said Mr. Brander quite cordially. “Therefore I looked out all the notices of that exhibition in the

papers, and wherever the newspaper men gave a good word to our

portraits, I cut

out the paragraph. They are all pasted together, and stuck on the

back of the picture frames, under a strip of horn to preserve ‘em,

and then they are sure to be to the fore when they’re wanted. There

were a fair number

of good notices. I know two or three newspaper men. They spoke

particular well of Mrs. Brander’s dress, and of the table-cover on

which my hand is resting.”

“My friends do not think that my portrait flatters me,” said Mrs.

Brander, in a thin, acid voice.

“It does not do you justice,” answered Robert Sinclair.

“It looks much too old. I should take the lady in the picture to be

fully forty years of age,” observed Captain Carson, with the

slightest perceptible elevation of his eyebrows. “And it was painted

two years ago,

was it not?”

Mrs. Brander knew she was over forty-five, though her hair and her

dress were of the same fashion as her daughter’s. She gave her head

a little deprecatory shake, and simpered, “Ah! Captain Carson.”

“But portraits never are a good investment, do what you will,”

remarked Mr. Brander sadly.

“One doesn’t think of them in that light,” hazarded Tom. “Who would

ever think of selling them?”

“Pictures will change hands, in the course of a few hundreds of

years,” said the captain imperturbably. “Just as even family Bibles

and wedding rings are to be found in the pawnbrokers’ shops.”

“Well, I suppose the artist’s name — (what was it, again, Etta? it’s

always slipping my memory)—will stand for something” Mr. Brander

consoled himself.

The captain put up his eyeglass and took a leisurely survey of the

works of art. “One wonders how they would be described in a

catalogue of sale — weird idea, isn’t it?“

“They were called ‘Portrait of Mr. Brander,’ and ‘Portrait of Mrs.

Brander,’ in the exhibition catalogue,” said the master of the

house. “I hear lots of people were asking who we were.’’

“‘Mr. and Mrs. Brander’ would not do in a catalogue of sale,”

pursued the captain quite serenely.

“‘Portrait of a lady,’ and ‘of a gentleman,’” suggested Mrs.

Brander. “I’ve seen many old pictures described so.”

“Ah, especially Vandyck’s,” said the captain. “There’s nothing else

to be said about most of his. But in this case, I doubt if the

description would be characteristic enough. What would you say to

‘Full-dress

costumes of the Victorian era’? That would give them antiquarian

value, don’t you see?”

“The very thing!” cried the unconscious stockbroker. “They might not

get treated as portraits at all. That was clever of you, captain.

Perhaps I shan’t have invested badly, after all.”

Then conversation flagged a little, which was small wonder, for

between gigantic exotic plants and massive pieces of silver, none of

the diners had a perfectly unobscured view of the others. The plate

on the

table was perfectly oppressive, everything was plate. There were

several courses, and Mr. Brander did not scruple to recommend sundry

dishes on the score of their cost and rarity, telling his guests

they could not get

such things every day — not even Captain Carson at his club. The

dinner rather puzzled Tom; nearly all the viands which he knew at

all, were of a kind that he had seen in Penman Row months before,

and which

Grace had since pronounced to be “out of season.” Though he was

certainly becoming accustomed to many strange varieties of life and

fashion, he did not yet distinctly realize that the locomotive power

of many

ships, and the skill and strength of scores of captains and hundreds

of seamen, the capital of many traders, and the labour of numberless

labourers are regularly wasted in nothing more productive to the

general good

than the furnishing of summer fruits in midwinter, and winter viands

at midsummer.

“Have you heard news from Shetland lately, Mr. Ollison?” asked Mr.

Brander, sipping his sixth glass of wine.

“I heard from my father last week, sir,” Tom answered.

“When did you hear, Sinclair?” asked the stockbroker of Robert.

“This morning,” replied Robert.

“No news in particular?” questioned Mr. Brander

again, with the self-satisfied smile of one who is reserving a bonne bouche.

“Nothing at all — the letter was only from my mother,” said Robert

easily.

“I hope they are all quite well at Quodda,” inquired Tom.

“Oh, yes, thanks,” returned Robert, “all quite well. At least, my

father has been rather poorly.”

“I’m sorry for that,” observed Mr. Brander, evidently absorbed with

something apart, “perhaps that accounts for her not telling you the

news.”

“Oh, it is evidently nothing, for my mother is easily alarmed, but

clearly she is not anxious in this case,” said Robert. “But what is

the news, if we may ask, sir? “

“That there have been whales in Wallness Voe,” said the stockbroker,

looking round with a beaming face. “I had the telegram concerning it

after I came home from office, just while I was dressing for

dinner.”

“What’s the significance of that?” asked Mrs. Brander, who had had

too long an experience of her husband to doubt that anything which

pleased him must have some very solid basis.

Less experienced Etta said aside to the captain, “Horrid things! They’ll make the place smell for miles. The castle will be

unendurable.” She liked to mention the castle to the captain, and

she liked best of all

to mention it with depreciation.

“What’s the significance of it?” echoed Mr. Brander. “Why, as it was

a large shoal, and blubber is up in the market just now, it will

bring me in a round £300 or so, not a penny less, without a bit of

trouble or

risk on my part. That’s the way to make money, isn’t it, young

gentlemen?”

“Jolly,” ejaculated the captain. Robert Sinclair murmured assenting

admiration. For once, it was Tom who was absorbed in mental

calculation. He knew well enough about these matters. If Mr. Brander

reckoned on receiving £300, that meant that the shoal caught had not

been worth less than £900, since according to island use and wont,

“the proprietor of the land adjoining the shore where whales are

stranded,

obtains a third of the proceeds, while two-thirds are divided among

the captors.” Tom could easily guess that not less than a hundred

men would have been engaged in capturing these monsters of the deep,

to say

nothing of half-grown lads. The share, therefore, of those who had

encountered all the risk and toil of the adventure would be

somewhere about £5 a piece. And Tom, who knew most of the islands

well, gave thought to

many a humble home about Wallness, where, during the ensuing winter,

this moderate windfall would make all the difference between need

and debt, sufficiency and peace.

“It’s an odd thing is luck!” mused Mr. Brander. “This hasn’t

happened at Wallness for over thirty years. If poor old Leisk (that

was the late laird of Wallness and St. Ola) had only been able to

hold on one more

year, this would have fallen to him instead of to me. Providence

seems to fight against some men and for others. Luck’s a queer

thing, but I do seem to have it.” It never occurs to some people to

doubt that Providence

must hold the same ideas about fortune that they hold themselves. Mr. Brander spoke modestly, as if he didn’t want to claim too much

credit for himself. The Psalmist says that when we do good for

ourselves others

speak well of us; he might have added, for it is equally true, that

when good — or what we call good — happens to us, few of us can help

thinking well of ourselves! There is a true hit at poor human nature

in the old

nursery rhyme, —

|

Little Jack Homer sat in a corner

Eating a Christmas pie;

He put in his thumb and pulled out a plum,

And cried, “What a good boy am I !“ |

“At the same time,” mused Mr. Brander, “nothing of the sort is as

profitable nowadays as it used to be. In old Leisk’s father’s time,

the laird got half the value of a shoal. At that rate, I should have

got £450 today instead of £300."

"Oh, but the common people are coming to the front now," said Mrs.

Brander, with a fine scorn. "They are to have everything, whether

they know how to use it or not." Then after a moment's pause, she

added, “I think

you must indulge Etta in the fancy ball she was begging for the

other day. You can't call it an extravagance when you have just had

a pretty little windfall like this."

"Oh, Etta shall have her treat. I'll give it all over to the

ladies," said the stockbroker, who liked to parade his domestic

indulgence. “I shan't be a ruined man yet a while."

"You said you were last week,” observed his wife. There was often

much badinage of this sort in the family.

"Ah, that was when I thought government was going to play so false

as to agree to a treaty which would let the New Atlantan Federation

shake off the loan their abdicated king got from us. Not that that

would have

ruined me, only if once any government begins fool's play of the

sort, one doesn't know where it will stop. Capital doesn't want

anything to do with sentiment, it only wants interest and security."

“The New Atlantan people are reduced to terrible straits by the

taxation imposed on them by their late rulers," Tom observed

quietly. The newspapers had been full of the slow starvation and

subtle pestilence which

were breaking the heart and decimating the ranks of the hard-working

and law-abiding peasantry of a remote country. There was a fund for

their relief in the city even now. Tom and Mr. Sandison had talked

over the

matter. Mr. Sandison's eyes had gleamed, and his words had been

fierce. Tom had innocently suggested a contribution to this fund, as

a relief for his feelings. But Mr. Sandison had said bitterly, that

no money of his

should be filtered through the blood and tears of the oppressed,

back into the pockets of idle usurers of his own race —that to give

money to the suffering Atlantans was only to send it by a roundabout

way to the

Atlantan bondholders. "Then must the poor people be left to perish?"

Tom had asked sorrowfully. "If they perish, in making manifest an

evil, and bringing it one step nearer to its end, they have not

lived and died in

vain," the bookseller had retorted. And then he had relapsed into

gloomy silence. And he never told Tom that by the next mail he wrote

out to an official in New Atlanta, and bade him search among the

orphans made

so by the famine, and pick out the most promising boy, and send him

to England, to be educated at his expense.

Mr. Brander's face darkened at Tom's remark about the Atlantan

destitution, and Robert Sinclair said glibly, —

“There is a great deal of exaggeration in those newspaper reports,

and they do much harm."

“Ay, that's just it,” rejoined Mr. Brander readily. “The New Atlantans are just a set of idle beggars. Talk about toiling lives! I don't believe once in a million of them does as much work as I do. There was no talk about

destitution when they wanted to take our money; but only when we

want our interest. We are not asking for our capital, mind, only for

its interest. Where would they have been without it, if they are so

poor with it? What has become of it all?”

“It was made away with by the king and the court,” pleaded Tom.

“The people who have got to pay the interest have never benefited

by one farthing of the capital; I don't suppose in such a country

as that is, that they

even knew it was being borrowed. They only knew they had more and

more taxes to pay. Don't you think all those who have money to lend,

should take care what is to be done with it, or at least ascertain

that those from whom they mean to exact repayment are anxious for

the loan?”

“The Atlantans should not have had a king for whom they did not mean

to be responsible,“ decided Mr. Brander.

“They did not want him,“ said Tom. “We know

he was forced upon them by a foreign power which was too strong for

them to resist at the time. They were always trying to get rid

of him. They have succeeded at last.“

“And you'll see they won't be a bit better off,“ growled the

stockbroker.

“They cannot be while they groan under the burdens

he has left

behind him,“ said Tom.

“And I suppose we are to lift off their burdens, at our own

expense?“ laughed Mr. Brander. “Very fine, young man! You haven't

any Atlantan bonds, that's very clear. No, no, business is business

and charity is charity.

I'm not willing to give up my own, but I'm willing to do anything

that's right and reasonable. I wrote a cheque for fifty pounds for

the Atlantan fund only yesterday. That's the sort of sympathy I

have. Put 'em on their legs

again, says I, and let 'em pay their debts.“ (Tom thought of Mr. Sandison’s words.) “Have you given your mite yet, young man, as

you’re so fond of ‘em?” And Mr. Brander laughed heartily, and felt

that he had covered

young Ollison with confusion.

“They are a set of mere savages,” observed young Carson. He had been

abroad with his regiment once or twice, and knew exactly as much of

the populations among whom he had stayed a few weeks, as a

foreigner would, who made a short visit to London, and had occasion

to give occasional orders to a few waiters and shoeblacks. “Nobody

who has not lived among them can realize the difference between them

and

ourselves.”

“Ah! well,” said Mr. Brander, relapsing in to his favourite tone of

philosophic toleration, “we must not crow too loud. We have not all

been such great shakes ourselves for so long, but that they may soon

overtake us. Why, there’s been things done in the British Isles not

so very long ago, that makes one’s blood run cold to think of. Think

o’ the Cornish wreckers! Heartless wretches, misleading men on to

rocks, and

snatching their goods from them when they were drowning, and killing

‘em if they didn’t drown fast enough. I don’t know if they ever did

that exactly in Shetland,” he went on, turning to Robert. “But it’s

a common

fact that there they were very reluctant to save drowning men.”

“They say there’s a lingering feeling of that

sort to this day in some parts,” said Robert

― “remote parts, of course.”

Mr. Brander shook his head lugubriously. “That’s where it is,” he

said, “that we get led into such mistakes by comparing these people

with ourselves. It’s quite natural that everything should be

different with

them; they would be no more able to appreciate our houses and our

comforts than our ideas of morality and mercy.”

Tom Ollison’s Norse blood was on fire. “You should not say what you

said about the people nowadays, Sinclair,” he said. “At any rate,

you should not say it with-saying something else. Why don’t you tell

how twelve Whalsey men three times risked their lives to bring off

from a little rock the two poor survivors of the ship ‘Pacific’? Why

don’t you tell of that other shipwreck, when every life was saved by

the courage and

resources of the islanders, one brave man cheering on the rest, by

telling them ‘not to think o’ the big waves, but aye o’ the drowning

men’?”

Mr. Brander made no observation on this patriotic little outburst. He only said, “Can anything be more horrid than that story, whose

truth I have never heard disputed, among some wrecked mariners, who

were

very nearly landed on one of the smaller islands, when one of the

old fishers warned the others that their winter store of meal would

scarcely suffice for themselves, and that what these strangers would

require would

have to be taken out of their own mouths? Whereupon, after a little

debate, the half-perished men were summarily thrust back into the

sea.”

“Oh, papa!“ cried Etta, “don’t tell such horrid things!”

“Horrid enough!” said Tom, “and yet, there is something to be

pleaded for those poor people — something to be urged in mitigation

of their alleged reluctance to save drowning men at all. Think what

those

drowning men, when saved, must have often proved — pirates of the

seas, murderers and ravishers, the Ishmaels of other lands, who

probably had taught the islanders many a bitter experience. And as

for Mr. Brander’s

terrible story, let us remember that they stood so near the edge of

starvation that it seemed to them a matter of a life for a life —

not their own life either, but the life of innocent wife and child’

“I am sure no woman would have wished such a thing to be done for

her sake,” said Mrs. Brander. “It is against womanly instincts,

which are all for mercy and self-sacrifice.”

“I don’t defend the people. I don’t excuse them,” cried Tom, feeling

how utterly he was misunderstood. “I only want to account for it as

justly as it may be. Heroes would not have done such a thing, but

whatever we may hope we would do ourselves, we must not be too hard

on those who, being sorely tried, do not prove heroic.”

Tom and Captain Carson both left the dinner-table when the ladies

rose. Mr Brander poured himself out a glass of brandy and bade

Robert remain with him; he wanted to dictate a business letter,

which must

be despatched that night.

Mrs. Brander left Etta to pour out tea from the silver service,

which was set forth on the gipsy table, and to exchange sparkling

whispers with the captain. She herself sank down on a billowy chair

and took

possession of Tom.

She asked him where he went to church; she trusted he was not like

so many young men, who neglected that duty altogether. She did not

seem quite contented when chapel in the East End of London,

where an aged clergyman had spent a long life in gathering about him

a flock of starved and bewildered human sheep and lambs, and now fed

them with the plain, practical, spiritual food which was convenient

for them;

the quiet worker and his quiet work going serenely on amid the noisy

rush of common religious and philanthropic fashion, like an oak

slowly growing in the midst of tares. Doubts had come to Tom since

his arrival in

London; problems had started out before his eyes, which the simple

creed of his childhood had scarcely sufficed to work out. Peter Sandison himself had lain heavily on the young man’s soul, with his

unhappy face,

his haunting eyes, the strangely soft tones of his voice, his swift,

straight insight into the heart of the rights and wrongs about him,

and his significantly dead silence on those subjects of which Grace

had unhesitatingly

asserted his unbelief. Tom knew no more of his master’s past than he

had known on the day when they first met. He knew as little the

secret of the locked-up rooms whose doors he passed night and

morning, as he

did of the mystery between the sealed leaves of the Bible. The youth

was living in an atmosphere of doubt, if not of despair, which

affects faith as the subtlest argument or the strongest logic cannot

do. Tom’s healthy

practicality had alone saved him from succumbing. “I can’t do

without God,” he had said to himself "nor without feeling that God

wants me as much as I want him. Why, I couldn’t even stick to Mr. Sandison, unless I

believed something that he doesn’t believe — if he doesn’t, at least

“— for Tom was growing more wary in his acceptance of people’s

opinions of others’ creeds or conduct. So he had followed that

instinct to seek and

find its proper nourishment, which surely none will deny to the soul

of man, when we know the creeping strawberry has it. Faith, he

found, revived in the sunshine and cheer and human kindliness of

Stockley, where he

had gone again and again. “I’ve read somewhere that what’s true in

the sunshine is also true in the dark,” argued Tom, “and that means,

too, that the sunshine finds out what is false in the dark.

Therefore, let one get into the sunshine as much as one can.” And Tom had turned from all

mere Christian apologetics, and had persevered in a search after

this soul-sunshine, until he found it in the fellowship of that poor

little chapel. There

was something undeniably real in the gospel which had lifted that

congregation, almost to a man, out of the very mire, and had set it

on its feet, and kept it straight and cheerful in the teeth of

bitter struggles for very

life, in which the victory was by no means always against want and

woe in their harshest forms. “None of us have died of

starvation—yet,” said the old clergyman, “but a good many of us have

had to go to the

workhouse. Well, maybe that stands for the arena and the wild beasts

for the Christians of to-day.”

Mrs. Brander heard Tom’s account of his fellow-worshippers, with a

silence which had a something of disapproval about it. She summed up

by saying “that it was very interesting,” only she wondered Tom had

not joined a certain congregation which Tom knew worshipped with a

good deal of clamour and sensationalism not very far from Penman Row;

its pastor was such a remarkable person, and had such a power of

attracting influential people about him; she supposed there were

really more people of wealth and influence in that congregation than

in any other in London; it would be really an excellent thing for a

young man to

belong to that church. Of course, she had the utmost sympathy for

what might be called “mission services,” but it seemed queer to

think of belonging to one; that was quite different! One longed to

do good to poor

people. She had gone once or twice to the Refuge for Destitute

Strangers, in which a great friend of hers took much interest. But

really the people were so very poor and dirty and uncared-for, that,

with her delicate

constitution she was afraid she might “catch something,” and there

was Etta to be considered. These people were very hard to reach; one

of them had spoken most rudely and cruelly to her great friend only

last

Christmas day, though the dear soul had such a sweet spirit that,

after the first pang, she tried to pass off the incident as a mere

trifle. But one liked to do what one could, and, though she herself

could not do much

work for anything, she was so fragile, and so over-occupied with

social duties — yet she gave her influence on as many committees as

possible, and attended a great many meetings. She was just now

greatly

interested in the formation of a society for redressing the wrongs

of Russian priests — she dare say Tom had heard of it, and of the

good work it purposed to do.

She had spoken almost in monologue, only broken up by interrogative

tones, to which Tom had duly responded. Then she asked him about