|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XIII.

DIVIDING WAYS.

WHILE Tom went

back to his duties, sorrowfully thinking what a tangle this world

is, and how much pitiful excuse there is for the errors and follies

of others, and how little safety for ourselves, unless at every step

of the way we look up for the guiding of an unseen hand, and down at

the path for the footprints of the Master, Robert Sinclair was

speeding away to the north, with his mind full of many things.

“I must be prompt and decided,” he mused. “My mother is

a woman who is always easy to lead, unless her own mind is fully

made up. They won’t be able to go back to Quodda. There

will be a new schoolmaster in the schoolhouse, and I don’t know

another house into which they could put their heads — they couldn’t

live in a mere hovel, though of course they will have to cut their

coat according to their cloth (and that will be narrow enough!), and

my mother would make the best of whatever was needful.” So

far, he thought, though silently, in words; but there was a

reflection beyond, which he left unexpressed, even to himself — a

thought that since their poverty might be little beyond destitution,

it would be well that they should not endure it in Shetland, where

the Branders were almost sure to go, sooner or later. He had

not the remotest idea of what Tom had hinted —that the mother and

sister should join him in the south, and either live with him in

London or near him in Stockley. “If only my father had lived a

few years longer!” he sighed. “By that time, doubtless, I

could easily have done for them everything I should like — without

crippling myself. If one has to give away one’s

first little savings, how are they to increase so as to be of real

service to one’s self or to anybody else? If I managed to

spare them thirty or forty pounds a year out of my little salary,

how could I ever get on? It would not be the mere pittance

which I should sacrifice, it would be all my prospects of any future

wealth. If I could only get on unburdened for a few years, I

should be able to give them enough and to spare!”

Oh, how dangerous it is when future generosity looks so easy

and delightful, while present duty seems so hard as to be

impossible! When we think of what we will do, when certain

circumstances have come to pass, and not of what we can do in the

existing necessity! And we forget that the changes to which we

look forward will be more searching than we contemplate — that when

the fortune is made, the friend may be gone beyond mortal reach —

that by the time our purse is full, our fingers may have got an

inveterate habit of drawing its strings.

When Robert reached his mother and sister, he found that they

had been proceeding, firmly and bravely, with all the matters in

hand. They had chosen the father’s grave under the shadows of

St. Magnus. It seemed to Mrs. Sinclair a kindlier

resting-place than the bleak upland graveyard at Quodda would have

been. “There are trees here,” she said to Olive, looking

dreamily at those growing round the ruins of the earl’s palace and

the bishop’s house, and thinking of the ancient avenue in Stockley

church, down which she had walked on her wedding morning. They

had bought their simple and scant stock of mourning, and were

already making it with their own hands.

“You should not have allowed mother to do such a thing,

Olive,” Robert said almost angrily. “She is not taking much

heed to anything just now, but everybody will think us most cruel

and regardless to permit it.”

Olive looked up, surprised. “I don’t think this is the

sort of thing that hurts mother,” she said quietly. She

herself did not feel the more comforted since her brother’s arrival,

as she had looked to be. “Somehow, Robert seems outside the

circle where the sorrow is,” she pondered, “and it seems to me that

it is only those who are inside it that can console each other.”

By-and-by, it might have been noticed that what the three

debated over together, the mother and daughter re-discussed when

alone. Of course, they could not go back to Quodda; they felt

that Robert’s wish was that they should not return to Shetland.

They decided that they would not do so. Robert never asked

them whether they would wish to be near him. They said not a

word about this to each other. They only said that it might be

best if they remained where they were for the present. Living

would not be costly in Kirkwall. It would not be a great

expense to get a few of the old household gods shipped to them from

the more northern island; probably the incoming schoolmaster might

take over the others at a valuation. No definite suggestion

came from Robert. His hints were always negative.

One or two old friends came from Shetland for the funeral,

among them Mr. Ollison from Clegga. They hinted, in their

homely, kind way, that they hoped there was “something for the

widow.” Yes, Robert said, he was thankful to say that his

father had made a certain provision by insurance. (He did not

say how small it had necessarily been.) And he himself was

doing very well, and hoped soon to be doing better. He added

that rather proudly, as if he resented any inquiry; at least, so the

old men thought. They had not been unprepared to render a

little help, if they could have done so in their own neighbourly

fashion. “But it is a right spirit in the young man to be so

independent,” they said to each other. “And it leaves the more

neighbourly help for such widows as have not such children of their

own.” And one of the old gentlemen, who at times made little

investments in stocks and shares, resolved that for the future he

should patronize the office which enjoyed the benefit of Robert’s

services. “There may not be much profit on my business,” said

he, “but it will do the young man good with his employers, when they

see that his old neighbours have such a good opinion of his

principles and abilities.”

Robert returned to London, highly satisfied with himself.

Everybody had told him what a comfort it was to them, for his

mother’s sake, to know of his existence. Well, of course, he

would do something the moment the insurance money was used up; they

must make that last as long as they could, certainly; and by that

time, he would know better “where he was.” Had he not already

made one or two little speculative investments, which, if they

turned out well, would at once realize what would have seemed a

fortune in his eyes three years ago, but which he now characterized

as “a nice little windfall”? (Did he notice how his financial

vision was changing?) It would have been wasting his

“opportunities” had he failed to make those investments. It

would be ruin now to disturb them. No, no; everything would

end well for everybody. He had not taken his mother and Olive

into his confidence, because women know nothing about business.

They ought to feel they could trust him in any case. And from

the first, the world would treat them very differently from what it

would if he was not in existence.

And then he fell into a reverie over a true history he had

once heard. It was the history of a poor artist, the only son

of a gentle but decayed family. His early works had given

great promise, which his later ones did not fulfil. People had

said he worked too much; that he seemed almost to grudge the

necessary appliances for the proper practice of his art, and did not

seek the inspiration and culture he might have got from travel and

from the masterpieces of other minds; that he seemed not to care to

risk rising to the height of his own genius, but was content to toil

on level lines, which brought him safe profit. He had been

called mercenary and sordid. His mother had spoken of him as

if he had sadly disappointed her; it had been discovered that his

sisters did not trouble themselves even to go to see his pictures.

People had pitied the mother and sisters for their withered hopes,

whose fruition might well have lifted them out of their narrow life

of elegant leisure and genteel economies into one of affluence and

influence. But the mother and sisters dropped away, dying not

long after each other. Then it had been noticed that the

brother’s stream of merely salable work grew slack; that he treated

himself to some travelling and to some leisure, the result of which

was a picture which presently made his name. People said that

all this was the beneficial consequence of his entering on his

mother’s little fortune, and one or two got so far as to hint that,

under all the circumstances, she might surely have made some

self-denying arrangements in his favour during her lifetime.

One acquaintance, bolder than the rest, had ventured to ask how much

he had inherited. And the artist had quietly answered, “Only

about one hundred and fifty pounds a year, but the sense of security

and of relief from constant responsibility was the real blessing,”

and he had been judged a poor-spirited creature to have had so

little courage to fight the battle of life on his own account.

And it was only after he was dead, when his one or two bosom friends

were at liberty to speak out, that the general public learned that

from the very first, those leisurely critical women had been

dependent upon him for every morsel of bread they put into their

mouths, and that all he had “inherited” had been the cessation of

the need for supplying their wants, and of the fear lest he might

fail to provide for their future.

“That man was a fool,” decided Robert Sinclair. And

perhaps he was; but there is some folly which is nearly divine, as

there is some seeming wisdom which is altogether devilish. It

was a pity that true story should have had any existence, so that it

could come into Robert Sinclair’s mind just then. He did not

accept it as any guiding for himself. He was not yet base

enough to think that without discretion and reserve on his part,

Mrs. Sinclair and Olive might develop into such chill vampires as

the artist’s family. But the story had its influence

nevertheless. The selfishness of those dead women's lives had

left its pernicious trail behind them. From every life — nay,

from every event in every life — there is distilled an essence, a

medicine or a poison to be the blessing or the bane of the lives or

the events which follow. And while some leave the precious

legacy of their life’s wine poured out in loving service, and others

the strange bequest of their life’s wine turned to vinegar by its

reservation for themselves, there are yet others who drop a strange

and subtle poison, which falling often into the most generous wine

poured out by their contemporaries, chills and impoverishes it, and

even gives it a taint which may prove deadly to some. And if

there be woe to those who have lived for themselves alone, and who

leave the world poorer and not richer for their having been in it,

surely there must be woe, woe — a thousand times woe! — for those

who have so lived that they have made the unselfishness of others

seem to be folly — and have stamped the nobility of

self-forgetfulness as mere madness! For the former only lay

waste the plains of earth, but the latter poison the well-springs of

heaven.

Olive Sinclair went back to Shetland alone, to select and

carry away such remnants of the old home as she and her mother might

venture to keep. The “merchant” at Wallness undertook to

convey these in his cart from Quodda to Lerwick, and to ship them to

Kirkwall in a little vessel he used for his own trading purposes.

He seemed at first to have a curious hesitancy about undertaking the

business, but in the end he named a charge for it which give him a

very fair profit.

“I would not have taken any money at all if it had been from

the old lady and the lassie,” he remarked afterwards, “but there’s

the young fellow to the fore, doing so well everybody says, and hand

in glove with that Brander of St. Ola’s, who is screwing all he can

out of us.”

Olive paid the money. She thought the charge ample, but

she made no observation, though she could not help remembering many

a difficult account which her father had cast, and many a tangled

correspondence which he had unravelled in quite a friendly way, for

the old merchant in bygone days.

Then she said good-bye to all the simple neighbours.

The expressions of their sympathy concerning the sad changes in the

family, and of their congratulation concerning her brother’s future,

were alike received rather silently. She had never been very

popular in Quodda, though everybody had always thought her clever —

far more clever than Robert. “If she had been the boy instead

of the girl she would have done wonders,” they said to each other,

watching the cart as it drove away, with Olive seated behind her

household gods; looking, not back at the villagers, but out upon the

blue sea and the familiar rocks.

“I don’t feel as if I could work for myself,” she thought.

“But I can work for mother. And I suppose that is the way God

always spares one something to give one strength! And if

father thought too well of everybody else, why, there’s only the

more need that I should justify his faith in me.”

And then, in their lodging in Kirkwall, the mother and

daughter began that sort of life whose story is never fully written.

They went out of the temporary furnished lodgings in which Mr.

Sinclair had died, but they did not require to leave the house.

The landlady, a poor widow herself, found them an empty attic,

low-roofed and queer-cornered, for which she would ask but a humble

rent.

“One room will do for us in the mean time,” observed Mrs.

Sinclair. “Robert will not take a holiday to come so far north

very soon, and by then we may have got into something better.”

“One room will do for us in the mean time,” responded Olive,

but she echoed her mother’s speech no further.

At first, while Olive was looking for work, they had to make

some inroad on the insurance money. But that inroad Olive was

determined should not long continue. She got a little daily

teaching, which brought in a few weekly shillings, barely sufficient

to pay for their food. Then she got an evening engagement to

keep a tradesman’s ledgers; this brought in a monthly stipend which

would just meet the rent. Early in the morning, late at night,

and in the intervals between her teaching and her book-keeping, she

toiled at knitting and at white seam. The gains of such

labours were indeed infinitesimal, but they must not be despised,

because they were needed. She found out what economy means

when it has to be exercised, not in cash but in kind. At

Quodda schoolhouse, despite the chronic scarcity of money, there had

always been a certain humble affluence; nobody had had to study how

much they could afford to eat, or whether they might put another

peat on the fire. But now she knew where to draw a line far

within the limit of her healthy young appetite, and she learned how

to make up a peat fire, not so as to get the most warmth from it,

but so as to make it last the longest.

Yet it is only when we get down to these barren places of

life that we find how rich their soil really is, if only it be

properly developed. Olive began to discover that the midnight

moonlight and the ruddy dawn have a secret of their own, which they

keep only for those eyes which rest on their beauty a while, when

hard work is over, or ere hard work begins. She began to feel

as if she had private rights in the grand old cathedral on which her

little window looked.

“What should we do without St. Magnus, mother?” she would ask

cheerily. “How good it was of all those unknown men in the

dark ages to rear its beauty for our delight! And I believe

they did it all the better, that I don’t suppose they thought much

of posterity, but rather of the worship of God, and of doing a good

day’s work for those they loved.”

Olive found, too, that when one gets down on a level with the

poorest, so that they trust one with the real secrets of their life,

one finds that there is a good deal of Spartan endurance and of

quiet self-sacrifice still going forward in the world.

In after years Olive Sinclair did not find those days of

strain and stress at all bad to remember. She used to say

then, that she believed by the time she was an old woman she would

be chiefly interesting on account of what she could tell of that

period.

But then memory, with its curious alchemy for extracting

pleasure from pain, always rejects pain from which pleasure cannot

be extracted. The true suffering of those hard days was that,

during their course, Olive felt as if she could plant no cheerful

hope in any “after years,” could foresee nothing but one long course

of lonely, ill-requited, unremitting toil, uncheered by sympathy or

appreciation. There was no possibility of saving, it was as

much as they could do to pay their way, scanty as were their needs;

a few evil days would plunge them at once in debt — either to Robert

or to somebody —and Olive soon began to feel that it would be almost

more galling to accept aid even for her mother from him than from

strangers; and to think, too, that such a feeling was very

unnatural, and that she must be very wicked to indulge in it.

And yet why? Must there not ever be a deadly bitterness in

taking alms from those whose justice would have saved us from need

for them? As for any ambitions of her own, even the laudable

one of providing for her own future, for the helpless old age that

must come at last after the longest life of toil, Olive soon

realized that she must harbour none. “Perhaps Robert will keep

me then out of charity,” she thought, still not without some

bitterness, “and perhaps he will have a wife who will look askance

at me for needing help, and will give me an old dress and a moral

lecture.” And Olive was right enough in her keen judgment of

the way of the world, though she blamed herself for the edge on her

words. For with those who think that to be lucky and rich is

in itself to be meritorious, to be poor from whatever cause or

course of events is to be disgraceful; he who, like Jack Homer, —

|

Puts in his thumb and pulls out a plum,

And cries, “What a good boy am I!” |

is sure to agree with the poet’s “new style Northern Farmer,”―

That the poor in a loomp is bad.

At other times, Olive would look bravely forward to the very

workhouse itself. “If one has to go there after one has done

one’s very best, one does not need to blush for one’s self, but for

the world,” she reflected. These sombre meditations were

reserved for herself alone, for her mother she had only bright

announcements of her latest triumph in the way of earning or

sparing.

Letters reached them from Tom Ollison oftener than from

Robert Sinclair. Tom had written a frank and friendly letter

in response to the telegram which had intrusted him with news of the

father’s death, and the correspondence had continued since.

His epistles were the one breeze from an active, prospering outer

life, which stirred the two women’s monotonous days. Mrs.

Sinclair rejoiced in the coming of those letters, because they gave

her some assurance of her son's welfare, though when Tom’s allusions

to Robert seemed rather curt and guarded, she often feared lest Tom

had seen that he was looking ill or overworked, and was keeping

something back. And so in truth Tom was, but it was not what

she dreaded. Little as young Ollison knew how it really was

with Mrs. Sinclair and her daughter, he felt an instinctive

reluctance to tell them of Robert’s social progresses; of the dinner

parties he so constantly attended, where his dress and appointments

were of the most irreproachable; of the little suppers he gave among

the young brokers and their more youthful clients, foolish youths of

fashion who were fain to hope to meet their extravagances by

dabbling a little in speculation, and of whom therefore “something

might be made.” Tom had been asked to several of these little

suppers, and had gone — once.

Probably, despite these seeming extravagances, Robert

Sinclair’s expenditure was not large, it was only made exclusively

for what in his eyes was his own benefit. Tom could not

understand Robert. His habits seemed steady, he drank little,

he held somewhat aloof from the fast talk of the men whom yet he

gathered about him — perhaps gaining weight with them by so doing.

He made an outward profession of religion. But all his being

was absorbed in one thought, that of “getting on.” The

scramble seemed but to grow fiercer, the nearer he got to the goal

of fortune; but then, alas! fortune has no goal — it ever recedes,

often only to vanish in thin air at last.

Tom said to Robert more than once, concerning his thoughts,

his ways, and his friends, were these true, were those quite

upright, were the friends worthy? Robert did not say much in

self defence. He only persisted in the thoughts and the ways,

made more friends of the same sort, and saw the less of Tom.

Life is full of such separations.

Olive marked her mother’s rapidly ageing face. She

noted that her mother spoke less than of old. She would sit in

silence for hours now, and her loving manner towards her daughter

changed to one of absolutely supplicating clinging. It seemed

to Olive sometimes as if her mother was actually asking her pardon

for still loving the son, who showed so little love in return.

CHAPTER XIV.

A SECRET HISTORY.

DURING one of the

conversations which Robert and Tom had together, soon after the

return of the former from the north, young Sinclair said, rather

suddenly, and apropos of nothing which had gone before, — “Tom, do

you know anything particular about your Mr. Sandison?”

Tom Ollison looked up at him with a quick, puzzled glance.

The question seemed to have a strangely familiar ring about it — as

if he had heard it before — an experience which we have all of us

known, and which has given rise to many elaborate theories

concerning the action of the dual brain, and to more startling ones

about pre-existence. Probably such experiences are generally

to be attributed to nothing more than a sudden quickening, by some

new combination of circumstance, of some old line of thought and

feeling, and our memory is not of the word or action which seems to

stir it, but of a recurring mood of our own. At least, Tom

Ollison quickly realized that it was so in the present instance.

A minute’s reflection convinced him that what he really remembered

was his own feeling of conjecture and bewilderment when Mr. Sandison

himself had asked, — “Tom, did your father ever tell you anything

about me?” And just as he had answered then, “No, sir, except

that he told me what great friends you had always been,” so he

loyally answered now, — “No, Robert — except that he is very much

better than his words, and I have an idea that, in this world, that

is very ‘particular,’ and indeed ‘peculiar’!”

“Ah,” said Robert, and shook his head, going on mysteriously,

“I suppose he does not like it spoken about. Perhaps some

rebellion against his destiny accounts for his atheism.”

Tom did not ask what “it” was. He always bitterly

repented of having confided Grace’s assertion to Robert. It

was not so much that he yet doubted its truth, in the bald,

materialistic sense of a fact. But since those early days he

had himself been down into the depths — into depths from which he

felt he could never have risen, but for a clinging, childlike faith

that God was with him even there, and had hold of him even in the

dark, and that God knew and believed in Tom Ollison, while Tom

Ollison could not know or believe in God! And suppose Tom

Ollison had been still in those depths, would God have grown tired

of him and let him drop? Perish the idea! Then, too, in

rising out of those depths, Tom had not scrambled back to the brink

whence he had fallen; that would be no salvation from any Slough of

Despond. God had brought him out, like the Psalmist of old,

into “a wealthy place,” upon the richer soil nearer the Celestial

City. Tom could say his creed again, now, firmly and joyfully

— feeling, indeed, that he had never believed it before; but then it

did not mean to him quite the same which it had meant in days when

he had thought he believed it, and would have argued stoutly in

defence of its very words. (The alphabet is not the same to

us, after we have learned to read, as it is when we are learning its

letters.) Atheism was not now to him the frightful mystery

which it is to those who seem to fear that God’s existence may be

endangered if it should ever be denied by the majority of his

children, who can only live and move and have their being in him, as

he in them. He now saw man as related to God, in the deepest

part of his nature, as he is in his bodily existence to air and

earth and fire and water; and he saw that by them man breathed and

fed, and was warmed and refreshed, before he could articulate their

names, and even if he was so blind or so idiotic that he could not

see or comprehend them. Tom could recognize atheism and

infidelity as the spiritual iconoclasts of the world, even as

Judaism and Mahomedanism had been its idol-breakers, emptying

shrines of maimed or distorted images, to make way for the living

form of the God-man. That memory of his own good father

tenderly tending him through the foolish rage of his delirium had

stood Tom in good stead again and again. God could never

disown his children who did not love him, because they did not know

him, or could not see his face. His other children could only

love him the more for such pain and such patience. And as for

Peter Sandison, was there not perpetual prayer in those pathetic

eyes of his? — and for what were they forever seeking, if not for

God himself?

Tom Ollison was glad of one thing: that even in those early

days, wherein one is so tempted to repose confidences in those with

whom we are already familiar concerning those who are still

strangers, he had never yielded to the temptation to tell Robert of

the sealed leaves of the Sandison Bible, or of the strange

inoccupancy and desertion of the best rooms of the Sandison house.

The latter fact did not seem to have struck Robert, whose brief

visits had been quite naturally passed in the dining-room and in his

friend’s own apartment.

Robert observed that Tom allowed his last remark to pass

without response, and he drew an unfavourable inference from it.

Probably Tom was getting “queer” himself. Well, there was

really so much free thought among the members of the learned

societies in whose libraries Tom’s life-work lay, that perhaps such

a reputation might be good for him rather than bad; but still it was

a pity, considering how Tom had been brought up.

However, Robert said nothing on this subject. Perhaps

he was all the more eager to proceed with his news, because Tom

manifested so little curiosity.

“Well, of course, you know that Mr. Sandison came from

Shetland,” he narrated, “and perhaps, though he was such a friend of

your father’s, that is all you do know. It is wonderful how

much we all take for granted, especially concerning our elders.

But when I was in the north this time, the old men who came to my

father’s funeral, in their natural desire to know all about things

in London, let fall expressions which let me know that there was a

mystery somewhere, and once I had got as far as that, be sure I lost

no time in getting as far as I could go. So you really have

not the least idea that Peter Sandison is no Shetlander, except by

repute, and that he has no better right to the name he bears?”

“I only know that he and my father were friends from their

earliest years, and that one of my first memories is of hearing his

name mentioned with respect at Clegga.” Tom spoke with a

coldness quite foreign to his usual manner. He wished to check

Robert’s communications, yet he would not absolutely silence him,

lest it should seem as if he feared what might be said.

Robert went on. “They say he was brought to the island

in a ship, when he was a baby, and was given in charge of the old

couple, who provided him with a name and a starting-point in life.

One of the old men said that Peter Sandison had been a very dashing,

eager sort of boy, but that a great change came over him after his

foster parents’ death. It was thought that then he first

discovered the secret of his birth.”

Tom said nothing. He was silently adjusting this new

fact beside many an old one. Robert went on.

“Then they say there was a rumour that he had another

terrible come-down in London, years after. They had only a

vague story of that, without names or dates, gathered from the

reports in home letters of other Shetlanders in the metropolis.

They said that he had fallen in love with a young lady, who was

supposed to be rather above him in circumstances; not that she had

any money of her own, they said, but she was the daughter of some

government pensioner, and she made poor Peter understand that it

wouldn’t be nice on his part to take her from her genteel home, and

turn her into a wife and a general servant all at once. I dare

say she made him believe that, for her own part, she was ready with

any angelic sacrifice for his sake,” laughed Robert, with the manner

of one who knows the wiles of the sex — the easy confidence of the

serpent-charmer, who will not be bitten.

“Well?“ said Tom Ollison, with a sharp note of interrogation.

Robert Sinclair’s mirth jarred and fretted him. As he would

tell this story, let him hasten to its end.

“Well,” echoed Robert quite complacently, “that happened

which might have been expected to happen. While Peter Sandison

was toiling and moiling among his books and catalogues, laying

shilling to shilling, and pound to pound, a certain smart fellow,

who knew both of the courting couple, dashed into a bold

speculation, made his fortune, and carried off the lady’s heart.

It was only a modern version of the old ballad, don’t you know, —

|

Let him take who has the power,

And let him keep who can! |

They say she made excuses that she was beginning to have doubts

about Peter ― she thought that some

of his views were queer, and that perhaps it was risky to trust

herself to a man with so doubtful an origin. But of course one

can see what all that was worth. Well, I don’t blame her.

It is easy to blame people. But we must each do the best for

ourselves, and a woman’s marriage is always her best or her worst

bit of business. She hasn’t markets every week.”

What could Tom Ollison say? All the true romance of his

pure young heart was up in arms against such a defilement and

desecration of life’s sweetest sanctities. And yet by this

time he fully realized that to argue over them with Robert Sinclair

would be worse than useless, would only lead to further desecration,

like a struggle in a church with one who has insolently spat on its

altar steps. And every nerve of his warm, true nature was

tingling in sympathy with Peter Sandison. Atheist, was he?

If so, then whose was the root of the blame? The beloved

disciple had pertinently asked, “He that loveth not his brother whom

he hath seen, how can he love God, whom he hath not seen?” Was

it a grievous perverting of Scripture for Tom to feel that in the

very spirit of that question another might be asked, “He who finds

no ground for faith in his brother whom he hath seen, how can he

have faith in God whom he hath not seen?”

Oh! how glad he was to think that at the very beginning he

had not been tempted to swerve from his allegiance to his father’s

friend, even for that bright, peaceful Stockley life which Robert

had held so lightly! But while he pondered, Robert went on

again.

“The old fogies told me all this news quite simply — just as

they knew it. They could supply no dates, no margin narrower

than a decade. Nor did they know the names of this false lady

and her successful lover. The beauty of it was that I saw

directly that I could supply both. They only gave the other

halt to a half story I half knew before. But as they never

dreamed of that I got off without any suspicious questionings.

Does nothing strike you, Tom? Don’t you see through this?”

“No,” said Tom stubbornly; “I only hear all you have told

me.”

“But don’t you feel a clue? You must surely have heard

something on which this throws a light? Do you know, I should

not have been a bit surprised if you had taken the wind out of my

sails by telling me you knew all about this long ago. Do you

mean to say you cannot give a guess as to the identity of the

nameless parties in my tale? Try.”

“I am not going to try,” said Tom. “I shall know when I

am told. Guessing on such subjects is an unjustifiable

throwing about of mud, and then some may stick on quite innocent

people.”

Robert was silent for a few minutes, perhaps only because he

was lighting a cigar. Probably it would have been quite

impossible for him to trace the line of thought which carried him on

to his next remark.

“Have you heard anything of Kirsty Mail since she left the

Branders’ service?”

For Tom had never told him of his chance encounter with her

at the railway refreshment buffet on the day when Robert went to the

north. Tom could scarcely have told whether his silence on the

subject had been instinctive or intentional. He told him the

facts of the case now, as briefly and baldly as possible.

Robert puffed his cigar for a minute. “That girl will

come to no good,” he decided. “She was one of those who will

have their pleasure and their leisure at any cost. If I had

told all I knew she would have been out of the Branders’ house long

before she was.”

“If you thought she was going wrong you should have spoken to

somebody,” said Tom. “Even Mrs. Brander herself,” he added

rather faint-heartedly, “though she might have discharged her, might

have kept an eye on her, or have interested those in her who would

have done so.”

Robert shook his head. “Not likely,” he observed

easily. “And besides, it does not do to mix one’s self up with

these matters. It isn’t understood. If one does so,

people think there is something at the bottom of it. And

before one knows where one is there is a mysterious rumour floating

about one. And it will turn up some day to do one damage, when

and where one least expects it.”

“Well, good bye now, Robert,” said Tom quite suddenly, unable

longer to endure his companion’s mental and moral atmosphere.

It had never before occurred to him that probably the self-condemned

accusers of the sinful woman in the New Testament had barely crept

away from the presence of her and her merciful Master, before they

began to whisper innuendoes against him whom they had left speaking

to her with kindly courtesy. It is scarcely in early youth

that we discover that society, like the air, is filled with floating

matter, ready to settle everywhere, and to convert wholesomeness

into poison. So while we hermetically seal the food we wish to

preserve, let us consider the wisdom which directed that the right

hand should not know what the left hand did, and which was feign to

seal every good deed with secrecy — “ See thou tell no man.”

That very afternoon Tom availed himself of a leisure hour to

go to the railway station, in the hope of seeing Kirsty, and of

making some appeal to her better feelings and good sense.

He found another “young lady” at the refreshment buffet.

This one had black hair and bold black eyes, with which she stared

at him for a full minute before she answered his quiet inquiry after

“Miss Mail.”

“Miss Mail?” she echoed, “Miss Chrissie?” with a mocking

emphasis on the abbreviated name. “Oh! we don’t know anything

of her here, and don’t want to. She’s gone.”

Tom felt his face hot under the girl’s cruel glance.

“She had a cousin, barmaid at the Royal Stag,” she went on.

“That one took to robbery — at least a man she knew did, a man

that had run away from Edinburgh with her, and she was put into the

dock with him, only they let her off. I don’t say your Miss

Chrissie did anything in that style, but she lost her place here

through her carryings on, and when the man got his sentence I

suppose the two girls went off together. Nobody has heard of

‘em since.”

Tom turned and went back to Penman Row. By that time it

was twilight; and it seemed to him that at every corner he saw a

face and heard a laugh which might have belonged to Kirsty Mail.

CHAPTER XV.

IN THE DEAD OF THE NIGHT.

AND so for years,

while Olive Sinclair toiled and spared in the old attic in Kirkwall,

and while her mother waited and prayed and sealed her yearning

maternal love in a gentle silence, the life of the two young men in

London advanced steadily up the grooves which each had found for

himself. Tom Ollison saw his father several times, but not by

his going to Shetland, or by the old gentleman coming up to London;

they agreed to break the long journey for each other by meeting at

Edinburgh, which spared Tom the sea voyage for which he had little

leisure, and saved the father from travelling on “those railway

lines” which, despite their

smoothness, he mistrusted far more than the roughest waves of his

own North Sea. Once, indeed, Tom went to Shetland. He

did not stop in Kirkwall, except on his return journey while the

vessel in which he journeyed lay in dock to take in passengers and

cattle. Mrs. Sinclair and Olive came down to the shore to see

him, and to exchange a few friendly words during the brief interval.

It pained Tom to see how the schoolmaster’s widow had become quite

an old lady, with silvery hair smoothed beneath her black bonnet,

and with pain and patience writ large on her sweet and mobile face.

But what an interesting woman Olive had grown! rather too slight,

perhaps, but gaunt no longer. What fine lines had come out in

her countenance! What a wonderful light there was in her eyes!

Tom only wished he could have prolonged his stay. Yet though

there was nothing in the neat black garments of mother and daughter

to rouse in his masculine unconsciousness any suspicion of the hard

life of struggle and privation which they were living, somehow he

felt that he would not have much cared to enlarge on Robert’s career

to them, and that perhaps it was well he was limited to more general

information as to the wellbeing and prosperity of the son and

brother. But now that he had seen Olive Sinclair again, he

felt he must see more of her, and to his dismay he found that

henceforth her friendly letters were no longer a welcome, temperate

pleasure, but a longed-for, passionate delight.

In those years, Tom’s life enlarged greatly in many ways.

He went abroad more than once, deputed by Mr. Sandison, to do work

which had been offered to that well-known and respected, “though

eccentric,” bookseller and bookhunter. He lived a real life in

those foreign cities, working amid their workers, and making friends

among them. He was more than once at the great book fair at

Leipzig. But he always came back, with an unspoiled heart,

into the strange, subdued life in Penman Row, and the hearty, homely

sociality of the homely folk among whom he worshipped.

Tom paid occasional visits to the Branders’, though the

intervals between such visits grew ever longer. He could ill

brook to bear the ignorant contempt with which the whole family

regarded the simple peasantry of his native island, from whom too,

he knew by his father’s letters, every penny was being extorted and

every right gradually withdrawn, and to whom were extended none of

the amenities which once made feudal power a possible form of

friendly protection.

There were times when it almost dawned on Etta Brander’s

darkened perceptions, that about this young man with his “Quixotic

ideas” there was something finer than about her father and Robert

Sinclair. She even got so far once as to think to herself that

the world might be a pleasanter world if everybody was like him.

But then it was no use to dream of what “might be;” it was clear

that the world was full of quite another sort of people, and “it was

of no use to be singular.” She was inclined to pity Tom a

little for the long hours which his work seemed to absorb, and for

the nature of his recreations, the long country rambles or boatings

on the river, solitary, or with some companion as hard-working as

himself — the occasional game of cricket or quoits during his

Saturday afternoons at his favourite Stockley. How different

all these were from the gay, exciting diversions — the dances, the

polo, the operas, and the pigeon-shooting matches, without which she

felt she could not live! And yet young Mr. Ollison never

looked bored, as she constantly felt. Why, she even wearied so

utterly of the monotony of travelling in Switzerland, that she got

her father to push on to the southern gaming tables that she might

snatch the feverish delights of rouge-et-noir. Afterwards she

always said that she did not wonder that gentlemen enjoyed

speculation.

Mrs. Brander did not make much demur over the transformation

her daughter worked in the family sphere. She herself had been

brought up in the straightest old fashion not to dance, not to go to

a play, not to read a novel. Some forgotten ancestor of hers

had rejected these things, perhaps in the days of public Maypoles,

of the libertine Wycherley and of the notorious Mrs. Aphra Behn.

For generations afterwards the family had walked blindly in that

ancestor’s footsteps, doing right (as far as it was right) wrongly,

since they did it not on any principle, but because it was “the

custom” of the most select section of the “respectable” society in

which they had been content to move in those days. But now

things were changed. Mrs. Brander’s new friends were

“fashionable,” and had other standards. So for these, she

quietly deserted her own. She did not honestly change them, as

anybody may change any custom, even in sheer loyalty to the very

principle which may underlie it. When she alluded to her

changed social tactics, she did not say, “Things are changed,” or

“My views have changed.” She only sighed, “The times are

changed,” “People think differently nowadays.”

She little knew that it was words of hers which put an end,

finally, to Tom Ollison’s few and far-between visits to Ormolu

Square.

On that evening, she had first descanted long on the graces

and accomplishments of Captain Carson, whom Tom had met there again

and again. Long before this, Tom had known that the captain

was the heir of the good squire of Stockley, the unworthy heir, to

whose advent into place, the Blacks, and all the other old tenants,

looked forward with dislike, and even terror; since the young man’s

character was of a kind calculated to check and destroy all the good

influence of proceeding generations, while it had already betrayed

himself into the power of eager, mercenary men like Mr. Brander, who

would put every pressure on their weak and self-indulgent tool to

force him to extort from his ancestral acres more rapid and showy

gains than golden harvests and rosy orchards, and a race of loyal

and honest men. Already strangers had been seen about

Stockley, who dropped suspicious hints concerning a big new

public-house, a possible distillery, and plenty of speculative

building, as facts looming in that future which was only held back

by the frail life of one ageing man. Tom would have been ready

to deduct a good deal of the evil report of the Stockleyites

concerning young Carson, as due to their fond clinging to a happy

old régime, and their

natural shrinking from a new and doubtful one. But Tom had not

been left to form his opinion of the man from these alone. At

that solitary supper of Robert’s at which Tom had put in appearance,

he had heard Carson tell a foul story and crack a vile joke.

His name had figured disreputably once or twice in the daily papers,

and was seldom omitted from the suggestive chat of society journals.

Mr. Brander did not disguise his own judgment of the man, especially

of late, since the interests of his succession had been mortgaged,

as he said, “to their very hilt.” Nay, Mrs. Brander herself

saw no necessity for disguising her knowledge that “the poor dear

captain had been very wild,” while she went on to say “what perfect

manners he had, and how sweet his disposition seemed, and how she

was quite sure his heart was thoroughly good at bottom.”

Tom Ollison could not help thinking what different measure

was meted to Captain Carson and to Kirsty Mail. But he knew

that to draw any such parallel would seem to Mrs. Brander like

insanity, and would be regarded by her as a personal insult.

So, wishing his words to carry some conviction, rather than to

merely relieve his own feelings, he only said,—“The more attractive

such men as Captain Carson may be, the more pestilential are they in

society.”

“Oh, now you are uncharitable!” cried the lady; “we must

always hope for the best. I don’t believe the captain would

harm a fly. There are so many temptations for men of rank and

wealth that we must not judge them hardly. I believe the

captain really aspires after better things. He told me that he

finds it a real treat to go sometimes to St. Bevis’s Church, it is

so sweet to hear the trained choir singing in the dim, religious

light. There is always hope for a man who is religiously

disposed.” There she paused for a while and then asked, “Is it

true, as Robert says, that your poor Mr. Sandison is an atheist?”

Tom felt his face flush. Had his sacred, though rash

confidence been thus bandied about?

“Madam,” he said, “I have never heard Mr. Sandison name God.”

“Ah,” sighed the lady, “I feared and foresaw that it would be

so. And once it was so different. He thought and spoke a

great deal of sacred things. And most reverently, too — or, of

course, I should not have allowed it. Only he permitted

himself to think too deeply, and to venture to think in new ways.

I foresaw how it would end.” She sighed again sentimentally,

and then bending over her crewel work, said, in a lower voice, “He

and I were once rather friendly. Poor dear Peter!

Without doubt, he has mentioned that to you, when he has heard of

your visits here.”

“He never did so, madam,” Tom was glad to be able to reply.

Tom had been unable to suppress sundry conjectures which Robert's

hints had aroused, but he had never given them voice. “He

never mentioned that, madam. But when I said I had never heard

him name God, I was going on to say, that had I gone into his house

a pagan, I am sure I should have asked what God my master served,

whose service made him so tender and true in his dealings with all

men. Perhaps he has learned, maybe too bitterly, to trust

words less and deeds more.”

For many a little secret had Tom discovered to his master's

credit, as, for instance, he had come across the hotel bill for that

Christmas dinner for the Shands which had aroused Grace's ire

(though even note could not guess that the festivity had been first

planned in kindliness to himself); and he had discovered that the

wheel and the Shetland prints had been bought to give the old attic

a homely look for his eye. And was be going to discuss the

mute agonies of the noble soul which haunted Peter Sandison's

pathetic eyes, with this shallow dame, who fancied she had faith

because she did not know that faith is of the heart and the life,

and not of the lip? No, never. And from that day he

never returned to Ormolu Square.

Etta Brander and Robert Sinclair had been long openly

engaged, and their approaching marriage was even being discussed by

this time. Everybody regarded Robert as one of

“the most rising young men in the

City.” He had made one or two

very lucky hits. But life was a hard and constant strain upon

him, being, in one of its aspects, a gambling game, in which at any

time much of the luck might set against him; on the other, a

perpetual struggle to keep his resources up to the ever-rising

water-mark of his ambitions, and the needs which grew out of them.

People told Etta that she was “a

very fortunate girl,” and Etta grew

quite satisfied that to consult high-art authorities on the

furniture of one's future home, and to invent

æsthetic novelties for one's

trousseau, was vastly better than any idyllic love in a cottage,

though somehow all the poets and the painters seemed to find the

latter the better subject whereon to exercise their gifts, and she

found it very nice to buy pretty pictures of people whom in real

life she would have only pitied and patronized. For her, there

were few lovers' confidences in the gloaming, few lovers' roamings

in forest or on seashore, but she saw quite as much of Robert as she

wished at the balls and dinner parties to which they were both

invited. Etta's own ambitions were growing daily, and as she

knew that “business” meant means to gratify them, she never grudged

to find “business” her very successful rival.

“Etta,” said one of her friends to her once, “at one time, I

half thought you were in love with that naughty Captain Carson.”

“Perhaps I was,” Etta calmly admitted, “I think I liked him

better than I ever liked any other man.”

“And yet――” said the friend

significantly.

“And yet I shall marry Robert Sinclair,” Etta answered; “that

is quite a different thing.”

Etta had heard little — and asked nothing —about the mother

and sister in the far north. “They were living quietly in a

cathedral town there,” she said. That had a pretty and an

aristocratic sound. To do her justice, she knew nothing more.

Possibly Robert had encouraged her dislike to the thought of ever

visiting those remote islands. Mr. Brander himself had gone to

his northern estate several times, and had always returned in a bad

temper, saying “he would be glad to wash his hands of the whole

concern; it was the worst investment he had ever made; he might as

well have acted like an old woman, and put the money into consols!”

It was just before Robert and Etta were married, that one

evening, as Mr. Sandison and Tom sat together at supper in the

dining-room at Penman Row, Grace came in and announced, in her very

sourest manner, "that somebody had been a-calling for Mr. Ollison.

But when the boy fetched me to her, I told her you weren't in, and I

didn’t know when you would be in.” Seeing Tom’s reproachful

expression Grace went on, “Well, you weren‘t in at the minute,

though I knew you’d be home directly. But she wasn’t one of

the sort to come about a decent house. I’ll warrant she’ll

come again, sharp enough, so I thought I’d let you know first, and

you can tell me what is to be said to her.”

“Who was she?” Tom asked. Old Grace could understand

such questions by her eyes, though they did not reach her ears.

“She was a bad one, whoever she was,” answered the old woman.

“Dressed in tawdry finery, with a fluff of yellow hair and blue

eyes, a-crying, and all in a fuss. Coming begging, of course,

and making you believe she meant to reform!

“Kirsty Mail at last!” exclaimed Tom, rising from his chair.

“And to think she has been sent away like this!”

Grace could see the young man’s agitation. She laughed

in her dismal, cavernous way. “Oh, that sort don’t kill

themselves often,” she croaked. “And when so, maybe it’s the

best thing they can do. I gave her a good piece of my mind.”

“Woman!” said Mr. Sandison, “if there is no mercy in your

heart, is there no reflection in your bosom which should teach you

words and thoughts far different from these? If not, how can

God himself help you?”

There was something awful in the master’s tone. It sent

a strange thrill through Tom. It was neither loud nor angry,

only unutterably piercing and sad. The words could not have

reached Grace’s deaf ears, scarcely even the voice, yet for the

first time since Tom had known her, she quailed visibly. Her

sallow face blanched, and as it did so, a weird youthfulness swept

over it, and a wild light as of fear and defiance flashed in her

black eyes. But they could not meet her master’s.

Without another word she sidled out of the room, as if from the

presence of something which she feared to face, yet on which she

dared not turn her back.

Mr. Sandison rose from his seat. “That poor soul,

driven away from the door,” he said, in low solemn accents (he knew

all that Tom knew of the story of Kirsty Mail), “where is she now?

and what will be her thoughts of God to-night?”

“Wherever she is, God is with her,” said Tom quietly, “and

whatever are her thoughts of him, he has only loving thoughts of

her. And surely,” he added, with a slow, gentle reverence, “he

will marvel, if, in a world where he sent his own son in his own

likeness, there are those who will mistake such as Grace Allan for

any representative of him.”

Once again, Mr. Sandison threw Tom a quick, bright glance,

like one of sudden and happy recognition. He did not say

another word, but walked straight from the parlour upstairs, and

into his own room.

Tom did not linger long behind. It struck him that he

could no longer say he had never heard Mr. Sandison name God, and

that he had now named him, not as any unbeliever might, but from the

standpoint of one who entered into his yearning love, defeated by

human hardness, and who suffered, as a son might, to see his father

misrepresented and misunderstood in his own family. And it

struck Tom, too, that, for the moment, it had not startled him to

hear Mr. Sandison speak so, despite the belief he had held for so

many years concerning him, and the silence which had confirmed it.

The three bedrooms of the establishment were all on the same

highest landing, above the other flats of closed-up rooms.

Grace was in her room already, but all there was darkness and

silence. Mr. Sandison was in his; he believed he had closed

the door behind him, but the latch had slipped, and it stood

slightly ajar. As Tom passed, he saw the master of the house

kneeling by his low bedside, his face buried in his hands.

Tom crept by, with a blush on his face for his unintentional

intrusion.

In the dead of the night he awoke suddenly. It seemed

to him that somebody had passed down-stairs. Yet the sound

which had penetrated his slumbers was scarcely that of a footstep,

rather of a hand drawn stealthily along the outer wall, groping in

the darkness.

CHAPTER XVI.

THE SECRET IN THE BIBLE.

TOM

OLLISON’S half-dreamy

conjecture had been right. In the middle of the night Grace

Allan, who had never been to bed, left her room and stole

down-stairs to the parlour.

There was something aroused in her which must be satisfied in

one way or another, at any cost. What did Mr. Sandison know

about her? Did he know anything? And if so, how had he

learned it? And was there not something to know about

himself? What lay between the sealed fly-leaves of the

family Bible?

She determined to risk anything to find that out. She

did not hope to do so and to escape detection in so doing.

(She had already tried numberless times to do that.) No; she

would be at the secret anyhow. After she once knew it,

whatever it might be, probably Mr. Sandison would think thrice

before he put her out of the house for her inquisitiveness, or

before he again “cast up“ against her what “was none of his

business,” what he had no right to know, and that, after she had

lived “so respectable” for nigh fifty years.

It was odd that deaf Grace, who had not heard one of her

master’s words, had made out a bitter reproach where Tom Ollison had

heard only a pathetic appeal.

She went down into the parlour, still groping in the dark,

found a candlestick, and got a light.

Then she took the big Bible from its shelf and laid it on the

table.

But somehow, a little hesitation seized her, as if she could

not hasten to do what could never be undone. So she left the

Bible lying closed, while she cleared the supper table and tidied

the apartment, as she usually did before going up-stairs to bed, but

had failed to do on the preceding evening.

All this was only the delay of nervous irresolution, it meant

no relenting change of mood.

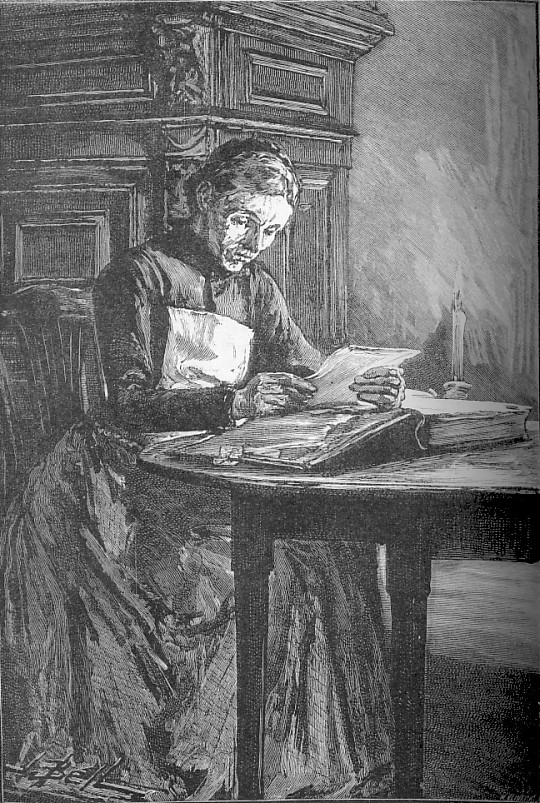

So, at last, she drew a chair to the table, and set down the

candle beside her, a little spot of light in the surrounding gloom.

Then she opened the Bible, and fumbled at the sealed leaves with

fingers which trembled strangely.

How little do any of us know when and how we shall take the

judgment-book of our own lives into our hands, and opening it,

perhaps in pride and malice, to read the sentence of another, shall

find instead the simple home-thrust, —

“Thou art the man!”

One seal was broken! So cleanly too that she almost

thought it might be mended unnoticeably, and her heart beat faster

with the thought that if she had such good luck with another, she

might so repair the damage as to be possessed of “the truth“ about

her master, without his knowing where she had found it. But

that was not to be. The second seal smashed and fell in

fragments. Yet she scarcely noticed that disappointment in the

fact that the leaves were now so widely parted that sundry papers

fell from them into her lap, and that she could also distinctly see

between them.

They were both entirely blank.

The secret then was among those loose papers. Eagerly

she turned them over — one or two old letters, and a few dim and

yellow cuttings from prints.

Then came a low, terrible, incredulous cry. For one

moment the papers fell from her hands, but in another she was wildly

seeking some clue for their arrangement so as to get the whole

narrative in its dreaded sequence. Each scrap of paper had a

date written upon it, and how instinctively she seemed to know which

was the earliest!

This was a bit of old newspaper, thin in texture and weak in

type, suggestive of old-fashioned provincial journalism. It

was only a short paragraph, and it ran — “Last week, one evening, a

Buchanness fisherman found a baby lying at the foot of the Duller

rocks. The child, a boy, had evidently been exposed for some

time, as it was in a very suffering condition. The fisherman

was directed to it by its cry, which he mistook at first for that of

a sea-bird. He carried the poor little waif home to his wife,

and, to the credit of their humanity, they have resolved to take

charge of it for the present. There is no clue as to those who

must have so wilfully and cruelly deserted the child. Only a

lad reports that, in the early morning of the day when the baby was

found, he met a strange woman walking very fast in the direction of

Ellon. He did not notice anything about her, except that her

black shawl was fastened by a silver brooch, formed in a plain

hollow circle, which caught his eye through the sun glancing on it

as he passed her. His impression is that she was young and not

tall.”

(There was just such a silver brooch formed in a plain hollow

circle, sticking in the pincushion in Grace Allan’s bedroom.

She had worn it at her throat on the preceding evening.)

This scrap of printed matter had been evidently enclosed in a

letter bearing date two or three years later. As Grace hastily

scanned its contents she found this must have been written by the

Buchanness fisherman to his sister, married and childless, in

Shetland. It set forth that his own wife being dead, and he

resolved on going to Newfoundland, he purposed committing to the

charge of her and her husband the adopted child of whom he had

already written, and whom he was sending to them by trusty hands,

along with certain of his savings, which would assist in its

maintenance until it could “fend for itself.”

This letter was endorsed in Peter Sandison’s handwriting.

“Found among the papers of my adopted parents after their death.

My first discovery of the truth.” And the date was given.

Then came a narrow printed slip with a date not long

subsequent. This was only an advertisement offering reward or

advantage of some kind to any person coming forward able to give any

information whatever which might lead towards the discovery of the

antecedents of a male child, found deserted among the rocks of

Buchanness, on such a day of such a year, and believed to have been

deserted by a woman wearing a black shawl, with a silver circle for

a brooch.

This advertisement had apparently elicited one letter — the

long and rambling letter of an uneducated person. But it was

not too long or too illegible for Grace’s patience.

"It was too long, or too illegible, for Grace's

patience."

It set forth that, years before, the writer, a seafaring man

and a native of Buchanness, having engaged for a voyage from one of

the more southern seaports, had been leisurely journeying towards

his port by easy stages, stopping with sundry relatives on the road;

that he had thus stopped in Ellon; that while there, chancing to

look from his bedroom window at a very early hour in the morning, he

saw a woman go past carrying a baby in her arms; that he took a good

look at her, wondering who she could be, since there was something

in her dress and appearance different from those of the women of

that neighbourhood who were likely to be abroad at such an hour;

that she was short in stature, pale and dark, and wore a black

shawl; that, of course, he thought no more of the incident,

travelled to his port, went his voyage, and never even heard of the

baby deserted among the rocks; that many years after, while making

purchases in the shop of a nautical instrument maker in London, he

had been particularly struck by a woman who appeared to be acting as

a working housekeeper in the establishment, because her face seemed

familiar to him, though he was utterly unable to fix the memory; he

had asked her whether she could help him at all—whether, on her

side, she had the least idea of having ever seen him before, that

she had answered decidedly and sourly, “Certainly not;” that he had

remained unconvinced, and had even asked one of the shop-men what

her name was, and was told she was a Miss Grace Allan, and belonged

to London, and was, said the man, such a perfect porcupine of

propriety, that she had probably construed the seaman’s good-natured

question into an insult; that he had thought no more of the matter;

that it was only afterwards, when returning through Ellon, that in

quite a casual way the remembrance of the woman he had seen in the

road there flashed on his mind, identifying her with the London

house-keeper (whose blank denial of all recollection of him was

therefore quite truthful, since, on the first occasion of his seeing

her, she had not seen him), that being near Buchanness when the

advertisement appeared asking for information concerning the

desertion of the child, he then, for the first time, heard the

story, already forgotten by all but elderly neighbours; that, with

the exception of the black shawl, he could not speak as to what the

woman was wearing whom he saw in Ellon, but that he could swear that

the instrument maker’s housekeeper wore for a brooch a flat silver

circle, because he took special notice of it, thinking such would

not be an unsuitable design for a gift he was at that time about to

make; that he gave all this information for what it was worth, not

seeking reward, which indeed he would not take; that it was nothing

in itself, yet might lead to something; but that he was bound to

say, in conclusion, that the London instrument maker was since dead,

and that his establishment was utterly broken up and scattered.

The only other document was a sheet of foolscap, on which was

set forth a list of the places which Grace Allan had filled, between

her leaving the instrument maker’s and her coming to Peter

Sandison’s. Considering the number of the years in this

interval, this list was not short. For the increasing acerbity

of Grace’s temper and the inconvenience of her deafness had made her

an unwelcome and awkward inmate of the households which she had

entered. She had been indeed a poor old woman, very low down

in the world, and with a very gloomy outlook, when, all

unexpectedly, the offer of the post of Mr. Sandison’s housekeeper

had come to her.

She had believed that she quite saw through her new master’s

acceptance and endurance of her infirmities. He had secrets of

his own, which made him quite content to stand aside from the

ordinary comforts and amenities of life, secrets perhaps which made

it safer for him so to do. From the very first she had asked

herself, sourly, “What could he have hidden in those locked-up

rooms, which nobody ever entered — ay, which she had never entered

yet — after all these years?”

Ah, and she had asked herself also, “What had he got hidden

between the sealed-up leaves of the big Bible?”

As the remembrance of that old wonder and suspicion turned

round and stung her, the loose papers fluttered from her hand to the

floor, leaving in her grasp only that in which they had been folded,

and which she had thought at first was but a blank wrapper.

She saw now that there was writing upon it. There were but a

few words; and how strangely they seemed to dance before her eyes!

What was wrong with them, or with her?

They were in Peter Sandison’s own handwriting, and they were

nothing but a transcript of the texts — “Can a woman forget her

sucking child, that she should not have compassion on the son of her

womb? Yea, they may forget, yet will I not forget thee.”

“When my father and mother forsake me, then the Lord taketh

me up.”

She gathered up the papers and put them back between the

severed leaves. She had no longer any thought of hiding what

she had done. What did that matter now?

She sat there still and silent. The sweet spring dawn

was brightening outside; a silver shaft of light stole softly even

to that gloomy parlour.

How well she remembered that red, red dawn over the eastern

sea, when she had sped along the desolate roads, amid the treeless,

hedgeless fields of dreary Buchan, with her baby at her breast! her

one thought, how to put far from her the shame of it, and, above

all, the burden of it; for there was none to share it with her.

She remembered all her thoughts that day, and all that had gone

before, as one might remember a story that was told one of another.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Once or twice, in the long, long years since, she had vaguely

wondered whether that boy had lived or died. Once, when her

way had been very hard — just before Peter Sandison had crossed her

path — she had half-wondered whether it might not have been well for

her to have struggled for his infancy, if, haply so, he might have

defended her old age. But it was wonderful how seldom she had

ever thought of him at all. The remembrance had never made her

pitiful to one forlorn child, nor merciful to one sinful woman.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Old Grace Allan sat in the pale morning light; but it was not

of past things that she thought. Nay, she thought of nothing.

There was only once more a bitter protest against the penalty she

had to hear. It seemed to her now, that the penalty from which

she had shrunk in her young womanhood had been light indeed, though

it still seemed to her “but natural” that she should have struck a

deadly blow to escape it. And that it should turn up like

this, after all—how hard, how hard, how hard it was! For to

Grace’s narrow mind this was no simple fulfilment of the everlasting

law that, somewhere on some day, sin shall ever find out the sinner,

it seemed to her a special providence, and therefore specially

cruel. Was she, after all, to be condemned as a would be

murderess and a lifelong hypocrite? It was not fair!

Such measure was not meted out to everybody. She would not

bear it! She would escape somewhere, somehow! Futile as

she had just proved such efforts to be, she was ready for them

again. Experience is such a puzzling teacher. When we do

well, and yet fail, she says distinctly, “Try again.” When we

do badly, and fail, we are apt to catch that echo.

Grace had laid her plans well when she was young and vigorous

in mind and body, and they had all come to nothing. Now she

had no plans to lay, nothing to start upon, except the blind

rebellion within her.

She would go away from here; she did not know where she meant

to go. She did not know that she forgot to take anything with

her, even a bonnet or shawl.

She did not notice that she left the Bible lying open on the

table, ready to tell its tale. She knew only her own wild

determination not to meet the eyes of Peter Sandison. She

would have shrunk from them less had her story been new to her son

this day. But he had known it all the time; he had never

looked at her, unknowing of it.

The candle had gone on burning in the wan dawning. It

was at the socket now, and when it flickered and went out, that

roused her to the consciousness that it was now broad daylight.

What was to be done must be done quickly.

She stole from the parlour and crept through the shop.

Then, with chill and trembling hands, she unfastened the front door.

How heavy the bolts and bars seemed! But they were all undone

at last, and the morning air blew freshly on her withered face.

She closed the door behind her very gently, lest any noise should

penetrate through the house and rouse the sleepers in the far-off

bedrooms. And then she went down the street, moving slowly,

close by the houses, even drawing her hand along their shutters, as

if she would have been glad of some support. If her mind had

not been dead to all outside of herself, she would have noticed a

woman standing half-inside the old-fashioned porch of a neighbouring

house — a woman who had spent the whole night walking to and fro and

in and out of the quiet lanes in the vicinity, terribly fearless of

the belated and half-tipsy wanderers who had greeted her with gibe

and insult, and meekly obedient to the policeman’s gruff behest to

“move on.” This was a young woman, dressed in thin garments of

tawdry finery, with a fluff of golden hair about her face, like a

neglected aureole, and with blue eyes which looked like faded

forget-me-nots. It was Kirsty Mail.

When Kirsty saw Grace issue from the door of Mr. Sandison’s

house she herself but drew back farther into the shadow, not wishing

to be seen by her who had met her so inhospitably on the previous

evening. But when she saw the old woman creep along, with her

strangely groping hands, and marked her grey head bare to the

morning breeze — for Grace wore not even her cap — then Kirsty felt

that something was wrong, and first she peeped from the porch, and

then she stole after the fugitive.

On and on went Grace, and on went Kirsty after her. It

struck Kirsty very soon that the old woman was going she knew not

whither. She walked like one blind, and every moment her step

became more automatic. “Is she out of her mind?” reflected the

younger woman. “Perhaps she is one of those who have fits of

insanity, and it may have been a fit coming on, which made her so

harsh to me last night. Poor old soul!”

Suddenly the old woman paused, made one more stumbling

effort, and sank to the ground. Kirsty was by her side in an

instant.

The world was waking up by this time. Two or three

workmen were hastening to their daily labour, a shop-man was taking

down his shutters, and a policeman was lounging at a corner, waiting

to be relieved from his duty. These all crowded about the two

women. They looked rather suspiciously at poor Kirsty; but

when she declared that she knew the old lady, that she was the

housekeeper at Mr. Sandison’s in Penman Row — they were not so far

from that quarter as to be ignorant of the name — and when Grace

herself was discovered to be speechless, they found they could not

do better than accept Kirsty’s guidance.

So they carried Grace Allan back, staring, wide-eyed, and

unresisting, Kirsty following, rendering kindly little attentions.

Penman Row was still empty and silent. The prolonged ringing

of the door-bell gave the first notice to Mr. Sandison and Tom that

something unusual had happened. The men told where and how

they had found the stricken woman. While they carried her

up-stairs to her own room Mr. Sandison, going into the parlour to

search for some homely restorative, discovered the ravaged Bible.

And Kirsty, cowering down beside Tom, sobbed out, —

“I missed you last evening, and I didn’t think I’d dare to

face her again; so I was watching about for a chance of seeing you

this morning. It seems just like providence. Poor old

lady! She makes me think of dear old grannie. I’m glad

she was dead before she knew that I — Oh, Master Tom, I’ve been a

wicked woman. D'ye mind that picture you gave me in Lerwick,

because I fancied it was like grannie? Well, I’d always kept

it, though with its face downwards, in my box, because I couldn’t

a-bear to see it. An’ only the other night, Cousin Hannah —

her I’ve been with since I went wrong — got it, and took it out o’

the little frame, that she might put in something else, and she tore