|

[Previous Page]

THE DEBTORS.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER I.

THERE were great

rejoicings at Coalfield. After three years' absence its lord

was returning to his Warwickshire estates for a period of residence.

The old lord, his father, used to live there, but the young lord was

almost a stranger, who had lived half the year in London, the other

half abroad, or at least anywhere but at home. Everybody on

the estates was delighted at his coming. If only he would stay

and bring them home a countess, and be all that his father was!

Plenty of work awaited him; but then he was said to like work, such

tough work as reading up bluebooks and working on Parliamentary

Committees. An agent had managed everything; not an oppressive

agent—anything but that, only he would not do what a lord could do,

or grant what a lord might grant. Therefore, questions of

repairs, compensations, leases, and what not, had accumulated for

appeal. The agent was a lawyer. He was an upright and

careful man, and he too was delighted at my lord's return, which was

to settle many things easy to settle in a friendly discussion, very

hard to settle by any number of letters. Then there were the

works; but they were under another manager, one of my lord's own

choosing, whom he had brought there a perfect stranger, and who had

contrived to make his way among the people of Coalfield, certainly

not by dint of amiable manners. But he had made his way, and

married Mary Best, too, daughter of Mr. Best, the lawyer land agent,

and the very best of the Bests, as the good people said, intending a

mild joke and making a sincere compliment, for Mary Best was a sweet

and good and beautiful girl, and made an admirable wife to her

somewhat saturnine and gloomy husband.

George Raleigh was one of those misplaced human beings, who

are not in accord with their positions, who rarely fit into them,

sometimes rise above and sometimes fall below them. He had

been a mechanic—an ironworker, and, what is rare, clever at the

craft he hated; but he would have hated any craft, and he could have

excelled in any. He had been a handsome boy, had been

conscious of it, and had learnt nicer habits in consequence.

"He paid for a good wash up," his comrades would say, and so he

washed. He was conscious too of something better, of a

superior mind, and that too he strove to brighten. He studied,

not desultory books, but good, hard, manly themes. He was a

student of mathematics at a working men's college, where he first

became acquainted with Lord A—. A student and a first-prize

winner, how be despised the prize—it should have been for him the

honours of a great University. He despised the very teaching

he received, because it was not the highest. But what with his

mental culture, his personal beauty, and his manner, to which his

bitter pride gave a temporary reserve and dignity, Lord A— was

completely fascinated; and, after giving him the means of further

qualifying himself for the position, he had made him manager of his

works—for this modern lord was also miner and manufacturer, the head

of a great army of industry.

George Raleigh had not been liked at first, for the people

were quicker than his lordship to discover that he was proud, with

that pride which is akin to meanness, and which makes a man ashamed

of what he is and anxious to appear what he is not. That he

was tolerated now, that his faults indeed were overlooked and

condoned altogether, was chiefly owing to his connection with Mary

Best.

He had taken Mary out of her father's house in Coalfield: the

pretty country town by the riverside, set in a nest of gardens, at

the foot of which the coal barges glided in all the lights that

were, of sun and moon and stars, except when the river froze over

now and then in a severe winter, and made a bridge over to the

uplands white with snow. He had taken her away over these

uplands and on to the moor beyond, to a house built near the works,

with an ample garden of rather intractable soil, and plenty of room

to grow in without and within.

And they did grow. Five children were born to George

Raleigh, and they lived and throve in the moorland air, though it

was clouded with the smoke of furnaces whose fires burnt day and

night. They were handsome, lively children, and made the house

gay from morning to night, keeping their mother too in constant

occupation, and another besides. At one time Mary had been a

little delicate, and her youngest sister, Lydia, had been spared

from home to help her. She could well be spared where there

were still three left, and, therefore, finding plenty of work in her

sister's house, there Lydia chose to remain. And there were

comings and goings of the others and of their friends, for all the

Coalfield folks were friends of the Bests, and altogether Moorhouse

was as pleasant a home as a man could wish, provided that man was

reasonable and moderate in his wishes.

Lydia had to keep sharp watch over her flock without the

garden walls, for they were ever ready for a descent upon the works,

where all sorts of mischief might be apprehended, besides danger to

careless life and limb; only there was Isaac Benton, clerk and

under-manager, who never failed to march Master Walter back to the

house, if by chance the young gentleman should make his escape.

He and Lydia were very great friends, and for that matter so were he

and Mary; but the master of Moorhouse declined to receive him there

on a footing of equality, and happily the young man went on

unknowing. He went home to his mother's house and to the

tea-meetings of her friends—strictly confined to the body of

Primitive Methodists—without the slightest feeling that he ought to

have been included in the invitation to the gayer gathering at

Moorhouse—without the slightest envy of those who were invited, even

though Lydia Best would be there.

Lord A—had arrived. A large, loose-framed,

careless-looking man, restless in his movements, boyishly simple in

his habits, and without any manners at all. He was shy, almost

painfully so, a rare thing in one of his class. Most people,

the humblest and plainest of his farmers, nevertheless found it easy

to get on with him; found him liberal, humble, sincere, and wondered

at his knowledge of farming, of crops, and breeds, and soils, and

manures. The restless eyes under those hanging brows were

observing perpetually. If the farmers had been craftsmen they

would have been equally impressed with his knowledge of their craft.

Lord A— had made his appearance at the works. He had

tired out the manager going over them, moving about in his own

restless fashion—now here, now there, asking a question of this man

and another of that, and not doing the thing in a methodical manner

at all. His lordship was going over the accounts too.

Was he about to do it in the same way, not going through the nice

clean balance sheet, with its ready vouchers, but throwing open a

ledger here and a day-book there? Precisely. That was

exactly what he did; he took an item and asked a question here and

another there, till it was no wonder that the manager got confused

over it, and could not quite explain his beautifully exact balance

sheet.

George Raleigh was not only confused; he was disturbed in no

ordinary degree by the request that the books and vouchers should be

sent over to his lordship that he might look through them at his

leisure. They could hardly be spared for any length of time,

he was told, and he replied that he should not want them for any

length of time; that a single evening would suffice.

"What does it matter?" said Mary; "let him work away at them.

I'm sure many is the night you've sat up over them when you needn't

have done it, and I've looked from our window and seen your light

burning—one little light in the dark corner looking out on the moor,

and all the great fires roaring behind it—and have longed to come

and peep over your shoulder and give you a good fright, asking what

you were doing there."

Aye, what had he been doing there?

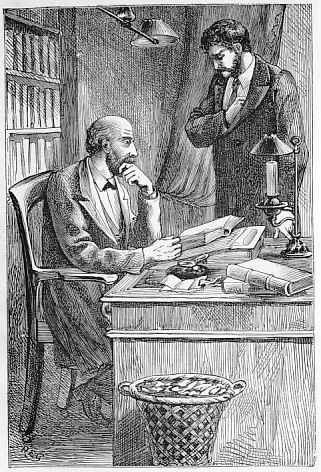

Lord A— sat in his library over these books and papers,

getting more and more absorbed; pulling down his brows more and

more; snatching bits of paper, insides of envelopes, and what not,

and making rough calculations, and then starting to his feet and

walking up and down the room.

It was very late when Lord A— went up to bed that night;

rather, it was very early in the morning when he lay down for a few

hours' sleep; and before doing so, he had drawn up a statement, and

arranged his papers, and put slips into the books for reference on

the morrow. George Raleigh was coming on the morrow to receive

them back. Well for him that he from whose hands he was to

receive them was a Christian, and not in name only; that this very

night he kneels by his bed in child-like prayer, and that after one

petition he pauses almost with a groan. And that petition

is—"Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass

against us."

*

*

*

*

*

"My lord, I have a wife and children!"

The words came from the dry lips of George Raleigh, as he

stood before his judge, before the man who at that moment had

supreme power over his destiny. That man was his employer,

Lord A—, not seated on the bench, indeed, at which he had taken his

place as a county magistrate, but at the library table, on which lay

the books and papers examined so anxiously the day before.

They had been gone over again with the manager, and their

discrepancies pointed out, till the truth had been brought home—the

truth that the accounts were falsified, and that a large sum

remained to be accounted for. It had been accounted for thus:—

"I meant only to use the money, not to keep it; and having

laid the foundation of a fortune with it, I would have returned it.

It was in my hands. The temptation was great," said George

Raleigh.

"But instead of winning you lost, and this," replied his

lordship severely, laying his hand upon the falsified books, "is the

result. Your course of specious dishonesty culminates in

felony."

"It was a private tribunal George Raleigh stood

before, but it was a terrible one."

It was a private tribunal George Raleigh stood before, but it

was a terrible one. Lord A— had raised him, trusted him, been

"the making of him," in vulgar phrase, and now he had the power to

undo him.

"I have a wife and children," he pleaded, and the words

almost stuck in his throat, for he despised himself for their

abjectness, and kept his eyes upon the ground that they might not

reveal the fierce fire of rage that burnt there. Why had this

man dominion over him? Why had he been obliged to seek fortune

in this quagmire, instead of inheriting it with honour, as this

other man had done? In that case might not their positions

have been reversed?

"I do not know that I should be doing right to hush this

matter up," said Lord A—. "It is a very grave thing to allow a

criminal to go unpunished; to let loose upon society, without a mark

set against him, a man who may do others incredible mischief."

"I pledge my life, my lord, if you will give me time, to

repay you every farthing."

"You are sanguine," said Lord A—.

"It will kill my wife," he said, and glared fiercely at his

foe; "she is connected with people proud and honest."

"I know that," said his lordship. "I have known them

all my life. How many children have you?" he asked abruptly as

was his way. "Five, my lord."

"Boys?"

"All boys, my lord."

"To bear your name and your shame." Raleigh winced.

Lord A— was cutting deep. Once more he knitted his brows, and

looked among the papers at his elbow, and George Raleigh waited.

At last he looked up. It was the verdict, and George

Raleigh's joints loosened and his tongue clave to the roof of his

mouth.

"I shall not take proceedings against you," said Lord A—,

"for the sake of your wife and children. Be an honest man in

future, and I shall not repent my leniency. 'One is our master, even

Christ,'" murmured the peer, almost to himself. He did not

finish the sentence, "and all we are brethren," but not one of the

hundreds who laboured for him, hand to hand, felt it more truly in

his heart.

George Raleigh cast a hungry glance at the papers; but his

lordship tossed them into his desk, and bowed his late manager's

dismissal.

For dismissed of course he was, and that to the astonishment

of all Coalfield, who attributed it to the same caprice which had

brought him there, and the feeling of Coalfield was in his favour so

far as to regret this second caprice, which seemed a little unjust,

and was very hard on a man with a wife and family. The affair

diminished Lord A—'s popularity not a little, indeed; but no reason

was ever given to justify him.

There was only one man who knew the real reason for George

Raleigh's dismissal, and that was his wife's father. It was in

kindness to the family that Lord A— employed him in rectifying the

accounts, and putting them into the hands of the new manager; but it

proved a complete heart-break to old Mr. Best. He never was

the same again, and shortly afterwards he died.

But there was one who more than suspected the truth, and that

was Isaac Benton. He offered himself for the situation vacated

by Raleigh, and, by what seemed another caprice, was rejected.

The new manager was a stranger, but a man accustomed to the work,

and highly recommended—an ordinary manager and an ordinary man.

Dismissal seemed to be indeed a heavy penalty to George

Raleigh, for he either could not or would not apply to Lord A— for

help in obtaining another situation, and one after another was lost

in consequence. It was not everything he could do now, having

got into a groove, and being altogether unwilling to do the work of

a subordinate, and so he remained idle month after month. Mary

tried to get her father to lend or give him a few hundred pounds to

begin manufacturing on a small scale; but Mr. Best would neither

give nor lend, and Mary held to her husband, and learnt to despise

her father, which added more and more of bitterness to her lot.

It was not till later that she knew what terrible justification

there was for his severity.

The Raleighs moved out of pretty Moorhouse, and took up their

abode in the neighbouring town, the headquarters of a great variety

of metal manufactures. They did not go quite into the town.

It was not a pretty town, like Coalfield, standing among gardens,

but one of narrow dismal streets, arched over by a roof of smoke,

streets steep and stony, and foul to hideousness. The water

was too scanty to allow of cleansing. Outside the town Mary

could breathe more freely and the children would grow up stronger

and healthier, so they took a house and garden, a broken-down sort

of place which was even cheaper than half the room would have been

in the heart of the smoke.

Poverty was new to Mary Best, and yet she met it bravely, all

the more bravely perhaps that she did not know it. She had to

give up her servants, and very hard she would have found the work of

her household, but for Lydia. Lydia insisted on going with her

and sharing with her all the toil and all the privation, when she

might have returned to her father's house, with its ease and

comfort, its disciplined servants and its pleasant society.

So Lydia made puddings and washed brown holland pinafores,

and scrubbed blackened hands and faces, and polished knives for Mr.

Raleigh, who did not like to see dirt and disorder, and liked still

less to help away with it, and all with boundless cheerfulness.

She had sometimes other work to do which called for other qualities.

Mary was often troubled about other things than puddings and

pinafores. If that had been all, she could have borne it; but

her husband had changed with the change in their fortunes. He

was irritable, morose, bitter, a castdown and despairing man.

And it often fell to Lydia's lot to soothe and support her sister's

spirit under the trial of seeing him thus.

And Mary, when she knew all—for her father had been unable to

resist telling her—still sympathised with her unhappy husband, for

misfortune was heavy on him, and they were fast approaching beggary.

If it had not been for Lydia's allowance and even Lydia's jewels,

the family would have been starving. And it seemed coming to

that in spite of all.

It was at this point that Mary wrote to her father for the

last time, beseeching him to help her husband, and Mr. Best,

happening to come across Lord A— while the letter was fresh in his

mind and still in his pocket, showed it to his lordship, as much as

to say, punishment is taking its course after all. "I offered

to take her and all the five of them, and let him go to Australia,"

said the old man; "but she won't hear of it."

The very next post carried to George Raleigh, the offer of an

agency for Lord A—. It was sent from the new manager, and only

accepted, and that with bitterness, when Raleigh had ascertained

that it was offered not only with Lord A—'s knowledge but at his

suggestion.

Not long after this Mr. Best died, and his daughters

inherited each her share of his little fortune, but in the case of

Mary Raleigh it was tied up strictly under the marriage settlement

drawn up by her father's own hand; her husband could not touch a

penny of it. The interest of it, a paltry hundred and fifty

per annum, might be of use to Mary and the boys to live on, it was

of no use to him. What he wanted was money in his hands, money

with which to make money, twenty, fifty, and a hundredfold.

Before he died, old Mr. Best, in danger of losing his child's

affections, had entrusted to Lydia also the secret of George

Raleigh's dismissal, telling her that Mary already knew. The

good, brave wife had known her husband's secret and kept it

faithfully—had known and never once upbraided, had never even ceased

to sympathise with her husband; nay, had felt a more tender love for

him bearing his burden of secret sin, as well as the misfortune

which was its, to her, lesser punishment.

But with Lydia it was different, and her secret knowledge

gave her a difficult part to play. She could no longer

sympathise with her brother-in-law in his misfortune. She was

indignant at his conduct, not only at his dishonesty and crime, but

at the way in which he had given himself all the airs of an injured

man under the ruin which he had brought upon himself and in which he

had involved his innocent family. It was very hard for Lydia

to conceal her utter revulsion of feeling when she knew the truth.

Lydia was too just to be lenient, and she had not yet learnt the

mercy that is above justice.

"Lydia the Lucky," her father used to call her, she seemed to

draw so many things to herself; but it was simply by being good that

she so drew them. One of the good things was a legacy of

£1,000 left her by a godmother, in gratitude for the unfailing

attention of the girl to the dull, sick old woman whom she had loved

to cheer. This money Lydia was free to do with as she choose.

It had come to her shortly before her father's death, and she had

simply left it in her father's hands, vainly begging some of it for

George and Mary, and now she gave it all. And that not for

Mary's sake only. She was a large-hearted girl Lydia, and she

had some sort of feeling that prosperity might be good for George

Raleigh, though she could not forgive him for what he had done.

That money was the foundation of his fortune. He traded

with it; he speculated with it; he financed it into many times its

value; and in a year or two he had established himself at the head

of a flourishing business.

Lydia all this time remained with her sister. The

establishment was only increased by a single servant, therefore

there was work enough to do, though the hardest of the drudgery was

removed. Lydia boarded with the family, by way of being

independent; but she was well worth her board and wages besides, as

Mary knew. There was plenty of work with five growing boys to

keep clean and tidy, and Lydia taught the three youngest besides.

In the making of money George Raleigh was now in earnest too deadly

to spend more of it than could be helped. He spent none

whatever in display, as he might once have been tempted to do.

They did not even leave the broken-down old house which they

had taken when they first came into the town, because it reminded

them of their country one. They got a lease of it very cheap,

and repaired and improved it.

It was in the bottom of a valley. Most houses there

were either at the bottom of a valley or climbing up the sides of a

hill. The town was built over any number of hills and valleys,

converging towards a centre, which centre, blackened underneath with

filth and grime and overhead with smoke and soot, was appropriately

called "The Hole." The Raleighs' house was just without the

town, where the garden met the brown stony pasture of what had once

been a water-course, only the water which had once wasted itself in

dirty puddles among the stones was cut off and gathered, along with

other similar streams, into a reservoir above, for the supply of the

town. They had a good garden, the chief attraction of the

house, and the children could roam beyond it, which was still

better, up the steep valley to the waterworks and on to the fresh

breezy moor beyond, from which the wind seemed always blowing as if

intent on making the dwellers in the town consume their own smoke,

which they did accordingly with their own lungs.

But now that the pressure of poverty was removed, all Lydia's

efforts could not make of Mary the bright and cheerful housewife of

old. It seemed as if she had taken upon herself the

humiliation which ought to have been her husband's, and that she was

bearing it with her to her grave.

George Raleigh showed no humility whatever. The effect

of his fall upon his hard, proud nature had been to make it harder

and prouder still. The effects of the forgiveness, which had

saved him from utter ruin, had been for his character wholly evil.

If forgiveness does not humble and soften, it does the very reverse.

It is so with God's forgiveness once known and slighted; and unless

a man learns by the grace of God to love him who has pardoned him a

great debt, he will most likely hate him. George Raleigh was

glad enough to escape from the penalty of his wrong-doing, but

towards the man who had allowed him to escape he felt no gratitude.

He had had the most abject fear of the ruin from which he was saved;

but the man who had saved him he could not love, and so he hated

him.

With such feelings in his heart it was of course impossible

for George Raleigh to be a Christian. But then he had always

professed to be a Christian. To be a professing Christian was

a habit, an obligation, a necessity. The people in these

northern towns, that is the respectable people, like the respectable

people in other English towns, were professing Christians, and

profession ran high in this particular town. There were many

and vigorous sects there. To belong to one or other was also

an obligation, a necessity. To be favourably known in one of

them was to thrive. It was equivalent to a good business

connection to be highly esteemed among the brethren. Given

such a soil as the heart of George Raleigh, could any climate be

more favourable to the production of hypocrisy? No man becomes

a hypocrite all at once, or of malice prepense.

Hypocrisy is too hateful for that. It requires such a

conjunction as this to develop a man into a thorough hypocrite; and

that was what George Raleigh became. He united himself to the

Primitive Methodists, a very flourishing community in his

neighbourhood, and became a prominent church member.

In this connection he come in contact with an old

acquaintance—Isaac Benton. Seeing that under the new manager

promotion at the works was a long way off, Isaac had left them and

Coalfield altogether, and come into town to shift for himself.

It was also a comfort to him to be in the same place as Lydia Best,

though his shyness prevented any nearer approach to her. But

his love was a sturdy growth, each season found it stronger and

stronger, in spite of long winters and little sunshine.

And Isaac, like Raleigh, was bent on making money. He

knew that Lydia Best, had money of her own, and he would not seek

that or seem to seek it. He would not ask her to stoop to him

while he remained another man's servant. He would be his own

master and her equal before he sought her.

The good, honest fellow made a confidant of Lydia's

brother-in-law; not indeed concerning his love, that was too sacred

a matter to be confided to any human being, but concerning his

prospects in business; and Raleigh laughed at his slow gains, his

modest ambition, and thought of him as a mere plodder. Isaac

bought from Raleigh the material he required for his small

manufactory, and plodded on unconscious, slow, and sure, working

late and early, not only superintending but often laying his own

stout hands to the works. His dreams were of adding furnace to

furnace, turning out more and more thousands of reliable nails and

bags of bolts and nuts, and of one day buying a house a little way

out of the smoke—a house within its walled garden, and setting in it

Lydia Best and his own dear old mother.

Mrs. Benton knew little of Lydia Best, and so had no thought

of her in connection with Isaac; but she thought her son was already

far enough advanced in age and in prospects to marry. He was

her only son, and she was a widow, and she wanted to see him settled

in life before she died. Nay, she felt her strength failing,

and thought she would be glad of a daughter in the house against the

day when it would fail utterly and there would be no one to do for

Isaac all that she had once done with ease and pride.

But it was not a fine lady like Lydia Best she coveted, who

could doubtless play on the piano and do fancy work, but who could

not be expected to make a pudding or cut out a shirt. No.

She had looked out "in the communion" for the kind of daughter she

coveted, and such was Rachael Prosser; and the dear old lady

cultivated Rachael Prosser accordingly. She asked her to come

to tea and bring her work, and she kept her so late that it was

impossible to send her home alone. Isaac must accompany her

thither, which he did obediently and calmly, while she saw them set

out each time with a beating heart.

Rachael was a very good girl, doubtless, a little childish in

her words and ways, the result of real simplicity and not of

affectation; but neat-handed and nice-looking enough. Many a

man would have fallen in love with her exactly as Mrs. Benton

wished, but not the man who had set his heart on Lydia Best, with

her swift, eager words and ways, her life and movement, and deep

though soft colouring. Rachael was a shadow by Isaac's side;

her presence unfelt as a baby's, or giving only the pleasure which a

pretty picture of a girl may give.

And then about this time he was admitted to that other presence

which thrilled him through and through. He did not need even to look

at Lydia to feel this sensation of new life. He had only to hear her

voice. No, not even that; he had only to sit in the same room with

her, to touch the cup she had handled, or the book she had touched.

Hearing of his being established near them, Mary and Lydia

had insisted on his coming to see them. Mary's boys were

delighted to greet their old friend, and of course Isaac's delight

in them was unbounded; though how it could have been so delightful

to be sat upon in every possible and impossible manner, or pulled

five different ways at once, was a little mysterious. George

Raleigh looked on with quiet contempt. The boys never ventured

to treat him in that fashion. Isaac Benton was in this, as in

everything else, he thought, only a good, stupid, loutish fellow.

But Mr. Raleigh changed his tone when he saw how Isaac

kindled at the opportunity of doing Lydia any little service; how

his grey eyes beamed on her with light in them which almost filled

George Raleigh with envy—it revealed a heart so true and high; and

when he saw that Lydia, with all her spirit, showed a consciousness

in his presence which made her gentler and sweeter and quieter, and

certainly not less happy. It was time to put a stop to

nonsense, this he thought then, for George Raleigh had quite other

views for his wife's sister. He was fond of Lydia in his way,

and proud of her. He would even have sacrificed himself in a

small degree to have advanced her to some matrimonial sphere where

she might have shed on him and his reflected lustre. But she

was still of extremest need to him. There was time enough for

her to marry. Men were in the habit there of building up

immense fortunes in a single lifetime, and enjoying them while

comparatively young. She might marry one of these. He

would soon move out of the little house in the valley, where he had

remained quietly in a chrysalis state, and enter upon quite another

phase of existence; till then he would keep Lydia and her money.

If she married this fellow, he would have to give the money up, and

give up Lydia too. He did not intend to do either.

CHAPTER II.

IT was Communion

Sunday in Brook Street Chapel, which George Raleigh attended.

The sacrament had succeeded to the simple service. The

congregation had sung a hymn. At a long table covered with a

clean white cloth sat the intending communicants—a table not unlike

that in Leonardo da Vinci's wonderful picture, only that many more

were seated here, and seated facing each other. A perfect hush

reigned throughout the chapel, a hush which seemed intensified round

the table. Some of the faces there were wrapt, almost like

that of the St. John, in an ecstasy of divine affection; a few were

wet with tears, chiefly agèd women, waiting, perhaps longing, for

the time when, released from every earthly care and trouble, they

should drink the new wine with Christ in his Father's kingdom.

On all the faces there was shed a spiritual light—a light that never

was on sea or land—something which testified to emotions not born of

earth.

Isaac Benton sat next to his mother, his manly face full of

tender awe and a sort of resoluteness mixed with it, as if he was

making up his mind—which indeed he was—to walk worthy of his holy

calling. His mother, a tender-faced, slight woman, sat between

her son and little Rachael Prosser, her desired daughter, and was

shedding thankful tears. On the other side of Isaac sat George

Raleigh, with Mary beyond him. On his swarthy face there was

neither tenderness, nor awe, nor holy resolution. The light

there was a lurid one, such as one might fancy cast by the flames of

the abyss.

Lydia, sitting apart with her sister's eldest boys, bent her

head with a strange, troubled, almost awe-struck feeling, as she saw

her brother-in-law sitting side by side with Isaac Benton at that

table. She herself was not "in the communion." She had

not, though she generally went to chapel with the family, severed

her connection with the Church of England.

To understand her feeling, it is necessary to relate what had

taken place the night before. On that summer Saturday eve,

Lydia and Isaac had met, not by chance, upon the moor. Lydia

was leading her boys round the margin, grassy and flower-tufted, of

the great sheet of water fed by the moorland streams, and enclosed

from the valley by a strong embankment; and Isaac had met her there.

Then they had come home together, still early, for the boys

to go to bed; and Isaac, instead of bidding her good-bye then and

there, seemed as if about to enter the house with her. But its

master met them at the gate, and greeted the young man with so cold

a reception that nothing remained for him but to turn away. He

was about to do so, when, looking to Lydia, he said, "What a lovely

night it is. It seems a pity to go in so early;" and she, as

if by secret compact, answered, "Yes; let us stay out a little

longer."

The boys had gone in obediently in their father's presence,

and, nodding to her brother-in-law, Lydia strolled away up the

valley again with Isaac, "for all the world," said George Raleigh,

indignantly, to Mary—"for all the world like a pair of lovers."

Mary was busy about the house when Lydia came back in the

soft summer dusk. George Raleigh was sitting idly at the open

window; at least, he looked idle. His thoughts were busy

enough; that scheming brain of his was seldom idle. Lydia's

voice sounded softer than usual, as she asked where Mary was; and

Lydia's cheek and eyes were softer and brighter, too, if George

could have seen them when she went and found her sister, and laid

her arms about her neck and whispered something, and they kissed

each other, and Mary fell a trembling.

When Lydia once more entered the parlour, the lamp was

lighted and her brother-in-law was reading a dry trade circular.

He threw it down impatiently, however, and gave her the benefit of

his attention.

"So you've got rid of that fool of a fellow at last," he

said.

Lydia did not answer.

"He's the stupidest fellow in the world," he went on; "he

can't see when he's not wanted."

"Who's that you're speaking about?" asked Mary, coming into

the room on an errand connected with the preparation of supper.

"Isaac Benton," replied her husband, shortly.

"He's not stupid in one thing," said Mary, as she went out

again, with a meaning glance at Lydia.

"He's not stupid at all" said Lydia, bravely.

"Not in looking after you at least. Mary is right

there," said George, scornfully.

Still Lydia was silent. His tone, even more than his

words, displeased her. She dared not trust herself to speak.

A sense of irritation was upon him, however, and he did not

stop there. He went on to communicate it.

"Your money would be just the thing for him," he said.

"He began with nothing, and very little would stop him; he has no

intellect for business."

"He has intellect enough to be honest, at least," flashed

from Lydia, on whom the irritant had acted.

The words were no sooner uttered than their utterance was

repented of; but they could not be recalled, and as a flash of

lightning penetrates for an instant into the darkest cavern, the

words had lighted up the facts that were in Lydia's mind, and George

Raleigh could read them there. From that moment he knew that

she knew of his dishonesty, and that there was perfect understanding

between them. But Raleigh drew a wrong conclusion, and that

was, that Lydia's informant was Isaac Benton. On Isaac Benton

he resolved therefore to be revenged. In the retirement of

their own room when Mary told him of Lydia's confession, the

conclusion seemed verified, and George Raleigh's dislike of Isaac

Benton turned into bitterest hatred.

And so Lydia thrilled and trembled with intuitive fear and

awe when she saw the two seated together at that table in the

chapel.

A grey-haired elder handed to one of the communicants a cake

of bread, and the man broke it and, taking a portion, handed it on

to his neighbour. Thus it went round the table, and in the

same way the cup was handed from one to the other, and among the

rest from George Raleigh to Isaac Benton. The latter looked up

as he took this last, and Lydia thought she could read the look upon

his face, and that it said, "We are already brothers." But to

this look there was no response on the part of Raleigh. The

dark-bearded face, stamped with self command and concentration,

remained unreadable.

On Sunday evenings the Bentons, mother and son, were always

alone. They had "The Books"—Bibles and hymn-books—laid on the

table in the little parlour, and there they read and talked between

their readings. The room in which they sat had no pretensions

to be a drawing-room; it had no pretensions whatever. It was

just such a room as might have been that of a highly respectable

workman, though Isaac's father had been a Wesleyan minister.

It was after her widowhood that Mrs. Benton had made herself a home.

Owing to the requirements of the sect the Wesleyan minister is

homeless, being resident for only three years in any place, and

moving into the house attached to the chapel, and furnished for his

reception. It was therefore a very simple one, but there was

refinement in its very bareness. Its one armchair was occupied

by Mrs. Benton, and Isaac sat upright before her, not lounging after

the easy fashion of the youth of his day. But he was not

reading. He was looking out of the window, which was open,

with nothing better to contemplate than the fragrant box of

mignonette on its sill. He was meditating on the necessity of

telling his mother of his love for Lydia Best.

Neither was Mrs. Benton reading, though her spectacles were

in their place and a book upon her knee. She was thinking of

speaking to her son about Rachael Prosser and her wishes concerning

her favourite, which did not seem likely to be realised without

further active intervention.

"My eyes are getting dimmer every day, Isaac," said the old

lady, taking off her spectacles, and wiping them with her

pocket-handkerchief. "I can hardly see to read now at all,

even with my spectacles."

"You want a stronger pair, perhaps," said Isaac. "Would

you like me to read to you, mother?" he added kindly.

"No, thank you, dear. I would rather talk to you a

bit," she replied. "I often weary in the long days when you

are away at work for somebody to talk to."

Isaac looked at his mother. He looked to see if she had

any signs of sudden failure in her face, for he had never heard a

complaint from her before.

He could see none, however. "Ah, mother," he said, "you

wouldn't have been so lonely if little Nelly had lived."

Nelly was a sister who had died in infancy, to the great

grief of his mother—a lasting grief, for she held that she had never

been wholly able to resign the idol of her heart. And Isaac

had resolved that when he married he would not quit the mother to

whom he was both son and daughter. She whom he took for a wife

must take her for a mother too; but would she love the stranger as a

daughter?—that was the difficulty.

She looked back at him almost reproachfully, as if she blamed

him for bringing up to her the great sorrow of her life. "The

Lord gave and Lord taketh away," she repeated solemnly.

"Blessed be the name of the Lord."

There was a pause.

"Isaac, I might have a daughter still," said the old woman,

tremulously. Her voice was full of emotion. This was a

trial to her, stirring her out of her sweet, patient, calm into

anxious expectancy. For it was a great change in her life—the

only great change that could happen to her, except the last, and it

involved too the happiness and stability of a life dearer to her

than her own.

"And you shall, mother," said Isaac, rising up before her.

"I have been thinking how I should tell you this very afternoon."

A tremor passed over his mother's face; her hands held by the book

on her knee, but she controlled her voice, and answered, "I am very

glad. I love her dearly, and she will make a good and faithful

wife."

Isaac looked amazement—not unmixed with consternation.

His mother did not know about Lydia. She had too evidently

some other person in her mind, and he could not be ignorant as to

who the person was.

"Rachael will make a good wife," she repeated.

"But it is not Rachael I mean, mother," he found courage to

say.

"Not Rachael!" she repeated.

"No, mother; it is a lady whom I have known for several

years—Lydia Best."

Mrs. Benton was too much of a lady to express her

disappointment in any way. It was nevertheless apparent to her

son.

"You are not vexed, mother?" he said, tenderly.

"I thought you knew no other so well as Rachael," she

answered evasively; "but it may make a great difference to me."

"How, mother?"

"Rachael would have been content to come to me as a daughter,

but now I must give up my son."

"No, mother," said Isaac, warmly. "Nought but death

parts me and thee. Lydia will come to you, as Rachael would

have done. Rachael may be very good; but she is not like

Lydia. Mother, you do not know her; she is the sweetest,

noblest, truest woman in the world."

But Mrs. Benton saw her son through a mist of tears. To

her Lydia was but a stranger, and her last dream had dissolved.

She could not see with her son's eyes. She was ready to

believe good and not evil of Lydia, for she herself was sweet and

good; but she felt that her son's choice would never be to her what

Rachael would have been.

"Is it settled then?" she ventured to ask.

"Not in so many words, mother," he answered, simply. "I

had not arranged my plans. I only told her I loved her; but I

will speak of our marriage at once, now that you know."

"Then you are not sure that she will have you, Isaac," said

his mother, anxiously.

"Of that I am quite sure," he answered, in an untroubled

voice. "Such a one as Lydia does not accept love without

giving it. She would as soon take untold gold."

"I don't know," replied the old lady; "it is best not to be

too sure. She may tell you she did not mean anything.

There have been such things, Isaac, and will be again;" and with

beautiful inconsistency, she began to feel an anxious fear that her

son might not prosper in his wooing.

"And if she were such a one, mother," said Isaac, smiling

securely, "I am man enough to bear the loss, and to teach myself to

feel well rid of such a bargain."

The very next day, Isaac Benton, ever straightforward and

manly, sought a formal interview with Lydia, and set the question of

acceptance or non-acceptance speedily at rest. Then they

talked over their plans together, in another long lover's walk, at

the close of which Lydia instinctively avoided bringing Isaac into

contact with her brother-in-law.

Isaac had been right in his reading of Lydia's character.

She had not accepted his love without pledging her own, and that

without a drawback. She was his, ready to go to him when he

chose, and to enter into his life fully and freely, with all the

fulness and freedom of her own, and ready to say with Ruth, "Thy

people shall be my people, and thy God my God."

But Isaac chose to defer his happiness at the bidding of his

delicate scrupulosity. It was not that he thought of Lydia's

little fortune as placing her above him. He had no such

thought. He placed her above himself, it is true, but it was

on other and higher ground than this. But he would not have it

thought that she had stooped to him even by "the world," which Isaac

had learned to define very sharply. He wanted the world to do

honour to her choice.

He explained the position of his affairs to her, as he had

done to her brother-in-law—those affairs at which Raleigh had

laughed. He had begun, as that gentleman had said, on nothing;

that is to say, on a few hundreds, which were swallowed up in making

a start. He had no difficulty, however, in obtaining credit, a

credit which was justly and honourably used, as all credit ought to

be. He had obtained credit for the raw material, and adding to

it his knowledge and industry, he had amply redeemed the trust, and

had already considerably increased his little capital.

With the cognisance of all concerned, he had on this enlarged

his small factory, and with it the scale of his operations, and had

in consequence somewhat heavier engagements to meet. That he

could meet them punctually he had not the slightest doubt, for there

was no speculation in his business. He had added to the

material supplied by his creditors its new use and value, and the

money which was owing to him for the product he would pay to them,

minus his rightful share.

As soon as he could accomplish this, and buy with ready

money, he would hold himself free. Then they—how pleasant and

oft-repeated that plural was!—might marry, and move into a better

house, where there would be room for the mother as well as for the

wife.

Lydia was content. And Isaac brought his mother to see

her, and Lydia returned the visit, and was received with

old-fashioned courtesy; but not, as Lydia felt, with perfect

cordiality. In this, Isaac's mother was only acting out her

simple truthful nature. She could not all at once give Lydia

the welcome she had prepared for another, and she could not throw

into her manner a warmth which she did not feel. But she had

no intention of being cold to Lydia; nay, she had the firmest

intention to love, and love her well. Perhaps an additional

feeling of constraint was upon her from the little scene she had

just passed through with Rachael, and which she was obliged to keep

entirely to herself. She had taken the earliest opportunity of

telling Rachael of her son's engagement, and the poor girl had tried

to wish him happiness with the proper amount of friendliness and

unconcern; but she had broken down and wept instead, and murmured

through her tears, "You must not think it is any fault of his; you

must not let him know that I have been so foolish as to care for him

like this." And the old woman had answered sorrowfully, "No,

my dear, it is no fault of yours; but it is of mine, and I would

have been very glad if he had chosen you."

Quite closely after this interview it was not possible for

Mrs. Benton to be thoroughly cordial with Lydia. But as the

latter knew nothing of all this, she felt a little hurt at the

coldness of Isaac's mother.

Meanwhile George Raleigh was cherishing his hatred of Isaac

Benton, and brooding over it in his darkened mind. He had

refused the divine suggestions of forgiveness and reconciliation

which had come to him at the communion-table. He justified his

own feelings on the plea of Isaac's treachery; and the idea of

separating him and Lydia was uppermost in his mind.

It had not yet occurred to him how it was to be done.

It was certainly not to be done by using his influence openly

against Isaac. He had had enough of that. He could

hardly forbid Lydia's lover the house, for that would be to defeat

his own object, and come to an open rupture with Lydia herself.

Therefore he would wait and watch. There were circumstances

which he knew of not unlikely to yield a favourable opportunity for

doing Isaac a mischief. Isaac was in his debt—a debt heavier

than the young man, would have incurred if left wholly to himself.

He would rather have chosen to go on more slowly still. But he

had acted under the advice and influence of Raleigh in increasing

his business, and Raleigh, who had the most entire confidence in his

integrity, was himself his principal creditor.

Lydia, on her part, was filled with the most compunctious

tenderness towards her brother-in-law ever since her lightning flash

of anger had revealed to him that she knew his painful past.

Instinctively she kept Isaac out of his way. He should not be

wounded at present by seeing them together, and in time he might

forget her little sally—might come to regard it as an inadvertence;

even to think that she had spoken in ignorance after all. "He

has forgiven it," she thought; "I am sure that he has forgiven it,

and that in time he will be friendly with Isaac, for my sake as well

as for his own."

The circumstances which George Raleigh had in his mind as

likely to be adverse to Lydia's lover arose out of a crisis of trade

upon which the industry of the district had entered. Nor was

George Raleigh disappointed in his expectation. Such a crisis

is particularly hard on the beginner whose small capital is not

elastic enough to meet the strain. Bankruptcies are

inevitable, and one bankruptcy brings on another. The

dishonest trader, the man who is trading beyond his legitimate

means, who is trying to secure illegitimate profits by illegitimate

risks, may be the first to fail; but he is sure to involve others in

his failure—men who are not dishonest, but simply unfortunate in

having trusted him.

The very first week after his engagement one of Isaac's

customers stopped payment, owing him a little over two hundred

pounds. It does not seem a great sum; but the young man had

not great sums to spare, he did not deal in them; and, be it

remembered, the ruin based on small sums is far worse than that

which is based on great ones. The man who fails for fifty

thousand has generally less penalty to endure than the man who fails

for five hundred.

The loss of the two hundred was a great blow to Isaac.

It gave him likewise more than usual mental trouble and pain, for he

had trusted this man who had failed, as a man not only honest but

religious, a church member, a man of prayer. If he became

bankrupt, and Isaac could not rid himself of the feeling that it was

dishonourable, nay, dishonest to do so, who was to be trusted?

All at once his own position seemed to him insecure. All at

once Isaac Benton began to look anxious, even ill.

"It is so hard just at present to be put back in this way,"

he said to his mother, talking over the failure.

"But you have often said that you were bound to meet with a

check somewhere," she answered wisely. "You will get on for

all that."

"I don't doubt it, mother; at least, I never did till this

day or two, when I seem to doubt everything good," he said.

"You are depressed," she replied, looking at him anxiously,

"and you are not looking well. Why don't you go out this

evening?"

She was glad enough to have him to herself again; but, in her

unselfish affection, she thought another might cheer him more.

"Lydia has gone away," he said. "She has gone home for

a few weeks to Coalfield, to stay with her unmarried sisters."

That was enough perhaps to explain his depression, but he

continued: "I shall weather the storm, mother, if I keep my health.

I shall be able to collect enough to meet my liabilities; but it

will be close work, and a week's illness would ruin me."

"What makes you think of illness?" asked his mother,

nervously.

"There's a great deal about," said Isaac; "and I feel out of

sorts, somehow."

There was a great deal of illness about. The summer had

been an unusually dry one. The newly-introduced water supply

had not yet reached the poorest part of the town, where the people

depended for the most part on the springs and on the rain. The

springs had dried up and the barrels were empty. What there

was of water was half putrid. Bad water and overcrowded

dwellings had done their work. Fever and dysentery were

decimating the inhabitants of the worst districts and spreading into

more favoured localities.

Isaac Benton worked on, worked harder than ever, through the

hot and sultry August weather; but the cloud of depression which

weighed upon him did not seem to lighten. True, he had not

Lydia to cheer him; but he had Lydia's letters, only they did not

cheer him, sportive and gay as they were. Perhaps they were

too sportive, for Isaac's tenderness was deep and solemn, and to

jest over it was impossible to him. While Lydia, in whom the

sense of humour was stronger, often hid her most loving thoughts in

sallies of fun. From her living lips Isaac would have

understood these—he was not dense in any way, and her smile would

have made way for them; but written he failed to understand them.

They jarred with his mood, and his replies were forced and formal.

Still in jest, but somewhat disappointed with her lover's

correspondence, Lydia at length threatened to write no more.

The threat fell upon Isaac like a thunderbolt. Had he

only looked over the page he would have come upon a modest little

postscript, telling of the writer's immediate return, and playfully

appointing a meeting for the settlement of their differences by the

margin of "The Reservoir." But Isaac did not turn over the

page. He thrust the letter into his pocket and made talk to

his mother, who followed him with hungry eyes, as he went off to the

works, bearing himself more erectly and alertly than ever he had

done in his life, for that very day lie had been called upon to face

a fresh calamity. The illness which he had half dreaded had

not come upon stalwart Isaac Benton, and yet nevertheless it had

dealt him a secret blow. In a couple of days his bill to

George Raleigh became due, and the man on whom he had chiefly

depended for money to meet the engagement was lying stricken by

fever and unable to make any arrangement for the payment of his

debt.

What was Isaac Benton to do? He could not meet the

bill; but that he could not do so was no fault of his. There

was nothing to be done save to ask George Raleigh to renew it.

There was no doubt in Isaac's mind that his request would be

granted, the money was perfectly safe, both he and his debtor

perfectly solvent, and yet Isaac went forth to make it with the

greatest reluctance.

In spite of this reluctance, he lost no time in seeing

Raleigh and explaining how matters stood. It was easily enough

done. Very few words sufficed. "Hoskyns is laid up with

the fever, Raleigh," said Isaac. "I shall have to wait for my

money; will you wait for yours? renew for a month, that will be long

enough, for I will be able to meet it then, even if he is not

ready?"

The favour was reluctantly asked, but not in fear of a

refusal. When it was met with a refusal, Isaac expressed

astonishment and even indignation. "It will certainly never

happen again," he said; "but you must do it this time, Raleigh, if

it is only for your own sake. I have no friends to go to.

You know that the money is safe, and that this is the result of an

unforeseen accident."

"I know nothing of the sort," said Raleigh. "I tell you

what it is, you are presuming on our closer connection," he added,

with a sneer; "but it has not taken place yet, and I don't think it

ever will."

"I don't think it ever will " rang in Isaac's ears as he

turned away, sorrowful and indignant. It rang in his ears all

day as he went in and out among his men and did the work of two, not

swiftly but steadily, like the great power wheel which sets all the

rest in motion. He did not run about to borrow, to get the

money by fair means or foul, as George Raleigh would have done.

He knew not the ways of borrowers. He simply stuck to his

work. As he had said, he had no friends to go to, none on whom

he had kindred or other claims. So he took in goods and sent

them out, packing and directing up to his last order and writing

between, so that nothing should be left undone or unaccounted for,

and waiting all the while with a feeling of dread which he could not

overcome for the passing of the day on which his bill to George

Raleigh came due.

It came in its turn and matters took their course. The

bill was protested, and Isaac Benton was bankrupt. All who had

known the young man expressed pity and astonishment, for he had

gained universal respect; but none knew him intimately enough to ask

for explanation, or to offer substantial help.

Supported by his perfect integrity, and also by a sorer hurt

whose pain deadened that of his failure, Isaac still worked on.

Lydia, he believed had deserted him. He had told her nothing

of his trouble; but he felt sure that she must know all about it by

this time, and she made no sign. Would Raleigh have treated

him as he had done if Lydia had been on his side? Would he

have uttered that taunt if he had not known? Had she not said

she would not write again? He put away the letter in the

drawer of his desk; he could not bear to look at it, and he did not

answer it. Why should he answer it? He could not plead

with her now—he a man disgraced in the sight of men. Even in

the chapel it would be some time before he would again be allowed to

sit at the communion-table, and he would have to clear himself first

of the suspicion of dishonesty which must always rest on those in

his position. Old Mrs. Benton perhaps suffered more than her

son, for there was nothing to distract her in her suffering.

She felt the disgrace of failure still more keenly than he did, and

when he spoke of selling off everything and going to America or

Australia, she approved of the resolution, though her heart was like

to break. She would go with Isaac, she knew; but she could not

begin life again; she would but lay her dust in that strange land,

far from the grave which held her husband and her baby girl, and the

old eyes grew dim indeed with their bitter weeping.

Meantime Isaac was busy collecting all the money he could

wherewith to appease his creditors; but all was not enough, for

unfortunately Hoskyns was the one debtor who owed a large sum, the

other sums due to him were small and scattered widely, and now

Hoskyns was dead and there was no hope in that quarter, even if

Isaac had been willing to distress the widow and the fatherless,

which he was not. He would, however, offer to George Raleigh

all that he had, and he could not believe that Raleigh would press

him further. It was in the days, not very far back, when a

judgment could be taken out either against the property or person of

a bankrupt. George Raleigh elected the latter.

Ten days had expired and Isaac Benton had collected more than

half the amount of the bill, and with this he went to Raleigh at his

place of business; but the latter would not accept it. He

would have nothing less than the whole, and he could hardly conceal

his exultation that at the very last hour Isaac had no more to

offer. His vengeance would now be complete. He could

shut up the man whom he had learnt to hate in a prison, ruin him,

and drive him from the place. His purpose would be

accomplished more swiftly and surely than he had dared to hope.

And it was, so far as the imprisonment was concerned.

The night following, Isaac Benton slept in a prisoner's cell; but

better there, with conscience void of offence, than George Raleigh

under his own roof. His mother had risen superior to her grief

to comfort him. "I have done my best," he had said, and she

had answered, "Blessed is that servant whom his Lord when he cometh

shall find so doing." And so they had parted bravely, and the

old mother had undertaken to procure his release, by the sale of all

that they had if necessary, for they had made up their minds to go

away together.

CHAPTER III.

LYDIA had come

back to her sister's as gay and bright as ever. The very first

evening after her arrival she had stolen out after the children's

tea, but without their company, and wandered up the valley. It

was too late to take the boys, she had said, and she wanted a good

long walk, and Mary had understood and silenced their clamour.

The moon was rising; the big harvest moon, made to loom larger

through a sultry haze in the quarter where she rose. Lydia

passed slowly up the valley. Bells were ringing in the town,

ringing out the workers where the day was done; but they died in the

distance as she went up and on. By the time she reached the

margin of "the water," as the reservoir was generally called, it was

time for Isaac to be there, she had sauntered so. His works

closed at the same time as the rest, and he would not linger, save

to wash those great brown hands of his free from the soil of the

afternoon, and to snatch a hasty cup of tea.

Lydia sat down on the upper margin of the sheet of water.

Artificial as it was, nature was rapidly claiming it her own, taking

it into her plan, as it were, rendering it part of her general

aspect. It seemed already wrought into the yellow brown

moorland on whose marge it lay. The mosses and the wild

flowers grew down to its edges, down and over, and the tall tufted

rushes stood up around it. From where Lydia sat it seemed a

broad moorland lake fed by more than one moorland stream, and full

even in the parching heat. She sat and watched the moon come

within its mirror, dreaming pleasantly till all of a sudden she

started up and knew that she had been waiting long. She looked

once more down the valley, and along the track which Isaac must

take; but he was nowhere to be seen. Surely something had

occurred to prevent his coining. She looked at her watch.

He might have been with her an hour ago; he had never failed to come

thus early heretofore. The moon was shining on the water

still, but it was her last gleam before entering the heavy cloud

which was also reflected there. She looked up at the sky and

saw that there were hosts of them rolling up as if for battle.

Still she waited, and the sky darkened and darkened, and the water

at her feet grew black as ink.

Suddenly she was startled by a blaze, which lit up sky and

water and the far off lines of the moors. Again and again it

came. The summer lightning illumining the whole horizon, and

throwing out in strong relief the few spires and countless tall

chimneys of the town below. Lydia felt that it was time to go,

for these harmless flashes were generally the heralds of a storm,

and a storm was threatening now. The first heavy drops began

to fall as Lydia turned homeward, and she had only reached the

shelter of the porch when the rain came down in torrents, and,

following the forked lightning instantaneously, the thunder crashed

right overhead as if the towers of heaven had fallen.

Lydia had not met Isaac by the way. It was now certain

that he had not kept his tryst. But why? Lydia's heart

was too high to distrust her lover. Something had happened to

prevent his coming. He would explain it soon. Thus she

thought; but she could not help feeling a shade of apprehension as

to the cause which detained him. It was no light thing—of that

she felt sure.

Nothing was said by either her sister or her brother-in-law

on Lydia's return. Mary, indeed, knew nothing. It was

not her husband's policy to tell her anything of his business

matters, and he did not wish to tell her about Isaac's affair just

yet, not until he was safe in prison, and till he meant her to

communicate the intelligence to Lydia at once. A few days

passed—the days before Isaac's imprisonment—and Lydia waited

impatiently for tidings of her lover. But none came, and Lydia

went through a hundred phases of disappointment and apprehension,

but not of distrust. The true-hearted girl felt it impossible

to doubt her lover's truth. She would have gone again to the

trysting-place, thinking that he might have mistaken the day; but

she knew he would not expect her there, for day and night the rain

had poured almost without ceasing. The valley was a quagmire

the moor would be a bog. Why did not Isaac write to her?

Was he ill? Should she go to his mother? She had almost

made up her mind to the latter course, which indeed she would have

followed at once, but for the feeling that she had received her

coldly, when one evening Mary followed her upstairs to her room,

with a face white with agitation.

"What is wrong?" asked Lydia, at once. "It is about

Isaac," she added. "It is about Isaac you have to tell me.

Oh, be quick," and she wrung her small, impatient hands together.

"Isaac is in prison," sobbed Mary.

"In prison!" exclaimed Lydia, in a tone of relief, hardly

realising what it meant, having expected to hear, "Isaac is dead."

"A bankrupt, and in prison," repeated her sister.

"Then he has done nothing wrong," said Lydia, quietly.

"Oh, I do not know," said Mary. "George seems to think

there is something wrong."

"Does he?" flashed from Lydia; but she caught herself up

before she had said another word—a word that would wound her sister.

"Good night, Mary," she said. "I am glad you told me, for I

feared worse than this."

"He did not meet you that evening, then?" faltered Mary,

inquiringly.

"No, be did not meet me," she replied.

"Oh, Lydia!" Mary was going to say that surely he would

have done so if innocent of all save misfortune. Poor Mary!

She had to believe in endless possibilities of wrong-doing that she

might retain for her husband any respect as a man among men.

But Lydia stopped her abruptly, and with a swift, searching

question,—

"Do you know who did this?"

"Did what?" asked Mary, innocently.

"Put Isaac in prison."

"No," replied Mary. "George did not say."

Then Lydia kissed her and sent her away, holding the light

for her over the stair rail; and when she had seen her enter her

room, returned to her own and sat down to think.

Lydia had a clear head and knew something of business.

She had heard it discussed all her life. Isaac had made his

affairs quite plain to her, and she failed to understand what could

have brought about such a disaster. He must have been wronged

in some way, that was the conclusion she came to, and the resolve

that followed was to go at once to his mother and learn all about it

and then seek Isaac himself. She sat musing till bitter became

sweet, as her heart went out to him in defeat and humiliation, more

tenderly than it had ever done in the pride of his simple, noble

manhood. At length she betook herself to prayer, and last of

all to sleep. On the morrow, saying nothing of her resolution,

and putting on a cheerful face, with a consciousness that she was

watched by both George and Mary, she waited till the former had gone

away, and then set out to visit Isaac's mother.

Early as it was Mrs. Benton was not alone. A pretty,

fair girl was waiting wistfully on the worn old woman, whom these

last few days had shaken as an October wind shakes the woods.

She looked thin and sere, almost deathlike, and she rose tremblingly

to meet Lydia, and holding by the table for support.

Mrs. Benton neither spoke nor offered her hand as Lydia

advanced.

Little Rachael, timid and tender-hearted, went away and took

refuge in the kitchen and cried.

With gentle force Lydia took possession of one of Mrs.

Benton's hands, and setting her in her chair knelt on the floor

beside her, and looking up at her with swimming eyes told her of her

recent knowledge. Large-hearted Lydia recognised that this

grief was more the mother's than her own and said so, but claimed

her portion.

But Mrs. Benton refused to look into the sweet pure eyes,

enough to beguile a saint, she averred. She withdrew her

trembling old hand, and coldly asked the kneeling girl why she came

there to insult her sorrow.

"Surely, I have a right to help you," said Lydia, boldly.

"He has done nothing to deserve this, I feel sure."

"It would have been better to have hindered it," said Isaac's

mother.

"Hindered it!" repeated Lydia; "how could I have hindered

it?"

"It is your brother's doing," said Mrs. Benton.

Lydia sprang to her feet. The sweet grey eyes had fire

behind them, and flashed almost fiercely. "He must be mad,"

she muttered to herself. "Mrs. Benton, I will settle the claim

immediately."

"My son will settle all claims himself, Miss Best," replied

the old lady, stiffly. "I am sure he would decline, as I must

do for him, any help of yours. My son has suffered a great

wrong at the hands of your brother, and he could not accept the

righting of it from you."

"I will go to him," said Lydia, eagerly; "he knows me better

than to suppose I have any hand in this."

"I request that you will be good enough to stay away from my

son. He could not bear to see you now. He will soon be

out of prison by the sale of his effects, and then he may perhaps

see you before he leaves the country."

Lydia said no more. She could not trust herself to

speak. Thus repulsed, she bowed and turned away. But

Mrs. Benton caught a look of such anguish on the bright eager face

that she relented and held out her hand. "What is done cannot

be undone," she said. "My son's life is blighted; but I think

he would be glad to hear that you grieved over it."

The words broke Lydia's heart, and the two women wept

together, and even Mrs. Benton felt that Lydia's tears were more

than little Rachael's, crying in the kitchen by herself.

Outside Mrs. Benton's house, Lydia came to a standstill.

The revulsion against her brother-in-law had reached a climax.

She felt that she could not return to his house, even for her

sister's sake. She passed the station; a train was going

homewards shortly, and, impulsive in all her actions, Lydia resolved

to go with it. So she went into a stationer's shop, and wrote

a note to Mary, saying that she had gone home, and sending it by

hand, got her ticket and was soon off on her twenty miles' journey.

She had done it all so quietly that no one who saw her could have

guessed the pent-up passion which ruled her.

It got worse in the train, as she had a compartment all to

herself, and the rapid motion favoured concentration. When she

arrived at Coalfield it was at white heat. Avoiding the

streets, she took the path by the river which led to her sisters'

house, and by this time the passion had stamped itself on her face,

which was pale and tense with excitement.

As she hastened along, she was stopped by a gentleman going

in the other direction. He had been lumbering along with a

pensive look in the eyes that hid deep beneath the overhanging

brows; but he brightened at Lydia's approach, and went forward

eagerly to meet her. Lydia had been a favourite of his from

the time when she had sat upon his knee when he was a youth at

college.

"Lord A—!" she exclaimed, in a startled voice, startled

simply out of her intense concentration.

"Is anything wrong, Miss Best?" he asked, with quiet concern,

when he had seen her face, which he could not do at a distance,

owing to his short-sightedness.

Lydia had not had time to make up a face, a thing which she

was by no means clever at. Lord A— saw the extent of her

agitation, which made her for the moment speechless. It moved

him strangely.

"Take my arm," he said gently, and, turning, walked off with

her. "I have heard of your engagement," he said presently.

It was like him to know: he always did know what was happening to

the people about him from that boyish time when he kept account of

Lydia's dolls, and generally was found correct.

"It is broken," she murmured.

"Why? My informant spoke highly of Mr. Benton; indeed,

I knew him myself, and liked him extremely. He was manager

under Mr. Raleigh."

There was the slightest possible hesitation in pronouncing

the name, but Lydia caught it. She knew what was in his mind,

and burst forth with her story. "And he was unworthy of your

generosity," she began. "That man to whom you forgave so great

a debt, for a far lesser one, and one honestly incurred, has thrown

Isaac Benton into prison."

"What could have been his motive?" said Lord A—, when he had

heard the whole; but he made a shrewd guess at the answer. "I

parted with Isaac Benton," said his lordship, "because I suspected

that he knew or guessed the cause of Raleigh's dismissal."

"If he knows, he has never breathed the suspicion of his

knowledge," said Lydia. "I would answer for him in this, as in

everything else."

Lord A— was looking down on her face; as child and woman it

had had an infinite charm for him. A look of longing darted

from the hidden eyes. Then he said calmly, "I should be glad

to have Mr. Benton back again."

"He is going to leave the country," said Lydia.

"Will you leave the matter in my hands, Miss Best?" asked

Lord A—.

She looked up at him inquiringly.

"Take no further steps," he explained, "and mention it to no

one outside your own family." They were at the door of her

sisters' house—the garden door, which stood open. Lydia

acquiesced, and they parted with a warm handshake; Lydia to pour

forth her trouble anew to her sympathising sisters, and Lord A— to

act.

He went straight home, tramping over the fields, with eyes

fixed on the ground, entered his library and stood straightway at

his desk. Half an hour after a letter to George Raleigh was

lying on the marble slab in the hall at Coalfield House, and a post

later it had reached the hands of him for whom it was intended.

The letter was a strange one. It contained the

following quotation, with Lord A signature:—

"Then the lord of that servant was moved with

compassion toward him, and forgave him the debt. But the same

servant went out, and found one of his fellow-servants which owed

him an hundred pence. And he laid hands on him, saying, Pay me

what thou owest. And his fellow servant with besought him,

saying, Have patience with me, and I will pay thee all. And he

would not: but went and cast him into prison till he should pay the

debt. So when his fellow-servants saw what was done, they were

very sorry, and came and told unto their lord all that was done.

Then his lord, after that he had called him, said unto him, 'O, thou

wicked servant, I forgave thee all that debt, because thou desirest

me; shouldst not thou also have had compassion on thy

fellow-servant, even as I had pity on thee?'" (See Matt. xviii.)

There the slightly abridged quotation ended. But George

Raleigh had no need to consult the original for the conclusion of

the story, and abject fear took possession of his mind for a moment;