|

YES OR NO?

――――♦――――

CHAPTER I.

"THERE are no

strangers here, Frank," said Miss Smith, advancing to meet her

nephew, who had come in "promiscuously" to dinner. "You know I am

seldom entirely left to myself. Miss Field, my nephew Mr. Smith;

Miss Norman and Miss Oliver you know already."

Mr. Smith made his acknowledgments all round.

"You will take Miss Field down to dinner," was Miss Smith's next

intimation; and her nephew bowed once more, and regarded his aunt

with a twinkle of humorous meaning in his grey eyes, as he took his

place by the young lady's side. He meant to intimate his

satisfaction with the companion allotted to him; for he was apt to

be rather severe upon his aunt's special friends.

Miss Norman, he said, was as tall as a Norwegian pine tree; and so

sentimental that he expected some day to be wrapt in an embrace

which would crush him for ever. And he had an unusual aversion to

her friend Miss Oliver, who wore shirt-collars and a tie, a vest and

a velvet jacket, in short made the upper part of her person as

sternly masculine as possible. She patronised him, he said, as "only

a poor devil of a young man;" and he in revenge named her "The

Hybrid," and said a mermaid would be more respectable, &c. &c.

Miss Smith was one of the pleasantest and most unworldly of women of

the world. She was not young, and yet she could not have been

thought of as old.

Her hair, which had once been red, was grey; but her face was fresh,

and her short-sighted eyes clear as a young child's. Her heart was

fresh, too, in spite of the world and its ways; and she was a

well-known friend and helper of the workers of her own sex. Indeed,

she kept open house for them.

On the present occasion Mr. Frank Smith found his companion just a

little difficult to get on with; she had none of the light swift

talk to which he was accustomed, and which saves all trouble of

thinking.

He tried her with the opera and the theatres.

No response.

She lived in the country, then?

No, she had always lived in London.

The Royal Academy's exhibition had just opened. She had seen the

picture of the year?

No, she had not seen it. Did he remember so and so, a picture of

last year?

The idea of remembering a picture of last year fairly overcame

Frank. He had exhausted all the topics people take up to keep them

from knowing anything of each other; and their conversation would

have come to an untimely end before their soup if it had not

suddenly become personal, and therefore interesting.

The change was due to Miss Norman, who bent over the table towards

Miss Field, and asked if she belonged to the women's party.

"I do not belong to any party," was the answer given with perfect

sweetness, and yet with decision.

Miss Norman would thereupon have begun a convincing argument, but

Miss Oliver interposed by the introduction of another topic, passing

over Miss Field as evidently not worth powder and shot—an ordinary

young lady, in fact.

"So you are not a Woman's Rights advocate," said Frank, under cover

of a change of plates, and the rapid and loud talk of Miss Oliver.

"I am glad of it; I can't bear the way in which girls go on

nowadays."

"Were they very different when you were young?" asked his companion,

archly.

"One used to be quite safe if a lady was tolerably young and pretty;

but now the very youngest and prettiest will attack a fellow in the

terrific way. I am not so young as you may suppose," he added;

"people live fast in this generation. If I go away for a year or

two, I find everything changed when I come back."

"Do you go abroad much?" asked Miss Field.

"I have to be a good deal away," he answered.

"One can't live in England on less than two thousand a year."

"I think it might be managed," said his companion, laughing. "And

where do you go for economy's sake?"

"I take a run over to America, or a trip to Ceylon. One year I had a

race round the Arctic Circle, and I think I shall give the Antarctic

a turn next."

"It must be very interesting," said Miss Field, simply.

"I don't know that it is," he answered; "one loses one's interest in

the game at home here. The players are changed, and you are

nowhere."

"You are dreadfully discontented, I fear," said Miss Field.

"Oh, no; the worst of it is that I am growing quite contented. I

used to be awfully the reverse, and you know discontent has been

exalted into one of the cardinal virtues of our day. I am learning

to eat, drink, and be merry; in short, I am becoming one of the

Epicureans. Aunty has tried to make a Stoic of me in vain." He

nodded gaily in Miss Smith's direction.

"What is that you are saying about making a Stoic of you?" she said,

having caught the tail of his sentence.

"Miss Field has been telling me that I am dreadfully discontented."

"Miss Field is quite right. It comes of having nothing to do,"

rejoined Miss Smith.

"There are not many things worth doing in the world," said Frank.

A shade passed over the face of Hyacinthe Field, a shade of

disapproval. He saw it. "You have not lost your interest in things

in general?" he said.

She smiled. "Hardly," she replied. "I have not even begun to be

interested. When I tell you that I have never travelled beyond

Margate or Brighton, and never was at anything more advanced than a

children's party, you will understand."

Frank paused for a moment. "I wish aunty would let a fellow know who

he is to talk to, if she will have people unlike all the rest of the

world," he thought. "I wonder, now, if she has set me to dine with

her dressmaker."

"Pardon me," he said; "but I really could not make you out. You did

not look stupid—"

"Thank you." Miss Field laughed.

"And yet you seemed to know nothing, or to have nothing to say on

ordinary subjects."

"I have had to teach as fast as I could learn," she answered. "I

have had time for nothing else."

So she was a teacher.

"Don't you find it a dreadful bore?" said Frank.

"Teaching! No," she replied; "I like it exceedingly."

"But it is very hard work," said Frank, "is it not?"

"I dare say you work quite as hard at doing nothing."

"That is true," he replied. "We make pleasure our toil, and then

turn for relaxation to the primitive pursuits of the savage; but

then we do get bored extensively."

"Why not try some serious work, then?

"What would you advise me to try?" asked Frank.

"That I cannot say; and it does not so much matter about the kind of

work, as the way of doing it."

"How so?"

"All real work is good; how good for you depends upon the amount of

spirit you can put into it."

"But what if it was something I could not put spirit into, as you

express it?"

"Then it wouldn't be real work; you had better leave it alone."

"What is real work?"

"Anything that wants doing; anything that will make men's lives

freer, fuller, stronger, wiser. Surely that is wide enough; surely

there is enough to do."

Frank Smith stole a glance at his companion. Yes, she was on the

affirmative side of things, hence her freedom and dignity and charm.

The three other ladies were discussing a severe article on "Wives."

"It's only old fellows who can marry," struck in Frank. "Women

require so much in the way of settlements, establishments,

allowances, and what not, they won't have anything to say to a

fellow unless he is rolling in riches."

"There are surely some disinterested women," said Miss Norman,

pensively.

"Oh, yes," said Frank. "A friend of mine fell in love with a young

lady who was disinterested. She loved him in return; but at the

eleventh hour she threw him over in favour of a richer party. She

still loved my friend, but the other's wealth and position would be

such a gain to her cause that she felt she must sacrifice herself."

After the ladies retired Frank sat and meditated over a glass of

port. He was just then alone in London, left to his own resources; a

young fellow with nothing to do, and not knowing what on earth to do

with himself.

Should he go up-stairs, and spend the remainder of the evening with

his aunt?—that meant with Miss Field. He had found his conversation

with her uncommonly pleasant—almost as pleasant as if he had talked

to a companion of his own sex. And his old companions of Harrow and

Cambridge were fast failing him; one, after another going off in

pursuit of their careers, or, in spite of what he had said, getting

engaged and married.

He had belonged to a good set at school and college, not studious,

yet not dunces; men who as boys had imbibed a love of veracity and a

hatred of sham, which was to them a religion, and who were carrying

that religion into their various spheres.

The pity was that Frank had no career. He was to be a country

gentleman pure and simple—and here he was, at six-and-twenty,

dangling about London, with an occasional dash at the four quarters

of the globe; waiting for his inheritance, in possession of a man

not twice his age, and likely to live as long again. Frank had only

just begun to see his position in its true light. It had not a

little to do with his discontent.

But what had to do with it still more was his feeling of the general

purposelessness of existence. On the one hand, men toiling for

nothing more and nothing better than the power to toil; on the

other, men living in pleasure, and utterly dead to it. What weary,

dreary work was that "society" of which he formed a unit! What a

stupid monotony it was, with all its refinement of detail! Was there

any worth, or any meaning, in its comings and goings, sayings and

doings? No, and he knew that the answer was echoed by thousands,

"No, no, no."

He sat there toying with his wine-glass, and feeling very much

inclined to go up-stairs and see how that young lady with the cool

clear eyes was getting on. He had seen brighter eyes by the score,

eyes as blue as the rifts between the clouds of June—he could not

tell what colour hers were of—eyes large and dark and melting as a

fawn's, and as innocent of meaning; but none with such an out-look

of sympathy in them, none that seemed to invite such utter

confidence and trust.

Then he remembered that her black dress was close up to her throat;

but that the throat was white as lilies, and bent with a peculiar

tender grace.

He rose with a tremendous yawn, stretched himself, holding on to the

back of a chair, and finally pushed his hands through his chestnut

locks, and opened the dining-room door.

His foot was on the stair, but he turned back, took his crush hat

from the table in the hall, buttoned on his great-coat, and went

out for the evening.

The life of Frank Smith was an utter negation of duty; it was an

utter negation of religion too. The one follows the other of

necessity; though that is not always apparent, Frank took care to

make it so.

Frank's father and mother were formalists; and from feeling the

hollowness of the form without the spirit, Frank had come to despise

the first altogether. He had had frequent disputes with his father

as to the desirability of attending the parish church when he

favoured them with his presence at home, disputes which contributed

to keep him away from it. "Look at your brother Gilbert," his father

would say; "I have no trouble with him." And in his heart Mr. Smith

regretted that Gilbert was not the elder and the heir.

Gilbert had just been called to the bar, and was idly busy attending

in court and chambers, waiting for practice. But it was likely to

come, for the young man was clever, and had application and

decision. He spent the week in chambers, and came down to his

father's every Saturday, going back by an early train on Monday, Wanock Place being within easy distance of the metropolis.

Gilbert went to church with his parents and his sisters; he could

not understand how any one could refuse assent to its doctrines, or

compliance with its forms. He had gone to church since he was three

years old, and he never thought of asking himself where were the

results of it. Did he not live soberly and righteously in this

present evil world, and was not that enough? Godly too, since he

acknowledged God in His public worship. But he never thought of

condemning himself because, while he sat apparently listening to the

sermon, or even to the service, he was going over a case in his

mind, or had his heart filled full of that covetousness which is

idolatry.

There was little more than a year between Frank and Gilbert Smith,

and from their very infancy they had been the closest companions. They had learnt the same lessons, enjoyed the same pleasures, and

generally shared the same troubles, and fallen into the same

scrapes. As they advanced into boyhood, it was Frank who got into

the scrapes, Gilbert who got out of them. It was Frank who neglected

his lessons; it was Frank who was careless or intractable. He

certainly was the more faulty of the two; but whether from a greater

proclivity to faultiness, or from his far less cautious and guarded

temper, was a question. Gilbert was smoother, readier, cleverer than

Frank, and gained golden opinions as he grew up, from school and

home authorities.

Their home was not a religious one, neither was their neighbourhood. The church planted there had a name to live, and was dead; but there

are not many in a Christian land who, at one time or other, do not

hear the call of God. Frank and Gilbert Smith had a tutor who was

heart and soul a follower of Christ. It fell to him to prepare them

for Confirmation and Communion, and he laboured earnestly to make

the sacred season the turning-point of their lives. One of the

illustrations which he made use of was to set life before them as a

solemn "Yes or No." It was from a lesson on the two sons sent to

work in the vineyard. Life, he told them, must be either a true

affirmative or a terrible negative. Are you on truth's side, right's

side, God's side?—yes or no?—was being asked and answered in every

event of life. "Son, go work to-day in my vineyard," was God's call

to each. And one said, "I will not," and afterwards repented and

went. And he came to the second, and said likewise; and he answered

and said, "I go, sir," and went not. The story showed that a mere

assent to the truths of religion counted for nothing—that such an

assent was indeed of the nature of a lie. And this lesson so

impressed itself upon Frank, that force had to be put upon the boy

to make him accept of Confirmation. He had never forgotten it. Most

studiously he kept himself from any profession, and allowed himself

rather to be counted a reprobate than to take the name of Christian. By many he was considered a sceptic, but scepticism was not the tone

of his mind, not even the easy scepticism, alas! too common, which

never felt a doubt because it never entertained a belief. On the

contrary, he was haunted by an uneasy belief, an unwilling reverence

for truth, which he put aside because he desired to have his own

will and his own way in the world.

And he had had it, and it had made him what lie was, profoundly

discontented, slightly self-indulgent, and utterly restless and

unsatisfied. He had followed Pleasure in her fairest paths; he had

never descended into vice. Descending into vice, as society was

constituted, was as much living a lie as professing Christianity

would be. What he could not do openly he would not do at all. Never

had Pleasure a more sincere and eager votary, a votary, too, with

out reproach. He danced after her bubbles, and caught them before

they fell, in all their prismatic splendour; he chased her

butterflies, and captured them with their wings untorn. But the

bubbles broke, and the butterflies were not worth the keeping. Society was a carpeted treadmill, a crowded childish merry-go-round. A feeling that he was becoming perfectly fatuous, quite as often as

exhaustion of the purse, sent him driving over the globe. Well, that

too was only a huge merry-go-round; he came back to his

starting-point no whit the better. Very likely the next phase of his

existence would be, as he anticipated, one of pure self-indulgence—a

good dinner, a first rate club, a choice volume, and a genial

companion.

Gilbert's career had been the opposite of all this. He had stayed at

home, he had been a diligent student, he had taken honours; he had

read for the Bar, and been called, and waited patiently for

practice. He had an honourable ambition to succeed in his career. He

was in short all that was exemplary in practice, and he had without

scruple professed Christianity ever since he had taken his place

readily and reverently at the rite of Confirmation.

He, too, had long remembered that time, and its heavenly lessons. Some day or other, he often said to himself, he would begin in

reality to serve God, to keep his youthful vow, the vow which he had

taken on himself, to be Christ's faithful soldier and servant to his

life's end. But of late he had said it to himself less often;

indeed, he had begun to excuse himself. He had been too much

occupied, engrossed almost, by his worldly calling. And if there

arose, in his clear and subtle understanding, the answer that his

worldly calling was indeed a part of his service, and that it needed

but the dedication of that to its highest uses, he turned

impatiently from the suggestion. His life was more satisfying,

perhaps altogether nobler and better, than; but even for that reason

all the more dangerous, seeing it led so much more surely to earthly

gratification.

CHAPTER II.

TWO months had

passed away, during which Hyacinthe Field had worked on with no

relaxation, save an occasional visit to Miss Smith. Her work

lay at the houses of several members of Parliament, whose children

she taught, and in the Parliamentary season it was very severe.

One evening, when she called on her friend, Miss Smith noticed a

tiresome little nervous cough, and then, remarking how pale and

wearied she appeared, had insisted on her going down to the seaside

with her as soon as she was released.

The "Retreat," to which Miss Smith carried Hyacinthe, was a

house that had been built by her father on the Sussex coast.

It was tenanted by no one in particular, yet it was seldom

uninhabited for any length of time. A set of old servants were

kept there, and somebody or other was always running down to the

cottage, as they called it, for a week or a fortnight.

It was an unpretending, two-storeyed house, set back a little

from the cliff, in one of those soft, sheltered, cup-like hollows

into which the chalk dips over the downs. Round it had been

planted a walled garden, which half a century of care and culture

had made a wilderness of bloom and fruitage. All around it

stretched the green treeless turf. It gave one a sense of

shelter, and yet of space and loneliness, which at once refreshed,

and invigorated, and soothed.

"My nephew, Frank, comes here," said Miss Smith, "whenever he

is particularly disgusted with the world."

They were sitting down just then to their first dinner in the

pretty dining-room, in at whose windows peeped a perfect crowd of

roses, while beyond a terraced lawn ran down to the ivied wall, over

which was seen nothing save sea and sky.

Miss Field sat opposite to the windows, in the dreamy state

which comes with repose and enjoyment after fatigue. Though

the room was plainly furnished in oak, and the greatest simplicity

prevailed in its appointments, everything was pure and fresh and

sparkling. The table was adorned with flowers from the garden;

fresh grapes and peaches were set on the sideboard; the white

curtains of the windows fluttered with a light breeze blowing from

the south and from the sea, and the room was filled with the mingled

perfume from within and without.

Miss Smith, looking at her young companion, was satisfied

that she felt it good. It was Miss Smith's religion, and not a

bad one either, that people should pronounce life good.

Suddenly she saw Hyacinthe's look of dreamy enjoyment give place to

one of swift surprise; but she did not perceive the cause till a

hand was laid on her shoulder, and her nephew's voice at her ear

said, "Well, aunty, how do you do? I did not know you were

here; but you'll take a fellow in for the night at least."

He had come in at the window, with a silent bow to Miss

Field, and did not seem fearful of trying his aunt's nerves.

She used to say she was born before nerves came in fashion; and she

turned on the intruder an undisturbed countenance, and said, "Speak

of a certain gentleman, and he's sure to appear."

"And what were you saying, may I ask?" said Frank.

"That you always come here when you are particularly

disgusted with the world; that is, if you are not at the antipodes,"

said Miss Smith. "Where have you come from now?"

"From home. I have walked over;" and he exhibited a

sort of knapsack strapped on his broad shoulders. He might

have come a hundred miles in that fashion.

"Make haste, then, or the dinner will be spoiled," said Miss

Smith.

"I'll be down in a minute," said her nephew, hastening away;

"but don't wait for me."

Miss Field had seen nothing of Frank Smith since the day when

she first dined at his aunt's, except a glimpse which she caught of

him on one occasion leaving the house as she was about to enter it;

but during the next fortnight she was destined to see more.

Miss Smith had one hobby in addition to woman's work; it was

water-colours. She believed that she might, could, would, or

should be a great artist, and she painted many pictures, and sent

some to the newly-instituted Female Artists' Exhibition.

The next morning when she and Hyacinthe, accompanied by

Frank, went out together, Miss Smith discovered in a particular view

of a little inlet, with its white cliffs and green slopes, its blue

water and snowy sea-gulls, the materials for a great composition.

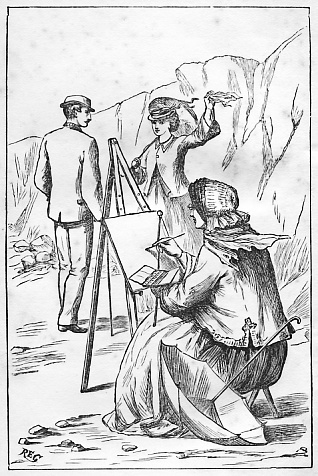

"The following day she brought her portfolio,

and began to sketch."

The following day she brought her portfolio, and began to

sketch; and Hyacinthe and Frank were told to walk on, and come back

for her at their leisure.

This sketching and walking became part of the daily routine

into which they fell, for never another word did Frank say about

going away. Skirting the breezy cliffs, he and Hyacinthe

walked together for miles over the short springy grass of the downs,

treading out the scents of the wild thyme, scattering the white

sheep by descending into their favourite hollows, or loitering by

the cliff's edge to watch the white gulls floating in the sky as if

it were another sea, and skimming the sea as if it were another sky.

Then they went back regularly, and picked up Miss Smith and

her sketching materials, and returned to lunch at the cottage.

Then into the shady back garden, full of the scent of ripening

fruit, to sit on a rustic seat and read. After that, dinner.

Then out again to saunter over the cliffs, or down on the beach till

the sun dipped in the waves.

Thus it was every day with wonderful monotony, for even the

weather never changed in those rare weeks of sunshine; and, more

wonderful still, Frank Smith forgot to feel weary of the monotony.

They did the same things over and over again; but it was with a

subtle difference, which made each day sweeter and sweeter, as if

advancing to some culminating bliss.

Did Frank know what he was doing in those days? Hardly.

Five years before he had fallen in love with a friend of his

sister's, and he had had enough of it on that occasion. As a

burnt child dreads the fire, susceptible Frank held aloof from the

tender passion; and he had come to believe—thanks to that young lady

and to others like her—that women can stand a good deal more "of

that sort of thing" than men can.

It was not on this score, however, that he felt himself safe

with Hyacinthe. It was that she did not lay her herself open

"to that sort of thing" at all. She had evidently not yet

learnt the very alphabet of flirtation. And he judged rightly.

No eyes had ever looked into hers with a lover's gaze; no lips less

sacred than her father's had ever touched the bloom of her cheek.

And yet Hyacinthe was twenty, and far more of a woman, in body and

soul, than the girls who had drawn Frank's eyes with their own and

dangled their charms before him. He did not consider that this

girl's perfect maidenliness was far more dangerous both to him and

to her.

One morning the wind drove them from the cliff. They

had not felt it in the hollow, and had gone out as usual. Miss

Smith's white umbrella was soon flying across the Channel, and

Hyacinthe's hat was on the point of following, but was held on by

Frank. Clinging together, the three soon reached shelter once

more, and indulged in a hearty laugh at their disaster.

That afternoon for the first time Frank expressed a wish.

It was for a horse. "What a day for a gallop!" he said.

"Do you ride, Miss Field?"

"No," said Hyacinthe "I never was on horseback in my life.

But I have often thought it must be the perfect poetry of motion.

A trot seems like a metrical romance; a gallop, like a grand rapid

ode."

"'A horse! a horse!"' shouted Frank; "two horses! Miss

Field, you shall ride." And he went off at once, and sent a

note to the little town lying three miles off under the cliffs.

He had ordered horses for the morrow.

On the morrow the two horses appeared, with a groom mounted

on a third. Poor spiritless creatures they were, Frank said;

but that might be none the worse for Hyacinthe. Miss Smith

looked on approvingly through her double eyeglass, while Frank

walked Hyacinthe up and down in front of the house, and then tried

her by a canter round and round.

She stood the test, declaring it was even more delightful

than she had fancied. So away they went over the downs, though

Frank took care to pick their way, and keep close to Hyacinthe's

bridle-rein.

They got into a road at last—a white, even road, winding down

from the sheep-walks to the cultured farms of a lovely valley.

Up the centre ran a lower ridge, bearing three windmills on its

back. Frank told his companion their history. She

admired more than one grey farmhouse, set in its gay garden, and

flanked by its sombre ricks. He knew the tenants of each.

At length they entered and rode through a pretty village, and were

saluted by every man, woman, and child.

When Hyacinthe remarked this, her said companion said simply,

"We are riding over my father's land. And there come the lot,

I declare!" he exclaimed, as a carriage appeared coming up the road

to meet them. "My mother and sister," he explained, "and a

couple of visitors."

The carriage advanced, so did the riders, and at last they

met, wavered a little, and then stood still. Frank's mother

and eldest sister were in the carriage, and also their cousin, Ethel

Belfrage; but the seat of honour beside Mrs. Smith was occupied by a

stranger, a young lady to whom Frank bowed ceremoniously. A

younger sister was behind on horseback.

"Why, it's Frank!" cried the latter, as she rode up.

"This is Miss Field, a friend of aunty's," Frank was saying.

Mrs. Smith acknowledged the introduction stiffly. The

young ladies with her did not feel called upon to acknowledge it at

all; but Frank's favourite sister held out her hand, and said, "I'm

glad we met you; I don't admire riding alone after the carriage."

"And where are you going, may I ask, Flo?" said Frank.

"We were going to look after you, sir."

"We intend driving over to lunch at the cottage," said Mrs.

Smith. "Perhaps you will turn back with us."

"Very well," said Frank; and the riders performed a flank

movement, and got into the rear of the carriage. The carriage

moved on, and Frank and his two companions rode abreast behind it.

While they were executing this movement, Frank had his hand

on Hyacinthe's rein, a fact which did not escape the notice of his

mother. The younger ladies were also looking on, the stare of

well-bred insolence in their eyes.

"Do you know who she is at all?" asked Miss Smith of her

mamma.

"Not at all," replied Mrs. Smith, irritably.

"I never met her anywhere," said the young lady at her side,

in a particularly thick, coarse voice.

"One of aunty's friends," rejoined Miss Smith. "Aunty's

friends are not usually so dangerous-looking."

"Do you think her handsome?" drawled Ethel Belfrage.

"Yes; don't you?" replied her cousin, who was very pretty

herself.

"She has no style," remarked Miss Ponsonby; "looks a mere

nobody."

"And did you notice she had not on a habit?" put in Ethel.

"I dare say she is some teacher or artist whom aunty has

picked up," said Miss Smith.

Meanwhile, perfectly free from envy, hatred, malice, and all

uncharitableness, the three enjoyed their ride.

Instead of following the carriage, which went round by the

road, they got upon the downs again; and though they could have

reached the cottage sooner, the occupants of the carriage had been

seated in the drawing-room at "The Retreat" some time before they

made their appearance. Mrs. Smith had time to become yellow

with vexation, and Miss Ponsonby to give herself up to an

overwhelming desire for lunch, and poor little Ethel Belfrage to

lose her faint roses and look the picture of weariness, before they

arrived, radiant with good looks, good temper, and hearty enjoyment.

"You are perfectly boisterous, Florence," reproved Mrs.

Smith.

"It's the wind, mamma—you know it always makes me laugh,"

replied Florence; "and we had such fun trying races on 'One Tree

Tip.' Miss Field's horse was most amusing; we have named him

'The Camel.' He gives the queerest lurches, and looks to his

footing as if he expected to tread on quicksand."

"It was quite as well for me, perhaps, that he was such a

careful old fellow," said Hyacinthe. "It was a rather

hazardous experiment, racing over the downs mounted for the first

time."

"You don't mean to say that you were on horseback for the

first time?" said Mrs. Smith.

"Yes, indeed," said Hyacinthe, smiling.

"I am glad I was not aware of it before," returned Mrs.

Smith. "If there is anything I fear, it is a bold, bad rider."

"Miss Field is a born rider, mamma," cried Florence;

"half-a-dozen lessons would make her perfect."

But Mrs. Smith deigned not the slightest further notice of

Hyacinthe. The party proceeded to luncheon, one half bright

and happy, the other moiety dull and disagreeable. Not that

Miss Ponsonby felt any longer aggrieved; an excellent luncheon had

been laid on the table, and to that she was devoting herself

heartily. By the time she had got through her third plateful

and her second glass of wine, she would be perfectly satisfied with

herself, and with the world in general. She was a large,

handsomely-made woman, of no more than five-and-twenty; but her face

was positively repulsive from its desperate animalism. You

never noticed her forehead, nor yet her eyes; they were very small.

What impressed you was the beak-like nose, the great jaw, the wide

under lip, the enormous chin and throat. The upper lip was

short, and the ears fine. There was an unmistakable air of

breeding about her carriage; but nothing could redeem her from

looking what she was, a sensualist of the coarsest type. That

was what some generations of donothingism had made of Miss Ponsonby.

Poor Miss Ponsonby! Frank called her "The Ogress," and

had run away from the prospect of dining with her daily. And

this was the lady for whom, because she was rich and well-born(?),

Mrs. Smith intended her eldest son.

"I think you might come home with us now, Frank," his mother

had said to him.

But Frank shook his head, with a meaning which Mrs. Smith did

not fail to comprehend.

"All in good time," he replied, not too respectfully, "Miss

Field will be gone the day after tomorrow."

Miss Field was not invited to Wanock Place.

It was Hyacinthe's last evening at "The Retreat." She

was going home to her mother and sister, to their humble lodgings in

the heart of London. Frank and she went out together for a

last stroll on the beach. The tide was far back, and they

meant to go beyond the utmost limit of their former walks, in order

to get under the highest point of cliff within reach.

"We must take care to be back before the tide comes in

again," said Hyacinthe, when they had descended to the sands, and

were fairly on their way.

"Let us go out a good way first, and avoid the windings,"

said Frank; and so they went out over low rocks, covered with

slippery seaweed, with spaces of grey rippled sand between—out till

they came to a belt of shingle, where they could walk firmly and at

ease. The sun was behind them; they were close to the water's

edge, and walking where the waves had been an hour ago, in a perfect

solitude. The clouds that rested on the ocean's verge had the

lines of the heliotrope, transfiguring light and mystic shadows were

about them. Was it wonderful that they were less inclined to

gaiety and more to tenderness than usual?

They reached the point for which they had started in ample

time, counting an equal time for return, sat for a little on a ledge

of chalk, and then set off home again; a long, dazzling track of

sunshine playing over the sea before them.

They loitered by the pools, poking up the little green crabs,

and looking at the floating many-coloured weeds. At length

Frank, looking seaward, said, "We must make haste now, the tide is

running in rapidly."

"I hope we are not going to have an adventure," said

Hyacinthe, quickening her pace, and cliff looking up at the wall of

some hundreds of feet above.

"No, there is time enough;" but they walked on a little too

briskly for talking. "We are just in time," said Frank.

"We shall get in without a wetting. This is the last point we

are turning."

"We have not left much of a margin," said Hyacinthe, as a

wave came seething to her feet.

"No, it was easier walking out there," he replied, and on

they went again.

There was nothing worse awaiting them than wet feet; but the

tide was in before they could reach the steps that led up the face

of the cliff, where it dipped. Close to them the low rocks

were still uncovered, and making his companion step on these, Frank

walked into the shallow water. There was a space between rock

and rock, and he gave her his hand. She sprang lightly over;

but he held it still, held it in a firm, detaining clasp, and by it

the one woman who could make life to him full of purpose and power

and beauty, who had restored his faith in perfect womanhood, and

called him to a nobler manhood.

Like the waves at his feet rose the swelling surges of his

warm Saxon blood; but they must down. This lady of his was worthy of

all observance, and not to be lightly won.

The last glittering ray died upon the water, the evening star

came forth, shades of inexpressible tenderness fell over sea and

sky. Silently he led her up the steps, and held her yet a few

moments, looking on the grand everlasting symbols whose meaning

cannot be uttered, and yet in moments such as these is felt in the

inmost soul. Then their eyes met for one brief moment,

revealing each to each, the man's passionate desire, the woman's

wistful yearning for a love that might never fail.

Then they fell asunder, as if by mutual consent, and walked

toward the house in pensive silence. Into the manner of each

had come a tender constraint. It was well, if they were to

part, that they were parting on the morrow, for they could never

have walked together again unconscious and at ease.

On the morrow Miss Smith drove Hyacinthe to the station;

while Frank, having said "Goodbye" in the presence of his aunt, and

frankly spoken his hope that they should meet again, took his

knapsack and set off to walk home.

It was Saturday. Gilbert Smith was at Wanock, and Miss

Ponsonby was gone. The ladies were out; the brothers met

alone. Frank, after his usual greeting, suddenly put the

question, "Do you think there is anything a fellow like me could

turn to?"

"What kind of thing do you mean?"

"To make money, you know," said Frank.

"There's money to be made at most things by time and labour,"

said Gilbert.

"I'm willing to work," said Frank.

Mr. Gilbert Smith, barrister, gave a prolonged whistle.

"What on earth has set you on this new track? " he inquired.

"Well, you see, old fellow, I'm leading the stupidest life

going; waiting for my father's death, that's about it, and God

forbid he should die. He's likely to live, I'm happy to say,

for half a century yet," said Frank.

"I wish you had thought of it sooner," replied his brother.

"You wouldn't care for the Church, else it would be easy to get you

a living."

"No, old fellow, that won't do," said Frank, promptly; "I

wouldn't care to sell my soul."

"There's the army, but you couldn't make money there; you'd

be likelier to spend it. There's physic."

Frank made a wry face, and shook his head.

"You're too late for that," added his brother, "and so I come

back again to law. It's easy to enter upon, it's dignified,

and it leads to a good many things besides—Government appointments,

commissions, and such-like. An active commission, now,

especially one that took you abroad, would be just the thing for

you."

"I don't want to go abroad though," said Frank; "I want to

settle at home. I've knocked about the world more than

enough."

"I didn't mean permanently," said his brother. "In the

meantime you can share my chambers, and I'll put you up to all I

can."

"Thank you, old fellow," said Frank. "There's one thing

I wish you would put me up to, and that's the length you make your

allowance go. I begin to think I must be a selfish beggar, for

I have never made my five hundred serve me, and you have got along

with two."

"Horses and club dinners," said his brother. "I dine on

a mutton chop, cooked and served by an old woman with but one eye."

"Better than dining for life opposite an ogress with two,"

laughed Frank. "You'll tell my father what I've been saying?"

he added. "Just put it in shape a little, you know."

CHAPTER III.

FRANK

SMITH began reading for

the bar with a wonderful burst of energy, which lasted, though

everybody had predicted that it would be over in a month. He

intended to work so hard and so successfully that his whole family

would be bound to declare in favour of his having his own way.

There was nothing to hinder his marrying Hyacinthe except her

poverty and his own. She was the daughter of a gentleman; and

if she was not, the Smith blood was not deeply blue. It had

become imbued with that colour in the course of generations, but it

was originally quite black, as Frank had often heard his aunt

declare. He intended speedily to confide in his father, and

then to address Hyacinthe herself; but for the present he was forced

to wait, for the means of communication were cut off. Miss

Smith had gone abroad in the winter with Ethel Belfrage, for whom a

thorough change had been prescribed, and Frank had no possibility of

meeting Miss Field in her absence.

The long vacation came again, and he was induced to join his

aunt and cousin on the shore of the Mediterranean. Under Miss

Smith's careless chaperonage, he now saw as much of Ethel as he had

seen of Hyacinthe; but then Frank had always been accustomed to see

much of Ethel, and that without any sort of harm coming of it.

Indeed, no possible harm could come of it, for Ethel had a fair

fortune, and stood second in the estimation of Frank's mother as a

match for her son; but it was for her second son that she coveted

Ethel, knowing as she did that Gilbert had always been fond of

her—how fond she did not know.

As for Frank, had he not walked beside Ethel's bath-chair

over the parades of half the watering-places in England, without

having the least impression made upon his stubborn heart?

Ethel did not make much use of the natural powers of locomotion

which she had in common with other mortals; she had always been

delicate, and disinclined for exertion, only it was quite wonderful

how much she could do under a sufficient stimulus—the stimulus of a

ball, for instance, at which she could waltz with Frank till his

stout limbs ached and his steady head reeled. True, she

suffered from reaction, which he never did, and she would lie on a

sofa in a nest of cushions for a week after such indulgence.

Poor girl, no one had ever taught her that she too might have her

use in the world, and might even yet train herself to the joyful

activity of the service of God. No one had ever said to her,

"This dance of pleasure is a feverish dream. 'Awake thou that

deepest, and arise from the dead, and Christ shall give thee

light.'"

Ethel Belfrage had fallen in love with her handsome,

good-humoured, idle cousin, and thought she would be well and happy

if she could only have him by her side for ever; and truly he might

have caused her to lead a more vigorous and wholesome life, at least

for a time, for without a nobler conception of life and its duties

than either of them possessed, they could but decline to its lower

levels. Ethel was not one who would keep alive on the altar of

home that heavenly fire of love which lights the way to labour and

to sacrifice.

And Ethel was really ill, ill with the nameless sickness

which seizes on fruitless lives. When she heard that Frank was

coming, she brightened up a little for the first time since she had

been taken abroad. Alas! Frank was only going because his

brother had spoken of doing so, and because he had not made up his

mind where else to go. Frank was always inclined to drift.

The mass of him, and he was a massive man, was not fully penetrated

with life; he was apt to be inert.

When it came to the point of departure, and Gilbert Smith saw

that his brother was really to accompany him, he backed out of it

himself. Ethel would not look at him while Frank was there.

He always thought, "One day she will turn to me, when she sees

Frank's indifference, and care more for me than she could possibly

care for him." With all his affection for his brother, he felt

for him a grain of contempt. He never guessed that his

brother's sleepy intellect was twice as great as his own, though not

half so active; that it was greater than he had ever given him

credit for, he had begun in those last months to perceive.

Frank went to join Miss Smith and Ethel alone, and then there

was nothing for it but to wait on the latter hand and foot.

Patiently and kindly he took to it, sauntering by her chair, finding

walks for her, finding rests for her, finding books for her, finding

talk for her, and relieving Miss Smith of what to her was grievous

boredom; setting her free to write, sketch, and gossip: for she

never went anywhere without finding somebody she knew.

And while Frank was thus engaged in the body, his thoughts

were far away, ever drifting faster and faster, and in fuller flow,

towards Hyacinthe Field and the time when he might begin to woo

her—that was, as soon as he saw that he could secure a fair position

by exertions of his own.

He stayed longer than he meant to stay, for dreaming was

sweeter than working, and beside Ethel he could always dream.

He was more attentive to her than he had ever been before, simply

because he was afraid that in his absorption he might be less so.

Ethel began to hope. She bloomed into new colour; she

gained new strength day by day. Nothing opened Frank's

obstinately dreaming eyes. He would as soon have thought of

marrying a cripple as Ethel. He had that kind of physical

aversion to sickliness which is natural to some people, and which

would have made him avoid her if a kind of brotherly affection and

generous pity had not mingled with it.

When at length he was going home in a yacht which a friend

had placed at his disposal, Ethel announced her desire to return to

England at the same time. There was accommodation enough in

the yacht for all three. Miss Smith, who was an excellent

sailor, had no objection to the project on her own account; but she

felt bound to deliver her conscience by warning her niece about it,

well knowing the suffering store for her if she persisted.

She did persist, however, in spite of the warning, and had

not been ten minutes on board when she had to be carried below.

Miss Smith was not self-denying enough to go with her, but left her

comfortably prostrate in charge of her maid.

For her sake, after a couple of days they put in at Ryde,

intending to take the steamer to Portsmouth, and so shorten as much

as possible the period of suffering to her. She had really

been very ill. When they were ready to land at the pier she

could hardly stand alone, so weak and giddy was she from excessive

sickness. Frank took her up in his arms, and carried her up

the steps as easily as if she had been a child. He set her

down safely on the pier, and gave her his arm, which she clasped

tightly as she looked up in his face, and told him that it was worth

being ill for.

"What is worth being ill for? I'm sure you saw little

enough," said her heavy-headed cousin.

"To—to—" she stammered, growing red instead of pale green.

"To have you so kind to me," she managed to say at last.

It dawned upon him then, and he made haste to repair, as far

as he could, any mischief he might have done.

"I'm glad you thought me kind, Ethel," he said, bluntly.

"I sometimes feared I might be quite the reverse."

"You?" she interrupted, with pretty surprise.

"Yes," he said. "I'll tell you a secret, Ethel.

I'm awfully in love, and the lady doesn't know it yet," he went on,

blundering.

"What is she like?" asked Ethel, archly, and trembling all

over.

"She is like—I can't tell you what she is like." He

grew suddenly inspired. "She is like a queen, or what one

thinks a queen ought to be, for stature and grace. She is like

the mother of little children. Her mouth is like a poem; her

eyes like a prayer."

Poor Ethel was bewildered, and no wonder.

"Is she dark or fair?" she asked.

"I think she is neither."

Ethel was blonde.

"Is she very strong?" asked the poor child, faintly.

"She could take you up and carry you as easily as I can."

Here was no hyperbole; and Ethel's spirit died within her,

while her woman's pride arose, and flung over her love its poor

little shroud.

"Do I know her?" she asked, quite trippingly.

Frank congratulated himself. Ethel's love was not very

deep. "No," he answered, "you do not know her."

"What is her name?" was Ethel's next question.

"Hyacinthe."

"What a strange, ugly name!" said Ethel, a little spitefully.

"Do you think so? I don't," replied her gallant cousin.

"It is a name that sounds and lingers like a perfume."

The maid had brought a fly, and they had reached the pier

gate, at which it waited. Ethel's huge box was already on the

top, and Miss Smith within. The hotel was not far distant;

Frank handed Ethel in, and said that he preferred to walk.

Ethel, as the cab moved on, fell fainting into the arms of

her aunt. The open window and the rattle of the stones soon

brought her to herself; but her first words were, "Oh, aunty, I wish

I had never come back!"

"You will be all right in a day or two," said Miss Smith,

soothingly; "the sea-sickness has prostrated you." But in her

secret heart she was rather uneasy about her niece.

For several days after their arrival Ethel was too ill to

make her appearance. Indeed, for the first time in her life,

Miss Smith began to believe in her extreme delicacy, and she now

begged Frank to remain with them till she had recovered sufficiently

to travel, in order that he might escort them home; and he, with his

accustomed good-nature, consented, though wishing himself once more

back at work.

An invitation reached them to come direct to Wanock, but

Ethel refused; she elected to go to the cottage instead. Her

disappointment—and she really suffered, though not too keenly—had

roused her and done her good. She bade Frank good-bye, with

thanks for his kindness. If she had always been as lively and

unexacting, he might have cared for her before he knew any better.

Ethel bade him good-bye pointedly, but he was not going very

far away, nor likely to be long absent. It was already

mid-October, and Gilbert had come home to spend his last fortnight,

though he would have declined to admit it, in recruiting his

exhausted strength. He had been spending the past six weeks

between a tour in the Highlands of Scotland and an excursion into

Cornwall, with a brother barrister interested in the Keltic race.

He had therefore had his full share of bodily exercise, to

compensate for the mental fatigue of the year.

The very day after Frank's arrival he proposed to ride over

to "The Retreat." He had expected to hear that his brother was

engaged to Ethel at last, otherwise why had he lingered so long?

His father and mother were urging Frank to marry, and did he not

detest the alternative they had provided? There was nothing,

under the circumstances, more likely than that he should close with

Ethel.

Gilbert was agreeably disappointed to find it otherwise, to

find Frank indifferent as ever to his cousin's charms of person and

fortune. The brothers rode over together, and a still greater

surprise awaited Gilbert.

Ethel received him with far more pleasure than she had ever

shown before. Her manner to him, especially when Frank was

beside, had generally been that absent one which suggests that the

absence of its object would not be undesirable. Now he seemed

to have changed places with Frank, and Frank with him. He had

never seen Ethel so animated, so pretty, so kind.

She addressed most of her talk to him. She took his arm

for a stroll down the garden, saying, "Frank and I have seen so much

of each other lately, that we are quite tired of each other's

society."

"How did you enjoy the Highlands?" she went on, when she had

got him to herself.

"Oh, very well," replied he, in a tone which seemed to say,

as much as he could enjoy anything.

"I have never been in the Highlands, you know, so you must

tell me all about them."

"I'll lend you a guide-book instead," he answered;

nevertheless he went on to describe, in exact if not glowing terms,

the winding lochs and heathy mountains and rocky glens he had

visited.

"How I should have liked to be with you!" she prattled.

"I feel almost strong enough to climb a mountain, at least a little

one. I wish I could go."

Cautious Gilbert, thrown completely off his guard, answered

that she might go with him there or anywhere else in the world if

she chose.

"How?" she asked, with such a look of innocence, fixing her

blue eyes on his face.

"As my wife," he answered her, shyly, for he had already

begun to realise his rashness in putting all to the touch at once.

"Do you care for me so much?" she rejoined, really touched,

and clinging to his arm.

"Do I care for you?" His look spoke the rest.

"I thought I liked Frank best," she said, in a tone of

deliberation; "but I will be your wife if you care to have me."

And she laid in his big brown hand her small transparent one, and

made her lover happy on the spot.

There was nothing very rapturous or elevating about it;

nevertheless both were satisfied. Perhaps neither of them

would have cared for the rapturous or elevating. Love is the

very flower of life; and as the man or the woman so will the love

be. The love of the self-seeking can never be very

noble—unless, indeed, it does that which all love contains the

blessed possibility of doing—lifts them out of self at once and for

ever.

Meanwhile Frank was having his own little private talk with

his aunt. "I have not heard you speak of your friend Miss

Field lately," he said, with all the coolness and unconcern he could

muster.

"No, I have not heard of her for an age," Miss Smith replied.

"I would have written, only that Ethel has been on my hands so

much." A look of smiling comprehension passed between aunt and

nephew. Miss Smith was known to consider having Ethel on her

hands enough excuse for anything.

It was some time since Frank had made himself acquainted with

all there was to know about Hyacinthe. "I wonder if she is

busy," he said. "Why?" said Miss Smith, looking at him.

"I couldn't help thinking what a jolly time we had here."

"Yes," sighed Miss Smith; "I wish she would come down again."

"It might do her good," said Frank, diplomatically but he was

not made for a diplomatist; he smiled a very conscious smile,

reddened up to the roots of his hair, and rushed into an

unpremeditated confidence.

"I shall ask her down again," were the words that had been on

Miss Smith's lips; but they took flight at Frank's confession, and

she was thankful to keep them to herself. "My dear Frank, Miss

Field is all that you say, but she hasn't a halfpenny, and she and

her sister have even to support their mother. I hope you will

do nothing without consulting your father. She knows nothing

of this, I hope?" she added.

"I have not spoken to her; and of course I will consult my

father," said Frank, who was chilled by his aunt's lack of sympathy.

Just then Gilbert and Ethel returned, and the understanding

between them was explained by the latter. "What a vain idiot I

must be!" thought Frank; "and yet I am sorry Gilbert has chosen such

a little nonentity." Then he spoke out: "I am glad you are

going to be happy, old fellow;" and shaking hands with both, he

proposed to ride home alone, a proposal which his brother thankfully

accepted.

That evening Gilbert communicated his good fortune to his

father and mother, and received their warmest congratulations.

It paved the way for Frank's confession, which was made to his

father as they walked on the terrace, smoking a cigar, before

bed-time. As they passed and repassed the drawing-room

windows, they could see Gilbert within, seated close to his mother's

chair in confidential talk.

"And who is the lady?" said Mr. Smith, sharply, when the

confession had been made.

"She is a Miss Field—a friend of aunty's," said Frank.

"I never heard of her," said his father.

"Perhaps not. She is poor."

"And how do you intend to live?"

"You are good enough to give me a certain income," said

Frank. "I propose to add to it by my own exertions, and am

only sorry that I have delayed so long the choice of a profession."

"Has the lady absolutely nothing?" said Mr. Smith.

"Nothing," replied Frank.

"How do you know? Who is she?"

"She is a teacher."

"A teacher! You propose to marry a teacher," said his

father, contemptuously.

"I assure you she is a lady, and highly cultivated and

refined. You would be proud of her as a daughter."

"Pooh, pooh, Frank. I tell you it is impossible.

I decline to take it into consideration." Mr. Smith threw away

the end of his cigar, opened the window with a jerk, and stepped

into the drawing-room, allowing no further parley.

What a tumult arose in the household at Warlock Place when

Frank, through his mother, announced his determination to persevere

in seeking the obnoxious alliance. What! share their wealth

and importance, their family advantages and their family honours,

with an outsider—one who had no family honours and advantages to

give in exchange! Even Miss Smith went over to the enemy, and

remonstrated on the futility of it. The time went by in

discussions fruitful only in disagreement. Mr. Smith's

ultimatum was, no income at all if he persisted. Frank went

back to keep his terms, and to work harder than ever; he was working

for freedom now, as well as for love.

But the worst of it was that he saw nothing of

Hyacinthe—could see nothing of her without Miss Smith's connivance,

and that she refused to give.

Christmas brought Gilbert's marriage, at which Frank was

groomsman. If he expected any sympathy from Gilbert under the

circumstances, he was mistaken. Ethel had taken up the

opposite side with bitterness. It introduced the thin edge of

the splitting wedge of alienation between the brothers.

CHAPTER IV.

GILBERT and Ethel

settled down at once into the life which was most congenial to both,

a life seemingly good and pleasant so far as it went, but centred

wholly in self; and in the end no life centred wholly in self can be

either pleasant or good. Even the life of fashion, with its

absurdities and sacrifices of ease and comfort, is in some respects

less dangerous than the life of domestic felicity which has no

higher end or aim. Christianity does not acknowledge such a

life at all, a life which shuts itself in and hedges itself round

amid carpets and curtains and couches, from all the toils and trials

and sorrows of the world without. Christianity is a service, a

ministry. To say you believe it, is nothing. Do you

accept the service, fulfil the ministry, is the Yes or the No.

Frank Smith dined once or twice at the pretty little house in

Kensington where his brother and his wife had taken up their abode.

To do Gilbert justice, he welcomed Frank, and would have liked to

see him just as comfortable and happy as he was himself; but for all

that Frank could see that he was not necessary to his happiness,

nay, that his absence was necessary to its present completeness, so

he began to make excuse.

He was too proud, and just then it would have been a little

inconsequent, to ask Miss Field's address; but he went oftener than

ever to his aunt's. One afternoon he found her sitting as

usual in her luxurious little room, in the cold spring weather, with

a table drawn up to the fire, and her gold spectacles gleaming on

her nose; but something else was glittering under them in her clear

grey eyes.

"My dear Frank!" was her greeting; and then she looked at

him, and gave a sniff, and took a letter in her hand, and tried to

speak, and failed.

"What's the matter, aunt?" exclaimed Frank, in alarm, for he

was unused to see her thus affected. She thrust the letter

into his hands, and he read:―

Bournemouth, Feb. 18.

MY DEAR

MISS SMITH,

"Your note followed me here. I am glad to feel that you have

not forgotten me, though we shall never meet on earth again. I

am dying. Do not be shocked. I am not suffering, at

least not much, and I go willingly to rest. I would not turn

back now, perhaps because it was so hard to reach this point, so

hard to give up life, and accept an early death. And I had to

struggle on alone. Now that it is near, my mother and sister

are with me. They will remain with me. There is such a

pretty churchyard here, with graves in the grass beneath the trees,

that look such quiet, natural resting-places! They will lay me

there. I wonder if you will ever see it. My work was

laid aside months ago, my chosen work at least; the Master had

something else for me. I thought I could prepare others for

life, and He called me to prepare myself for death. All is

easy when we meet His mandate with a simple 'Yes,' whether it be

living or dying. Hoping to meet you one day in His presence,

believe me affectionately yours,

"HYACINTHE

FIELD."

How long he took to read that letter, Frank Smith never knew;

it might have been moments, hours, ages. He did not speak, or

cry out. He made no sign. He only stood there erect, his

ruddy face paling a little, his strong pulses fluttering. He

stood up, and bore it in the strength of his manhood; but it felt as

if the waves had risen around him, risen to his heart, risen to his

very lips, and the next moment would be welling over him, and he

lying beneath them dead. He would not, could not speak of it.

After a time he took the letter and folded it, claiming it as his

own; and with a few common-places, mechanically spoken, he went

away.

That evening the letter was returned to Miss Smith, enclosed

in another, asking her to explain to the family the cause of his

absence. He had gone to her.

Miss Smith did as she was told, re-enclosing both the letters

to Frank's mother, and telling Gilbert what had taken his brother

away. The mother wept in secret, unable to withhold her

sympathy; the rest, whatever they thought, were silent. Family

criticism, in which they were strong, failed, and worldly feeling

was overawed. When Ethel remarked that Hyacinthe Field might

recover, no one answered her. They let the subject drop.

It was Hyacinthe's mother who received Frank, and received

him with reluctance, when she heard the claim he made, the claim

that he loved her child. "She has told me nothing of this,

though I have heard of you. I think she would have told me,"

she said, doubtfully.

"There was nothing that she could tell," he answered; "but

let her decide."

"You would not wish to disquiet her," pleaded the worn and

suffering woman. "It will be better for you not to see her."

"Let her decide," he answered still.

And Hyacinthe decided. The gleam of joy which lighted

up her face when she was told of his coming was enough. Mother

and sister stood aside, went forth and left them together, and

alone.

How beautiful she looked as she lay there! It was

difficult to believe that she was really dying, dying with that

flush upon her cheek, that brightness in her eyes, those happy

spirits, that vividness of every faculty. Frank's first

thought on seeing her was, "She shall not die." The very

tokens he accepted as tokens of life were the signals of death, the

fires that wasted her by day and consumed her by night. And

yet, as is often the case with those who die young, death was shorn

of its terrors even outwardly. There was very little that was

painful, nothing that was repulsive. Earthly care, too, had

ceased. It would have ceased with her in any case, in entire

dependence upon her heavenly Father, even if daily bread had failed;

but all that had been made sure. The family in whose service

she had contracted her fatal illness had insisted on providing for

her every comfort and every luxury.

That illness had arisen from the wilfulness of one of her

pupils, who had insisted on keeping a window open while she was

teaching. It was autumn, and Hyacinthe, fatigued and heated

with a Long and wearisome walk, chilled and shivered, and complained

of cold in vain. The chill brought on a cough, and the cough

made her feverish and weak.

The weather continued to get worse and worse. Hyacinthe

could not throw up her teaching in the beginning of the season to

nurse a cold, and it settled on her lungs. This was the short

sad story to which Frank Smith listened, with a conflict of feeling

difficult to describe.

His claim had been recognised. Henceforth he was to be

with her constantly, for the time was short, and sacred with the

double sacredness of love and death. Hyacinthe did not put his

love from her. This also her Lord had given her, making the

last of life sweetest and most precious. In giving it up she

was yielding no worthless thing, and yet she had reached the supreme

acquiescence. She would not unsay the words "Thy will be done"

to buy back life itself.

As for Frank, as he sat beside her, and learnt more and more

of her inner life, he seemed to look back on all his past as from

another sphere, a sphere which mirrored realities. It was not

that he judged differently, he seemed to see differently. Had

he seen with these eyes, other judgment would have been impossible,

impossible the walking in that vain show, a life of pleasure.

Anything would be better than that—labour, pain, sorrow—anything but

that utter selfishness.

He told her all there was to tell concerning his love for

her; how he had set himself to win her; how he had been working for

this alone, how little he should care to work again.

"Do not say that," she murmured; "you are called to work the

work of God."

"Then I have never heard the call."

"You have not heeded it. All men are called to work

God's work in the world. The Christian's calling is but a

higher one. 'My Father worketh hitherto, and I work,' said

Christ. 'I have finished the work that thou gayest me to do."'

"But He has given me none," said Frank. "That is what I

complain of in my life, it has been so aimless."

"Aimless, with the highest aim of all before you, to become a

fellow-worker with God!"

This tale must touch but lightly on what was said between

these two, united so strangely. Even between them, concerning

the things of the Spirit there was a religious reticence; much more

so must there be here. If we read it aright, all life is

sacred. There is nothing common or unclean: its love, whether

of lovers, or friends, or kindred, is sacred; so are its sorrows, so

are its most every-day trials and labours. But in the dealings

of God's Spirit with each and all of us there is something more

sacred, a Holy of Holies of which we can catch but a glimpse behind

the veil.

One morning, when Frank came as usual, Hyacinthe was gone.

He went in to see her with more calmness than he would have

manifested in her living presence, for she had suffered much of

late, and now she was at peace. She never looked so like one

of the flowers whose name she bore—so rich, so pure, so white, in

her perfect repose.

Very soon Frank was at home again in his family circle, but

no one spoke of his absence or its cause. His father was

inclined to remain offended, for he was a self-willed man and Frank

had not shown any sign of submission. But it would not do; he

was speedily disarmed. Instead of maintaining, as he had

expected, an attitude of injury, Frank exhibited a new and strange

deference to his wishes, and a new unselfishness and consideration

for all. Instead of throwing up his legal studies, and rushing

away to the ends of the earth, he went on with greater earnestness

in the path he had marked out for himself, the study of public law,

and if sometimes it seemed dry and profitless, he would say to

himself, "Never mind, it is work, and work which some one must do,

if this labour is not to be lost to the world." Unconsciously,

Frank Smith was putting to the test the promise, "If any man do my

will, he shall know of the doctrine whether it be of God." He

would begin by working, he might end in the peace and joy of

believing.

For some time he did not go into society, but beyond his

family circle no one knew why; it did not transpire, for she whom he

mourned had not belonged to this society of his. But at length

he began to make his appearance there, and his friends rejoiced over

him as one who has returned to the world. But before long he

was found out. He might be discovered where the music rose,

and even where the dancers whirled, but it was in a corner where he

had caught some one whom he knew, and was urging upon him or her

something that was to be done, something generally well worth doing.

He had invaded the party of pleasure for help for the workers, for

help and for fresh recruits. Some laughed and danced on, some

voted him a bore; but some listened and were won. Not a few

indeed, for to him belonged the rare charm of a perfect sympathy.

He had even learnt to sympathise with Miss Oliver, to see in her

extravagances a mistaken protest against the frivolity, the sloth,

and the littleness which eat out the lives of women, a half

inarticulate aspiration for a share in the work of the world, for a

higher standard of duty, a truer and nobler life.

A few years passed away, bringing more or less of change to

the several actors of our story. To Gilbert Smith they had

brought only unbounded success, success even greater than he had

ever anticipated. A lucky turn of political events, that is a

lucky turn for him, had brought him to the surface, and his talents

were such as are needed there—readiness, smoothness, and pliability,

an untiring industry, a faculty for getting things disposed of.

In those few years he had won all that he cared for of position and

public favour, and with these he was winning what he cared for still

more—money. Money was the watchword, the talisman, the

philosophers' stone of the day.

So Gilbert Smith earned largely, spent largely, and

accumulated largely. He had often, in his secret soul, envied

Frank's birthright. He envied him no more. One day he

would buy land, and hand down to his son a greater estate than his

father's. His father had always been hampered for money; he

hardly knew how to invest it in the meantime, so much of it flowed

into his hands.

He had been fortunate, too, in his marriage, so he thought at

least. Ethel was all that he desired; but then he did not

desire much. She did her duty in the matter of dress and

dinners, and she went into society as much as his position required,

and no more. That, however, was a great deal for her; it

demanded all her time and strength. In order to meet the

demand, she had to rest a great deal, that is, she had to lie on a

sofa all the early part of the day, and remain undisturbed with her

novel. She had children, too, but she saw little of them.

They were up-stairs in the nursery, a long way off, where never a

cry reached her ears. And the baby cried if he was left with

her, cried to go to his young nursemaid, always a sorry sight; and

the little girl crept shyly to her side in the drawing-room, and

behaved painfully well, being used to the stern control of the

sour-faced upper nurse, with whom she dared not soil a finger.

The breach between the brothers had widened, and was likely

to widen still more, for Frank had announced his intention of

marrying no other than Ellen Field, the sister of his lost

Hyacinthe. Frank had kept up the closest intimacy with the

Fields, and it had ended thus. Ellen's sweet and sincere

nature had won his regard, her friendlessness claimed his

protection, and his love had sprung from these, and from a tender

loyalty to the dead. When he made his brother aware of his

intention, Gilbert gave him up. He would not be at the pains

even to remonstrate.

It vexed his father too; but he said even less than Gilbert.

Mr. Smith was in the crisis of his own impending fate. He had

never been a rich man, but he had begun to be covetous of riches,

and having saved a little he risked it for more, and won. But

where there is much to be won, there must be much to be lost.

Where some are such gainers, others must be losers, that is to say

where none are workers, for wealth does not make itself. Mr.

Smith borrowed in order to make more, and lost all. The

bankruptcy court stared him in the face, and it was not a pleasant

prospect, for Mr. Smith was an honourable man in his way, and knew

that he had no business to be there.

At length he summoned his sons to a consultation on the state

of his affairs; it was easy to see that his hope was in Gilbert, and

not in Frank. But Gilbert would do nothing. It was

annoying, terribly annoying; but the disgrace was none of his.

People could not help their relations, and it would soon be

forgotten. Yes, the bankruptcy court would wipe out all

scores, there was nothing else for it.

Frank interposed. There was something else; the entail

could be cut off, and his father's debts paid in full. That

was the only honest, upright, just, and Christian course.

Frank was willing to cut off the entail.

If he had proposed to cut off his head, his father and

brother could not have been more astonished at the act of

self-sacrifice. "My brother is a born idiot," thought Gilbert

but it is no business of mine to stop him, especially as he is going

to make this foolish marriage. I will buy up the land and keep

it in the family." His proposal to do so reconciled his father

to a step which was very bitter to him; but the bankruptcy court

was, he confessed, bitterer still—it would have broken his heart, as

he afterwards owned.

Mr. and Mrs. Smith retired to a small house in London, on a

not too liberal allowance. Gilbert had had to pay fully more

than the estate was worth in order to redeem it from the hands of

his father's creditors, and he did not behave generously in the

matter of a settlement for his parents and his sister Florence.

He had borrowed a portion of the purchase-money, that was his plea

at the time; but he had borrowed it easily on the security of the

land, and might pay it in a year or two, if he chose, out of his

great and increasing income. But for Frank they would have

found themselves poor, and felt themselves neglected. Florence

indeed had to tear one of the bitterest sorrows that shake and not

seldom overthrow the spirit, the failure in the day of trial of a

love on which she counted surely. Up to the time of his

marriage, Frank remained with them, sharing cheerfully their altered

circumstances, bringing around them new friends, and awakening in

them fresh interests; above all, when they found their dead

formalism, their refuges of lies utterly unavailing, ready to lead

them to the truth and the life.

It was on the occasion of his marriage with Ellen Field that

Frank made his profession, for the first time in his manhood