|

[Previous Page]

THE CUMBERER OF THE GROUND

CHAPTER I.

MR.

ASHWORTH was Rector of

Pendock — Pendock in the Forest of Dean. To visit the rectory

for the first time was to feel at a loss where to find the said

Pendock, and to wonder if the entire parish consisted of the rectory

itself and the grey old hall visible from its windows. But the

parish consisted not of one village only, but of three, hidden and

stowed away in the forest glades — namely, Pendock, Pendock Dean,

and Helyar. Not a trace, however, of one of them was visible

from the rising ground on which the church and rectory stood, nor

from the other rising ground, with a dip between, on which stood

Helyar Hall. Nay, if you found out and reached the highest

ground in the neighbourhood, or the highest in the old forest, the

famous Rocking Stone — which a child may sway with a touch of its

finger, and a giant could not move from its place — you would see

nothing but trees: trees over hill and dale and height and hollow;

trees hiding glade and river and village alike, and seeming to

stretch in an unbroken density as far as the eye can see.

But down among them it is not so. Lovely glades open up

on every side, where brooklets run noiselessly among velvet mosses,

where great oaks stand singly or in groups of twos and threes, and

the ferns glance in the sunshine with broad plumy leaves. And

the cottages nestle by the brook-side, and little children run out

into the glade and scamper back again like rabbits. And the

river is at hand, for you can hear it murmuring in answer to the

murmur of the wood; and you wonder why it should be here and yet

there, till you come to know its turnings and windings. For

the river is the "winding Wye," and it curves, and doubles, and

loops itself up, as if it wanted to linger on its way for ever.

Wood and river between them seem muttering a Druid spell.

Walking in the wood is like "walking in a story" — that describes it

best. You start as if someone called your name, and it is the

coo of the wood-dove; you have heard there is a beckoning, and you

wonder if it is only the waving of the fern, you stand still to

watch a bee plunge into a foxglove bell and swing there; hear a

whirr and a flutter, feel a touch, and turn about to meet a pair of

bright eyes almost on a level with your own.

Then the silence is broken by the sound of the woodman's axe,

and the spell is broken with it, and you think of the time of good

Queen Bess, when the forest furnished oak for the ships that chased

the Armada. Or another and ruder sound summons you into the

presence of to-day. It is the kind of chant with which the

miners cheer the way as they tramp home from the mine. Wild,

gaunt, dismal figures they are, in shirts and trousers loosely bound

round the waist, the shirt thrown back, and showing their bare,

shaggy breasts, and on their heads nothing whatever save masses of

matted hair. They are the parishioners of the Rev. Henry

Ashworth.

The Rev. Mr. Ashworth was a gentleman and a scholar — he was

more, he was a thoroughly kind-hearted, noble-minded man. He

had spent the best part of his life in the forest, and against its

drowsy spell he had signed himself with the sign of the cross, and

had called on himself to endure hardness as a good soldier of Christ

Jesus. So he trod the forest ways with great broad-soled

boots, often ankle-deep in mire, to preach in the little mouldering

church that was nearest to the poorest of his flock, and oftener

still to minister to the sick and the dying, carrying comfort for

the body as well as for the soul in his great flapping pockets.

Mr. Ashworth had married a lady of rank and birth, belonging

to a poverty-stricken branch of an aristocratic family. To

settle down in the forest for life was by no means what she had

looked forward to in marrying Mr. Ashworth. Perhaps she had

visions of lawn sleeves and a bench in the House of Lords. At

any rate, she had anticipations of preferment, and hoped to see her

husband attain at the very least a deanery in one of the three not

far distant cathedral towns. She would have enjoyed the

position of wife to the Dean of Worcester, Gloucester, or Hereford,

more than any other position on earth. Its quiet dignity and

ease would have suited her exactly. She liked society in a

mild form, good and well-born society, but not too much of it.

She was too refined, too luxurious, too lazy, to care for the fierce

competition of fashion and of social success in metropolitan

circles.

But she had married a man of no ambition, at least of no

worldly ambition, a man who was content to trudge through the forest

ways on duty, and to trudge through them on pleasure too, pleased

with the simple successes and triumphs of a naturalist; a man with a

strange unaccountable love of humanity in its meanest forms, just as

he prized his tin box full of unsightly weeds above the rarest

exotics; a man who often did the duty of a country doctor in

addition to his own, and who delighted to plant fruit trees in the

cottage gardens, and to graft them with his own hands.

Providence had surely dealt in irony towards Miss Lechmeer in

letting her see only the wonderful personal beauty and dignity of

her future husband; for she had said, deliberately, "If I had had

any idea of his tastes and pursuits I would not have married him."

And as Mr. Ashworth was not given to seeking preferment he did not

find it. To get good things one requires to be on the lookout

for them; and to be on the lookout for the good things of this world

did not suit the quality of Mr. Ashworth's mind. He was a man

who took root, too, wherever he was planted, and he had ever an

objection to be rooted up.

So Mrs. Ashworth was condemned to live such a life at Pendock

as was possible for her. When she could make her escape from

it for a time, she was only too happy to join her aristocratic

relatives in Cheltenham or Bath, and such times became to her more

and more of a necessity. No matter that she left her husband

at home, or only carried him with her as an escort, to conduct her

to the scenes she loved and leave her to their enjoyment, no matter

that she left her children behind her to the care of a hireling;

change and society were necessary to her, and that was enough.

Besides, her husband's children got on very well without her, which

was true, fortunately for them.

Mrs. Ashworth disliked children, and she had actually been

burdened with two. To hear her speak of the trouble they were

to her you would have supposed that she nursed them, fed them, and

kept them from morning till night, and slept with them from night

till morning, as low-born mothers must. But no such thing.

She kissed them every morning when they were brought to her fresh

from their baths by their old Welsh nurse, and every evening when

they were carried off to bed by the same; and that was about all she

ever did for them when they were mere babies.

The eldest — eldest by about three years — named Adelaide,

was a child after her mother's own heart; the second, named Mary,

was after her father's. Perhaps it was because of the three

years' interval between their ages that the training of the two was

as different as their dispositions. Adelaide went to school

from a very early age, the age of ten; while the nursery governess

who had instructed her and her little sister up to that time, stayed

on with Mary till she was fifteen. Adelaide's school was in

Cheltenham, and she was much with her mother's aristocratic old

aunts, and as she grew up, much with her mother visiting.

Mary, the father's child, stayed at home or trotted by his side on a

little shaggy pony, carried a basket for him every now and then, and

wore cotton gloves, and worked in the garden.

But then Molly, as her father called her, was a very plain

little girl, dusky-browed, rather fat-faced, and decidedly dumpy of

figure. Her nose and her lips, too, were somewhat thick, and

she had only the largest and softest of dark doe's eyes and clouds

of jet-black hair to recommend her.

To her mother they did not recommend her in the least.

She used openly to wonder where the child could have dropped from,

to marvel at her being child of hers at all. Certainly Molly

was more energetic than elegant; her elf locks were not always tidy,

her plump cheeks were apt to glow like homely cabbage roses, and her

big feet to catch in her mamma's long dresses, bringing down upon

her a tirade on awkwardness.

Adelaide grew up into a very beautiful girl, rarely pale, and

superbly elegant. Her dark hair was smoothly parted over the

perfect forehead, and coiled round the small graceful head.

She was taller than most girls, and her figure had an undulating

softness. Her eyes were of darkish grey, but they drooped

under the whitest of lids, and had a half-open, dreaming look.

All her features were small and delicate, and her hands wonderfully

so. No one could venture to suppose that such hands were ever

intended to work at anything but an embroidery needle. Nor did

they.

Let no one run away with the idea that Adelaide Ashworth was

a hateful or contemptible human being. She was neither; not

then in the blessed time of youth, nor ever, was she such. She

was beautiful and graceful, modest, and sweet, and good. In

her youth-time she was like one of God's own lilies, that "toil not,

neither do they spin," and yet have their place and their praise in

merely shining where they stand. If she could have died then

there were those who loved her who thought it might have been better

than living as she lived. For at the time when this story

really commences her youth was over and gone. The blossom of

it had fallen, and fallen fruitless, to the ground; and there was

left of it only dust and ashes, the dust and ashes of disappointment

and vain regret.

At this time Mr. Ashworth had been ten years a widower, and

his daughters had reached the sober-sounding ages of thirty-five and

thirty-two. Sober-sounding; for I doubt if Molly was more

sober now than as a little maid of ten. Indeed, I think she

grew less and less sober as the years went on; for her mother had

been a constantly restraining influence, and her death had been a

relief both to her father and her. Not that they thought so,

it was utterly unconscious, but still they breathed more freely,

came in with muddier feet, kept more obnoxious pets, and made a

greater litter than ever, and, above all, had more people coming

about the place on more unwarrantable pretexts of sickness,

poverty,&c.

As for Adelaide, she did not interfere with them at all.

Though the elder sister, she left the housekeeping entirely to

Molly, whose mission it was, and who waited on her hand and foot

besides. For instance, it pleased Molly to stand behind her

sister's chair, and brush out her long silky tresses, Adelaide

liking the sensation extremely, while she knotted up her own thick

locks unassisted. It pleased her, too, to kneel, in the

privacy of their bedchamber, and wash Adelaide's dainty feet, while

she utterly refused a return of the humble service.

Ever since her disappointment — that was the way in which

Molly and her father spoke of a certain event in Adelaide's life —

she had taken very little interest in herself or her surroundings,

except what of personal care was necessary to preserve her beauty

and to keep her always fresh and dainty as a lady should be.

That disappointment had taken place ten years ago, just before her

mother died. She was then a very beautiful young woman, but

she had not had many lovers. She lacked the element of

interest, and appeared only coldly elegant. Molly, if she had

had the opportunities of her sister, would have been ten times as

much sought after. She was interesting then and always; but

there was nobody for Molly to interest except the old ladies at

Helyar Hall, and Molly had interested them. However, just at

the age of twenty-five, Adelaide made the acquaintance of the second

son of Lord Fenmore. He was some four years her junior, and

fresh from Cambridge, in sickly health, and with an over-sensitive

temperament. Adelaide suited him exactly. She was far

from mindless, and yet she had no objectionable activity either of

mind or body, she was so perfect in repose, could do nothing and say

nothing with such graceful composure. The young man fell in

love with her, and engaged himself to her without consulting the

superior powers; and the superior powers avenged themselves.

They put no veto upon the engagement, they even admired the choice

which their son and brother, had made; but they steadily refused to

furnish an income. And so the affair dropped.

Adelaide suffered a serious collapse when it was finally

broken off, and they ceased even to correspond. Their

communication by letter had been by far the most vivid part of their

courtship. His poetry read very well in prose, and her prose

was lighted up by a light and delicate humour. Adelaide

suffered in dignity and in affection. The idea of blighted

affections has been used for ignoble purposes, and may provoke only

a smile; but Adelaide's gentle affections were blighted — no other

word describes the process so well. And there is no process

more melancholy. Adelaide came down to Pendock, where her

mother was already laid up with wasting sickness, only to add to the

general depression. She had always been a great deal away from

home, and her mother feared the dullness of the place for her

favourite daughter; but she could not drive her from her death-bed,

and Adelaide had no wish to go.

After her mother's death her father's house became Adelaide's

permanent home, and both father and sister had begun a series of

indulgences with a view to render it endurable to her. She had

none of their active pursuits and enjoyments; books and fine

embroideries for her own wear were her only occupations, these and a

little music.

Except for the pony carriage, Adelaide would have known

nothing of the forest and its wondrous charm. She utterly

refused to tread its tangled and devious paths, and there were only

certain broad tracks which the carriage could take. Of course

there were days and weeks when it rained in the forest, when under

the trees was a universal and perpetual shower-bath, and there were

weeks and months when winter reigned there supreme — frosts, when

the banks, with their delicate leaf traceries, of which they were

never bare, showed fairer than the fairest embroidery in the world;

snows, when the trees were crusted with white, and shone like

alabaster, and made cathedral arches of black and silver in endless

vistas, which glimmered into distance like a glimpse of the temple

not made with hands. Then there was nothing for Adelaide but

her needle and her books.

Her reading, like herself, was curiously limited. It

consisted almost entirely of fiction and devotion — the "Golden

Treasury" alternating with Bulwer Lytton's last novel. Though

she did not know it, the spell of the forest was upon Adelaide,

turning her religion and all her life into a dream.

Their nearest and indeed only neighbours were the Helyars of

Helyar Hall, and there had always existed the greatest friendship

between the hall and the rectory; only it was long since the

friendship of the hall had been of any social value; long since the

huntsman had issued from its gates to join the meet in the

mid-forest; long since the dancers had danced upon its oaken floors

till daylight looked in upon their pastime; long since the Helyars

of past generations, from their frames on the great dining-room

wall, had looked down upon the huge venison pasty, large and round

as a shield, which used to grace the feasts of bygone days.

Mrs. Helyar had come to Helyar Hall a bride, and had lived

there a happy wife, enjoying the neighbourhood, enjoying her visits

to London, enjoying everything that came in her way. Her

children were born there — two daughters, and at last, amid great

rejoicing, a son and heir. There she had spent several years

of widowhood, and had left it, as the last Mrs. Helyar had left it

for her, when her son brought home his wife.

Then another heir had been born, and the succession to the

old hall seemed secure for at least two generations; but old Mrs.

Helyar had lived to see them pass away. One after the other,

in youth, and manhood, and middle age, her son, and her son's wife,

and her son's son, all were gone; and she and her daughters had come

back to the old place again.

Her daughters — the young ladies as they were called, but not

in mockery — had each numbered her threescore years and ten; the old

lady was drawing nigh to a hundred, and for the last ten they had

been years of torpor and suffering, sometimes the one prevailed,

sometimes the other. It was truly a life in death, a

long-prolonged dying.

It was the height of summer. The rectory ponies trotted

along the sward of a broad path through the forest, and the rectory

carriage bumped after them in the peculiar manner in which carriages

bump over uneven turf. The path looked like a glorious avenue,

with magnificent vistas opening out on every side, and wonderful

effects of light and shade; but Adelaide expressed her thankfulness

when they came out at length upon a road. The sisters were

going into town to do a little shopping, &c.; for Adelaide was going

to pay a visit to her mother's relations at Weston-super-Mare for

the season.

They entered together the quiet sleepy shop of the country

town; and Molly set herself to aid her sister in selecting some

pretty muslins to be made up in readiness for her seaside visit.

It took some time, for Adelaide was fastidious in her tastes; but at

length she had selected three of the finest and prettiest.

"And won't you have one of each as well?" she asked of Molly,

who had also come to buy. "No, dear," says Molly. "I would

like to look at some prints. I should tear such muslins to pieces

the first time I took a walk in the forest."

Besides, she thought in her heart they would not be of the

slightest use when she had done with them, and she was in the habit

of buying dresses which made down after the season or two into

frocks for the village children. "Take one of these for

evening wear, to please me," said Adelaide; "and let me make you a

present of it."

And Molly accepts, with pleasant thanks, and gets her prints

besides, and after visiting the dressmaker, a few doors off from

the draper, they re-enter the pony carriage, and drive once more

along the level highway, and turn again into the broad forest path,

and so home.

"I am going to stop at the hall, Adelaide," says Molly. "Poor Mrs. Helyar has been rather worse this day or two, and I shall go up and

see her. One never knows but it may be for the last time."

"I don't think any set of people ever had such dull neighbours,"

returns Adelaide. "What a blessing it would be if poor Mrs. Helyar

was to die!"

"Yes, a great blessing," says Molly, but somehow in a different

tone.

So she stops at the hall gates, and runs up the steps and across the

lawn, and in at the open door, and goes straight up-stairs with all

her open air freshness about her. The old lady sits in her chair half

asleep, her maid working beside her. Many an hour's relaxation poor

Harriet owes to Molly, who will come and sit with the old lady for

an hour or two at a time, and let her out to walk in the grounds.

"How are you to-day, Mrs. Helyar?" says Molly's bright clear voice.

And the old lady, with a half start, recognises her, and stretches

out a trembling, withered old hand, which Molly continues to hold in

hers as she kneels down beside her.

"I am still here, my dear," says the old lady, rousing up yet more. The fresh voice is pleasant to the drowsy ear, and the fresh face is

clearer to the dim eyes. "I am still here," she repeats, "a cumberer

of the ground."

"No, not that," says Molly. "We do not call the tree when the fruit

is gathered a cumberer of the ground."

She enunciates every word distinctly, and the idea reaches the

listener's mind, and she nods her head in approval.

"We know it has to wait for the spring," says Molly, speaking again,

with the enforced distinctness which gives her voice a tone of

strong assurance.

Tears come into the attendant's eyes as she repeats the words. Everything has to be said twice over to the old lady, who nods in

response, "Ay, ay." Then she wanders off into something about

"Willie." Willie was her grandson.

Then the attendant explains that her mind is wandering a little, for

she has lately been afflicted with utter sleeplessness.

After a pause, however, she turns round with startling abruptness to

Molly, still holding her hand, and asks, "Who are you?"

"I am Molly, dear Mrs. Helyar; Molly Ashworth."

"Ay, ay, little Molly. They were very fond of each other, these two,

Molly and Willie," she says.

Molly caresses a little longer the withered hand, then rises and

kisses Mrs. Helyar on the cheek, and steals away. But her visit is

not over. She has still to see the other ladies of the family, to

whom she is, to use a homely phrase, "welcome as flowers in May."

"We have had a delicious drive," she says, tripping in upon them. "Adelaide and I went into town today, and bought some pretty summer

dresses, and it was so bright and yet so fresh in the forest, I

thought we might meet you as we came along."

The Misses Helyar still crept out in the sunshine, while the old

lady sometimes insisted on driving out in all weathers.

"We have not cared to go out to-day," said the eldest. "Such a

strange thing happened last night. We have both had nervous

headaches all day. Has Harriet told you?"

"No," says Molly, a little mystified.

"Mamma insisted on getting into the carriage at twelve o'clock last

night, and driving about for hours," said Miss Helyar. "You know it

was a moonlight night, and she took it for day, and made Harriet

dress her; and then Harriet was obliged to call me, and I had to

wake Thomas and tell him to get out the carriage, for she sat crying

and wringing her hands, and asking to be driven 'home.'"

"Dear me, how mournful!" says Molly, her great eyes dilating with

sympathy. "And did you go with her?"

"Yes," replied Miss Helyar. "We both went, and we told Thomas to

keep as near the house as he could; but I assure you it was hours

before she would come in, and we were drenched with the dew."

"It was dreadful," said the youngest Miss Helyar, shuddering. "The

bats flew into our laps and into our very faces, and I thought the

owls would have followed them."

"I wonder some of your people did not hear us, for we were round by

the rectory, and past the churchyard wall," said the eldest.

"No one can have heard you, I think; but I wish you had knocked me

up, I might have had the power to soothe her," says Molly.

Molly had tried this power of hers before now. She had it in a

remarkable degree. And just now she was exercising it, by her mere

presence, on these two poor women. Half their trouble seemed to have

evaporated in telling it to her, and meeting her kindly sympathy. Then they returned to the subject of the summer dresses, and the

Misses Helyar said they had been thinking of getting some lighter

things. Would Molly go with them to choose?

Molly cheerfully assented, and the very next day was fixed by Miss

Helyar; so that she would have to make a precisely similar

excursion to the one which she had just made, bumping along the same turfy forest road into the same sleepy little town and shop, only

with the Misses Helyar instead of her darling Adelaide for company.

Molly, having promised to come, took her way home, thinking not of

the dullness of these lives, but of the strange and awful necessities

which guided them; thinking of that eerie drive in the moonlight,

which filial duty and tenderness had compelled, the gibbering old

woman, with wits all astray, by their side, and the owls and bats

for attendants.

CHAPTER II.

THE week that

followed was a very busy one for Molly, for she had to look over her

sister's entire wardrobe, and see that all her pretty things were

properly got up, and altered, and added too, as was requisite for

her visit. It never struck Molly that her sister ought to have done

all this for herself as she went about it, sometimes hot and tired

with the work, while Adelaide sat under the walnut tree on the lawn,

in an easy chair set upon a mat, dreaming with drooping eyelids over

"The Christian Year."

"But at length all was accomplished, even to the last and most

tiresome work of packing, Adelaide putting in with her own hands on

the top of a monster trunk, her Prayer-book and "Golden Treasury,"

her "Christian Year" and Hymn-book; as wherever she might be she

spent an hour or two daily over these. The trunk and its lesser

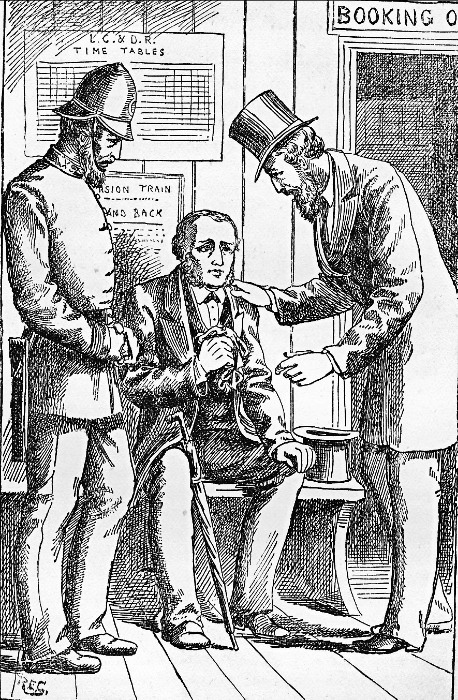

satellites were sent to the station in the cart, and Adelaide and

Molly followed in the pony carriage in due time.

When the train arrived Molly ran along and discovered an empty

first-class carriage, and then ran back and saw her sister into it,

standing nodding and kissing her hand in self-congratulatory mood as

the train puffed out of the station; for Adelaide disliked numbers,

and close carriages, and travelling companions, and Molly had

succeeded in getting her a carriage all to herself and had sent her

off in the greatest possible comfort.

There we leave Molly for the present, and follow Adelaide. Very nice

and fresh she looks, or rather her attire looks, as she leans back

on the dark cushions of the carriage. She has on one of her new

chintz muslins, elegantly made — at least it looks so upon her — with a

loose scarf of the same, and a tiny lace bonnet on her head. When

you look more closely you find that, in spite of faultless teeth and

perfect hair, she seems older than she ought to be. She never had

any colour, but the nameless, clearness of youth is clean gone,

there are wrinkles, actual wrinkles, round the mouth and eyes, a

general deadness of appearance on cheek and brow. But she is alive

to the least discomfort. The dust is blowing in clouds along the

line, and she rises and shuts the windows all but an inch at the

top. She has hardly settled herself once more when the train stops. The guard comes and opens the door with a bag in his hand, deposits

it under the seat, and makes way for its owner. She sees a gentleman

stepping into the carriage, but for the moment is occupied with the

care of her skirts puffing out in the direction of the door.

The gentleman sits down opposite, and exclaims, "Adelaide!"

She raises her eyes and encounters those of Geoffrey Fenmore, once

her accepted lover. The faintest blush, but it is a very lovely one,

rises on her face, and she holds out her hand to him with her old

grace of greeting.

"It is an age since we met," he says, awkwardly, evidently feeling

the position. But she cannot be awkward, and she does not indulge in

feeling. She tries to put him at his ease, and succeeds, asking

after mutual friends and acquaintances. She has much to learn, and

for one thing that

he is no longer plain Mr. Geoffrey, but Lord Fenmore, the two lives

between him and the peerage having been cut off.

He feels a little piqued at her perfect calm, begins, as he sits

opposite to her, to wonder if it is real or assumed, then to

speculate if it would be possible for him to shake it. Silence has

stolen over both of them, and in the silence Adelaide's eyelids

droop, and her companion watches her face. Its old charm steals over

him — the sweetness of its repose. He becomes quite poetical

concerning the time when it was the one face he loved to look at. He

thinks there are not many — nay, he is sure not one — he would like

to look at for a lifetime so well even yet. He realises all that he suffered at the time their engagement was broken off, and what must

she have suffered? He has never seen her since. What has she been

doing with herself all those years? he ventures to ask; has she been

abroad?

"No," replies Adelaide, "I have been living at home."

"Forgive me, but I forget where that is. You were living with your

relatives in Cheltenham when — when we first met."

Here was another awkward allusion — and he had stumbled over it too.

"Yes, but since we met last," she answered, calmly, "I have been

with my father at Pendock, a little place in the forest, with hardly

any interval."

"I hope you have pleasant neighbours," he says next, by way of

saying something.

"There is only one family near the place at all," she answers. "It

consists of three ladies, and their united ages make more than a

couple of centuries — not far from two and a half indeed. You could

not fancy anything so dull."

"And why do you go on living at such a dismal place?" he says.

"I have no choice," she answers, but with a smile.

"What a wrong I have done this sweet woman!" he thinks. "She went

out of society because of the breaking off of our engagement, and

has never returned to it again all those years; but it is a wrong

which can be repaired, thank Heaven!" And then, in the silence

following, he thinks what unity it would give his life to make the

lady who was his first love the wife for whom he is even now on the

lookout.

So when the train stops, or rather shows signs of stopping, at the

next station, he says, in an agitated voice, "May I ask where you

will be staying for the next few days?"

She gives him her address, already written on her card, and the

train stops.

"Adelaide, you will let me write to you?" he whispers, pressing her

hand.

He is gone. The train is again in motion. Adelaide is leaning on the

arm of her seat, trembling and in tears. "Oh, I have not deserved

such happiness," she says to herself

over and over again during the journey, as she looks back on the

long, aimless, effortless, useless years in which her one feeling

had been disappointment — her one desire to forget almost that she

lived. Ten years of a life, and what to show for it? She could count

the collars she had embroidered; she could almost number the books

she had read, for she read but slowly. Oh, if this happiness, once

more promised — her heart told her it was once more promised — should

indeed befall her, she would be so different! Happiness was so good

for people. It was like the sun to the tree. Fruit could not ripen

without sunshine. In the sunshine of happiness she would bring forth

much fruit.

Thinking such thoughts as these, Adelaide reached her journey's end

at last, almost forgetful for once of the discomforts of heat, and

dust, and travel. She did not write home that evening. She would

wait for another day before she told her sister of the meeting with

Lord Fenmore. Another day might bring her a letter from him.

And it did. He lost no time in taking advantage of the permission to

write, and he wrote with more of fervour than he had ever shown,

asking that the past should be bridged over, and that their old

engagement should be renewed. "It need be renewed only for the

shortest possible time," he wrote , "for there is no reason on my

side — and I hope there is none on yours — against an almost immediate

union."

She had no reason to allege, though she put in a little plea against

herself on the score of age — a plea which he of course refuted; and

in a day or two he was by her side, once more her acknowledged and

accepted, and perfectly satisfied, lover.

And in the meantime she had astonished — nay, electrified — Molly by the

news of her meeting with Lord Fenmore and the renewal of their old

relations; and Molly had tried to electrify her father, and had very

indifferently succeeded, and she had then rushed off to expend her

unexhausted battery on the Misses Helyar, who very coolly intimated

that they were sorry it was not herself that was going to marry Lord

Fenmore, and then declared warmly that they were very glad.

Day after day brought fresh intelligence from Adelaide. One letter

stated that her visit must be shortened, for Lord Fenmore was asking

her to fix a ridiculously early day; the next announced that the day

was fixed, only there was one between from Lord Fenmore to Mr.

Ashworth, containing the terms of a handsome settlement.

The day was fixed, and Adelaide came home to make her preparations

for finally leaving it. She responded with the most perfect

sweetness to Molly's demonstration; but if she had before been

self-absorbed in her disappointment, she was now ten times more

self-absorbed in her new-found happiness and triumph. Molly,

unselfish as she was, felt just a little blank and chill at the way

in which Adelaide threw herself into the future, as if the present

had in it nothing worthy of love and the past nothing worthy of regret. She could not help feeling how differently she herself would have

prepared to leave father and sister and home — how little of exultation

there would have been in her spirit as the time drew near.

Lord Fenmore was coming to visit them for a few days before he came

to carry off his bride, and great were the preparations made for his

coming. Pendock had been so long unused to guests. It was the

morning of the day on which he was expected. The sisters were to

drive to the little station to meet him, and everything seemed very

happily in train for his reception, when Molly was summoned suddenly

from her sister's dressing room.

Down in the hall she found a frantic woman, shawlless and bonnetless,

panting for breath, incoherent with sobbing, dirty and dishevelled,

who seized hold of her with both hands, and managed to get out the

words, "My little Jim is scalded! Come, for God's sake, Miss! I can

hear him screeching all this way," and she placed her open palms

against her ears, and gave a cry that brought everybody in the house

to the spot.

"Tell me what you did to him before you came here," asked Molly,

getting white about the lips; but keeping very calm, and forcing the

poor woman to be calm too.

"You said flour was good when Wat Stokes was scalded, Miss, and I

put on all I had in the house. Jim's poured the boilin' water right

down his bosom. Oh, come, Miss; come!"

"I'm coming. Jane, get my hat, and wait on Miss Ashworth. I want

some things."

She took her keys, and went into the store-closet and fetched a

bottle of salad oil. Then she got some lint, some oil-silk, and some

sticking-plaister from her fatlier's medicine-chest, a pair of

scissors, and a sponge. She forgot nothing. Last of all she filled a

breakfast-cup with jelly, and in as short a time as it takes to

tell, she was hastening through the forest at the woman's side;

flying would describe it better, for the woman kept quickening her

pace till it became a run.

They found the poor little fellow exhausted with weeping, and all

the women and children of the village buzzing about like bees. Molly's first task was to send them home to their own domestic

concerns, and to feed the child with a portion of the jelly and

light cake she had brought with her.

Thanks to the scantiness of the boy's clothing, and the way in which

his mother had filled his poor little bosom with the flour, the skin

was not much off and the dressing was an easier matter than Molly

had apprehended. Still, she had to dress the bad places with the

lint and oil, and stick on the oil-silk over them with little strips

of the plaister, and give a great many directions as to the care of

the blisters and the child's food, before she got away with a

promise to come again tomorrow.

Then Molly had to hurry back through the heat, a mile and a half at

least; and stopping to look at her watch, she arrived at the

pleasant consciousness that she would be too late for the drive to

the station, late for dressing, late for everything. And she hurried

on faster than ever, arriving just in time to see the pony carriage

come round to the door.

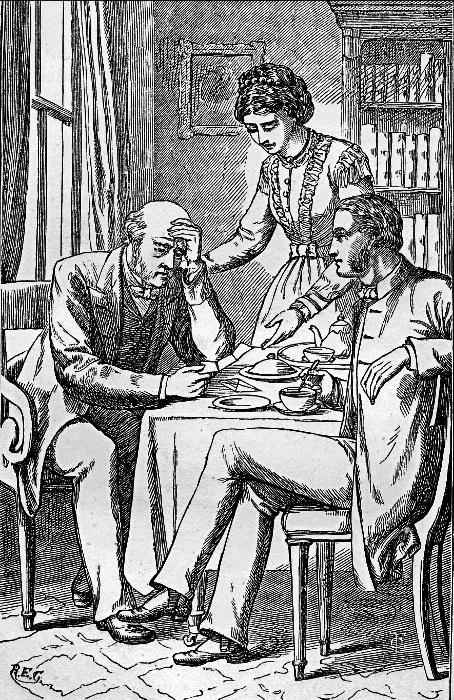

Hastening into the dining-room, where she caught a glimpse of her

father and Adelaide, she flung herself on a chair and threw down her

hat at her feet, sitting a few minutes before she could find

composure to speak. Truth to say, Molly did not at that moment

present a genteel figure. Her hair was untidy. She was very hot, and

had had no lunch, which caused her to look a little fagged with her

exertions. Her print dress was soiled with contact with the cottage

floor; in short, she was not presentable.

Adelaide was standing ready dressed, cool and fresh in her lace and

muslin, and a little, just a little, shade of annoyance on her face.

"Oh, Molly! what a fright you are!" was her greeting.

"Well, Molly, my dear!" was her father's.

"I fear I'm too late to go to the station," said Molly, and she felt

ready to cry with disappointment; "but I could not help it. Poor

little Timothy Wells has been pouring a kettle of boiling water over

his chest, and I have had such trouble with him, and it has been

such hot work,"

"You certainly do look hot," says Adelaide.

"You should lie down here for half an hour before you dress. This is

the coolest room in the house."

"Don't you think if I made haste and threw on my dress I might still

go. We could drive a little faster, you know," pleaded Molly.

"You would be hotter than ever, Molly, and more flustered; and there

is nothing I hate like people in a fluster. Papa is ready, and has

offered to go," said Adelaide.

It must be recorded Molly was not herself that day. She burst into

tears. Adelaide hastened to soothe her, saying she had overdone

herself. Mr. Ashworth walked to the

window, and pretended not to see. Then Molly left the room, and he

told his eldest daughter rather coldly that he was waiting; and they

got into the pony carriage and drove away.

"I wish Molly would not be such a child," said Adelaide.

"And I that she may never be less like one," said her father.

"But I don't see why she should have to care for all these people,"

said Adelaide.

"They have few to care for them besides," said Mr. Ashworth,

shortly.

"They seem quite to expect it," said Adelaide.

"Yes; I am happy to say they do," replied her father.

"Oh! but I mean they are not in the least grateful. They expect it

as a matter of course," she rejoined.

"And I repeat that I am glad they do," replied her father, somewhat

sternly. "When they cease to expect loving kindness from us in the

midst of their sufferings and deprivations, they will cease to

expect it or to seek it from Him whose name we bear, and whose work

we are sent to do."

Adelaide was silenced. She had mind enough to feel the full force of

her father's words, and they sobered as well as silenced her. I fear

Lord Fenmore found his reception far from overwhelming in its

warmth.

The warmest of it was from Molly, who had bathed her face, and cried

and bathed it again. She did not often cry, and so perhaps, having

once begun, found it difficult to stop; and by the time the party

returned she was so humbled by her trouble that she was prepared to

lavish herself on the least worthy individual she came across. She

was so kind and so genial, so self-possessed by dint of having put

herself entirely out of the question, that her lordly brother-in-law

elect, whom she had succeeded in making thoroughly at home,

expressed the most flattering opinion of her, to Adelaide's immense

relief

Lord Fenmore was, indeed, very much pleased with his bride's

surroundings. They were plain — Pendock Rectory was a small and not

very well-appointed house — but they were perfectly unpretentious. Mr. Ashworth was a thorough gentleman, and Molly was charming. Next

day there was a dinner at the hall, and the Misses Helyar had

actually caught a commissioner to meet His Lordship, and the venison

pasty duly appeared.

The days were spent in exploring the forest; and, as Lord Fenmore

had a true though thin vein of poetry in his character, he found

them pleasant days enough. Molly was more with her sister's lover

during the visit than Adelaide was herself. It was she who took him

to the Rocking Stone, a good long walk, and a rough clamber at the

end of it. It was she who took him on the river, down past Tintern

and Monmouth; and up to the Wyndcliff another half day, when they

came back calling each other Molly and Geoffrey. It was she who

risked her life with him in a coracle, a boat in use among the

ancient Britons, and consisting only of a basket-work frame, with a

piece of

tarpaulin stretched over it. And, indeed, they very narrowly escaped

ducking, or drowning, for Lord Femnore, getting rather energetically

into the airy bark, so nearly capsized it, that thrusting down his

umbrella to steady it, he fairly scuttled it.

Luckily he had sufficient presence of mind to keep the umbrella fast

in the hole it had made, and so allowed Molly to get out again in

safety, and followed himself in high glee over the adventure.

But Molly could see the difference when he was with Adelaide — how

tender and devoted Geoffrey was then. She would stand at a window

and watch them take their after dinner walk, never to any great

distance, only across the lawn, perhaps, and through the field

beyond, where Molly could see the two figures loitering along by the

hedgerow, under the primrose sky, could see Geoffrey catch

Adelaide's hand and hold it as they walked. Then she would turn

round into the room, and sigh with a certain sense of desolateness —

a sense of having been left out in the plan of life, though there

was not a spark of envy in the breast of tender-hearted,

high-principled Molly Ashworth.

The visit of Adelaide's bridegroom-elect terminated to everybody's

satisfaction; and all the arrangements for the wedding had been made

in accordance with the wishes of the bride. She was to be married

from her father's house, and by a clergyman of the neighbourhood,

her father giving her away. Molly was to be her only bridesmaid; and

the only guests were to be the Helyars, with whom Lord Fenmore and

his friend Colonel M'Gregor and the Dowager Lady Fenmore had been

invited to stay when they came down for the ceremony.

It was a very pretty ceremony, and far more solemn and effective

than a crowd of bridesmaids in a city church would have made it. The

bride wore her bridal white with a wonderful drooping elegance.

Molly was in pale bright green, with clouds of tulle about her. The

old ladies were superb, Mr. Ashworth grave and dignified. The school

children, in a state of awe and wonder, were behind with osier

baskets full of flowers, and when it was all over they marched

before, with the schoolmistress at their head, and strewed their

flowers all the way between the church and the rectory.

When Molly and her father were left together at last, they felt a

certain sense of relief in that the affair was over, and yet neither

of them were particularly cheerful.

"I'm going to lay aside my finery," said Molly, "and then we'll

have a nice cup of tea, and perhaps begin to feel more like

ourselves, papa."

"Have you not been feeling like yourself, Molly?" said her father,

laughing.

"No, not a bit, just this minute I had the funniest feeling — that I

have been exactly in this situation before, left alone with you just

as we are now — everybody gone for good." She tried to jest, but there

was a huskiness in her throat.

"I wonder if I shall ever wear this dress again," said Molly,

looking down at her pea-green skirts.

"Of course you will," said her father. "You are going to visit Lady Fenmore."

"But I can't leave you, sir," said Molly, shaking her head.

"Then I must come too," said her father.

"But you can't leave the parish, sir."

"I can leave the parish as easily as you, I think, Molly. If I go

they will only lack their Sundays' service; if you go, you will find

that half the children have tumbled into the fire, and the other

half into the water, and that there was nobody to take them out.

Seriously, Molly," he went on, changing the subject and his tone;

"have you not noticed that I am growing an old man — that I am

failing, in fact?"

She looked up in his face with a keen pang. Was he really failing,

and had she never noticed it? He waited for her to speak.

"Oh, papa !" she cried, "not tonight, don't let me think that

to-night."

"My child," he said, tenderly, "I did not mean to hurt you. I do not

think I am going to leave you. I have, please God, some strength

left for His service yet. All I meant to say was that I must soon

have help. You have long been my curate, you know, but I feel that

I need help in the services, and you cannot give me that. I think we

can afford it now that Adelaide is gone. We shall drop the carriage,

of course. You don't mind that, Molly?" he asked.

"Not at all, papa. I would rather walk than ride any day," said

Molly. "And we could do without Jane," she added, entering into his

plans, though still slightly jealous of the help he was about to

seek at other hands than her own.

"Exactly," said her father. "Then I can keep a curate, for I have

saved all that you will ever need, my darling child, and it will

spare me longer to you I daresay, for I begin to feel the damp of

little Helyar? It gives me a feeling of oppression at the chest, and

my head is giddy at times."

"Oh, papa! why did not you tell me before?" cried Molly, with tears

in her great eyes.

"Time enough, I think," he answered, smiling, "when you take it so

to heart."

"But why did you not have help before? Oh, how blind we were not to

see that you needed it!" she went on.

"Now, Molly, be reasonable," he answered. "It is quite time enough

to be giving up half my work; but we shall set about looking for

this curate directly."

It was some time before Mr. Ashworth could find a helper to his

mind, the young men who presented themselves before him by letter

were so full of crotchets — so Mr. Ashworth took the liberty of

calling what they called their opinions.

"But," he said one day, in consultation with Molly, "I would take

the most crotchety among them if I only thought he had the root of

the matter in him — the true love in his heart. If the root is there

the fruit will come in its season. Some fruit is meant for bread and

some for wine, Molly; and it was the fruit of the vine He always

spoke of or, at least, oftenest and most pointedly spoke of,

something beyond and above the actual needs of the soul for bare

life — something that not only kept it alive, but

intensified that life."

"And yet, papa, He calls himself simply the bread of life," she

answered.

"Yes, my Molly, He is the bread and wine in one — the all in all;

but take you and me, His poor servants, I think we have brought

forth for these people perhaps only bare bread. We have been content

to nourish in them simple honesty and common decency. We have cared

for their bodies, and taught them to care for each other's bodily

welfare, and to trust in their Creator and Redeemer: but you could

fancy a Paul doing more for them; or, in quite another and a

different way, a john feeding them on quite other spiritual food,

and to far different and higher results."

"But John and Paul were saints and apostles," objected Molly.

"And saints and apostles are not to be expected nowadays, is that

the inference you make?" said her father.

"I suppose it is," said Molly.

"Then we are acquiescing in the modern notion, that Christianity is

somehow weaker, less of a force in the world than it was in the

early days. People do not confess this always, but the notion is in

their hearts. As for this young man, Montagu," he went on, "I think

I shall give him a trial. He will work, at least, for he evidently

thinks us in a benighted condition."

"I should fear he was terribly conceited," said Molly.

"No; I think he is an enthusiast rather. He sends me quite a little

history. He was educated with a view to the Church, for there is a

'living' in the family; but, just before

taking orders, he learnt to believe that such as he, entering the

Church as a mere profession, did infinite injury to Christianity. Then he read for, and was called to the Bar, living all the while in

the best and gayest of London society; and, lastly, he finds himself

called with a higher calling to fulfil his original destination. He

has recently taken orders, and desires for a time to be absent from

the scene of his former worldly pleasures. He desires, literally, he

says, to forsake all and follow Christ. Christianity, he thinks,

demands sacrifices as great of a nineteenth century clergyman as of

a first century apostle. He evidently favours us," concluded Mr.

Ashworth, "because we have nothing tempting about us."

Molly took his long and interesting letter, and read it without

further comment. When she had finished, she agreed with her father

that Mr. Montagu should be invited to Pendock.

He was, accordingly; and came, and saw, and conquered. The vacant

curacy was filled up on the spot. The next and immediately-pressing

question was where he was to live. There were no farms in the

forest, therefore there were no farmhouses where he could lodge;

the cottages were too mean, and the town was too far distant. The

only alternative was that he should remain at the rectory, where a

bedroom and a study could easily be found for him. He did, indeed,

propose to live down in the village; but he yielded to Mr.

Ashworth's persuasions, and to Molly's lighter raillery.

"We might build you a hut in the forest, or scoop you a cave out of

the cliff," said Molly; "but you would not find them quite as

comfortable as the room we shall give you; and then, as the room is

in existence already, there is a distinct saving of trouble."

Molly liked Basil Montagu at first sight; she found that with all

his self-denial, and it was rigid, he was no gloomy ascetic. He had

a wonderfully high standard of life and duty, but he could be jestful and innocently gay the while. He was not to be petted, as

Molly would have found it in her woman's heart to pet him; but he

was not bent on the mere self-will of needless sacrifice. "I am a

little afraid of the 'mint and cummin,'" he said once, "but I should

forget greater things."

The people took to the new curate wonderfully. He was more familiar

with them in a week than Mr. Ashworth had learnt to be in a lifetime,

and yet it was a familiarity which bred no contempt. If he was

wearied, he would sit down on their bench; if he was hungry, he

would eat of their bread, and, somehow, make it sweeter to their

taste. He never troubled himself to make things easy to them, but

would treat them to his deepest thought and richest eloquence. In a

dim way they understood it; they understood that this man desired to

give them of his best, of himself not of meaner things.

Of all Mr. Montagu's sayings and doings Molly sent an account to her

sister. There was little else she had to write about, while Adelaide

had so much. She had returned from her tour, to Fenmore Castle, and

was entertaining her husband's guests. Then they were going up to

town for six weeks, to come down again at Christmas, to entertain

more guests, among whom Adelaide hoped to see her father and Molly. And she was so happy. She had everything she could desire;

everything at Fenmore

was so much to her taste — so her letters ran.

And Mr. Ashworth and Molly went and saw for themselves that it was

so; that she was wonderfully happy, that the husband and wife

suited each other exactly; that their sky seemed for the present

without a cloud. Never in her life had Molly spent so gay and happy

a Christmas as this at Fenmore Castle.

But on the first day of their return, when she and her father were

left to their private and confidential evening chat, Mr. Ashworth

startled Molly by saying, with a sigh, "I see no change in

Adelaide."

"What a strange thing to say, papa!" exclaimed Molly. "What change

did you expect to see?"

"My dear," he said, "Adelaide has always been a puzzle, and very

often a pain to me. She is so good that I always expect her to be

better; but she brings no fruit to perfection."

"Don't say that, papa — look how perfectly sweet and patient

Adelaide can be. You know I am not always sweet and patient," said

Molly.

"No, my love; and yet I am more hopeful concerning your disturbance

than her quietest calm," said her father.

"Papa," said Molly, speaking hurriedly, "did you never think we two

were a little like Martha and Mary? I am Martha, you know; and I

always thought that she was rather hardly dealt by."

"No," replied Mr. Ashworth; "I do not see the least resemblance —

Mary was not absorbed in self-contemplation. Adelaide seems to me

more like the barren fig tree — not the one, thank God, that

withered under the curse of the Saviour, but the one that stood in

the vineyard, and was respited for yet another year. 'If it bear

fruit, well.' We are not told that the fig tree perished, being

found fruitless at the last."

Just then Mr. Montagu came in, and Molly hastened away to hide her

tears.

CHAPTER III.

WHEN their

Christmas guests had gone, Lord and Lady Fenmore preferred to remain

at home rather than go up to London. Adelaide had been very well

received in society, which had talked her over before she made her

appearance, made the usual number of blunders and misstatements

concerning her, and then accepted her at its highest estimate,

because she seemed to belong to it. It had reported her as a great

beauty, lowly born — a "village maiden" — when that exploded, she

was an old love of Lord Fenmore's, and her story was quite romantic. Then it saw her, and found out about her aristocratic relations, and

was satisfied.

But Adelaide did not care for society; she was in her element at

home. And what was that element? It was something very fair to the

sight — at least, to the first sight. Where Adelaide reigned there

was peace, to begin with, quiet and beauty were supreme. But round

her the air grew heavy with self-indulgence; gently, very gently and

slowly, it spread about her, centre as she was of a large household

— mistress of many destinies.

Her husband was the first to succumb to the influence. Parliament

assembled, but his place was vacant, though he had taken it with a

certain enthusiasm — resolved to throw what weight he could into the

scale of a wise but cautious progress. Adelaide did not care to go

up to town, and she represented it as such a bore, such a loss of

health and comfort, such a martyrdom, for such poor results, that he

was content to remain beside her, and let the great questions of the

day, as far as he was concerned, take their chance.

But it told through all the house, down to its humblest servant. The

housekeeper had been on the alert, with her well-disciplined staff,

to serve the new mistress as punctually and promptly as she had

served the old. But who could remain on the alert with Adelaide? Later and later had grown the breakfast hour, less and less used the

horses and carriages. Fenmore was in a fair way for becoming a

perfect Castle of Indolence.

If the Sabbath-day was cold or wet, Lord and Lady Fenmore inhabited

their luxurious rooms, and spent their time in reading and lounging,

and their example was speedily followed by the servants, and theirs

in turn by the young people of the village. The rector marked the

falling off, and was at a loss to account for it at first; but at

length he traced it to its source. The very same thing, he thought,

keeps Lady Fenmore sitting in her drawing-room, so beautifully pure

and calm, and Sally Lipscombe standing at her cottage door, unwashed

and hideous, the absence of one thing rather, and that perhaps the

noblest thing in life — effort.

It was evident that a deteriorating influence was at work, but what

was the rector to do? He was not a clergyman of Mr. Ashworth's type,

with a supreme sense of duty, nor of Basil Montagu's, with a

passionate self-devotion. He was a sensible and rather worldly man,

of energetic character, to whom exertion was wholly agreeable, and

who felt grievously vexed to see sluggishness and disorder gaining

the upper hand. But, again, what could he do? He preached several

energetic sermons on the

practical duties of Christianity, not one of which had the slightest

practical effect, and there the matter ended.

Lord Fenmore had taken up his duties as a landlord much in the same

spirit as he had taken up his duties as a legislator, with

enthusiasm. But here, too, his efforts flagged. There were bad bits

on his estate, and he had determined to see to them. The village at

the park gates was kept tidy enough in outward appearance, and at

one end of it there was a neat row of almshouses, inhabited by ten

of the oldest women in that or any other parish, all decently cared

for by the bounty of the Lord of the Manor; but hidden away here and

there were wretched tumbledown houses, unfit for human habitation,

where the rain came in through the roofs, and soaked through the

thin walls, inflicting on the inmates the lingering tortures of

rheumatism, or cutting them off in their prime with acute disease. And on the border of the estate there was a valley — a valley which

yielded Lord Fenmore four-fifths of his wealth, and yet looked

neither happy nor smiling, but a very valley of the shadow of death

— where all the cottages were wretched, and tumbledown, and dark,

and damp, and where human beings swarmed in ignorance and ill. It

did not belong entirely to Lord Fenmore, and the mines were not

worked by him; but still he held there almost unlimited power for

good, and, what was more, he had resolved to exercise it. He had

resolved to build and to plant gardens, and to favour these poor men

in their efforts, here as elsewhere begun, to try and raise

themselves by education and temperance to a higher level than that

of beasts of burden.

And Adelaide kept him by her side, with her reading, and her poetry,

and her music, and her refined tastes, till he almost forgot the

existence of Brookdale. Now there was a tree to cut down which

obstructed a pretty view, and now a grove to plant where a

foreground was wanting; here there were flower-beds to turn into

grass, and grass into flower-beds. It was always the same — little

trifles consumed their lives. They gave little parties, and went to

little parties in return; little friendships sprang up

between them and their neighbours, who found the new Lady Fenmore

"very sweet indeed." But all greatness was dying out of their lives,

all nobleness, because all self-sacrifice was gone, and they were

sacrificing to self instead. And let no one believe, or try to

believe, that Christianity can exist without greatness and

nobleness.

At Easter the Dowager Lady Fenmore paid them a visit, and went away

lamenting more than ever the fate of her son. She lamented, too,

over her neglected schools, and over her neglected village; for she

had had her own narrow sense of duty, and had superintended the

education of the children, put a stop to the quarrels which

sometimes rent the almshouses, and fought bravely against the

general disposition to slatternliness among the village matrons. Now

she saw with horror that Miss Johnson, the certificated teacher,

might neglect to instruct her charges to be content with the station

of life to which it had pleased God to call them, nay, might

inculcate feelings directly subversive of that precept, without

rebuke. That old Dorcas Green might, and did, lift her stick to

Nancy Withers; and Nancy Withers might, and did, pull off Dorcas

Green's cap unreproved; and that Sally Sole and the rest of the

maternity of Fenmore village might stand in their doorways unwashed

and unkempt for ever, without the least chance of interference.

Later in the season Lord and Lady Fenmore went up to London, and

Molly joined them there, coming back from her ten days' visit

somewhat sad and thoughtful. Her darling Adelaide was sweet as ever;

but with her eyes opened, as they had been by her father's words, she

did not fail to see that her sister's life was one of pure

selfishness. Every one about her was absorbed in its details in the

arrangement of her rooms, of her flowers, of her dress. Molly was

forced to acknowledge that the new

happiness, the great opportunities which had come to Adelaide, had

had no effect; even the emotions they had raised had passed away. She was sweetly satisfied instead of sweetly discontent — that was

all.

Life in the forest went on much as usual. No one missed Adelaide

save Molly. She missed having to do so many little things for her,

she missed her exactions — even those which had hindered her most in

the matter that lay nearest to her heart.

"Certainly, Molly," her father had said to her on more than one

occasion; "you illustrate the truth of the words, 'It is more

blessed to give than to receive.' You gave all and received nothing,

as far as your sister was concerned, and it seems to have

constituted your greatest happiness?"

"Next to doing things for you, papa," she answered once. "Yes, I

suppose it is more blessed to give than to receive," she went on,

after a pause, during which Mr. Montagu had joined them, "and yet

you know it is the receiver who confers the greatest blessedness

in that case."

"I shall begin to be afraid of you, Miss Ashworth," said Mr.

Montagu. "You are an alarming sophist."

"Am I?" she answered, in a half-mournful tone, without looking at

him.

He was looking at her fixedly and tenderly.

There was, in truth, a sadness stealing over Molly. Adelaide was

gone, and her father had now another companion far more helpful than

she could ever be. Mr. Ashworth had never had a son, and Basil

Montagu seemed to take the place of one, for he was a son who had

never known a father. There was something very touching in the

attachment which had sprung up between them — the young man

evidently looking up to the old, and yet the old man returning the

reverence in another form. They often did double duty for the sake

of companionship, the two going together where one would have

sufficed.

"She stretched out her hand for the letter, which he

had

evidently finished, but he did not give it."

Autumn had come again. It wanted but a month to the anniversary of

Adelaide's marriage, when one morning at breakfast Mr. Ashworth

received a letter. It was from Fenmore, for Molly had looked at it

as it lay beside his plate, and she was anxious that he should open

and read it — read it to her, or hand it over to her; he always did

one or other. It was from Lord Fenmore, too, and he only wrote on

the more formal occasions, leaving the correspondence to his wife,

and sending affectionate messages through her.

"Papa, what is it?" exclaimed Molly, as he perused it in silence,

and with an altered and alarmed expression growing on his face. "Oh,

papa, what is it?" She stretched out her hand for the letter, which

he had evidently furnished, but he did not give it.

"It is sad news, my love," he replied, "I fear your sister is very

ill indeed."

"Let me read it," she pleaded, with outstretched hands, and Mr.

Ashworth withheld no longer.

Lord Fenmore wrote in haste, and in evident distress. Adelaide was

ill — had had a shock of some kind. Would one or both of them come

without delay?

"Let us both go, papa," cried Molly, whitening to the lips, as she

always did in great emotion.

"Yes, we will go together, and at once," replied Mr. Ashworth,

soothingly. "Mr. Montagu, I can leave everything in your hands?"

"Oh, yes," replied Mr. Montagu, "leave everything to me. I hope,

however, it is nothing very serious."

"I do not think Lord Fenmore would have written as he has, if it was

not deeply serious," replied Mr. Ashworth.

But it was far more deeply serious than they imagined. Adelaide was

living — was likely to live, might live for years — but yet life for

her was over. Pain even was over for the time — though it had been

terribly acute, and might recur again and again, pain was over. But

she was powerless, stretched upon a couch from which there was no

hope that she would ever rise again. The spine was affected, and she

had lost the use of her limbs. The doctor had given the strictest

orders that she was not to be

moved.

And so she lay there in the room into which they had carried her

when she had fallen a fluttering heap on the terrace in front of her

home. It was a ground floor room, and looked from the terrace over

the lawn and into the park — a lovely and noble scene; but she lay

there, darkened in her corner, not caring even to see the light,

with closed eyes mostly, suffering, suffering — all the props of her

life had given way at once. Her readings of meditation and prayer

and hymn seemed to have left a blank in

her mind. Her soul seemed to her to be like her body, deprived of

power and motion. But what Adelaide thought in these first days of

anguish she spoke of to none — not even to her husband. It would

almost have been a consolation to him if she had murmured a little —

desired this or that to he done for her, been impatient and

exacting. But no; she seemed entirely absorbed in suffering.

Mr. Ashworth and Molly had been prepared to see her, but it was a

terrible shock to both. She was so like one already dead, lying

there so utterly white and still, with her folded hands and closed

eyes. They hushed their steps as they drew near her, and strove to

repress their grief; and because Molly's would not be repressed any

longer when she met the suffering eyes of her sister after she had

stooped and kissed her, she had been led gently but firmly from the

room by her sister's husband.

But after that Molly took her place bravely by Adelaide's side, and

would not be drawn away again; and the days passed on, bringing no

visible change. Mr. Ashworth returned home, and left her there, and

yet her presence seemed but little comfort to the invalid.

It was an infinite comfort, however, to one person, and that was to

her sister's husband. He scarcely ever left the house, roaming from

room to room, unable to do anything, and Molly would come forth at

intervals to cheer and sustain him. Hope is hope, if even it is

vain; and Molly could not relinquish hope. She even ventured to

whisper hope to Adelaide; but she put it from her — Molly was almost

dismayed to see with what vehemence.

One day Molly was sitting beside Adelaide alone. The nurse was in

the grounds, Lord Fenmore in the library, a general hush prevailed. Molly became sensible of it suddenly, and fancied she could hear her

heart beat. She would fain have read to Adelaide; but when she had

offered to do so Adelaide had declined.

"Molly," said her sister, in a voice so clear it made her start to

her feet on the instant.

"Yes, dear," said Molly, coming to the front.

"This is the anniversary of my wedding-day, is it not?"

"Yes," said Molly, with a violent effort of self-suppression, which

suffused her face with crimson. Longing as she was to fling her arms

round Adelaide, and sob, "You poor, poor darling!" she answered

only, "Yes."

"Where is Geoffrey?" said Adelaide next.

"About the house somewhere," answered Molly. "Shall I go and fetch

him?"

"What is he doing?"

"Nothing," answered Molly. "Shall I go?"

"Not yet," she said, and paused.

She closed her eyes again, and murmured, as if to herself, "She that

liveth in pleasure is dead while she liveth." Then she looked up

once more, with a strange new brightness, into Molly's face, and

said, "But now I shall live in pain, Molly; but it will be life —

not death."

"Thank God, darling," said Molly, falling on her knees.

"I do," said a sweet voice, out of the silence.

Neither Adelaide nor Molly knew how long that silence lasted, but at

length it was broken by the former saying —

"Now, Molly, bid Geoffrey come here."

She went in search of him. He was in the great dull library, but he

was not reading. Those loaded shelves contained nothing that could

interest him. At that moment nothing interested him; he felt as if

all his possessions had crumbled into dust. To feel so utterly

powerless and impotent was terrible. He was telling himself that the

calamity that had befallen him was worse than death, almost wishing

that he and she could be laid together without delay in the old

family vault, which had opened so often lately, and that all that he

had might go without further delay to his almost unknown, distant

heir.

Thus Molly found him, and she hastened up to him, her great dark

eyes full of unshed tears. She laid her hand upon his shoulder, and

made him look at her, as if that look of hers would communicate

something which words would fail to speak.

"What is it?" he said, almost impatiently, for the look had

communicated all that he was most unwilling to receive —

consolation, hope, joy.

"Something has happened to Adelaide," she said. "There is a great

and happy change."

He started up. "She is not dead!" he exclaimed.

"No; not dead."

"Can she rise? Is she better?" he went on, excitedly.

"No; the change is not an outward one; but it is as great as that. She bids you come to her."

He rose to go.

"I will come when you call me," said Molly, taking his place. "Go to

her alone."

Adelaide held out her hand to her husband with a smile; every trace

of suffering except the marble pallor banished from her face. "We

must begin our life today, Geoffrey," was her greeting; "our real

true life. I am not going to die."

"No, my darling," he said; "but to live thus —" His voice broke with

the pain of it.

"Geoffrey," she said, solemnly, "I wished at first to die; it seemed

hard that I could not. My life seemed only a dull, terrible,

hopeless, meaningless misery as I lay here; but now I understand. I

was not living then, I am living now. I understand it all, I might

have done so much, and I did nothing, less than nothing, in the

world, for I lowered your life and the lives of others. Nay, do not

deny me. Now there is one thing I can do; let patience have her

perfect work in me, but I must no longer hinder others. I must no

longer hinder you, Geoffrey; you must live to God."

She stopped exhausted. He sat and held her hand in his. At intervals

they spoke. They settled what their plans for the future must be. An

hour after, when Geoffrey sought his sister-in-law, and found her

where he had left her, his whole aspect had changed. He too had been

thrilled through and penetrated by a strange newness and sweetness.

And from that day life at Fenmore underwent a swift and silent

change. She who lay in her room there, motionless as a statue,

helpless as a new-born babe, was the soul of all the healthful

movement, all the helpful exertion of which it was the centre.

Geoffrey and Molly worked hand-in-hand. She would not allow them to

stay by her except in their hours of rest and leisure; but they came

to her to be encouraged in failure, and invigorated in weariness.

"You know I have time to think," she would say, or, "You know I

cannot be discouraged, because I never attempt anything."

They brought her reports of all they did — of every family raised to

self-respect and cleanliness by a decent home; of every child, in

black Brookdale especially, rescued from ignorance and premature

toil, and sent to fulfil the happy school-days which make bright as

it ought to be the beginning of life. And through all the household

the same spirit permeated, not perhaps so quickly as the spirit of

indolence and selfishness had done, but still it leavened all more

or less; and duty was once more enforced, only with higher and

gentler sanctions.

So the winter wore away and the spring came. The trees wore the

delicious misty green of the budding time, and Adelaide's bed was

drawn nearer to the window that she might see it, see the spring.

And she did see it, as she had never seen it before, and not a

murmur escaped her as she watched the glorious earthly resurrection,

that not a spark of its fresh vitality fell upon her; that while the

bare brown trees put forth their buds by countless millions, no

power stirred those poor limbs of hers.

Molly had never been at home, except for a few days at Christmas. Her father had been only too glad to spare her to Adelaide, and he

had rejoiced unfeignedly at the work which was doing at Fenmore,

therefore he had even urged Molly to stay. The old Welsh nurse, who

had been with him since Adelaide's birth, kept house for him and Mr.

Montagu; and he insisted that they were happy and comfortable.

But now it seemed as if Mr. Ashworth was longing for Molly back

again. He doubted if Mr. Montagu would remain at Pendock; the

incumbent of the family living was sick. Mr. Ashworth thought it

would be Mr. Montagu's duty to accept it when he died; it would not

be his duty to bury himself down in the forest, entirely forgetting

that that was what he himself had done. Of course he would miss

Basil much; he had been like a son to him, therefore he was bound to

urge his going from him all the more if it was for Basil's

advantage, or, rather, the advantage of Basil's cause, lest

unconscious self interest should favour his desire to stay.

All this Mr. Ashworth wrote to his youngest daughter; and there was