|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XXV.

OUR NEW HOME.

THE record of to

the many months that follow is but the record of a sickroom, with

its fluctuations of depression and of hope. How the summer passed

into autumn, and the autumn into winter, and the winter into spring,

bringing day by day a measure of health and strength to our invalid,

and to us lessons of hope, and love, and patience, and thankfulness. There is record of the day when he could once more leave the dreary

confinement of a single room to which the excitement consequent on

seeing Edwin and Doretta reduced him, when he was carried

downstairs by Ernest and Claude. Then of the day when he could walk

down slowly by himself, and get out into the garden. Then of the

time when he could be allowed to go out unattended, and the traces

of his illness were almost obliterated to strangers, and only to be

seen by us in the stiffened gait and straitened speech. At this

point he became stationary, and the doctor strongly advised our

going into the country. Aunt Robert would have been very glad to

have us—that is papa, Aunt Monica, and I; but we did not think it

would be desirable for papa to go to her, so near the place which

must awaken many painful emotions, and we have never suggested it to

him. Both Ernest and Lizzie have been at Highwood since papa came

home. I have never been away at all; Aunt Monica and I have not once

left him. When we go, we must go together.

Edwin has never brought Doretta to see us again. At intervals he

calls to inquire after papa, but he does not often see him. Lizzie

and Aunt Monica, but Lizzie most frequently, go to see Doretta. Baby

was very ill one day, and she sent for them, and since then another

little one has come, a girl, and Lizzie is more in request than

ever.

Lizzie reports that Doretta is in high spirits at present. She has

long been wanting Edwin to take a house, and furnish it for her,

alleging that if he should be taken from her, she would have nothing

to fall back upon. She does say the most outrageous things. And at

length Edwin has yielded to her wish. She has persuaded him that it

will be quite as cheap as living in lodgings, but she is very

mysterious as to their ways and means, and as to where the money is

to come from which is to furnish the new house. She tells Lizzie

that she need not ask, as, at any rate, they will not be indebted to

their fine friends.

We had taken lodgings in a pretty cottage on the Sussex coast, and

Aunt Monica and I had accompanied papa thither. But we were not

destined to remain long in our new quarters. One morning Aunt

Monica, having sat down to breakfast with that tender pink flush on

her thin cheek, which always faded as the day advanced, opened the

letter beside her plate, and quickly laid it down again, all white

and trembling.

My father sat opposite, and did not appear to notice it, and I could

only wait, with palpitating heart, for what I feared were fresh

tidings of evil.

It was only for a moment. Then Aunt Monica rose from her chair and

went over to my father's side, and laying her hand softly on his

shoulder, while she put the letter into his hand, she said the one

word, "Henry—" He looked into her face and finished the brief

sentence for her—"is dead."

We are busy preparing for the change, perhaps the greatest change of

all that has taken place in our lives, changeful as they have been. My father has already been down to Highwood and provided for the

funeral, while we are getting ready suitable mourning. We are to be

present when this uncle of ours is laid in the family vault. My

father will omit no honour which he thinks ought to be paid to the

dead. I do not believe it is a mere matter of family pride with him;

I fancy he feels, besides, the natural sorrow and compunction which

men of generous impulse feel towards a fallen enemy. As for us, we

may put on mourning outwardly, but we cannot help rejoicing, not

over the event itself, of course, but over all that it brings to us. Our father restored to the home from which

he has been so long a

stranger, and from which he was harshly, if not unjustly banished in

his youth; Aunt Monica, returning to the same old home, to be repaid

for all the sacrifices she has made for us by taking the foremost

place in our hearts, as well as in the new household we shall make

there, just when she might have been turning her back upon it and

seeking for some place in which to spend her solitary days. It has

all turned out so happily that it is impossible for us to sorrow;

only Aunt Monica is really sorrowing, and she is grieving not so

much for what is, as for what might have been.

Once more we are at home in the midst of entirely new surroundings. It is indeed a changed scene into the midst of which the river of

our lives has borne us.

On a hot July day our whole party, clad in funeral black, started

for Highwood. After a short journey by rail, we stopped at a little

station, where a carriage and pony phaeton awaited us. Papa and Aunt

Monica got into the former, as also did Lizzie and I, leaving the

latter to "the boys." No longer boys, though the old name will come

uppermost, sadly reminding us of the time when there was no

estrangement between them. I wondered just then if our uncle's death

would bring about a reconciliation, and I was glad of the

arrangement which had thrown them together and alone.

We drove along a broad road, shaded by trees, and ascending and

descending in long gentle slopes. Soon the enclosed fields receded,

leaving waste green corners, in a prodigal fashion which gave one a

delightful sense of space and of freedom, that feeling of there

being enough and to spare of the good things of Nature which

refreshes the souls of the dwellers in pent-up cities more than

anything else perhaps. Here they only formed a threshold to the

loveliest of sylvan scenes.

We were nearing a village set in the midst of crowning and

encircling woods. The woods showed darkly green above the yellowing

harvest-fields, and the round white clouds seemed to repeat the

outlines of the masses of foliage upon the deep blue of the sky. The

village lay warm in the sunshine, and the sunshine rested on peeps

of white and creamy wall, laced with pear-branches hung with

ripening fruit; it basked on red-tiled roofs and glanced through

orchards full of gnarled old apple-trees to reach the red apples and

make them glow among the shrivelled leaves; but its full blaze fell

upon the central green, where it was flashed back from the mirror of

a pool as clear as crystal.

The sunshine and the scene, so full of the rejoicing life of Nature,

was in strange contrast with our errand and the sombre garments we

wore. Skirting the village, we passed through a pair of iron gates

thrown open to receive us by an old couple who stood bobbing and

ducking at the lodge door; and I heard the woman say, "Miss Mona—God

bless her!"

Under the noble trees, we swept up the avenue, and stopped in front

of the mansion. It is not old Elizabethan, or old anything in

particular, but a plain well-built house, long and rather low, with

only two storeys—the lower containing the public rooms and offices,

the higher the bedrooms and dressing-rooms. The house is set upon a

little hill, surrounded by lawns, and flanked with trees, the upper

windows looking out over the undulating forest; but its aspect when

we first saw it was anything but cheerful. The drawn blinds gave it

a peculiar blank look—a look as if it declined to welcome us within

its walls.

The servants were standing in the hall, also in black, waiting to

receive us, as we entered softly and silently, knowing that, within,

the master of the house lay dead. Aunt Mona's tears fell on the

threshold, and the sight of her weeping made the women weep. It was

altogether a chill and sombre home-coming, and I will not dwell upon

it, nor yet upon the morrow, when we saw our unknown uncle laid in

the family vault, in the midst of a concourse of strangers.

Among those who came to the funeral was Mr. Winfield, but I cannot

say that his presence added to the solemnity of the occasion. He has

a habit of whistling when in perplexity or anxiety, and, being

anxious to preserve the proper amount of gravity, he made one or two

attempts, and when suddenly recalled to the consciousness of

impropriety by the frowning stare fixed upon him, became so red in

the face that I dared not look at him.

All the next week we received visits of condolence. Aunt Monica and

I had to stay at home for the purpose; papa and Lizzie taking leave

of absence, and Ernest and Edwin having returned to London. Mr.

Winfield came, telling us, to our great relief, that he was left

alone for the present, Mrs. Winfield having gone up to London with

Edith.

But the whole neighbourhood is thickly studded with country seats,

and we seem to have some pleasant people near us.

I am delighted with the Misses Amphlett. They are the sisters of a

neighbouring baronet, and one is deaf and the other lame, and both

are quite poor; but not only in spite of, but because of these

drawbacks, the happiest of mortals. Each is constantly trying to

supplement the other's deficiency. Miss Bell is constantly occupied

in shouting to Miss Nancy, and Miss Nancy as constantly employed in

lugging Miss Bell along. They are full of life and energy, and

delight in making ends meet.

It is wonderful what they do with their small income, not in the way

of keeping up appearances, but of securing actualities in the shape

of comfort and niceness.

They live in a neat little cottage close to the village, separated

from the road by a garden hedged with yew and laurel. Their domestic

economy is peculiar, for they have two maids, one of whom, Aunt Mona

tells me, is generally the most refractory girl to be found in the

parish. The old ladies fondly think they can reclaim her to ways of

virtue and order by the authority proper to their age and rank, and

no amount of insolence or deception on the part of their

protégées can disabuse them of their belief.

"They have a profound faith that they have been planted here to

assert the blessedness of a social order," says Aunt Mona. So Miss

Bell and Miss Nancy promenade the village daily at the slowest of

paces, to exercise their authority. "Unpaid members of the force," a

neighbouring magistrate calls them.

I have already been with them on their rounds, and the very dogs of

the village seem to fear their stout parasols, and the slatterns

curtsey at their doors, and are repaid for their courtesy by kind

inquiries, the answers to which are echoed by Miss Bell to Miss

Nancy in tones which have the effect of enlightening the whole

community on the private affairs of the parties interrogated.

There seems to be a general disposition to make friends with my

father, which he, however, is far from unreservedly returning,

appearing to prefer to hold somewhat aloof.

The Rector of Highwood came to call upon him, and to Aunt Mona's

great distress was closeted with him for more than an hour; and all

that transpired concerning the interview was the simple announcement

that he had thought it proper to state his views to Mr. Lloyd, that

the ground on which they might hereafter meet might be unmistakable.

But what was our delight and astonishment when the very next Sunday,

being our first Sunday at Highwood, my father accompanied us to

church, quite simply and naturally. When we came down we found him

waiting for us in the hall, with one glove on, and the other in his

hand; and he helped us into the carriage, and then stepped in

himself. Arrived at the church, he led the way to the family pew, in

which he had not sat since he was a youth, and remained throughout

the service an attentive and reverent listener.

Aunt Mona took his arm as they left, and there was a sweet content

on her face as she looked up to him, saying, in a low voice—

"Thank you for coming with us, Benjamin."

"You have Mr. Lloyd to thank," he answered, hastily, for he was the

most silent of men. "If I had always been treated with equal

consideration, I might never have left the old ship."

After a pause, he continued—

"Yes, he made me see that one belongs to it as much as one belongs

to one's country. One is bound to sail under the right flag, you

know—to stand up to the enemy, even if one can't agree on every

point with one's commander. And I have lived long enough, Monica, to

see for myself that the side you and some others I know

are on is the right side, after all."

The Rector of Highwood had not impressed me greatly, but he was

evidently a sincere and amiable man. He had been at Highwood for the

last twenty-five years, and had made himself generally liked, though

it was some time before I could account for Aunt Monica's loving

regard for him, even with the help of her reading of his life and

character.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXVI.

THE RECTOR OF HIGHWOOD.

THE

REV. CHRISTOPHER

LLOYD, by no means an

old man yet, had, as a young man, been considered a special

favourite of fortune. He had been singularly handsome, he was

well connected, and one connection was in a high clerical quarter,

from which promotion was to be expected. He had married a

beautiful woman, possessed of the private fortune which he lacked,

and which his friends said was just sufficient to make him

independent. According to Aunt Monica, they ought to have

added, save of his wife. Sanguine individuals among them

predicted that he would undoubtedly die a bishop; but not the

slightest step towards such a desirable result had been made when

death visited the high clerical quarter, and the vista with the

bishopric at the end of it, closed for ever.

Mr. Lloyd had not been bitterly disappointed. He was

not ambitious by nature; but humble, affectionate, and unselfish.

Perhaps he thought, says Aunt Monica, that his son, then in the

nurse's arms, would be a great man, a dignitary of the Church; it

would be better than being one himself, and far less troublesome.

It was a pity for Mrs. Lloyd, she added, who would have borne being

a great lady, who, indeed, found it difficult to be anything else,

and it had made her husband anxious, as if he had disappointed her

in some legitimate expectation, that as much as possible of their

joint income—and her share of it was twice as great as his—should be

spent upon her personal requirements. And these requirements

were all of the most perfect order. She could not bear

anything that was rough, or coarse, or inartistic. The pillow

on which she laid her cheek was of cambric, edged with lace.

Whatever touched her, or was touched by her, must be smooth, soft,

and beautiful. She was never over-dressed; but all she wore

was pure, fresh, and dainty. Cashmere, silk, and cambric were

the only fabrics she liked, and she would not have worn other in an

episcopal palace. "Beatrice had never been accustomed to

anything inferior," her husband would say when choice of anything

for her devolved upon him.

As for their children, Aunt Monica says that Mr. Lloyd has

taken all the trouble concerning them. Beatrice could not be

troubled with them, he would say; she had not been accustomed to

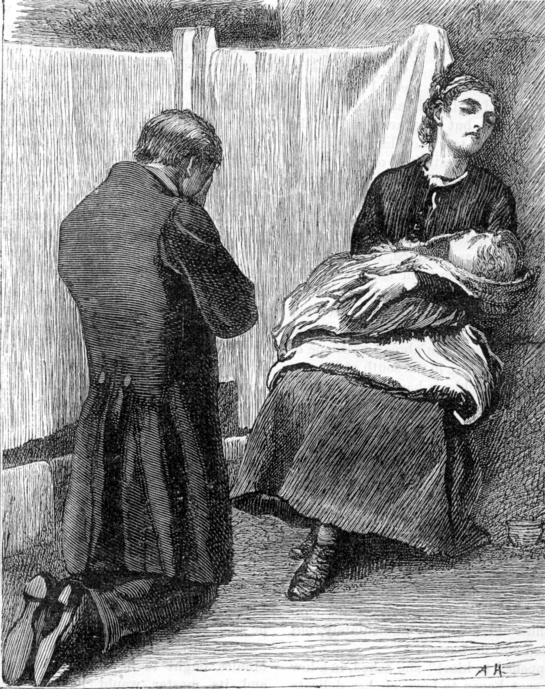

children. Their first child was a boy. Mrs. Lloyd, it

seems, did not try to get accustomed to them. She did not

nurse her boy, but got a young mother from a maternity hospital to

do it for her, who rocked him to sleep with unhallowed songs, while

she was singing sacred words to heavenly music in the room below.

Then, after a few years, a girl was born, and no more followed.

Mr. Lloyd, on the contrary, was exceptionally fond of

children. He was oftener in the nursery than Mrs. Lloyd was,

and indeed, those nursery days were, Aunt Monica believes, the

happiest of his life. "I wonder you can be so absurd, my

dear," his wife would say, after finding him lying on his back as

Gulliver, or going on all fours as a great bear, with the two little

ones by his side. And of course it had its absurdity from Mrs.

Lloyd's point of view, for a man who had had the remotest prospect

of a bishopric, to be down on his hands and knees playing at bears.

At the age of eleven, Charles Lloyd had been sent to school.

Up to that time his father had taught him. No very easy task,

says Aunt Monica, for he was a self-willed and self-indulgent boy.

Mr. Lloyd had taught Linnet too, but she had given him not the

slightest trouble; not that Linnet is particularly docile, says Aunt

Monica, but she was and is the embodiment of bright intelligence and

sprightly affection.

I long to see this Linnet, of whom Aunt Mona has often

spoken, and always speaks so fondly. She bears not the

slightest resemblance, it appears, to either father or mother.

Her name belonged to her grandmother on the father's side—"a very

absurd name," her mother had said; but she did not insist on a finer

one, as the child would be Miss Lloyd.

Later, when Charles Lloyd was settled at Eton, Mrs. Lloyd

determined that Linnet must go to school. Could he not go on

teaching her? Mr. Lloyd had pleaded, with just a little

instruction from some one—his wife he meant. But Beatrice had

not been accustomed to teaching, he explained to Aunt Mona, and so

his plan, as well as the proposal for a governess, was negatived,

and Linnet was sent to school.

Mr. Lloyd took all the trouble of selecting one, and he

himself took her there. The stranger, says Aunt Mona, into

whose hands, after searching inquiry, he gave his treasure, was

moved almost to tears to see the man tremble so when the child

sobbed upon his breast at parting, and she cried altogether when he

came for her on the morning of her first holiday, and received her

into his arms with a heart-hunger in his face.

It is impossible to hear of Mr. Lloyd's love for Linnet

without feeling an affection for him and understanding him better.

He is one of the people who are always misunderstood; and but for

the danger of doing him injustice, I do not think Aunt Mona would

have allowed me to know so much of his private history, involving as

it does so much of blame to his wife.

The years had passed since then with but little change.

Mrs. Lloyd was settled at a distance from her family and friends,

but she endured the comparative dullness of Highwood with much

equanimity. It was not society she had been brought up to

please; it was herself.

When I first saw her she was reclining on an easy-chair in

her own drawing-room, dressed in a graceful and somewhat youthful

fashion. Her muslin gown showed a glimmer of a fine white neck

and beautifully moulded arm. Her hair had scarcely a touch of

grey among its glossy folds, and there were no lines on the small

well-shaped forehead. The delicate features still retained

their perfection; and it was only round the mouth, and at the

corners of the eyes, that wrinkles told the tale of half a century

of mortal life.

There had, however, been one change in their conditions of

life, which had stood instead of a great many, and that was the

necessity for a curate. Mr. Lloyd had been ageing rapidly, and

a rather severe attack of illness had recently rendered such help

imperative. He would gladly have dispensed with it, but found

himself unable to do so; for the present curate was the third of his

line, and it had not been a brilliant one. He had clearly

missed his vocation in the art of healing. Besides bringing

the poor people about the rectory in the most reckless fashion had

pervaded the house with the unpleasant odours which issued from his

room, as he brewed the potions which he expected the sick to drink

down.

He was constantly treading upon forbidden ground.

Unfortunately there was much forbidden ground in the rector's

domestic paradise. His fussy interest in household matters,

qualities of food and wine, domestic expenses and arrangements,

etc., would have led him to discuss them with pleasure; it seemed

hard that he should not be allowed to do so, since they were left

entirely to him. Mrs. Lloyd had never been accustomed to

anything of the sort. Then his harmless gossip about the

parish and the poor had been forbidden likewise, and the curate

would persist in giving details of all the troubles which befell the

rector's flock. This most troublesome man was never out of the

cottages where any infection happened to be going. Mrs. Lloyd

could not be expected to put up with it. She had never been

accustomed to such things. He would have turned the

drawing-room into a dispensary, and thrust a pestle and mortar into

her dainty hands (as he did to his wife when he got one), and she

was first cousin to a countess. But, worse than all, the most

distant allusion to religion was tabooed. Mr. Lloyd could not

open his mind on the subject of sermons, if indeed he had cared to

do so. And all this had been done, without any harshness, by a

steady gentle pressure, acting as sweetly and unconsciously as one

of the forces of nature.

It struck Aunt Monica, as the present curate of Highwood is

on the eve of departure, and his place has not yet been filled up,

that Claude might like to come here. She thinks Mrs. Carrel

and Clara would like it, and would come too, if a house could be

procured for them, and she has written to Mrs. Carrel to propose it,

and, at the same time, mentioned the matter to Mrs. Lloyd.

Mrs. Lloyd was graciously pleased to approve of Claude, as far as

Aunt Monica's recommendation went. She hoped he was a

gentleman, concerning which we could assure her. According to

her, the present holder of the office was not. "Did you ever

see such hands?" she said. "They cover his plate completely,

and you would think he had never worn a pair of gloves in his life.

I cannot tell you how thankful I am that I shall not be obliged to

dine daily in company with them."

This was not, it seems, exaggeration. To such a

complexion had she come, through sheer self-indulgence, that the

poor curate's big brown hands would have been a positive and growing

annoyance to her, and would have actually overshadowed her every

meal.

Contrary to my expectation, Claude seems desirous of making

the change. His health seems to be suffering where he is.

His mother writes full of thankfulness for the prospect. She

evidently urges it, and promises to follow him to Highwood whenever

they can get quit of their present abode, and he feels settled

enough to allow of their coming to him. I have done nothing to

forward this. It is for Claude to determine whether he would

care to be so near us. It cannot hurt Lizzie. I have

kept his secret, even towards himself have kept utter silence

concerning it. I feel sure he has not ceased to love her.

Does he love her in despair, or hope? I almost fancy he might

hope to win her. She cannot be suffering. I believe she

is quite happy. Perhaps it was only a childish fancy which the

brave child conquered for my sake at once and for ever. Thank

God that she has not suffered—not as I have done. She is full

of sweet content, and takes up every duty cheerfully and simply.

Claude has been in communication with Mr. Lloyd. The

latter was good enough to go up to London and see him, and Claude

has come down for a final interview with his rector before entering

on his duties. He is staying with us for a day or two;

yesterday he dined at the rectory. He is charmed with Mrs.

Lloyd. Only the day before Mrs. Lloyd had been lamenting the

necessity for receiving him, but then she received him with the most

perfect sweetness and cordiality; while Mr. Lloyd, who came into the

drawing-room somewhat late, seemed oddly hesitating and uncertain.

Mr. Lloyd, who is very short-sighted, has an unpleasant way

of looking at the contents of his plate, as if he were very much

engrossed with the food set before him, and Claude, like everybody

else, at first sight thinks him very inferior to his wife. He

was deprecating and fussy, too, while she sat at the head of the

table the very picture of serene repose. The servants, it is

true, waited on her assiduously, indeed, seemed so occupied in

supplying and anticipating her wants as sometimes to neglect their

master, but Claude set this down to her superiority. They

liked best to wait on her, of course.

Had Claude never seen a well-bred woman before? We were

tempted to ask him the question. His mother, a gentlewoman by

birth, was that, and much more; but he was very sensitive to

perfection of any kind, and Mrs. Lloyd's beauty and breeding were

very perfect in their way.

He was glad, however, to be left alone with his rector for

the rest of the evening, for he wanted to speak about his duties and

the part he was expected to take in the services. He had been

aware that Mr. Lloyd had kept him aloof from the subject in his

nervous way during dinner. But as soon as we ladies were gone,

and Claude had seated himself, after closing the door behind us, he

appeared more at his ease, and, as if relieved from some restraint,

lay back in his chair, and became at once familiar and kindly.

Mr. Lloyd began on the topic of lodgings, which we had

already discussed with Claude, Aunt Monica pressing him to stay with

us till he could settle himself comfortably, and he declining firmly

to be our guest for more than a few days, and engaging Aunt Monica

to provide for him in the village.

"My curates have hitherto lived under my roof," said Mr.

Lloyd, "and I should have been glad to arrange it so for you also,

as suitable accommodation is difficult to find here; but the fact

is, it disturbs our plans to have any one with us. Mrs. Lloyd

is very fond of quiet, and we must keep rooms for my son and

daughter, both absent at present. Then we have had to throw

two of the rooms into one, as Mrs. Lloyd found her bedroom

inconveniently small, and as her maid sleeps on the same floor,

there are only the servants' rooms left."

All this was said in a rapid yet hesitating way, Claude in

vain attempting to assure him that there was no need to trouble

himself. There were too many reasons in the rambling apology,

which of course set Claude thinking there was no reason at all,

except that he was not wanted—a very sufficient one, which he felt

that he had no right to resent.

Having expressed his polite acquiescence in all that Mr.

Lloyd had said, Claude asked, by way of saying something practical,

if there was any place in the village, or any farm-house in the near

neighbourhood, at which he could lodge. He was not at all

particular, he said. He had begun his work as an East-end

curate, and had lodged in Whitechapel.

"A Bluecoat boy takes some time," he added, "to acquire

fastidiousness in regard to bed and board."

"True, true," Mr. Lloyd replied, with a preoccupied air;

"still, I wish I could have found something better for you."

"Then you have found something?" said Claude.

"Well, yes," was the answer, "there is one house in the

village where you could have rooms; a nice little parlour and

bedroom, but I don't much like your going there. The mother

and daughter are very well; they come to church regularly.

Indeed, Mrs. Bower once did me a great service, a very great

service; saved my child's life, in fact. But the man, Mr.

Bower, bears a very bad character, and he is a complete atheist."

"Is there any need for us to avoid his house on that

account?" said Claude. "There is a great deal of infidelity

abroad," he added, "and we ought to lose no opportunity of meeting

unbelievers on their own ground, I fancy."

Mr. Lloyd looked up in alarm. "I hope you are not

inclined to controversy, Mr. Carrol," he said. "It is a thing

I never meddle with; it seldom does any good; and there is no need

for it here, I assure you. With the exception of John Bower,

and—and one or two others," he added, with greater hesitation than

ever, "I do not think there are any infidels in the parish; men like

John Bower can't understand, and the educated unbelievers of our day

won't listen to evidences. The only evidence they can both

alike understand is a Christian life. Let us set them an

example of that." He spoke these last sentences with a force

and dignity contrasting strongly with his former manner.

"I preach the morning sermon myself," the rector went on;

"you will conduct the rest of the service, and preach in the

evening. The congregation in the evening is entirely composed

of servants and villagers. You will have to preach the Gospel

to the poor."

"I could not have nobler or more congenial employment,"

Claude replied.

"You can see that controversial subjects would be useless, if

not hurtful," Mr. Lloyd continued, "and that plain practical

Christianity is all that is required."

"A vast enough requirement," thought his hearer, but he kept

silence on the point.

"Do you think I should be subjected to annoyance if I went to

this person's home to lodge?" he asked, changing the subject.

"No, I don't think so," replied the rector; "though Mrs.

Dutch, at the 'Great Hart,' won't allow him to frequent her parlour,

on account of his blasphemy, I believe. I don't know what to

say about it. Perhaps you had better see Mrs. Bower, and judge

for yourself."

The responsibility was evidently too much for Mr. Lloyd, and

he laid it on Claude's shoulders. He was suffering under a

deep-seated and long-standing paralysis of the will, and it was

painful to him to exercise the diseased function.

It was a great relief to him to be told that Aunt Monica had

already undertaken to help in the matter, and that there was no need

for him to trouble himself in the least. When they passed on

to higher topics, Claude was astonished to find that he was talking

to a man of larger mind and wider culture than he could have

believed possible, co-existing with such curious defects of

character.

"And he has," added Aunt Monica, "a large measure of the

almost forgotten grace of a true humility."

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXVII.

CURATE AND CARPENTER.

AND so Claude is

settled down in the village, after having been with us for a week.

It was on a Saturday he was expected, and he would not let us send

the carriage to meet him. He said he preferred walking and

having his luggage fetched, as there was a box of books too heavy

for the carriage. His coming in this way was the cause of an

encounter which has made a great impression on his mind.

The afternoon sun was hot, and the road white and dusty, but

on either side the corn and pasture-fields runs a broad belt of

grass, sprinkled plentifully with the shade of spreading trees, and

soft and pleasant to the eye and foot of the wayfarer. On one

side walked Claude, carrying a black bag in his hand, and before

long he was aware of another young man walking on the opposite side,

also with a black bag. They passed and repassed each other as

they walked apart, till an amused smile grew upon Claude's face.

I know exactly how he would look. Claude's is not a

handsome face, but it is one which irresistibly attracts you; a face

alive in every feature with the mind it indexes. His head

looks bigger even than it is, with its immense masses of wavy light

brown hair. His grey eyes are large and soft, but they are

deep set in his head, and shaded with thick eyebrows. His nose

is nondescript, and the mouth and chin too prominent for beauty; but

it is these irregular features which give its power of expression to

the face. The quiver of the wide nostrils, the tremulous

movement of the lips, are full of a sympathy swifter and keener than

is well for their owner's peace of mind or repose of body.

Young as he is, there is already a worn look about Claude,

heightened by his extreme slightness of figure, a slightness which

borders on emaciation; and yet the expression is not of suffering.

He says he has never had a bodily ailment in his life that he can

remember. It is rather of joy as of one who drinks deep of the

keener delights of the Spirit.

I can fancy what a contrast he presented to his wayside

companion; for Claude has pointed him out to us already. He

hopes to make a friend of him; but his recognition of Claude's

friendly bow was a rather surly one. He is not older than

Claude in years, this young man, but he looks older in experience of

life, somehow. More manly, some would undoubtedly call him—an

altogether finer animal. He belongs to a different class of

society. You can see that at a glance, though his clothes are

better than Claude's, and more carefully put on. He is

handsomer, too, after a type seldom seen except in the workman and

the noble, the ease of the intermediate classes evidently not

tending to produce it. His features are fine as a piece of

sculpture, and lofty and disdainful in expression. His

complexion clear, but a little too fair and florid, and his hair of

a rich golden brown, curled closely round his neck, which is burnt

brick-red with exposure to the sun.

These two had been ascending a gentle slope, and when they

reached the crown of it a little dilemma occurred. The grassy

belt on one side of the road became narrower and narrower, and at

length entirely disappeared, leaving one of the pair on the bare and

dusty highway. It happened to be the smiling pedestrian who

was thus cut off, and who thereupon smiled more decidedly, crossed

over to the other side, and greeted his fellow-traveller with a

friendly nod.

"We seem to be both going the same way," he remarked; an

original observation which was echoed by one equally so on the state

of the weather. Then they congratulated each other on the

harvest, with the gravity of men who had a stake in the agricultural

prospects of the country, and then they marched on in silence.

The road swept down only to ascend again, and this time on

the crest of the undulation they came in sight of a village.

"That is Highwood, I suppose," said Claude, pointing forward.

"Highwood-on-the-Green," replied the other. "Highwood

is on this side, about a mile off."

"Oh, I did not know there were two Highwoods," rejoined

Claude. "Are there churches in both?"

"Churches!" was the answer, or no answer; "there are plenty

of them, for all the good they do."

"You are chapel, I suppose," said Claude, and I think I see

the gleam of humour in his eyes as he said so.

"Neither one nor other," said his companion, with energy.

"I count them all alike, deluding the people with old wives' tales,

and making a very good thing of it for themselves."

"That is not true," was the retort, flung back, I have no

doubt, with dilated nostrils and head in the air, as if the speaker

enjoyed the prospect of combat; "making allowances for men's faults

and failings, and for their failings more than their faults, the

clergy are sincere and disinterested. I am a clergyman, and I

am not going to make a good thing of it. I should have made a

much better thing of it, in your sense, by taking myself elsewhere

than the Church. The world is by far the best paymaster, I

fancy."

"It won't pay much longer for humbug, at any rate," said the

other.

"Humbug!" repeated Claude. "You cannot think that we

clergymen stand up in the pulpit and deliberately declare what we

know to be false! You must give us credit for believing what

we teach and preach, and any sincere belief is at least worthy of a

hearing—is at least not of the nature of imposture."

"You would not grant a hearing to mine," was the reply.

"I certainly should," was the rejoinder, and the two stood

still, regarding each other keenly, but certainly with strangely

different feelings, while the young man poured forth his hatred and

contempt of Christianity in a strain of perfect passion.

"But it was for Christianity as he had known it in some

obscure and narrow sect," said Claude to Aunt Monica, "and I was

glad to notice that he passed over the name of Christ in a silence

that savoured of reverence, and spoke in glowing terms of the Bible

as the Book of Books."

Then, as they walked on, the young man began the old

controversy concerning the contradictions between science and

theology about the record of Creation—that inspired poem, Aunt

Monica calls it, not capable of contradiction by any revelation of

science.

And, so talking, they entered the village of Highwood, which

at that hour was so quiet as almost to seem deserted. The

green was left entirely to the geese, who paddled over it, cropping

the grass or sipping at the margin of the pool. Even when you

know better, the afternoon quiet of an English village always

appears the image of a perpetual Sabbath.

Something of this feeling passed through Claude's mind, as he

exclaimed—

"Here is the place, but where are the people?"

"Here is one of them, at all events," said his companion,

spurning with his foot a prostrate figure.

They were crossing one of the green corners already

mentioned, and the man was lying on the grass, face downwards.

Claude stopped involuntarily. The attitude of the man and his

breathing were not those of ordinary sleep. He stopped, and,

stooping down, managed to turn him over on his side.

"Leave him alone," said the other, contemptuously.

"He'll sleep it off."

"I suppose he is drunk," returned Claude, as he looked down

on the degraded form and bestial face of the man.

"I should think so," was the reply, and the speaker moved on

in advance.

"You know this place well, do you not?" asked Claude, again

reaching his side.

"I was born and brought up in it, and my father before me,"

he answered.

"Is there much drunkenness in the place?" asked Claude.

"Where is there not? It is the curse of this country,"

replied the other, "and it's my opinion will be her ruin." He

had got upon a theme upon which he could talk, it seemed, for he

poured forth a diatribe on the working-classes to which Claude

listened in astonishment and sorrow. Venturing to speak of

their needs and their aspirations, he was met with a storm of words

on their drunkenness, their idleness, their selfishness, their

dishonesty. "Do you think I would abuse the class from which I

sprang if I did not know that they are ruining themselves and their

country?" he cried. "I ought to know. I employ hundreds

of them, and am in daily contact with them till I am nearly driven

mad with their disgusting folly—when I know that if they would but

be temperate, and self-denying, and honourable, they might hold

their own in equality with any class."

By this time they were in the village street, and Claude was

walking behind his companion. "It was his way of asserting

social equality," said Claude, "the pavement being too narrow for

both of us." At the end of the street they parted, but not

till Claude had sent a shaft into the armour of his antagonist—for

antagonist he seemed determined to be—by saying—

"At any rate, the men you speak of don't belong to the Church

of Christ. I hope we shall meet again, and that you will hear

me try and prove to you that the religion you abjure might do

something towards raising them to the condition of temperance,

self-denial, and honour you think they might gain."

And saying this he bade him good-bye, with a profound

interest easily to be accounted for by the nature of their

interview.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXVIII.

PHILLIS AND PRISCILLA.

ON one side of

Highwood Green runs the line of cottages called "The Street," and on

the other the houses named for distinction "The Row," and, standing

impartially between them where they draw together, is the church.

The village churchyard lies round the sanctuary, and behind it is

the rectory, in the midst of its lawns and gardens.

Very lovely and peaceful it all looked on Sabbath morning, as

Claude saw it from the crown of the unwooded slope which he had

stretched across the stubble to gain, and from whence he descended

as the bell sent its first clang upon the air, and he could hear it

echoed from other hamlets hidden away among the woods. Fresh

from the morning fields Claude came to the service of the church,

and his hearers had seldom heard that service more impressively

given than as he gave it, with a fervent simplicity which brought

out its meaning as no fineness of intonation, no mere grace of

elocution could do.

After service, with an interval for lunch, came the

Sunday-school. Claude was expected to take the leading part

there, assisted by the schoolmistress and a small staff of teachers,

of whom Aunt Monica was one. She had taught in the school

since her girlhood, and had resumed her work there gladly and at

once. And Lizzie and I had accompanied her, really more as

scholars than as teachers, though Lizzie already helped with the

little ones, while I remained by Aunt Monica's chair.

The school, whither we conducted Claude, was a plain building

with a cottage at the end for the schoolmistress. We passed

into the wooden porch, garlanded with roses and honeysuckle, and

opened the door; a rush of subdued voices coming out upon the air as

we advanced into the room. Then the murmur gave place to

silent staring. The schoolmistress, a slight girl, dressed in

black, and not very remarkable, except for a look of patient

endurance, came down the floor to meet us. Claude introduced

himself, and we went to our places and our tasks, for we were a

little late, and the discipline was unusually strict.

The school was indeed very well conducted, though the

assistants were few. They consisted of an elderly gentleman,

whom Claude had noticed in one of the front pews at morning service,

and of two young girls whom he had not noticed, because they had

been seated with the children in the little gallery. They

might have been of any rank, for they were well and simply dressed,

and both more than merely pretty. The one was teaching the

small boys, the other the little girls. The schoolmistress and

Mr. Martin offered Claude their classes, but for the day he

preferred to remain unattached, so he took the little ones in turn,

and made acquaintance with them and with their teachers, Phillis

Bower and Priscilla Jewel.

Phillis and Priscilla were as nearly as possible of the same

age. Both had passed their nineteenth birthday, and both from

different causes looked older than their years. Phillis was

tall and stately, slender without slightness, a large,

softly-moving, beautiful creature. Her eyes were not black,

but of an indescribable lustrous darkness. Her skin seemed a

transparency through which one saw such delicately-blended tints of

rose and pearly-white, as nothing on earth ever equals, not even the

inside of a shell. But what every one noticed even more than

the girl's beauty was the peculiar quality of her voice. It

seemed to caress the words it uttered, so that you longed to hear

some simple word repeated, to fix in your mind the memory of a tone

so sweet. Claude was very much interested in the two young

teachers, and after the children had been dismissed, he made

inquiries concerning them, which the schoolmistress and Aunt Monica

were able to satisfy—the latter having known them all their lives.

Priscilla was the daughter of the village smith, a widower,

with no child save her. She had left school at thirteen,

having persuaded her father to let her keep house for him, the old

woman who had kept it ever since her mother died having fallen ill,

and gone to live with a married daughter at a distance. She

had made a nice little housekeeper, the schoolmistress said, though

left entirely independent of control; and she was doing her best to

restrain her father from the sottish intemperance which had crept

upon him.

Phillis' parents had been rather higher in the social scale.

Her father had been a considerable freeholder on the border of the

forest, and a grazier and cattle-dealer besides. He still

dealt in horses and hounds, and let one or two fields for grazing;

but the bulk of his property had been sold piecemeal, and they were

in reduced circumstances—owning, indeed, little more than the house

they lived in. Phillis and Priscilla had been all their lives

devoted to each other, so that whatever the one did the other wanted

to do. Phillis had therefore left school when Priscilla did.

It was not the village school, but a small proprietary

"establishment," kept by a widow lady in the Row, whose pupils had

never numbered more than half a dozen, and had sometimes consisted

of Phillis and Priscilla alone.

Phillis's love of children had prompted her to seek the

Sunday-school, and Priscilla had followed as a matter of course.

The Bowers had let part of their house lately, but Phillis

was not so much occupied at home as not to be able to spare an hour

every now and then to help in the school; indeed, to help anywhere,

if help was wanted. Phillis was a universal favourite.

"And they let part of their house," said Claude, suddenly

recollecting and thinking at the same time, as he told us, that the

home out of which this sweet and modest girl came could not be a

very bad one.

"John Bower is a very bad man," remarked the schoolmistress,

as if in answer to his thought.

"So I understand," returned Claude.

"He does not drink," she continued; "at least, that is not

his worst fault. Priscilla's father drinks a great deal more

than he does, but he has a terrible temper, and he is an infidel.

He has been the ruin of his family. He has driven them all

from his house, till only Phillis is left. You would be sorry

for his wife, if you knew her, and for that matter for Phillis,

too," she concluded.

Claude informed her that he was, in all probability, about to

take up his abode in this lion's den, at which she smiled grimly,

but told him that John Bower would not interfere with him if he was

not interfered with.

"But I can't promise not to interfere with him," said Claude.

And, indeed, he confided to Aunt Monica that he thought his

interference might be valuable at a crisis in the Bower family if he

became an inmate.

Soon after, passing up the street, we saw the two girls,

Phillis and Priscilla, walking arm-in-arm, and bowed to them as we

passed. And Aunt Monica supplemented the schoolmistress's

narrative by giving Claude a particular account of the families of

both.

The last two houses in the village were those of the Bowers

and the Jewels. John Bower's was a good eight-roomed house of

modern date, but with front and back gardens old enough to be

pretty. John Bower himself was the biggest and most powerful

man in the parish, or in all the parishes round. He and his

wife had been the handsomest couple in the district. She was a

meek and quiet woman now, but she had been gay and high-spirited

enough in her time. She was a farmer's daughter, and had

brought her husband a few hundred pounds, which he had spent in a

single year, gambling and running over the country coursing.

He did not drink then—at least, not to excess—but he was subject to

storms of passion, and remonstrance on his course of conduct never

failed to rouse them. So it was whispered in the village that

in John Bower's house murder would be done. Indeed, the pair

led a life so unhappy at first that it was like to have come to an

end one way or other. Mrs. Bower, on one occasion, was about

to return to her father's house; but her husband vowed that if she

did he would do her some mischief, and she evidently believed the

threat, for she remained, though in mortal terror. Her life

would have been unbearable but for her children. Curiously

enough, when she began to have children, some strong animal instinct

made her sacred to him. While she had an infant in her arms

she was not only safe from violence, but secure of a certain rough

tenderness. But as soon as the children got beyond infancy,

and had strength enough to oppose his will or elude it, her torture

began again. And then it was through them that she suffered.

Many and many a time had she lied, with fear and trembling, to hide

their childish faults from a violence that hardly stopped short of

bloodshed. Her eldest son was but a boy of fifteen when he and

his brother, a year younger, rose up one moonlight night, and fled

away from home. Every effort was made to find them, but proved

unavailing, and with a strange conflict of feeling their heartbroken

mother rejoiced that they were not to be found.

Mrs. Bower had had thirteen children. Two daughters,

before they were seventeen, made run away matches, and had never

crossed their father's threshold since. Then followed a troop

of little ones who died, some in the hour of birth, some in tender

infancy—owing, perhaps, to the mother's vital energy being lowered

through fear and anguish—and last of all had come Phillis, whom her

father had hitherto treated with extreme indulgence, though there

were times when his savage nature was as savage as ever, when he

would wreak his fury on everything within his reach, knocking the

furniture about, and breaking the crockery into fragments. But

Phillis is always safe from his fury. He wants the girl to

love him, and she has a soft caressing way with her which satisfies

him. But love him she does not. She has an abject fear

of him, and nothing drives him mad so readily as to see her shrink.

It was, however, agreed that evening that no time should be

lost in finding out if Claude could lodge with the Bowers for the

present.

On Monday morning, therefore, we started for the village,

bent on negotiating for "the rooms," which a ticket set up against

the flower-pots in the ground-floor window, announced as "to let."

A little maid, not too tidy at that hour of the day, opened

the door for us, and ushered us abruptly into the parlour. It

was a small square room, full of faded furniture, but filled with a

soft green gloom from the half-drawn Venetians and the ancient

geraniums which stood in the window, with their leaves all turned

one way seeking the light, and in it sat Phillis Bower.

She was not doing anything, and yet she did not appear idle.

She had already done her share of the household work and part of the

little maid's, and was free to spend the rest of the morning as she

chose. There was a cottage piano in the room, but it was

closed.

Claude need not have cast a glance of apprehension at the

instrument, for Phillis never opened it, indeed did not like its

music at all; neither did she like the smaller sorts of needlework.

I think she might have wrought a piece of tapestry, but she

preferred making a child's frock to wool mats and bead baskets and

the other things in vogue in the village.

"At the girl's feet lay a great white hound."

Everything in the room was worn and faded, everything save

Phillis and the flowers. The carpet, which had probably had an

objectionable pattern, was now almost plain grey, with here and

there a hint of departed floweriness. But the fire-place was

filled with a mass of green bracken, and beside it Phillis rose clad

in silvery grey. Her dress was of some light woollen stuff,

streaked with green in the shape of trimmings, a dress like a

flower-sheath, and out of it grew the lily throat and flower-like

face. At the girl's feet lay a great white hound, her slender

head resting on her long fore-paws, and her eyes fixed on her

mistress's face. As she rose in answer to our greeting, the

dog rose with her, and followed her from the room, which she left

saying, simply—

"I will send my mother."

Our negotiations with Mrs. Bower were speedily concluded,

with the result of engaging the vacant parlour and bedroom on the

floor above. Indeed, we had very little choice in the matter,

for no other lodgings were within reach. Claude liked the

appearance of the rooms, for, though neither lofty nor luxurious,

they were neat and clean, and he liked Mrs. Bower herself very much

indeed. At the end of the week, therefore, his

luggage—consisting of a carpet-bag, a leather portmanteau, and a box

of books—was conveyed to John Bower's, and Claude found himself at

liberty to begin his ministry at Highwood.

Claude comes into contact pretty often with the young

carpenter—or builder, rather—whom he met coming into Highwood.

His name is Thomas Myatt. He is considered quite a great man

here, young as he is, for he is on the high road to fortune.

He is very intimate, it seems, with the Bower family, but he is

evidently averse to have anything to do with Claude.

The latter, who is extremely fond of walking, has several

times encountered Myatt in his excursions in the neighbourhood.

Once they dined together at one of the old inns to be found in the

forest. Claude says it is a delightful old place, with the

forest—the real unenclosed forest—coming up to its very doors.

He peeped into the yard, with its hens and chickens and dove-cotes,

and into the orchard, where a row of time-stained worm-eaten benches

ran under the old apple-trees. An elderly landlady came out to

the threshold to welcome her guests, and as Claude came up to her,

he recognised Myatt. The landlady evidently knew them both,

for she greeted Mr. Myatt by name, at the same time dropping a

curtsey to Claude, and treating him with a cordiality finely

tempered by respect. Mr. Myatt had to wait till Claude had

ordered his dinner, and the former turned it off with a careless—

"Get me something at the same time."

"Very well," replied the landlady, with a good deal less of

deference in her tone, which Claude could see the other was not slow

to notice and resent, and which did not, in all probability,

increase his kindly feeling towards him.

Still, the two strolled off together, the landlady coming out

to warn Claude not to go too far into the forest—a warning which was

not so superfluous as it seemed. Not many hundred paces off,

they plunged into a maze of Nature's making, and Claude found

himself treading on turf as soft as velvet, in and out among

heaped-up masses of thorn and bramble, which seemed to choke the

stunted trees, and which speedily deprived him of all knowledge of

his point of departure.

"This is the first time I have ever been in a forest," he

said, "and there is a kind of enchantment in it."

But Claude could get nothing from Myatt but monosyllabic

answers, though he kept quite aloof from any allusion to their

former meeting.

After wandering about for some time they heard a bell ringing

vigorously at no great distance, and Myatt, followed by Claude,

hastened in its direction. The stable-boy had come to the edge

of the forest to ring it as a summons to their respective meals,

which they found laid at respective ends of the table, with a whole

desert of distance between them. When they had taken their

places, Myatt at once uncovered and began to eat, while Claude bent

his head over the meal with a murmured thanksgiving, and the

contempt of his companion apparently culminated, for he resisted all

Claude's attempts to draw him into conversation.

On another occasion nearer home the forest tempted him into

its moonlight recesses, and he wandered there admiring the weird and

lovely effects of the moonlight till he came upon a little

aisle-like glade which it pleased him to pace up and down in

meditation.

At length he began to think of returning to home, as the hour

must be getting late. But how, became the question, for short

as must be the distance, be had lost his way and must take one of

the many paths about him with the merest chance of its being the

right one. He smiled, for the dilemma did not appear a very

serious one, but at the same time he ceased his meditations and

roused all his active energies. Once more he stood still,

trying to make out his bearings. How quiet it was; there was

no wind, but every now and then the faintest sighing swept round and

over him. His footsteps were almost noiseless on the grass,

still he thought he heard some sound and listened again. He

was right, some one was close at hand. "Who is there?" he

cried, and a man's figure started out into the open space between

him and the moon. With some amusement Claude recognised him,

and doubtless at the same time revealed his own identity, for Myatt

gave vent to an expression of impatience. Claude hastened to

apologise.

"I came out for a stroll before going to bed," he said, "and

have fairly lost my way."

"You're not far off it," said Myatt. "Keep straight by

the thicket there," and he pointed before him, and then turned and

strode away without another word.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXIX.

AN OLD STORY.

ANOTHER Christmas

is at hand. It will be here in a fortnight, and we are already

looking forward to it. Ernest is coming, of course; but he has

asked Aunt Monica if he may bring Mr. Temple with him, and she has

written to say she will be happy to receive him. We are going

to have several guests. Mrs. Carrol and Clara are coming, and

we must have Claude to be with them. Why can I not be happy?

I have found out that change of circumstances, however much for the

better, does not make one happy. It is only when one has all

the love and all the work one wants that it is possible to be so.

I don't think the love would make one quite happy without the duty,

which is only love in action; and, then, all love of a natural and

noble sort brings duty with it—and I am quite sure the duty would

not without the love. Aunt Monica is my ideal of happiness;

her spirit is the very spirit of love and duty. And now her

outward life is in perfect harmony. Her days are one round of

love and duty. She knows all the people here, and goes among

them, always ready to do the right thing, and speak the right word.

Then she has her hours of devotion—that word with two meanings, one

of service and one of love, or worship, and the two meanings

interchangeable. I know that she is happy, and I know, too,

from whence her happiness comes. In her own words, "The only

true and abiding joy of life is the sense of a divine sympathy, a

divine companionship. When this is attained, all life flows

into a new order, a new activity, a new repose."

Lizzie, too, is happy. She is full of service.

Claude finds plenty of work for her to do—reading to the old people,

and helping in the school and in the choir. I also help in the

latter; and the singing in the church, we are told, has already much

improved.

The greatest drawback to our Christmas programme will be the

absence of Edwin. What a strange thing is character!

What a strain of unbending will there is in all our family, except,

perhaps, in me. I fancy I have it somewhere, like the beam in

a pair of scales, but it is always being weighted down on one side

or the other. Here is our father, who has himself tasted all

the bitterness of alienation from his family, and yet he will not

take the slightest step to bring Edwin back to his allegiance.

Doretta behaved very ill to papa, but I am sure he would have

forgiven it—forgiven is not quite the word, I am learning to attach

a deeper meaning to that—but overlooked it, for Edwin's sake.

If he had only come to him as of right, and allowed his wife to take

her own way about it, he would have been gladly received.

There is a coarse insolence about Doretta, and in her narrowness she

is incapable of respecting the rights of others, or even of

estimating the results of her conduct to herself; so she held him

back from us, drew and kept him away from us with all her might.

It is impossible to press our father to make advances to him, and

Edwin himself makes none, for what passed between them last week

makes it almost more hopeless than before.

Lizzie and I went up to see Doretta and the children.

We have been several times without seeing him, though we wrote to

say we were coming, and stayed as long as we could in the hope of

doing so. She received us pettishly as usual. The

children looked ill-cared-for, and were fretful, and the house and

its mistress slatternly in the extreme.

Doretta boldly complained that they could not make ends meet.

For the first time we learnt that there was a bill of sale over the

furniture, that furniture of which she had made such a mystery.

It had simply been ordered without being paid for, and the furniture

dealer had taken this method of obtaining interest for his money.

Edwin was not well, she said. He often—indeed, nearly always

now—went without dinner, got a cup of coffee and a bun in the middle

of the day, and came home to supper. Our hearts ached at the

picture she drew of his life; perhaps it was meant to harrow our

feelings, but for the most part it was unconscious.

Lizzie and I could bear it no longer. It was I who went

to papa and told him that Edwin was in debt, and suffering actual

privation.

"He has not asked me for anything," was our father's answer.

"And if you wait till he does?" I asked.

"Yes, I understand," he said, "I may wait for ever. It

would have been my own case. But with me he has only to ask in

order to have; I would have asked in vain. However, I should

not like him to be in want. Let him know from me that he shall

have a cheque for £50 quarterly."

I was overcome with joy. Papa did not do things in a

half-hearted way. I thanked him fervently, and on my own

behalf and Lizzie's as well. Edwin will not be with us at

Christmas, but we shall know that he is in a position of comparative

ease and comfort.

That very day my father put an envelope into my hands

containing the first instalment of his bounty. At first Lizzie

and I thought we should like to send it to Edwin on Christmas Day,

but we felt that it would be cruel to postpone relieving him from

anxiety and care. So we rushed into town again, but this time

we sought Edwin himself in his dingy quarters.

After much climbing of broad shallow steps, and much

staring-at from clerks and porters, we were shown into his office.

It was an old-fashioned house, and close and dirty, as if nobody

ever thought of air, or light, or cleanliness, in connection with

business. Edwin rose as we entered, and greeted us with his

old sweet smile; but he turned deadly pale, and staggered to his

stool again. We quite forgot that one side of the mere box of

a chamber was glass, and that any number of eyes might be onlooking

as, one on one side, and one on the other, Lizzie and I held him,

and kissed his dear sunny head.

He was first to recover and smile again, for we were, to tell

the truth, crying over him. He shook himself free, and pointed

to the glass wall with a look of comic consternation, which brought

us to our senses.

"We have brought you a bit of good news," said Lizzie,

eagerly.

"Let's hear it," he said. "Heaven knows I have need of

it. I'm almost tired of my life."

I put the envelope into his hands, telling him that our

father had decided upon allowing him two hundred pounds a year, and

that we had brought him the first quarter. For a moment he

looked bewildered, incredulous, and then he laid his head upon his

desk, and broke down completely, crying like a child.

"You don't know what it has been," he said, when he had

succeeded in calming himself a little, "and I can't think what it

was coming to—people dunning and threatening us, waiting for me

here, waiting for me at home, and Doretta grumbling that we should

soon have had neither food nor clothes, and the children keeping me

awake all night, till I could hardly get through my work.

Never mind; it is all over now. It is good of him—dear old

dad! You know I couldn't have asked it; but I will write and

thank him. Wait here a minute," he added, "and I'll go and ask

for a half-holiday, and see you into the train, and then get home

with the tidings."

He got the half-holiday, and came with us to the station,

talking all the way with a kind of excitement which was quite new to

us in him. He did not ask us to go home with him; he was

probably aware that we might not be welcome. So we got back to

Highwood, glad and yet sorry—glad that we had been able to see him

relieved from his painful position, and yet sorry that his life

contained so few of the elements of happiness—he who was always the

brightest of us all, for whom any one would most certainly have

predicted the happiest lot.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Mr. Temple has declined the invitation, at which Ernest is

somewhat offended. I did not think it could have wounded me,

but it has. I have been dreaming again, vain and foolish

dreams, turning my life into a fool's paradise; but they are gone

for the present, and in a day or two we shall be in the midst of

what are called the festivities of the season. Half a dozen

dinner-parties abroad and one or two at home are among them.

The Winfields have returned to the Court, and we shall have

to meet them; indeed, we dine there the day after Christmas.

Ernest has declined, but it will be quite impossible to prevent him

from meeting Edith. Linnet Lloyd was expected home, but she is

not coming now until after the new year. We have not seen her

yet, and are full of desire to see her, for her own and her father's

sake. She has been abroad with one of her mother's sisters,

somewhere in the south of France.

Another interesting neighbour has presented himself, one

concerning whom our interest is of a more than ordinary kind.

One day last week papa came into the drawing-room saying, "Whom do

you think I met to-day, Monica?"

"I don't know, I'm sure," she answered unconcernedly.

"I met Benholme, and asked him to dinner. He has just

returned after a long absence. Poor fellow, he has met with a

sad accident this autumn."

My father had gone on speaking without waiting for answers,

while he glanced through some papers on the writing-table which

stood in one of the windows. Aunt Monica did not reply

immediately, but she looked troubled and distressed.

"What has happened to him?" she asked, in a low tone, while a

red spot began to burn on her delicate cheek.

"His sight has been nearly destroyed by an accident on the

moors, and what is left appears to be gradually quitting him."

"I am very sorry," said Aunt Monica, simply, but with much

agitation of voice and manner.

"It reminds me of old times, Mona, to meet him here. He

was your chum, though. Do you remember he used to cry for you

till they were obliged to send the carriage over to fetch you to

play with him? and we used to look out of the window in the rain,

and see you driven off in solitary state, when you were so small you

had to be lifted on to the seat."

"We shall see him this evening, then," said Aunt Monica,

quietly, and immediately left the room,

She quitted us so swiftly and softly that my father did not

notice her going, and continued, "By the way, he took after me.

I think that was the cause of the rupture between him and our

family, was it not?"

When he looked up, and found that she was gone, he said, "You

will like Mr. Benholme, Una," and then relapsed into silence.

I had heard of him and of his collection of pictures, always

to be seen in his absence, which had been latterly prolonged for

nearly three years, but I was not aware that Aunt Monica had known

him. She had never mentioned his name, or offered to take any

of us to his place, though it was in the near neighbourhood, and was

famous for its woodland views, as well as for the treasures within

its walls.

Accordingly, in the evening Mr. Benholme came. He had a

great green shade over his eyes, to preserve, I suppose, what little

of sight remained to him, and which, from the wavering way in which

he sought our outstretched hands, could not have been a great deal.

There was not much of his face to be seen, but his smile was

singularly sweet, and his voice had a special charm. We had

Claude to meet him, and he was particularly delighted with him.

Lizzie, too, fancies that he is something like what her favourite

Mr. Ruskin must be. He invited us all to the Park, to see his

pictures, and asked Claude to inspect his library, and make any use

of it he can.

He was extremely deferential to Aunt Monica all the evening,

while she was her own sweet and serene self; but there was nothing

to tell of the tender intimacy that had been between them, as I came

to know. It was Miss Amphlett who told me. Mr. Benholme

had called on the old ladies, as he always did, and they were full

of his praises when next I saw them.

"He knows we can't afford to buy pictures," said Miss Nancy,

"and so he has brought us these." And she drew my attention,

already indeed caught by them, to a pair of small landscapes which

adorned the wall. "He wanted to encourage a young artist, he

said, and give us the benefit of his taste."

"Ah, my dear," said Miss Bell; "your Aunt Monica ought to

have been mistress of the Park, and its master would have had

something else to do than run after artists and foreigners. It

has never been a home for him since she gave him up. He is

here to-day and away to-morrow; and I don't know what will become of

him if he loses his sight."

I could not ask questions, but I looked the interest and

sympathy I felt, for Miss Nancy went on—

"You may look sorry, child. It's long ago; but it made

our hearts ache that these two, who had been bound up in each other

from the time they were babies, should have been parted. She

gave him up because her father wished it, and her mother could not

bear any more strife in the family. It was killing her, I

believe."

"Monica could not have done anything else," said Miss Bell.

"He never would believe that she had really cared for him,

though," said Miss Nancy. "By that time he had neither father

nor mother himself, and be could not feel the strength of the pull

upon her which put them asunder. He always thought she had

left off caring for him, and she never gave any of us the power to

interfere. And then he went abroad for years, and only comes

now and then to look after his pictures. They are not much

company for a man. Not but that they are very nice—at least a

few of them—but they're not like real men and women and real trees

and grass," concluded Miss Bell, echoed by a shake of the head from

Miss Nancy, as they looked at their pictures; by which it was easy

to see that the two old ladies were but lukewarm in their devotion

to the art of painting.

And so at last I know the story of Aunt Monica's

youth—tender, and dutiful, and pure.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXX.

LINNET LLOYD.

SO much has

happened since Christmas Day that I hardly know where to begin the

record of events. Ernest came down, having evidently made up his

mind to treat Edith Winfield with complete indifference. He did not

try to avoid her in the least. He was neither cold nor haughty, but

assumed the manner of a mere acquaintance, from whom she might

expect the ordinary courtesies of society, and nothing more. It was

not a safe position to assume, seeing that it was so unreal; and I

feared its passing into a covert hostility, productive of greater

misery between wits like theirs, which could wound at will, and

tempers which might easily be brought to have the will to wound. But

my fears were groundless. That which has really happened is

something which I did not fear at all, which it never entered into

my mind to imagine. That Ernest should renew his relations with

Edith was not in all my thoughts. And yet this is what has come to

pass. He has renewed his relations with her, and they are evidently

far graver and tenderer than before. For this time it is not his

affections alone that are involved. The love is not on his side

only. When the situation dawned upon me, I felt utterly at a loss

how to take it. I was alarmed, and less this time on his account

than on hers. I was half-inclined to doubt his sincerity in the

matter; and I feel sure that Edith has in her nature an unlimited

capacity for suffering. It was wonderful to see her so transformed

by happiness, so elevated into a sweet and gentle gravity.

Neither of them has spoken to me as yet, but during the last week of

Ernest's stay their preference for each other's society was not in

the least concealed, neither is Ernest reticent as to the fact of

his correspondence with her.

Closely following this came Claude's illness. He has been seriously

ill.

Mrs. Carrol and Clara failed to come to us, as had been arranged,

because the former was suffering from a rather severe attack of

bronchitis. Then, immediately after, Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd went to pay

a visit to the sisters of the latter, with whom Linnet was

residing—Linnet, whom I can hardly now think of as a stranger, so

much is she at home with us already.

Claude was, of course, left with his hands very full, both of Sunday

services and week-day visiting, as there happened to be a good deal

of sickness in the parish.

Our old couple at the lodge have a son, a gardener, whose children

unfortunately had taken the measles, and Claude considered it his

duty to ask after them almost daily. They had taken ill early in the

week, and at first he could see very plainly that he was not

wanted. He was not admitted to see them, though they were his