|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XIV.

A HARD LIFE.

received Philip with her usual gracious calm, but he was not to be

soothed by it; and it was not long before she noticed his

irritability, restlessness, and gloom. They set to work as

usual, but Philip's gloom and restlessness increased, and affected

Mrs. Austin, in spite of herself. Their joint labours were

drawing to a close. The box whose contents they were engaged

upon was the last save one. At the bottom of it Philip came

upon a legal-looking document tied with red tape, and looking at the

endorsement found it to be the draft of a marriage settlement,

sketched out by Mr. Austin on behalf of his wife. "This you

had better keep with your other papers," he said, handing it over to

his companion.

She looked at it. "I do not suppose it is of any use,"

she replied, after glancing over it. This was afterwards

altered; her voice was agitated. "Will you tear it up?" she

added.

He proceeded to do so, when a letter fell out of the folds of

the paper and fluttered to the floor.

Mrs. Austin caught it. "A letter of my father's," she

said, looking at it. "Poor father!" she murmured, with a look

of profound pity.

"Was he unfortunate?" said Philip, "for if so we have this

too in common."

"Very," she answered. "He became bankrupt; not a

splendid bankrupt, like those who led him into speculation, whose

wives had handsome settlements, and never dropped their carriages,

or put a stop to their engagements, because their husbands could not

pay a tithe of what they owed. He was a broken man, and died a

clerk in the office of a tradesman."

"Which was a great deal more honourable, Mrs. Austin," said

Philip, "than if he had done as those you mention, and secured

himself at the expense of his creditors. The easy release from

debt which dishonest men may obtain is a public scandal. It is

lowering the whole tone of public morality. Peers take the

lead in insolvency nowadays. Every peer who enters the

Bankruptcy Court should come out of it stripped of his titles and

honours at the least. It is the honest man who loses

everything, and to him bankruptcy can hardly be embittered."

"It was very bitter to us, Mr. Tenterden. We were an

exceedingly attached family, and felt keenly for each other, and

especially for our father, who broke down completely. He had

not the kind of power which resists pressure."

"Did he die before your marriage?" asked Philip.

"No," she answered; "it bought him a year or two of repose."

Philip looked the question he did not ask.

"My marriage secured to my parents a hundred a year," she

said quickly. "My mother has it still."

"Oh, I see!" exclaimed Philip.

Mrs. Austin looked distressed. "There was no undue

pressure put upon me," she explained. "I did it quite

willingly—nay, gladly; but I did it in utter ignorance of all that

it involved. Oh, Mr. Tenterden! good men must despise a woman

who sells herself for so much money—that was what I did."

"The woman is despicable enough," said Philip, "who does it

to obtain for herself the things that money will buy—meats, drinks,

dresses, houses, fine company, servants, &c.; but that is not your

case, Mrs, Austin. No one has a, right to despise you, and it

would be impossible to any one who knows you. But perhaps

there was some one you cared for which made the sacrifice harder."

"No," she answered, sadly; "but when he brought me here, away

from home, I drooped and pined; I could not help it. I became

home-sick. He resented it. He was a man of harsh and

despotic temper, and he made little effort to win me. He

settled into sternness and gloomy reserve, aggravated latterly by

severe suffering."

"Yes, your life must have been a hard one," said Philip.

"It would have made me wicked," she said, "if I had not

learnt to love him after a fashion. And oh! how I missed

him—miss him still! He made the duty of my life; and a life

without a duty is drearier than a life without a pleasure."

"That I can imagine," he replied; "and that you at least

would shape your life to any duty, however hard; but with a man it

is different. A duty which binds him down, and leaves him no

room to shape his life for himself, becomes intolerable. My

father was not a bankrupt," he said, "but he died wholly insolvent,

leaving me a legacy of debt which it will take the best part of my

life to clear myself from. I am glad that you should know

this, though no one else does; it will explain some things which may

seem strange to you, I believe;" and he laughed a little bitterly.

"I have already acquired a character for miserliness, but that is a

small matter; it is hard, however, that the only happiness I could

have cared for, the happiness of making a home for the girl I loved,

should be beyond my reach; that I have nothing to offer any woman,

and may never have."

Ellen's heart beat fast, and a hot flush went up over her

face, as she tried to answer steadily, "She whom you love might

think it enough if you offered only yourself."

"You forget," he said bitterly, "I have not even myself to

offer."

There was a pause, during which Ellen suffered the choking

sensation like something drowning in the heart, which comes with the

sudden extinction of hope which has never seen the light. She

sat still, and made no sign till it was gone. Then she said

gently, pleading for that other, "She might wait till you were

free."

"She—she is gone from me already," he answered abruptly.

What hindered her then to comfort him? She had the

impulse—the impulse to lavish herself and all that was most precious

to her in the effort, but the words would not come. It was

impossible for her to break through the fence of her womanly

reserve. She sat before him dumb and restrained, and never had

he been so distant and so cold. Absorbed in his own feelings,

he had not thought of hers.

A loud knock at the outer door broke the silence. Mrs.

Austin started. "I wonder if that is my mother!" she

exclaimed; "I expected her home in a day or two, but she must have

returned earlier."

It was Fanny, who, with a shawl thrown over her head, and

followed by Ada in similar costume, had come in from next door to

speak to Philip.

CHAPTER XV.

PERPETUAL FRIENDSHIP.

ARTHUR

WILDISH had dashed up to

Hampton as fast as a hansome could carry him. Lucy was at

home, and alone. She had been lying on the hearthrug, a great

white fleecy one, reading, with Muff, a black, silky terrier,

keeping her company. Arthur and she were great friends, yet

she hoped she had jumped up in time to avoid discovery, and she

hastened to say, "Mamma is out," with a pretty little blush born of

a consciousness that Muff and she were a little dishevelled in

aspect, as she had been intending to run away and dress for dinner,

only her book was too entrancing to be left.

Arthur was rash enough not to have considered what he would

say. To have had something to say would have been useful, even

if he hadn't said it, closing a few of the many possible approaches

to a great subject.

"Have you seen my father?" asked Lucy, innocently.

"Yes, I left him in his room. He will be up at the

usual hour," said Arthur.

"And why are you so early?" she asked; "have you got nothing

to do?"

"I have come to see you," he answered gaily, and smiling at

her fondly; but the gaiety and the fondness being mixed up together,

left Lucy quite unconscious still.

"May I run away from you for a few minutes?" she said. "Muff

has a fancy for pulling out my pins," and she stooped and picked up

a pin with a silver star at the end of it, the neighbour of which

was fastened in the plaits of her brown hair.

"No, I can't spare you just now," said Arthur, the audacious,

"I have something particular to say to you."

She stood in front of him with clear questioning eyes and

laughing lips, and said, "What is it? have you got a brief? or are

you going to the bush to be a squatter?"

Nothing daunted, Arthur answered, "Neither the one nor the

other, Lucy. I love you—"

"Oh, why—" she exclaimed, moving backwards, not knowing in

the least what she said, and looking in her movement like a startled

fawn.

"Why!" he answered gaily; "was there ever such a question?

because I love you, and have a hundred other bemuses all summed up

in that; because you are what you are, so sweet and good; because

you are like music that I want to set my life to—must, for it will

go to no other; because I think we would be so happy that we must

make the whole old world a bit happier and better for us. Eh,

Lucy," sad his blue eyes kindled and suffused as he moved nearer and

held out both hands to her, saying, "Lucy, will you be my wife?"

She shrank away still further, crying, "Oh, Mr. Wildish, I

cannot—I cannot!"

"Don't you like me, Lucy?" he asked, sorely dismayed.

"Like you—oh yes, I like you a great deal," she answered;

"but that is different."

"But if you like me a great deal, you may love me in time,"

he said, with reviving hope. "I will wait, Lucy; I will make

you love me."

"Oh no—no!" she answered, as if she feared the very

possibility.

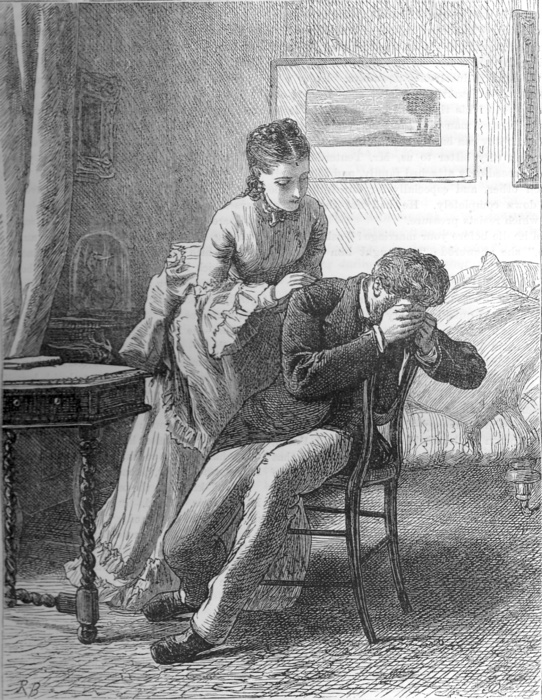

Her little work-table stood there, and she had slid behind

it. He sat down on the chair before it, and covered his face

with his hands. Was he crying? she thought so, and trembled in

the silence. He was suffering, she could see that, and she

could not bear to see suffering, far less to inflict it. She

drew near to him, and laid a timid hand on his arm. "I am so

sorry," she murmured, close at his ear.

(Drawn by ROBERT

BARNES)

"'I am so sorry,' she murmured."

He raised his head, and the tears came when she saw his face.

It was pale and fixed; she had never seen a face so changed, for she

had never seen sudden disappointment and heart-suffering, and Arthur

Wildish was suffering keenly according to his nature. Lucy

could not restrain her tears, nor stand by refusing to comfort him.

"It was enough to drive a fellow mad, though," he said to himself,

for she slipped a slender hand into his, and whispered, her face all

one vivid crimson, "If I had not loved some one else long ago, I am

sure I could have loved you."

Long ago! She had loved long ago, this bright,

child-like girl. What was the meaning of it? Her parents

could know nothing about it. Was she engaged? he asked.

"Oh no! please do not speak of it," she answered, in the

deepest agitation; "no one knows. I hardly knew myself till

now; he does not care for me."

"My poor darling!" and Arthur Wildish heaped passionate

kisses on the trembling hand he held.

"We may still be friends, may we not?" she asked, withdrawing

her hand gently, and with a deprecating look.

"Friends!" he replied; and was going to say, "I will never be

anything but your lover, Lucy," only that look of hers checked him,

and he vowed everlasting friendship instead. Both were acting

in perfect good faith, and a blessed unconsciousness of what the

wisdom of the world would rate their proceeding at, and they once

more clasped hands over their compact. Then Lucy fled; she had

heard her mother coming, and could not meet her for once in her

life.

Mrs. Tabor found Arthur alone in the drawing-room, and was

not a little puzzled at hearing that he had just parted from Lucy,

and was not going to stay the evening as usual. It seemed to

her that something must have happened, and she made a very shrewd

guess as to what that something was; but she could argue little from

the gentleman's appearance, which was certainly graver, but not much

more dejected than usual.

On his arrival at home, Mr. Tabor was still more astonished

to find Mr. Wildish gone, a fact from which, with his superior

knowledge, he could draw only one conclusion—namely, that Lucy had

rejected him. The young lady in question delayed her

appearance till dinner was on the table, and not a word could be

said. She had a suspiciously heightened colour, and a dilation

of the eyes which told of some excitement, but nothing more.

Late in the evening she got behind her papa's chair, and prefacing

her speech with a kiss on the top of his head, told him, what he

knew already, that Mr. Wildish had been there, and dashing into the

subject with trembling haste, said simply, "Papa, he wanted me to

marry him."

"And you wouldn't?" said her father, helping her out.

"No; but we are friends," she replied.

"Oh!" said her father, with some significance. Well, I

am glad you are not ready to leave me for the first jackanapes who

holds up a finger to you, though Wildish is an excellent young

follow."

Another kiss from Lucy, and she tripped away from her father

to encounter a far more trying tête-à-tête with her mother in

the drawing-room, out of which she came forth triumphantly, by

reason of her mother's pressing exclusively on the advantages of the

match, which Lucy, who really loved her home, and was not

discontented with her lot, was honestly incapable of feeling.

Meantime Arthur Wildish, rattling homeward, made up his mind

in the midst of his defeat to win in the end. But who could he

be—the insensate mortal who had gained such a hidden treasure as the

heart of Lucy Tabor, and neither knew nor cared? He cast about

in his mind who it could be. He conjured up all the young men

whom he had seen at the hospitable house of the Tabors, a house of

old-fashioned, solid hospitalities—not of flimsy modern ones, and he

could think of no one. Philip Tenterden crossed his mind, but

was rejected as too old and too grave. At length he remembered

Mr. Huntingdon. "Of course, it's the clergyman," he said to

himself, and he proceeded to depreciate clergymen in general, and

this clergyman in particular. But this tangible rival gave

birth to the pangs of jealousy. He did not know what to do

with himself. He dined at a restaurant, and then dropped into

the streets, a unit in the vast London crowds, ever hurrying to and

fro, driven by all sorts of strange necessities. Life assumed

a new aspect to the spirit of the enthusiastic, idealistic young

man—an aspect terrible and hopeless. He began to drink the cup

of youthful misery, and to perceive the attraction of recklessness

and despair.

CHAPTER XVI.

A BITTER NIGHT.

ONCE more Albert

Lovejoy failed to appear at home at the usual hour; and as time went

on and he did not come, a dumb anguish, which seemed to dry up her

tears, took possession of his poor little wife. About ten

o'clock, when the children had been asleep for hours, there came a

knock at the door, and she hastened down to see if it concerned her

husband.

Geraldine had already opened the door, and was answering some

one as well as she could for coughing. When she had shut the

door again Emily came forward. "I thought it might be about

Albert," she said; "I feel as if something must have happened to him

this time."

"So it is about Albert," replied Geraldine; "that man was

asking for him, and he has been walking up and down and looking up

at the windows for I don't know how long. He looks just like a

thief or housebreaker, Emily," she added.

"Nonsense, Jerry," said her sister-in-law; "we're too poor

for thieves to be looking after us. But what did he want with

Albert?"

"I don't know," replied Geraldine; "he only asked if he was

at home, and I told him no, but that we expected him every minute."

"Is he coming back then?" said Emily,

"I don't know. Let's see if he is there still" said

Geraldine. "We are all in the kitchen tonight, and I went into

the parlour in the dark, that was how I saw him."

They went into the room together, and stole to the window.

"Yes, there he is," said Geraldine, in an eager whisper.

A man passed close to the window, and looked up at the house

just as Geraldine had said. Emily leant against the shutter

and trembled like an aspen.

In a very little time he passed again. Emily did not

think he was a robber, but what did he want with Albert? A

nameless horror crept over her, and she pressed her hand against her

heart to keep it from beating so fast. Then her baby woke and

cried, and she ran up-stairs, and Geraldine went and brought her

father and mother to look out also. But they saw nothing

particular in the fact of a man's asking for Albert, or walking up

and down waiting for him. Jerry ought to have asked him in,

they said. While they stood he did not return, and they

concluded therefore that, as it was getting late, he had gone away.

Beatrice had eaten her supper, and would not even stir to look out;

but Emily, as soon as she had got her baby off to sleep again, went

and stood in the dark at the front room window and watched—watched

alone, in spite of her fears, for the rest of the family had gone to

bed. How long she stood there she did not know; it must have

been more than an hour before she heard Albert come in. She

cried a little with relief from anxiety when she heard him, but

dried her tears to meet him.

The kettle was singing on the hob, and she asked if he would

take a cup of tea. He answered yes, and she set about making

it, without noticing anything unusual in his appearance; indeed, he

had been looking so haggard and wretched lately there was nothing

unusual to notice.

In her thankfulness for his return, and her anxiety to make

him comfortable, she had not yet told about the visitor, and she

nearly let the teapot fall from her hands when that knock (quite a

subdued knock, too, it was) sounded once more through the silent

house.

"It's the man," she said, trembling.

"What man?" asked her husband, crossly, drawing off his boot.

"A man who has been here asking for you," she answered, not

daring to say more.

He did not offer to go, as Emily would fain have desired, so

she took the candle and went herself down-stairs to open the door.

The man (for it was be) desired civilly enough to see Mr.

Albert Lovejoy.

"He has just come in," answered Emily.

The man actually walked into the passage and shut the door,

saying, "I'll follow you, if you please."

She led the way up-stairs, and the stranger followed, passed,

and entered before her. "You must come with me," he said

addressing Albert; "I've been waiting some time for you."

Ghastly with terror, Albert sat without uttering a word.

"What do you want him for?" asked Emily.

"He's wanted about a little matter of money that's missing,"

answered the man. "Don't take on so," he added, for Emily gave

a scream as if some one had stabbed her. "He may be all right

for anything I know, only I must do my dooty, and he must come alon'

with me."

Still Albert answered nothing, but began with haste to pull

on the boot he had taken off.

"Say it is not true, Albert—O Albert! say it is not true.

You never took any man's money. Say you never took it, and let

him go away," pleaded Emily.

"His saying it ain't true won't make any difference, he must

prove it," said the man.

"You can prove it, Albert?" she implored. "You we not

going away with him."

"Don't be a fool," he answered. "I must go, I suppose?"

and he looked at the man.

"No mistake about it," said the functionary, in answer to the

look.

"I am lucky!" ejaculated Albert. "Mind," he said,

turning to the man, "this is all a mistake."

"It's all a mistake," repeated poor Emily. "I am sure

you could be punished for taking up an innocent man."

"I'm only doin' my dooty," said the officer patiently, used

to such ineffectual wrath.

"Emily, be quiet, I tell you!" shouted Albert; and looking in

his face, white as the tablecloth, his wife read, with a sure

instinct, not innocence, but guilt.

Her heart died within her; but her manner, after the manner

of women driven by weakness to deceit, became lighter. "Will

you take your tea, Albert?" she asked; and turning to the man,

added, "will you take a cup of tea, sir?"

"I don't mind if I do," answered the man.

So they stood and drank each a cup of tea, the man pouring it

into the saucer and drinking leisurely, eating a slice of

bread-and-butter as well; Albert pouring it down his throat of at

the risk of a scalding, and biting the cup to steady it.

"Where are you going to take him?" asked Emily.

"To the lock up for to-night," answered the man, his mouth

full of bread-and-butter.

"Good-bye," said Albert, without looking at Emily.

She went over to him and kissed him. He kissed her

again mechanically.

"When will he come back?" asked Emily.

"It depends," said the man, swallowing a last mouthful.

Emily held the door open, and they went downstairs.

"Will you go in and tell them?" she cried, and Albert answered,

"No," and was gone.

Then Emily sat down alone; but not to cry—no tears would

come, only her poor little heart kept sinking, sinking, sinking,

till she could bear it no longer, and she crept up-stairs to the

room where Mr. and Mrs. Lovejoy slept, and stole in beside them.

In the dark, and kneeling on the floor beside their bed, she told

what had happened—it eased her heart to tell it; and then she went

away, and crept in beside her baby and cried herself to sleep.

CHAPTER XVII.

TROUBLE.

LOVEJOY had a nature as innocent as it was light and gay. He

could suffer privation with a cheerfulness which, to his very

differently constituted wife, seemed perfectly insane. He

would go without dinner, and make a late meal of tea and bread and

herring, with absolute graciousness; a man who for himself feared

poverty not at all. Its shifts, to others so painful, and even

disgraceful, were to him only little difficulties to be triumphed

over by patient endurance, and smiled at when they were past.

He had persisted in being a gentleman in the midst of them.

Disgrace in the true sense he had never experienced. When he

heard Emily's account of his son's capture, lying there in the dark,

he uttered not a word. Mrs. Lovejoy said but little.

She, too, had a conviction that the charge was true. But as

soon as her daughter-in-law left she rose. She could not lie

there, she said, and Albert in prison. Still her husband did

not speak. She lighted a candle and dressed, preparing to

leave the room, when he murmured, "I'm very sick, Susan; give me a

drop of water."

There was none in the room, and, with his usual habit of

sparing her trouble, he said, "Never mind, I'll rise too."

He rose, and they went down-stairs together and lighted a

fire, over which they sat shivering. All at once Mr. Lovejoy

moaned, and his wife looking at him, saw him grow deadly pale, and

be would have fallen had she not held him. He had fainted.

With some difficulty his wife managed to restore him, and prop him

up in his chair, and the spreading warmth of the little fire revived

him still more. As he became better, and Mrs. Lovejoy was

relieved from the anxiety she had felt while he was unconscious, she

began to feel a bitter contempt that he should take it thus, fall

down before this trouble as it were, while she maintained herself

erect, in spite of the raging pain at her heart. She was not a

woman who could be tender in her sorrow, and she was anything but

that now; she felt savage with her misery. She would have liked,

only she knew it was useless, to go after her son that very night.

She chafed at having to sit still there; it was only one degree more

bearable than lying in her bed. So the two sat over the fire,

neither attempting to comfort the other; Mr. Lovejoy drooping his

head, and at length laying it down on the wooden table.

"I can't think what I've done to deserve this," said his

wife, breaking a long silence. "He was as pretty a child as

ever was born, and I tried hard to do my duty by him; he never

wanted for anything that I could give him."

Her husband lifted a woebegone face. "And what have I

done, Susan?" he said. With sure instinct he picked up the

clue to her tangled thoughts, and found it was reproach to himself.

Thus we often know what people think, more from what they don't say

than from what they do. "I've been honest and honourable," he

went on; "through all our poverty I've never touched a farthing of

other men's money, though I've had my pockets full of it, and been

like to drop with hunger. God knows he has not learnt

dishonesty from me."

"If we had been comfortably off, if things hadn't been so

hard, he might never have been what he is. He never could bear

to be mean and shabby," said Mrs. Lovejoy, bitterly. (By "mean

and shabby" Mrs. Lovejoy meant in the outer man: that her husband

had never been mean and shabby, in his most threadbare garments and

with his empty purse, she had no comprehension.)

"I don't think be has had a very hard life," said Albert's

father. "Some people might think my life had been a hard one,

Susan, for I was brought up in luxury; but it hasn't; you've never

heard me murmur: it has been very happy till now. When the

children were young, Susan, do you remember how happy we were, if we

could only make ends meet and get bread and cheese? When we

went to Greenwich Park on a summer Sunday, and ate our dinners under

the old tree, and fetched water from the well to drink, we were

happy enough, and there wasn't a prettier set of children on the

ground than ours. Yes, we were happy then."

Accustomed as she was to his ideas, Mrs, Lovejoy stared at

him; she could not remember the happiness. She could remember

her husband proposing the park and bread and cheese, and no need to

cook a dinner, because there was none to cook. She had never

been happy, she thought, and truly; for to her happiness consisted

of purchasable commodities, and she had never been able to purchase

them in sufficient quantities. Even her stomach, temperate

though she was, rose at cold water with chalk in it, and preferred

London stout. She wanted to see her children well clad and

well shod, rather than down at the heel, and dancing in the

sunshine. It was the same life she and her husband were

looking at, and yet how different! the one saw all its squalor and

dinginess, all the manifold unpleasantnesses of its poverty; the

other dwelt upon its glimpses of sunshine and radiance, the beauty

of his little children, and all the unpurchasable pleasures.

Mrs. Lovejoy was by no means a bad woman; she was not even a

coarse woman, but she had not a spark of imagination. He, weak

as he was, had abundance of that Divine gift; it was this that had

redeemed him, and not as his wife thought be-fooled him.

Without it he would have been equally weak and far more worthless;

and as men cannot live without pleasure of some sort, he might have

been such another as his son Albert.

The haggard couple sat and talked at intervals throughout the

bitter night; they talked of him, and of their other children, whom

the mother alternately defended and abused. They were of very

mixed characteristics, from hard, cold, selfish Beatrice, to Ada,

whose affections centred in her father, and were of passionate

intensity. The mother's favourite was Geraldine, who had a

strong sense of duty, quickened by imagination—a sense of duty which

was always triumphing over her inclinations.

"I don't know what's come to Beatrice," her mother murmured

on; " I think there is some young man in the case, and that she

wants to get married. God forgive me, but I wish almost that

her child may give her as sore a heart as she has given me."

"Hush, Susan!" said her husband, "don't wish ill to your own

child."

"There's Jerry," she replied, "the best of the lot; she's got

a cough like to split, through wearing a thin jacket, and Beatrice

might have given us the money to get her a thick one, and wouldn't."

Mr. Lovejoy could only moan his grief: these children were

breaking his heart.

Towards morning Mrs. Lovejoy made a cup of tea, cheerfully

informing her husband that the coals would not last the day, and

there was no money in the house to get more. They did not wake

the girls till their usual hour; but they were thankful when that

hour came and the house was again astir, and the voices of Albert's

children were heard up-stairs. Emily brought them down and

came herself to see what was to be done for Albert. The first

thing was to see him if possible, for Emily did not even know at

whose instance he had been imprisoned. On this mission Mr.

Lovejoy went forth as soon as it was thought advisable. He

wasted several hours among a miserable little crowd, chiefly women,

waiting to see his son, which he at length accomplished, and learnt

what he chiefly wanted to know—the name of his accuser, and the

extent of his guilt.

The story which Albert told his father was substantially

true, with the exception of the way in which the money had been

spent, and which he persisted in saying he had lost. He was

full of the injury which Mr. Tenterden had done him in refusing to

lend him his cousin's money. Indeed, according to him, the

entire calamity rested on Philip's shoulders. Mr. Lovejoy next

went to his son's late employer and explained the circumstances.

He did it in perfect good faith, for he had taken to himself immense

comfort from his son's statement, that he had not the slightest

intention of keeping the money; but the man was inexorable, and

swore that, unless the ten pounds were paid down, the law must take

its course. It was a case of embezzlement, and he had had too

much of it lately, and was determined to make an example. At

that very hour he was sending out a short tale of goods to a great

company, whose manager and storekeeper he had bribed.

Mr. Lovejoy came away as miserable as he had been hopeful in

going to this man. He was faint, for he had traversed dreary

miles on foot, and he returned to the penniless little household

utterly exhausted. Emily got him some food; but he was unable

to eat it. He seemed completely broken down, and his

daughter-in-law took him up-stairs and made him lie down.

Ada's coming on that afternoon was hailed with joy by all the

family. Ada was soft and almost supine on ordinary occasions,

but she had a way of rising to emergencies. She went and sat

beside her father, and made herself mistress of the whole story.

Then she proceeded to act. She took up a burning hatred

against Philip Tenterden as the cause of all this suffering, and

seeing that the immediate issue was the getting of this ten pounds,

she set off, determined that he should be made to disburse it, with

every possible ignominy. She was but a child, without notion

of complicated motives, and with a pure and passionate will, which

on occasion could carry all before it.

She had no sooner got home than she poured her story into

Fanny's ears, and Fanny, knowing where Philip was to be found,

permitted herself to be dragged at once into his presence.

CHAPTER XVIII.

NEGATIVES AND POSITIVES.

"I CAME in to

speak to you, Philip," gasped Fanny; "I knew you were here."

"You could have sent for me," he replied, not very

graciously.

"It's about Albert," she returned.

"Had you not better wait, and I will come in when I leave

Mrs. Austin? It was my intention to do so," he said.

Fanny looked at Ada, as if for inspiration; but she had been

smitten on entering the room with her usual childish shyness, and

shrank behind her cousin.

"Go into the dining-room, Fanny, if you want to consult Mr.

Tenterden," said Mrs. Austin. She was aware of Fanny's

difficulties already.

Philip said, "Thank you," and led the way into the Opposite

room, and Ada was left behind— a proceeding which she did not at all

approve.

Mrs. Austin tried to find something to say to her, but

failed. Nothing but a faint monosyllable could be got out of

her. Happily she could still be treated as a child, and left

in silence if she did not choose to talk.

The interview in the next room was, however, prolonged, and

Ada's pent-up feelings found relief in an angry sob.

"What is the matter, dear?" said Mrs. Austin, going over to

her. "What has distressed you? Are you ill? Can I

do anything for you?" She asked her questions out of simple

tenderness, not at all anticipating the embarrassing answer.

"He has all my cousin's money, and he will not let her have

any of it," burst from the girl's pale lips.

"Who?" said Mrs. Austin, mechanically; "Mr Tenterden?"

"Yes, Mr. Tenterden."

"You do not understand matters of business," sais Mrs.

Austin, soothingly. "Mr. Tenterden will do what is right."

"My brother is in prison, all through his fault!" said Ada.

Mrs. Austin was aghast at the girl's unexpected revelations.

She would have kept them back if she could; and she hastened at once

to put a stop to them. "I think you must be mistaken," she

said; "but at any rate you must not speak in this way: it might do

more harm than you are aware of."

Just then Fanny returned with Philip, the latter looking

deeply annoyed, the former very subdued. She called to Ada to

follow her at once, and went off as she had come; and Philip only

stayed to explain that he had some unpleasant business before him,

and left also. His manner was constrained and unnatural, and

went far to deepen the impression which Ada's words had made on the

mind of Mrs. Austin. Had she been standing on the brink of a

precipice? Was Philip guilty of some secret wrong, and

unworthy to be loved or trusted? She had caught glimpses of

his mind which revealed a higher and purer standard of right than

most. If he was not to be trusted, there was no one worthy to

be trusted. All life was a lie—nothing was true, nothing was

pure, nothing was holy. Ellen passed through hours of

deepening anguish, tormented by thoughts like these. Hour

after hour she sat in her lonely room, like a woman turning to

stone, and at length there breathed through her pale lips the

prayer—"Give me something to love, or let me die."

Ellen Austin was more to be pitied than blamed for the

distrust which had so readily taken possession of her spirit, for

she had seen too much of the untrustworthy side of human character;

but in the daylight, she reproached herself severely for

entertaining such thoughts. She was, however, so depressed and

unhappy that she sat down and wrote to her mother, begging her to

return as soon as possible; and knowing that she was already

heartily tired of, "dear Julia's," that might mean as soon as the

earliest train could bring her.

Philip immediately set about obtaining the release of Albert

Lovejoy, which he accomplished without much difficulty on the

payment of the ten pounds and the legal expenses incurred. The

virtuously indignant employer considered this a much more

satisfactory process than that involving the trouble and worry of

prosecution, and the loss of his money besides, and willingly agreed

to stop proceedings.

Though glad enough to be set at liberty, Albert Lovejoy was

by no means grateful to the instrument of his liberation. Of

course, he would never have been imprisoned at all if Philip had

given him the money, as he ought to have done, therefore the effects

of that stain upon his character were to be laid at Philip's door.

That was Albert's way of looking at it, and more or less the way in

which the whole family looked at it; for though they knew him well

enough to be able to give him a full share of private

disapprobation, still he was one of them, and it was not in human

nature to approve of any one who had injured him, Philip was

henceforth to be regarded as the enemy of the house; and he was thus

regarded by none more than by Ada, whose antagonism to him was more

marked than that of any other member of the family.

Fanny had come to be very fond of her young cousin, though

the girl at first made not the slightest pretence of affection for

her. Indeed she showed plainly that her only care was for

those she had left, and she acted as a perfect conduit through which

Fanny's money and Fanny's goods might find their way to them.

But she gave very little other intimation of what was passing in her

mind; questioning endlessly, but very seldom volunteering any

opinion. Fanny was never tired of admiring the girl's

dexterity in everything that could be accomplished by hand; the

multitudinous pieces of fancywork, strewed up and down the house,

grew and flourished. There was nothing she couldn't do with

needle and thread and scissors, and other like implements, picking

up the most elaborate patterns in a moment. And Ada's mind was

as dexterous as her fingers; it gave her not the slightest trouble

to adapt herself to all her surroundings, to fall in with the

minutest requirements of a new code of manners. If she had

been suddenly transformed into a princess, it would have been

impossible to tell that Ada had not been born to the purple, she

took everything about her in the world so simply and grandly.

Fanny took her with her everywhere; she had been several

times in at Mrs. Tabor's, and Lucy, who had been attracted by the

pale, perfect face and great grey eyes, carried her off one day into

her own room, where she entertained her particular friends. It

was a pretty little room, lined with books and pictures, and filled

with every conceivable variety of nicknack; a case of ferns in one

window, a tank of gold fish in the other; a lovely azalea blossoming

here, and a pot of tulips there.

Ada looked round her with interest, and Lucy seated her in a

rocking-chair, and began to talk to her. Ada was two or three

years younger than Lucy, but incalculably older in her knowledge of

life.

"Are you fond of music?" said Lucy, making a beginning.

"Yes," replied Ada, simply.

"Perhaps you only like it when it is very good. I like

playing and singing to myself, but I am not a first-rate musician.

Do you like reading?"

To this came the unexpected answer, "No," given quite

unhesitatingly.

"I don't mean hard reading," said Lucy, smiling, "but tales

and novels. Perhaps there are some of mine you have not read."

"I don't care for tales at all," said Ada. "What is the

use of reading what is not true?"

Lucy could not know that Ada's experience of tales was

confined to those of a rather low kind, patronised by Beatrice.

The answer gave Lucy a great respect for her young companion, for

reading novels was a weakness which she had to guard against by

restricting the enjoyment to the least useful portion of her day.

"I like to read useful books," added Ada, still further

increasing Lucy's respect.

"History?" suggested Lucy.

"Yes, if I could be sure it was true."

Lucy broke into a merry laugh.

Ada smiled gravely. "I like best to know how people

live," she said.

Lucy regarded her with smiling astonishment.

"Have you lived all your life here?" said Ada.

"No, not all my life; I remember living in Finsbury Square."

Ada knew where that was. "Do you like this better?"

said Ada.

"Oh yes, we have a garden here, and lovely walks all round."

"That is like the little church on the hill," said Ada,

pointing to a picture.

"It is a drawing of mine," said Lucy.

"I should like to learn to draw," said Ada.

"I might help you a little," said Lucy; "and here is a little

book," (and she took down Mr. Ruskin's "Elements,") "which would

help you a great deal."

"Thank you," said Ada, quietly, and standing up to examine a

statuette.

"That is Florence Nightingale with her lamp, and this is a

reduced copy of the Venus of Milo."

"I like that best," said Ada, pointing to the latter.

On the mantelshelf were several photographs on small

stand-frames.

"Do you know this gentleman?" said Ada, quickly pointing to

one of Philip—certainly a very flattering one, for a bright smile

illumined the whole face.

"Yes; he is my father's partner," said Lucy.

"I hate him," said Ada, coolly.

Lucy looked shocked and pained.

"He has all my cousin's money, and he will not let her have

it," she repeated." There was no sort of compromise with Ada.

"You ought not to hate any one," said Lucy, looking with

pained reproof at the girl, and then pointing to a print of the

Saviour which hung in the recess by the fire-place.

"Are you very good?" said Ada.

"You queer child—no," said Lucy.

"I am sure you are," said Ada, taking Lucy's hand and kissing

it.

Half attracted, half repelled, Lucy drew her close to her and

kissed her forehead. She wondered if this strange girl put

every one through as close a cross-examination. She ought to

have heard the question Fanny had to answer.

Ada was looking at the azalea.

"Do you like flowers?" asked Lucy.

"No, but my father and Geraldine do," said Ada.

"Will you take this one for Geraldine?" said Lucy.

"Come with me and see the conservatory first."

Ada followed. They passed through the dining-room, and

Ada, examined everything. Mr. Tabor would have been abundantly

satisfied with her interest in his pictures. When Fanny went

away, Ada carried off her azalea wrapped in a newspaper, and she was

impatient to be allowed to carry it to Geraldine without delay.

Of course Ada had her way, and she and her carefully-guarded

treasure arrived at home that same afternoon. But she was

doomed to disappointment. She unveiled its glories to eyes

which were too dull and weary to rejoice in them. Her father

sat in the chimney-corner, drooping and despondent. He had

never recovered the blow he had received on that miserable night of

Alfred's capture. It seemed to have struck the very colour out

of his eyes. His beard was untrimmed, his whole aspect

dishevelled. Her mother hardly raised her eyes from her work.

Geraldine was working, too, but fitfully. Ada came in, looking

fresh as the white blossoms in her hands, and set the pot on the

table by her sister's side. She kissed her father first, then

her mother, and then she went and hung over Geraldine's chair.

"How pretty it is," said the latter, leaning back with a

sigh, and adding, "oh, Ada! I am so tired."

"I wish I could help you, dear," said Ada. "Let me do a

bit while I stay;" and she took up the work dropped by her sister's

hands. "How hot your hands are—and your cheeks—and your

breath!", she exclaimed, as she touched her lovingly.

"Oh, Ada! I am so ill," moaned the girl; "I can't eat,

and I can't sleep, and I can't work, and nothing but cough, cough,

cough all night long."

Ada's great eyes took a startled look, and mouth drew to a

close line as she looked at sister's altered face.

Geraldine shivered.

"What has made you ill, Jerry?" said Ada.

"It's easy enough to tell what has made her ill," said Mrs.

Lovejoy, while she worked on faster than ever; "it's the poor living

and the cold nights. She'll never get well if things go on as

they're doing."

"Mother, she shall get well!" said Ada, in a voice which

startled them. "She shall go to Cousin Fanny's instead of

me—this very night."

"What nonsense!" said her mother, sharply.

"No, it isn't nonsense, the same things fits both, and Jerry

shall put on mine. She won't feel the cold through this thick

jacket. Jerry!" she cried eagerly, addressing her sister,

"couldn't you eat nice things, and sleep in a nice warm bed, and get

well if you had nothing to do?"

An eager, wistful assent came from poor Geraldine's parched

lips, but she said, "No—no, Ada, I can't take your place. I'm

glad you're so well off, dear."

"But you must—you shall!" said Ada, at white heat; "I won't

stay there, if you don't. I won't go back again."

"I'm sure we don't want you here," said her mother, bitterly;

"and don't go and add to our troubles by offending your cousin.

You know very well that Jerry can't go without being asked."

Ada subsided; but the look on her face was one of triumph

still. She laid on the table the silver Fanny had given her to

pay her fare by omnibus and cab, and said, "Good-bye," speedily

setting out to walk the whole immense distance as she had done once

or twice before. Nor had she slackened in her purpose by the

time she had reached what was now her home. She flung herself

down on the hearthrug at Fanny's feet, and begged that Geraldine

might come to live there instead of herself.

"Don't you like living with me, Ada?" asked her cousin, not a

little hurt at the request; "don't you love me a little?"

"Yes, I like you a little; but I will love you all my life,

if you will only take Jerry instead. She will die there."

"Dear me!" said Fanny; "is she ill then?"

"If she stays there, with the work and the cold, and not

being able to eat the things we have at home, she will die."

Ada fell to weeping bitterly.

"Hush!" said Fanny; "don't cry, Geraldine shall come."

"To-morrow?" said Ada, with a sob.

"To-morrow," repeated Fanny. "Come and have some supper

now."

CHAPTER XIX.

A PROPOSAL UNPROPOSED.

had taken the success of Arthur Wildish for granted, seeing that

there was no interruption to the friendly relations between him and

Mr. Tabor. Philip did not see Wildish quite so often at the

office, but then he had gone up to him in the neighbourhood of Park

Villas, averring that the air of Kensington did not agree with him.

And Philip was not more miserable than he had been before. It

may seem paradoxical, but he would have been more unhappy if he had

been in happier circumstances. He had long ago made up his

mind to the result. He had made up his mind that he could not

marry for years to come, and that he could not ask Lucy in her first

bloom and freshness to waste those years in waiting for him, already

a jaded man, even if the result of such asking had been sure, which

to him it did not by any means appear. He felt doubtful

whether she had ever cared for him at all in the way he would have

desired; whether she did not look upon him—kindly, it is true, but

as a friend—almost on a footing with her father. Besides which

he could not approach her on the subject at all, without a

preliminary explanation of circumstances which he had hitherto

concealed.

Then, as to Wildish, if he had had a favourite sister, was he

not just such a husband as he would have desired for her—pure,

affectionate, generous, high-minded? Still it was hard for

him, a man of superlative energy, to stand by and make no effort to

win the prize he most coveted; to see another step out of the ranks

and claim it. The motive that held him back must have been

strong indeed.

There were times when Philip, who had in him a distinct

fighting propensity, and had been an enthusiastic rifle volunteer

(it was one of the things it had cost him most to give up, this

volunteering), longed to throw up everything and lead the life of an

adventurer in foreign lands. He allowed himself to indulge in

dreams of such a life, generally ending in the thought, "When I am

free—bah! when I am free, it will be too late for anything."

His last evening with Mrs. Austin to be devoted to the papers

had arrived. Their task was almost finished, and he was in the

mood to derive a melancholy pleasure from the fact. He was

fond of Ellen's ready sympathy; but he felt that he would make no

effort to keep hold on it. He would probably part from her

that very night, and allow her to drift away from him beyond recall.

He was completely undecided, or rather, for it better expresses

Philip's mind, the only thing he had decided upon was indecision.

He would let circumstances decide for him and the decision was

forthcoming.

There, in her seat in the chimney-corner, sat Fate, in the

shape of Mrs. Torrance, knotting her threads as vigorously as ever,

with the ball at her feet, and the bag containing her web more

distended than ever. Mrs. Torrance had an air of extreme

satisfaction. It arose from the consciousness of having

performed every maternal duty to "dearest Julia," while "dearest

Ellen" had found it necessary to recall her just when those duties

were becoming unnecessary and therefore irksome.

Mrs. Torrance sat and watched from her corner the progress of

the almost finished task. She watched also, with jealous eyes,

the progress of something else, and that was the friendship between

Mr. Tenterden and Ellen, which had evidently been making rapid

strides during her unavoidable absence. Ellen had not said

much about Mr. Tenterden, and now he was not the only trouble

looming in the distance. Mrs. Torrance had been at home but

six days, and in that short space of time Mr. Huntingdon had called

twice. On the last occasion she had found him sitting

suspiciously close to Ellen, with an expression on his face as if he

was engaged in some personal confidences. Nor was her

penetrations at fault, though from Ellen's manner she could gather

nothing, and and the latter offered no explanation, a had only

mentioned that in her absence Mr. Huntingdon had been a frequent

visitor. Now Mrs. Torrance had as much objection to her

daughter marrying the clergyman as the layman. In the first

place, Ellen by a second marriage lost a considerable part of her

income—that which was derived from the profits of the firm, which

she shared to the extent of one-third, and which in that event

reverted to the partners. In the second, she had not found

husbands at all conducive to generosity or gratitude on the part of

her daughters; not that she was a merely mercenary woman, far from

it. Thanks to Ellen, she had quite enough to live upon, and

would have been delighted to spend her little income on these very

ingrates; but she wanted to manage for them; she coveted a first

place in their consideration and affection; she desired to deal with

refractory servants, refractory babies, and even refractory husbands

after her own fashion. Ellen allowed her to rule to her

heart's content, but if she married again it would be quite

different. Ellen would no longer be her own mistress.

Ellen's house would no longer be a haven of refuge when the husbands

of dearest Bessie and dearest Julia proved refractory. Ellen

might have a refractory husband of her own, and as Ellen was never

known to manage anybody, of course he would have it all his own way.

Mrs. Torrance conscientiously considered that it was better for

Ellen to remain as she was.

In reality Ellen was in much greater danger than Mrs.

Torrance supposed. On the occasion when she had interrupted

Mr. Huntingdon's confidences, they were indeed leading up to a

declaration. These confidences suddenly made were rather

startling to Ellen, who had no idea of their drift till it was too

late to stop them. Mr. Huntingdon had hitherto had some

pretext or other for his calls, and he had pitched his intended

declaration in the lowest possible key, which was certainly in his

favour as far as obtaining a hearing went. He was very poor,

he said, poorer even than he seemed, for he was paying back to his

parents, now in reduced circumstances, the money they had spent on

his education. It was most likely he would have to support

them entirely in the end, as well as a deformed sister, who, though

very clever and accomplished, and willing to teach, found the utmost

difficulty in getting a situation as a governess or companion.

He was very straightforward and manly in his bearing as he told her

he could only marry a lady who had money, and that both the lady and

her money must lend themselves to further his usefulness in the

ministry to which he had devoted himself. He acknowledged that

there was nothing very tempting in the offer he had to make.

Did Mrs. Austin think it was one that was worth listening to by any

good and loving woman for whom he could have the necessary affection

and esteem? At this point Mrs. Torrance had broken in upon

them and rather disconcerted Mr. Huntingdon, and he took his leave,

holding Mrs. Austin's hand, which trembled in his, while he begged

her to think over what he had been saying, which might have had

reference to anything, from mothers' meetings to matters of faith

and doctrine. But Ellen had no alternative save silence, for

up to the last moment it would have been impossible for her to make

a personal application of his words.

And now with Philip there was a grave constraint in her

manner, which he set down to the presence of her mother.

Almost in silence they went on with their task, drawing quickly to a

close, but it was not destined to be uninterrupted as heretofore.

At an early period Mr. Huntingdon presented himself, dropping in of

an evening being the habit of an intimate in the little circle, a

habit never before practised by him, and therefore all the more

marked. The servant had shown him into the drawing-room, and

came and announced to her mistress his presence there. Mrs.

Torrance knotted furiously, and her daughter suffered an

embarrassment she could not wholly conceal, and which was increased

by the servant saying that she had shown him into the drawing-room,

because he particularly desired to see Mrs. Austin alone, and would

retire if she was engaged.

"Mamma," said Ellen, "I wish you would go to Mr. Huntingdon,

and I will come to him in a little."

Mrs. Torrance went with alacrity. Mr. Huntingdon was

certainly the most dangerous of the two. This was something

like an emergency, and Mrs. Torrance's spirit rose to meet

emergencies. But her going left Ellen embarrassed as before;

nay, her embarrassment increased rather than diminished.

It was apparent to her companion, who rose and said, "We have

very nearly finished our task, Mrs. Austin; another short sitting

will do it, and I had better leave you now."

Ellen hesitated. "No, stay," she answered; "I dare say

Mr. Huntingdon will not detain me long. I should be sorry to

give you more trouble."

"Make your mind easy upon that score," he said; "it will only

be lengthening out a pleasure. I will say good-bye, to-night;"

and he did say good-bye, putting on his hat and rushing out of the

house in the strangest manner possible; while Ellen lingered beside

the writing-table, unable to make up her mind to encounter Mr.

Huntingdon.

Meantime Mrs. Torrance had been entertaining the clergyman,

who was seated in an arm-chair looking absent and answering at

random. Mrs. Torrance mentioned that her daughter was engaged

in some business with Mr. Tenterden, assuming at the same time that

Mr. Huntingdon knew him well.

Mr. Huntingdon murmured that he had met the gentleman in

question, but that they were not likely to be friends, as they

differed very widely in opinion.

"Indeed!" rejoined Mrs. Torrance, point blank "what opinions,

may I ask?"

"I think his are rather dangerous, to say the truth," said

Mr. Huntingdon, rousing himself.

"You surprise me," said Mrs. Torrance; "my daughter and he

are great friends. He is partner in the firm of which Mr.

Austin was the head, and Mrs. Austin has still her share in the

business you know, as long as she remains unmarried. If she

marries again," she added, hitting her nail on the head and driving

it home, "she loses everything."

She justified the statement to her conscience by taking it to

mean everything from that source, and went on smoothly to other

topics, presently wondering that her daughter had not appeared, and

leaving him with the hope that he would not be detained much longer.

How much longer he was detained, poor Mr. Huntingdon never

knew, for in that time he went through an agony of humiliation and

shame enough for a whole lifetime. He had come there to ask

the sweetest and noblest woman he had ever met to be his wife, and

he must go away, not only without accomplishing his object, but

relinquishing it for ever, and relinquishing it for a motive which

at that moment he could not but feel to be an utterly ignoble and

ungenerous one. Money, money, more and more money, was the

pitiful craving created by an age of luxury and false refinement.

Why could he not marry Ellen? the idea flashed wildly across his

brain. He felt that he had never known his own heart till now,

so disguised had it been in the swathings of conventionality.

Now he seemed to see it throbbing nakedly. Why could he not

marry Ellen on a hundred and fifty pounds a year, while his parents

and sister lived on the other moiety of his income? Why must

he have a costly house and costly furniture and several servants?

Why could he not live differently to the people of his class, and be

an example of plain living and high thinking? No, he felt he could

not. A great genius might do it, or a great Christian.

He was neither, but a common man among common men. If he did

any such thing the bland men and sugared women of the villas round

him, even those who had still some trouble with their h's and final

r's would look down upon him, turn their backs to him, hide their

faces from him in spite of his superior education. His last

chance of usefulness among them would be gone. He would be in

the position of their own or their fathers' clerks. They would

look upon him, the servant of God, as their servant, and that not in

the sense in which he truly was theirs and every man's. No,

the man to do such a thing must be one who was not under the

necessity of doing it. So difficult is it to live on a higher

level than the people about one. All this flashed through his

mind in far less time than it takes to write. And what should

he say for himself? She must know what he had intended by

coming there that night, and he must give her an explanation.

Should he get out of it as easily as possible, invent some excuse

for the occasion, and let the thing die a natural death? Alas!

feigning and falsehood! had he come to that? His anguish was

unspeakable. It paled his ruddy face, as if with deadly

sickness. His head sunk down till it was almost bent upon his

knees as he sat.

At length Ellen came in, and he rose to meet her and held out

his hand. She took it, and it was cold and clammy. He

stood looking at her face for a moment, for his lips were too dry

for rapid speech, while she met his eyes calmly and feelingly; but

the words he uttered, strange as they were, gave her immense relief.

"Forgive me, I have offered you an insult. You must

know what I came here to say, I cannot say it. My

circumstances will not allow me; but I never knew how much I cared

for you till I was forced to give you up."

She could almost have smiled, so different was it from what

she had expected and dreaded; but she saw that he was in deadly

earnest, his face, his voice, his manner, all betokening an

overpowering agitation, and instead of telling him that his suit

would have been in vain, she spoke the kindest words she could think

of. "You have honoured me with you confidence, Mr. Huntingdon.

I cannot look on your withdrawal as an insult, and I would fain

retain your friendship under any circumstances."

"God bless you!" he said, and left her somehow with tears in

her eyes.

CHAPTER XX.

PHILIP'S INTERFERENCE.

FANNY'S

Money was melting like snow. Instead of sending Ada home and

taking her sister in her stead she went next day along with Ada, and

brought both girls back in her cab—a piece of native generosity,

which really won for her the prize she coveted. Ada took her

into the circle of her close affections from the hour. But

that did not mean that she was not going to make use of her.

The more she loved her, the less compunction she had about spending

her money, just as she would have spent her own if she had had any.

She negotiated loans for her father and for Albert and his wife, who

would otherwise have been under the necessity of parting with the

last relics of comfort and respectability—in short she was the

channel through which the whole family had begun to draw their

support, with the exception of Mrs. Lovejoy and Beatrice, who stood

aloof and independent. Nor did this state of affairs seem

likely to come to an end at any very early date. A fortnight

passed, and Albert had not found another situation. During the

first week two had offered; but his applications had been rejected,

and he was beginning to be hopeless. Geraldine was no better

and the doctor whom Fanny called in looked grave over her case—far

more grave, it seemed, than her illness warranted, for she was often

quite cheerful and free from suffering. Still the fact remain

that she did not gain strength, and the little cough could not be

removed, so that under the circumstances she could not be sent home

again.

The constant drain on Fanny's purse at length necessitated

another application to Philip, and Fanny was weak enough to let Ada

see the reluctance which she made it.

"It's your own money, Cousin Fanny, is it not?" asked the

girl.

"Yes, of course it's my own," replied Fanny; "but Mr.

Tenterden keeps it for me, and he doesn't like me to spend too much

of it."

"I wouldn't let him keep my money," said Ada indignantly; and

the idea took roothold in the girl's determined mind, that Philip

ought to be made to give it up, and, like other ideas that take root

thus, it was destined to bear its fruit.

This time Fanny determined to see Philip at the office, and

she took Ada with her as a kind of protectress. It was

curious, the ascendency which girl had already obtained over the

woman's mind. Ada herself was quite unconscious of it, had

neither schemed for it, nor worked for it in any way; but Fanny's

ideas, being always in a state of fluidity, required a channel to

flow in, and Ada had the power of making channels. The girl's

mind was intensely practical, and though free from meanness, even in

the midst of mean surroundings, always went straight at the nearest

object, removed the nearest obstacle, did the nearest duty, however

small. And it was this directness and fixity of purpose that

enslaved Fanny. In the small affairs of the household Ada's

faculty brought order out of confusion, and good out of evil, and

Fanny's trust in her was therefore unbounded.

Fanny took Ada with her, and she acted as a check on Philip

to such an extent, that at length he begged her to go into the outer

office for a few minutes. He could not warn Fanny against

Ada's family in Ada's presence; but as soon as she was gone he did

remonstrate warmly. And Fanny was uncomfortable under the

remonstrance, and wished, for the first time, that her money was in

other hands. Philip evidently exaggerated her incapacity to

manage her own affairs. She was only lending, which was not

the same as giving, and yet he spoke as if it was. In the end

he gave Fanny a cheque for the sum she wanted; but he made it as

difficult as possible for her to apply to him again.

When the interview was over he bade her good-bye evenly, and

led her into the outer office to Ada, of whom he took the slightest

possible notice.

But though Ada had been excluded from the interview, she

managed by judicious cross-examination to obtain from Fanny a

particular account of it.

"Why do you let him keep your money?" she repeated

indignantly.

"He has always had it," replied Fanny, limply.

"Always—I don't understand," said Ada the Practical.

"His father managed for me when I was a girl like you," Fanny

explained.

Ada was silent for a while. Then she spoke suddenly,

her thoughts having been busy enough the while. "What if he

has spent the money himself, Cousin Fanny?" she said.

"Oh, no fear of that," answered Fanny.

Nevertheless she felt uneasy when Ada answered with

preternatural assurance, "I do believe he has;" a view of matters

which Ada was not at all likely to keep to herself.

Once more in his room, with the best of the day before him,

for Fanny had paid him a very early visit, Philip thought over

Fanny's affairs with his usual concentration. He greatly

exaggerated her incapacity, and did not give her credit for sense

enough to stop short of absolute ruin, and concluded that it was

necessary to keep a tighter hand on her ever. He also painted

the Lovejoy family in blacker colours than they deserved, and

determined to put a stop, as far as possible, to their exactions,

and also to interfere more decidedly in their affairs.

And, in the first place, what was to be done with that young

man? Fanny had not said too much about his difficulties in

obtaining employment. Who would employ him without a

character? It occurred to Philip that there was a vacancy in

the office at that very moment, a vacancy which any lad could fill.

Should he place Albert in it for a time? The salary was a mere

pittance; but the situation might be a passport to something better,

might reinstate him among honest men. He disliked the idea of

bringing him there—disliked it intensely; but that was no reason

with him for not doing it, rather the reverse. He could do no

harm, for there would be nothing in his power. He would be

removed from the influence of bad associates. In short, having

entertained the suggestion, Philip determined that it was the right

thing to do, and he sat down and wrote to Fanny at once, asking her

to send the young man to him, and telling her, not too graciously,

his intentions toward him.

Albert's qualifications were found quite equal to the office,

a faultless style of penmanship running in the family, and he was

only too glad to accept the eighteen shillings a week attached to

it.

Fanny was quite delighted with Philip for his interference in

the young man's behalf. Even Ada was coming round to a belief

in Philip's goodness, until she went home one day and heard Albert's

opinion concerning the benefit conferred on him. In his

estimation it was neither more nor less than a shabby dodge, which,

taking advantage of his unfortunate circumstances, secured his

invaluable services on utterly inadequate terms. The shock of

this discovery Ada lost no time in communicating to Fanny; and it

ought to be borne in mind that it is only robust minds which throw

off successive shocks of this kind. Fanny's was not a robust

mind. She began to be uncomfortable about her money.

Ada had received her account of Albert's way of taking

Philip's kindness from her mother, who believed it with that kind of

impatient half-belief which people give to the most untrustworthy

when they happen to be closely connected with them, because, as some

one has said, even the most untruthful necessarily speak more truth

than falsehood. Besides, as everything seemed to be going

against Mrs. Lovejoy, the worst interpretation seemed the most

natural at the time. Her daughter Beatrice was troubling her

sorely. Letters had lately been coming for her nearly every

day, and an expensive valentine had reached her on the morning of

the fourteenth of February. Also her mother had caught the

glitter of jewels in her ears one night, and she had gone up to her

room and taken them off and hid them away. She was often late,

too, in returning home, and had been remonstrated with in vain.

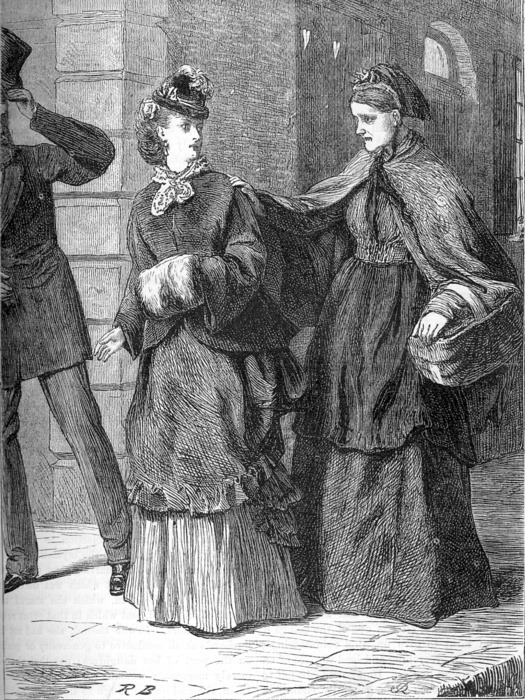

At last Mrs. Lovejoy, on the watch continually, had seen her

parting with a young man of gentlemanly appearance at the end of the

road, which led to the better-class streets of the district.

The mother's heart beat fast as the young man stooped and kissed the

girl, who held up her face as if accustomed to the salute.

Mrs. Lovejoy was not the woman to be passive under the

circumstances. She went up to her daughter, in her shabby

bonnet and with her basket on her arm, and laid hold of her, putting

the young gentleman to instant flight.

"Who is he?" she asked sternly.

(Drawn by ROBERT

BARNES)

"'Who is he?' she asked sternly."

"A friend of mine," answered the girl, defiantly.

"A friend of yours!" replied her mother; "and how came you to

know him, pray?"

"I met him in the train."

"And on the street," said her mother. "Do you think

that is the way respectable girls meet their lovers? In my

time girls saw their friends under heir parents' roof. If he

won't come to see you there, he means no good to you."

"I haven't a home fit to bring him to," said Beatrice,

scornfully.

"Has he a home fit to take you to then?''

"Yes, he has, and a mother and sisters?"

"And have you seen them?" asked Mrs. Lovejoy more calmly.

"No," faltered Beatrice, "not yet."

"Then the sooner you give him up the better," said her

mother. "He's only some selfish fellow who wants to make a

fool of you."

"I can take care of myself," answered Beatrice, with a hard,

unpleasant laugh.

And indeed, whatever the young man was, it would have been

very difficult for him to be more selfish than Beatrice Lovejoy.

CHAPTER XXI.

FADING.

winter had been a mild one. The spring came early. All

about the neighbourhood of Park Villas the hedges were greening.

Primroses were gleaming in the gardens, and would have been gleaming

on the banks, but that it was too near London for the least flower

to live in freedom. There was that indescribable sweetness in

the air which is felt in spring-time only, though it is no longer

the season of the poets. The birds felt it, and sang; the

earth felt it, and blossomed. Alas! for those who did not or

could not feel it—for the pent-up city children; or the youth

cankered and blighted; for the manhood, conscious that a glory has

passed away alike from earth without and spirit within.

Lucy Tabor came out of the house and into the high-walled

garden, in the sweet March morning, and stood on the steps for a

moment listening to the birds, the sunshine bending down her

eyelids. Muff jumped about her, and wriggled his fat little

body with delight, and started away as if he was saying, "Now for a

run." He made more than one start and came back again,

wriggling and whining, for his mistress did not move. She used

to try races with him down the garden walk, and that was what he

wanted now. He looked up in her face and said so—plain as dog

could speak.

(Drawn by ROBERT

BARNES)

"Lucy Tabor came out of the house."

She understood him perfectly. "No—no, doggie," she

said, and shook her head at him sadly. A sparrow lighted on

the path and Muff was after him as fast as his little legs would

carry him. The bird hopped on to a branch of lilac, and

chirped at him, chaffing him unmercifully. He felt it, and

came back to his mistress a miserable dog.

Lucy's eyes ran along the ground. On the brown earth

the bright spring flowers shone radiantly. Here a cluster of

crocuses shot up their tiny flame-spires; there a knot of primroses

lay like drops of sunshine, and a solitary snowdrop hung its head

between. With a sigh Lucy stooped and gathered it. Then

she went down the walk, from spot to spot of blossom, and gathered

all she could find. She brought in quite a posy—the firstlings

of her flock. Her mamma was in the dining-room still.

Mr. Tabor had been gone an hour or more. "See," said Lucy,

holding the flowers towards her mother; "and, oh, mamma! to think

that they are blooming and that she is fading."

The flowers she had gathered were for Geraldine Lovejoy.

As the spring had advanced she had become weaker and weaker, and now

the doctor had given it as his private opinion that she could not

recover.

Lucy had been deeply interested in Geraldine from the first.

She liked her better than she liked Ada, whom she did not quite

understand—indeed, it would have been strange if she had, for Ada

did not in the least understand herself. Geraldine, whose

qualities lay more on the surface, loved books and flowers and

music, which Ada could not satisfy herself with, because other

things were so much more necessary, especially money—which, indeed,

could procure them all, and the girl brooded, and was dissatisfied,

and restless and eager, and, it seemed, worldly in her eagerness.

So Lucy brought Geraldine her favourite books and read them to her,

and in the new atmosphere, and her invalid quietude and calm,

Geraldine's mind grew like a hot-house plant. Life appeared

before her in a totally new aspect; no longer a treadmill round of

working to live, and living to work, barren of all nobler result,

but a great triumphal progress, leading to all that heart could

desire of beauty and good.

Everybody round her, too, was so kind, so good, and indeed it

seemed as if the little circle of Park Villas had wanted something

on which to expend their more unselfish affections, so great was the

flow of tenderness towards the fading girl. Lucy was a daily

visitor, and Arthur Wildish found his way there in her train, and

furnished an enlivening element, especially delighting in drawing

out Ada.

For Mrs. Austin Geraldine had developed a strong attachment.

Mrs. Austin would bring her costly delicacies, but there was

something in Ellen which was more to the girl than these. She

had little enough appetite for earthly food; but she had an

undefined craving for all spiritual nourishment, and she had

fastened upon Mrs. Austin as the one from whom she desired something

that the others had not to give. There was something religious

in Ellen's aspect which attracted the girl, though no word of formal

piety had been spoken between them.

Geraldine, though she knew it not, was fast fading away from

earth. At first she had not assumed invalid habits at all, but

had gone about the house, with her slight cough and drooping figure,