|

ESTHER WEST.

CHAPTER I.

ESTHER THE QUEEN.

HURST COMMON was glowing in

the golden afternoon. It was thickly set with furze, which was in

full bloom. At a little distance, it seemed a field of black

embossed with gold. Through the midst of it ran a broad green path,

at one end of which, built upon a yellow sand-hill, stood a lonely house

called "The Cedars," while at the other was the village of Hurst.

It was only two hours after noon, and the light that lay on

the landscape had only gained in vividness from the touch of shade laid on

here and there. But the low furze bushes cast no shade on that belt

of shining green, soft as velvet, and elastic beneath the pressure of the

feet. There was a pool at the village end, flashing like a mirror,

and a flock of geese had risen from its margin, and, led by a mother goose

of most goose-like solemnity, proceeded up the path, as if out for a

constitutional.

From the other end advanced a young girl—a figure on which

the light rested lovingly, as it rests on a water-lily. There was

something singularly pure and cool about Esther West; and yet she was no

slender reed of a girl, but a tall and stately maiden, of ample

proportions and perfect health. Perhaps it was to her proportion of

face and figure, and also to a certain proportion of mind—which gave

strength and calmness to all she did and said—that she owed her peculiar

charm. I will try and describe her, for I do not hold with those who

care not to paint the outward form. There was very little colour

about her, yet she was not white. Though I never paint her mentally,

but always sculpture her, if I may say so, she was not at all a marbly

woman. Pure, tender greys predominated in her face; she had masses

of shady hair, that was neither fair nor dark; long, lovely eyebrows of

the same half-dusky hue, and grey eyes that seemed to swim in light,

especially when they laughed. There was a great deal of shadow in

the face; it was almost pensive in repose, but it lighted up marvellously

when the grey eyes sparkled and the perfect nostrils quivered, and the

mouth, neither large nor small, but of a gracious sweetness, opened, and

yet hardly showed the pearly teeth.

Esther West came across the common in a cool dress of some

light, shining stuff of silver grey, lightly trimmed with green. The

white feather of her hat rested on the dusky hair. The sunshine

streamed about her. She seemed to "walk in glory and in joy."

Her eyes shone their brightest, as she looked up at the blue above and

down at the wealth of golden blossoms at her feet; her nostrils quivered

as she inhaled the rich, sweet scent of the furze; her lips parted, and

her whole face beamed with its brightest illumination. It was as if

her young soul smiled back the smile of the Creator.

She came up with the flock of geese, who turned tail at her

near approach, and waddled off in their ungainly fashion, and with much

unreasonable cackling. At the pond they collected in a closer group,

stretched their gossiping goose necks, and hissed insanely as she passed—a

feat which she rewarded by a happy little laugh.

At this point she passed into the village, which nowhere

formed what could even by courtesy be called a street. It made

rather a sort of right angle, one side fronting the common, the other the

high road. There was an inn. To the mere onlooker it was a

mystery how it existed, the place was so quiet and retired. But the

sign of "The Maypole" continued to swing in the wind on the grassy edge of

the highway; and its owner did not complain of want of custom. Hurst

was, indeed, more populous than it appeared. There were many little

houses hidden away up green lanes and in among orchards and gardens; for

Hurst supplied the London market with fruit and vegetables, and throve in

its vocation.

It boasted also of a shop—"the shop," which was likewise the

post-office of the district, both concerns being under the management of

Mrs. Moss, though "old Moss," as her husband was called, still overlooked

the transactions by means of a little square pane of glass let into the

wall, through which he surveyed the world from his chimney-corner in the

back parlour, to which he was confined by "rheumatiz" and increasing

years.

Out of the sunshine into that dark, low-browed little shop

went queenly Esther West, radiant and happy, generous, and gracious, and

good. After a cheerful salutation to Mrs. Moss, she produced a

letter. It was for the Australian mail, and there was no need to ask

about it, for each Australian mail bore a similar missive from the

post-office at Hurst to swell the great stream of colonial correspondence.

"There's one a waitin' for you—that is, for your mamma, Miss

Esther. I've hardly had time to look at it yet," said Mrs. Moss,

wiping her hands on her apron, and proceeding to look over a little bundle

of letters. "Joe is just gettin' ready to take the letters round,"

she added (Joe was her son, and did the tailoring of the village up in his

attic, besides his letter-carrying), "but maybe ye may like to carry it

yourself. It's got the Australian post-mark on't." And she

very naively had her look at it before she handed it over to its rightful

owner.

Esther took it, hesitating just a little, and turning her

face, as she inspected the writing, towards a little woman who stood in a

corner, and who had stood back there since Esther entered the shop, with

her sharp eyes fixed on the girl's face, and watching her every movement.

"Yes; I will take it," she said, after the momentary

hesitation; and, with a kindly inquiry for Mr. Moss, she left the little

shop, without having once looked in the direction of the small woman in

the corner, partly out of preoccupation, partly from good breeding.

There is no knowing what will please or what will offend some

people. The little woman in the corner, who appeared to be dressed

in every colour—not in the rainbow—was evidently offended that no notice

had been taken of her; for as soon as Esther was out of hearing, she gave

utterance to her verdict, with a sniff of her sharp nose and a screw of

her shrewish little mouth.

"That's a haughty madam."

"No, she aint!" shouted the old man from his chimney-corner,

causing the little woman to start in an irritable manner. The

parlour door was left slightly open, and Mr. Moss not only saw but heard

all that went on; for, unlike most old people, his hearing was

preternaturally acute.

But Mrs. Wiggett, who was a new-comer, and not aware of this

peculiarity, took no notice of the interruption.

"Who is she?" sharply interrogated the little woman.

"She's an only daughter," replied meek Mrs. Moss.

"She's a beauty!" shouted the old man. "Esther

West—Queen Esther I call her."

"Esther West," repeated Mrs. Wiggett; and taking up the

letter, she read, "'Henry West, Esq.'—that's Harry, isn't it? Is he

any relation?"

"They do say," answered Mrs. Moss, "that he's a cousin of

Miss Esther, and that he's a comin' home to wed her."

"There might be two Wests, but there can't be two Esthers,

and two Harrys, and two Australias," said Mrs. Wiggett, showing herself a

great inductive philosopher, and adding, triumphantly, "I know all about

them."

"Do ye now!" exclaimed Mrs. Moss, with genuine admiration and

curiosity; for not much was known about the Wests in the village, nor did

there appear much to be known about a widow lady of good means and good

manners, who had led a quiet life there for so many years.

Mrs. Moss waited open-mouthed for further information; but it

is doubtful if it would have been vouchsafed but for the interference of

Mr. Moss, who once more lifted up his voice with, "I'm thinking, missus,

ye've little to say about them; and nothing agin them."

Mr. Moss was one of those men who can never help making a

fight for the veriest morsel of opinion, and who was always taking sides

for or against every one who passed in review before the little square

pane through which he contemplated the world. Little as he had seen

of Mrs. Wiggett, he had made up his mind against her. "I'm agin that

goody," he had said to his wife: "she's a little wiper, she is."

His tone of contradictoriness exasperated Mrs. Wiggett, and

she burst out with, "That's all you know; but I come fro' the same place,

and know all about them; and I can tell you"—and her voice rose as her

irritation carried her away— that Miss Esther, as you call her, hasn't any

right to the name o' West, no more nor I have."

A "Ha!—ha!" from the back parlour still further excited Mrs.

Wiggett; while Mrs. Moss exclaimed, credulously, "You don't mean for to

say that Mrs. West isn't an honest woman?"

"I do mean to say that she could be gaoled or transported any

day for stealing of an honest man's child. Esther West is no more

Esther West than I am; she's Esther Potter—Martin Potter's first—first of

ten, and two of them twins; I knew her mother, Mary Potter, as well as I

know I."

"Take care what you say, missis," was growled from the back

parlour; and Mrs. Wiggett's excitement cooled down in a moment.

"You needn't repeat it," she said to Mrs. Moss, in a calmer

tone, as she took up several small packets and departed, bestowing a

deprecatory nod on Mr. Moss through the pane.

Mr. Moss had suffered a defeat, and was silent, ruminating on

the strange communication, which somehow carried the stamp of truth.

Mrs. Moss had lost all presence of mind to ask the ins and outs of the

story, and was speculating wildly. As for Mrs. Wiggett, she went up

the village shaking in her shoes, and wishing she had bitten her tongue

off, rather than have given the reins to that unruly member as she had

done. She had reasons of her own, sufficiently strong ones too, for

wishing to remain incognito.

In the meantime, unconscious Esther, after hesitating another

moment outside the shop door—as if drawn two ways at once—went on in the

direction opposite from home, and towards a house on the other side of the

village called Redhurst, where she was expected to join in a croquet party

that sunny afternoon.

While she was still at some distance from the house, through

the wicket-gate which opened into its shrubbery came Constance Vaughan to

meet her friend. She had on a hat, but neither cloak nor shawl, and

her light dress fluttered as she advanced, with her own eager motion,

rather than with the breeze. The girls met, and kissed each other,

and then paused in the midst of the path.

"I hardly know whether to go back to mamma, or on to your

house," said Esther. "Here is a letter I have just got for her, and

I don't like to keep her waiting for it. I knew you were all waiting

for me, and I came on with the intention of asking you to begin without

me, and going back to her. Will you carry a message for me?

Tell them I shall not be long in going and returning, and explain my

absence. You might take my mallet for a while."

They were eager players, and the delay of the game was quite

a serious affair.

"Couldn't we send a servant over with the letter?" said

Constance.

"It's from cousin Harry," said Esther; which seemed quite

sufficient to make it understood that it was too sacred to admit of its

being entrusted to a servant's hands.

"Let's both go together," said eager Constance. "It is

not far to 'The Cedars,' and they are sure to begin without us."

The girls stood where through the trees, and over the sloping

shrubbery, they could be seen by the group assembled on the elevated lawn

of Redhurst, and Constance insisted on making some telegraphic signals, by

holding up the letter, and pointing in the direction of "The Cedars."

The trees which gave their name to the house, could be seen from where

they stood, stretching their dark, level boughs on the golden sky, the

very symbols of rooted calm. The signals were quite intelligible and

satisfactory to herself, and utterly incomprehensible to those to whom

they were addressed; but a white handkerchief waved in reply was taken for

a signal of comprehension; upon which they turned back deliberately,

Constance linking her arm in Esther's, and fluttering gaily by her side.

CHAPTER II.

A LIFE'S HISTORY.

WHILE they are thus on their way, it may be as well

to anticipate any further revelation through the medium of village gossip,

and tell the story of Mrs. West's life in a clearer way—a story which, but

for one great false step, might have been recorded in fewer words than

most.

She was an orphan, remembering neither father nor mother, and

married in early life to a manufacturer in the north of England. A

woman who must have been made timid by the repression of natural affection

in childhood and youth, for it was not in her husband's home that she

learnt to distrust her power to win and retain the love of others.

Her husband idolised her, childless wife as she was. She had more

than the ordinary share of intellect, but her affections were stronger

still, quite preponderating over the powers of her mind. Her

tenderness was of the kind which even borders on pain in its intensity.

After many years of married life, there came to her the promise of a

child, and, even by anticipation, the love of the mother sprang up in her

heart, with all the power of loving which characterised her.

Close to the gate of the grounds which separated her large

and lonely house from the outer world, stood a pretty cottage, the home of

a recently-married pair, which she had often looked at wistfully as she

saw the young mother fondle her first-born. When the little thing

began to totter about in the porch, or on the small grass-plot in front of

the house, the lady would stop to speak to the child and its mother over

the low garden gate. But now she lingered longer, and almost

trembled with joy to hold the yearling in her arms; and, seeing her daily,

the little mouth was held up freely for kisses, and a very lovely little

mouth it was.

The mother of this child had been the village schoolmistress,

and, herself remarkably handsome, had married the handsomest man in the

parish, though he was only a bricklayer. Neighbours said she might

have looked higher, their shades of high and low being of the finest; but

Martin Potter was intelligent and ambitious, and they changed their

opinion in time. He was a student in his way, and a saver, and when

he married he became a small master, and, with his wife still mistress of

the school, they seemed prospering exceedingly. Then came the baby,

and the mother's health failed for a time, and the school had to be given

up, and the schoolhouse with it. But Martin built a pretty cottage

for his wife and child, and worked harder for them, and seemed to love

them more than ever.

A great disappointment awaited Mrs. West: her baby was only

born to die. The little pale blossom fell from the tree of life

fruitless, unexpanded. Very slowly the childless mother came back to

life and health. When she began once more to pass the gate of her

domain, there was little Esther, lovelier than ever, playing in the porch,

and her (in Mrs. West's eyes) most happy mother with one infant in her lap

and another in a wicker cradle at her feet: Mr. Potter had been presented

with twin daughters.

At first Mrs. West had to be driven past her humble

neighbour's door, with bent head, and clasped hands, and heart aching

heavily. She could not have trusted herself to speak; though she

blamed herself for every throb of what seemed so like envy, and doubled

her pain by being pained because of it. But at length she had the

courage to stop her pony-carriage, and step into the cottage; and, with

tears falling into the bosom of the little white bundle in her lap, pour

out her sorrow to a sympathising listener. Mary Potter was beginning

to have her troubles too, and expressed a very sincere wish, concerning

the twins, that one of them had been Mrs. West's instead of her own.

"Not that I would like to part with one now," she corrected; "but Martin

thinks it hard to have two at a time. He thinks he'll never get on

at this rate." Thus poor Mary bared her secret hurt.

After that, Mrs. West would stop at the cottage door, and

take little Esther up for a drive. And from that she got to having

her at the house, where she was made much of, amused, and, what is even

pleasanter to a very young child, instructed; the instruction being

confined, however, to the simple use of words. She was not two years

old; and the twins had left no room for her in the mother's arms—had "put

her little nose out of joint," to use the common phrase; therefore it was

no wonder that she clung more and more to the gentle lady, who gave her a

mother's care, and all the love that she was ready to have lavished on her

own. More and more the unconscious little one was weaned from her

mother and her home; till one day, Martin Potter being employed on some

repairs at "The House," Mrs. West made him a proposal to keep the child

altogether, and to bring it up in her own home. "You are likely to

have a large family"—Martin Potter thought it more than likely—"and you

would never miss her; while she would be amply provided for. I have

consulted my husband, and I want you to consult your wife before you

answer me."

"Oh, Martin! it is hard to part with our own flesh and blood

to a stranger, even if she were an angel from heaven," pleaded poor Mary,

hugging her twins.

Her husband briefly pointed out the advantages to the child

herself, and to the whole family. Mr. and Mrs. West might die.

They were neither young nor strong, and they would certainly leave a

fortune to their adopted child.

But the more advantageous it seemed, the more it seemed to

the mother to separate her from her child. She was weak and

irritable, and not inclined to be reasonable about it. "She's our

first," she sobbed; "and you've never taken to the twins as you took to

her." She appealed to the father's joy in his first-born. The

first and strongest link between them seemed about to be broken; but when

Mary Potter found that nothing prevailed against her husband's resolution,

she calmed herself, and said, "Take your own way, Martin; but, mind, it's

against my will."

"Take your own way!" Sad and fatal words for either

husband or wife to utter; the way that leads to many a dreary separation.

Those whom God hath joined together have no longer right to a way of their

own. Slowly but surely, Mary and Martin Potter diverged from that

day. There had come

|

"The little rift within the lute,

Which by-and-by shall make the music mute,

And, ever widening, slowly silence all."

|

Mary had a little soreness against Mrs. West, but that in

time wore away, while the soreness against her husband increased.

Mrs. West was very good to Mary, especially when another baby came; she

was good in a way which would have won harder hearts than this young

mother's. It was a deprecating way she had. Anybody might have

patronised Mrs. West, but she could not have patronised the poorest or

feeblest. It was delicate, too. She did not present her humble

friend with stout flannel petticoats or serviceable gowns; all her

presents were such as one lady might give to another. She worked for

the twins, with her own delicate fingers, dresses of simple material, but

dainty form and ornament, such as she would have had her own child wear,

and such as she provided for little Esther; and she contrived, above all,

that the mother should see her child every day, except when she was taken

away for a few months at a time when they went to the sea for the benefit

of Mr. West's health.

They took little Esther away, and they brought her back again

more beautiful and blooming than ever, while the twins were weak, and

fretful, and ailing.

Another daughter had been added to Martin Potter, who felt

more aggrieved than ever at the Providence which assigned him the

encumbrance of four of the weaker sex. Indeed, he could hardly be

got to look upon the face of his fourth daughter. Esther seemed,

therefore, wholly given up to her adopted parents; indeed, such had been

the compact between them and Martin Potter, with the proviso that he

should see her from time to time, and that he might claim her again if he

chose.

Another winter drew near, and Mr. West was ordered to the

south before it should set in. Mary Potter, expecting another baby,

bade good-bye to little Esther without much concern, while Martin, keeping

still better to his bargain, hardly noticed the child at all; but then he

had borrowed money from Mr. West lately, who had said to his wife on the

occasion, "My darling, I fear that man will be a trouble to us some day."

They stayed throughout the winter and the long, cold spring

at Ventnor; but before the latter season was over Mr. West was too ill to

be moved. Periodically Mrs. West wrote to the Potters concerning

their child, and received at equal intervals a letter from Mary.

Number five had turned out a boy; "but," wrote poor Mary, "nothing will

please him (her husband), for the business seems going wrong." And

Mrs. West sent the boy a handsome sum of money as a gift from his sister

Esther, in answer to the intimation.

Just before the summer, Mr. West died, leaving all that he

possessed to his wife, and after his wife to the son of an only brother in

Australia. The will had been made, according to their mutual wish,

years before the adoption of Esther, and had remained unaltered.

"You will take care of the little one," the dying man had said, for he had

come to be as fond of Esther as his wife was. I fear you will find

it a hard task to keep her, and I don't quite like Martin Potter, but it

would be cruel to give her up now."

Give her up! Mrs. West would have given up most things

in this life—after her husband's death, life itself—rather than have given

up the clasp of those chubby arms, the kiss of those pretty lips, the love

of that warm little heart.

Then came the great temptation to which she yielded.

The Potters left the place where they had lived so many years for a

neighbouring town, where small building speculations were rife. Mrs.

West sold her house and furniture through an agent, and thus broke the tie

with it at the same time. Still she remained at Ventnor, but poor

Mary grew remiss in writing, and after a longer interval than usual, the

fatal step was taken—fatal, at least, to the peace of poor Mrs. West.

She removed from the Isle of Wight, and came into the neighbourhood of

London, without communicating to the Potters her change of address.

Her late husband's nephew and heir had been sent to England for education,

and she gave to herself the reason that she desired to make a home for him

during his stay. By this, also, she accounted to herself for her

frequent changes of residence. She was always finding out a better

school for Harry. After three years, the young Australian was

recalled, having spent a year at three different schools. He was a

bright, handsome, fair-haired, restless boy, and, to do Mrs. West justice,

the frequent changes were as much his fault as hers. He needed a

discipline far firmer than any she could enforce to repress his erratic

tendencies; but he learnt so rapidly and retentively, that what would have

hindered the progress of most lads only seemed to favour his, and

everybody seemed satisfied with the result. Little Esther was

Harry's playfellow, or rather plaything, during those years. He

alternately loved her and broke her child-heart by his neglect; but then

he was her senior by six years, and it was not to be expected that a boy

could make a companion of a mere baby of a girl. So the only

memories cherished of Harry by Mrs. West and Esther were pleasant and

happy ones.

Finally, Mrs. West—all trace of the Potters lost—had settled

at Hurst, and Esther had grown up, knowing nothing of her origin, and

loving her whom she called mother with an undivided love. Her memory

carried her back to Harry, and to many a little incident of his stay with

them, and especially to the day of his departure. It had been a

tradition of her childish days that he was to come back and marry her when

he grew a man; and though it was a long time since any one had reminded

her of it, she still remembered the promise and the day when it was made:

the great ship, and being lifted down into a little boat, and stretching

out her arms towards Harry, standing waving his cap round his sunny head,

and laughing at her tears and terrors.

She might have remembered things still further back, even so

far back as her parting with her mother, but the memory is capricious in

respect of events which occur before one is five years old. It

retains only the merest fragments, and if these are broken off completely

from the after series of events and actors, they are speedily effaced.

The completeness of her success in the appropriation of

Esther, had cut off Mrs. West from any retreat from her false position.

If the child had remembered anything, something might have been explained,

and a truer position assumed; but how tell the loving and trusting girl

that she had no claim to her love and trust! It was too late! often

repeated words of saddest significance, "Too late!"

Mrs. West's hope lay in Harry. She, too, remembered his

boyish promise, and counted eagerly on its fulfilment. When he came

back—and he was coming soon—she would set all right. In giving up

the love, for whose sake she had sinned, she would unburden her soul of

the secret under which it had so long lain trembling. Everything was

left till Harry came; then Esther's future would be secure; then she would

seek out the Potters, and make amends for the past. And at length

the time for all these things was at hand.

CHAPTER III.

THE GAME BEGINS.

"THERE they are at last," said Kate Vaughan to her

sister Millicent, as Esther and Constance again came in sight.

They had not begun their game, as Constance anticipated, but

had sat there waiting for the truants, and speculating on the cause of

their absence. The many-coloured mallets and balls lay on the grass

at their feet. The gentlemen—namely, their father and their father's

friend—had strolled to the top of the garden, and were engaged in

discussing some topic of the day; and the young ladies were not a little

impatient of the delay which had occurred.

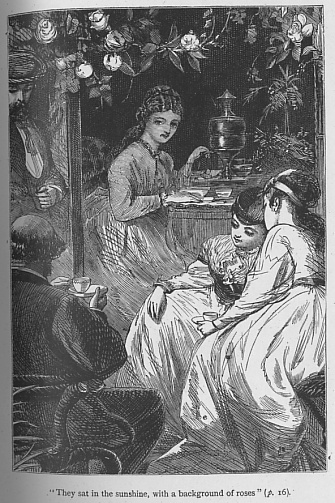

They sat in the sunshine, with a background of roses, which

clustered all over the front of the house. There were roses single

and in pairs—roses by threes and fours and half-dozens on a single spray,

laying their heads together like girlish gossips. And the sisters did not

lose a whit by that background of bloom. They were themselves as

blooming as the flowers; indeed, they had been named in the neighbourhood

the Redhurst Roses. The three sisters were perfect marvels of

youthful beauty; the beauty which consists in freshness, and bloom, and

all the gloss and glow of health. Their light summer costume was as

fresh and fair as themselves; and as they sat there, ready for their

favourite game, in their gay little hats and coquettish boots, they looked

like pretty birds who had plumed themselves from pure love of daintiness.

Yet they were dainty with a difference. The sisters, in

outward appearance so like—so like in their colouring and in the softness

and fairness of youth—were in reality very unlike in character. The

unlikeness was, as yet, only slightly indicated in the outward appearance;

still it was there already apparent, and in process of development.

The hats, with their white feathers tipped with blue, were all alike; but

they were worn with a difference: Kate's with a slightly imperious air;

Milly's with a sweet humility; and Connie's with a careless, roguish

grace. Kate would wear a brooch where her sisters wore only a

ribbon. Kate would also choose her colours a shade brighter, and lay

on more of them, than the others; so that now, bright, hard blue

predominated in her attire over Milly's greys, just lighted up by the same

hue. Milly's dress also flowed round her in softer folds; and

Connie's had the misfortune to soil and spoil the soonest.

Kate's hair had a golden ripple in it. Her lips were

the reddest, and her eyes the brightest of the trio. She was also

slightly inclined to embonpoint, dimples forming in the corner, of her

mouth, and softening the outline of a firm proud chin. Milly was

altogether paler and fairer, with more delicate features, and a more

slender frame. Her greatest beauty lay in a pair of lovely blue

eyes, which it was no exaggeration to call heavenly. They suggested

saintliness; and there was, in truth, a deep strain of tender, religious

feeling in the nature of Millicent Vaughan, which corresponded to the

outward expression.

As for Constance, she was less ethereal than Milly, and less

luxuriant than Kate. She threatened to be rather large and bony,

both in face and figure, and she had no scruple about tanning her bright

skin in the sun. It was a graver face than either of her sisters,

though it seldom looked serious. There was humour lurking in the eye

and in the corners of the somewhat large mouth, a something of sweetness

which Kate's dimples and Milly's serene smiles failed to yield.

But the individual characteristics of the girls were as yet

overlaid with the softness and the bloom of youth, and of youthful

happiness. They were, indeed, very happy. It seemed as if they

had grown in that garden, enclosed and defended from every blast of ill.

Nothing bad ever came to stunt or to blight these richest growths of

nature. Yet they had been out in the world. They had lost

their mother early, and had all been sent to school, while their father

lived a bachelor life in London. But as soon as it was possible he

had had his girls home, and installed the eldest as housekeeper at

Redhurst. At home they had greater freedom than most girls of their

age, and a wider culture. Their father, a literary man of high

standing and of small independent fortune, made friends and companions of

his daughters. They read with and for him. Each had her own

opinions about books and things. Each had also her own ideal of

life.

The young housekeeper's ideal was a fine house and good

society, with all their adjuncts of luxurious living—a brilliant and

bountiful life, which would help to develop her into a brilliant and

bountiful woman, if only it could be attained without any hardening

process—for Kate was capable of hardening. It was a mystery where

she got some of her worldly notions, for the home atmosphere was

thoroughly unworldly; Milly's ideal, for instance, being the life of a

hardworking curate's sympathising helpmate.

Between two elms, which stood at the foot of the garden, and

made the landscape look like a picture in a frame, the girls, as they sat

in front of the house, could see a wide stretch of thoroughly English

country beyond the bright, breezy common, bounded by its sandy wooded

hills. Esther and Constance came on in quite a leisurely fashion.

"I can't think what those girls get to talk about. Only see how they

creep along, arm in arm. I do wish they would make haste."

There was an almost vexed impatience in Kate's tone as she

said this. Then she sighed, and through the singing of the birds she

was answered by a great sigh that swept through the hearts of the

elm-trees. The girl was sighing to begin her game, and there was

something in her impatience which signified that of the young heart weary

of uneventful living, and longing to go forth and meet with mortal fate.

Kate sighed, and rose and went toward her father and his friend to call

them to their posts on the lawn.

Mr. Vaughan was a literary man; not of the fast and loose

kind generally to be found figuring in modern novels. He was a man

of good education, of high honour, and of pure life; all, in fact, that a

man should be who presumes to teach the truth—be it the truth of science

or of life—to his fellow-men. He was open-minded and open-hearted;

and who shall say how many a man in his profession fails for want of the

latter, who has no lack of the former; whose clearest insight is at fault

for want of a little of that charity which never faileth? His fine

and subtle mind, unlike most of the finest minds of his contemporaries,

was unsceptical in its tendency. His difficulty would have been not

to believe, could it have been possible for him to be convinced of the

intellectual necessity for non-belief. His difficulty, believing as

he did, being as he was a Christian man, in all manliness, was not that he

could not believe more, but that he could not believe less. His

friend, Herbert Walton there, called him an optimist; and would fain have

convinced him that things were not even so good as they seemed, and very

far indeed from being better, as he believed.

"Yours is a delightful philosophy, Vaughan," his friend would

say; "but with rampant folly everywhere triumphant—to say nothing of

wickedness—I can't see how a man like you can hold on to it. Your

cheerfulness is simply unreasonable. It sometimes strikes me as

positively insane."

"It is quite true that I do not see wisdom and goodness

everywhere triumphant," Mr. Vaughan would reply; "but I see in everything

the intention that they should. You will own the inherent weakness

of folly, the inherent misery of sin. All I have to do is to see

that I range myself on the side of that intention, and strive to carry it

out to the best of my ability."

At which Herbert Walton would shake his head, proclaim the

forts of folly invincible; but own that, if they were ever taken, those

who came after would find his friend's body by the wall.

Mr. Walton was a journalist, and spent most days of his life

in a dingy London office, working conscientiously in his vocation.

He went into society as part of his work; his recreation was generally

solitude. Unlike Mr. Vaughan, he was apt to take the gloomiest

possible view of things. Whenever it became evident, from the tone

of his writing, that he had become more than usually savage in his mood,

Mr. Vaughan arrived at his office on Saturday afternoon, and carried him

off for the next two days to Redhurst; and the public benefited greatly,

as well as Mr. Walton, the result being a series of more cheerful and more

digestible articles for a week to come.

This friend of their father's was a great favourite with the

girls. They read up all that he wrote, and were ready to come down

upon him whenever he broached any particularly dismal theory. He

brought them news of the great world, even to the last new style of

hairdressing at his last fashionable party. "The Watch-dog" was the

name he went by among themselves; and personally he had a great

resemblance to one of those trustworthy animals, being dark, and

thick-locked, and strong-browed, with a pair of mournful, kindly eyes,

that had often a wistful look in them, in spite of their angry fires.

The girls had taught Mr. Walton the game of croquet, and very

proud they were of his proficiency, and of the general docility which he

displayed. He was always ready, for instance, to take for partner

the young lady assigned to him, and to do her bidding by coming up to her

assistance when sent by adverse fate to the furthest confines of the

ground. But to-day, when he had followed Kate to where Milly was

seated, he proposed himself on her side.

"But we are the worst players of the lot," said Milly; "both

on one side, we shall be sure to lose the game."

"I don't like to be too sanguine," he answered; "but I mean

to win if possible."

There was a wistful look in the dark eyes as he said this,

which Milly did not notice.

Only Kate laughed, and said, "You are growing quite

independent, Mr. Walton."

"I hope Constance will give up Esther to us, then," said

Milly. "We can't have you, papa. You, and Kate, and Constance

are more than a match for us, for Connie plays well when she pleases."

Thus it was arranged just as Esther and Constance came up

together.

"What have you two been about?" said Kate.

"Didn't you understand my signals?" Constance replied.

"Not in the least," said Kate; we only saw that you turned

back with Esther, and that you had something in your hand."

"It was a letter for mamma," explained Esther. "I got

it at the post-office, and was coming on to ask leave of absence to take

it to her when I met Constance. We hoped you would begin without

us."

At last the game began in earnest, for the afternoon was

already somewhat advanced. The shadows of the elms were lengthening

eastward on the grass. For the next hour or two there was much

running, and laughing, and prompting, and very little conversation.

Only it had gradually passed from one to another of the little circle,

till all were aware of the fact, that Esther's Australian cousin was

coming home by the next mail.

CHAPTER IV.

OUT OF THE GAME.

IT was a well-contested game. There were many

skilful moves on both sides; many a ball neared its goal only to be sent

to the furthest corner of the field by an expert enemy; or, even at the

winning post, found it necessary to go back in order to bring up lagging

friends.

"It is easy for one to go on alone," said Mr. Walton, who had

been unexpectedly successful; "bringing up others is the hindrance."

And back he went to bring up Esther and Milly, who had fallen

into the hands of their enemies.

"It's very ungrateful of you to complain," said Kate.

"Think of the number of times I have had to bring you up."

"Ah, that's only human nature!" said the cynic, who seemed,

however, to be enjoying his work.

"Besides, it would be no use winning alone," said Milly;

"that is, you could not win alone, but only put yourself out of the game."

"What I would be tempted to do in most cases," he replied.

"Ah, Walton, that's it," said Mr. Vaughan; "those who would

win the race of culture alone, leaving half the world behind them, will

find that they have not won after all—have only put themselves out of the

game; or else they will have to go back and bring up their fellows; they

will have to go generations back, if need be. It's one of the

conditions of the game of life, that we can't win alone."

But this time Mr. Walton was on the winning side: he, and

Esther, and Milly got the game. When it was over, the party

scattered into groups. Kate stepped through the open window of the

drawing-room to dispense the afternoon tea, which was laid there; and Mr.

Vaughan went up to Milly, and drew her away from the rest with a look of

unusual tenderness—insomuch that she looked at him questioningly, and

said, "Is anything the matter, papa?"

Nothing was the matter. Garden chairs were found for

the whole party, who seated themselves forthwith, while Kate and Constance

handed cups of tea out of the window.

Then they began to talk of the Australian, and to club

together the scattered information they had obtained from Esther

concerning him, while they were playing.

"He is rich," cried Kate, from the tea-table. Mr.

Walton laughed.

"And young," said Milly, innocently. A remark which,

somehow or other, quenched the light on the dark face beside her.

"And handsome," said Constance, in playful mockery.

"And you are all ready to fall in love with him," said Mr.

Walton, "for all these qualities in combination."

Thus they chatted on, as if life were a summer holiday; and

the shadows of the elms lengthened on the grass, and the western sky began

to glow. Then Kate declared that Mr. Walton had had six cups of tea,

and should have no more on any pretext whatever; and Esther hastened to

say good-bye to her friends, that she might be home in time for dinner,

for which the others dispersed to dress.

Esther took her way homewards in the evening glow, with its

strange, transfiguring light shining on her face, and bringing out its

latent pensiveness; and she was aglow from her innocent enjoyment, aglow

with the gladness of the present, and the bright anticipation of the

future. The great event of the day, the announcement of her cousin's

return, was still in her mind, had been in her mind all the afternoon, and

was perhaps the cause of those gleaming eyes and that pensive mouth.

To deep and thoughtful natures all great joy is serious.

The greatest joy has something of awe in it. And this was a great

joy. Not that Esther looked upon her cousin in the light of a lover.

Mrs. West was too delicate a woman to have presented him to the girl in

that light; but he was her hero. She remembered the bright,

handsome, impulsive boy, and pictured him perfect in his manhood.

His letters were so frank, so vivid, so full of life, so unlike all that

she saw or knew of the lives of men, so much more manly, that he seemed to

her the very man of men! How noble he was in his simplicity, beside

some of the literary men she had encountered at Mr. Vaughan's; the sulky

young poet, who had taken her down to dinner, and had never once spoken to

her, being entirely occupied with his great grievance, an adverse review

in the Athenæum; or the enthusiastic one,

who had effectually prevented her from getting any dinner at all by

speaking the whole time, and leaning the while with his spectacled nose

right over her plate; or the young man of the period, sublimely

indifferent to everything in the universe except himself. What a

real life it seemed to her, riding over those wide western runs, driving

home the herds of wild cattle, counting by thousands, and tens of

thousands, more life-like, and better worth living than the lives of any

of the men she knew. Thus had her young imagination been impressed

with pictures of a patriarchal life, and in the centre of the pictures

there figured a kind of shepherd-king in the shape of Harry West.

Just then, as if to reproach her with her sweeping

depreciation of his sex, there rode up a young man of elegant figure and

thoughtful face, who reined in by her side, and saluted her with a respect

which had in it a touch of chivalrous devotion. She returned his

salutation frankly, and he walked his horse by her side for the few paces

which would bring her to the entrance of "The Cedars." She walked

with her eyes cast down, not from him, but from the light that fronted

them, so that he was free for those moments to peruse her face, an

opportunity of which he availed himself with ardour. At the gate she

looked up, and bade him good-bye. His admiring glance was restrained

in a moment. She had not seen it; nevertheless, she made a

reservation in favour of her neighbour, Benjamin Carrington, when she

passed sentence on the young men of her acquaintance.

Esther found her mother—for so, for the present, we may call

her just as she had left her, seated in her favourite window, looking out

among the cedars, her letter still in her lap.

"Mamma, darling, you look as if you had never moved out of

the spot," said Esther, gaily.

"And I do not know that I have," she answered, still letting

her eyes rest on the level boughs, and the lake of molten gold which

seemed to swim behind them. She used to say they stretched out their

arms to her, as if to bless her with their peace. Alas! it was long

since the gentle heart had known peace. All the difficulties in

which she had involved herself were present to her mind. She had

poisoned for herself the fountain of her happiness, as, in one way or

other, so many of us do ; and the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, the

pure and peaceful Spirit of God, could not come unto her, because she had

no will to put the evil thing away.

"I am so glad Harry is coming," she said at last, looking

up at Esther.

"I shall be quite jealous of Harry," said Esther, jestingly.

"It is not that you are not enough for me," she answered,

hastily and nervously. "My own!—my own!" she almost sobbed as the

girl knelt at her feet. "If you and Harry should love each other, my

heart would be at peace."

She had never said anything like that before; and she said it

now because she was overwrought by the emotion of the last lonely hours.

There was silence in the room after the words had been said;

the silence of a reverie which neither seemed to care to break.

Strangely enough, that very afternoon Mrs. West had thought

of Mrs. Wiggett, of whose neighbourhood she was quite unaware. Not,

however, by her present name had she remembered that little woman, who had

a hidden history of her own, which might have remained hidden too, but for

that fatality which comes upon some people who live themselves in very

crystal palaces, in the shape of an uncontrollable mania for throwing

stones.

The weight always pressing on Mrs. West's spirit had been

heavier than usual that afternoon. In vain she had tried to banish

it; to forget its very existence; to say to herself, All is, and shall be

well. It was there; it would not be banished: it boded, or seemed to

bode, some coming ill. It was as if the very air bore to the

sensitive soul the slightest tremor of approaching fate. A dread of

some unknown impending evil, which might pass her by if she could only

cease to dread. As if Fate were a piercing eye, which she might

elude if only she had the strength to resist the fascination of looking

that way! To such a height had the miserable feeling risen, that

Esther's unexpected return with the letter was almost more than she could

bear; and her heart still beat with sickening faintness as Esther knelt on

at her feet in silence.

It was Esther who broke the silence at last. "I feel as

if I could never love any one as I love you, mamma," she said, kissing the

fair thin hand.

"Do you think you would love me as well if I were not your

mother? if—if I were some one else?" said Mrs. West, bending over the girl

with an almost agonising look.

"What a strange question, mamma!"

"Esther——"

The name sounded faint and far away, as if it had been

uttered by the last breath of a departing spirit. What might have

followed remained unspoken; for the fragile speaker lay back in her chair,

and quietly fainted away.

There was no painful fuss and flutter over the fainting form.

Esther rang the bell for her mother's maid, and stood holding fast the

frail hand, while some simple restoratives were used. The first sign

of returning consciousness was the pressure of the thin fingers. She

seemed to keep hold on life by that firm young hand which held hers in its

anxious clasp.

Mrs. West, after lying down for a little while, appeared at

dinner as usual; and Esther and she spent their evening together in light

work or reading; Esther instinctively keeping aloof from any topic that

might excite her companion.

But there was a vague trouble in her heart; and when her

mother had retired, as she did at an early hour, she carried the lamp into

a little room beyond, and sat looking out upon the cedars, with the cool

night air fanning her forehead, and the silver sickle of the new moon

hanging over the dark, solemn trees.

That same silver sickle hung over the garden at Redhurst, and

witnessed a new birth there—the birth of love. All the stars came

out and gazed and trembled over it, and the flowers sent up their sweetest

odours, as if breathing the secret to the stars. The thing was so

new, so sweet, so strange, so sudden, nobody could tell exactly how it

came to pass, not even Millicent herself, who was the subject and the

object of it, except that she devoutly believed in its heavenly origin,

and took it as sent from God.

As far as can be told, this is how it came about: Herbert

Walton, during those summer days, had drawn very near to Milly, and had

drawn the unconscious girl very near to him. On the evening after

the game he sat next her at dinner, and contrived to surround her with a

kind of isolation, as if there had been none there but he and she alone.

Neither could have told the precise moment when heart answered heart under

the mysterious spell which it needs no words to weave. Only when the

ladies left the room, Milly, the serene and mild, had grown shy,

conscious, and blushing under the gaze of half-triumphant love.

Then, when her sisters had settled themselves to read, she took a book in

her hand, and wrapping a light shawl about her pretty figure, stole out

into the garden. But she was not long alone. She was followed

to the leafy nook she had chosen, and caught like a timid bird. And

Herbert spoke of himself and of his aspirations, and how often they were

chilled and quenched in the world, needing just such inspirations as she

could give. And the girl who, as a child, had known, and loved, and

looked up to him, thrilled through and through with wonder and with

tenderness, and the familiar home-garden changed in the starlight into

that Eden which still awaits on innocent and happy love. With every

pure sense drinking in the enchantment of the hour, Milly and her lover

lingered beneath the stars, and she listened to the fond reiteration of a

passion which had suddenly transformed her life, till her fair head sank

upon her lover's shoulder, and she trembled into happy tears.

"Papa has gone into the library alone," said Constance,

returning from a search for a book she wanted. "Have you noticed,

Kate, in what an extraordinary manner the Watchdog has been prowling about

this time? I declare, there he is at the top of the garden, and

Milly with him! I can see by her white dress. They look

exactly like a pair of lovers."

"I wish, Constance," said Kate, "that you would not speak

such nonsense."

But the younger sister's quick sympathy was roused, and in

spite of the repulse, she went up to Kate and whispered, "Oh, Kate, I am

sure it is so—dear, dear Milly!" Then the two laid aside their

books, and waited with a tender trouble in their hearts.

But Milly was too shy to enter the now lighted room where her

sisters sat. "Your father knows it already, my love." This

assurance had comforted her concerning him. While they lingered, the

bell rang for prayers, and Milly and Herbert stole, side by side, into the

dimly-lighted library, without word or comment, seeing they met for a

sacred purpose. Side by side they took their places in the family

circle, and their first act was kneeling together and mingling their

voices in the universal prayer, an act in which the heart of the slightly

world-worn man became as the heart of a little child. And somehow it

became known to all the household that Milly and Mr. Walton were engaged.

And when Milly went to the room, it was Constance who

followed her, and held her in her arms, and heard the shy confession, of

her happiness, and filled up the great need the heart has of being

rejoiced with in its joy—a need far keener and deeper in most hearts than

that of being wept with in sorrow, but one to which only the most tender

and generous natures respond.

"Child," said Milly, looking in her sister's face, "I seem

only to-night to have found out your love as well as his. And where

is Katie?"

Kate was with her father in the library, alone with him, and

giving him more pain than he could well account for.

"I thought Mr. Walton had been too poor to marry?" she had

remarked.

And her father had answered, "Well, he is not very rich,

Katie; but he is one of the ablest men I know, and high-principled, too,

as well as able. I think Milly ought to be proud of his preference."

"And where are they to live?" asked Kate, in the same hard

tone.

"In a cottage as near us as possible; somewhere that will

allow Herbert to go in and out daily."

"I think Milly has thrown herself away," said Kate.

"What do you mean by such a speech as that, Katie? You

do not mean that loving Herbert—as she must have done, or why should she

have accepted him?—she should have held herself back for a higher bidder.

I cannot imagine a happier lot than has fallen to Milly. Oh, my

child, do not give me cause to fear that you are less worthy of such

another."

And at this little speech, tender as was its tone, Kate had

felt herself aggrieved, and had retired to her room with considerable

heart-burning. She was vexed with Milly, who had been quick to

perceive her want of sympathy, vexed with her father, and vexed with

herself. Her heart was troubled and stirred to its depth for the

first time, and she felt something very like vexation that Milly should be

what she considered out of the game—settled down as a poor man's wife.

CHAPTER V.

TIMOTHY WIGGETT.

WHEN Mrs. Moss joined her husband in the back

parlour, after the departure of Mrs. Wiggett, she looked the very picture

of gratified curiosity as she exclaimed, "Well, did you ever hear the

likes o' that now?" The defeated Moss gave a prolonged growl, which

ended in the articulate words, "No, an' if ever I hears you repeatin' a

word o' what that little wiper has said, it'll make me go nigh to layin'

my stick across your back, missis!"

Mrs. Moss thought it very hard: and what harm had she done,

to be spoken to in that way? It was hard that she was not to be

allowed the benefit of priority of information. Her extensive

experience in matters of village gossip led her to believe that priority

was all she had obtained, and that the news would be over the whole place

before the week was out.

But Mrs. Moss's experience was destined to fail her on this

point. For the present, Mrs. West's secret depended on the ability

of Mrs. Moss to hold her tongue, an ability which was certainly little to

be trusted, except under the influence of that keen supervision kept up

through the square pane and open door of the back-parlour. Even if

the door had been shut, Mrs. Moss durst not venture on forbidden gossip

under the master's eye. He would have seen her speaking, and have "knowed"

all about it directly. So the worthy gossip comforted herself with

the thought that she would at least have the satisfaction, when the story

came round to her again, of saying she knew it ever so long ago.

Meantime, Mrs. Wiggett had gone home and confided her

discovery to her lord and master, and the result had been a warning not to

burn her fingers with other people's broth—a warning which might not have

had much effect upon her, but that it coincided in a remarkable way with

certain qualms of her own, in respect of her want of reticence.

Timothy Wiggett was as big and good-natured as his wife was

small and shrewish. Not that Timothy was by any means what is called

in country phrase "a soft"—a man easily put upon; on the contrary, he

could be both firm and shrewd, only his health was so perfect, his juices

so bland, his feelings so comfortable, that he found it impossible to put

himself out of temper. Mr. Wiggett was brown as a berry—a clear,

ruddy brown. He had the clearest of brown eyes, and the nuttiest of

brown hair. Brown, indeed, seemed his favourite colour, for his

coats were brown, too, and he generally wore round his great throat a soft

brown silk handkerchief, such as are used for the pocket, with a border of

yellow. His face was broader than its length, when his hat was on

quite ridiculously so; he had a very broad, thick nose, and a very long

mouth, with a slight droop at the corners, which betokened melancholy, but

quite falsely, as it seemed. His hands were broad and fat, so fat

that his forefinger nearly buried the thick gold ring he wore, with T. W.

engraved on the square signet.

Yes, Timothy Wiggett, market-gardener, was sleek and

well-to-do, and Sally Brown had done well for herself in the long run.

She had risen in the world, since the days when she and Mary Potter had

been companions in one of those girlish friendships which take place

between the most unlike and unlikely people. She had fitted herself

very well with Mary's old shoes, people said; for it was well known that

Tim, the gay young gardener, had loved the gentle Mary—but that was long

ago, and Mary had married, and her disappointed lover had gone away to

push his fortune.

Then Sally, who would have given her eyes for Tim in those

days, married too, a young man who was a fellow-worker with Martin Potter,

who had set his mind upon going out to Australia, but who cared enough for

that quick-witted, smart-tongued, bright-eyed little person, which Sally

then was, to give up what he considered his prospects in life, and settle

down with her in a cottage next door to her father and mother's.

Sally's parents were both old people, and nearly past work. They had

no other child save her, and she stoutly refused to go out to Australia

and leave the old folks at home. She was a good and faithful

daughter, for all her sharp tongue, but she did not make Ned Brown a good

wife. "He hadn't the way with her," that was how the old folk

explained it to themselves. At any rate, he became dissatisfied,

resenting having given up so much and got so little. If she had

brought him a child, it might have made a difference; but she did not, and

Ned began to get sullen. He did not relish having to work for his

old companion Potter, who seemed to be rising in the world. One day,

working on a job of his, they quarrelled, and he came home declaring that

he wished he had gone to Australia. "If you go, you'll go by

yourself," his wife had said. "You know my mind well enough.

You've known it all along. I never would have married you, nor any

other man, to leave father and mother alone, and be banished over the

sea." The result of such speeches was, naturally, keener irritation

and increased resentment, and at length it came to such a pass that Ned

Brown resolved to go alone. He softened as the parting drew near,

and tried to excuse himself by saying, "The best of my days are goin' by,

and I'll lose my only chance. You'll come out to me, Sally, when the

old folks go."

But the old folks were in no hurry to go. They had

their daughter again, and Ned was forgotten. He wrote several times,

and with difficulty, for he was no scholar, as Martin Potter was.

The answers he got were not much to his satisfaction, not likely to keep

the lamp of love burning in his heart, and at length he ceased writing

altogether.

Seven years slipped away, and nothing was heard of Ned Brown.

"Be sure he's dead," said the gossips, attempting to console the forsaken

wife. "An' if he isn't dead, he ought to be," grumbled the old

father. "But my Sally's quit on him, anyhow; for it's the law of

England, that if a man runs away from his wife, and she hears nought on

him for seven years, she's free." The old man did not quote his

authority, but he devoutly believed in this reading of the law—"it only

stood to reason," he said.

At last Sally donned a widow's cap. Ned Brown had died

in exile. The old mother was dead, the old father in his dotage, his

daughter supporting him by the labour of her hands, as village dressmaker.

Just then Timothy Wiggett was on a visit to his native place. He

came, with other stalwart sons from other parts of the country, to bury

his own old father, the patriarch of the village. He had found the

place sadly and sorely changed, all but Sally Brown, on whose bright hard

face the years had made little impression.

It was difficult to say what attracted Timothy to the little

woman. Perhaps it was the fact of her constancy to her parents that

touched him. Perhaps it was her struggle with adverse circumstances.

Perhaps it was the consciousness that she had cared for him in "the old

times" that would never come again. Whatever it was, the prosperous

bachelor was attracted to her, and she became Mrs. Timothy Wiggett, much

to the astonishment of everybody not concerned, who envied the

quick-witted little dressmaker for having accomplished her end at last,

Ned Brown, now "poor Brown," having opportunely taken himself out of the

way.

Timothy made Sally a better husband than his predecessor had

done, and she, in return, made him a much better wife. It was all

the better for her that her spouse was not in love with her in the way her

young husband had been. Such a love is by its very nature exacting;

and though Sally would have suffered any amount of exaction from her

present husband, absorbing love is also sensitive, and she could not, for

her very life, have kept from irritating. As it was, she failed to

irritate Timothy. When she got out of temper, he only soothed and

petted her. His love was too disinterested to find fault. He

had pitied the brave, forlorn creature, and he pitied her still.

She had carried her old father with her to her new home, but

he did not long survive the change. And when the old man was gone,

Sally, in want of some one to rule, as she had been accustomed to rule

him, set to work upon her big, burly husband. But it would not do.

At first, he had played with her usurpations of power, as Gulliver might

have played with a bumptious Liliputian; but he got the better of her

entirely at last. One fair-week he had been out oftener and longer

than usual, meeting the farmers and gardeners of the neighbourhood at the

"Peahen." It was the time when he generally felt bound to be at

home, but just because she had gone beyond bounds in her animadversions

the last time he had stayed, he stayed longer still.

Mrs. Wiggett sat and fretted by her childless hearth, supper

was prepared for Timothy—something savoury which he loved—but she left her

share untouched, and waited on. She sent the sleepy servant off to

bed, and got wilder and wilder as the hours went on and he did not come.

Then her grief rose to anguish—to a kind of tragic passion of love and

fear. She feared all sorts of improbable events taking her Timothy,

her big, generous, manly Timothy, away from her, or taking away his big,

generous, manly heart. Love was throwing its illumination into the

dark and crooked corners of her heart, where she read that she was

unworthy of him. She seemed to see a handwriting on the wall against

her, which seemed to bid her dread that one day her kingdom would be taken

from her. She put out the light, and sat on in the dark. If

ever he came back alive, she wished that he might find her dead in her

misery. She poured out wild, but true prayers, for his safety and

her own sanity.

There he was at last. She knew his subdued knock at the

bolted door. Instead of hastening to open it, she rushed upstairs to

the room above, and opened the window. Yes, there he was, safe, and

sound, and happy, by the tone of his voice, crying, "Why don't you open,

Sally, woman?"

Her anguish had vanished on the instant, and in its stead

this strange creature experienced a fit of ungovernable anger. She

put her head out of the window, and cried, "Is this a time of night for

respectable people to be coming home? You had better go and sleep

where you came from."

"Come, come, Sally, don't go too far," he called out firmly;

but the very instant a flash of humour, if any one could have seen it,

passed over his face, and he added, "Very well, there's the pool; I had

better go and drown myself,"

Her reply could not be heard. The night was cloudy, and

the moon, riding clear every now and then, was quenched in clouds, like a

wave-whelmed barque. The pool, with its group of willows, was only a

stone-cast from the house. Thither strode Timothy, with a great

chopping block that stood near the door, borne in his arms. Just as

Mrs. Wiggett opened the door, there was a tremendous splash. The

clouds closed over the moon, and the waters, to Mrs. Wiggett's distracted

ear, over the body of her husband. "The drink has maddened him," she

thought, "and this is the answer to all my fears;" and she flew to the

edge of the pool, only to see a dark object bobbing up and down in it.

Behind the screen of willows Timothy had stolen back to the

house, a merry thought, born of spiced ale and warm blood, in his head.

He would turn the tables on the little woman, get inside and lock the

door; and ask her if this was a time for respectable people to be abroad.

But he had not reached the house when a despairing cry and another splash

broke the stillness of the night, and with a shout which made the dogs

bark down in the village, Timothy rushed back to the pool, to find that

his wife had thrown herself in, after him as she believed.

Happily, at that moment the moon came out and hung over the

troubled pool, enabling Timothy to lay hold of Sally, and drag her out of

the water, which was of drowning depth in the centre. Her head had

come in contact with the chopping-block, which it had been her aim to

reach, and when dragged out she was quite insensible, and had to be

carried back to the house in her husband's arms. There was a fire in

the kitchen, and Timothy did what he could, sending off the maid for the

village doctor. But a long and severe illness was the result.

The comedy had very nearly turned out a tragedy.

During this illness there had been tender passages between

the husband and wife. Her very smallness called forth the big man's

tenderness. He could carry her about like a baby. Her

complaints went to his heart as the fretful complainings of a child.

He loved her better than before—this creature who seemed so unlikely

either to gain or to keep love: and she did not try to coerce him any

more. She found out that he was easier to lead than to drive, and

because the story of Tim's drowning had got wind in the place as a good

joke, she persuaded him to leave it, and had her own way. He found a

large garden in the neighbourhood of London to lease. It suited him

exactly, gave scope for his enterprise and skill greater than he had yet

enjoyed; and so the Wiggetts had come to settle in Hurst.

CHAPTER VI.

THE OLD LOVE.

IN this June weather Mr. Wiggett had more than

enough to do. He had to be up betimes, superintending his men in

digging and preparing the ground for the later crops of vegetables,

earthing up peas and beans, and making celery ridges, and thinning

turnips, onions, carrots, and beets. At the more delicate operations

he worked with his own hands, thinning his thickly set apricots, keeping

the mildew from his peaches, netting his cherries, pitting his cucumbers,

pegging down his verbenas, and trapping the earwigs on his dahlias.

Over night the great wagons were piled up as high as the

house, with their loads of cabbages, &c., and sent off long before the

peep o' day in charge of an under-gardener and the wagoner, who seemed to

have the faculty of sleeping on his feet. The wagons would fall into

a line in one of the narrow streets approaching the great market; and the

wagoner would sit down on the trams of his cart, and begin to wake up and

exchange salutations, flavoured with bucolic wit, with his mates.

While still in the small hours the master started off, with a fast

trotting horse and a sleepy lad to hold him, in a wagonette, filled with

picked and carefully packed strawberries, or whatever fruit was in season,

for the tables of the luxurious in the most luxurious and most squalid

city of the world.

One morning in the week following Mrs. Wiggett's discovery,

Timothy set off as usual, promising to be home by dinner-time, meaning by

that a little after the hour of noon. But dinner-time came and

passed, and he did not make his appearance. This delay, however, was

evidently not considered a delinquency. The repast, a cold one, was

proceeded with, and a portion laid aside for the master, while the

mistress went about her own particular business, which just then was the

troublesome one of rearing a tribe of turkey poults. The master

never neglected his business, and as every hour of the day was precious at

this season, something in the nature of business must have detained him.

There he was at last, bowling up the uneven grassy lane,

rising in his seat to look over the tall privet hedge, and through the

plum trees into the yard beyond, where his wife was scattering a last

handful of corn to the common fowls, who had had to wait till their more

aristocratic companions had dined on chopped liver and other delicacies.

"You're late, Wiggett," said his wife, waiting his

dismounting at the door.

He assented, more than usually silent; and he was not at any

time a talkative man. It was not till he had sat down to the table

and lifted his knife and fork, that, pausing in the act of helping himself

to a huge angle of meat-pie, he fixed his eyes on his wife and asked,

gravely, "Guess who I met to-day?"

"How should I guess?" she answered, sharply.

"It was somebody you know better than me," he rejoined, in a

tone of mock mystery.

Mrs. Wiggett at once became irritated, almost to the verge of

passion. "You always were fond of tormenting," she burst out,

beginning to flush and tremble with her excitement. "I don't see the

fun of it myself."

"Come, come, Sally, I didn't mean to put you out," said her

husband. "It was Mary Potter."

"Mary?" repeated Mrs. Wiggett, with her eyes fixed on her

husband's mouth, waiting for more.

"Ah, and lookin' but poor, I can tell you, poor, an' toiled

an' moiled, wi such a brood o' young uns as you could scarce count 'em.

I wouldn't have known her, but I saw a white-faced bit of a lass stoop

down among our feet to pick up a daisy that somebody had dropped, when one

o' them big, lumberin' market women came by, and planted her great dirty

splay foot right on the top o't, knocking the little thing clean over.

I thought the woman had trodden on the fingers, and gave her a good shove,

and the little un' cried with fright, for she wasn't hurt. Then a

tall woman came up and stood over her, and said, 'What's the matter,

Mary?' and I know'd the voice was Mary Potter's, and then I know'd the

face was hers too."

"What was she doin' there?" said Mrs. Wiggett, who had not

evinced much delight at the discovery of her old companion.

"She had promised the children a treat for many a month," she

said, "and that was to take them to Covent Garden in the summer.

There were two little chaps carrying a basket between them, and a taller

girl with another little un, a three-year old or so, in her arms.

The little chaps seemed jolly enough, but Mary and the girl seemed

terribly tired."

"And how did she like meetin' you again like that?" asked

Sally, who knew more about Mary than her husband did, though she had lost

sight of her for a year or two.

"I don't know that she liked it at first. She looked

quite white, and staggered like, up against one o' the fruit-stalls."

"Is she stoppin' in London then?" was Mrs. Wiggett's next

question.

"She's been stoppin' there this year or two. I've been

to her place."

There was no further response from Mrs. Wiggett than the

interjection, "Oh!" She was waiting for more still, her husband

meanwhile eating and talking at intervals.

"I was just comin' away, and Mary looked so tired, that I

offered to drive them all home in the wagonette; and the young folk looked

so happy over it, that she didn't like to say no." Mr. Wiggett did

not add that in going to order the wagonette, which he always put up for

an hour or two, he had brought back sundry baskets of his own

strawberries, and a handsome nosegay for the little girl who had tried to

rescue the daisy.

"Well, I thought at first it was a goodish place they lived

at—out a broad road—Belgrave Road they call it, and past the grandest of

houses and the Queen's palace; but it's all outside, London is; beside the

big houses that you see, there are little ones you don't see, stuffed away

behind backs to hide their poverty; and such stuffin'! hardly room to turn

in the places they call back-yards; the very weeds won't grow in them.

In one o' them little houses the Potters live; the yard was full of

Martin's things. Mary keeps a little school, which pays the rent.

And how they all manage to live there, I can't make out. There's

nine beside their two selves, and four o' them girls. But she frets

after the other one yet."

"And you told her?" broke in his wife, eagerly.

"Well, I was very nigh telling her, when Martin comes and

stops me."

"How did he stop you?"

"He looked so sour, I began to think I might make more

mischief than I could mend. The little one danced up to him wi' a

bit flower in her hand, and he looked as if he did not see her. She

shrank away behind our backs, and the two little chaps slipped out as if

they were afraid of him."

In truth, Mary Potter had told him, with bitter tears, that

Martin was not fond of his children. He looked upon them as burdens

tied round his neck, that had dragged him down, and kept him down.

He was a disappointed man, who hardly cared to struggle, since the

struggle could no longer better his position, though it could have

rendered it more comfortable, especially to his wife and children.

Martin Potter had speculated and failed, and speculated

again, till he could do so no longer; not being considered a safe man.

The cause of his failure was not want of ability, but want of capital; and

he could not see that the want of capital incapacitated him from holding

the position of a master. He would build blocks of houses, and he

built them on nothing—a rather insecure foundation, for his fortunes at

least.

Having failed in more ambitious efforts, Potter had become a

jobbing builder; working when he had a job, but not with spirit: for his

spirit was hankering after what he took—miserable delusion!—for higher

things; and strolling about in a discontented fashion when he had nothing