|

――――♦――――

Cooper meets de Quincy

and interviews the sister of Robert Burns.

From The International Monthly Magazine, of

Literature, Science and Art.

Vol. IV, 1851.

THOMAS COOPER, author of the

Purgatory of Suicides, &c., has been on a lecturing tour through Ireland

and Scotland, lately, and has given an account of what he observed, in

several letters to the London Leader. We copy from them a

few paragraphs:

I had two hours delightful conversation

with Mr. de Quincy, at Lasswade, and was as deeply impressed with his

intellectual power in talking, as I was with his writing when, in my

boyhood, I read his “Confessions of an English Opium Eater.”

On my return from visiting Kirk Alloway, and the

cottage of Burns, I called on his remaining sister, Mrs. Begg, a highly

intelligent woman of eighty, who gave me some information of an

important character, as I deem it to be. Her daughter, Isabella,

was present while I had the short conversation with her. I told

her that I entertained strong doubts of the truth of many things which

were said about her illustrious brother, and I wished to have the

benefit of her own personal knowledge respecting him. She replied

that she would have pleasure in giving me all the information in her

power. I told her that a person in Glasgow had declared to me, the

other day, that he believed all the accounts of her brother’s irregular

life; for a friend of his had called on Mrs. Begg lately, and she had

said that she had often seen her brother sit at the table in a morning,

after a night’s debauch, shading his face with his hand, while the big

tears of remorse were dropping on the board before him. Mrs. Begg

seemed moved painfully. “Nothing is more false,” she replied; “I

never had such a conversation; and never could say so, for I never saw

my brother either drunk or showing any such feeling; nor did I ever know

him to be drunk. It is true, I saw but little of him in the latter

part of his life; but his son, who was with him almost constantly, told

me that he never saw his father the worse for liquor but once; and thou

he was sick, but yet perfectly conscious. His son also said, that

though his father would come home late during the latter part of his

life, when they lived in Dumfmies; yet he was always able to examine

bolts and bars, went to observe that the children were right in bed, and

always acted like a sober man. Besides,” added the intelligent old

lady, “how was it possible that my brother could be a drunkard, when he

had so small an income, and yet, a few weeks before his death, owed

nobody a shilling? That speaks for itself.” Mrs. Begg

furthermore confirmed what I also learned in Glasgow from persons

conversant with those who had known every circumstance of the close of

Burns’s life, that Allan Cunningham has sorely misstated many matters.

Burns did not die in the dramatic style which Allan tells of.

Allan was never in Ayrshire in his life; but had his materials from some

old fellow who went about poking into every corner and raking out every

false story about Burns. A writer in Glasgow, in whose company I

sat for a short time in the evening after I had delivered my oration

there on Burns, contradicted Allan Cunningham’s account of Burns’s

death, from personal knowledge—just at the time when Allan’s Life of

Burns appeared; but Allan never took any notice of the pamphlet, and

never corrected the misstatement. Mrs. Begg said that she had seen

the two volumes of the new life of her brother, by Robert Chambers, and

the account was fairer than any she had seen before.

――――♦――――

Manchester Guardian

19 Jan, 1856.

MR. THOMAS COOPER,

author of "The Purgatory of Suicides," and other works, will

LECTURE at the Athenæum on Wednesday evening,

January 23, on the "Life and Genius of Milton," with Recitations

from "Paradise Lost," &c.; and on Thursday evening, January 24, on

the "Life and Genius of Burns," with Recitation of "Tam O'Shanter,"

&c. ― Admission: Reserved seats, 2s. 6d.: back seats, 1s. each;

members, 1s. 6d. and 6d. each. To commence at 7-30p.m. ―

Tickets to be had at Wheeler's newspapers office, Arcade; of Mr.

Burge, bookseller, Princess-street; and of Mr. Casper, tailor and

draper, 83, Market-street: members tickets at the Athenæum only.

――――♦――――

From

'Thomas Carlyle'

Harpers New Monthly Magazine

Volume LXII. (p. 902)

New York, 1881

Thomas Cooper, author of the “Purgatory of Suicides” (dedicated to

Carlyle), like so many others who had suffered for their efforts for

reform, was befriended by Carlyle. “Twice,” says Cooper,

“he put a five-pound note in my hand when I was in difficulties, and

told me, with a grave look of humour, that if I could never pay him

again he would not hang me.” Carlyle gave Cooper more than

money—a copy of Past and Present, and therewith some

excellent advice. The letter is fine, and my reader will be

glad to read it.

“CHELSEA, September 1, 1845.

“DEAR SIR,—I have

received your poem, and will thank you for that kind gift, and for

all the friendly sentiments you entertain toward me — which, as from

an evidently sincere man, whatever we may think of them otherwise,

are surely valuable to a man. I have looked into your poem,

and find indisputable traces of genius in it — a dark Titanic energy

struggling there, for which we hope there will be a clearer daylight

by-and-by. If I might presume to advise, I think I would

recommend you to try your next work in Prose, and as a thing

turning altogether on Facts, not Fictions. Certainly

the music that is very traceable here might serve to irradiate into

harmony far profitabler things than what are commonly called

‘Poems,’ for which, at any rate, the taste in these days seems to be

irrevocably in abeyance. We have too horrible a practical

chaos round us, out of which every man is called by the birth of him

to make a bit of Cosmos: that seems to me the real Poem for a

man — especially at present. I always grudge to see any

portion of a man’s musical talent (which is the real

intellect, the real vitality or life of him) expended on making mere

words rhyme. These things I say to all my poetic friends, for

I am in earnest about them, but get almost nobody to believe me

hitherto. From you I shall get an excuse at any rate, the

purpose of my so speaking being a friendly one toward you.

“I will request you farther to accept this book of mine, and to

appropriate what you can of it. ‘Life is a serious thing,’ as

Schilier says, and as you yourself practically know. These are

the words of a serious man about it; they will not altogether be

without meaning for you."

Those who have read the “Purgatory

of Suicides” will be able to understand the extent to which

Carlyle was influenced by his sympathies. A man who, like

Cooper, had been in jail for Chartist opinions, might be pretty sure

in those days of getting a certificate for some “traces of genius”

from Carlyle.

――――♦――――

From:

LEAFLETS FROM MY LIFE: A NARRATIVE AUTOBIOGRAPHY

(1888)

by

MARY KIRBY.

Chapter XIX. - Thomas Cooper and the Chartist Riot.

FOR many a long

year, I may say for centuries past, the staple trade of Leicester

has been the manufacture of hosiery in all its branches.

My father had served an apprenticeship, as we have said, in

Mr. Pares' warehouse in the Newark; and in after life, carried on a

prosperous business of his own.

He had built a warehouse, as we may remember, in the

Millstone Lane, and his factory for wool spinning, was in the

Redcross street.

New machinery was constantly being introduced; and one day at

dinner, he told us that he would take us down to the factory, to see

a carding machine, which would supercede the wool being combed by

hand.

In these modern days, when the four quarters of the globe are

brought within such easy distance of each other, wool is imported

from every part of the world; but when we were young, it was not so,

and the fleeces, that lay under a shed in the factory yard, were

probably of home growth. Be that as it may, we stayed and

watched the wool going through a number of processes, preparatory to

its being spun. The steam-engine, at work somewhere out of

sight, was certainly not out of mind, and wheels kept whizzing, and

straps kept flying over our heads, in all directions, and we could

not help wondering how day after day, and year after year, women and

girls, could go on working in such a clatter of noise.

Fine threads of worsted kept coming out of the mouths of the

frames, in a misty cloud, that looked almost like smoke; and the

young people went along the room from one frame to another, and

pushed it down into the baskets, set on purpose to catch it, for it

was too light to fall of itself.

When the wool was thus spun into fine yarn, it was carried

away to another building full of stocking frames, where it was woven

as required, and according to orders.

In olden times, before there were any frames to be had, the

inhabitants of Leicester, used to knit stockings by hand, in large

quantities; and a pretty story is told, of how it came to pass, that

their handy-work ceased to be wanted.

A curate, the Rev. William Lee, from the country, was paying

his addresses to a young lady, who lived in Leicester; and whenever

he came to see her, it troubled him to find her always knitting, for

he fancied she took more interest in her work, than in what he had

to say to her. So he devised a plan to stop the everlasting

play of those knitting pins; and with a great deal of thought and

trouble, invented a machine, that could make a pair of stockings in

much less time than she could.

This ingenious invention was shown to Queen Elizabeth, who was asked

to patronize it. But the Queen was not very warm in the cause, and

said it would be a bad thing to take the knitting out of the hands

of the poor people; but added, if Mr. Lee could make her a pair of

silk stockings she might have something to say to him, and grant him

a patent.

The silk stockings were duly sent. But alas for the hard-hearted

Queen! she disappointed the hopes and expectations of Mr. Lee; and

like most inventors, he died of a broken heart; while another man,

obtained the patent for his discovery and carried off the fortune.

Those who live in a manufacturing town only know, the uncertainty of

the working classes; and the readiness with which, on the slightest

pretext, they throw themselves out of work, without any notice

whatever. It is in fact, the vexed question of capital and labour,

that is always in danger of cropping up.

And so it happened in Leicester about this time, the year, I believe

1842, that the stocking makers demanded an advance of wages, which

the masters refused to give. Murmurings and threats followed, and by

and bye a strike was the result.

The consequences as they always are, were disastrous; innocent women

and children were left without bread to eat, while the men went

about in groups from door to door, ostensibly begging, but in

reality demanding money or food.

Satan can always find some mischief for idle hands to do, — and when

a number of men are out of work, they fly to politics, and to the

abuse of their betters, their rulers, and particularly those who are

better off than themselves.

On the present occasion, the mob were Chartists; and at their head

was the well-known Thomas Cooper, who possessed talents and powers

of mind, far beyond the rest, which made him the more dangerous, for

he was able to sway the men whichever way he pleased.

Sunday afternoon was the most convenient time for them to hold their

meetings; and the Market Place they found best suited for the

purpose. So there, a great crowd of the unemployed used to collect,

and with plenty of hooting and shouting (which we could hear as we

sat at home), listened to addresses from their leaders, which were

calculated to urge them on to acts of violence; and when the

speeches were over, the men would come tramping down the Friar Lane,

half-a-dozen or more abreast, and make a great noise, that was

intended for singing. The song was all about the Charter, and had a

refrain of —

|

Britains bold join heart and hand,

To spread the Charter through the land. |

We knew very well what the Charter meant — universal suffrage,

admission into Parliament of poor men without any property

qualification whatever, and a few more such comfortable doctrines.

As it happened, one of our maids called "Mercy," was a relative of

Thomas Cooper's, and we noticed how very quick she was in closing

the shutters, as soon as ever she heard the least noise or

commotion. We

hoped this girl would be a protection to us, and such might have

been the case, as we certainly were not molested.

The excited feelings of the mob were brought to a crisis, by the

fact of a contested election, just then coming on.

On the day of nomination, and while the members were on the

hustings, and speeches were being made, a practical joke was played

off upon Cooper.

A large tin extinguisher, made for the purpose, and fastened at the

end of a long pole, was dropped adroitly over him, and completely

covered him, — or as his opponents said, "put him out." Cooper,

however, took

the jest in good part, and almost immediately started a Chartist

paper, calling it the "Extinguisher."

The next thing that followed, was a riot, dignified by the name of

the Bastile Riot, because the workhouse was attacked, and all its

windows broken. Sticks and stones flew freely about, and the police

were no match for the mob.

The whole town was in a state of confusion, and the streets so

crowded, that when at last a few of the ringleaders were arrested,

it was difficult to get them along.

Cooper pushed himself into the justice room, and undertook to defend

the prisoners himself; but the magistrates refused to hear him, on

the ground of his not being a qualified lawyer.

Nobody knows what more mischief might have been done, had not a

troop of horse, fortunately arrived from Nottingham, in time to

prevent it. They drove the mob before them, and the worst of the

rioters were safely lodged in gaol, and all anxiety speedily brought

to an end.

We were very glad to hear some few years later, that Thomas Cooper

had changed his course of life, and was putting his talents to a

good purpose. After lying in prison and suffering great privations

from insufficient food, and a miserable bed, — he rose above it all,

and having educated himself in the most heroic manner, he earned a

comfortable livelihood, by giving lectures on history and

philosophy as well as on theology.

The story he has given us of his adventures in his "Autobiography"

is both romantic and interesting; and in the little work he has

more recently published, called "Thoughts at Fourscore," we see

plainly how altered are his views, and his ideas of life.

――――♦――――

THE TIMES

Saturday, July 16, 1892.

OBITUARY.

_______

THOMAS COOPER.

Mr. Thomas Cooper, the well-known Chartist leader

Christian lecturer, died at Lincoln yesterday afternoon, in the 88th

year of his age. On Thursday he was seized with a slight attack of

illness, which in his enfeebled state left him entirely prostrate, and

he passed peacefully away. The career of this well known Chartist

leader and religious and political controversialist furnishes another

example of the triumphs which may be achieved by indomitable resolution

and perseverance in the humblest spheres. By his father's side,

Thomas Cooper was descended from Yorkshire Quakers. He was born as

Leicester in March, 1805. Before he was 12 months old, his father,

who was a travelling dyer, removed his family to Exeter. It is

said that young Cooper learned to read almost without instruction, and

that at the age of three he was set to teach a youth of seven his

letters. Mrs. Cooper, being left a widow when her son was only

four years old, quitted Exeter for her native Lincolnshire, and settled

down at Gainsborough, where the next 25 years of Thomas Cooper's life

were passed. One of the first friends he made was Thomas Miller,

the poet, who was learning the trade of basket-making when the youths

became acquainted. In 1813 Cooper was sent to the Bluecoat School.

From 1816 to 1820 he was at a private school, where he greatly extended

his reading in history, poetry, and other subjects. Necessity

compelled him to learn a craft for his livelihood, and at the age of 15

he was apprenticed to a shoemaker. Whilst pursuing his trade he

gave up every moment of spare time to his books, rising every morning at

3 or 4 o'clock in order to study. By the time he was 23 he had

taught himself the Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and French languages, together

with mathematics and a knowledge of English history and literature.

His general reading was at the most, extensive and varied character, and

by way of recreation the omnivorous student would commit such

masterpieces as Hamlet to memory. But circumstances at this time

were very adverse for Cooper, and in describing the period long

afterwards he said, "I not unfrequently swooned away and fell along the

floor when I tried to take my cup of oatmeal gruel at the end of the

day's labour. Next morning, of course, I was not able to rise at

an early hour; and then the next day's study had to be stinted. I

needed better food than we could afford to buy, and often had to contend

with the sense of faintness, while I still plodded on with my double

task of mind and body." A serious illness ensued, during which he

was once given up for dead.

In 1828 Cooper abandoned his trade of shoemaking had

opened a school, to which the children of poor parents flocked eagerly.

A year later, after mental struggles and much spiritual wrestling, he

joined the Wesleyan Methodist body and became local preacher. In

1834 her married the sister of a revivalist preacher in Lincoln and

established a school in that city. Here he had much to do with the

foundation and prosperity of the Lincoln Mechanics' Institute and the

Lincoln Choral Society. He also acted as correspondent for the

Lincoln, Rutland, and Stamford Mercury. It was at this time

that he conceived the idea of his ambitions poem on "The Purgatory of

Suicides." Cooper was a strong Radical in politics, and he wrote

warmly in support of Sir Edward Lytton Bulwer, who was then in great

favour with the Liberal electors of Lincoln. After a brief

residence at Stamford, whither he moved upon leaving Lincoln, Cooper

went to London in 1839, where he passed through many vicissitudes in

endeavouring to launch himself upon a journalistic and literary career.

For a brief period he resided at Greenwich, where he edited the

Kentish Mercury. In 1840 he moved to Leicester, his

birthplace, became associated with the Leicestershire Mercury,

joined the Chartists, and conducted the Chartist organ, the Midland

Counties Illuminator. Cooper soon became recognized as the

leader of the Chartists, and was nominated as a Parliamentary candidate

both for the the town and county, but was not returned. Among the

converts to Chartist views, whom Cooper made by his eloquent appeals,

was a youth of 15, named Anthony John Mundella, whose later career is

sufficiently well known.

Cooper lived to see that Chartism was but the fly on

the wheel during this great period of political agitation. Free

trade became the one overwhelming cry of the nation, though there were

many sanguine spirits who thought that an enlargement of the franchise,

with the accompanying political demands embodied in the People's

Charter, would take precedence of Corn Law Repeal. Cooper was one

of these, and clung enthusiastically to the case when others wavered or

altogether abandoned it. Being elected delegate from Leicester to

the Chartist Convention at Manchester in August, 1842, be went thither

by way of the Staffordshire Potteries. He addressed a number of

large gatherings of working mean, and on August 15 took the chair at a

great meeting held on the Crown Bank at Hanley. The fiat had

already gone forth in various parts of the country that all labour

should cease until the people's Charter became the law of the land, and

in some places riots had occurred. The Hanley meeting passed off

peaceably, and Cooper, personally, strongly appealed for the observance

of law and order. But a riot had taken place at Longton, and the

noisy spirits of Hanley endeavoured to promote a riot there also.

Cooper, who was widely known, was advised by his friends to leave the

town, and he did so. But he had scarcely got away when the spirit

of turbulence triumphed, and Hanley was the scene of riot and excess.

At Burslem Cooper was arrested, and was released for lack of evidence.

On reaching Manchester the city appeared to be almost in a state of

siege. All the manufactories were closed, and cavalry and

artillery were parading the streets. The convention was held on

the 17th, and Cooper and other chartists recommended armed resistance to

the law. An address was afterwards printed and sent out for

distribution by the executive. The police arrested some of the

leaders, but Cooper got away to Leicester. Here several out-door

demonstrations were held, but they were dispersed by the county police.

Cooper was arrested on a warrant held by the constable of Hanley, and

conveyed back to the Potteries. He was committed to Stafford Goal

on the charge of aiding in the riot at Hanley, and while awaiting his

trial he composed several of the simple tales which will be found in

"Wise Saws and Modern Instances," published in 1845. The assizes

began on October 11, 1852, began Lord Chief Justice Tindal. Cooper

was charged with the crime of arson, but as it was conclusively shown

that he was in Burslem and not in Hanley at all at the time when the

offence was committed, the jury returned a verdict of "Not Guilty."

Two days later he was again arraigned, this time on the charges of

conspiracy and sedition. The trial was postponed, however, and

after five weeks Cooper was liberated. On arriving at Leicester he

was made the hero of demonstrations throughout, the town.

Divisions now assailed the Chartist party. The

cause was practically ruined by the time when Cooper's second trial came

on at the Stafford Assizes, March 20, 1843. Sir Thomas Erskine was

the Judge, and the chief counsel against the prisoner was the scholarly

Sergeant Talfourd, M.P. Cooper conducted his own defence, and

delivered a powerful speech. But there were certain stubborn facts

in the way of an acquittal, and the prisoner was found guilty of

conspiracy and sedition, and sentenced to two years' imprisonment in

Stafford Goal. While in prison Cooper began the composition of "The

Purgatory of Suicides," an epic poem in ten books, written in the

Spencerian stanza. This "Mind History," as the author described

it, dealt with great social and religions questions of the past and

present, making the spirits of suicides the actors or speakers.

Now, for some time, Cooper had been gravitating towards

atheistical opinions. He had been treated by his Methodist friends

in a manner which did not seem to him to savour of Christianity; his

wife was ill and bed-ridden; and his own imprisonment reacted upon his

sensitive nature. After his release from goal in 1845 he studied

the translation of Strauss begun by Charles Hennell and finished by

George Eliot. He became, as he himself said, "fast bound in the

net of Strauss," nor was he thoroughly able to break its meshes for 12

years. Cooper applied to Tom Ducombe, the eccentric member for

Finsbury, to find him a publisher for his poem, and Duncombe gave him

this characteristic note to Mr. Disraeli:—

"My dear Disraeli,— I send you Mr. Cooper, a Chartist,

red hot from Stafford Goal. But don't be frightened. He won't bite you.

He has written a poem and a romance; and thinks he can cut out a 'Coningsby'

and 'Sybil'! Help him if you can, and oblige yours, T. S. DUNCOMBE."

Disraeli received Cooper very kindly and gave him notes

to Moxon and Colburn, but these and other publishers would do nothing;

"poetry was an absolute drug in the market.'' Douglas Jerrold and

Charles Dickens subsequently read "The

Purgatory of Suicides," of which they formed a high opinion, and

Jerrold secured a publisher for it. The work appeared in 1845, and

the first edition of 500 copies was sold off before Christmas. It

was succeeded by another poem, "The Baron's

Yule Feast," dedicated to the Countess of Blessington. Carlyle

wrote to the author concerning his "Purgatory of Suicides":—"I have

looked into your poem, and find indisputable traces of genius in it—a

dark, Titanic energy struggling there, for which we hope there will be

clearer daylight by and by." Carlyle not only helped Cooper with

advice, but by substantial acts of kindness. In 1846, while in the

Lake District, Cooper had an interview with the venerable poet

Wordsworth, who engaged him in a long conversation upon poets and

poetry, and the events of the day. When they parted, Wordsworth

said with emphasis, "The people are sure to have the franchise as

knowledge increases; but you will not get all you seek at once, and you

must never seek it again by physical force; it will only make you the

longer about it."

In 1847 Cooper published his "Triumphs

of Perseverance" and "Triumphs of

Enterprise." In the same year he joined Mazinni's new society,

"The People's International League," which held its London meetings at

the residence at the residence of the secretary,

W. J. Linton, the engraver, in Hatton-garden. From the

Chartist meetings and disturbances of 1848, however, he kept entirely

aloof; and he was in complete disagreement with Feargus O'Connor over

his land scheme. Cooper now became an active political and

historical lecturer in London and in all parts of Great Britain and

Ireland. His first novel, "Alderman Ralph," was published in 1853,

and another following in the succeeding year. Towards the close of

1855 Cooper's opinions on religious questions underwent a change.

He had never lectured as an infidel, but he had certainly given

utterances of sceptical opinions. He now renounced these opinions,

declared himself to be firmly convinced of the existence of a Divine

Moral Governor, of the universe, and for many years lectured upon the

Evidences of Christianity. In September, 1856, he began a course

of Sunday evening lectures and discussions with the London sceptics, and

continued them until the end of May, 1858. In the latter year Mr.

Cowper-Temple found him employment in the Department of the Board of

Health, where, in addition to routine work, he assisted Dr. Simon, of

the Privy Council Office, in the preparation of his valuable report on

vaccination. In 1859, having become thoroughly settled in his

religious convictions, Cooper joined the general Baptist body, and from

time to time preached under the auspices of that organization.

Shortly before taking that step he had held several public discussions

with George Jacob Holyoake, but long

afterwards he expressed his clear conviction that public discussions on

the evidences of Christianity never do any good and often do great harm.

At length his health broke down, and Mr. W. E. Forster, Mr. Samuel

Morely, Dr. Jobson, and other friends initiated a subscription for him

in his illness and his need. Eventually a sum of £1300 was raised,

which was used in the purchase of an annuity of £100 in the National

Debt Office, for himself and his wife.

From 1867 to 1872 Cooper was again employed in

lecturing. In 1878 his "Political Works" were collected and

published, and shortly afterwards appeared "The

Bridge of History over the Gulf of Time." In 1882 he published

his

Autobiography, and since that period has

lived in retirement. During the course of his long career Cooper

was thrown into contact with many of the most distinguished men of his

time in literature and politics. His character was strongly

marked, and it was impossible not to be struck by his honesty, his

manliness, and his independence. His opinions on many questions

were extreme, but his sincerity was undoubted.

In 1886, when the Home Rule Bill was introduced, Cooper

said in a letter to the secretary of the Liberal Unionist Society in

Lincoln:—"I shall not vote at the city election because I agree with

neither of the candidates. The Tory candidate knows perfectly well

that the old Chartist prisoner cannot vote for him. I cannot vote

for the Liberal candidate because, so far as my perception reaches, it

would be voting in the dark. The Irish people share the common

privileges of English, Scotch and Welsh men. What is it that they

want besides? I ask the question because they never tell us what

they really want. Home Rule is a vague answer, for it may have 20

meanings, and none of them be good. Lately Mr. Gladstone has

invented a new phrase—he proposes to give Ireland a 'statutory

Parliament.' But what is that, and wherein does it differ from our

Parliament? Why do the Irish want a separate Parliament? It

would only help make us more and more divided instead of a United

Kingdom. I must declare, whatever offence it may give to some

people, that the Irish cry of Home Rule means separation from England,

and that would be ruin to Ireland herself and a costly war for England."

――――♦――――

The Times,

July 19th, 1892.

FUNERAL OF THOMAS COOPER.

The funeral of Thomas Cooper, the Chartist leader and poet, who died

on Friday last, took place at Lincoln yesterday afternoon. The

first part of the funeral service was conducted in the Thomas Cooper

Memorial Baptist Chapel, which was recently built and named in his

honour. The service was conducted by the Rev. Arthur O'Neill,

of Birmingham, the Rev. E. H. Jackson of Louth, and the Rev. J.

Bennett, of Lincoln. After the service the Rev. Arthur

O'Neill, a fellow Chartist prisoner, delivered an address. He

said it was as nearly as possible 50 years since Thomas Cooper and

he stood together on a platform before 20,000 people at Wednesbury,

and he could well remember Cooper's ringing voice, the intense

enthusiasm which he felt, his deep sympathy and pity for the poor,

his tremendous denunciation of wrong, and the fearless way he met

oppressors. He rejoiced that after 50 years nearly every point

they advocated had been accomplished. Mr. O'Neill went on to

speak of the days he had spent in Stafford Goal in company with

Cooper, and of a second occasion when he was in prison for a year

with him. He commended to young men Cooper's political and

patriotic efforts as a worthy of imitation, and concluded by stating

that, as far as he could discover, he was the last Chartist prisoner

in England, although there were some in America. The Rev. E.

H. Jackson also delivered an address, and he was followed by the

Rev. J. Bennett. There were but few people at the ceremony,

where the concluding portion of the burial service was read by the

Rev. E. H. Jackson.

――――♦――――

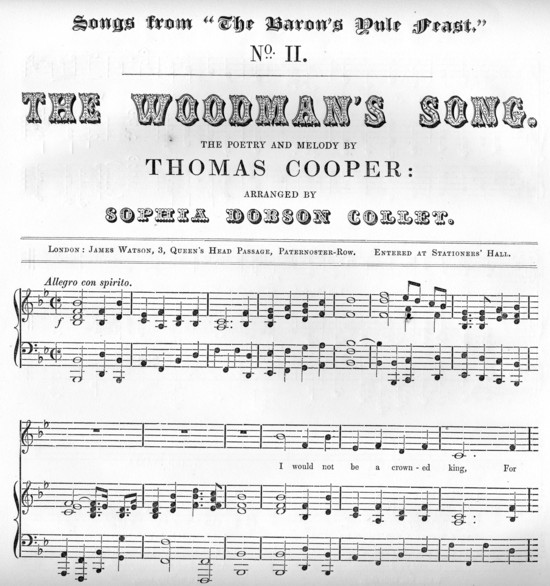

SONGS

by

THOMAS COOPER.

|

|

"THE MINSTREL'S SONG"

Words and melody by Thomas Cooper,

arranged in four parts with piano accompaniment by

Sophia Dobson Collet.

(2 pages, .pdf, 400KB. To

download, right click, and

then 'save target as'.) |

|

"THE WOODMAN'S SONG"

Words and melody by Thomas Cooper,

arranged in four parts with piano accompaniment by

Sophia Dobson Collet.

(2 pages, .pdf, 450KB. To

download, right click, and

then 'save target as'.) |

|