|

[Previous Page]

PART II.

DESCENTS OF THE RHÔNE AND

THE TARN

CHAPTER X.

FROM LYONS TO AVIGNON

FROM Lyons to

Avignon by river is one of the finest sails in Europe, to my

thinking the scenery surpassing that of the Danube or the Rhine.

Picturesque and interesting as are the railway journeys by both

right and left banks, the steamer offers a thousandfold of charm.

By half-past five o'clock on a brilliant August day, myself

and friend were aboard the little Gladiateur, finding thereon

a scene of indescribable liveliness and bustle. All kinds of

merchandise were being stowed away—bedding, fruit, bicycles,

bird-cages, passengers' luggage, cases, and packages of every

imaginable description.

A stream of peasants poured in, bound for various stations on the

way, all heavily laden, some accompanied by their pet dogs. First-class passengers were not numerous. We had an elderly

bridegroom, who might have been a small innkeeper, with his youthful

bride, evidently making a cheap wedding trip; a family party or two;

an excitable man with a sick wife; a couple of pretty girls with two

or three youths—brothers or cousins; a sprinkling of priests and

nuns—that was all. The peasants with their baskets and bundles, at

the other end of the vessel, made picturesque groups, and the whole

scene was as French as French could be.

I was just thinking how pleasant it was thus to escape the routine

of travel, to find one's self in a purely foreign atmosphere,

picking up by the way French habits and ways of thought, when one of

the officials of the company bustled up to me.

"Pray pardon me, madame," he said, bringing out a note-book. "I see

that you are English. Will you be so very kind as to give me the

name and address of the great tourist agency in London? We are

organizing an entirely new service between Lyons and Avignon; we are

going to make our steamers attractive to tourists. You will oblige

us extremely by giving a little information."

Crestfallen and with a sinking of the heart, I took his pencil—I

could, of course, not do otherwise—and wrote in big letters:

MM. THOMAS COOK ET CIE,

Ludgate Hill,

Londres.

But those few words I had written sufficed to dispel the delightful

vision of the moment before. Another year or two, then, and the

Rhône will be handed over to Messrs. Cook, Gaze and Caygill—benefactors

of their kind, no doubt, but ruthless destroyers of the romance of

travel! Instead of French folk, with whom we can chat about their

crops, rural affairs, and passing scenes, gaining all kinds of

information, feeling that we are really in France, and forgetting

for a while old associations, henceforth we shall find on board

these steamers our near neighbours, whom, no matter how much

respected, we are glad to quit for a time. From end to end of the

vessel we shall hear the voices of English and Transatlantic

tourists, one and all most probably "disappointed in the Rhône;"

but, indeed, for the river, we should as well be at home! However, I

said, all this disenchantment happily belongs to the future; let us

enjoy the present experience—one long bright summer day, so full of

impressions as to seem many days rolled into one. Years have glided

on, meantime the cycle and the motor, in a great measure, have

replaced slower methods of locomotion, but such prognostics have not

been fulfilled. The Rhône has escaped vogue.

The whistle sounds, punctually to the stroke of six; we are off.

It is a noble sight as we steam out of the quay de la Charité: the

vast city rearing its stately front between green hills and meeting

rivers; above, white châteaux and villas dotting the greenery—below, the quays, bordered with dotting warehouses that might be

palaces, so lofty and handsome are they, and avenues of plane-trees.

The day promises to be splendid, but mists as yet hang over the

scene. Leaving behind us majestic city suburbs and the confluence of

the Rhône and the Saône—one silvery sheet flowing into the other—we

glide between low-lying banks bordered with poplars, and soon reach

the little village of Irigny, its sheltering hills dotted with

country houses. As we go swiftly on we realize the appropriateness

of the epithet applied to the Rhône. Truly, in Michelet's phrase, "C'est

un taureau furieux descendu des Alpes, et qui court à la mer." If

we are impatient to reach our destination in the heart of the

Cévennes, the Rhône seems still more in haste to reach the sea. This

extraordinarily swift current of the bright blue waters and the

unspeakable freshness and purity of the air make our journey very

exhilarating. Past Irigny we are so near the low, poplar-bordered

shore to our left, that we could almost reach it with a pebble,

whilst to the right lies Millery. From this point the river winds

abruptly, and we see far-off heights and gentle declivities nearer

shore, with vineyards planted on the slopes. The country on both

sides is beautifully wooded, and very verdant.

The first halt is made at Givors, a little manufacturing town set

round with vine-clad banks; here the little river Giers flows into

the Rhône, one of the numerous tributaries gathered on the way. Just

below the town is a graceful suspension bridge. But for the mists we

should have a lovely view a little further on, where the hills run

nearer together, the wooded escarpments running steep down to the

water's edge. On both banks the scenery becomes charming. Close to

our left hand rise banks fringed with silvery-green willows, and

above a bold line of summits, part wood, part vineyards, with white

houses peeping here and there; on our right, a little island-like

group of poplars, the whole picture very sweet and pastoral.

As we near Vienne the aspect changes. There is an Italian look about

the vines trellised on trees and festooned around the river-side châlets.

The approach to the ancient city itself is very striking. A light

suspension bridge spans the river banks just where Vienne faces the

village of St. Colombe, ancient as itself. On the right we see the

massive old tower built by Philippe de Valois; to the left, behind

the houses crowded together pell-mell, rises the majestic pile of

the cathedral. Here another tributary, the Gère, flows into the

Rhône. Vienne was reputed a fosterer of poetry in classic times. At

"beautiful Vienne," Martial boasted that his works were read with

avidity. The scenery now shows more variety and picturesqueness. In

one spot the river winds so abruptly that we seem all on a sudden to

be landlocked, the hills almost meeting where the impetuous current

has forced a way. The cleft hills as they slope down to the shore

show deliciously fresh and verdurous dells and combes. Everywhere we

see the vine, and with every bend we seem nearer the South. Between

Vienne and Roussillon the aspect is no longer French, but

Italian—the distant undulations being of dark purple, flecked with

golden shadow, the nearer, terraced with the yellowing vine.

Our next halting-place is Condrien, on the right bank, celebrated

for its white wines, a pretty little town, with vineyards and

gardens close to the riverside, the bright foliage of garden acacia

and vine contrasting with the soft ochres and greys of the

building-stone. Above the straggling town on the sunny hill are

deep-roofed châlets, and close to us—we could almost gather

them—patches of glorious sunflowers in the river-side gardens. The

mists had now cleared off, and we were promised a superb day.

The traveller's mind is all at once struck by the extreme solitude

of this noble, vast-bosomed, swift-flowing river. We had been on the

way for hours without seeing a steamer or vessel of any kind, our

little craft having the wide water-way all to itself. Whilst the

Saône is the most navigable river in the world, quite opposite is

the character of its brother Rhône. Not inaptly has the one—all

gentleness, yieldingness, and suavity—won a feminine, the other—all

force, impetuosity and stern will—obtained for itself a masculine,

appellative! And well has the Lyonnais sculptor given these

characteristics in his charming statues adorning the Hôtel-de-Ville

of his native city.

The Rhône has been called "un chemin qui marche trop vîte"; the

rapidity of its currents and the difficulties of navigation

up-stream are obstructions to traffic. But before the great line of

railway was laid down between Paris and Marseilles, it was

nevertheless very important. If we converse with French folk whose

memory goes back to a past generation, we shall find that the

journey south was invariably made this way. Formerly sixty-two

steamers daily plied with passengers and goods between these

riverside towns, now connected by railway. At the present time seven

or eight suffice for the work.

This solitude adds to the majesty and impressiveness of the Rhône.

Our little craft seems insignificant as a feather—a mere bird

skimming the vast blue surface. After the clearing of the mists, we

have a spell of unbroken blue sky and bright sunshine, followed by a

deliciously cool, grey English heaven, with sunny glimpses and

varied cloudage.

Passing Serrières, with pastures and meadows close to the water's

edge, and groups of cattle grazing under the trees, we reach Annonay,

crested by a quaint ruin, the birthplace of the great balloonists,

the brothers Montgolfier. The first balloon ascent was made from

this little town in 1783. Boissy d'Anglas, the heroic president of

the Assembly in its stormiest days, was also born here.

Next comes St. Vallier, an ancient little town close to the bank,

with its castle of the beauty who never grew old, Diane de

Poitiers—she whose mysterious cosmetic was a daily plunge in cold

water; so say the initiated in historic secrets. Opposite to St. Vallier rises a chain of sunny, vine-covered hills, with sharp

clefts showing deep shadow.

At Arras, on the right bank, is seen another picturesque ruin. No

river in Europe boasts of more ruins than the Rhône. Then we reach

the legendary rock called the Table du Roi. Just as Æneas and his

companions made plates of their flat loaves, and so fulfilled the

Sybil's prediction, St. Louis saw in this tabular block a

dinner-table, providentially designed for the use of himself and his

ministers. The great advantage of such a table lay in its immunity

from listeners, thus the story runs. This al fresco banquet

above the banks of the Rhône took place on the eve of the Seventh

Crusade.

At this point the river is magnificent. Beyond the nearer hills rise

the crumbling walls of a feudal stronghold, another ruin of

imposing aspect. One hoary tower only is seen, half hidden by the

folds of a valley. On every slope the vines make golden patches,

little terraces being planted close to the rocky summits. This

persistence in a phylloxera-ravaged district is quite touching.

Passing Tournon and Tain, we soon come in sight of the famous little

village of the Hermitage, a sunburnt, granitic slope, its three

hundred acres once being a mine of gold. Formerly a hectare of this

precious vineyard was worth 30,000 francs. The phylloxera invaded

it!

We now see in the far distance the blue range of the Dauphinnois

Alps, and can it be—is yonder silvery glimmer on the farthest

horizon the mighty Mont Blanc? Nothing can be lovelier than these

wide mountain vistas, far above broad blue river, plain, and hill.

Passing the stately Gothic château of Châteaubourg, where sojourned

St. Louis, we get a glimpse of the sharply outlined limestone

heights bordering on the vineyards of St. Percy, no less celebrated

than those of the Hermitage. On the topmost crag stand out in bold

relief the superb ruins of Crussol. At every turn we see walls of

feudal strongholds frowning above the bright, broad river. By the

time we reach Valence, soon after mid-day, we have only passed one

barge.

Valence is beautifully situated. Facing the river and tawny, abrupt

rocks, rises the splendid panorama of the French Alps. Here we leave

more than half our passengers and merchandise. The cook, having now

nothing to do, comes on deck to chat with a friendly traveller. I

may as well mention that we fared as well on this little steamer as

at a second-class table-d'hôte. There was a small dining-room

below, as well as a very fairly comfortable saloon. The attendants

were exceedingly civil, and charges regulated by a tariff.

As an instance of the prevailing desire to please, I cite the

following piece of amiability on the part of the chef. I had

given tea and a tea-pot, with instructions, to the waiter. The

chef, however, anxious that there should be no blunder, came up

to me and begged for information at first hand.

"Pray excuse me," he said; "but I did not understand whether the

milk and sugar were to form part of the decoction."

I gave him a little dissertation on tea-making, with the result that

future travellers by the Gladiateur, will obtain a fragrant

cup admirably prepared. Even a French chef cannot be expected

to know everything in the vast field of cookery.

Below Valence the scenery changes. The hills on either side of the

river recede, and we look above low reaches and lines of poplar upon

the far-off mountain range of Dauphine and Savoy. Here and there are

little farmsteads close to the shore, with stacks of wheat newly

piled and cattle grazing—everywhere a look of homely plenty and

repose. The river winds in perpetual curves, giving us new horizons

at every turn.

Lavoulte, on the right bank, is a picturesque congeries of red-tiled

houses massed round a square château. The town indeed looks a mere

appendage of this château, so conspicuous is the ancient stronghold

of the Vivarais. Livron, perched on a hill, looks very pretty. Soon

we come to perhaps the grandest ruin cresting the bank of the Rhône,

the donjon and château fort of Rochemaure, standing out formidably

from the dark, jagged peaks, running sheer down to the river's edge.

After Le Teil is passed the clouds gradually clear. We have the deep

warm blue of a southern sky and burning sunshine.

Viviers—former capital of the Vivarais, to which it gave the name—is

most romantically placed on the side of a craggy hill, its ancient

castle and old Romanesque cathedral conspicuous above the

house-roofs. Just above the verdant river-bank run its mediæval

ramparts tapestried with ivy, the yellowish stone almost the colour

of the rocks.

The scenery here is wild and striking. Far away flashes the grand

snow-tipped Mont Ventoux, limestone cliffs show dazzlingly white

against the warm heavens, deep purple shadows resting on the

vine-clad slopes, whilst close to the water's edge are stretches of

velvety turf and little shady vales. At one point the opposite

coasts are as unlike in aspect as summer and winter; the right bank

all grace and fertility, the left all barrenness and desolation. And

still we have the noble river to ourselves as it winds between rock

and hill. Pont St. Esprit is another old-world town with a wonderful

bridge, making a charming picture. It stands close to the water's

edge, the houses grouped lovingly round its ancient church with tall

spire. Here we do at last meet a steamer bound for Valence.

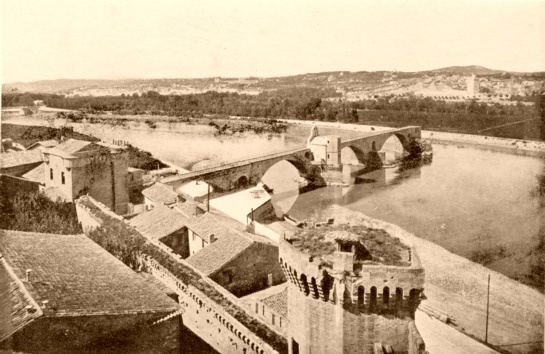

APPROACH TO AVIGNON

After leaving Pont St. Esprit the scenery grows less severe, till by

degrees all sternness is banished, and we see only a gentle pastoral

landscape on either side.

Bagnols, with its handsome old stone bridge, church with perforated

tower, facing the river, makes a quaint and picturesque scene. This

curious town, one of the most characteristic passed throughout the

entire journey, lies so close to the water's edge that we could

almost step from the steamer into its streets. Meantime, the long,

bright afternoon, so rich in manifold impressions, draws on;

cypresses and mulberry-trees announce the approach to Avignon. A

golden softness in the evening sky, a heavy warmth and languor in

the air, proclaim the South. Every inch of the way is varied and rememberable. Feudal walls still crest the distant heights, as we

glide slowly between reedy banks and low sandy shores towards the

papal city.

At last it comes in sight, rather more than twelve hours since

quitting the quay of Lyons, and well rewarded were we for having

preferred the slower water-way to the four hours' flight in the

railway express.

The approach to Avignon by the Rhône may be set side by side in the

traveller's mind with the first glimpse of Venice from the Adriatic,

or of Athens from the Ægean.

The river, after winding amid cypress-groves, makes a sudden curve,

and all of a sudden we see the grand old city, its watch-towers,

palaces, and battlements pencilled in delicate grey against a warm

amber sky, only the cypresses by the water's edge making dark points

in the picture. Far away,

over against the city, towers the stately snow-crowned Mont Ventoux

and the violet hills shutting in Petrarch's Vaucluse. How warm and

southern—nay, Oriental—is the scene before us, although painted in delicatest pearly tints! It is difficult to believe that we are

still in France; we seem suddenly to have waked up in Jerusalem!

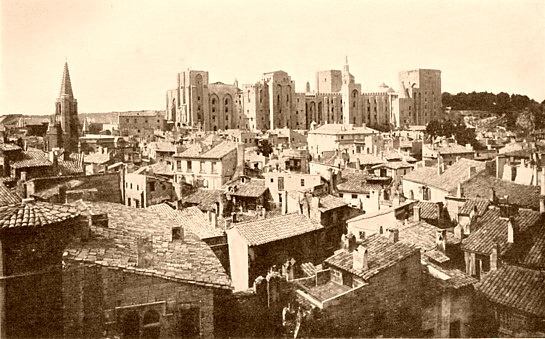

AVIGNON, CHÂTEAU DES PAPES

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XI.

TO MENDE BY WAY OF LE VIGAN

ON a former

occasion I had set out for the Gorge of the Tarn from Le Puy, thence

by train journeying to Langeac, from that little junction to another

named Langogne, and from that point finishing the long day in the

crazy old diligence plying between Langogne and Mende. An amazing

six hours' drive it was, and well worth the fatigue, every bit of

the way abounding in scenery, splendid or pastoral. France can

hardly show fairer or more striking scenes than these highlands of

the Lozère.

The first part of our way lay amid wild mountain passes, deep

ravines, dusky with pine and fir, lofty granite peaks shining like

blocks of diamond against an amethyst heaven. Alternating with such

scenes of savage magnificence are idyllic pictures, verdant dells

and glades, rivers bordered by alder-trees wending even course

through emerald pastures, or making cascade after cascade over a

rocky bed. On little lawny spaces about the sharp spurs of the Alps,

we see cattle browsing, high above, as if in cloudland. Excepting an

occasional cantonnier at work by the roadside, or a peasant woman

minding her cows, the region is utterly

deserted. Tiny hamlets lay half hidden in the folds of the hills or

skirting the edges of the lower mountain slopes; none border the

way.

During the long winter these fine roads, winding between steep

precipices and abrupt rocks, are abandoned on account of the snow. The diligence ceases to run, and letters and newspapers are

distributed occasionally by experienced horsemen familiar with the

country and able to trust to short cuts.

What the icy blasts of January are like on such stupendous heights

we can well conceive. At one point of our journey we reach an

altitude above the sea equal to that of the Puy de Dôme. This is the

lofty plateau of granitic formation called Le Palais du Roi, a

portion of the Margéride chain, and as an old writer says, "la

partie la plus neigeuse de la route"—the snowiest bit of the road. On a superb September day, although winter, as I found, was at hand,

the temperature was of an English July. As we travelled on, amid

scenes of truly Alpine grandeur and loveliness, the thought arose to

my mind, how little even the much-travelled English conceive the

wealth of scenery in France! Our cumbersome old diligence carried

only French passengers. Nowhere else in Europe does the English

tourist still find himself more isolated from the commonplace of

travel.

Many of the landscapes now passed recalled scenes in Algeria,

especially as we get within sight of the purple, porphyritic chain

of the Lozère. We gaze on undulations of delicate violet and grey,

as in Kabylia, whilst deep down below lie oases of valley and

pasture, the dazzling golden green contrasting with the aerial hues

of distant mountain and cloud.

Nothing under heaven could be more beautiful than the shifting

lights and shadows on the remoter hills, or the crimson and rosy

flush of sunset on the nearer rocks; at our feet we see well-watered

dales and luxuriant meadows, whilst on the higher ground, here as in

the valley of the Allier, we have proofs of the astounding, the

unimaginable patience and laboriousness of peasant owners.

In many places rings of land have been cleared round huge blocks of

granite, the smaller stones, wrenched up, forming a fence or border,

whilst between the immovable, columnar masses of rock, potatoes,

rye, or other hardy crops, have been planted. Not an inch of

available soil is wasted. These scenes of mingled sternness and

grace are not marred by any eyesore: no hideous chimney of factory

with its column of black smoke, as in the delicious valleys of the

Jura; no roar of mill-wheel or of steam-engine breaks the silence of

forest depths. The very genius of solitude, the very spirit of

beauty, brood over the woods and mountains of the Lozère. The

atmospheric effects are very varied and lovely, owing to the purity

of the air. As evening approaches, the vast porphyry range before us

is a cloud of purple and ruddy gold against the sky. And what a sky! That warm, ambered glow recalls Sorrento. By the time we wind down

into the valley of the Lot, night has overtaken us. We dash into the

little city too hungry and too tired, it must be confessed, to think

of anything else but of beds and dinner; both of which, and of

excellent quality, awaited us at the old-fashioned Hôtel Chabert.

But we were already midway in September. Winter, we learned, was at

hand, and truly enough, on the 19th of September it overtook us. Perforce we had to content ourselves with a glimpse of that

wonderful table-land les Causses, truly called "The Roof of France,"

and forego the shooting of the rapids till another season.

By carriage—an expensive and tedious but gainful method of travel—we

reached Rodez, spending the night at St. Chély d'Apcher.

At St. Amans, where we halted for breakfast, still the sun shone

warm and bright, and the blue sky was of extraordinary depth and

softness. I was reminded of Italy. As we sauntered about the long

straggling village, a scene of indescribable contentment and repose

met our eyes. We are in one of the poorest departments of France,

but no signs of want or vagrancy are seen. The villagers, all neatly

and suitably dressed, were getting in their hay or minding their

flocks and herds, with that look of cheerful independence imparted

by the responsibilities of property. Many greeted us in the

friendliest manner, but as we could not understand their patois, a

chat was impossible. They laughed, nodded, and passed on.

No sooner were we fairly on our way to St. Chély than the weather

changed. The heavens clouded over, and the air blew keenly. We got

out our wraps one by one, wanting more. If the scenery is less

wildly beautiful here than between Mende and St. Amans, it is none

the less charming, were we only warm enough to enjoy it. The pastoralness of many a landscape is Alpine, with brilliant stretches

of turf, scattered châlets, groups of haymakers, herds and flocks

browsing about the rocks. Enormous blocks of granite are seen

everywhere superimposed after the manner of dolmens, and everywhere

the peasant's spade and hoe are gradually redeeming the waste. It

was nightfall when we reached St. Chély d'Apcher, reputed the

coldest spot in France, and certainly well worthy of its reputation.

It stands on an elevation 3,000 feet above the sea-level. If the Lozère is aptly termed the Roof of France, then St. Chély may be

regarded as its chimney top. Summer here lasts only two months. No

wonder that the searching wind seemed as if it would blow not merely

the clothes off our shoulders, but the flesh off our bones. Yet the

people of the inn smiled and said:

"Wait here another month and you will find what we call cold!"

Doubtless to some travellers Siberian experiences on these plateaux

would be more endurable than dog days in Provence. Warned by

previous disappointment, next year I boldly confronted the latter

drawback.

From Avignon by way of Nimes, now twelve months later, with a friend

I journeyed to Le Vigan, thus making a roundabout way to the Causses

and the Tarn. Nimes in August we found hot as Cairo in May, and

thankful were we to exchange the torrid atmosphere and heavy,

sulphurous heavens for the cool air and pastoral scenery of Le Vigan.

Past olive grounds and mulberry plantations, ancient towns cresting

the hill-tops, cheerful farmeries dotted here and there—such are the

pictures descried from the railway. It was hard to pass Tarascon

without a halt, but we were too anxious to shoot the rapids for

lingerings. Ancient and curious little towns we got glimpses of on

the way, all being stoically resisted.

I had heard nothing in favour of Le Vigan. The hotel was described

to us as a fair auberge. The very place was marked down in my

itinerary simply because it seemed impossible to reach the region we

were bound for from any other starting-point. At least, the two

other alternatives had drawbacks: we must either make a circuitous

railway journey round to Mende, or a still longer detour by way of

Millau.

Having therefore expected literally nothing either in the way of

accommodation or surroundings, what was our satisfaction next day to

wake up and find ourselves in quite delightful quarters, amid

charming scenery! Our hotel, Des Voyageurs, is as unlike the

luxurious barracks of Swiss resorts as can be. An ancient,

picturesque, straggling house, brick-floored throughout, with

spacious rooms, large alcoves, outer galleries and balconies facing

the green hills, it is just the place to settle in for a summer

holiday. On the low walls of the open corridor outside our rooms are

pots of brilliant geraniums and roses; beyond the immediate premises

of the hotel is a well-kept fruit and flower garden; everywhere we

see bright blossoms and verdure, whilst the low spurs of the

Cevennes, here soft green undulations, frame in the picture.

The weather was now that of an English summer, with alternating

clouds, sunshine and fresh breezes. The inhabitants we found no less

winning than their entourage; everywhere we were

received as friends.

The Gard is foremost of all other departments in the matter of

silkworm rearing, the Ardèche alone surpassing it in the number of

silk-factories. In all the villages around Le Vigan are small

silkworm farms, the peasants rearing them on their own account, and

selling them to the manufacturers.

The workroom of a silk factory affords a curious spectacle.

At long, narrow tables, stretched from end to end of the workshop,

sit rows of girls manipulating the cocoons in bowls of hot water—in

Gibbon's phrase, "the golden tombs whence a worm emerges in the form

of a butterfly"—carefully disengaging the almost imperceptible film

of silk therein concealed, transferring it to the spinning-wheel,

where it is spun into what looks like a thread of solid gold. Throughout the vast atelier hundreds of shuttles are swiftly plied,

and on first entering the eye is dazzled with the brilliance of

these broad bands of silk, bright, lustrous, metallic, as if of

solid gold. This flash of gold is the only brightness in the place,

otherwise dull and monotonous.

Gibbon gives a splendid page on the "education of silkworms," once

considered as the labour of queens, and shows impatience with the

learnèd Salmasius, who also wrote on the subject, because, unlike

himself, he did not know everything. He tells us how two Persian

monks, long resident in China, amid their pious occupations viewed

with a curious eye the manufacture of silk; how they made the long

journey to Constantinople, imparting their knowledge of the silkworm

and its strictly guarded culture to the great Justinian; finally,

how a second time they entered China, "deceived a jealous people by

concealing the eggs of the silkworm in a hollow cane, and returned

in triumph with the spoils of the East." "I am not insensible of the

benefits of an elegant luxury," adds the historian, "yet I reflect

with some pain that if the importers of silk had introduced the art

of printing, already practised by the Chinese, the comedies of

Menander and the entire decade of Livy would have been perpetuated

in the sixth century."

So charming proved Le Vigan that we lingered on; the pleasant little

place and its people proved to us as Capua to Hannibal's soldiers,

as Circe's cup to Odysseus.

We ought not to have stayed there an unnecessary hour. We should

have continued our journey at once. On and on we lingered,

nevertheless, and when at last we braced ourselves up for an effort,

the terrible truth was broken to us. Instead of being nearer to the

goal of our wishes, we had come out of the way, and were indeed

getting farther and farther from that mysterious, so eagerly

longed-for region, the terribly unattainable Causses. Our project at

last began to wear the look of a nightmare, a harassing, feverish

dream. We seemed to be fascinated hither and thither by an ignis

fatuus, enticed into quagmires and quicksands by an altogether

illusive, mocking, malicious will-o'-the-wisp.

True, a mere matter of eighty miles lay between us and our

destination, but surely the most impracticable eighty miles out of

Arabia Petræa! We were bound for a certain little town called St.

Énimie, but between us and St. Énimie stretched a barrier,

apparently insurmountable as Dante's fog isolating Purgatory from

Paradise, or as the black river separating Pluto's domain from the

region of light. We seemed as far off the Causses as Christian from

the heavenly Jerusalem when imprisoned in Castle Doubting, or as the

Israelites from Canaan when in the wilderness of Zin.

To reach St. Énimie, then, meant two long days' drive, i. e. from

six a.m. to perhaps eight p.m., in the lightest, which stands for

the most uncomfortable, vehicle, across a country the greater part

of which is as savage as Dartmoor. Our first halting-place would be Meyrueis, and between Le Vigan and Meyrueis, relays could be had,

but at that point civilization ended. The second day's journey must

lie through a treeless, waterless, uninhabited desert; in other

words, as a glance at the map showed, we must traverse the Causse

Méjean itself.

At this stage of affairs intervened the voiturier who had just

proposed to drive us to the top of the Lozérien Helvellyn, provided

we could sit on a knifeboard. He was one of the handsomest men we

saw in these parts, which is saying a good deal. Tall, well made,

dignified, with superb features and rich colouring, it seemed a

thousand pities he should be only a carriage proprietor in this

out-of-the-way spot.

"If these ladies," he said in country fashion, thus addressing

ourselves, "will let me drive them to Millau, they can have my most

comfortable carriage, as the roads are excellent. They can sleep at

a good auberge on the way. From Millau it is only five hours by

railway to Mende, and from Mende only a four hours' drive to St.

Énimie."

Having sent on our four big trunks by diligence to Millau, in

perfect weather we set out for our first stage.

On the whole, the route now decided upon had much to recommend it,

especially to travellers unfit for excessive fatigue. The drive from

Le Vigan to Millau is thus divided into two easy stages, and the

scenery for the greater part of the way is diversified and

interesting.

Gradually winding upwards from the green hills surrounding our

favourite little town, its bright river, the Arre, playing

hide-and-seek as we go, we take a lonely road cut around barren,

rocky slopes covered with stunted foliage, here and there tiny

enclosures of corn crop or garden perched aloft.

The charm of this drive consists in the sharp contrasts presented at

unexpected turns. Now we are in a sweet, sunbright, sheltered

valley, where all is verdure and luxuriance. At every door are pink

and white oleanders in full bloom, in every garden peach-trees

showing their rich, ruby-coloured fruit, the handsome-leaved

mulberry, the silvery olive, with lovely little chestnut woods on

the heights around. Soon we seem in a wholly different latitude. The

vegetation and aspect of the country are transformed. Instead of the

vine, the peach, and the olive, we are in a region of scant

fruitage, and only the hardiest crops, apple orchards being sparsely

mingled with fields of oats and rye. And yet again we seem to be

traversing a Scotch or Yorkshire moor—so vast and lonely the

heather-clad wastes, so grey and wild the heavens.

Every zone has its wild flowers. As we go on, our eyes rest upon

white salvias, the pretty Deptford Pink, wild lavender, several

species of broom and ferns in abundance. The wild fig-tree grows

here, and the huge boulders are tapestried with box and bilberry.

One rare lovely flower I must especially mention—the exquisite,

large-leaved blue flax (Linum perenne), that shone like a

star amid the rest.

It is Sunday, and as we pass the village of Arre in its charming

valley, we meet streams of country folks dressed in their best,

enjoying a walk. No one was afield. Here, as in most other parts of

rural France, Sunday is regarded strictly as a day of rest.

After a long climb upwards, our road cut through the rock being a

grand piece of engineering, we come upon the works of a handsome

railway viaduct now in construction. This line now connects Le Vigan

with Millau and Albi, an immense boon to the inhabitants, one of the

numerous iron roads laid by the Republic in what had hitherto been

forgotten parts of France. Close to these works a magnificent

cascade is seen, sheet of glistening white spray pouring down the

dark, precipitous escarpment.

Hereabouts the barren, stony, wilderness-like country betokens the

region of the Causses. We are all this time winding round the

rampart-like walls of the great Causse de Larzac, which stretches

from Le Vigan to Millau, rising to a height of 2,624 feet above the

sea-level, and covering an area of nearly a hundred square miles. This region affords some interesting facts for evolutionists. The

aridity, the absolutely waterless condition of the Larzac, has

evolved a race of non-drinking animals. The sheep browsing on the

fragrant herbs of these plateaux have altogether unlearned the habit

of drinking, whilst the cows drink very little. The much-esteemed

Roquefort cheese is made from ewe's milk, the non-drinking ewes of

the Larzac. Is the peculiar flavour of the cheese due to the

non-drinking habit?

The desert-like tracts below this "Table de pierre," as M. Réclus

calls it, are alternated with very fairly cultivated farms. We see

rye, oats, clover, and hay in abundance, with corn ready for

garnering.

Passing St. Jean de Bruel, where all the inhabitants have turned out

to attend a neighbour's funeral, we wind down amid chestnut woods

and pastures into a lovely little valley, with the river Dourbie,

bluest of the blue, gliding through the midst. Beyound stream and

meadows rise hills crested with Scotch fir, their slopes luxuriant

with buckwheat, maize, and other crops—here and there the rich brown

loam already ploughed up for autumn sowing. Well-dressed people,

well-kept roads, neat houses, suggested peace and frugal plenty.

What a contrast did the little village of Nant present to Le Vigan!

It was like the apparition of an exquisitely-dressed, pretty girl,

after that of a slatternly beauty. Nant, "proprette," airy, well

cared for, wholesome; Le Vigan, dirty, draggle-tailed, neglected,

yet in itself possessed of quite as many natural attractions. We had

been led to expect a mere country auberge, decent shelter, no

more—perhaps even two-curtained, alcoved beds in a common

sleeping-room! What was our astonishment to find quite ideal rustic

accommodation—quarters, indeed, inviting on their own account a

lengthy stay!

A winding stone staircase led from the street to the travellers'

quarters. Kitchen, salle-à-manger and bedrooms were all spick

and span, cool and quiet; our rooms newly furnished with beds as

luxurious as those of the Grand Hotel in Paris. Marble-topped

washstands and newly-tiled floors opened on to an outer corridor,

the low walls of which were set with roses and geraniums as in

Italy. Below was a poultry yard. No other noise could disturb us but

the cackling of hens and the quacking of ducks. On the same floor

was a dining-room and the kitchen, but so far removed from us that

we were as private as in a suite of rooms at the celebrated Hôtel

Bristol.

Nant is quite a delightful townling; we only wished we could have

stayed there for weeks. It is a very ancient place, but so far

modernized as to be clean and pleasant. The quaint, stone-covered

arcades and bits of mediæval architecture invite the artist; none,

however, come!

The sky-blue Dourbie runs amid green banks below the grey peak,

rising sheer above the town: around the congeries of old-world

houses are farms, gardens and meadows, little fields being at right

angles with the streets. In the large, open market-place, where

fairs are held, just outside the town, we found a curious sight. The

corn was gathered in, and hither all the farmers round about had

brought their wheat to be threshed out by waterpower.

It is a charming drive from Nant to Millau. Our road winds round the

delicious little valley of the Dourbie, the river ever cerulean

blue, bordered with hay-fields, in which lies the fragrant crop of

autumn hay ready for carting. By the wayside are tall acacias, their

green branches tasselled with dark purple pods, or apple-trees, the

ripening fruit within reach of our hands. Little Italian-like towns,

surrounded by ochre-coloured walls, are terraced here and there on

the rich burnt-umber walls, the lime-ridges above and around taking

the form of a long lone of rampart or lofty fortress, built and

fashioned by human hands. In contrast to this savagery, we have ever

and anon before our eyes the sweet little river, no sooner lost

sight of amid willowy banks than found again.

The approach to Millau is very pretty. Almond and peach orchards,

vineyards and gardens, form a bright suburban belt. Two rivers, the

Tarn and the Dourbie, water its pleasant valley, whilst over the

town tower lofty rocks in the form of an amphitheatre. Nant may be

described as a little idyll. After it Millau comes disenchantingly

by comparison.

Never was I in such a noisy, roystering, singing, lounging place. There was no special cause for hilarity; nothing was going on; the

business of daily life seemed to be that of making a noise.

In spite of its entourage, too, the town is not engaging. Its hot,

ill-kept, malodorous streets do not call forth an exploring frame of

mind. The public garden is, however, a delightful promenade, and the

well-known photographer of these regions has his atelier in one of

the most curious old houses to be seen anywhere.

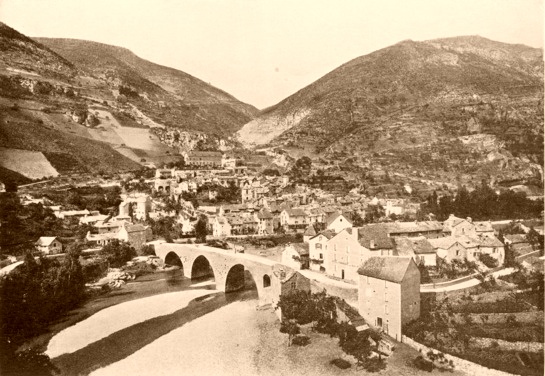

MENDE

Climbing a narrow, winding stone stair, we come upon an open court,

with balconies running round each storey, carved stone pillars

supporting these; oleanders and pomegranates in pots make the ledges

bright, whilst above the gleaming white walls shines a sky of

Oriental brilliance. The whole interior is animated. Here women sit

at their glove-making, the principal industry of the place, children

play, pet dogs and cats sun themselves; all is sunny, careless,

southern life—a page out of Graziella.

We took train to Mende. It is one of those delightfully slow trains

which enable you to see the scenery in detail, after the leisurely

fashion of Arthur Young, trotting through France on his Suffolk

mare.

Part of the way lies through a romantic bit of country

château-crowned hills follow each other in succession, every dark

crag having its feudal shell, whilst patchwork crops cover the lower

slopes.

Everywhere vineyards predominate, so persistent the faith of the

French cultivator in the vine, so touching the efforts made to

entice it to grow on French soil. Few and far between are little

wall-encompassed villages perched on the hill-tops.

At Sévérac-le-Château romance culminates in the stern,

yellowish-grey ruin cresting the green heights. A most picturesque

little place is this, seen from the railway. We now leave behind us cornlands and the vine, and reach the region of pin and fir-woods.

On the railway embankment we see the yellow-horned poppy and the

golden thistle growing in abundance; many another flower, too, as

brilliant brightens the way—a large, handsome broom, several kinds

of mullein, with fern and heather.

Bright and strongly contrasted are the hues of the landscape—purply-black

the far-off mountains, emerald-green the fields of rye and clover at

their feet. A large portion of the land hereabouts is mere

wilderness; yet the indomitable peasant wrenches up the boulders,

cleans the ground of stones, and inch by inch transforms the waste

into productive soil. At every turn we are reminded of the dictum of

"that wise and honest traveller," Arthur Young, "The magic of

property turns sands to gold."

We are now in the region of the Causses; around us rise the spurs of

Sauveterre and Sévérac. The scenery between Marvejols and Mende is

grand; sombre, deep-green valleys, shut in by wide stretches of

stupendous rocky wall, dark pine-woods, and brown wastes.

The evening closes in, and the rest is lost to us. As on my first

visit to Mende, a year ago, I again lose the romantic approach to

this wonderfully placed little city.

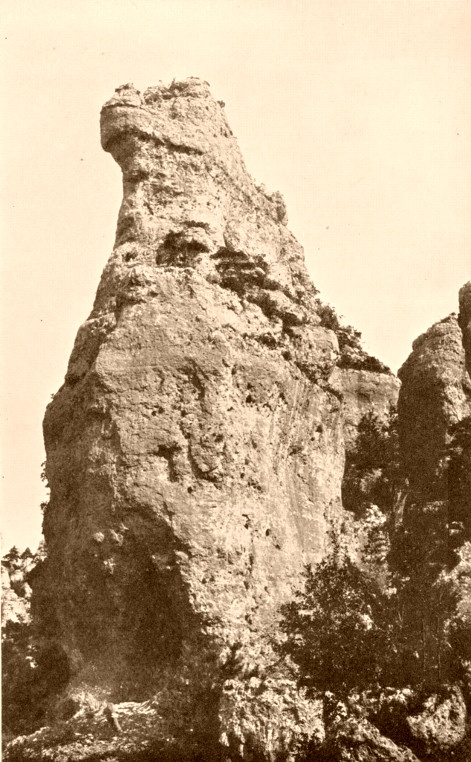

CAUSSE DE SÉVÉRAC

The Hôtel Manse, whither we now betake ourselves, is a great

improvement on that of former acquaintance in matters of situation,

sanitation, and comfort; the people are very civil and obliging in

both.

And here we were not in the very heart of the stuffy, dirty,

ill-kept town, but on the outskirts, overlooking suburban gardens

and pleasant hills, with plenty of air to breathe.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XII.

FROM MENDE TO ST. ÉNIMIE

SO, just upon

twelve months after my first attempt, I once more found myself

climbing to the summit of the lofty plateau between Mende and St.

Énimie.

It was a fortnight earlier in the year, and the weather was ideal;

light clouds that had threatened rain cleared off, mild sunshine

brightened the scene, and the air, although brisk and invigorating,

was by no means cold. Still more enticing now looked the billowy

swell of gold and purple mountains, and the dark cliffs frowning

over green valleys. To-day, too, the exhilarating conviction of

fulfilment was added to that of looking forward. A second time I had

reached the threshold of the long dreamed of region of marvels,

really to cross it and enter.

I was on my way to the Causses at last! More striking and beautiful

than when first seen now seemed the upward drive from Mende, the

beautiful grey cathedral, with its unequal spires—the one a lovely

specimen of Gothic in its late efflorescence, the other wholly

unbeautiful—cushioned against the soft green hills, the cheerful

little town in its fertile surroundings, its wild, far-stretching

waste and barren peak. More musical still sounding in my ears the

purling of the Lot, as unseen it ran between sunny pastures over its

stony bed far below.

Little I thought, indeed, although of firm intention, when making

the journey twelve months all but two weeks before, that on this 5th

of September, I should be gazing on the same scene—a scene reminding

me now, as then, of the vast reedy plateau gazed on at Saida,

dividing the Algerian traveller from the Sahara.

This time I did not stop to make tea gipsy-wise on the turf in front

of the farmhouse; nor, to my disappointment, did the children run

out to share the contents of my bonbon box. Not a soul was abroad;

an eldritch solitude reigned everywhere.

The Causse of Sauveterre is not reached till we have left the

farmhouse and ruined château far behind. From that point the roads

diverge, and we see our own wind like a ribbon till lost to view in

the grey, stony wilderness.

A considerable portion of the land hereabouts is cultivated. We see

little patches of rye, oats, Indian corn, clover, potatoes, and here

and there a peasant ploughing up the soil with oxen.

As we proceed, the enormous horizon ever widens; long shadows fleck

the purply-brown and orange-coloured undulations; scattered sparsely

are flocks of sheep, of a rich burnt-umber brown, but herbage is

scant and little cattle can be nourished here. The swelling hills

now show new and more grandiose outlines; at last we come in sight

of the dark mass of the Causse de Sauveterre, and soon we enter upon

the true Caussien landscape in all its weird and sombre grandeur. Just as when fairly out on the open sea we realize to the full its

beauty and sense of infinity, so it is here. The farther we go the

wider, more bewilderingly vast becomes the horizon: wave upon wave,

billow upon billow, now violet-hued, with a tinge of gold; now deep

brown, partly veiled with green, or roseate with sunlit clouds—the

grey monotony of stone and waste is thus varied by the way.

By the roadside slender trees of the hornbeam tribe are planted at

intervals, and where these are wanting, tall flagstaffs take their

place, to guide the wayfarer when six feet of snow cover the ground. Wild flowers in plenty brighten the edges of the road—stone crops,

cornflowers, purple lady's fingers, and many others; but wedged as

we are in our not too comfortable calèche, to get out and pluck them

is impossible.

The road from Mende to the summit of the plateau can only be

described as a vertical ascent; before beginning to descend, we have

a few kilometres of level, that is all. As we approach the village

of Sauveterre, we see one or two wild figures, shepherds, uncouth in

appearance as Greek herdsmen, and poorly dressed, but

robust-looking, well-made girls and women, short-skirted,

bare-headed, footing it bravely under the hot sun.

Portions of the land on either side consist of waste, quite recently

laid under cultivation; the huge blocks of stone had been wrenched

up, heaven knows how, and conspicuously piled up in the midst of the

newly created field—a veritable trophy! The rich red earth amply

repays these Herculean labours. With regard to the tenure of land, I

should suppose the state of things here must be very much what it

was in the age of primitive man. I fancy that any native of these

parts, any true Caussenard, has only to clear a bit of waste and

plant a crop to make it his own; a stranger would doubtless have his

right to do so contested, or, maybe, some patriarchal system still

in force, and the village community is not yet extinct in France.

"Voilà la capitale de Sauveterre!" soon cries our driver, pointing to

a cluster of bare brown, apparently windowless, houses, and a tiny

church, all grouped picturesquely together.

A poor-looking place it was enough when we obtained a nearer view,

reminding me of a Kabyle village more than anything else, not,

however, brightened with olive or fig-tree! Nothing in the shape of

a garden is to be seen, only dull walls of close-set dwellings, with

narrow paths between. Windows, however, our driver assured us, were

there; but the village is built with its back to the road.

The great privation of these poor people is that of a regular

water-supply—one large, by no means pellucid pond, with cisterns,

are all the sources they can rely upon from one end of the year to

the other; not a fountain issues from the limestone for miles round,

not a stream waters the entire Causse, a region extensive as

Dartmoor or Salisbury Plain. When we consider that this plateau has

a height above the sea-level equal to that of Skiddaw, we can easily

imagine what the long eight months' winter here is like. For the

greater part of the time the country is under several feet of snow,

and the Caussenard warms his poor tenement as best he can with peat.

It was curious to hear our conductor, himself evidently accustomed

to a hard, laborious life, speak of the inhabitants of Sauveterre. He described their condition much as a well-to-do English artisan

might speak of the half-starved foreign victims of the sweater—so

wide is the gulf dividing the Caussenard from the French peasant

proper.

"Just think of it," he said; "they don't even dress the rye for

their bread, but eat it made of husks and all. Rye-bread, bacon,

potatoes, that is their fare, and water: if it were only good water

one would have nothing to say—bad water they drink. But they are

contented, pardie."

"What do they do for a doctor?" I asked. He made a curious grimace.

"They physic themselves till they are at the point of death, and

then send for a doctor. But it is not often. They are healthy

enough, pardie!"

With regard to the ministrations of religion, they are in the

position of dalesfolk in some parts of Dauphine. A curé from St.

Énimie, he told us, performed mass once a fortnight in summer, and

came over as occasion required for baptisms, marriages, and burials. In winter, alike ordinary mass and these celebrations were stopped

by the snow. The services of the priest had then to be dispensed

with for weeks, even months, at a time.

I next tried to gain some information as to schools, but here my

informant was not very clear. Yes, he said, there was schooling in

summer; whether lay or clerical, whether the children were taught

the Catechism in their mother-tongue—in other words, the patois of

the Causse—or in French, I could not learn.

Do these wild-looking mountaineers exercise the electoral privilege? Do they go to the poll, and what are their political views? Are

their sons drafted off, as the rest of French youth, into military

service? Does a newspaper, even the ubiquitous Petit Journal,

penetrate into these solitudes? It was difficult to get a

satisfactory answer to all my questions, and quite useless to make a

tour of inquiry in the village. One must speak the patois of the Caussenard to obtain his confidence, and though the population is

inoffensive, even French tourists are advised on no account to

adventure themselves in these parts without being accompanied by a

native.

One thing is quite certain. The four thousand and odd wild,

sheepskin-wearing inhabitants of the entire region of the Gausses

must ere long, may perhaps already, be nationalized—like the Breton

and the Morvandial, undergoing a gradual and complete

transformation. Travellers of another generation on this road will

certainly not be stared at by the fierce-looking, picturesque

figures we now pass in the precincts of Sauveterre. Brigands they

might be, judging from their shaggy beards, unkempt locks, and

Robinson Crusoe-like dress; also their fixed, almost dazed, look

inspires anything but confidence. Still, we must remember that Sauveterre is in the Lozère, and that the Lozère occasionally enjoys

the enviable pre-eminence of "white assizes"—a clean bill of moral

health.

After quitting the village, which has a deserted look as of a

plague-stricken place, the road descends. We now follow the rim of a

far-stretching, tremendous ravine, its wooded sides running

perpendicularly down. For miles we drive alongside this depth, the

only protection being a stone wall not two feet high. The road,

however, is excellent, our little horses steady and sure-footed, and

our driver very careful. We are, indeed, too much interested in the

scenery to heed the frightful precipices within a few inches of our

carriage wheels. But the retrospection makes one giddy. The least

accident or mishap, contingencies not dwelt upon whilst jogging on

delightfully under a bright sky, might, or rather must, here end in

a tragedy.

By and by, the prospect becomes inexpressibly grand, till the

impression of magnificence culminates as our road begins literally

to drop down upon St. Énimie, as yet invisible. Our journey must now

be compared to the descent from cloudland in a balloon. Meantime,

the stupendous panorama of dark, superbly outlined mountain-wall

closes in. We seem to have reached the limit of the world. Before

us—Titanic rampart—rises the grand Causse Méjean, now seen for the

first time; around, fold upon fold, are the curved heights of

Sauveterre, the nearer slopes bright green with sunny patches, the

remoter purply black.

It is a wondrous spectacle—wall upon wall of lofty limestone, making

what seems an impenetrable barrier, closing around us, threatening

to shut out the very heavens; at our feet an ever-narrowing mountain

pass or valley, the shelves of the rock running vertically down.

ST. ÉNIME

When at last from our dizzy height our driver bids us look down, we

discern the grey roofs of St. Énimie wedged between the congregated

escarpments far below, the little town lying immediately under our

feet, as the streets around our St. Paul's when viewed from the

dome. We say to ourselves we can never get there. The feat of

descending those perpendicular cliffs seems impossible. It does not

do to contemplate the road we have to take, winding like a ribbon

round the upright shafts of the Causse. Follow it we must. We are

high above the inhabited world, up in the clouds; there is nothing

to do but descend as best we can; so we trust to our good driver and

steady horses, obliged to follow the sharply winding road at walking

pace. And bit by bit—how we don't know—the horizontal zigzag is

accomplished. We are down at last!

How can I describe the unimaginable picturesqueness of this little

town wedged in between the crowding hills, dropped like a pebble to

the bottom of a mountain-girt gulf?

St. Énimie has grown terrace-wise, zigzagging the steep sides of the

Causse, its quaint spire rising in the midst of rows of whitewashed

houses, with steel-grey overhanging roofs, vine-trellised balconies,

and little hanging gardens perched aloft. On all sides just outside

the town are vineyards, now golden in hue, peach-trees and

almond-groves, whilst above and far around the grey walls of the

Causse shut out all but the meridian rays of the sun.

As I write this, at six o'clock in the evening, the last crimson

flush of the setting sun lingers on the sombre, grandiose Causse

Méjean. All the rest of the scene, the lower ranges around, are in a

cool grey shadow: silvery the spire and roofs just opposite my

window, silvery the atmosphere of the entire picture. Nothing can be

more poetic in colour, form, and combination.

Close under my room are vegetable gardens and orchards, whilst in

harmony with the little town, and adding a still greater look of

old-worldness, are the arched walls of the old fortress. As evening

closes in, the fascination of the scene deepens; spire and roofs,

shadowy hill and stern mountain fastness, are all outlined in pale,

silvery tones against a pure pink and opaline sky, the greenery of

near vine and peach-tree all standing out in bold relief, blotches

of greenish gold upon a dark ground. I must describe our inn, the

most rustic we had as yet met with, nevertheless to be warmly

recommended on account of the integrity and bonhomie of the people.

Somewhat magniloquently called the Hôtel St. Jean, our hostelry is

an auberge placing two tiny bedchambers and one large and presumably

general sleeping-room at the disposal of visitors. We had, as usual,

telegraphed for two of the best rooms to be had. So the two tiny

chambers were reserved for us, the only approach to them being

through the large room outside furnished with numerous beds. The

tourist, therefore, has a choice of evils—a small inner room to

himself, looking on to the town and gardens, or a bed in the large

outer one beyond, the latter arrangement offering more liberty,

freedom of ingress and egress, but less privacy. However, the rooms

did well enough. A decent bed, a table, a chair, quiet—what does the

weary traveller want beside? Doubtless all is changed by this time.

Here, as at Le Vigan, we were received with a courteous friendliness

that made up for all shortcomings. The master, a charming old man, a

member of the town council, at once accompanied me to the

post-office, where the young lady postmistress produced letters and

papers, probably the first English newspapers ever stamped with the

mark of St. Énimie. The townsfolk stared at me in the twilight, but

without offensive curiosity. I may here give a hint to future

explorers of my own sex, that it is just as well to buy one's

travelling-dress and head-gear in France. An outlandish appearance,

sure to excite observation, is thus avoided. In the meantime the

common inquiry was put to us, "What will you have for dinner?" It

really seemed as if we only needed to ask for any imaginable dish to

get it, so rich in resources was this little larder at the world's

end. The exquisite trout of the Tarn, here called the Tar; game in

abundance and of excellent quality; a variety of fruit and

vegetables—such was the dainty fare displayed in the tiny back

parlour leading out of the kitchen.

Since this romantic, adventuresome, and costly journey made twenty

years ago, the gorge or canon of the Tarn has became a favourite

French excursion. Tourist tickets, including boats, hotels, and

guides, are issued in Paris, and conducted parties now keep the

place lively during the long vacation. At the time of my visit, the

leading men of the neighbouring villages had organized a tourist

agency, mayors, town councillors and others forming a so-called "Batellerie

de St. Jean," ensuring strangers a fixed tariff, good boats, above

all experienced boatmen, for the somewhat hazardous expedition.

Had it been somewhat earlier in the year, we might perhaps have

decided to make a little stay here. But in the height of summer the

heat is torrid on the "Roof of France," in winter the cold is

arctic, and there is no autumn in the accepted sense of the word;

winter might be already at hand. We were advised by those in whose

interest it was that we should remain, to lose no time and hurry on. Having bespoken the four relays of boatmen for next day, we betook

ourselves to our little rooms, somewhat relieved by the fact that we

were the only travellers, and that the large, general bedroom

adjoining our own would be therefore untenanted. We had reckoned

without our host, the comfortable beds therein being evidently

occupied by various members of the family when the tourist season

was slack. We were composing ourselves to sleep, each in our own

chamber, when we heard the old master and mistress of the house,

with two little grandchildren, steal up-stairs, and, quiet as mice,

betake themselves to bed. Then all was hushed for the night.

Only one sound broke the stillness. Between one and two in the

morning our driver descended from his attic. A quarter of an hour

later there was a noise of wheels, pattering hoofs and harness

bells. He had started, as he told us was his intention, on his

homeward journey, traversing the dark, solitary Causse alone, with

only his lantern to show the way. Soon after five o'clock our old

host, evidently forgetting that he had such near neighbours, or

perhaps imagining that nothing could disturb weary travellers, began

to chat with his wife, and before six, one and all of the family

party had gone down-stairs. I threw open my casement to find the

witchery of last night vanished, cold grey mist enshrouding the

delicious little picture, with its grandiose, sombre background. That clinging mist seemed of evil bodement for our expedition. Ought

we to start on a long day's river journey in such weather? Yet could

we stay?

I confess that there was something eerie in the isolation and

remoteness of St. Énimie. Compared to the savagery and desolation of

the Gausses, it was a little modern Babylon—a corner of Paris, a bit

of boulevard and bustle, but with such narrow accommodation, and

with such limited means of locomotion at disposal, the prospect of a

stay here in bad weather was, to say the least of it, disconcerting. We prepared in any case for a start, made our tea, and packed our

bags as briskly as if a bright sun were shining, which true enough

it was, although we could not see!

When, soon after seven o'clock, I descended to the kitchen, I found

our first party of boatmen busily engaged over their breakfast, and

all things in readiness for departure.

"The sun is already shining on the Causse," said our old host. "This

mist means fine weather. Trust me, ladies, you could not have a

better day."

We did our best to put faith in such felicitous augury. Punctually

at eight o'clock, accompanied by the entire household of the little Hôtel St. Jean, we descended to the landing-place, two minutes' walk

only from its doors.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XIII.

SHOOTING THE RAPIDS

AMID many cordial

adieux we took our seats, the good town councillor having placed a

well-packed basket at the bottom of the boat. Excellent little

restaurants await the traveller at the various stations on the way,

but all anxious to arrive at their journey's end in good time will

carry provisions with them.

The heavy grey mist hung about the scene for the first hour or two,

otherwise it must have been enchanting. Even the cold, monotonous

atmosphere could not destroy the grace and smilingness of the

opening stage of our journey—sweet Allegro Gracioso to be followed

by stately Andante, unimaginably captivating Capricioso to come

next—climax of the piece—the symphony closing with gentle, tender

harmonies. Thus in musical phraseology may be described the

marvellous canon or gorge of the Tarn. Quiet as the scenery is at

the beginning of the way, without any of the sublimer features to

awe us farther on, it is yet abounding in various kinds of beauty. Above the pellucid, malachite-coloured river, at first a mere narrow

ribbon ever winding and winding, rise verdant banks, tiny vineyards

planted on almost vertical slopes, apple orchards, the bright red

fruit hanging over the water's edge, whilst willows and poplars

fringe the low-lying reaches, and here and there, a pastoral group,

some little Fadette keeps watch over her goats.

The mists rise at last by slow degrees. Soon high above we see the

sun gilding the limestone peaks on either side. Very gradually the

heavens clear, till at last a blue sky and warm sunshine bring out

all the enchantment of the scene.

The river winds perpetually between bright green banks and shining

white cliffs. Occasionally we almost touch the mossy rocks of the

shore; maidenhair fern, wild evening primrose, Michaelmas daisy,

blue pimpernel and fringed gentian are so near we can almost gather

them, and so crystal-clear the untroubled waters, that every

object—cliff, tree, and mossy stone—shows its double. We might at

times fancy ourselves but a few feet from the pebbly bottom, each

stone showing its bright clear outline. The iridescence of the

rippling water over the rainbow-coloured pebbles is very lovely.

All is intensely still, only the strident cry of the cicada, or the

tinkle of a cattle-bell, and now and then the hoarse note of some

wild bird break the stillness.

Before reaching the first stage of our journey the weather had

become glorious, and exactly suited to such an expedition. The

heavens were now of deep, warm, southern blue; brilliant sunshine

lighted up gold-green vineyard, rye-field bright as emerald, apple

orchard and silvery parapet on either side.

But these glistening crags, rearing their heads towards the blue

sky, these idyllic scenes below, are only a part of what we see. Midway between the verdant reaches of this enchanting river and its sheeny cliffs, by which we glide so smoothly, rise stage upon stage

of beauty: now we see a dazzlingly white cascade tumbling over stair

after stair of rocky ledge; now we pass islets of greenery perched

half-way between river and limestone crest, with many a combe or

close-shut cleft bright with foliage running down to the water's

edge.

Little paths, laboriously cut about the sides of the Causses on

either side, lead to the hanging vineyards, fields and orchards, so

marvellously created on these airy heights, inaccessible fastnesses

of Nature. And again and again the spectator is reminded of the

axiom: "The magic of property turns sands to gold." No other agency

could have effected such miracles. Below these almost vertical

slopes, raised a few feet only above the water's edge, cabbage and

potato beds have been cultivated with equal laboriousness, the soil,

what little of soil there is, being very fertile.

On both sides we see many-tinted foliage in abundance: the

shimmering white satin-leaved aspen, the dark rich alder, the glossy

walnut, yellowing chestnut, and many others.

Few and far between are herdsmen's cottages, now perched on the

rock, now built close to the water's edge. We can see their

vine-trellised balconies and little gardens, and sometimes pet cats

run down to the water's edge to look at us.

And all this time, from the beginning of our journey to the end, the

river winds amid the great walls of the Causses—to our left the

spurs of the Causse Méjean; to our right those of Sauveterre. We are

gradually realizing the strangeness and sublimity of these bare

limestone promontories—here columns white as alabaster—a group

having all the grandeur of mountains, yet no mountains at all, their

summits vast plateaux of steppe and wilderness, their shelving sides

dipping from cloudland and desolation into fairy-like loveliness and

fertility.

St. Chély, our first stage, comes to an end in about an hour and a

half from the time of leaving St. Énimie. We now change

boatmen—punters, I should rather call them. The navigation of the

Tarn consists in skilful punting, every inch of the passage being

rendered difficult by rocks and shoals, to say nothing of the

rapids.

Here our leading punter was a cheery, friendly miller—like the host

of the hotel at St. Énimie, a municipal councillor. No better

specimen of the French peasant gradually developing into the

gentleman could be found. The freedom from coarseness or vulgarity

in these amateur boatmen of the Tarn is indeed quite remarkable.

Isolated from great social centres and influences of the outer world

as they have hitherto been, there is yet no trace either of

subservience, craftiness, or familiarity. Their frank, manly bearing

is of a piece with the integrity and openness of their dealings with

strangers.

CHÂTEAU DE LA CAZE

A charming château, most beautifully placed, adorns the banks of the

river between St. Chély and La Malène. Nowhere could be imagined a

lovelier holiday resort; no savagery in the scenes around, although

all is silent and solitary; park-like bosquets and shadows around;

below, long narrow glades leading to the water's edge.

At La Malène, reached about noon, we stop for half-an-hour, and

breakfast under the shade. Never before did cold pigeon, and

hard-boiled eggs, and household bread taste so delicious! Our bread

running short, our boatmen gave us large slices from their own loaf.

THE STONY WILDERNESS

On quitting this village, with its fairy-like dells, hanging woods,

and lawny spaces, the third and most magnificent stage of our

journey is entered upon, the first glimpse preparing us for marvels

to come. Smiling above the narrow dark openings in the rock are

vineyards of local renown. Here and there a silvery cascade flashes

in the distance; then a narrow bend of the river brings us in sight

of the frowning crag of Planiol crowned with massive ruins, the

stronghold of the sire of Montesquieu, who under Louis XIII.

arrested the progress of the rebellious Duke de Rohan.

For let it not be supposed that these solitudes have no history. We

must go much farther back than the seigneurial crusades of the great

Richelieu, or the wholesale exterminations of Merle, the Protestant

Alva or Attila, in the religious wars of the Cevennes—farther back

even than the Roman occupation of Gaul, when we would describe the

townlings of the Causses and the banks of the Tarn. Their story is

of more ancient date than any of recorded time. The very Causses,

stony, arid wildernesses, so unpropitious to human needs, so

scantily populated in our own day, were evidently inhabited from

remote antiquity. Not only have dolmens, tumuli, and bronze

implements been found hereabouts in abundance, but also

cave-dwellings and traces of the Age of Stone. Prehistoric man was

indeed more familiar with the geography of these regions than even

learnèd Frenchmen of to-day. When in 1879 a member of the French

Alpine Club asked the well-known geographer Joanne if he could give

him any information as to the Causses and the Cañon du Tarn, his

reply was the laconic:

"None whatever. Go and see."

It would take weeks, not days, to explore these scenes from the

archæological or geological point of view. I content myself with

describing what is in store for the tourist.

We now enter the defile or détroit, at which point grace and

bewitchingness are exchanged for sublimity and grandeur, and the

scenery of the Causses and the Tarn reach their acme. The river,

narrowed to a thread, winds in and out, forcing laborious way

between the lofty escarpments, all but meeting, yet one might almost

fancy only yesterday rent asunder.

LES DÉTROITS

It is as if two worlds had been violently wrenched apart, the cloven

masses rising perpendicularly from the water's edge, in some places

confronting each other, elsewhere receding, always of stupendous

proportions. What convulsive forces of Nature brought about this

severance of vast promontories that had evidently been one? By what

marvellous agency did the river force its way between? Some

cataclysmal upheaval would seem to account for such disrupture

rather than the infinitely slow processes suggested by geological

history.

Meantime, the little boat glides amid the vertical rocks—walls of

crystal spar—shutting in the river, touching as it seems the blue

heavens; peak, parapet, ramparts taking multiform hues under the

shifting clouds, now of rich amber, now dazzlingly white, now deep

purple or roseate. And every one of these lofty shafts, so majestic

of form, so varied of hue, is reflected in the transparent green

water, the reflections softening the awful grandeur of the reality. Nothing, certes, in nature can surpass this scene; no imagination

can prefigure, no pen or pencil adequately portray it. Nor can the

future fortunes of the district vulgarize it! The Tarn, by reason of

its remoteness, its inaccessibility—and, to descend to material

considerations, its expensiveness as an excursion—can never,

fortunately, become one of the cheap peep-shows of the world.

LES DÉTROITS

The intense silence heightens the impressiveness of the wonderful

hour; only the gentle ripple of the water, only the shrill note of

the cicada at intervals, breaks the stillness. We seem to have

quitted the precincts of the inhabited familiar world, our way lying

through the portals of another, such as primeval myth or fairy-tale

speak of, stupendous walls of limestone, not to be scaled by the

foot or measured by the eye, hemming in our way.

The famous Cirque des Baumes may be described as a double wall lined

with gigantic caves and grottoes. Here it is the fantastic and the

bizarre that hold the imagination captive. Fairies, but fairies of eld, of giant race, have surely been making merry here! One and all

have vanished; their vast sunlit caverns, opening sheer on to the

glassy water, remain intact; high above may their dwellings be seen,

airy open chambers under the edge of the cliffs, deep corridors

winding right through the wall of rock, vaulted arcades midway

between base and peak, whence a spring might be made into the cool

waves below. All is still on a colossal scale, but playful,

capricious, phantasmagoric.

Nor when we alight at the Pas de Soucis are these features wanting. Here the river, a narrow green ribbon, disappears altogether, its

way blocked with huge masses of rock, as of some mountain split into

fragments and hurled by gigantic hands from above.

The spectacle recalls the opening lines of the great Promethean

drama of the Greek poet. Truly we seem to have reached the limit of

the world, the rocky Scythia, the uninhabited desert! The bright

sunshine and balmy air hardly soften the unspeakable savagery and

desolation of the scene, fitting background for the tragedy of the

fallen Fire-giver.

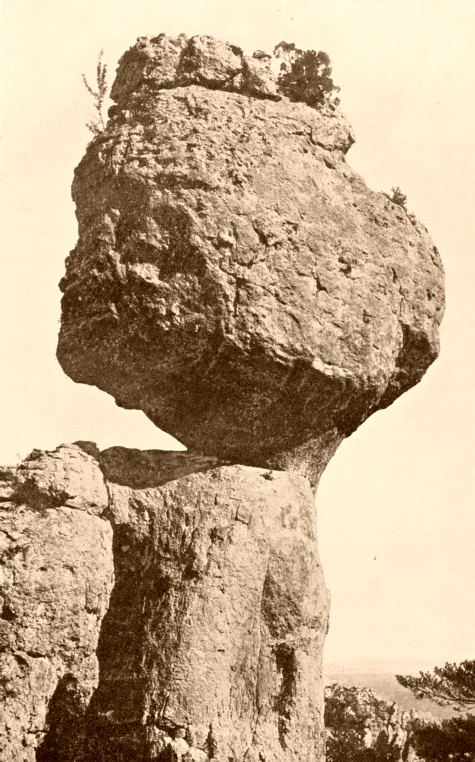

Dominating the whole, as if threatening to fall, adding chaos to

chaos, and filling up the vast chasm altogether, are two frowning

masses of rock, the one a monolith, the other a huge block. Confronting each other, tottering as it seems on their thrones, we

can fancy the profound silence broken at any moment by the crashing

thunder of their fall, only that last catastrophe needed to crown

the prevailing gloom and grandeur.

At this point we alight, our water-way being blocked for nearly a

mile. It is a charming walk to Les Vignes: to the left we have a

continuation of the rocky chaos just described, to the right a path

under the shadow of the cliffs, every rift showing maidenhair fern

and wild flowers in abundance, fragrant evening primrose, lavender,