|

PART I.

FROM PARIS TO BESANCON AND

LYONS

CHAPTER I.

THROUGH THE VALLEY OF THE MARNE TO PROVINS

NOT many

travellers on the great Mulhouse railway zigzag to the ancient

little city of Provins; none throughout that splendid hexagon called

France are worthier of a visit.

On the way thither many a village and townling offer

delightful summer retreats.

CANAL SCENE

My own rallying point was a country house at Couilly, near

Esbly, offering every opportunity of studying rural life, and

facilities for excursions by boat, diligence and railway.

Couilly is charming. The canal, winding its way between thick

lines of poplar trees towards Meaux, you may follow in the hottest

day of summer without fatigue. The river, narrow and sleepy,

yet so picturesquely curling amid green slopes and tangled woods,

affords another delicious stroll; then there are broad,

richly-wooded hills rising above these, and shady side-paths leading

from hill to valley, with alternating vineyards, orchards, pastures

and cornfields on either side. It lies in the heart of the

cheese-making country, part of the ancient province of Brie from

which this famous cheese is named.

The Comté of Brie became part of the French kingdom on the

occasion of the marriage of Jeanne of Navarre with Philip-le-Bel in

1361, and is as prosperous as it is picturesque. It also

possesses historic interest. Within a stone's throw of our

garden wall once stood a famous convent of Bernardines, called

Pont-aux-Dames. Here Madame du Barry, the favourite of Louis

XV, was exiled after his death. On the outbreak of the

Revolution, she flew to England, having first concealed, somewhere

in the Abbey grounds, a valuable case of diamonds. The

Revolution went on its way, and Madame du Barry might have ended her

unworthy career in peace had not a sudden fit of cupidity induced

her to return to Couilly when the Terror was at its acme, in quest

of her diamonds. The Committee of Public Safety got hold of

Madame du Barry, and unheroically she mounted the guillotine.

What became of the diamonds, history does not say. The Abbey

of Pont-aux-Dames has long since been turned to other purposes, but

the beautiful old-fashioned garden at the time of my visit remained

intact.

Like most of the ancient villages in the Seine et Marne,

Couilly possesses a church of an early period, though unequal in

interest to those of its neighbours. It is also full of

reminiscences of the Franco-German War. My friend's house was

occupied by the German Commandant and his staff, who, however,

committed no depredations beyond carrying off blankets and

bedquilts, a pardonable offence considering the arctic winter.

Coulommiers possesses little interest beyond its old church

and a very pretty walk by the winding river, but it is worth making

the two hours' drive across country for the sake of the scenery.

I gladly accepted a neighbour's offer of a seat in his trap, a light

spring-cart with capital horse. He was a butcher, and, like

the rest of the world here, wore the convenient and cleanly blue

cotton trousers and blue blouse of the country. The spare seat

was occupied by a notary, the two men discussing metaphysics,

literature, and the origin of all things, on their way.

We started at seven o'clock in the morning, and lovely indeed

looked the wide landscape in the tender light—valley, winding river,

and wooded ridge being soon exchanged for wide open spaces covered

with corn and root crops. Farming here is carried on

extensively, some of these rich farms numbering several hundred

acres. Farmhouses and buildings all surrounded with a high

stone wall, are few and far between, and the separate harvests cover

much larger tracts than at Couilly. It was market-day and we

passed by many farmers and farmeresses jogging to the town, the

latter in comfortable covered carts, with their fruit and

vegetables, eggs and butter.

Going to market in France means, indeed, what it did with

ourselves a hundred years ago; the farmers and farmers' wives

looking the picture of prosperity. In some cases fashion had

already so far got the better of tradition, that the reins were

handled by a smart-looking lady in hat and feathers and fashionable

dress, but for the most part by toil-embrowned, homely women, having

a coloured handkerchief twisted round their heads, and no pretension

to gentility. The men, one and all, wore blue blouses, and

were evidently accustomed to hard work, but, it was easy to see,

possessed both means and intelligence. Like the rest of the

Briard population, they are fine fellows, tall, with regular

features and frank, good-humoured countenances.

With many other towns in these parts, Coulommiers dates from

an ancient period, and long belonged to the English crown. Ravaged

during the Hundred Years' War, the religious wars, and the troubles

of the League, nothing to speak of remains of its old walls and

towers of defence. Indeed, except for the drive thither across

country, and the fruit and cheese markets, it possesses no

temptations for sojourners. Market day, however, is ever a sight for

a painter. The show of melons alone makes a subject; the

weather-beaten market-women, with gay-coloured head-gear, their blue

gowns, the delicious colour and lovely form of the fruit, all this

must be seen to be realized. Here and there were large pumpkins, cut

open to show the ripe, red pulp, with abundance of purple plums,

apples and pears just ripening, and bright yellow apricots. At

Coulommiers, as elsewhere, I looked in vain for rags, dirt, or a

sign of beggary. Every one seemed rich, independent and happy.

VALLEY OF THE MARNE

Another day we visited Meaux. The diligence passed our gate early in

the morning, in an hour and a half reaching the capital of the

ancient Brie, bishopric of the famous Bossuet, and one of the early

strongholds of the Reformation! The neighbouring country, Pays

Meldois as it is called, is one vast fruit and vegetable garden,

bringing in enormous returns. From our vantage ground—for, of

course, we were in the coupé—with delight we surveyed the

shifting landscape, wood, valley and plain, soon seeing the city

with its imposing cathedral, flashing like marble high above the

winding river and fields of green and gold on either side. I know

nothing that gives the mind an idea of fertility and wealth more

than such a scene. No wonder that the Prussians, in 1871, here

levied a heavy toll, their occupation of Meaux having cost the

inhabitants not less than a million and a half of francs. All is now

peace and prosperity, and here, as in the neighbouring towns, rags,

want and beggary are not found. The evident well-being of all

classes is delightful to behold.

Meaux, with its shady boulevards and pleasant public gardens, must

be an agreeable place to live in, nor would intellectual resources

be wanting. We strolled into the spacious town library, open, of

course, to all strangers, and could wish for no better occupation

than to con the curious old books and the manuscripts that it

contains. The Bishop's Palace is the great sight of the city. Here

have halted a long string of historic personages, Louis XVI and

Marie Antoinette when on their return from Varennes, June 24, 1791;

Napoleon in 1814; Charles X in 1828; later, General Moltke in 1870,

who said upon that occasion—

"In three days, or a week at most, we shall be in Paris," not

counting on the possibilities of a siege.

The room occupied by the unfortunate Louis XVI and his little son,

still bears the name of La Chambre du Roi. The gardens,

designed by Le Nôtre are magnificent and very quaint, as quaint and

characteristic, perhaps, as any of the same period; a broad, open,

sunny flower-garden below; above, terraced walks so shaded with

closely-planted plane-trees that the sun can hardly penetrate them

on this July day. These green walks, where the nightingale and the

oriole made music, were otherwise as quiet as the Évêché itself; but

the acme of tranquillity and solitude was only to be found in the

avenue of yews, called Bossuet's Walk. Here it is said the great

orator used to pace backwards and forwards when composing his famous

discourses.

If one of the most prosperous, Meaux is also one of the most liberal

of French cities, and has been renowned for its charity from early

times. In the thirteenth century there were no fewer than sixty Hôtels-Dieu, as well as hospitals for lepers, in the diocese, and at

the present day it is true to its ancient traditions, being

abundantly supplied with hospitals.

Half-an-hour from Meaux by railway is the pretty little town of La

Ferté-sous Jouarre, picturesquely perched on the Marne, famous for

its millstones, but not yet rendered unpoetic by the hum and bustle

of commerce.

Here again we are reminded of the terrible journey from Varennes.

In a lovely little island within bowshot of the bridge stands the

so-called Château de I'Île, a seventeenth-century manor house, much

dilapidated at the time of my visit, and with associations quite out

of keeping with its radiant surroundings.

Here on their way to Meaux, for a few hours only rested the adust-weary

and despairing travellers. The balcony used to be shown, on which

the poor little dauphin amused himself with fishing in the river

below whilst his parents reposed in an adjoining room. Portions of

the building were also open to visitors, these containing Gobelin's

tapestries, but already the château had been divided into three

tenements.

The twin town of Jouarre is reached by a beautiful drive of an hour. Ah, how happy were wayfarers in France before its grand roads—so

many boulevards when not rustic causeways—were rendered pestiferous

by the dust and odour of the motor!

Leaving the river, we ascend gradually, gaining at every step a

richer, wider prospect; below, the bright blue Marne, winding amid

green reaches; above, a ridge of wooded monticles, hamlets peeping

above golden corn and luxuriant foliage.

The love of flowers and gardens, so painfully absent in the west of

France, is here conspicuous. There are flowers everywhere, and some

of the little gardens give evidence of great skill and care. Jouarre

is perched upon an airy green height and is a quiet old-world town

with an enormous convent in the centre, where some scores of

cloistered nuns have shut themselves up for the glory of God. There,

at the time I write of, lived these Bernardines, as much in prison

as the most dangerous felons ever brought to justice; and a

prison-house, indeed, the place looked, with its high walls, bars

and bolts.

Close to this relic of the Middle Ages—maybe now vanished—is to be

seen one of the most curious monuments in this department, namely

the famous Merovingian crypt. During that régime, long

journeys were often undertaken in order to procure marbles and other

building materials for the Christian churches. Thus only can we

account for the splendid columns of jasper, porphyry, and other rare

marbles of which this crypt is composed. The capitals of white

marble, in striking contrast to the deep reds, greens, and other

colours of the columns, are richly carved with acanthus leaves,

scrolls, and other classic patterns, without doubt the whole having

originally decorated some Pagan temple. The chapel containing the

crypt is said to have been founded in the seventh century and speaks

much for the enthusiasm and artistic spirit animating its builders. There is considerable elegance in these arches, also in the

sculptured tombs of different epochs, which, like the crypt, have

been wonderfully preserved until the present time. Another archæological treasure is the so-called "Pierre des Sonneurs de

Jouarre," or Stone of the Jouarre Bell-ringers, a most quaint design

representing two bell-ringers at their task, with a legend

underneath, dating from the fourteenth century.

It must be mentioned that the traveller's patience may undergo a

trial here. When I arrived at Jouarre, M. le Curé and the sacristan

were both absent, and as no one else possessed the key of the crypt,

my chance of seeing it seemed small. However, some one obligingly

set out on a voyage of discovery, and finally the sacristan's wife

was found in a neighbouring harvest-field, and bustled up, delighted

to show everything; amongst other antiquities, some precious skulls

and bones of saints are in the sacristy, being only kept under lock

and key being exhibited on fête days.

In the Middle Ages, Jouarre possessed an important abbey, which was

destroyed during the Revolution.

This rich and important foundation, dating from the seventh century,

consisting of religious houses for both sexes, at the head of which

was ever a woman. The title of Abbess of Jouarre stood for all that

was puissant, aristocratic, distinguished and, alike from a worldly

and sacerdotal point of view, enviable. In his Drames

Philosophiques Renan thus portrays the heroine of a hideous

drama. "Ultra liberal in her views, possessed of a penetrating

intellect, saintly as her forerunners and strong in faith as they,

it was a pleasure to hear her discuss the problems of the epoch. Her

beauty, heightened by the semi-conventual costume always worn in

society, was an enchantment. Having once seen her and heard her

discourse, the desire of a second interview became a thirst, a

want, a veritable obsession." His abbess was the last, the

communities being dispersed in 1789—a second Saint Fare or Saint Bathilde who had read Voltaire and annotated Rousseau.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

PROVINS

|

"J'aime Provins ...

"Les murs déserts qu' habitent les colombes

Et dont mes pas font trembler les débris."

HÉGÉSIPPE

MOREAU. |

AIRILY,

coquettishly perched on its verdant height, still possessed of

antique stateliness, and in striking contrast with the busy, trim

little town below, mediaeval Provins captivates the beholder by

virtue of uniqueness and poetic charm. I can recall no place in my

travels at all like this little Acropolis of Brie and Champagne,

whether seen from a distance on the railway, or from the ramparts

that still encircle it as in the golden time. Provins is indeed a

gem; miniature Athens of a mediaeval princedom that, although on a

small scale, once boasted of great power and splendour; tiny Granada

of these eastern provinces, bearing ample evidence of past literary

and artistic glories.

We quit the main line at Longueville, and in a quarter of an hour

come upon a vast panorama, crowned by the towers and dome of the

still proud, defiant-looking little city, according to some writers

the Agendicum of Caesar's Commentaries, according to others, more

ancient still. It is mentioned in the capitularies of Charlemagne,

and in the Middle Ages was the important and flourishing capital of Basse Brie and residence of the Counts of Champagne. Under Thibault

VI, called Le Chansonnier, Provins reached its apogee of prosperity,

numbering at that epoch 80,000 souls. Like most numbering other

towns in these parts, it suffered greatly in the Hundred Years' War,

being taken by the English in 1432, and retaken from them in the

following year. It took part in the League, but submitted to Henry

IV in 1590, and from that time gradually declined; at present it

numbers about 7,000 inhabitants only.

The rich red rose, commonly called Provence rose, is in reality the

rose of Provins, having been introduced here by the Crusaders from

the Holy Land. Gardens of this rose may still be found at Provins,

though they are little cultivated now for commercial purpose;

Provence, the land of the Troubadours, has therefore no claim

whatever upon rose lovers, who are indebted instead to the airy

little Acropolis of Champagne. In a poem its modern poet, Hégésippe

Moreau, likens himself to "a cornflower growing amid the roses of

Provins." Thus much for the history of the place, which has been

chronicled by two gifted citizens of modern time, Opoix and

Bourquelot.

It is difficult to give any idea of the citadel, so imposingly

commanding the wide valleys and curling river at its foot. Leaving

the Ville Basse, we climb for a quarter of an hour to find all the

remarkable monuments of Provins within a stone's throw—the College,

formerly Palace of the Counts of Champagne, the imposing Tour de

César, the Basilica of St. Quiriace with its cupola, the famous

Grange aux Dîmes, the ancient fountain, lastly, the ruined city

and gates and walls, called the Ville Haute. All these are close

together, but conspicuously towering over the rest are the dome of

St. Quiriace, and the picturesque, many pinnacled stronghold

commonly known as Cæsar's Tower. These two crown, not only the

ruins, but the vast landscape, with magnificent effect; the tower

itself in reality having nothing to do with its popular name, the

stronghold was built by a Count of Champagne. It is a picturesque

object, with graceful little pinnacles connected by flying

buttresses at each corner, and pointed tower surmounting all, from

which proudly waves the Tricolour. A deaf and dumb girl led us

through a little flower-garden into the interior, and took visitors

up the winding stone staircase to the cells in which Louis d'Outremer and others are said to have been confined. For my own

part, I prefer neither to go to the top nor bottom of things,

neither to climb the Pyramids nor to penetrate into the Mammoth

caves of Kentucky. I found it much more agreeable, and much less

fatiguing, to view everything from the level, and this fine old

structure is no exception to the rule. Nothing can be more

picturesque than its appearance from the broken ground around,

above, and below, and no less imposing is the quaint, straggling,

indescribable old church of St. Quiriace close by, now a mere

patchwork of different epochs, but in the twelfth and thirteenth

centuries one of the most remarkable religious monuments in Brie and

Champagne. Here was baptized Thibault VI, the song-maker, the lover

of art, the patron of letters, and the importer into Europe of the

famous rose. Of Thibault's poetic creations an old chronicler wrote:

"C'était les plus belles chansons, les plus délectables et

mélodieuses qui oncques fussent ouises en chansons et instruments,

et il les fit écrire en la salle de Provins et en celle de Troyes."

Close to this ancient church is the former palace of Thibault, now a

secondary State school. Unfortunately, the director had gone off for

his holiday, taking the keys with him—travellers never being looked

for here—so that we could not see the interior and chapel. The

building is superbly situated, commanding from the terrace a wide

view of surrounding country. Perhaps, however, the most curious

relics of ancient Provins are the vast and handsome subterranean

chambers and passages, which are not only found in the Grange aux

Dîmes, or Tithe Barn, but also under many private dwellings of

ancient date.

Those who love to penetrate into the bowels of the earth may here

visit cave after cave, subterranean chamber after chamber; some of

these were used for the storage and introduction of supplies in time

of war and siege, others may have served as crypts, for purposes of

religious ceremony, also a harbour of refuge for priests and monks,

lastly as workshops. Provins may therefore be called not only a town

but a triple city, consisting, first, of the old; secondly, of the

new; lastly, of the underground. Enchanting from an artistic and

antiquarian point of view as are the first and last, all lovers of

progress will not fail to give some time to progress the modern

part, not omitting the walls round the ramparts, before quitting the

region of romance for plain matter of fact. At this elevation you

have unbroken solitude and a wide expanse of open country; you also

get a good idea of the commanding position of Provins.

A poetic halo still lingers round the rude times of Troubadour and

Knight. The princelings of Brie and Champagne, who lived so jollily

and regally in this capital of Provins, knew, however, how to grind

down the people to the uttermost, and levied toll upon every

imaginable pretext. The Jew had to pay them for his heresy, the

assassin for his crime, the peasant for his produce, the artisan for

his right to pursue a handicraft.

Now good feeling, peace, and prosperity prevail in this modern town,

where alike are absent signs of great wealth or great poverty. I

found myself in a region without a beggar.

Provins affords an excellent example of that spirit of

decentralization so usual in France, and unhappily so rare among

ourselves. Here in a country town, numbering between seven and eight

thousand inhabitants only, we find all the resources of a capital on

a small scale; Public Library, Museum, Theatre, learnèd societies. The Library contains some curious MSS. and valuable books. The Theatre was built by one of the richest and most generous

citizens of Provins, M. Garnier, who may be said to have consecrated

his ample fortune to the embellishment and advancement of his native

town. Space does not permit an enumeration of the various acts of

beneficence by which he has won the lasting gratitude of his

fellow-townsmen; at his death his charming villa, gardens, library,

art and scientific collections becoming the property of the town. The Rue Victor Garnier has been appropriately named after this

public-spirited citizen.

There are relics of antiquity to be found in the modern town also;

nor have I given anything like a complete account of what is to be

found in the old. No one who takes the trouble to diverge from the

beaten track in order to visit this interesting little city—Weimar

of the Troubadors—will be disappointed.

The latest poet of poetic Provins was no happy troubadour, fêted

with royal welcome from château to château; instead a second and, if

possible, unhappier Chatterton. Hégésippe Moreau, 1810-1838, ended

his twenty-eight years of foiled ambition, want and loneliness on

the bed of a public hospital. Left an orphan in early years, he

became by turns journeyman printer, school-master, and editor of

poor little newspapers. "What wanted he?" writes one of his

editors. "Daily bread and affection. A poet whom a little measure of

happiness might have changed, became the poet of hate."

Doubtless destiny was not all to blame, and in part, at least, his

life was much as he made it. Could he have trusted more to his

genius, a sure consolation had been at hand. In spite of many

imperfections, his poems in collected form have quite recently been

reprinted, whilst several lyrics are to be found in anthologies. He

loved Provins, and has musically celebrated its little river, Le Voulzie, tributary of the Seine, which "with a murmur, harmonious as

its name, flows through flowery banks."

Despair, a vindictive attitude towards existence, characterized this

nineteenth-century emulator of the troubadours, but grace and

tenderness were not lacking in his works, as the following little

poem shows:—

|

HAD I BUT KNOWN

(Si j'avais su!)

Had I but known, when day by day,

Thy childish ardour urging on,

That thou wert soon to fade away,

Books, slate, and maps aside I'd thrown.

Had I but known!

With butterfly and bird and flower

Bright as their little lives, thy own,

By thee, each radiant summer hour

Mid woodland glories should have flown.

Had I but known!

And when December, gustful, made

Through snow-tipped boughs a dreary moan,

Mid piled-up toys thou shouldst have played,

A fairy prince upon his throne.

Had I but known!

Fictive, alas! thy early bloom;

For seven short years in promise grown,

Then wert thou summoned to the tomb,

And now I sit and sigh alone.

Had I but known! |

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

TROYES AND DIJON

TROYES is rich in

antiquities, but if hotels have not improved since my own visit many

years ago, travellers would do well to crowd their sight-seeing into

a day—or, better still, see only one thing, that wholly

unforgettable. I allude to the lovely rood-screen in the church of

St. Magdalene.

The city is cheerful with decorative bits of window-garden,

abundance of flowers, hanging dormers, and much life animating its

old and new quarters. The cathedral, which rises grandly from the

monotonous fields of Champagne, just as Ely towers above the flat

plains of our eastern counties, is also seen to great advantage from

the quays; when approached you find it hemmed in with narrow

streets. Its noble towers, surmounted by airy pinnacles, and

splendid façade, delight the eye no less than the interior—gem of

purest architecture blazing from end to end with rich old stained

glass. No light here penetrates through the common medium, and the

effect is magical; the superb rose and lancet windows, not dazzling,

rather captivating the vision with the hues of the rainbow, being

made up, as it seems, with no commoner materials than sapphire,

emerald, ruby, topaz, amethyst, all these in the richest imaginable

profusion. Other interiors are more magnificent in

architectural display, none are lovelier than this, and there is

nothing to mar the general harmony, no gilding or artificial

flowers, no ecclesiastical trumpery, no meretricious decoration.

We find the glorious art of painting on glass in its perfection, and

some of the finest in the cathedral, as well as in other churches

here, are the work of a celebrated Troyen, Linard Gonthier.

A sacristan is always at hand to exhibit the treasury, worth,

so it is said, some millions of francs, and which is to be commended

to all lovers of jewels and old lace. The latter, richest old

guipure, cannot be inspected by a collector without pangs.

Such treasures as these, if not appropriated to their proper use,

namely dress and decoration, should, at least, be exhibited in the

local museum, where they might be seen and studied by the artistic.

There are dozens of yards of this matchless guipure, but, of course,

few eyes are ever rejoiced by the sight of it; and as I turned from

one treasure to another, gold and silver ecclesiastical ornaments,

carved ivory coffers, enamels, cameos, embroideries, inlaid

reliquaries and tapestries, I was reminded of a passage in Victor

Hugo's poem, Le Pape, wherein his ideal pontiff thus appeals

to the Cardinals and Bishops in conclave—

|

"Prêtres, votre richesse est un crime

flagrant,

Vos erreurs sont-ils méchants? Non, vos têtes sons dûres

Frères, j'avais aussi sur moi ce tas d'ordures,

Des perles, des onyx, des saphirs, des rubis,

Oui, j'avais sur moi, partout, sur mes habits,

Sur mon âme; mais j'ai vidé bien vîte

Chez des pauvres." |

From the art-lover's point of view, Troyes, with so many

other French towns, is all but inexhaustible. I will name only

one chef-d'œuvre more, which is a haunting beauty to me after

long years.

This is the famous jubé, or rood-loft, in the

patchwork church of St. Madeleine; rather a curtain of delicatest

lace cut out in marble, screen of transparent ivory or stalactite

roof of fairy grotto! We notice nothing else but the airy

creation, work of Juan de Gualde in the sixteenth century, and one

of the richest of the period. As we gaze, the proportions of

the interior seem to diminish, and we cannot help fancying that the

church was built for the rood-loft, rather than the rood-loft for

the church, so dwarfed is the latter by comparison. The centre

aisle is indeed bridged over by a piece of stone-carving so

exquisite in design, so graceful in detail, so airy and fanciful in

conception, that we are with difficulty brought to realize its size

and solidity. This unique rood-loft measures over six yards in

depth, is proportionately long, and is symmetrical in every part,

yet it looks as if a breath were only needed to disperse its

delicate galleries, hanging arcades, and miniature vaults, gorgeous

painted windows forming the background—jewels flashing through a

veil of guipure.

If Troyes deserves a very long chapter to itself, Dijon

merits a volume—one indeed I have oft-times longed to write.

Weeks and months, I may almost say, years, have been spent by

me in my favourite French city, my Lieblings Ort, as Germans

would say.

Leaving Dijon, historic, artistic and economic, to Murray,

Joanne and Baedeker, I will merely record a few impressions gathered

in my walks, drives and picnics. The difficulty with me in

writing of this region is to know where I should begin—and leave

off!

Michelet, who described the beauty of his countrywomen as

made up of little nothings, might have said the same of French

scenery. Sweeter spots do not lie under the sun than are to be

found in the Côte d'Or—yet how difficult, how all but impossible to

describe them! You may look in vain for a mountain; no

stupendous waterfalls magnetize travellers thither, lakes are

wanting. But subtler, rarer loveliness is to be found by those

who know in what direction to search. Behind the familiar

vine-clad hills through which the incurious traveller is whirled by

railway to French Switzerland, lie undreamed-of nooks—green,

flowery, delicious. Within a walk even of the hot, dusty

Burgundian capital, is many a cool forest resort, haunt of the

hoopoe and the oriole; blue rivers flow amid emerald holms, and

everywhere you have the sun and the vine. The chief

characteristic consists in combes or narrow winding valleys, which

are really as enticing as anything in Nature, all the more so here,

because tourists have taken the trouble to find them out!

Excepting, indeed, the unattainable Timbuctoo, or the North Pole

itself, there is no spot in the wide world where the misanthropic

Englishman would be almost certain to miss his country-folks.

What, however, would Burgundy be like without the vine?

To accustomed eyes the vine, whether growing in the plain, on rocky

hill-side, or trellised as in Italy, must ever be one of the most

beautiful things in the world. The just appreciable, yet

never-to-be-forgotten fragrance of its flowers in early summer, the

extraordinary luxuriance of its rich green waxen-like leaves, its

unrivalled fruit—alike the gold and the purple—are not more striking

than the beauty of the foliage clothing slope and ridge.

Especially on September afternoons, towards sunset, is the effect of

a vineyard unforgettable. The leaves are then interpenetrated

with warm golden light, and whilst the edges seem almost

transparent, as if transmuted into thin plates of beaten gold, all

the rest of the plant—the thousand plants between you and the

sun—are deep-hued as the purpling fruit hid in the greenery.

Where the vine ripens, skies are warm and hearts are light.

The Cote d'Or, its heights within sight of Mont Blanc, gets icy

winds from the mountain in winter, but the summer makes up for

everything. No wonder that a certain nonchalance, even mental

laziness, is imputed to the Burgundian character. Nowhere in

the world is there more jollity and open-heartedness; yet as the

famous wine of Bourgogne is none the less rich and mellow on account

of its sparkle, so the character of the people, with all its

effervescing gaiety, lacks neither depth nor solidity.

Here from my notebooks is a picture of Dijon, from its

suburban heights; the season, summer; time, early morning.

As yet day halted; pencilled in grey were the twin eminences

over against its capital. Like yet different are those nodding

hamlets: Fontaine, birth- place of St. Bernard; Talant, historic

also, each crowned by church, chateau, and clustering cottages; at

their feet, the proud city of Charles the Bold, beyond, rising with

gentle curve, the Golden Hills, vineyards famous throughout

Christendom. In the luminous eastern belt Dijon wore almost an

ethereal look, as if a brisk wind might disperse that picture in

cloudland, slate-coloured silhouette against a gradually clearing

sky. Lofty cathedral spire, slightly bent as if in perpetual

adoration, as lofty Ducal Tower with its graceful balustrade, dome,

cupola, and pinnacle, church and palace, gloomy donjon and city

gates, showed above the cincture of ramparts, all faintly outlined

on a neutral ground. Who that had never beheld a sunrising

could divine the transformation at hand? Bright and beautiful

became the panorama so lately outlined in silvery grey; the broad

band of vineyard below was soon mantled with gold, warm amber light

played upon the city walls, every cupola and spire glittered against

the rosy sky.

Far away the proud eminence of Mont Afrique, outpost of the

Golden Hills, had caught the glow, and, farther still, light vapoury

clouds, rolling off one by one, showed those matchless vineyards,

crowning pride of Burgundy, crowning joy of the world.

Not less radiant was the picture immediately under my eyes.

Those twin heights on the outskirts of the capital possessed

artificial as well as natural likeness. Furthering the work of

nature, architect and mason seemed to have kept up this similitude

of set purpose. The churches crowning each hill were built on

the same plan, with spire surmounting square tower; above sloping

green and rich foliage spread brown-roofed, white-walled hamlets.

Just now, of emerald brilliance showed the vineyards below, of

richest green the walnut and acacia groves, glistening white the

little group of buildings on either summit, tiny acropolis of

miniature kingdoms. The vastness and magnificence of the city

beyond—its noble tower, the cathedral spire, just perceptibly curved

as if in adoration, the exquisite little spire of S. Philibert, the

massive towers of St. Jean and cupolas of St. Michael, but

beautified these twin townlings by virtue of contrast. The

pair seemed to stand back modestly, pages of honour in attendance

upon sceptred monarch.

The "twisted tower" of St. Benigne mentioned by Ruskin was

replaced by another a few years ago.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER IV

ROUND ABOUT DIJON

IN the inmost

heart of a Burgundian valley, the Val Suzon, rises the Seine, and

with a good pair of horses—better still, with relays—St. Seine-sur-

l'Abbaye at the valley's close may be visited from Dijon in a day.

Here are records of more than one summer or autumn day spent

with French friends amid these enchanting scenes.

The first stage of the way in hot weather is not encouraging,

dull preface to bright pages! For upwards of an hour we follow

a monotonous suburban road. By dusty fields, barracks,

drying-grounds and market-gardens we almost on a sudden reach the

head of a spreading valley; valley within valley better describe the

shelving rocks, lawny terraces, and gold-green dingles unfolding to

view gradually, all fresh, dewy and deserted, as if now for the

first time intruded upon. The contrast was striking and

unexpected. Now, instead of glistering white ways, parched

fields, and formal alleys of plane-trees so white with dust, one

might have thought a light powdering snow had fallen, our eyes

rested on delicious coolness and greenery, and the ear was soothed

with sounds of woodland streams and babbling springs. Sweet

and pastoral as was the landscape, it had yet elements of grandeur.

Something of the ruggedness as well as the gracious smile of an

Alpine scene was here. Far away, the rocky parapets shutting

in the valley showed grandiose forms, woods of larch and pine lifted

their arrowy crests against the sky, and many a mountain stream

might be seen tumbling perpendicularly down shelving rock or green

hillside. And nowhere in the world could knolls be found

softer, turf more dazzlingly bright, rivulets more crystal clear,

richer, more umbrageous shadow. Not a trace was now left of

the flat, scorched, commonplace region just quitted. While

just before it seemed as if the plain were interminable, so

travellers might fancy now that the windings of the valley would

never come to an end either. We might well wish it to wind on

for ever, Nature here treating her worshippers as conjurors deal

with rustics at a fair, every freshly displayed marvel surpassing

the last. At each turn the valley grew fairer and fairer, and

the world seemed remoter and more forgotten.

My first visit to the Val Suzon ended at the wayside

restaurant, a picnic having been given by Dijonnais friends in my

honour. Upon the second and equally distant occasion the drive

was extended to St. Seine, where, with a friend, I breakfasted by

invitation at the little Spa, perhaps no longer existing.

Remote from the railway, offering no attractions in the shape of

theatre, baccarat-table, or concert-room, this little Burgundian

hydro had only attained local celebrity, whilst its natural charms

are such as to appeal to the few rather than the many. Hither

in the long vacation came half-a-dozen families from the dusty

capital in search of coolness and hay-scented air—a stray angler or

two for the sake of the trout-fishing—an avowed gastronome, in order

to taste the trout, and a few invalids for treatment. The

enthusiastic founder of this establishment, Dr. Guettet,

three-quarters of a century ago, purchased the beautiful abbatial

grounds and built premises, firmly believing that in the future the

little Spa would make not only his name but his fortune.

Neither renown nor wealth came, but at the time of my visit the

owner's faith remained steadfast as ever. He should wake up

one morning and find himself the creator of a second Vichy in

Bourgogne! Meantime faith, rigid economy during eight months

of the year, and a scanty handful of clients from June to September,

sufficed to keep things going. Yet another class of visitors

must be named. Adjoining the establishment which, indeed,

partly consisted of the ancient monastic buildings, stands one of

the most beautiful abbey churches of France; in such close

juxtaposition are the two, that at close of day a dreamer might

fancy the olden time come back again, and the abbey flourishing as

in the Middle Ages. Many an archæologist, and not unfrequently

an artist, would come to study this exquisite fragment of Gothic

architecture in its prime, for it can hardly be called more, time,

decay and restoration having destroyed the rest. In the dusk

of twilight, however, a delusion was possible. The grand

outline of the ancient pile rises intact and majestic against the

pale heavens, no shreds and patches of clumsy restorers there

harassed the eye as it lingered on the harmonious picture. A

fairer it were hard to find; solid grey masonry subdued to the most

delicate tints, buttress, arch and pinnacle taking hues hardly

deeper than the clear, silvery sky. Here, as elsewhere in

these regions, evenfall is often indescribably beautiful, every

object remaining luminous and definite, yet without the luminosity

and definiteness of day. The scene before us seemed cut out of

mother-of-pearl.

Glowingly also could I describe many another haunt, equally

sweet and equally hallowed by delightful memories—Bèze, with its

ancient houses, Mont Afrique, whence on clear days we can discern

Mont Blanc the chateau of Montculot, in which Lamartine penned his

famous elegy, Le Lac. To give an idea of these would

fill pages past counting. St. Jean de Losne—fully described by

me elsewhere [East o Paris]—and Seurre, both on the Saône,

should be visited as the traveller journeys to Besançon. To

resuscitate a good Sternian word, zigzaggery is the proper watchword

for travellers in France. On French soil we must diligently

imitate our neighbours and turn askance from the clock.

The approach to Seurre, of noble memory, is very beautiful.

Here are my impressions of an autumn visit.

In this favoured land harvests occur several times during the

year, crop succeeding crop from May till October. Most

beautiful is the aftermath of such a season, especially by the river

and at eventide. Serenely yet proudly, broad belt of blue

parting two golden worlds, the Saône flows amid colza fields and

meads, the vast level landscape and wide expanse of gently rippling

water imparting a sense of inexpressible repose. No gradations

of colour are here, no indistinct blendings of light and shadow; all

is clear, defined, harmonious, azure heavens, intenser azure below,

velvety green and gold around, the general brilliance subdued as

evening wears on. Hardly a breath is stirring. Bright

and lustrous as cornelian against the sky showed red and white

beeves. As the sun sank behind a ridge of poplars, bars of

solid gold seemed thrown across the lawny reaches of the river,

whilst its crystal depths took a hue of mingled rose and amber.

Economic conditions transform the French landscape oft-times

not for the better. With the golden colza crops, now

superseded, the glory of Seurre has departed. Nevertheless,

lovely views of the Saône meet us at every turn. At my

hostess's house, the river flowed under our windows!

Auxonne, another little town of the Saône valley, is not

striking as seen from the handsome bridge facing you as you quit the

railway, yet the dark grey roofs clustered round the tall church

spire, the girdle of walls, and double enceinte of ramparts

tapestried with green, make up a pretty picture. Far away

stretch the level lines of mead and colza fields, the river winding

between its banks, full and blue in spring, oft-times in summer a

mere thread of shallow water amid hot white sands. When

navigation is possible its quays present a busy scene; in autumn

corn, fruit, and neatly-cut billets of wood being packed for Paris,

the bargemen being picturesque athletes in their semi-seaman's

dress.

Auxonne is now one vast camp, and as completely fortified as

any town of the Middle Ages. It is protected by gates and a

double enceinte, the ancient earthworks intervening bright with

turf. Cannon are placed at frequent intervals, soldiers swarm

everywhere, and enormous barracks dwarf the town into

insignificance.

Fatalists might make much of the fact that Auxonne, a town

defying every attack of the Prussians in 1870-71, should be

associated with the youth of the first Napoleon. The victor of

Jena and Auerstadt spent some years of his cadetship here. In

the Saône he twice narrowly escaped drowning, and here too, as

narrowly, so the story runs, marriage with a bourgeoise maiden

called Manesca. Two ivory counters, bearing this romantic name

in Napoleon's handwriting, enrich the little museum.

Appealing more strongly to the imagination is Jouffroy's fine

statue of the modern Attila in the Place d'Armes. The figure

is that of the young soldier of the Revolution, familiar to the

Auxonnais in 1791. As yet obscure, perhaps as yet

unconsciously ambitious, his face shows rather dreamy, pensive

questioning than lust of power and glory. He seems to peer

into the future, to ask of the Fates what they have in store for

him, to strive to unriddle the mystery of the unknown. Cold,

statuesque, beautiful, the features express deep pondering and

gloomy sadness. Doubtless by the Imperialists this statue was

regarded as a palladium when the enemy thundered at the gates.

Be this as it may, no Prussian entered Auxonne to gaze on the

monument of her awful conscript!

――――♦――――

CHAPTER V.

BESANÇON AND ITS SCENERY

THE hotels at

Besançon had at one time the reputation of being the worst in all

France, but kind friends in the city would not let me try them.

I found myself, therefore, in the midst of all kinds of home

comforts, domesticities, and distractions, with delightful cicerones

in host and hostess, and charming little companions in their two

children. This is the poetry of travel; to journey from one

place to another, provided with introductory letters which open

hearts and doors at every stage, and make each the inauguration of a

new friendship. My exploration of the regions about to be

described was a succession of picnics—host, hostess, their English

guest, Swiss nurse-maid, and two little fair-haired boys, being

cosily packed in an open carriage drawn by two sturdy horses; on the

seat beside the driver, a huge basket, suggesting creature comforts,

the neck of a wine bottle, and the spout of a tea-pot being

conspicuous above the other contents. Thus I visited the

beautiful valleys of the Doubs and of the Loue, the highlands of

Franche-Comté, and the country round about Besançon. The

weather—we were in the first days of September—was perfect.

The children, aged respectively eighteen months and three years and

odd, proved the best little travellers in the world, always going to

sleep when convenient to their elders, and at other times quietly

enjoying the shifting landscape; in fact, there was nothing to mar

our enjoyment of regions as romantic as any it has been my good

fortune to enjoy. The sublime, the pastoral, mountain and

valley, vast panoramas and sylvan nooks, all are here, and at the

time I write of, for the most part untravelled.

Besançon—incidentally the birthplace of Victor Hugo—well

merits the aureole.

To obtain an idea of its superb position we must climb the height of

Notre Dame des Buis, an hour's drive from the city. From a

steep, sharp eminence covered by boxwood and crowned by a little

chapel, is obtained an excellent view of the natural and artificial

defences which render the Vesontio of Cæsar's commentaries as strong

a strategical position as any in France.

But what would the Roman chronicler of the "Oppidum maximum

Sequanorum" have said, could he have foreseen his citadel dwarfed

into insignificance by Vauban's fortifications, and what would be

Vauban's amazement could he behold the stupendous works of modern

strategists?

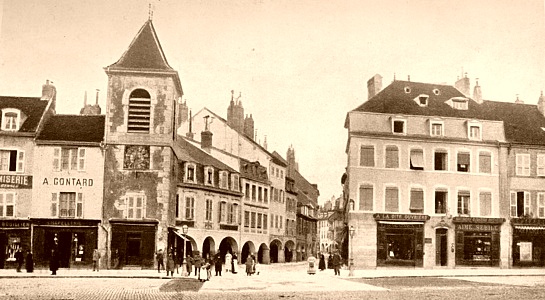

ARCHIER, BESANÇON

Beyond these proudly-cresting heights, every peak bristling with its

defiant fort, stretches a vast panorama; the mountain chains of the

Jura and the Vosges, the snow-capped Alps, the plains of Burgundy,

all these lie under our eye, clearly defined in the transparent

atmosphere of this summer afternoon. The campanula white and blue,

with abundance of deep orange potentilla and rich carmine dianthus,

were growing at our feet, with numerous other wild flowers. The

pretty pink mallow, cultivated in gardens, grows everywhere. This is

indeed a paradise for botanists, but their travels should be made

earlier in the year. The excursions, walks and drives in the

neighbourhood of Besançon are almost countless. The little valley of

the World's End, Le Bout du Monde, must on no account be

unvisited.

We follow the limpid waters of the winding Doubs; on one side

hanging vineyards and orchards, on the other lines of poplars, above

these dimpled green hills and craggy peaks are reflected in the

still, transparent water. We reach the pretty village of Beurre

after a succession of landscapes, l'un plus joli que l'autre,

as our French neighbours say, and come suddenly upon a tiny valley

shut in by lofty rocks, aptly called the World's End of these parts. Here the most adventuresome pedestrian must retrace his steps—no

possibility of scaling these mountain-walls, from which a cascade

falls so musically; no outlet from these impregnable ramparts into

the pastoral country on the other side. We must go back by the way

we have come, first having penetrated to the heart of the valley by

a winding path, and watched the silvery waters tumble down from the

grey rocks that seem to touch the blue sky overhead.

The great charm of these landscapes is the abundance of water to be

found everywhere, and no less delightful is the sight of springs,

fountains, and pumps in every village. Besançon is noted for its

handsome fountains, some of which are real works of art, but the

tiniest hamlets in the neighbourhood, and, indeed, throughout the

whole department of the Doubs, are as well supplied as the city

itself. We know what an aristocratic luxury good water is in many an

English village, and how too often the poor have no pure drinking

water within reach at all; here they have close at hand enough and

to spare of the purest and best, and not only their share of that,

but of the good things of the earth as well, a bit of vegetable and

fruit-garden, a vineyard, and, generally speaking, a little house of

their own. Here, as a rule, everybody possesses something, and the

working watchmakers have, most of them, their suburban gardens, to

which they resort on Sundays and holidays. Nothing can be more

enticing than the cottages and villas nestled so cosily along the

vine-clad hills that surround it on every side. The city is, above

all, rich in public walks and promenades, one of these, the

Promenade Chamart—a corruption of Champ de Mars—possessing some of

the finest plane-trees in Europe—a gigantic bit of forest on the

verge of this city—of wonderful beauty and stateliness. These

veteran trees vary in height from thirty to thirty-five yards. The

Promenade Micaud, so called after its originator, Mayor of Besançon

in 1842, winds along the riverside, and affords lovely views at

every turn. Then there are so-called "squares" in the heart of the

town, where military bands play twice a week, and nursemaids and

their charges spend the afternoons. Perhaps no city of its size in

all France—Besançon numbers only sixty thousand inhabitants—is

better off in this respect, whilst it is so enriched by vine clad

hills and mountains that the country peeps in everywhere.

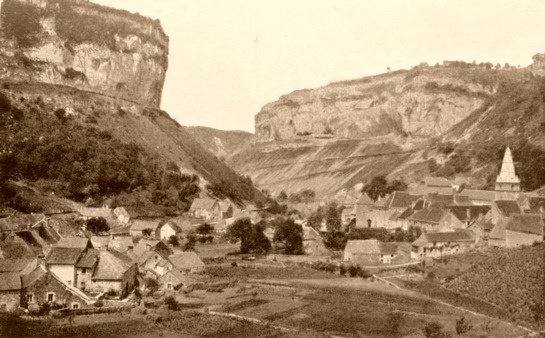

PROMENADE MICAUD

Considered from all points of view it is a very attractive place to

live in, and possesses all the resources of the capital on a small

scale; an excellent theatre, free art schools, and an academy of

arts, literary, scientific and artistic societies, museums, picture

galleries, lastly, one of the finest public libraries in France. Archæological and historic monuments—here innumerable—I leave to the

guide books.

One excursion must on no account be missed. The famous Osselle

grottoes may be reached by railway. We preferred the landau, the

lunch basket and the tea-pot, setting off early one morning in the

highest spirits. Quitting this splendid environment of Besançon, we

drove for three hours through the lovely valley of the Doubs,

delighted at every bend of the road with some new feature in the

landscape; then choosing a sheltered slope, unpacked our basket,

lunched al fresco, with the merriest spirits, and the

heartiest appetite. Never surely did the renowned Besançon pâtés

taste better, never did the wine of its warm hill-sides prove of a

pleasanter flavour! The children sported on the turf like little

Loves, the air was sweet with the perfume of new-made hay, the birds

sang overhead, and beyond our immediate pavilion of greenery, lay

the curling blue river and green hills. Leaving the babies to sleep

under the trees, and the horse to feed at a neighbouring mill—there

was no wayside inn here, so we had to beg a little hay from the

miller or farmer—we follow a little lad, provided with matches and

candles, to the entrance of the famous grottoes. Outside, the

sugar-loaf hill, so marvellously channelled and cased with

stalactite formation, has nothing remarkable—it is a mere green

height, and nothing more. Inside, however, as strange a spectacle

meets the eye as it is possible to conceive. To see these caves in

detail, you must spend an hour or two in the bowels of the earth,

but we were contented with half that time, this underground

promenade being a very chilly one. In some places we were ankle deep

in water. Each provided with a candle, we now follow our youthful

guide, who was accompanied by a dog, familiar as himself with the

windings of these sombre subterranean palaces, for palaces they

might be called. Here the stalactite roofs are lofty, there we have

to bend our heads in order to pass from one vaulted chamber to

another; now we have a superb column supporting an arch, now a

pillar in course of formation, everywhere the strangest, most

fantastic architecture, an architecture moreover that is the work of

ages; one petrifying drop after another doing its apportioned work,

column, arch, and roof being formed by a process so slow that the

life-time of a human being hardly counts in the calculation. There

is something sublime in the contemplation of this steady persistence

of Nature, this undeviating march to a goal; and as we gaze upon the

embryo stages of the petrifaction, stalagmite patiently lifting

itself upward, stalactite as patiently bending down to the remote

but inevitable union, we might almost fancy them sentient agents in

the marvellous transformation. The stamens of a passion-flower do

not more eagerly, as it seems, coil upwards to embrace the pistil;

the beautiful flower of the Vallisneria spiralis more

determinately seek its mate than these crystal pendants covet union

with their fellows below. Such perpetual bridals are accomplished

after countless cycles of time, whilst meantime, in the sun-lit

world outside, the faces of whole continents are being changed, and

entire civilizations are formed and overthrown!

The feeble light projected by our four candles in these gloomy yet

majestic chambers was not so feeble as to obscure the names of

hundreds of individuals scrawled here and there. Schopenhauer is at

pains philosophically to explain the foolish propensity of

travellers to perpetuate their names, or as it so seems to them. The

Pyramids or Kentucky Caves do not impress their minds at all, but to

see their own illustrious John Brown and Tom Smith cut upon them,

does seem a very interesting and important fact!

The bones of the cave bear and other gigantic animals have been

found here; but the principal tenants of these antique vaults are

now the bats, forming huge black clusters in the roof. There is

something eerie in their cries, but they are more alarmed than

alarming; the lights disturbing them not a little.

Pleasant after even this short adventure into the regions of the

nether world, was the return to sunshine, green trees, the children,

and the tea-pot! After calling it into requisition, we set off

homewards, reaching Besançon just as the moon made its appearance, a

large silver disc above the purple hills.

In showery days, delightful hours may be spent in the Public

Library, which is also a museum. Here are busts, portraits and

relics of such noble Franc-Comtois as Cuvier, whose brain weighed

more than that of any human being ever known; Victor Hugo, a name

for all time; Fourier, who saw in the Phalanstery, or, Associated

Home, a remedy for the crying social evils of the age, and who, in

spite of many aberrations, is entitled to the gratitude of mankind

for his efforts on behalf of education, and the elevation of the

laborious classes; Proudhon, whose famous dictum, La propriété

c'est le vol, has become the watchword of a certain school of

Socialists; Charles Nodier, who, at the age of twenty-one, was the

author of the first satire ever published against the first

Napoleon, La Napoléons, which formulated the battle-cry of

the Republican party; besides these, a noble roll-call of artists,

authors, savants, soldiers, and men of science.

Noteworthy in this treasure-house of Franc-Comtois history is the

fine marble statue of Jouffroy by Pradier. Jouffroy, of whom his

native province may well be proud, disputes with Fulton the honour

of first having applied steam to the purposes of navigation. His

efforts, made on the river Doubs and the Saône in 1776 and 1783,

failed for the want of means to carry out his ideas in full, but the

Academy of Science acknowledged his claim to the discovery in 1840.

The collection of works on art, architecture, and archæology

bequeathed to the city by Pierre And en Paris, architect and

designer to Louis XVI, is a very rich one, and there is also a

cabinet of medals numbering ten thousand pieces.

Besançon also boasts of several learned societies, the first of

which, founded in the interests of scientific inquiry, dates from

1840. One of the most interesting features in the ancient city is

its connection with Spain, and what has been termed the golden age

of Franche-Comté under the Emperor Charles the Fifth. Franche-Comté

formed a part of the dowry of Margaret, daughter of the Emperor

Maximilian of Austria, and it was under her protectorate during her

life-time and reverted to her nephew Charles the Fifth on his

accession to the crowns of Spain, Austria, the Low Countries, and

Burgundy. His minister, Perrenot de Granvelle, born at Ornans,

infused new intellectual and artistic life into the place he ruled

as a prince. His stately Italian palace, still one of the handsomest

monuments of Besançon, was filled with pictures, statues, books, and

precious manuscripts, and the stimulus thus given to literature and

the fine arts was followed by a goodly array of artists, thinkers,

and writers. The learnèd Gilbert Cousin, secretary of Erasmus,

Prevost, pupil of Raffaelle, Goudinel of Besançon, the master of

Palestrina, creator of popular music, the lettered family of

Chifflet, and many others, shed lustre on this splendid period;

while not only Besançon but Lons-le-Saunier, Arbois, and other small

towns bear evidence of Spanish influence on architecture and the

arts. In the most out-of-the-way places may be found chefs-d'œuvre

dating-from the protectorate of Margaret and the Emperor; such

treasure-trove makes travelling in Franche-Comte so fruitful to the

art-lover in various fields.

A mediæval writer, Francois de Belleforest, thus describes

Besancon:—

"Si par l'antiquité, continuée en grandeur, la bénédiction de Dieu

se cognoit en une lieu, il n'y a ville ni cité en toutes les Gaules

qui ayt plus grande occasion de remarquer la faveur de Dieu, en soy

que la cité dont nous avions prise le discours. Car, en

premier lieu, elle est assise en aussi bonne et riche assiette que

ville du monde; estant entourée de riches costeaux et vignobles, et

de belles et hautes fôrets, ayant la rivière du Doux qui passe par

le millieu, et enclost pour le plupart d'icelle, estant bien,

d'ailleurs fort bien approvisionée."

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VI.

THE VALLEY OF THE LOUE

LET the traveller

now follow me to Ornans, Courbet's birth and favourite

abiding-place, and the lovely Valley of the Loue. This is the

excursion par excellence from Besançon, and may be made in

two ways, either on foot, occupying three or four days, decidedly

the most advantageous for those who can do it, or by carriage in a

single day, starting very early in the morning, and telegraphing for

relays at Ornans the previous afternoon. This is how we managed it,

starting at five, and reaching home soon after eight at night. The

children accompanied us, and I must say, better fellow-travellers I

never had than these mites of eighteen months and three and a half

years. When tired of looking at the cows, oxen, goats, horses,

poultry we passed on the road, they would amuse themselves for an

hour by quietly munching a roll, and, when that occupation at last

came to an end, they would go to sleep, waking up just as happy as

before.

Ornans is not only extremely picturesque in itself, but interesting

as the birth and favourite abiding place of the famous painter

Courbet; it is also a starting-place for the Valley of the Loue, and

the source of this beautiful little river, the last only to be seen

in fine, dry weather, on account of the steepness and slipperiness

of the road. The climate of Franche-Comté is unfortunately

very much like our own, being excessively changeable, rainy, blowy,

sunny, all in a breath. To-day's unclouded sunshine is no

guarantee of fine weather to-morrow, and although, as a rule,

September is the finest month of the year here, it was very variable

during my stay, with alternations of rain and chilliness. Fine

days had to be waited for and seized upon with avidity, whilst the

temperature is liable to great and sudden variations.

We reach Ornans after a drive of three hours, amid hills

luxuriantly draped with vines and craggy peaks clothed with verdure,

here and there wide stretches of velvety pasture with cattle

feeding, and haymakers turning over the autumn hay. Everywhere

we find these at work, and picturesque figures they are.

Ornans is lovely, and no wonder that Courbet was fond of it.

Nestled in a deep valley of green rocks and vineyards, and built on

the banks of the transparent Loue, its quaint spire rising from the

midst, the place commends itself alike to artist, naturalist, and

angler. The old-world houses reflected in the river are

marvellously paintable, and the scene, as we saw it after a heavy

rain, glowed in the brightest and warmest light.

Courbet's house is situated by the roadside, on the outskirts

of the town, fronting the river and the bright green terraced hills

above. It is a low, one-storied house, embosomed in greenery,

very rural, pretty, and artistic. In the dining-room we were

shown a small statue of the painter by his own hand, giving one

rather the idea of a country squire or sporting farmer than a great

artist, and his house—which is not shown to strangers—is full of

interesting reminiscences of its owner. In the kitchen is a

splendid Renaissance chimney-piece of sculptured marble. This

treasure Courbet found in some old château near, and, artist-like,

transferred it to his cottage before he helped to overthrow the

Vendôme Column, and thus forfeited the good feeling of his

fellow-townsmen. After that unfortunate affair, an exquisite

statue, with which he had decorated the public fountain, was thrown

down, at clerical instigation. Morteau, to be described

further on, being more enlightened, rescued the dishonoured statue,

and it now adorns the public fountain of that village. It is,

indeed, impossible to give any idea of the vindictive spirit with

which Courbet was treated by his native village, and it must have

galled him deeply. We were allowed to wander at will over the

house and straggling gardens, having friends in the present

occupants, but at the time it belonged to the Courbet family, and

was not otherwise to be seen.

All this while I was listening, with no little edification,

to the remarks of our young driver, who took the keenest interest in

Courbet and art generally. He told me, as an instance of the

strong feeling existing against Courbet after the events of the

Commune, that, upon one occasion when the painter had been drinking

a toast with a friend in a cafe, he had no sooner quitted the place

than a young officer sprang up and dashed the polluted glass to the

ground, shattering it into a dozen pieces. "No one shall

henceforth drink out of a glass used by that man," he said, and

doubtless he was only echoing the popular sentiment.

Ornans is the birthplace of the princely Perronet de

Granvelle, father of the Cardinal whose portrait by Titian adorns

the picture gallery of Besançon, and whose munificent patronage of

arts and letters turned that city into a little Florence during the

Spanish régime. In the church is seen the plain red

marble sarcophagus of his parents, also a carved reading desk and

several pictures presented to the church by his son, the Cardinal.

There is a curious old Spanish house in the town, relic of the same

epoch. Ornans is celebrated for its cherry orchards and

fabrications of Kirsch, also for absinthe, and its wines.

Everywhere you see cherry orchards and artificial terraces for the

vines as on the Rhine, not a ledge of hill-side being wasted.

Gruyere cheese, so called, is also made here, and there are besides

several manufactures, nail-forges, wire-drawing mills, and

tile-kilns. But none of these interfere with the pastoralness

of the scenery. Lovely walks and drives abound, and the

magnificence of the forest trees has been made familiar to us by the

landscapes of Courbet, whose name will ever be associated with the

Valley of the Loue.

We were now on the high road from Ornans to Pontarlier, and were

passing some of the wealthiest little communities in Franche-Comté,

Montgesoye, Villafuans, Lods, all most picturesque to behold, and

important centres of industry. As we proceed further on the Mouthier

road, the aspect changes, and we find ourselves in the winding

close-shut valley, a narrow turbulent little stream of deepest green

tossing over its rocky bed amid hanging vineyards and lofty cliffs. Soon, however, the vine, oak, beech, and ash tree disappear, and we

have instead sombre pine and fir only.

Mouthier is perched on a hill-side amid grandiose mountains, and is

hardly less picturesque than Ornans, though not nearly so enticing. In fact we found it dingy when visited in detail, though charming

viewed from the high road above. Here we sat down to an excellent

dinner at one end of the salle-à-manger; at the other being a

long table where a number of peasant farmers, carters, and

graziers—it was market day—were faring equally well: our driver was

amongst them, and all were as quiet and well-behaved as possible. The charges were very low, the food good, the wine sour as vinegar,

and the people obliging in the extreme.

After having halted to look at the beautiful old wood-carvings in

the church, we continued our way, climbing the mountain road towards

Pontarlier; hardly knowing which to admire most, the deep-lying

valley at our feet, through which the little imprisoned river curls

with a noise as of thunder, making miniature cascades at every step,

or the limestone rocks of majestic shape towering above on the other

side. One of these, the so-called Roche de Hautepierre, is

double the height of the Great Pyramid; the road all the time

zigzagging wonderfully around the mountain sides—a stupendous piece

of engineering which cost the originator his life. Soon after

passing the tunnel cut in the rock, we saw an inscription telling

how this engineer, while engaged in taking his measurements, lost

his footing and was precipitated into the awful ravine below. The

road itself was opened in 1845, and is mainly due to the public

spirit of the inhabitants of Ornans.

Franche-Comté is rich in mountain roads, and none are more wonderful

than this. As we crawl at a snail's pace between rocks and ravine,

silvery grey masses towering against the glowing purple sky, deepest

green fastnesses below that make us giddy to behold, all is still

but for the sea-like roar of the little river as it pours down

impetuously from its mountain home. The heavy rain of the night

before unfortunately prevented us from reaching the source, a

delightful excursion in tolerably dry weather, but impracticable

after a rainfall. Between Mouthier and the source of the Loue is a

bit of wild romantic scenery known as the, Combos de Nouaille,

home of the Franc-Comtois elf, or fairy, called la Vouivre.

Combe means a straight, narrow valley lying between two

mountains, and Charles Nodier remarks: "is very French, and

perfectly intelligible in any part of the country, but has been

omitted in the Dictionary of the Academy, because there is no

combe at the Tuileries, the Champs Elysées or the Luxembourg!"

These close winding valleys form one of the most characteristic and

picturesque features of Franc-Comtois scenery. Leaving the more

adventuresome part of this journey therefore to travellers luckier

in respect of weather than ourselves, we turned our horses' heads

towards Ornans, where we rested, a second time, for coffee and a

little chat with friends. As we set out for Besançon, a splendid

glow of sunset lit up Courbet's home, clothing in richest gold the

hills and hanging woods he portrayed with so much vigour and poetic

feeling. The glories of the sinking sun lingered long, and, when the

last crimson ray faded, a full pearly moon rose in the clear

heavens, lighting us on our way.

A few days after this delightful excursion, I left Besançon amid the

heartiest leave-takings, and the last recollection I brought away

from the venerable town is of two little fair-haired boys, whose

faces were lifted to mine for a farewell kiss in the railway

station.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VII.

THE HIGHLANDS OF THE DOUBS

THE picturesque

and most historic little Protestant town of Montbéliard, reached in

two hours from Besançon, and in which I once spent many pleasant

days with French friends, need not detain the traveller. But

here, willy nilly, he must halt in order to visit the magnificent

scenery of the Doubs.

The railway through this romantic region had not been

constructed at the time of my own trip, made by carriage, myself

having for companion the widow of a French officer. The only fault

of the lady was that she never could be brought to grumble. Unpunctuality, dirt, noise, discomfort left her absolutely unmoved. The pleasure of travel atoned for all shortcomings.

Our little calèche and horse left much to desire, but the good

qualities of our driver made up for everything. He was a fine old

man, with a face worthy of a Roman Emperor, and, having driven all

over the country for thirty years, knew it well, and found friends

everywhere. Although wearing a blue cotton blouse, he was in the

best sense of the word a gentleman, but we were somewhat astonished

to find him seated opposite to us at our first table d'hôte

breakfast. We soon saw that he well deserved the respect shown him;

quiet, polite, dignified, he was the last person in the world to

abuse his privileges, never dreaming of familiarity. The extreme

politeness shown towards the working classes here by all in a

superior social station doubtless accounts for the good manners we

find among them. My fellow-traveller never dreamed of accosting our

good Eugène without the preliminary Monsieur, and did not feel

herself at all aggrieved at having him for her vis-à-vis at

meals. Eugène, like the greater number of his fellow-countrymen, is

proud and economical, and, in order not to become dependent upon his

children or charity in his old age, had already with his savings

bought a house and garden.

Soon after quitting Montbéliard we began to ascend, and for the rest

of the day were gradually exchanging the region of corn-fields and

vineyards for that of the pine. From Montbéliard to St. Hippolyte is

a superb drive of about five hours, amid wild gorges, grandiose

rocks that have taken every imaginable form—rampart, citadel,

fortress, tower, all trellised and tasselled with the brightest

green; and narrow mountains, valleys—delicious little emerald oases

shut in by towering heights on every side. The mingled wildness and

beauty of the scenery reached their culminating point at St.

Hippolyte, a pretty little town with picturesque church, superbly

situated at the foot of three mountain gorges and the confluence of

the Doubs with the Dessoubre, the latter river turning off in the

direction of Fuans. Here we halt for breakfast, and in two hours'

time are again ascending, looking down from a tremendous height at

the town, incomparably situated in the very heart of these solitary

passes and ravines. Our road is a wonderful bit of achievement,

curling as it does around what below appear unapproachable

precipices. This famous road was constructed with many others in

Louis Philippe's time, and must have done great things for the

progress of the country. Excepting an isolated little château here

and there, and an occasional diligence and band of cantonniers, all

is solitary, and the solitariness and grandeur increase as we

leave the region of rocks and ravines to enter the pine

forests—still getting higher and higher. From St. Hippolyte to our

next halting-place, Maîche, the road only quits one pine-wood to

enter another, our way now being perfectly solitary, no herdsman's

hut in sight, no sound of bird or animal, nothing to break the

silence. Some of these trees are of enormous height—their sombre

foliage at this season of the year being relieved by an abundance of

light brown cones, so many gigantic Christmas trees hung with golden

gifts. Glorious as is the scenery we had lately passed, hoary rocks

clothed with richest green, verdant slopes, valleys, and mountain

sides all glowing in the sunshine—the majestic gloom and isolation

of these fastnesses appeal more to the imagination. Next to the sea,

the pine-forest, to my thinking, is the sublimest of nature's

handiworks. Nothing can lessen, nothing can enlarge such grandeur as

we have here. Sea and pine-forest are the same, alike in

thunder-cloud or under a serene sky—summer and winter, lightning and

rain—we can hardly add by a hairbreadth to the impression they

produce.

Maîche might conveniently be made a summer resort, and I can fancy

nothing healthier and pleasanter than such a sojourn around these

fragrant pines. The hotel, too, pleased us greatly, and the

landlady, like most of the people we have to do with in these parts,

was all kindness, obligingness, and good-nature. In large cities and

cosmopolitan hotels, a traveller is Number one, two, or three, as

the case may be, and nothing more. Here, host and hostess interest

themselves in all their visitors, and regard them as human beings. The charges moreover were so trifling that, in undertaking a journey

of this kind, hotel expenses need hardly count at all—the real cost

was the carriage.

From Maîche to Le Russey, our halting-place for the night, is a