|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XIV

BILLY STIFF AWAKENS

THE sultry summer

evening upon which she went to fetch Thomasina Twigg proved to be

one of the most important in Dolly Wenyon's life; not for any one

outstanding circumstance that distinguished it, but from a

succession of small events and impressions all pointing one way, and

all giving shape and distinctness to one idea. Billy Stiff,

though only a poor, drunken tramp, had piqued her curiosity and

excited all the interest of her fresh, rustic young nature by his

fantastic manners and his absurd air of exaggerated gallantry;

whilst his impulsive and beautiful heroism in saving her life at the

risk of his own, and with such painful consequences to himself, had

suddenly made him a hero indeed in her eyes, his bravery being all

the more beautiful by contrast with his almost imbecile

wretchedness. What she had seen and heard at the tollhouse had

deepened these feelings, and, following the pure impulses of her own

tender womanhood, she had suddenly become as enthusiastic for his

reclamation as either Jeff or his wife. All these feelings

were heightened more than she was aware by the mystery surrounding

the poor fellow's personality.

Dolly despised a drunkard, but what had happened made it for

ever impossible for her to despise Billy; and if he should turn out

to be some noble nature ruined by this one dreadful besetment,

nothing could be more delightful than to assist in any way, however

small, in his rescue. She was young and hopeful, and the

experiences of the day seemed to have all been sent to deepen her

interest and intensify her concern for the suffering invalid.

Noticing, as she entered the inn, that the parlour door was

half open, she glanced in with the intention of speaking with her

father, and almost instantly drew back with a little cry and hurried

on; for there, sitting close to her father and engaged in earnest,

low-voiced conversation, sat Simpson Crouch. Her first impulse

was to burst in upon them and let her parent know what manner of man

this was in whom he was thus confiding, and what insulting language

he had used about him. Checking herself, however, she hurried

upstairs to take off her things and collect her thoughts. As

she stood thus, touching up her hair before the glass, her mother

came into the room, carefully closing the door after her. She

looked a little red and flurried, but there was the same air of

resolution and confidence about her as she had worn ever since she

took charge of her patient.

"Thank goodness he's gone, and good riddance to him."

"Gone? Who? Not the poor—"

"Him? No! He won't go, bless thee. I'll

show him."

"But, mother, what is Simpson doing—"

"T' doctor looked at his body—bless thee, girl, it was as

white as a baby's, and that pitiful thin—then he ups an' he glares

at me fit to sting me, an' he shouts, 'This is no tramp! This

is a gentleman,' he says. 'Send for his friends,' he says."

"'We don't know nothin' about him,' I says."

"'Find out, then,' he says, 'an' sharp,' he says.

'Somebody knows. Find his friends, an' send for 'em at once'

he says; an' off he bounces, muttering all t' way downstairs."

Mrs Wenyon, breathless with her headlong recital, and still boiling

over with outraged indignation, paused a moment to recover herself;

and Dolly was just commencing, "But, mother—" when the old lady

burst out again—

"We knew 'at Jeff and 'Siná knew nothin', and so your father

bethinks him of Simpson, an' sends for him. But that's nearly an

hour sin'. Haven't they done their gabbling—Eh? Yes, I'm here,

Miriam," and away hurried the important old lady to her charge.

Dolly stood thinking: the condition of the patient was infinitely

more interesting than Simpson and his doings, and so, in a moment or

two, she was lost in profound reflection. Why, now that she

remembered, 'Siná had referred on their way from the tollhouse to

Billy's ridiculous fastidiousness in matters of personal

cleanliness, and his curious habit of going for days without washing

whilst in drink, and then slopping all over the scullery floor in

his constant tubbings when sober. And all at once the maiden's

romantic fancy took fire. This was no fallen tradesman or clerk; he

was a disguised nobleman, such as the stories all told about—an

aristocrat who had been robbed of his rights by unprincipled

relatives and driven to drink by his many misfortunes. Dolly

thrilled—but there was someone coming; she could hear a hand

groping for the latch—the King's Arms was too old-fashioned to have

knobs.

Then the door opened slyly, and Miriam, with face of portentous

secrecy, stepped on tiptoes into the room, drawing something out of

her pocket as she did so.

"I took it out of his breast myself when I was a undressing of him. It was lying close next to his poor heart," and slipping a little

crumpled bit of paper into Dolly's hands, the maid puckered up her

face into inscrutable signals of gave a series of warning nods,

and then, with a subdued "Yes! Coming!" in response to a soft call

from outside, carefully closed the door and vanished. Dolly held the

packet in her hand, looked hard at it, and sighed. Then she slowly

changed it from one palm to the other and stared at it with

hypnotised intensity. She was about to open it, and then stopped. No, no! this crumpled thing, dingy and worthless though it looked,

contained this stranger's secret; who was she to pry into it? She

heaved another great long sigh, looked longingly at the paper,

essayed again to know its contents. No! It was his secret, and even

if he died—if he died? Why, nobody knew who he was; this might give

the information. But the very strength of her desire alarmed and

ashamed her; she would keep it carefully, and if he recovered—but

the doctor had said he would not recover, and that his friends were

to be communicated with. And so gently, and with wavering slowness,

she turned back the cover of the little parcel and beheld—a little

piece of her own best frock.

For a moment or two astonishment was the predominant feeling within

her; then perplexity as to how the little fragment could have got

into such hands; and then a slow, timid blush, growing deeper and

hotter every moment, stole up her neck and into her face, until

every line of her countenance was rose-red with embarrassment, half

painful, half pleasant.

This, then, was why Miriam had been so very mysterious; she had

opened the scrap and guessed its queer little secret. The odd little

sentences which 'Siná had quoted to her in which Billy had babbled

of a garden queen came back into her mind; every detail of her one

interview with him, the passing glimpse of his face as she hurried

out of Simpson's office, returned vividly to her, and all these,

appealing as they did to her susceptible heart, moved her very soul,

and coloured with loveliest tints that made it for ever beautiful

his one little momentary heroism. Dolly had all a woman's delight of

love, all a woman's delight in being singled out as the object of

supreme affection even by the most abject and impossible of mortals;

and at that moment every other thought was suffused with the glow of

a great sweet wonder, that this crazy, drink-sodden wretch was

capable even yet of a pure human love. It was so beautiful, so

infinitely touching and pitiful, that in that melting moment poor

drink-cursed Billy seemed a hero, and his love all the more rare and

divine when found in so utterly ruined a heart. A long, quivering

sigh escaped her lips, her eyes shone with tender holy light that

was quenched instantly in tears. This simple maid knew nothing of

introspection, she never paused to ask herself how much of her

delight arose from the fact that the love she was glorying in was

love to her; it was there, a thing to rejoice in for its own sweet

sake; there was suggestion in it, promise in it, and wonderful

possibility in it; and as every real woman is a born reclaimer and

saviour, there came out of that struggle the hope that Stiff would

not die, that body and soul alike might be recovered, and that

Billy, reclaimed and restored, would be a man once more. Thus in

that moment the maid became a woman and gave her soul to love's

sweetest saddest illusion, and embarked upon love's dearest and most

disappointing experiment, the salvation of a man by love.

.

.

.

.

Nobody went to bed that night at the King's Arms; the very

atmosphere, sultry and heavy, seemed to have a portent in it;

everybody went about with soft steps and spoke in subdued tones. The

interview between Phineas and Simpson lasted a long time; and when

at last it was over, the ex-cooper, after inquiring about the

condition of the patient, moved about the house with a strange

restlessness, unable to settle down anywhere, and yet gruffly

refusing to go to bed. Dolly, excluded by her age and sex from the

sick-room, haunted the staircase like a shadow, and cross-questioned

with almost jealous exactitude every one who came out from the

presence of the sick one. About midnight the sufferer was said to

be showing signs of returning consciousness, but an hour later the

only answer Dolly could get to her inquiries was a solemn shake of

the head. At about two o'clock 'Siná, emerging from the sick-room,

drew her favourite girl into a room where there was a clock and

grimly announced, "It 'ull be sattl'd one road or t' other afore

that strikes three." Dolly tried to question her old friend, but

'Siná had all the importance of mystery upon her, and retired again

to the nursing chamber. Dolly, resolved to be resigned, had a little

cry and said she was resigned; all the same she was ever on the

staircase, moving quietly about in the passage, or listening with

restrained breath at the bedroom door. Again and again she went to

look at the clock. Twenty past, half-past, ten to three, but all was

still in the sick-chamber. The clock struck. Phineas, who was with

her at the moment, consulted his heavy fob-watch; Dolly looked first

at one drowsy-eyed maid and then at another, and presently, unable

to rest longer, began to creep towards the fatal chamber. There was

not a sound, not a breath to be heard. A soul was perhaps at that

moment passing, all unready, to its great account, but passing by a

deed that had served—

"Beware of Bobbins!"

The voice was deep, sepulchral, or at least in the silent midnight

sounded so.

Dolly shivered. Was it some last warning, some message which the

light of another world suggested—

"Bobbins!"

There was a sound of stealthy moving, a chorus of soft whispers, a

creaking of the bed, and then a loud, eager craving, "Drink!—a drop!

a drop!—Bobbins, beware of Bobbins!" and the terrified girl fled to

her room and buried her shuddering form under the bedclothes.

CHAPTER XV

A WALK TO THE TOLLHOUSE

DOLLY'S bedroom adjoined

the spare-room in which poor Billy Stiff was lying, and the

momentary sounds which came from the latter apartment gradually died

away and all was still again. The hours wore slowly by, and

the laggard dawn was long a-coming. By daylight, the household

was made aware that the patient was at anyrate no worse, and Mrs

Wenyon when she appeared looked placid and confident. That day

passed, and the next, and though the doctor was persistent in his

forebodings, the patient still lingered; and by this time, little

though there was to justify it, confidence began to return to the

household, and Dolly had contrived to get some small share in the

nursing arrangements. Phineas spent much of his time with the

unusually obliging and sympathetic bobbin-maker, who, though he was

not able to say who Billy was, gave the cooper to understand that he

knew something and might be able to ascertain more. He had so

many plausible arguments to prove that Phineas was wrong in blaming

himself for the accident, and was so humble and obliging, that the

new landlord began to reproach himself for having so harshly

misjudged so sympathetic and right-thinking a young man; and as

Simpson's business had always been supposed to require incessant and

close attention, and must therefore be suffering from its master's

devotion to the cooper's affairs, Phineas could not but be sensible

of obligation, and relaxed and tried to forget the prejudice he had

so strongly conceived.

Simpson had pointed out that even if the patient recovered it

would still be better to find out all that was possible about his

friends—supposing that he had any; and so he spent his days making

inquiries, and his evenings in reporting progress to the cooper.

Two more days, and even the doctor admitted that if the patient's

strength held out, and he could be induced to take sufficient

nutriment, and if no relapse occurred, and above all if no drink

were given him, he might at anyrate last a little while longer.

This was a great deal to get from him, and the new inhabitants of

the King's Arms were relieved and encouraged; even Phineas allowing

himself now and again to think of worldly things—that is, of prize

poultry.

Simpson, it seemed, was touched with the "fancy," and knew

where a certain incomparable variety of Black Hamburghs were to be

had.

But the bobbin-maker was getting impatient: time was passing,

the value of the King's Arms was melting away day by day; his

venturesome hint that it was dangerous to defy the law and cease to

sell liquor whilst the legal objection raised by the opposition was

still undecided had been so frostily received that he had dropped it

hastily and changed the subject. The contemplated sale of the

coopering business had from Simpson's standpoint such a close

balance of advantage and disadvantage that he hesitated what to

advise, and so nothing was being done. Meanwhile, Clara

Crouch, triumphant over the little bit of astute work she had done

herself, and bitterly sarcastic about the slow pace at which he was

moving, was getting past living with.

The bobbin-maker was not either very imaginative or very

patient, and so, as Dolly had infected her parents with the fanciful

notion that their patient was a disguised aristocrat, Simpson was

badgered every time he went abroad to bring back all copies of

London papers he could get possession of; so that when he was

anxious to improve the time by inflaming Phineas's zeal for

fowl-fancying, he found that worthy profoundly interested in the

"agony columns," and eager to discuss every advertisement that might

by any stretch of imagination be supposed to refer to Billy Stiff.

The sick clerk's name was, Phineas argued, plainly artificial and

assumed---who had ever heard of "Stiff" as a surname before?—and

therefore any of the mysterious letters or names with cryptic

asterisks attached to them might refer to the man upstairs, and

provide a clue for his identification. Phineas had a new

theory, and a new and most probable clue, every time they met, and

Simpson, restive and impatient, wished Billy at the bottom of the

sea. The thought of how much the King's Arms was deteriorating

by every day's delay, prodded at his brain like a goad; whilst the

whimsical innkeeper became a mocking, tantalising demon who knew and

took fiendish delight in the torture he was inflicting. It was

really a relief, therefore, to turn his attention once more to

Dolly. The difficulties which had dismayed him before seemed

light and frivolous in comparison with those he encountered when

dealing with the impracticable cooper, and so he began to cast about

for an opportunity.

Three days passed: his impatience prodded his mind like

pricks at an already angry wound, but no Dolly came in his way, and

no means of reaching her presented themselves. His sister was

insisting that Dolly was a negligible quantity and could be secured

at any time when the way was once cleared; and she saw and pressed

upon him incessantly the fact that whilst the women-folk of the

King's Arms were occupied with their ridiculously interesting

patient, and Phineas was therefore left a good deal to himself, this

was the great opportunity of securing the cooper, and that was the

important consideration for the moment. But Simpson was

utterly sick of Phineas and his fads, and weary to death of fancy

hens and mysterious advertisements; Dolly at anyrate was

understandable and straightforward, and to her he would go.

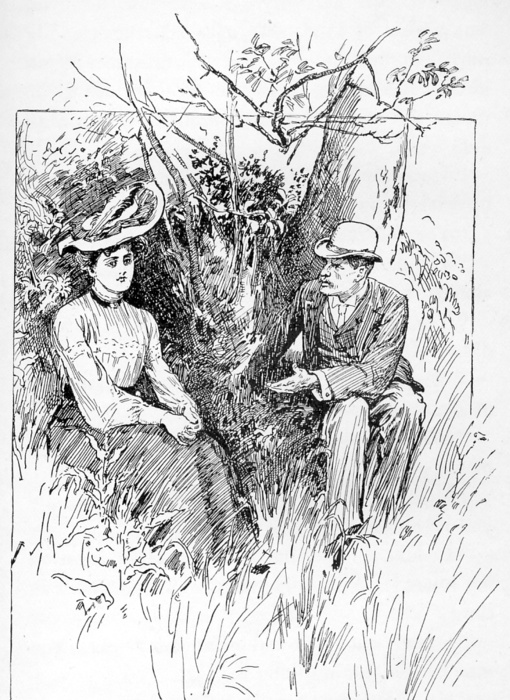

And fortune favoured him, for as he approached the inn one

evening he saw Dolly, dressed as for a walk, emerging from the front

door. He pulled up hastily and watched her; he knew all about

her close friendship with the bill-sticker and his wife, and easily

guessed by the direction she took that she was paying a visit to the

tollhouse. He followed her at a discreet distance; he could

not, as things were, accost her in the street, and so he waited

until she had passed the last house and there was nothing between

her and her destination but a long stretch of dusty road. Now

was his chance! He could never have a better opportunity; but

Simpson did not overtake her. The task so easy and hopeful as

he mused upon it in the office, seemed full of difficulty now it was

close at hand. The easy, pliable Dolly suddenly became

exceedingly formidable, and fifty strong reasons for at least

postponing the interview suddenly crowded into his mind.

Innocence, often the tempter, is always the terror of the guilty.

And so Dolly passed on to her destination, and Simpson,

deciding to wait her return, sank down into the full hedge-bottom.

There had been recent rain, and, though the roads were dry enough,

to Dolly everything smelt fresh and sweet; and her heart being full

of hope concerning their patient, she lifted her bright face to the

sunlight and caught, as she walked, some of Mother Nature's mood.

She was going for the walk more than anything else, for there was no

news to tell, as Jeff came several times a day to the King's Arms.

But somehow a common interest in the poor maimed fellow who lay in

the guest-chamber of the inn had drawn her of late closer and closer

to the simple couple who shared her sentiments, and it did her good

to hear Jeff talk with such radiant confidence of the poor

wanderer's reclamation.

Jeff's theology was very topsy-turvy and amusing, but somehow

there was always that in it which infected her with hope and

sweetness. Jeff had been at the inn with his bill-sticking

apparatus not much more than an hour ago, and having watched his

departure she was tolerably sure he was at home. She had

thought also that the old man was not looking quite as well as

usual, and attributed his condition to his anxiety and loneliness.

The door was wide open as usual, for as a matter of fact the cottage

was a somewhat dark place with the door closed; and a moment or two

later she had caught sight of her old friend sitting in his chair by

the chimney corner. The cloud on his face vanished at the

sight of her, and he sprang up, evidently full of some most

important matter, and advanced eagerly to meet her.

"Come in, come in wi' thee! Four chalk angils an' one i'

petticoats! wee'st win! wee'st win yet!"

"Angels! Win? Good gracious, Jeffrey, what's to

do?" and as he stood aside and majestically waved his long arm

towards the black mantelpiece, her eyes following his motions fell

upon four long white marks on the dark ground something like these:

////

"To do?" he cried, evidently bursting with his great secret.

"There's feightin' to do, an' wrastlin' and conquerin' to do.

Do you see them there?"

"Yes, but what are they? and what will 'Siná say to your

disfiguring—"

"Say! She'll say Hip, hip! She'll say Hurrah!

She'll slap me, she'll thump me on the back, she'll give me a

walloping kiss. Why, she's wanted me to do it for years!

And then, turning round and delightedly counting the strokes he

cried gleefully, "One, Two, Three, Four! Why, there'll be

twenty by the time she comes home—ay, an' more!"

"But what is it about? Why will she be so glad?"

"Why?" But Jeff had to fortify himself with another

ruminative glance at the strokes. "Hasn't she allus been down

on it? an' grumled an' carried on about it? Why, woman, she

read off about it every day as comes, an' you've heard her!"

"But what—what about?"

"Snuff! Nasty, dirty, stinkin' snuff!" And

snatching at her soft little hand, he drew her close to him and

thrust it where it had often been in other days, right down into the

depths of his vest pocket.

"Feel for it! Bring it out! Bring it out i'

handfuls!" he cried.

But Dolly could feel nothing. And when she drew them

out her fingers were not even browned. She glanced at her

hands, glanced at his big wistful face, and then her countenance

softened, and there was both suspicion and regret in her eyes.

"Jeffrey," she cried, looking him squarely between the eyes

and compelling honesty, "you are not giving up your only little

luxury for—for want of money?"

"Money? No! F or victory, for castin' out devils an'

gettin' hangils," and, turning towards the chalk-marks, he counted

them out again with tender pride. "One, Two, Three, Four, an'

tomorrow there'll be five or six." And he stood aside that she

might look at the magic strokes, with a face beaming with the pride

of a mighty victory.

"But, Jeff, I really do not see; I don't under—er—what do

you mean?"

Jeff's face took on a grave, pedagogue-like severity; he

turned his back on the mantelpiece, raised his arms, and beating out

his words one by one with a finger on the opposite palm, he

demanded—

"Now, to look you here, are we all possessed o' devils or are

we not?"

Dolly might have demurred to this sweeping generality, only

she knew her man, and so she only nodded.

"An' my devil's snuff, isn't it?"

Another nod.

"Well, four days sin' I casted him out!' And then, as

his announcement did not produce the dramatic effect he had

evidently anticipated, he added the severe expostulatory demand,

"How can I cast his devil out if I haven't thrown me own?"

"His? Whose?" And Dolly looked more bewildered

than ever.

"Whose? Why, Billy's! He's gotten a leguned o'

devils in his poor inside, an' how can he cast 'em out by hissel?"

"No, but God can."

"Ay, an' we can! Why, woman, where's you' theology?

Our preacher o' Sunday said, nobody can cast out other folkses

devils till they've cast their own out."

"Yes."

"Well, when I've cast my own out I can help him wi' his,

can't I?"

"Well, how?"

"How! Hay, woman, you should come to Frog Lane Chapil,

they know nowt about theology at t' Parish Church. Did you

never read about that poor chap, that cripple that was lowered down

into t' midst o' Jesus?"

"Well?"

"Well, didn't He say, Your faith hath made him whole?"

Dolly could not trust her memory for the details, but she

shook her head in dubious misgiving.

Jeff, quite impatient at her obstinacy, glared at her

indignantly and cried—

"If them chaps could help their mate, I can help mine, can't

I?"

"Y–e–s, but no—"

"Not!" and Jeff was growing quite angry at her density.

He glowered at her in puzzled helplessness for a moment or two,

turned and took a reassuring glance at the chalk-marks, and then

demanded—

"There's four marks there, isn't there?"

"Yes."

"And four marks for me is four for Billy, isn't it?"

Dolly couldn't quite follow.

"If I conquer four devils, won't poor Billy get four angels

instead? Ho, ha! Oh, bless us, woman—!"

But the poor bill-sticker was being almost smothered; for, as

the meaning of his topsy-turvy doctrine at last broke upon Dolly,

she had blushed with the pleasure of an exquisite surprise, and with

burning cheeks and shining eyes had flung her soft arms round the

big man's neck and was smothering him with kisses. There was

one for himself and one for that dear old snuffy nose, one for each

of the chalk-marks and one for each of the angels.

"Why, Jeff, you're the theologian for me! You ought to

be an archbishop, and, bless your dear old face, you will be when we

get to heaven. Oh, Jeff, dear dear Jeff, what a saint you

are!"

Jeff laughed, and rubbed his big hands in soft, silent

contentment; and then, falling into personal talk, they chatted

gaily together until Dolly was compelled to hasten away, and was

seen going down the long road again with dewy eyes and a heart

strangely soft and tender; all unconscious of the waiting Simpson.

The bobbin-maker had been raising his courage by running down his

manhood, stimulating himself to bravery by calling himself a coward;

but the moment he caught sight of her returning, his new fear of her

came back, and if he had followed his first impulse he would have

fled incontinently. What had come to him to cause this curious

change he could not tell; but she was now drawing near far too

swiftly, and was upon him before he could settle his own course of

action. Yes, she had seen him, and had already left the middle

of the road and was inclining to the grassy side where he sat.

A stupid helplessness came over him, and, left to himself, he would

have allowed her to pass, but she was approaching, standing before

him, actually speaking.

"Ah, Simpson, I'm glad—I wanted to speak to you. Is

there room?" and—it took his very breath away—she actually dropped

on the bank by his side. Why, the girl was pretty! He

had never taken much notice of her looks, and now she seemed to be

going to drop into his very hands! What a fool he had been to—

"Simpson, you were not yourself when I came to your office."

"Dolly, I'm a fool—a mad, staring fool!"

She was looking at him very quietly. Why, she hadn't

the spirit of a fly.

"Never mind, Simmy; father doesn't know, and—and never will

do!"

Her tones were actually coaxing; perhaps if he held out a

bit—

"I don't think I behaved very well to you then"—(yes, she was

positively asking to be reconciled)—"but I am very sorry; I was

foolish and wicked; and—and will you forgive me, Simpson?"

There was a long silence, and Simpson was thinking rapidly

for him.

"You see, Dolly, girls like you don't understand business,

and the many things men have to worry about."

"No, of course—then you do—you will be friends, Simpson?"

Simpson, dull as he was, had a misgiving, and looked at her

narrowly. All he saw, however, was a pair of kind, soft eyes

looking steadily into his, and he had not the glimmer of an idea of

the noble thing she was trying to do under the stimulus of her

recent interview with Jeff.

"I was trying to please you, and—and hurry up with the

wedding, and—"

"Yes, but it is all for the best, isn't it?"

"The best?" and a heavy struggling surprise clouded his

anxious face.

"Yes, God is good; He just stepped in in time, didn't He?"

With dropped jaw Simpson stared stupidly at her, and

repeated, "In time?"

"Yes, we might have married—oh, isn't it a mercy!"

"Mercy? What on earth—oh, hang it, are you laughing at

me?"

"I could laugh, Simpson, I could go down on my knees!

What a blessing we found it out in time!"

"Found out? Found what out? Are you mad?

Are you mocking me?"

"Are you mad? Are you mocking me?"

"No, Simpson, no, but our eyes are opened; you never loved me

and I never loved you."

Now amazement, cupidity, and anger were all swallowed up in

one great sudden fear.

"Oh, don't, Dolly! Have pity! We do, we do love

one another!"

"No, no, Simpson; you know and I know we never did and never

can, and a gracious Providence has intervened to save us from

ourselves."

But the bobbin-maker was thoroughly roused at last; every

sordid vision and every greedy motive of his life came clamouring

back, and for ten minutes he poured out his pleas to her. He

reasoned, he protested, he besought her, and stormed at her; but

Dolly, sitting quietly by his side on the bank and patiently waiting

for him to finish, showed in every feature and movement and word the

same pensive but immovable decision.

Then he lost himself: sneered at her, mocked, threatened, and

defied her; but save for the fading of the smile on her lips and a

slight elevation of her dimpled chin, she kept the same quiet front

and the same easy manner. Soft and low were her answers, and

her words were sympathetic, but firm and unalterable. They

were not suited to each other, and ought never to have come

together. They had both of them foolishly trifled with God's

holiest gift of love, and done grievous wrong. But the

Almighty had been merciful and stopped them in time, and in deepest

gratitude to God she forgave Simpson and asked him to forgive her.

She hoped they might be friends; she was sorry if she was grieving

him, but she was sure she was doing the right thing, and they would

both be thankful for it some day.

Simpson tried again, pleading, coaxing, confessing, storming,

cursing; but at last she turned away from him with a sigh, and as

the baffled and amazed lover stood there in the deep wayside grass

and watched her go down the white road, there came, by processes too

deep to describe and transformations too subtle for any thing but

our inconsistent human nature—there came into that selfish, sordid,

narrow breast the real, deep, fatal love which, had it come earlier,

might have redeemed and glorified his life, but which was now to

haunt and dwell in him as the baleful instrument of his destruction.

Yes, Simpson Crouch was in love: it seems an appalling

degradation of that holy thing to apply it to such a person, but

there was the fact. Such a passion in such a soul was much

nearer to hate, perhaps; but by whatsoever name it might be called,

it was a deep, overmastering, ungovernable lust of possession, so

imperious, domineering, and unscrupulous, that like a sinister rod

of Moses it swallowed up every other magician's wand of life, and

turned every other motive of existence into fuel for the feeding of

its own devouring into flame.

That mean greed, so often the driving power of narrow

natures, and which had hitherto governed Simpson's life, now became

the mere servitor of the overbearing monster which had set up its

kingdom within him; for possession of Dolly Wenyon he henceforth

lived, and to that end even money, which he had loved most, would

now be subordinated. Standing there, and watching her as she

tripped lightly down the road, he did not altogether realise the

nature of the change which was taking place within him—he was not

given much to self-analysis; the new passion welled up quietly

within him, a deep, strong, unreasoning, but utterly irresistible

passion, a passion that grew hotter and hotter as he realised more

and more that he had lost her. Hitherto he had held her

lightly, and chiefly perhaps as a means to an end; but now that he

knew she could never be his, the dull bull-dog tenacity of his

nature awoke, as belatedly as it generally does in such characters,

and all things else in life became mere means of securing her.

Never had the scheme his sister had suggested, and he was trying to

work, seemed so utterly, so ridiculously hopeless as it did at that

moment, and at the same time the motives which had hitherto urged

him on seemed as nothing to the ruthless, overmastering desire that

now possessed him.

Long after the last flutter of her light dress had

disappeared round High Street corner he stood staring down the road,

until his eyes burned and he turned his glance to the dust at his

feet. Then he began absently to toy with the powdered

road-metal, scraping it into little heaps and then rubbing his boots

into it, until, forgetting the mystic spell which the King's Arms

had cast upon his imagination, forgetting the comfortable competency

which of late had bulked out so large in his mind, he could see

nothing but the face and figure of a dainty little woman with blue

eyes, brown hair, and a complexion only made the more piquant by a

saucy little freckle here and there. The more firmly these

feelings were forced back the faster they came. His was not

the love that softens and purifies, that refines and elevates; it

was the besetment that bemuses, that enthralls, that blinds the eye

and blunts the conscience and confuses the judgment. Every

higher impulse within him was for the moment smothered under the

overwhelming presence of a tyrannical pre-possession that was now

absolutely his master.

CHAPTER XVI

PHINEAS IN HIS GLORY

WHEN Simpson

reached his home that night Clara had news for him. She had

been in charge of the office all that day, and reported that a

strange man had called thrice, evidently very anxious to see the

proprietor. On his last visit Clara had drawn him into

conversation and had gradually and very deftly ascertained his

business. He was the confidential agent of the Packington

brewery; and having ascertained that Simpson stood in a certain

interesting relationship to the Wenyons, he had called to see if he

could not use his influence with Phineas to induce that worthy to

sell the inn; and he had intimated not too obscurely that to anyone

who could do this the brewery firm was prepared to pay—say £500.

He had also hinted that it would be well worth Simpson's while to

persuade the ex-cooper to continue the sale of liquor pending the

decision of the lawsuit threatened pending by old Joshua's

middle-aged heiress.

Simpson listened with sullen eagerness, and when the mocking

helplessness of their situation unfolded itself before him he sprang

to his feet uttering a curse and heartily wished the cooper as dead

as a herring.

Clara, concealing her surprise at this new spirit in him,

turned a leering face upon him and asked—

"Dead? Dost know what there is in old Joshua's will?"

With an ugly scowl and an overbearing manner quite unusual in

him, Simpson demanded gruffly—

"What's thou know about t' will?"

"I know"—and Clara leered again.

For a long intense moment they looked each other in the face;

but to her own surprise and alarm, Clara was the first to flinch,

and a feeling of uneasy fear of her fool of a brother arose for the

first time within her.

"That will provides that the King's Arms shall be his as long

as he lives in it, and that if he is living in it when he dies it is

to go without any conditions or restraints to his daughter."

Simpson had stopped in his fretful pacing across the

hearth-rug, and was frowning down upon her; their eyes met with a

long, stealthy look. Those two were not exactly the stuff of

which great criminals are made, and no definite idea was for the

moment in either of their minds; but as one of them was now filled

with a passion that was fast becoming ungovernable, and the other

held the notion that Dolly did not count in the affair, they were

both looking slyly in at the entrance-gate of that sinuous,

treacherous road whose beginning is a vague wish, whose windings

pass through suggestion to possibility, from possibility to longing,

and from longing to necessity, and whose end is a deed in the dark.

That night the two sat long together, and came closer to each

other than they had been for some time; Simpson, with a new

boldness, taking a savage delight in enumerating their difficulties,

and his sister half perplexed and half encouraged by the change in

him. Though less under control, he was more pliable; and

though she missed something of his old fear of her, she was

conscious of closer sympathy. The sleepless night that

followed would have been even more restless than it was had he told

her all he knew.

Next morning Simpson had a long interview with the brewer's

agent, but when he went down to the the King's Arms in the evening

he found Phineas even less amenable than usual. The fact was,

the patient upstairs had had a turn for the better—even the doctor

had admitted he was "a tough 'un"; and when this was reported to the

new landlord, that mercurial old hobbyist had gone from one extreme

to the other, and plunged eagerly into the many new interests which

his change of residence had provided. So far the business of

the hostel had not declined in the least; for though nothing

stronger than coffee was purveyed, the inhabitants of the town,

easily excited to curiosity, had visited the place in such numbers

as to keep all the available servants fully employed; and now that

Phineas had come out of his doldrums and was available, every caller

wanted to see and speak with the man who had all at once become so

notorious.

The fact was, the thing had got into the papers, which

contained long descriptions of the King's Arms and the absurd old

man who bad been "bested" in his spiteful will-making by the

high-spirited and astute Snelsby cooper. This brought

strangers into the town, and caused those visiting Snelsby for other

purposes to make calls at the now famous inn; and Phineas, realising

the situation, sat in the bar-parlour smoking uncountable pipes of

tobacco, receiving endless flattering compliments, and beaming all

over with innocent self-consciousness as one and another joked him

about his amazing cleverness or read out to interested listeners

tit-bits of the newspaper reports.

This was all very trying to Simpson, for the new landlord,

who in his recent conscience-smitten depression had shrunk from

contact with his fellows, now courted publicity, and was only too

glad to receive congratulations or listen to stories about the

sensation be was making, and reports of conversations of which he

had been the subject. Three days passed away, and Phineas,

still left much to himself, in consequence of the absorption of his

women-folk in the delightful anxieties of nursing, was being

constantly flattered and courted by his customers, and becoming more

and more self-confident and less and less amenable to the promptings

of the Crouches. The business too was flourishing; in a

slow-going place like Snelsby people did not easily change their

habits or get out of ruts, and still many of the old callers from a

distance still "put up" at the place. The curiosity-seekers

also showed no sign of diminishing in numbers, and money rolled into

the King's Arms coffers in such amounts that Phineas, unaccustomed

to the handling of such sums, began to feel rich, to see visions of

untold wealth, and to build wonderful castles in the air in which

roomfuls of silver cups and prize cards for champion poultry figured

largely.

The ex-cooper had never had a banking account, and in fact

trade was conducted on such conservative lines in Snelsby that very

few of the trades people had as yet adopted the modern practice.

The little branch concern opened only three days of the week, and

that for a couple of hours each day, being used chiefly by the local

gentry. But the bank agent called on Phineas, and affected

both surprise and distress when the new landlord seemed uncertain

about the continuance of the King's Arms account. The bank had

held the account for many years, he assured the landlord; and

discovering that part of Phineas's reluctance arose from ignorance

of procedure, he contrived to hint at the things necessary without

allowing his customer to think he was being instructed. The

cooper had the air of one conversant with all such matters, but

willing to allow explanations; and, swelling with a new and

flattering sense of importance, he condescended to open an account,

and began to carry about with him a cheque-book, the outer corner of

which peeped out accidentally over the edge of the landlord's

breast-pocket. But the proudest moment of Phineas's life was

that on which he was photographed for a London paper. He was

seated one morning in the bar-parlour, a pot of herb beer before him

and a long churchwarden in his mouth, and was retailing for the

twentieth time the story of how he had "bamboozled" his wife and

daughter in the matter of his grand coup, when Cuffy the new ostler

flung the door open and cried—

"Wanted, sir! Gent from Lunnon wants to take your

picter."

Phineas broke into a gentle smile, but suddenly recollecting

himself, artfully pretended not to have heard, in order that the

announcement might be more loudly repeated. Every eye in the

room was turned upon him with admiring wonder, and he lolled back in

his chair with his brain floating in bliss complete, and put on an

excellent pretence of weary protest against the embarrassing

popularity of which he was the unwilling victim.

The stranger from London was waiting outside, but Phineas was

anxious that the interview should be as public as possible, and so

he announced that he could not and would not stand this sort of

thing, and that he was not going to budge from where he was, even if

the Queen herself and all London were to come to ask him. Amid

murmurs of admiration Cuffy was negligently ordered to introduce the

stranger; and when that was done and the new-comer had tasted and

highly commended the teetotal beer, the business was introduced.

The new landlord's portrait and that of his public house were

required for that important public journal of world-wide repute,

The Teetotaler's Record.

With the air of a man who could stand a great deal but really

must draw the line somewhere, Phineas shook his head and offered

sundry objections, all of which were immediately and triumphantly

overruled either by the stranger or the assembled company; and at

length the indulgent hero of the hour allowed himself to be

persuaded, and operations commenced. Phineas, though he wore a

face of ponderous gravity, was in the seventh heaven of secret

delight; and as he stood there in the inn doorway with a mysterious

machine and a more mysterious man pointing at him a few yards away,

male and female servants flattening their noses against the windows

or squinting round corners, whilst little admiring crowds of

spectators were looking on from the pavement, the ex-cooper was

supremely happy man.

At the crucial moment, however, when Phineas Was pulling and

screwing his face about in vain attempts to get the requisite

"natural" expression, Dolly came out with a hurried message from her

mother that he must on no account be photographed in his workaday

clothes, but must go indoors instantly and put on his Sunday

"blacks" and his "gold guard." In magnificent scorn of women,

the landlord utterly refused to make the slightest change; and it

was only when Dolly was reinforced by the photographer and the

assembled company that he so far yielded as to put on the gold guard

with its big hanging seals. The business was then proceeded

with, and the buildings, the signboard, and the landlord himself

were all duly "taken"; and when the artist, as he packed away his

camera, asked who was the author of the "poem" on the board, Phineas

received the compliments due to the author in the manner of one to

whom the production of such works of genius was the veriest trifle.

Simpson Crouch therefore found, when he came carefully primed

by his sister, that he had somehow lost ground, and was fain, though

with much inward uneasiness and disgust, to spend his evening amid a

crowd of lemonade, coffee, and "herbal champagne" drinkers, and

pretend to be interested in the marvels of photography and the

widespread power of the London press. The bobbin-maker was

getting worse than desperate; the inn was of course declining in

value every day, and so far he had accomplished little or nothing

with the fantastic and obstinate cooper. He had hoped that at

least the lawyer's message announcing the legal objections of old

Joshua's heiress, and advising that, at anyrate until the questions

thus raised were decided, it would be safest to let all things,

especially the sale of drink, continue, would have made some

impression, considering that be had done his utmost in support of

it, and even hinted at the danger of imprisonment for contempt of

court. But Phineas was not only obstinate, he was pugnacious,

and had gone so far as to threaten that he would remove his case out

of the hands of the "muddlin' owd slow-coach" who had made the

suggestion. One small success Simpson however had made: he had

induced the ex-cooper to postpone his loudly announced intention of

having the beer, porter, spirits, and wine found on the King's Arms

premises poured down the gutter in the presence of wondering

Snelsby.

Presently, however, Simpson took to his sister's plan of

encouraging rather than opposing the innkeeper's fads, and,

returning to Phineas's notion of changing lawyers, waxed eloquent on

the abilities and persistence of a somewhat notorious man of briefs

in Packington. The man was known to the ex-cooper by name at

least, and so he was rather taken with the idea; but on the night of

the photographing, when the bobbin-maker had expected to get his man

persuaded on this point, Phineas would talk of nothing serious, and

for some reason or other could not be induced even by the plainest

hints to forego the society of his friends.

Baffled with the father, he slunk out of the room and began

to haunt the passages in the hope of seeing the daughter.

Hitherto, he told himself, he had held her too cheaply, but now, to

his embarrassment, every flutter of skirts he heard sent a thrill

through him; and when at last he caught sight of her, she was making

her way directly towards him. His heart came into his mouth;

his very hair began to rise. He responded to her kindly

greeting in muffled, confused tones. She did not seem in the

least disturbed; she stood there and chatted to him evidently

unconscious of what he was suffering, and conducted herself as

though there had never been anything between them. Presently

she began to talk about their patient Billy Stiff, and Simpson, with

pangs of jealousy fiercely stinging him, was fain to seem at least a

little interested. But as she talked she opened the front

parlour door and smilingly beckoned him inside. Now was his

chance! But she was still dwelling on the drunken clerk

upstairs, and asked question after question until he had told her

all he knew. Then to his chagrin she made as though she would

leave him. The tantalised lover sprang between her and the

door and broke out into impassioned piteous appeals and all a

lover's desperate threats. She listened; she made no attempt

to withdraw herself, and at last, telling him once more that he

ought to be thankful that the divine Providence had intervened to

prevent a fatal mistake, she rang the bell, asked the maid who

responded to bring Simpson a cup of coffee, and then quietly

retired.

That night Simpson told his sister about his final dismissal

by Dolly. She did not fail to notice that this had occurred

three days ago; but when he came to describe the interview he had

just had with his late sweetheart, she followed his recital with

quickened interest and anticipated his conclusion with one of her

mocking, mysterious laughs.

"What is the crazy fool grinning at?" and his tone was

thunderous.

Another and more tantalising titter.

"D'ye hear! What is there to laugh at— besom?"

"Nay, nothing," and she turned her head away to hide another

sneering grin.

With a curse and a bound he was at her side, and, raising a

clenched fist, stood threateningly over her.

This was a new style, but Clara, though startled for the

moment, was not by any means dismayed.

Slowly she brought her dark eyes round to his and looked

steadily at him. She was disappointed and alarmed: the days of

her ascendancy were over, the eyes that glared down into hers were

those of a goaded creature; there was cruelty, brutality, even worse

in them.

But Clara was not of the stuff that admits easily of defeat,

and so with a supreme effort she withdrew her eyes, drew herself up

to her utmost height, pointed haughtily to a chair, and coolly

informed him that if he would sit down she had something to say.

Simpson dropped the threatening arm, glared at her for a

moment, and then with another scowling glance slunk back into his

seat, growling as he did so, "Out with it."

"She talked about Billy, did she?"

"Ay, and Billy to it; what of that?"

"And worked the pump-handle till thou were dry?"

"Ay, what by it?"

Clara rippled off another tantalising laugh, and then,

frightened though she was—she could not have helped it for the

world—she cried—

"Why, Simmy, Beau Simmy, thy pipe's put out!"

"What?"

"She's in love, she's thrown over the master to take the man.

Man?—thou'rt beaten by a guzzlin' tramp."

Simpson, gnawing at his lips and driving the nails into his

clenched hands, cried fiercely—

"Confound you, woman, talk sense!"

"Sense? Why, it's as simple as simple. She's a

brainless, spooney little flirt, and this is her romance, her

three-volume novel. He's saved her life, she's helping to

nurse her hero, and is in love with him."

Next day Clara visited the King's Arms, and seemed not the

least put out that she could not see the landlord, who was said to

be too busy. She lingered longer than usual, however, and

seemed to have some particular interest in the domestics. And

later that day Cuffy told Phebe and Phebe told Miriam and Miriam

told Mrs Wenyon that the man they were all so devotedly nursing was

a "ticket-o'-leave man" [ex-convict on probation].

But the slander, if such it was, overreached itself.

Mrs Wenyon became more enthusiastic in the invalid's favour than

ever, Phineas put it aside with easy indifference, and Dolly was

first of all highly indignant and then most strangely confused.

The report was producing an effect upon her she could not quite

understand, and a strange but deep shyness, as though the dishonour

were in some odd way her own, came over her. Next day, with

the self-consciousness of a criminal, she was down at the tollhouse

again, craftily sounding the temporarily wifeless bill-sticker about

the report that had disturbed her so much. She found Jeff

seated before the mantelpiece proudly surveying the chalk-strokes

with delight and serene satisfaction in his face.

"Them's 'em," he cried with a triumphant wave of his

arm—"nine on 'em! Nine champion wins for me! Nine

knocks-down for Billy's blue-devils and then breaking off, bending

towards her and patting her arm, he cried victoriously, I care no

more for snuff, see you—I care no more for snuff"—and Jeff had

difficulty in finding an adequate figure of speech—"nor my old woman

cares for theology."

As this was evidently Jeff's highest possible conception of

supreme indifference, Dolly had to smile.

"But, Jeffrey, they're saying most dreadful things about

him."

"Like enough," and Jeff seemed to take a sort of pride in the

fact.

"But they say he's a culprit, a—a—ticket-of-leave man."

"Like enough, woman." And Jeff seemed actually

disappointed that it was not something more dreadful.

"But it is shocking! It is dreadful! I don't

believe a word of it, so there!"

Jeff took a reassuring glance at the chalk-marks and smiled

with generous toleration. After all, it was perhaps too much

to expect a young female to understand so abstruse a point of

theology.

"But, Jeffrey, you seem to be glad he's a felon—which he

isn't."

"'The more guilt the more glory,'" quoted Jeff with a

sententious wag of the head. Dolly stared at him with a frown

of perplexed inquiry, and at last, condescending to her youthful

limitations, he pointed to a little jug hanging on the pot shelf and

demanded—

"That there jug has got one little piece out of it, hasn't

it?"

"Yes; well?"

"And anybody—you or me—could mend it wi' a bit o' shallac and

a pinch of commonsense."

"Well?"

"But what if it wur broke into a million'd pieces and most o'

them wur lost?"

"Well, nobody could—"

"The chap that mended that 'ud be a top-sawyer, wouldn't he?

A regler stunner, wouldn't he?"

"Yes, but—"

"Well, there you are, aren't you?"

"I don't, I can't—"

"Why, bless the woman, it's as plain as the wart on Tommy's

nose," and then, rising and standing back with a face that was one

prodigious frown of concentrated wisdom, he cried—

"Now suppose the Lord was to save a parcel o' folk like me

an' you—that's nothin'; anybody could do that! But if the Lord

takes hold of a regler out-an'-outer like Billy an' makes a job of

him, that's summat like, isn't it?"

But Dolly had no particular interest in the point he was so

laboriously making her anxieties ran in another direction, and so

she said with a little expostulatory smile—

"But, Jeffrey, you always said he was so gentle and humble

and kind."

"And who says he isn't? Who says a word again' him?"

And then, as the momentary indignation faded in the presence of

another thought, he shook his head solemnly and sighed. "Hay!

we shall have a terrible time when he gets about again."

"Yes, but he's had no drink since the accident, and—"

"No, nor for two days afore. Hay, didn't we wrastle,

him an' me!"

"God bless you, Jeff; we must all help him."

"Help him? Yes, you'll help him, an' Tommy 'ull help

him, an' I'll help him. But, Dolly—"

"Yes, Jeffrey?"

"We shall have to have a lot of patience."

"Yes."

"And if at first you don't succeed—"

"Yes?"

"And we mun forgive seventeen times seven."

"We will, Jeffrey and if only—"

"An' you mun love him hard an' patient with all your might."

Dolly dropped her eyes with a sudden shameful blush.

"An' I'll keep on wi' me chalks, and God an' us all 'ull pull

him through."

And Dolly dropped a soft kiss on the earnest rugged face, and

cried—

"Yes, Jeffrey, yes, we will."

When she got home that night, Dolly found that 'Siná had

contrived her an opportunity of a momentary glimpse of the patient;

but the sight so shocked her that it haunted her day and night; and

though now she had occasional chances of seeing him, she felt that

he watched her so hungrily as she went about doing 'Siná, or her

mother's bidding in the bedroom, that it was always a relief to get

away. The contrast between this ghastly, hopeless-looking, and

still noble invalid and the merry-andrew drunkard who first visited

her in the old summer-house was of the most startling kind; and so

when she was there she was anxious to get away, and when she was

away she was anxious to return.

But now she remembered that her mother had shown that very

day a very marked tendency towards returning to her natural

pessimism, after more than a week of defiant hopefulness. She

hinted of the matter to Thomasina, and the sour snarl with which the

bill-sticker's wife responded was a stronger confirmation than any

words could have been of her fear that the patient was not doing

well. Seeing her distress, however, 'Siná became conciliatory,

and presently in a gush of penitence confided that the patient

himself did not want to recover, and had begged them again and again

to let him die. Unconscious of the degree in which she was

allowing herself to be absorbed in the condition of the sufferer,

Dolly now took to assisting in the preparation of his food and to

haunting the passage outside his bedroom, and by the end of another

week she had established a precarious and tentative footing in the

sick-room. During these days her favourite occupation was the

construction of simple little speeches of thanks for her timely

rescue; the very first thing she must do when he became conscious

was to make it clear how much his heroism was appreciated; but when

she stood by Thomasina's side and the opportunity presented itself,

the laggard words would not come, and she felt dull and dumb.

Then the patient's manner began to disturb her. He would not

look at her. Whenever she glanced at him she found he was

watching her, but the moment he found he was observed he turned his

head away and closed his eyes. His gratitude was most

touching; he would now and again turn his head towards her mother or

Thomasina, and snatching at their hands imprint a wistful kiss upon

them. But to her he never even spoke, and seemed to close up

and shrink into himself the moment she appeared. One day the

sight of him wincing as Thomasina moved him touched her, and before

she knew what she was doing she had blurted out, "Poor fellow!

God bless you! You saved my life."

Still as death he lay: she might just as well have spoken to

a clod.

Presently, however, still keeping his eyes closed, but with a

tear of touching gratitude, he said, intones that spoke the

gentleman and sank deep into her soul, "God save you from pitying

me!" and then, as she commenced a distressful protest, he added, his

face going ashen grey and sudden perspiration standing on his brow,

"It is death! It is death!"

It was the longest speech he had made except when delirious,

and 'Siná, seeing that it had shaken his very soul, hurried Dolly

away; and as the patient was restless and exhausted all that night,

Mrs Wenyon peremptorily forbade her to go near him again.

Meanwhile the patient was slowly but very uncertainly coming

back to life, and such a coming back it was as sufferer scarce ever

had before. For months before the accident he had lived a life

of drivelling, loquacious imbecility; when he was most drunk he

appeared sober, and when he was soberest he was most drunk. A

babbling, helpless wreck of a man, body and brain and soul steeped

in chronic intoxication, he had lived a surface life of bubbling,

effervescent jauntiness, gay, reckless, incessantly talkative, and

yet curiously harmless; whilst the real man in him had lain as dead

and dumb as though it had never been. But when he came to

himself in the King's Arms bedroom after many days of half-conscious

suffering, the Billy Stiff known to Snelsby had become a mocking,

jeering shadow, whilst the real man, the free, handsome, brilliant,

dangerously successful man he had once been, had come back with all

those marks of degradation and ruin upon him which his late history

had produced. Never, surely, was there a more terrible

awakening; and never did poor soul, appalled by a countless array of

mocking self-injuries, ever more desperately desire to die.

Too weak and helpless to endure the constant contemplation of

his own irretrievable life-wreck, he found escape and momentary

relief in a form of introspection only possible perhaps to an

educated man. What precisely had happened to him? That

enforced abstinence from drink did bring the torturing misery he was

enduring he knew but too well, and knew also the taunting,

maddening, but cowardly refuge from it. But there was some

change, and change not wholly explainable either by his great

weakness or his injuries. There were new elements in his

consciousness, new vague shapes that evaded arrest and frustrated

all his attempts at identification—shapes that scarcely were shapes,

but dissolved and formed and dissolved again before he could

recognise them. Anything that gave him temporary relief from

the realities of his position was welcome, and he dwelt position on

these things curiously and constantly. What were they?

Whence came they? There was a new tenderness within him, soft,

warm, and comforting. And not the weak, chronically lachrymose

softness which had been one of the characteristics of his

degradation, but something purer and truer.

He thought of the old tollhouse and its simple, gullible, and

fantastically minded occupants, with their ridiculously Utopian

scheme for his reformation; but the cold light of reason with which

for the moment he looked on those two old simpletons was suddenly

drowned in a burst of tender, glowing affection, and in the unique

experience of a new emotion he dwelt with clinging eagerness on the

very delusions he despised; whilst every absurdity, every narrow

ignorant limitation of the old couple, seemed to cover them with a

new beauty and make them nearer and dearer to him. Yes,

nearer—that was the amazing thing. Until now they had been

outside his life; but now—oh, the pain, the delight of it!

They had come into him, were part of him, sharers of his life,

fighters of his battles, feelers of his pain; and as he lay-there

musing thus in the still watches of the night, there welled up

within him emotions strangely blended of almost every extreme the

human consciousness ever experiences; and with expanding, melting

heart and soft, silent tears he murmured, as the rugged faces of old

Jeff and his wife seemed to float before him—

"Oh, God!—If God there be—Thou hast chosen the weak things of

the world to confound the mighty."

On other occasions, under the actual necessity of almost any

escape from cold, cruel reality, he explored his mind in other

directions, with results always surprising and sometimes strangely

sweet. The ridiculously exaggerated gratitude of the Wenyons

for what he himself regarded as a purely impulsive act distressed

him; but the deed itself had some strange charm about it which was

infinitely comforting, and be turned it about in his mind like a

delicious sweetmeat in the mouth. But the thought clung to

him, fascinated him, enticed him, and that not for itself, but for

some dreamy but consoling associations. The memory of that one

heroic moment in his later life seemed, like the painting of a

mediæval master, to be rimmed in faces—dream faces; not such as he

had seen in the drawing-rooms of his former life, but simple,

homely, kindly. Ever and again there came a sweet, frank,

fresh face, pure as the lily and as fresh as the wild rose.

Absorbed, entranced, he lay in rigid stillness contemplating these

bewitching visions of his fancy; and then waking with a great start,

the horror of a great fear on his face, and perspiration bursting

out of every pore, he would groan—

"God! Jeff's God! Thomasina's God! Her

God—save her from a man who drinks!"

But these were fleeting, momentary experiences; for the most

part the eyes of his soul were fixed as by some hypnotic power on

the endless march of bygone scenes as they tramped through his

brain. The one thing that dulled the scorching vision being

now beyond his reach, he was left to stare on the bare realities

with no power to do anything but stare.

A dogged spirit of endurance, and a grim sense of the justice

of his treatment, helped to resign him to his tortures, but he was

tantalised and perplexed by a consciousness of something strange in

it all. The dreary winter landscape of his mind now had light

on it, flitting, changing, evasive light. Was as hope the arch

mocker not dead yet? Did he think it possible to delude him

even yet? He laughed, deep in his soul he laughed; but the

light still lingered, and even grew. It was light: every

mistake, every mad folly, every reckless sin of his life stood out

vividly in it, and new aspects of weakness, and new depths of folly,

became visible every moment. But he clung to them, dwelt upon

them, had a sort of morbid liking for their very tortures. He

thought of his many struggles, of his falls and re-falls, his fresh

starts and deeper declines; but though each poignant detail stood

out now more strikingly than ever, he did not want to shun them, and

dwelt and dwelt upon them like one spell-bound. Then he would

awake, awake with a shudder and a gasp that was almost a scream, and

with sudden horrified recoil, as though sonic awful abyss suddenly

yawned beneath him, he cried—

"Oh, God, give me death, but do not mock me with hope!"

CHAPTER XVII

A TERRIBLE CATASTROPHE

IF ever there was

a tantalising, aggravating old humbug in this world, surely it was

Phineas Wenyon. Simpson's projects were not progressing, not

advancing a single point; and this perfectly maddening old man would

sit there in the bar-parlour, spreading himself and swelling with

vanity, basking in the relaxing rays of popularity, and cultivating

a pharisaic meekness, whilst extracts from newspaper reports, all of

a highly flattering character, and spicy tit-bits of conversation,

were purveyed to him by admiring customers. The "old stupid"

could not see, as he, Simpson, could, that he was being spunged upon

and laughed at; inflated with vanity, growing fatter, redder, and

more important-looking every day, he gave no heed to anything but

his recent brilliant achievement and the excitement and confusion it

had caused in "the trade." To Simpson it was sheer

insanity, reckless, ruinous insanity. Every day that passed

took at least fifty pounds off the value of the hostel, and there

was that acrid old lady, old Joshua's heiress, whose threatened writ

might be served any day. There were twenty little schemes for

circumventing her, and that without excessive expenditure, if only

the old blockhead could be got to attend to them.

But day in and day out he would sit in the bar, distending

himself with self-importance and discussing teetotalism, model

public-houses, and fancy poultry, whilst the value of the property

was melting away to nothing! Simpson had talked teetotalism

and hens until his very heart was sick; he had spent hours in

exploring the numerous outbuildings of the King's Arms, and

discussing the most approved methods of adapting them to poultry

pens; he had drawn sheets and sheets of suggested plans, and had

even been mad enough in one supremely weak moment to put himself

down as a subscriber to a new Poultry Encyclopaedia to please

Phineas—only realising when too late that he had made himself liable

for 2s. per month for about three years, and that on a thing his

soul hated.

Never a day passed but he made one or more attempts to reason

with the new landlord on the situation of affairs; but however

patiently he waited, however deftly he introduced the subject, and

under however much disguise he hid it, the moment his real aim

became apparent, Phineas, talkative, plastic, voluble till then,

closed up like an oyster, and had not a word to say. If they

ever happened to be alone and Simpson avoided the subject, the "old

hypocrite" would hover about it and indirectly refer to it until

Simpson was inwardly raging; but the moment he took the apparent

bait, Phineas was off like a shot and was shyer of the topic than

ever.

The fact was that much of this malicious obstinacy existed

only in Simpson's over-heated imagination; the King's Arms had not

merely got on his brain, it had taken a masterful and exclusive

possession of him—it was meat, drink, sleep, and life to him.

It was undermining self-control, mesmerising judgment, deflecting

even the infallible magnetic needle of self-interest, and slowly

hypnotising the whole man. Hitherto Simpson had lived for the

bobbin business, and just now it was unusually prosperous.

Billy Stiff was no longer available, and the whole of his affairs

rested upon himself. But he sometimes did not go near the mill

for half a day and then, when in alarm and self disgust he

determined to work all night, he found himself long before midnight

sitting staring into the dirty, scrap-filled fire-grate, with his

work unfinished and his thoughts at the King's Arms. He hated

the new landlord with an intensity that frightened him, and yet he

could not bear to be out of his sight; he vowed again and again that

he would never name poultry in conversation as long as he lived, but

in an hour or two he would be deep in the mysterious differences and

comparative excellences of Wyandottes, Plymouth Rocks, and Houdans.

The public-house was still in the heyday of its temporary and

precarious prosperity, and Phineas was handling such unusual sums of

money that he became less and less tractable. The inn was

known to be stocked with liquors, wines, spirits, etc., and Simpson

was on tenter-hooks of anxiety lest the new owner should carry out

any of his fantastic notions with regard to them and thus waste good

money. He had threatened more than once to pour them into the

gutter, but the accident to Billy Stiff had postponed that idea, and

now the objections raised by old Joshua Wenyon's heiress had put it

off again; and all that Simpson could gather was that the ex-cooper

had a notion of selling the more expensive intoxicants as soon as

the lawyer could assure him that it was safe to do so.

Simpson's earnest recommendation of a change of legal adviser was

the only one that Phineas had taken notice of, but even that was

dallied with, discussed fitfully at odd moments, and left.

What added to the bobbin-maker's torment was the curious uncertainty

of his position with the innkeeper in regard to his courtship.

How much did Phineas know, and what was his attitude towards the

question?

In a way the new innkeeper was friendly enough, and seemed to

have forgotten the episode of Simpson's ejection as told in the

earlier chapters. On the other hand, he never let a word drop

which could be regarded as a clue to the state of his mind, and

there was nothing to indicate whether Dolly had told her parents

about her decision or not. It was highly probable that she

had, of course, but there was no evidence of it, and she certainly

had not said anything to them on the occasion of their first "tiff."

As to Dolly herself, he could not make out in the least where

she was in the matter. She still called him "Simmy," and

readily enough gave him details of Billy's progress, but he was made

to feel in many ways that they were simply acquaintances, and that

any attempt to get closer would put them further apart. And

the more be realised that, the more infatuated and helpless he

became. Every male be saw speaking to her became at once a

hated rival. As for Billy Stiff, upon whom every petticoated

soul in the inn seemed to be dancing attendance, Simpson felt he

could have gone upstairs and, hand on windpipe, have squeezed the

very life out of him.

Simpson could not bear to talk to Phineas; his very voice

with its new vain-glorious tones rasped him; but the sight of anyone

else in conversation with him awakened mad jealousy, and made him

feel that he could not endure his tormentor out of his sight.

And the more confused, distraught, and wretched he became, the more

entirely did his infatuation dominate him. He was losing

sleep, appetite, spirits, and self-control; his business just then,

better worth looking after than it had been for some time, was

neglected; he resented by brutal gestures his sister's biting and

somewhat inconsistent reminders, that "a bird in the hand is worth

two in the bush"; and all the while his brain was revolving round

and round the dreary succession of possible schemes, none of which

were in the least new and none of which promised any success.

Never man saw more clearly that he had reached a cul de sac,

but the more he saw it the less power had he to turn away. In

his own house he had become an overbearing brute, at the mill a

testy, explosive, intolerably exacting master, and at the King's

Arms a touchy, quarrelsome irreconcilable, whose gusts of

unjustifiable fierceness were the amazement and perplexity of all he

encountered. One morning about this time, when Simpson had

torn himself away from his unfinished correspondence at the office

and had arrived at the King's Arms, he ran against Jeff Twigg coming

out, and stubbornly invited collision.

Jeff, who had never liked him, made a surly protest.

Simpson flared up, and Jeff began to look glum. At that

moment, however, Phineas appeared on the scene, and, with the

order-keeping instinct of the landlord, interposed his authority.

He told Jeff, who was not speaking, to "'owd his racket," and

elbowed Simpson across the passage into the parlour.

"Simmy," he cried, "there's summat not right wi' thee, thou

gets as sour as a crabapple."

"I'm right enough, there's nowt wrong wi' me."

But Phineas prided himself particularly on his discernment of

character, and so with a portentous wag of the head he replied—

"Come, come! Out wi' it. I've seen it comin' on

for many a day."

They were seated in the little snuggery behind the bar, and

Simpson threw up his bead with a laugh of contemptuous rejection;

but another thought striking him, he blurted out—

"Well, it's you then, an' you're drivin' me mad."

The landlord's little red eyes opened in amazement.

"Me?"

"Ay, you and yours—it's fair sickenin'."

"Simpson Crouch!" and Phineas's red neck began to swell with

indignation.

"It is; it's nasty, dirty pride, that's what it is."

Phineas, red as a turkey, cried, "Out wi' it, man!

Let's be knowin'—or take thy hook!"

"Haven't you squelched me, chucked me over, and all because

you've come into a bit o' property? I should ha' been married

now but for that."

Phineas now understood the situation, but seeing his way for

the airing of a favourite bit of his philosophy, he said—

"Simpson, when thou's lived as long as me thou'll know 'at

women's women, an natteral contrarey. Women," he went on, as

the subject unfolded itself before his mind—"women is like hens, the

more patent layin'-boxes and pot eggs you put for hens the more they

keep on scrouging therselves into awkerd corners and layin' there;

an' it's just like that wi' women, the more you want 'em to be

sensible the more they won't."

"Hez she chucked me over or hez she not?"