|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XVIII.

THE POWER OF CONSCIENCE

SIMPSON

CROUCH would have done

better for himself if he had obeyed his first impulse and stayed

where he was to tell what he knew and assist the others in their

attentions to the stricken man. But to have told the whole

truth would have been to seriously compromise himself, and his

story, however carefully related, would have suggested ugly

suspicions and no end of awkward questions. Moreover, there

had come upon him as he stood in the midst of that terrible scene an

overpowering impulse of protestation, which he realised would be

dangerously incriminating. As he looked at the fallen sufferer

and then at the amazed and wailing knot of servants, he could

scarcely refrain himself; and yet he realised that if once he opened

his mouth there was no telling what he might be impelled to say.

But he would probably have remained there in torturing indecision,

unable to decide either way, but for another circumstance.

Simpson had the soul of a coward and the terrifying consciousness of

evil thoughts; he knew the whole inwardness of the black impulse

that had prompted him to spring at Phineas; and he knew also that

though actual murder was outside the possibilities of such a nature

as his, he had had suggestions and desires which could only be

expressed in one word. He knew how often he had writhed before

the hindrances unconsciously put in his way by the ex-cooper; he

knew how the advantages to be gained by the removal of Phineas,

instead of being suppressed instantly, had been dwelt upon and

magnified before his heated imagination until every lust of his soul

was on fire with unholy desire.

"Conscience doth make cowards of us all," but the already

coward she makes a fright-ridden slave. In three reckless

jumps Simpson cleared the parlour and the lobby; but the moment he

was outside, the white, uncompromising daylight smote upon him like

a furnace. He reeled, staggered, uttered a despairing cry, and

was falling to the ground. But the terror behind was

even-greater than the terror about him; he made a spring that

collapsed into a helpless lurch, and then realised with new horror

that his legs were refusing their office. The faces of persons

at shop doors and house windows all seemed to be looking at him, the

people in the street were all hurrying towards him, the doctor cast

a hurried glance as he passed that chilled him to the bone, and the

very air seemed laden with muttered but vehement accusations.

With bowed head and hand over his eyes he dragged himself along,

every sound he heard being a new accusation.

There was a gate hanging helplessly on the pillar at the

entrance of the mill-yard, but it was so decrepit that it was never

closed. Simpson sprang at it with glaring eyes and feverish

hands, dragged it into its place, and gave vent to a bitter curse

when he found that the fastenings were gone. A delusive sense

that once inside his office he would be safe was moving him, and he

dashed forward; but catching sight of the red wing in Clara's hat,

he turned away with another terror added to his already frenzied

dreams. He glanced towards the wood-shed, but he heard voices

there; he thought of the mill-cellar, but he could not reach it

without passing through the workshop. There was an attic, but

that, like the cellar, was approached only from within, and was the

lightest room in the mill. Then his eyes fell on the old shed,

the coveting of which had been the original cause of his difference

with Dolly: that had rooms in it dark enough; but as the spectral

form of the dead Phineas rose before his mind, he realised that to

be there with that terror would be unendurable. Simpson wrung

his hands in abject misery and looked helplessly round. There

must be some solitude of protecting darkness somewhere. He

thought of the the hayloft, an adjoining plantation, whilst the fear

within him clamouring for concealment almost choked him. Ha!

Yes! That would do! And a moment later he was dragging

his struggling body through a flap of the cellar window.

The aperture through which he had come was the only channel

by which light came into the underground room, but even that seemed

too much. He slunk as deep as he could into the noisome hole,

and as far away as possible from that accusing streak of dimness.

The floor was sticky with slime, the walls slippery and fœtid, and

the air heavy with mouldy, rotting moisture, but he heeded not.

Every sound above and about him sent starts of terror through him,

and in sudden, helpless self-pity he burst into a choking sob and

dropped down upon a log of rotting timber. He tried to think.

If to have an endless succession of maddening visions, each more

terrible than its predecessor, marching like a vast army through his

brain, was thinking, Simpson never thought so much in his life, or

so clearly; but if ordered sequence and the subjection of topic to

will mean thinking, he was never further away from that exercise.

He had no more control of his thoughts than if they had been in

another brain; they pulled him here and drove him there, and rioted

in his brain and nerves without let or hindrance until he scarcely

knew what he was doing. Still as a statue he sat, until the

very rats came out of their holes, and, surveying him with

speculative interest, seemed divided in their minds as to whether he

was anything to be afraid of or not.

The time stole slowly by; the one little yellow streak of day

faded; black darkness settled on the noisome scene, and he still sat

there, the absolute slave of a tyrannical imagination.

It was a curious inconsistency, one of those revenges,

perhaps, of nature, that to his narrow, selfish nature the moral

aspects of the case were the ones that were most insistent.

The thoughts, natural enough some of them, if not exactly innocent,

which he had had about the desirability of Phineas's removal, now

put on the hideous forms of crime and glared at him with inexorable

grimness. These and these only could he see; and though the

kaleidoscopic phantasms changed every moment, they all proclaimed

the same damning fact. Hour after hour he fought with it.

No sound startled him now; the very rats nibbled unheeded at his

boot toes, and the drip, drip of ill-odoured moisture fell on deaf

ears.

A murderer! A very Cain, with the indelible mark of

blood upon him! And he bowed his head, hugged his knees, and

writhed his tortured body until great bursting veins stood out upon

his forehead. Then a flash of suggestion came, and "No!

No! I am not! I am not!" he cried piteously. "It

was a fit, a stroke"—but all at once the tricky phantasm which had

brought the relieving thought vanished, and the gaunt, awful form of

the black impulse that was upon him when he flung himself upon the

innkeeper, and all the dark desires that had lurked so long in his

secret soul, came trooping out like an army of hostile witnesses.

He lifted his head with another bitter cry. What! It was

growing light again; he could see the other end of the room, and a

pale dim beam streamed through the distant window. He sprang

to his feet with a shudder; Nature herself was against him, and the

very sun was coming back to mock his hope of concealment and join

the army of his accusers. He stumbled towards the window,

glanced helplessly around, dropped upon his knees, gathered up a

handful of the black slime on the floor, and hastily smeared it over

the thick glass. Again and again be repeated the operation,

and then, with only the faintest glimmer to guide him, he began to

pace about the room, here and there with wooden pillars and pieces

of rotting timber, until his shins were barked and his whole body

ached.

It was cold down there, but he did not feel it; moist and

foetid, but he did not realise it. Moment by moment he paced

about, now resolving on flight whilst there might yet be time, and

now deciding upon that most impossible of all impossibilities to

him—dispassionate thought. The tramp of feet above him,

followed by sounds of voices and the groaning of the old engine and

shafting, told him that day had come and that the workmen were

resuming their labours. But the close proximity of those who

knew him and must know also of the occurrences at the King's Arms

gave his thoughts another turn. All night the personal aspects

of the case had been with him, but now other elements of the case

came before him, and he was soon deep in reflections almost more

terrifying than the earlier ones. Guilty or not guilty, he was

seriously compromised. He was present, had his hand on the

dead man's throat at the fatal moment, and he had fled. Oh,

the madness, the blind, stupid insanity of the whole thing!

Why had he not stood it out? Why had he not told the truth?

It was the truth, he was not a murderer—but to have been present at

the fatal moment and to have fled! Snelsby at anyrate would

understand one thing, and one only.

That his guilty conscience should have played him this

traitorous trick and caused him thus recklessly and needlessly to

incriminate himself, added new tortures to his already frenzied

brain. This aspect of the case, appealing as it did to his

practical, prudential selfishness, gradually grew before his mind,

and for a time at least overshadowed the other. Of food or

sleep, the moist, mouldy air he breathed, and the flight of time, he

never thought; so absorbed was he with the scene at the inn and

everything it involved, that the question of what to do for himself

was long indeed in being reached. It came at last, however,

and in most unwelcome garb. Action, so often the relief of

crushed minds, is also just as often the refuge of the soul that

dare no longer think. But here, perversely enough, the

necessity of doing something only brought fresh terrors. To go

out in the eye of that staring daylight, to have to encounter the

gaze of his fellow-men and hear their voices seemed impossible, and

for the moment the dark, evil-smelling cellar seemed a very haven of

rest and security. Then he remembered that the key of the

basement was hanging in the office, and that if a search was

instituted for him his hiding-place would be explored and he would

be caught like a rat in a hole.

It was a sign of his condition that he felt they would think

of the cellar at once, though it was sometimes not invaded for

weeks. Any moment now he might be dragged out amid the

reproaches and curses of his outraged neighbours. He began to

listen now for the opening of the door on the top of the steps;

every foot he heard in the room above was the tramp of the

policeman, and every old barrel in the cellar seemed to be

concealing a spy. He dared not go out, he dared not stay; and

the more vehemently he asserted to himself his innocence, the more

black and overwhelming seemed the evidence against him.

The engine stopped for the dinner-hour, the men departed for

their food. But to escape he would have to force the cellar

door or depart as he had entered, and in either case those of his

workmen who brought their food with them to the mill would be sure

to hear him. What must he do? Where must he go?

Innocent! The thought added only a new terror.

And so the hours flew swiftly by, every fear of Simpson's

craven soul gradually coalescing together into one mad desire for

flight. More than once during the last few hours he had seen

amongst the other phantasmagoria of his heated brain the

lotus-eater's face of the demon of self-destruction, and he was, as

yet, healthy-minded enough to shudder at it. And now, as the

fretted hours passed away and the obscure ray from the dim and

smeared window grew fainter and fainter, the whole cellar began to

fill with floating faces and mocking sounds. The sharp red

eyes of Phineas Wenyon began to haunt him, and he heard his strident

tones above the rumbling of the mill-wheels. What other could

he do than flee?

Every attempt he made to justify himself, if he went amongst

his fellows, would only more seriously incriminate him, and his

explanation that Phineas had a fit would only expose him to the

keener ridicule. It gradually grew darker, then black as

midnight; the whole cellar was full of those horrible, haunting

faces. He dared not stay, he dared not go, he dared not touch

his own fingers, out of a frenzied fear that they might be smeared

with blood. Stiff and terrified, he presently felt that he

dared not move; he scarcely dared to think. All was still

above, distant sounds from the town sounded faint and far away, the

rats careered heedlessly about his feet, and the drop, drop, of the

slimy ooze from the walls ceased to be audible to him.

With crouching form and stealthy steps, as though even his

flight were an added crime, he groped his way to the window.

Catching his breath at every sound caused by his own clumsy

nervousness, he dragged himself up and insinuated his body, which

seemed to have a jumping heart in every limb, under the flap.

He pulled himself out of his dungeon and stood with a thousand new

terrors flooding in upon him. Every star in the crowded sky

was watching him; the very new moon seemed to have arrived for the

occasion and to be gleaming upon him in insolent triumph. The

dim town lamps seemed like great searchlights as he stood there,

heartily wishing himself back again in the darkness.

In spite of the time he had spent in that cellar, and all the

thinking he had done, he still had no definite plan; he would like

to have seen his sister, but even she, he realised, would draw the

line at work like this. With a courage feigned to beget

courage, he stole along the mill-side; and as he reached the corner

where he could see the office he pulled up with a smothered

exclamation, for there was a light in it. Of course!

Clara, in his absence, was attending to the business—her

business as well as his. Nothing very terrible had been

discovered, or she would not be there. A sudden pitiful

eagerness to hear even this human voice came over him, and he

started forward, but suddenly the light went out, and as he stood

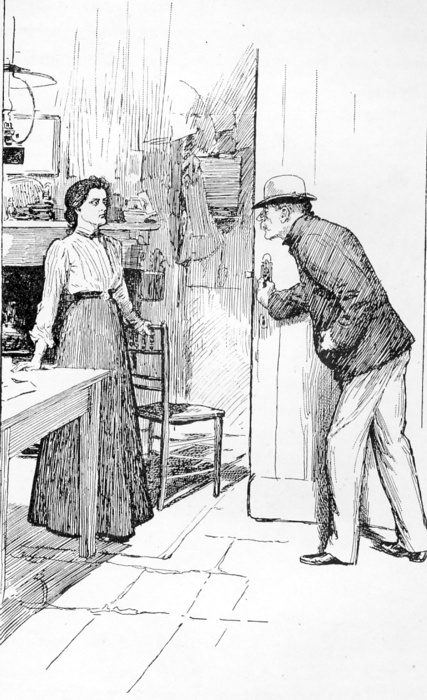

there in confusion the door opened and out stepped his sister.

She started with a little nervous scream, and then, quickly

recovering herself, she remarked in slow, mocking tones—

"Oh, it's thee—at last!"

"She remarked in slow, mocking tones, 'Oh, it's thee—at last!'"

Simpson winced, but there was an insufferable burden on his

soul, and so he asked in abject, pleading tones no louder than a

whisper—

"Is he dead?"

"Dead as a herrin', an' a good job, too."

"Clara!"

"Isn't that what thou wanted, pigeon-heart? But where

has thou been?"

"But—but what are they doing—"

"Doin'? Nothin'."

"Nothin'? No inquest?"

"Inquest? What do they want an inquest for?"

"But—but—didn't—"

"Old Bolus Brampton said he'd died from natteral

causes—apoplectic fit—man, thou looks like a ghost wi' a bad liver!"

"Did they—will they—are they after me?"

"Ay, Phineas's lawyer is after thee."

Simpson sprang back with a suppressed scream, but his

sister's tone belied her words, and so he cried desperately—

"I didn't, Clara! I swear I didn't!"

"No, thou didn't: nobody as knew thee would ever think thou

did"; but the tone was a biting mock and not a reassurance, and

Simpson squirmed again.

"What — what does t' lawyer want wi' me?"

"He wants thee badly, he's sent here twice for thee."

"Will he—has he—is t' police after me?"

"Like enough; he wants thee badly, anyway."

"I—I—I—didn't, Clara, I didn't—what does he want me for?"

"Well, not for murder, as thou thinks."

"What? Say it again."

"He wants thee to execute a will—old Phineas's will."

"Me?"

"Ay, the old rascal made it fifteen months sin' on a sixpenny

form, and he left his wife and Simpson Crouch, his son-in-law as was

to be, executors."

There was mockery and scorn, but a strong under-current of

veracity, in Clara's voice; but her last words were scarcely out of

her mouth when she sprang forward with a half-distressful,

half-resentful cry: for Simpson had dropped at her feet in a dead

faint.

CHAPTER XIX.

SNELSBY SPEAKS ITS MIND

THE startling

death of Phineas Wenyon made a most profound impression upon

Snelsby. This was not the only event of its kind in the

history of the easy-going old town, of course; neither had Phineas

held any such exceptional position in the town as that his death

should receive such extraordinary attention.

Nevertheless, after meditating upon it for twenty-four hours

and sullenly wondering why there was no inquest and duly weighing

all the circumstances of the case, heavy, sluggish Snelsby spoke its

mind. From the parson at the vicarage to Tommy Brick the

caretaker of Jeff Twigg's little Frog-lane chapel, from Mr Willup

the "retired gentleman" who occupied what was once "The Hall," down

to Puggins the cockle-hawker, who walked all the way to Benderton

and back to borrow his brother-in-law's black trousers for the

occasion,—Snelsby made up its mind. The town had never taken

the cooper very seriously; everybody liked him because of his

ingenuous earnestness, his sprightly conversational powers, and his

amusing freaks of conduct and opinion, and his foibles, whatever

they were, were harmless and amusing; and so Snelsby, in its slow,

drowsy way, had liked its old townsman.

But it was not this feeling that moved them now. Those

at all intimate with English rural life are perfectly well aware

that society in our small market towns is often honey-combed through

and through with private drinking, and Snelsby was no exception.

Phineas had never spared his neighbours; some people said he had not

always been as discreet as he might, and complained that he was

personal and made his total abstinence offensive; but all this was

forgotten now, and men remembered only that he had in his own way

sought their welfare. For some time now the cooper and his

movements had been the most prominent topics of Snelsby

conversation, and his fellow-townsmen had discussed every move of

the game as they saw it; but this staggeringly sudden death took

their breath away, and it was only when they got time to think that

there arose in their slow-moving, matter-of-fact minds the great

idea that did justice to the crisis. Without interchange of

thought, without preachment, without committees, or discussions, or

pre-arrangements, there arose in their dull brain the tremendous

fact that Phineas Wenyon was a martyr. He had suffered

for conscience' sake; old Joshua Wenyon and Simpson Crouch between

them had killed him.

Not much was said; everybody seemed to understand what his

neighbour was feeling; a quiet, pensive self-restraint seemed to sit

upon everybody during the few days that elapsed between the

startling death and the funeral. But when the modest hearse

and its couple of simple mourning-coaches drew up outside the

cooperage, Snelsby began to move—softly, decorously, but in most

serious earnestness; and when the lowly cortege passed along the

street there dropped into rank behind it the largest, longest, most

influential, and most inclusive procession Snelsby had ever seen.

Rich and poor, church and chapel, teetotaler and publican, saint and

sinner, were all there, and there was but one conspicuous absentee:

Simpson Crouch knew better than show himself that day in public.

Snelsby, coroner's inquest or no coroner's inquest, had made up its

mind about Simpson; and so the landlord of the Red Lion, of all

persons, had stalked into the bobbin-mill office and warned him that

it would not be safe for him to be seen in the street whilst Phineas

Wenyon was being buried.

"But I'm his executor," protested Simpson.

"Oh?"—and the purple-faced landlord looked astonished.

"Now, look thee here! I'm not a full-fledged cherubim, not

quite; but I know a man—Phineas Wenyon wur a man, totaller or no

totaller he wur a man; and if thou shows thy foxey face i' them

streets to-morrow there'll be trubble."

Only dimly conscious of the great crowd behind, Dolly and her

mother, accompanied by the Twiggs and one or two distant relatives,

made their sad way to the church. Mrs Wenyon's hair had

suddenly turned white, she scarcely seemed to have command of

herself, and spent most of her time in moaning out snatches of

hymns, texts of Scripture, and ancient local proverbs. The

lawyer, secretly much disgusted at having, through the defection of

Simpson, to attend, changed his mind when he saw all Snelsby in the

street, and, riding in the second coach, spent his time in

alternately peeping out of the window at the crowds of bystanders

and then turning to his neighbour and remarking with solemn shakes

of the head, "Remarkable man—most remarkable man!"

The service at the church was made impressive by sheer weight

of numbers, and the vicar scandalised his high-church curate and

immensely gratified everybody else by asking the dissenting minister

to take some part in the simple ceremony. The curate was

pained—it was humiliating to see a man of the vicar's standing

carried away by mere excitement; but when the prayer at the

grave-side was over and the clerk's "Amen" was drowned in a chorus

of similar responses from little Bethelites and others led by

Jeffrey Twigg, the curate glared round with a horrified, helpless

sigh. The last word had been said, a wave of soft, long-drawn

sighs broke over the company, there was an expressive pause, the

young cleric was trying to catch the eye of the bill-sticker to make

him aware of the enormity of his conduct, when suddenly—was he in

his senses? was it not some horrible dream?—he heard the sharp click

of a pitchfork, and an instant later there was Jeff staring him in

the very face and leading his fellow-mourners in one of the oldest

of Snelsby Sunday-school hymns—

|

"Though often here we're weary,

There is sweet rest above," etc. |

The curate shot out a hand and cried in sternest whisper,

"H-u-s-h!" The clerk and the grave-diggers echoed "Hush!" but

all in vain. The music spread, the roll grew deeper; every man

there knew that old Sunday-school tune, though most of them had not

heard it for forty years. The startled look faded out of

propriety-shocked faces, and the owners of them fell softly into the

tune. The dissenters sang it; men who had not been inside a

place of worship for years sang it; the old doctor, choleric and

profane as he was, felt himself dropping into its hum; the vicar

began to sing; and there, at the back of the crowd, the

apoplectic-faced landlord of the Red Lion burst, in spite of

himself, into a snatch or two, and then dodged behind a tree to

choke back his unwonted emotion.

That scene has never been forgotten by any who took part in

it: even the high-church curate tells of it to this day as an

example of irresistible impromptu effect. There was much

blowing of noses and wiping of eyes as the two mourning women made

their way back to their coach; and tongues being now released, there

was more expression of strong opinion about Phineas Wenyon and his

singular ways than Snelsby would have allowed itself to be betrayed

into in a month of ordinary conversation. One thing, however,

soon became apparent: Phineas Wenyon's stalwart self-sacrifice for

principle's sake, now thrown into such startling distinctness by his

tragic death, did more for the cause of sobriety and temperance in

Snelsby than all his labours had done.

The only thing that seemed to have disappointed the

demonstrating voluntary mourners was the fact that the procession

had not started from the King's Arms; this, it was felt, would have

made the thing complete; and many stopped as they returned from

church, and stood in little knots outside the now famous hostelry

discussing the various incidents of the funeral and provoking each

other in vague speculation as to the next act in this exciting local

drama. And certainly there was room enough for much and

various guessing, for the situation was singular enough. As

soon as the terrible fact of her husband's death had been made clear

to Mrs Wenyon, she had fallen into a series of long faints with

intervals of acutest mental agony, and at length had declared, with

another burst of hysterical weeping, that there was a curse upon the

King's Arms, that all the great troubles of her life had come since

she had anything to do with it, that there would be no peace or

safety until they were out of it, and she would not stay a single

hour. Nothing that could be said made any impression; she

insisted then and there upon going back to the old home and taking

her daughter and the dear clay of her beloved husband with her.

The fact that she would thus be leaving her interesting charge,

Billy Stiff, to the tender mercies of the world, gave her pause for

a moment or two; but having disposed of that difficulty by putting

old Jeff in charge of the establishment, and handing her patient

over to Thomasina, she dragged her sobbing daughter away, and

literally shook the dust of the King's Arms off her feet.

The bill-sticker, to whose ungainly height this appointment

seemed to add several inches, at once assumed the office, and with

his face of portentous gravity stalked about the passages of the

inn, alternately dropping down upon some intruder or negligent

servant or joining some kindred spirit in piteous lamentations about

the recent shocking occurrence. The excitement caused the inn

to be very busy and full, and Jeff was correspondingly important;

but when the funeral was over and he got out of the second

mourning-coach and strode into the hostel as manager, with the eyes

of half Snelsby upon him, Jeff felt that at last some little was

being done to recognise his value and to make amends for the past.

It was some time, however, before he could settle down to his

duties; his new black clothes had to be changed, the wonderful story

of the funeral detailed to his wife and the silent but intensely

interested patient; then he was called to partake of food; and so by

the time he was at liberty to look round, the inn was buzzing from

end to end with chattering but good-humoured customers. Jeff

somehow felt that it would be a degradation of his temporary office

to condescend to talk with the customers, but neither his wife nor

Billy could stand any more of his stories just then; and still he

longed to talk, and began to move about the place, seeking means of

getting the desired relief. Passing the end of the bar,

however, he felt himself plucked on the sleeve, and, turning his

head, caught a series of mysterious signals from Miriam, the senior

maid-servant. There were so many signs of secrecy about the

communications that Jeff became very much on the alert, put on his

easiest manner, thrust his hands deep into his pockets, and lounged

up alongside Miriam, who was already busy again in the service of

the customers. In a moment or two she turned, waited to catch

his eye, jerked her finger behind her in the direction of the little

inner office, and hastily hurried away with a tray of tea and

biscuits. The apartment she had indicated was very small—if

two persons occupied it together, it was full; since his appointment

as caretaker, Jeff had mostly kept the room closed. As he

approached the door he heard the clink of money, and as he entered

he beheld the bag in which he had put yesterday's takings tilted up

and half empty on the table, and Simpson Crouch bending over the

coins and counting them.

"Hello!"

"Hello!"

Simpson half unconsciously spread his hands over the coins

and stared defiantly up into Jeff's indignant face.

"What are you up to here?" demanded the suspicious

bill-sticker.

"Minding my own business. What are you doing?"

"Business? It's not your business, it's mine."

"I tell you it's mine."

"But Mrs Wenyon put me in herself."

"The law put me in, I'm the executor."

Jeff stared helplessly at the money-bag, then at Simpson, and

then back at the cash; and catching at that moment an ill-concealed

gleam of triumph in the bobbin-maker's eye, he took a stride

forward, glared down fiercely into Simpson's face, and commanded

thickly—

"Take thy greedy paws off that brass."

Simpson seemed inclined to defiance, but a second glance at

his big opponent restrained him, and he sat back from the table-desk

and slowly rose to his feet.

"Lawyer Setchell gave me instructions, and the law itself

makes me master."

"Then the law makes a thunderin' mistake, and so does the

lawyer; you'll never be master here while your heart's warm, so just

clear out."

"But, Jeff"—Simpson perceived that he must change his

tactics—"it's Phineas Wenyon's own doings; he left it in his will

that I was to be executor."

"Seein's believin'; where's t' will?"

"Lawyer Setchell has it; he's explaining all about it to Mrs

Wenyon this very minute, and I'm responsible for everything that

goes on here"—and Simpson turned towards the money-table again.

"Mrs Wenyon put me in herself," retorted Jeff doggedly, "and

nobody but Mrs Wenyon 'ull turn me out."

Simpson coaxed and threatened and bullied and argued, but

Jeff stuck to his text in spite of all that could be urged against

him, and finally, but with the utmost possible reluctance, he

withdrew and left the bill-sticker in victorious possession.

In a few minutes, however, he was back with the lawyer. Jeff

was tying up the moneybags, and when the man of parchment saw the

kind of simpleton he had to deal with, he put on a brusque,

peremptory air and bade the billposter be careful what he was about.

Jeff went on tying the bag-string.

"Do you know you'll have to give an account to this gentleman

for every penny?"

"If he'll come i' th' back yard and you'll hold our coats

I'll do that now"—and Jeff was getting very red.

"Tut, man! Don't be coarse! Mr Crouch is executor

along with Mrs Wenyon, and has as much authority as she."

"Just as much, and no more?"

"Exactly, equal authority—only you—"

"That's it! She's as much power as him and he as

her—well, I'll take my orders from her."

Simpson broke in here with a not too vague hint about the

police; but the lawyer, checking him, advised him to wait until Mrs

Wenyon was ready to be spoken to on matters of business. Two

days later Jeff, in surliest manner, gave up the keys of the office

to the bobbin-maker, and he and his wife retired to that part of the

big house to which the patient had been removed. Mrs Wenyon

and Dolly were too much overwhelmed with their sorrow to take much

interest in anything; Dolly, indeed, keeping her bed for some days

through severe nervous shock.

At last, some ten days after the funeral, the two women made

their first visit to the King's Arms, and found to their

astonishment that Simpson Crouch and his sister were in full

possession; two of the old servants had already gone and a third was

going, a smell suspiciously like intoxicants pervaded the lower

rooms, and Jeff and his wife were preparing to have the invalid

removed to the tollhouse.

"You see, Dolly," explained Clara as she hurried them past

the public room and upstairs where they could be quiet, "it would

never do to let a parcel of servants run riot in a place like this,

and Simpson felt that he was responsible, and so we thought we had

better come and look after things ourselves until matters are

settled and you are ready."

But Dolly was scarcely listening; her thoughts were going out after

another occupant of the house. Mrs Wenyon, who had declared

twenty times that day she would never come again, looked round with

a fearful interest, and at Clara's suggestion of their return, broke

out—

"Never, never, never! The place 'ud fall down and bury

us both if we came back."

"Ay, woman, I don't wonder; but there's no need to fret,

there's no call for you to do what you don't like to do—Simpson and

me 'ull help you out."

Dolly, usually the most unsuspicious of souls, turned and

looked curiously at Clara, whilst Mrs Wenyon sighingly shook her

head and murmured—

"You're very good, very—"

"Hay, that's nothin'! Simpson is that anxious about you, he

says mill or no mill this must be looked after."

Dolly had another calculating side-look at the speaker, and

they all three began to move towards Billy Stiff's bedroom, Clara

leading the way.

A moment or two later Mrs Wenyon was fussing about the

sufferer and his nurse, putting fifty things to rights which no one

else could take exception to, Thomasina Twig, watching her with

surly jealousy. Dolly, standing shyly by, was trying to find a

corner of the room where her eyes might rest without encountering

those of Stiff; but those great hungry grey orbs of his seemed to be

everywhere and to look her through and through. The sufferer's

leg was reported to be doing " nicely," and his looks, gaunt and wan

though they still were, seemed to justify hope. It was

difficult to get "mother" away from the bedside, and even when she

did allow herself to be led away she felt it necessary to return two

or three times to give instructions to the still taciturn Thomasina,

who took everything so very glumly that Dolly, who had been studying

Clara, was compelled to notice her.

As they were going down the stairs Clara exhorted in her most

affectionate tones—

"Now don't you bother, Dolly, and don't let your poor, dear

mother bother; Simpson 'ull look after things, and everything will

be right."

Dolly, who seemed somewhat absent-minded, nodded a little

vaguely, and Clara, as she watched them go up the high street, had

misgivings about the younger woman's manner which she could scarcely

put into words, but which somehow clouded her face and cast a chill

over her spirits.

No sooner, however, had the stricken widow got back to her

old home than she became most unwontedly restless, sat looking out

of the window without speaking, did not even answer when she was

spoken to, had little outbursts of objectless activity in which she

arranged and re-arranged things that required no attention.

Two or three times she started to go upstairs, forgot herself on the

way, stood staring vaguely at the staircase for a moment, and then

returned helplessly to her chair. Dolly, absorbed in her own

anxious thoughts, noticed little of these things, and it was only

when her mother, bursting into pathetic protests and copious tears,

rushed bareheaded out of the house, that the daughter realised that

something unusual was happening. Dolly rushed after her

parent, but her calls only stimulated the elder woman's paces, and

when she saw that Mrs Wenyon was returning to the King's Arms she

relinquished her pursuit, guessing easily what was the matter, and

began to cast about in her mind for some modification of their

household arrangements which would enable them to entertain the sick

man, whom she now confidently expected. Half an hour, forty

minutes passed, and just as the suspense became unbearable an

extemporised ambulance appeared at the cooperage door, and Mrs

Wenyon, red but triumphant, stood at its side. The two Twiggs

were the bearers, neither of them looking very contented; but in a

very short time they managed to get the sick man's bed comfortably

arranged in a convenient place, 'Siná and Jeff being placated by the

appointment of the former as chief nurse.

Then the little party dropped into general conversation, and

before long Jeff was giving Dolly a highly coloured account of his

altercations with Simpson Crouch, whilst she, an odd silence upon

her in these days, listened with keen but mute interest.

Simpson called next night to see his co-executor on business;

but Mrs Wenyon broke into pathetic protests, and declared that she

never wanted to hear anything of the King's Arms as long as she

lived; and as for Simpson, he could do as he liked, so long as he

did not trouble her.

For the next few days the Wenyons heard little of the King's

Arms, but even preoccupied "mother" could not help noticing that

Dolly and old Jeff seemed to have much secret business together, and

some of the information which the bill-sticker imparted seemed to

give the young lady considerable distress. Then Simpson and

Clara called on a visit of condolence, but the sympathetic part of

the visit was soon disposed of, and in a short time Clara, in her

very blandest tones, was assuring Mrs Wenyon on that she need not

trouble herself, for if she really could not overcome her feeling

about the inn—well, there were several things that might be done.

Mrs Wenyon only sighed, and Dolly maintained her new coldness, and

answered in monosyllables. A little chapfallen, the visitors

felt they could not prolong the visit, and so, as she embraced the

elder woman, Clara begged her not to worry for a moment, as Simpson

had the thing in hand, and would see it through.

"Who does the property belong to now, Simpson?"

Dolly had found her tongue at last, and the simple unexpected

question seemed to rather embarrass the bobbin-maker.

"Well, of course," interjected the cool Clara, "it's in the

hands of executors—trustees, you know."

"Who are they trustees for?"

"Oh, well, of course for you."

And a sudden dropping of the eyes, and an enigmatic "Oh," was

all they could get from the heiress.

Lawyer Setchell called next day. He was first

respectfully sympathetic, then mournful, then profoundly

confidential. He was quite badgered with offers for the King's

Arms, especially as the time for the renewal of the licence was

close at hand. The property seemed a little gold-mine, and he

supposed the prices offered were inflated by competition—well, so

much the better for the fortunate heiress.

Dolly, grave and still, had no answer.

The most respectable to do with and those who had made the

best offer were Ling and Medway, the county brewers. Perhaps

Miss Wenyon would like to see the letter. No?—of course not;

ladies knew little of these things, and in times of sorrow—but if

she cared to leave the matter with him and Mr Crouch—

"But the property is mine."

"Yes, oh, yes, certainly."

"Well, I don't intend to sell."

"No? Oh, indeed,"—this with dubious

side-glances—"manager, eh? Well, on the whole, you are right,

quite right."

"I understand the property is mine free from any of the

restrictions that bound poor father."

"Yes, of course, you can sell, lease, or do just as you like;

it is a nice little fortune if it is nicely managed. Your

father was—er—did not leave you very much, I fear?"

"Yes, he did—he left me his example, his principles, his pity

for poor drunkards, and his hatred for drink; and what he would have

done, I shall do to the very letter."

The next consultation between Simpson and the man of law was

not a pleasant one, but both of them were surprised and piqued to

receive invitations to meet the heiress at the King's Arms on the

following day. She came accompanied by the bill-sticker; and

as the appointment was of her making, they waited for her to

introduce the business.

"Gentlemen," she said, after a pathetic little effort at

self-command, "you tell me that this place is mine. I am, my

father's daughter, and, knowing his wishes, I will neither sell the

place that others may make a drink-shop of it, nor will I allow

anything of the nature of intoxicants to be sold on the premises.

Already my father's arrangements have been tampered with, and drink

has been given away, if not sold here. This cannot continue.

Phineas Wenyon's teetotalism is not dead whilst his daughter lives;

and to make sure that the King's Arms shall never be a

drinking-place drinking-place again, I have selected a new manager";

and here, with a confiding little gesture, she laid confiding her

hand on Jeff's arm, and looked them both in the face.

CHAPTER XX.

THE REAL BILLY

"BUT what does it

all mean, Mr Setchell?"

"It's there, miss, in plain figures, and you don't need

anybody to teach you, you know," and the lawyer sat back with a long

sniff and stared hard through the window.

"Well, but, what is the point? Why are you so very

serious?"

"It means that the expenses of the King's Arms as it was

conducted by your father so seriously exceeded the income that the

estate is—well, to put it bluntly—insolvent."

"But we've the cooperage."

"Your father's foreman, supported by your father's chief

customers, the brewers, has already set up business for himself."

Dolly thought rapidly, but with a sinking heart.

"But we cannot be insolvent. We have the King's Arms."

"Precisely! And if sold now to the highest bidder it

would pay all your father's liabilities, save his name, and still

leave you enough to live upon."

"Couldn't we get a mortgage or loan or something?"

"Yes, I could arrange that if you would make the security all

right by renewing the licence."

"Is that the only way? And if I don't agree?"

Setchell shrugged his shoulders. "If you don't agree,

and I tell the creditors—the bank, for instance—that you will do

nothing, they will take legal proceedings at once. Principle

is all very well, but common honesty wears better." |