|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER IX

THE NEW LANDLORD RECEIVES A CHECK

BEFORE Dolly had

been gone five minutes from Simpson's dingy office, that wise young

man was aware that he had made a most terrible mistake. He did

not as yet realise the full extent of it—it remained for his wiser

sister to show him that; but without being able to see all the

reasons of it, he felt acutely self-condemned. Dolly had come

upon him when he was in the very height of his first wrathful

ragings over the just discovered freak of the fantastic cooper, and

if ever a man had just cause for strong language, surely it was he.

All those beautiful dreams, involving as they did £3000 in hard

cash, had been wrecked in a moment, and wrecked by a hopeless,

whimsical fad. It was intolerable, it was simply maddening;

and any words or deeds almost were justifiable under the

circumstances. But one of the first maxims of his sister and

mentor's philosophy had always been, "Have your feelings by all

means, and indulge them, but never to the injury of your own

interests," or, as she more idiomatically put it, "Don't cut off

your nose to spite your face."

Hitherto he had had such reliance on Dolly's transparent good

nature and amiable pliability that he had never seriously doubted

his power to recover his position with her; but his reckless words,

the hottest and rashest he could command at the moment, must have

stung her to the quick, and there was no knowing what undiscovered

depths had been reached or what latent propensities awakened.

If she had any trace of her father in her, the case was as good as

lost, and even on her mother's side independence and dogged

self-reliance were not unknown.

Excuses for his conduct were plentiful enough, but

unfortunately they did not alter the facts; every door of hope was

now closed, and—oh, bitterest thought of all!—by his own hand.

Simpson feared nobody on earth as he feared his sister; she never

spared him, but always insisted on dragging out every detail and

remorselessly showing its egregious folly. She would talk in

low but biting tones, such as no one else dare use towards him; but

she was wedded to his interests, was secretly his legal partner in

the bobbin business, and was the heart and brain of the whole

concern. For good or evil he could not do without her, and to

her he must sooner or later go. But he could not face her at

once; in vain endeavour to find some palliating circumstance in his

tantalising situation, he took a long walk in the lanes, turning the

matter over again and again in his slow, unfertile way. There

was no hope anywhere; he had quarrelled with the father, quarrelled

irretrievably with the daughter, and the extinction of the King's

Arms licence was already an accomplished fact. What was there

left to cling to or scheme for? What possible peg of hope on

which to hang? Unfortunately, the one inevitable thing to

do—namely, give the matter up—was impossible to him; he had dwelt so

long on the alluring idea of possessing this lucrative inn that he

had become a slave to it, and the more hopeless the situation the

more doggedly he clung to it. As he walked about and pondered,

stopping every now and then to curse his own folly, the thought of

his sister grew less fearful, and presently he found himself

desiring that which, under less depressing conditions, would have

been repugnant to him. Just on the edge of dark, therefore, he

turned indoors, and sitting in their small living room, his face

mercifully screened by the gathering shadows, he poured out his

dismal, self-accusatory story.

Now, Clara Simpson was what is known as a sharp woman.

Her features taken singly were passable enough, but the sum of them

gave the impression of acuteness. She had sharp eyes, a long

sharp chin, sharp ways, and a hard, sharp sort of voice. More

than one man had fancied her at first sight, but nobody who could

help it kept her company long. She had already heard—trust

her!—of the ridiculous dénouement at the King's Arms, and was

sufficiently sobered thereby to give her brother a patient hearing.

Simpson seemed to find a sort of perverse satisfaction in telling

every detail, and was a little piqued to see how coolly she took

things. But when he came to his last scene with Dolly, there

were signs enough. She sniffed, she laughed in short

incredulous snatches, she grinned, and finally she settled down into

grim, tight-lipped silence. She was quicker always than her

brother and very much deeper; she was a woman also, and had long

since taken the measure of things with regard to his relations with

Dolly. That the cooper's daughter had never been really in

love with Simpson was as clear to her as anything could be, and she

realised, as even he could not, how tremendous were the difficulties

his impetuous rage had created. It was exasperating to realise

how shockingly the thing had been bungled, but she was shrewd enough

to see that she could not help matters by interfering herself.

It was her incessant nagging about that old shed that had egged

Simpson on to the course which had been the first cause of the

lovers' estrangement; and as nothing makes us so angry with our

confederates as their blamelessness, she felt so bitter and

resentful that she could not trust herself to speak, and there was a

long and painful silence.

"Every day they stop in that house knocks a hunderd pound off

its value," she said at last with grimmest conviction.

"And every day there's another chance for somebody to get a

licence in its place," he retorted sullenly.

"That great rambling shop is worth precious little without

the licence," she snarled, as though Simpson had extinguished it.

"It's worth fifty pound a year less than nothin'," was the

sour rejoinder.

"That an' his crazy fads 'ull ruin him," said she.

"The sooner the better," he replied.

It was no use: chagrined and baffled, they were both

perversely longing for and drifting towards an explosion which would

only make matters very much worse; and so Clara, having nothing to

suggest and needing time to think, got up and left him; and he,

chafing and moody, lusting for a quarrel he knew he dare not

commence, lounged out of the house and down the street in the

direction of the hated but hypnotically attractive public-house.

But in a few minutes he was back with news. His face, as he

told it, was eager and hungry, though dubious shadows lurked in the

corners; whilst she, listening with stony grimness, was maliciously

and quite successfully trying to keep all expression out of her

countenance.

His first announcement was that the two chief local brewery

firms, whose business Phineas and his predecessors had done for

generations, had peremptorily withdrawn their custom from the

cooper, and were negotiating with Bob Dribble, Phineas's foreman, to

start business in opposition to his master. But this was only

what might have been anticipated; and as Clara could see he had not

told all his tale, but was keeping the most interesting item back,

she looked bored and wearily patient, and so he was compelled to

deliver his more important news. That, when it came, was

suggestive and exciting enough. Phineas's lawyer had sent his

chief clerk over from Benderton to say that Mrs Polling, old Joshua

Wenyon's housekeeper and heiress, was disputing the cooper's

interpretation of the will, and that, pending the decision of the

legal point thus formally raised, Phineas had better continue the

usual business of the public-house.

Clara listened without a sign of emotion; and though Simpson

waited eagerly enough for her verdict, he was disappointed, for

after hearing all he had to say and appearing to attend more as a

matter of reluctant politeness than interest, she turned away with a

curling sneer, a face of wood, and an aggravating and inscrutable

"Humph!"

CHAPTER X

THE NEW SIGNBOARD

"TRUBBEL, missis!

Hay, bless yo, they may be handy for odd things nows and thens, bud

they're terble things to live wi', is men-folk."

Mrs Wenyon wagged her head in sententious resignation, whilst

Dolly, sitting, not in the best resignation, of spirits, at the

window of the back sitting-room, stitched away and listened absently

to the conversation of the elder women.

"I'm druv out of my own best feather bed as my mother left to

me, an' sleepin' on a flock turn-up as is as hard as nails, while

he's rawlin' and bawlin' all night o'er wi' a merry-anderin

jackanapes."

"'Many are the afflictions of the righteous,'" moaned Mrs

Wenyon with solemn sympathy.

As the reader may have conjectured, the visitor was Thomasina

Twigg, who, having formerly served in the cooper's family as

char-woman, still kept up her connection with the house, Mrs Wenyon

being her chief earthly confidant. Her real motive in visiting

the King's Arms was curiosity to see her old friends in their new

quarters, and hear from their own lips the wonderful story which was

filling all Snelsby with rumours and reports. Having

commenced, as a kind of introduction, the tale of her own most

recent domestic troubles, however, the topic had become so absorbing

that she had apparently—but only apparently—forgotten her original

errand. In her own odd way she was as much attached to their

queer lodger as her husband, but she would not have been a true wife

if she had not had some chronic grievance against her lord and

master; and having opened upon that, she was postponing other

matters, and Mrs Wenyon's sympathy was supplying the necessary

stimulant.

"When he's in them tantrums, bless yo, he bawls out his

pothry an' rubbitch, till my pore head rings like Jeff's owd bell;

an' hay—it's plain trewth, missis—that, there big lollopin' man o'

mine gapes at him wi' a mouth like a funnel, an' calls it Scripter."

"What does he—what is the poetry like, 'Siná?" asked Dolly

from the window.

"Like, woman? Hay, don't ask me that! No dacent

female—hay, I wodn't sile my mouth wi' it for all Snelsby!" and the

two wives turned reproving faces towards the inconsiderate Dolly as

though she had suggested something indecent.

Dolly turned towards the window to hide a light blush and a

smile, and Mrs Twigg, returning to her older and more discreet

friend, went on—

"He gapes at me, an' rowls his eyes, and calls me the

wickedest names!"

"What does he call you?" asked Dolly the daring.

'Siná turning a grieved, scandalised face upon Mrs Wenyon,

lifted her hands in holy horror, and "mother" elevated her brows and

returned the look with compound interest, as though the

communication she was making out of pure compulsion was only fit for

maturely discreet ears. 'Siná dropped her voice, and looking

hard at the new landlady, she proceeded—

"He calls me Florey an' Goddess!"

Mrs Wenyon shook her head in slow but very decided

disapproval, and Thomasina, secretly revelling in the double

delights of sensation-mongering and minor martyrdom, went on—

"Bless yo, missis, I'm just nowt at all now! That there

lump of a man o' mine might never have no wife. He goes out wi'

him an' he come's in wi' him, he preiches to him an' he cries over

him, he gets him down on his knees an' he convarts him; he fetches

pledge-books out of his Pocket an' he signs him, an' there's his

poor wife as never says a word, an' he taks no more notice of her,

not if I wur a hocksioneer's bill!"

There was a short pause, Mrs Wenyon sitting and looking with

sorrowful pity on her visitor, and Thomasina shaking her head and

sighing in mute appeal for adequate sympathy.

"But why should he? Who is the fellow?" asked the

cooper's wife at length.

"He calls him 'my wandering child' an' 'my prodigal brother,'

an' sitch like rubbitch," replied 'Siná with an air of quoting what

she did not for a moment pretend to understand.

"But why should you be upset an' bothered with him?"

"Hay, bless yo, missis! that's moor nor a boss knows 'at's a

bigger head nor me."

"But he's nothin' to you; you're not compelled to keep him?"

"He keeps sayin' as he'll ha' ta' give in, an' onct he did

give in and sent him packin', but, bless yo, when he came in t'

house, he seed one o' my texes, an' ran after him an' brung him

back."

"And what was the text?"—this very quietly from the

venturesome Dolly.

"Summat about 'turnin' a sinner' an' 'multichude o' sins.'

It's blue and red readin' wi' a yaller ground," and 'Siná supplied

the abbreviated quotations as though they were of no moment except

to make confusion more confounded. But Dolly, who was

unusually tender that morning, blinked her eyes rapidly.

Mrs Twigg was still dwelling on her many delicious

tribulations, and as neither of her friends replied to her, she

began to search her memory for more pity-exciting details; but

arriving by mental processes peculiar to her sex, and which we do

not for a moment pretend to be able to follow, at another aspect of

the case, she resumed—

"I'm not sayin' as he isn't good-lookin'. Hay, woman,

he's dreadful nice an' kind when his figarreys is off him! "

"But why does Jeff bother about him?" asked Dolly, more to

conceal than express her interest.

"He say's he's his cross an' mun be carried," and then she

added, with an aggrieved glance at Mrs Wenyon, "Our Jeff's like a

lot o' moor folk; he likes crosses as other folk has to carry."

But the moral aspects of the case evidently did not interest

the younger listener; she was dwelling upon other things, and the

trend of her thoughts peeped shyly out of her next remark.

"He is a freak. I've seen him once—er—a—you

haven't a summer-house, have you, 'Siná?"

"Uz? Nay; bud bless you, woman, it's only his ravin's;

it's all about 'beauty's bleeching bower' an' honeysuckles an'

Beatrices, an' sitch like jabberings. Hay, woman, it's

pitiful! It's flowery goddess an' bowery goddess, all—Oh, eh?

what!"

The interruption was caused by the blustering entrance of the

cooper, who, inflated with excitement and conceit, came in to invite

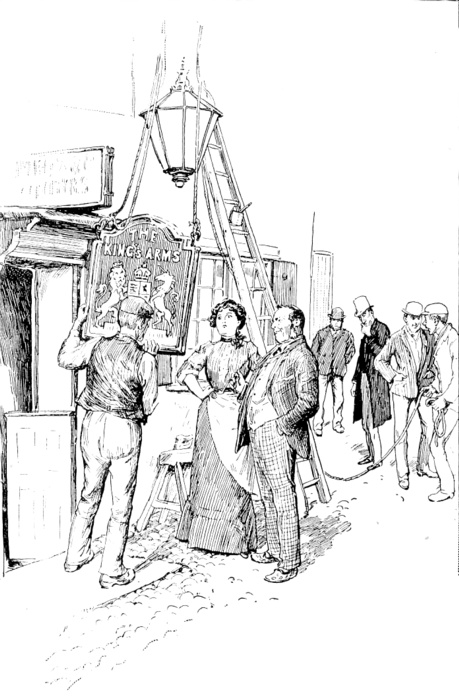

his women-folk to inspect his last caprice. All that day

Phineas had been standing or sitting about in front of the inn

holding at arm's length a long churchwarden, basking in the double

rays of summer sun and sudden popularity, and superintending the

operations of workmen who were replacing the signboard which had

been previously removed to be touched up and re-inscribed. The

King's Arms stood some way back from the road, and the open space in

front was paved with cobble stones. The fine old

black-and-white structure had been recently repainted by the now

deceased owner; but as the signboard had not been finished when he

died, Phineas had stopped operations upon it, and then started them

again in a great hurry and under a sudden and most wonderful

inspiration. The putting up of the signboard, therefore, was

the finishing stroke of his grand coup, and he had called his

women-folk out to behold its glory.

The bracket upon which the sign was to swing hung over the

low, wide front door, and was just being hoisted into its place.

Little knots of interested spectators stood about, all intent on the

business in hand, and Dolly, who was in front of her mother, noticed

at once that old Jeff Twigg and the ridiculous Billy Stiff were

amongst them. But her father was claiming her attention for

the board. One side of it was emblazoned with a newly gilded

picture of the Royal Arms, but the spectators were all screwing

their heads round and scrutinising with incredulous laughs the

reverse side. Dolly, following their eyes, stepped out of the

door to look for herself, and, as she did so, came all unconsciously

under the bracket to which the sign was to be raised. The men

had already commenced their task, and with little shouts were

raising the great sign from the ground.

"Now then, woman, look at that! There's poethry for

thee, there's compressed philosophy!" and Phineas pushed his

daughter forward so that she could read the inscription.

|

"Stop! good traveller, stop and think,

Do not sell thy soul for drink

Tea or coffee, milk or cake,

Safe and sober, come and take." |

"Now then, woman, look at that! There's poethry

for thee."

The board, now being steadily hoisted by willing hands, rose

gradually until the rhyme came on a level with her eyes, and she

could read easily. Her father stepped out upon the cobbles to

direct operations, and Dolly, turning an amused face to the crowd,

caught the watery eyes of Billy Stiff fixed upon her with wondering

stare. He seemed unconscious of everything but her, and did

not seem to know even that she was observing him. The colour

began to rise into her face, and her glance fell to the shabby and

grotesque garments he was wearing. The men at the signboard,

some on ladders, some on the ground, were tugging away at their

work, and Phineas was shouting out his orders in excited tones.

Suddenly, without the slightest warning, Dolly saw the crazy

Billy spring at her with a scream; with hands spread out, he sent

her staggering back into her mother's arms. There was a series

of startled cries at the same instant, a terrible crash and a chorus

of groans, and Dolly, turning her head and looking at her feet, saw

the great signboard on the ground, and Billy Stiff lying by its side

with both legs underneath it. And as she stood there pallid as

a sheet, sick at heart, and shaking from head to foot, she caught

one momentary glance of triumphant adoration from the prostrate man,

and realised with feelings too deep for words that the poor,

half-crazed drunkard had saved her life at the risk of his own.

CHAPTER XI

WHEN GREEK MEETS GREEK

THERE was no love

lost between Simpson Crouch and his sister. They were too

intensely selfish and too much alike for that; and as he was a man

and doggedly insisted upon his man's prerogatives, in spite of the

irritating consciousness that the grey mare was the better horse,

and she was perfectly aware of her intellectual superiority, and

found an outlet for her chronic disappointment with life by

incessantly demonstrating that superiority, their intercourse was,

at the best of times, a precarious sort of thing, and useful chiefly

as a vent for spleen; whilst their conversations were, for the most

part, made up of acrid and spiteful interchanges. But they

were necessary to each other; their interests were identical, their

little heritage from their parents was all in the bobbin mill, and

they were neither of them able either to live without it or pay the

other out. Dull and narrow, they were both possessed of the

small man's inevitable ambition, the love of money; and so the

King's Arms, with its attractive and secure profits, had laid strong

grip upon their limited imaginations. The coveted thing had

come so tantalisingly near, and might so easily have been theirs—at

least in prospect—that they had a deep sense of injury, felt they

were being robbed, and that Phineas Wenyon was a monster of

exasperating stupidity. The more they thought, therefore, the

nearer and more desirable became the coveted hostel, and the more

maddening the sense of helplessness with which they racked their

brains for possible schemes of recovery. The most galling

consideration now was that of time. If all had gone well with

the courtship they could at the worst have waited, but every day the

King's Arms did not transact its ordinary business its value in the

market was depreciating, and, what they were even more afraid of,

the chances of someone else getting a licence in its stead were

increased. Neither of them, therefore, slept much on the night

of the conversation recorded in Chapter IX; and when they met in the

little parlour next morning, Simpson had thought of nothing better

than a hazy plan, beset with difficulties, of setting up a rival

ale-house himself, whilst Clara's many emotions had concentrated

into indignant contempt at her brother's inexcusable bungling.

Eyeing each other askance, each hoping the other had

something to suggest, and each resenting the other's dumbness, they

sat down to breakfast and ate their food in ominous, thundery

silence. But Simpson knew by past experience who would have to

commence, and knew also who would be most likely to have a

practicable suggestion; and so, perfectly aware through what

disagreeable recriminations he would have to come at what he wanted,

he bent his head over his egg and bacon, and growled—

"I haven't slept a blessèd wink."

"Of course! I've slept like a top."

The acrid satire of the first sentence stung him to the

quick, but the cool falsehood of the second struck him dumb again,

and so, after watching her as she nibbled with mocking daintiness at

a bit of bacon on her fork, he snarled—

"Thou'd sleep in an earthquake. Thou hasn't brains

enough to keep awake."

Still playing with her bacon, holding it out and inspecting

it dreely, and then putting it to her lips as though to kiss it, she

smiled a smile that raised a very devil of passion within him, as

she answered in slow, rasping mockery—

"No, nor I haven't fooled away three thousand pounds."

Even this bitter creature winced as she finished her

sentence, for all the black blood in his nature rushed into his

face, and it looked as though his reply would be a brutal blow.

With a desperate effort, however, he choked back his passion,

glaring across the table and trying vainly to catch her eye.

But when he succeeded he failed; for the hard, cold insolence in her

eyes was too strong for him, and she relentlessly looked him down

until his eyes dropped to his plate again, and there was another

uncomfortable silence.

It took him some time to collect himself; but the crisis was

too acute, the thing at stake too precious, for trifling. He

was fast reaching the condition also in which he could not help

himself on this question.

Some day it might be his turn, but the situation was

desperate, and he could not do without her. His voice,

therefore, was subdued, almost appealing, as he said—

"What's t' use o' cryin' over spilt milk?" and then, raising

his voice for emphasis, he added, "What mun we do?"

Slowly, with demurest face, she looked at him, turned her

head away and affected to be considering; and then, glancing round

at him again, she remarked with a blandness more biting than the

bitterest sneer—

"Dolly's a nice soft-hearted lass. Go an' cuddle her

an' make it up."

"Spitfire! Baggage!"

She did not seem to hear him, but was still busy with her

thoughts; a smile of gentle indulgence, followed by the shadow of

mild disappointment, played about her mouth.

"Well, then, Phineas is an easy-going chap. Anybody

that likes can twist him round their finger, an' he's never violent,

is he?"

This was the first hint he had had that she knew about his

ignominious ejection from the cooperage and choking with inward

rage, he made a snatch at his fork and a plunge forward as if to

drive it into her. She did not move; she did not even look at

him; and as he struggled with his surging passion, she leaned her

head on one side consideringly and said—"How would it be to blow t'

owd chap's brains out and run off wi' her in a carriage an' pair wi'

a pistol at her head like they do i' th' tale books?"

"Huzzy! Vixen!" and he was on his feet and standing

over her with clenched fist and blazing eyes. "Get her!

I'll get her now to get rid o' thee!"—but she was on her feet also

and surveying him with white, sneering, insolent face.

"And doesn't thou think I know? Haven't I seen it from

t' first? It isn't her thou wants; it's me thou wants rid on!"

And Simpson stared at her stupefied. The fact that she

had so accurately read his deepest thought amazed and intimidated

him; it was another proof of her intellectual superiority, and

seemed to suggest something uncanny.

But the cat was out of the bag now, and, spiteful though she

was, she was essential if anything was to be done; and so, dropping

his voice again and sinking back into his chair, he said sulkily—

"What's t' use o' talkin'? Show me t' way out, an' then

splutter as thou likes."

"Me! Me! I'm a poor brainless woman," and then

she stopped to think, and presently, turning to him once more, she

said, looking him calmly in the face as she did so, "Whatever thou

gets fro' me now, Simmy, thou pays for."

"Pays for?"

"Ay, pays for. The day thou gets t' alehouse I get t'

mill!"

Simpson, on his feet once more, moved a step back; and if a

look could have killed her, she would have dropped at his feet.

As it was, she folded her angular arms with a cold indifferent smile

and returned his stony stare with interest.

And Simpson, realising that his only hope was in her sharper

wits and greater daring, sullenly yielded; and then and there, in

the sweet light of that early autumn morning, they made their sordid

bargain, and Simpson went off to the mill.

CHAPTER XII

CLARA'S OPPORTUNITY

SIMPSON gone,

Clara sat down to make a detailed examination of the bargain they

had just struck and to further ransack her brains for a scheme that

would put her brother into possession of the King's Arms. But Clara

could not think quietly; she was one of those with whom physical

activity is the best stimulant to mental fruitfulness; to sit down

and give herself up to any one subject was the surest means of

driving that particular topic from her brain and inviting a

confusing rush of distracting thoughts as far away from the matter

in hand as they could well be; and so when the writing was finished,

and she had tried vainly to collect her ideas for several moments,

she rose to her feet and began to move rapidly about the house, her

hands mechanically employed with her daily duties and her brain at

work on the problem of the hour. Her face was clouded and did not

improve; for the situation, the more she surveyed it, became

increasingly depressing each moment.

It might be possible to undo the mischief between her brother and

Dolly. She burned to do something in the matter herself; but simple

and pliable though Dolly Wenyon was, she was still a woman, and

Clara sighed as she realised that only Simpson could repair

Simpson's blunder. With the ex-cooper the prospect was not much more

encouraging, especially as time was the all-important consideration. Phineas was to her a conceited pharisee; and though he was weak

enough on the point of his foibles, he had never shown anything but

veiled dislike of her, and his suspicions would now be alert as

another consequence of her brother's miserable mistake. She realised

also that what she supposed the new innkeeper would call his

"principles" would be very strong, and he was just now basking in

the genial rays of a wonderful popularity as a consequence of

maintaining them. And suppose she succeeded—suppose Simpson got back

into Dolly's favour and the two were married—Phineas was as stubborn

as a donkey, and, inflated with pride at the sensation he had

caused, he would be less tractable than ever, and the flattery of

the public would only make him more and more pigheaded.

There seemed

little chance, therefore, of their getting possession of the

alehouse during the cooper's life; and he was hale and hearty, as

sound, apparently, as a nut, and of a notoriously long-lived family. The more she brooded the more cheerless the outlook appeared, and it

took all her native tenacity to keep down despair. She belonged,

however, to the sex which takes courage from despair itself, and,

having all a woman's reserve of superstition, she clung to the

belief that when things are at the worst they mend, and so continued

her plottings. Between whiles she had the usual daily callers, and as

she was an inveterate gossip, she held long "cracks" that day with

everyone who came to the door. The postman was full of news, but it

was all old and all glowing admiration of the cooper, and so he was

curtly, almost rudely, dismissed. The milkman was a misanthrope, and

came brimming over with cynical contempt for the cooper and his

achievements, and so, though his news also was somewhat belated,

Clara parted from him with something approaching to hope. The

greengrocer, however, had something to tell. The cooper was for

defying the law and continuing the temperance atmosphere at the inn,

legal or illegal; he was also threatening to dismiss the local

lawyer who had given him the advice about not interfering with the

regular business of the place, for pusillanimity; and so far from

being intimidated by the conspiracy of the brewers to take his

ordinary business away, he had determined to take the bull by the

horns, burn his boats behind him, and offer the cooperage as a going

concern to the highest bidder. Clara, listening eagerly to the very

tortuously told tale, thought she saw a gleam of hope, and

astonished the hawker by paying the price he asked without so much

as a hint of bantering.

"Why, yes, of course," thought Clara, "the more they persecute and

bully Phineas the more obstinate and reckless will he become." But

law meant money, and whatever he got by the sale of his old business

would be swallowed up by law in no time. Phineas, though living

easily out of his trade, was never known to be a saving man or a

capitalist, and had certainly nothing to spare for expensive and

protracted litigation. If rumour was to be trusted about old Wenyon's middle-aged heiress, she would be as stubborn as Phineas

himself, and she would be shrewd enough to know that with her longer

purse she could wear him out. Dolly's father was exactly the man to

stick at nothing and to fight until he was ruined. But law was

notoriously slow. The more money Phineas had the longer he would

struggle, and every day thus wasted took so much off the value of

the much-coveted hostel. It would be months, long months, before the

end came, and even if Phineas won, the public-house would be

comparatively worthless, for somebody would be sure to get some

other premises licensed in place of the old inn. But if Simpson

married Dolly and became a sort of partner in the case, Phineas

would insist on him lending money to continue the struggle, and

every day the thing went on her brother would be more seriously

involved, whilst the chances of recouping himself would be growing

smaller and smaller. Phineas was at that moment the most popular man

in Snelsby—with the religious part of the population at anyrate. If

they saw him suffering for conscience' sake they would rally to his

support, make collections and what not, and thus prolong the

conflict. Moreover, the religious folk in the town were what Clara

called "downy," quiet-living, frugal people, and she suspected that

most of them had sly, fat old stockings somewhere, and that these

might be placed at the cooper's disposal. Whatever, therefore, was

done by Simpson and herself must be done at once, for, having

unlimited faith in the power of money, she realised that Mrs Podling

could wait and wear opposition out, and must therefore inevitably

win; but if she and her brother were already committed to the

ex-cooper's schemes, their money as well as his would be spent, and

spent to no purpose.

Oh! it was an exasperating situation, full of risks and tantalising

allurements. 'Twenty times that morning Clara told herself that

there was nothing for it but to accept the inevitable and let things

go; twenty more times she argued with herself that she and her

brother ought to be thankful that they were not already involved,

and could wash their hands of the miserable business altogether. Three months earlier she would have decided upon this course without

a moment's hesitation, and taken means to ensure that the separation

of her brother from his sweetheart should be final; but since the

fatal moment when the vision of the fat, well-established King's

Arms had floated into her vision and laid upon her its soft but

ever- tightening grip, it had obtained a mastery over her she did

not herself realise.

The more she reasoned with herself, the more prudent and sensible

became the course of abandoning their project, the more tenaciously

did the lust after possession hold her; and the more cool judgment

showed reasons for caution, the more did strong desire settle itself

down in her heart and lay its strong, relentless hold upon her

imagination.

Temptation begins as an enticing, conciliatory, accommodating

playmate, and ends as a jealous tyrant. As the day wore on she

became absentminded, limp, drooping, her natural

decisiveness changing into petulant hesitation. In Simpson's

presence she preserved a sullen, repellent silence throughout the

whole dinner-hour, and in the afternoon indulged in the—to

her—unwonted luxury of a good cry. But all day long the King's Arms

was there, its comfortable promise of competency bulking out large

in her mind; and whilst the slumbering fires of her hatred burned

hot against the Wenyons, the income from the public-house—at least

double their present resources—grew fairer and fairer to her mind.

She did not forget that she was on her mettle. She had mocked her

brother's hesitations so remorselessly that if she would retain her

dominion over him she must justify herself. Cold prudence gave its

monotonous and depressing verdict of "hands off," but ordinary

hereditary cupidity had suddenly grown into ungovernable lust of

possession, and she was being pulled every moment in contrary

directions and almost torn to pieces with conflicting desires. Presently she rose from the bed upon which she had thrown herself

and began to stare drearily out of the window.

Then she slid to the floor, moved waveringly towards the

dressing-table, played for a moment or two with the knob of a small

drawer, and then took out a little key from her bosom. A moment

later she was sipping at a glass of water into which she had dropped

a few drops of a seductive drug, not unknown to fashionable ladies. This she drank with an uneasy self-conscious look, and half an hour

later, with eyes of suggestive brightness and mind clear and

hopeful, she was leaving her residence without any fixed purpose,

perhaps, but with a brain open and eager for any "lead" which luck,

fate, accident, or Providence might provide.

A sense of the hourly diminishing value of the coveted ale-house was

urging her one way, and the knowledge that it was as yet too soon

for Phineas to feel his need of help was pulling her the other, and

at the same time she was perplexed with misgivings that they might easily place themselves in circumstances worse even than the

difficulties of the moment. She left the house just about the same

time on the same day that the King's Arms signboard was being raised

to its place; but not having any definite plan as yet, she made two

or three calls, and it was some time before she heard of the

accident. The news, however, had an instantaneous effect: she did

not as yet see what use might be made of the occurrence, but, at

least, the fact that the injured man was her brother's clerk would

give her a sort of right of entry to the public-house; and so away

she went post-haste, cudgelling her brains as she hurried along for

some scheme whereby she might take advantage of the opening thus

presented.

Meanwhile, all was excitement and consternation at the inn. Old Thomasina Twigg was the first to spring to Billy's relief, and began

tugging the heavy signboard with lamentations and pitiful words of

sympathy, which, remembering her recent speeches to Mrs Wenyon and

Dolly, did more credit to her heart than her consistency. Phineas

and the painter's men were at her side instantly, and had the board

lifted away from the crushed and prostrate Billy before the

onlookers had recovered from their shock. But the greatest

transformation was that which took place in the new landlady. Slow,

heavy, and pensive as a rule, she suddenly became another person. Dolly, who had fainted, was somewhat unceremoniously handed over to

the maids. Phineas was curtly told to "git out," and in another

moment this ordinarily drooping woman, under the transforming

inspiration of "something to nurse," had taken possession of the

whole business, and cool, alert, peremptory, and almost smiling, was

superintending the removal of the injured man to the best bedroom. Thomasina burst in with a clamorous demand that Billy should be

taken to the tollhouse, and went away injured, scandalised, and

weeping, because the man she had been so anxious to get rid of had

been appropriated by somebody else. Jeff had to listen to

recriminations against himself and the Wenyons all that night, with

the empty bed of his poor friend before his eyes, the ceaseless

clamour of his wife's tongue in his ears, and nothing to relieve the

situation.

Under Mrs Wenyon's prompt directions, Billy was conveyed to the

chamber upstairs, the fact that he was unconscious, if not dead,

being tearfully whispered by one scurrying attendant to another. Phineas, venturing part way up the stairs, was peremptorily ordered

down again by his now masterful wife, and the doctor arriving at

that moment and meeting him as he came down, assailed him with a

string of opprobrious epithets very characteristic of the man, but

terribly distressing to the already conscience-smitten and

brow-beaten Phineas. The new landlord, simpleminded and tender as a

child, had conceived the idea that he was responsible for the

dreadful catastrophe, and was, in fact, a sort of murderer. The

master painter had suggested that the signboard should be put up

again into its place in the small hours of the morning when there

was nobody about; but Phineas, who was constitutionally impetuous,

was so anxious to see his name blazoned up as the first of a new and

reforming race of inn-keepers, and so impatient to give an admiring

public an example of his poetic genius, that he would not wait an

hour after the board had come.

And now, where was he? He had, by his

stupid impatience and stubbornness, lamed, perhaps even killed, a

fellow-creature, and all for ungodly vanity and mere childish

self-conceit! It was a dreadful thought; and the cooper, with his

hands deep in his pockets, his head sunk into his shoulders, and his

brain awhirl, slunk guiltily out of the back door of the inn,

ashamed to show his face to his neighbours, and agitated with all

sorts of painful apprehensions. As all the people were discussing

the accident at the front door he had the back to himself. He paced

about with a dejected hang-dog look, he rubbed his hair, called

himself terrible names, stopped every now and then to hold his

breath and listen, and expected every moment to hear the dreadful

tidings that the poor stranger was no more. His recent great triumph

and the amazing popularity it had brought him seemed a hideous

nightmare, and the extensive hotel and its out-buildings became

hateful, eye-blistering sights. Up and down and in and out, first in

one direction and then in another, he paced, until the silent walls

seemed to be accusing him, and the innocent pigeons were cooing

jeering accusations. Presently he heard the bawling voice of the

doctor and the clattering of hoofs as he rode away. Phineas heaved a

great sigh of relief, for the sufferer was evidently not

dead. Then he caught the sound of a cart coming up the arched

passage into the yard, and with sudden shame glanced here and there

for a place to hide; and finding nothing quite secure enough, he

turned tail and skulked indoors.

Avoiding the kitchen, from which came the sounds of many feminine

voices all speaking in undertones that were louder than their

natural ones, he wandered into the deserted bar-parlour, stood

staring for a few moments at the reproachful-looking polished

pewter, turned restlessly about once or twice, and then returned

aimlessly into the passage. There was one room he suddenly

remembered which was sure to be quiet enough, the left-hand room at

the front which was kept as a retiring and reserve room; and to this

he made his doleful way. At another time it would have struck him as

being singular that the door was not quite closed; but thinking of

infinitely sadder things, he pushed the door before him, lounged

moodily forward, and then drew up with a start and a stammering

apology. The room was occupied. There in the far corner, her head

buried in her hands and her face hidden in a handkerchief, sat a

woman. Phineas turned tail and was retiring; but the stranger,

raising her head, made a short exclamation, and before he could

escape, had him by the arm.

"Oh, Wenyon, he's not dead! Oh, say he's not dead! Oh, what shall I

do! what shall I do!"

"He's not dead! Oh, say he's not dead!"

It was Clara Crouch. The moment she heard of the accident her

instinct had told her that there was help in it, though she could

not all at once discern the connection between this occurrence and

her great desire. She knew little of her brother's clerk—had, in

fact, greatly opposed the engagement of this or any other assistant; but now it seemed like Providence—Clara, in fact, like

others not a whit better called it so—his connection with her

brother, would give her entry to the inn and an opportunity of

conversation with one or other of the inmates. Well, that was

something—much, in fact, if she knew herself, and—yes! oh, yes!

Billy was a valuable servant. The accident meant serious loss to

Simpson, and the Wenyons were sensitive, what she called "silly,"

people, who would be greatly distressed at what had happened and

very anxious to make any sort of atonement possible. Clara, with

rising spirits and quickened wits, made her way to the inn; and had

she known how exactly the innkeeper was being prepared for her

visit, the misguided woman would have made another little

encouraging note to herself as to the evident favour and manifest

help of "Providence." The servants scarcely noticed her, were too

flurried to attend to a mere caller, and so she had been put into

this reserve room and—and forgotten. That Phineas himself should be

the first to enter was a matter for congratulation.

"Oh, beg pard—no, no! I didn't know! No, no, woman, he's not dead!"

"Oh, poor fellow! Poor, poor fellow! What shall we do? What

shall we do?" and Clara, hiding her face in her hands again, but

keeping her faculties alert, waited for opportunities, and rocked

herself about like one demented. The cooper scarcely knew Billy at

all, but did dimly remember that Simpson had been reported to have

engaged a clerk. Why, then, this accident had injured them also; and Phineas had expatiated too often on the far-reaching effects of sin

at temperance meetings not to realise that here was another terrible

fruit of his vain folly.

"Why—why—I didn't know. I—I couldn't—No, no, he's not dead, woman!

He isn't, for sure!" and the conscience-smitten cooper stammered

helplessly, scarcely knowing what he was saying.

"But he will, he will! And what shall I do? Oh, what shall I do?"

But Phineas had all a simple but conceited person's pride of

sharpness and insight into character; and as Clara seemed even to

him to be rather overdoing her part, he cried protestingly—

"Why, woman! Clara Crouch, he's nothin' to you!"

The question underlying his protest was the last thought in Clara's

head, but seeing the advantage of it, she caught at it eagerly.

"Oh, don't! Don't, Wenyon! Nobody knows, and—and he's Simpson's

book-keeper."

Phineas, though still incredulous, stared at her with an

ever-increasing sense of misery; and Clara, realising her advantage,

wrung her hands and moaned—

"Poor fellow! Dear, dear fellow! Oh, whatever shall I do?"

The overwhelmed innkeeper, covered with shame and confusion, uttered

a prolonged groan; and, moving towards the sobbing woman, began

patting her soothingly on the shoulder, and promising compensation,

help, atonement, anything and everything he could think of, to give

her consolation. Then he enlarged on the splendour of poor Billy's

act and the lifelong obligation under which he had placed both him

and his family. He assured her again and again of his deep regret

and his entire repentance of the stubborn pride which bad been the

immediate cause of the accident. And Clara listened and refused to

be comforted. Then he blundered out some sort of apology for the

injury he had done to her private feelings, and made rash assurances

as to what he would do to requite her for the unintended wrong. And

Clara sighed and sighed and begged him whatever happened not to

betray her to the "unfeeling world." Finally, the astute damsel left

the King's Arms carrying a pressing invitation to Simpson to visit

his once prospective father-in-law as soon as possible, and an open

invitation to herself to visit the inn and see the patient at any

hour of the day. With this and a repeated assurance that he would

not breathe the tender secret she had betrayed to him to a soul,

Clara, not at all disappointed with the result of her visit,

hastened away.

But the first news the troubled landlord heard after Clara Crouch

left him effectually extinguished what little hope that clever woman

had raised within him. The injured man was not expected to

recover—to live, in fact, many hours and had Clara known it, Phineas

would just then have relinquished the public-house and all the proud

schemes his brain had conceived to anyone who could have guaranteed

the recovery of the suffering outcast and the return of himself and

his family to the once despised monotony of their simple life at the

cooperage. Phineas felt doubly guilty: he had brought trouble,

anxiety, and shame on wife and daughter, and blood-guiltiness—yes,

no other word would do—upon his own soul. And all for a mere stupid

fad, a weak and wicked whim! Conscience-smitten and utterly

hopeless, he felt that all the reproachful proverbs his wife could

accumulate upon him would be too feeble to do justice to his

transgression; and realising that, he felt somehow a sudden, strong

desire to see and listen to her. Twice he ventured with that thought

in his mind into the kitchen, and twice he slunk back again in

disappointment. Then, sitting in the lonely parlour and brooding, he

heard her voice, and stole into the passage to listen. She was

giving orders, and giving them with a quiet self-possession that

surprised him. He peeped round the door corner; she looked serious

enough, that was true, but there was a curious change in her. Her

meek eyes positively shone with purposeful determination, and there

was a set about her mouth that greatly puzzled him. She was issuing

her orders with quite unwonted celerity and firmness, and seemed to

see and think of everything. A casual reference to the just

departed doctor brought a curious half-smile upon her lips, and in a

moment she was quoting the proverb about the physician who kills

to-day to prevent you dying to-morrow. Presently she caught sight

of him, and, delivering another string of crisp commands as she

went, followed him into the parlour.

"He called t' poor lad a swilling sot," she cried indignantly, as

she closed the door and set her back against it.

"Well?"

"And a walking whisky-tub!"

"Well? Go on!"

"And he swore at me dreadful and declared he'd never get better i'

this wold."

As she spoke, Mrs Wenyon was the picture of offended dignity, and

looked for all the world as though the professional verdict was a

personal insult.

Phineas groaned at the news; but his now excited wife demanded—

"Will Providence let him die after doing that splendid thing?"

And Phineas, to whom the question came unexpectedly, flushed with

sudden emotion, and clenching his teeth to keep back starting tears,

clenching he cried—

"Never! never!"

"Die?" cried she, giving full vent to her outraged resentment,

"we'll show him! He shan't kill him! He can't kill him! Why, man,

the cook can beat the doctor any day, and we'll save him to spite

him," and fairly on her mettle now to defend her one pride of life,

her skill in nursing, Mrs Wenyon, more excited than her husband had

ever seen her, and with a confidence purposely exaggerated to infect

and cheer her miserable spouse, hurried off to her all-important and

delightful duties.

But before that sultry summer's night was over the good nurse had

need of all her courage and confidence. Her indignation had been

aroused first of all by the fact that the hardhearted medico had

strapped the patient down to the bed; but in the weary watches of

that exacting night she thanked God again and again for those bonds. Fits of delirium and fits of half-conscious wildness succeeded each

other with bewildering rapidity. The patient raved and shouted, and

spouted poetry one minute and the next was kissing the hand that

adjusted his slight bed-covering, sobbing like a whipped child, and

crying out in pleading tones, and with haggard, beseeching eyes, for

drink. As the slow, humid hours wore by and her strength was

exhausted, the light of hope grew dimmer and dimmer within her; for

she realised but too well that such excitements would have drained

the strength of even a strong person, and this poor, drink-cursed

fellow had not an ounce to spare. After daybreak the patient lapsed

into comatose helplessness, and his despairing watchers could

scarcely tell sometimes whether he was alive or dead. The doctor,

who came earlier than usual in spite of his pretended contempt for

the case, went about his work with surly growls and odd, half-spoken

mutterings about "fools i' petticoats, mad women," and the like; and

then told Mrs Wenyon with quite unusual gravity that the patient

would not last the day.

"His leg—Woman? Measly foot! That's nothing! He's no more vitality

than a bootjack! His body's starved, long starved, much starved, and

poisoned by the confounded drink! That fellow's had D.T.'s as oft as

you've had tic. Why, woman, he hasn't the strength of a measly

mouse!"

There was heavy depression and much lamentation at the King's Arms

that day; and late in the afternoon Dolly, who was not told the

desperate condition of the patient, was posted off to the toll-house

in search of additional help. There was only one person her mother

could trust, and they had been expecting Thomasina to call about the

patient she so very much wanted to have all day. But as neither she

nor her husband had been near, Dolly had started out to seek them.

CHAPTER XIII

THE OFFENDED TWIGGS

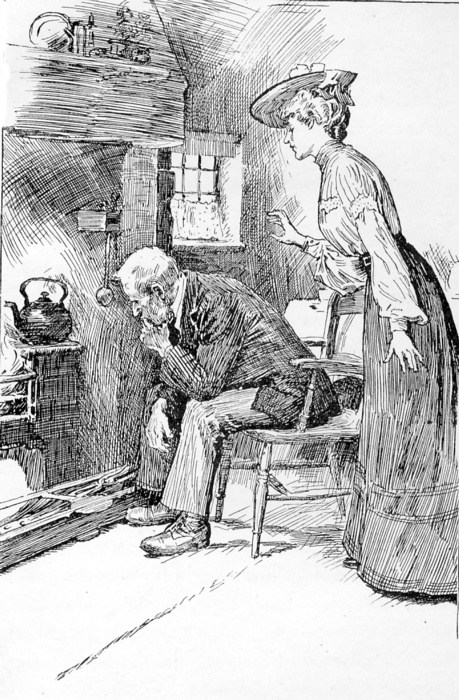

WHEN she started

on her errand to the tollhouse, our young heroine was, of course, in

an excited though strangely softened condition. Tramp,

ticket-of-leave man, drunkard, or what else, the poor wretch lying

in the best bedroom had saved her life; and she was so young and

romantic, and the whole incident was so very like the charming

occurrences in those sweet stories she delighted so much in, that he

had come all at once to be a gallant hero in her eyes; the mystery

about him, his fantastic manners, his bravery, and his present

precarious condition, appealed strongly to her unsophisticated and

susceptible nature, and as she went along the road many a fervent

little prayer went up to heaven that the jeopardised life might be

spared.

A small basket containing a few new-laid eggs and a cream cheese was

swung on her round, dimpled arm, and she was eagerly anticipating

that 'Siná would be only too ready to come and assist them once

more. She had known the Twiggs all her life; 'Siná had been

present at her birth and helped to nurse her through all her

infantile disorders. As a child, she had assisted all

unconsciously in bringing the prolonged and precarious courtship of

the bill-sticker to its present happy consummation, and had ever

since been the most honoured of all guests at the tollhouse.

Jeff had carried her many a long mile on his shoulders, and was, in

fact, her chief male friend and confidant, until the interloping

Simpson came along. Jeffrey had sulked for a whole month and

pretended to be offended for a much longer period when she began

courting, and Dolly had always attributed his dislike of the

bobbin-maker to jealousy, real or pretended. Her visits to the

Twiggs were generally frolicsome little holidays for the old couple;

but this afternoon, with many strange thoughts and much foreboding,

she approached the little cottage very soberly. The weather

being hot and close, the door was open, and she caught sight of Jeff

sitting in the corner with his elbow on his knee and his doleful

face propped upon his big hand. He was evidently in the dumps,

and she wondered—not for the first time—why neither the old man nor

his wife had been at the inn that day. At the sound of her

footsteps the moody bill-sticker turned his head to look at her and

immediately sat bolt upright and stared before him: there was no

delighted grin of welcome as of old, and he neither moved nor spoke

as she stepped over the threshold.

"She caught sight of Jeff sitting in the corner, his

doleful face propped

upon his big hand."

"Good afternoon, Jeffrey—er—a—where's 'Siná?"

The mistress of the house was in the little scullery; but as

Dolly spoke, the door was snappishly banged and there was a noisy

rattling amongst the dinner-pots.

"Jeff! Jeff cried Dolly, glancing distressfully from the

stony bill-sticker to the sullen door, "what's to do? Wh—what's

all this?"

Stiff as a statue, Jeff rolled his eyes round to the little

window at his left elbow, whilst his eyes blinked rapidly and his

face grew longer; but he did not speak.

"Jeff, what is—'Siná?—Oh—" and then, with sudden

recollection, "Oh, no! no! he's not dead. I've come straight

from home, and he's not dead!"

The scullery door opened, and Thomasina, with face of flint,

brought a few still smoking plates to the little corner cupboard.

"'Siná, tell me—you must tell me—what is the matter?"

But as the amazed Dolly put out her hand, 'Siná evaded it

with an indignant little jerk of her pudgy body; and Jeff, still

glowering through the side window, emitted several highly

significant sniffs. Dolly stood in the midst of the floor and

glanced helplessly from one mysterious and evidently offended friend

to the other in wonder and distress.

"We haven't robbed nobody o' nothin'," and 'Siná,

banging the cupboard door, stalked stubbornly back to the scullery.

Jeff, with face all a-work, sniffed again and again and

nipped his little red eyes together in vain attempt to stifle his

poignant self-pity.

"Friends, both of you, oh, don't make me worse than I am!"

and there were tears in the poor girl's voice that set Jeff off

crying without disguise.

But from behind the half-open scullery door came a deep,

sepulchral "Thou shalt not steal!"

Dolly, dumfounded at this unlooked-for and utterly

inexplicable salute, paused perplexedly a moment, and then,

springing at Jeff as the more vulnerable of the pair, gave him a

petulant little shake and cried piteously—

"Oh, do say something! Oh, what is to do?"

A snuffling attempt at self-recovery; a long, undecided

"m–f–ph–m," and Jeffrey was commencing some reply, when there was a

sound behind them, and Mrs Twigg, red as a turkey-cock, but on the

verge of mortified weeping, stood hands on hips before her visitor

and demanded—

"Did you pick him out o' t' deep road gutter? Did you

nuss him an' coax him an' give him your vary own crust out of your

mouth? Did you set up wi' him an' bring him to? Did you

doctor him an' convart his soul an' mend his breeches an' sign him

teetotal?

With a blank, breathless look Dolly stared at the outraged

little tempest amazedly; but before she could speak or Jeff could

finish his long, half-endorsing, half-deprecatory groan, 'Siná had

resumed—

"We found him, didn't we? an' findin's keepin', isn't it?

I hadn't niver a bairn o' my own, an' God sent me him. Our

Jeff hadn't no cross and couldn't show his mettle. It's

robbery! It's nothin' else!" and poor 'Siná dropped into a

chair and began to rock herself to relieve her struggling emotions.

"The Lord gave, the Lord taketh away," sighed Jeff with

reluctant resignation.

And then Dolly understood. She knew this old couple

through and through, and, though the idea in their minds was to her

a ridiculous distortion of truth, she knew how intensely real it was

to them, and began gently and cautiously to make explanations and

apologies; and in a few moments, helped by their deep affection for

her, the three were as friendly as ever. But she had need of

all her tact and all their regard for her, for the old folk were in

deadly earnest, and nothing but the invitation to share in the

nursing of the invalid would ever have reconciled 'Siná.

Presently, when they were on safer grounds, Dolly asked—

"But, 'Siná, I thought he was—you said he was a trouble to

you?"

"Ay, like enough; women 'ull say owt but their prayers.

Trouble, lass! It's a fine sight more trouble to be 'bowt

[without] him."

"But I thought he was a drunken tramp and—and not quite

right?"

"Right, bless you? Why, woman, he's more sense nor a

book, and when he gets in his tantrums wi' his Scriptur and his

gibberitch he talks like a Lord Bishop!"

"She means his potry," explained Jeff with the condescending

blandness of superior knowledge.

"But what is he like when he's sober?"

"Bud he niver is," replied 'Siná, secretly delighting in the

wonder of their guest; and then she qualified it by a musing,

reluctant "hardlings ever."

"But he's nothing to you! Why should you trouble?

He ought to go to the poorhouse or the asylum."

"He never will!" snapped 'Siná with sudden, fierce defiance.

"Not while we have a roof and a crust," added Jeff almost as

angrily.

"But why not? What is he to you?" and Dolly, though

bold, realised that she was treading on very thin ice. "It

isn't as though he were your—"

"He's our own bairn, our luv, our angel," broke in 'Siná in a

voice that began in hot indignation and broke suddenly into tears;

and before she could finish, Jeff had jumped to her side, and,

towering over the scared Dolly, was demanding fiercely—

"Didn't the Lord send him? Hasn't He given him to us?

Doesn't it say a 'man shall be a hidin' place,' and doesn't it say

'restore sitch an one' and 'lift hup the hans that hang down,' an'

'cover a multichude o' sins' seventy times seven? Well, then,

why not!"

And as Dolly listened with eyes that shone until they

glistened with tears, she looked from one enthusiastic old face to

the other. 'Siná, proud of the impression they were making,

and most evidently anxious to deepen it, touched their visitor on

the arm, and pointing to Jeff's chair, cried—

"See, yo, woman! If you was sittin' up o' that there

chair an' he came in wi'out his tantrums, an' he came an' sat down

in that rocker just like that, an' started o' talkin' to you, you'd

luv him!" And as the blushing girl was breaking out into

protestations, 'Siná added with profoundest conviction, "You could

no more help it nor you could fly. He's beautiful!"

But at this moment the little hanging clock gave warning in

tones that seemed impossible from so frail a structure, and Dolly,

with exclamations of alarm, began to exhort Thomasina to get ready.

That good woman, though leisurely enough as a rule, began to bustle

about in great haste, but was distressed to find twenty little jobs

that could on no account be left. Being a woman, 'Siná had

always most to do when she had least time.

Usually there was no need of circumspection in conversation

with these old friends, but there was a certain shyness and

hesitation in the questions Dolly asked, and even her frequent

exhortations to 'Siná to make haste generally ended in another

query. They had picked Billy out of the hedge-bottom, the very

spot being shown; they had nursed him back to something as near to

health as seemed possible to him; they had so entered into his

pitiable condition and necessities that they loved him before they

knew it, and since then had almost worn themselves out in patient,

quixotic, but, in Dolly's eyes, very beautiful efforts to reclaim

him. Who he really was they knew no more than she did, but

that he was no common tramp they were very sure. He had

"quality ways," "fine grammery talk," was as "gentle as a lamb," and

always "most piteously grateful," but in the presence of drink he

became both fool and madman; would do anything, say anything, risk

anything, to gratify a craving that had long since become his

master.

When, with the liberty of old friendship, Dolly asked whether

this very undesirable lodger paid them anything, Jeff put on a

stupid, doggèd look and appeared not to hear, whilst 'Siná, gave a

monosyllabic answer which would have deceived a stranger, and

noisily changed the subject.

When the bustling and chattering Thomasina was at last ready

and Dolly rose to depart, Jeff turned his face away and was secretly

contorting it into all kinds of dubious shapes through the little

side window; but presently he turned abruptly, put his two great

hands on Dolly's shoulders, and looking down into her fresh, young

face, with solemn earnestness he said—

"You're my own lassie, my own dear girlie, aren't you?"

"Yes, Jeff, but why—?"

"An' you'll take care on him, won't you?"

"Yes, oh yes! Mother and I and 'Siná will pull him

through, you'll see."

"Yes, but t' other, lass; his body's nothin'— his soul!

You'll keep the drink from him?"

"Of course; there'll be none at the King's Arms, and he'll be

weeks yet before—"

"That's it, woman! Hay, it's the Lord's doin's, an' its

marvellious in our eyes. He's done this o' purposs! He's

done it to save him! And we will save him, all on us,

and you'll help?"

"But what are we when he gets abroad again with his great

besetment?"

And removing his hands and pointing a dusty finger upwards,

Jeff cried with shining eyes and quavering voice—

"'He chooseth the weak things of the world to confound the

things that are mighty.' You'll help us, and we'll all help

him, and—and we'll save him yet."

And Dolly, full of the memory of the drunkard's dread

necessity, and full also of a hundred tender, womanly emotions she

could not have explained, quietly put her hand into Jeff's, and

nodded a consent she could not speak, and then turned and hurried

away after Thomasina. |