|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER V

UNDER HEAVY FIRE

IT is an odd

thing about good and trustful thing women that they are often

unaccountably nervous about the moral resources of their husbands

and sons, and get seriously alarmed when their beloved ones are

unexpectedly exposed to even ordinary temptations. And it was

so with good Mrs Wenyon. She knew that her husband was a

sincere Christian, though in her view somewhat worldly; she knew

that he was proud—sinfully proud, she feared—of his position as

deacon of Salem. During all the years of their married life

his temperance principles had never been once shaken, in spite of

many and serious temptations, arising from the fact that his

business brought him into contact with, and in fact made him largely

dependent upon, brewers. She knew that in her mild way she had

great influence over him, and that he valued her opinion on

important matters, however much he might scoff in trifling things.

And yet, as soon as she understood the full significance of the

temptation to which he was now exposed, her heart sank within her,

and she became the prey of most painful apprehensions. She was

one of those gentle, pensive creatures who always take their

pleasures a little fearfully, see remote possibilities of evil in

the happiest occurrences, and are never really hopeful except when

all their friends are in despair. She loved and trusted her

husband, but she had small faith in poor human nature, especially

when it took the masculine form, and knew, and knew exactly, how

strong and trying this great temptation would be to her husband.

And Dolly secretly shared her mother's fears; only, as she

played a peculiar part in the relationships of the family, and was

compelled to say and do things sadly at variance something with her

real feelings, she met her mother's apprehensions with light banter

and inextinguishable optimism, and always "stood up" for her father.

To her father, however, she was generally, as he phrased it, "a

little parson in petticoats."

But this grave crisis now upon them, touching as it did the

deepest and dearest things in life, threw them all back upon

themselves, and the two women were afraid to confide in each other,

lest each should find in the mind of the other the very fears she

was fighting in her own. Before her parents, therefore, Dolly

affected to treat the thing as a huge joke, not to be seriously

considered for a moment; but it scared her to discover that her

father, after appearing for days to enjoy her banter, began to show

restiveness under it, whilst her mother grew more pensive and silent

every hour, finding her only consolation in the quotation of her

favourite proverbs.

The two women did not know of Simpson's visit, and for his

own reasons Phineas said not a word about it; but next morning the

cooper showed signs of broken rest, was surly and absent-minded, and

presently slipped out a word that brought stricken cries from both

of them.

"Drat it, woman," and he turned snappishly towards his wife,

but avoided her eyes, "you talk as if t' job were settled; can't you

wait a bit and give me time to think?"

They both understood what he meant by "the job," and poor Mrs

Wenyon dropped her eyes and moaned, "Where there's smoke there's

fire."

"Mother, I'm surprised at you! It's only one of his

tricks! He's as much likely to become a publican as I am to

become a—a—a stuffed turkey."

The incongruous comparison tickled and mollified the cooper,

and as he departed to the workshop he chucked his wife under her

white double chin, and cried—

"There! there, woman! it isn't a hanging job, anyway."

From that moment, however, they both watched him with an

ever-growing anxiety, and both felt that even his hesitation was

discreditable. They noted that he had a feverish fit of

industry upon him, and stuck to the shop from early morn to late at

night. They knew that he had been to Benderton to see his

uncle's lawyer; he had been seen twice in consultation with the

agent of the brewer who usually supplied the King's Arms, and

finally they learned that he had been shown round the inn.

Lady visitors, chapel officers, temperance workers called upon them

and besought them to use their influence with the cooper; and Miss

Agatha Jacques, a particularly strong-minded lady, informed poor

tearful Mrs Wenyon that God and conscience were before even husband,

and that they were all looking to her to make a stand, if even she

had to separate from the "deserter."

The last word stung Dolly, who was present.

"Miss Agatha," she cried impetuously, "we hate the very

thought of that nasty place; we would die rather than go; but father

is father, and a dear good man, and—and where he goes we go."

Then they found that a few of the Salem faithfuls, lifelong

friends of the cooper's, had been holding prayer meetings that their

"poor weak brother" might be saved from the snare of the tempter.

Most unfortunately the minister was away on his summer holidays, but

two long letters came from him, the second of which Phineas did not

show them. The cooper, meanwhile, was growing, moodier and

sulkier every day; he was losing his appetite also, forgetting the

day of his most important chapel meetings, and carefully avoiding

his teetotal friends. "Mother" was growing visibly thinner

under Dolly's eyes, and the poor girl wished that she had even her

banished lover to comfort her.

"Blake tells me that 'The Arms' is worth four thousand pound

if it is worth a penny."

This was Phineas's first direct reference to the anxious

subject for days, and was made at the breakfast-table. Both

women dropped their heads, and the cooper had to try again.

"There's many a better man nor me been a landlord."

It seemed as if there was to be no reply, but at last Mrs

Wenyon answered almost under her breath—

"Two blacks don't make a white, Phiny."

"Old Swidge of the Griffin at Spattleshaw is a better saint

nor many a big professor."

"One swallow doesn't make a summer, Phiny."

"Well, woman, are fortunes picked up in t' street? It's

flyin' i' th' face o' Providence!"

"'Ill got will soon rot.' 'Better is a little with the

fear of the Lord than great treasure and trouble therewith.'"

The cooper, worsted in his word battle, gave a grunt and a

resentful jerk of the head; and as Dolly got up at that moment to

attend to a caller, husband and wife were alone. Phineas sat

stiffly in his chair, and as the silence became more and more

uncomfortable he stole a glance at his wife. Presently he felt

a soft touch on his hand; it seemed to burn him, and he turned his

head away. The gentle hand stole up his sleeve, over his

shoulder, round his neck.

"Phineas, have we allus been—been cumfortable?"

"Ay, what else?" and the cooper's voice had suddenly become

husky.

"And wouldn't I give me life to—to serve thee?"

Phineas was staring before him, obstinately trying to pull

his neck away, and choke back his rising emotion.

"If thou loves me, Phineas, if thou loves me nobbut a bit,

oh, my lad, my lad! spare me this."

And Phineas rose up suddenly, pushed her almost rudely away

from him, and tore out to his work. He returned though, twice

that morning, without any particular reason, and talked heedlessly

to Dolly, whilst he slyly watched his wife from out of the corner of

his eye; and when he came in to dinner Dolly perceived a puzzling

change in him. He seemed to have recovered his spirits, and

was quite himself again. No, not quite, for though jaunty

bunglingly witty, as his wont was, he was obviously not at his ease;

his laugh was more than a little forced, and his hilarity was broken

by curious little fits of absent-mindedness. The mood lasted

all that day and the next. Dolly augured all good things from

it, but her mother was very mistrustful and steadily refused to be

comforted. He was hardening himself, she feared, trying to

carry the thing off with a jest. Towards evening, however, he

changed again, and—oh, worse than ever!—became affectionate and

propitiatory. How utterly staggered therefore was Dolly, and

how amply justified her mother's fears, when late that night he

announced that he had decided to take the public-house; and how

amazed and scandalised were they when he supplemented the

announcement with a rough, coarse guffaw.

CHAPTER VI

A COMICAL CUPID

NOW Simpson

Crouch though taller, was not as heavy as Dolly's father, and of

course he was much younger; but when he staggered into the dark and

silent street on the night of his interview with the cooper, all

thought of resistance, all indignation and anger, were swallowed up

in paralysing, stupefying amazement. The action of the cooper

was so utterly inexplicable, and so entirely different from all his

expectations, that poor Simpson had been ignominiously ejected and

was alone in the street before he could realise what was happening.

What could he have said or done? He was succeeding so well,

Phineas had seemed so thoroughly interested, that victory seemed

certain; and all at once, like the transformation scene of a play,

this had occurred. He pulled himself together and glanced

sheepishly up and down the road to see if his degradation had been

observed; he clenched his fist and shook it at the closed door of

the cooperage with muttered curses, and then, standing there in the

stillness, be looked round and tried to realise what had happened,

and why.

The more he reflected, the more confusing and hopeless seemed

the puzzle, and when, at last, he began to move away, the double

indignity he had just suffered was awaking raging fires within him.

And Simpson let them burn: burn themselves out if they would; for

whatever else he was or was not, nobody could accuse him of ever

allowing his dignity to interfere with his practical interests.

Something had offended the fool of a cooper, that was evident, and

he would have given much to find out what it was. At the same

time, there was a great deal at stake in this matter, and if there

was anything to gain by swallowing his humiliation it must be done,

dignity or no dignity; but if there was nothing to gain—well, then,

revenge and just resentment might have their fling. And by

this it will be seen that Simpson was a philosopher—of a sort.

But if he could not decide why the all but convinced cooper had so

suddenly changed his mind, neither could he find in what had taken

place any reliable hint of what his prospective father-in-law

intended with regard to the King's Arms.

Once embarked on this aspect of the case, personal

considerations were, for the moment, forgotten; he never dreamed of

the possibility of there being an end to his courtship, and, having

now in prospect two strings to his bow, the bobbin factory and the

King's Arms, he clung to these with relentless tenacity and made

them the means of forgetting the humiliations he had suffered.

The financial value of Dolly's charms, and the numbers of amorous

customers who might be attracted to the inn by so dainty a landlady,

were far more practical considerations than any amount of mere

vulgar revenge, and no one could put his pride in his pocket more

easily than he upon sufficient inducement. All the same, when

be had carried his point and got himself securely installed in the

hostel, Phineas Wenyon might look out, and his independent daughter

too, for that matter.

His sister had retired when he reached home, for he took a

long detour to get himself cooled down; but over his frugal supper

he took the matter up again. Yes, having failed with the

father—what on earth had riled the old fool?—he must turn his

attention once more to the daughter; and the alternative was

unexpectedly distasteful to him. All his attempts to get on

terms with her again had so far failed; his letters had not even

been acknowledged, and though he usually met her often enough in

going about the town, some perverse fate had lately kept them apart.

After what had occurred—and the remembrance of his ignominious

ejection certainly was hard to forget—he could not simply go to the

house and ask Dolly's parents to intercede for him; still Dolly,

impulsive and even proud maybe, had always been easy to manage

before, and this was only a passing freak, and now that he had so

much at stake it would be a simple thing to take all the blame and

plead for her unqualified forgiveness. It was a new thing

certainly to have to consider his ways with her; but knowing what he

knew, no foolish scruples must stop him. He got very little

sleep, for that humiliating ejection would insist on coming back

again, and consequently he was not in the very best of humours when

he sat down to breakfast, and it was nearly nine o'clock when he

turned into the yard of the little bobbin-mill.

His office was a little tumble-down one-story structure, just

inside the gate, with a narrow high-countered room as you entered,

and an inner office where all the work was done. A wooden

partition divided the two, and as Simpson quietly opened the outer

door, as his manner was, he pricked up his ears at the sound of

voices, or, to be exact, a high-pitched voice, declaiming in

sternest tones some literary extract. Simpson frowned

contemptuously, and, pulling up, bent his head to listen. The

tones were harsh and grating, and there was marked indistinctness of

articulation, but the speaker was evidently in great earnest.

"Yes, William, Immortal, Encyclopedic William, thou hast said

it—

''Tis true, 'tis pity; and pity 'tis 'tis true.'

"'Oh, that men should put an enemy in their mouths to steal

away their brains; that we should with joy, pleasance, revel and

applause, transform ourselves into beasts.' Beasts, William?

Swine, sir! crawling, guzzling, grovelling beasts! Here they

are, sir, large as life. Beasts, sir! the guzzling—"

"'Oh, that men should put an enemy in their mouth

to steal away their brains'"

But here there was an abrupt stop, for Simpson had opened the

door and was looking in with undisguised contempt. And there

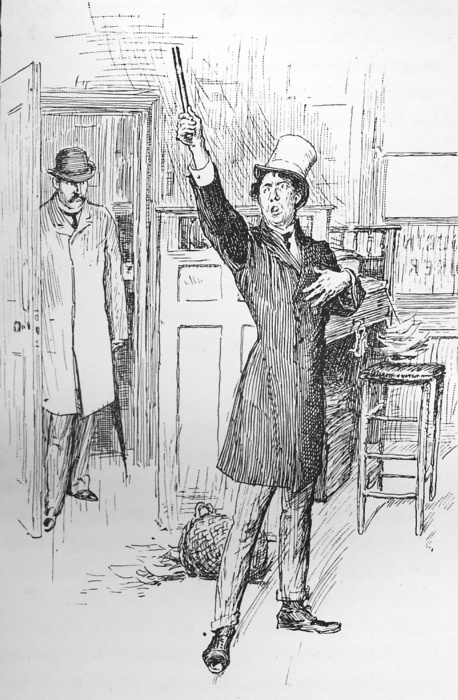

was something to look at certainly. Prosaic little Snelsby had

not had in it for many a day a more fantastic object than that upon

which the bobbin-maker now gazed.

The figure was that of a man, tall, painfully thin, yet very

well proportioned; but the garments were those of a scarecrow. A

dingy white, battered top-hat, stuck on the head at a perilous

angle; a weather-faded green-black frock-coat, much too small for

the wearer; a dirty red sporting waistcoat, with the nap for the

most part rubbed away, and a great clumsily made tuck under the

lapel of the coat to reduce the vest to wearable dimensions.

There were also a pair of faded grey trousers turned up at the

bottom, and boots so down at heel that the toes tilted up like the

nose of an empty river-steamer. The collar round the neck was

frayed and dirty, and the scarf which held it together was blue silk

in the exposed part and grey cotton garter under the collar-folds.

The face, in spite of its absurd puckers of tragic expression, was

refined and intellectual, but the nose was red, the skin blotchy,

and the striking brown eyes weak-looking and watery. This was

Billy Stiff, the bobbin-maker's recently engaged half-price clerk,

who had been in this employ for about-three days. He was not

modern enough to drop the ruler with which he was assisting his

elocutionary efforts, but stood there overtaken and abashed—a

ridiculous serio-comic figure.

Simpson unfortunately was somewhat devoid of humour at any

time, but this morning everything irritated him, and so, eyeing his

servant with surly disgust, he cried—

"You were drinking again last night?"

"Drink, sir? No, sir! I was drunk—drunk as a

fool, drunk as an ass! Ass?—I beg pardon, my long-eared

friend"—this with a grandiose, apologetic gesture—"I was drunk as a

pig!" and, pulling up suddenly, be banged the ruler on the desk,

stared hard at his scowling master for a moment, and then whisking

round and presenting his rear, he waved his ragged coattails and

cried, "Your look says, kick, sir! By all means, the very

thing, sir! Oblige me with a kick, sir!"

Simpson turned away with a weary sneer, and then, as he began

to open his correspondence, he remarked icily—

"Drink, you fool, if you like; but once come drunk to work

and you'll have a kick out."

Billy, for that was the clerk's name, took off his absurd

hat, bowed obsequiously almost to the ground, stuck the shapeless

head-covering on a peg, took up a pen and opened a ledger, and in a

few moments was working at express rate, muttering as the shaky pen

travelled over the paper a medley of Shakesperian quotations which

Simpson neither recognised nor heeded.

Proceeding with his correspondence, Simpson for once seemed

disappointed with its purely business nature; then he sat down and

stared vacantly through the dirty window, went out into the works,

but, returning almost immediately, sat down to his letters again,

and in a short time he was propping his chin on his hands and

peering through the dirty panes.

Usually Simpson could not work fast enough, and was

incessantly and not too civilly stimulating to the excitable Billy;

but today the poor clerk had peace, and his employer was up and down

and in and out every few minutes. Towards the middle of the

afternoon, however, he seemed to revive, and gave some attention to

his affairs; but just as Billy was going out, for what he

superfluously called "tea," Simpson called him back.

"Billy, would you like to earn—er—a—a— sixpence?"

Billy removed his hat with a grand flourish, as though the

sum named had been in banknotes, and protested that even the modest

threepenny-piece was not beneath his consideration. But just

as he was plunging into quotation, Simpson asked—

"Do you know Sticky Lane?"

Billy was of the opinion that all Snelsby lanes were sticky,

except when they were dusty; but Simpson, who was obviously

impatient, interrupted—

"It's the lane that runs down the back of High Street, on the

further side from here. Do you know Miss Dolly Wenyon?"

"Woman! lovely woman!

|

"'They are the ground, the books, the

academies

From whence doth spring the true Promethean fire.

They—" |

"Oh, shut up! She's the cooper's daughter; their house

is the third from the bottom, and you'll know it by the fancy

pigeon-cote near the back door."

Billy was looking prodigies of comprehensive acuteness, but

did not speak.

"I want you to go there and watch for her; she's young—about

twenty—and will, I daresay, have a light frock on."

The clerk was nodding and his lips were moving, as he

muttered to himself some choice quotation he dare not utter.

"I'll take you and show you where you can stand and be out o'

sight. You are to watch till she comes into the garden; there

is a summer-house facing the lane, and if you are smart you will be

able to see right into it. If she goes in there and sits down

or begins pottering and gardening, whip round to me instanter; I

want speech with her badly. But if she seems to be likely to

go indoors, stop her at once and give her this note."

Billy was scowling and twisting his face to impress these

details upon his mind, and as he took the note and was about to

speak, his master added—

"And look you, Billy, let me get speech with her, or only get

this note safely into her hands, and I'll make it a shilling, and

you can get as drunk as you like."

An odd spasm, as though some sore spot had been touched in

the poor wreck's soul, passed over his features, but Simpson,

absorbed in his own affairs, noted nothing.

"I can't skulk about there looking like a fool, so just look

slippy, man—and, mind you! let the drink alone until you've done

your job, and you may drink your fill."

About six o'clock, therefore, Billy might have been seen

dodging under the hedge on one side of narrow Sticky Lane some yards

behind his master, who had strictly forbidden him to come nearer.

A minute later he was securely hidden in the deep hedge of the

cooper's garden at the point indicated by Simpson, who was now

strolling idly down the lane, trying hard to look as though he had

no interest in anything near him.

Unfortunately the little recess in which Billy found himself

did not give him the advantage he required; the hedge was higher and

thicker just there, and a clothes-post stood right in his line of

vision for the summer-house. He had not dared to point this

out to his master, so he spent some time in seeking a more

favourable point and thinning out the twigs thereabouts, so that

presently he had a fairly convenient outlook. Then he stepped

hurriedly into the middle of the lane, glanced hastily up and down

to make sure his master was not secretly watching him, took another

somewhat absent-minded survey of the garden, and then, stooping so

that his head was not visible over the hedge-top, scurried up the

lane, darted into the back-yard of the Red Lion, and returned almost

immediately, surreptitiously wiping his lips. It was dull work

standing there and peering through a hedge at the time of year when

its foliage is thickest, and Billy was not of a patient nature.

Presently his muddled brain began to work in its favourite

direction, and, smiting his chest with stagey vehemence, he cried

under his breath—

"'Oh, what a fall was there, my countrymen!'

A go-between! Troilus become a Pandarus! Adonis a

messenger and fetch-and-carry for Hodge and Molly!"

Scowling fiercely in tragic self-contempt, he shook his fist

at the aperture he had made in the fence, wiped his mouth, glanced

longingly towards the Red Lion, and was just subsiding into

indistinct quotation, when his manner changed and a sudden

admonitory "Ah!" escaped him. In a moment his red nose was

buried in the thick hedge and he was staring with raised brows and

bulging eyes at some object in the garden. Then he drew back,

gave a soft prolonged "P–h–e-w," and jammed his face into the

foliage again.

"William," he gasped, "great William, she's a beauty!"—and

then, after another amazed exclamation—

|

"'Oh, sweet Juliet, thy beauty hath made me

effeminate '"— |

Billy took another long, wondering look around, as though calling

all nature to behold this entrancing vision; then he thrust his face

into the hedge again, and springing back in sudden horrified

revulsion, he dropped into a melodramatic whisper and cried

incredulously, "He!—and a goddess? Pluto and Proserpina?

Beauty and the beast?" and with a face the picture of sudden

loathing he dug his heel-less boots into the soft soil and took

another peep.

Dolly, clad in simple summer drapery, had come out into the

garden, more by force of habit than anything else, and was now

wandering aimlessly about the moss-grown paths with a cloudy,

brooding face. She was evidently avoiding the summer-house,

and keeping herself from the more exposed places, but her manner was

pensive and absent, a fact which the absorbed watcher did not fail

to note.

"'The lily tincture of her face!'"

and poor Billy sighed prodigiously. Dolly wandered a little

nearer, and the excited watcher was feasting his eyes and marvelling

more and more.

|

"'Ah! ah!

She something stained with grief, that's beauty's

canker"'; |

and Billy scowled until his face looked hideous, and fiercely shook

his fist in the direction in which his master had left him.

Dolly, unconscious of the eyes that were devouring her, stood

there with drooping head just long enough for Billy to take his fill

of her fresh and simple beauty, and then, turning her back to him,

wandered toward the garden-house. Billy dragged his fantastic

hat from his head, squeezed it recklessly between his knees, pushed

his head deeper into the thorny fence, heedless of scratches, and

followed her keenly with his eyes. Her beautiful hair, her

soft willowy figure, and the neat little hands she clasped behind

her, appealed powerfully to Billy's susceptible soul, and he sighed

heavily as she moved away. Suddenly he remembered his

instructions and fixed his watery eyes on the summer-house.

But his thoughts were evidently otherwhere, and in a vain endeavour

to fix his muddled mind on the amazing, confounding fact before it,

he whispered to the hedges—

"He, the soulless, money-grubbing bobbin-man! He—

|

'may seize

On the white wonder of dear Juliet's hand,

And steal immortal blessings from her lips!'" |

Then he took another, a long indignant look, at the

unconscious maiden. She was leaning absently against the

pillar that supported the roof of the summer-house, and gazing with

cloudy face at a clump of snap-dragons. As he watched her the

thought grew great within him that he was playing an unworthy part;

he was a spy, a spy for pay, for mere drink! Of Simpson Crouch

he was evidently prepared to believe the worst; of the pretty Dolly

it were treason to think ill; and in a few moments the mercurial

clerk had gone over heart and soul to the maiden's side. Here

was Beauty in distress; here was a lonely maid being dragged by a

scheming villain, and perhaps by stern, greedy parents, into hateful

marriage; or here was a tyrannical and jealous lover taking cruel

advantage of his position and privileges; and the soft-hearted,

muddle-brained watcher ground his teeth and spitefully thrust his

red nose against the thorns. "Ah! Billy felt a cold

chill run down his back, and his heart grew suddenly hot: the girl

he was watching had lifted her hand and brushed something from her

cheek.

"A tear! Oh, not a tear!" and a moment later, Billy,

forgetful of his errand and even Shakespere, was staring with

swimming eyes through the branches and weeping in copious sympathy

with the sorrowful maiden, his mouth all a-work with feeling, and

his frail body shaking with vicarious emotion, whilst great beads of

tears were rolling down his cheeks and standing in blebs on his nose

and chin.

He gnawed at his lips, clenched his hands, thrust his heels

deeper into the earth, and looked again. She had sunk back

into the shelter, and dropped disconsolately into a seat, her face

covered with her hands, and soft sobs shaking her frame.

"William! William!" and the agitated, sobbing drunkard shook

his fist vehemently in the direction of the bobbin-shop.

But his outstretched arm stopped suddenly in mid-air, a scowl

of almost demoniac craftiness wrinkled his grotesque face, he patted

his moist and ruddy nose with his forefinger, and bestowed a wink of

prodigious cunning upon the nearest tree. Then he dropped on

his hands and knees, crawled along the hedge-bottom until he found a

likely place, and then, with a final peep to make sure the

distressed damsel was still there, he began crawling upon his

stomach and insinuating himself through the fence into the garden.

Dolly, whose thoughts, sad though they were, were miles away

from Simpson Crouch, still sat in the shelter, allowing the soft

tears to drop through her small fingers. Her father's

announced intention of taking the King's Arms had so amazed and

distressed her, and her mother's pitiable sorrow was so harrowing to

behold, that hope and comfort seemed suddenly to have left her life,

and a sense of humiliation and horror at the thought of standing in

a bar had taken entire possession of her. To whatsoever point

she turned, there was the same dreary, hopeless blackness, and

though she had thought until her brain ached, she could think of

neither likely way out nor friend to fall back upon.

"Ah—hem!"

Dolly raised her head with a startled exclamation.

"'Weep not, sweet Queen, for trickling tears

are vain.'"

With a terrified little scream the amazed Dolly sprang to her

feet and then fell back, gasping with fright, whilst the

preposterous Billy, looking seedier and more ridiculous than ever,

stood there with bared head and hand on heart, genuflecting like a

French shopwalker.

His outrageous sartorial get-up, his blooming nose, the tears

not yet dried on his cheeks, and the fatuously reassuring smirk with

which he beamed upon her, would, but for the startling suddenness of

his appearance, have tickled Dolly's fancy, but as it was she shrank

away in genuine fright, and cried, "Oh—oh! Go away! What

do you want?" and she pushed her hands outward and averted her

scared face.

Billy majestically swept the floor with the crown of his hat,

fell with a drunken lurch upon his knees, clasped his hands

together, and cried,—

"Afraid? A garden goddess, a queen of flowers afraid!

'Tis Billy! thy slave Billy, love's meekest messenger!"

"Go away! Oh, I shall scream!"

"Scream? Am I a monster? a frightful goblin of the

night?

'The Russian bear, the Hyrcan tiger?'

Ah, lady,

|

'I'm like the toad, ugly and venomous,

Which wears a precious jewel in his—er—a—hand,'' |

and with another dramatic flourish he pulled the letter out of his

pocket, gallantly kissed it back and front, and with many an

overdone bow presented it to the shrinking girl.

Dolly was not a nervous person, and so, in spite of natural

alarm at the advent of so suspicious and grotesque a stranger,

amusement and curiosity were getting the better of her fears, and,

reassured by the sight of Simpson's well-known yellowish envelope,

she asked more confidently—

"Who are you? What do you want?"

"Who am I?"—and Dolly noted that, fantastic and tramp-like

though be was, his accent was refined—"I am love's poor pilgrim.

I am—ah, verily!"—this with sudden inspiration—"I am Mercury the

messenger; I am Cupid himself!"

Bowing, ogling, covering his dingy red waistcoat with

expanded palm, and scraping his right foot at every word, the doubly

intoxicated Billy was superb; and glints of fun shot up into Dolly's

still wondering eyes; whilst a half-fearful smile began to play

about her little mouth. She had forgotten the letter; this

grotesque and ridiculous figure was vastly more interesting, even

though he did smell of beer.

"Are you?—did you—did Simpson send you?"

Another long series of obsequious bows.

"Who?—where?—do you—do you work for him?"

"Your servant's servant is your servant, madam," and the

messenger made another unsteady attempt at posturing, and smote

heavily on his chest.

In our complicated natures there is a consciousness

underneath our consciousness, and Dolly's prevailing mood at this

time was pensive. Something, therefore, in his last gestures

struck her oddly and touched a tender chord. She glanced at

him again: his emaciated look, his worn, sunken eyes, the

poverty-stricken details of his costume, all heightened in some odd

way by the ridiculousness of his manner and appearance, moved her

unexpectedly; she looked until her eyes grew misty, and, hastily

feeling in her Pocket, she held out a little silver coin and

murmured softly—

"My poor, poor fellow!"

And Billy returned her look with sudden stupidity, his whole

frame gave a quiver of emotion, he reached out for the coin, and

then sprang hastily back, whilst his face was all a-work with

agitation, and the next instant he had cleared the summer-house and

was staggering down the garden-path.

Before she could collect her thoughts, however, he was back

again.

"Goddess divine! Angel of pity sweet!" and his face was

wet with maudlin tears. "Command me! enslave me! b–b–b–ind me

in chains, for I am thine," and then, as she rose and gently laid

her band on his threadbare sleeve, he stepped back, eyed the place

she had touched with glowing looks, and then, raising his hand in

dramatic warning, he cried, "Beware of bobbins! Beware of the

heart of wood!" and with a snort, a snuffle, a hasty whisk round,

and a flying sob, he was gone.

And as Dolly sank wonderingly back into the shed, the anxious

self-pity with which she had first entered it melted into soft,

womanly sympathy, and the feelings that went out so tenderly to the

poor muddled drunkard brought gentle relief to her own breast, and

she lingered there in the fading light, forgetting utterly the

letter in curiosity and pity for the messenger, and sad wondering at

this strange, queer world.

CHAPTER VII

PHINEAS AT HIS WORST

MEANWHILE the

cooper's little household was divided and distracted about the

terrible impending, removal to the King's Arms. Mother and

daughter were filled with dumb, helpless incredulity that paralysed

thought. That a family of teetotalers should belie their

convictions and the professions of a lifetime and become sellers of

liquor was simply unthinkable, and Dolly at any-rate refused to

believe that the thing would ever come about. Mrs Wenyon was

the prey of most painful misgivings; without ever having heard that

"every man has his price," she had such mistrust in human nature,

that she feared almost any human being could be overcome if only the

temptation were strong enough. She believed her husband to be

sincere both in his religion and his teetotalism, but she knew that

he did not like coopering, that he had strong business instincts

which would paint to him the financial advantages of this tempting

affair in rosiest colours, and that he was very susceptible to

temptation on the side of his pet hobbies. To her, therefore,

it seemed only too possible that the inducement might be too strong

for him. It was hard to think so ill of him, but masculine

human nature was very, very weak.

And the cooper's own conduct strengthened her apprehensions.

He either was or pretended to be most unusually busy; he

systematically avoided her, never gave her the opportunity of coming

to close quarters with him; and if they were accidentally thrown

together, he made all the haste possible, "couldn't be bothered just

now," and got away as quickly as he could. At meal-times and

on other occasions when they must meet he put on a jaunty,

rollicking air, seemed in most uncommonly good spirits, and indulged

in rough witticisms and boisterous but plainly forced laughter.

Every now and again, as his eye caught hers, he would burst into

unexpected and altogether inexplicable guffaws, as though the sight

of her suggested some secret but irresistible bit of fun; and the

more she sighed and moaned, the more flippant and demonstrative did

he become. That there was desperate defiance in his ill-timed

jocularity, defiance of her, of public opinion, of the voice of the

church and of his own conscience, she did not doubt for a moment;

and knowing his natural obstinacy, she was praying that somebody

would reason with him one moment, and dreading the provocative

effects of "badgering" the next. If Dolly refused to despair

and spoke hopefully, she chided her as young and thoughtless; and if

she gave the slightest indication of fear and was inclined to

censure her father, the dear, distracted soul valiantly took up

cudgels for her lord, and was fruitful of excuses and even

justifications.

The two anxious women noted that the deputations from the

chapel and the Temperance Society ceased, that the cooper was being

left severely to himself, and that they were all looked coldly upon

by old friends wherever they went. But when at last it was

realised that Phineas was spending much of his time going to and

from the hated public-house, and that preparations for the actual

removal were already commenced, desolation came down upon them, and

they gave themselves up to weary, useless lamentation.

"But, mother, are we nothing? Are we nobody? Are

we to be dragged into this shame without a word?" And Dolly,

though exceedingly indignant, was also very miserable.

"'Honour an' obey,' lassie, 'for better or for worse,' 'till

death us do part,"' moaned the sobbing wife.

"But I'm not married to him! I'm not—"

"'Honour thy father an' thy mother,'" came struggling out of

the crumpled apron.

"But he does not honour us! He degrades us, defiles us;

he would drag us—oh, mother, fancy Dolly Wenyon serving beer to

ogling, leering boobies in a tap-room! I would die first!"

Mrs Wenyon was gazing at her daughter with weary,

pain-strained eyes that slowly filled with tears again. Then

she dropped her head, and with drooping, pathetic mouth she sighed—

"Dying? Wot's dyin'! I'd die and be glad if I

could save him, b–b–bless him!"

It was only thus and now that Dolly realised how little hope

of effective resistance there was in her mother; but just as she was

preparing some fresh argument, Mrs Wenyon raised her eyes, and,

clapping her hands, cried in tearful exultation—

"Oh, thank the Lord! That's it! Oh, bless the

Lord above!"

"Mother, whatever is the matter?"

"Oh, Dolly, my dearie, dearie, you are saved!"

"Saved?"

"Yes, saved! Oh, blessed God—yes, saved! Why,

girlie, you can get married!" and in her eager delight with her own

idea the poor soul put out her arms to catch at her daughter's gown.

"But, mother, he—he's not asked me, and—and we've

quarrelled."

"Quarrelled? Tut, tut, girl, what's a lovers' tiff!

'Lovers' quarrels quicken love.' Make it up forthwith, woman;

it's thy salvation!"

Dolly, feeling inwardly the stabs of prudential

self-reproach, gravely shook her head.

"Yes, girl, it's the very thing! It's Providence's gate

of gold, a blessed way of escape. 'Lovers' quarrels are love

redoubled.' Why, bless us, thy father got me out of a

quarrel!"

Dolly's head was still shaking.

"Tut, woman! Leave it to me. I've twenty pound

upstairs, and I'll give him a hint to hurry—"

"Mother!"

"Tut! Will you spoil your life for a tiff? It's

Providence!—a blessed, blessed Providence!"

Dolly was wavering; she knew by this time that she had no

great love for Simpson Crouch, but she had a sensitive woman's

proneness to self-accusation. Their courtship had given her

lover certain rights, and it might be she was injuring him.

She had also much of her mother's simple, unlimited faith in the

Divine Providence, and it really did look as though this was not

merely a possible way out, but the one provided by the higher

powers. She had not an overweening faith in her mother's

judgment, but she had unbounded confidence in her religious

instincts, and the certainty with which Mrs Wenyon expressed herself

greatly impressed her. That she could bring her lover to her

feet again by a word or even by a look she did not doubt; that she

could get on fairly well with him when she must she also believed;

and that the experiment would please her mother and bring hope to a

shame-stricken, breaking heart seemed clear; but all the time

something within her was almost choking her with protestations.

She was a woman, with perhaps more than her share of a woman's

delight in self-sacrifice; it was something great to do, something

beautiful, one little sacrifice as an acknowledgment of her mother's

uncounted self-surrenders, and surely that was easy to do—and right.

Slowly she raised her brooding eyes and looked waveringly

into the other's painfully anxious face, and all at once a rush of

uncontrollable emotion swept over her; prudence, self-interest,

everything else was borne away before the impetuous rush of her

feelings; she flung her soft arms round her mother, pressed a hot,

wet cheek to another hot, wet cheek, and cried in broken accents

"No! no! no! There's plenty of lovers, but only one

mother. 'Where thou goest I will go; where thou lodgest I will

lodge; thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.'"

Mrs Wenyon, as much overcome as her daughter, sat still and

allowed the outburst to spend itself, and before Dolly had recovered

she had concocted a guileless little plan of her own, and presently

proceeded to carry it out. She would soothe her daughter, put

her off the scent by a little talk, and then contrive an interview

with Simpson, which she felt confident would put everything right.

But the questions she presently asked were not very

encouragingly answered. Dolly was very decided, saw no chance,

and seemed to have no desire for reconciliation, and the poor mother

got the suspicion that perhaps the separation had been of Simpson's

own seeking, and that therefore Dolly could not re-open the subject.

The good soul thought very slowly, hugged to her heart as one of

life's most precious remembrances the sweet words her daughter had

uttered, and only came back by intermittent efforts to the plan she

had decided upon. Yes, she would act at once; Simpson would be

only too glad. Dolly could have almost any young fellow of

their rank in the town. She was too innocent, too good-natured

to have made a quarrel without a cause. Simpson might require

a little management, but he could not have really changed his mind.

He was rather too worldly, perhaps—all men were, to her—but he knew

how to look after his own interests, and the legacy, hateful though

it was—Oh, no! no! That is it! that is it—and the simple

schemer, sitting alone and musing over her little plan, stared

before her with wide, wondering eyes. Of course! Of

course! Oh, why had she not thought of that before!

Simpson was ashamed of them, and had broken the courtship off

purposely!

But just as the distressed soul reached this point, she heard

her husband calling her, and hastened downstairs with a

fast-fluttering heart. Phineas was seated stiffly in his

chair, and Dolly, white-faced and tremulous, leaned against an open

cupboard door. In a few moments the two were informed that two

days hence they would take formal possession of the ale-house.

Phineas spoke with quiet firmness, as though anticipating and

rejecting beforehand all remonstrances; but their opportunity had

come, and there was too much at stake to neglect it. They

objected, they protested, they appealed to his self-respect, his

temperance, his religion; they offered to work with their own hands

and keep him if he wished, to find him money for his hobbies, to

suffer any privation, any sorrow, rather than be dragged down to

this. Observing that he listened with most unwonted patience,

they took courage, and first hinted and then roundly declared that

they would never, never darken the doors of the King's Arms; and at

this the utterly abandoned wretch simply laughed. They talked

of his kindness, his indulgence as father and husband; they reminded

him of the sweet, quiet days of the past and the shadowless sunshine

of their hitherto happy lives; and Phineas shuffled uneasily in his

chair and presently hung his head. They appealed to his pride

in his home, his delight in his only child, the money he had spent

on her education, and the respect in which they were held in the

town. They recalled his ancestry and connections, his brother

the missionary and his sainted father; and when, with a low grunt,

he hastily brushed away a tear, they literally fell upon him, old

arms and young being twined round his neck, old lips and young

pressed to his burning cheek, and then—and then, oh! miracle of

hardness!—he suddenly flung them both from him, sprang to his feet,

and rushed away, crying as he banged the door—

"I've said I'd take it, an' I'll take it."

There was neither hope nor love in the faces of those two

when, an hour afterwards, he came back; and, oddly enough, this time

it was Phineas who had to expostulate.

Were they to throw three thousand pounds into the gutter?

Weren't there good publicans as well as bad? Did they think

that the old skinflint who had gone was going to best him?

Weren't hotels absolute necessities in business and social life, and

wasn't it a grand opportunity to show people how such places should

be conducted? Why, it was a call, it was a mission! He

could purify and reform a dishonoured but necessary calling, and

thus do more good than his teetotal advocacy had ever done.

But the women had exhausted themselves, and though every word he

uttered cut like a knife into them, there was no reply; and so

finally, with an aggrieved air, he went off to bed without taking

his invariable evening pipe.

The awful day came at last. Phineas was up by break of

day, and he seemed to have so successfully hardened himself that he

appeared to be positively enjoying himself. When Dolly and her

mother came upon the scene, he plunged at them in a clumsy,

shamefaced fashion, and insisted on kissing them, and then, standing

away and surveying them, though with averted eyes, he burst into a

great roar and bustled off to hurry up the men. Over the

breakfast, with a brutality that utterly amazed them, he called Mrs

Wenyon "landlady" and Dolly "barmaid" he declared the former was

born for the job, and that Dolly would make the fortune of any

decent bar. He showed them a letter from a brewery firm

offering £3250 for the inn, and requesting that he would receive

their representative, who was empowered to make extraordinary terms

if he would consent to "tie" the house. All morning he bustled

in and out, full of quips and cranks; and whenever he came upon

either of them, he looked keenly into the leaden face, burst into a

loud, coarse guffaw, and hastened away.

Mrs Wenyon became more than distressed, and very soon even

the bitter thought of where they would sleep that night was

forgotten in more serious concern for her husband. He was

another man, an infinitely harder and coarser man. Was he

already in drink? Had be broken his almost lifelong pledge so

soon? If it was not drink, he was certainly going mad, and her

dull, heavy grief and gathering shame were lost sight of in alarmed

anxiety.

The inn was not many yards away, but one of the first things

they learned that morning was that one of the King's Arms carriages

was coming to take them to their new abode. They both

protested; they both wept. They insisted that if they were to

go, they would go the back way as quietly as possible, and after

dark.

But Phineas did not even listen to them, and when the time

came he burst in upon them in a violent hurry, hustled them out of

the dear old home and up to the carriage door. When they drew

back at the sight of the gaudy equipage, he almost tumbled them

inside, and, skipping in after them, with a jaunty flourish he

defiantly waved his hand to a little knot of scandalised chapel-folk

who were looking sadly on. Holding down their heads for very

shame, the two humiliated and heart-broken women were borne rowdily

away; but as they drew up in front of the hostel a fit of reckless

bravery came upon Dolly, and, stung by the ridiculousness of the

spectacle they were making, she tossed up her head and boldly looked

round. The painters were engaged upon the outside of the

building, but Dolly noted that they had a surly, resentful look

about them. A man with a cart was driving away as they drew

up, and loudly denouncing the new landlord for something she could

not catch. Two loafers were coming out of the inn door as they

approached, and both looked indignant and disgusted. Why,

everybody, even the degraded drinkers themselves, were crying shame

upon them. "Lord help us!" groaned Mrs Wenyon, with a sigh

that went to her daughter's soul.

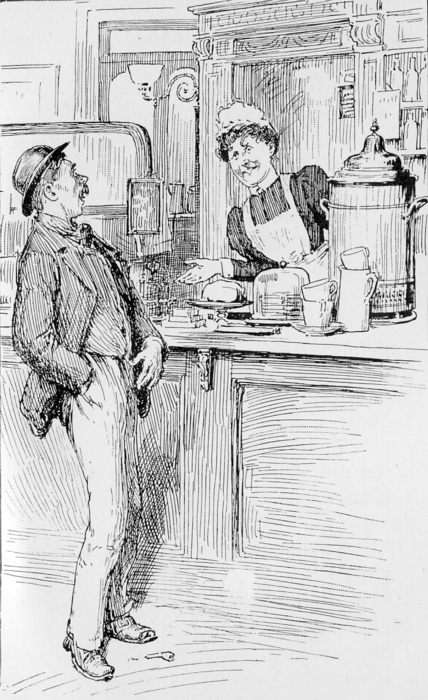

"Now then, come on! Isn't it grand? Shan't we be

comfortable? You'll live for ever here, old lady, and Doll 'ull

get more blooming—What? What did you say?" The last

sentence was addressed to a man who had entered the porch behind

them.

"A four o' whisky—warm."

"Jane, gi' this man some whisky," and Phineas roared out the

order as though there was some secret and delightful honour in it.

Jane stood and grinned. "Now then, mestur!—we'll give

him a pie!"

"Pie?" cried the customer in supreme contempt.

"Ay, pie! There's more good in it nor i' whisky, and

thou'll get no whisky here," cried Jane with the same placid grin.

"Thou'll get no whisky here," cried Jane with the

same placid grin."

"No, neither now nor never; they'll be nothin' intoxicatin'

sold here," cried the cooper.

The two women had only faintly attended to the altercation

thus far, but the last words aroused them, and as the man turned

away with a curse, Dolly, in wide-eyed wonder, turned to her father

and demanded amazedly—

"Father, what does it all mean?"

"Mean? Old skinflint left me this public, didn't he?"

"Well?"

"On condition that I lived in it, didn't he?"

"Well?"

"But there wur no condition about selling drink, was there?"

Two breathlessly overwhelmed women gazed at the grinning

cooper for a moment, and then the impetuous Dolly flung her arms

round his neck, and, in spite of grinning lookers-on, began kissing

and blessing him as though she would never cease. Mrs Wenyon

stood there looking dumfoundedly around; but in the first pause that

came to Dolly's hysterical salutations, there was a soft, reverent,

trembling sentence from the new "landlady"—

|

"'The b—b—bud may have a bitter taste,

But sweet will be the flower,'" |

CHAPTER VIII

SIMPSON SHOWS HIS HORNS

NEVER in the

whole course of her short life had Dolly Wenyon been so

inexpressibly, so overpoweringly happy as she was when the full

significance of her father's grand coup dawned upon her; it was so

sudden, so utterly unexpected, and yet so funny, and to her innocent

mind so wonderfully clever, that her whole nature exulted in it, and

the rebound from extreme depression to proud, exultant triumph was

so great as to be almost painful.

But her healthy young nature soon came to her relief, and in

a few moments she was dispelling her long-pent and shameful

anxieties in the wildest possible way. With a sobbing laugh

she sprang at and hysterically hugged her father, smothered her

mother's inevitable proverbs about not whistling until you are out

of the wood under a shower of kisses, caught that solid dame round

the waist, as though to make her dance, and, finding the task beyond

her powers, spun round the substantial form in a whirl. She

dragged her mother from room to room with incessant exclamations of

delighted surprise at the many contrivances and conveniences to be

found therein.

Whenever she encountered her father in any of the many narrow

passages, she fell upon him with a hug, till that good man, with

rumpled hair and necktie all awry, rescued his cap from the sanded

floor and declared with beaming face beaming that she had gone

"clean daft." She raced upstairs, whirled through the rooms,

skipped down again, to drag the protesting new landlady after her to

inspect the sleeping accommodation. She called her father

"Landlord," "Boldface," "Mine host," and even "Mr Bung." She

scrambled madly up to the attics and plunged into the cellars.

She patted the two astonished maids on the shoulder, and looked as

though she could have eaten them. She gave a grumbling and

disappointed farm-labourer a whole shilling as compensation for the

absence of "fourpenny," and terrified poor Jake the ostler by

pouncing upon him from behind, and, mistaking him for her father,

drawing his head back for a kiss, and then flinging him away with a

little scream of embarrassment and shame. At the

tea-table—another of the cooper's crafty surprises—she gaily usurped

her mother's position, gravely apologised for the absence of "brown"

cream, badgered her father about the difference between "noggins"

and "halfquarterns," pressed the unwonted dainties upon her parents

with excited volubility, absently helped herself to this and that

tasty bit, until her plate was a bewildering mixture of viands, of

which after all she scarcely tasted; and when at length poor

"mother" gently remonstrated, she rushed off into another string of

delighted exclamations, and, finally breaking down with a

treacherous catch in her voice, she burst into a flood of happy,

grateful tears.

She was quiet for some little time after this relieving

breakdown, but even then her feelings found vent in caressing little

strokes of her father's sleeve and affectionate little pats on her

mother's soft hand; whilst the smiles she bestowed on the maids made

them blush with pleasure, and the poor ostler received what he

described privately as "another floorer" by being addressed as

"dear." The meal, though she took so little of it, did Dolly

good; and though she was calmer and more self-possessed after it,

the joy within seemed to grow deeper every moment.

Dolly was happy—happier than she ever remembered to have been

in her life; her cup was full to overflowing, and she must do

something, and something adequate to the occasion. She was

making herself ridiculous, she told herself, but there was no help

for it. Her heart was swelling; she could not contain herself

for gratitude to God, her father, and the whole smiling, friendly

world. Yes, she must do something!—something kind, something

generous, something really great and handsome; she was happy, and

others—ah! poor, poor Simpson! The bobbin-maker would have had

a perfectly new sensation if he could have peeped into that little

back sitting-room and seen right down into the swelling heart of his

hitherto obdurate and irreconcilable sweetheart. Dolly was

crying—crying for the pure joy of her last happy thought. Yes,

that was the very thing; that only would properly represent what she

felt. She would forgive Simpson; she would love him as of old,

only more, much more. Forgive him? She would ask him to

forgive her!

The sunshine broke again through the pitiful tears; yes,

Simpson should be forgiven and reinstated. There was something

deep down in her heart which was protesting strangely —well, let it!

She was glad of it! It would make the effort greater and the

sacrifice more real.

Simpson should be restored, handsomely restored, and that

very night. She would go further even than that. He

often visited them as her father's friend at the old cooperage, but

she had never brought him formally into the house as her future

husband—perhaps the poor fellow had felt that. Well, she would

make ample amends; he should come that very night, should have the

daintiest supper the King's Arms could provide, and should be as

happy as she was herself.

Too excited to sit, she paced about the room, clasping her

hands together, and laughing and crying and crying and laughing at

the fairy pictures in her mind. They seemed so beautiful, so

appropriate to her state of mind, that she could not resist them,

could not reason about them, could not even wait until Simpson

should be at liberty.

Stealing out of the inn the back way, she scurried up the

lane, in at the old cooperage garden door, and up to her own old

bedroom to dress—for even in this delighted ecstasy she could not

forget her clothes. Any dress had been good enough for that

reluctant and shameful expedition to the King's Arms, but now she

must look her very, very best. Her Sunday clothes? No,

but a judicious selection. There was a hat that did justice to

her hair, and a blouse that was a little less prophetic than the

others of embonpoint, a gown that helped her complexion,

and—oh, yes—a sweet little brooch that Simpson had helped her to

select. (That prudent young man had never bought her anything

more expensive than chocolates.) She began her toilet in

nervous, fluttering haste, but the finishing touches were added with

absentminded, dubious deliberation. At first she could not

dress fast enough; at last she was ready too soon.

She lingered at the glass a strange long time for a person in

a hurry; her complexion had never been so bad, or her hat so

unmanageable. She thought more and more about sending a little

note, but she had previously decided that that would not do; she

must go to the mill, go even to his very home and encounter that

terrible sister of his, if need be, to make adequate amends.

She was impatient to be off, and yet she lingered. She smiled

to think of Simpson's surprise and joy, and yet she had to put her

hand upon her heart to quell its turbulent beatings. Oh, yes,

God had been good! So good! It must be done, and done

handsomely. And so at last she started on her journey with a

plunge, pulled up at the shop door with a palpitating heart that

nearly choked her, turned half round in frightened postponement, and

then rushed into the street with sudden, desperate decision, her

heart thumping into her ears, her face changing colour every moment,

and her limbs trembling under her.

It was a mad thing, a bold, most improper thing, Dolly told

herself as she hastened on, to visit a young man at his place of

business; but whilst her mind went back to the security of her

little room and the handy notepaper she might have used, her feet

went forward, and in a few moments she stood at the bobbin-maker's

office door. She did not expect to find it ajar, and when she

did so she cast a startled glance around and started to flee.

Her leaden feet, however, refused to move, and lifting a hasty

little sigh she knocked timidly on the panel. The silence that

followed was providential, and there was still time to escape, but

she could not move, and presently mustered courage to tap again.

Could anything more clearly indicate the will of the higher powers

than this? But still she lingered, and at last, with a shaking

hand, she ventured to touch the door and gently push it inward.

Still nothing happened. Why, the outer office was empty, there

was nobody about! Ah, yes! Peeping shyly in, she could

just see the elbow of a sleeve and part of an arm and shoulder; it

was Simpson himself, but he had not heard.

Then an idea struck her; another timid glance around, and she

pushed the door softly before her and stepped on tiptoes into the

outer apartment. Pausing to balance herself and get her

breath, she could hear nothing but the scratch, scratch of Simpson's

pen. A nervous teasing fit, the refuge of fear rather than the

prompting of fun, was upon her; she peeped round the corner of the

inner door, paused a moment, drew a long breath, and then

whispered—quite loudly she thought—"Simmy!"

Scratch, scratch went the heedless pen. Simpson had not

heard.

"Simmy!"

But still the relentless writing tool scraped on its way.

"Simmy! Oh, Simmy!" and dropping her painful play she

stepped into the doorway, every limb of her body trembling, and her

face red with hot, desperate blushes.

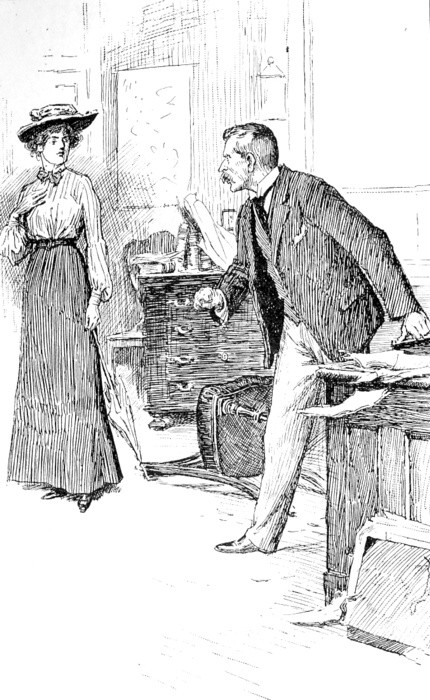

With a nervous jump and a startled cry, Simpson sprang round

and faced her, his chair tilting over and falling with a noisy bump

and his pen dropping from his limp fingers. And there they

stood for a moment; but Dolly, looking up at him with a smile

through which the tears were rising, saw his face change rapidly,

and all for the worse. There was alarm, as though he had been

caught in some nefarious act, then surprise and dawning pleasure,

and then the sudden gathering of black, fierce, wrathful

indignation, and before she could muster strength to speak he had

hissed out in blazing resentment—

"Your father's a confounded ass."

As though the stinging lash of some terrible whip had struck

her, Dolly quivered from head to foot; and as they stood there

confronting each other, neither of them heard the step and the

slightly shuffling movement in the outer office.

But there were undreamed-of depths in Dolly's innocent

nature, and the troubles through which she had recently passed, and

from which she had been so wonderfully delivered, had made her

sympathetic and generous. Her soul was burning with a sense of

insult, but Simpson had a real grievance; she had commenced this

hard task and must go through with it; and so presently she raised

her head and said in quiet, measured tones—

"Her soul was burning with a sense of insult."

"Don't blame father, Simpson; it is I, only I."

"Then the bigger fool you, that's all!"

Another pause, another long suffocating struggle in Dolly's

soul, and then came the harsh, grating demand—

"What do silly women want wi' business?"

"Business?', stammered the bewildered and outraged girl.

"It isn't business. I came to—to—to make it up."

"Did you?"

This in a tone of cold scorn that struck like a whip-lash;

but she still persisted.

"Yes, oh, yes! I've been silly, but, oh, Simpson, God

has been so good, and father so brave and strong—"

"Brave? Strong?" and, raging with a sense of

irreparable injury, he glared at her with fierce indignation and

cried impetuously, "He's an ass a blockhead! a conceited, whining,

humbugging hypocrite!"

"Simpson!"

"A swindling ranter! a canting, mouthing, fanatical idiot!

that throws three thousand pounds away and brags about it!"

"Simpson, I came to—"

"You came to cant, and whine, and lie like your father.

You are bragging about a deed that is the act of a drivelling

lunatic!"

But Dolly had come back to herself at last, and standing up

to her utmost inch, she was eyeing him with a glance that made even

this raging madman quail. Then after another long pause she

moved haughtily back, surveyed him witheringly from head to foot,

and said slowly—

"Simpson Crouch, God has been very good to me; He has saved

me from lifelong shame and made my dear father dearer than ever.

I thought I loved you once, but now I know I never—" But all

at once she stopped, struggled to speak and could not, choked back

her swelling sobs, and finally burst out, "Oh, Simpson, Simpson,

forgive me!"

There were more strange, snuffling sounds in the outer

office, but neither of them heeded.

The bobbin-man, as she took a half step towards him, and

pleadingly held out her hand, stepped sullingly, scornfully back.

"Will forgiveness bring back your fortune? Will

forgiveness save that three thousand pounds? Bring back the

property and I'll talk to you; but I'm not going to marry a fool!"

Stricken and utterly broken under the double shame of that

cruel moment, Dolly cast one last piteous glance at the raging man

before her, and then, with another burst of weeping at the thought

of her fruitless self-abasement, she turned to leave. Her head

was bowed, and her eyes half blinded with tears, but as the inner

door closed behind her she became dimly aware of the figure of a man

in the outer room, who, utterly oblivious of her presence, and with

face drawn into puckers of melodramatic rage, was wildly

gesticulating, ruler in hand, at the aperture through which she had

just come. She paused and raised her head, but he did not

heed. First the ruler, then the ink-pot, then the coal-shovel

were brandished and shaken at the door, and thick-voiced threats of

most murderous intent were hurled at it, until, in spite of herself,

Dolly was compelled to notice. All at once the performance

stopped, the extemporary weapons were thrown aside, and, springing

to the outer door, the ridiculous Billy held it open and commenced a

series of posture-master genuflexions which at any other time would

have greatly amused her. As she emerged into the yard, still

stifling her sobs, Billy snatched at the loose door-nob, swung

himself forward, hanging on the latch with one hand, and shouted in

deep, tragic tones—

|

"'Arise, black vengeance, from thy hollow

cell.

He hath out-villained villainy so far

That the rarity redeems him."' |

In her crushing, bewildering disillusionment, overwhelmed at

once with shame and indignant resentment, Dolly gave but a passing

glance to the grotesque figure as she passed on her way, but Billy

stood blinking after her and muttering quotations for a full minute

after she had disappeared. A more miserable, helpless wreck of

humanity than he looked, as he stood staring helplessly down the

yard, it would have been impossible to find, but the scene he had

witnessed through the half-opened office door had awakened a long

dead something in the poor outcast's breast, and this, blending with

all the other emotions of the moment, made him look and act like one

distracted with conflicting and mutually exclusive emotions.

In that brief space of time he wept, he laughed, he grinned like an

angry cat, he cursed; and finally he drew himself up, as though for

one pathetic moment his ruined nature had been touched with a gleam

of long-lost dignity, and with a heavy sigh and a seriousness quite

new to him lie sauntered absently back to his desk.

At this instant, however, he heard Simpson's chair move, and

all his recent excitement came rushing back. It looked for a

moment as though he were about to spring at the door and burst it

in, but his upraised arms were suddenly arrested and then flung

higher than ever, in the tragedian's most approved style of

manifesting sudden and startling surprise. His eye had fallen

on the knob of a drawer which had been left half open, and he was

staring with hypnotic intentness on a bit of light-coloured dress

material. It was obviously a fragment of the dress of the lady

who had just departed, and Billy, transfixed with mingled delight

and reverence, stared at it like one bewitched. Then he took a

long, comprehensive glance round on the silent fixtures, evidently

inviting their attention to this most marvellous bit of luck,

rubbing his hands together as he did so, and laughing in low,

delighted chuckles. He straightened out his face, strode

towards the little knob, sprang suddenly backward with alarm,

quickly relapsed into giggling, and, appropriating the small blue

morsel of material, he hugged it in his hands, into sniggering,

gleeful grimaces, and burst out—

|

"'The very train of her worst wearing

gown

Was better worth than all my father's land.'" |

If the little bit of dress-edging had been singing to him,

Billy could not have been more fascinated. He held it at

arm's-length and grinned at it; he dodged first to one corner of the

room and then to the other, still glowering at his treasure; he

scowled and glanced with sudden suspicion at the inner office door,

and then, after two or three foolish plunges this way and that, laid

the scrap of material cautiously on the desk and began to gloat over

it. At the stirring of his master's chair he swept it under

his flattened palm and hid it under the whole breadth of his

forward-bending chest. Then, as his alarm passed, he took it

out, and, reverently kissing it, talked to it in incoherent

Shakesperian snatches. Simpson came out of the office, but

Billy was too quick for him. He answered his gruff command to

close the building with an obsequious but silent bow, and then, as

the bobbin-man went his way, he took out the little shred once more

and bent over it in maudlin, doating ecstasy. Presently he

found a piece of soft tissue paper, and carefully folded his

precious prize within it. Then, as he stood in the middle of

the floor, still patting the place where his treasure lay, next his

bare skin, he suddenly remembered something, and his jaw dropped,

whilst his face turned a bilious yellow-green.

He had been so absorbed in his wonderful find that he had

forgotten to ask his master for the invariable "sub," and it was

more than his place worth to follow him home. Drink was food,

shelter, friends, life, to Billy Stiff, and in a few moments the

prospect of a night without it had reduced him to a most pitiable

condition. He stared despairingly through the window, searched

and researched his pockets for at least one remaining coin,

inspected his clothes in the vain hope that there might be some

garment with which he could dispense, though that stage had been

passed long ago; and at last, in sheer desperation, he took a

stealthy glance around in search of something not his own, which he

yet might turn into cash. Billy had had an unusually trying

day, and had all the excuses of this additional strain to reinforce

the already almost irresistible longings within him; and for the

first time in his long stagger to ruin he would have taken what did

not belong to him. Power to resist his besetment had long

since left him, but he had never yet found dishonesty any

temptation. To-night, supported by maddening desires and the

clamour of exhausted nerves, the desire had gripped him

remorselessly, and was driving his last trace of manhood before it.

Unaccustomed now to resistance, he was frightened at the very

thought of internal conflict; but in spite of himself, and the

mental trickiness he had developed in his long downward course, he

now found himself in the very throes of a most terrible struggle.

He was weakly protesting, crying, glancing furtively round on the

tempting articles of furniture and groaning in helpless self-pity,

and in a few more moments would have been a thief. But as he

stood there helpless and craven, distressed more at the fact than

the nature of the conflict, there came floating across his muddled

brain a dim and struggling picture. Fading, freshening,

clouding, brightening, dissolving and reappearing, he saw betimes a

little hut-like, wayside cottage, a spotless fireside, a patched

arm-chair, and an old man with snuffy nose and eyes nipped tightly

together, kneeling on a red bundle handkerchief together in prayer,

whilst a chubby, comfortable old woman moaned responses at the edge

of the table. "Our erring brother," "Thy poor prodigal," "This

Poor lost sheep as Thou art seeking," seemed to sound again in his

ears; and as the poor drunkard stood stiff and still, as though

listening to sweetest music, the maudlin tear began to dry on his

pallid cheek, the chest ceased its convulsive liftings, the weak,

frightened look faded, and some faint suggestion of manliness,

almost of dignity, appeared on the feeble face. And as the

vision always moving began to pass, there came just for one moment

one fleeting glimpse of an old summer-house and a soft girlish face

set therein, and Billy lifted a long, tremulous sigh. But the

next moment a rush of relaxing, traitorous self-pity swept

everything away, and he was fast subsiding into the one emotional

luxury left to him, helpless, lachrymose self-commiseration.

Billy was experiencing the wholly unexpected and emotionally

intolerable resurrection of his long-lost manhood; and every jaded

nerve of his body, and every flabby, tyrannous passion within him,

was savagely protesting. Was not his manhood dead and buried?

Had not appetite and emotion established the right to rule by long,

unquestioned possession? Why then these useless, these

terrifying pangs, added to the already more than sufficient miseries

of his life?

There was a soft knock at the door, and Billy turned with a

caught-in-the-act guiltiness, and faced Jeff Twigg, the

bill-sticker. Billy could have sprung upon him and worried him

like a mad dog. To his own surprise, however, he stood

perfectly still and waited for the visitor to speak. Ever

since the night when Jeff and his wife had picked Billy half

unconscious out of the hedge-bottom and given him a home, the

bill-sticker, thankful that at last God had sent him a burden and a

cross, had been doing his very utmost to wean his protégée

from his besetment, but without success. He had provided

tracts on every conceivable aspect of the drink question, and had

listened with hopes all too unreliable as Billy himself had read

them out in the quiet summer evenings at the tollhouse door.

He had found him the garments he wore, and taken him again and again

to the little Bethel from which he drew his own spiritual

inspiration. He had obtained for him the shamefully paid and

precarious employment he now enjoyed, and had watched him early and

late to keep him out of temptation. Discovering that Billy

kept himself right during the day, but called at the first

public-house he could reach when he left the office, Jeff had taken

the precaution to lie in wait for him and conduct him home.

After the first two nights, however, Billy had always dodged him,

leaving the works by some irregular way, once, in fact, creeping

underneath the waterwheel and wading across the river to escape

capture. But the poor wreck had things about him that had laid

strong hold on the bill-sticker's simple affections, and Jeff, in

spite of many disappointments, was more intent than ever on his

almost hopeless mission.

The man of paste eyed his charge uneasily. The

bubbling, loquacious Billy, the blubbering, tearful Billy were

familiar to him, but Billy the grumpy was a novelty.

"She's made us some oven-bottom cakes for us tea," he

remarked; and as the appetising dainty did not produce the effect

desired, he added in unctuous, coaxing tone, "Buttered."

Billy gave his shoulders a contemptuous shrug. What

were cakes, however buttered, to a man whose whole soul was on fire

for drink?

"She's bought t' County Times about that there murder,

and she's just dyin' to hear about it."

Gallant and loyal to the other sex, Billy was exceedingly

fond of old Thomasina Twigg, but at this moment he was measuring

distances with his eye, and calculating the possibilities of a

spring and a bolt. Jeff, observing nothing, went on

hesitatingly—

"She—she—we both like your readin', an'— an company."

But there was the crash of a stool against a desk, a spring,

and in another instant Billy would have escaped. As it was,

the big bill-sticker, more alert than he appeared, made a sudden