|

CHAPTER I

A LOVERS' QUARREL

"OH, dearie!

dearie! life seems hardly worth living!"

It was a dreadful sentiment for anybody in such a lovely

place and on such a perfect day, but for pretty Dolly Wenyon, the

most dainty and piquant young maiden in all Snelsby, standing, as

she did, almost up to the waist in old-fashioned flowers, with a

speckles sky above her and the air laden with summer fragrance, it

was positively shocking. A woman's moods depend on her dress,

but Dolly had on her favourite gown; and though that was simplicity

itself and fitted with trying closeness, she knew she was profiting

by the severe test. Her garden hat was big and old, but she

looked better in it than in any of her more pretentious

head-coverings, and was quite aware of the fact. She loved the

open air and the dear old garden, and was not altogether unconscious

of the fact that she became its many beauties. She was just

turned twenty-one, in perfect health, had never known a care in

life, and was going to meet her lover; why, then, this dismal

exclamation, and why, oh, why did she spoil her charms by a pout on

her red lips, and a pucker of discontent on her white brow?

Not to keep the reader waiting, that was the reason.

Though the word was not much used in the limited vocabulary of

Snelsby, Dolly was bored. A happy, contented little woman for

the most part, whose life hitherto had been a long summer's day of

even, uneventful comfort, there had come upon her quite recently a

most decided discontent. Perhaps it was her visit to

Packington and the glimpses of a larger life she had got there;

perhaps it was the delightfully exciting stories she had begun to

read of late; perhaps it was the weather, which, with all its glory,

was rather oppressive: whatever the cause, Dolly was discontented,

and the experience was so unnatural and so uncommon that she was

surprised and a little ashamed, and began to take herself severely

to task. It was silly, ungrateful, wicked, but there it was.

Her life was so humdrum, one day exactly like another and the

next like both; nothing ever happened in Snelsby, and in all her

life she could not remember anything more sensational than one or

two rather sudden deaths. "Dull?" Everything was dull:

Snelsby was dull, the people were dull, and—yes—though she bent down

her head to sniff a rose and hide her shameful blush—her lover was

dull too.

Yes, what was the use of beating about the bush?—she might as

well say it as think it: Simpson Crouch was dull, and her courtship

the dullest of all dull things.

And the worst of it was, everything was so regularly and

drearily satisfactory. Simpson indeed—yes, that was the

trouble—was too satisfactory; there was nothing to find fault about,

nothing to excuse, nothing to defend, and there was no need and no

opportunity for that heroic defence of a slandered dear one such as

she remembered to have read about in the stories, and which she

would so dearly have liked to practise herself. Courtship?

Why, there was not a single one of the delightful incidents she

recalled about "Sir Frederick and Lady Gertrude" in her story: no

stolen interviews, no delicious anxieties, no impassioned

declarations and fervent vows; her courtship had never had a thrill

in it! Proposal? She had never had anything approaching

to one! Since the time when Simpson defended her from rough

boys as she came from school across the fields, everything had been

taken for granted. She had simply grown into the thing as she

had grown into the other privileges of womanhood. Everything

had been accepted as a matter of course; she was about the only girl

in Snelsby Simpson Crouch could have married, and he was almost the

only young man who would be likely to suit her. Other girls

she knew were fascinated with the idea of being engaged, and she

felt with a wicked little thrill how delightful it would be not to

be so appropriated. There had been no passionate love-scenes

between them, no quarrels and delicious reconciliations; Simpson

kissed her now and then, of course, but just according to rule and

much as he might have done his sister. She was his property

and he hers; they acted towards each other like two old married

people, and took everything for granted.

Poor Dolly was a tender, affectionate little person, who had

just reached the most romantic time of life, and she did not know

then that "blank annals of well-being" are after all the most

satisfactory features in either personal or national life; neither

did she guess that that dull, sultry summer's eve was to be the last

hour of quiet she would know for many a long day. She had

taken her hat off by this time, and we thus get a look at her.

Her features were a little irregular and nothing to boast of; she

was a little too short perhaps for perfect proportion, and, badly

dressed, might have been unconspicuous; but her creamy skin, her

round dark eyes, her pretty dimples, and above all her mass of

wonderful dark brown hair, which at a touch from her deft fingers

would have dropped well towards her heels, gave her many advantages;

whilst that enticing air of wholesome daintiness, so suggestive of

new-mown hay or old-fashioned flowers, which was perhaps her most

distinctive and abiding characteristic, made her a very tasty,

alluring little person.

She sauntered towards the old climber-covered summer-house

and, leaning lightly against the wooden post that supported the

roof, glanced discontentedly around. The parish clock struck

seven, and as she raised her eyes and looked across at its dim face

and quaint single finger her heart misgave her. What a wicked

girl she was! She had every ordinary comfort of life, kind

parents, a lover who was at anyrate respectable and such as many a

girl of her class would have been glad to take, and yet she was

dissatisfied! She gave herself a little shake, straightened

out the pucker between her eyes, plucked an overgrown rose, and,

dropping into a seat out of the sun, began to pull it musingly to

pieces. Simpson was steady, industrious, and in his way

ambitious; he was just as much above a mere workman as she could

expect; he was kind too, though in an easy, matter-of-fact sort of

way; and if only he would not treat her quite so much as his

absolute property and their courtship as a matter of course, she—but

there was a click of the garden gate, and, though she could not see

from where she was sitting, she knew that Simpson was coming.

With manifest effort she cleared her face and moved a little,

looking the while bored and languid. Simpson did not approach.

Ah! she knew what he was doing. There was nothing of the eager

lover about him. He was looking how the cucumbers were

growing, inspecting her father's wonderful prize-bred pigs, and

estimating with shrewd business eye the crops on the heavily laden

currant and raspberry bushes. Simpson never forgot the main

thing. How could this be love?

Presently he came round the corner, looking as dull as she

felt.

He was tall and well made and bade fair to be a portly

country Englishman some day, only the lines about his eye-corners

seemed to Dolly sordid and grasping. His old straw hat was

tilted back on his head, and perspiration stood on his brow.

"Hullo, Dot!" and he lounged into the summer-house and

dropped into the cooler corner, almost without noticing her.

"You're not very punctual," she said, all her discontent

returning at his indifferent manner.

"Am I not?" and he glanced across at the church clock and

yawned.

She eyed him sideways with a dissatisfied air: he had not

even changed his working clothes, though he only came thus formally

once a week.

After a lengthy pause he remarked—

"Sarson's have got their hay in, I see."

Dolly's lip began to curl, though he did not notice it; there

was nothing to reply to, and she was getting afraid of her own

feelings.

A longer silence, broken only by his yawns; and then,

something seeming to strike him, he leaned back, crossed his legs,

clasped his hands behind his head, and really looking at her for the

first time, he said—

"Have you spoken to the old man about—er —that?"

Oh, untimeliest of questions, had he but known! It

seemed to crystallise Dolly's vague ill-humour; throat began to

swell and her eyes to blink rapidly, the colour left her cheeks and

began to tinge the lower eyelids, and she answered with severest

self-repression, "No."

Simpson, observing nothing, gave a discontented hitch to his

elevated arm and replied with surly disappointment

"But you promised you would."

"Well, I haven't—yet; why are you always bothering about

that?"

Simpson glanced at her indignantly.

"Because it's important, isn't it? It'ull make a lot of

difference, won't it?" and he seemed scandalised at her lack of

comprehension.

He was a bobbin-maker, the neighbourhood producing much

suitable wood, and the question at issue was an old tumble-down

building adjoining his yard, which belonged to her father, at least

nominally, and which he had suggested should be transferred to him

as a sort of marriage dowry he thought he could make it useful.

She stole another sidelong glance at him, choking back her

wounded pride as she did so; and then she inquired in ominously

quiet tones—

"Why is it so important?"

"Why?—Silly! What are you thinking about? Haven't

I told you it will save us expense?"

She waited to control her feelings and choke back hasty,

resentful tears. His talk was always about such things as

this.

"Will it be so very expensive—er—after we are

married?"

He could not read her: this was an entirely new mood, and his

perplexity annoyed him.

"Why, of course it will; it always is; women are dear

luxuries, I can tell you."

He would have withdrawn the last sentence, but didn't know

how; it was a new and unpleasant experience to have to pick his

words with her. She was strangely still and quiet; he could

not be sure she was even thinking. But presently it came, soft

and low and tantalisingly indifferent—

"I wouldn't burden myself like that if I were you, Simmy."

He was on his feet now; amazement and indignation in his

face.

"What on earth is the crazy thing talking about?"

"I wouldn't, lad! I wouldn't I—and there's no need, you

know."

"No need?" and he stepped back into the entrance of the bower

in breathless astonishment and gasped.

"No need at all, lad; my father'ull keep me, or—or—some other

chap."

"W–h–y! Why, hang it! Why!—did anybody

ever!—Doll, you're mad!" and then, after glaring stupidly at her for

a moment, he plumped down at her side and demanded, "Dolly, don't

you want to be married?"

She was white to the lips and trembling, but apparently

quieter than ever, as she answered with a demureness that cost her

prodigies of self-repression—

"Ay, I hope to marry some day, please God."

"But me? Marry me?"

As he waited for her reply he was preparing his. He

would have no more of this nonsense; she must understand once for

all what marrying him would mean. She was raspingly

deliberate, though he could hear the beating of her heart. She

glanced at him, and he could see she was repenting. He was

sitting on the edge of her dress, and she drew it away and sighed.

She brushed the rose-leaves from her lap, allowed her head to fall

back, closed her eyes, paused a moment, and then he heard—oh,

staggering, utterly confounding sentence!—

"I wouldn't marry thee, Simmy, if there wasn't another man in

the world."

And Simpson, not yet understanding that women are never so

undecided as when specially emphatic, stood up and stared at her

again in speechless amazement. Then he burst into a torrent of

loud, reckless abuse, and with a final "You'll want me afoor I shall

want you!" he flung out of the bower and was gone.

Then the deep broke up in Dolly's soul; she flung herself

along the seat, burst into a passion of tears, indignation,

disillusionment, and terrible misgiving, all struggling together

within her, until she sank to the cold floor and pleaded fervently

for the Divine forgiveness.

CHAPTER II

THE MOCKERY OF THE DEAD

AND as Dolly

lingered sorrowfully in the summer-house, infinitely more distressed

with her exciting little episode than she had been for lack of it,

there was a sound of the opening of a distant door, followed by a

sharp whistle, performed evidently on human fingers. Dolly

heard without hearing, and went on with her painful dubitations.

The call was repeated, shriller than before, and supported by the

strident tones of a man's voice crying—

"Dolly! Dolly woman! Here wi' thee, sharp!"

Rising reluctantly to her feet, she began to move through the

gathering dusk towards the house, drying her eyes and composing her

face as she went.

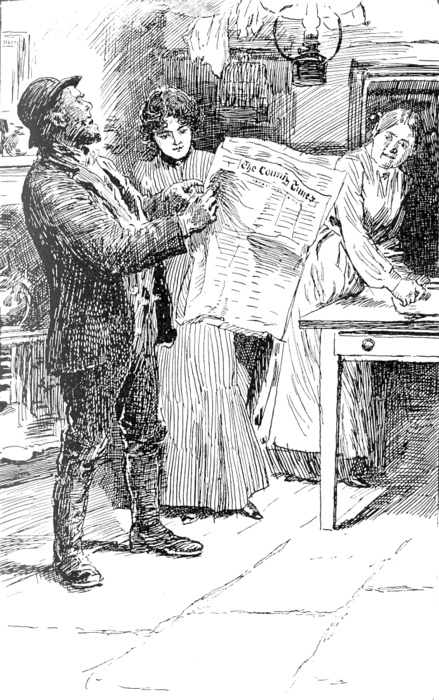

As she entered the large low kitchen, blinking her eyes at

the freshly lighted lamp, her father, usually indifferent enough to

her movements, was standing before a dim fire eagerly awaiting her

coming.

"Come on, woman! Throw thy cap up! It's come,

it's come! Thou'rt a lady, an' thy dad's a

gentleman!—gentleman!" he continued, as the full magnificence of the

idea unfolded itself before his eager mind. "By frost! that's

it. Look here, look here, Mrs W.!" and turning to a round,

portly, cherry-cheeked woman of about fifty, he smote himself

proudly on the chest and continued, "Phineas Wenyon, esquire,

gentleman and fancier."

Mrs Wenyon looked up at him with mild deprecation, but Dolly,

relieved to discover that something was forward that would prevent

her parents noticing her red eyes, cried as naturally as she could—

"Whatever's to do, father?"

"Do? It isn't to do—it's done! I'm a

gentleman and a fancier, and, by frost I'll teach them owd fossil o'

farmers summat now. Look here! " and he held out a newspaper,

and, pointing with a finger that shook with excitement, he held it

to the lamp for his daughter to read.

The paper was the great local authority, The County Times,

and Benderton, Snelsby, and Spattleshaw Reporter, and near the

top of the page was a short paragraph headed, "Death of an old

Townsman." Underneath the public were informed that one of the

oldest of the Benderton townsfolk, Mr Joshua Wenyon, had that

morning passed away unexpectedly at the ripe age of eighty-seven.

Dolly read it twice, raised her eyes to her father's and

smiled, and then, realising what a shocking thing it was to be glad

for another's death, subdued her face into becoming gravity.

"Don't whistle before you're out of the wood, Phineas."

This in the soft, musical tones of Mrs Wenyon.

"Whistle? It's there, woman, isn't it, in black and

white?"

"It's there, woman, isn't it, in black and white?"

"Ay, but there's many a slip twixt the cup and—"

"Go it, Unbelief! Go it, Mrs Double-damper! Thee

and thy mouldy proverbs! Thou wouldn't believe it wur wet if

thou were drownding in it! Who can he leave it to but us?"

"Blessed is he that expects nothing, Phineas. Don't

boil the pobs till the baby's born; don't count your chickens afore

they are hatched."

But at this moment there was a knock at the front door, and

John Sizer, one of Phineas's brother deacons, came in, a copy of the

Times in his hand, and a look of wonder on his face. He

was followed by Dick Leech, the painter, and Aaron Tibbs, and in a

few moments Phineas was the centre of an admiring circle of friends,

who discussed the amount of the dead man's possessions, the probable

date of the funeral, and other equally interesting matters.

Dolly, meanwhile, stole sadly about the house, wondering how she

would look in black, and what Simpson would think and do.

Now Phineas Wenyon was a red man: red hair, little sharp red

eyes, and red face. His body was heavy and sluggish, but his

mind was quick, versatile, and whimsical. By trade he was a

cooper, and, like most of the tradesmen of old-world Snelsby, had

inherited his business; his father and grandfather had taken care

that he should be the best cooper in the county, and necessity

compelled him to attend to his shop. His business, established

nearly a century, and amongst a community constitutionally averse to

change, enjoyed a monopoly in Snelsby, and he had an apprentice and

a journeyman as assistants.

His comfortable wife, and latterly his pretty daughter, were

both popular with the customers, and so the business largely took

care of itself, whilst Phineas was interested in and regarded

himself as an authority upon every trade in the neighbourhood—except

coopering. Volatile, talkative, self-opinionated, and

excessively curious, he had established himself as local critic and

censor, and woe to the unlucky wight who came under his lash.

In a stock-rearing community he posed as the apostle of advanced

ideas, scoffed unceasingly at "mouldy-brained" farmers who stuck by

traditional and inherited methods; he knew the points of a horse as

well as a breeder, could give you the weight of a fat beast to a

pound or two, and was the actual introducer of the famous "Nonsuch"

pigs. But his special foible was poultry; and since the time

that he had been chosen judge at the Benderton and Spattleshaw

Agricultural Show, the one ambition of his life had been to shake

himself loose from prosaic tubs and baskets, and set up as a

gentleman fowl-fancier and local poultry expert.

But "that eternal lack of pence, which vexes public men," had

so far been against the enterprising cooper; and though he had

always kept his head above water, his only hope of realising his

dreams had been the indecently postponed death of his Uncle Joshua.

That worthy, a childless widower who hated his wife's

relations a little more than he hated the rest of his fellows, had

no other connections; and as strong local sentiment and invariable

practice forbade the alienation of property by will, Phineas, though

never on terms with his relative, had lived on in expectation of the

legacy, and, though the cooper would have energetically denied it

himself, it is probable that this ancient hope had had something to

do with his distaste for his own trade.

Uncle Joshua had, however, proved most disappointingly tough,

and had never taken the slightest interest in his nephew. The

cooper, moreover, held strong views on the drink question, but the

old man was a property broker, and of late years had confined his

attention almost exclusively to licensed property. Once or

twice since then, he had gone out of his way to express his

disapproval of his nephew's teetotal views; but as, during a recent

illness, the old fellow had sent for Dolly and seemed very pleased

with her, the cooper hoped that the past was forgiven and that at

anyrate Uncle Joshua would not carry his resentment to the grave.

Phineas, elated and eager, talked all night, pouring scorn

and incredulous mockery on his wife's occasionally hinted proverbs

about the un-wisdom of over-confidence. Next day he spent his

time ordering funeral black and sketching airy plans, including the

transfer of the cooperage to his journeyman on the easiest possible

terms. Phineas, like other people, was very generous with what

he did not as yet possess. Dolly was almost as excited as her

father, and, glad of any escape from the reproaches of a tender

conscience, she dwelt eagerly upon their future prospects, and

became so very amiable that she presently resolved to send for

Simpson and "make it up."

But the note she received from her lover just before dinner

was a little too humble for Simpson, and suggested a little too

obviously that he also had heard of the family luck.

Consequently she put the note in her pocket with a petulant little

lift of the shoulders and a pensive sigh. There was small use

in showing grief under the circumstances, and Phineas Wenyon was the

last man in the world to pretend what he did not feel. The old

fellow now dead had scarcely ever acknowledged them, and had always

referred to Phineas with biting satire.

As soon as possible the cooper set off to Benderton to see

what he could discover about the old man and his possessions; but

nobody seemed to know anything, and everybody assumed that the

cooper was the heir and treated him accordingly. The formal

invitation to the funeral came in due course, and, arrayed in

uncomfortably fashionable black, Phineas took the market-day 'bus

that ran to Benderton, looking as solemn as it was possible for him

to do.

He "would be home by five o'clock" he had said, but when six

and then seven arrived and he had not returned, Dolly, uneasy all

day with her two-fold anxieties, grew almost ill with nervousness,

and poor "mother" had not even the energy to quote a proverb.

She had asked twice that day why Simpson did not come, and

Dolly had had some difficulty in putting her off; but now, as the

daughter sat, in spite of the heat, indoors, and mother went about

the house doing everything and nothing, a whistle broke on their

ears from the garden. Mrs Wenyon heard it and looked at Dolly.

Dolly heard it down to the tips of her fingers, but had got herself

so worked up about her father's errand and his unexplained delay

that she bent her head and went on with her needlework at feverish

speed.

"Dolly, don't you hear Simpson? That's the second

time—oh, here he is!" and in this sudden break off, "mother" hurried

across the kitchen, her hand on her heart, and they both looked

eagerly into the face of Phineas.

Alas! this was not the elated, triumphant man they hoped to

welcome, but neither was it mere crestfallen disappointment that sat

so heavily on his florid countenance; he was angry, worried,

disgusted, and dropped heavily into his seat.

Dolly heard her lover's whistle again, but she was watching

her father.

Mrs Wenyon, who was as hopeful in adversity as she was

fearful in prospective good luck, hurriedly popped teapot, toast,

and fried ham on the table, murmuring in her soft voice as she did

so—

"Heigho! The ring's gone, but the finger's safe."

Phineas was sulky and drew up with lowering face to the

table, taking his wife's, thoughtful ministerings without a sign.

There he sat with head down and eyes on his plate, glumly munching

his food, and apparently taking a revengeful pleasure in the

suspense of the women who were watching.

"Well, father, have you nothing to tell us?"

Mrs Wenyon glanced nervously at the privileged interrogator,

and shook her head, and Dolly waited for an answer that never came.

"Now, father, you're tormenting. I'm sure he's left us

something—a dying man—"

"Tormenting? Tormenting? It's him that's

tormenting. Drat him! Why, woman, he's tormenting us in

his very grave; he's snurching and grinning down there in the ground

this very minute—the wicked old varmint!"

"Speak no ill of the dead," came pleadingly from the corner

into which Mrs Wenyon had stolen.

"Ho!" cried Dolly dolefully, "and has he left us nothing?"

"Nothin'? Who said 'is left us nothin'? He's left

us too much, the spiteful old rogue!"

"Too much? Oh, father, what do you mean?" and Dolly was

wringing her hands and hovering nervously over him, whilst even her

mother had drawn nearer.

"Now, look you here, you two," and the cooper laid down his

knife and fork with two emphatic bangs, rose to his feet, and

expanding his chest and tapping it with his open palm, be demanded,

"am I a respectable, God-fearing man, or am I not?"

"Well?"

"Am I a deacon of the church?"

"Well?"—both together and with breathless eagerness.

"Am I a lifelong abstainer and a Band of Hoper?"

"Well, well! Go on!"

Phineas drew back to give due effect to his staggering

announcement, looked hard at his wife and then at Dolly, drew a long

hard breath, ground his teeth together, and then said—

"Well, that old spiteful's left us a PUBLIC

HOUSE," and when he reached the last two

words, the outraged cooper shouted them out at the top of his voice.

There was a long pregnant pause, an exchange of amazed and

horrified looks, and then the ingenious wickedness of the idea

struck Dolly forcibly, and she burst into a long, rippling laugh.

"Dolly!" cried Mrs Wenyon in shocked, reproachful tones, and

the amused girl, checking herself as another thought struck her,

made a straight face and cried—

"But you can sell it, father!"

"Sell it, woman! That's it! That's the crafty

spitefulness of it; we are to have it on condition."

"What condition?"

"On condition—ha! ha!" and catching suddenly his daughter's

point of view, he laughed in angry, baffled helplessness—"on

condition that we live in it!"

For a full minute the three stood looking chapfallenly at

each other, and then Dolly said, though with little heart—

"Never mind, dad, we'll let it go and take the rest."

"Rest? What rest?"

"The other property. He has left us something else?"

"Not a stick, not a dolt! Every blessed stick goes to

her."

"Her?"

"His old housekeeper. The crafty, scheming old

skinflint, let him take his old alehouse, and be hanged to him!"

Helpless with sheer surprise, Mrs Wenyon dropped into her

chair, and Phineas, now got going, plunged into a detailed account

of the funeral and the reading of the will; and then for several

minutes strutted about the kitchen denouncing the dead man and all

his malicious ways. The bequest was so ingeniously wicked, so

mockingly, tantalisingly clever, and so extremely characteristic of

the acrid, cynical old man who had made it, that in spite of himself

the cooper had to laugh every now and again. Joshua Wenyon had

always been a mocker; he had mocked at religion, mocked at

temperance, mocked at the virtues of his neighbours; but this

bequest of his was the bitterest and cleverest mock of all.

The cooper realised this, at least in part, as he stalked

about the kitchen; but before long he became conscious that he had

but half grasped the deadly wickedness of the contrivance.

Even sleepy Snelsby woke up when the story became known.

The landlord of the Red Lion laughed until he cried; the cooper's

customers also heard and re-told the tale until it became almost

unrecognisable; the chapel people received it at first with

incredulous head-shakes, and then with indignation mingled with

alarm; and Nixon the brewer went about amongst Phineas's temperance

friends, openly jeering at them, and offering to bet the price of a

barrel of beer that the valiant teetotal cooper would turn landlord.

CHAPTER III

JEFFREY TWIGG WANTS A CROSS-AND GETS ONE

AND whilst the

cooper and his family were agitating themselves about old Wenyon's

will, other events were transacting themselves in another part of

Snelsby which were destined to have an important effect on Dolly's

future. Away down the white highroad from Snelsby to

Benderton, there was an old tollhouse with an apartment at each side

of the road. The gate of course was gone and toll no longer

taken, but the small buildings were occupied by old Jeffrey Twigg

and his wife. Jeff was the local bill-sticker and bellman, and

his wife a monthly nurse. He was long, lank, and bony, and she

was short even for a woman. She was a round, black-eyed,

apple-cheeked little person, about fourteen years younger than her

great lumbering husband; and he had weak, oddly coloured eyes, a

wandering sort of mouth with lips habitually nipped together in a

vain attempt to express a decision of character most conspicuously

absent. His most eloquent feature, however, was a long queer

nose which terminated most unexpectedly in a tell-tale red bulb;

this was generally browned with snuff, for Jeff's one weakness was a

fondness for the fragrant dust, which he carried loose in the

left-hand pocket of his sleeved corduroy waistcoat. Mrs Twigg

was a loyal churchwoman; Jeff was a leading light at a little

nondescript Bethel in Frog Lane: a place conducted on most

democratic lines, but which had a reputation for reclaiming

character quite out of proportion to its relative position amongst

local churches.

Just about dusk on the night when our story opens, the two

were sitting in the low porch of the tollhouse, enjoying the cool

evening breezes, Mrs Twigg knitting, and her lord taking his

favourite indulgence and meditating. As he thought, he grew

fidgety; his beetling brows went up and his mouth corners came down;

he was evidently discontented. He glanced scowlingly at his

provokingly placid little wife, crossed and re-crossed his legs,

thrust his thumb and forefinger deep into his snuff pocket, raised

the dust to his nose, and then said, punctuating each word with a

long sniff—

"I'm sick o' this sort a wark; I'm nor a Christian, an' I

niver wur."

Mrs Twigg apparently saw nothing in this to reply to, so Jeff

curled his discontented lip and added—

"For two pins I'd chuck t' job."

An exasperating click! click! of the needles was the only

response.

Another lingering sniff at his dusty finger-ends, another

discontented side-glance at his wife, and then—

"Tommy, thou can say what thou's a mind! T' Almighty's

not dealing wi' me as I should like."

Mrs Twigg's baptismal name was Thomasina, but the Snelsby

folk usually abbreviated it to 'Siná, whilst her husband preferred

"Tommy."

"Jeffrey, for shame! Does to know it's blasphemious!"

The bill-sticker gave a couple of defiant, unbelieving

sniffs, leaned back into the corner of the porch, cocked his chin,

and sighed again.

"I tell thee it is so, say what thou likes."

"Jeff!"

"There's Owd Simmy and Lizer Cribble," he continued, "allus

grumblin' an' groanin' about their trials; an' here's me as 'ud jump

at 'em, never gets none at all," and then he added after a grieved

review of the case, "No, not t' odd un."

"Is that all! Thou talks about crosses as if they were

good things and thou wanted 'em. Thou'd cry at t'other side o'

thy face if thou had one."

Solemnly shaking his head and helping himself to snuff, Jeff

replied—

"Thou'rt no theologian, Tommy; you church folk knows nowt

about doctrine."

Mrs Twigg had evidently her own views on that point, but was

not sure whether it was worth while to advance them; and whilst she

was hesitating, Jeff was pursuing his own reflections.

"Whom the Lord loveth He chasteth—when has He ever chasted

me?"

"For shame, Jeffrey Twigg! Thou'll be bringin' summat

on thee, talkie' like that."

"He's given old Lizer many a cross, and poor Tommy too, but

He's never given me a single, solitary one—not one."

"Go on! Go on! That's t' way to get thy crop

full. Dunnat blame me if trubbel comes; thou's asked for it."

"Does the Lord ever chaste me? That's t' question," and

a cloud of fragrant dust puffed off from Jeff's glowing nose, and he

eyed his spouse with an injured look. Presently he went on,

secretly triumphing in a sour sort of way over his wife's

argumentative helplessness, "I've told thee afore, and I'll tell

thee again, Jeff Twigg's not in the kingdom."

Siná, was expecting this; all his roundabout theological

arguments landed him at this point, and so she burst out

impatiently—

"No, and thou doesn't deserve to be! Them as isn't

content wi' Providence deserves to be miserable."

But the bill-sticker had heard this reproof before, and no

longer regarded it. He was following the argument as it

developed in his own mind, and taking in snuff in prodigious

quantities.

"There's Lizer and Sammy and Long Peter, as hesn't the pluck

o' mice, but they can have as many crosses as they like; and here's

me never gets a chance. How can I show me paces? How can

I dare to be a Daniel and 'hold the fort'?"

Mrs Twigg looked troubled; perhaps she did not know enough of

theology; this sort of doctrine was certainly beyond her, and so,

whilst she mused and he sniffed, there was a pause.

"Never seek trouble, Jeffrey; rest and be thankful; never

seek—oh, lawks, what's that!"

Jeff had evidently heard something too, and sat with a pinch

of snuff on its way to his nose, listening. As the sound was

not repeated, he affected superiority to feminine imaginings, and

growled about women being "feared of a frog's croak."

"'A horse! my kingdom for a horse!'"

The night had shut down dark and starless, and the slightest

sound rang far in the still air. Jeff and his wife sprang to

their feet with scared faces, and stared hard at each other.

The very silence became disquieting, and Jeff began to edge

towards his wife. "It's nothin', woman—oh, la!" and as Jeff

made a frightened grab at his wife's arm, there rang out on the

stillness—

"'Avaunt, thou dreadful minister of hell!'"

and there was a crashing sound like the breaking of a hedge or the

falling of a tree, and Jeff, with a "Lord preserve us!" flung his

arms round his wife. Tremors were shaking them both, and their

faces in the darkness grew white and terrified. To be

disturbed at night was not very unusual in their wayside abode, but

there was something about this that was uncanny.

"Chut, man, it's nobbut a beast coming through—oh, la!"

"'Blow me in winds; roast me in sulphurs."'

Dropping back for a moment and wildly taking her courage in

her hands, Mrs Twigg snatched at her husband, and, dragging him to

the porch front, shrieked, "Thieves! Murder!" though her

excitement choked the words and the sounds did not travel.

For several moments the two stood gazing into the darkness,

and at last Thomasina, knowing well who would have to take the first

move, stooped down, and, catching sight as she did so of a dim

figure in the grass, cried, though with bated breath—

"Drat the thing, it's nobbut somebody in drink!"

She stopped, however, and shrank back again for there was a

long lugubrious groan, which changed into a sort of chant and ended

in a blood-curdling "Ha! ha! ha!"

Another pause, and then Thomasina, straining her eyes to

discern the vague object in the road, cried with fearsome valiance—

"Now, then, there, budge!"

"Come back, lass, and shut t' door," cried Jeff in a thick

whisper.

"'Angels and ministers of grace—'"

"We're not angels; we're quiet folk as pays our way.

Off wi' thee, swill-tub!"

"Oh, my poor eyes! If nobbut I could see," groaned Jeff

apologetically.

"Eyes! It's thy heart, man; it's down i' thy boots,

man; get a light wi' thee," and then raising her voice, she called

across the road, "March off now, Rantipole!"

Jeff had obeyed orders, but was in his excitement running

against everything in the darkness, and making such a disturbance

that his wife had discovered the candle before him. Meanwhile

scraps of incoherent quotation, which Jeff mistook for Scripture,

and Thomasina contemptuously denominated "rubbish," were coming

through the darkness, and presently husband and wife were groping

fearfully across the way, Jeff apologetically lamenting his weak

eyesight and Thomasina carefully screening the sputtering flame with

her hand. Mrs Twigg was of course in front, and was making for

the dim heap she could faintly see from the doorway. Jeff,

stumbling after her, fell over some stones, and they soon discovered

that the object they were making for was a pile of new road-metal.

Jeff discovered it first, and, springing back, knocked springing the

candle out of his wife's hand, whilst a wailing cry rang out on the

still air—

"'Farewell! a last farewell to all my greatness.'"

"Hush! Oh, drat it!" Mrs Twigg had touched something

soft with her toe, and as they stood there helpless in the darkness,

the long tragic farewell was repeated close to them. Jeff

sprang away, and, returning hastily returning to the porch, began to

exhort his wife to come away.

A few moments later, however, the two were cautiously

stooping over the prostrate form of a man, who, with a thin,

emaciated, but still youthful face, in which was a gash, was

reclining against the hedge-backing and declaiming miscellaneous

Shakespere with alternations of mock solemnity and serio-comic

hilarity which sent throbs of wondering pity to the hearts of his

simple beholders.

"Another tramp!" growled Jeff, eyeing the sprawling figure at

a safe distance. "Let him lie t' night air will bring him to."

"Ay, an' a bit o' common sense 'ud bring thee to;

does'ta see he's wounded? Poor feller!" and then, after a

closer inspection with the flickering candle, "Pick him up, man, an'

bring him across t' road."

Jeff sprang back with dubious shakings of the head, still

keeping his eye warily on the recumbent figure.

"Tramps is infected; he'll happen give uz summat."

"I'll give thee summat if thou doesn't lift him

up—here, tak' hold," and holding the candle towards him she went on,

"He's happen dyin', and then wee'st be took up for manslaughter."

Jeff, watching narrowly the limp and silent figure, moved

obliquely round and began cautiously to approach the tramp.

Putting his back against the hedge, he got behind his man, stopping

suddenly every now and again at some fancied sound or movement; and

then bending his long body he got hold of the stranger under each

arm and lifted him gingerly and with averted face. There was a

gurgling chuckle and a murmuring gurgling quotation—

"'Oh, beautiful tyrant, fiend angelical,'"

and Jeff, nearly dropping his burden, sank back into the hedge with

a startled gasp.

Mrs Twigg lost patience, and began to demand that he would

take the candle and let her do the work, and so in confused, hasty

shame, the big man, ostentatiously holding his head away, dragged

the still muttering tramp with trailing legs into the little cot.

Ten minutes later the stranger showed signs of coming to, and

Jeff, standing off, indulged in a leisurely survey, assisting his

meditations with copious doses of snuff. Thomasina had lighted

the fire and was already bathing the tramp's wounds with warm water.

This, however, as it increased the bleeding, scared her, and Jeff

was peremptorily commanded to fetch the doctor. The

bill-sticker looked blue, and eyed the patient sourly: a half-mile

journey to a not very patient doctor was no joke at this hour; and

as he lingered sheepishly, and grunted out protests, his wife had to

hasten him. When he returned with the medico she had got the

patient's face washed, and though he was still only half conscious,

had ascertained several curious things about him. Whatever

else, he was not drunk: neither was he a tramp of the ordinary sort;

for his hands, though dirty enough, were small and white, whilst the

skin underneath his ragged underclothing indicated a person of

fastidious habits. His tattered garments were so full of dust

that a little cloud arose every time he was moved. His

features had refinement stamped on every line of them, and the

accent of his incoherent ramblings was that of an educated person.

The doctor came in blusteringly, still abusing the much

persecuted snuff-taker; but he went suddenly quiet when he saw the

wound, and quieter still when he examined the patient's pulse and

temperature. He rapped out his orders in snarling tones,

stitched the gaping gash, stood back and glared at the patient, as

though he had committed some fearful crime, and then, whisking round

and stopping a pinch of snuff on its way to Jeff's nose, he

demanded—

"I suppose you two old fools think this man is dying—well, he

isn't,—that is, not of his wound he's starving; he hasn't had food

for days!"

"Lawk-a-days!" began Mrs Twigg, but the doctor hadn't

finished.

"Get him to bed; give him broth and milk—not too much at

once, mind—and if he pulls round by to-morrow, get a barrow and

wheel him to the workhouse."

"But you'll come, doctor, and—"

"What's that to you? Do as I tell you, and woe betide

you if he dies!" and, with a look of unexampled fierceness, the man

of boluses banged the door until the still road rang, and left them

to their task.

The next three days were the most tormenting in Jeff's life.

His wife had all a childless woman's passion for nursing anything

and everything that came in her way, and all a nurse's unreasonable

imperiousness. Their only bed in the cot across the road was

appropriated for this disreputable, spouting tramp; his wife

occupied the long settle, and he had to stretch his long legs where

he could. His wife was inevitable and had to be endured, but

why should he be tyrannised over by a rambling, raving lodger, a

starvation footpad, simply because he "hed sich grand eyes and

quoted poetry"?

The patient was certainly a most extraordinary person.

He was so thin and emaciated, and his eyes were so sunken and

haggard-looking, that Mrs Twigg had a fresh gush of tears every time

she looked at him. He seemed to be in a perpetual state of

intoxication, but the doctor's testimony and their own knowledge

contradicting that, they found it difficult to decide when and how

far he was sane. There were moments when his great eyes swam

with glowing gratitude as he followed them about; but the moment

they spoke to him the look became a scowl, and he flung at them

disjointed and incomprehensible blank verse. Thomasina treated

him as a spoilt child, much too ill to be corrected; but Jeff,

tantalised and worried by a curiosity which never received the

slightest consideration, went about with ruffled feathers and always

ready to quarrel.

"Poor, poor fellow, then! Who are yo and where do yo

come from?" said Mrs Twigg, when late on the fourth day the tramp

looked quieter and more reasonable.

A soft, grateful light came into the patient's eyes; but as

Jeff could not see this sign of intelligence, he stepped up to the

bedside and bawled, as though deafness were an inseparable

accompaniment of insanity—

"She wants to know thy name."

The languid sufferer bounced up as though shot.

"Name? I'm Bard of Avon, the immortal William; my name

is Shakespere;" and he flourished his arms, made a sitting bow, and

leered at Mrs Twigg, until Jeff began to feel jealous.

To Jeff, Shakespere was a mythical British hero of King

Arthur's class; but not a copper had been found in the tramp's

clothes, and so the bill-sticker shook his head in amused

contradiction, whilst 'Siná coaxed the patient's arms under the

bedclothes again.

"Ay, then, sure then, did he say his name was William?

Lie thee down, duckie, William."

Jeff, listening to these coaxings with growing restlessness,

went away lest he should be tempted to say something; but next day,

after an unusually trying night with the sick man, he broke into

open rebellion and threatened to fetch the wheelbarrow ordered by

the doctor. Mrs Twigg offered prompt and decided resistance.

"Poor fellow? Why, woman, he calls me all the foul

names he can put his tongue to!"

"Names?"

"Ay, names! Bruter an' Bellydick, an' las' night he

wanted to cuddle me an' called me 'Jeff demona'—he'll be calling me

Beelzebub next."

As the days went on and the stranger slowly improved, the old

couple became more and more perplexed about him, and more and more

at variance with each other. He had long hours of

absent-minded musings, from which neither coaxings nor scoldings

would arouse him. In the daytime he would get up and sit on

the bedside, and presently he began to appropriate, without the

slightest sign of any conscious irregularity, such articles of

Jeff's wearing apparel as might be within reach, and by the end of

the week, Jeff, with the careless consent of the doctor, had decided

to remove the poor fellow to the workhouse. Mrs Twigg,

however, proved obstinate, and Jeff had no refuge left but his

precious dust.

"Shakespere," as he still persisted in calling himself, was

now sufficiently recovered to get about a little, though he seemed

strangely indifferent, and had no desire whatever either to "take

the road," or have any sort of contact with life and society.

Mrs Twigg was using rum for some domestic purpose one day, but the

smell of it produced such wild agitation in the stranger's mind that

they passed the worst night with him they had ever experienced.

He snatched the rum from her and drank it off ravenously; his eyes

rolled, his face flushed, and he became suddenly another man.

He was light, frisky, jocular, then stern, tragic, and sarcastic;

and even after they got him safely to bed, he was rolling out

Shakesperian selections. Even Mrs Twigg repented at this, and

Jeff had hope that the incident would bring him deliverance.

But the next morning found the "great dramatist" in a new

mood. He lay in bed and followed them about with great

pleading, anguished eyes, and refused with earnest protests all

food, shrinking as he did so from Mrs Twigg, as though he feared his

touch might pollute her. The first time Jeff came near he

snatched eagerly at his snuffy hand, and, pressing it to burning

lips, passionately covered it with kisses, and wept like a sorry

child.

Little by little the terrible truth sank into the minds of

the bill-sticker and his wife that their unbidden and distressing

guest was a dipsomaniac, and that night they had a long and anxious

talk together.

Jeff had much to do to convince himself, and much more to

convince his wife, and when at last he had shown her how impossible

it was for them to do anything, and how much more reasonable it was

to let "Shakespere" go to the workhouse, she was just bringing

herself to accept the inevitable, when a great inspiration came to

the assistance of her pitiful, reluctant heart, and touching her

husband gently on the arm, she cried—

"Why, Jeff, that's it! That's the very thing."

Jeff rubbed his dusty nose and glowered dubiously at her.

"It's a big'un and a queer 'un, but it's just the thing for

thee."

"Wot, woman? wot?"

"Why, what thou been wantin' this many a day!"

Jeff helped himself again, eyed her earnestly, and then said—

"I don't know what thou means."

"What wur thou wantin' t'other day?" asked Thomasina.

Jeff took two heavy pinches, but no light came.

"Weren't thou wantin' a cross, a burdin, somethin' to do for

the Lord?"

Jeff stared and stared, and then nodded with dreamy, distant

eyes that were only just taking in the full significance of the

suggestion, and at last he gave her an emphatic tap on the knee,

rose up, and went into the lane and thought the matter fully out.

And that night, as he lay upon the hearth-rug trying to

sleep, he kept murmuring to himself—

"He's sent it at last! There's a chance for me here."

And he dropped off to sleep, drowsily repeating, "Whom the

Lord loveth He chasteth."

CHAPTER IV

SIMPSON CROUCH MAKES A HELPFUL SUGGESTION

NOW if old Joshua

Wenyon, when he inserted that ingeniously mischievous paragraph in

his will which related to his cooper-nephew, had intended to disturb

as many people and create as many heartburnings as possible, he

certainly succeeded; and if he had been able after his decease to

visit Snelsby, and still retained his old bitter feeling towards his

fellow-creatures, he would have been abundantly satisfied with the

results of his malign device; for the bequest sent the iron deep

into the breasts of his relatives, and produced powerful effects

upon the minds of people of whom the misanthropic old wretch had

never thought. Simpson Crouch, for instance. When that

very worldly-wise young man got away from his sweetheart on the

night of their quarrel and thought things over, he was more disposed

than ever to resent her conduct. He was most unpleasantly

surprised to begin with; this was a new and not at all attractive

side of her character, and he had no idea at all of a wife with such

notions. Besides, things were prospering with him just then—he

was doing rather better than usual, in fact; and, after all, she was

not the only girl in the marriage-market, and, his improving

prospects considered, not quite the catch he might make. At

anyrate he was not going to be treated like this quietly; she had

made the quarrel and she must mend it. It was a reasonable and

fair thing that the old building which brought next to nothing to

her father, but would be so very serviceable to him, should come

along with her when they married; and even though she should wish to

be reconciled, he would stick to his point. Of course she

would repent, and—happy thought!—in that mood would be more pliable

even than usual; nay, if she was the girl he took her for, she would

square her father as a means of reconciliation with him. It

took some time to reach this point, for Simpson did not think

quickly; but when, as he crossed the High Street on his way home, he

heard of old Joshua's death, it reminded him of one of the motives

of his engagement and entirely changed his views. The old

fellow who was gone must have had anything from five to twenty-five

thousand pounds, and there was absolutely nobody for it worth

thinking of but the cooper and his family.

A thousand pounds or so would make a vast difference to his

business, and he would be able to make the local bobbin-trade "hum."

These considerations affected his view of Dolly's temper, and

the unjustifiable quarrel rapidly shrank to the dimensions of a

little tiff. He knew Dolly, if anybody did: knew her softness

and tenderness of heart; he must not be too hard on the whims and

freaks of a girl's fancies, and—well—perhaps it was as much his

fault as hers.

He wrote what he considered a reasonably conciliatory note

that very night, and rested all the better for it.

Twice next day he made errands down Sticky Lane, which ran

along the bottom end of the cooperage garden, but did not succeed in

seeing Dolly. For three long fretful hours he haunted the old

lane next night, but still no Dolly. Then he sent another and

much humbler note, and, following it up promptly, went and sat in

the summer-house which had been the scene of their unfortunate

disagreement, and whistled the old signal. But the hitherto

placable, easy-tempered young lady was still obdurate. The

thing was getting serious: here was the whole town talking about the

Wenyons' luck; his housekeeper sister chaffed him so bitingly about

marrying a fortune that there was no peace at home for him, and all

at once there came to him the terrible suspicion that Dolly had

manufactured the quarrel in order to get him out of the way now that

she was going to be rich. Simpson felt himself going very

sick; clammy perspiration oozed out of his pores, and he muttered

something very like a curse. But he was not the man to miss a

chance like this; he would humble himself, abase himself if need be,

but Dolly and her fortune must be his; and, in fact, he had so long

regarded her as his own that he had a sense now of being robbed.

The one person likeliest to help him was Dolly's mother, and,

curiously enough, this gentle-spirited person was the one member of

the family of whom he stood most in fear. Fear or no fear, he

must make his position secure, even though he had to swallow his

resentment and put his pride in his pocket. Before approaching

Mrs. Wenyon, however, he decided to try another night of garden

watching, and when that failed and he got home surly and taciturn,

his sister greeted him with the details of the fantastic will as it

was known to Snelsby.

Simpson's ardour cooled again at once, but, thinking it over

in his favourite place of meditation, his bed, a brilliant idea

struck him, and the more he thought of it, the more was he

enamoured.

It was not the fortune he had once hoped for, but it was a

great deal better than nothing. Yes, that was what he must do;

only, to the success of this latest project reconciliation with

Dolly was absolutely necessary.

Over next day's dinner his sister regaled him with the latest

gossip; the public-house mentioned in the will was no other than the

King's Arms, the most respectable and prosperous hostel in Snelsby,

and not many doors from the cooper's shop. Simpson pricked his

ears, and the scheme he had elaborated in the night seemed more

alluring than ever.

"It'ud be a sight to see teetotal Phineas a landlord," be

remarked, to keep his sister talking.

"He never will be," was the curt reply.

"Never will be? And why not?" and Simpson sounded

distinctly injured.

"His women won't let him. Maria Boskill was saying that

they'd both set their faces again' it, and declared they'd sooner

take in washin'."

Simpson's heart sank, for he could very well believe it.

Dolly and her mother were just the sort of narrowly religious folk

who, devoid of all true business instincts, would take a perverse

pride in sacrificing a comfortable competency for some romantic and

ridiculous scruple. He must bestir himself, he must take

prompt measures, or the prize would slip through his fingers; it was

no use arguing with unaccountable and "pious" women; he must apply,

and that without loss of time, to the cooper himself. And when

he thought of Phineas he breathed more freely. The tubber was

a man at least, and would at anyrate take a reasonable businesslike

view of things. He was prone to silly fads and hobbies, and

was given to run to odd extremes, but he had an eye to the main

chance, and was as keen a bargainer as ever stood in Snelsby market.

Besides, Phineas, it was notorious, did not like his own business,

and badly wanted leisure and especially larger means for the

indulgence of his fancies; and Simpson hugged himself as he

reflected that the plan he could suggest would be an almost

irresistible temptation to a man of his prospective father-in-law's

proclivities.

And then—yes, his plan was nothing short of an

inspiration—the cooper, though always soft with women, a doting

husband and father, was notoriously pigheaded and pugnacious, as all

faddy men were, and if only he could be got to entertain the notion

that people were interfering with him, then the more wife and

daughter and friends and chapel people protested, the more surely

would Phineas stick to his point.

Simpson, for reasons he could not have explained, had more

misgivings about the cooper's teetotalism than about his religion;

but then the plan he could suggest would give Phineas more relief

than any other device he could think of, consistent with the

retention of the bequest; and as it would set him almost entirely

free to carry out his dearly cherished hobbies, without any

anxieties about the awkward question of bread and butter—well, if

Phineas was able to resist the double-barrelled temptation, then

Simpson didn't understand human nature at all. Thinking about

his quarrel with Dolly, he felt inclined to kick himself; it was

about the unluckiest thing that could have happened just then.

But she was not the girl to carry every little thing to her parents,

and would, if he knew her, be so very self-conscious about her own

share of the matter, that he thought he might safely leave that

point; and the excitement about the fortune would be so fully

occupying her mind that the occurrences in the summerhouse would

have left far less impression upon her than at another time.

At anyrate, even if his worst fears proved correct, he could not

think of giving up now, at least, without a very serious effort.

The bobbin factory was sadly neglected that day, and Simpson

made journey after journey past the cooperage in hope of seizing

some opportunity. Unfortunately the fates were against him.

The cooper's workshop, a low lean-to that stood alongside the house

and faced the street, had at this time of the year its big front

door always open, but whenever Simpson lounged past the place it was

full of visitors. Now it was Phineas's coadjutors from the

temperance hall, next the vicar and his wife, and at another time no

less than four chapel folk. The bobbin-maker did not like this

at all; be knew but too well how both the cleric and the chapel folk

would talk, and he realised that unless a spoke was put in the

wheel, and that speedily, Phineas, who was very susceptible to

attention, might be talked over and commit himself.

All sorts of rumours meanwhile were current, equal confidence

being expressed on both sides, and the result seemed to prove to

Simpson that the cooper was "wobbling." That very night,

therefore, carefully dressed and industriously schooled by his

astute sister, he turned out to get by any possible means an

interview with the much-talked-of "heir."

He loitered about the road near the shop, inwardly grinding

his teeth as first one and then another garrulous Snelsbyite came or

went; and when at last the apprentice closed the big door and the

popular cooper strolled out of the workshop into his house

accompanied by closest friends, Simpson felt inclined to give the

thing up for the night. But the case was important and time

pressing: the whole thing might be settled by any one of those

interminable conversations going on with the man of the moment, and

so, torn with conflicting emotions, Simpson lingered about, seeing

little use in staying and yet sadly loth to go.

At the moment when he was just giving up, the front door of

the Wenyons' house suddenly opened, and all the cooper's visitors,

still talking loudly and excitedly, came forth into the twilight,

and such scraps of talk as the bobbin-maker could catch showed him

that whatever he did must be done with the utmost despatch.

As soon, therefore, as the last good-night had been shouted

along the road, and before the cooper could close the door, Simpson

came out of his retreat and commenced—

"G'd evenin', Phineas; goin' a bit cooler, isn't it?"

Wenyon absently admitted that it was, and then, turning his

back upon his visitor, silently led the way into the "room," as the

cooperage parlour was called. It was no uncommon thing for

Simpson to have a smoke with Phineas and his cronies, when there was

anything particular to talk about; and so the man of tubs, to whom

talk was the breath of life, pointed first at a chair and then at a

pudgy tobacco jar, and sat down with the restrained modesty of a man

who was getting used to congratulations and supposed they had to be

endured.

Simpson eyed his host narrowly as he filled his pipe, and

would have given much to know the exact state of his mind on the

important issue.

"Well, allow me to congratulate you on your luck, Phineas."

Phineas puckered his brows with an excellent pretence of

momentary forgetfulness.

"Wh—oh, that, er—um."

"Um" was not very illuminating, and Simpson stole a sidelong

look through the tobacco-smoke and waited for additional light,

which, however, did not come.

"Well, you've managed to make yourself t' talk o' th' town

for once, at anyrate."

Phineas closed his eyes meekly, and expanded a little; the

fact had to be admitted, but modesty forbade any comment.

But the bobbin-maker could not hold in, though he carefully

picked his words.

"Well, I always did say that the King's Arms was the neatest

bit of licensed property in the county," and then, giving a

considering inclination to his head and an interrogative inflexion

to his voice, he went on, "It'ull be worth a couple o' thousand

pound, I daresay."

"Couple? Couple? That place is worth three an' a

half, if it's worth sixpence!"

Ah, then he was considering the question and there was still

time! Simpson plucked up his spirits and went on.

"It's so many out-buildings! Why, there's room there

for any amount of fancying: stables, barns, fowl-houses, piggeries,

and everything as a fancier could want! My stars, Phineas, you

could show them farmers summat! "

"Show 'em!" and the cooper fired up instantly—"I'll show them

jockeys what hens is, an' pigs and pigeons, Simpson lad. I'll

make 'em bite their finger ends off wi' spite!"

It was working: Simpson secretly hugged himself. He

paused with crafty deliberation, eyed his man closely, and then,

leaning forward and tapping the cooper on the knee with his

pipe-stem, one tap to every word, he said in tones of absolute,

unalterable conviction—

"Phineas, if there's any man i' this countryside could do it,

it's you; and, by George, I'd like to see you do it!"

The cooper was now on his high horse.

"Do it! Why, man, if them poverty-stricken owd farmers

knew what I know they'd be Millionaires i' no time."

"O' course they would, and if I wur you I'd show 'em;" and

then, with a sudden show of high moral conviction, "Why, it's your

duty, man, an' you can't get out of it."

The cooper sat upright in his chair, his legs spread out and

his chest expanded, whilst his face shone through the smoke with

glowing self-complacency. But even as he thought the light

faded, the vision of glory clouded over, and with a long regretful

sigh for that which could never be, he murmured—

"Ay, but I cannot do it."

"Do it! Why not? Why, man, it's the chance of a

lifetime!" and Simpson sounded sternly reproachful.

Phineas sighed again, pulled moodily at his pipe for a

moment, and then, in tones of sad regret, he said—

"It's again' my principles."

"Principles! What has principles to do with it?

It's a matter o' business, man!"

Another sigh, a series of reluctant wags of the head, and

then—

"I'm a Christian, an'—an'—a deacon."

"What, you, Phineas! I thought you'd more sense!

Religion's religion, but business is business!" and then he added

resentfully, "I see how it is, them muddlin' owd jockeys from t'

chapil's been at you."

"They've niver ge'en me a minute's peace this blessed day,"

and Phineas had a grieved and injured tone.

"Oh, drat 'em! Now, look here: has any of them owd

jackasses ever been wo'th a twenty-pound note all their born days?

Will they ever be?"

A little twitch of disapproval, too slight for the eager

bobbin-man to notice, passed across the cooper's countenance, but he

only shook his head and stared dubiously into the tobacco clouds.

Presently, however, he said dolefully—

"What would they all think about me?"

"Think? Let 'em think! An' answer me one

question. Is there one man of all t' lot as 'ud refuse three

thousand pound?—answer me that."

Phineas pulled heavily at his pipe, shook his head again, and

replied—

"But, man, I'm a lifelong teetotaler!"

"An' so is lots o' public-landlords; all t' best on 'em is:

they have to be. Now, look you here, man, we cannot do without

some sort of places like publics, can we? It isn't t' places,

it's t' way they're conducted that's wrong; what this country wants

is somebody to show 'em how they ought to be managed, and the man

who'd do that 'ud be a public blessing."

This was an aspect of the great temperance question that as

yet had not presented itself to the cooper, and, coming just now, it

looked most dangerously plausible, and he proceeded to argue it; and

Simpson, perceiving his advantage, made the most of it, and they

talked and smoked until they could not see each other. The

cooper at last got up and lighted the lamp, and then, as he adjusted

the wick, he said—

"I could never bring myself to do it; but it's a pity to let

all that property go."

"Pity! It 'ud be a burning shame! Every sensible

person i' th' town'ud laugh at thee, man," and then he added—for the

supreme moment had come—"Besides, there's more ways o' killin' a dog

nor chokin' him wi' butter."

Phineas was slowly wiping the paraffin from his fingers,

whilst his hand shook with the strength of his emotions. It

seemed that what he really wanted was some middle way, and the

tempter, watching him keenly, went on—

"Wills is like Acts o' Parlyment, gumptious folk can drive a

coach an' four through 'em."

The cooper was looking hard at him with a curious mixture of

hope and fear in his eyes.

"Simpson, I'd give half of what I've got this minute to best

that owd wastrel."

"Well, there's ways"; and the bobbin-maker, leaning back and

apparently studying a stuffed jackdaw on the mantelpiece, looked

most tantalisingly mysterious.

"Ay, but not right ways, honest, straight ways?"

"Honest enough and easy enough," and the crafty Simpson

talked like a man who was not interested, and was, in fact, getting

tired of the subject, whilst Phineas had to sit down to control his

rising excitement.

"Easy as chips. I could do it."

"Thee?"

"Ay, me! Give me t' chalice, that's all."

"Whatever art drivin' at, Simpson?" and Phineas's voice was

husky with suppressed eagerness.

The tempter, his eye still on the jackdaw, had a confident

smile, though his heart was beating almost into his mouth.

"Out with it, man; what's i' thy head?" and the cooper's

eagerness was pitiable. Slowly Simpson withdrew his gaze from

the jackdaw, pulled himself together, put on a look of preternatural

mystery, and dropping his voice to a thick whisper he looked bard at

his man, and remarked—

"A man can live in a drink shop without selling drink."

Phineas returned the other's stare with interest, his rapidly

beating eyelids being the only things about him that moved.

"Wh—a—wh—a—what does ta' mean?"

But Simpson now had the upper hand, and knew it; and so,

rolling his head to one side, he drawled with studied indifference—

"Nay, nuthin', but a wink's as good as a nod to a blind

horse."

Half guessing and yet uncertain, with scowling face and

trembling voice the cooper glared at his visitor, and cried

fiercely—

"Go on, man! Out with it!"

But Simpson was cruel. His scheme had grown more

precious and encouraging as he played with it and watched its

effects upon his friend; and so, after a series of hum's and ha's,

he said—

"Me and your Dolly's thinkin' o' getting wed afore long."

"Well?"

"We might—we might hurry it up a bit."

"Well?"

"You could take t' King's Arms and live in private parts, an'

have all them outhouses for your hens, an'—an'—an' we could do t'

business."

Phineas saw it now, that was plain; he rose to his feet, drew

himself up, took a step nearer, and asked in quite a different tone—

"Who could do t' business?"

"Uz, me an' her."

"Dolly? our Dolly?"

"Ay."

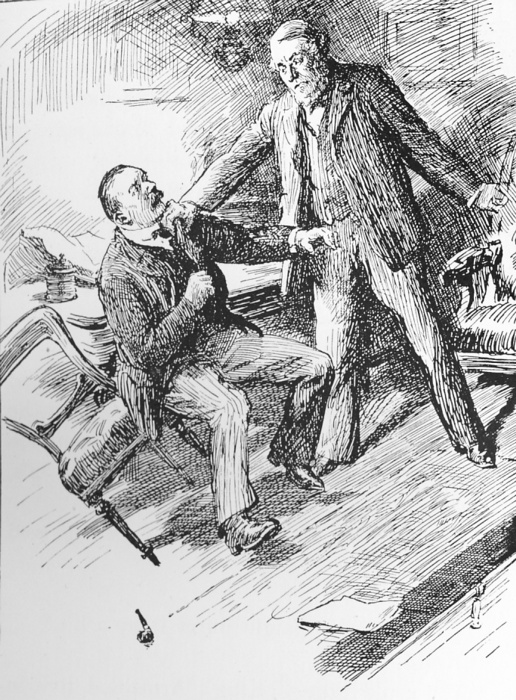

The transformation was instantaneous and amazing.

There, towering over the astounded and cringing bobbin-maker, stood

Phineas, white with scorn and rage.

"Thou limb o' Satan! Thou slimy, slippery snake i' th'

grass!" and, pouncing on his visitor with a grip of iron, he dragged

him from his seat, kicked the chair from under him, pushed him with

purpling face to the door, and flung him out into the darkness,

crying thickly as he did so, "Git out! Git out! Git

out!"

"Pouncing on his visitor, he dragged him from his

seat, crying

"Git out! Git out! Git out!" |