|

[Previous

Page]

SUPPLEMENTARY.

IT is told of the "Spectator," on his own high

authority, that having "read the controversies of some great men

concerning the antiquities of Egypt, he made a voyage to Grand Cairo on

purpose to take the measure of a pyramid, and that, so soon as he had set

himself right in that particular, he returned to his native country with

great satisfaction." My love of knowledge has not carried me

altogether so far, chiefly, I daresay, because my voyaging opportunities

have not been quite so great. Ever since my ramble of last year,

however, I have felt, I am afraid, a not less interest in the geologic

antiquities of Small Isles than that cherished by the "Spectator" with

respect to the comparatively modern antiquities of Egypt; and as, in a

late journey to these islands, the object of my visit involved but a

single point, nearly as insulated as the dimensions of a pyramid, I think

I cannot do better than shelter myself under the authority of the

short-faced gentleman who wrote articles in the reign of Queen Anne.

I had found in Eigg, in considerable abundance and fine keeping, reptile

remains of the Oolite; but they had occurred in merely rolled masses,

scattered along the beach. I had not discovered the bed in which

they had been originally deposited, and could neither tell its place in

the system, nor its relation to the other rocks of the island. The

discovery was but a half-discovery,—the half of a broken medal, with the

date on the missing portion. And so, immediately after the rising of

the General Assembly in June last [1845], I set out to revisit Small

Isles, accompanied by my friend Mr Swanson, with the determination of

acquainting myself with the burial place of the old Oolitic reptiles, if

it lay anywhere open to the light.

We found the Betsey riding in the anchoring ground at Isle

Ornsay, in her foul-weather dishabille, with her topmast struck and in the

yard, and her cordage and sides exhibiting in their weathered aspect the

influence of the bleaching rains and winds of the previous winter.

She was at once in an undress and getting old, and, as seen from the shore

through rain and spray,—for the weather was coarse and boisterous,—she had

apparently gained as little in her good looks from either circumstance as

most other ladies do. We lay stormbound for three days at Isle

Ornsay, watching from the window of Mr Swanson's dwelling the incessant

showers sweeping down the loch. On the morning of Saturday, the

gale, though still blowing right ahead, had moderated; the minister was

anxious to visit this island charge, after his absence of several weeks

from them at the Assembly; and I, more than half afraid that my term of

furlough might expire ere I had reached my proposed scene of exploration,

was as anxious as he; and so we both resolved, come what might, on

doggedly beating our way adown the Sound of Sleat to Small Isles. If

the wind does not fail us, said my friend, we have little more than a

day's work before us, and shall get into Eigg about midnight. We had

but one of our seamen aboard, for John Stewart was engaged with his potato

crop at home; but the minister was content, in the emergency, to rank his

passenger as an able-bodied seaman; and so, hoisting sail and anchor, we

got under way, and, clearing the loch, struck out into the Sound.

We tacked in long reaches for several hours, now opening up

in succession the deep withdrawing lochs of the mainland, now clearing

promontory after promontory in the island district of Sleat. In a

few hours we had left a bulky schooner, that had quitted Isle Ornsay at

the same time, full five miles behind us; but as the sun began to decline,

the wind began to sink; and about seven o'clock, when we were nearly

abreast of the rocky point of Sleat, and about half-way advanced in our

voyage, it had died into a calm; and for full twenty hours thereafter

there was no more sailing for the Betsey. We saw the sun set, and

the clouds gather, and the pelting rain come down, and night fall, and

morning break, and the noon-tide hour pass by, and still were we floating

idly in the calm. I employed the few hours of the Saturday evening

that intervened between the time of our arrest and nightfall, in fishing

from our little boat for medusæ with a

bucket. They had risen by myriads from the bottom as the wind fell,

and were mottling the green depths of the water below and around far as

the eye could reach. Among the commoner kinds,—the kind with the

four purple rings on the area of its flat bell, which ever vibrates

without sound, and the kind with the fringe of dingy brown, and the long

stinging tails, of which I have sometimes borne from my swimming

excursions the nettle-like smart for hours,—there were at least two

species of more unusual occurrence, both of them very minute. The

one, scarcely larger than a shilling, bore the common umbiliferous form,

but had its area inscribed by a pretty orange-coloured wheel; the other,

still more minute, and which presented in the water the appearance of a

small hazel-nut of a brownish-yellow hue, I was disposed to set down as a

species of beroe. On getting one caught, however, and transferred to

a bowl, I found that the brownish-coloured, melon-shaped mass, though

ribbed like the beroe, did not represent the true outline of the animal:

it formed merely the centre of a transparent gelatinous bell, which,

though scarce visible in even the bowl, proved a most efficient instrument

of motion. Such were its contractile powers, that its sides nearly

closed at every stroke, behind the opaque orbicular centre, like the legs

of a vigorous swimmer; and the animal, unlike its more bulky

congeners,—that, despite of their slow but persevering flappings, seemed

greatly at the mercy of the tide, and progressed all one way,—shot, as it

willed, backwards, forwards, or athwart. As the evening closed, and

the depths beneath presented a dingier and yet dingier green, until at

length all had become black, the distinctive colours of the acelpha,—the

purple, the orange, and the brown,—faded and disappeared, and the

creatures hung out, instead, their pale phosphoric lights, like the

lanthorns of a fleet hoisted high to prevent collision in the darkness.

Now they gleamed dim and indistinct as they drifted undisturbed through

the upper depths, and now they flamed out bright and green, like beaten

torches, as the tide dashed them against the vessel's sides. I

bethought me of the gorgeous description of Coleridge, and felt all its

beauty:—

|

They moved in tracks of shining white,

And when they reared, the elfish light

Fell off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship

I watched their rich attire,—

Blue, glassy green, and velvet black:

They curled, and swam, and every track

Was a flash of golden fire. |

A crew of three, when there are watches to set, divides

wofully ill. As there was, however, nothing to do in the calm, we

decided that our first watch should consist of our single seaman, and the

second of the minister and his friend. The clouds, which had been

thickening for hours, now broke in torrents of rain, and old Alister got

into his water-proof oil-skin and souwester, and we into our beds.

The seams of the Betsey's deck had opened so sadly during the past winter,

as to be no longer water-tight, and the little cabin resounded drearily in

the darkness, like some dropping cave, to the ceaseless patter of the

leakage. We continued to sleep, however, somewhat longer than we

ought,—for Alister had been unwilling to waken the minister; but we at

length got up, and, relieving watch the first from the tedium of being

rained upon and doing nothing, watch the second was set to do nothing and

be rained upon in turn. We had drifted during the night-time on a

kindly tide, considerably nearer our island, which we could now see

looming blue and indistinct through the haze some seven or eight miles

away. The rain ceased a little before nine, and the clouds rose,

revealing the surrounding lands, island and main,—Rum, with its abrupt

mountain-peaks,—the dark Cuchullins of Skye,—and, far to the south-east,

where Inverness bounds on Argyllshire, some of the tallest hills in

Scotland,—among the rest, the dimly-seen Ben-Nevis. But long wreaths

of pale gray cloud lay lazily under their summits, like shrouds half drawn

from off the features of the dead, to be again spread over them, and we

concluded that the dry weather had not yet come. A little before

noon we were surrounded for miles by an immense but thinly-spread shoal of

porpoises, passing in pairs to the south, to prosecute, on their own

behalf, the herring fishing in Lochfine or the Gareloch; and for a full

hour the whole sea, otherwise so silent, became vocal with long-breathed

blowings, as if all the steam-tenders of all the railways in Britain were

careering around, us; and we could see slender jets of spray rising in the

air on every side, and glossy black backs and pointed fins, that looked as

if they had been fashioned out of Kilkenny marble, wheeling heavily along

the surface. The clouds again began to close as the shoal passed,

but we could now hear in the stillness the measured sound of oars, drawn

vigorously against the gunwale in the direction of the island of Eigg,

still about five miles distant, though the boat from which they rose had

not yet come in sight. "Some of my poor people," said the minister,

"coming to tug us ashore!" We were boarded in rather more than half

an hour after,—for the sounds in the dead calm had preceded the boat by

miles,—by four active young men, who seemed wonderfully glad to see their

pastor; and then, amid the thickening showers, which had recommenced heavy

as during the night, they set themselves to tow us unto the harbour.

The poor fellows had a long and fatiguing pull, and were thoroughly

drenched ere, about six o'clock in the evening, we had got up to our

anchoring ground, and moored, as usual, in the open tide-way between

Eilan Chasteil and the main island. There was still time enough

for an evening discourse, and the minister, getting out of his damp

clothes, went ashore and preached.

The evening of Sunday closed in fog and rain, and in fog and

rain the morning of Monday arose. The ceaseless patter made dull

music on deck and skylight above, and the slower drip, drip, through the

leaky beams, drearily beat time within. The roof of my bed was

luckily water-tight; and I could look out from my snuggery of blankets on

the desolations of the leakage, like Bacon's philosopher surveying a

tempest from the shore. But the minister was somewhat less

fortunate, and had no little trouble in diverting an ill-conditioned drop

that had made a dead set at his pillow. I was now a full week from

Edinburgh, and had seen and done nothing; and, were another week to pass

after the same manner,—as, for aught that appeared, might well happen,—I

might just go home again, as I had come, with my labour for my pains.

In the course of the afternoon, however, the weather unexpectedly cleared

up, and we set out somewhat impatiently through the wet grass, to visit a

cave a few hundred yards to the west of Naomh Fraing, in which it

had been said the Protestants of the island might meet for the purposes of

religious worship, were they to be ejected from the cottage erected by Mr

Swanson, in which they had worshipped hitherto. We re-examined, in

the passing, the pitch-stone dike mentioned in a former chapter, and the

charnel cave of Francis; but I found nothing to add to my former

descriptions, and little to modify, save that perhaps the cave appeared

less dark, in at least the outer half of its area, than it had seemed to

me in the former year, when examined by torchlight, and that the

straggling twilight, as it fell on the ropy sides, green with moss and

mould, and on the damp bone-strewn floor, overmantled with a still darker

crust, like that of a stagnant pool, seemed also to wear its tint of

melancholy greenness, as if transmitted through a depth of seawater.

The cavern we had come to examine we found to be a noble arched opening in

a dingy-coloured precipice of augitic trap,—a cave roomy and lofty as the

nave of a cathedral, and ever resounding to the dash of the sea; but

though it could have amply accommodated a congregation of at least five

hundred, we found the way far too long and difficult for at least the weak

and the elderly, and in some places inaccessible at full flood ; and so we

at once decided against the accommodation which it offered. But its

shelter will, I trust, scarce be needed.

On our return to the Betsey, we passed through a straggling

group of cottages on the hill-side, one of which, the most dilapidated and

smallest of the number, the minister entered, to visit a poor old woman,

who had been bed-ridden for ten years. Scarce ever before had I seen

so miserable a hovel. It was hardly larger than the cabin of the

Betsey, and a thousand times less comfortable. The walls and roof,

formed of damp grass-grown turf, with a few layers of unconnected stone in

the basement tiers, seemed to constitute one continuous hillock, sloping

upwards from foundation to ridge, like one of the lesser moraines of

Agassiz, save where the fabric here and there bellied outwards or inwards,

in perilous dilapidation, that seemed but awaiting the first breeze.

The low chinky door opened direct into the one wretched apartment of the

hovel, which we found lighted chiefly by holes in the roof. The back

of the sick woman's bed was so placed at the edge of the opening, that it

had formed at one time a sort of partition to the portion of the

apartment, some five or six feet square, which contained the fire-place;

but the boarding that had rendered it such had long since fallen away, and

it now presented merely a naked rickety frame to the current of cold air

from without. Within a foot of the bed-ridden woman's head there was

a hole in the turf-wall, which was, we saw, usually stuffed with a bundle

of rags, but which lay open as we entered, and which furnished a downward

peep of sea and shore, and the rocky Eilan Chasteil, with the

minister's yacht riding in the channel hard by. The little hole in

the wall had formed the poor creature's only communication with the face

of the external world for ten weary years. She lay under a dingy

coverlet, which, whatever its original hue, had come to differ nothing in

colour from the graveyard earth, which must so soon better supply its

place. What perhaps first struck the eye was the strange flatness of

the bed-clothes, considering that a human body lay below: there seemed

scarce bulk enough under them for a human skeleton. The light of the

opening fell on the corpse-like features of the woman, —sallow, sharp,

bearing at once the stamp of disease and of famine; and yet it was

evident, notwithstanding, that they had once been agreeable,—not unlike

those of her daughter, a good-looking girl of eighteen, who, when we

entered, was sitting beside the fire. Neither mother nor daughter

had any English; but it was not difficult to determine, from the welcome

with which the minister was greeted from the sick-bed, feeble as the tones

were, that he was no unfrequent visitor. He prayed beside the poor

creature, and, on coming away, slipped something into her hand. I

learned that not during the ten years in which she had been bed-ridden had

she received a single farthing from the proprietor, nor, indeed, had any

of the poor of the island, and that the parish had no session-funds.

I saw her husband a few days after,—an old worn-out man, with famine

written legibly in his hollow cheek and eye, and on the shrivelled frame,

that seemed lost in his tattered dress; and he reiterated the same sad

story. They had no means of living, he said, save through the

charity of their poor neighbours, who had so little to spare; for the

parish or the proprietor had never given them anything. He had once,

he added, two fine boys, both sailors, who had helped them; but the one

had perished in a storm off the Mull of Cantyre, and the other had died of

fever when on a West India voyage; and though their poor girl was very

dutiful, and staid in their crazy hut to take care of them in their

helpless old age, what other could she do in a place like Eigg than just

share with them their sufferings? It has been recently decided by

the British Parliament, that in cases of this kind the starving poor shall

not be permitted to enter the law courts of the country, there to sue for

a pittance to support life, until an intermediate newly-erected court,

alien to the Constitution, before which they must plead at their own

expense, shall have first given them permission to prosecute their claims.

And I doubt not that many of the English gentlemen whose votes swelled the

majority, and made it such, are really humane men, friendly to an

equal-handed justice, and who hold it to be the peculiar glory of the

Constitution, as well shown by De Lolme, that it has not one statute-book

for the poor, and another for the rich, but the same law and the same

administration of law for all. They surely could not have seen that

the principle of their Poor Law Act for Scotland sets the pauper beyond

the pale of the Constitution in the first instance, that he may be starved

in the second. The suffering paupers of this miserable island

cottage would have all their wants fully satisfied in the grave, long ere

they could establish at their own expense, at Edinburgh, their claim to

enter a court of law. I know not a fitter case for the interposition

of our lately formed "Scottish Association for the Protection of the Poor"

than that of this miserable family; and it is but one of many which the

island of Eigg will be found to furnish.

After a week's weary waiting, settled weather came at last;

and the morning of Tuesday rose bright and fair. My friend, whose

absence at the General Assembly had accumulated a considerable amount of

ministerial labour on his hands, had to employ the day professionally; and

as John Stewart was still engaged with his potato crop, I was necessitated

to sally out on my first geological excursion alone. In passing

vessel-wards, on the previous year, from the Ru Stoir to the

farmhouse of Keill, along the escarpment under the cliffs, I had examined

the shores somewhat too cursorily during the one half of my journey, and

the closing evening had prevented me from exploring them during the other

half at all; and I now set myself leisurely to retrace the way backwards

from the farm-house to the Stoir. I descended to the bottom

of the cliffs, along the pathway which runs between Keill and the solitary

midway shieling formerly described, and found that the basaltic columns

over head, which had seemed so picturesque in the twilight, lost none of

their beauty when viewed by day. They occur in forms the most

beautiful and fantastic; here grouped beside some blind opening in the

precipice, like pillars cut round the opening of a tomb, on some

rock-front in Petræa; there running in

long colonnades, or rising into tall porticoes; yonder radiating in

straight lines from some common centre, resembling huge pieces of

fan-work, or bending out in bold curves over some shaded chasm, like rows

of crooked oaks projecting from the steep sides of some dark ravine.

The various beds of which the cliffs are composed, as courses of ashlar

compose a wall, are of very different degrees of solidity: some are of

hard porphyritic or basaltic trap; some of soft Oolitic sandstone or

shale. Where the columns rest on a soft stratum, their foundations

have in many places given way, and whole porticoes and colonnades hang

perilously forward in tottering ruin, separated from the living rock

behind by deep chasms. I saw one of these chasms, some five or six

feet in width, and many yards in length, that descended to a depth which

the eye could not penetrate; and another partially filled up with earth

and stones, through which, along a dark opening not much larger than a

chimney-vent, the boys of the island find a long descending passage to the

foot of the precipice, and emerge into light on the edge of the grassy

talus half-way down the hill. It reminded me of the tunnel in the

rock through which Imlac opened up a way of escape to Rasselas from the

happy valley,—the "subterranean passage," begun "where the summit hung

over the middle part," and that "issued out behind the prominence."

|

|

|

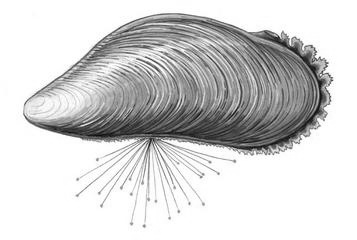

Avicula |

Mytilus |

From the commencement of the range of cliffs, on half-way to

the shieling, I found the shore so thickly covered up by masses of trap,

the debris of the precipices above, that I could scarce determine the

nature of the bottom on which they rested. I now, however, reached a

part of the beach where the Oolitic beds are laid bare in thin

party-coloured strata, and at once found something to engage me.

Organisms in vast abundance, chiefly shells and fragmentary portions of

fishes, lie closely packed in their folds. One limestone bed,

occurring in a dark shale, seems almost entirely composed of a species of

small oyster; and some two or three other thin beds, of what appears to be

either a species of small Mytilus or Avicula, mixed up with a few shells

resembling large Paludina, and a few more of the gaper family, so closely

resembling existing species, that John Stewart and Alister at once

challenged them as smurslin, the Hebridean name for a well-known

shell in these parts,—the Mya truncata. The remains of

fishes,—chiefly Ganoid scales and the teeth of Placoids,—lie scattered

among the shells in amazing abundance. On the surface of a single

fragment, about nine inches by five, which I detached from one of the

beds, and which now lies before me, I reckon no fewer than twenty-five

teeth, and twenty-two on the area of another. They are of very

various forms,—some of them squat and round, like ill-formed small

shot,—others spiky and sharp, not unlike flooring nails,—some straight as

needles, some bent like the beak of a hawk, some, like the palatal teeth

of the Acrodus of the Lias, resemble small leeches; some, bearing a series

of points ranged on a common base, like masts on the hull of a vessel, the

tallest in the centre, belong to the genus Hybodus. There is a

palpable approximation in the teeth of the leech-like form to the teeth

with the numerous points. Some of the specimens show the same

plicated structure common to both; and on some of the leech backs, if I

may so speak, there are protuberant knobs, that indicate the places of the

spiky points on the hybodent teeth. I have got three of each kind

slit up by Mr George Sanderson, and the internal structure appears to be

the same. A dense body of bone is traversed by what seem innumerable

roots, resembling those of woody shrubs laid bare along the sides of some

forest stream. Each internal opening sends off on every side its

myriads of close-laid filaments; and nowhere do they lie so thickly as in

the line of the enamel, forming, from the regularity with which they are

arranged, a sort of framing to the whole section. It is probable that the

Hybodus,—a genus of shark which became extinct some time about the

beginning of the chalk,—united, like the shark of Port Jackson, a crushing

apparatus of palatal teeth to its lines of cutting ones. Among the

other remains of these beds I found a dense fragment of bone, apparently

reptilian, and a curious dermal plate punctulated with thickset

depressions, bounded on one side by a smooth band, and altogether closely

resembling some saddler's thimble that had been cut open and straightened.

Following the beds downwards along the beach, I found that

one of the lowest which the tide permitted me to examine,—a bed coloured

with a tinge of red,—was formed of a denser limestone than any of the

others, and composed chiefly of vast numbers of small univalves resembling

Neritæ. It was in exactly such a

rock I had found, in the previous year, the reptile remains; and I now set

myself with no little eagerness to examine it. One of the first

pieces I tore up contained a well-preserved Plesiosaurian vertebra; a

second contained a vertebra and a rib; and, shortly after, I disinterred a

large portion of a pelvis. I had at length found, beyond doubt, the

reptile remains in situ. The bed in which they occur is laid

bare here for several hundred feet along the beach, jutting out at a low

angle among boulders and gravel, and the reptile remains we find embedded

chiefly in its under side. It lies low in the Oolite. All the

stratified rocks of the island, with the exception of a small Liasic

patch, belong to the Lower Oolite, and the reptile-bed occurs deep in the

base of the system,—low in its relation to the nether division, in which

it is included. I found it nowhere rising to the level of high-water

mark. It forms one of the foundation tiers of the island, which, as

the latter rises over the sea in some places to the height of about

fourteen hundred feet, its upper peaks and ridges must overlie the bones,

making allowance for the dip, to the depth of at least sixteen hundred.

Even at the close of the Oolitic period this sepulchral stratum must have

been a profoundly ancient one. In working it out, I found two fine

specimens of fish jaws, still retaining their ranges of teeth,—ichtbyodorulites,—occipital

plates of various forms, either reptile or ichthyic,—Ganoid scales, of

nearly the same varieties of pattern as those in the Weald of

Morayshire,—and the vertebræ and ribs,

with the digital, pelvic, and limb-bones, of saurians. It is not

unworthy of remark, that in none of the beds of this deposit did I find

any of the more characteristic shells of the system,—Ammonites,

Belemnites, Gryphites, or Nautili.

I explored the shores of the island on to the Ru Stoir,

and thence to the Bay of Laig; but though I found detached masses of the

reptile bed occurring in abundance, indicating that its place lay not far

beyond the fall of ebb, in no other locality save the one described did I

find it laid bare. I spent some time beside the Bay of Laig in

re-examining the musical sand, in the hope of determining the

peculiarities on which its sonorous qualities depended. But I

examined and cross-examined it in vain. I merely succeeded in

ascertaining, in addition to my previous observations, that the loudest

sounds are elicited by drawing the hand slowly through the incoherent

mass, in a segment of a circle, at the full stretch of the arm, and that

the vibrations which produce them communicate a peculiar titillating

sensation to the hand or foot by which they are elicited, extending in the

foot to the knee, and in the hand to the elbow. When we pass the wet

finger along the edge of an ale-glass partially filled with water, we see

the vibrations thickly wrinkling the surface: the undulations which,

communicated to the air, produce sound, render themselves, when

communicated to the water, visible to the eye; and the titillating feeling

seems but a modification of the same phenomenon acting on the nerves and

fluids of the leg or arm. It appears to be produced by the

wrinklings of the vibrations, if I may so speak, passing along sentient

channels. The sounds will ultimately be found dependent, I am of

opinion, though I cannot yet explain the principle, on the purely

quartzose character of the sand, and the friction of the incoherent upper

strata against under strata coherent and damp. I remained ten days

in the island, and went over all my former ground, but succeeded in making

no further discoveries.

On the morning of Wednesday, June 25th, we set sail for Isle

Ornsay, with a smart breeze from the north-west. The lower and upper

sky was tolerably clear, and the sun looked cheerily down on the deep blue

of the sea; but along the higher ridges of the land there lay long level

strata of what the meteorologists distinguish as parasitic clouds.

When every other patch of vapour in the landscape was in motion, scudding

shorewards from the Atlantic before the still-increasing gale, there

rested along both the Scuir of Eigg and the tall opposite ridge of the

island, and along the steep peaks of Rum, clouds that seemed as if

anchored, each on its own mountain-summit, and over which the gale failed

to exert any propelling power. They were stationary in the middle of

the rushing current, when all else was speeding before it. It has

been shown that these parasitic clouds are mere local condensations of

strata of damp air passing along the mountain summits, and rendered

visible but to the extent in which the summits affect the temperature.

Instead of being stationary, they are ever-forming and ever-dissipating

cloud,—clouds that form a few yards in advance of the condensing hill, and

that dissipate a few yards after they have quitted it. I had nothing

to do on deck, for we had been joined at Eigg by John Stewart; and so,

after watching the appearance of the stationary clouds for some little

time, I went below, and, throwing myself into the minister's large chair,

took up a book. The gale meanwhile freshened, and freshened yet

more; and the Betsey leaned over till her lee chain-plate lay along in the

water. There was the usual combination of sounds beneath and around

me,—the mixture of guggle, clunk, and splash,—of low, continuous rush, and

bluff, loud blow, which forms in such circumstances the voyager's concert.

I soon became aware, however, of yet another species of sound, which I did

not like half so well,—a sound as of the washing of a shallow current over

a rough surface; and, on the minister coming below, I asked him, tolerably

well prepared for his answer, what it might mean. "It means," he

said, "that we have sprung a leak, and a rather bad one; but we are only

some six or eight miles from the Point of Sleat, and must soon catch the

land." He returned on deck, and I resumed my book. Presently,

however, the rush became greatly louder; some other weak patch in the

Betsey's upper works had given way, and anon the water came washing up

from the lee side along the edge of the cabin floor. I got upon deck

to see how matters stood with us; and the minister, easing off the vessel

for a few points, gave instant orders to shorten sail, in the hope of

getting her upper works out of the water, and then to unship the companion

ladder, beneath which a hatch communicated with the low strip of hold

under the cabin, and to bring aft the pails. We lowered our

foresail; furled up the mainsail half-mast high; John Stewart took his

station at the pump; old Alister and I, furnished with pails, took ours,

the one at the foot, the other at the head, of the companion, to hand up

and throw over; a young girl, a passenger from Eigg to the mainland, lent

her assistance, and got wofully drenched in the work; while the minister,

retaining his station at the helm, steered right on. But the gale

had so increased, that, notwithstanding our diminished breadth of sail,

the Betsey, straining hard in the rough sea, still lay in to the gunwale;

and the water, pouring in through a hundred opening chinks in her upper

works, rose, despite of our exertions, high over plank, and beam, and

cabin floor, and went dashing against beds and lockers. She was

evidently filling, and bade fair to terminate all her voyagings by a short

trip to the bottom. Old Alister, a seaman of thirty years' standing,

whose station at the bottom of the cabin stairs enabled him to see how

fast the water was gaining on the Betsey, but not how the Betsey was

gaining on the land, was by no means the least anxious among us.

Twenty years previous he had seen a vessel go down in exactly similar

circumstances, and in nearly the same place; and the reminiscence, in the

circumstances, seemed rather an uncomfortable one. It had been a bad

evening, he said, and the vessel he sailed in, and a sloop, her companion,

were pressing hard to gain the land. The sloop had sprung a leak,

and was straining, as if for life and death, under a press of canvass.

He saw her outsail the vessel to which he belonged, but, when a few

bow-shots a-head, she gave a sudden lurch, and disappeared from the

surface instantaneously, as a vanishing spectre, and neither sloop nor

crew were ever more heard of.

There are, I am convinced, few deaths less painful than some

of those untimely and violent ones at which we are most disposed to

shudder. We wrought so hard at pail and pump,—the occasion, too, was

one of so much excitement, and tended so thoroughly to awaken our

energies,—that I was conscious, during the whole time, of an exhilaration

of spirits rather pleasurable than otherwise. My fancy was active,

and active, strange as the fact may seem, chiefly with ludicrous objects.

Sailors tell regarding the flying Dutchman, that he was a hard-headed

captain of Amsterdam, who, in a bad night and head wind, when all the

other vessels of his fleet were falling back on the port they had recently

quitted, obstinately swore that, rather than follow their example, he

would keep beating about till the day of judgment. And the Dutch

captain, says the story, was just taken at his word, and is beating about

still. When matters were at the worst with us, we got under the lee

of the point of Sleat. The promontory interposed between us and the

roll of the sea; the wind gradually took off; and after having seen the

water gaining fast and steadily on us for considerably more than an hour,

we, in turn, began to gain on the water. It came ebbing out of

drawers and beds, and sunk downwards along pannels and table-legs,—a

second retiring deluge; and we entered Isle Ornsay with the cabin-floor

all visible, and less than two feet water in the hold. On the

following morning, taking leave of my friend the minister, I set off, on

my return homewards, by the Skye steamer, and reached Edinburgh on the

evening of Saturday.

END OF THE CRUISE OF THE BETSEY

_____________________________

RAMBLES OF A GEOLOGIST;

OR,

TEN THOUSAND MILES OVER THE FOSSILIFEROUS

DEPOSITS OF SCOTLAND. [1]

CHAPTER I.

FROM circumstances that in no way call for

explanation, my usual exploratory ramble was thrown this year (1847) from

the middle of July into the middle of September; and I embarked at Granton

for the north just as the night began to count hour against hour with the

day. The weather was fine, and the voyage pleasant. I saw by

the way, however, at least one melancholy memorial of a hurricane which

had swept the eastern coasts of the island about a fortnight before, and

filled the provincial newspapers with paragraphs of disaster. Nearly

opposite where the Red Head lifts its mural front of Old Red Sandstone a

hundred yards over the beach, the steamer passed a foundered vessel, lying

about a mile and a half off the land, with but her topmast and the point

of her peak over the surface. Her vane, still at the mast-head, was

drooping in the calm; and its shadow, with that of the fresh-coloured spar

to which it was attached, white atop and yellow beneath, formed a

well-defined undulatory strip on the water, that seemed as if ever in the

process of being rolled up, and yet still retained its length unshortened.

Every recession of the swell showed a patch of mainsail attached to the

peak: the sail had been hoisted to its full stretch when the vessel went

down. And thus, though no one survived to tell the story of her

disaster, enough remained to show that she had sprung a leak when

straining in the gale, and that, when staggering under a press of canvass

towards the still distant shore, where, by stranding her, the crew had

hoped to save at least their lives, she had disappeared with a sudden

lurch, and all aboard had perished. I remembered having read, among

other memorabilia of the hurricane, without greatly thinking of the

matter, that "a large sloop had foundered off the Red Head, name unknown."

But the minute portion of the wreck which I saw rising over the surface,

to certify, like some frail memorial in a churchyard, that the dead lay

beneath, had an eloquence in it which the words wanted, and at once sent

the imagination back to deal with the stern realities of the disaster, and

the feelings abroad to expatiate over saddened hearths and melancholy

homesteads, where for many a long day the hapless perished would be missed

and mourned, but where the true story of their fate, though too surely

guessed at, would never be known.

The harvest had been early; and on to the village of

Stonehaven, and a mile or two beyond, where the fossiliferous deposits end

and the primary begin, the country presented from the deck only a wide

expanse of stubble. Every farm-steading we passed had its piled

stack-yard; and the fields were bare. But the line of demarcation

between the Old Red Sandstone and the granitic districts formed also a

separating line between an earlier and later harvest; the fields of the

less kindly subsoil derived from the primary rocks were, I could see,

still speckled with sheaves; and, where the land lay high, or the exposure

was unfavourable, there were reapers at work. All along in the

course of my journey northward from Aberdeen I continued to find the

country covered with shocks, and labourers employed among them; until,

crossing the Spey I entered on the fossiliferous districts of Moray; and

then, as in the south, the champaign again showed a bare breadth of

stubble, with here and there a ploughman engaged in turning it down.

The traveller bids farewell at Stonehaven to not only the Old Red

Sandstone and the early-harvest districts, but also to the rich

wheat-lands of the country, and does not again fairly enter upon them

until, after travelling nearly a hundred miles, he passes from Banffshire

into the province of Moray. He leaves behind him at the same line

the wheat-fields and the cottages built of red stone, to find only barley

and oats, and here and there a plot of rye, associated with cottages of

granite and gneiss, hyperstene and mica schist; but on crossing the Spey,

the red cottages re-appear, and fields of rich wheat-land spread out

around them, as in the south. The circumstance is not unworthy the

notice of the geologist. It is but a tedious process through which

the minute lichen, settling on a surface of naked stone, forms in the

course of ages a soil for plants of greater bulk and a higher order; and

had Scotland been left to the exclusive operation of this slow agent, it

would be still a rocky desert, with perhaps here and there a strip of

alluvial meadow by the side of a stream, and here and there an insulated

patch of rich soil among the hollows of the crags. It might possess

a few gardens for the spade, but no fields for the plough. We owe

our arable land to that comparatively modern geologic agent, whatever its

character, that crushed, as in a mill, the upper parts of the

surface-rocks of the kingdom, and then overlaid them with their own debris

and rubbish to the depth of from one to forty yards. This debris,

existing in one locality as a boulder-clay more or less finely comminuted,

in another as a grossly pounded gravel, forms, with few exceptions, that

subsoil of the country on which the existing vegetation first found root;

and, being composed mainly of the formations on which it more immediately

rests, it partakes of their character, bearing a comparatively lean and

hungry aspect over the primary rocks, and a greatly more fertile one over

those deposits in which the organic matters of earlier creations lie

diffused. Saxon industry has done much for the primary districts of

Aberdeen and Banff-shires, though it has failed to neutralize altogether

the effects of causes which date as early as the times of the Old Red

Sandstone; but in the Highlands, which belong almost exclusively to the

non-fossiliferous formations, and which were, on at least the western

coasts, but imperfectly subjected to that grinding process to which we owe

our sub-soils, the poor Celt has permitted the consequences of the

original difference to exhibit themselves in full. If we except the

islands of the Inner Hebrides, the famine of 1846 was restricted in

Scotland to the primary districts.

I made it my first business, on landing in Aberdeen, to wait

on my friend Mr Longmuir, that I might compare with him a few geological

notes, and benefit by his knowledge of the surrounding country. I

was, however, unlucky enough to find that he had gone, a few days before,

on a journey, from which he had not yet returned; but, through the

kindness of Mrs Longmuir, to whom I took the liberty of introducing

myself, I was made free of his stone-room, and held half an hour's

conversation with his Scotch fossils of the Chalk. These had been

found, as the readers of the Witness must remember from his

interesting paper on the subject, on the hill of Dudwick, in the

neighbourhood of Ellon, and were chiefly impressions—some of them of

singular distinctness and beauty—in yellow flint. I saw among them

several specimens of the Inoceramus, a thin-shelled, ponderously-hinged

conchifer, characteristic of the Cretaceous group, but which has no living

representative; with numerous flints, traversed by rough-edged, bifurcated

hollows, in which branched sponges had once lain; a well-preserved Pecten;

the impressions of spines of Echini of at least two distinct species; and

the nicely-marked impression of part of a Cidaris, with the balls on which

the sockets of the club-like spines had been fitted existing in the print

as spherical moulds, in which shot might be cast, and with the central

ligamentary depression, which in the actual fossil exists but as a minute

cavity, projecting into the centre of each hollow sphere, like the wooden

fusee into the centre of a bomb-shell. This latter cast, fine and

sharp as that of a medal taken in sulphur, seems sufficient of itself to

establish two distinct points: in the first place, that the siliceous

matter of which the flint is composed, though now so hard and rigid, must,

in its original condition, have been as impressible as wax softened to

receive the stamp of the seal; and, in the next, that though it was thus

yielding in its character, it could not have greatly shrunk in the process

of hardening. I looked with no little interest on these remains of a

Scotch formation now so entirely broken up, that, like those ruined cities

of the East which exist but as mere lines of wrought material barring the

face of the desert, there has not "been left one stone of it upon

another;" but of which the fragments, though widely scattered, bear

imprinted upon them, like the stamped bricks of Babylon, the story of its

original condition, and a record of its founders. All Mr

Longmuir's Cretaceous fossils from the hill of Dudwick are of flint,—a

substance not easily ground down by the denuding agencies.

I found several other curious fossils in Mr Longmuir's

collection. Greatly more interesting, however, than any of the

specimens which it contains, is the general fact, that it should be the

collection of a Free Church minister, sedulously attentive to the proper

duties of his office, but who has yet found time enough to render himself

an accomplished geologist; and whose week-day lectures on the science

attract crowds, who receive from them, in many instances, their first

knowledge of the strange revolutions of which our globe has been the

subject, blent with the teachings of a wholesome theology. The

present age, above all that has gone before, is peculiarly the age of

physical science; and of all the physical sciences, not excepting

astronomy itself, geology, though it be a fact worthy of notice, that not

one of our truly accomplished geologists is an infidel, is the science of

which infidelity has most largely availed itself. And as the

theologian in a metaphysical age,—when scepticism, conforming to the

character of the time, disseminated its doctrines in the form of nicely

abstract speculations,—had, in order that the enemy might be met in his

own field, to become a skilful metaphysician, he must now, in like manner,

address himself to the tangibilities of natural history and geology, if he

would avoid the danger and disgrace of having his flank turned by every

sciolist in these walks whom he may chance to encounter. It is those

identical bastions and outworks that are now attacked, which must be

now defended; not those which were attacked some eighty or a hundred

years ago. And as he who succeeds in first mixing up fresh and

curious truths, either with the objections by which religion is assailed

or the arguments by which it is defended, imparts to his cause all the

interest which naturally attaches to these truths, and leaves to his

opponent, who passes over them after him as at second hand, a subject

divested of the fire-edge of novelty, I can deem Mr Longmuir well and not

unprofessionally employed, in connecting with a sound creed the

picturesque marvels of one of the most popular of the sciences, and by

this means introducing them to his people, linked, from the first, with

right associations. According to the old fiction, the look of the

basilisk did not kill unless the creature saw before it was seen;—its mere

return glance was harmless: and there is a class of thoroughly

dangerous writers who in this respect resemble the basilisk. It is

perilous to give them a first look of the public. They are

formidable simply as the earliest popularizers of some interesting

science, or the first promulgators of some class of curious little-known

facts, with which they mix up their special contributions of error,—often

the only portion of their writings that really belongs to themselves.

Nor is it at all so easy to counteract as to confute them.

A masterly confutation of the part of their works truly their own may,

from its subject, be a very unreadable book: it can have but the

insinuated poison to deal with, unmixed with the palatable pabulum in

which the poison has been conveyed; and mere treatises on poisons, whether

moral or medical, are rarely works of a very delectable order. It

seems to be on this principle that there exists no confutation of the

"Constitution of Man" in which the ordinary reader finds amusement enough

to carry him through; whereas the work itself, full of curious

miscellaneous information, is eminently readable; and that the "Vestiges

of Creation,"—a treatise as entertaining as the "Arabian Nights,"—bids

fair, not from the amount of error which it contains, but from the amount

of fresh and interestingly-told truth with which the error is mingled, to

live and do mischief when the various solidly-scientific replies which it

has called forth are laid upon the shelf. Both the "Constitution"

and the "Vestiges" had the advantage, so essential to the basilisk, of

taking the first glance of the public on their respective subjects;

whereas their confutators have been able to render them back but mere

return glances. The only efficiently counteractive mode of

looking down the danger, in cases of this kind, is the mode adopted by Mr

Longmuir.

There was a smart frost next morning; and, for the first few

hours, my seat on the top of the Banff coach, by which I travelled across

the country to where the Gamrie and Banff roads part company, was

considerably more cool than agreeable. But the keen morning improved

into a brilliant day, with an atmosphere transparent as if there had been

no atmosphere at all, through which the distant objects looked out; sharp

of outline, and in as well-defined light and shadow, as if they had

occupied the background, not of a Scotch, but of an Italian landscape.

A few speck-like sails, far away on the intensely blue sea, which opened

upon us in a stretch of many leagues, as we surmounted the moory ridge

over Macduff, gleamed to the sun with a radiance bright as that of the

sparks of a furnace blown to a white heat. The land, uneven of

surface, and open, and abutting in bold promontories on the frith, still

bore the sunny hue of harvest, and seemed as if stippled over with shocks

from the ridgy hill summits, to where ranges of giddy cliffs flung their

shadows across the beach. I struck off for Gamrie by a path that

runs eastward, nearly parallel to the shore,—which at one or two points it

overlooks from dark-coloured cliffs of grauwacke slate,—to the fishing

village of Gardenstone. My dress was the usual fatigue suit of

russet, in which I find I can work amid the soil of ravines and quarries

with not only the best effect, but with even the least possible sacrifice

of appearance: the shabbiest of all suits is a good suit spoiled. My

hammer-shaft projected from my pocket; a knapsack, with a few changes of

linen, slung suspended from my shoulders; a strong cotton umbrella

occupied my better band; and a gray maud, buckled shepherd-fashion aslant

the chest, completed my equipment. There were few travellers on the

road, which forked off on the hill-side a short mile away, into two

branches, like a huge letter Y, leaving me uncertain which branch to

choose; and I made up my mind to have the point settled by a woman of

middle age, marked by a hard, manly countenance, who was coming up towards

me, bound apparently for the Banff or Macduff market, and stooping under a

load of dairy produce. She too, apparently, had her purpose to serve

or point to settle; for as we met, she was the first to stand; and,

sharply scanning my appearance and aspect at a glance, she abruptly

addressed me. "Honest man," she said, "do you see yon house wi' the

chimla?" "That house with the farm-steadings and stacks beside it?"

I replied. "Yes." "Then I'd be obleeged if ye wald just stap

in as ye'r gaing east the gate, and tell our folk that the stirk has gat

fra her tether, an' 'ill brak on the wat clover. Tell them to sen'

for her that minute." I undertook the commission; and, passing the

endangered stirk, that seemed luxuriating, undisturbed by any presentiment

of impending peril, amid the rich swathe of a late clover crop, still damp

with the dews of the morning frost, I tapped at the door of the

farm-house, and delivered my message to a young good-looking girl, in

nearly the words of the woman: "The gudewife bade me tell them," I said,

"to send that instant for the stirk, for she had gat fra her tether, and

would brak on the wat clover." The girl blushed just a very little,

and thanked me; and then, after obliging me, in turn, by laying down for

me my proper route,—for I had left the question of the forked road to be

determined at the farm-house,—she set off at high speed, to rescue the

unconscious stirk. A walk of rather less than two hours brought me

abreast of the Bay of Gamrie,—a picturesque indentation of the coast, in

the formation of which the agency of the old denuding forces, operating on

deposits of unequal solidity, may be distinctly traced. The

surrounding country is composed chiefly of Silurian schists, in which

there is deeply inlaid a detached strip of mouldering Old Red Sandstone,

considerably more than twenty miles in length, and that varies from two to

three miles in breadth. It seems to have been let down into the more

ancient formation,—like the keystone of a bridge into the ringstones of

the arch when the work is in the act of being completed,—during some of

those terrible convulsions which cracked and rent the earth's crust, as if

it had been an earthen pipkin brought to a red heat and then plunged into

cold water. Its consequent occurrence in a lower tier of the

geological edifice than that to which it originally belonged has saved it

from the great denudation which has swept from the surface of the

surrounding country the tier composed of its contemporary beds and strata,

and laid bare the grauwacke on which this upper tier rested. But

where it presents its narrow end to the sea, as the older houses in our

more ancient Scottish villages present their gables to the street, the

waves of the German Ocean, by incessantly charging against it, propelled

by the tempests of the stormy north, have hollowed it into the Bay of

Gamrie, and left the more solid grauwacke standing out in bold

promontories on either side, as the headlands of Gamrie and Troup.

In passing downwards on the fishing village of Gardenstone,

mainly in the hope of procuring a guide to the ichthyolite beds, I saw a

labourer at work with a pick-axe, in a little craggy ravine, about a

hundred yards to the left of the path, and two gentlemen standing beside

him. I paused for a moment, to ascertain whether the latter were not

brother workers in the geologic field. "Hilloa!—here,"—shouted out

the stouter of the two gentlemen, as if, by some clairvoyant

faculty, he had dived into my secret thought; "come here." I went

down into the ravine, and found the labourer engaged in disinterring

ichthyolitic nodules out of a bed of gray stratified clay, identical in

its composition with that of the Cromarty fish-beds; and a heap of

freshly-broken nodules, speckled with the organic remains of the Lower Old

Red Sandstone,—chiefly occipital plates and scales,—lay beside him.

"Know you aught of these? said the stouter gentleman, pointing to the

heap. "A little," I replied; "but your specimens are none of the

finest. Here, however, is a dorsal plate of Coccosteus; and here a

scattered group of scales of Osteolepis; and here the occipital plates of

Cheirolepis Cummingiœ; and here the spine of the anterior dorsal of

Diplacanthus Striatus." My reading of the fossils was at once

recognised, like the mystic sign of the freemason, as establishing for me

a place among the geologic brotherhood; and the stout gentleman producing

a spirit-flask and a glass, I pledged him and his companion in a bumper.

"Was I not sure?" he said, addressing his friend: "I knew by the cut of

his jib, notwithstanding his shepherd's plaid, that he was a wanderer of

the scientific cast." We discussed the peculiarities of the deposit,

which, in its mineralogical character, and generically in that of its

organic contents, resembles, I found, the fish-beds of Cromarty (though,

curiously enough, the intervening contemporary deposits of Moray and the

western parts of Banffshire differ widely, in at least their chemistry,

from both); and we were right good friends ere we parted. To men who

travel for amusement, incident is incident, however trivial in itself, and

always worth something. I showed the younger of the two geologists

my mode of breaking open an ichthyolitic nodule, so as to secure the best

possible section of the fish. "Ah," he said, as he marked a style of

handling the hammer which, save for the fifteen years' previous practice

of the operative mason, would be perhaps less complete,—"Ah, you must have

broken open a great many." His own knowledge of the formation and

its ichthyolites had been chiefly derived, he added, from a certain little

treatise on the "Old Red Sandstone," rather popular than scientific, which

he named. I of course claimed no acquaintance with the work; and the

conversation went on. The ill luck of my new friends, who had been

toiling among the nodules for hours without finding an ichthyolite worth

transferring to their bag, showed me that, without excavating more deeply

than my time allowed, I had no chance of finding good specimens.

But, well content to have ascertained that the ichthyolite bed of Gamrie

is identical in its Composition, and, generically at least, in its

organisms, with the beds with which I was best acquainted, I rose to come

away. The object which I next proposed to myself was, to determine

whether, as at Eathie and Cromarty, the fossils here appear not only on

the hill-side, but also crop out along the shore. On taking leave,

however, of the geologists, I was reminded by the younger of what I might

have otherwise forgotten,—a raised beach in the immediate neighbourhood

(first described by Mr Prestwich, in his paper on the Gamrie

ichthyolites), which contains shells of the existing species at a higher

level than elsewhere,—so far as is yet known,—on the east coast of

Scotland. And, kindly conducting me till he had brought me full

within view of it, we parted. The ichthyolites which I had just been

laying open occur on the verge of that Strathbogie district in which the

Church controversy raged so hot and high; and by a common enough trick of

the associative faculty, they now recalled to my mind a stanza which

memory had somehow caught when the battle was at the fiercest. It

formed part of a satiric address, published in an Aberdeen newspaper, to

the not very respectable non-intrusionists who had smoked tobacco and

drank whisky in the parish church at Culsalmond, on the day of a certain

forced settlement there, specially recorded by the clerks of the

Justiciary Court.

|

Tobacco and whisky cost siller,

And meal is but scanty at hame;

But gang to the stace-mason M——r,

Wi' Old Red Sandstone fish he'll fill your wame. |

Rather a dislocated line that last, I thought, and too much in the style

in which Zachary Boyd sings "Pharaoh and the Pascal." And as it is

wrong to leave the beast of even an enemy in the ditch, however long its

ears, I must just try and set it on its legs. Would it not run

better thus?

|

"Tobacco and whisky cost siller,

An' meal is but scanty at hame;

But gang to the stane-mason M——r,"

He'll pang wi' ichth'ólites your wame,—

Wi' fish! ! as Agassiz has ca'd'em,

In Greek, like themsel's, hard an' odd,

That were baked in stane pies afore Adam

Gaed names to the haddocks and cod. |

Bad enough as rhyme, I suspect; but conclusive as evidence to prove that

the animal spirits, under the influence of the bracing walk, the fine day,

and the agreeable rencounter at the fish-beds,—not forgetting the

half-gill bumper,—had mounted very considerably above their ordinary level

at the editorial desk.

The raised beach may be found on the slopes of a

grass-covered eminence, once the site of an ancient hill-fort, and which

still exhibits, along the rim-like edge of the flat area atop, scattered

fragments of the vitrified walls. A general covering of turf

restricted my examination of the shells to one point, where a landslip on

a small scale had laid the deposit bare; but I at least saw enough to

convince me that the debris of the shell-fish used of old as food by the

garrison had not been mistaken for the remains of a raised beach,—a

mistake which in other localities has occurred, I have reason to believe,

oftener than once. The shells, some of them exceedingly minute, and

not of edible species, occur in layers in a siliceous stratified sand,

overlaid by a bed of bluish-coloured silt. I picked out of the sand

two entire specimens of a full-grown Fusus, little more than half an inch

in length, —the Fusus turricola; and the greater number of the

fragments that lay bleaching at the foot of the broken slope in a state of

chalky friability, seemed to be fragments of those smaller bivalves,

belonging to the genera Donax, Venus, and Mactra, that are

so common on flat sandy shores. But when the sea washed over these

shells, they could have been the denizens of at least no flat

shore. The descent on which they occur sinks downwards to the

existing beach, over which, it is elevated at this point two hundred and

thirty feet, at an angle with the horizon of from thirty-five to forty

degrees. Were the land to be now submerged to where they appear on

the hill-side, the bay of Gamrie, as abrupt in its slopes as the upper

part of Loch Lomond or the sides of Loch Ness, would possess a depth of

forty fathoms water at little more than a hundred yards from the shore.

I may add, that I could trace at this height no marks of such a continuous

terrace around the sides of the bay as the waves would have infallibly

excavated in the diluvium, had the sea stood at a level so high, or,

according to the more prevalent view, had the land stood at a level so

low, for any considerable time; though the green banks which sweep around

the upper part of the inflection, unscarred by the defacing plough, would

scarce have failed to retain some mark of where the surges had broken, had

the surges been long there. Whatever may in this special case be the

fact, however, I cannot doubt that in the comparatively modern period of

the boulder clays, Scotland lay buried under water to a depth at least

five times as great as the space between this ancient sea-beach and the

existing tide-line.

CHAPTER II.

I LINGERED on the hill-side considerably longer than

I ought; and then, hurrying downwards to the beach, passed eastwards under

a range of abrupt, mouldering precipices of red sandstone, to the village.

From the lie of the strata, which, instead of inclining coastwise, dip

towards the interior of the country, and present in the descent seawards

the outcrop of lower and yet lower deposits of the formation, I found it

would be in vain to look for the ichthyolite beds along the shore.

They may possibly be found, however, though I lacked time to ascertain the

fact, along the sides of a deep ravine, which occurs near an old

ecclesiastical edifice of gray stone, perched, nest-like, half-way up the

bank, on a green hummock that overlooks the sea. The rocks, laid

bare by the tide, belong to the bed of coarse-grained red sandstone,

varying from eighty to a hundred and fifty feet in thickness, which lies

between the lower fish-bed and the great conglomerate, and which, in not a

few of its strata, passes itself into a species of conglomerate, different

only from that which it overlies, in being more finely comminuted.

The continuity of this bed, like that of the deposit on which it rests, is

very remarkable. I have found it occurring at many various points,

over an area at least ten thousand square miles in extent, and bearing

always the same well-marked character of a more thoroughly ground-down

conglomerate than the great conglomerate on which it reposes. The

underlying bed is composed of broken fragments of the rocks below,

crushed, as if by some imperfect rudimentary process, like that which in a

mill merely breaks the grain; whereas, in the bed above, a portion of the

previously-crushed materials seems to have been subjected to some further

attritive process, like that through which, in the mill, the broken grain

is ground down into meal or flour.

As I passed onwards, I saw, amid a heap of drift-weed

stranded high on the beach by the previous tide, a defunct father-lasher,

with the two defensive spines which project from its opercles stuck fast

into little cubes of cork, that had floated its head above water, as the

tyro-swimmer floats himself upon bladders; and my previous acquaintance

with the habits of a fishing village enabled me at once to determine why

and how it had perished. Though almost never used as food on the

eastern coast of Scotland, it had been inconsiderate enough to take the

fisherman's bait, as if it had been worthy of being eaten; and he had

avenged himself for the trouble it had cost him, by mounting it on cork,

and sending it off, to wander between wind and water, like the Flying

Dutchman, until it died. Was there ever on earth a creature save man

that could have played a fellow-mortal a trick at once so ingeniously and

gratuitously cruel? Or what would be the proper inference, were I to

find one of the many-thorned ichthyolites of the Lower Old Red Sandstone

with the spines of its pectorals similarly fixed on cubes of lignite?—that

there had existed in these early ages not merely physical death, but also

moral evil; and that the being who perpetrated the evil could not only

inflict it simply for the sake of the pleasure he found in it, and without

prospect of advantage to himself, but also by so adroitly reversing,

fiend-like, the purposes of the benevolent Designer, that the weapons

given for the defence of a poor harmless creature should be converted into

the instruments of its destruction. It was not without meaning that

it was forbidden by the law of Moses to seethe a kid in its mother's milk.

A steep bulwark in front, against which the tide lashes twice

every twenty-four hours,—an abrupt hill behind,—a few rows of squalid

cottages built of red sandstone, much wasted by the keen sea-winds,—a

wilderness of dunghills and ruinous pig-sties,—women seated at the doors,

employed in baiting lines or mending nets,—groups of men lounging lazily

at some gable-end fronting the sea,—herds of ragged children playing in

the lanes,—such are the components of the fishing village of Gardenstone.

From the identity of name, I had associated the place with that Lord

Gardenstone of the Court of Session who published, late in the last

century, a volume of "Miscellanies in Prose and Verse," containing, among

other clever things, a series of tart criticisms on English plays,

transcribed, it was stated in the preface, from the margins and fly-leaves

of the books of a "small library kept open by his Lordship" for the

amusement of travellers at the inn of some village in his immediate

neighbourhood; and taking it for granted, somehow, that Gardenstone was

the village, I was looking around me for the inn, in the hope that where

his Lordship had opened a library I might find a dinner. But failing

to discern it, I addressed myself on the subject to an elderly man in a

pack-sheet apron, who stood all alone, looking out upon the sea, like

Napoleon; in the print, from a projection of the bulwark. He turned

round, and showed, by an unmistakeable expression of eye and feature, that

he was what the servant girl in "Guy Mannering" characterizes as "very

particularly drunk,"—not stupidly, but happily, funnily, conceitedly

drunk, and full of all manner of high thoughts of himself. "It'll be

an awfu' coorse nicht," he said, "fra the sea." "Very likely," I

replied, reiterating my query in a form that indicated some little

confidence of receiving the needed information; " I daresay you could

point me out the public-house here?" "Aweel I wat, that I can; but

what's that?" pointing to the straps of my knapsack; "are ye a sodger on

the Queen's account, or ye'r ain?" "On my own, to be sure; but have

ye a public-house here?" "Ay, twa; ye'll be a traveller?" "O

yes, great traveller, and very hungry: have I passed the best public

house?" "Ay; and ye'll hae come a gude stap the day?" A woman

came up, with spectacles on nose, and a piece of white seam-work in her

hand; and, cutting short the dialogue by addressing myself to her, she at

once directed me to the public-house. "Hoot, gudewife," I heard the

man say, as I turned down the street, "we suld ha'e gotten mair oot o'

him. He's a great traveller yon, an' has a gude Scots tongue in his

head."

Travellers, save when, during the herring season, an

occasional fish-curer comes the way, rarely bait at the Gardenstone inn;

and in the little low-browed room, with its windows in the thatch, into

which, as her best, the landlady ushered me, I certainly found nothing to

identify the locale with that chosen by the literary lawyer for his open

library. But, according to Ferguson, though "learning was scant,

provision was good;" and I dined sumptuously on an immense platter of

fried flounders. There was a little bit of cold pork added to the

fare; but, aware from previous experience of the pisciverous habits of the

swine of a fishing village, I did what I knew the defunct pig must have

very frequently done before me,—satisfied a keenly-whetted appetite on

fish exclusively. I need hardly remind the reader that Lord

Gardenstone's inn was not that of Gardenstone, but that of Laurencekirk,—the

thriving village which it was the special ambition of this law-lord of the

last century to create; and which, did it produce only its famed snuff

boxes, with the invisible hinges would be rather a more valuable boon to

the country than that secured to it by those law-lords of our own days,

who at one fell blow disestablished the national religion of Scotland, and

broke off the only handle by which their friends the politicians could

hope to manage the country's old vigorous Presbyterianism.

Meanwhile it was becoming apparent that the man with the apron had as

shrewdly anticipated the character of the coming night as if he had been

soberer. The sun, ere its setting, disappeared in a thick leaden

haze, which enveloped the whole heavens; and twilight seemed posting on to

night a full hour before its time. I settled a very moderate bill,

and set off under the cliffs at a round pace, in the hope of scaling the

hill, and gaining the high road atop which leads to Macduff, ere the

darkness closed. I had, however, miscalculated my distance; I,

besides, lost some little time in the opening of the deep ravine to which

I have already referred as that in which possibly the fish-beds may be

found cropping out; and I had got but a little beyond the gray

ecclesiastical ruin, with its lonely burying-ground, when the tempest

broke and the night fell.

One of the last objects which I saw, as I turned to take a

farewell look of the bay of Gamrie, was the magnificent promontory of

Troup Head, outlined in black on a ground of deep gray, with its two

terminal stacks standing apart in the sea. And straightway, through

one of those tricks of association so powerful in raising, as if from the

dead, buried memories of things of which the mind has been oblivious for

years, there started up in recollection the details of an ancient

ghost-story, of which I had not thought before for perhaps a quarter of a

century. It had been touched, I suppose, in its obscure, unnoted

corner, as Ithuriel touched the toad, by the apparition of the insulated

stacks of Troup, seen dimly in the thickening twilight over the solitary

burying-ground. For it so chances that one of the main incidents of

the story bears reference to an insulated sea-stack; and it is connected

altogether, though I cannot fix its special locality, with this part of

the coast. The story had been long in my mother's family, into which

it had been originally brought by a great-grandfather of the writer, who

quitted some of the seaport villages of Banffshire for the northern side

of the Moray Frith, about the year 1718; and, when pushing on in the

darkness, straining, as I best could, to maintain a sorely-tried umbrella

against the capricious struggles of the tempest, that now tatooed

furiously upon its back as if it were a kettle-drum, and now got

underneath its stout ribs, and threatened to send it up aloft like a

balloon, and anon twisted it from side to side, and strove to turn it

inside out like a Kilmarnock nightcap,—I employed myself in arranging in

my mind the details of the narrative, as they had been communicated to me

half an age before by a female relative.

The opening of the story, though it existed long ere the

times of Sir Walter Scott or the Waverley novels, bears some resemblance

to the opening, in the "Monastery," of the story of the White Lady of

Avenel. The wife of a Banffshire proprietor of the minor class had

been about six months dead, when one of her husband's ploughmen, returning

on horseback from the smithy, in the twilight of an autumn evening, was

accosted, on the banks of a small stream, by a stranger lady, tall and

slim, and wholly attired in green, with her face wrapped up in the hood of

her mantle, who requested to be taken up behind him on the horse, and

carried across. There was something in the tones of her voice that

seemed to thrill through his very bones, and to insinuate itself, in the

form of a chill fluid, between his skull and the scalp. The request,

too, appeared a strange one; for the rivulet was small and low, and could

present no serious bar to the progress of the most timid traveller.

But the man, unwilling ungallantly to offend a lady, turned his horse to

the bank, and she sprang up lightly behind him. She was, however, a

personage that could be better seen than felt: she came in contact with

the ploughman's back, he said, as if she had been an ill-filled sack of

wool; and when, on reaching the opposite side of the streamlet, she leaped

down as lightly as she had mounted, and he turned fearfully round to catch

a second glimpse of her, it was in the conviction that she was a creature

considerably less earthly in her texture than himself. She had

opened, with two pale, thin arms, the enveloping hood, exhibiting a face

equally pale and thin, which seemed marked, however, by the roguish,

half-humorous expression of one who had just succeeded in playing off a

good joke. "My dead mistress! !" exclaimed the ploughman.

"Yes, John, your mistress," replied the ghost. "But ride

home, my bonny man, for it's growing late: you and I will be better

acquainted ere long." John accordingly rode home, and told his

story.

Next evening, about the same hour, as two of the laird's

servant-maids were engaged in washing in an out-house, there came a slight

tap to the door. "Come in," said one of the maids; and the lady

entered, dressed, as on the previous night, in green. She swept past

them to the inner part of the washing-room; and, seating herself on a low

bench, from which, ere her death, she used occasionally to superintend

their employment, she began to question them, as if still in the body,

about the progress of their work. The girls, however, were greatly

too frightened to make any reply. She then visited an old woman who

had nursed the laird, and to whom she used to show, ere her departure,

greatly more kindness than her husband. And she now seemed as much