|

THE following sonnet, addressed by Walter Savage Landor

to Robert Browning, blends the just judgment of the critic with the

tender admiration of the friend:—

|

There is delight in singing, though none hear

Beside the singer: and there is delight

In praising, though the praiser sit alone

And see the praised far off him, far above.

Shakespeare is not our poet, but the world's,

Therefore on him no speech! and brief for thee, Browning!

Since Chaucer was alive and hale,

No man hath walkt along our roads with step

So active, so inquiring eye, or tongue

So varied in discourse. But warmer climes

Give brighter plumage, stronger wing: the breeze

Of Alpine heights thou playest with, borne on

Beyond Sorreuto and Amalfi, where

The Siren waits thee, singing song for song. |

A little piece of Browning's, entitled "Home Thoughts, from Abroad,"

shows how this stout traveller along the common roads of England

remembered, far away in Italy, what he saw and heard at home:—

|

O, to be in England

Now that April's there,

And whoever wakes in England

Sees, some morning, unaware,

That the lowest boughs and the brush-wood sheaf

Round the elm-tree bole are in tiny leaf,

while the chaffinch sings on the orchard bough

In England—now!

And after April, when May follows,

And the white-throat builds, and all the swallows,—

Hark! where my blossomed pear-tree in the hedge

Leans to the field, and scatters on the clover

Blossoms and dewdrops,—at the bent spray's edge,—

That's the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over,

Lest you should think he never could recapture

The first fine careless rapture!

And though the fields look rough with hoary dew,

All will be gay when noontide wakes anew

The buttercups, the little children's dower,

- Far brighter than this gaudy melon-flower! |

|

|

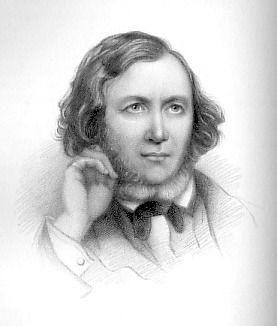

Robert Browning

(1812-89) |

Mr. Browning was born in Camberwell, a suburb of London, in the year 1812.

His father was a Dissenter, and he received his collegiate education at the London University, after which, at the age of about twenty, he visited Italy.

Here, first and last, he has spent many years, and a large number of his poems are inspired by Italian scenes and legends.

They show that his inquiring eye and active step have been busy, not only in the libraries and closets of that storied land, but along the highways and by-paths and among the common people of the country.

His first published work was "Paracelsus," which appeared in 1835.

It is a dramatic poem, of a strikingly original character, of the class to which belong Prometheus, Faust, Festus, and other works, in which poets of all ages have sought to penetrate the mysteries of existence and of human destiny.

The Paracelsus of history, who is physician, alchemist, quack, juggler, drunkard, and the father of modern chemistry, appears in this poem as a high and sovereign intellect aspiring after the secrets of the world, yet dying disappointed and heart-broken, having forfeited success by seeking to transcend the necessities and limitations of humanity, instead of patiently working within them.

This poem drew towards Mr. Browning the immediate attention of the critics, ever on the look-out for the coming great poet.

On the whole, they received Paracelsus kindly, and the most thoughtful men in England and America have agreed that it contains much fine poetry, as well as nice metaphysical thought.

In 1837 Mr. Browning published "Strafford," a purely English tragedy, which, although placed upon the stage by Mr. Macready, who represented the principal character, did not meet with great success.

Three years afterwards appeared "Sordello," another dramatic poem, upon which various opinions have been pronounced.

Most of the current criticism of the time is written in a hurry, and "Sordello" was not to be digested or even read in a day.

It was rough, tangled, and to a large degree unintelligible to most readers.

Some students of poetry who had leisure and a taste for occult mysteries tried their hands at it, and came to the conclusion that it had a great deal of meaning and many beautiful passages.

But the early judgment has not been reversed during the twenty years which have elapsed since the poem was given to the world.

Perhaps the best description of it is that given by an American critic, who says it was a fine poem before the author wrote it.

If Mr. Browning had stopped here, the world would not have recognized him, as it now does, as one of the greatest dramatic poets since Shakespeare's day.

He kept on writing, and between 1842 and 1846 produced, under the title of "Bells and Pomegranates," a series of dramas and lyrics, or dramatic poems, for the lyrics are as dramatic, almost, as the dramas, upon which his fame thus far chiefly rests.

The dramas are entitled "Pippa Passes," "King Victor and King Charles," "Colombe's Birthday," "A Blot in the 'Scutcheon," "The Return of the Druses," "Luria," and "A Soul's Tragedy."

In these poems, Mr. Browning displays that depth, clearness, minuteness, and universality of vision, that power of revealing the object of his thought without revealing himself, that force of imagination which "turns the common dust of servile opportunity to gold," and that

humour which sees remote and fanciful resemblances and develops their secret relationship to each other, which constitute the true poet and the great dramatist.

The "Blot in the 'Scutcheon " is a piteous tragedy. It was produced at Drury Lane in 1843, but its success was moderate.

This proves only that the applause of the pit is not the test of dramatic merit, for it is almost a perfect work. "Pippa Passes" is also a charming poem.

In it occurs the following remarkable figure, startling as the lightning itself.

|

OTTIMA (to her paramour).

Buried in woods we lay, you recollect;

Swift ran the searching tempest overhead;

And ever and anon some bright white shaft

Burnt through the pine-tree roof,—here burnt and there,

As if God's messenger through the close wood screen

Plunged and replunged his weapon at a venture,

Feeling for guilty thee and me.

|

Some of the lyrics and romances included in this collection of poems have passed into the school-books and standard collections of poetry; for instance, "The Pied Piper of Hamelin," "How they brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix," and "The Lost Leader;" while others, among which may be mentioned the "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister" and "Sibrandus Schafnaburgensis,"

display a quaintness of humour which makes them exceedingly pleasant

reading. The following little piece shows with what quick and

rapid strokes Mr. Browning can place a vivid natural picture and a bit

of personal experience before the eye of the reader:—

|

MEETING AT NIGHT.

I.

The gray sea and the long, black land;

And the yellow half-moon, large and low;

And the startled little waves that leap

In fiery ringlets from their sleep,

As I gain the cove with pushing prow

And quench its speed in the slushy sand.

II.

Then a mile of warm sea-scented beach;

Three fields to cross till a farm appears;

A tap at the pane, the quick sharp scratch,

And blue spurt of a lighted match,

And a voice less loud, through its joys and fears,

Than the two hearts beating each to each! |

In 1850 Mr. Browning published a poem in two parts, entitled "Christmas Eve and Easter Day."

It deals with theological problems, and expresses some phases of the author's spiritual experience with great force and vividness.

It also furnishes a remarkable instance of the ease with which Mr. Browning puts into melodious verse the elaborate niceties of a metaphysical argument, diversifying it with picturesque and humorous descriptions.

Some of the pictures of country people and rural life are as faithful and minute as those of Crabbe.

And here is a sketch of a Göttingen Rationalist Professor, which

exhibits the same fidelity and accuracy of detail, with a touch of the

author's peculiar humour:—

|

But hist!—a buzzing and emotion!

All settle themselves, the while ascends

By the creaking rail to the lecture desk,

Step by step, deliberate

Because of his cranium's overweight,

Three parts sublime to one grotesque,

If I have proved an accurate guesser,

The hawk-nosed, high-cheek-boned Professor.

I felt at once as if there ran

A shoot of love from my heart to the man,—

That sallow, virgin-minded, studious

Martyr to mild enthusiasm,

As he uttered a kind of cough-preludious

That woke my sympathetic spasm,

(Beside some spitting that made me sorry,)

And stood, surveying his auditory,

With a wan, pure look, well-nigh celestial.—

—Those blue eyes had survived so much!

While, under the foot they could not smutch,

Lay all the fleshly and the bestial.

Over he bowed, and arranged his notes,

Till the auditory's clearing of throats

Was done with, died into a silence;

And, when each glance was upward sent,

Each bearded month composed intent,

And a pin might be heard drop half a mile hence,—

He pushed back higher his spectacles,

Let the eyes stream out like lamps from cells,

And giving his head of hair—a hake

Of undressed tow, for colour and quantity—

One rapid and impatient shake,

As our own young England adjusts a jaunty tie,

(When about to impart, on mature digestion,

Same thrilling view of the surplus question,)

—The Professor's grave voice, sweet though hoarse,

Broke into his Christmas-eve's discourse. |

Mr. Browning's latest work is entitled "Men and Women." It is a

collection of fifty poems, which display all the rich and various

qualities of his genius. We quote one of the most pleasing of the

poems in this volume:—

|

EVELYN HOPE. I. Beautiful Evelyn Hope is dead!

Sit and watch by her side an hour;

That is her book-shelf, this her bed;

She plucked that piece of geranium-flower,

Beginning to die too in the glass.

Little has yet been changed, I think,—

The shutters are shut, no light may pass

Save two long rays through the hinge's chink.

II.

Sixteen years old when she died!

Perhaps she had scarcely heard my name,—

It was not her time to love: beside,

Her life had many a hope and aim,

Duties enough and little cares,

And now was quiet, now astir,—

Till God's hand beckoned unawares,

And the sweet white brow is all of her.

III.

Is it too late then, Evelyn Hope?

What, your soul was pure and true,

The good stars met in your horoscope,

Made you of spirit, fire, and dew,—

And just because I was thrice as old,

And our paths in the world diverged so

wide,

Each was naught to each, must I be told?

We were fellow-mortals, naught beside?

IV.

No, indeed! for God above

Is great to grant, as mighty to make,

And creates the love to reward the love,—

I claim you still, for my own love's sake!

Delayed it may be for more lives yet,

Through worlds I shall traverse, not a few,—

Much is to learn and much to forget

Ere the time be come for taking you.

V.

But the time will come,—at last it will,—

When, Evelyn Hope, what meant, I shall say,

In the lower earth, in the years long still,

That body and soul so pure and gay?

Why your hair was amber, I shall divine,

And your mouth of your own geranium's red,—

And what you would do with me, in fine,

In the new life come in the old one's stead.

VI.

I have lived, I shall say, so much since then;

Given up myself so many times,

Gained me the gains of various men,

Ransacked the ages, spoiled the climes;

Yet one thing, one, in my soul's full scope,

Either I missed, or itself missed me,—

And I want and find you, Evelyn Hope!

What is the issue? let us see!

VII.

I loved you, Evelyn, all the while;

My heart seemed full as it could hold,—

There was place and to spare for the frank, young

smile,

And the red young mouth, and the hair's young

gold.

So, hush,—I will give you this leaf to keep,—

See, I shut it inside the sweet cold hand.

There, that is our secret! go to sleep;

You will wake, and remember, and understand. |

The last piece in "Men and Women" is a beautiful love poem addressed to E. B. B., the poet's wife.

In November, 1846, Mr. Browning was married to Elizabeth Barrett, of whom a biographical sketch is included in this volume.

Since their marriage, Mr. and Mrs. Browning have generally resided at Casa Guidi in Florence, but they occasionally pass a winter in Rome.

Mr. George S. Hillard, an American author, says: "A happier home and a more perfect union than theirs it is not easy to imagine; and this completeness arises, not only from the rare qualities which each possesses, but from their adaptation to each other.

It is a privilege to know such beings, singly and separately, but to see their powers quickened, and their happiness rounded by the sacred tie of marriage, is a cause for peculiar and lasting gratitude.

A union so complete as theirs—in which the mind has nothing to crave nor the heart to sigh for—is cordial to behold and soothing to

remember."

Mr. Browning's thoughtful lines on the perishableness

of fame may sadden the minds of ambitious poets:—

|

See, as the prettiest graves will do in time,

Our poet's wants the freshness of its prime;

Spite of the sexton's browsing horse, the sods

Have struggled through its binding osier-rods;

Headstone and half-sunk footstone lean awry,

Wanting the brick-work promised by and by;

How the minute gray lichens, plate o'er plate,

Have softened down the crisp-cut name and date! |

Forty years ago, Mr. Jeffrey uttered a lament over the forgotten poets; forgotten merely because there was not room in men's memories for them.

He consoled himself with the reflection that Campbell and Byron and Scott and Crabbe and Southey, and the other poets of his day, might live, in unequal proportions, in some new collections of specimens. But the posterity of 1820, sometimes correcting his estimate, as in the case of Wordsworth, seems still to enjoy complete editions of the works of the great masters of the art of poetry, as well as ever.

And we are confident that Mr. Browning's dramas and lyrics will long continue to find appreciative readers, and that, as culture and taste and love of pure art make progress, the number of his constant admirers will steadily increase.

If we are mistaken, he must be consoled with the phrase from Milton which is expected to soothe all great and unpopular poets; for he may safely rely till the end of time upon his "fit audience, though few." ___________________

Note: see also.......

[1.] Gerald Massey

on 'The Poems and Plays of Robert Browning.'

[2.] 'Robert

Browning's Poems;' an article (attr. J. C. Hotten) published in The

Edinburgh Review, October 1864.

[3.] 'Robert

Browning's Poems and The Edinburgh Review;' Gerald

Massey's letter to the Editor of The READER in response to [2.]

above.

[4.] Gerald

Massey on 'Dramatis Personae': the Athenæum, June

1864.

[5.] Gerald Massey

on 'The Poems and Other Works

of Mrs Browning.' |