|

[Back

to Chapter 3]

PART 2

QUEST

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 4

PRIVATION

[1856-1863] |

|

Poverty is a never ceasing struggle for

the means of living and is a cold place to write poetry in.

(Massey) |

|

|

The difficulties with which Massey had to contend since his move to

Edinburgh continued with two serious disappointments between the latter

part of 1856 and early 1857. Due to increasing competition between

the Edinburgh newspapers, the proprietor of the Edinburgh News

was forced to reduce his expenses, and Massey was made redundant.

Unable now to afford a housekeeper, he and Rosina had to do

all the work themselves. This was not helped by Rosina taking to

her bed at times, due to acute depression. Again the Stirlings

helped by providing coal for heating and some clothing for Christabel,

then aged 5 yrs.

12 Henderson Road

Thursday

Dear Mrs Stirling.

I send you one Pound, out of the first money I have received, toward

repaying the two Pounds you were good enough to lend me for my Rent.

The other I hope to send in a day or two. I would have called on

you but for some time past have scarcely left the house for various

reasons. One has been that I and Mrs. Massey have done the

housework between us for the last two months and Mrs. Massey has been

quite laid up in bed during the last week, so that I have had all the

work to do.

If it was you, as we suspect it was, who sent us half a Ton of Coal

recently, we do not know how to thank you sufficiently, for we had none

in the house and had not had any for two days. So you may guess

they were welcome. Mrs. Massey called to try and thank you, but

you were engaged. We are indebted also to some anonymous

providence for a handsome new dress for Christabel, but do not know

whether it be you or not. If so, and if not, God bless you for all

your kindnesses.

And believe me

Yours [affectionately]

Gerald Massey

Additionally, Craigcrook Castle,

on which he had placed so much hope and hurried to complete, had been

published in October, dedicated to William Stirling. Early sales

of the book went quite well, prompting a second revised edition which

then fell flat. Fraser's Magazine criticised his war verses

in general and accounts of battle in particular, referring especially to

the section ‘Glimpses

of the War’:[1]

Mr Massey was thinking of the jolly excitement of a rush of six

hundred horsemen with plumes waving, sabres high in the air, trumpets

blowing the charge, horses neighing, and the spectators cheering on the

gallant race. Did Mr Massey ever ride a steeple-chase, or did he ever

see one ridden? Let him ask one of the riders what he thinks ... if they

tell him that they have any thoughts to expend upon glory ... Mr Massey

has far too much talent not to perceive at once that his poem, put into

the mouth of a cavalry soldier charging at Balaklava, is a ludicrous

absurdity … We are not criticising his poem except from one point

of view—its utter falsity of representation …[2]

This was the second review, following his earlier

War Waits, that had criticised his

battle scenes. Some years later, after meeting an officer who had

taken part in the heavy cavalry charge at Balaklava, Massey recast this

previously criticised epic, and presented it in a less turgid style to

Cassell's Magazine as ‘Scarlett's

Three Hundred’.[3]

The blank verse poem ‘Craigcrook

Castle’ by itself received favourable comments—Henry Fothergill

Chorley writing in the Athenæum

cited a "richly-coloured evening picture":

|

Now Sunset burns. A sea of gold on fire

Serenely surges around purple isles:

O'er billows and flame-furrows Day goes down.

Far-watching clouds with ruby glimmer bloom … |

But this perceptive reviewer noted the haste in which Massey

had completed his book, and commented that ‘the framework in which these

things are set has been carelessly or infelicitously contrived.’[4]

In letters to William Stirling, Massey wrote acknowledging the deficits:

What you say about my being too Imagerial and wordy is alas too true.

I feel deeply all that can be urged against my verse including the hard

words in Fraser and I trust that that is one step toward amendment.

But somehow I feel much more from what my kindly Reviewers have not said

and I felt they might have said than I do from the harshness of those

who assume to set me and matters right … A Note from my Publisher by

which I am reminded that Craigcrook Castle is not the only castle

I have built in the air. Among the hopes I had formed upon its

anticipated success was the hope that I might be enabled to return you

the money you so generously lent me in my need. Many other hopes

and plans for the future must likewise fall to the ground. I had thought

that my Book might have got me out of debt and left a little to live on

while I might do something else more worthy. But altho' the sale

of the Book cannot surely be quite over, it is quite evident that it

won't redeem me, and I must look to other means. I suppose the principal

cause of this failure—i.e. compared with my wants—lies in the immature

state of the poems and the haste in which they were written and printed.

Their reception has been pretty good but I suppose the public feel

disappointed and do not care to buy. What I am to do for the

future I don't know. My peculiar domestic circumstances sadly

drain on my health and time. I am getting so little master of

either that I don't believe I can earn a living by my pen … I have

generally been pretty hopeful but I often feel that I am, and shall be,

dragged down before I can get a foothold on the world to do something

worth having lived for … We have thought of going back to London as we

have nothing to keep us here except being near Prof. Simpson … We have

lost two of our little ones here and my Wife clings to them, altho' she

thinks her health might be better in England. I feel darkly that

the next two or three years will be the most critical of all. God

help me through them.[5]

Since the American issue of ‘Babe Christabel’, Massey had

been soliciting to have his latest poems including ‘Craigcrook Castle’

incorporated into a new revised edition. The next year by

arrangement with his previous publisher, Ticknor and Fields of Boston

issued his collected works as The Poetical Works of Gerald Massey,

although the format of this did not please him, and he wrote to the

publishers:

I have received a copy of your edition of my Poems … The Book is

exquisitely got up for a popular pocket poet which I hope some day to

become. But for the life of me I can't understand why Derby's Ed.

should have been reprinted from with all its shortcomings and

imperfections when there was a fifth Ed of Babe Christabel

revised and enlarged three years ago in England. It contained

several other lyrics, and the arrangement of the poems was improved.

Then, unfortunately, you have reprinted the first Ed of Craigcrook

Castle instead of the 2nd which I sent both to Derby and you …

Many of Derby's mistakes were awful. He made 56 in printing from a

printed Copy … I used to write gossiping letters for the Tribune, but on

taking an Editorship in Edinburgh the Correspondence dropped …

[6]

During that difficult time and for the following ten years

Massey had good cause to be grateful to Hepworth Dixon. He had

been sending Dixon copies of his books for reviewing, as well as

pre-publication ‘flyers’.[7] Because of Dixon's

continued interest in him and his poetry, early in 1857 Massey had

gained a foothold in the Athenæum as a poetry reviewer, to which

he contributed fifty three reviews by the end of that first year.

This enforced reading probably gave him ideas for a series of lectures

during the coming winter. His prospectus of ten subjects at four

guineas a lecture included Pre-Raphaelitism in Poetry and Painting, The

Principle and Practice of Association, Robert Burns and Love Poetry, The

Spasmodic School and its Critics, and Leaves from the Life of the Poor.

Sydney Dobell noted these, and wrote to the Reverend J. B.

Paton:

G. M[assey] intends, this winter, to give a course of Lectures,

through England and Scotland, and has sent me his prospectus. If

you have influence with any of the Sheffield Institutions, I know you

will be glad to get him an engagement, and so have the opportunity of

making his personal acquaintance. I am anxious that he should get

as many fixtures as possible, because the profession of lecturer would

be so much more favourable to his poetical studies than that incessant

newspaper and magazine writing which now exhausts his time and brains

. . . [8]

Although hoping to travel further south during his tour, he

appears to have remained in Scotland and the north of England for that

season. On 20 November 1857, Massey wrote from his address at 12

Henderson Row, concerning a series of lectures he had arranged there and

in Sunderland:

[Envelope addressed to:

Robt. S. Watson Esq

10 Royal Arcade

Newcastle on Tyne]

12 Henderson Row

Edinburgh

20 November 1857

Dear Sir,

Much obliged for the Letters. Could you send me a Copy of the

announcement you mention? also if Mr. Maclean says anything in Friday’s

Chronicle will you be good enough to ask him, from me, for a

Copy. I have engaged those busy B's you name to give 3 lectures in

Newcastle and 3 in Sunderland for £40 the 6. I think Sunderland

may somewhat nullify the Success which they anticipate in Newcastle.

Will you remember us very kindly to your Father and Mother and Sisters

and Cousin Willie and also our primal Quaker friends who made a bit of

Sunshine for us in that particularly shady place Newcastle in its

November shroud. I send a Copy of my last Book*—corrected Edition

per same post. Mrs Massey has been very poorly since we came home

and has not been able yet to redeem her promise of writing She desires

me to convey all affectionate regards to your Sisters.

Yours faithfully

Gerald Massey

* Craigcrook Castle. Ed.

Three lectures commenced on 25 January 1858 at the Nelson

Street Lecture Room, Newcastle upon Tyne. Sir John Fife took the

chair for the first, ‘The Poetry of Hood, and Wit and Humour’.

Although the series was well received, the hall was never completely

filled:

Mr Massey has a happy knack of saying good things pleasantly, and

this talent the subject of the lecture enabled him to display to the

best advantage, and though his definitions were a little elaborated and

most of his jokes well known, the audience appeared to be delighted

…[9]

The Border Record reported one lecture given earlier to the

Galashiels Mechanics Institution on the Poetry of Tennyson, saying:

The most exciting part of the lecture was that contrasting the poetry

of Byron with the poetry of Tennyson. The one, he said, was like

‘light from heaven’, the other like ‘sparks from hell’. Continuing

in this strain for some time, and throwing his whole soul into his

anathemas against the writings of Byron, a few admirers of that poet

gave vent to their feelings in no unmistakable signs of disapprobation

…[10]

The following month was notable politically for the collapse

of Palmerston's ministry, the main cause of which was an attempt to

please his ally, Napoleon III. Napoleon had complained that a plot

to murder him had been devised in England, and ordered Palmerston to

alter the law to ensure against future conspiracies. An attempt

had indeed been made on the life of the emperor, a bomb having been

thrown under his carriage when he was returning from the opera on 14

January. The attack was credited to the work of Félice Orsini, an

Italian radical, who judged Napoleon to be a traitor in not supporting

the Italian revolutionary cause.

Unwisely, Palmerston acceded to Napoleon's demand with the

Conspiracy to Murder Bill. This caused considerable opposition,

and pressure on the government was increased following the publication

by Edward Truelove of a pamphlet written by

W. E. Adams, Tyrannicide:

is it Justifiable? Truelove was arrested and

proceedings commenced on charges of seditious libel and the incitement

of diverse people to assassinate the emperor. A committee of

defence was formed, and protest meetings held throughout the country.

On 23 February Massey was to have addressed a rally in Newcastle

presided over by Joseph Cowen, supporter of radicals who was later to

acquire the Newcastle Chronicle, but the bill had been defeated

the previous Friday and Palmerston was forced to resign. Those

present at the meeting were told by Henry Buckle that Mr Massey was very

unwell; but besides that, not having been in town for the last few days,

he had concluded that after what took place in the House of Commons on

Friday night, the meeting would not be held, and he had therefore made

other arrangements; otherwise it was his full intention to have been

present on this occasion.[11] In a letter to

the meeting Massey had written:

Allow me also to rejoice that a sufficient number of Englishmen were

found true to the national spirit to give that significant hint to

Continental despotism which was given in the House of Commons last

Friday night. I have never believed that the heart of this famous

English people was with the corrupt and bloody despotisms that only

govern a nation by piecemeal murder. Now, I wish that our country

should be on the best of terms with France. France, mind—the

people of France—the heart and intellect of France. But then, Louis

Napoleon is not France … he has had the power and prestige of an

alliance with England—he has murdered and expatriated thousands of

Frenchmen, whose only crime lay in their patriotism... It is to be hoped

that Lord Palmerston's ‘bubble of reputation’ for national spirit and

love of liberty has burst for ever …

The letter was read by Cowan, and repeatedly applauded by the

audience, who cheered most loudly at the close.[12]

The new Derby government did not press the charges against Truelove; a

return of not guilty was made prior to the trial which had been fixed

for June, and he was acquitted.

|

The French Colonel's Bill. A Broadsheet

(Newcastle City Libraries)

|

Massey was able to write only one article during 1858. ‘Poetry—The

Spasmodists’ was published in February, and showed that he

did not align himself totally with that style of poetry,

demonstrated in particular by Dobell's ‘Balder’:

A poet should be a seeker and a finder of the truth and

beauty that lie in realities around him, rather than a producer

of beauty out of the deeps of his own personality. What

constitutes spasm, but weakness trying to be strong, and

collapsing in the effort … Mr Dobell appears to select his

subject, and the point of treatment, for their remoteness from

all ordinary reality, and then to refine upon these until they

are intangible to us … We urge a return to the lasting and true

subject matter of poetry, and a firmer reliance on primal truths

… As Realists, we do not forget that it is not in the vulgarity

of common things, nor the mediocrity of average characters, nor

the familiarity of familiar affairs, nor the everydayness of

everyday lives, that the poetry consists … but those universal

powers and passions which he shares with heroes and martyrs, are

the true subjects of poetry … We must have poetry for men who

work, and think, and suffer, and whose hearts would feel faint

and their souls grow lean if they fed on such fleeting

deliciousness and confectionery trifle as the spasmodists too

frequently offer them …[13]

At the end of March, Massey concluded his series of Edinburgh

lectures at the Queen Street Hall by returning to familiar

subjects. In ‘Thomas Hood, and Wit and Humour’, Massey

expressed the view that Hood's humour was of the most ethereal

kind—neither coarse, like Swift's, nor sarcastic like

Byron's—his wit being anchored fast in humanity. The

Scotsman on the 24 March 1858 reported that the lecture

was received by a large audience who frequently applauded and

gave a hearty vote of thanks at the conclusion. The

Scotsman followed with a report on the 27 March of Massey's

‘The Poetry of Alfred Tennyson’, which Massey greatly admired.

His views on the Laureate’s verse—they met once—are interesting

…

On Thursday evening [25th], Mr Gerald Massey gave the last of

his series of lectures in Queen Street Hall [Edinburgh], the

subject being ‘The Poetry of Alfred Tennyson.’ Lord Murray

presided.

Mr Massey, by way of introduction, glanced

at the two divisions of Poetry—the objective and the subjective.

Tennyson came under the subjective class. By beginning his

poetry with minute and careful particularising—not like those

who broadly handled the brush and produced effects not to be

desired—his reputation was slowly and securely built.

Many people pretended to view his poetry unfavourably—they

thought it was vague, involved and meaningless. However,

Tennyson never "moved with aimless feet." His verse was

pregnant with meaning, and though at times subtle and obscure at

first sight, this vagueness occurred only when the poet reached

one of those eternal truths which, like a cut diamond, might be

six-sided, and present as many meanings. The stream of his

speech might be deep—perhaps unfathomable to many—but it was

never muddy, except through the splashings and founderings of

the reader. The great function of the poet was to give

expression to the beautiful; and surely, he did well who

translated a page of that language.

Tennyson's poetry was a world of beauty—not a world like

Wordsworth's with the look of eternity in its aspect; not like

Shelly's, so fantastic, so aspiring in its forms; not like

Keats's, whose deity was Pan, who revelled in a wilderness of

sweets, where the very weeds were fragrant; nor like Byron's,

which was a volcano extinct. Tennyson's world was like

that fairer world of beauty of which they got glimpses only in

the delectable views of the imagination. It lay near

heaven. It had a holy ground. It might be an invisible world to

some, but others could glance up at it. It was a world

where the mortal met with the immortal, and saw the spirits of

the past move by grandly and solemnly, with music perfect and

ineffable, dying away into the faintest spirit-sweetness,

seeming to be answered by an ethereal far-off echo in the life

that is to come.

The lecturer showed that it required a refined and educated

taste to appreciate the poetry of Tennyson, which was noble,

moral, and pure, having a womanly sanctity pervading it.

He contrasted it with the poetry of Byron, noticing how the

latter was sunk in self-consciousness, while the former was

patriotic and representing humanity. He gave several

readings from the more prominent of Tennyson's poems, and

especially quoted from his In Memoriam. He

considered that it possessed so wide a range of thought and

beauty in its expression that he could not but consider it as

the greatest poetic effort of the last two hundred years—the

climax and crown of Tennyson's poetic life, to be equalled by

nothing he had yet done or would hereafter perform.

Massey's life with Rosina was becoming an increasing problem.

Continually agitating to get away from Edinburgh, her frequent

mood changes together with symptoms of illness that often

confined her to bed, eventually forced Massey to move.

Very depressed, he wrote to Stirling in March:

I have determined on leaving Edinburgh this spring and I

expect to take a little place in England near Hertford right in

the Country. Rent 20£ but I find that with all my

Lecturing efforts and planning I shall run short of 20£ or so to

leave here honourably and get there safely. Whether I can

honourably and safely appeal to you for that amount I am

doubtful and am really ashamed to do so after all your kindness

but I don't know what else to do. My Lectures are over for

this year and I have drawn on all my writing resources to the

utmost penny to get clear of and pay the large expenses of

moving our things a distance of 420 miles and still fall short.

I must trust to Lecturing for a Winter or two until I get my

next Book done—a sort of Autobiography— but the Summer will be

my difficulty … I am poor enough if you only knew it. In

Lecturing even I cannot leave my Wife at home she is not fit to

be left. Her head is sure to go bad when she is left alone

…[14]

Prior to his move, Massey prepared a list of lectures that he

proposed delivering to Associations and Mechanics Institutes

during the rest of the year. In The Scotsman,

24 March, 1858, were advertised the following:

A course of Six Lectures on our chief living Poets.

Cromwell and the Commonwealth.

The Poetry of Wordsworth, and its influence on the Age.

The Ideal of Democracy.

The Ballad Poetry of Ireland and Scotland.

Thomas Carlyle and his writings.

Russell Lowell, the American Poet, his Poems and Bigelow Papers.

Shakespeare - his Genius, Age, and Contemporaries.

The Prose and Poetry of the Rev. Chas. Kingsley.

The Age of Shams and Era of Humbug.

The Sonz-literature of Germany and Hungary.

Phrenology, the Science of Human Nature.

The Life, Genius and Poetry of Shelley.

On the necessity of Cultivating the Imagination.

American Literature, with pictures of transatlantic Authors.

Burns, and the Poets of the People.

The curse of Competition and the beauty of Brotherhood.

John Milton: his Character, Life and Genius.

Genius, Talent and Tact, with illustrations from among living

notables.

The Hero as the Worker, with illustrious instance of the Toiler

as the

Teacher.

Mirabeau, a Life History.

On the effects of Physical and mental Impressions.

The family's removal from Edinburgh to Hertfordshire,

which they hoped would ease their domestic strain, proved yet

again to be unfortunate. An account of their arrival was

sent to Stirling on 6 June 1858:

Mount Pleasant

Monk's Green

Nr Hoddesden

Herts.

… I have managed to take the four-hundred-and-twenty-mile leap

in the dark and alighted here three miles from Broxbourne

Station about pennyless with a great deal of our furniture

smashed in coming and wanting mending … I have got the farmhouse

of a Gentleman who does not live on his farm who lets me house

and garden for £20 Rent and taxes … It may be thought that when

I ask 5 guineas per Lecture in a public advertisement I am

pretty well off—but I am compelled to take my Wife with me

wherever I go, which as you may imagine makes my expenses

threefold—but this is quite necessary. I could not leave

her at home with the Children … [15]

For the ensuing five years Rosina was to make Massey's winter

lecturing tours, when they took place, a fearful but necessary

ordeal. Obliged on occasions to take her with him, he did

find it possible at times to promote her as giving recitations

of his poetry. These were well reported by the press,

saying that she read with exquisite taste and quiet power, but

many indispositions made her appearance at times quite

unpredictable. Thomas Cooper, who had kept an interested

eye on Massey's writing since he left the Chartist movement, was

less understanding about his domestic difficulties. He

wrote to Thomas Chambers on the 22nd August 1861:

… Mrs. Cooper seems young again! She runs after the

wild flowers with the elasticity of a girl & the rapt enjoyment

of a child!

Of such a wife a Poet might sing; but I wonder that poor Gerald

Massey parades the figure of the drunken plague to whom he is so

sillily tied himself … [16]

|

List of lectures.

|

Robert Burns' centenary fell on 25 January 1859. To

honour this event the directors of the Crystal Palace Company

organised a special poetry

competition with a winner's prize of fifty guineas.

Massey was quick to respond, as did 620 other entrants, but he

failed to win the prize. This was awarded to

Miss Isa Craig, a contributor

of verse to The Scotsman under the pen-name ‘Isa’.

There were 14,000 people present for the reading of her prize

poem. However, the judges, Richard Monckton Milnes MP for

Pontefract and prominent literary figure, Tom Taylor, author,

playwright and one time editor of Punch, together with

Theodore Martin, author and translator of literature,

recommended that the first six be published. Massey was

placed fourth in merit, and his entry

Robert Burns: A Centenary

Song was published in March.[17]

The reviews which referred also to some political items on

Palmerston that Massey had included in the book, were later to

cause him some concern.

James Macfarlan had also entered the competition [Robert

Burns: A Centenary Ode], but was unplaced.

For some time a number of friends had been suggesting that he

should make an application to the government to be placed on

their Civil Pension List. This had not been proceeded

with, due to Massey's political views that had received

considerable attention in previous years. However, with a

change of government, he considered it now to be worth

attempting.

His decision was strengthened by the press, which had

recently suggested such a step when they commented: ‘We are

sorry to hear that calamity has been busy in Mr Massey's

household, and that he is now struggling sorely to keep the wolf

from the door … The bounty of the Crown … would allow him to

give more time to his productions …’ They concluded rather

pointedly with a phrase that must have made Massey wince, ‘It

might also have the effect of making him a little more discreet

in the expression of his political opinions.’ William

Stirling promised to make Massey's request known to Lord John

Manners, then in the Earl of Derby's Cabinet.

As if to mitigate to some extent the loss of not winning the

Burns competition, he was informed that the government, on the

plea of Stirling, had granted him a gift of £100. His

wife, not knowing what to do, had a good cry, assuming that this

would solve their debt and other financial commitments.

This it did, but only temporarily, and he had to turn again to

Stirling for assistance. Becoming in arrears with his rent

and having failed to get any of his lectures published, he had

offered a journal editor some of his poems for £20 and not

received the money. Stirling dealt with the legal affair,

which was resolved satisfactorily, but Massey was left with the

expenses. In February 1860 he was called away from a

lecture tour:

On getting home I find my Wife too ill to have written … I

was sent for home as they thought her dying. I think she

may perhaps tide over her present attack but she is very ill.

And our present circumstances are enough to turn the scales

against her. We have to leave here this month and as I

have a house offered to me in the Lake District, and as the

Doctor thinks a change as soon as possible the only chance of

getting my Wife out of her morbid mental condition, I think of

going there if I can anyhow clear off to go, and raise enough

money to move with but how to do it I don't know for my

law-affair and this illness will break my back in a money sense

for some months to come … [18]

Before he left he wrote to Harney, who was then living in

Jersey and editing the Jersey Independent, hinting at his

availability for lecturing:

… The Bearer of this is a poor unfortunate Brother of mine

whom Poverty has driven into the Army . . . He never was able to

look after himself has worked and starved on and off for

years—and perhaps a year or two in the Army may do him some

good. I thought that you would be able to speak a word of

cheer to him in a place where he knows no one. I dare say

he will remember you—and that you would do this for Auld Lang

Syne … Perhaps some day I may get invited to your place in my

Lecturing capacity … [19]

In all Massey's writings and letters he never makes reference

to any of his brothers by name. In his poem

Our Heroes he

mentions:

|

I had a gallant Brother, loved at home, and dear

to me—

I have a mourning Mother, winsome Wife, and Children

three—

He lies with Balaklava's dead … |

but none of his brothers is listed in published Crimean war

deaths in battle.[20]

The house to which the family moved, ‘Brantwood,’ overlooking

Lake Coniston, was owned by his friend ‘Spartacus’ of earlier

Chartist days, W. J. Linton.

A wood engraver and former contributor of poems and articles to

Harney's papers, he had in 1849, together with Thornton Hunt,

commenced the weekly radical Leader with G. H. Lewes as

literary editor. But no sooner had the family moved to

Brantwood, than Massey found that circumstances appeared as

usual to conspire against any form of successful literary

endeavours. The first incident occurred on the family's

arrival at Coniston railway station, several miles from

Brantwood, when he found that he had insufficient money to

redeem the furniture, which had to remain at the station.

At that time he hoped to be able to furnish some rooms in the

property, which he could sub-let in the summer months and make a

good profit. The second incident followed a three week

lecture tour, for which he received four five pound notes.

He had managed to clear his furniture from the station, but

still remained in debt. During his absence an attempt had

been made to distrain on his furniture, which appeared to be the

only items of value he possessed. As he was about to

enclose some of the money ready to post, his children who were

playing near him and asking for various pieces of paper, took

them with some other loose sheets, and put them on the fire!

Fortunately William Sterling was again able to help out and

Massey, very dispirited, wrote glumly that not much choice was

given to him in anything that he did, and that his circumstances

at times placed him in a position that was as painful to him, as

perhaps appeared unaccountable to other people. The only

things he could rely on were his lectures during the winter

months, and these were frequently interrupted from home.

In this situation, he again considered the possibility of being

placed on the government pension list, although as he mentioned

to Stirling, he felt strongly against any appeal being made

personally to Lord Palmerston, again in power with a Liberal

Government, as he had no faith in him politically. In a

second letter he reiterated his doubts, due this time to his

previous literary indiscretion:

When writing to you about Lord Palmerston, I quite forgot

that I had written about him in my last publication, and the

Saturday Review quotes it as very funny.[21]

The fun to them would be death to me, I expect with regard to

any chance with his Lordship and friends. I don't suppose

he reads my verses but I suppose they all see the Saturday

Review … [22]

That journal had reviewed his Robert Burns: A Centenary

Song and Other Lyrics not entirely favourably. While

acknowledging his eye for external beauty, his ear for melody

and an appreciation of feeling and grace, it denied him

possession of fancy or facility. It considered that

Socialist and Chartist poetry was too narrow in thought, and his

poetical faculty debased by a selfish view of social relations;

but that he still might win an abiding place in literature if he

would leave off politics. Despite these criticisms, the

Review did consider that his poem 'Old

Harlequin Pam' was yet more amusing than the other political

silhouettes in Craigcrook Castle's 'Glimpses

of the War'. In these poems he had made allusions to

Czar Nicholas, Napoleon and Palmerston. Nicholas had been

referred to as a statue of Satan, looking down on a drooling and

mumbling British Lion ineffectually wagging its tail. But

in Massey's poem, 'Nicholas and

the British Lion', the Lion has some particularly sharp

teeth that it uses, when Czar Nicholas dares to thrust his head

in its mouth, to bite it off [23]:

|

… And the poor old beast, at whose aspect mild

The meanest thing dared rail,

Shakes his mane like a Conqueror's bloody plumes,

And—quietly wags his tail … |

But the poem on Palmerston was far less subtle:

… In an Age of Sham,

Our greatest of Humbugs is Harlequin Pam.

Humbug in riches it reeks and rolls,

Humbug in luxury lazily lolls,

Humbug in Senate and Humbug in Shop,

Humbug makes sweet the Assassin's last drop;

And Pam, Pam is the King of all Sham,

Our greatest of Men must be Harlequin Pam.

England, this is the Man for you,

The 'Times' says so, and it must be true … |

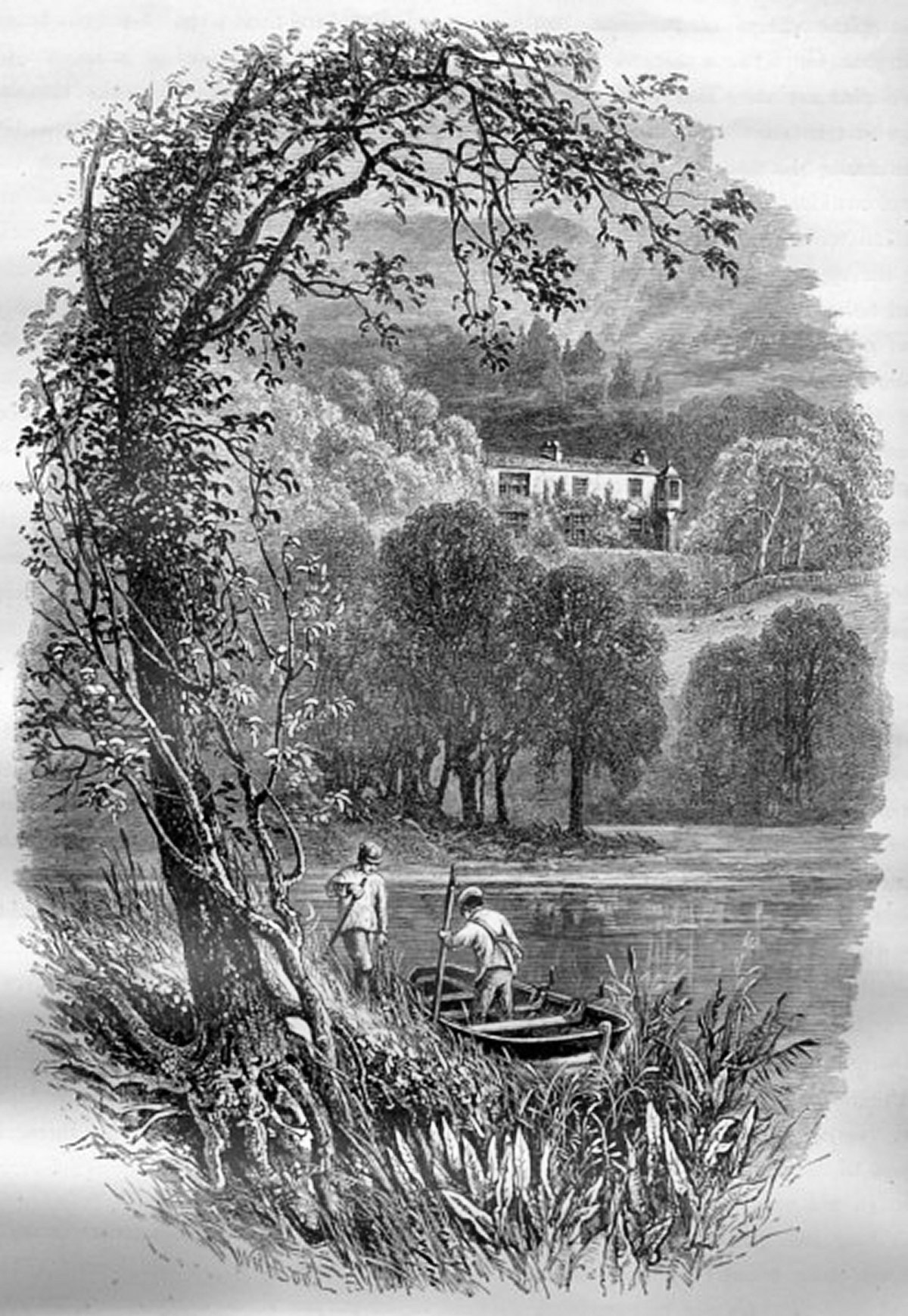

|

Brantwood. (Picturesque Europe, Appleton, N.Y., 1875).

|

During his short stay at Brantwood, he wrote one article for

the North British Review on ‘American

Humour’.[24] Most of his published

articles were based on lectures delivered during the winter

months, when not interrupted by his wife's illness. In

this article he argued that humour preceded wit, the former

commencing with the practical joke that deals with outward

things, the nature of the action, and reaches both the educated

and uneducated. Wit is concerned more with the quality of

thoughts, and is more artificial, being culturally connected

with a more complex state of society. He considered that

the greatest of all American humorists was James Lowell, whose

Biglow Papers reminded him of the lusty strength and boundless

humour of great Elizabethan literature.

Commencing in March 1860 he wrote a series of poetical

contributions for Charles Dickens' magazine All the Year

Round. Five signed poems were published up to August,

with three unsigned from August to November, for which he hoped

to be paid ten guineas each. But in a letter from Dickens'

assistant William Wills to Massey, Dickens had considered that

as the copyright was available to Massey after a reasonable

time, following publication in All the Year Round, the

sum of £50 in total was fair. ‘… You will, I hope, believe

on reflection that the fifty pounds is a fair and just

remuneration for the advantage we derive from them. If you

do think so, we may at this moment cry, "quits!"…’[25]

Massey also contributed 30 poems to Alexander Strahan's Good

Words magazine from October 1860 to April 1872, and poems

and epigrams to Cassell's Magazine and Punch in

the early to mid 1870s.

By the spring of 1861 the family had made another move,

probably finding that Coniston was too isolated and inconvenient

for the travelling necessary for Massey's lectures.

Accommodation was taken in the High Street, Rickmansworth,

between Basing House—built in 1740 on the site of William Penn's

house—and the National School House.

Massey's next book, published in April 1861, was

Havelock's March and Other

Poems, based on the revolt of the Indian Bengal Army.

Sir Henry Havelock's ‘Army of Retribution’ march for the relief

of Cawnpore in 1857 formed the basis of the poem. Massey

described this as an ‘historic photograph’, rather than a poem

in the aesthetic sense. The book was received again rather

tepidly by the press, as ‘abounding in gracious phrases and

vigorous thought—yet quite unable to hold its place in the

affections or in the memory’.[26] The

other material was largely ignored because, as Massey wrote in

his own copy, ‘And the d—d fool of an Author forgot to say that

the rest of the Book was new and so the Critics treated it as

all reprint.’ But the treatment of the poem,

Havelock's March,

was well up to the partisan standard expected of Massey when he

dealt with British nationalism:

|

Come hither my brave Soldier boy, and sit you by

my side,

To hear a tale, a fearful tale, a glorious tale of

pride;

How Havelock with his handful, all so faithful and

so few,

Held on in that far Indian land, to bear our England

through. . .

No tramp, no cheer of Brothers near; no distant

cannon's boom;

Nothing but Death goes to and fro betwixt the glare

and gloom.

The living remnant try to hold their bits of

blood-stained ground;

Dark gaps continual in their midst; the dead all

lying round;

And saddest corpses still are those that die and do

not die;

With just a little glimmering light of life to show

them by . . . |

He ignored or appeared unaware of one of the immediate causes

of the war which placed British behaviour in a less acceptable

stance, and resulted in gross atrocities against the British

residents. Attempts to convert some of the Indian sepoys

to Christianity had resulted in stories of compulsory

conversion, and the annexation of the Oude province disbanded

that king's army, thereby causing much discontent and some

violence. The additional story that pig and cow fat was

used to grease a new paper made for cartridges spread rapidly

among the Moslems and Hindus despite British efforts to deny it,

and eventually the whole Bengal army of 100,000 men became

involved. The resulting massacres shocked the British

public.[27] During his lecture tours in

the north of England Massey had made the acquaintance of John

King, a type-founder from Sheffield who had developed as an

author and poet. As well as contributing to local papers,

his small number of published works included a sketch of

Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn

Law rhymer, while his biography of Allesandro Gavazzi, Italian

priest and social reformer, had been reprinted several times and

was a source of finance for a number of years. Now living

with his wife and three children in a third floor apartment at 7

Newman Street, Oxford Street, London, King was enduring

considerable hardship. Unable to write due to pulmonary

tuberculosis which confined him to bed, he was reduced to

selling his household items in order to pay the rent.

Massey rather audaciously asked Stirling if he could visit King,

and perhaps get him some aid from the Literary Fund. Good

natured as always, Stirling was pleased to assist. But

King had already obtained £25 from the fund two years

previously, and they turned down his application on the grounds

that between that date and the present, he had not written any

more books. King then ended all further chance of a grant

when he wrote that ‘even dogs have received the sympathies of

the poorest kitchen’, and that he could not stand the ordeal of

making another application for fear of further refusal.[28]

In May or June 1861 due to more pressing financial

difficulties Massey wrote again to William Stirling, this time

querying the possibility of obtaining a grant from the Royal

Literary Fund on his own behalf:

... The immediate occasion was that my Father had just been

finally turned off from his 8/- per week work and his future

bread depended on me or the Workhouse. He is nearly 70

years old and has worked at one place for 40 years. They

now turn him adrift penniless … [29]

Whilst I was down in the North my effects were sold by the

Sheriff of Lancashire for debt—not a large one either, and I

could not help it. Yet according to all appearance I ought

to be well off … For my last book I got £30 only which is not

much in the way of repayment for the life-blood, time, and

critical bullying it costs. I don't want, and never have

wanted to write for a living, only my home affairs have been

such as prevented me from taking a situation from home … I don't

understand the reception of my Book. [Havelock's March and

other poems. Ed.] It seems to have fallen dead almost.

I thought it had some life in it and would meet with a different

response. I am sure of having reached a greater simplicity

and directness of speech. So I am told that there is

nothing in the Book to equal Babe Christabel, which was a

merest imagery … [30]

A minor appreciation of his earlier efforts to uplift the

working-class was made that year by a poet colleague,

William Billington.

A pleasant little volume of poems,

Sheen and Shade,

had a lyric dedicated to Massey, in which he was referred to as:

|

A second Burns, that never could be bribed,

By Fear or Favour, to forsake the class

Whence thou didst spring—the lowly labouring mass,

Whose feelings, fears and hopes have tipped with

flame

Thy potent pen! … [31] |

He noted Billington's kindness some years later, but at that

earlier time he would have preferred hard cash to pleasant

phrases.

By November he had, on the advice of friends, decided to make

an application to be placed on the Civil Service Pensions List,

despite his disinclination to appeal to Viscount Palmerston,

then Prime Minister and First Lord of the Treasury. This

involved asking persons of influence who knew him, his work and

circumstances, to write testimonials on his behalf as being a

proper subject for consideration. Carlyle, Ruskin, Landor,

Thackeray, Browning, Lady Alford and Tennyson responded.[32]

His request to Tennyson sent on the 20 November, stated that he

was obtaining as many recommendations and testimonials as he

could from persons of influence and authors of eminence, and

that ‘… A word from you will help them much and me still more …

The praise my verses have got has not meant much in the shape of

pudding, and I find it desperate hard work to cling by the

skirts of literature so as not to go down quite …’[33]

He sent a letter also to the Rt. Hon Benjamin Disraeli, asking

if he would consider, in addition to the names already appended,

to add his.[34] Massey hoped, if his

memorial was successful, to obtain a regular grant of £100 per

year. Unfortunately it was not.

He wrote to Stirling on 18 July 1862, ‘… You will, I presume,

have seen the published Pension List without my name? I

suppose my chance is gone now for a year. What I am to do

I don't know. I was led to think from words dropped by

Lord Palmerston that the application would have been successful

…’[35] Morgan Evans, who had drawn up

the memorial on Massey's behalf and was aware of his

circumstances, was able to solicit a few of the signatories of

the memorial to join in a small subscription fund to give aid

during Massey's pressing domestic difficulties.[36]

Lady Alford subscribed £25, but the total amount obtained is not

recorded.[37]

During 1861 he contributed thirty-five reviews for the

Athenæum, which included John Greenleaf Whittier's Home

Ballads and Poems. ‘Here is poetry worth waiting for, a poet

worth listening to. . . It has the healthy smell of Yankee soil

with the wine of fancy poured over it …’[38]

Two articles for the North British Review completed his

literary output for that year, of which a sensitive ‘Poems

and Plays of Robert Browning’ referred to Browning's lack of

popular appeal at that time. This was due, Massey

considered, to his subject matter which required philosophic

appreciation rather than the emotional energies of

identification. Nevertheless, he admitted, together with

Douglas Jerrold and many others, to have found Browning's

‘Sordello’ incomprehensible.[39] ‘Poets

and Poetry of Young Ireland’, although dealing with poets

less well known in England, benefited from a greater cohesive

structure in poetic comparisons. The differentiation

between the Norse influence in Anglo-Saxon England and the

Celtic in Ireland can be detected, he said, by the English

appeals to principles, and the Irish for appeals to affection

for a person; to the future when hopeful, but turning to the

past when mournful. These elements, Massey asserted,

present themselves in their poetical subject matter. His

strong subjectively tonal description of the poet James Mangan,

who was employed in Dublin University Library, is distinctly

Dickensian:

The white halo of bleached hair round the head, the dark halo

round his eyes—eyes of a weird blue, as of one who could see

spirits; a lighted corpse-like face, with that faint lavender

shadow which they wear who eat opium, and dream its dreams.

A strange figure, and yet not startling: a child would not have

feared to pull the old brown carmelite coat, climb the offered

knee, and kiss the face where queer humour and quaint pathos

mingled …[40]

He made another attempt to obtain a permanent job around late

1861 or early 1862 when he answered an advertisement for a well

paid salaried social lead article writer for the Daily

Telegraph. Following an interview and having been

appointed for a trial period, he was told after this time that

whilst he had great ability, he was unsuitable on account of his

articles being too political.[41] This

was another disappointment, as he had hoped, if successful, to

have given up poetry for prose writing. On taking up the

appointment he had also given up his lecturing for that winter,

and he found himself once again without any regular income.

Following the failure of his first attempt to obtain a Civil

List pension, he was advised to present his memorial again to

the government, for consideration early in 1863. At the

same time he began the necessary proceedings to make an

application to the Royal Literary Fund for a monetary grant.

This also involved obtaining testimonials from persons of note,

and Lady Marian Alford and Professor Blackie were, among others,

willing to respond. The application proved successful with

the result of fifty pounds the following January. Massey

wrote to the fund acknowledging that the money had come at a

time ‘… when my poor Wife is suffering from one of the worst

mental attacks she has ever had and without your assistance I

might have been unable to secure for her the aid and attendance

which was so necessary’.[42] Rosina's

mental affliction had reached a crisis, and doctors were

pressing for her removal to a mental hospital. Usually

able to control her violent episodes by mesmerism, Massey found

that this was not having the usual calming effect. One

night they were woken up by sounds of scratching and knocking on

the footboard of the bed. When nothing was found to

account for the noises, and the possibility of burglars had been

investigated, the housekeeper and her mother were called to the

bedroom and, by now, a hysterical Rosina. The sounds

continuing, Massey thought ‘epidemic delusion’ was no answer,

and that the idea of ‘spirits’ making those noises was

disgusting. However, by means of a code of raps, they

determined that the noises had been made deliberately to bring a

communication to their attention. Rosina, who appeared to

see two people, sat up in bed, and said, ‘Mother—Mary!’ By

further questioning using the same code, they learned that

Rosina's daughter and mother were present. Massey was told

not to put his wife away the next day, although she would be

worse, but that she would be better by the following week.

He was able to report later that, although the spirits had as

often been wrong as right, on that occasion they had been

perfectly correct.[43]

The year 1862 continued the general unfortunate trend in

Massey's affairs. Healthwise he suffered from tonsil

abscesses that he had to have lanced, and nervous stress showed

itself by palpitations of the heart. This latter condition

continued throughout his life making him fear that he had heart

disease, despite being assured otherwise by doctors on varying

occasions. That year he was able to write only four

reviews and one article. In ‘The

Poems and other Works of Mrs Browning’ he commented (for

that present era) with notable exceptions of Charlotte Brontë

and George Eliot, on the lack of art and literature composed by

women due, as he considered, to their whole of life uttered in

one word ‘love’, and their whole world compressed in the one

word ‘home’. They live reality in such fullness, and there

is no imperative need to seek refuge in an ideal world. And

then, where is the incentive to sing or write? The late

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, he considered, was another of the

distinguished women whose imagination, tenderness, feeling and

vigour of thought made her poetry outstanding. Her most

famous and powerful work, ‘Aurora Leigh’ competes, Massey said,

successfully with the novelist in enlarging the boundaries of

the poet's outer world.[44]

In early November and yet again almost pennyless, he deplored

the fact that with winter approaching he was unable to afford

the necessary warm clothing for his children. Furthermore,

because of his wife's mental condition he had been prevented

from making bookings for winter lecture tours. Virtually

at the last minute however, he was able to arrange with Harney

in Jersey to present two lectures on 26 and 27 November at the

Lyric Hall, Cattle Street, St. Helier. He had mentioned

previously the possibility of lecturing in Jersey when he wrote

to Harney in 1858. In advertising the lectures a week in

advance he was hopeful that his wife might at the same time be

well enough to travel and give some poetical readings. To

give Harney much credit he gave a three column introduction in

the Jersey Independent, with a biographical sketch of

Massey together with two of his poems from Havelock's March.

Massey should have made his first appearance on the 26th, but

was delayed and had missed the boat by less than a minute.

His first lecture on the 27th was heralded by a poem in the

Independent, 'Welcome to Gerald Massey', that was written

probably by Harney:

|

Thou man of Nature's moulding, son of song,

First tuned the harp the storms of life among,

Formed by the Muse, thy meek impassion'd mind

'Midst life's encounters, tender grew, and kind;

It gave thee early bitter draughts to drink.

Mid scorn and hardship, taught thee how to think,—

To spurn oppression, hearts, and hands, to free,

And bid the world achieve its Liberty... |

Although the hall was not filled, 'Sir Charles Napier, the

Conqueror of Seinde' was appreciated by the audience of about

150 who frequently interrupted by applauding. But the

Jersey Times for reasons not stated, did not consider Massey

a first class lecturer. The second lecture, ‘England's Old

Sea Kings; how they lived, fought and died’, had a much greater

attendance, and the subject matter lent itself better to

Massey's ‘high poetical powers … the lecturer's

descriptions of our naval exploits were heart-thrilling and

brilliant, and were received enthusiastically by the audience’.

Due to the success of those two lectures, an extra booking was

made for ‘Yankee Humour’ early the following week. By that

time Rosina was well enough to appear personally, and she was

able to replace her husband on the 4 December for recitations of

his and other more well known poets' verse:

If an exception be made to the weakness of this lady's voice,

it may be said, with truth, that she reads very well; her

expression is sweet and pleasing, and her enunciation distinct.

The poems which she read embraced several of her husband's best

productions, interspersed with choice selections from the Poet

Laureate, Russell Lowell, and poor Hood … The interesting

entertainment closed with ‘A

National Anthem’, by Massey.

Before leaving the Channel Isles, his wife feeling well at

that time, he was able to arrange two more lectures, this time

in Guernsey the following week. Massey's religious

opinions were then not yet overtly unorthodox, so his reception

was in contrast to Charles Bradlaugh's lecturing venture in that

mainly Catholic island in 1861, when he was met with great

hostility. Together with a threatened royal salute of

rotten eggs, placards exhorting ‘Kill the Infidel’ were

displayed in the town, and the lecture room was damaged.[45]

Massey repeated his carefully chosen ‘Old England's Sea Kings’

to a highly respectable audience of about six hundred, and the

reporter ‘Found much to admire in his composition—much to

confirm the reputation to which he has attained.’ But

added, ‘We should observe that Mr Massey is not an elocutionist

…’ Massey's second lecture that week was assisted as in

Jersey, by Rosina's poetry readings. ‘Mrs Massey read in

what may be termed "a drawing-room" style, without any attempt

at declamation. Her reading was intelligent and touching

and was much applauded.’[46]

The lecture series barely saved Massey from total financial

disaster that winter, and early in 1863 to his great relief he

heard that he would be granted a yearly allowance of £70 Civil

List pension. The Scotsman announced the pension as

having been awarded "in appreciation of his services as a lyric

poet sprung from the people". But fate had one more card

to play, and in May he was compelled yet again to ask William

Stirling for temporary assistance:

‘… it is the last effort I can make to save my Furniture from

being sold on the 16th Inst. The Pension has not yet come,

and if it is not quick 'twill be too late … I have not earned a

penny by lecturing now these two years, not being able to leave

home.[47] All my Books are in

pawn at Mr. Wood's High Holborn, and in the last extremity I was

driven to execute a ‘Bill of Sale’ on my Furniture. And I

am perfectly unable to meet a payment of £6.10.0 on the 16th

Inst. I do not know where to turn. Lady Alford is in

Madeira with her Son. I know no one else who could help me

with £10. The position is not owing to any want of effort.

I have tried and tried desperately. I have some £50 worth

of matter not yet used in the hands of Publishers. But the

payments will come too late … P.S. I enclose a Note which

refers to the Bill of Sale which gives Mr. Hollingsworth it

seems the right to ask for my Rent Receipts. I don't know

whether it makes the matter more serious by the Rent not being

paid.’[48]

Massey finally received his pension on 18 June, with a

declaration of regret conveyed by Lord Mount-Temple, that the

amount available at that time should have been so small. [49]

Although not yet free from financial constraints, he was able

to repay his debts to Stirling, and his position began to show a

slight improvement. Rosina, however, remained a cause of

much disturbance, particularly in regard to his literary affairs

and lecturing activities.

[Chapter 5]

|

|

NOTES

|

|

1. |

Craigcrook Castle,

119-21. |

|

2. |

Fraser's Magazine, February 1857, 223-26. (Little Lessons for

Little Poets) Reprinted in Stasny, John F., Victorian Poetry.

A Collection of Essays from the Period (New York, Garland,

1986). |

|

3. |

Cassell's Magazine, 8, (Nov. 1873), 113-4. |

|

4. |

Athenæum, 25 Oct. 1856,

1302-3. |

|

5. |

Strathclyde Regional Archives, Stirling of Keir Collection. Mss.

TSK.27/7/221 and TSK.29/7/220. Undated. |

|

6. |

The

Huntington Library, San Marino, California. HM. FI 3294. Undated. |

|

7. |

Letter to

Dixon from Massey in the Mitchell Library, Glasgow. Ms. Main 891114.

Undated. |

|

8. |

Life

and Letters of Sidney Dobell, 2, 94. |

|

9. |

Newcastle Chronicle, 29 Jan. 1858. |

|

10. |

Quoted in

The Reasoner, 6 Jan. 1858, 6. |

|

11. |

Henry Buckle

(1821-1862). Fluent linguist and historian, freethinker and radical.

Author of History of Civilisation in England. In a letter

from 12 Henderson Row, Edinburgh, Massey thanks Buckle for ‘the

copies of Orsini.’ (Ms. Duke University, Great Britain papers, Misc.

Vol. 1, p. 24. Undated.) These probably included the Memoirs and

Adventures of Orsini, trans. 1857. |

|

12. |

Northern Daily Express, 24 Feb. 1858. |

|

13. |

North

British Review, 28, (Feb. 1858), 231-50. |

|

14. |

Stirling

of Keir Collection. Ms. TSK.29/8/79. Undated. |

|

15. |

Ibid. Ms. TSK.29/8/30.

Two ms. poems are appended, that Massey sent to Stirling as an

example of his present political opinions, ‘A Poem for Pam’ and ‘The

Broad-bottomed Ministry’, Ms. TSK.29/10/135. The latter was

published in his next volume of poetry,

Havelock's March, as ‘Farmer

Forrest's Opinion of the Broadbottomed Ministry’. |

|

16. |

Ms. The

Bishopsgate Institute. |

|

17. |

Robert Burns: A Centenary Song,

and Other Lyrics (Glasgow, Kent, 1859). Included also (with

Macfarlan's poem) in

Anderson, G., Finlay, J., (Eds.) The Burns Centenary Poems (Glasgow,

Murray, 1859). |

|

18. |

Stirling

of Keir Collection. Ms. TSK.29/10/128. Undated. |

|

19. |

The Harney Papers,

letter 156. Haight suggests a date of 1856 for this letter, but

Massey was in Edinburgh until mid 1858 prior to his move to

Hoddesdon. |

|

20. |

Cook F., Cook, A.,

Casualty Roll for the Crimea (London, Hayward, 1976). |

|

21. |

Saturday Review, 5

Mar. 1859, 281-2. |

|

22. |

Stirling

of Keir Collection. Ms. TSK.29/10/134. Undated. |

|

23. |

The poem 'Nicholas

and the British Lion' was included in W. Davenport Adams'

Comic Poets of the Nineteenth Century (London, Routledge, n.d.

[1876]). |

|

24. |

North British Review, 33,

(Nov. 1860), 461-85. |

|

25. |

The

Huntington Library, San Marino, California. All the Year Round

letterbook, HM. 17507.f.114.E.A. Oppenlander's Dickens' All the

Year Round: Descriptive Index and Contributor List (New York,

Whitston, 1984), p. 281, does not give attributions to Massey's

poems ‘Old King Hake,’ 25

Aug. 1860, 468-9, ‘A Letter in

Black’, 1 Sep. 1860, 494-5 and ‘Poor

Margaret’, 3 Nov. 1860, 83-84 in All the Year Round. A

further poem by Massey, ‘The

Sunken City’ was published on 23 May 1863, p. 231 and not

attributed. Oppenlander, part quoting Wills' letter to Massey (p.

53-4) inserts ‘not’ in the paragraph quoted above, to make it read:

‘. . . If you do not think so, we may at this moment cry

"quits!"’

which makes the letter sound like an ultimatum rather than

a polite request. I am grateful to Sara Hodson, Curator of

Literary Manuscripts at The Huntington Library for providing me with

a full transcription of this letter. Also in the file is a

letter from Wills to Massey dated 16 May 1860 in which Wills returns

a poem to Massey:

‘… Read the poem in our No 16, and you will find you have

been forestalled. It may however be a little amelioration of your

disappointment to know that your predecessor was your accomplished

landlord, Mr. W. J. Linton …’

(The Huntington Library, San Marino, HM. Fl 5432). Linton's

poem ‘Great Odds at Sea’ [see ‘Grenville's Last Fight’] was

published in the issue of 13 Aug. 1859, 378-9, and included also in

Linton's own pasted up copy of Prose and Verse, 9, 159-62, held in

the British Library. Both Linton's and Massey's poems refer to the

sea action of Sir Richard Grenville, in which he was killed in

action with Spanish ships off the Azores in 1591. Massey's poem ‘Sir

Richard Grenville's Last Fight’ was published later in his

Havelock's March. |

|

26. |

Athenæum, 17 Aug. 1861, 209-10. |

|

27. |

Anon., Narrative of

the Indian Revolt (London, Vickers, 1858). For an Indian's

account of the causes of the war, see pps 357-64. |

|

28. |

Royal

Literary Fund File no. 1515. |

|

29. |

In an account of some

incidents in his life, Massey stated that his father had been forced

to give up work due to breaking his leg, and the firm pensioned him

off with a 4d. piece. |

|

30. |

Stirling

of Keir Collection. Ms. TSK.29/11/125-127. Undated. |

|

31. |

William Billington,

Sheen and Shade:

Lyrical Poems. (London, Hall & Virtue, 1861), 141. |

|

32. |

Ms. letter to the Rev.

Henry Alford (1810-1871) Dean of Canterbury, editor of the Greek

Testament and the Contemporary Review, requesting his

signature. (Gerald Massey Collection, Upper Norwood Library,

London.) |

|

33. |

Ms. The

Tennyson Research Centre, Lincoln. Undated. |

|

34. |

Ms. in the Bodleian

Library, Dep. Hughenden 136/1, fols. 70-73, together with a copy of

the printed Memorial. |

|

35. |

Stirling

of Keir Collection. Ms. TSK.29/12/176. |

|

36. |

Morgan Evans

(1830-1899). Journalist and reviewer for the Athenæum, he

lived in Haverfordwest. |

|

37. |

Stirling

of Keir Collection. Ms. TSK.29/12/65 |

|

38. |

Athenæum, 31 Aug. 1861,

276-7. |

|

39. |

North British Review,

34, (May 1861), 350-74. |

|

40. |

Ibid.

35, (Nov. 1861), 415-44. |

|

41. |

The exact dates are

unknown. The files of the Daily Telegraph are very scanty for

that period. |

|

42. |

Royal

Literary Fund File no. 1581. |

|

43. |

Medium

and Daybreak, 17 May 1872, 177-8. |

|

44. |

North British Review, 36,

(May 1862), 514-34. |

|

45. |

Bonner, Hypatia

Bradlaugh, Charles Bradlaugh. A record of his life and work 2

vols. (London, Unwin, 1908 ed.), 1, 189-93. |

|

46. |

Jersey Independent,

20 Nov., 25 Nov., 27 Nov., 28 Nov. 1862. Jersey Times,

28th Nov.,

29

Nov., 1 Dec., 5 Dec.,

8 Dec. 1862 (from the Guernsey Star). |

|

47. |

He did not mention the

earlier lectures in Jersey, perhaps deliberately as they were not

part of a usual lecture circuit, or maybe he thought he would

receive more sympathy. |

|

48. |

Stirling

of Keir Collection. Ms. TSK.29/13/184. Undated. |

|

49. |

Colles, W.M.,

Literature and the Pension List (London, Glaisher, 1889), 44. |

|