|

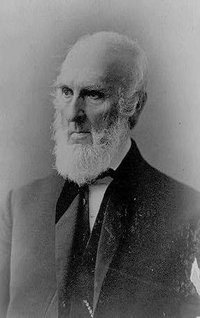

Home Ballads and Poems.

By John Greenleaf Whittier.

Boston, U.S., Ticknor & Field; London, Low & Co. |

|

|

John Greenleaf Whittier

(1807-92) |

HERE is poetry worth waiting for, a poet worth listening to. Mr. Whittier may not ascend any lofty hill of vision, but he is clearly a seer according to his range.

His song is simple and sound, sweet and strong. We take up his book as Lord Bacon liked to take up the bit of fresh earth, wet with morning and fragrant with wine.

It has the healthy smell of Yankee soil with the wine of fancy poured over it.

We get a gush of the prairie breeze, weird whispers from the dark and eerie belts of pine, wafts of the salt sea winds wandering inland, superb scents of the starred magnolias and box-tree blossoming white.

We hear the low of cattle, the buzzing of bees, the lusty song of the huskers, brown and ruddy, the drunken laughter of the jolly bob-o-link. Here are green memorials of the New World's spring of promise, golden memorials of her abundance when the horn of autumn is poured into the overflowing lap of man; we see the white-horns tossing over the farmyard wall, the cock crowing in the sun with his comb glowing a most vital red, the brown gable of the old barn, roses running up to the eaves of the swallow-haunted homestead, the June sun "tangling his wings of fire" in the net-work of green leaves, the aronia by the river lighting up the swarming shad, the ricer full of sunshine, with the bonny blue above and the blithe blink of sea in the distance, and many a sight and sound of vernal life and country cheer.

No American poet has more of the home-made and home-brewed than Mr. Whittier.

His poetry is not filtered from the German Helicon; it is a spring fresh from New World nature; and we gladly welcome its

"sprightly runnings."

Our Yankee Bard is among poets what Mr. Bright is amongst the peace men.

He has the soul of some old Norseman buttoned up under the Quaker's coat, and the great bursts of heart will often peril the hold of the buttons, whilst the speaker with all his native energy and a manly mouth is

"preaching brotherly love and driving it in." With him, too, the Norse soul is found fighting for freedom, and be has good service in making the heart of the North beat quicker for the day when black slavery shall be no more, and in bringing about the present movement which the hopeful look upon as preparatory to the gathering up of the slave forces for a final flight.

The poet is less martial in his latest book. He has learnt to possess his soul with more patience.

The momentum is more subdued, and has a slower swing, quietly intense.

Longer brooding has brought forth a more perfect, though less striking result.

Take, for example, a few of the noble lines in remembrance Joseph Sturge, a man after our poet's own

heart:—

|

For him no minster's chant of the immortals

Rose

from the lips of sin;

No mitred Priest swang back the heavenly portals

To let the white soul in.

But Age and Sickness framed their tearful faces

In the low hovel's door,

And prayers went up from all the dark by-places

And shelters of the poor.

Not his the golden pan's or lip's persuasion,

But a fine sense of right,

And truth's directness, meeting each occasion

Straight as a line of light.

The very gentlest of all human natures

He joined to courage strong,

And love out-reaching unto all God's creatures

With sturdy hate of wrong.

Men failed, betrayed him, but his zeal seemed nourished

By failure and by fall.

Still a large faith in human kind he cherished,

And in God's love for all.

And now he rests his greatness and his sweetness

No

more shall seem at strife;

And death has moulded into calm completeness

The statue of his life.

Where the dews glisten and the song-birds warble,

His dust to dust is laid,

In Nature's keeping, with no pomp of marble

To shame his modest shade.

The forges glow, the hammers all are ringing;

Beneath its smoky

vail,

Hard by, the city of his lore is swinging

Its clamorous iron flail.

But round his grace are quietude and beauty,

And the sweet heaven

above,—

The fitting symbols of a life of duty

Transfigured into love. |

|

|

In a time of trouble and struggle, of war and rumours of war, these lines take one with their quiet mastery and peaceful music, sinking softly into the soul as if spoken by the very Spirit of Rest.

To quote the poet's own words the whole picture is—

|

Beautiful in its holy peace as one

Who stands at evening, when the work is done,

Glorified in the setting of the sun. |

|

|

'Telling the Bees' is a ballad as fine as the custom it celebrates is curious. 'The Pipes at Lucknow' is a spirited poem. Many, the stanzas of 'The Shadow and the Light' might have been found worthy of weaving into 'In Memoriam':—

|

Ah, me! we doubt the shining skies

Seen thro' our shadows of offence,

And drown with our poor childish cries

The cradle-hymn of kindly Providence.

And still we love the evil cause,

And of the just effect

complain;

We tread upon life's broken laws,

And murmur at our self-inflicted pain;

We turn us from the light, and find

Our spectral shapes before us thrown,

As they who leave the sun behind

Walk, in the shadows of themselves alone.

And scarce by mill or strength of ours

We set our faces to the day;

Weak wavering, blind, the Eternal Powers

Alone can turn us from ourselves away. |

|

|

Mr. Whittier is most successful perhaps in the present work in setting gravely sweet and kindly comforting thoughts to a common ballad measure, which he has tried again and again until it reaches its perfection in pieces like 'My Psalm' and 'My Playmate.'

Here is a specimen of the latter poem:—

|

O playmate in the golden time!

Our mossy seat is green,

Its fringing violets blossom yet,

The old trees o'er it lean.

The winds so meet with birch and fern

A sweeter memory blow;

And there in spring the veeries sing

The song of long ago.

And still the pines of Ramoth wood

Are moaning like the sea,—

The moaning of the sea of change

Between myself and thee! |

|

|

'My Psalm' is only to be felt thoroughly in the eve eve of life, when the mellowing influences of age and experience have done their work, and the golden haze gathers about the closing of the calm day, touching this world with the beauty of the next.

It must be read slowly and thought-fully to be felt deeply:—

|

All as God wills, who wisely heeds

To give or to withhold,

And knoweth more of all my needs

Than all my prayers have told!

Enough that blessings undeserved

Have marked my erring track;

That wheresee'er my feet have swerved,

His chastening turned me back;

That more and more a Providence

Of love is understood,

Making the springs of time and sense

Sweet with eternal good:

That death seems but a covered way

Which opens into light,

Wherein no blinded child can stray

Beyond the Father's sight;

That care and trial seem at last,

Thro' Memory's sunset air,

Like mountain range over-past,

In purple distance fair:

That all the jarring notes of life

Seem blending in a psalm,

And all the angles of its strife

Slow rounding into calm.

And so the shadows fall apart,

And so the west winds play;

And all the windows of my heart

I open to the day. |

|

|

But we shall not be doing justice to these 'Home Ballads' if we do not vary the strain.

They are not all devoted to the life that is lived in our day. Here and there we find a bright and rigorous portrait painted on the dark background of the past.

Such is that of 'Samuel Sewall,' the man of God with a "face that a child would climb to kiss."

Sometimes, also, the poet peers into the shadowy land of Indian legend, watching, questioning the darkness, till the mist begins to stir and transform itself into spectral

life. Then he will tell us a tale of the early time of witchcraft and cruelty.

Our concluding extract is from a robust ballad, called

|

SKIPPER IRESON'S RIDE.

Body of turkey, head of owl,

Wings a-droop like a rained-on fowl,

Feathered and ruffled in every part,

Skipper Ireson stood in the cart.

Scores of women, old and young,

Strong of muscle and glib of tongue,

Pushed and pulled up the rocky lane,

Shouting and singing this shriIl refrain:

"Here's Flud Oirson, fur his horrd horrt,

Torr'd an' futherr'd an' corr'd in a corrt

By the women o' Morble'ead!"

Wrinkled scolds with hands on hips,

Girls in bloom of cheek and lips,

Wild-eyed, free-limbed, such as chase

Bacchus round some antique vase,

Brief of skirt, with ankles bare,

Loose of kerchief and loose of hair,

With conch-shells blowing and fish-horn's twang,

Over and over the Mænads sang,—

"Here's Flud Oirson, fur his horrd horrt,

Torr'd an' futherr'd d an' corr'd in a corrt

By the women o' Morble'ead!"

Small pity for him!—He sailed away

From a leaking ship in Chaleur Bay,—

Sailed away from a sinking wreck,

With his own townspeople on her deck!

"Lay by! lay by!" they called to him.

Back he answered, "Sink or swim!

Brag of your catch of fish again!"

And off he sailed thro' the fog and the rain.

Old Floyd lreson, for his hard heart,

Tarred and feathered and carried in a cart

By

the women of Marblehead!

Thro' the street, on either side,

Up flew windows, doors swung wide;

Sharp-tonged spinster, old wives grey,

Lent a treble to the fish-horn's bray.

Sea-worn grandsires, cripple-bound,

Hulks of old sailors run aground,

Shook head and fist, shook hat and cane,

And cracked with curses the hoarse refrain;

"Here's Flud Oirson, fur his horrd horrt,

Torr'd an' futherr'd an' corr'd in a corrt

By the women o' Morble'ead!"

"Hear me, Neighbours!" at last he cried,—

"What to me is this noisy ride?

What is the shame that clothes the skin

To the nameless horror that lives within?

Waking or sleeping, I see a wreck,

And hear a cry from a reeling deck!

Hate me and curse me,—I only dread

The hand of God and the face of the Dead."

Said old Floyd Ireson, for his hard heart,

Tarred and feathered and carried in a cart

By

the women of Marblehead!

Then the wife of the Skipper lost at sea

Said, "God has toucht him!—why should we?"

Said an old wife mourning her only son,

"Cut the rogue's tether and let him run!"

So with soft relentings and rude excuse,

Half acorn, half pity, they cut him loose,

And gave him a cloak to hide him in,

And left him alone with his shame and sin.

Poor Floyd Ireson, for his hard heart,

Tarred and feathered and carried in a cart

By

the women of Marblehead! |

|

|

Mr. Whittier has many admirers in this country, to whom this volume will be welcome. |

|