|

Although this would cause much distress to those who relied

on the mill for their sole employment, the fire was regarded as

a saviour from weary toil by many children and adolescents who

worked there as operatives. Indeed, at another fire at the

mill in January 1842, it was reported that it was:

Very discouraging ... to see the poorer class of persons of

Tring standing by and viewing the progress of the enemy with

apparent satisfaction ... which was scarcely to be wondered at

when the system was known to be productive of the subversion and

destruction of all that is moral and useful in the female part

of the labourers therein ... labour is so inadequately paid for

that young women from 16 to 20 years old do not obtain for a

long day's work more than from 4d to 6d per day.[2]

This did not please David Evans, the owner, who wrote at once

to reply that young women who understood the trade could and did

earn from 5s to 7s 6d per week. He added, sharply, that it

would be admitted by those most conversant with the estate of

Tring itself that its morals were better now than they were

before the establishment of the mills.[3] A few local

residents supported his remark, commenting that, whatever might

be the individual opinions as to the working of the factory

system in general, it would not be easy to find a factory in the

country that was not better run, or where the employees were

altogether more satisfied.[4] The 'progress of the enemy' at the

first conflagration was viewed with special delight by the child

operatives. Ragged and shivering in the cold and sleet,

they watched as the destruction of their hated workplace

promised a release from the deafening noise of machinery, the

heat, and the all pervasive smell of oil. At that exciting

time there was no immediate thought given to the effect the loss

of their meagre wages would have on their families.

Ten years before this, on the 19 December 1826, William

Massey was married to Mary Rooker, in the Church of St Peter and

St Paul, Tring.[5] Tring was then a small country market

town having a population of some three thousand, with mechanical

industry limited to silk throwing, brewing, and flour milling.

William was an illiterate labourer and boatman, relying

constantly for his sometimes uncertain periods of work on the wharfingers and Tring Wharf flour mill, situated by the side of

the Wendover Arm of the Grand Junction Canal. Mary had a determined nature, a

more refined mind, and could even read and write a little, to a

low average attained then by most of the poor. The home

they set up together on Gamnel Wharf was rented from William's

employers, probably William Grover & Sons, Millers and

Wharfingers, for a shilling per week.

For this money they were given a

flint cottage in a row of four flint cottages and four houses,

that included good gardens. Their cottage was next to a house

rented by Elizabeth ('Mam') Rowe that was used also as a small

dame school. [5a] Having

paid the rent, nine shillings remained from William's weekly

wage to provide a minimum subsistence. This was tolerable

until the family started to increase, and William's idea of

bliss was to indulge in the occasional gallon of beer.

Thomas Gerald was their first child, born on Thursday, 29 May

1828, and was followed by Edwin, Frederick and Henry at

approximately three yearly intervals. Because of his

parents' increasing responsibilities and living costs Gerald was

sent when he was eight, in common with many other local

youngsters of a similar age, to wage earn as a throwster at the

silk mill. Filament silk was prepared for weaving by

'throwing' or twisting the thread in varying degrees to the left

or right. Each twist was called a turn, with more turns

per inch tightening the thread. The four main stages in

throwing were winding, doubling two or more threads, twisting to

increase the number of turns, and skeining. The skeins

were then soaked to make them more pliable, dried, and reeled on

to bobbins. Tram, organzine and crepe were the most used

types of thrown yarns.

By Act of Parliament in 1833 the employment of children less

than nine years old was prohibited, and from nine to thirteen

years restricted to forty—eight hours per week. Although

civil registration of births and deaths became operative from

1837, it was not until 1875 and a fine of £2 for

non—registration that this could be enforced. Until then

many parents had of necessity to lie about the ages of their

children. Gerald therefore was up at five in the morning

for six days a week, reminded by the mill bell at half—past—five

in case he had overslept, returning home at six—thirty in the

evening. Half—an—hour was allowed for dinner, that the

operatives brought with them from home, and two short breaks

permitted for 'drinking time'. For his first week's work,

Gerald received 9d, or 4p in today's coin, but in attempting to

increase his wages by the easier method of pitch—and—toss, he

lost it all before he arrived home that day. In recounting

the incident to a reporter many years later, he admitted to

having been an inveterate gambler in his young days, but did not

record any comments that his parents must have made.[6]

|

Pleasantly rings the Chime that calls to

Bridal—hall or Kirk;

But Hell might gloatingly pull for the peal that

wakes the babes

to work!

'Come, little Children,' the Mill—bell rings and

drowsily they run,

Little old Men and Women, and human worms who have

spun

The Life of Infancy into silk; and fed, Child,

Mother and Wife,

The Factory's smoke of torment, with the fuel of

human life.

O weird white face, and weary bones, and whether

they hurry

or crawl,

You know them all by the Factory—stamp, they wear it

one and all.

(Massey) |

A short account of work in Tring silk mill in 1858

experienced by an eight year old girl, confirms the bell's

imperious call of 'Come to the mill' at half—past—five.

But at that time, being under the age of eleven, she had only to

work half days; during the remainder of those days she was

supposed to be attending school. After the age of eleven

she was of necessity working a twelve—hour day for wages of 2s

6d per week.[7]

Compared with Gerald's counterparts in the heavily

industrialised areas of Britain, the workers at Tring mill were

well treated. From contemporary accounts by workers and

from official reports of the time, many factory operatives,

particularly in the Midlands, were subjected to degradation,

brutality and grossly excessive hours. The Sadler

Committee, appointed to collect first hand evidence on

conditions in factories, discovered extraordinary cases of such

maltreatment combined with social privation. A tailor's

three daughters aged 12, 11 and 6 years worked in a worsted mill

near Leeds. During the busy time, six weeks in the year,

they were at the mill from 3 a.m. until 10 p.m. with a quarter

of an hour for breakfast, half an hour for dinner, and a quarter

of an hour for 'drinking'.[8] Overseers with a cruel

disposition would make the children's life a misery, beating and

flogging them for the slightest inattention to their work.

One young girl of nine was beaten for going to the toilet.[9]

It was not until 1847 that legislation was able to be enforced,

albeit slowly, to end the exploitation of child labour.

Mary tried her best, despite the family's poverty, to

inculcate the decencies in her children. Being religiously

Calvinistic, Sunday School was an essential part of their

upbringing. Devotional pamphlets were brought to homes by

local preachers, and old copies of the Bible, the

Pilgrim's Progress and the religious Penny Post were

distributed. Gerald was sent first to a 'penny school'

that may have been held in the Baptist Chapel, New Mill (known

as the New Mill Sabbath School in 1833), located near the wharf,

and later to the National School in the town. Although he

learned to read well, he achieved little else. In common

with most youngsters he was made to memorise chapters of the

Bible; he also assumed as true the allegories of John Bunyan,

and accepted as fact the statements set out in Wesleyan tracts.

At that early age he showed an appreciation for music and had a

good singing voice. His parents were proud to take him to

chapel to show his ability in the choir, although to be seen and

heard properly, being of short stature, he was made to stand on

the pew.[10]

While the silk mill was being repaired following the fire, it

was necessary that Gerald's earning power that had reached 1s 3d

per week, be redirected. Next to silk manufacturing, the

main occupation in Tring was straw plaiting. This also was

a children's employment, taught often to those as young as three

years. By early school age, youngsters who could not plait

the minimum three straws were regarded as being very dense.

Parents commonly taught plaiting at home, or the children were

sent to plaiting schools, that were sometimes no more than a

large cottage room. A good, usually adult worker could

make thirty yards of plait a day, although it took about twelve

hours work each day to earn between three and four shillings a

week. The plait was then sold to local dealers to be made

up into hats, bonnets, or dress ornamentation.[11]

Gerald found this new labour to be equally as oppressive and

financially unrewarding as silk throwing. During the few

years he worked at plaiting, he suffered several attacks of

fever, which was common to the inhabitants of that low—lying

area. At one time the whole family lay prostrate, too weak

even to obtain a drink or get help from neighbours. When

William was out of work, the family income could be as low as 5s

9d per week, the cost of one course of a meal on a rich man's

table.[12]

Those harsh conditions which were testified in press and

official reports between the 1830s and 1850s, gave many literate

working men the impetus to make an initial step towards active

social radicalism. Of his own environment, Massey

commented:

Having had to earn my own dear bread by the cheapening of

flesh and blood thus early, I never knew what childhood was.

I had no childhood. Ever since I can remember, I have had

the aching fear of want, throbbing in heart and brow. The

currents of my life were early poisoned ... I look back now in

wonder, not that so few escape, but that any escape at all ...

so blighting are the influences which surround thousands in

early life, to which I can bear such bitter testimony.[13]

By 1841 the family had moved temporarily to Fleet Street,

West End, off the present day Chapel Street, near the centre of

Tring. Their wharf home may by then have become

uninhabitable. After three years working at straw

plaiting, Gerald obtained a domestic post at a local boarding

school in Market Street.[14] But he had not worked there

long before he was sacked because, as he recounted later, the

girls used to hug and kiss him![15]

It was about that time, approaching the age of fifteen, when

he realised that none of his strongly progressive but yet

ill—defined hopes would be achieved by staying in Tring.

Being uneducated, he had no prospect of obtaining employment

other than returning to the silk mill, or continuing in inferior

and uncertain positions. Hence, during late 1843 or early

1844 he decided to chance his fortune in London.

|

O mighty mystery London, there be Children still,

who hold

Her Palaces are silver—roofed, her pavements are of

gold;

And blindly in that dark of fate, they grope for the

golden prize

For somewhere hidden in her heart the charmèd

treasure lies.

(Massey) |

It was in 1843, when he was depressed and probably thinking

about leaving for London, that he said his first poem on 'Hope'

had been accepted by the Aylesbury News.[16]

Provincial papers received poems submitted by local writers and

published them either with signature, or anonymously.

These were included with poems by better known names such as

Ebenezer Elliott and Eliza

Cook that often indicated the political stance of the paper.

The Nelson Column, c. 1860 (Print by T. Nelson

& Sons.)

|

|

|

Cloth

Fair , near the Barbican. |

If he had saved his wages for a few weeks

Massey could have made his move to London probably by one of

several horse coach services that passed through or commenced at

Tring. On entering London via the Edgware Road, these

travelled along Oxford Street, 'the road to Oxford', and on to

one of the several coaching inn termini in the City area.

'The Old Bell', Warwick Lane, 'Clemet's Inn', Old Bailey, and

the 'King's Arms', Holborn Bridge were used on the Tring run.

Alternatively, and more likely, he could have secured a lift on

a Carrier's cart, travelling along the same route. From

old prints of the period, the London streets were as busy then

as they are today. Pedestrians had to be agile when

crossing main roads to avoid being knocked down by one of many

horse carriages and carts. Hawkers, street vendors,

crossing sweepers and prostitutes were continually occupied.

Years of division between rich and poor was immediately

noticeable, and formed one of the long—standing basic causes of

radical discontent. Oxford Street, although shabby,

separated the more wealthy class to the north from the slums of

St Giles and Spitalfields to the south and east. Trafalgar

Square, a haven for vagrants, was soon to have its Nelson

Column, to be followed later by the lions. Smart Regent

Street was proud of its covered colonnade, though the

shopkeepers had to keep an eye open for thieves and pickpockets

for whom it was a profitable attraction. Away from the

more select areas, the pervasive evidence of inadequate sewerage

systems was made clear to all, particularly in the densely

populated labouring districts. A civil engineer,

commenting on the parish of St Giles, referred to houses whose

yards were covered with sewage from the overflowing of privies.

In Westminster, cellars were flooded by sewage water.[17]

Before the construction of New Oxford Street and Endall Street,

the area around St Giles known as the 'Rookery' was one mass of

garbage and stagnant gutters, bordered closely by dilapidated

and overcrowded dwellings.[18]

|

|

|

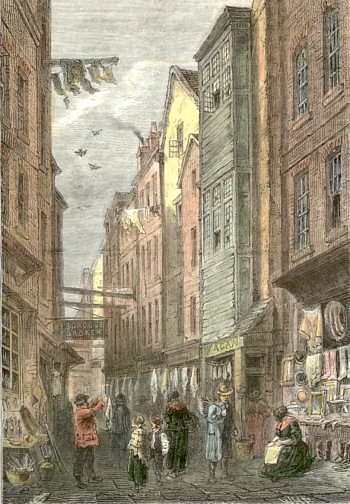

Field Lane, c. 1840. (Old and New

London) This (now part of Shoe Lane) ran

from Holborn to Saffron Hill, and was an area

favoured by thieves for the sale of their stolen

goods, particularly handkerchiefs. Some of

these can be seen in the picture, hanging outside

shop windows. Charles Dickens had recorded the

street in his Oliver Twist (1837). |

|

|

|

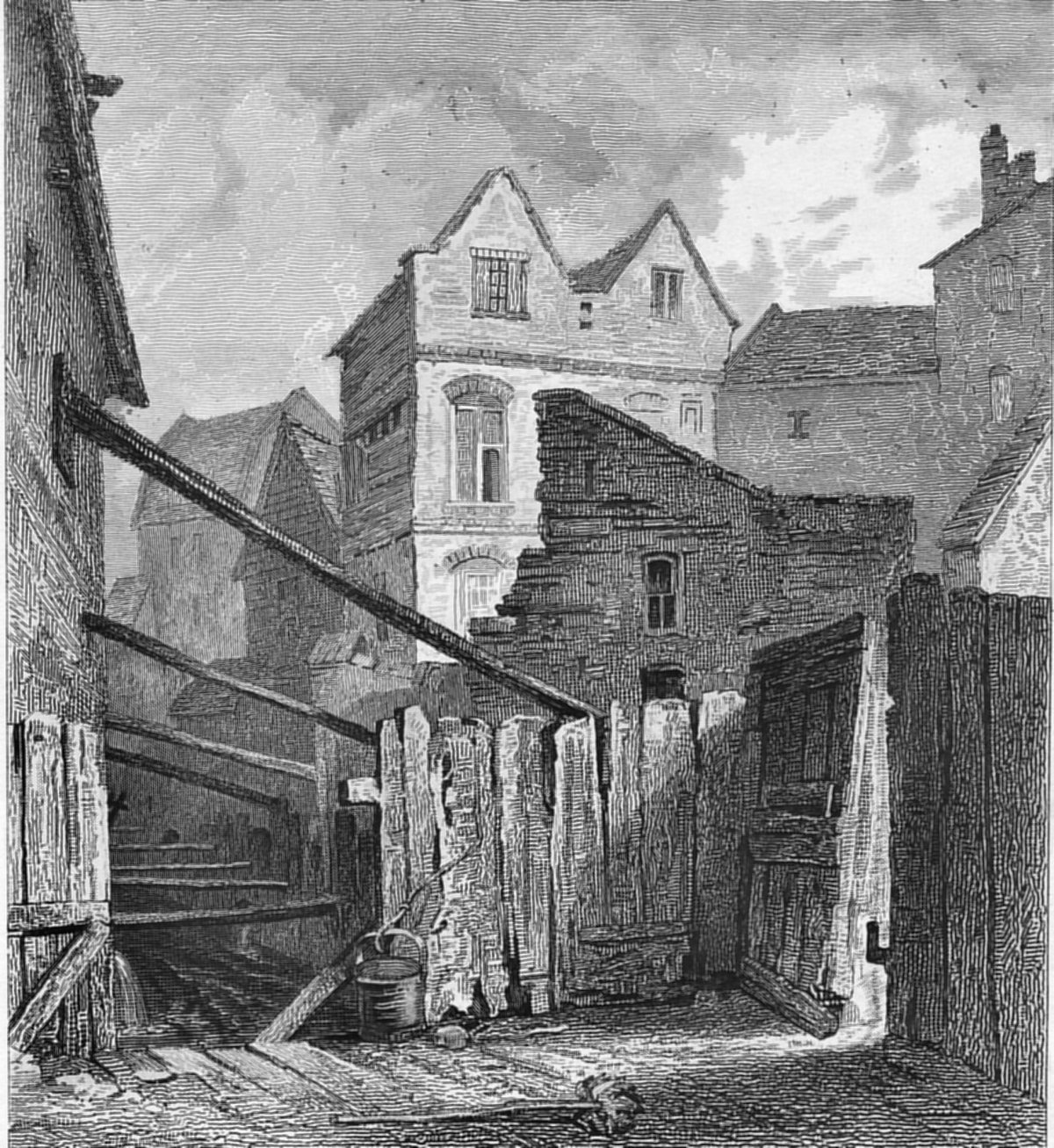

Near

Field Lane c. 1844

Houses with the open part of the Fleet Ditch before

rebuilding

(Print: D. Bogue, Fleet Street) |

|

|

|

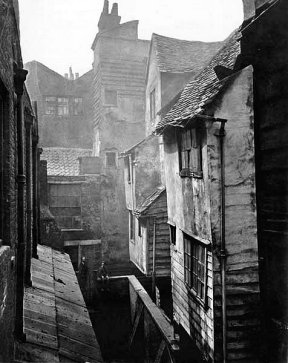

A Clerkenwell interior.

(London Shadows, 1854) |

The cause of cholera outbreaks had not then been medically

determined. Some thought it was connected in some way to

vapours emanating from those areas, and a doctor considered

that:

". . . . It is strictly an epidemic . . . prevailing most in

those localities of a town where the drainage is most defective,

and where, at the same time, the population is most destitute

... it is not infectious, nor admitting of being controlled by

any of the means that are reputed to exercise a power over

infectious diseases . . ."[19]

Similar to St Giles were the areas 'Jacob's Island', in

Bermondsey, and Saffron Hill, between Leather Lane and

Farringdon Road. These were also brought to life in

Dickens' Oliver Twist, and the original film of that

name. Jacob's Island was described by Dickens in the 1830s

as being full of 'Crazy wooden galleries ... with holes from

whence to look on the slime beneath ... rooms so small, so

filthy, so confined, that the air would seem too tainted even

for the dirt and squalor which they shelter'.

Clerkenwell's water supply was thought to contain water draining

from Highgate cemetery and other burial grounds and cess pits in

the area. In an account of two cholera cases:

...it was afterwards found that the cellar of the house in

which the patient resided had been burst into by a cesspool;

whilst in the other, a fine, stout, healthy man, lived at the

back of a graveyard, the mouldering remains of the dead were

level with the window—sill in the parlour in which he was

constantly living . . .[20]

Even the Thames was so fouled that the stench on one hot

summer's day forced the adjournment of the House of Commons.

Poverty, squalor and cruelty; each was co—existent on the other.

The cruelty was apparent in the markets, especially Smithfield,

and in Spitalfields, the home of the silk weavers. They

were noted bird catchers and suppliers of singing birds, which

they often blinded with hot wires, as it was considered to make

them sing better. In his later years, Massey wrote a poem

for his granddaughter, after telling her of that cruel custom:

|

Listen, my little one, it is the lark,

Captured and blinded, singing in the dark.

His nest—mate and his younglings are all dead:

Their feathers flutter on some foolish head.

Of some lost Paradise, poor bird, he sings

Which for a moment back his vision brings: ...

He sings his fervid life out day by day;

Imprisoned in an area underground ...

As if with floods of music he would drown

The dire, discordant roar of London Town.[21] |

Massey's previous connection with the manufacturing of yarn

may have helped him to obtain his first post as a draper's

errand boy. Because of a rise in the amount of

manufactured cotton at that time, retail outlets had increased,

giving rise to greater competition between these shops.

Drapers, tailors and haberdashers in the main thoroughfares had

therefore to be smart in appearance. Many of the shop

assistants, sharing a cramped and often unsanitary room over the

premises, were up early in the morning, cleaning, polishing and

arranging displays. Gas lighting flared brilliantly

through plate glass windows, displaying carefully arranged bolts

of cloth, yarn and made up materials. Brass fittings on

the counters shone to perfection. Errand boys, in whatever

type of shop they were employed, were kept very busy, often

working a fourteen—hour day. The majority of customers

required their goods to be delivered, some to quite a distance,

and within that same day. The errand boy had therefore to

carry a large number of parcels to varying addresses, which

could cover a wide area. He then returned to the shop for

further deliveries, or to clean until further items were

ready.[22]

As Massey's arrival point in London was near to High Holborn,

which had a number of woollen and other drapery shops, it is

possible that this was the area in which he found his first of

several jobs. He made no mention of the name of the shop,

although he indicated that it was not small, having several

staff and a supervisor. In spite of the long hours, that

was the opportunity for which he had been longing for several

years. 'Now I began to think that the crown of all desire,

and the sum of all existence, was to read and get knowledge.

Read, read, read! I used to read at all possible times,

and in all possible places; up in bed till two or three in the

morning — nothing daunted by once setting the bed on fire.'[23]

Being continually short of money, he used to read from books in

the numerous street bookstalls, probably even using his

employer's time while travelling on errands. When he was

out of work, he often went without a meal to purchase a book,

and self—education became a constant obsession. English,

Roman and Greek history, French tuition books and the

instructive Lloyds' Penny Times built on the foundation

of his earlier meagre schooling. Everyday encounters with

people, and observations of the stratified social setting

initiated critical reasoning concerning fundamental social

anomalies. In particular, the oppressive injustice between

the position of master and servant that he viewed and endured,

focused and sharpened his investigations to that area. In

common with most forthcoming young radicals of the time, he

found the causes of iniquity, political, social and religious,

defined in the writings of Thomas Paine, William Howitt, and the

French Republicans Constantin de Volney and Louis Blanc. Publication of Paine's

Rights of Man and Richard Carlile's The

Age of Reason in the early 1800s had resulted in Carlile's

imprisonment for sedition and blasphemy. The Chartist leaders

used Paine's works as a theory of reference in the formulation

of their principles. Volney's Ruins: or a Survey of the

Revolutions of Empires, and New Researches into Ancient History,

stressed Republican ideas and Biblical questioning, as did Howitt's

A Popular History of Priestcraft. Louis Blanc

emphasised the division between capital and labour in The

Organisation of Labour in and his periodical the Monthly Review,

in the late 1840s. Those and similar works were read by working

class radicals against a background of social privation,

injustice and unrest. Under those circumstances it is

understandable that the political system that caused such

inequality should result in a powerful call for democratic

reform. Thomas Carlyle had written, 'Chartism is one of the most

natural phenomena in England,' and this statement remained

evident until the early 1850s and the movement's rapid decline.

Massey entered a turbulent political scene dominated by Sir

Robert Peel's Conservatives who were facing trade recession, the

Anti—Corn Law League, and Chartism. There were two main causes

of unrest at that time. First was the outcome of the Reform Act

of 1832. Although this allowed more people to vote, it

introduced minimum property and rental restrictions, thus

effectively disqualifying many working men who were previously

entitled to vote. The second was the Poor Law Reform Act of 1834

that increased the number of workhouses to end the cost of

parish relief given to needy individuals. It was hoped that

policy would make the poor more thrifty, and encourage them to

seek work in industry. But the segregation of men, women and

children, together with strict discipline in harsh conditions

caused much opposition. This was particularly evident in the

early 1800s when young workhouse inmates were transported from

cities as 'apprentices' to even worse conditions as cheap labour

in country factories.[24] The Anti—Corn Law League was founded

in 1839 from the Association's Manchester headquarters. The Corn

Laws of 1815 had prohibited the import of wheat until the home

price reached 80s per quarter. Despite a sliding scale

introduced by the government in 1828, the League blamed the laws

for raising the price of food.

The Chartist movement with which Massey came into particular

contact was a force that had a long history due to social

unrest. Its roots lay in the radical London Corresponding

Society, founded in 1791 for working men, and gathered strength

through successive organisations, the most powerful of which was

the London Working Men's Association. This organisation was

founded in 1836 by William Lovett who, with John Roebuck MP, was

responsible for drafting the 'People's Charter' published in

1838, giving recognition to the term 'Chartist'. The Charter

consisted of a programme of political reform that had six main

points: a vote for every man over twenty—one; vote by ballot; no

property qualifications for MPs; equal electoral districts;

payment of members of Parliament and annual election of

Parliament. By these points it was hoped that power would be

given to the working classes that had been denied to them by the

Reform Act.

During his first years in London, Massey had not forgotten the

success of having his first poem printed which, he said, had

been due to him falling in youthful love. Prior to that he never

had any fondness for poetry, and skipped over verse when he came

across it in books. From that first experience his emotions

developed with particular sensitivity to form and colour; he

delighted in the countryside with its flowers and wildlife; was

entranced by golden tints of sunlight shimmering through the

trees. The contrasting streets of London induced feelings of

nostalgia for the countryside he had left and, to compensate,

between work and study he found time to compose more poems that

he compiled and published by subscription in Tring. The private

printing by Garlick of Tring in 1847 of Original Poems and

Chansons by Thomas Massey was priced at one shilling and,

surprisingly, was reported to have sold 250 copies locally, but

no copy has been traced (Appendix

A). The title was suggested to him by the French Republican,

Pierre de Béranger, who had been imprisoned twice for his

political verse. His Chansons de P. J. Béranger was

published in English in 1837.

After some time served as an errand boy in various shops, Massey

was promoted to attend behind a shop counter that brought him

into closer contact with a particularly arrogant and strongly

disliked supervisor. Having a lively sense of humour, Massey

could not help making jokes to the other staff, impersonating

this person's self—importance. Unfortunately, following a

particularly pungent jest, this came to the ears of the

supervisor who immediately bundled an unrepentant Massey,

together with his belongings, into the street. The shop may have

been Swan & Edgar, the large draper's store that was sited at

the corner of Regent Street and Piccadilly.[25]

London in the 1840s was a centre for meetings, lectures and

oratory, particularly in the broad sphere covered by the term

'radicalism'. There were protests against the Corn Laws, support

for Robert Owen's socialism with its anti—Christian overtones,

and publicity for advocates of temperance. Of greatest

importance were the Chartist meetings. These were held in local

halls, such as the National Hall, High Holborn. The Metropolitan

Delegate Council of the National Charter Association met weekly

at the City Chartists' Hall in the Barbican, and smaller

meetings were held in coffee houses. The Charter Coffee

House, High Holborn, Denny's Coffee House, Seven Dials, and the

London Coffee House, Ludgate Hill, were popular. The

Arundel Coffee House in the Strand was hired by the Chartist

National Convention.[26] Educational

and political lectures were held at the Hall of Science, 58 City

Road, which moved, following termination of lease in 1866, to

142 Old Street, and became the headquarters of the National

Secular Society. The equally prestigious Social, Literary

and Scientific Institution, at 23 John Street, Fitzroy Square,

was used also by many radicals. This building had opened

as such in 1840 — thought originally, and from an engraving, to

have been a chapel — and was replaced a short distance away by

the Cleveland Street Hall in 1861. Many of the Chartist

leaders lectured in these and similar halls in the suburbs,

particularly Feargus O'Connor, editor of the Northern Star,

and Thomas Cooper, following

his two years' imprisonment for sedition in 1843. From

reading Massey's earliest works, it

is obvious that he attended many of those meetings and lectures,

which influenced the idiom of his written and oral styles.

The radical press had an equally great effect on him,

particularly the Northern Star that had the young,

ultra—radical George Julian Harney as sub—editor.

It was the year of 1848 and the final stand of Chartism that

had the most profound effect on Massey, and which was to

determine the direction of his life for the following five

years. The repeal of the Corn laws the previous year had

diverted more attention to Chartism. Increasing

unemployment gained it more supporters, as did the general

election when O'Connor was elected for Nottingham and Harney

opposed Palmerston for Tiverton. In February it was heard

that King Louis Philippe of France had been deposed, and that

France had become a republic. Two national petitions for

the Charter had been made previously to Parliament, in 1839 and

1842, but without success. With events now appearing to

favour workers' rights, the Chartists hurriedly organised a

third, and plans were made for a national convention to meet in

April, and present the petition to Parliament. Protests by

the Trades' Meeting against unemployment, and by G. W. M.

Reynolds, a later Chartist leader, against income tax added even

more to working class unrest. Simultaneously there was an

increase of violence in several northern cities, with sporadic

outbreaks in London sufficient to cause extended police activity

and governmental concern. Queen Victoria was advised to

stay at the Isle of Wight until stability had been restored.

The meeting, during which the petition would be presented, was

held on the 10 April at Kennington Common, near the site of the

present Oval cricket ground, and was attended by about 100,000

people. Massey was present, and was nearly run down by the

police. Despite the failure of the petition, he said later

that it had a greater effect on him than anything previous in

his life. 'It scarred and blood—burnt into the very core

of my being.'[27] For his support of

the Chartists at that meeting, he was again sacked from his job.

There is no record when Massey became a member of the National

Charter Association, which was formed in 1840, but due to his

involvement in Chartist interests it probably dated to around

1848 or 1849 when he was twenty. Lecturers of radical

organisations travelled widely throughout the provinces, and

Massey undoubtedly met with a number of these speakers in

informal discussions when the merits of particular groups and

radical centres of activity were compared. Consequently,

he moved to Uxbridge where John Bedford Leno, a printer and

later branch secretary of the local Chartists, together with

some other local helpers had in 1845, started a Young Men's

Improvement Society. In 1846, then aged twenty, Leno was

promoter and joint editor of a manuscript newspaper the

Attempt, of which seven issues were produced up to 1849.

Massey immediately joined the Society, which had then a

membership of a hundred, and gave it considerable support.

Books and newspapers were bought from members' weekly

subscriptions, and gifts of reading matter readily accepted.

Massey donated seven books for their library, and wrote one

rigidly structured article for the Attempt. 'Shelley

and his Poetry', although unsigned, can be recognised by his

early, more copybook style handwriting.

Early in 1849 the Society decided to start a monthly printed

journal of literature and general information, the Uxbridge

Pioneer, to open 'a medium of communication between the

learned and ignorant' for the benefit of the working classes.

Massey, Leno and some other elected members of the Society were

appointed as editors, and the first issue, price 3d, was

published in February. A substantial amount of the

material was written by Massey, who signed himself as 'T.G.M.'

or 'Gerald', and some unsigned items can be identified also as

by him. 'A Few Words

on Poetry' shows lack of depth and maturity, but has a

colourful, metaphorical style. It is possible that he

regarded poetry as a form of escapism at that time when he wrote

that 'Poets seek a world of thought to live in, because the

world of reality is harsh and cold.' 'A

Romaunt of Ancient Woxbrigge' has a particularly jocular

form. A rich patriarch was extremely jealous of attention

given to his two daughters who, despite his care, became

pregnant. Intending to obtain his revenge on the man

responsible, he pretended to go away on a journey, but hid near

the house until evening. On noticing a length of knotted

scarves coming from his daughters' bedroom window, he held on to

the end, and found himself pulled rapidly upwards. The

daughters, in shock at meeting this unexpected face, released

the scarves, which resulted in the demise of their tyrannical

father. In 'May

Dawson' Massey wrote on the perils of London prostitution.

That was probably a mainly fictional item, taking the form of a

personal encounter in London with a young Tring girl who had

been seduced, and who later committed suicide. An unsigned

editorial 'To Our Readers'

has Massey's style, and contains some lines from later published

poems.

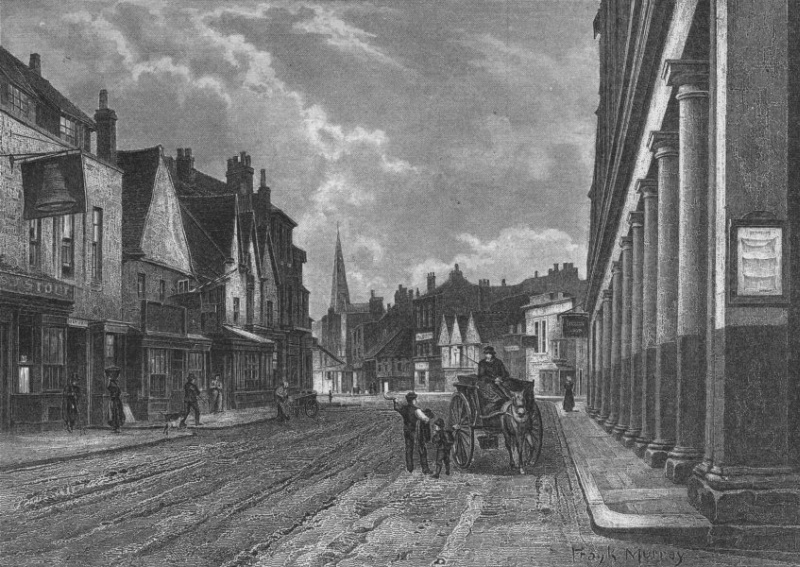

Uxbridge High Street.

Shortly after publication, political differences alienated

the more radical Massey and Leno from the other editors. A

letter received, and published in the second issue, mentioned 'T.G.M.'

in particular, and referred quite obviously to his 'Woxbrigge'

and 'May Dawson' articles:

I will not quote the passages from the Pioneer, which to my

mind are highly objectionable ... I find they occur in papers

bearing the same initials; and I cannot but regret that the

alternate blush of the reader should suffuse his cheek, the

moment after his mind has been charmed with the germs of

elegance and vigour which characterize the style of their author

... a little more moral precision, and he will 'write to

profit'. I trust ... a second number ... may be with

safety and profit placed in the hands of the younger members of

our families.[28]

Massey and Leno, together with colleagues Edward Farrah and

George Redrup became increasingly opposed to the policies

advocated by other active members of the Society.

Accordingly they decided to commence in April a paper to counter

the Pioneer. With the assistance of some political

sympathisers they raised fifteen shillings with the promise of

one shilling per month from each, to finance continuing issues.

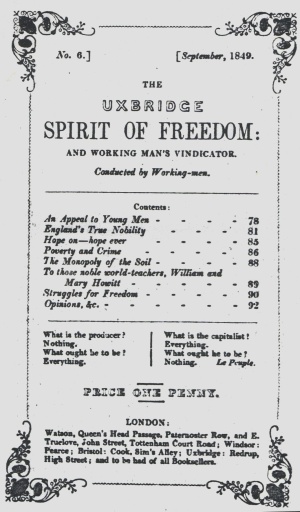

A thousand copies of the first issue of the Uxbridge Spirit

of Freedom and Working Man's Vindicator conducted by Working Men,

price one penny, was offered for sale on Thursday market day.[29]

To promote their paper with the minimum of cost, some

pretentious publicity was devised by Massey for the occasion.

Having obtained an imitation uniform of the republican Paris

civil corps, he persuaded Leno's brother to dress in this

uniform, march around the town, and help to sell the paper.

This proved to be sound advertising, and the paper's many

treasonable contents were certainly noted by its readers.

There was a predictable mixture of agreement from the workers,

dissent from the more affluent Tory townspeople and condemnation

from the vicar's pulpit (in the name of God) the following

Sunday.[30] In their introductory

editorial Massey and Leno had stated clearly their intent to

'Call a man a man, and a spade a spade'. An ironmonger

responded by placing a shovel outside his door with 'This is a

spade' written on it, and a baker changed the title of the paper

to the 'Spirit of Mischief: or Working Man's Window Breaker.'

That publicity ensured the sale of 900 copies, sufficient for

the young#editors to judge the venture a moderate success. After

seven issues Massey reported that the sales had doubled.[31]

The Uxbridge Spirit of Freedom

(Columbia University Library, Seligman Collection)

The majority of radical papers published notices of similar

publications, and it was the Northern Star that gave the

most comprehensive reviews of the Uxbridge Spirit of Freedom

throughout its nine monthly issues.

The following review of the first edition of the Uxbridge

Spirit of Freedom appeared in the Northern Star, 4th

April 1849:

"Uxbridge Spirit of Freedom, and Working Men's Vindicator.

Conducted by Working Men. No. 1. April.

Published by J. Redrup, Uxbridge, Middlesex. London: J.

Watson Queen’s Head—passage, Paternoster Row.

A NEW monthly publication, of thoroughly democratic character

conducted by Working Men. We shall let our friends speak

for themselves :—

We shall be accused of class—feeling, and party

spirit; well, be it so. We would fain clasp the whole

world in the arms of love: but ye will not, ye who spit upon us

and flout us with being the “swinish multitude.” What can

be the nature of that union where the subjection of the one

party is maintained by the force of the other? This is

treason to the sovereignty of the people, and treason to God, by

destroying that moral beauty of unity which the creator intended

for mankind. We are slaves socially and helots

politically: and if to work out our own redemption be called

“party feeling,” we accept it. We call upon true democrats

of all ranks to support us: but especially on the working class:

we invite them to contribute to our pages, for we want the

sledge hammer strokes which working—men who do think can give,

and, if we cannot reach the head of the present system of

things, why we’ll let drive at the feet! Keep at work, and

the mighty Triune which crushes us now, shall, ere long, make

way for an educated and enfranchised people, who shall yet make

Old England a land worth living and worth dying for.

Such a publication appearing in Manchester or Leeds would be

nothing wonderful: but we must say we are agreeably surprised to

find a small town like Uxbridge containing men who not only dare

think for themselves, but who also, are determined to give their

free thoughts utterance, with the view of hastening the

political and social emancipation of their order. Such men

claim our respect and good wishes: and most earnestly we wish

them success. The whole of the article in the number are

well written: their titles are significant – “The Labour

Question”, “Letter of a Labourer,” “Emigration and the

Aristocracy,” “Where is Religion to be found?” &c., &c. We

must make another extract from this boldly—written “Vindicator”

of the rights of the proletarians:–

We have to play a grand part in the history of

the future. Our gallant brothers of Paris, Vienna and

Berlin, must not bleed on the barricades for Labour’s rights in

vain. The problem will again and again force itself on the

world, and, if our rulers dare not grapple with it, we must do

the work ourselves. Working men, we must understand each

other – let us learn what wrongs have been perpetrated, for that

is the first step towards redress. We must, ourselves,

assert our rights or we shall never win them. We have been

listeners in the political arena – now let us mount the

platform.

The Schoolmaster is abroad. Let the enemies of Justice

look to it. Work on ye 'MEN OF THE FUTURE' .

The local Bucks Advertiser, commenting later on the

paper, referred to it as juvenile but daring, adding that 'We

take the liberty of suggesting that a good deal of what they

write does not look as if it came from men of temperance and

peace. The principles are sound and true, but we don't

think it worth while to commit sedition in order to expound

them. . . '[32]

The Northern Star, reviewing the second issue, noted

an increase of four pages, and favoured Massey's 'first—rate

poetry.' It gave also, in issues through to December, the

titles of a number of articles in each issue. These

indicated strongly the paper's political stance: 'To the Thieves

and Robbers of both Houses of Parliament', 'The Poor and the

Rich', 'Why has the cause of the People not triumphed?' and

'What have the Clergy been doing?' The Northern Star

emphasised these and other progressively heretical titles by

quoting part of an article by John Rymill of Nottingham, who had

pronounced scathingly:

Is it not monstrous that an age which permits a handful of

antiquated lords to eat up the soil, and a swarm of red and

black coated thieves to swallow up the taxes; an age in which

England's true nobility have to starve in the midst of plenty,

in order that certain useless things called lords, dukes,

esquires, and reverends, may be fed on dainties, and be clothed

in crimson; an age in which poor paupers are worse clad, and

more scantily fed than criminals . . . is it not monstrous,

I say, that such an age should be sanctified with the name of

civilization![33]

The majority of Chartists held those opinions of the clergy,

nobility and royalty. The established church, politically

conservative and against any further extension of the suffrage,

had an annual income of some nine million pounds, which was

termed 'pious robbery' by the Chartists. Bishops and other

leading church ministers had Tory connections that indicated

that they worked solely for money, while the working clergy had

little interest in working class social conditions.[34]

Nobility and royalty were condemned for living in idle

dissipation, while the working classes starved. The

Court Journal recorded detailed descriptions of grand state

balls and banquets held in Buckingham Palace, in some depth:

The range of tables displayed a gorgeous assemblage of gold

plate ... massive centre pieces, candelabra, vases, wine coolers

... flowering plants in golden vases... On the buffet

surrounding the centre shield were ranged vases, cups, chalices,

tankards, and salvers in profusion, some of them glittering with

precious stones, others enriched with exquisite carvings ...

A bill of fare in French, included turbot, turtle, prawns,

fillets of sole, peacock, pigeons in aspic, smoked salmon,

braised beef, ham, haunches of venison and other luxuries. In a

bitter but well meant contrast, the chef of the Reform Club

suggested improvements for the soup that was provided for the

inmates in charitable institutions. This could be made in

thousand gallon quantities, distributed to the poor once or

twice a day, and cost no more than two or three farthings a

quart.[35] These and similar items were

reported over the years with scorn and condemnation by the

Chartist press, and noted with resentment by readers. G.

W. M. Reynolds commented on the building in Hyde Park that had

been put up in preparation for the 1851 Great Exhibition.

He had reason to refer to an 1844 file of the Weekly Dispatch

that gave an almost Christian account of the interment in 1840

of Queen Victoria's favourite spaniel, Dash. An expensive

marble monument ordered by Prince Albert had been erected over

its resting place. Reynolds asked what readers thought of

that, when a poor working man's widow reflects upon the pauper

funeral of her husband. The coffin knocked up with a few

thin boards and old nails; the hurried ceremony; the heartless

apathy exhibited by the undertaker who contracts for the parish;

and the turfless grave on the 'poor side' of the churchyard.

He concluded, 'But a foreign Prince, for whom British industry

is taxed to raise him from a state of German pauperism to a

condition of English aristocratic opulence, can do all this with

impunity.'[36] The Uxbridge Spirit

of Freedom received support from

W. J. Linton, engraver,

Chartist sympathiser and editor in 1839 of the National: a

Library for the People, and

Thomas Cooper was pleased with the first number he received.

Throughout his time at Uxbridge Massey submitted during twelve

months from December 1848, a selection of his more roughly

lyrical and less radically contentious poems to the Bucks

Advertiser, some of which were published also in the

Uxbridge Spirit of Freedom.

Towards the end of 1849 Massey had come into particular

contact with two Chartist lecturers, Walter Cooper, a tailor by

trade, and Thomas Shorter, watch finisher.

Mr. Walter Cooper was born in Aberdeenshire in

1814, being brought up as a Wesleyan Methodist, and was employed

very early as a herd boy. His parents were very poor, and

he stated, "Many a time have we all been ill in bed together,

racked and parched with fever, each crying for water, and each

too weak to help the other; no medical aid was available, and no

friend or neighbour nigh to assist us. Hey, man! I shall

never forget the death of my old grandmother who loved me so

dearly; we had no fire in the house, and I had to nestle close

to her to give her some warmth while she shivered in the cold

clutch of death."

Whilst searching for employment in London in 1834, he got

married. He discovered before long that there was one

religion for the rich and another for the poor; that the same

distinction existed in a chapel as in a court of justice; that a

wide and impassable gulf separated the richly clad idler from

the hard—working labourer clothed in fustian. He found

that he had been religiously duped, deceived and misled.

Discovering the social and political wrongs endured by the

humbler classes, he became an eloquent and ardent debater at the

Sunday gatherings held in Smithfield Market.

A tailor by trade, he was thoroughly experienced in the miseries

attendant upon the slop and sweating system. When a child

was born to him, and he was willing but unable to obtain work,

he had no bed, no bedclothes, no food, and no fire. At the

same time he was toiling long and painfully over a pair of

trousers, for the making of which he was to receive seven—pence.

That caused him to become a stubborn denouncer of tyranny.

At the present time he is engaged in the management of the new

co-operative Association of Working Tailors, recently

established in Castle Street East, Oxford Street, London,

practically, and we trust successfully, illustrating the

principle he has long enunciated on the grand and all—important

question of labour. (Abridged from Reynolds's Political

Instructor, 16 March, 1850.)

In December, Cooper and Shorter informed Massey of a proposal

made by J. M. Ludlow to commence Working Associations that, they

hoped, would end capitalist owners' exploitation. Ludlow,

a lawyer and socialist, had been joint editor for the Rev.

Charles Kingsley's Politics for the People, and was

instrumental in starting meetings with workers in which social

views could be discussed. These received greater impetus

following reports by Henry Mayhew in the Morning Chronicle

of the conditions and poverty of, among others, the journeyman

tailors.[37] Kingsley's pamphlet

Cheap Clothes and Nasty, written under the name of 'Parson

Lot' just after Mayhew's exposure, owed much to Mayhew's report.

On 8 January 1850 at a meeting in London that included F. D.

Maurice, Thomas Hughes and Kingsley, it was decided to appoint

Walter Cooper as manager of their first association, the Working

Tailors' Association. A three-year lease was signed on the

18 January on a spacious building at 34 East Castle Street,

Oxford Street. This property was sited in a line opposite

the Pantheon, the main entrance of which was on the south side

of Oxford Street, next to Poland Street, the main entrance of which was at 359

Oxford Street. The Pantheon, previously a theatre, was

being used at that time as a bazaar and picture gallery.

Pantheon, Oxford Street, c. 1830.

Demolished in 1937 for a Marks &

Spencer store.

Walter Cooper then

invited Massey to take up the appointment of secretary.

During his editorship at Uxbridge, Massey had been sacked twice

from his job for using a candle late at night preparing copy for

the paper, and three times for the radical opinions that the

paper contained. This no doubt influenced his decision to

accept Cooper's offer and return again to London where, he

expected, there would now be a greater opportunity for the

expression of his radical idealism. |