|

[Previous Page]

ON

THE IMPORTANCE OF GENERAL EDUCATION,

AND THE MODES TO BE PURSUED

IN THE DIFFERENT SCHOOLS.

In endeavouring to point out the social and political importance of

education, and the necessity for establishing a better and more

general system than has hitherto been adopted in this country, it

will be advisable to begin by giving a clear definition of what we

mean by the term "education."

As it applies to children, we understand it to imply all those means

which are used to develop the various faculties of mind and body,

and so to train them, that the child shall become a healthy,

intelligent, moral, and useful member of society.

But in its more extended sense, as it applies to men and

nations, it means all those varied circumstances that exercise

their influence on human beings from the cradle to the grave. Hence

a man's parental or scholastic training, his trade or occupation,

his social companions, his pleasures and pursuits, his religion, the

institutions, laws, and government of his country, all operate in

various ways to train or educate his physical, mental, and moral

powers; and as all these influences are perfect or defective in

character, so will he be well or badly educated. Differences of character will be found in the same class, according

to the modified circumstances that have operated on each individual;

but the general character of each class, community, or nation

stands prominently forward, affording a forcible illustration of the

effects of individual, social, and political education. According to

the mental or moral instruction each

INDIVIDUALS may receive, will he be the better able to

withstand social taint and political corruption, and will, by his

laudable example and energy, be advancing the welfare of society,

while he is promoting his own. According to the intellectual and

moral spirit which pervades SOCIETY, will

its individual members be improved; and in proportion as it is

ignorant or demoralized, will they be deteriorated by its contact:

and as despotism or freedom prevail in a

NATION, will its subjects be imbued with feelings of liberty,

or be drilled into passive slaves.

Our present object is with INDIVIDUAL EDUCATION,

beginning with childhood; and if we can so far succeed as to

interest and induce others to assist in promoting this department of

education, the social and political education we have referred to

will be comparatively an easy task;—for if the rising generation can

be properly educated, in a few years they will give such a healthy

tone to society, and such an improving spirit to government, that

old prejudices, vices, and corruptions, must speedily give way

before them.

We have said, that education means the developing and training of

all the faculties of mind and body. By the faculties of

the body we mean the whole physical structure. By the

faculties of the mind we mean those powers we possess for

perceiving, acquiring, and treasuring up various kinds of knowledge;

for using that knowledge in comparing and judging of the properties

of things, and weighing the consequences of actions; for giving us a

love of justice, rectitude, and truth; for prompting us to acts of

benevolence, and delighting us with the happiness of others; for

appreciating the beauties of earth and heaven, and inspiring with

wonderment, awe, and veneration: in short, all those mental powers

which perceive, reflect, and prompt us to action.

By training or educating a bodily faculty is meant the means

used for accelerating its growth, and adding to its strength and

activity. For instance, a proper quantity of nutritious food, pure

air, warm clothing, and sufficient exercise are necessary to the

proper development or growth of a child; and if these essentials

are denied him in infancy, he will be stunted in growth, and

debilitated bodily and mentally; nor can any subsequent treatment

effectually remedy the evil. Nay, not only in infancy, but at every

period of our existence, are these conditions necessary to health

and strength. We might here adduce a great number of facts, to prove

the great physical injury sustained by infants and adults

among the poorer classes from bad or scanty food, impure

atmospheres, over exertion, and the evils attendant on ignorance and

poverty; but let one or two suffice. M. Villermé, an eminent

statician of France, has proved that there are one hundred

deaths in a poor arrondissment while there are only fifty

in a rich one; that, taking the whole population of France,

the rich live twelve and half years longer than the poor;

that the children of the rich have the probability of living

forty-two years and half, while the children of the poor have

only the probability of living thirty years. And the late Mr.

Sadler has shown that as many persons die in manufacturing

districts before their twentieth year, as in agricultural

districts before their fortieth. These alarming facts should

awaken the attention of the working classes in particular, and

should lead them to investigate the more immediate cause of

this lamentable sacrifice of life, and to devise some means by which

the evil may be remedied.

But we have talked of training as well as developing the

physical faculties. What we mean by training a faculty is

this: we mean the subjecting it to a course of discipline, so as to

strengthen and habituate it to perform certain operations with

ease and effect. Thus the muscles of the body may be enlarged

and strengthened by proper training; the hand may be trained

to peculiar performances; the eye to perceive the nicest

distinctions of art, and the ear, of various sounds. Indeed, there

is this wonderful peculiarity in our organization, which points

out to us our duty, in the proper use and exercise of

every part of the mind and body, that the vital current may flow in

that direction, not only to repair the waste consequent on that

exercise, but to enlarge and strengthen it to perform its operations

with greater ease; and the reverse of this is manifest when any part

of the body or mind is not exercised or disciplined, as it then

loses its energy and power of performance.

We have said that the mental powers have various and distinct

properties; and though it is not necessary to our object to go into

the particulars of these, nor the various metaphysical opinions

respecting them, it will greatly assist us in our explanations, to

describe them as intellectual and moral faculties;—all

of which faculties may be well or badly trained,

according to the knowledge and discipline bestowed; in other words,

as the individual may have been subjected to a PROPER

or IMPROPER COURSE OF EDUCATION.

A man's intellectual faculties may be highly cultivated, and

yet he may be a very worthless and immoral member of society, for

want of that moral education necessary to control his animal

feelings, and to direct his intellect to the performance of his

social and political duties.

Another man may have his moral faculties disciplined to

perform continuous acts of kindness and benevolence, and may possess

the strongest feelings of awe and veneration; and yet, for the want

of intellectual cultivation, may have his goodness of

disposition daily imposed upon by knaves and impostors, and his

credulity diverted to superstition and fanaticism.

The animal faculties being in common with the brute creation,

he who is without intellect to guide and morality to

direct them, will differ little from the brutes in the gratification

of them.

Examples of great intellectual attainments without

morality are to be found among all classes of society; from the

university-taught gentleman who uses his talent to gratify his

interest or ambition at the expense of justice, to the

experienced swindler or learned impostor, who lives by defrauding

and imposing on his fellow-men. And no men are fitter or more likely

to become the dupes of such persons than those whose moral

faculties are matured and intellectual ones neglected. Examples of strong animal propensities, without the reins of

intellect and morality to govern them, are seen in those mothers who

spoil their children by their ignorant indulgence of their

inclinations in those unions founded on mere animal love or

instinctive attachment, which occasion much social misery; in

gluttony, drunkenness, profligacy, debauchery, and extreme vice of

every description. Hence it will be seen that "EDUCATION,"

to be useful, such as will tend to make wise and worthy members of

the community, must comprise the judicious development and

training of ALL the human faculties,

and not, as is generally supposed, the mere teaching of "reading,

writing, and arithmetic," or even the superior attainments of

our colleges, Greek, Latin, and polite literature."

We have said that good education embraces the cultivation of all the

mental and bodily faculties; for be it remembered, that all

individuals (unless they are malformed or diseased) possess the

same kind of faculties, though they may materially differ in size

and power, just as men and women differ in size and strength from

each other. All men are not gifted with great strength of body or

powers of intellect, but all are so wisely and wonderfully endowed,

that all have capacities for becoming intelligent, moral, and happy

members of society; and if they are not, it is for want of their

capacities being so properly cultivated, as to cause them to

live in accordance with the physical laws of their nature, the

social institutions of man, and the moral laws of God. Education

will cause every latent seed of the mind to germinate and spring up

into useful life, which otherwise might have lain buried in

ignorance, and died in the corruptions of its own nature; thousands

of our countrymen, endowed with all the capabilities for becoming

the guides and lights of society, from want of this

glorious blessing, are doomed to grovel in vice and ignorance, to

pine in obscurity and want. Give to a man knowledge, and you give

him a light to perceive and enjoy beauty, variety, surpassing

ingenuity, and majestic grandeur which his mental darkness

previously concealed from him—enrich his mind and strengthen his

understanding, and you give him powers to render all art and nature

subservient to his purposes—call forth his moral excellence in union

with his intellect, and he will apply every power of thought and

force of action to enlighten ignorance, alleviate misfortune, remove

misery, and banish vice; and, as far as his abilities permit, to

prepare a highway to the world's happiness.

There is every reason, however, for supposing that many persons have

been led to doubt the great benefits of education, from what they

have witnessed of the dissipated and improper conduct of those who

have had great wealth expended on their education; and that others,

observing the jealousies, contentions, and ambition of men

professedly learned, have been led to inquire "whether

educated men are happier than those who are ignorant." But from want of moral training in unison with intellectual

acquirements, such characters cannot be said to be "educated," in

the proper sense of the term; they have knowledge without wisdom,

and power without the motive to goodness. But as regards "happiness,"

(which may be defined to mean the highest degree of pleasurable

sensations,) we think we may safely aver that the ignorant many

can never be truly happy. He cannot even enjoy the same animal

happiness in eating, drinking, and sleeping as the brute; for the

demands society requires from him in return for these enjoyments

give him anxieties, cares, and toil which the brute does not

experience. The instinct, too, which nature has bestowed on the

lower animals to guide their appetites, seems to give them superior

advantages over a man destitute of knowledge. For, ignorant of his

own nature, and needing the control of reason, he is continually

marring his own happiness by his follies or his vices. Wanting

moral perceptions, the temptations that surround him frequently

seduce him to evil, and the penalties society inflict on him

punish him without reclamation. Ignorant of the phenomena of

nature, he becomes credulous, superstitious, and bigoted—an easy

prey to the cunning and deceitful; and, bewildered by the phantoms

of his own ignorant imaginings, he is miserable while living, and

afraid of dying.

But, it may be asked, what proofs can be adduced to show that the

truly educated man is the happier for being so? We will

anticipate such a question, and endeavour to afford such proofs as,

to us, appear clear and conclusive. In the first place, nature has

given to most of her children a faculty for acquiring

knowledge, which, once quickened and directed by education,

is continually gratified with its acquisitions, and ever deriving

fresh pleasures in new pursuits and accumulation of knowledge. To

give the greatest delight to those who wisely exercise this faculty,

nature has provided a multitudinous variety to be investigated and

enjoyed; she has spread out her wonders around them,

and unfolded her beauties to their gaze. By giving them the power to

transmit their acquirements to posterity, she has opened to their

mental view the whole arcane of science and range of art, to afford

them unlimited sources of enjoyment.—In the next place, nature has

in her bounty conferred on them all the powers of moral

superiority and social gratification, which, if wisely cultivated,

afford them pleasures inexhaustible. Those noble attributes of man's

nature, ever stimulating him to great deeds and good actions, cast a

continual sunshine over the mind of him who obeys their dictates;

they render his life useful, and give him peace and hope in the hour

of death. Nor can any cultivated man for a moment doubt these

positions; he has the proof and evidence in his own feelings, and

his righteous actions will afford the best testimony to the rest of

mankind.

From what we have said on the nature and intention of

education, we think its importance must begin to be evident; for

what man is there who, in inquiring into the laws of his nature,

finds that his own individual happiness is a condition

dependent on the cultivation of his mental and moral powers, but

will readily admit the importance and necessity of proper

education?

But let us proceed from individual to social

considerations, (for individual happiness seems to be dependent on

social arrangements,) and inquire how far a man's happiness is

marred or retarded by the ignorance, and the consequent vices, that

prevail in society. If his acquirements enable him to perceive

the necessity for improving the social institutions of his country,

in order to advance the prosperity, knowledge, and happiness of his

neighbours, their prejudices, selfishness, and cupidity are

formidable obstacles to deter him from the attempt. If he be engaged

in any trade or profession, and desire to exercise his calling with

honesty and conscientiousness, he is exposed to the united rivalry

of all those who find their gains promoted, and rank upheld by

dishonesty and injustice, or the fraudulent system they have

established is such as speedily to drive him from his business or

consign him to poverty. If he be the father of a family, and

desirous of promoting the happiness of his children by rendering

them intelligent, moral, and useful, he cannot with all his anxiety

guard them from the contaminating effects of social vice. The ears

of his children are assailed by brutal and disgusting language in

the midst of his dwelling, their eyes meet with corruption and evil

in every street, and seductions and temptations await them in every

corner. Should their youthful years be happily preserved from those

influences, they are no sooner ushered into society, than

they are beset with all its selfish, lying, defrauding, and

mind-debasing vices; and they must be strong indeed in mind and

steadfast in morality, to Withstand these tests without

pollution;—and many a fond parent who has reared up his children

with tender solicitude, whose most cherished hopes have been centred

in their welfare, has seen them all gradually engulfed in the vices

and corruptions of social life. If a man be poor, he is subjected to

all the evils of social injustice; and if he be wealthy, his life

and possessions are continually jeopardised by the vicious and

criminal victims of ignorance: in fact, in no situation in society

can a man be so circumstanced, as to escape the evils inflicted or

occasioned by the ignorance of others.

Can any man of reflection fail in perceiving that most of these

social evils have their origin in ignorance? What but the want of

information to perceive their true interest, and the want of moral

motives to pursue it, can induce the wealthier classes of

society to perpetuate a system of oppression and injustice which in

its reaction fills our gaols with criminals, our land with paupers,

and our streets with prostitution and intemperance? What but the

want of intellectual and moral culture occasion our middle-class

population to spend their careworn lives in pursuing wealth

or rank through all the soul-debasing avenues of wrong;

and, after all their anxiety to secure the objects of their

ambition, find they have neglected the substantial realities of

happiness in the pursuit of its phantom? And what shall we say

of that large portion of our population who have been born in evil

and trained in vice?—nay, whose very organization, in many

instances, has been physically and mentally injured by the

criminality of their parents? [7] Their

perceptions continually directed to evil, their notions of right and

wrong perverted by pernicious example, and thereby taught that the

gratification of their animal appetites is the end and object of

their existence, can we wonder that they become the hardened pests

of society, or, rather, the victims of social and political

neglect—beings whom punishments fail to deter from evil, and for

whom prisons, penitentiaries, laws, precepts, and sermons are made

in vain? What man, then, perceiving these lamentable results of

ignorance, and possessing the least spark of benevolence, is not

prepared at once to admit the necessity for beginning our social

reformation at the root of the evil, by establishing a wise

and just system of education?

But if we want further proofs to convince us of its necessity, let

us turn from our social to our political arrangements. The fact of an insignificant portion of the people arrogating to

themselves the political rights and powers of the whole, and

persisting in making and enforcing such laws as are favourable to

their own "order," and inimical to the interests of the many, afford

a strong argument in proof of the ignorance of those who submit to

such injustice. And when we find that vast numbers of those who are

thus excluded readily consent to be drilled and disciplined, and

used as instruments to keep all the rest in subjection, the proofs

of their ignorance appear conclusive. And even those who

possess the franchise, (or nominal power of the state,) if we may

judge from their actions, are not more distinguished for their

wisdom than those mercenaries; for, after selecting their

representatives in the most whimsical manner—some for their titles

of nobility or honour; others for their lands, interest, or party;

and some for having bought them with money or promises—they

support them in every extravagance and folly, and submit to be

plundered and oppressed in a thousand forms, to uphold what they

pompously designate "the dignity of this great nation." And

surely the annual catalogue of crimes in this country of itself

affords lamentable proofs of the ignorance or wickedness of

public men, and their great neglect of their public duties. Those will stand in the records of the past as black memorials

against the boasted civilization and enlightened philanthropy of

England, whose legislators are famed for devising modes of

punishing, and in numerous instances for fostering crime,

exhibiting, year after year, presumptive proofs in their omission to

prevent it. It will be said of them, that they allowed the children

of misery to be instructed in vice, and for minor delinquencies

subjected them to severity of punishment which matured and hardened

them in crime; that, callous to consequences, they had gone through

all the gradations of wretchedness, from the common prison to the

murderer's cell, that their judges gravely doomed them to die, gave

them wholesome advice and the hopes of repentance; and, when the

fruits of their neglect and folly were exhibited on the gallows,

they gave the public an opportunity of feasting their brutal

appetites with the quivering pangs of maddened and injured humanity. Whether, then, we view man individually, socially, or

politically—whether as parent, husband, or brother, there is no

situation he can be placed in, in which his happiness will not be

marred by ignorance, and in which it would not be promoted by the

spread of knowledge and wisdom.

Convinced of the importance of an improved system of

education, we think there needs little to convince any one of the

necessity of its being made as general as possible; for, if

the effects of ignorance are so generally detrimental to happiness,

the remedy must be sought for in the general dissemination of

knowledge;—we see and feel enough of the effects of partial

knowledge, to warn us against the evil of instructing one portion of

society, and suffering the other to remain in ignorance. What, but

the superior cunning and ingenuity of the few, and the ignorance of

the many, have led to the establishment of our landed monopoly in

its present state—our trading and commercial monopolies—our

legislative and municipal monopolies—our church and college

monopolies—and, in short, all the extremes of wealth and

wretchedness which characterize our fraudulent system? In fact, the

cunning and trickery which uphold this system have become so

evident, that all those who seek to profit by it, are not so much

induced to send their children to schools and universities to

acquire knowledge for its own sake, or to make them better or

more useful members of society, as they are to qualify them

to rise in it; in other words, to enable them to live in

idleness and extravagance on the industry of other people. This

state-pauperizing disposition, this aristocratic contempt for all

useful labour, is to be traced to our defective education; and

knowledge will be found to be the only remedy for this, as well as

for the vices, follies, and extravagances of the few. If the

blessings of education were generally diffused—if honesty and

justice were daily inculcated among all classes of society, it

would, ere long, lead to a more just and general diffusion of the

blessings of industry. But as long as one part of the community feel

it to be their interest to cultivate mere

power-and-wealth-acquiring knowledge, and, as far as they can,

to prevent or retard the enlightenment of all but themselves, so

long will despotism, inequality, and injustice, flourish among the

few; and poverty, vice, and crime, be the lot of the many.

But, while we are anxious to see a general system of

education adopted, we have considerable doubts of the propriety of

yielding such an important duty as the education of our children to

any government, and the strongest abhorrence of giving any such

power to an irresponsible one. While we are desirous of

seeing a uniform and just system of education established,

we must guard against the influenced of irresponsible power and

public corruption; and, therefore, we are opposed to all

concentration of power beyond that which is absolutely necessary to

make and execute the laws; for, independent of its liability to

become corrupt, it destroys local energies, and prevents experiments

and improvements, which it is most desirable should be fostered, for

the advancement of knowledge, and prostrates the whole nation before

one uniform, and, it may be, despotic power. We perceive the results

of this concentration of irresponsible power and uniformity of

system lamentably exemplified in Prussia, and other parts of the

continent, where the lynx-eyed satellites of power carefully watch

over the first indications of intelligence, to turn it to their

advantage, and to crush in embryo the buddings of freedom; and,

judging from the disposition our own government evince to adopt the

liberty-crushing policy of their continental neighbours, we

have every reason to fear that, were they once entrusted with the

education of our children, they would pursue the same course to

mould them to their purpose. Those who seek to establish in England

the continental schemes of instruction, tell us of the intelligence,

the good behaviour, and politeness of their working-class population

but they forget to tell us that, to talk of right or justice, in

many of those countries—to read a liberal newspaper or book,

inculcating principles of liberty, is to incur the penalty of

banishment or the dungeon. They forget to tell us that, with all the

instruction of the people, they submit to the worst principles of

despotism; that life and property, as well as all the powers and

offices of the state, are mostly vested in one man or his minions,

and that the vilest system of espionage is everywhere established to

secure his domination. They omit to inform us, that parents are

compelled, under heavy penalties, to send their children to the

public schools, where the blessings of despotism, and reverence for

the reigning despot, are inculcated and enforced by all the arts and

ingenuity submissive teachers can invent and that all those who

brave the penalties, and teach their children themselves, are

subject to infamous surveillance, and their children declared

incapacitated to hold any office in the state. Bowed down and

oppressed as we already are, we manage to keep alive the principles

and spirit of liberty; but, if ever knavery and hypocrisy succeed in

establishing this centralizing, state-moulding, knowledge-forcing

scheme in England, so assuredly will the people degenerate into

passive submission to injustice, and their spirit sink into the

pestilential calm of despotism.

With every respectful feeling towards those philanthropists whose

eloquence first awakened us to the importance of education, and

whose zeal to advance it will ever live in our remembrance, we have

seen sufficient to convince us that many of those who stand in the

list of education-promoters, are but state-tricksters, seeking to

make it an instrument of party or faction. We perceive that one is

for moulding the infant mind upon the principles of church and

state, another is for basing its morals on their own sectarianism,

and another is for an harmonious amalgamation of both; in fact, the

great principles of human nature, social morality, and political

justice, are disregarded, in the desire of promoting their own

selfish views and party interests. From the experiments already

made, at home and abroad, they see sufficient to convince them of

the importance of early impressions; and hence their eager desire to

mould the plastic mind to their own notions of propriety. They also

see that the flood-gates of knowledge are opened, and that its

purifying stream is rolling onward with rapidity; and fearing their

own corrupt interests may be endangered, they seek to turn it from

its course by every means and stratagem their ingenuity can invent.

If our government were based upon Universal Suffrage

to-morrow, we should be equally opposed to the giving it any such

powers in education, as some persons propose to invest it; its power

should be of an assisting and not an enforcing

character. Public education ought to be a right—a right

derivable from society itself, as society implies a union for

mutual benefit, and, consequently, to provide publicly for

the security and proper training off all its members. The public

should also endeavour to instruct the country, through a

board of instructors, (popularly chosen,) on the best plans of

education or modes of training; and should induce, by prizes or

otherwise, men of genius and intelligence to aid them in devising

the best. After their plans have been matured, and the greatest

publicity given to them, the people should be called upon to choose

(by universal suffrage,) two members from each county, to form a

special body, to consider such plans, and to amend, adopt, or

reject them, as they may think proper; leaving those in the

minority to till adopt such plans as their constituents may

approve of, the merits of the plans selected by the majority became

obvious to all. Such a mode as this would be more in accordance with

liberty and justice than the legal enforcement of any particular

plans of education, as of all other subjects it involves greater

consequences of good or evil. Government, then, should provide the

means for erecting schools of every description, wherever they may

be deemed necessary; and empower the inhabitants of the respective

districts to elect their own superintendents and teachers, (if

qualified in normal schools,) and to raise a district rate

for the support of the school and remuneration of the teachers. If

we had a liberal government to do this for the education—if the

whole people were to be interested in the subject, through popular

election, instead of a select clique, we might safely trust to

the progress of knowledge and power of truth to render it popular,

as well as to cause the best plans, ere long, to be universally

adopted. But from our government no such liberality is to be

expected—we have every thing to fear from it, but nothing to hope

for; hence, we have addressed ourselves to you, working men of

Britain, and you of the middle classes who feel yourselves

identified with them, as you are the most interested in the

establishment of a wise and just system of education. And we think

we have said sufficient to convince you of the necessity of guarding

against those state and party schemes some persons are

intent on establishing, as well as to induce you to commence the

great work of education yourselves, on the most liberal and just

plan you can devise, and by every exertion to render it as

general as possible; hoping that the day is not distant when

your political franchise will give you the power to extend it with

rapidity throughout the whole empire.

Having briefly given our views of the nature, intention, and

importance of education, the next part of our subject necessarily

embraces the particular description of education to be pursued in

the different schools, and the best mode of imparting it.

The first difficulty we shall have to surmount in our progress will

be the teaching of the teachers; and the particular

instruction, or mode of training, which they will require,

necessarily appertain to the NORMAL OR TEACHERS'

SCHOOLS. The establishment of one (at least,) of those

schools should therefore be one of the first objects of the

association. Whatever may be its particular plan, we think it should

be so constructed as to contain an infant, preparatory, and high

school, into which children of all ages should be admitted, and in

which the persons learning to be teachers shall be taught a

practical knowledge of the system of education. It should also

contain a library, museum, laboratory, sitting-rooms, and

sleeping-rooms for the teachers and directors. There should be two

general teachers, or DIRECTORS, possessing an

intimate knowledge of the best plans and modes of education, and

well qualified in the art of imparting it with effect and kindness

of disposition. While every encouragement should be given for the

gratuitous instruction of all those desirous of being qualified as

teachers, great care and discrimination would be necessary in

guarding against the admission of persons who possess neither the

disposition, aptitude, nor capabilities for efficient teachers. The

educational students should commence with the infant school, and,

when proficient in that department, should proceed to the

preparatory school; and so on, till they become conversant with

every part of the system. [8] Their time

should be so divided, that it should be spent in the schools, and in

studying the best works on the subject; in attending to the lectures

or discourses of the directors, and in discussions and conversations

among themselves. The time necessary properly to qualify a

teacher

must (in our first arrangements,) be made to depend on the judgment

of the directors; but after our plans are matured, it may be found

necessary to fix the time each person shall study in a normal school

to qualify him or her for a teacher; and eventually no persons

should be employed in the schools of the association but those who

could produce a certificate, signed by the directors, testifying

their competency. But one important duty must not be neglected by

the people themselves— that of rewarding and honouring the teachers

of their children, as this will be the best means of perfecting the

science of education, by an accession of men of genius and

intelligence, who otherwise will seek rewards and honours in other

pursuits.

THE INFANT SCHOOL.

A school of this description might be conducted by a female teacher

and an assistant, if the teacher had received her instruction in a

normal school. The first requisite she should possess, is a

disposition to win the affectionate confidence of the little beings

committed to her care; to effect which, she must supply the place of

an attentive, kind, and intelligent parent. The first object to be

achieved, is to render the school-room a little world of love, of

lively and interesting enjoyments; and its attainment will mainly

depend upon the benevolent, cheerful, and instructive disposition of

the teacher.

Her acquirements should extend, in the first, to a general knowledge

of the human frame and constitution, and the best mode of preserving

the children in full health and vigour, embraced in the terms

PHYSICAL EDUCATION.

Second, she should have a clear idea of the human intellect, and

should possess a knowledge and aptitude for judiciously developing

its perceptive, comparative, and reflective powers, comprised in the

words INTELLECTUAL EDUCATION.

Third, she should fully comprehend the moral capabilities, and

the

laws which govern the feelings; and should understand the means by

which they may be so quickened, directed, and trained, that the

child shall aspire to greatness and goodness of character, and be

able to govern his passions by his reason;—the whole expressed by

the terms MORAL EDUCATION.

In addition to these essential requisites, she should possess a

knowledge of music, have a voice for singing, and be able to express

herself clearly and grammatically. She should also possess the love

of order, have a refined taste, should be courteous in her manners,

and prudent and respectful in her whole conduct. For as her

peculiarities will be readily imitated by the children, and her

example produce a lasting effect on them, she should be to them, as

far as possible, a standard of excellence worthy of imitation.

It has been found by experience that the best mode of establishing

an infant school is to begin with a few children; and, after they

have made some little progress, gradually to introduce others. By

this means, a system of order will be sooner established than if a

great number be brought together at once.

The school hours must necessarily vary in different districts,

according to the habits of the people; but whatever time is fixed on

for the opening of the school should be punctually observed. The

boys and girls should enter by their respective doorways, and each

one, being provided with a place in the cloak-room for his or her

hat or cloak, should be instructed to hang it under a particular

number; they should then proceed to their seats in the school-room,

which should have corresponding numbers. As a means of cleanliness

and health, door-mats should be placed at each entrance, and cleanly

habits in every particular must be scrupulously insisted upon. Some

little trouble will be necessary at first to enforce those two

essentials, cleanliness and punctuality of attendance; but by

judicious management, in a short time the public opinion of the

school will extend to the homes of the children, and serve to awaken

inattentive parents to their duties. At the ringing of a bell, the

school should be formally opened by the children singing some

appropriate piece, and no person should be admitted into the room

until its conclusion. They should then be engaged with their lessons

in the school-room, and amusement and exercise in the play-ground,

alternately, according to the state of the weather, and the

arrangements of the school but one great point to be attended to by

the teacher, is not to allow them to be over-exerted either with

their lessons or their play, though the air, exercise, and moral

training of the play-ground are of paramount importance.

The classification of both sexes, according to their ages, will be

found necessary, as there is reason to suppose that the older

children will be more advanced in knowledge than the younger, and

because they are too apt to tyrannize over them. They should

therefore be classed, six or eight in a class, as may be found most

convenient; and a class-teacher should be appointed weekly to each

class. This method of causing children to teach each other is so

much in accordance with their desires and feelings, begetting in one

an anxiety to qualify himself to teach, and calling forth the mental

and speaking faculties of the other, that this of itself is

sufficient to cause us to revere the name of Joseph Lancaster. The

class-teacher should see to the attendance, cleanliness, order, and

proficiency of his class; and should be carefully watched, to see

that he properly and courteously perform his duties. He should,

however, have no power in the play-ground;—when there, he should

have full and unconstrained liberty, as the other children, subject

only to the watchful eyes of the teacher and assistant.

Having slightly glanced at these preliminaries, we now come to the

mode of education; and here we would especially impress on you, that

no faculty of mind or body can be educated without it is properly

exercised.

In physical education, for instance, the mere teaching of a child

that pure air and exercise are necessary to preserve him in health

and strength, is of little use; he must not only be made to

perceive, by a judicious course of instruction, how and why they are

essential, but he must be made to feel their importance, by such

proper means of exercise as the play-ground should afford, till the

conviction and habit became blended, as it were, with his very

nature. He should be made to understand, by the most simple

explanations, why pure air is necessary to health, and how all kinds

of animals linger and perish if they are deprived of it. He should

have the different parts of the body familiarly explained to him,

and a general idea given of his animal functions; and why it is that

exercise is necessary to health and strength. There will be some

difficulty in conveying this knowledge to a child; but unless a

general idea of it be conveyed, the mere advice or precept to do or

avoid doing any particular act will be useless. He may be

constrained to perform any duty in obedience to the commands of his

parents or his teachers, just as a dog is taught to fetch or carry a

stick; but the importance of doing it will have no effect, till they

are fixed by conviction and rooted by habit. If, however, the

teacher fully understands these subjects herself, and has an

aptitude for conveying knowledge, she will, by a little additional

trouble, make them clear to her pupils; and in her subsequent

teaching she will find herself well rewarded for having laid a good

foundation. [9]

The best description of exercise is that which brings the greatest

number of muscles into proper exertion, and which, at the same time,

affords rational pleasure. Much, however, remains to be done in

devising proper exercises for children;—many of those in common

practice are found to produce physical injury to weak constitutions,

and others to produce irrational associations. The rotary swing,

which is used in many schools, is well adapted for strong children;

shuttle-cock, if played with both hands—dancing in the open

air—together with such evolutions as may describe the actions and

habits of different animals which children are fond of imitating,

will be sufficient exercise for the children in the play-ground. The

manual exercise, as it is called, descriptive of different notions

and actions, will be found highly beneficial for in-door exercise in

bad weather. But a skilful teacher will readily invent games and

amusements for the children, will join with them in their play, and,

when all their faculties are in full activity, will inculcate many

intellectual and moral lessons.

In intellectual education no real knowledge can be acquired but by

the exercise of the perceptive, comparative, and reflective powers. The child may be burthened with a multitude of words—mere barren

symbols of realities of which it has no cognizance, with imaginary

notions of every description—mere treasured phrases, imbibed from

every source, without inquiry or knowledge of the reality,—it may

be furnished with rules, figures, facts, and problems by rote

without examination, and consequently valueless for practical

purposes;—all these acquisitions failing to produce clear ideas, and

forming no real basis for reflection or judgment, cannot, therefore,

be properly designated real knowledge. Yet this word-teaching,

rote-learning, memory-loading system is still dignified with the

name of "education;" and those who are stored with the most lumber

are frequently esteemed the greatest "scholars." Seeing this, need

we wonder that many scholars have so little practical or useful

knowledge, are superficial in reasoning, defective in judgment, and wanting in their moral duties? or that the greatest blockheads at

school often make brighter men than those whose intellects have been

injured by much cramming?

Real knowledge must be conveyed by realities; the thing itself must

be made evident to one or more of the senses, to convey a knowledge

of its form, size, colour, weight, texture, or other qualities. Those perceptive powers, being continually

exercised by the

observation of various objects, become gradually strengthened and

matured, and the knowledge of their qualities rooted in the memory. It is the high cultivation of those faculties that gives the artist

and sculptor such nice perceptions of the tints, forms, and symmetry

of their productions. In order, therefore, to educate the

perceptive

powers of the child, he must be directed to observe things, their

qualities must be things, evident to his senses; he must be taught,

in the first place, to observe their most obvious properties and

characteristics, and as his mind expands he must be made acquainted

with all their other qualities.

After his perceptive powers have been awakened by observation, and

the qualities of things impressed upon his memory, the next object

is to stimulate and educate his comparative powers. To effect which,

his attention should be directed to the differences and similitudes

of objects in all their various qualities, to compare their relative

forms, position, distances, arrangement, number, &c.

Then his reflective powers should be directed to the why and

wherefore of all those forms, qualities, analogies, and differences

which have previously occupied his attention. This mode of

proceeding will gradually cultivate his discriminating and

reflective powers as regards realities, and will lay the foundation

of clear and consecutive reasoning.

But in conveying this knowledge of things to a child, the teacher

must be careful as regards over exerting its attention, and also

guard against confusing it, which she will be apt to do, if she

proceeds to describe or direct attention to one object after another

in rapid succession, and goes through all their various qualities,

uses, &c. She must proceed step by step, and be certain that her

little pupils have clear ideas on one point before she proceeds to

another; otherwise they will get confused, or imbibe her

explanations by rote, without understanding them. The teacher should

also see that, while the children's attention is directed to the

acquisition of the various kinds of knowledge referred to, they

should be taught the medium by which they acquire it; that is, they

should be familiarly and practically taught the uses of the senses.

But in teaching children a knowledge of things, a knowledge of

words

must not be neglected; and in the usual mode of teaching those two

essentials, there appears to us to be a deficiency for which we

presume to suggest a remedy. The deficiency seems to us to be in

this particular: the child's attention is first directed to things

and their qualities, and the words which express them are repeated

by the teacher; and according to the strength of the child's memory

they are retained there. His attention is next directed to a

reading

lesson, (probably with a picture at its head;) now, though he may

have previously heard the various words of this lesson, or may have

many of them treasured up, yet, when he sees them in print, they

appear to him as Greek or Hebrew characters appear to us, and he has

to undergo a second discipline, to enable him to connect the ideas

he has retained in his memory with those words; or, if he has not

retained the ideas previously taught him, he has to get the words by

rote. In short, there appears to be wanting in this mode of teaching

a closer connection of words and things. The following plan for

their more intimate connection will, in our opinion, effect this

object; and will also supply the best spelling and reading lessons

for the INFANT SCHOOL, and in the

PREPARATORY SCHOOL will be found highly useful

for teaching a knowledge of grammar and composition.

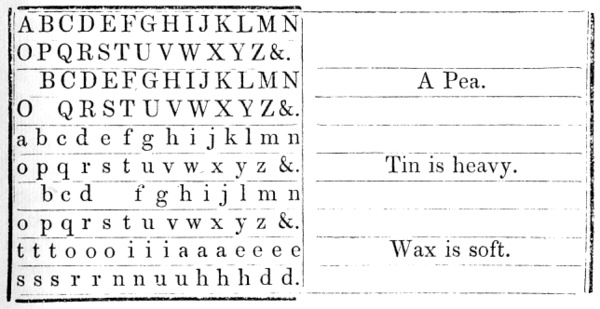

A Case of Moveable Types. [10.]

The above sketch represents a case, or shallow box, containing

moveable types or letters, constructed as follows: The types should

be made of beech, about a quarter of an inch in thickness, and

varying in size according to the size of the letters. The letters

should be printed in large, bold type, on tough paper, and should be

fixed on to the types, (or bits of wood,) with thin glue. Instead of

gluing them on singly, it will be better to glue them on a slip the

whole width of the case, and cut them off with a fine saw, and trim

them when the whole is dry. There should be two sets of Roman, and

two sets of small capitals, in each case, together with two or three

extra of those sorts of letters most used, such as e, t, o, i, a, n,

&c. The cases may vary in size as the lessons may require; those

twelve inches by ten will be a good size for the infant school. They

should be made of plane-tree, or of wood not liable to warp; the

sides to be half an inch thick and one inch deep, which should be

grooved in the inside for both top and bottom. They should be

mitred, keyed, and glued, and the bottom be put in at the same time

they are glued together; and slips glued on the bottom in the

inside, about a quarter of an inch wide, to separate each row of

letters. The types must be made to fit in the case, so that they may

easily be picked up; and if the slips between each row are made a

little thinner than the types, it will facilitate this. The top, or

lid, of the case should be made to slide easily towards the right

hand. A number of slips must also be glued upon the lid of the case,

(as seen in the sketch,) in which the words are to be composed.

We will now endeavour to describe the mode of using those types in

the infant school. Instead of "lesson posts," usually adopted in

those schools, we would suggest that stands (something like a

reading-stand) be substituted in different parts of the room, for

holding the letter cases; and if they were made with a drawer in

each, for containing the case and objects when not in

use, it would save the teacher much trouble. When the time for their

object-lesson has arrived, the class-teacher marches his

little class up to the stand, and arranges them in a half circle;

and having properly placed his case, and got ready his

objects, he takes up his position on the right of the stand

within the circle, mounted on a little stool, and provided with a

short pointing-stick. He then takes an object from his collection,

(or shows them the card or picture, as it may be,) and passes it

round for the inspection of his class, and then asks them its name. Some one of the children will most probably inform him; but if they

are all unacquainted with it, it becomes the duty of the

class-teacher to instruct them. Supposing one of them says, "It is a

pea," the class-teacher then requests one of them to compose

"A Pea;" he accordingly picks up the letters from the case, and

arranges them (as is seen in the sketch) on its lid. After it is

thus composed, he requests another child to spell and read

what is composed; and so he proceeds, giving them different objects,

asking them their names, then to compose those names, and then to

spell and read them. By permitting those that can to name the

object, will quicken the faculties of all; and by calling upon them

alternately, one to compose, and another to spell, it will

arrest the attention of the whole; when, if they were asked in

rotation, those who had had their turn would be inattentive. In

giving this example, however, it is assumed that the children have

been previously instructed in a knowledge of the letter case, and

also to distinguish the capitals from the smaller letters, and their

use. For the first class of children it will be necessary to select

those objects that are easily spelled, as pea, tin, nut, wax, lead,

iron, &c.; and, if they are pictures of animals, such as cat, dog,

ass, goat, sheep, horse, &c.

After they have thus learned to understand the words

conveying the names of those objects which are easily spelt,

their attention should be directed to their most obvious

qualities, as "Tin is heavy," "Wax is soft," &c., which

sentences they should be taught to compose and spell as before. By

thus presenting familiar objects to their senses, then teaching them

their names, then the letters that compose them, and then their

sounds, we give them a clear conception of words: and by

their handling the objects and letters, we interest them in every

step of their progress. By this simple contrivance the children can

spell be taught to spell without the use of books, and

without the mischievous system usually pursued of tasking and

over-burthening the memory with words, which, when acquired,

are useless till the objects or qualities they represent are made

evident to the senses of the child. Reading can also be

taught with facility by this method; and being always in connection

with things and their properties, the knowledge thus conveyed

is more likely to be comprehended and impressed on the memory, than

if the child had to spell and stumble his way through a long

paragraph, the sense of which he would in all probability lose, from

the difficulties he would meet with, and the want of clear and

definite associations. The arrangement of the words by the

method suggested would also enable the teacher to convey

incidentally the grammatical meaning of several of them; but

this would be of little importance in the infant school. If figures

be substituted for letters on the types, the children may be taught

the use and value of figures, though the properties and

elements of numbers should always be taught by real objects;

therefore, it would be well to use Mr. Wilderspin's arithmeticon in

connection with the types. [11] In fact,

the letter-case, in the hands of a skilful teacher, will, as

we conceive, be found a pleasing instrument for conveying a vast

fund of information to the mind of a child.

During the time the children are thus occupied with their lessons

under their respective class-teachers, the teacher and assistant

should be engaged in superintending and instructing them; and a

variety of questions may be put and information given at those

times, which may have a very beneficial tendency.

In order to impress particular objects on the memory, as well as to

cultivate their tastes and perceptions of beauty, the room should be

ornamented with well-executed, coloured prints, or drawings, in

natural history, zoology, astronomy, and machinery, together with

neat models, and a few specimens of minerals and fossils; and at

different times their attention should be directed to them, and

their use and characteristics explained. The teacher should also

give them an idea of angles, squares, circles, &c., from objects, or

from various instruments and models, which can be cheaply obtained

for that purpose. For instructing them in a knowledge of weights and

measures, it would be well if some of the smaller ones were

introduced into a corner of the play-ground, as well as some clean

sand for the children to weigh and measure, and let them prove by

experiment that so many ounces make a pound, or pints a gallon;

they should, however, be provided with a scoop, to prevent them from

soiling their hands. The most advanced class should be provided with

small slates, on which they should be taught to form the outlines of

squares, angles, circles, and eventually of letters, by copying from

diagram-boards placed slantingly before them on the floor. Nor

should their tuneful powers be neglected, as the exercise of

them would be both healthful and instructive; but care should be

taken against practising them in any nursery nonsense, or in

compositions they cannot understand. Pieces inculcating their social

and moral duties, or descriptive of beauty and perfection in nature

or art, will be found the most useful. The children should also be

taught the elements of dancing, both for exercise of body and

cheerfulness of mind. While, however, much intellectual

knowledge may be conveyed in a pleasing manner to little children,

care must be taken to convey it clearly, however slowly the

progress may be, and also that the child is not forced beyond its

natural powers.

Having given our opinion regarding the means of exercising and

educating the physical and intellectual powers of the child, it is

now necessary to advert to the most important feature in infant

training, that of moral education. And here we would again

premise that the moral faculties must be positively exercised,

the same as the intellectual or bodily faculties, in order to train

or educate them; that is, each faculty must be separately appealed

to by some exciting cause, and by constant exercise and

discipline directed to such course and conduct as shall best

promote the happiness of the individual, and of the society of which

he is a member.

We have already said that every individual possesses, in common

with other animals, a great variety of animal inclinations;

these are more active in some than in others, but they are more

active in all than the nobler faculties, designated moral

faculties. Those animal propensities confer a great

amount of happiness on the individual when they are governed by

morality and directed by intellect; but otherwise, they dispose

him to gratify his inclinations selfishly, cruelly, unjustly, and

intemperately. On the contrary, it is the nature of the moral

faculties to predispose him to a love of justice, truth,

benevolence, firmness, and respect for whatever is great and good;—but

they need cultivation; and, unfortunately for mankind, the

circumstances calculated for their development and cultivation are

not placed so easily within the reach of individuals as are those

circumstances which develop and bring the animal propensities

into activity. Perceiving this, the question for inquiry is, what

are the means to be adopted for educating those nobler faculties of

our nature, so that in conjunction with knowledge they may be made

to direct wisely and temperately govern the selfish and sensual

desires? But will mere advice or precept be

sufficient for this purpose? will these be sufficient to educate the

moral any more than the intellectual powers of the

mind? And what course do we adopt to cultivate the intellectual

faculties of our children? Are we content with merely advising

them to read, write, and cypher? with lauding the great

advantages of mensuration? or with promising to reward them,

if they will but excel in a knowledge of geometry? Certainly not;

for what possible good would such conduct effect? what conceptions

can they form of those various kinds of knowledge, till they are

made evident to their senses, and till their understandings are

gradually trained to perceive and appreciate their importance?—then,

indeed, will our precepts be responded to by their

convictions, but till then will be of little use. Should not this

common sense mode of educating one set of faculties be our guide for

another? nay, does not experience prove that, if we would succeed in

cultivating the moral faculties, we must proceed in precisely the

same manner as we do with the intellectual? For instance, if we

would cultivate the love of justice in a child, we must first

make the idea of justice evident to his sense, by pointing

out to him such instances of injustice and impropriety as may occur

in his own conduct or in that of others, and give him the reasons

how and why be should have acted the reverse. The love

of truth should be cultivated in the same manner, though it

forms an almost inherent principle in children, till they are taught

falsehood by the example of their parents or others; but when so

corrupted, they can only be cured by the same intellectual and moral

discipline. Benevolence, kindness, and humanity must

be equally rendered obvious to the understanding; unhappily,

examples of misery, unkindness, and cruelty are everywhere too

prevalent. Not that children should be taken out of their own sphere

to witness them, but in their own little circle every opportunity

should be embraced of directing their attention to any object,

incident, act, or anecdote, calculated to give them correct ideas

of the moral qualities sought to be conveyed, and then to

quicken and discipline their moral faculties. [12] As one means of calling forth and educating some of the higher

faculties, we would suggest the establishment of a sick fund

in every school. By instructing them to make their own rules and

conduct their own business, they will be readily brought to

understand principles of law and justice, and rules of duty and

obligation as members and officers; and by their visiting of their

sick members (unless in infectious cases), they may be practically

disciplined in kindness and humanity. It would be also advisable to

instruct them to make or amend such rules or regulation as may be

necessary for the government of their play-ground, which should be

hung up and appealed to when any one offended against them. [13]

All this may appear to some of trifling importance; but by such

trifles a skilful teacher would convey more practical lessons of

rights and duties than could be effected by volumes of

theoretical learning. The right of property is another

important lesson which, if made evident to the intellect, will, in

connection with their love of justice, be found the best security

against all kinds of pilfering and dishonesty. To call forth their

respect and admiration for all that is truly great and good,

the teacher should be assiduous in directing their attention to any

such acts whenever they occur, and she should occasionally read and

explain to them anecdotes of great deeds and good actions; not of

heroes and conquerors, the pests of our race, but of those whose

acts and deeds have augmented the amount of human happiness. They

should also be taught the importance of useful labour and the

value of industry, by showing them how labour is required for

the cultivation of the earth, in order to provide us with food,

raiment, and habitation, as well as to convert its productions into

articles for our necessity and comfort; and also that our bodies are

so organized that the exercise of moderate labour improves our

health;—and, therefore, seeing that labour is necessary, and that

all are benefitted by it, seeing all ought to labour and be

industrious, according to their abilities; and that all those

who, under any pretence, evade their fair share, act unjustly and

dishonestly towards their brethren, by imposing on them such

additional burthens of labour as to injure their health and diminish

their happiness. While they should be taught to value and respect

the acquisitions of honest industry, they should be made to

perceive the injustice of ill-acquired possessions, and to despise

every description of luxury, extravagance, and dissipation which

corrupts society, and diminishes the general amount of human

enjoyment.

Nor must their imaginative powers be neglected; to develop

which, their attention should be directed to the various points of

beauty, grandeur, and sublimity which are seen in the glowing

landscape, the flowing stream, the storm, the sunshine, and the

fragile flower; and, above all, the radiant glory of a star-light

night. Such lessons will teach them to soar beyond the grovelling

pursuits of vice and sordid meanness.

As affording the best means of regulating their appetites and

desires, they should be familiarly instructed in their uses and

functions, and shown how undue gratification proves injurious to

health and morals;—how all their faculties of mind and body are

governed by peculiar laws, which laws must be obeyed, to

insure health and happiness; and that, whenever they are disobeyed,

sickness of body, pain of mind, or injury to their neighbours, are

certain to be the inevitable result.

While much moral instruction may be conveyed in the school-room, the

play-ground will be found the best place for moral training;

where all their faculties will be active, and when their

dispositions and feelings will be displayed in a different manner

than when they are in the schoolroom, where silence, order, and

discipline should prevail. But when in the play-ground, the teacher

should incite them to amusement and activity, in order to develop

their characters; and whenever any irregularity of conduct

transpires, she should put forth her reasons rather than her

authority;—her object should be to convince, rather than to

chide them. For if she attempts to restrain the passions or govern

the moral feelings by a system of coercion, she will as

surely fail in her object as most of chose who have gone before her. Another mental faculty which requires great care and attention is

the love of approbation;—this, when properly disciplined, is

an essential requisite to greatness of character; but, when

otherwise, it degenerates into low and selfish ambition. The teacher

would therefore do well to avoid all kinds of rewards and

distinctions, so as to prevent all kinds of mental rivalry among

her pupils; and she should also be careful in her praises and

scrupulous in her censures. For though such stimulants may call

forth some of their intellectual powers, it will be in most cases at

the expense of morality; for while those possessed of strong

distinctive feelings will strive to excel and rival their fellows,

their triumphs will call forth the envy, hatred, and hypocrisy of

all those who, are outrivalled. They should all be impressed with

a high, sense of duty, each to perform and excel according to

his abilities; and taught that nature having given them all

different powers of mind and body, he who cultivates his powers and

employs them to promote the happiness of society is sure to

meet with the approval of all good men, independently of his own

conscientious satisfaction. In short, the teacher must make it an

especial part of her duty to cultivate all the moral faculties,

as they are of paramount importance; at least, she must lay a sound

foundation. She must remember that each faculty has particular

functions to perform, and must be trained according to its

peculiarities—that, necessary to all moral instruction, the

intellect must be made to fully understand moral qualities, by

rendering them obvious to the senses—and that each faculty must

be awakened and disciplined by constantly exercising it, according

to its nature, and under the guide of the intellect.

In concluding these general observations on infant training, we have

thought it unnecessary to refer to many points of management—to the

heating and ventilating of the school, the particulars of the

play-ground, or the different kinds of apparatus required for

teaching. There is one point, however, necessary to mention, as it

involves a proposed alteration—it is this: in most infant schools,

they have a gallery in one end of the room, for the

simultaneous teaching of the children, an arrangement which, we

think, might be dispensed with, seeing that the room would be wanted

for other purposes of an evening. We would therefore suggest that

the side seats (constructed, like steps, one above another, like

those generally used in infant schools) be made moveable, and

in short lengths, so that they may be removed of an evening,

if necessary; and also, when any simultaneous teaching is required,

those at the furthest end of the room may be readily brought up, and

extended across wherever they may be needed, so that, when the

teacher is mounted on the rostrum, the children would both

hear and see as well as in a gallery.

THE PREPARATORY SCHOOL.

As will be seen by the plan of the district halls, we propose that

the upper room of each be fitted up for the purposes of a

PREPARATORY and HIGH SCHOOL,

for both males and females, until more extensive arrangements can be

made for building a greater number of schools in each district; but

in order to preserve the separation of the two schools, as well as

that of the two sexes, we recommend the arrangements as seen at

page 42, by which it is

proposed that the PREPARATORY SCHOOL be

situated in the body of the room—the boys on the right hand, and the

girls on the left, with a passage between them divided by a moveable

hand-rail, or by any other means. And as, in all probability,

comparatively fewer children will attend the HIGH

SCHOOL, we propose that a division be made in the upper end

of the room (as seen in the plate) on each side of the rostrum—the

boys on one side, and girls on the other. If, however, the numbers

in the respective schools vary considerably, other arrangements can

easily be made to accommodate them.

Instead of the usual writing-desks, which cramp the arms and distort

the bodies of children, we propose that tables be instituted

of the height required, made with drawers for holding their slates,

books, and school apparatus: and that the forms be made with

framed backs, as the spine is often injured from long sitting

without such support; and if they are made of the height necessary

for adults, by the placing of a foot-rail in front of the

table, they will be equally convenient for the children to sit upon. The rostrum, or platform for the teacher, should be made with

steps in front, and of a size sufficient for the assistant to sit

on; for the lecturers, &c., of an evening. On each side of the room,

in the piers between the windows, stands for the letter cases

should be fixed, and so made, that they may let down close to the

wall when not in use.

The school room should be handsomely fitted up and decorated with

maps, drawings, diagrams, and models, illustrative of the various

branches of knowledge. There should be a good coloured map of the

world, another of Europe, one of the United Kingdom, and, if

possible, a relief map of the county in which the school is

situated. There should also be large prints or drawings of the human

skeleton, of the muscular system, and of the interior of the human

body; also geological and mineralogical maps of the earth's strata;

prints, or drawings of the solar system; of the mechanical powers;

of perspective illustration; together with others of a like

instructive tendency. It should also be furnished with a pair of

globes, with Hadley's quadrant, Fahrenheit's thermometer, the

mariners' compass, geometrical models, models for drawing from, a

cast or model of the human brain, as well as any curious specimen in

nature or art of a useful and ornamental description. The

play-ground should also be provided with such useful gymnastic

arrangements as may be necessary for the exercise of the children,

as well as with any means or contrivance the teacher may think

necessary for their instruction. And it would be highly desirable if

every such school had a piece of garden attached, by which the

children may be taught some practical knowledge of horticulture and

botany. They should be allowed at least half an hour in the

middle of the forenoon and afternoon of each day, as well as their

dinner hour, for recreation and amusement in the play-ground, so

that their health may be preserved by proper air and exercise, and

their youthful spirits kept up in all their buoyancy, which the

present system of confinement, tasking, and drilling materially

tends to destroy. Any objections that may exist against the

association of boys and girls in the same play ground, may easily be

obviated by the girls being allowed to play in the ground of the

infant school, the time for the infants being there regulated

accordingly.

It would be advisable to have no schooling on the afternoons of

Wednesday and Saturday, in order that the teacher and assistant

might on those times take out the different classes in rotation, to

teach them a knowledge of those objects which cannot be properly

taught in the school room.

The same order should also be observed in these schools respecting

the children's hats, cloaks, and bonnets as in the lower school; a

similar system of classification should be continued, and the

same enforcement of cleanliness and regularity of

attendance.

The schools should be opened of a morning and closed of an evening

with vocal music, the principles of which should form a part

of the children's education; and the teacher should see that they

retired to their respective homes with more order and regularity

then are generally observed after school hours.

In addition to the qualifications enumerated as essential for the

teacher of the INFANT SCHOOL, the teacher in

the PREPARATORY and HIGH

SCHOOLS should possess the following requisites: he should

write a fair hand, be a good arithmetician, have a

general knowledge of mathematics and their practical

application to the arts of life. He should understand geography,

so as to explain the position, resources, habits, and pursuits of

different nations, and of his own country in particular; he should

know so much of astronomy as to be able to explain the

phenomena of the heavens, and of geology and mineralogy,

as to impart a knowledge of the structure and wonders of the earth;

he should possess some knowledge in natural history, so as to

give an account of the animals on the earth's surface, and

especially of his own species; he should have some knowledge of

chemistry and skill in experiments, and should know so much of

natural philosophy as to be able to explain the general

causes and effects in nature; of political knowledge he

should understand the basis of rights and duties, the principles and

theory of government, the foundation of law and justice, and

especially the political system adopted in his own country; he

should understand the principles of political, or national,

economy, comprising a knowledge of the production and

distribution of wealth; he should know something of the

philosophy of history, chronologically and biographically, so as

to direct the children to distinguish truth from fable and

falsehood, to detect deeds of shame and injustice beneath false

coverings of glory and honour, to strip sophistry of its

speciousness, interest of its panegyric, and heroes of their hollow

fame; and, as far as possible, to extract wisdom from the black

record of our species in their advance from barbarism towards

civilization. He should know something of botany, should have

a taste for gardening, and be acquainted with agricultural

pursuits; he should possess a knowledge of perspective,

and have a taste for design, so as to be able to sketch

correctly any object of art or nature: in addition to which, it

would be well if he understood the first principles of the most

useful trades.—Many persons may conceive that great difficulties