|

[Previous

page]

CHAPTER C.

THE ORATORS OF THE ANTI-CORN-LAW LEAGUE.

(1839-1874.)

THE Anti-Corn-Law League instructed the people, its

organisation enabled the people to express their opinion, but it was the

platform orators who inspired the opinion. The struggle of the

League lasted seven years, and cost half a million of money. In the

fourth year of its activity, Mr. Paulton stated that the League employed

upward of 300 persons in making up electoral packets of tracts, and 500

other persons in distributing them among the constituencies. In

England and Scotland alone they distributed to electors 5,000,000 tracts

and stamped publications, while to non-electors of the working class they

distributed 3,600,000 publications. In addition, the League had

stitched up in monthly magazines and other periodicals 426,000 tracts.

The entire number of tracts and stamped publications issued by the League

in the single year 1843, was 9,026,000, weighing upwards of 100 tons.

|

|

|

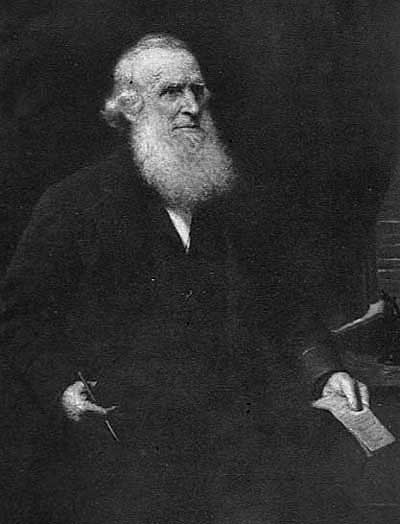

John Bright, M.P.

(1811-89) |

Such were the business features of this famous association. But its

success came from its inspiration, and its inspiration, as I have said,

came from its remarkable leaders.

Ebenezer Elliott wrote fiery rhymes for it; Gen. Thompson wrote its

Catechism; George Wilson, the chairman of the League, admittedly the most

efficient chairman in England during his day [organised its popular

action]; James Acland, a vigorous speaker, acquainted with the people, was

a sort of outrider to the League, going into market towns on market days

on a white horse, perhaps as a pacific emblem, but partly as a means of

drawing attention. He took the fighting among the belligerent

farmers, so that when Bright and Cobden came [here Mr. Bright changed the

order of names and put Cobden first] the strength of the enemy was known,

and the local stock of turbulence being expended, the peripatetic orators

obtained a hearing. Cobden mainly addressed himself to the

villagers. He foresaw the great jam industry, and predicted to

mothers cheap sugar and abundant fruit preserves. Oxfordshire

cottagers tell to this day of the happy tidings their mothers brought home

after listening to the League orators in the Market Place. Bright

dealt more with the landlords and farmers, into whose cold understanding

he poured the hot shot of League logic.

The League was the first body of agitators who introduced

method into public meetings. In the hour of argument in the Covent

Garden Theatre, Mr. Villiers' mastery of the question was heard, his high

character lending influence to the cause. Mr. Milner Gibson, another

Parliamentary voice, had a graceful and cogent eloquence which always

commanded attention. Mr. W. J. Fox, a Unitarian minister, and

subsequently M.P. for Oldham, surpassed all the orators of the

League of that day in brilliance of speech. Shorter and more rotund

than Charles James Fox, he, notwithstanding, produced effects of rhetoric

transcending those of his great namesake. The term "brilliant" does

not entirely describe them. You no more thought of his appearance

while he was speaking than you did of Thiers's insignificant stature.

His low, clear, lute-like voice penetrated over the pit and gallery of

Covent Garden Theatre. "You saw in the papers yesterday," he would

begin, "the case of a poacher who was seized, indignantly treated,

summarily tried, and sentenced to a serious term of degrading

imprisonment. If this," he exclaimed, "be the rightful treatment of

the poor man who steals the rich man's bird, what ought to be done to the

rich man who steals the poor man's bread?" In words to this effect

he spoke. Men remember that argument to this day. It

constituted the first words of his speech. He began with it.

No first words of any speech in my time ever produced the same effect upon

an audience.

|

|

|

Richard Cobden, M.P.

(1804-65) |

The public and the press were allured by the great names of Cobden and

Bright. Mr. Cobden, "the palefaced manufacturer," whom the

landowners believed, and the farmers were persuaded to believe, was a

Manchester enemy of agriculture, and a paid emissary of the Socialist

insurgents of the Continent, was himself the son of a Sussex farmer, whose

ambition was to die one of that class, and did so die, seeking and

accepting no other distinction than that which his genius cast around his

name. He was the logician of the League. As a master of lucid

statement on the platform or in Parliament, he left no equal at his death.

When he had made a statement, he looked at it and around it, as though he

saw it in the air before him. What was deficient he supplied, what

was redundant he withdrew, by putting the question in another way, in

which he omitted any mischievous word, or qualified any phrase he had used

which might mislead, so that he could not be misunderstood by accident,

nor his meaning perverted by design. This contributed to give the

League great ascendancy, since all its adherents could quote without fear

of contradiction what he said, and his speeches of one day became the

authority of the next.

Mr. Bright's was a grander, more imposing and impassioned

order of eloquence. Cobden presented the facts. Bright put

fire into them. With the finest voice of any European orator, he

displayed a measured vehemence on the platform which gave the impression

of unknown power. He was the Vulcan of the movement; he forged at

red heat, and hurled the burning bolts which finally set Protection on

fire.

Finally there came the collection maker of the League, R. R.

R. Moore, with a voice that fell on a meeting like the bursting of a

reservoir. It was not what he said, so much as the sound he made,

that produced the effect. The maddest clamour was not hushed—it was

overwhelmed by the new roar, which was always reserved to the end of the

meeting. His function was to appeal for subscriptions, and he

exactly answered that end, for when his astounding voice fell upon the

meeting no one seemed to have the power of going away. I do but

describe my impressions; but here Mr. Bright remarks: ["His speeches were

often logical and very good. The description of his voice is greatly

exaggerated. He worked hard and was of great service to the

League.—J. B."]

These were the great propagandists of Free Trade Economy, who

made conquest of the Premier, Sir Robert Peel, who won for himself an

imperishable name, by repealing in 1846 the Corn Laws; thus "giving the

people bread no longer leavened," as he proudly said, "by a sense of

injustice." Never was there such a wreck of political reputations as

took place within a few years of the abolition of Protection in Corn.

Nothing happened which had been predicted by the prognosticators of

disaster. Poor lands were more cultivated than before; no stoppage

of imports by war occurred; manufacturers and shopkeepers throve beyond

their forefathers' dreams of prosperity; instead of rents of land falling,

the aristocracy, the chief owners of it, grew rich while they slept—as

they do still; and farmers found "ruin" a very pleasant thing to them.

The working classes became better instead of worse employed, and their

wages in some places excite the jealousy of curates, while the

agricultural labourers are at last able to insist upon improved provision

for themselves. A stimulus, inconceivable before, was given to

trade; fluctuations in the price of corn decreased; apprehensions of

insufficient harvests no longer excited dread, and the British race became

physically one-half larger in bulk and one half heavier in weight than in

the days before Cobden and Bright arose. The victory of the

Anti-Corn-Law League was the greatest ever won by reason in the history of

human agitations. Neither in piety, nor morals, nor trade are men

for trusting one another. Everybody is for protecting his neighbour

from benefiting himself. Nobody is for leaving freedom free.

The principle of progress in commerce and social life is not to limit

liberty, but to limit injury. It was the establishment of this

principle in trade that caused this League to be regarded as one of the

historic forces of British civilisation.

Mr. Cobden told me one night at the House of Commons that,

despite all the expenditure in public instruction, "the League would not

have carried the repeal of the Corn Laws when they did, had it not been

for the Irish famine and the circumstance that we had a Minister who

thought more of the lives of the people than his own continuance in

power."

George Wilson was a great chairman. In a short, strong

speech he explained the position of the question (to be considered) out of

doors, and the case to be submitted to the meeting. But in

conducting the meetings he was despotic. There was no code for their

regulation then in England nor now, and despotism alone brought them to an

end.

During a thousand years the theory of public meetings in

England has not been revised. In Saxon times, we are told, the wise

men of the commune assembled under a tree and took counsel together.

If public meetings were limited to "wise men" in these days they would

seldom be crowded. Saxon public meetings were not so numerous but

that every one could give his opinion who had an opinion to give, and the

theory of the Saxon public meeting was that every one present had a right

to be heard. Upon this theory meetings to-day are held when they

amount to ten thousand persons, or, as at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, when

Mr. Gladstone was there, to thirty thousand. In the days of Thomas

Attwood a Newhall Hill meeting in Birmingham was held, when Daniel

O'Connell spoke, at which two hundred thousand persons were present.

Had each person "stood upon his right to be heard," the meeting would have

lasted a year. Whenever disorder is intended, persons are put

forward to "demand" a hearing. The friends of the impossible "right"

yell for it, and the friends of order yell against it. The chairman

all the while is as helpless as a windmill. When Mr. Jesse Collings, M.P., was Mayor of Birmingham, he was insulted by Tories for two

hours. They stopped the meeting over which he presided. They

had made a large drawing of the head of an ass, and suspended it from the

gallery in front of Mr. Collings, loudly calling his attention to it.

At last he ordered the police to remove the asinine rioters, who indicted

him for assault, which a Tory magistrate (Mr. Kynersley) sustained.

At Brighton, during the Tory Government of Mr. Disraeli, no Liberal

meeting could be held for five years, because the Liberals were unwilling

to physically fight the Tories who were ready with a contingent of

ruffians for that kind of disturbance. In Rochdale, when Mr. T. B.

Potter was first elected, men were sent into the town, armed with sticks,

to break up the meeting. I therefore advised that thick-headed

Liberals should be put in the front, and they proved to be the most

valuable members of the party of order, since they could best resist the

arguments of insurgent sticks. Patriots of cranial tenuity were of

no use.

It is singular and absurd that the right of public meeting

should be a boasted English institution, at which no chairman can lawfully

preserve order, and the proceedings can only be regulated by riot, or by

the cloture of clamour, as in the House of Commons. The organisation

of democracy is a long way off, and Liberalism is deliberate enough to

reassure the most alarmed and apprehensive Toryism in the kingdom not to

have established, one hundred years ago, the right of order at public

meetings, and promulgated a code of procedure suitable to the conditions

of modern days. The resolutions to be proposed should be described

by the Chair. They should be few, the speakers few, and the time of

each allotted and time for amendments provided and limited, and the

authority of the Chair as to order should be made legal. [27]

CHAPTER CI.

CAREER OF A BOHEMIAN ARTIST.

(1847-1877.)

ABOUT 1847, two young men came to London from

Oxford, not so much to seek their fortunes as to find occupation more

genial than that they followed. Still they both had the instinct of

distinction in them. One was George Hooper, who afterwards wrote, in

the Reasoner, some articles under the signature of "Eugene." He

brought some knowledge of Latin to town, and continued to read the

classics in his leisure, which was much to his credit. I spoke of

him to Mr. Thornton Hunt, and when the Leader was started he was

assigned a place upon it. He pursued journalism and authorship, and

made himself a name in military literature. His companion, Henry

Merritt, came to reside in my house, where he continued nearly eighteen

years, employing himself in picture restoration, in which he ultimately

acquired skill and repute.

His life had been one of vicissitude. His social

condition as a youth in Oxford was below hope, save by self-help. He

had been in a charity school, an errand boy about the colleges, had filled

various humble and precarious situations. In London he had been a

Bohemian with art-love in his mind, honesty in his heart, and nothing in

his pocket; with no patrons save a watchmaker in a passage off Drury Lane

and a Jew coffeehouse keeper in the Strand, both "good fellows" in their

way.

When about Graves's shop (the printseller's) in Oxford, he

had become acquainted with Mr. Delamotte, who, seeing the youth's taste,

kindly gave him encouragement; and what was more valuable, he gave him

instruction in art, for which Merritt was grateful all his days. He

dedicated his first book, "Dirt and Pictures Separated," thus:—

|

To

WILLIAM ALFRED

DELAMOTTE, ESQ.,

Who, when I was a boy—a stranger,

Unknown to him even by name,

Carefully and gratuitously instructed me

In the rudiments of art,

I inscribe this little Volume

With long-cherished feelings of respect. [28] |

As he resided with me, I had opportunities of introducing him to my

friends, and at times he shared invitations with me. He occupied two

rooms in my house (one being his studio), and had the use of the

dining-room. He paid seven or eight shillings then. Sometimes

he was in arrears several pounds, as I see from his account-book of that

time. When money came to hand he paid up arrears, for he was as

honest in his dealings as in his work.

When I removed to a lodge near Regent's Park, Merritt went

with me by his own desire. There he worked for two years upon the

oldest picture in England, Richard II, brought there from the Chapter

House of Westminster Abbey, and entrusted to him by Dean Stanley, Mr.

Richmond the elder superintending its restoration. Mr. Dennison, the

Speaker of the House of Commons, and other eminent persons, oft came to

witness the progress of the work. It was a delight to me to see this

picture day by day, and see the king revealed whose face no eye had seen

for 150 years. In the last century the House of Commons appointed

one Captain Broome to brighten up the portrait, who knew no more of

restoration than a house painter. He put upon the panel a new

portrait in which the king was lost, and a staring, treacle-faced young

man appeared in his place, with a sceptre as short and stumpy as a

policeman's staff. Underneath Broome's paint was found the true

presentment of the pensive, timorous king whom Shakespeare drew, holding a

graceful sceptre in his hand. Broome had forgotten that the tails of

the king's ermine pointed down, and had painted them up. The reader

may see the real Richard II, in the Jerusalem Chamber now.

As remarkable in its way is the ponderous panel on which the

life-sized king was painted. It is more than an inch thick, and is

composed of three planks of oak, not only as sound as when they were sawn

five hundred years ago, but as unwarped as a plane of steel. Mr.

Hans Holbein, who believed himself a descendant of his famous namesake,

could not by a microscope discover the suture where the clever carpenter

who made it had joined the panel.

At the Lodge the ground rent exceeded £23, and house charges

were considerable. Merritt occupied four rooms; the two chief having

folding doors, made him a spacious studio. He took up the whole time

of a servant, and the Lodge grounds were yielded to him for recreation.

Here he paid £1 a week. Like most persons born and reared in

indigence, he was alarmed at any new expense, even when he could well bear

it. He was distressed and apprehensive even at this charge, and

never paid more to the end of his tenancy. But I had other interest

than profit in continuing it. It was partly friendship—partly

liking, and partly the love of seeing pictures, curious or choice, about

my rooms—a pleasure otherwise unattainable by me. It was diverting

in another way to see, in the earlier years, the straits of

impecuniousness in artist life. Well I remember when at Woburn

Buildings, Mr. Parrington, a friend of mine, called with a picture for

Merritt to test or restore. It happened he had no solvent of any

kind by him, by which he could clean the surface or remove encrustations

of varnish. Then Mrs. Holyoake secretly sent out for what he wanted,

so that the visitor might not be aware of its scarcity; for a patron with

a valuable picture would be loathe to leave it if he suspected the need of

the artist might lead him to pledge it. Then when the solvents came

it was found that there was no linen with which to apply or absorb them at

the critical moment, when the household collection had to be drawn upon,

and sent into the studio—as from a store-room where he was supposed to

keep his rolls of old soft linen.

Besides the interest of these episodes, Merritt was

ordinarily excellent company to talk to, or contradict. As Hartley

Coleridge said of one of his friends:—

|

"Fine wit he had—and knew not it was wit

And native thoughts before he dreamed of thinking;

Odd sayings, too, for each occasion fit,

To oldest sights the newest fancies linking." |

What I most honoured my friend for was his honesty in art. By

falsifying pictures, making new ones look old, and finding the signature

of the master under the paint where it had never been put, inventing for a

picture a pedigree and a character, he might have made money as others

did, but he preferred poverty to deceit. After many years he had his

reward. He could be trusted. He was known to know his art; his

word could be believed, and his opinion was worth money.

Connoisseurs so eminent as Mr. Gladstone in Merritt's later years

consulted him.

My brother William, Curator of the Art Schools of the Royal

Academy, was useful to Merritt, as he was to others in his way; but

Merritt could not paint, and therefore he could be trusted to restore.

He had colour in his blood. He had the patience of Gerard Dow (whom

Merritt was fond of citing), who was said to spend days in painting a

broom. I have seen Merritt spend days over a few inches of injured

canvas, until, by careful stipling, he matched the colours, and replaced

the lost tints, so that no ordinary eye could tell where the effacing

fingers of neglect or decay had wrought mischief. No one who could

paint could be depended upon to take this trouble, when he could in an

hour paint in the defective parts; whether such a one could do it better

or worse, or as well, he would not represent the genius of the master nor

restore his work.

When we lived at No. 1, Woburn Buildings, a window overlooked

the grounds of Charles Dickens, who resided then at Tavistock Place, made

Merritt's working-room the best room, because it looked on trees. On

Sundays Dickens would have a friend or two in the garden, and a tray of

bottled stout, "churchwardens," and tobacco would be brought from the

house. We were told that this was Dickens's protest against the

doleful way of keeping Sunday then thought becoming. Tavistock House

was the one formerly occupied by "Perry of the Morning Chronicle," as he

used to be described, but in my time it was divided into two houses.

One was occupied by Frank Stone the elder, who died there—a very genial

person to know. The other was occupied by Sidney Milnes Hawkes,

afterwards by Mr. James Stansfield. Mazzini was frequently there in

those times. One morning, when Dickens resided there, a person

purporting to be Mazzini called, and solicited aid. Dickens sent

down a servant, who presented a sovereign on a silver tray. The

visitor took the gift with thanks. When this came to be known to

Mazzini's friends they were filled with amazement at Dickens's

thoughtlessness, to say the least. How could he imagine that a

gentleman whom he had met in society, as a man of reputation for honour

and self-respect, would come to his door soliciting alms, like an

adventurer or an impostor? And, if he believed the applicant to be

Mazzini, some inquiry, some commiseration and identification was necessary

to make sure that one so eminent was suddenly in distress so abject.

Mazzini had a hundred friends who would have aided him before he need have

been a suppliant at Dickens's door.

Though he hardly knew it, Merritt had the ambition of

authorship in him, but he cost me infinite trouble to make him believe it.

He began by writing for me in the Reasoner under the signature of

"Christopher." Sometimes I suggested the subjects, and revised what

he wrote. At length I urged him to write about his own profession,

as nothing distinctive or readable existed upon it. At last he wrote

some chapters on the Art of Restoration. At that time Mr. Hans

Holbein, then stationmaster at Euston, was frequently at my house.

His passion was to collect all the engravings of Holbein he could afford

to purchase. He induced Merritt to call his little treatise "Dirt

and Pictures Separated"—a purely technical title which could interest

nobody but connoisseurs. I added the line "in the Works of the Old

Masters" to render the title more human. At that time Merritt was

not apt with his pen, but there was originality and fervour in him which

showed he had literary taste. He had read no books save odd volumes

of the letters of Pope, Defoe, or an old dramatist or two, which he had

picked up on second-hand bookstalls. He had had no education save

the Charity School sort—Church Catechism chiefly, which leaves a youth

helpless and abject in the battle of life. But he had the education

of the streets—an excellent school for those who have sense enough to

learn in it. He knew that an acquaintance of mine who made a name as

a tragedian had learned grammar from a book I had written, which he had

read when he resided in the house of my sister Caroline. I had put

on the title-page of the book the words:—"No department of knowledge is

like grammar. A person may conceal his ignorance of any other art;

but every time he speaks he publishes his ignorance of this. There

can be no greater imputation on the intelligence of any man than that he

should talk from the cradle to the tomb, and never talk well."

These words incited Merritt, who had the instinct of a simple

and manly style in him. Like every person of taste, he was

dissatisfied with his first efforts, not only dissatisfied but dismayed

and despairing, and threw his chapters on Restoration six or seven times

into the fire, where they would have perished had not my wife rescued them

until a more hopeful mood came to him. Again and again they were

enlarged and improved, and again thrown on the fire. To encourage

him, I induced the editor of the Leader newspaper, by my accounts

of their intrinsic excellence, to publish them in the "Portfolio" of that

journal, were the chief chapters first appeared.

To this end I invented reasons to prove their insertion would

be relevant, and wrote the introduction to the chapters in the Leader,

and also a handbill about them, which was sent out to artisan readers in

all the towns where I was in the habit of speaking. What I said was

this:—

"The interesting discussion which several times has arisen respecting the

preservation of the pictures in the National Gallery renders it necessary

that every man having regard to the credit of the nation in this respect

should be able to form an intelligent opinion upon pictures.

"Hitherto this has not been practicable to the mass of the

people, because nearly all works on the subject of painting are written

from the professional point of view, and abound in technicalities

unintelligible to the general reader.

"Newspaper criticisms are usually written for the initiated

alone. The editor of the Leader, therefore, has thought it useful to

insert a series of

PAPERS ON THE

PAINTINGS OF THE OLD MASTERS.

which are written

in popular language, and by explaining the artistic processes employed in

creating a great painting, and in restoring it when unhappily damaged by

accident, time, or neglect, shall enable the general reader to understand

pictures and learn to appreciate them, and take part in the discussions

which relate to them.

"A great painter sheds renown on his country, and refinement

on all people who have the good fortune to gaze on his work. Taste

for the fine arts is a proof of the civilisation of a nation.

English artisans would not be behind those of any on the Continent, if

knowledge of the right kind was submitted to them. The names of

poets and philosophers are become household words in our land—why should

not the painters become equal favourites? They would if equally well

known. If political economists and politicians attain popularity,

surely the day of the great artists is come. Raphael sounds as well

as Ricardo, Titian may stand by Torrens, the canvas of Correggio is as

attractive as Cobbett's Paper against Gold."

Had the Leader not possessed that heroic sentimentality in favour

of usefulness which practical men despise, Merritt's papers had never

appeared. He was paid, as I considered, liberally, but such was his

nature that he was dissatisfied, although it was the first money he

received for any writing, save such limited compensation as I was able to

make him for his papers in the Reasoner.

The name of the errand boy of Oxford appearing in the

Portfolio of a famous journal, with those of George Eliot, Herbert

Spencer, Harriet Martineau, and George Henry Lewes, was reputation.

Merritt had not the money to purchase the distinction, and could not have

bought it if he had. Yet it was not until I threatened to abandon

him that he gave up his purpose of writing to the office a letter of

discontent at his payment. He was as difficult to befriend as

Rousseau. Yet his papers in the Leader were the beginning of

his fortune. He became known to connoisseurs who otherwise had never

heard of him. Mr. Boxall (afterwards Sir William) could then afford

to know his Bohemian townsman.

The chapters would have ended with the Leader had I

not induced him to complete them and make a little book of them, which I

printed in the "Cabinet of Reason" series, although the subject was not

suited thereto. The preface was wholly mine, and the table of the

painters named in the work. In concert with its purpose, I added

here and there in the book remarks to enlist the interest of outside

readers in a subject which would strike them as being alien. The

publication brought him picture clients from he provinces. The book

had a new kind of genius, and the genius was all his own. It showed

knowledge, devotion, and enthusiasm, qualities Merritt alone put into the

book.

CHAPTER CII.

THE PICTURE RESTORER FURTHER DELINEATED.

(1847-1877.)

HENRY MERRITT had some

delightful qualities, but he was the most timid, the most irritable

and inconsistent of all the children of genius whom I have known. He

now possessed the status the Leader had given him. Next opportunity

occurred of introducing him to the Empire, set up by Mr. Livesey, the

founder of Teetotalism. The editor was John Hamilton, who had the

passion of a prophet in him, and with whom I had public discussion, and

for whom I had great regard. Hamilton became editor of the

Morning Star, and Merritt came to write on art in both papers.

Through the Star, he contributed for a time to the Manchester

Examiner, and he went to Manchester on the occasion of an exhibition

of pictures in that city. Then I was able to give him an

introduction to Mr. Stephen Pettitt of Merchants' Hotel, where he made

friends and had pleasant days. It was a pleasure to me to be useful

to him.

An intimate friend of mine on the staff of the Standard, Mr.

Percy Greg, was a constant visitor at my house, and I enlisted his

influence to obtain the appointment of Merritt as its art critic.

When he came home in Gallery days he was sometimes unable to write out his

notes in time for the Standard the same night. Then it fell

to me to write them out for him, which involved many hours of close work.

Sometimes this occurred two or three times in a week. For no week,

even when I spent the day at the Gallery, did I receive more than £1 for

work for which he received £6. Nor should I have taken what I did

had not this work prevented me from doing my own. He would have been

as ready to help me in like case.

When, in a season of illness, he was unable to attend the

Galleries, he would ask me to go and make notes for him. Devoid of

his critical knowledge of pictures, long familiarity with them enabled me

to describe their features and the story the artist had told by his

pencil. Merritt found from the art notices in other newspapers,

which he subsequently perused, that my reports were to be trusted.

He knew the kind of work produced by each artist who habitually exhibited.

His notices sent to the Standard, written upon my report, were confined to

descriptions of the subjects and the general characteristics of the

painters, reserving technical criticisms until he was able to run down to

the Galleries and see for himself. On the occasions when I went for

him some droll experience befell me, such as recalled Boswell in a

forgotten passage, preserved by Hazlett in his "Memoirs of Thomas Holcroft."

The comedian, who knew Boswell, records in his diary that one morning

Boswell, calling on Johnson, found him writing a letter for a Mr. Lowe.

On Lowe leaving, Boswell followed him, and with insinuating professions

began: "How do you do, Mr. Lowe? I hope you are very well, Mr. Lowe.

Pardon my freedom, Mr. Lowe, but I think I saw my dear friend Dr. Johnson writing a letter for you." "Yes, sir." "I hope you

will not think me rude, but if it would not be too great a favour you

would infinitely oblige me if you would just let me have a sight of it.

Everything from that hand is so inestimable." "It is on my own

private affairs." "I would not pry into any person's affairs, my

dear Mr. Lowe, by any means. I am sure you would not accuse me of

such a thing, only if it were no particular secret." "Sir, you are

welcome to read the letter." I thank you, my dear Mr. Lowe; you are

very obliging. I take it exceedingly kind" (having read it).

"It is nothing, I believe, Mr. Lowe, that you would be ashamed of."

"Certainly not!" "Why, then, my dear sir, if you would do me another

favour, you would make the obligation eternal. If you would but step

to Peele's coffee-house with me, and just suffer me to take a copy of it,

I would do anything in my power to oblige you." "I was overcome,"

said Lowe, "by this sudden familiarity and condescension, accompanied with

bows and grimaces. I had no power to refuse; we went to the

coffeehouse, my letter was presently transcribed, and as soon as he had

put his document in his pocket, Mr. Boswell walked away as erect and as

proud as he was half an hour before suppliant, and I ever afterwards was

unnoticed." Lowe added that he was left to pay for the coffee he had

ordered to give Boswell opportunity of copying his letter.

A countryman of Boswell's, one of the habitual critics of the

Galleries, knew me well, and would come to me in the most desultory way,

with cordial greetings and incidental inquiries as to "what paper I wrote

for," "why was I there," and "whom did I represent." I then wrote

for three papers, but not upon art subjects. "Did I write art

notices for them?" he would inquire. "Merritt writes for the

Standard, does he not? Is he here?" Beguiled by cordial

familiarity, I incautiously said "my friend was unwell, and I was looking

round for him." Immediately he mentioned in the paper for which he

wrote—the Reader—that Mr. Merritt's criticisms in the Standard

were done by another hand. This would have given great pain to

Merritt, whom my questioner knew and for whom he always expressed the

greatest regard. Had the treacherous information come under the eyes

of the Standard, it might have cost my friend his appointment.

When the inquisitive critic next put his familiar question to me, I said

"his solicitude was very interesting, but I observed he never prefaced his

inquiries by informing me what he was doing and for what paper he was

writing." His curiosity there and then ceased. I suspected him

of seeking Merritt's place. Of course I kept the incident from

Merritt, and kept the Reader out of his sight.

Mr. Merritt remained art critic of the Standard until

the time of his death. His criticisms were written on a theory we

had often discussed; it was that of subordinating merely technical

criticism, giving mainly an animated description of the character of the

pictures and design of the painter, with his characteristics as an artist.

By limiting technical criticism to such points as were necessary for the

connoisseur and picture buyer, and describing in what respect the pictures

were additions to the scenic glory of art, his notices were always, and

are still, readable, and they sent more persons to the Galleries to see

the pictures for themselves than any other art criticisms of his time.

Art critics mostly wrote not to interest the public in art, but to show

off their skill as critics; just as most books on education are written,

not to explain difficulties to uninformed students, but to show how much

the author is better informed than his rival teachers. Always

distrustful of his own work, Mr. Merritt cast aside his criticisms after

they appeared. I kept copies of them all, and made them up into four

volumes, which he afterwards was glad to refer to and show.

"Robert Dalby and his World of Troubles," Merritt's best

work, I copied out several times for him. The "Oxford Professor,"

which he never finished, I was to re-write for him, just so far as to show

him my idea how it should be treated. In everything I did for him, I

did but polish the diamond: the diamond was his, not mine. Merritt

had no inside life. In description of outside life he had genius.

Separate passages were perfect and inimitable. He attained a

spontaneous grace which change could only mar. This needs no

testimony, since Mr. Ruskin wrote to him:—

"You have given great pleasure to

Carlyle by your report, and you always give much to me whenever you write

to me. I have no other friend who says such pretty things to me, in

a way that reminds me of the little courtesies of old days, when people

were graceful by kind act in a letter as much as in a quadrille, and when

flattery was the naughtiest of one's faults to one's friends—never

carelessness."

In later years, when we were still home companions, Merritt's health

became precarious. For two years his life was a daily uncertainty.

The whole household was absorbed in attending upon him. Often I rose

once or twice in the night, and went to his room to see if he were alive,

or needed aid. After he had left me, he was again in danger, and

when he became delirious I sat up all night with him. When his death

occurred I wrote a solicitous letter to the editor of the Standard

to procure the art criticship for one to whom he had left his fortune, as

I was always willing to serve any one whom a friend of mine befriended.

Merritt never married until within a few weeks of his death.

Though a Bohemian in freedom and precariousness, he was Bohemian in

nothing else; yet all his life his most amusing satire had been upon the

peril and subjection of marriage, and he could not bear to tell me or any

one that he had married. On his death I made it known in the papers,

that she whom he had married might not be exposed to incredulity, for none

of his friends would have otherwise believed in his marriage. The

last time I saw him, scarcely a fortnight before he died, he besought me

to come to him soon, as he had many things to tell me. He said that

in his will he had left small bequests of £50 each to two of my children,

but he should arrange to fulfil another promise he had often made. I

received a telegram from a common friend summoning me from the country, as

he was in great danger. I at once returned, but he was in other

hands, and no opportunity occurred to me of seeing him again. He had

no idea that his days would be so short, and thought he had time to do

everything he meditated. He bequeathed shortly before his death

several thousand pounds which he had honourably earned, and never doubted

that he should earn more for his own use.

After his death, what purported to be a "Memoir" of him

appeared by persons who had not known him long, and were unacquainted with

the circumstances of his life, in which it was said that "the persons

with whom he lived shared the benefits of his increased earnings."

Again, "It was touching to see how often he supplied one family especially

who depended upon him for every comfort with the means of that enjoyment

in the country or by the sea-shore, while he remained at home literally to

work for them." A reference to Merritt's friend and townsman, George

Hooper, was still worse. Mr. Basil Champneys, the editor of the

book, vouches that these things" are done with perfect tact and graphic

fidelity." I attempted to obtain some correction of these statements

from the editor and the publisher, but found I had no resources to obtain

it legally, and expectation of its being done from a sense of justice

there was none. Besides my family, some eminent friends in London

and many friends elsewhere who would see the book, knew of Merritt's long

residence with me, and that these references related to me. After

fourteen years there comes to me this opportunity of correcting them.

Merritt had all the irascibility of the artist, but he was

honourable and truthful at heart, and would have been very wild had he

lived to see these statements made in his name. All the years he

resided with me we seldom went to the country or seaside but we took him

with us, increasing our expenses to which for many years he was unable to

contribute his share. His querulousness with our friends always

embittered our days, and made us glad when the unpleasantness ended.

To do him justice, he regretted this, but could not help it, and he strove

to make amends in his way. I used to say to him he was like Dr.

Johnson's good-natured, angry man—"he spent his time in injury and

reparation." When he came to acquire means of his own he became more

insupportable, and, as his income was good, I besought him to take

apartments elsewhere. He wrote to me saying "I was killing him, as I

had given him nineteen notices to leave my house." Were I "living

upon him," it was very injudicious in me to beseech him "nineteen times"

to do me the favour of going away. To mitigate the tone of my

request, I used to repeat the lines of Martial—

|

"In all thy humours, whether grave or mellow,

Thou'rt such a touchy, testy, pleasant fellow,

Hast so much wit and mirth and spleen about thee,

That there's no living with thee nor without thee." |

But I could "live without him," and I had ceaseless relief when I recovered the control

of my house.

He did leave at length, but my personal regard for him never

changed, nor his for me. Not long before his death he wrote to my

friend Major Bell, saying, "It is nearly thirty years since my friendship

for Holyoake commenced, and it is not likely to terminate till death."

When a person has arrived at years of discretion (some arrive

very late, I am afraid: I have not reached that period yet), he sees many

things which were always palpable, but which he did not observe until

experience opened his eyes. Then he sees irritating things

dispassionately. Many times I have tried to analyse the complex

character of my artist friend. I often say of the inhabitants of a

famous town which I know well, that God has given to them more humility

and more pride than He has vouchsafed to any other collection of His

creatures. Merritt was not born on the Tyne, but he had these

qualities. He had an insatiable expectancy of the recognition by

others of qualities he disclaimed having. Charles Lamb excelled all

English humourists in the American wit of exaggeration. When, he

said, Coleridge met him on his way to the India House and took him by the

button to discourse to him, he, with his penknife, deftly released

himself, and on returning in the evening found Coleridge still holding the

button, preaching to it. No one misunderstood Lamb, who merely put a

halo round a fact which he left palpable. Merritt, with less than

Lamb's art and genial restraint, had the bright gift of enlargement, and

misled, without meaning it, those who did not know him.

We say of some men that they are nervous, meaning all the

while that they have no nerves. Merritt had none. But, in lieu

of them, he had a set of organised electric filaments, which, the moment

you touched him with a harmless phrase, gave you a shock. He was the

first person in whom I observed supernatural sensitiveness, who, starting

at the slightest reflection upon himself, would say habitually things

which it exceeded mortal self-respect to tolerate. In those moods

you avoided him, and forgave him because it was his nature, to which he

had never taught restraint. When he became eminent he kindly

undertook to teach my eldest son his art. It was a distinction to be

his pupil. But, with frequent kindness, there were outbursts of

imputation which imperilled manliness itself to submit to. I have

seen his best physician refuse further to attend him in consequence of his

porcupine episodes. Yet, being just at heart, he would, like

Carlyle, speak generously of the same persons, and, if others disparaged

them, would defend them with many a bright and graceful phrase.

Merritt thought that no one would remember what he never meant. Had

I not known what heredity and circumstances do for all of us, I should

have had sharp and permanent contempt, where I had only compassion and

forbearance. Pained as an honourable man is that his nature should

so betray him against those whom he regards, Merritt made, when he had

means, what reparation he could by gifts. These he made to persons

in whom I was interested, which was his way of giving me (as he thought)

pleasure. In vain I besought him not to do it. For myself, I

never had any gift from him, nor did I seek one, and he knew it.

Thus in some instances he destroyed my natural authority by attracting

expectation to himself, and left me a legacy of mischief which made me say

on one occasion that Merritt with the best intention brought great misery

on others and requited some one else. His friendship was a pleasure

to me and a misfortune. Merritt had the elements of a noble

character in him, and, counting the disadvantages which he surmounted and

the eminence he attained in art and in literature, owing everything to his

honesty and skill, he deserves a place in the annals of remarkable men.

A wise ancient said, "Know thyself." Merritt did not know himself.

Of all knowledge possible to him he lacked this alone.

CHAPTER CIII.

ERNEST JONES,

THE CHARTIST ADVOCATE.

(1848-1867.)

|

|

|

Ernest Jones

(1819-69) |

I

OWN I have the sympathies of Old Mortality. In

my time I have perpetuated the memory of many unregarded heroes, who gave

their strength, and in some cases their lives, in defence of the people

who had forgotten, or who had never inquired, to whom they owed their

advantages.

Ernest Charles Jones will, however, be long remembered by

Chartist generations. He was the son of a Major Jones, of high

connections, who had served in the wars of Wellington, and was at

Waterloo. He was subsequently equerry to the Duke of Cumberland,

afterwards Ernest I. of Hanover, and uncle of Queen Victoria.

Major Jones's mother was an Annesley, daughter of a squire of Kent.

His only son, Ernest, was born in Vienna, in January, 1819. His

father having an estate in Holstein, on the border of the Black Forest,

Ernest Jones passed his boyhood there, and in 1830, when eleven years old,

he set out across the Black Forest, with a bundle under his arm, to "help

the Poles." With a similar precarious equipment, he in after years

set out to help the Chartists. He was educated at St.

Michael's College in Luneburg, where only high-caste students were

admitted, and where he won distinction by delivering an oration in German.

In 1838, he became a regular attendant at the English Court, where he was

presented by the Duke of Beaufort. He married into the aristocratic

family of Gibson Atherley, of Barfield, Cumberland, the name being borne

by his son Atherley Jones, now member of Parliament. We of the

Chartist times all knew the gentle lady who lived in Brompton during the

dreary days of her husband's frightful imprisonment.

In 1844, Ernest Jones was called to the Bar of the Inner

Temple. All along he had high tastes and high prospects. Thus

he was reared under circumstances which did not render it necessary that

he should have any sympathy with the people. But the inspiration of

poetry came to him. The influence of Byron may be seen in his verse.

He had no mean capacity of song. With better fortune than befell him

when he had cast his lot with Chartism, and with more leisure, he would

have been a poet of mark: but he threw fortune away. His family did

not like the idea of his being a Chartist rhymer. His uncle, Holton

Annesley, offered to leave him £2,000 a year if he would abandon Chartist

advocacy. If not, he would leave the fortune to another—and he did.

Mr. Jones must have had in him elements of a valorous integrity to refuse

that splendid prospect. He knew well what he was about, and that the

service of the people would not keep him in bread. They whom he

served were not able to do it—they had too many needs of their own.

He had declined his uncle's wealthy offer in terms of noble but disastrous

pride, and the fortune he relinquished was given to his uncle's gardener.

Though he had chosen penury, he retained the patrician taste natural to

him, and made a point of not taking payment for his speeches and

addresses. There was more pride than sense in this. Those who

consumed his days in travelling and his strength in speaking could and

would have made him some remuneration. Without it his home must be

unprovided. Making a speech has as fair a claim to payment as

writing an article. Honest oratory is as much entitled to costs as

honest literature. Mr. Jones often walked from town to town without

means of procuring adequate refreshment by day or accommodation by night.

On some occasions an observant Chartist would buy him a pair of shoes,

seeing his need of them. Ernest Jones published the People's

Paper—the sale of which did not pay expenses. The sense of debt

was a new burden to him. On one occasion when I printed for him, and

he was considerably in arrears, he said, "I must go to my friend

Disraeli." An hour later he returned, and handed my brother Austin

three of several £5 notes. He had others in his hand. That

politic Minister inspired many Chartists with hatred of the Whigs, whom he

himself disliked, because they did not favour his circuitous pretensions;

and when he found Chartists of genius having the same hatred, he would

supply them with money, the better to give effect to it. I never

knew any Chartist in the habit of taking money, who took it for the

abandonment of his principles; nor do I believe Disraeli ever gave it them

for that purpose. Their undiscerning hatred answered Tory ends.

It was July, 1848, when Mr. Jones was sentenced to two years'

solitary imprisonment, and to find two sureties of £100 each and himself

£200 for three years after his release—for saying, "Only organise, and you

will see the green flag floating over Downing Street; let that be

accomplished, and John Mitchell shall be brought back again to his native

country, and Sir G. Grey and Lord John Russell shall be sent out to

exchange places with him." This was simply amusing, and there was no

more danger of this happening than of a flock of pigeons stopping a

railway train. In the same speech for which he was condemned, he

gave the same advice to the meeting that I had given to the delegates to

the Convention in the John Street Hall, on the night before the 10th of

April, 1848.

When Jones was imprisoned, it was sought to humiliate him.

The Whigs did it, but the Tories would have done the same—yet the Whigs

were more bound to respect the advocates of the people. Jones was

required to pick oakum. Being a gentleman, he refused to be degraded

as a criminal. Politics was not a crime. In the case of

Colonel Valentine Baker, the Government had just respect for a 'gentlemen;

but not when the gentlemen was the political advocate of the poor, though

Jones was socially superior to Baker.

Mr. Jones was kept in solitary confinement on the silent

system—enforced with the utmost rigour for nineteen months. He

complied with all the prison regulations, excepting oakum picking.

That he steadfastly refused, as he would never bend himself to voluntary

degradation. To break his firmness on this point he was again and

again confined in a dark cell and fed on bread and water.

When suffering from dysentery, he was put into a cell in an

indescribable state from which a prisoner who died from cholera had been

carried. It may be reasonably assumed that it was intended to kill

him. The cholera was then raging in London, and, had Jones died, no

question would have been asked. Still the authorities never

succeeded in making him pick oakum.

In the second year of his imprisonment he was so broken in

health that he could no longer stand upright, and was found lying on the

floor of his cell. Only then was he taken to the hospital. He

was told, if he would petition for his release and abjure politics, the

remainder of his sentence would be remitted. This he refused, and he

was sent back to his cell. Let anyone consider what those two dreary

years of indignity, brutality, peril, and solitude must have been to

a man like Ernest Jones—nervous, sanguine, ambitious, with his fiery

spirit, fine taste, and consciousness of great powers—and restrain if he

can admiration of that splendid courage and steadfastness.

Unregarded, uncared for, he maintained his self-respect. Thomas

Carlyle went to look at the caged Chartist through the bars of his prison,

and increased, by his heartless and contemptuous remarks, public

indifference to the fate of the friendless prisoner. Carlyle wrote:

"The world and its cares quite excluded for some months to come, master of

his own time, and spiritual resources to, as I supposed, a really enviable

extent." This shows that, like meaner men, Carlyle could write

without facts, or even inquiring for them. Ernest Jones, "master of

his own time," had to pick oakum, or spend his days in a dark cell.

Thus his "spiritual resources" were limited. He was refused a Bible

even, and had to write with his blood. His "really enviable"

condition was that of knowing that his wife was ignorant whether he was

dead or alive, and he was denied the knowledge what fate in the cholera

season had befallen her or his children, for whom no provision existed.

In his savage imprisonment he did write poems, but it had to

be done with his own blood—not from sensationalism, but from necessity,

pen and ink being denied him. Undaunted, he returned on his

liberation to his old advocacy of the people. Mr. Benjamin Wilson,

of Salterhebble, Halifax, who knew Jones well, has given many facts not

before known of his career in the "Struggles of Old Chartists."

Ernest Jones and I were associated in Chartist agitation

while it lasted. I was a visitor at his fireside at Brompton.

Mrs. Ernest Jones, a lady of great refinement, shared the

vicissitudes of his Chartist days, which shortened her own. Mr.

Jones left London in 1859, and went to Manchester with a sad heart.

Practice at the Bar had to be won. One night, after attending the

court at Leeds, he was met by Mr. Moses Clayton, who found he had no home

to go to. A home was found him at Dr. Skelton's, and a brief

also next day. He had come to the resolution that night that he

would see no morning. Afterwards better fortune came to him.

He had the chance of being member for Dewsbury. He was nearly

elected member for Manchester, and the reversion of the seat to him was

likely when he suddenly died. His grand energy, fatigue, and

exposure killed him. Had he reached Parliament, he had all the

qualities which promised a great career there. Shortly before his

death he spent some hours with me in my chambers in Cockspur Street,

overlooking Trafalgar Square, discussing a favourite theory of his—the

manner in which an actor on the stage of the world should quit it.*

In every workshop in Great Britain, in mine and mill, and in

other lands where his name was familiar, there was sadness when his death

was known. His friend in many a conflict, George Julian Harney, sent

from America to the Newcastle Daily Chronicle an impassioned

account of the effect of the news on him as he read it in a telegram in

Boston.

Mr. Jones had a strong musical voice, energy and fire, and a

more classic style of expression than any of his compeers in agitation.

When he spoke at the grave of Benjamin Rushton of Ovenden, he began:—"We

meet to-day at a burial and a birth—the burial of a noble patriot is the

resurrection of a glorious principle. The foundation stones of

liberty are the graves of the just; the lives of the departed are the

landmarks of the living; the memories of the past are the beacons of the

future."

Despite his popular sympathies and generous sacrifices for

the people, the patrician distrust of them, now and then, broke out, as

when he wrote:—

|

"Ill fare the men who, flushed with sudden power,

Would uproot centuries in a single hour.

Gaze on those crowds—is theirs the force that saves?

What were they yesterday?—a horde of slaves!

What are they now but slaves without their chains?

The badge is cancelled, but the man remains." |

There is some truth in these lines. The abatements I take to be

these:—1. You can't "uproot centuries" if you try. 2.

The "crowds" are always better than they look. 3. The "slaves"

are always free in spirit long before they get rid of "their chains." 4.

When the "badge is cancelled," the "man" who "remains" generally turns

out a gladsome, practical creature.

In the nobler vein which so well became him, he vindicated

with a poet's insight his own career:—

|

"Men counted him a dreamer? Dreams

Are but the light of clearer skies—

Too dazzling for our naked eyes.

And when we catch their flashing beams

We turn aside and call them dreams.

Oh! trust me every thought that yet

In greatness rose and sorrow set,

That time to ripening glory nurst,

Was called an 'idle dream' at first." |

Mr. Morrison Davidson has published the most comprehensive sketch of the

career of Ernest Jones which has appeared, and a noble volume might be

made of his poems, speeches and political writings. Because he

opposed middle-class projects and broke up their meetings, little

attention was paid to his views by those who would have been most

impressed by them. Before their day he was as well informed as Karl

Marx or Henry George on questions of capital and land, and held eventually

wider views of co-operation than were advocated in his time. It

would have been economy to mankind to have pensioned Ernest Jones, that he

might have devoted his genius to oratory, literature, and liberty.

Those of this generation who have not in their memory any

instance of Ernest Jones's eloquence, may see it in the following passage

from his Lecture on the Middle Ages and the Papacy.

“You have been

told that the Church in the Dark Ages was the preserver of learning, the

patron of science, and the friend of freedom. The preserver of

learning in the Dark Ages! It was the Church that made these ages dark.

The preserver of learning! Yes, as the worm-eaten oak chest preserves a

manuscript. No more thanks to them than to the rats for not

devouring its pages. It was the Republics of Italy and the Saracens

of Spain that preserved learning—and it was the Church that trod out the

light of those Italian Republics. The patron of science! What? When

they burned Savonarola and Bruno, imprisoned Galileo, persecuted Columbus,

and mutilated Abelard? The friend of freedom! What? When they crushed the

Republics of the South, pressed the Netherlands like the vintage in a

wine-kelter, girdled Switzerland with a belt of fire and steel, banded the

crowned tyrants of Europe against the Reformers of Germany, and launched

Claverhouse against the Covenanters of Scotland? The friend of freedom!

When they hedged kings with a divinity! Their superstitions alone upheld

the rotten fabric of oppression. Their superstitions alone turned

the indignant freeman into a willing slave and made men bow to the Hell

they created here by a hope of the Heaven they could not insure hereafter.

There is nothing so corrupt that the Papacy has not befriended, and but

one gleam of sunshine flashes across the black picture, in the

architecture of its churches, the painting of its aisles, and the music of

its choirs."

Note: After his death an "Ernest Jones Fund " was

proposed. Lord Armstrong, then Sir William, sent two guineas to the

Punch office, which was sent to me for the Fund.

CHAPTER CIV.

PARLIAMENTARY CANDIDATURE IN LEICESTER.

(1884.)

THE Liberals of Leicester had sent deputations to

London in support of Mr. Bradlaugh, who was excluded from his seat in

Parliament on the ground of atheistical opinions, which were held to

disqualify him from taking the oath. The appearance at the bar of

another member equally disqualified to make oath would have strengthened

the argument for affirmation. A vacancy occurring at that time in

the representation of the borough, I offered myself as a candidate.

My primary qualification consisted in my being the only public man in

England—not a Quaker—who on no occasion and for no private or public

advantage had ever taken an oath. I made it clear that, if chosen as

member for Leicester, I should take no oath either by speech or pantomime,

nor profane the oath in the opinion of men of Christian conviction, by

solemnly repeating words which indicated no corresponding belief in my

mind. But if any tribunal, exacting the oath and knowing my

opinions, treated the oath as a mere secular undertaking of good faith,

there would be neither profanity nor deceit in taking it, though there

would be repugnance in using a form of words otherwise disingenuous,

ambiguous, and misleading.

Apart from this question, the chances were against me, as I

had been long known as one having decided views on public questions;

whereas the most presentable candidates are men who have spoken no word of

principle—written no books—made no effort—taken no side—professed no

principle—helped in no contest—shared in no sacrifice—served in no forlorn

hope. Men who have done nothing, who are uncommitted to anything,

and upon whom no one has any reason to depend, are the candidates mostly

chosen. The cowards who kept on the outskirts of the field while the

fight was going on—all the supine and superfine, who sat before the cosy

fire with their feet upon the fender, while the combatants were out in the

tempest—find laid at their feet the spoils of progress which others have

won.

As to my professions, I said I was no Tory Radical,

professing to be more "advanced" than anybody else, and helping the enemy

on every occasion. I was no Social Democrat, offering the people

comfort as a charity instead of putting in their hands the right and means

of commanding it by honest effort. I was no reformer by

confiscation. I was not a Liberal who would trust, without

conditions, the wise with the fortunes of the many, nor the many with the

fortunes of the wise, nor set one against the other—but would charge both

equally with responsibility for the honour and welfare of the State.

I followed the path of the great Minister who brought in our new Franchise

Bill. All other Ministers bringing in Reform Bills have studied how

many they could exclude from it. Mr. Gladstone has been the first

Minister who has studied how many he could include in it. I am for

trusting the Minister who trusts the people, and for supporting with my

vote that foreign policy which is just without sentimentality—brave

without swagger—which keeps faith with treaties adversaries have

made—fights with English courage for English honour, and does not

knowingly murder for prestige.

Mr. Herbert Spencer's opinions on Parliament were published

at the Leicester election. He, being a thinker and an opinion maker,

was well fitted for Parliamentary service. He, however, declined, as

he was for individuality and for independence of the views of

constituencies. On Mr. Spencer's principle every man would have his

will and nobody have his way. He thought "the influence possessed by

members of Parliament" was rated too high—the representative being too

"subject to his constituents." Mr. Spencer held that "laws were

practically made out of doors and simply registered by Parliament."

He, like Lord Sherbrooke, regarded the duties of the delegate as merely

mechanical. Yet could there be a nobler function discharged or

nobler office filled than that of explaining the opinions of those who had

no other way of being heard save by the mouth of their member? Is a

member a machine because he is a delegate? Where is there such a

delegate as a judge upon the bench? His instructions are not merely given

by word of mouth, or at a poll, but discussed in Parliament, fixed with

strictness and printed in books; so that the instructions of a judge are

so defined that, when perfect, he can neither misunderstand nor

misinterpret them. And yet is there not scope on the Bench for the

greatest forensic genius? If a delegate to Parliament was confined

as a judge is, he would have ample scope for his independence and

individuality. But there is a much wider margin in Parliament.

Many who were prominent in smaller circles, as in the Vestry or Town

Council, found themselves powerless in Parliament, because there was

required more art and persuasiveness—there a man has to see farther, to

hear more, to understand better, to master all the points pertaining to a

question, to accord regard to the convictions of others, and present a

question in a light so clear, and with arguments so conclusive, that he

can create conviction on the side of public justice. There is no

assembly in the world where there is greater room for the display of the

highest powers in representing a constituency, interpreting its views,

maintaining them when assailed, and, when need demands, storming the

fortresses of the enemy.

There were in Parliament several members disqualified like

myself by conviction from taking the oath, and Leicester was the one town

most likely to be desirous of opening a door through which an honest man

might enter the House of Commons without humiliation. It proved not

to be so, and thus my candidature ended.

CHAPTER CV.

THREE REMARKABLE EXILES.

(1884.)

ENGLAND has often been enriched by the inventive

genius of industrial exiles who have sought our shores for religious

liberty. Not less has it been indebted to political exiles, who,

seeking freedom here, extended it by their teaching and exalted it by

their example.

|

|

|

Louis Kossuth, Hungarian patriot

(1802-94) |

Kossuth was the chief of the few foreigners who took at once

a high place as a public speaker in a new tongue. No sooner had he

landed than he appeared as an English orator, displaying not only mastery

but imposing force. Neither Bright nor Gladstone had then attained

like ascendency on the platform, and Joseph Rayner Stephens, who might be

compared with Kossuth for his mastery of tongues, was silent. Since

Kossuth's day only one orator has with the same suddenness engaged public

imagination—Joseph Cowen. But Kossuth's distinction was the greater

because he spoke in a tongue foreign to him. And what was not less

striking, his reputation was as much owing to what he said as to his

manner of saying it. In his speech on Poland he said: "In the public

life of nations, never is anything accidental. There everything is

cause and effect. An act of political morality can never be

neglected with impunity. Every such neglect is fraught with the

necessity of atoning it with sacrifices, increasing step by step, which,

however, never will remedy the evil, unless the wrong occasioned by that

neglect be redressed. In politics a fault is equivalent to a crime,

and no false political step can ever escape punishment."

In speaking in the House of Legislation, Ohio, Kossuth said:

"The spirit of our age is democratic. All for the people and all by

the people. Nothing about the people without the people. That

is Democracy." The conception of the popular aspiration and the

idiomatic expression of it are alike remarkable. He instructed as

well as declaimed. In Kossuth's speeches you found definition as in

Paine or John Stuart Mill, which is rare in popular orators and writers.

I published Kossuth's oration on the "Independence of

Poland," delivered in Sheffield, June, 1854; but his speeches on the "War

in the East" and "The Alliance with Austria," delivered in Sheffield and

Nottingham the same year, were "published by himself." They were

printed by Tucker, Perry Place, Oxford Street, and sold by him. As

Kossuth had no place of business, he could not "publish by himself."

Probably, by saying so, he merely meant to indicate that they appeared by

his authority. Louis Blanc was long resident in this country.

He Spent twenty years of exile among us, and understood men and things in

England, our politics and prejudices, and more faithfully interpreted them

to the French people than any other exile who ever dwelt in England save

Mazzini. Mr. G. W. Smalley, an American, not an exile, has excelled

in the same art. Kossuth, on the other hand, sometimes entertained

suspicions which fuller information would have made impossible. An

attempt to serve him would seem to him, as it did to Weitling, something

very different. Foreigners as a rule are liable to suspicion, but

Kossuth was so distinguished for cosmopolitan attainments that anything

ordinary became noticeable in him.

|

|

|

Louis Blanc

(1811-82) |

In another respect, not of contrast, but of similarity,

Kossuth may be compared with Louis Blanc. Kossuth was regarded as a

man of flexible principles, yet, like Blanc, he proved to have

inflexibility to a degree unforeseen. Kossuth lacked the penetration

of Mazzini, and put such trust in Louis Napoleon as to enter into

negotiation with him when he was Emperor; yet he preferred to live an

exile rather than acknowledge an order of things in his own country he

disapproved.

Louis Blanc was distrusted because the policy of French

Republicanism which he espoused was deemed materialistic. I

published the manifesto of Kossuth, Ledru Rollin, and Mazzini, and also

Louis Blanc's "Reply" thereto. Yet Louis Blanc possessed an

inflexibility on questions of principle as austere as Mazzini himself.

He was many times besought to return to Paris, and offers of a

Parliamentary seat were made, to which he answered—

"Duty could only call me to Paris to take part in Parliamentary struggles,

if the electors should assign me a post. But this post no power on

earth can make me occupy, so long as I must needs, in order to do so, take

an oath which is not in my heart.

"Do the people really wish to be the sovereign? Let

them elect those who refuse to take the oath; let them elect them, not in

spite of, but because of their refusal."

These sentiments are all the more remarkable since few public men in

England have expressed them or acted upon them.

This resolution was as noble as the warning was wise, and

Louis Blanc remained an exile until Sedan swept the false Emperor away.

His exile lasted twenty years. I knew him from the beginning to the

end, during his residence in London and Brighton. It was said of

him, and of his distinguished but more demonstrative brother Charles, that

Charles was a reed painted like iron, while Louis was iron painted like a

reed. This was true. Beneath Louis Blanc's passionless

cordiality lay impassable determination, which neither profit, nor

applause, nor obscurity, nor neglect could divert from honest principle.

Though a small man, smaller than the First Napoleon, he had none of the

self-assertion by which little people often seek to conceal their

diminutiveness. Louis Blanc was a self-possessed man, and, alike

when he conversed or spoke on the platform, you never thought of his

stature under the boldness of his tones and his commanding gesture.

He ranked among the great political historians of France.

Like M. Thiers, he made history a stepping-stone to power. The

"History of the Consulate and the Empire" led to Thiers becoming a

statesman; and the "History of Ten Years" mainly inspired the Revolution

of 1848, and made Louis Blanc a member of the Provisional Government.

Unlike Ledru Rollin, whom he resembled in a noble irreconcilability, Louis

Blanc had literary genius and capacity for statesmanship, which consists

in understanding what measures are best conducive to the greatest

happiness of the greatest number, and acting with large toleration.

Blanc continued to maintain his influence as a commanding force in French

politics until his death. It seemed as though all Paris followed him

to the tomb. Since the burial of Thiers so great a concourse had not

marched to a tomb until Hugo died. I was proud to be one of his

English friends invited by Louis Blanc's family to follow him to his

grave.

Ledru Rollin was another exile of note who had a singular

career. When he did return to France, another generation had grown

up, to whom he was unknown. Exile is a fatal power in the hands of

tyranny: since it not only kills influence, it kills reputation.

Louis Blanc having literary powers, his pen kept his name before his

countrymen. Rollin's power was in the courts, on the platform, and

in the Senate. Exile destroyed it. Mazzini said of him that he

was the only Frenchman who gave up a public position and sacrificed

himself for the welfare of a country not France, and for a cause not

French. He incurred exile by his generous championship of the cause

of Italy. He was what he appeared in Madame Venturi's painting of

him—of manly bearing, of conscious power, yet withal unobtrusive in

manner. That Barthelemy—a duellist whom some regarded as a murderer,

and who was eventually hanged at Newgate for an undoubted murder—was

hostile to the famous tribune is proof that he was less extreme than he

was taken to be. Some politicians speak better than they act: Rollin

acted more wisely than he spoke. The Royalist press of England

decried him because of the title of a book he published some time after

his arrival in England—"The Decadence of England." That work

contained nothing but what we knew—nothing but what we had said ourselves.

Had the great Republican lawyer entitled his volume, "Extracts from the

Morning Chronicle," or "England drawn by Horace Mayhew," or the "Fall of

the English Foretold by Themselves," any one of these titles would have

expressed the character of the work. But because the author employed

another title, the public were incited to take offence at the book.

Six out of every seven titles of books have no relation to their contents.

|

|

|

Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin

(1807-74) |

The sagacious French jurist, no doubt, saw signs of decadence

in England, in aristocratic incumbrance. With the millstone of noble

incompetence hanging round the neck of the nation, he might well think

Britain was going to sink "ten thousand fathoms deep." What Ledru

Rollin could not see was that England has the power of renewing its youth.

The Sindbad of Britain will not carry the Old Man of Privilege on its back

for ever. Soaring, it will drop the aristocratic tortoise on some

well-chosen rock, and smash it. Rollin thought he saw the old

English lion stuffed with cotton. The noble brute who, in the days

of Cromwell, could roar until he made the isles resound and Europe

reverberate, seemed turned into a puff-bellied, flaxen-hearted old beast,

whose lungs were a pair of steam-boilers, his breath condensed vapour, his

molars spinning jennies, and his royal old tail a horizontal factory