|

Before the Society Began.

――♦――

CHAPTER I.

THE Leeds Flour

Society, like Rome, did not grow in a day, but soon after it began

it grew faster than Rome did—because its founders understood that

what honesty is to business so principle is to progress.

Others in Leeds may have believed as much, but none acted upon the

belief that without honesty in business there can be no permanent

trade, and without adherence to principle there can be no public

confidence. By this discernment the co-operators have won

profit and respect.

The reader will naturally expect to learn how this Society

arose and what preceded it, for every intelligent person knows now

that progress does not come by chance, but is a matter of evolution

from something which went before. The previous is the

foundation of the present.

For several years before the commencement of the Leeds

Society, the condition of the people had the three characteristics

of the time—scarcity of employment, low wages, long hours of labour.

The "Condition of Leeds Question," as Carlyle would have called it,

was the subject of public meetings. At the commencement of

1843 pauper relief had increased from 30 per cent to 60 per cent.

During the year the "Benevolent and Strangers' Friend Society" had

considerably over 2,000 applications for relief. The Public

Soup Kitchen, supported by voluntary contributions, was opened

several days a week, with few intermissions, from 1843 to 1847.

An excellent soup, as Mr. William Campbell learned from the report

of his neighbours, was sold at 1d. per quart, tickets being issued

often gratuitously to the extent, frequently, from 10,000 to 15,000

a week. In one district a committee was formed to ascertain,

by house to house visitation, the extent of destitution existing,

and found that nearly a thousand families were in the receipt of not

more than 10¾d per head per week.

In another populous district 12½

per cent of the population were receiving parish relief.

The necessity for gratuitous sustenance was so great that the

supply of soup had to be increased to 19,200 quarts, at a cost of

£200 a week. A petition was sent to Parliament for protection

against the powerloom, which displaced workmen and increased the

unemployment by thousands. Parliament did not see its way to

do anything, and did not want to see it. The greatest

objection to Free Trade has been its want of consideration to

workmen temporally ruined by it, which has set workmen in every

nation against Free Trade. Those who made fortunes by the

powerloom should have been assessed, so far as was necessary, to

succour those who were displaced, until new employment was found for

them. Invention, which was hated, resented, and opposed unto

death in many places, would then have been popular, and the use of

inventions would have been honourably accelerated.

The Leeds Flour Society did not spring up out of nothing.

Co-operation was in the air, but it was not bred there—it was put

there. Several Leeds men of capacity and influence had been

interested in the "New Views of Society," promulgated by Robert

Owen. When Queenwood had

failed, they were disconcerted—but not discouraged—and some of them

met in the Unitarian Meeting House on Sunday afternoons, and

endeavoured to found another industrial city, which should show the

working class the way of self extrication. It took the

aspiring title of the "Redemption" Society. The movement

commenced in 1845. Mr. William Howitt afterwards described it,

in his Journal, as a "Co-operative League," but the committee

unfortunately adopted the more ambitious and pretentious name of the

"Redemption Society." The Leader newspaper published

subscriptions received by the Society. The lists came to me.

We all approved of the object in view, but when we had to announce

subscriptions of 1s. 2d. in Leeds, 10d. from Edinburgh, and 4d. from

Glasgow, readers felt that, with contributions so slender, the

redemption of the world was a long way off. But in the earlier

days of the Society the support was greater. During 1846 the

promoters took the field, or rather the streets, by making house to

house visitations, obtaining members and penny per week

subscriptions. Working people had very little to give in those

days. A Mr. G. Williams gave the Society, conditionally, an

estate in Wales on which to try their experiment. Three

persons went from Leeds—E. C. Denton, a joiner, who died only a few

weeks ago; J. W. Gardiner, a shoemaker, still living in Leeds; and a

youth named Hobson. The first annual Redemption meeting was

held in the Music Hall, Leeds (January 7th, 1847), when William

Howitt took the chair, and made an excellent speech on co-operation.

The speakers were the Rev. Edmund R. Larken (a large proprietor of

the Leader), Dr. F. R. Lees, Joseph Barker, Joshua Hobson,

James Hole, and the chief inspirer of the movement—David Green.

About 200 persons, interested in the social enterprise, took tea

together. Lord Ashley, Douglas Jerrold, Joseph Sturge, Henry

Vincent, Rev. Thomas Spencer (uncle of Herbert Spencer), wrote

letters to the meeting; and Joseph Mazzini, who sent a subscription

with his letter, asked to be enrolled as a member. Hence the

reader will see the Society had distinguished well-wishers. It

was stated there were 600 members belonging to it. The

subscriptions for the year exceeded £181, while the expenses had

been only £17.

The method of this Society shows the reader how co-operation

was the original device of these social reformers. The

Redemption Society did a little distributive trade in groceries and

provisions. It had a shop, and its commodities were sold at

its place of meeting, which was an upper room in Trinity Street,

over a stable. It was open in the evenings only, when a member

of the committee attended. The principal article sent from the

Society's estate in Wales was blackberry jam. Blackberries

being plentiful about the place, labourers' children gathered them

and sold them to the little Colony for a shilling a basket, and so

jam came to the Redemption Society in Trinity Street, Leeds.

Thus Robert Owen's scheme of Industrial Cities (then called

communities) were in the minds of the thinking artisans of Leeds.

Lloyd Jones, one of my colleagues of the Social Missionary group,

had often visited Leeds, and about 1847 was living there.

Public discussions had been held there. The Northern Star

had been published in Leeds. Many men of ability in the town

knew all about co-operation.

Several volumes of the New Moral World were printed

and published by Joshua Hobson, at 5, Market Street, Leeds. In

the New Moral World for 1839, no fewer than eighteen notices

are accorded to Leeds. Robert Owen, G. A. Fleming, Lloyd

Jones, Dr. Frederic Hollick (still living in New York), Robert

Buchanan, James Rigby, and all the lights of the "Socialism" of that

day—not dreamy but definite—not revolutionary but constructive—had

spoken in Leeds. A hall was held by these advocates, and

lectures delivered weekly, and famous discussions were held at

times. Richard Carlile and Lloyd Jones met in Leeds.

From 1838 to 1841, Leeds was an emporium of social ideas.

The principal apostles of the Redemption Society were David

Green, Lloyd Jones, Dr. Lees, James Hole, John Holmes, William

Campbell, William Bell, John Hunt, and E. Gaunt. Mr. Campbell,

whose recollections I follow, is not aware that there was any single

member of the Redemption Society among the early originators of the

Flour Society, and only three names—Green, Holmes, and Hole—can be

rightly counted among the fifty-eight precursors elsewhere

enumerated. The two movements were essentially distinct and

promoted by different persons. Nevertheless, when the

Redemption movement was found impracticable with the means

available, its leaders, acting on Goethe's great maxim, "Do the duty

nearest hand," carried their enthusiasm and larger knowledge into

the ranks of the Flour Society when it was appealing for public

support, and needing it. The names of those who thus assisted

will be found frequently occurring in the ensuing narrative.

Some of them became directors, some of them presidents. Lloyd

Jones and John Holmes, two of the most influential directors of the

Flour Society, lost their seats through advocating forward steps,

such as the addition of the grocery and provision business to the

Flour Society. They constituted the elements of progress in

the Flour Association, and supplied, at their own peril, the

inspiration which carried it forward into the region of larger

co-operation, which has led to its great distinction and success.

James Hole delivered a series of lectures on "Social Science and the

Organisation of Labour," which the Rev. Dr. Hook said was the best

book he had ever read upon the subject. Thus, when the Bonyon

Mill men, of whom the reader will soon learn more, came into the

field, there was already, as has been shown, a body of ready-made

opinion in sympathy with their project and ready to advance it.

It may be said that the Redemption Society was the precursor of

co-operation in Leeds.

Origin of the Society.

[1847.]

――♦――

CHAPTER II.

FLOUR was the

beginning of the famous Society which is the immediate subject of

these pages. There is a tradition of Pitt that he once began

one of his sonorous speeches in the House of Commons with the word

"Sugar." Sugar is so familiar a term that it seemed trivial,

and the triviality of the term concealed its importance. The

great orator paused at the word "sugar," and the House laughed,

thinking perhaps that he meant to sugar them, upon which Pitt

repeated the word with indignant emphasis, at which they laughed

again. The third time he connected the word with its context

in his mind, and Parliament were all attentive and laughed no more.

Let us hasten, therefore, to say that the common-place

term—Flour—had to the working people of Leeds, in 1846-47, the

infinite interest of a necessity of life, which was scarce, dear,

and bad. Yet in 1846 such flour as was to be had was 4s. per

stone of 14 lbs. A stone of flour is sold now in Leeds from

1s. 6d. to 1s. 7d., which denotes a better condition of subsistence

for the working class.

There was also great depression in trade then. The

outlook was as dreary as that of Noah from the Ark before the waters

subsided. The state of the working class was as monotonous as

despair. As Charles Matthews, the elder, once said, there was

"nothing stirring but stagnation." Yes, there was something

unobserved stirring—it was adulteration. Dr. Adam Clarke, in a

long-remembered phrase, said, "Leeds was the Garden of the Lord."

But, alas, in those days no trading conscience grew among the plants

of that garden, and millers sold flour which would give a boa

constrictor indigestion and reduce him to ribs and skin.

Before the days of co-operative stores the poor man's stomach was

the waste-paper basket of the State, into which everything was

thrown which the well-to-do classes could not or would not eat.

The state of things described demanded action, and men of action

were found, but not where they were expected, nor were they the kind

of men anybody looked to as likely to originate a great change.

The insurgents were the Benyon Mill men, who issued forth with the

following singular address, headed—

HOLBECK ANTI-CORN

MILL ASSOCIATION.

To the Working Classes of Leeds and its vicinity.

We, the workpeople of Messrs. Benyon and Co.'s mill, Holbeck,

in the county of York, having experienced much trouble and sorrow of

late in ourselves and families, in consequence of the exorbitant

price of flour, do judge it needful for us to take every precaution

to preserve ourselves from the invasions of covetous and merciless

men in future. In consequence thereof we deem it needful to

enter into a combination to raise a subscription to the amount of

twenty shillings, to be paid by each member in weekly instalments,

to be determined on at a meeting to be held in a room behind the

Union Tavern, on Monday, March 1st, 1847, at seven O'clock in the

evening, for the purpose of renting a mill until the funds of the

Society shall enable them to erect a mill of their own, which shall

be the property of the subscribers, their heirs, executors,

administrators, or assigns, for ever, in order to supply them with

flour, and that only.

N.B.—The committee are wishful to raise 1,000 members for the

purpose of carrying out this noble enterprise. They therefore

call upon the working classes to attend the meeting, in order to

look to their own welfare and the welfare of their families.

ROBERT

WILSON AMBLER,

JOHN PARK,

JOSEPH DARLEY,

ROBERT AMBLER,

JAMES JACKSON,

WILLIAM WARD,

JOSEPH NOWELL, |

THE COMMITTEE.

February 25th, 1847.

The Benyon Mill men, as they appeared in their day, are worth

preserving in portraits where such exist. The first who signed

the circular address was Robert Wilson Ambler, who had an oval head

of the Sir Joshua Reynolds type. His face is expressive of

shrewdness and alertness. He was just the man to make a

"stirring speech," which he did to the hundred who met at the Union

Tavern.

|

|

|

Robert Wilson Ambler |

It will strike the reader of to-day as odd that the insurgent

flax spinners should seek to set up an "Anti-Corn Mill Association,"

which suggests that they were against a corn mill, when all the

while they were trying to set up a corn mill. Mr. Fawcett

conjectures that the term "Anti Mill" was used to designate

opposition to the private millers of the day,[1]

who, as the Benyon men say, brought "much sorrow and trouble to them

and their families." These workmen, taking to public affairs

and inviting the co-operation of the town, were confident

innovators, as will be thought to-day, to proclaim the name of their

employers as though they were cognizant, or concurring in the step

taken by their men. The Bensons were of the Tory persuasion,

but of the tolerant type. In many towns a step of the kind in

question led, in early days of the the social movement, to dismissal

of men. It was, however, a pleasant custom in Leeds for

workmen to describe themselves by the name of their employers, as "Kitson's

men," or as "Fairbairn's men" do now.

|

|

John Park. |

The portrait of John Park (page 9), the second who signed the

circular, is that of a solid man of vigour with an impassable look,

and features wonderfully resembling the Rev. John Angell James, my

pastor for five years in Carr's Lane Chapel, Birmingham.

Before reading the name I thought it was Mr. James. There is

no "sorrow or trouble" in Park's face.

The readers will see that these adventurous flax spinners

constituted themselves as an "association" before they were

associated. They announced themselves as "We, the work-people

of Messrs. Benyon and Co., Meadow Lane, Holbeck, in the county of

York." There was no mistake as to who they were, and where

they were, and any person wanting to communicate with them need not

go running all over England. They were to be found in

"Holbeck, in the county of York." It would appear that they

regarded Holbeck as a more important, or better known, place than

Leeds. They announced their intention to take precaution,

"every precaution," they said, which was quite beyond their power,

to preserve themselves "from the invasions of covetous and merciless

traders," and from the "exorbitant price of flour." They

therefore determined "to enter into a combination to raise a

subscription of twenty shillings from each member, to be paid in

weekly instalments as might be determined upon, at a meeting to be

held in a room behind the Union Tavern, on Monday, March 1st, 1847,

at seven o'clock in the evening." The business of the meeting

was stated to be the "renting of a mill until the funds of the

institution enabled them to build one." They already regarded

the "combination," not yet combined, as an "Institution." If

poor in means they were affluent in terms. Then followed an

outburst of legal language, declaring that the mill of their own

should be the property of the subscribers, their heirs, executors,

administrators, or assigns."

The working class of Leeds fifty years ago had hardly thought

of "heirs," as they were not sure of having anything to leave them

except the poorhouse. Of "executors and administrators" they

had very scant knowledge, and of "assigns" few of them had the

slightest idea. They did not even foresee or know that they

would have bran and straw to sell, and bound themselves "to supply

flour to their members, and that only." The law made one

limit, and they made a larger one upon which battles were fought.

The "Union Tavern," the place of meeting, did not require any street

being given as to where it was situated, nor did it need to be

specified as being in the "County of York." Everybody in

"Leeds and its vicinity" were assumed to know where the "Union

Tavern" was.

Joseph Nowell (page 11), the last name on the Kenyon circular

calling the first meeting, has an honest, hard-working look, as

though he had shared the "trouble and sorrow brought into

working-men's families," by dear and pernicious flour.

On the 1st of March about 100 persons attended the meeting,

which comprised persons from all parts of the town and

neighbourhood. Mr. William Eggleston was chairman. Mr.

R. W. Ambler and others made "stirring remarks" upon the price and

the extent of the adulteration of flour. It was resolved to

call a public meeting, to be held in the Tabernacle Schoolroom,

Meadow Lane, on the 7th of March, 1847, and bills were posted giving

the town notice to that effect. At this meeting about 1,000

persons were present in the room, and many more were refused

admission "because the place was full," which shows that social

innovation of some kind was well about. The objects of the

meeting were fully explained.

The meeting understood their business, which was to provide

funds for incidental expenses in forming the Society, and they

agreed to subscribe a shilling each. It was arranged that if

the project succeeded the shilling should be counted into the shares

taken. Thus the originators of the great Society began upon

the principle of a ready-money movement.

The meeting ended by appointing a committee to carry forward

its purposes.

The first Committee of Organisation.

[1847.]

――♦――

CHAPTER III.

AT the commencement of the new movement an unreflecting reader

thinks all the merit of it belongs to the new actors who appear upon

the scene. Great merit does belong to them, because they are

the first to put into action what others have merely talked about.

Yet let it not be supposed that those who only talked, even the

least influential, did nothing. They disseminated, in the

humble circles where they moved, a wholesome discontent at the

existence of an avoidable evil. If a man does not know, or

does not see what to do to effect a needed change, his duty is to do

what he can. Any man who has no opinion on a question on which

he ought to have an opinion, is a poor creature. If he has an

opinion he can find some means of expressing it, if only to his

neighbour, and if he is not on speaking terms with his neighbour he

can express it to his wife, who usually has generous enthusiasm, and

will soon express her opinion to somebody else. The result is

that when a few intrepid men take the field they find people

everywhere who understand their object, and the bolder sort of those

thus informed join the new standard. The French regard all

present at a meeting as "assisting" at it. This is true.

Even those who make part of a crowd at the door, who cannot get in,

add to the influence of the meeting, since it indicates to all

observers interest in the question discussed inside. Milton

says, "They also serve who only stand and wait." This is so,

provided they stand in the right place, and are at hand to help when

called upon. Thus it came to pass that when the next public

meeting was called it was crowded.

A contagious or similar activity soon manifested itself

elsewhere. One meeting was held in Newtown. A deputation

was sent from the Meadow Lane Committee to a meeting held at Tulip

Inn, Newtown, to make arrangements to meet together. It was

decided to hold a public meeting in Leeds, in the Court House (now

the Post-office), [2]

which took place by the friendly courtesy of the Mayor, George

Goodman, Esq. This was the first public Corn Mill meeting held

in the town of Leeds. It took place at the end of March, or

early in April, 1847. Public interest in the question had so

increased that from 1,200 to 1,400 persons were present. The

Leeds Times, edited by Robert

Nicol, the poet, always had sympathy for the unrecognised

interest of the people, and took cognisance of the meeting, and

recommended working men to join the proposed society. Friendly

reports and descriptions of the public proceedings of the Society

have appeared in the Leeds Mercury, whose files we have had

to refer to, for facts and dates for these pages. At the first

meeting to receive subscriptions, 433 persons paid an entrance fee

of one shilling, and in two months no less than 1,023 had joined the

movement. This shows unusual enthusiasm of a practical

business kind, that so many persons of small means should subscribe

so readily that an unknown and doubtful manufacturing experiment

should be tried.

The names of the committee appointed to organise the new

movement were the following:—

|

R. PENROSE. |

JAMES ROBINSON. |

|

SAMUEL HAIGH. |

JUNO. HARDEN. |

|

S. SUMMERSCALE. |

CHAS. FITZROY. |

|

JOHN TAYLOR. |

SAMUEL WRIGHT. |

|

G. W. THOMAS. |

W. LAMB. |

|

W. EGGLESTON. |

HENRY THOMPSON. |

|

J. E. CRAVEN. |

M. JACKSON. |

|

G. WALKER. |

THOMAS ATKINSON. |

|

JOHN SMITH. |

JAMES HOLE. |

|

J. SWAINE. |

D. GREEN. |

|

JAS. SMITHSON. |

JAMES BOOTH. |

|

JUNO. WALTON. |

A. BEANLAND. |

Two of the leaders of the Redemption Society—David Green and

James Hole—were present at this meeting, and were at once

incorporated in the committee, which thus acquired the elements of

higher progress than Benyon men had in their minds. It is a

notable fact that not one of the seven flax spinners are on the new

committee appointed to carry forward their project. It appears

to have passed out of their hands, but to them belongs the credit of

originating the great working-class union, and of passing it on.

They have an historic place among the founders of the "Anti Mill"

movement.

This committee of arrangement, like the one which issued the

first address, met at Mrs. Walker's Coffee House, Duncan Street, and

devoted all the time they could command to setting a corn mill in

motion.

The Redemption men now among them, knew that a co-operative

store was simpler, easier, and more manageable. The Rochdale

store was only three years old, and not much to refer to then.

Very likely, or probably, the suggestion was not made, or not urged.

Mr. Green and Mr. Hole had been put upon the committee to aid in

carrying out the mill idea, and they did.

The local need was honest flour. There was zeal for

that. It was right to take advantage of ready-made enthusiasm

for a useful, if difficult object, rather than attempt something

else easier, but for which zeal had to be created.

People were moved by indignation in commencing with a flour

mill. Probably few understood the different kinds of knowledge

necessary for such an undertaking—knowledge of which spinners,

weavers, mechanics, and shoe makers were entirely ignorant. Or

if any understood the difficulties of the enterprise they were not

dismayed, and insisted on a corn mill.

Dr. Charles Mackay, the poet, in the days before he became a

copperhead, [3] called

upon "men of thought and men of action to clear the way." The

Leeds Pioneers were of this description, for seldom if ever has a

new movement been conducted with more celerity than marked the

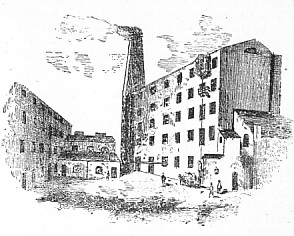

progress of the Leeds Society. By July they obtained the

certificate of their rules from the Registrar. They succeeded

in obtaining the Britannia Corn Mill, in Saville Street, Wellington

Street, which belonged to Mr. Fieldhouse, an appropriate name for a

corn miller. This mill they worked for fifteen months.

The first corn was ground in September, and the first flour

made from this corn was reserved for the tea party, held in the

Music Hall, Albion Street, October 28th, 1847. Thus, within

seven months from the first subscription being paid to the Benyon

Mill men, a corn mill was taken, corn ground, bread made and eaten

at a public tea party. Clearly the pioneers of Leeds meant

business, and their successors have meant it ever since. At

this time it was found necessary to close the books against the

admission of more members, the mill not being able to supply flour

to more persons than had already joined the Society. By the

end of December, that is, nine months after commencing their

association of millers, they had bought nearly 1,800 quarters of

wheat, at an average of fifty-nine shillings a quarter. In

addition they bought barley, beans, Indian corn, and other cereals.

A Special Committee prepared rules for the administration of the

affairs of the Society—rules so remarkable and unparalleled that

they deserve distinct consideration.

The Wonderful Rules.

[1847.]

――♦――

CHAPTER IV.

THE Duncan Street

Committee were prudent men. They drew up a code of rules, and

employed Mr. William Middleton, solicitor, to render them in

accordance with the Friendly Societies Act. They were

afterwards submitted to the Attorney-General, Sir John Jervis, for

his opinion. It is difficult to conceive why this should be

done, seeing there was Mr. Tidd Pratt, Registrar of Friendly

Societies, whose legal judgment would be exercised upon them, and

whose signature would give them authority. All the while the

committee did not trust Sir John Jervis, but appointed a "special

number of persons to watch him" lest he should pervert the spirit of

the rules, which he was very likely to do. The rules were duly

certified by John Tidd Pratt, on the 8th of July, 1847, and

surprising rules they were. One was "That no member shall

receive more flour than is necessary for his own family." Who

was to ascertain how much was "necessary"? It would employ a

committee of doctors, all their time, to determine this. Most

families eat too much meat, and take too little bread; some families

are given to vegetarianism, and take bread in excess; some families

are teetotal, and they eat more bread than beer drinkers. Mr.

Cobden found out this when he held a Peace Conference on the

continent. The second time the hotel-keepers charged a much

higher price for dinner than formerly, on the ground that most of

the delegates were temperance people, who not only drank no ale or

wine, which mainly made the profit, but ate much more in

consequence, which increased the loss. An inquisition would be

necessary into the habits of every family under the rule cited.

It is one of many examples that no persons ever think of inflicting

such restrictions upon working men as they inflict upon themselves,

before the day of education comes.

Another marvellous rule was as follows:—"Any member who shall

sell or make goods for sale, of the flour or meal received from this

Society, shall, on conviction of either of the above offences, be

fined ten shillings for the first time, and be excluded on a

repetition thereof." No act to regulate the sale and use of

poisons has more stringent conditions than this rule for the sale

and use of flour.

The object of the Society was to make flour, and the

prosperity of the business depended upon the amount it could sell.

Here was a rule expressly framed to prevent it doing business, and

if any poor member had a clever, intelligent wife who knew how to

cook and increase the resources of her family by making digestible

tarts or pork pies—very scarce in Leeds in those days, and scarce in

other towns still, of a digestible kind—it was an offence under the

rules of these working men to be punished by fine and expulsion.

The framers of these rules had a very narrow outlook, and the

Attorney-General could not have done worse for them than they did

for themselves.

A further rule had democratic sense in it, and is entitled to

respect. It sets forth—"That any member refusing to fill the

office of president, vice-president, secretary, treasurer, director,

or auditor, or resigning such office without sufficient cause, shall

be fined two shillings and sixpence."

This rule recognised the equality of the right and the duty

of every member of the Society to take part in its administration,

and necessitates education as part of its policy, as without it,

members cannot be qualified to fill the offices to which they may be

called. Being ignorant, they would retard or ruin it.

The members of the new Society had no idea the day would come

when it would be a point of distinction to be elected to serve it.

Mr. Hole and Mr. Green had been conversant with rule-making for many

societies in previous years, but in this case their judgment must

have been overruled, and it must have been in deference to the

opinion of the great majority that they concurred in sending these

singular rules to the Registrar. It was under these rules that

the first directors were appointed.

The First Directors.

[1847.]

――♦――

CHAPTER V.

THEY who begin a

movement make it, and on this principle the first directors are

entitled to a place in this history.

The main rule for the government of the Society and election

of officers was as follows:—"That this Society shall be managed by a

president, vice-president, secretary, treasurer, and twenty

directors, who shall be elected in the following manner, viz.: Six

members shall be nominated by the directors, from whom the president

shall be chosen. Six others in like manner, from whom to

choose a vice-president. After the first election the

vice-president shall at all times succeed the president. The

directors shall also nominate six additional members, from whom

three shall be chosen; one of the latter to go out of office every

succeeding six months, when three others shall be nominated as

above, and one selected by (in every case) the members present at

the half-yearly meeting. Twenty members shall also be chosen

as directors, ten of whom shall retire half-yearly, and ten others

elected in their stead." The rule has only historic interest

now as showing the early device for electing directors.

Organisation was soon afloat, and the following persons, in

various capacities, were elected the first board of management [4]:

Trustees―

|

THOMAS NUNNERY,

ESQ., Surgeon, Leeds.

MATTHEW HALL,

ESQ., Surgeon, Wortley.

Councillor GEORGE ROBSON,

Leeds.

Councillor WILLIAM BROOK,

Leeds. |

Directors, &c.—

Mr. JOHN SMITH,

President.

JOHN TAYLOR,

Vice-President.

RICHARD PENROSE,

Treasurer. |

|

Mr. JOHN WALTER. |

Mr. WILLIAM WRAY. |

|

SAM. SUMMERSCALE. |

JAMES WALKER. |

|

GEORGE WALKER. |

JOSEPH WORSNOP. |

|

JOHN HEBDEN. |

JOHN CAVE. |

|

JAMES ROBINSON. |

MATTHEW FAWCETT. |

|

JOHN OXLEY. |

GEORGE DENHAM. |

|

JOSEPH MATHERS.

|

WILLIAM SWALLOW. |

|

JOSEPH LAWSON. |

SAMUEL HAY. |

|

SQUIRE FARRAR. |

JAMES ALLAN. |

|

RICHARD HOLES. |

BENJAMIN WARD. |

Secretary—WILLIAM EMERSON.

Arbitrators—

|

DARNTON LUPTON,

ESQ., Leeds.

JOSEPH CLIFF,

ESQ., Wortley.

JOSEPH OGDEN

MARCH, ESQ.,

Woodhouse Lane.

JOHN WALES SMITH,

ESQ., York Place.

THOMAS FOSTER

AGAR, ESQ.,

West Street |

Auditors—

Mr. ZEBEDEE SWAIN,

Leeds.

» THOMAS

ATKINSON, Leeds.

» WILLIAM

BIRKHEAD, Kirkstall. |

The rules were only certified on the 8th of July, and on the

31st the first meeting of directors took place, when they advertised

for a corn mill, a step not without peril, for they gave the millers

public notice to be on their guard, as an enemy was in the field.

In London even, when we required to build a hall about the same

time, we found that not a squares inch of ground on which to plant a

walking-stick could be bought. No one would sell or let, when

our purpose was known, which had been imprudently published.

Yet our purpose was to establish an institution for what is now

known as social and co-operative advocacy. Of course, the

millers of Leeds took the alarm, and every obstacle their ingenuity

or their interest could put in the way of the directors, they set in

motion. Nevertheless, as we have seen, the directors overcame

every obstacle. They obtained a mill and ground corn in it.

The Society, at first, was co-operative only in a very

elementary sense. It was a cheap selling store. It had

no arrangement for making profit, and of course had no idea of

distributing it—whereas distribution of profit has been the strong

incentive of growth in co-operative societies. The first

flour-mill rule bound the directors "to sell as near prime cost as

possible," which left no margin for profit. They were directed

in the first rule "to buy corn as good as possible." But Rule

12 said that "there shall be such sorts of flour made at the

Society's mill as the majority of the members shall decide."

"Such sorts" included seconds. The terms would allow cheap

kinds—or adulterating kinds, if the majority of the members should

so decide. It is to the credit of the directors that they

never attempted nor permitted any evasion of the pledge of purity.

It is also to the credit of the members that they never proposed any

departure from their profession of good faith towards the public.

The reader will see how many were the contests subsequent

directors engaged in, to keep the Society true to purity in flour.

As persons joined the Society knowing nothing and caring less for

principle, but impetuous for cheapness at any cost of truth in

trade, the directors were ever in battle array for the honour of the

Society. Those who would lower the Society to the level of an

ordinary shop, would have succeeded had it not been for the

honourable steadfastness of the directors from time to time.

Some directors, it will be found who strenuously urged a certain

course should be taken for the progress of the Society, were

dismissed for doing it; but the members obtained enlightenment by

it, and pursued the very course they had dismissed their directors

for recommending to them.

A foremost advocate of social justice in our time, Mr.

Ruskin, has expressed a policy which may be taken as describing that

which the directors have pursued more or less to this day: "The

simplest and clearest definition of economy, whether public or

private, means the wise management of labour, and it means this

mainly in three senses—first, in applying your labour

rationally; secondly, in preserving its produce carefully;

lastly, distributing its produce seasonably."

Mr. Ruskin's scheme of economical policy is for the State, in

which profits are neither made nor needed, as where all produce is

"seasonably distributed" all life is profit. Since we are not

in that Utopia yet, men have to unite in societies to control and

share the profit made by purchase or by labour. In these

directions the voices of the directors have oft been heard.

How this has been done will be seen very clearly in the Chronicles

of the Society from year to year. Great difficulties have been

encountered, great exercise of patience has been exacted, but the

march of the Society has ever been onward. The motto of the

Leeds Society, like that of the City of Birmingham, always has been,

and is, "Forward."

It has been held as remarkable that many of the most eminent

Jewish doctors were humble tradesmen, and it is not less notable in

its way that the men who have proved successful directors of the

Society, came from the ordinary industrial ranks in the town.

Notwithstanding, as high a quality of prevision, organisation,

administration and judgment, has been manifested by them as any

directorships have ever shown.

The Fifty-Fight pioneers of Leeds.

[1847.]

――♦――

CHAPTER VI.

THE following are

the names of the Fifty-eight Pioneers of Leeds, all of whom held

office, or performed some duty of importance in the interest of the

Society, in the year 1847:—

|

3 ALLAN, JAMES. |

3 HAY, SAMUEL. |

|

1 AMBLER, ROBERT

WILSON. |

2 HARDEN, JOHN

(R). |

|

1 AMBLER, ROBERT. |

2 HOLE, JAMES. |

|

2 ATKINSON, THOMAS. |

2 HOLMES, RICHARD. |

|

2 BEANLAND, A. |

1 JACKSON, JAMES. |

|

3 BIGHEAD, WILLIAM. |

2 JACKSON, M. |

|

2 BOOTH, JAMES. |

KITCHEN, WILLIAM

(MR). |

|

3 CAVE, JUNO. |

2 LAMB, W. |

|

3 CLIFF, ESQ.,

JOSEPH. |

3 LAWSON, JOSH. |

|

2 CRAVEN, J. E. |

3 LUPTON, ESQ.,

D. |

|

1 DARLEY, JOSEPH. |

3 MARCH, ESQ.,

J. O. |

|

3 DENHAM, G. |

3 MATHERS, JOSEPH. |

|

2 EGGLESTON, W. |

1 NOWELL, JOSEPH. |

|

3 EMMERSON, WILLIAM

(R). |

3 OXLEY, JOHN

(R). |

|

3 FARRAR, SIR. |

1 PARK, JOHN. |

|

3 FAWCETT, M. |

3 PENROSE, RICHARD

(MR). |

|

2 FITZROY, CHARLES. |

2 ROBINSON, JAMES

(R). |

|

2 GREEN, DAVID. |

3 ROBINSON, JOHN. |

|

2 HAIGH, SAMUEL. |

3 SAGAR, ESQ.,

E. T. F. |

|

2 SMITH, JOHN

(R). |

2 WALKER, G. (R). |

|

3 SMITH, J. W. |

3 WALKER, JOHN. |

|

SMITHSON, JOHN

(R). |

3 WALKER, JAMES. |

|

2 SMITHSON, JAMES. |

WALTER, JOHN

(R). |

|

2 SUMMERSCALE, SAM.

(MR). |

2 WALTOR, JOHN. |

|

3 SWAINS, ZEBEDEE

(R). |

1 WARD, WILLIAM. |

|

3 SWALLOW, WILLIAM. |

3 WARD, B. |

|

2 TAYLOR, JOHN

(MR). |

3 WORSNOP, JOS. |

|

2 THOMAS, G. W. |

3 WRAY, W. |

|

2 THOMPSON, HENRY. |

2 WRIGHT, SAMUEL. |

The foregoing persons were members of the first two

committees and first board of directors, who originated and

organised the Great Leeds Society. It was not until

thirty-three years after its commencement that the names of these

founders were collected together. Fifty years have elapsed

before they were classified and characterised as they are in these

pages. When the Rochdale Society began, the town had only a

population of 27,000. Leeds, when its co-operative society

began, had a population of 164,000, six times larger than Rochdale,

and its pioneers are double those of Rochdale, plus two.

Rochdale had 28, Leeds 58. The seven names marked (1) were the

seven Benyon Mill men who issued the first manifesto. The 25

names marked (2) were members of the second committee. The 21

names marked (3) were members of the first board of directors.

Those names in the list having the letter (R) after their name in

parenthesis, also were members of the "Provisional Committee,"

responsible for the rules, and whose names are published in the

Rules of 1847, which were invented and drawn in that year.

They were printed and published by Samuel Moxon, Queen's Court,

Briggate, July, 1847. [5]

The names to which are attached the letters (MR) were the four flour

members who signed the enrolled copy of the rules. The name of

J. Parker occurs only in the minutes of March, 1847, as appointed to

make a bargain with the owners of the mill.

Most of the names occur again and again, in after years, as

presidents, secretaries, directors, and active members of the

Society. Robert Ambler, one of the Benyon men, is among them,

as will be seen as this narrative proceeds. David Green, whose

name the reader has seen, was a well-known disciple of Robert Owen,

and, as we have said, founder of the Redemption Society, which had

subscribers in most parts of Great Britain. It was the last

attempt to advocate and establish an industrial self-supporting

community on principles of equity, after the manner of Robert Owen.

James Hole won distinction in letters. He was the first

translator of Strass Leben Jesu, and afterwards secretary of the

Chambers of Commerce. His last work was "Railways and the

State," a volume of remarkable fiscal research and ability.

His name will occur again in this story.

Sq. Farrar is the same name, though another person, as Squire

Farrar, of Bradford, who was always in the front of every liberal

movement until his death at the age of 93. Sq. Farrar is a

name of good omen.

Historical Chronicle year by year.

――♦――

CHAPTER VII.

1847.

A NOVEL PLAN OF DISTRIBUTION―CO-OPERATORS

IN A MINORITY.

THIS was the

Founders' year, to which five chapters have been already devoted.

The date is repeated here to complete the consecutive account of

fifty years. Ten years before this date the writer had been

about the country speaking and counselling co-operative efforts in

one form or another—some for the establishment of self-supporting

communities, some for store trading—and was therefore familiar with

the agitation current in Leeds in those days. It was a year

before the revolutionary year of 1848 that the Leeds flour movement

began. Looking back to that time now, it seems strange that

Leeds working men deferred so long to take their own affairs into

their own hands, and still more strange that they should come to

excel all other co-operative societies in extent.

The plan of distribution of the flour made was different from

any other corn mill. It was to appoint shopkeepers to be their

flour sellers. Numerous applications for agencies were

received, and the selection was made with regard to distances from

each other so that they might not overlap, and each agent have a

fair field for increasing his sales. The agents had to pay all

money, taken for flour, into the bank. By the end of 1847 the

agents had paid in, to the Society's account, no less a sum than

£4,986. The total payments made by the Society to the end of

1847 were £6,086, leaving a balance in the bank in favour of the

Society of £937, minus one penny. This was not a bad turnover

for working men to make in the first seven months in their attempt

to manage a new business, with the object of improving their

condition. In addition, they had the important advantage of

having wholesome flour, free from plaster of Paris, [6]

a favourite adulteration with some flour dealers, as the reader will

learn.

The conditions to which the flour agents had to conform will

be found in the transactions of 1858, when unforeseen troubles

brought them into discussion.

Originally, the Flour Mill Society was a mere commercial

association, with a majority of members who knew little of

co-operation, or of the amity and social toleration it teaches and

implies. It always takes time to acquire co-operative ideas.

These ideas had to be learned, and the learners were not all at once

easy to deal with. From the first year until now, how vast a

change in spirit, in character, and business outlook! The

reader will see this as the story proceeds year by year. The

evolution of principle and organisation is, to many, interesting and

instructive reading.

1848.

――♦――

TRENCHANT RESOLUTIONS—A FORTY WEEKS' LEVY—NO POWER TO

BUY LAND—A TIMELY DISCOVERY— DEADLY ADULTERATION—DR. CHORLEY'S

COURAGE—THE PERIL OF CHEAP SELLING—CO-OPERATIVE STORES A PUBLIC

NECESSITY.

THIS year opened

with enterprise. In February two important resolutions were

passed. First, that a corn mill be either built or bought as

soon as possible. Second, that a levy of £1 be made upon each

member to raise funds to either build or purchase a corn mill and

fit it up for immediate use. This levy was to be paid in eight

monthly instalments of 2s. 6d.

This denoted practical enthusiasm. The members resolved

not only to have opinions about their own affairs, but to sustain

them by substantial subscriptions. For £1 must have seemed a

large sum to many of them, and eventually proved to be too much.

It amounted to sixpence a week, to be kept up for forty weeks.

Whether the directors had in their minds the forty years the

Children of Israel spent in the wilderness does not appear, but the

flour mill men got through their wilderness and entered their

Promised Land.

The first report of the Mill Society from March 4th to July

28th was issued this year. In March, Mr. J. Smith, the

president, Mr. R. Penrose, treasurer, and Mr. J. Parker were

appointed to make a bargain with Mr. Blackburn, solicitor to the

firm of Fenton, Murray, and Jackson, owners of the mill.

Before it was bought counsel's opinion was prudently taken upon the

question whether the Society could hold freehold property. The

opinion was that it could only be held by trustees, there being no

law then, as there is now, enabling societies to hold property in

their corporate capacity.

From January to June the Society paid nearly £11,000 for

wheat and £518 to the new mill account, from which it may be

inferred the mill was bought. Other payments of more than

£1,000 were made, making total payments for the half year £11,930.

From July to December there was paid for wheat £10,492. To the

new mill account there was paid £960 and other payments amounting to

£763, making a total of payments of £12,216. Thus the power of

paying increased, and there was punctuality and promptitude in doing

it. Accounts were made up half-yearly, and the amount of

business summarised half-yearly.

The report bore the names of W. Birkhead, T. Murgatroyd, and

W. Eggleston, as auditors. This was the first signed report.

It was found that the profit made during the half year ending June

30th, 1848, had been £70.

The flour agents increased their payments into the bank to

£11,632. Thus the Society early learned the art of going from

success to success.

At this time an occurrence happened which gave the Society an

impetus, and proved not only its necessity but the wisdom of

starting it. There was bad flour and dear flour sold in the

town, but nobody knew it was dangerous flour.

One Dr. James Chorley had the honourable courage to call the

attention of the authorities to the pernicious nature of the flour

sold in his neighbourhood, [7] which was shown to be adulterated

with plaster of Paris to the extent of fourteen ounces in 20 stones

of flour. When the flour seller's premises were searched two casks

and two bags of plaster of Paris were found. The adulterating flour

seller bought his flour at 38s. per sack of twenty stones. The

selling price, retail, was 2s. per stone, and he sold it at 1s.

10d., realising 36s. 8d. per sack. Thus he sold his flour at less

than he paid for it pure. He made his profit by adulteration. This

discovery brought a great accession of members to the Mill Company,

as there were no other dealers whom they could trust. Thus the Leeds

co-operators learned what cheap selling meant. There was fraud in it

somewhere and somehow, unknown to the victims of the cheap-selling

tradesmen. Many co-operators are ignorant of this fact in these

days.

In those years there were no definite laws against adulteration as

there are now, no public analysts to whom suspicious commodities

might be sent to ascertain their genuineness, nor had working people

the knowledge or the means of getting up the necessary evidence for

convictions, nor were there magistrates much disposed to listen to

them if they appeared before them. Dr. Chorley, the medical

practitioner whom we have mentioned, found a large number of his

patients seriously ill who had bought flour at one or other of two

shops managed by a flour dealer and his wife. The inquiring doctor

had himself analysed the flour bought by his patients, and found it

to be most pernicious. One poor old lady was so ill for eleven days

that her life was despaired of. The knavish flour-seller was named

Vickers. Conviction took place. Mr. Edward Baines (afterwards Sir

Edward), as presiding magistrate, spoke in strong terms of the

serious offence of which they had been guilty. On three separate

charges he inflicted the penalty of £20 each, and the miller's wife

in one charge, making £80 of fines in all, which, not being paid,

the flour dealer was imprisoned for three months, and his wife for

one.

About the same time the coffee trick came to light. Not only was

coffee adulterated, but the chicory, which mainly adulterated it,

was itself adulterated, and a cheap-selling coffee dealer's shop in

North Street was entered by the police—through

"information" they had received. Treacle, bran, Venetian red, and

mustard were mixed together and baked: and this was vended as

chicory. But for lack of evidence no conviction took place.

These facts pointed to the necessity for a co-operative store, to

protect the members from fraud and danger in other commodities as

well as flour; but as yet the members were unable to see so far.

1849.

――♦――

THE DOUBLE SHARE RULE RESCINDED—THE FIRST ACCIDENT—A FRIENDLY MILLER

—BANKERS' CONFIDENCE— GOLDEN WORDS OF COUNSEL.

THE levy made upon the members of £1, in addition to the £1 share

each member was required to subscribe, proved to be beyond the means

of many of the members, who said that the forty shillings were too

much for working men to raise, even by instalments, and in October

the directors called a meeting to consider the best means of raising

more capital. A resolution was passed rescinding the one which

raised the shares from £1 to £2. The result was, that more members

entered than made up the difference of the money returned to those

who had paid more than £1, and in a few months all the money was

repaid to members who were entitled to receive any.

This year there was an accident to the main shaft

of the corn mill engine, which caused the mill to stand for some

time. This was a serious misfortune to the Society, as the

directors had great difficulty in getting corn ground elsewhere. The millers had their

opportunity and refused any aid to their new adversaries, whom they

had not forgiven for setting up an "Anti-corn mill." At last, one

more generous than the others agreed to help the Society out of its

difficulty—at the same time he charged a shilling a quarter more

than the Society could grind it for, but as it was considerably

lower than any one else would grind for the Society, his terms were

accepted and his help appreciated. Members were cheered by learning

that the profit made the first half year ending June, 1849, was

£135. Notwithstanding, in view of the need which might come for

further machinery, or possible loss, the directors took the

precaution of asking their bankers, William Williams, Brown and Co.,

Commercial Street, whether they would make them an advance should

occasion for it arise. The bankers, who had discernment as well as

friendliness, expressed confidence in the Society and offered an

advance of £1,500, but it never was required.

The fourth half-yearly meeting of what was then entitled the "Leeds

District Flour Mill Society," was held July 25th, in the Court

House, of which they had the use by the courtesy of the Mayor.

This year an Annual Report was published of four leaves duodecimo,

previous reports being on much larger paper. It was presented at the

Court House. In the report ending December, it was stated that the

Leeds Flour Society was the largest in the kingdom. Thus early it

attained a supremacy which it has never lost.

The directors who retired this year left memorable words of counsel

to their successors, which ought to be printed in words of gold, and

hung in every store in the land and in every co-operative office and

workshop. Their words were:―"At whatever cost, instruct the buyer to

buy the best of wheat [or material] the market affords, and to bear

in mind that the working classes of this district should have the

best and purest bread [or other commodities] possible to be

manufactured. The quality should be first, the

price only the second

object." [8] The words in brackets

are additions made by the writer to

show that the spirit of the injunction is universal in co-operation.

This remarkable passage shows how clear and sound

was the early co-operative spirit. The reader will do well to

look back to the names of this Board of

Directors to see who they were that spoke so wisely. Since that day

there have been too many members of co-operative stores who have

cared mainly for cheapness and profit, forgetful that honesty in

business, in quality as well as in quantity, and assured purity of

food, or assured excellence in any commodity, are the first

conditions of co-operative trade and co-operative integrity.

1850.

――♦――

CONTENTIOUSNESS CREEPING ABOUT—THE IDEAS WHICH INCITE IT.

THIS year the contentiousness, common in the commencement of

co-operation, asserted itself in Leeds. Indeed, in those years a

wandering speaker in the town thought Leeds social reformers

excelled in the capacity of disagreeing with themselves. The members

not only criticised the vicissitudes of business but criticised each

other—not for his improvement but for his confusion. More or less,

this is done everywhere among those under the influence of what we

used to call "the old world spirit;" which regarded everybody as

personally responsible for his peculiarities, which he was supposed

to have wilfully chosen and wilfully retained. It was one of the

main objects of early co-operative lectures to found a new art of

association, and those who founded co-operation under Robert Owen,

had enduring enthusiasm which no difficulty dismayed—no disaster

chilled.

The principal business item recorded of this year is the honest one

that £500 more was paid towards the new mill account. A larger-sized

report was printed, giving for the first time the board of

management and twenty names of directors, Edwin Gaunt being

secretary.

1851.

――♦――

"SOMETHING WRONG "―DEMOCRATIC DUTY IN COMPLAINT―CO-OPERATIVE

QUALITIES―IRRECONCILABLES RECONCILED BY A REAL AUDIT―MR. PLINT'S

MASTERLY EXAMINATION―HIS WISE AND BOLD COUNSEL.

THIS year a directors' report appeared—argumentative,

explanatory, and instructive. In the four years of the existence of

the Society to this date (1851), the price of corn had fluctuated

from 1s. to 1s. 7d. a stone, which must have given trouble to

directors and perturbed the minds of members, who would suspect

overcharges. Nevertheless, the Society made profit and increased its

members to 2,997. Like prudent men, the directors insured their

property for £2,000, notwithstanding that the premium reduced the

dividend. Security is always a good investment.

Amid the many members allured by prospect of profit, but who had

never caught the co-operative spirit, some began to express the

opinion that there was "something wrong." Those who did not

understand accounts were persuaded the balance sheets were wrong. In

a democratic society, such as all co-operative societies are,

explicitness of administration is indispensable—not only should

those in control be honest, but they should be at the trouble to

show they are so, and reasonable facilities should be open to every

member for satisfying himself that his affairs are well conducted. For democratic confidence it is necessary that the business should

be openly, not secretly conducted, as it is in a private concern. But at the same time this democratic advantage imposes upon members

corresponding good faith, good patience, and good temper. They

should entertain no suspicion until they have inquired, observed,

and assured themselves that there is good ground for it. It is a

fault of the first magnitude to make imputations against the honesty

of any man, unless he who makes it is assured of its truth. What is

not or cannot be proved should be regarded as non-existent. Before

any open expression of adverse opinion is ventured upon, inquiry

should be made of the committee or of the department responsible for

what is suspected to be wrong. Had such considerations been in the

minds of members, the Leeds Society would have had smooth water to

sail in, and have reached the port of prosperity long before it did.

One thing members are very apt to forget is that shopmen, and all

employed in a democratic society, are placed at a disadvantage

compared with servants in a private firm. There they have only one,

or perhaps two or three masters. In a Society like Leeds now, they

have 37,000 masters. In some societies every member, because he is a

joint master, virtually acts as one, and often speaks to those

employed in a masterful way. Whereas complaints should be made, as

far as possible, to the committee, and one of them should make

representations and give directions. On the other hand, the duty of

every officer, in any capacity, is to be civil to every member, and

the duty of every member to be civil to him. Patience, forbearance,

discrimination, and helpfulness are co-operative qualities. The best

construction that can be put upon conduct are the virtues that make

co-operative intercourse so pleasant to members, and those employed

by them. It is these experiences which make the history of the Leeds

Society so instructive to others. All the lights and shadows of

co-operative association are reflected here. It in no way disquiets

the living to learn that predecessors now dead, erred through lack

of experience.

It is often said that the most "charitable" construction should be

put on the acts of others. It is not "charity" but justice which is

wanted in judging. Charity is condescension. Where there is

justice in judgment, charity is rarely needed.

When members get dissatisfied and believe the accounts are

deceptive, the business of the society begins to fall off. At this

stage (1851) the Leeds Society had the advantage that it always has

had—the advantage of having directors who conducted business in an

honest, straightforward manner, and no disruption took place. But

there were, nevertheless, some members whom apparently nothing could

satisfy. There are irreconcilables in social life as well as in

political life, and the executive wisely resolved that all accounts

should be again thoroughly investigated by an outside, independent,

responsible accountant of known capacity, who should also audit

their books. Such a person was Mr. T. Plint, who was engaged, at a

cost of £40, to examine and audit all the accounts of the Society

from the commencement in 1847 to the end of 1851. Mr. Plint's

instructions were "not only to strictly examine the current balance

sheet, but every previous balance sheet." The members elected a

special committee to see the work done and report thereon. Mr. Plint

very properly took an entirely independent way of his own. In due

course he reported—

"1. All the calculations or castings out, whether of sales or

purchases, have been checked.

"2. All additions whatever have also been examined in all the books.

"3. All the postings have been checked.

"4. All payments entered in the cash book have been compared with

the vouchers.

"5. The bank account has been compared with the cash book, and also

with the ledger receipts, credited to the various shopkeepers or

customers of the Society, and I find the books correct and

exhibiting great care and painstaking, as well as skill in their

management. They also show indubitable proof of a careful audit. I

have also examined the half-yearly cash and stock accounts, and they

correctly represent the state of the Society's affairs at the

respective periods. As the balance sheet drawn up by me from an

independent analysis of the accounts for the entire four years

harmonises with the half-yearly balance, it therefore virtually

proves the accuracy of all the preceding ones."

This report was most conclusive, and had the effect of creating

great confidence in the members, who asked the directors to have it

printed and circulated throughout the Society.

Mr. Plint rendered a further service. He explained what improvement

might be made in the books of a corn mill, by which some corn mills

to this day might profit. Mr. Plint rendered still greater service. He included in his report advice to the Society, both as to practice

and policy. Mr. Plint was a model auditor. I have seen, in an

important society, an auditor who added to his report his opinion of

improvements required for the security of its operations, and for

better conformity to its principles, put down by rude and peremptory

disapproval; it being considered no business of an auditor to give

any such opinion, but to confine himself to the accuracy of the

accounts put before him. Whereas it is the business of an honest

auditor not to be merely content with the account given to him, but

to inquire for others which may be necessary for him to understand

the solvency of the society. An audit which does not imply or

include that knowledge, is false and fraudulent in its effect—as the

Bankruptcy Court reveals to us every week. The professional auditor

has a large range of knowledge and experience, and can see where a

society is going wrong, of which the most honest-minded directors

may not be aware. One passage from Mr. Plint's report is memorable

for its wisdom and its guidance. He says:—"I am aware that the

immediate and great object of the Society is to furnish a good

article to its members, on cheaper terms than is done by individual

action, and the ordinary processes of exchange. Whether those ends

are secured or not may be tested by the simple process of

comparison, as respects the article produced and its price; and on

the supposition that these tests show favourably for the Society, it

might be held enough to show by the accounts that the Society was

adding to its capital yearly, without going into minute analysis. This, however, would be a dangerous procedure—dangerous because

liable greatly to mislead. A co-operative society can only be safe

whilst keeping pace in its general management and in the processes

of manufacture with the competitive trader, and the fact that a

society does so keep pace is only demonstrable by a careful

comparison of cost of production and of mercantile profits. The

chances of perpetuity are nil to a society which is so far behind

the individual trader that it cannot keep its capital intact, and at

the same time to supply its members with commodities at less price

than the private dealer. The least favourable condition on which

such a society can do this is that of equal economy of production,

and equal skill in general management; if, indeed, to encounter the

contingencies and vicissitudes of business affairs, the economy and

skill ought not to be greater, rather than simply equal. It is

evident, too, that before calculating the nett annual increment of

capital, due allowance must be made for wear and tear of fixed

capital, and provision made by a reserve fund to meet those

extraordinary expenses which may arise from accident, the

substitution of improved machines or motive power; and those other

contingencies to which nearly all the manufacturing arts are liable.

I need not point out the absolute necessity,

in order to the success of the society, not merely of satisfying the

members at large, that its affairs are conducted with integrity, but

also of demonstrating that, as a business concern and tested by

admitted business principles, it rests on a safe and stable

foundation." Not many societies find an auditor

so wise and bold as Mr. Plint.

1852.

――♦――

A REMARKABLE AUDIT—THE TROUBLE OF PURITY—DISADVANTAGE OF

CHEAPNESS—DIVIDENDS SHOULD BE PALPABLE—CONCEALED

PROFITS—REMUNERATIVE PRICES ADOPTED CARE IN TERMS GOOD POLICY—THE

OLD MAN AND HIS THREE STONES OF FLOUR.

THERE was better bookkeeping in the Leeds Society than has fallen to

the lot of most societies in their earlier years. Though Mr. Plint

arrived at his results by a different method from that on which the

Society's books were kept, the conclusions he arrived at were

precisely the same. It was certainly notable, seeing that the values

to be estimated were so difficult as those of actual property and

profits. Mr. Plint's audit was made in December, six months after

the directors made their report to the members.

The directors had reported that the worth of the Society on

|

July 1st, 1851, was … … …

… … … |

£4,278 13 3½ |

|

Mr. Plint found it to be … … …

… |

£4,278 13 3½ |

|

The directors show that there was due |

|

|

to subscriptions … … … …

… … |

£3,401 6 9 |

|

|

Mr. Plint shows that there was due … |

£3,401 6 9 |

|

The directors show a profit of … …

… |

£877 6 6½ |

|

Mr. Plint shows a profit of … …

… … |

£877 6 6½ |

The committee justly say that, considering Mr. Plint arrived at his

results by an entirety separate and different analysis, the exact

coincidence of both sets of figures was remarkable. In the

transactions of a new business,

though its returns amounted to £90,000, there had not been a

defalcation of sixpence. Some members had objected to the trade

expenses. To them it was pointed out that some were peculiar to a

co-operative society at its commencement—for instance, a greater

number of officers, and expenses of public meetings. The number of

officers diminish in time, but are indispensable at the beginning,

as their vigilance promotes confidence as well as creates the habits

of order. Publicity is a source of increase of members, the expense

of which is nothing as compared with ordinary business advertising.

The names of the committee who thus vindicated the veracity of the

bookkeeping and integrity of the Society were—Luke Pool, Thomas

Atkinson, David Vaup, R. M. Carter, and E. Gaunt, secretary.

The Society had taken the wise resolution of insuring purity of the

flour they sold, and no admixture deteriorated it. The flour was

pure and unadulterated. The average cost of the grain purchased to

grind into flour was higher than the average cost of grain in the

whole country. It required great faith in principle, great courage

to do this, and the directors had the courage. The common principle

of commercial business is to buy in the cheapest market and sell in

the dearest. The directors followed the better rule of buying in the

best market and supplying the poorest member with the best quality

of food, which working people in Leeds had never had before. This

unseen benefit did not tell upon unintelligent members. Their eyes

were fixed upon mere cheapness. Their own health and that of their

families were not thought of by them. In many houses disease and

death from impure food were notorious facts in the town, before the

People's Mill was established. From these calamities the homes of

members were exempted, but the ignorant among new members gave

little heed to this. That is why an educational fund, which did not

exist then, was wanted. As Canon Kingsley said, "Cheapness is

nastiness." But a man requires some intelligence to recognise

nastiness, and dislike it. Besides, as the committee had found out,

this very purity of food was against them. Its appearance was

disliked. There was an uninstructed preference for white flour. The

members had no experience and no knowledge of the appearance of pure

flour. The women did not like the colour of it. They did not know

that the competitive miller did not scruple to produce whiteness by

the adulteration of alum. But the intelligence of Leeds was not

lower than that of other towns. For in those days the middle class,

as a rule, knew neither the colour nor the taste of pure food. Their

taste had never been educated, as the taste of co-operators is now. A friend of mine, Mr. George Huggett, secretary of the Westminster

Reform Association, opened a coffee shop in Lambeth, that workmen

might have genuine coffee in the early morning on going to their

workshops. But, when they tasted it, they were indignant. They did

not like the appearance of it, they did not like the colour of it,

they did not like the aroma of it. They had never seen pure coffee

nor tasted it. They did not know that what they drank was

adulterated with vile ingredients. My friend had to close his shop;

burnt beans, glucose, and mustard to give it a little pungency, were

preferred by his customers.

It took two years to educate the taste of many of the Leeds members

before they became reconciled to genuineness. It has taken longer

elsewhere.

In one respect the earlier directors had put their successors at a

disadvantage from the beginning. They had pledged them to sell not

only genuine flour, but at a cheaper price, whereas the sound

principle of co-operative business is to sell at the average market

price of the day, and not at the lowest. To aim at selling things

cheaper is to get upon the inclined plane of competition, and those

upon it commonly slide down into the gutter of commercial smartness,

from which co-operation promised to save the public. By selling at

the market price the consumer pays no more than he has to pay

elsewhere, and he has the advantage of pure articles and just

measure, with the additional advantage of knowing that all the

profits of honest trading will come into his pockets at the end of

each half year in the shape of dividend. Cheap selling reduces the

dividend and does not encourage provident and saving habits. The

little gain in cheapness, week by week, is a small benefit to the

family who still live from hand to mouth, while the saving at the

end of the half year, or the end of the year, is a substantial

addition to the wealth of the household, and, if left in the store

for investment, is the beginning of small fortunes. Under the policy

of cheapness the store enters into competition with the tradesman,

and is a continual irritation to him; whereas stores which keep to

the average price benefit the shopkeeper, who can obtain better

prices for his commodities since no customer can say "he can get

things cheaper at the co-operative store." Then the shopkeeper feels

he has no competitor in the stores so far as prices are concerned. In this way co-operative stores have made the fortunes of many

grocers who never yet made the fortune of any co-operative store.

Some corn mill members were early dissatisfied with the profits made

by the mill. Had there been only average market price selling, the

profit to the members would have been clear, palpable, and

surprising. They had gained in money indirectly, and did not know

it. They had gained by the price at which the Society sold flour to

them:―

|

|

£ s d |

|

114 weeks at 1d. per stone less |

1,958 18 0 |

|

38 … … 2d.

… … … |

1,305 18 8 |

|

5 …

… 3d. … …

… |

257 15 0 |

|

2 … … 4d.

… … … |

137 9 3 |

|

|

£3,660 0 11 |

This was the unseen, unknown, uncounted profit they had really

gained, which, with the £877 members had already received, made the

real profit of the Society £4,537, more than £3,000 of which had been

concealed or kept out of sight. Thus was mainly produced the

discontent among them. The Society, by sacrificing their own

interests to cheap selling, had conferred a benefit upon the town by

the reduction they had caused of 2d. a stone in the price of flour. For this the town had no gratitude, and on account of it never

furnished to the Society a single friend; at least, it mitigated no

hostility—it never awakened any popular interest or respect for this

great service rendered to it.

The only defence of cheap selling was that it attracted, at first,

members. But the reputation of combined profits of nearly £5,000

coming into the hands of members would have brought them more

adherents, and of a better quality than they had, judging from the

chronic cries of discontent heard in season and out of season.

But if a larger survey be taken, including the price at which the

members would have had to pay, had not the Society reduced the

average price in the town, it will be seen how largely members had

benefited.

From October, 1847, to July, 1851 (196 weeks), the Society sold

flour from one penny to fourpence per stone below the market price. This had the effect of lowering the price through the

whole borough. When the flour mill began, flour was 2s. 4d. per stone, which the

Society sold at 2s. 1d. per stone, being 3d. per stone below the