|

[Previous

page]

CHAPTER XXXVII.

THE TEN CONGRESSES

"We ought to resolve the economical problem, not by means

of an antagonism of class against class; not by means of a war of workmen

and of resistance, whose only end is a decrease of production and of

cheapness; not by means of displacement of capital which does not increase

the amount of social richness; not by the systems practised among

foreigners, which violate property, the source of all emulation, liberty,

and labour; but by means of creating new sources of capital, of production

and consumption, causing them to pass through the hands of the operatives'

voluntary associations, that the fruits of labour may constitute their

property."—GIUSEPPE MAZZINI,

Address to the Operatives of Parma (1861).

THIS comprehensive summary of co-operative policy

exactly describes the procedure and progress gradually accomplished in

successive degrees, at the ten Congresses of which we have now to give a

brief account.

The Central Board have published every year during its

existence closely-printed Reports of the annual Congress of the societies.

Ten Reports have been issued. [276]

They contain the addresses delivered by the presidents, who have mainly

been men of distinction; the speeches of the delegates taking part in the

debates; speeches delivered in the town at public meetings convened by the

Congress; the papers read before the Congress; foreign correspondence with

the leading promoters of Co-operation in other countries. These

reports exhibit the life of Co-operation and its yearly progress in

numbers, conception, administration, and application of its principles.

Though the Reports are liberally circulated they are not kept in print,

and thus become a species of lost literature of the most instructive kind

a stranger can consult. These annual reports, and the annual volumes

of the Co-operative News, can be kept in every library of the

stores, and every store ought to have a library to keep them in.

There have been three series of Congresses held in England

within forty years—a Co-operative series, a Socialist series, and the

present series commencing 1869. The first of the last series was

held in London.

The following have been the Presidents of the Congresses and

names of the towns in which they were held:—

|

1869. Thomas Hughes, M.P., London.

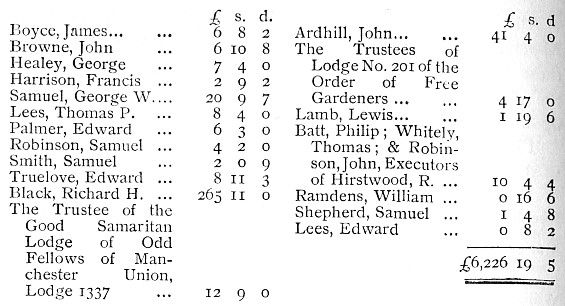

1870. Walter Morrison, M.P., Manchester.

1871. Hon. Auberon Herbert, LP., Birmingham.

1872. Thomas Hughes, M.P., Bolton.

1873. Joseph Cowen, Jun.,[277]

Newcastle

1874. Thomas Brassey M.P., Halifax.

1875. Prof. Thorold Rogers, London.

1876. Prof. Hodgson, LL.D., Glasgow.

1877. Hon. Auberon Herbert, Leicester.

1878. The Marquis of Ripon, [278]

Manchester.

|

Mr. Thomas Hughes, M.P., was the president of the first

Congress. He was one of the chief guides of the co-operative

Israelites through the wilderness of lawlessness into the promised land of

legality. From the Mount Pisgah on which he spoke he surveyed the

long-sought kingdom of co-operative production, which we have not yet

fully reached.

Among the visitors to the first Congress of 1869 were the

Comte de Paris, Mr. G. Ripley, of the New York Tribune, the Hon. E.

Lyulph Stanley, Mrs. Jacob Bright, Henry Fawcett, M.P.; Thomas Dixon

Galpin, T. W. Thornton, Somerset Beaumont, M.P. ; F. Crowe (H.B.M.'s

Consul-General, Christiania, Norway), Sir Louis Mallet, Sir John Bowring,

Colonel F. C. Maude, William Shaen, the Earl of Lichfield, and others.

Prof. Vigano, of Italy, contributed a paper to this Congress;

and a co-operative society of 700 members, at Kharkof, sent M. Nicholas

Balline as a delegate. On the list of names of the Arrangement

Committee of the Congress was that of "Giuseppe Dolfi, a Florentine

tradesman, who, more perhaps than any other single person, helped to turn

out a sovereign Grand Duke, and remained a baker." [279]

He was a promoter of the People's Bank and the Artisan Fraternity of

Florence. There was an Exhibition of co-operative manufactures at

this Congress, which has been repeated at subsequent Congresses.

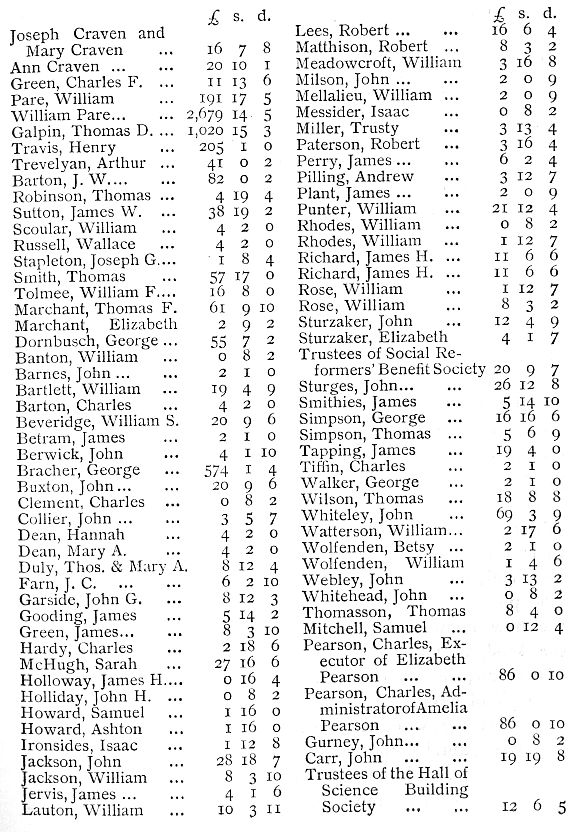

The following list of names of the first Central Board of the

Co-operators, which was appointed at the 1869 Congress, includes most of

those who have been concerned in promoting the co-operative movement in

the Constructive Period. Mr. Pare and Mr. Allen have since died:—

|

LONDON.

Thomas Hughes, M.P.

Walter Morrison, M.P.

Anthony J. Mundella, M.P.

Hon. Auberon Herbert, M.P.

Lloyd Jones.

William Allen, Secretary of the Amalgamated Engineers'

Society.

Robert Applegarth, Secretary of the Amalgamated Carpenters

and Joiners' Society.

Edward Owen Greening, Managing Director of Agricultural

and Horticultural Co-operative

Association.

James Hole, Secretary of the Association of Chambers of

Commerce.

George Jacob Holyoake.

John Malcolm Ludlow.

E. Vansittart Neale.

William Pare, F.S.S.

Hodgson Pratt, Hon. Secretary of the Working Men's Club

and Institute Union.

Henry Travis, M.D.

Joseph Woodin.

PROVINCIAL.

Abraham Greenwood, Rochdale.

Samuel Stott, Rochdale.

T. Cheetham, Rochdale.

William Nuttall, Oldham.

Isaiah Lee, Oldham.

James Challinor Fox, Manchester.

David Baxter, Manchester.

Thomas Slater, Bury.

James Crabtree, Heckmondwike.

J. Whittaker, Bacup.

W. Barn At, Macclesfield.

Joseph Kay, Over Darwen.

William Bates, Eccles.

J. T. McInnes, Glasgow, Editor of the

Scottish Co-operator.

James Borrowman, Glasgow. |

The Congress of 1870 was held in the Memorial Hall,

Manchester. The practical business of Co-operation was advanced by

it. Mr. Walter Morrison, M.P., delivered the opening address, which

dealt with the state of Co-operation at home and abroad, and occupied

little more than half an hour in delivery. Subsequent addresses have

exceeded an hour. The example of Mr. Morrison was in the direction

of desirable limitation. As a chairman of Congress Mr. Morrison

excelled in the mastery of questions before it, of keeping them before it,

of never relaxing his attention, and never suffering debate to loiter or

diverge. Mr. Hibbert, M.P., presided the third day. At this

Congress, as at subsequent ones, during Mr. Pare's life, foreign delegates

and foreign correspondence were features.

The Birmingham Congress of 1871 met in the committee-room of

the Town Hall. The Hon. Auberon Herbert, M.P., was president.

He spoke on the fidelity and moral passion which should characterise

co-operators. Mr. Morrison, M.P., occupied the chair the third day.

Mr. George Dixon, M.P., presided at the public meeting in the Town Hall.

The Daily Post gave an article on the relation of Co-operation to

the industries of the town. All the journals of the town gave fuller

reports of the proceedings of the Congress than had been previously

accorded elsewhere. At this Congress a letter came from Herr

Delitzsch; Mr. Wirth wrote from Frankfort; Mr. Axel Krook from Sweden.

Dr. Muller, from Norway, who reported that co-operative stores were

extending to the villages; and that there is a Norwegian Central Board.

Prof. Pfeiffer sent an account of military Co-operation in Germany—a form

of Co-operation which it is to be hoped will die out. Denmark,

Russia, Italy, and other countries were represented by communications.

The Congress of 1872 was held in Bolton.

Bolton-le-moors is not an alluring town to go to, if regard be had alone

to its rural scenes or sylvan beauty; but, as respects its inhabitants,

its history, its central situation, its growth, its manufacturing and

business importance, its capacious co-operative store, and the hospitality

of distinguished residents, it is a suitable place to hold a Congress in.

The town has none of the grim aspect it wore of old, when it was warlike

within, and bleak, barren, and disturbed by enemies without. Flemish

clothiers sought out the strange place in the fourteenth century, and

possibly it was Flemish genius which gave Arkwright and Crompton to the

town. In 1651 one of the Earls of Derby was beheaded there.

The latest object of interest in the town is a monument of Crompton, who

made the world richer, and died an inventor's death—poor. Bolton,

however, did not owe Co-operation to Flemish, but to Birmingham

inspiration. Forty-two years before, Mr. Pare delivered the first

lecture given in Bolton upon Co-operation, in March, in 1830. He

spoke then in the Sessions Room of that day (which is now an inn), mostly

unknown to this generation. I sought in vain for the Bolton

Chronicle of the year 1830, to copy such notice as appeared of Mr.

Pare's meeting. Unluckily, the Chronicle office had itself no

complete file of its own journal. The public library of the town was

not more fortunate. The volumes of the Chronicle about the

period in question in this library are for 1823, 1825, 1829, and 1835.

The 1830 volume was not attainable, so that the seed was not to be traced

there which was found upon the waters after so many days. [280]

Many remember it as the Bolton wet Congress. Even

Lancashire and Yorkshire delegates were not proof against Bolton rain.

The Union Jack persevered in hanging out at the Congress doors, but

drooped and draggled mournfully, and presented a limp, desponding

appearance. Even the Scotch delegates, who understand a climate

where it always rains, except when it snows, came into the hall in Indian

file, afraid to walk abreast and confront the morning drizzle, against

which no Co-operation could prevail. Some unthinking committee

actually invited Mr. Disraeli, then on a visit to Manchester, to attend

the Conference. Crowds would be sure to surround the splendid

Conservative, and it would be sure to rain all the time of his

visit—everybody knew that it would in Manchester—and yet the

co-operators invited him and the Countess Beaconsfield to come dripping to

Bolton with the 10,000 persons who would have followed. The town

would have been impassable. The Co-operative Hall held a fifth part

of them; and there would not have been any business whatever transacted

while Mr. Disraeli sat in the Congress. It is not more foolish to

invite the dead than to invite eminent living persons, unless it is known

that they are likely to come, and can be adequately entertained when they

do come. To the outside public it is apt to appear like ignorant

ostentation. I have known a working-man's society, without means to

entertain a commercial traveller pleasantly, invite a cluster of the most

eminent and most engaged men in the nation, of such opposite opinions that

they never meet each other except in Parliament, to attend the opening of

a small hall in an obscure town, where the visitors pay ninepence each for

tea, when a great city would deem it an honour if one of them came as its

guest.

This Congress held a public meeting in the same hall where

Schofield, the republican, was murdered not long before in the Royalist

riots in the town. It was during this Congress that Professor

Frederick Denison Maurice died. Knowledge of his influential

friendliness to Co-operation caused every delegate to be sorry for his

loss. Few co-operators probably among the working class were able to

estimate Mr. Maurice's services to society, or measure that range of

learning and thought which has given him a high place among thinkers and

theologians. A man can be praised by none but his equals, but the

tribute of regret all who are grateful can give, in the respects in which

they understand their obligations. This co-operators could do, for

they were aware he had founded Working Men's Colleges in London to place

the highest education within the reach of the humble children of the

humblest working man in the nation. Mr. Neale, to whom I suggested

the propriety of such a resolution, and to whom it had not occurred, said

I had better write it—which I did. It was carried with grateful

unanimity.

At this Congress M. Larouche Joubert informed us that the

Co-operative Paper Manufactory made £20,000 of profits between June, 1870,

and June, 1871—a period so disastrous to France. It used to be the

common belief that Co-operation would fall to pieces in trying times, but

in Lancashire it stood the test of the great cotton famine, and in France

it stood the test of war. Equally during the German war the

co-operative credit banks were unshaken. Professor Burns, writing

from Italy, told us of the interest taken by Baron Poerio in a

Co-operative Society of Naples, which actually existed among a generation

reared under a government of suspicion. M. Valleroux reported that

not a single productive society gave way in Paris neither under the siege

nor the Commune.

Mr. Villard, the secretary of the Social Science Association

of America, supplied a survey of co-operation in America, and papers were

expected from M. Élisée

and his brother M. Élie Reclus, of

France, eminent writers on Co-operation. They would have been

present had not the suppressors of the Commune laid their indiscriminating

hands on one of them. Too late M. Élisée

Reclus was liberated from Satory, where he was confined by misadventure,

on account of alleged complicity with the affairs of the Commune, which he

opposed and deplored, being himself a friend of pacific, social, and

industrial reform. He was (and his brother also) a prominent member

of a society for promoting peace and arbitration of the national

differences which led to war. Élisée

Reclus being an eminent man of science, whose works have been translated

into English, great interest in his welfare was felt by men of science in

this country. M. Élisée's

work upon the "Earth" is held in high repute among geographers. The

memorial signed in this country, and presented to M. Thiers on his behalf,

bore many eminent signatures, and was happily successful, as M. Reclus's

life was in danger from privation and severity of treatment.

The Congress of 1873 was held in the Mechanics' Institution

of Newcastle-on-Tyne, Mr. Joseph Cowen, jun., being president. His

was the first extemporaneous address delivered to us, and its animation,

its freshness of statement, and business force made a great impression.

It was the speech of one looking at the movement from without, perfectly

understanding its drift, and under no illusions either as to its leaders

or its capacity as an industrial policy.

At this Congress was recorded the death of Mr. Pare. It

was he who first introduced the American term Congress into this country,

and applied it to our meetings. For more than forty years he was the

tireless expositor of social principles.

Newcastle is an old fighting border town; there is

belligerent blood in the people. If they like a thing, they will put

it forward and keep it forward; and if they do not like it, they will put

it down with foresight and a strong hand. There is the burr of the

forest in their speech, but the meaning in it is as full as a filbert,

when you get through the shell. Several passages in the speeches of

the President of the Congress give the reader historic and other knowledge

of a town, distinguished for repelling foes in warlike times, and for

heartiness in welcoming friends in industrial days. The delegates

were handsomely taken down the Tyne by Mr. Cowen in the Harry Clasper

steamboat; there was a Central Board meeting going on in the cabin, and a

public meeting on the deck. If co-operators held a Congress in

Paradise they would take no time to look at the fittings, but move

somebody into the chair within ten minutes after their arrival. On

leaving the Harry Clasper a salute of forty-two guns was fired in

honour of the forty-two elected members of the Central Board, a tribute no

other body of visitors had received in Newcastle, and no Central Board

anywhere else since. The delegates were welcomed to the Tyneside

with a greater hospitality even than that of the table-namely, that of the

Press. The Newcastle Daily Chronicle accorded to the Congress

an unexampled publicity. It printed full reports of the entire

proceedings, the papers read, the debates, and the speeches at every

meeting. When the British Association for the Advancement of

Science, and the kindred Society for the Promotion of Social Knowledge,

visited Newcastle-on-Tyne, the Daily Chronicle reported their

proceedings in a way never done in any other town of Great Britain or

Ireland, and the Co-operative Congress received the same attention.

Double numbers were issued each day the Congress sat, and on the following

Saturday a supplement of fifty-six columns was given with the Weekly

Chronicle, containing the complete report of all the co-operative

deliberations. Thanks were given to Mr. Richard Bagnall Reed, the

manager of the Newcastle Chronicle, for that tireless prevision

which this extended publication involved. Of the Chronicle,

containing the first day's proceedings of the Congress, 100,000 copies

were published, and 90,000 sold by mid-afternoon. The same paper

contained a report of a great meeting on the Moor, of political pitmen,

which led to the large sale; but the cause of Co-operation had the

advantage of that immense publicity. The Newcastle Moor of 1,200

acres was occupied on the first day of the Congress by a "Demonstration"

of nearly 100,000 pitmen, and as many more spectators, on behalf of the

equalisation of the franchise between town and county. The richly-

bannered procession marched with the order of an army, and was the most

perfect example of working-class organisation which had been witnessed in

England.

Mr. Cowen, the president of the Congress, was chairman of

this great meeting on the Moor. The Ouseburn Co-operative Engineers

carried two flags, which they had asked me to lend them, which had seen

stormier service. One was the salt-washed flag of the Washington,

which bore Garibaldi's famous "Thousand" to Marsala, and the other a flag

of Mazzini's, the founder of Italian Co-operative Associations, which had

been borne in conflicts with the enemies of Italian unity. The best

proof of the numbers present is a publication made by the North Eastern

Railway Company of their receipts, which that week exceeded by £20,224 the

returns of the corresponding week for 1872, which represented the

third-class fares of pitmen, travelling from the collieries of Durham and

Northumberland to the Newcastle Moor. The Congress also made

acquaintance with the oarsmen of the Tyne. A race over four miles of

water between Robert Bagnall and John Bright was postponed until the

Wednesday, as Mr. Cowen thought it might entertain us to see it, and it

was worth seeing, for a pluckier pull never took place on the old Norse

war-path of the turbulent Tyne.

It was this year that Mr. Walter Morrison, M.P., presented

the Congress with eight handsomely, mounted minute glasses, which, out of

compliment it would appear to the Ouseburn Engineers, were described as

Speech-Condensing Engines. Four of the glasses ran out in five minutes and

four in ten minutes. The object of the gift was to promote brevity and

pertinence of speech. There has been engraved upon each glass a couplet

suggesting to wandering orators to moderate alike their digressions and

warmth; to come to the point and keep to the point—having, of course,

previously made up their minds what their point was. The couplets are

these—

|

Often have you heard it told,

Speech is silver, silence gold.

_____________

Wise men often speech withhold,

Fools repeat the trite and old.

_____________

Shallow wits are feebly bold,

Pondered words take deeper hold.

_____________

Time is fleeting, time is gold,

When our work is manifold.

_____________ |

If terseness be the soul of wit,

Say your say and be done with it.

_____________

Fluent speech, wise men have said,

Oft betrays an empty head.

_____________

Conscious strength is calm in speech,

Weaker natures scold and screech.

_____________

Patience, temper, hopefulness,

Lead you onward to success.

_____________ |

In Athens, an accused person, when defending himself before

the dikastery, was confronted by a klepsydra, or water glass. The

number of amphoræ of water allowed to

each speaker depended upon the importance of the case. At Rome, the

prosecutor was allowed only two-thirds of the water allowed to the

accused. At the Congress, the five-minute glass was generally in

use, the ten-minute one when justice to a subject or a speaker required

the longer time.

The Congress of 1874 was held in Halifax, when Mr. Thomas

Brassey, M.P., was president, who gave us information as to the conditions

of co-operative manufacturing. The authority of his name and his

great business experience rendered his address of importance and value to

us. The store at Halifax had come by this time to command attention,

and the co-operative and social features introduced into the manufactories

of the Crossleys and the Ackroyds rendered the meeting in that town

interesting.

Professor Thorold Rogers, of Oxford, presided at the London

Congress of 1875. He stated to us the relations of political economy

to Co-operation, sometimes dissenting from the views of co-operative

leaders, but always adding to our information. It is the merit it of

co-operators that they look to their presidents not for coincidence of

opinion but for instruction. Not less distinguished as a politician

than as a political economist, the presence of Professor Rogers in the

chair was a public advantage to the cause.

Mr. Wendell Phillips, of America, was invited by the Congress

to be its guest. The great advocate of the industrial classes,

irrespective of their colour, would have received distinguished welcome

from co-operators who regard the slaves as their fellow working men, and

honour all who endow them with the freedom which renders self-help

possible to them. Mr. Phillips was unable to leave America, but a

letter was read to the Congress from him.

At this Congress in a paper contributed, N. Zurzoff explained

the introduction and progress, of Schulze-Delitzsch's banking system in

Russia. It was met by a very unfavourable feeling on the part of the

Russian Government and the people. They did not understand it and

did not want it. It took Prince Bassilbehikoff no little trouble to

make it intelligible in St. Petersburg. In 1870 thirteen banks were

got into operation; in 1874, more than two hundred. At the same

Congress Mr. Walter Morrison read a paper giving an English account of the

history, nature, and operation of the Schulze-Delitzsch German Credit

Banks, the fullest and most explicit.

A proposal was made at this Congress to promote a

co-operative trading company between England and the Mississippi Valley,

and a deputation the following year went out to ascertain the feasibility

of the project. Friendly relations have been established between the

better class of Grangers. It is necessary to say better class,

because some of them were concerned in obtaining a reduction of the

railway tariff for the conveyance of their produce, by means which

appeared in England to be of a nature wholly indefensible. But with

those of them who sought to promote commercial economy by equitable

co-operative arrangements, they were anxious to be associated. The

plan devised by Mr. Neale, who was the most eminent member of the

deputation, would promote both international Co-operation and free trade;

objects which some of the co-operative societies made large votes of money

to assist. [281]

At the Glasgow Congress of 1876, Professor Hodgson, of

Edinburgh, was our president. In movements having industrial and

economical sense, Professor Hodgson's name was oft mentioned as that of a

great advocate of social justice whose pen and tongue could always be

counted upon. The working class Congress at Glasgow had ample proof

of this. Political economy has no great reputation for liveliness of

doctrine or exposition; but in Professor Hodgson's hands its exposition

was full of vivacity, and the illustrations of its principle were made

luminous with wit and humour.

At this Congress, Mr. J. W. A. Wright was present as a

delegate from the Grangers of America, who had passed resolutions in their

own Conferences to promote "Co-operation on the Rochdale plan." Mr.

Neale and Mr. Joseph Smith promoted an Anglo-American co-operative trading

company.

The Museum Hall, Leicester, was the place in which the

Congress of 1877 was held. The Hon. Auberon Herbert was president

this year, and counselled us with impassioned frankness against the

dangers of centralisation and described merit, unseen by us in the

adjusting principle of competition. He owned we might regard him as

a devil's advocate, to which I answered that if he were so, we all agreed

the devil had shown his excellent taste in sending us so earnest and

engaging a representative. For the first time a sermon was preached

before the delegates by Canon Vaughan, whose discourse was singularly

direct. It dealt with the subject knowingly, and with that only; and

the subject was not made—as preachers of the commoner sort have often

made it—a medium of saying some thing else. It dealt with

Co-operation mathematically. Euclid could not go from one point to

another in a shorter way. No delegate at the Congress could

understand Co-operation better than the Canon; he made a splendid plea for

what is regarded as an essential principle of Co-operation—the

recognition of labour in productive industry—the partnership of the

worker with capital. The church was very crowded, and there was a

large attendance of delegates.

The Tenth Congress, that of 1878, was held in Manchester,

where great changes had occurred since the Congress of 1870, Balloon

Street had come to represent a great European buying agency; the Downing

Street store had acquired some twelve branches, and the Congress of 1878

was more numerous and animated in proportion. On the Sunday before

it opened, the Rev. W. N. Molesworth, of Rochdale, preached before the

delegates at the Cathedral, augmenting the wise suggestions and friendly

counsel by which co-operators had profited in their earlier career.

The Rev. Mr. Steinthal also preached a sermon to us the same day.

The Marquis of Ripon presided at the Congress, recalling the delegates to

the duty of advancing the neglected department of production. We

criticised with approval the Marquis's address. My defence was that

it was our custom, as we regarded the Presidential address as Parliament

does a royal speech, concerning which Canning said Parliament receives no

communication which it does not echo, and it echoes nothing which it does

not discuss. On the second day the Lord Bishop of Manchester

presided, making one of those bright cheery addresses for which he was

distinguished: showing real secular interest in co-operative things.

His religion, as is the characteristic of the religion of the gentleman,

was never obtruded and never absent, being felt in every sentence, in the

justice, candour, and sympathy shown towards those whose aims he discerned

to be well intended, though they may have less knowledge, or other light

than his, to guide them on their path. The Rev. Mr. Molesworth

presided on one day as he had done at the Congress of 1870. Dr. John

Watts was president on the last day, delivering an address marked by his

unrivalled knowledge of co-operative business and policy, and that

felicity of illustration whose light is drawn from the subject it

illumines.

There was one who died during this Congress time, once a

familiar name—Mr. George Alexander Fleming. Between 1835 and 1846

there was no Congress held at which he was not a principal figure.

He was editor nearly all the time (thirteen years) of the New Moral

World, a well-known predecessor of the Co-operative News. We

used to make merry with his initials, "G. A. F.," but he was himself a

practical, active agitator in the social cause. A border Scot by birth

(being born at Berwick, Northumberland), he had the caution of his

countrymen north of the Tweed; and though he showed zeal for social

ideas, he had no adventurous sympathy with the outside life of the world;

and Socialism had an aspect of sectarianism in his hands. He was an

animated, vigorous speaker, and there was a business quality in his

writings which did good service in his day. After he left the movement he

soon made a place for himself in the world. Like many other able

co-operators, he was not afraid of competition, and could hold his own

amid the cunningest operators in that field. He took an engagement on the

Morning Advertiser, and represented that paper in the gallery of

the House of Commons until his death. He founded, or was chief promoter

and conductor of, the South London Press. He first became known to the

public as an eloquent speaker in the "Ten Hours' Bill" movement. All his

life, to its close, he was a constant writer. Of late years he was well

known to visitors at the Discussion Hall, in Shoe Lane, and the "Forum,"

in Fleet Street. He had reached seventy years of age, at which a man is

called elderly. About a year before, he married a second time. He was

buried at Nunhead. Many years ago, at a dinner given at the Whittington

Club to the chief Socialist advocates, he boasted, somewhat reproachfully,

that he then obtained twice as much income for half the work he performed

when connected with the social movement. But that was irrelevant, for the

best advocates in that movement did not expect to serve themselves so much

as to serve others. I have seen men die poor, and yet glad that they had

been able to be of use to those who never even thought of requiting them. The consciousness of the good they had done in that way was the reward

they most cared for. Mr. Fleming's merit was, that in the stormy and

fighting days of the movement, he was one of the foremast men in the

perilous fray, and therefore his name ought to be mentioned with regard in

these pages. Like all public men who once belonged to the social movement,

he was constantly found advocating and supporting, by wider knowledge than

his mere political contemporaries possessed, liberty both of social life

and social thought. I have often come upon unexpected instances in which

he was true to old principles, and gave influence and argument to them,

though quite out of sight of his old colleagues.

The hospitality to delegates commenced at Newcastle-on-Tyne has been a

feature with variations at most subsequent Congresses, the chief stores

being

mainly the hosts of the delegates. In Bolton and in Leicester, as on the

Tyneside and London, eminent friends of social effort among the people

entertained many visitors.

The Central Board have published a considerable series of tracts,

handbooks, special pamphlets, and lectures by co-operative writers, and

sums of

money every year are devoted to their gratuitous circulation. Any person

wishing information upon the subject of Co-operation, or the formation of

stores,

or models of rules for the constitution of societies, can obtain them by

applying to the Secretary of the Co-operative Union, Long Millgate,

Manchester.

The sons of industry owe respect to the co-operators who preceded them. They furnished the knowledge by which we have profited. They had more than

hope where others had despair. They saw progress where others saw nothing,

and pointed to a path which industry had never

before trodden. The pioneers who have gone before have, like Marco Polo,

or Columbus, or Sir Walter Raleigh, explored, so to speak, unknown seas

of industry, have made maps of their course and records of their

soundings. We know where the hidden rocks of enterprise lie, and the

shoals and

whirlpools of discord and disunity. We know what vortexes to avoid. The

earlier and later movement has been one army though it carried no hostile

flags.

Its advocates were all members of one parliament, which, though several

times prorogued, was never dissolved.

A movement is like a river. It percolates from an obscure

source. It runs at best but deviously. It meets with an immovable

obstacle and has to run round it. It makes its way where the soil is most

pervious to water, and when it has travelled through a great extent of

country, its windings sometimes bring it back to a spot which is not far

in advance of

its source. Eventually it trickles into unknown apertures which its own

impetus and growing volume convert into a track. Though making

countless circuits, it ever advances to the sea; though it appears to

wander aimlessly through the earth, it is always proceeding; and its very

length of

way implies more distributed fertilisation on its course. So it is with

human movements. A great principle has often a very humble source. It

trickles at

first slowly, uncertainly, and blindly. It moves through society as the

river does through the land. It encounters understandings as impenetrable

as granite,

and has to find a passage through more impressionable minds; it digresses

but never recedes. Like the currents which aid the river, principle has

pioneers who make a way for it, who, in they cannot blast the rocks of

stupidity, excavate the more intelligent strata of society. Though the way

is long

and lies through many a channel and maze, and though the new stream of

thought seems to lose itself, the great current gathers unconscious force,

new

outlets seem to open or themselves, and in an unexpected hour the

accumulated torrent of ideas bursts open a final passage to the great sea

of truth.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

THE FUTURE OF CO-OPERATION

|

"So with this earthly Paradise it is,

If ye will read aright, and pardon me,

Who strive to build a shadowy isle of bliss

Midmost the beating of the steely sea,

Where tossed about all hearts of men must be;

Whose ravening monsters mighty men shall slay,

Not the poor singer of an empty day."

WILLIAM MORRIS,

The Earthly Paradise. |

To the reader I owe an apology for having detained him so long over a

story upon which I have lingered myself several years. Imperious

delays have beset me, until I have been like one driving a flock to

market, who, having abandoned them for a time, has found difficulty in

re-collecting them. No doubt I have lost some, and have probably

driven up some belonging to other persons, without being aware of the

illicit admixture.

Mr. Morris's lines, prefixed to this chapter, are not

inapplicable to the story of labour seeking rights. For myself I am

no "singer," nor do I believe in the "empty day" which the poet modestly

suggests. No day is "empty" which contains a poet.

Nevertheless, I am persuaded that "the isle of bliss" will yet arise

"midmost the beatings of the steely sea," and that the "ravening

monsters," industrial and otherwise, which now intimidate society, "mighty

men" will one day "slay."

Society is improved by a thousand agencies. I only

contend that Co-operation is one. Co-operation, I repeat, is the new

force of industry which attains competency without mendicancy, and effaces

inequality by equalising fortunes. The equality contemplated is not

that of men who aim to be equal to their superiors and superior to their

equals. The simple equality it seeks consists in the diffusion of

the means of general competence, until every family is insured against

dependence or want, and no man in old age, however unfortunate or

unthrifty he may have been, shall stumble into pauperism. His want

of sense, or want of thrift, may rob him of repute or power, but shall

never sink him so low that crime shall be justifiable, or his fate a

scandal to any one save himself. The road to this state of things is

long, but at the end lies the pleasant Valley of Competence.

There is no equality in nature, of strength or stature, of

taste or knowledge, or force or faculty. Many may row in the same

boat, but, as Jerrold said, not with the same oars. But there may be

equivalence, though not equality in power: the sum of one man's powers may

be equal to another's if we knew how to measure the degrees of their

diversity. It is in equality of opportunity of developing the

qualities for good each man is endowed with, that is the immediate need of

mankind.

Machinery has become a power as great as though 100 millions

of giants had entered Great Britain to work for its people. And

these giants never feel hunger, or passion, or weariness, and their power

is immeasurable. Yet the lot of the poor is precarious, and the very

poor amount to millions. Yet somehow the giants have not worked

adequately for the many as yet. It is true that a higher scale of

life is reached by the poorer sort than of old; still they are but the

servants of capital, and are hired. Co-operation opens the door to

partnership.

When "Distribution shall undo excess and each man has enough"

for secure existence, the baser incentives to greed, fraud, and violence

will cease. The social outrages, the coarseness of life, at which we

are shocked, were once thought to be inevitable. Our being shocked

at them now is a sign of progress. The steps of society are—(1)

Savageness; (2) The mastership by chiefs of the ferocious; (3) The

government of ferocity tempered by rude lawfulness; (4) Rude lawfulness

matured into a general right of protection; (5) Protection insured by

political representation; (6) Ascendancy of the people diminishing the

arrogance and espionage of government; (7) Self-control matured into

self-support; when the philanthropist becomes merely ornamental and

charity and disease unnecessary evils. We are far from that state

yet; but Co-operation is the most likely thing apparent to accelerate the

march to it.

Sir Arthur Helps has told the public that "what Socialists

are always aiming at is paternal government, under which they are to be

spoilt children." Sir Arthur must have in his mind State

Socialists—very different persons from co-operators, who are Next Step

takers.

The co-operative form of progress is the organisation of

self-help, in which the industrious do everything, and devise that order

of things in which it shall be impossible for honest men to be idle or

ignorant, depraved or poor: in which self-help supersedes patronage and

paternalism.

Co-operation has been retarded by a spurious order of

"practical" men. These kind of people would have stopped the

creation of the world on the second day on the ground that it was no use

going on. Had the law of gravitation been explained to them, they

would have passed an unanimous resolution to the effect that it was

"impracticable." Had the solar system been floated by a company they

would not have taken a share in it, being perfectly sure it could never be

made to work; or if it were started they would have assured us the planets

would never keep time. Were the sun to be discovered for the first

time to-day they would not look at it, but declare it could never be

turned to any useful account, and discourage investments in it, lest it

should divert capital from the more important and more practical candle

movement. Had these people been told before they were born that they

would be "fearfully and wonderfully made"—that the human frame would be

very complicated—they would have been afraid to exist. They would

have looked at the nice adjustment of a thousand parts necessary to life,

and they would have declared it impossible to live.

The hopeless tone of many of the working class has been

changed by Co-operation. An artisan begins to see that he is a

member of the Order of Industry, which ought to be the frankest, boldest,

most self-reliant of all "Orders." The Order of Thinkers are

pioneers—the Order of Workmen are conquerors. They subjugate Nature

and turn the dreams of thought into realities of life. Why, then,

should not a workman always think and speak with evident consciousness of

the dignity of his own order, and as one careful for its reputation?

It is absurd to see the sovereign people with a perpetual handkerchief at

its eyes, and a constant hat in its hands. The sovereign people

should neither whine nor beg. A workman having English blood in his

veins should have some dignity in his manner. More is expected from

him than from the manacled negro, who could only put up his hands and cry,

"Am I not a man and a brother?" The English artisan ought to be a

man whether a "brother or not." I hate the people who wail.

Either their lot is not improvable, or it is. If it be not

improvable, wailing is weakness: if it be improvable, wailing is

cowardice.

When I first entered the social agitation long years ago,

competition was a chopping-machine and the poor were always under the

knife. If an employer had a reasonable regard for the welfare of the

operatives engaged by him, his manner was hard (as still is the manner of

many), and never indicated good feeling. He lacked that sympathy the

want of which the late justice Talfourd said, was the great defect of the

master class in England. The master at best seemed to regard his men

as a flock of wayward sheep, and himself as a sheep-dog. He indeed

kept the wolf from their door, but they were not sensible of the service,

because he bit them when they turned aside. Owing to this cause

creditable kindness when displayed was not discerned. At no time in

my youth do I remember to have heard any expression which indicated esteem

on the part of the employed towards their employers; and when I listened

to the conversation of workmen in foundries and factories in the same

town, or to that of workmen who came from distant places, it appeared that

this state of feeling was general. The men regarded their masters as

commercial weasels who slept with one eye open, in order to see whether

they neglected their work. Employers looked upon their men as clocks

which would not go, or which if they did were right only once in

twenty-four hours; and that not through any virtue of their own, but

because the right time came round to them.

Employers now, as a rule, have more friendliness of manner.

Factory legislation has done much to improve the comfort of workshops and

limit the labour of children and women. Farm legislation will come,

and do something to the same effect for agricultural working people.

Besides these, consideration, taste, and pride in employers have done

more. The warehouses of great towns are less hideous to look upon by

the townspeople and less dreary to work in. Workshops are in many

places opulent and lofty, and are palaces of labour compared with the

penitentiary structures, which deformed the streets and high-roads

generations ago. The old charnel houses of industry are being

everywhere superseded. Light, air, some grim kind of grace, make the

workman's days healthier and pleasanter; and conveniences for his comfort

and even education, never thought of formerly, are often supplied now.

The stores and mills erected by co-operators show that they have set their

faces against the architects of ugliness, and the new standard can never

go back among employers of greater pretensions.

Under the self-supporting example of the common people the

better classes may be expected to improve. The working class will be

no more told to look to frugality alone as their means of competence.

"Frugality" is oft the fair-sounding term in which the counsel of

privation is disguised to the poor. We shall see the opulent advised

to practise the wholesome virtue of frugality (good for all conditions).

They might then live on much less than they now expend. There then

would remain an immense surplus, available for the public service, since

the provident wealthy would not want it. Advice cannot much longer

be given to the people which is never taken by those who offer it, and

which is intended to reconcile the many to an indefensible and unnecessary

inequality.

The unrest of competition produces disastrous consequences in

diseases which strike down the most energetic men by day and night,

without warning. Some quieter method of progress will be wished for

and be welcomed. In the old times when none could read, save the

priest and a few peers, learning was a passion, and the thoughtful monk,

who had no worldly care or want, toiled in his cell from the pure love of

study, and carried on the thought of the world as Bruno did, with no spur,

save that supplied by genius and the love of truth. Now the printing-press

has called into activity the intellect of mankind—ambition and emulation,

industry and discovery, invention and art, will proceed by the natural

force of thought, however Co-operation may prevail. Indeed,

Co-operation may facilitate them. If Peace hath her victories as

well as War—which a poet was first to see—concert in life has its million

devices, activities, and inspirations. The world will not be mute,

nor men idle, because the brutal goad of competition no longer pricks them

on to activity. The future will not be less brilliant than the past,

because its background is contentment instead of misery.

People who say that the world would come to a standstill were

it not for the pressure of hunger and poverty, and that we should all be

idle were we not judiciously starved, should spend five minutes in the

study of the ceaseless, joyous, and gratuitous activity of the first Lord

Lytton. Of high lineage, of good fortune, of capacity which

understood life without effort, occupying a position which commanded

deference, and of personal qualities which secured him friends, he had

only to live to be distinguished, yet this man, as baronet and peer,

worked as many hours of his own will as any mechanic in the land, and of

his own natural love of activity created for the world more pleasant

reading than all the House of Lords put together, save Macaulay.

The present casts its light of change some distance before,

and the near future can be discerned—Co-operation bids fair to clear the

sight of the industrial class as to what they can do for themselves.

Men as a rule have not half the brains of bees. Bees

respect only those who contribute to the common store, they keep no terms

with drones, but drag them out and make short work with them. Men

suffer the drones to become kings of the hive, and pay them homage.

Co-operators of the earliest type set their faces against uselessness.

With all their sentimentality they kept no place for drones. They

did not mean to be mendicants themselves nor to have mendicants in their

ranks. They had no plan either of indoor or outdoor relief for them.

The first number of the Co-operative Magazine for 1826 made its

first condition of happiness to consist in "occupation." Avoidable

dependence will come to be deemed ignominious. As wild beasts

retreat before the march of civilisation, so pauperism will retreat before

the march of co-operative industry. Pauperism will be put down as

the infamy of industry. A million paupers—a vast standing army of

mendicants—in the midst of the working class is a reproach to every

workman now. Workmen will learn to clear their way, and pay their

way, as the middle-class have learned to do. Every law which

deprives industry of a fair chance, or facilitates the accumulation of

immense fortunes, and checks the equitable distribution of property, will

be stopped, as far as legitimate legislation can stop it. Not long

since a politician so experienced as Louis Blanc made a great speech in

Paris, in which he said, "Most frankly he admitted that the problem of the

extinction of pauperism, which he believed possible, was too vast and

complicated to be treated without modesty and prudence, and he would even

add, doubt." In our English Parliament I have heard ministers use

similar language, without seeming aware that no legislature would

extinguish pauperism if it could. If the proposal was seriously

made, on every bench in the House of Commons, peer and squire and

manufacturer would jump up in dismay and apprehension. The sudden

"extinction of pauperism" would produce consternation in town and county

throughout the land. Were there no paupers there would be no poor.

Nobody would be dependent, service of the humble kind that now ministers

to ostentatious opulence would cease. The pride, power, and

influence that comes from almsgiving would end. In England, as in

America, the "servant" would disappear and in his place would arise a new

class, limited and costly, who would only engage themselves as "helpers"

and equals. Besides, there would be in Great Britain opposition

among the paupers themselves. The majority of them do not want to be

abolished. They have been reared under the impression that they have

a vested interest in charity—humiliation sits easy upon them. It is

not Acts of Parliament that can do much to alter this, it is the means of

self-help which alone can bring it to pass.

At a public meeting in the metropolis, some years ago, Prince

Albert was one of the speakers, and he was on the occasion surrounded by

many noblemen. The subject of his speech was improvement in the

condition of the indigent. The Prince, looking around him at the

wealthy lords on the platform, and to some poor men in the meeting, said,

very gracefully, "We," looking again at a duke near him, "to whom

Providence has given rank, wealth, and education, ought to do what lies in

our power for the less fortunate." This was very generous of the

Prince, but men look now for a surer deliverance. Providence was not

the benefactor of princes and dukes. He gave them no possessions.

They got them in a very different way. The wealth of nature is given

to all, not to the few, and Co-operation furnishes means of attaining it

to all who have honesty, sense, and unity.

Nothing is more astounding to students of industrial progress

than to observe among commercial men and politicians the utter absence of

any idea of distribution of gains among the people. The only concern

is that the capitalist or the individual dealer shall profit. It is

nobody's concern that the community should profit. It is nobody's

idea that everybody should profit by what man's genius creates. It

does not enter into any mind that disproportionate wealth is an aggressive

accumulation of means in the hands of a few which ought to be, as far as

possible, diffusible in equity among all for mutual protection. The

feudalism of capital is as dangerous as that of arms.

It was stated by the editor of the Co-operative Magazine

in 1826, in very explicit terms, that "Mr. Owen does not propose that the

rich should give up their property to the poor; but that the poor should

be placed in such a situation as would enable them to create new wealth

for themselves." [282] This is

what Co-operation is intended to do, and this, let us hope, it will do.

The instinct of Co-operation is self-help. Only men of

independent spirit are attracted by it. The intention of the

co-operator has been never to depend upon parliamentary consideration for

help, nor upon the sympathy of the rich for charity, nor upon pity nor the

prayer of the priest. The co-operator may be a believer, and

generally is, but he is self reliant in the first place, and a believer in

the second. Pity is out of his way, because he does not like to

distress people to give it. Help by prayer is the most compendious

and easy way of getting it, but the co-operator, who is generally a modest

man, does not like to give the priest the trouble of procuring it, whose

machinery seems never in order when it is most wanted to work. When

the working class have learnt the lesson of self-support and

self-protection there may be piety and devotion and the love of God among

them, but they will owe their fortunes to themselves. Co-operators

know, however excellent faith may be, it is not business. No trades

union can obtain an increase of wages by faith. No employer will

give a man a good engagement in consideration of what he believes.

His chances entirely depend on what he can do. The most celebrated

manufacturing firm would be ruined in repute if the twelve apostles worked

for it, unless they knew their business. Piety, ever so conspicuous,

fetches no price in the labour market. There is no creed the

profession of which will induce a Chancellor of the Exchequer to remit the

assessed taxes, or a magistrate to excuse the non-payment of local rates.

People have been misled by the well-intentioned but mischievous lesson

which has taught them to employ mendicant supplication to Heaven.

When the evil day comes—when the parent has no means of supporting his

family or discharging his duty as a citizen—the Churches render no help,

the State admits of no excuse: it accords nothing but the contemptuous

charity of the poor law. The day of self-help has come, and this

will be the complexion of the future.

Co-operation, in imparting the power of self-help, abates

that distrust which has kept the people down. Above all projects of

our day co-operative industry has mitigated the wholesale suspicion of

riches and capitalists. This means good understanding in the future

between those who have saved money, and the many who need to save it, and

mean to save it. The old imbecility of poverty is disappearing.

The incapacitating objection to paying interest for money is scarcely

visible anywhere. What does it matter how rich another grows,

whether he be capitalist or employer, whether he be called master or

millionaire, providing he who is poor can contrive to attain competence by

his own aid? Jealousy or distrust of another's success is only

justifiable when he bars the way to those below him, equally entitled to a

reasonable chance of rising. War upon the rich is only lawful when,

not content with their own good fortune, they close every door upon the

poor, give no heed to their just claims, deny them, whether by law or

combination, fair means of self-help, discouraging the honest, the

industrious, and the thrifty from ascending the ladder of prosperity on

which they have mounted. Property has no rights in equity when it

owns no obligation of justice, and ceases to be considerate to others.

If the wealthy proposed to kill the indigent, they would provoke a war in

which the slain would not be all on one side; and since the powerful must

consent to the weak existing, that consent implies the right of the weak

to live, and the right to live includes the right to a certain share of

the wealth of the community, proportionate to the labour and skill they

contribute in creating it. Property has to provide for this or must

permit it to be provided by others, or it will be itself in jeopardy.

The power of creating a pacifying distribution of means is afforded by

practical Co-operation. As I have said, it asks no aid from the

State; it petitions for no gift, disturbs no interests, attacks nobody's

fortune, attempts no confiscation of existing gains, but clears its own

ground, gathers in its own harvest, distributes the golden grain equitably

among all the husbandmen. Without needing favours or incurring

obligations, it establishes the industrious classes among the possessors

of the fruits of the earth. As the power of self-existence in nature

includes all other attributes, so self-help in the people includes all the

conditions of progress. Co-operation is organised self-help—that is

what the complexion of the future will be.

CHAPTER XXXIX.

AN OUTSIDE CHAPTER

Reply to "Fraser's Magazine."—The only notice of my first volume

to which I desire to reply is one which Professor Newman did me the honour

to make in Fraser. [283]

Mr. Newman was alike incapable of being unfair or unjust, and to me he had

been neither, but he had misconceived what I had said about State

Socialism and capitalists. I blame no one who misconceives my

word—I blame myself. It is the duty of a writer to be so clear that

obtuseness cannot misapprehend him nor malice pervert what he says. Mr.

Newman was neither obtuse nor malicious. Few men saw so clearly as he into

social questions, or were so considerate as he in his objections. He

scrupulously said I had, "unawares" and "inconsistently" with my known

views, fallen into errors. Mr. Newman did me the honour to remember that I

try with what capacity I have not to be foolish, and that I regard

unfairness and even inaccuracy of statement as of the nature of a crime

against truth.

I quoted the edict of Babeuf (p. 25, vol. i.), "That they do nothing for

the country who do not serve it by some useful occupation," to show that

the most

extreme communists kept no terms either with "laziness or plunder"—the

two sins usually charged against these theorists. From this Mr. Newman

concluded that I would deny persons the right to enjoy inherited property. Writers on property are accustomed to enumerate but three ways of

acquiring

it—namely, to earn it, to beg it, or to steal it. Mr. Newman's sagacity

enabled him to point out a fourth way—persons may inherit it. I confess

this did not occur to me, nor did I ask myself whether Babeuf thought of

it. I took his edict to apply only to persons for

whose welfare the State made itself responsible. It was in this sense only

that I thought it right that all should be "usefully occupied."

Mr. Newman said, "I would fain pass off" Mr. Owen's administration of the

New Lanark Mills "as Co-operation." Surely I would not. Mr. Newman said,

"Mr.

Owen patronised the workman." Certainly—that is exactly what he

did, and this is what I do not like. It was at best but a good sort of

despotism, and had the merit of being better than the

bad sort. He proved that equity, though paternally conceded, paid, which

no manufacturer had made publicly clear before.

One who has not written on this subject, Mr. John Bright, but who is as

famous for his familiarity with it, as for his readiness in repartee, said

to me, "There is one thing in your book

to which I object—you speak of the tyranny of capital."

"But it was not in my mind," I rejoined. "But it is in your

book," was the answer. No reply could be more conclusive. Capital may be

put to tyrannical uses; but capital itself is the

independent, passionless means of all material progress. It is only its

misuse against which we have to provide, and I ought to have been careful

to have

said so.

For State Socialism I have less than sympathy, I have dislike. Lassalle

and Marx, of the same race, Comte and Napoleon III. are all identifiable

by one

sign—they ridicule the dwarfish efforts of the slaves of wages to

transform capitalistic society. Like the Emperor of the French, they

overflow with what

seems eloquent sympathy for helpless workmen ground to powder in the mill

of capital. They all mean that the State will grind them in a more

benevolent

way of its own, if working men will abjure politics, and submit themselves

to the paternal operators who alone know what is best for them.

There was a German Disraeli—namely, Prince Bismarck—who befriended the

German Jew as Lord Derby did the English one. It was Ferdinand Lassalle,

handsome, unscrupulous, a dandy with boundless bounce; a Sybarite in his

life, beaming in velvet, jewellery, and curly hair, who affected to be the

friend of the working class. Deserting the party to

which he belonged for not appreciating him, he turned against it, and

conceived the idea of organising German workmen as a political force to

oppose the

middle class, exactly as the Chartists were used in England. Lassalle's

language to the working men was that "they could not benefit themselves by

frugality or saving—the cruel, brazen law of wages made individual

exertion unavailing—their only trust was in State help." With all who

disliked exertion Lassalle was popular; for there were German jingoes in his day. By dress

and parade he kept himself distinguished, and also obtained an annuity

from a

Countess who much exceeded his age. The author of "Vivian Grey" was

distanced by Lassalle, who told the world that "he wrote his pamphlets

armed with all the culture of his century." In other respects he showed

less skill than his English rival. Mr. Disraeli insulted O'Connell

whom it was known would not fight a duel, and then challenged his son

Morgan, whom he had not insulted, and who declined to fight until he was. Disraeli prudently did not qualify him. Lassalle, less weary, discerned no

discretionary course, and Count Rackonitz shot him, otherwise Bismarck

would

have been superseded at the Berlin Congress, and a German Beaconsfield had

been President. In blood, religion, and policy, in manners and ambition,

and in success (save in duelling) both men were the same. Our Conservative Lassalle had an incubator of State Socialism for this country and the

Young

England party carne out of it.

Co-operative Methods in 1828.—In 1828, when Lord John Russell was laying

the foundation-stone of the British Schools in Brighton, Dr. King was

writing

to Lord Brougham, then Henry Brougham, M.P., an account of the then new

scheme of Co-operative Stores. It is a practical, well-written

appeal to a statesman, and enables us to see what Brougham had the means

of knowing at that early period of the nature of Co-operation as a new

social force. The following is Dr. King's statement:—

"A number of persons in Brighton, chiefly of the working class, having

read works on the subject of Co-operation, conceived the possibility of

reducing it to

practice in some shape or other. They accordingly formed themselves into a

society,

and met once a week for reading and conversation on the subject; they also

began a weekly subscription of 1d. The numbers who joined were

considerable—at one time upwards of 170; but, as happens in such cases,

many were lukewarm and indifferent, and the numbers fluctuated. Those who

remained showed at once an evident improvement of their minds. When the

subscriptions amounted to £5 the sum was invested in groceries, which

were retailed to the members. Business kept increasing, the first week the

amount sold was half-a-crown; it is now about £38. The profit is about 10

per cent.; so that a return of £20 a week pays all expenses, besides which

the members have a large room to meet in and work in. About six

months ago the society took a lease of twenty-eight acres of land, about

nine miles from Brighton, which they cultivate as a garden and nursery out

of

their surplus capital. They employ on the garden, out of seventy-five

members, four, and sometimes five men, with their own capital.

They pay the men at the garden 14s. a week, the ordinary rate of wages in

the country being 10s., and of parish labourers 6s. The men are also

allowed rent and vegetables. They take their meals together. One man is

married and his wife is housekeeper.

"The principle of the society is—the value of labour. The operation is by

means of a common capital. An individual capital is an impossibility to

the

workman, but a common capital not. The advantage of the plan is that of

mutual insurance; but there is an advantage beyond, viz., that the

workman will

thus get the whole produce of his labour to himself; and if he chooses to

work harder or longer, he will benefit in proportion. If it is possible

for men

to work for themselves, many advantages will arise. The other day they

wanted a certain quantity of land planted before the winter. Thirteen

members went from Brighton early in the morning, gave a day's work,

performed the task, and returned home at night. The man who formerly had

the

land, when he came

to market, allowed himself 10s. to spend. The man who now comes to market

for the society is contented with 1s. extra wages. Thus these men

are in a fair way to accumulate capital enough to find all the members

with constant employment; and of course the capital will not stop there.

Other

societies are springing up. Those at Worthing and Finden are proceeding as

prosperously as ours, only on a smaller scale. If Co-operation be once

proved practicable, the working classes will soon see their interest in

adopting it. If this goes on, it will draw labour from the market, raise

wages, and so

operate upon pauperism and crime. All this is pounds, shillings, and pence; but another most important feature remains. The members see

immediately the value of knowledge. They employ their leisure time in

reading and mutual instruction. They have appointed one of their members

librarian and schoolmaster; he teaches every evening. Even their

discussions involve both practice and theory, and are of a most improving

nature. Their feelings are of an enlarged, liberal, and charitable

description. They have no disputes, and feel towards mankind at

large as brethren. The élite of

the society were members of the Mechanics' Institution, and my pupils, and

their minds were no doubt prepared there for this society. It is a happy

consummation.

"In conclusion, I beg to propose to your great and philanthropic mind the

question as to how such societies may be affected by the present state of

the law; or how far future laws may be so framed as to operate favourably

to them. At the same time, they ask nothing from any one but to be let

alone, and

nothing from the law but protection. As I have had the opportunity of

watching every step of this society, I consider their case proved; but

others at a

distance will want further experience. If the case is proved, I consider

it due to you, sir, as a legislator, philosopher, and the friend of man,

to lay it before

you. This society will afford you additional motives for completing the

Library of Useful Knowledge—the great forerunner of human improvement."

The First Sales of the Rochdale Pioneers.—In 1866, when Mr. Samuel

Ashworth left the Rochdale store to manage the Manchester Wholesale

Society, a

presentation was made to him in the Board Room of the Corn Mill. A

correspondent of the Working Man sent to me at the time these

particulars, not

published save in that journal. In the course of the proceedings Mr.

William Cooper related how he and Samuel Ashworth were among the first

persons

who served customers in

the store in Toad Lane; when it was opened in 1844 for sales of articles

in the grocery business. "We then," said Mr. Cooper,

"sold goods at the

store

about two nights in the week, opening at about eight o'clock p.m., and

closing in two hours after. Mr. Ashworth served in the shop one week, and

I the

week following. We gave our services for the first three months, except

that the committee bought each of us a pair of white sleeves—something

like

butchers wear on their arms, to make us look tidy and clean, and, if the

truth is to be owned, I daresay they were to cover the grease which stuck

to and

shone upon our jacket sleeves as woollen weavers. At that time every

member that worked for the store, whether as secretary, treasurer,

purchaser, or

auditor, did it for the good of the society, without any reward in wages

or salary.

"When Samuel Ashworth joined the society, in 1844, he was only nineteen

years of age. He was behind the counter on December 21, 1844, that

memorable day when the shutters were first taken down from the shop-front

in Toad Lane, and was one of those stared at by every passer-by. The stock

with which the co-operators opened the shop was as follows: 1 qr. 22 lb.

of butter, 2 qrs. of sugar, 3 sacks of flour at 37s. 6d., and 3 sacks at

36s., 2

dozen of candles, and 1 sack of meal. The total cost of this stock was £16 11s. 11d.; and it appeared they must have had a fortnight's stock of

flour, for there was none

bought the second week. The second week the stock was slightly decreased,

the amount of purchases for the fortnight being £24 14s. 7d."

Those goods Samuel Ashworth and William Cooper had the pleasure of selling

as unpaid shopkeepers—"a bad precedent," remarked Mr. Ashworth, in the

course of a speech made by him, "because even now some of their members do

not like to pay their servants the best of wages." It is instructive

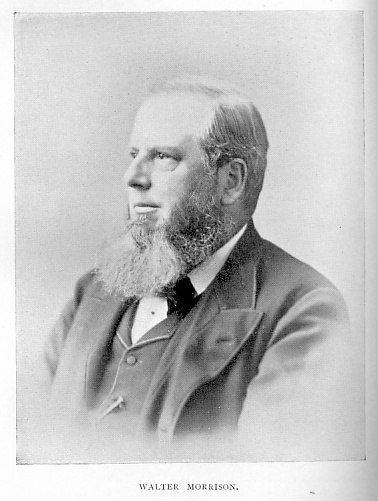

to compare the difference between the weekly sale of goods during the

first fortnight of the society's existence, and their weekly sales twelve

years later:—

|

Weekly Sales in 1844. |

Weekly Sales in 1856. |

|

Butter |

50lb. |

220 firkins, or 15,400lb. |

|

Sugar |

40lb. |

170 cwt., or 19,040lb. |

|

Flour |

3 sacks |

468 sacks. |

|

Soap |

56lb. |

2 tons 13cwt., or 5,936lb. |

Subsequently, when the price of sugar was rapidly rising, Mr. Ashworth

ordered 50 tons of sugar in three days, and on another occasion he gave an

order for 4,000 sacks of flour at once. The weekly receipts during the

first fortnight of the society's operations did not average £10, twelve

years later, in 1866, the weekly sales were £4,822.

The End of the Orbiston Community.—The most interesting and authentic

account of Orbiston, its objects, principles, financial arrangements, and

end, is

that given in the newspapers of 1829 and 1830. The following appeared

under the head of "Law Intelligence—Vice Chancellor's Court"—JONES

v.

MORGAN AND OTHERS—THE

SOCIALISTS.—This case came before the court upon

the demurrer of a lady, named Rathbone, put in to a Bill filed by

several shareholders of the Orbiston Company, on the ground that such

shareholders had contributed more than was justly due from them, and to

recover the excess. The grounds of the demurrers were want

of equity. The case came before the court upon the demurrer

of a person named Cooper. The facts appeared to be these: In the year

1825 a number of persons joined together, for the purpose of forming a

socialist

or communist society, under the superintendence of Mr. Robert Owen, the

professed object of which was to promote the happiness of mankind. The

company was to consist of shareholders, the shares being fixed at £250

(though after the formation of the company they were reduced to £200

each),

and it being further agreed that for the first year no shareholder should

be allowed to hold more than ten shares, but that after the lapse of one

year from

the formation of the society, such stock as should then be unappropriated

might be disposed of among the members of the company. The capital

was not to exceed £50,000. The company eventually purchased 280 acres of

land from General Hamilton, at Orbiston, in Scotland, as the site of the

proposed establishment, for which they consented to pay £19,995. This money

was borrowed in three several sums of £12,000 from the Union Scotch

Assurance Company, £3,000 from a Mr. Ainslie, and the remainder from

another quarter. The articles of agreement were then drawn up. The right

of

voting was to be vested in the shareholders proportionately to

the amount of their respective shares. The necessary buildings were to be

erected, and the necessary utensils supplied, and the company were to be

empowered to borrow money upon the security of the joint property. Several

trustees were named, the first being a Mr. Combe, to whom the estate was

accordingly conveyed. The following are some of the general articles

agreed on: "Whereas the assertion of Robert Owen, who has had much

experience in the education of children, that principles as certain as the

science of mathematics may be applied to the forming any general

character, and

that by the influence of other circumstances not a few individuals only,

but the population of the whole world, may in a few years be rendered a

very far

superior race of beings to any now on the face of the earth, or who have

ever existed, an assertion which implies that at least nine-tenths of the

crime and

misery which exist in the world have been the necessary consequence of

errors in the present system of instruction, and not of imperfection

implanted in

our nature by the Creator, and that it is quite practical to form the

minds of all children that are born so that at the age of twelve years

their habits and

ideas shall be far superior to those of the individuals termed learned

men. . . . And that under a proper direction of manual labour Great

Britain and its

dependencies may be made to support an incalculable increase of

population." The 21st article provided for a dissolution of the society if

it should be

found necessary: "That if, unhappily, experience should demonstrate to the

satisfaction of the majority of proprietors that the new system introduced

and

recommended by R. Owen has a tendency to produce, in the aggregate, as

much ignorance in the midst of knowledge, as much poverty in the midst of

excessive wealth, as much illiberality and hypocrisy, as much overbearing

and cruelty, and fawning and severity, as much ignorant conceit, as much

dissipation and debauchery, as much filthiness and brutality, as much

avarice and unfeeling selfishness, as much fraud and dishonesty, as much

discord

and violence, as have invariably attended the existing system in all ages,

then shall the property be let to individuals acting under the old system,

or sold to

defray the expenses of the institution." In 1825 the society entered upon

the estate, and the lands were divided among the tenants. Among the original shareholders was the present demurring defendant,