|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER XIII.

FORGOTTEN WORKERS

|

"By my

hearth I keep a sacred nook

For gnomes and dwarfs, duck-footed waddling elves

Who stitched and hammered for the weary man

In days of old. And in that piety

I clothe ungainly forms inherited

From toiling generations, daily bent

At desk, or plough, or loom, or in the mine,

In pioneering labours for the word."

GEORGE ELIOT,

A Minor Prophet. |

THE Pioneer Period in every great movement best

displays the aims, the generosity of service, the impulse of passion, the

mistakes of policy, the quality and force of character, of leaders and

followers. Any one conversant with struggling movements knows that

most of the errors which arose were due to the actors never having been

told of the nature and responsibilities of their enterprise. Ten men

err from pure ignorance where one errs from wilfulness or incapacity.

How often I have heard others exclaim, how often have I exclaimed myself,

when a foolish thing had been said, or a wrong thing had been done, why

did not some one who had had this experience before tell us of this?

Co-operators who master and hold fast openly, and always, to a policy of

truth, toleration, relevance, and equity, succeed.

The unremembered workers described in the words of the

poetess, placed at the head of this chapter, have abounded in the social

movement. Less fortunate than the religious devotee, who sailed more

or less with the popular current, the social innovator has few friends.

Rulers distrusted him. His pursuit of secular good, caused him to be

ill-spoken of by spiritual authorities, and he had no motive to inspire

him save the desire or doing good to others. Too much is not to be

made of those who die in discharge of well-understood duty. In daily

life numerous persons run risks of a like nature, and sometimes perish in

the public service. To know how to estimate those who stand true we

must take into sight those who never stand at all—who, the moment loss or

peril is foreseen, crawl away like vermin into holes of security.

These are the rabbit-minded reformers, who flee at the first sound of

danger, or wait to see a thing succeed before they join it. Those

who flee a struggling cause are a great army compared with those who

fight.

Yet the world is not selfish or cold. It is like the

aspects of Nature: large parts are sterile, bleak, inhospitable; yet, even

there, the grandeur of view and majestic grimness delight the strong.

In other parts of physical Nature—warmth, light, foliage, flowers, make

glad and gay the imagination. So in society—strong, tender, wise

men will give discriminating aid to strugglers below them; strugglers,

indeed, perish unhelped, oftimes because they are unnoticed, rather than

because of the inhumanity of the prosperous. There are, as

experience too well tells, men who do not want to help others; while there

are more who do not help, simply not knowing how. But there are

others, and it is honest to count them, whom affluence does not make

insensible, and who feel for the poor.

The agitation had for leaders many disinterested gentlemen

who not only meant what they said in sympathy, but were prepared to give,

and did give, their fortunes to promote it. There was not a man of

mark among them who expected to, or tried to, make money for himself by

these projects of social improvement. Some, as Abram Combe and

William Thompson, gave not only money but life. Others absolutely divested

themselves of their fortunes in the cause. They indeed believed that they

were founding a system of general competence, and that such share as was

secured to others would accrue to them; and with this prospect they were

content. Some or them might have retained stately homes and have commanded

deference by the splendour of their lives. And when their disinterested

dream was not realised, their fortune squandered, and disappointment, and

even penury overtook them, as happened in some cases, they never regretted

the part they had taken, and died predicting that others would come after

them, who, wiser and more fortunate than they, would attain to the success

denied to them. Gentlemen connected with Co-operation were not wanting in

the spirit of self-sacrifice, who died, like Mr. Cowell Stepney, of caring

for everybody's interest but their own. [118]

This is not at all a common disease in any class, and takes very few

people off. Yet few are remembered with the reverence accorded to

those who die these deaths. Were their services understood they

would receive honour exceeding that of those greeted by—

"The patched and plodding citizen,

Waiting upon the pavement with the throng,

While some victorious world-hero makes

Triumphant entry; and the peal of shouts. . .

Run like a storm of joy along the streets!

He says, 'God bless him!' . . .

As the great hero passes. . . .

Perhaps the hero's deeds have helped to bring

A time when every honest citizen

Shall wear a coat unpatched." [119] |

Ignoring certain noisy adherents, who infest every movement, whose

policy is conspicuousness, and whose principle is "what they can get";

who seek

only to serve themselves, never, except by accident, serving anybody else; who clutch at every advantage, without giving one grateful thought, or

even

respectful word, to those who have created the advantage they enjoy—my

concern is not for these adherents, whose very souls are shabby, and who

would bring salvation itself into

discredit were it extended to them. My last care is for the honest,

unobtrusive workers, who drudged, without ceasing, in the "cause" who

devoted the

day of rest to correspondence

with unknown inquirers. The just-minded took the services with gratitude;

the selfish took them as their right, never

asking at what cost it was accorded. Knowing that self-help meant

self-thinking, and that no deliverance would come if the people left it to

others to think

for them—these advocates counted it a first duty to awaken in their

fellows the inspiration of self-action. But in thus making themselves so

far the

Providence of others, the most generous of them had no time

left to be a Providence to themselves. But it is not for us to forget the

self-forgetting, whose convictions were obligations, and whose duty was

determined

by the needs of others. During the ninety years over which this history

travels there have been humble compeers who drudged in stores during what

hours

fell to them after their day's work was done. They travelled from street

to street, or from village to village, on Sundays, to collect the pence

which started

the stores. They gave more than they could afford to support periodicals,

which never paid their conductors, for the chance of useful information

thus

reaching others. For themselves, they reaped in after-days dismay and

disregard at their own fireside, for their disinterested and too ardent

preference of

others' interests. Many gave their nights to the needful, but monotonous

duties of committees, and to speaking at meetings at which few attended,

returning late and weary to cheerless rooms. Some were worn out

prematurely, and died unattended in obscure lodgings. Some lingered out

their

uncheered days on the precarious aid occasionally sent them by those who

happened to remember that they were benefiting by the peril which had

brought the old propagandists low. Not a few of them, after speeches of

fiery protest on behalf of independence, in political movements to which

they

were also attracted, spent months and years in the indignity of prison,

and at last died on a poorhouse bed, and were laid in a pauper's grave. [120] I

have met

their names in struggling periodicals advocating social an political

progress. Many of them were my comrades. Foreseeing their fate, I often

tried to

mitigate their devotion. I stood later by the dying bed of some of them,

and spoke at the burial of many. They lie in unremembered graves. But there

was

inspiration in their career which has quickened the

pulses of industry. Though the distant footfall of the coming triumph of

their order never reached their ear, they believed not less in its march.

PART II.

THE CONSTRUCTIVE PERIOD

1845-1878

CHAPTER XIV.

THE STORY OF A DEAD MOVEMENT

"A new mind is first infused into society;. . . . Is breathed from individual

to individual, from family to family—it traverses districts—and new men,

unknown to

each other, arise in different parts. . . . At last a word is spoken which

appeals to the hearts of all—each answers simultaneously to the call—a

compact

body is collected under one standard, a watchword is given, and every man

knows his friend."—THE FIRST LORD LYTTON.

MOVEMENTS, like men, die—some a natural, some a violent, death. Some

movements perish of intellectual rickets, from lack of vitality; or,

falling into

blind hands, never see their opportunities. It is true of movements as of

men—those who act and do not think, and those who think and do not act

alike

require an early coffin. In days of social storm, insurrection,

revolution, every word of counsellors entitled to be heard has

significance. Change is

but a silent storm, ever beating, ever warning men to provide for it, and

they who stand still are swept away. But movements do not often die

in their beds—they are assassinated in the streets. Error, fed upon

ignorance, and inspired by spite, is commonly strong and unscrupulous. Truth

must fight to live. There is no marching on without going forward and

confronting the enemy. Those who know the country and are resolute, may

occupy more of it than they foresee. It is a delusion to think

that pioneers have all the ground to clear. Men's heads are

mostly vacant, and not a few are entirely empty. In more cases than are

imagined there is a brain-hunger for ideas. Co-operation, after thirty

years of valorous vicissitude, died, or seemed to die, in 1844-45.

The busy, aspiring movement of Co-operation, so long chequered by ardour

and despondency, was rapidly subsiding

into silence and decay. The little armies on the once militant plain had

been one after another defeated and disbanded. The standards, which had been carried defiantly with some daring

acclaim, had fallen one by one; and in many cases the standard-bearers had

fallen with them, For a few years to come no movement is anywhere

observable, Hardly a solitary insurgent is discernible in any part of the

once animated

horizon. The sun of industrial hope, which

kept so many towns aglow, has now gone down. The very air is bleak. The

Northern Star, [121] lurid and glaring (which arose in Leeds, to guide the

Political

Pioneers of Lancashire

and Yorkshire), is becoming dim. The Star in the East promising to

indicate that among the managers of Wisbech a a new deliverer [122] has come,

has dropped out of the firmament. The hum of the Working Bee

is no more heard in the fens

of Cambridgeshire. The Morning Star—that appeared at Ham Common, shining

upon a dietary of vegetables and milk—has fallen out of sight. [123]

"Journals" are kept no more—"Calendars" no longer have dates filled

in—"Co-operative Miscellanies" have ceased—"Mirrors" fail to

reflect the faces of the Pioneers—The Radical has torn up its

roots—The Commonweal

has no one to care for it—believers in the New Age are extinct—The

Shepherd

is gathering his eccentric flocks into a new fold [124]—readers of the

Associate have discontinued to assemble together—"Monthly

Magazines" forget to come out—"Gazettes" are empty "Heralds" no more go

forth—"Beacons" find that the day of warning is over—the Pioneer has

fallen in

the last expedition of the forlorn hope which he led—there is nothing

further to "Register," and the New Moral World is about to be sold by

auction—Samuel

Bower has eaten all his peas—Mr. Etzler has carried his wondrous machines

of Paradise to Venezuela—Joseph Smith has replaced his wig—Mr. Baume

has sold his monkey—and the Frenchman's Island, where infants were to be

suckled by machinery, has not inappropriately become the site of the

Pentonville Penitentiary. The "Association of All Classes of All Nations"

has not a member left upon its books. Of the seventy thousand Chartist

land-dreamers, who had been actually enrolled, nothing is to remain in the

public mind save the memory of Snigg's End! Labour Exchanges have

become bywords—the Indiana community is as silent as the waters of the

Wabash by its side—Orbiston is buried in the grave of Abram

Combe—Ralahine

has been gambled away—the Concordia is a strawberry garden—Manea Fen has

sunk out of sight—the President of Queenwood is encamping in the lanes—the blasts of the "Heralds of

Community" have died in the air—the notes of the "Trumpet Calls"

have long been still, and the trumpeters

themselves are dead. It may be said, as the Lord of the Manor of Rochdale

[125] wrote of a more historic

desolation:—

|

"The tents are all silent, the banners alone,

The lances unlifted, the trumpets unblown." |

Time, defamation, losses, distrust, dismay, appear to have doe their work.

Never human movement seemed so very dead as this of Co-operation. Its lands

were all sold, its script had no more value, its orators no more hearers. Not

a pulse could be felt throughout its whole frame, not a breath could be

discerned on

any enthusiastic mirror held to its mouth. The most scientific punctures

in its body failed to elicit any sign of vitality. Even Dr. Richardson would

have

pronounced it a case of pectoral death. [126] I felt its cold and

rigid hand in

Glasgow—the last "Social Missionary" station which existed. Though

experienced in the pathology of dead movements, the case seemed to me

suspicious of decease. Wise Americans came over to look at it, and

declared with

a

shrug that it was a "gone coon." Social physicians pronounced life quite

extinct. Political economists avowed the

creature had never lived. The newspapers, more observant of

thought it would never recover, which implied that, in their opinion, it had

been alive. The clergy, content that "Socialism" was reported to be gone,

furnished

with delighted alacrity uncomfortable epitaphs for its tombstone.

Yet all the while the vital spark was there. Efforts beyond its strength

had brought upon it suspended animation. The first sign of latent life was

discovered in Rochdale. In the meantime the great comatose movement lay

stretched, out of the world's view, but not abandoned by a few devoted

Utopians,

who had crept from under the slain. Old friends administered

to it, familiar faces bent over it. For unnoted years it found voice in

the Reasoner, which said of it one thing always—"If it

be right it can be revived by devotion. Truth never dies except

it be deserted." Then a great consultation arose among the social medicine

men. The regular physicians of the party, who held official or missionary

diplomas, were called in. The licentiates of the platform also attended. The subscribing members of the Community Society, the pharmaceutists

of Co-operation, were at hand. They were the chemists and druggists of the

movement, who compounded the recipes of the social doctors, when

new prescriptions were given out. Opinions were given by the learned

advisers, as the symptoms of the patient seemed to warrant them. As in

graver consultations, some of the prescriptions were made rather with a view of

differing from a learned brother than of saving the patient. The only

thing

in which the faculty present in this case agreed was, that nobody proposed

to bleed the invalid. There was clearly no blood to be got out of him. The

first opinion pronounced was that mischief had arisen through want of

orthodoxy in Communism. It was thought that if it was vaccinated, by a

clergyman of

some standing, with the Thirty-nine Articles, it might get about again;

and Mr. Minter Morgan produced a new design of a parallelogram with a

church in it. It was shown to Mr. Hughes. Some Scotch doctors advised the

Assembly's "Shorter Catechisms." A missionary, who had been a

Methodist, thought that an infusion of Wesleyan fervour and faith might

help it. A Swedenborgian said he knew the remedy, when "Shepherd"

Smith [127]

persisted that the doctrine of Analogies would set the

thing right. Then the regular faculty gave their opinions. Mr. Ironside

attested with metallic voice that recovery was possible. Its condition was so weak

that,

Pater Oldham [128]—with a beard as white and long as Merlin's—prescribed for it celibacy and

a vegetarian diet. Charles Lane raised the question, should it be

"stimulated with

milk"? which did

not seem likely to induce in it any premature action. James Pierrepont

Greaves suggested that its "inner life" should be nurtured on a

preparation of

Principles of Being, of which he was sole proprietor. Mr. Galpin, with patriarchal stateliness,

administered to it grave counsel. Thomas Whittaker presented a register of

its

provincial pulsations, which he said had

never ceased. Mr. Craig suggested fresh air, and if he meant commercial

air there was need of it. George Simpson, its best financial secretary,

advised it neither to give credit nor

take it, if it hoped to hold its own. Dr. John Watts prescribed it a

business dietary, flavoured with political economy, which was afterwards

found to

strengthen it. John Colier Farn, who had the Chartist nature, said it

wanted robust agitation. Alexander Campbell, with Scotch pertinacity,

persisted that

it would get round with a little more lecturing. Dr. Travis thought its

recovery certain, as soon as it comprehended the

Self-determining power of the will. Charles Southwell chafed at the

timorous retractations of some of his colleagues, avowed that the

imprisonment of

some of them would do the movement good. William Chilton believed that

persecution alone would reanimate it, and bravely volunteered to stand by

the cause in case it occurred. Maltus Questell Ryall, generously indignant

at the imprisonment of certain of his friends, spoke as Gibbon was said

to have written—"as though Christianity had done him a personal injury"—predicted that Socialism would be itself again if it took courage and

looked its

clerical

enemies square in the face. Mr. Allsop, always for boldness,

counselled it to adopt Strafford's motto of "Thorough." George Alexander

Fleming surmised that its proper remedy was better obedience to the Central Board. James Rigby

tried to awaken its attention by spreading before its eyes romantic

Pictures of Communistic life, Lloyd Jones admonished it, in

sonorous tones, to have more faith in associative duty. Henry

Hetherington, whose honest voice sounded like a principle advocated a

stout publicity of

its views. James Watson, who shook hands, like a Lancashire man, from the

shoulder, with a fervour which you would have cause to remember all the

day after, grasped the sinking cause by the hand, [129] and imparted

some feeling to it. Mr. Owen, who never doubted its vitality regarded the

moribund movement with complacency, as being

in a mere millennial trance. Harriet Martineau brought it gracious news

from America of the success of votaries out

there, which revived it considerably. John Stuart Mill inspired it with

hope, by declaring that there was no reason in political economy why any

self-helping movement of the people should

die. Mr. Ashurst looked on with his wise and kindly eyes, to see that

recovery was not made impossible by new administrative error. But none of the physicians had restored it, if the sagacious

men of Rochdale had not discovered the method of feeding it on

profits—the most

nutritious diet known to social philosophy—which, administered in

successive and ever-in- creasing quantities, gradually restored the

circulation of the

comatose body, opened its eyes, and set it up alive again, with a capacity

of growth which the world never expected to see it display.

It was not until a new generation arose that co-operative enthusiasm was

seen again. The Socialists were not cowards in commerce. They could all

take care of themselves in competition as well as their neighbours. The

police in every town knew them as the best disposed of the artisan class.

Employers knew them as the best workmen. Tradesmen knew them as men of

business, of disquieting ability. These societarian improvers

disliked the conspiracy against their neighbours which competition

compelled them to engage in, and they were anxious to find some means of

mitigating

it.

Of two parties to one undertaking, the smaller number, the capitalists,

are able to retain profits sufficient for affluence, while the larger

number, the

workers, receive a share which, by no parsimony or self-denial, can secure

them competence. No insurrection can remedy the evil. No

sooner shall the bloody field be still than the sane system will reproduce

the same inequalities. But a better course is by producers giving security

and

interest for capital, and dividing the profits earned among themselves, a

new distribution of wealth is obtained which accords capital equitable

compensation,

and secures labour enduring provision. Thus he advocates of the new form

of industry by concert tried to combat competition by co-operation.

The Concordium had a poet, James Elmslie Duncan, a young enthusiast, who

published a Morning Star in Whitechapel, where here it was much

needed. The most remarkable specimen of his genius, I remember, was

his epigram on a draped statue of of Venus—

|

"Judge, ye gods, of my surprise,

A lady naked in her chemise!" |

We had poets in those days unknown to Mr. Swinburne or Sir Lewis Morris.

The Ham Common Concordium fell as well as Harmony Hall. The Concordium

represented celibacy, mysticism, and long beards. One night, I and Maltus

Questell Ryall walked from London to visit it. We found it by observing a

tall patriarch's feet projecting through the window. It was a device of

the

Concordium to ensure ventilation and early rising. By a bastinado of the

soles of the prophet with pebbles, we obtained admission in the early

morning.

Salt, sugar, and tea were alike prohibited; and my wife, who wished salt

with the raw cabbage supplied at breakfast, was allowed to have it, on the

motion

of Mr. Stolzmeyer, the agent of Etzler's "Paradise within the Reach of all

Men." When the salt was conceded it was concealed in paper under the plate,

lest the sight of it should deprave the weaker brethren. On Sundays many

visitors came, but the entertainment was slender. On my advice they

turned two

fields into a strawberry garden, and for a charge of ninepence each,

visitors gathered and ate all they could. This prevented them being able

to eat much at

other meals, for which they paid—and thus the Concordium made money.

CHAPTER XV.

BEGINNING OF CONSTRUCTIVE CO-OPERATION

|

None from his fellow starts,

But playing manly parts,

And, like true English hearts,

Stick close together.

DRAYTON. |

THOSE who sleep on the banks of the Thames, near Temple Bar, as I did

several years, hear in the silence of the night a slow, intermittent

contest of

clocks. Bow Bells come pealing up the river; St. Dunstan, St. Clement,

St. Martin, return the answering clangour. Between the chiming and the

striking there suddenly bursts out the sonorous booming off Big Ben from

the Parliament clock tower, easily commanding attention in the small

Babel of

riverside tinklings, and the wakeful hearer can count with certainty the

hour from him. To me Rochdale was in one sense the Big Ben of Co-operation,

whose sound will long be heard in history over that of many other stores. For half a century Co-operation was audible on the banks of the Humber,

the

Thames, and the Tyne; but when the great peal finally arose from the banks

of the Roche, Lancashire and Yorkshire heard it. Scotland lent it a

curious

and suspicious ear. Its reverberations travelled to France, Italy,

Germany, Russia, and America, and even at the Antipodes settlers in

Australia caught its

far-travelling

tones, and were inspired by it. The men of Rochdale had

the very work of Sisyphus before them. The stone of Co-operation had

often been rolled up the hill elsewhere, and often rolled down again. Sometimes it

was being dragged up by credit, when, that rope breaking, the reluctant

bell

slipped into a bog of debt.

At length some enthusiasts gave another turn, when some watchful rascal

made away with its profits, which had acted as a wedge, steadying the

weight

on the hill, and the law being on the side of the thief, let the great

boulder roll back. Another set of devotees gave a turn at the great

boulder, but having

theological questions on hand, they fell into discussion by the way, as to

whether Adam was or was not the first man; when those who said he was

refused to push with those who said he was not, and Adam was the cause of

another fall in the new Eden, and the co-operative stone found its way

once

more to the bottom.

At length the Rochdale men took the stone in hand. They

invented an interest for everybody in pushing. They stopped

up the debt bogs. They mainly established a Wholesale Supply

Society, and made the provisions better. They got the law amended, and

cleared out the knaves who hung about the till. They planned

employment of their profits in productive manufactures, so that the store and workshop might grow. They proclaimed

toleration to all opinions—religious and heretical

alike—and recognised none. They provided for the education of their

members, so that every man knew what to push for and where to place his

shoulder,

and were the first men who landed the great stone at the top.

When Co-operation recommenced there, Rochdale had no hall which

Co-operators could afford to hire. There was, however, a small,

square-shaped

room, standing in the upper part of Yorkshire Street, opposite to St.

James's Church, and looking from the back windows over a low, damp, marshy

field. It

belonged to Mr. Zach Mellor, the Town Clerk, whose geniality and public

spirit were one of the pleasant attributes of official Rochdale. He was,

happily, long

of opinion that any townsmen, however humble, desirous of improving their

condition by honest means, had as much right as any one else to try. He

treated—as town clerks should with civic impartiality all honest

townsmen, without regard to their social

condition or opinions. Through the personal intervention of Mr. Alderman Livesey, always the advocate of the unfriended, this

place was let to the

adventurous party of

half Chartists and half Socialists who cared for Co-operation. It was in

this small Dutch-looking meeting-house that I first spoke on Co-operation,

in 1843. I well remember the murky

evening when this occurred. It was the end of one of those damp, drizzling

days, when a manufacturing town looks like a

penal settlement. I sat watching the rain and mists in the fields as the

audience assembled—which was a small one. They came in one by one from the mills, looking as damp disconsolate as

their prospects. I see their dull, hopeless faces now. There were a few

with a bustling sort of confidence, as if it

would dissolve if they sat still—who moved from bench to bench to say

something which did not seem very inspiring to those who heard it.

When I came to the desk to speak I felt that neither my subject nor my

audience was a very hopeful one. In those days my notes were far

beyond the requirements of the occasion; and I generally left my hearers

with the impression that I tried to say too much in the time, and that I

spoke of many things without leaving certainty in their minds which was

the most important. The purport of what I said, as far as it had a

purport, was to this effect:—

-I-

Some of you have had experience of Chartist associations, and you have not

done much in that way yet. Some of you have taken trouble to create

what you call Teetotalers, but temperance depends more upon social

condition than exhortation. The hungry will feel low, and the

despairing will drink. You have tried to establish a co-operative

store here and have failed, and are not hopeful of succeeding now.

Still it ought to be tried again, and will not interfere with Chartism; it

will give it more means. It will not interfere with temperance; it

will furnish more motives to sobriety. Many of you believe

Co-operation to be right in principle, and if a thing is right you ought

to go on with it. Cobbett tells you the only way to do a difficult

thing is to begin and stick at it. Anybody can begin it, but it

requires men of a good purpose to stick at it. To collect money from

people, who to all appearance have little, is not a hopeful undertaking.

Somebody must collect small subscriptions until you have a few pounds.

A few rules to act upon, a small room to serve as a sort of shop, and

small articles such as you are most likely to I sell, as good as you can

get them; weigh them out fairly; then a store is begun. There may be

trouble at home; wives prefer going to the old shops, not knowing that

credit is catching and debt is the disease they get. A wife will not

always have money to buy at the store, and will want to go where she can

do so without; you must provide for this, for buying at the store is the

only way to make it grow and yield profit. What you save will be you

own, and your stock will grow, and you will get things as good as your

neighbours, and as cheap as your neighbours. Besides, when you have

a shop as large as that of ten shops, you will save the shop-keeping

expenses of ten shops, and that will make profit which will be shared by

all members. If you want to help the Community in Hampshire, you

will then be able to do it. You may be able to set apart some

portions of your profits for a news-room and little library where members

may spend their evenings, instead of going to the public-house, and save

money that way, as well as get information. This is the way stores

have been begun. Co-operators have been instructed that all men are

different by nature, and come into the world with passions and tendencies

they did not give themselves. Ignorance and adversity make the bad

worse. Noble self-denial, pettiness, and selfishness will mingle in

the same person. Those who understand this are fit for association.

Anger at what you do not like, or what you do not expect, can only proceed

from ignorance taken by surprise. Tolerance and steadfast goodwill

are the chief virtues of association. The rhyme which tells the

young speaker to speak slowly, and emphasis and tone will come of

themselves, has instruction for you if we change a word to express it—

|

"Learn to unite—all other graces

Will follow in their proper places." |

If you do not regard all creeds as being equally true and equally useful,

you will regard them as equally to be respected. In co-operative

associations success is always in the power of those who can agree.

There the members have no enemies who can harm them but themselves; and

when a man has no enemy but himself, he is a fool if he is without a

friend. Pope tells you that—

|

"The devil is wiser now than in the days of yore;

Now he tempts people by making rich, rich, and not by making poor."

|

There is certain consolation in that. He has been with you

on that business. Your difficulties will lie, not in negotiating with

him,

but in stating your case to your neighbours, that

they shall see the good sense of your aims. The main thing you have to

avoid is what the Yankees call "tall statements." We are all agreed that

competition has a disagreeable edge. But if we should be betrayed into

saying that we intend to

abolish it, we go beyond our power. But we can mitigate it. When they open

a store to sell at market prices, opponents will ask you how you will find

out

the market price when

there are no markets left. There are people who would ask the Apostles how

they intended to apply the doctrine of the atonement for sin, when the

millennium arrives and all people

are perfect. Beware of inquirers who are born before their time, and who

spend their lives in putting questions which will not need answering for

centuries to come. If workmen

increase in numbers the tradesman does not like it. It means more poor

rates for him to pay. The gentry do not like it. It means that they

would have to cut you down, if riot should follow famine. The only persons

whom over-population profits are those who hire labour, because numbers

make it

cheap. Your condition is so bad that fever is your only friend, which

kills without exciting ill-feeling, thins the labour market, and makes

wages rise. The

children of the poor are less comely than they would be were they better

fed, and their minds, for want of instruction, are leaner than their

bodies. The little

instruction they get is the bastard knowledge given by the precarious,

grudging, intermitting, humiliating hand of

Charity. [130] Take notice of the changed condition of things

since the days of your forefathers. The stout pole-axe and

lusty arm availeth not now to the brave. The battle of life is fought now

with the tongue and the pen, and the rascal who has learning is more than a

match for a

hundred honest men

without it. Anybody can see that the little money you get is half

wasted, because you cannot spend it to advantage. The worst food comes to the

poor, which

their poverty makes them

buy, and their necessity makes them eat. Their stomachs are the

waste-baskets of the State. It is their lot to swallow all

the adulterations in the market. In these days you all set up a way as

politicians. You go in for the Charter. You

allow agitators to address you as the "sovereign people." You want to be

electors, and counted as persons of political consequence in the State,

and be

treated as only gentlemen are now.

Now, being a gentleman does not merely mean having money. There are plenty

of scoundrels who have that. That, which makes the name of gentleman

sweet is being a

man of good faith and good honour. A gentleman is one who is considerate

to others; who never lies, nor fears, nor goes into debt, nor takes

advantage of his neighbours; and the poorest man in his humble way can be

all this. If you take credit of a shopkeeper you cannot, while you owe him

money, buy of another. In most cases you keep him poor by not paying him. The flesh and bones of your children are his property. The very

plumpness of your wife, if she has it, belongs to your butcher and your

baker. The pulsation of your own heart beats by charity. The clothes on

your

backs,

such as they are, are owned by some tailor. He who lives in

debt walks the streets a mere mendicant machine. Thus all debt is

self-imposed degradation, and he who incurs it lives in bondage and

shabbiness all his days. It is worth while trying Co-operation

again to

get out of this.

-II-

Is there any avenue of competition through which you could creep? If

there be, get into it. In another country you

might have a chance; in England you have none. Every bird in the air,

every fish in the stream, every animal in the woods, every blade of grass

in the

fields, every inch of ground has an owner, and there is no help except

that of self-help in

concert, for any one. If you say you failed through trying to

he honest, nobody will believe you; so few run that risk. It

is not considered "good business." Be sure of this. Honesty

has its liabilities. There are those who tell you of the advantages of truth, but never of its dangers. Truth is dignity, but also a

peril and unless a man knows both sides of it, he will turn into the

easy road of

prevarication, lying, or silence, when

he meets the danger he has not foreseen, and which had not been foretold

to him. When you have a little store, and have reached the point of

getting pure

provisions, you may find your purchasers will not like them, nor know them

when they taste them. Their taste will be required to be educated.

They have never eaten the pure food of gentlemen, and will not know the

taste of it when you supply it to their lips. The London mechanic does not

know

the taste of pure coffee. What he takes to be coffee is a decoction of

burnt corn and chicory. [131] A friend

[132] of mine, knowing this, thought it a

pity workmen

should not have pure coffee, and opened a coffeehouse in the Blackfriars

Road, where numerous mechanics and engineers passed in the early morning

to their work at the engine shops over the bridge. They were glad to see

an early house open so near their work. They tried the coffee a morning or

two and went away without showing any marks of satisfaction. They talked

about it in their workshops. The opinion arrived at was, "they had never

tasted such stuff as that sold at the new place." But before taking

decisive measures they took some shopmates with them to taste the

suspicious

beverage. The unanimous conclusion they came to was that the new

coffee-house proprietor intended to poison them, and if he had not

adulterated his coffee a morning or two later they would have broken his

windows or his head. As it was, the evil repute he had acquired ruined his

project;

and a notice "To let," which shortly after appeared on the shutters, gave

consolation to his ignorant indignant customers. [133]

-III-

What of ambition or interest has industry in this grim, despairing, sloppy

[134] hole of a town, where the parish doctor and the sexton (who understand

each

other) are the best known friends the workmen has. Are there not some

here who have lost mother or father, or wife, or child, whose presence

made the

sunshine of the household which now knows them no

more? Does not the very world seem deserted now that voice

has gone out of it? What would one not give, how far would

one not go, to hear it again? Death will not speak, however earnestly we

pray to it; but we might get out of living industry some voice of joy that

might

gladden thousands of hearts to hear. In all England industry has no tone

that

makes any human creature glad. Listen with the mind's ear to the cry of

every manufacturing town. What is there pleasant in it? [135] Co-operation

might infuse a more hopeful tone into it.

If you really, think that the principle of the thing is wrong, give it up,

announce to your neighbours that you have come to a different opinion. This you ought

to do as candid men of right spirit, so that any adopting the opinion you

have abandoned may understand they must hold it for reasons of their own,

and

cannot any longer plead such sanction or authority as your belief might

lend to their proceedings. If, however, you have convictions that this is

a thing that

can be put through, put it through. Progress has its witches, as Macbeth had,

but the bottom of their old cauldron is pretty well burnt out now. There

are still

persons who will tell you that others have failed, again and again, and

that you pretend to be the wise person, whom the world was waiting for to

show it

how the thing could be done. [136] But every discoverer who found out what

the world was looking for, and never met with; every scientific inventor

who has

persisted in improving the contrivance, which all who went before him

failed to perfect, has been in the same case, and everybody has admitted

at last that

he was the one wise man the world was waiting for, and that he really knew

what nobody else knew, and saw what none who went before him had seen. If

you were to take one of those microscopes which are now coming into use,

and gather the stem of a rosebud and examine it, you would see a number of

small insects, called aphis, travelling along it, in pursuit of some

object interesting to its tiny mind. The thing is so small that you can

scarcely discern it with

the naked eye, but in a microscope you see it put forth its little arms

and legs, carefully feeling its way, now stretching out a foot, moving

slowly along the

side, touching carefully the little projections, moving the limb in the

outer air, feeling for a resting-place, never leaving its position till it

finds firm ground to

stand upon, showing more prudence and patience before it has been alive an

hour, than the mass of grown men and women show when they are fifty

years of age. The aphis begins to move when it is a minute old, and

goes a long way

in its one day of life. It does not appear to wait for the

applause of surrounding insects. So far as I have observed, it does not

ask what its neighbours think, nor pay much attention to what they say

after it

has once set out. Its wise little mind seems devoted to seeing that in

every step forward its foothold is secure. If you have half the prudence

and sagacity

of these little creatures, who are so young that their lives have to be

counted by minutes, and are so small you might carry a million of them in

your

waistcoat pocket, [137] you might make Co-operation a thing to be talked

about in

Rochdale. Do not, like crabs, walk sideways to your graves, but do some

direct, resolute thing before you die.

I expressed, as I had done elsewhere, my conviction that the right men

could do the right thing. My final words were as positive as those used by

a great master in the art of expressing wilfulness [138]:—

|

"This I cannot tell,

Whence I do know it ; but that I know it I know,

And by no casual or conjectural proof;

. . . . . but I know it

Even as I know I breathe, see, hear, feel, speak,

And am not dead," |

that I shall see Co-operation succeed here or elsewhere.

The audience were glad it was over; something was said which implied the

impression that a real fanatic had come to Rochdale at last. Other

advocates

oft visited the town. This address was one of that propagandist time, and

will give the reader the arguments of the pre-Rochdale days. [139] For twenty

years

after that time, whenever I arrived in Rochdale, some store leaders met me

at the railway station, and when I asked, "Where I was to go to?" the

answer

was, "Thou must come and see store." My portmanteau was taken there, my

letters were addressed there, my correspondence was written there, and

my host was commonly James Smithies, or Abram Greenwood. My earliest

recollection is of having chops and wool at Smithies', for he was a waste

dealer, and the woolly odour was all over the house.

The ascendancy of a new movement seems natural in large towns. The larger

the town the greater the need of stores,

and the less is the chance of success. In a large town there is diversity

of life and occupation, greater facilities for diversion, greater

difficulties of business

publicity, greater mobility of employment among workmen, and less

likelihood of a dozen or two men remaining long enough together, pursuing

one object

year after year, necessary to build up a co-operative store. Glasgow is a

town where a prophet would say Co-operation would answer. The thrift,

patience,

and clanship of the Scottish race seem to supply all the conditions of

economy and concert. But though the Scotch are the last people to turn

back when

they once set out, their prudence leads them to wait and see who will go

first. They prefer joining a project when they see it succeeding. There

are men in

Scotland ready to go out on forlorn hopes, but they are exceptions.

It came to pass that the men of Rochdale took the field, and Co-operation

recommenced with them. Alderman Livesey

aided the new movement by his stout-hearted influence. William Smithies,

whose laugh was like a festival, kept it merry in its struggling years.

William Cooper, with his

Danish face, stood up for it. He had what Canon Kingsley called the

"Viking blood" in his veins, and pursued every adversary who appeared in

public, with letters in the newspapers, and confronted him on platforms. Abram Greenwood came to its aid

with his quiet, purposing face, which the Spectator [140] said, "ought to be

painted by Rembrandt," possible because that artist, distinguished for his

strong contrasts, would present the white light of Co-operation emerging

from

the dark shades of competition. And others, whose names are elsewhere

recorded, [141] contributed in that town to the great revival.

CHAPTER XVI.

THE DISCOVERY WHICH RE-CREATED CO-OPERATION

|

"They gave me advice and counsel in store,

Praised me and honoured me more and more;

.

.

.

.

.

.

But, with all their honour and approbation,

I should, long ago, have died of starvation;

Had there not come an excellent man,

Who bravely to help me along began.

Yet I cannot embrace him—though other folks can

.

.

.

.

.

.

For I myself am this excellent man!"

HEINE, translated by Leland. |

THE men of Rochdale were they who first took the name of Equitable

Pioneers. Their object was to establish equity in industry—the idea which

best

explains the spirit of modern Co-operation. Equity is a better term than

Co-operation, as it implies an equitable share of work and profit, which

the

word Co-operation does not connote. Among the Pioneers was an original,

clear-headed, shrewd, plodding thinker, one Charles Howarth, who set

himself

to devise a plan by which the permanent interest of the members was

secured. It was that the profits made by sales should be divided among all

members

who made purchases, in proportion to the amount they spent, and that the

shares of profits coming due to them should remain in the hands of the

directors until it amounted to £5, they being registered as shareholders

of that amount. This sum they would not have to pay out of their pockets. The store

would thus save their shares for them, and they would thus become

shareholders without it costing them anything; so that if all went wrong

they lost

nothing; and if they stuck like sensible men to the store, they might

save in the same way other £5, which they could draw out as they pleased.

By this scheme the stores ultimately obtained £100 of capital from each

twenty members. For this capital they paid an interest of 5 per

cent. Of course, before any store could commence, some of the more

enterprising promoters must subscribe capital to buy the first stock.

This capital in Rochdale was mostly raised by weekly subscriptions of

two-pence. In order that there might be as much profit as possible

to divide among purchasers, 5 per cent. has become to be regarded as the

Co-operative standard rate of interest. The merit of this scheme was

that it created capital among men who had none, and allured purchasers to

the store by the prospect of a quarterly dividend of profits upon their

outlay. Of course those who had the largest families had the largest

dealings, and it appeared as though the more they ate the more they

saved—a fortunate illusion for the hungry little ones who abounded in

Rochdale then.

The device of dividing profits with purchasers was original

with Mr. Howarth, although seventeen years in operation at no very great

distance from Rochdale. It is singular that it was not until

twenty-six years after Mr, Howarth had devised his plan (1844), that any

one was aware that it was in operation in 1827. Mr. William Nuttall,

in compiling a statistical table for the Reasoner in 1870,

discovered that an unknown society, at Meltham Mills, near Huddersfield,

had existed for forty-three years, having been commenced in 1827, and had

divided profits on purchases from the beginning. But it found

neither imitators nor propagandists in England.

Mr. Alexander Campbell also claimed to have recommended the

same principle in an address which he drew up for the Co-operative Bakers

of Glasgow, in 1822: that he fully explained it to the co-operators of Cambuslang, who adopted it in 1831; and that a pamphlet was circulated at

the time containing what he said upon the subject. Mr. Campbell

further declared that in 1840 he lectured several times in Rochdale, and

in 1843-4, when they were organising their society of Equitable Pioneers,

they consulted him, and he advised them by letter to adopt the principle

of dividing profits on purchases, and, at the same time, assisted in

forming the London Co-operative Society on the same principle. No

one has ever produced the pamphlet referred to, or any copy of the rules

of any Scotch society, containing the said plan, nor is any mention of it

in London extant. Yet it is not unlikely that Mr. Campbell had the idea

before the days of Mr. Howarth. It is more likely that the idea of

dividing profits with the customer was separately originated. Few persons

preserve records of suggestions or rules which attracted small attention

in their day. All the Pioneers contemporary with him believed the plan

originated with Howarth. The records of the patent offices of all

countries show that important inventions have been made again, by persons

painfully startled to find that the idea which had cost them years of

their lives to work out, had been perfected before they were born. Coincidence of discovery in mechanics, in literature, and in every

department of human knowledge, is an axiom among men of experience. From

1822 to 1844 stores limped along and failed to attract growing custom,

while dividends were paid only on capital.

It was by taking the public into partnership that the new Co-operation

came to grow. [142] Few persons believed stores could be re-established. Customers at the store were scarce and uncertain, it was so small a sum

that was likely to arise to be given them, and for a long time it was so

little that it proved little attraction. The division of profits among

customers, though felt to be a promising step, not being foreseen as a

great fortune, was readily agreed to. No one foresaw what a prodigious

amount it would one day be. Thirty years later the profits of the Rochdale

Store amounted to £50,668, and the profits of the Halifax Store reached

£19,820, and those of Leeds £34,510. Had these profits existed in Mr.

Howarth's time, and he had proposed to give such amazing sums to mere

customers, he would have been deemed mad, and not half a dozen persons

would have listened

to him outside Bedlam. When twenty members constituted a society, and they

made with difficulty ten shillings a year of profit altogether, the

proposal to divide it excited no suspicion. A clear income of sixpence, as

the result of twelve months' active and daily attention to business,

excited no jealousy. But had £50,000 been at the disposal of the

committee, that would have seemed a large fortune for twelve directors,

and no persuasive power on earth would have induced them to divide that

among the customers. It would have been said, "What

right has the customer to the gains of our trade? What does

he do towards creating them? He receives value for his

money. He gives no thought, he has no cares, he performs

no duties, he takes no trouble, he incurs no risks. If we lose

he pays no loss. Why should we enrich him by what we

win?" Nobody then could have answered these questions. But when the

proposal came in the insidious form of dividing scanty profits, with

scarce customers, Mr. Howarth's scheme was adopted, and Co-operation rose

from the grave in which short-sighted greed had buried it, and it began

the mighty and stalwart career with which we are now conversant. It really

seems as though the best steps we take never would be taken, if we knew

how wise and right they were.

The time came when substantial profits were made—actually paid over the

counter, tangible in the pocket, and certain of recurrence, with increase,

at every subsequent quarter-day. The fact was so unexpected that when it

was divulged it had all the freshness and suddenness of a revelation to

outsiders. The effect of this patient, unforeseen success was diffused

about—we might say, in apostolical language—"noised abroad." There

needed no advertisement to spread it. When profits—a new name among

workpeople—were found to be really made, and known to be really paid to

members quarter

by quarter, they were copiously heard of. The animated face of the

co-operator suggested that his projects were answering

with him. He appeared better fed, which was not likely to

escape notice among hungry weavers. He was better dressed than formerly,

which gave him distinction among his shabby

comrades in the mill. The wife no longer had "to sell her petticoat,"

known to have been done in Rochdale, but had a new gown, and she was not

likely to be silent about that; nor

was it likely to remain much in concealment. It became a walking and

graceful advertisement of Co-operation in every

part of the town. Her neighbours were not slow to notice the change in

attire, and their very gossip became a sort of propagandism; and other

husbands received hints they might as well belong to the store. The

children had cleaner faces, and new pinafores or new jackets, and they

propagated the source of their new comforts in their little way, and other

little children communicated to their parents what they had seen. Some old

hen coops were furbished up and new pullets were observed in them—the

cocks seemed to crow of Co-operation. Here and there a pig, which

was known to belong to a co-operator, was seen to be fattening, and seemed

to squeal in favour of the store. After a while a pianoforte was

reported to have been heard in a co-operative cottage, on which it was

said the daughters played co-operative airs, the like of which had never

been heard in that quarter. There were wild winds, but neither tall

trees nor wild birds about Rochdale; but the weavers' songs were not

unlike those of the dusky gondoliers of the South, when emancipation first

came to them:—

|

"We pray de Lord he gib us sign

Dat one day we be free;

De north wind tell it to de pines,

De wild duck to de sea.

We tink it when the church bell rings,

We dream it in de dream;

De rice-bird mean it when he sings,

De eagle when he screams." [143] |

The objects of Nature vary, but the poetry of freedom is everywhere the

same. The store was talked about in the mills. It was canvassed in the

weaving shed. The farm labourer heard of it in the fields. The coal miner

carried the news down the pit. The blacksmith circulated the news at his

forge. It was the gossip of the barber's chair—the courage of beards

being unknown then. Chartists, reluctant to entertain any question but the

"Six Points," took

the store into consideration in their societies. In the newspapers letters

appeared on the new movement. Preachers who found their pew rents increase

were more reticent than in

former days about the sin of Co-operation. "Toad Lane" (where the store

stood) was the subject of conversation in the public-house. It was

discussed in the temperance coffee-shop. The carriers spread news of it in

country places, and what was a few years before a matter of derision,

became the curios, inquiring, and respectful talk of all those parts. The

landlord found his rent paid more regularly, and whispered the fact

about. The shopkeeper told his neighbour that customers who had been in

his debt for years had paid up their accounts. Members for the Borough

became aware that some independent voters were springing up in

connection with the

store. Politicians began to think there was something in it. Wandering

lecturers visiting the town found a better quality of auditors to address,

and were invited to houses where tables were better spread than formerly,

and were taken to see the store, as one of the new objects of interest in

the town, with its news-room, where more London papers could be seen than

in any coffee-house in London, and word was carried of what was being done

in Rochdale to other towns. News of it got into periodicals in London. Professors and students of social philosophy from abroad came to visit it,

and sent news of it

home to their country. And thus it spread far and wide that the shrewd men

of Rochdale were doing a notable thing in the way of Co-operation. It was

all true, and honour will long be accorded them. For it is they, in

whatever rank, who act for the right when others are still, who decide

when others doubt, who urge forward when others hang back, to whom the

glory of great change belongs.

Thus the Rochdale Co-operators found, like Heine, "that his best friend

was himself."

|

|

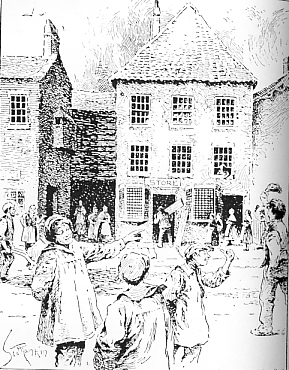

|

The original Toad Lane store, Rochdale

The Doffers appear on the Opening Day. |

CHAPTER XVII.

CAREER OF THE PIONEER STORE

|

"But every humour hath its adjunct pleasure,

Wherein it finds a joy above the rest:

But these particulars are not my measure,

All these I better in one general best."

SHAKESPEARE. |

THE first we hear of Rochdale in co-operative literature is an

announcement in the Co-operative Miscellany for July, 1830, which

"rejoices to hear that through the medium of the Weekly Free Press a

co-operative society has been formed in this place, and is going on well. Three public meetings have been held to discuss the principles. They have

upwards of sixty members, and are anxious to supply flannels to the

various co-operative societies. We understand the prices are from £1

15s.

a piece to £5, and that J. Greenhough, Wardleworth Brow, will give every

information, if applied to."

The Rochdale flannel weavers were always in trouble for want of work. In

June, 1830, they had a great meeting on Cronkey Shaw Moor, which is

overlooked by the house once owned by

Mr. Bright. At that time there were as many as 7,000 men out

of employ. There was an immense concourse of men, women, and children on

the moor, although a drizzling rain fell during the speeches—it always

does rain in Rochdale when the flannel weavers are out. One speaker, Mr.

Hinds, declared "that wages had been so frequently reduced in Rochdale

that a flannel weaver could not, by all his exertions and patience,

obtain more than from 4s. to 6s, per week." Mr. Renshaw quoted the opinion

of "Mr. Robert Owen at Lanark, a gentleman whose travels gave him ample

scope for observation, who had declared, at a recent public meeting in

London, 'that the

inhabitants of St. Domingo, who were black slaves, seemed to be in a

condition greatly to be preferred when that of English operatives.'" [144] Mr. Renshaw said that

"when his hearers went home they would find an empty

pantry mocking their hungry appetites, the house despoiled of its

furniture, an

anxious wife with a highway paper, or a King's taxes paper, in her hand,

but no money to discharge such claim. God help

the poor man when misfortune overtook him! The rich man in his misfortune

could obtain some comfort, but the poor

man had nothing to flee to. Cureless despondency was the

condition to which he was reduced." It was this year that the first

co-operative society was formed in Rochdale. The meeting on Cronkey Shaw

Moor was on behalf of the flannel weavers who were then out on strike. The

Rochdale men were distinguished among unionists of that time for vigorous

behaviour. It appears that during the disturbances in Rochdale, in the

year 1831, the constables—"villainous constables," as the record I

consult describes them—robbed their box. One would think there was not

much in it. However, the men succeeded in bringing the constables to

justice, and in convicting them of felony.

It would appear that Rochdale habitually moved by twopences. The United

Trades Co-operative Journal of Manchester recorded that, notwithstanding

the length of time the flannel weavers and spinners had been out, and the

slender means of support they had, they had contributed at twopence per

man the sum of £30, as their first deposit to the Protection Fund, and

that one poor woman, a spinner, who could not raise the twopence agreed

upon at their meeting, was so determined not to be behind others in her

contributions to what she properly denominated "their own fund," that she

actually sold her petticoat to pay her subscriptions.

At the Birmingham Congress of 1832 the Rochdale Society sent a letter

urging the utility of "discussing in Congress the establishment of a

Co-operative Woollen Manufactory; as the Huddersfield cloth, Halifax and

Bradford stuffs, Leicester and Loughborough stockings, and Rochdale

flannels required in

several respects similar machinery and processes of manufacture, they

thought that societies in these towns might unite together and manufacture

with advantages not obtainable by separate

separate

establishments." At that early period there were co-operators

in Rochdale giving their minds to federative projects. Their delegate was

Mr. William Harrison, and their secretary, Mr. T.

Ladyman, 70, Cheetham Street, Rochdale. Their credentials stated that "the

society was first formed in October, 1830, and bore the name of the

Rochdale Friendly Society.

Its members were fifty-two, the amount of its funds was £108. It

employed ten members and their families. It manufactured

flannel. It had a library containing thirty-two volumes. It had no school,

and never discussed the principles of Labour Exchange , and had two other

societies in the neighbourhood." It was deemed a defect in sagacity not to

have inquired into the uses of Labour Exchanges as a means of

co-operative profit and propagandism. Rochdale from the beginning had a

creditable regard for books and education. It also appears—and it is of

interest to note it now—that "wholesale" combination was an early

Rochdale idea.

From 1830 to 1840 Rochdale went on doing something. One thing recorded is

that it converted the Rev. Joseph Marriott to social views—who wrote "Community: a Drama." Another is that in 1838 a "Social Hall" was opened

in Yorkshire Street. These facts of Rochdale industrial operations, prior

to 1844, when the germ store began, show that this co-operative idea "was

in the air." It could hardly be said to be anywhere else until it

descended in Toad Lane, and that is where it first touched the earth, took

root, and grew.

Like curious and valuable animals which have oft been imported, but never

bred from, like rare products of Nature that have frequently been grown

without their cultivation becoming general—Co-operation had long existed

in various forms; it is only since 1844 that it has been cultivated. Farmers grew wheat before the days of Major Hallett, and practised thin

sowing, and made selections of seed—in a way. But it was not until that

observing agriculturist traced the laws of growth, and demonstrated the

principles of selection, that "pedigree wheat" was possible, and the

growing powers of Great Britain capable of being tripled.

Similar has been the effect of the Pioneer discovery of participation in

trade and industry.

Of the "Famous Twenty-eight" old Pioneers, who founded the store by their

humble subscriptions of twopence a week, James Smithies was its earliest

secretary and counsellor. In his later years he became one of the Town

Councillors of the borough—the only one of the Twenty-eight who attained

municipal distinction. After a late committee meeting in days of faltering

fortunes at the store or the corn mill, he would go out at midnight and

call up any one known to have money and sympathy for the cause. And when

the disturbed sympathiser was awake and put his head out of the window to

learn what was the matter, Smithies would call out, "I am come for thy

brass, lad. We mun have it." "All right!" would be the welcome

answer. And in one case the bag was fetched with nearly £100 in, and

the owner offered to drop it through the window. "No; I'll call in

the morning," Smithies replied, with his cheery voice, and then would go

home contented that the evil day was averted. In the presence of his

vivacity no one could despond, confronted by his buoyant humour no one

could be angry. He laughed the store out of despair into prosperity.

William Howarth, the "sea lawyer" of Co-operation, is no more. I

spoke at the grave of William Cooper, and wrote the inscription for his

tomb:—

In Memory of

WILLIAM COOPER

WHO DIED OCTOBER 31ST, 1868, AGED 46 YEARS.

ONE OF THE ORIGINAL "28" EQUITABLE PIONEERS,

HE HAD A ZEAL EQUAL TO ANY, AND EXCEEDED ALL

IN HIS CEASELESS EXERTIONS, BY PEN AND SPEECH.

THE GREATER AND RARER MERIT OF STANDING BY PRINCIPLE

ALWAYS, REGARDLESS ALIKE OF INTERESTS, OF FRIENDSHIPS,

OR OF HIMSELF.

AUTHOR OF THE

"HISTORY OF THE ROCHDALE

CO-OPERATIVE CORN

MILL SOCIETY."

The following page of facts tells the progress and

triumph of the Pioneers reduced to figures:—

Table of the operations of the Society from its commencement in 1844 to

the end of 1876:—

|

Year |

Members |

Funds (£) |

Business (£) |

Profits (£) |

|

1844 |

28 |

28 |

… |

… |

|

1845 |

74 |

181 |

710 |

22 |

|

1846 |

80 |

252 |

1,146 |

80 |

|

1847 |

110 |

286 |

1,924 |

72 |

|

1848 |

149 |

397 |

2,276 |

117 |

|

1849 |

390 |

1,193 |

6,611 |

561 |

|

1850 |

600 |

2,289 |

13,179 |

880 |

|

1851 |

630 |

2,785 |

17,633 |

990 |

|

1852 |

680 |

3,471 |

16,352 |

1,206 |

|

1853 |

720 |

5,848 |

22,700 |

1,674 |

|

1854 |

900 |

7,712 |

33,374 |

1,763 |

|

1855 |

1,400 |

11,032 |

44,902 |

3,109 |

|

1856 |

1,600 |

12,920 |

63,197 |

3,921 |

|

1857 |

1,850 |

15,142 |

79,789 |

5,470 |

|

1858 |

1,950 |

18,160 |

74,680 |

6,284 |

|

1859 |

2,703 |

27,060 |

104,012 |

10,739 |

|

1860 |

3,450 |

37,710 |

152,063 |

15,906 |

|

1861 |

3,900 |

42,295 |

176,206 |

18,020 |

|

1862 |

3,501 |

38,465 |

141,074 |

17,564 |

|

1863 |

4,013 |

49,961 |

158,632 |

19,671 |

|

1864 |

4,747 |

62,105 |

174,937 |

22,717 |

|

1865 |

5,326 |

78,778 |

196,234 |

25,156 |

|

1866 |

6,246 |

99,989 |

249,122 |

31,931 |

|

1867 |

6,823 |

128,435 |

284,912 |

41,619 |

|

1868 |

6,731 |

123,233 |

390,900 |

37,459 |

|

1869 |

5,809 |

93,423 |

236,438 |

28,642 |

|

1870 |

5,560 |

80,291 |

223,021 |

25,209 |

|

1871 |

6,021 |

107,500 |

246,522 |

29,026 |

|

1872 |

6,444 |

132,912 |

267,577 |

33,640 |

|

1873 |

7,021 |

160,886 |

287,212 |

38,749 |

|

1874 |

7,639 |

192,814 |

298,888 |

40,679 |

|

1875 |

8,415 |

225,682 |

305,657 |

48,212 |

|

1876 |

8,892 |

254,000 |

305,190 |

50,668 |

These columns of figures are not dull, prosaic, merely statistical, as

figures usually are. Every figure glows with a light unknown to chemists,

and which has never illumined any town until the Rochdale day. Our

forefathers never saw it. They looked with longing and wistful eyes over the dark

plains of industry, and no gleam of it appeared. The light they looked for

was not a pale, flickering, uncertain light, but one self-created,

self-fed, self-sustained, self-growing, and daily growing, not a light of

charity or paternal support, but an inextinguishable, independent light. Every numeral in the

table glitters with this new light. Every column is a pillar

of fire in the night of industry, guiding other wanderers than Israelites

out of the wilderness of helplessness from their Egyptian bondage.

The Toad Lane Store has expanded into nineteen branches with nineteen

news-rooms. Each branch is a far finer building than the original store. The Toad Lane parent store has long been represented by a great Central

Store, a commanding pile of buildings which it takes an hour to walk through,

situated on the finest site in the town, and overlooks alike

the Town Hall and Parish Church. The Central Stores contain a vast

library, which has a permanent librarian, Mr. Barnish. The store spends

hundreds of pounds in bringing out a new catalogue as the increase of

books needs it. Telescopes, field-glasses, microscopes innumerable, exist

for the use of members. There are many large towns where gentlemen have no

such newsrooms, so many daily papers, weekly papers, magazines, reviews,

maps, and costly books of reference, as the working class co-operators of

Rochdale possess. They sustain science classes. They own property all over

the borough. They have estates covered with street;

of houses built for co-operators. They have established a large corn mill

which was carried through dreary misadventures by the energy and courage

of Mr. Abram Greenwood—misadventures trying every degree of patience and

every form of industrial faith. They built a huge spinning mill, and

conducted it on profit-sharing principles three years, until outside

shareholders perverted it into a joint-stock concern. None of the old

pioneers looked back on the

Sodom of competition. Had they done so they would have

been like Lot's wife, saline on the pillar of history. They set the

great example of instituting and maintaining an

Educational Fund out of their profits. They sought to set up

co-operative workshops—to employ their own members and support them on

land, of which they should be the owners, and create a self-supporting

community.

CHAPTER XVIII.

PARLIAMENTARY AID TO CO-OPERATION

"Law is but morality shaped by Act of Parliament."—MR.

BERNAL, Chairman of

Committees, House of Commons.

THE device of Mr. Howarth had not carried Co-operation far, had it not

been for friendly lawyers and Parliament. The legal impediments to

industrial economy were serious in 1844. Because "men cannot be made wise

by Act of Parliament"

is no reason for not making Acts of Parliament wise. "Law should be

morality shaped by Act of Parliament." None, however, knew better than Mr.

Bernal, that if there was any morality in a Bill at first it often got

"shaped" out of it before it became an Act. Nevertheless there is a great

deal of living morality in the world which would be very dead had not law

given it protection. A law once made is a chain or a finger-post—a

barrier or a path. It stops the way or it points the way. If an obstacle

it stands like a rock. It comes

to be venerated as a pillar of the constitution. The indifferent think it

as well as it is—the timid are discouraged by it—the

busy are too occupied to give attention to it. At last, some ardent,

disinterested persons, denounced for their restlessness, persuade

Parliament to remove it, and the nation passes forward. [145]

The Legislature did open new roads of industrial advancement. Working men

can become sharers in the profits of a commercial undertaking without

incurring unlimited liability, an advantage so great that the most

sanguine despaired living to see its enactment. This act was mainly owing

to William Schofield, M.P. for Birmingham.

In a commercial country like England, one would naturally expect that law

would be in favour of trade; yet so slow was the recognition of

industrial liberty that an Act was a long time in force, which enabled a

society to sell its products to its own members, but not to others. Thus

the Leeds Corn Mill, as Mr. John Holmes related, naturally produced bran

as well as flour, could sell its flour to its members, and its bran also,

if

its members wanted it. But the members, not being rabbits did not want the

bran; and at one time the Corn Mill Society had as much as £600 worth of

bran accumulated in their storerooms which they were unable to sell to

outside buyers. Societies were prohibited holding more than one acre of

land, and that not as house or farm land, but only for transacting the

business of the society upon. The premises of the Equitable Pioneers

occupied land nearly to the extent allowed by the Act. All thoughts of

leasing or purchasing land whereon to grow potatoes, corn, or farm produce

were prevented by this prohibitary clause. Co-operative farming was

difficult. No society could invest money except in savings banks or

National Debt funds. No rich society could help a poor society by

a loan. No member could save more than £100. The Act prohibited funds

being used for educational purposes, and every member was practically

made responsible for all the debts of the society—enough to frighten any