|

YORK, AND ITS MEMORIES.

(from The Sunday at Home, annual edition,

1898-99,

The Religious Tract Society.)

_______________

|

|

Replaced

in the crypt when the South Transept

was restored. |

IT has been

playfully said that there are some places which many of us associate

chiefly with a mail or a meal! They are somewhat passed over,

because they are so much passed through. Among such we may

indicate Marseilles, Inverness and York.

As compared with the countless multitudes who know its

railway station, few, indeed, know York though every one is familiar

with its fame as a city. In past times when the north and

south of England were practically far apart, York was the northern

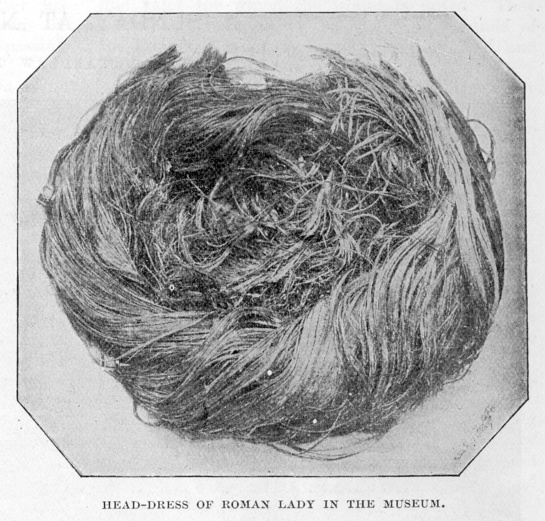

capital. The Roman invaders settled and fortified themselves

there, even as they did in London. They gave it the name of

Eboracum, which has reached its present brief form of York through

Anglo-Saxon and Danish modification.

York plays a distinct part in the Roman occupation. It

was the headquarters of the sixth legion. The capable,

unscrupulous Emperor Severus, born in Africa, died in this bleak

garrison, his body being burned there and his ashes carried to Rome.

When the Empire was divided between Galerius and Constantius Chlorus,

Britain fell to the share of the latter, who took up his abode in

York, where he died two years later. Here the army proclaimed

his son and successor, who was afterwards known as Constantine the

Great.

From that time, or soon after, the Empire, distracted within

itself, gradually withdrew its troops, and the Roman rule faded out

of Britain. Yet not before it had left well-nigh indelible

marks upon York, in walls, roads, and urns, and in the curious

multangular tower in the Museum gardens beside the Lendal Bridge,

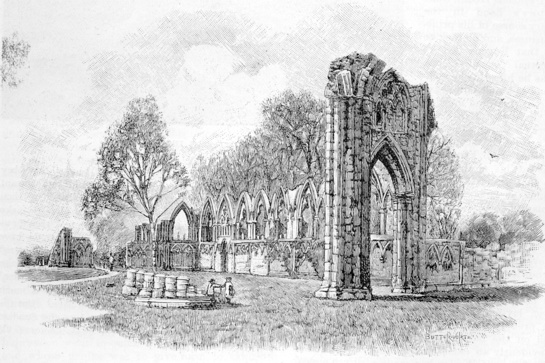

where we may also see the fine ruins of St. Mary's Abbey. This

multangular tower, with its nine obtuse angles, has been undoubtedly

heightened during the Middle Ages, but its plan and its lower part

are as the Romans left it.

The city of York bore full share of the subsequent struggles

between Britons, Saxons and Danes. One happier legend,

emerging from the clouds of that stormy time, tells us that it was

in York early in the sixth century, A.D., that the half-mythical

King Arthur kept the first Christmas that was ever celebrated in

Great Britain.

In this connection we may mention that there was a strange

old Christmas custom in Yorkshire. It is not long since it

became extinct—if indeed it is wholly so. Poor women, crooning

a carol, used to carry round what was called the "Advent image"—a

figure of Jesus, placed in a box with evergreens and any flowers

obtainable. It was thought unlucky to refuse a trifling gift

to the image-bearer, and those who bestowed this were at liberty to

take a leaf from the floral decorations to be stored as a sovereign

remedy for toothache. People were uneasy if they did not get a

call from the image-bearer before Christmas Eve. Indeed, there

was a Yorkshire saying "As unhappy as the man who has seen no

Advent-image."

About a hundred years after Arthur's Christmas festival, the

famed Paulinus arrived in the north of England, a missionary from

Rome to win the country from heathendom. He baptised the King

of Northumbria and many of his subjects on Easter day, in a little

wooden church on the spot where the minster now stands.

This original and primitive building was replaced by another

of stone, which, however, lay incomplete till it was taken in hand

by Archbishop Wilfrid, who roofed it with lead, and put glass in the

windows "to keep out the birds." His influence was not

confined to York, but extended to religious foundations in Ripon and

Hexham, and even in the south, for it is said that "he taught the

men of Sussex to fish while he won their souls to God." When

one reads a description of him as "a quick walker, expert in all

good works, with never a sour face," one seems to know the man.

Wilfrid's building was destroyed by fire during the Norman

Conquest. [note]

William the Norman having suffered a severe check at York, exacted

such fearful reprisals, that an old authority declares that "there

perished in Yorkshire on this occasion, above 100,000 human beings."

It was William the Norman and his followers who built York

Castle with the grim keep called Clifford's Tower. They are,

indeed, very typical of what a plaintive Saxon chronicle recounts of

the conquerors. "They grievously oppressed the poor people by

building castles, and when they were built they filled them with

wicked men, or rather devils, who seized both men and women who they

imagined had any money, threw them into prison, and put them to more

cruel tortures than the martyrs ever endured."

It must be admitted that the same period saw the foundation

of many religious houses, such as those of Jervaulx, Rievaulx,

Bridlington, romantic Bolton, stately Beverley, and secluded

Fountains, which served at that time as refuge for those men who

loved quiet and study, and furnished a safe retreat for noble maids

and matrons, who, in the words of Walter Scott (in "Ivanhoe ")

desired "to assume the veil and take shelter in convents . . .

solely to preserve their honour from the unbridled wickedness of

man."

Perhaps the darkest day in the history of York Castle was in

the beginning of the reign of the crusading Richard I. (1190), when

a body of armed men attacked the Jews resident in the city.

Five hundred Jews carrying with them what they could, flew to the

castle. All who did not reach there soon enough were massacred

outside the gate. The Jews held the castle till famine itself

invaded it; then, on the advice of an old rabbi, they fired the

building, killing their wives and children with their own hands to

spare them from worse horrors. All perished together. A

few hoped to save their lives by "professing Christianity." It

was all in vain. As soon as the last was despatched, the mob

went to the cathedral, seized the register of money lent by the Jews

and burned it in the nave.

This detail serves to explain that financial bitterness was

blent with "religious" and racial hatred. The Jews had all the

unpopular virtues, thrift, industry, surpassing capacity in

handicraft, and a mysterious skill in drugs and medicaments.

Besides, were they not usurers? The rude populace did not heed

that these Jews were, in the end, but the unwilling collectors for

the Norman lords, who when they chose, extorted their wealth from

them by torture and violence. Still less could they consider

that usury was well-nigh forced on the Jews, by the "Christian"

fanaticism which had barred every avenue for Hebrew aspiration, save

that of money-making.

The present minster was begun about twenty-five years after

this scene of violence. As it was not finished till 1472, it

must have been far indeed from completion, when Edward III. was

there married to Philippa of Hainault, their nuptials filling York,

says Froissart, "with jousts and tournament in the daytime, and

songs and dances in the evening, for weeks together." Yet

these festivities ended in funerals—as festivities so often do!

The Flemings attendant on the bride's relations quarrelled with the

citizens, set fire to part of the city and finally had a regular

battle, in which nearly eight hundred people (of both sides) were

slain.

The royal pair maintained an intimate association with York.

Sixteen years after their marriage, a little son of theirs died

there, and lies buried in the minster. A year or two later,

the same queen rode from York to repel an invading army of Scots

whom she defeated near Durham.

All through the Plantagenet period York stood as the capital

of the north. Besides receiving the official presence of

royalty, twelve parliaments were held in the city, and the Courts of

Chancery and the King's Bench actually sat there, for some months.

The importance and the large population of York at this time may be

inferred from the fact that a single epidemic is said to have

carried off no fewer than eleven thousand of the citizens.

The minster does not stand secluded among soft green lawns

and noble trees. Though of late years, good work has been done

in opening up its approaches, still it stands quite in the town.

Its plan—the form of a cross, and its proportions, are of the

simplest. In the height of its roofs, it excels every other

English cathedral. It is particularly distinguished for its

exquisite old stained glass—the Five Sisters' Window, so called from

the mythical legend that the pattern was designed by a family of

ladies—the great "rose" window in the south transept, the noble west

window dating from 1330-1350, and considered one of the finest

decorated windows in England, and the great east window, "the

largest window in England or probably the world, still containing

its original glazing." The contract for this window, drawn up

between the dean and chapter and one John Thornton of Coventry is

dated 1405. John Thornton was to receive for his own share of

the work four shillings a week, and was to complete his task within

three years. We will try to arrive at the "purchasing value"

of this sum at that period. Assuming that one intrusted with

such a work is likely to have been the head of a household, we find

that he could have bought as follows:—

| |

s. d. |

| Half-quarter of wheat |

1 0 |

| Half a sheep |

0 4 |

| Six pigeons |

0 6 |

| One pig |

0 1 |

| Twenty eggs |

0 1 |

| |

2 0 |

which would have left him half his income for the purchase of milk,

small beer, fuel, clothing, the payment of rent and dues, and any

saving necessary or possible. Thus, allowing for all the

difference of money value, we see that "John Thornton" did his

beautiful work without any thought of luxury, though it is equally

true that these greatest luxuries of all, quiet, pure air, and open

country, were his without money or price.

Few of the monuments in the minster are of great interest. In

the south aisle, we see the sculptured figure of Archbishop Sterne,

who had played a prominent part on the Royalist side during the

disaster which befel King Charles' army in the north. The

chief interest of this grave is with one who is not buried in it.

For this Archbishop Sterne was grandfather of that master humorist

and unworthy man, the Rev. Laurence Sterne, who enriched English

literature by his creation of the matchless "Uncle Toby." His

own virtues and vices alike belonged essentially to the camp (where

for the first eleven years of his life he followed the fortunes of

his father, the archbishop's son and his mother, a "suttler's

daughter"), and were scarcely suited to dignities and preferments,

yet family influence secured him a Yorkshire parish, and made him a

prebendary before he was twenty-five. The general frivolity of

his life but deepens the pathos of its close. He died (his

death hastened, it is said, by chagrin over a rebuke) in a London

lodging attended only by a hireling who drew the rings from the dead

man's stiffening fingers. He was followed to his grave in a

Bayswater burying grave by mere formal mourners, while from that

resting-place (so runs tradition) his corpse presently found its way

to a dissecting table from which, however, it appears to have been

finally rescued. The only mark his grave ever received was put

up by strangers—said to belong to a tippling fraternity! In

all his life, Sterne seems to have had but one sincere affection—an

intense love for his little daughter, who afterwards perished on the

Parisian scaffold during the Great French Revolution.

Stored away in the minster vestry, is a curiously carved horn, which

dates almost from the time of Canute the Dane. It belonged

originally to his son-in-law Ulph, who seems to have had reason to

fear that his sons would quarrel over the division of his wealth.

He vowed he would make them equal, but was shrewd enough to know

that nothing can be made to seem equal in the eyes of the covetous

and jealous. So he took down his horn, went to the altar of

the cathedral, filled the horn with wine and drank it off,

dedicating all he had to the service of God, and leaving his sons

with the indisputable equality of nothing!"

The ancient chapter house of York Minster deserves especial

attention, even apart from its singular architectural beauty.

Above the stalls, we find a series of beads and figures—the latter

grotesque—the former generally of a pitiless realism.

Evidently the artist-workmen of the Middle Ages had their eyes open

to see how human nature underlies all conventional sanctities.

For here, we find the faces of monk and nun, lady abbess and lord

bishop, set forth plainly as those of mere men and women, often

mean, sensual, haughty, sly, covetous, or commonplace, but

occasionally simple, pure and patient. As for the grotesque

figures, it is not always easy to grasp their symbolism. We

puzzled long over one setting forth a monkey and a lamb. The

impression one carries away is that the mediæval ecclesiasticism

permitted a full share of unconventionality! These are, as

Ruskin says, "the signs of the life and liberty of every workman who

struck the stone."

As we pass out of the cathedral we notice the following

appeal to the crowds of sightseers who constantly pass through it,

as well as to the work people and other functionaries employed about

it:—

|

"Whosoever thou art that enterest here,

Wilt thou not offer before thou leavest

a prayer to God for

Thyself,

For those who worship, and those who

minister before Him in this, His House;

For His Holy Church throughout all the

world?

If thou speakest thine own words here, let

thy voice (hushed to a whisper) show that

thou knowest this to be the House of God.

If thou workest with thy hands in this

church,

Let thy quiet and reverent demeanour

testify that thou art in the House of the

King of kings and the Lord of lords." |

Leaving the minster, and walking down ancient Stonegate, with

its picturesque gables, we see on our right hand the restored old

church of St. Michael-le-Belfry. In its parish was born Guy

Faux, the hero of that abortive and mysterious "Gunpowder Plot"

which sank so deeply into the fears and prejudices of the populace

that the street-boys still exhort us to "remember, remember, the

fifth of November!"

Another native of York who also attained a sinister

reputation, though of another kind, was Henry Hudson, the so-called

"Railway King," whose tale points a very modern "moral."

Hudson was born at York at the beginning of this century, and

started in life as a shopkeeper. But when quite a young man, a

sudden accession of wealth—a fortune of £30,000—drew him from the

paths of industry to those of speculation. The then recent

establishment of railways offered him a field for his money-making

energy. New lines were recklessly projected, and financed.

Hudson was elevated to the dictatorship of railway speculation.

It seemed as if everything he touched turned to gold for him and

those who trusted him. The multitude ever ready (from the time

of the golden calf!) to worship any idea clad in precious metal,

actually raised their favourite money-maker into a hero, and £25,000

was collected to rear him a statue, a matter worthy of all the

powers of invective which Carlyle poured upon it in the seventh of

his Latter Day Pamphlets. He pertinently says:—

"To give our approval aright—to do

every one of us what lies in him, that the honourable man

everywhere, and he only, have honour; that the able man everywhere

be put into the place which is fit for him, which is his by eternal

right: is not this the sum of all social morality for every citizen

of this world?"

He adds:—

"Who is to have a statue? means,

whom shall we consecrate and set apart as one of our sacred men?

Sacred, that all men may see him, be reminded of him, and by new

example added to old perpetual precept, be taught what is real worth

in man. Whom do you wish us to resemble?"

Of such as Hudson and other mere money-makers Carlyle asks:—

"Are these your Pattern Men?

Great men? They are lucky (or unlucky) gamblers swollen big. . . .

How much could one have wished that the making of our British

railways had gone on with deliberation; that these great works had

made themselves, not in five years but in fifty and five! . . .

Hudson's 'worth' to railways, I think, will mainly resolve itself

into this. That he got them carried to completion within the

former short limit of time:—that he got them made,—in extremely

improper directions, I am told, and surely with endless confusion to

innumerable passive victims, and likewise to innumerable active

scrip-holders, a widespread class, once rich, now coinless—hastily

in five years, not deliberately in fifty-five. His worth, I

take it, to English railways, much more to English men, will turn

out to be extremely inconsiderable—to be incalculable damage

rather!"

Even before Carlyle penned that article the collapse had

begun. In 1845 it was discovered that the sum required for the

mere "deposit" of the capital which was to start upwards, of twelve

hundred new railways, actually exceeded by twenty millions the whole

amount of English gold and notes in circulation! This blow not

only extinguished more than eleven hundred of the new schemes, but

dealt a heavy shock to the already existing companies.

Wide-spread ruin was the result, and Hudson, suspected of having

"cooked" companies' accounts and paid dividends out of capital,

eventually disappeared into the penury and obscurity wherein at last

he died. The trouble might have been saved, if only heed had

been given to the ancient warning that he who maketh haste to be

rich, poverty shall come upon him."

But York has brighter associations. It was the

birthplace of John Flaxman, the sculptor. Though he left York

for London when he was but a boy, yet, as his father was a maker of

images, "it seems probable that both hereditary and early impression

went to quicken the sense of beauty in one whose genius was to give

form to exquisite visions of the antique world. Flaxman

himself has expressed a keen appreciation of the mission of the

artist-workman who had given England her cathedrals. So we may

feel sure he did not repine when for many years he himself wrought,

as in their ranks, furnishing designs for the pottery of Wedgwood.

Indeed, it was by these, and by his designs to illustrate the Iliad,

Odyssey, and other classic works, that he secured what modest

competency and what quiet fame fell to his share during his life.

Still, as a sculptor he did splendid work. The rewards of

fortune did not fall heavily on this gentle, modest man, with his

turn for mysticism, and his winning face. But he was happy in

his home life, happy in his work, happiest of all because it seems

quite true, as is stated on his grave in St. Giles-in-the-Fields,

London, that "his mortal life was a preparation for a blessed

immortality."

York and its minster had not suffered much at the

Reformation. But most of the abbeys of Yorkshire were thrown

in ruin, and the "religious houses" swept away. After the

wreck of the "Old Order," there was an interval of moral chaos.

The most spiritual and earnest men of both churches had been weeded

out by the alternating persecutions. As a thoughtful writer

says, it was in the main the ignorant, the luke-warm, the

time-serving or the weak, who kept their stations, and performed the

old service or the new with equal obedience; many, indeed, with

equal indifference. "The number of the secular (or parish)

clergy was about nine thousand and four hundred, and of these

scarcely two hundred were deprived by the establishment of the

Church under Queen Elizabeth; the rest 'conformed' again as they had

already done under Queen Mary." This state of things, while it

probably gave rise to much of the wilder fanaticisms of the brief

Puritan rule, was scarcely bettered by them. At the

restoration the Church's property for educational and charitable

purposes was utterly misappropriated. Her learning, too, was

at a low ebb, and her personal holiness at a lower, though at the

same period she could boast of exceptional men of great piety and

erudition.

The Church of that period was unable to awaken the educated

classes from worldly pursuits and vanities, and it entirely failed

to reach the greater part of the nation, who remained totally

ignorant, rude, and brutal. Changes of "creed" had generally

been a mere matter of politic submission, and real Christianity was

unknown. We need not go farther than the art and literature of

the period for confirmation of all this. What then was likely

to be the state of matters in the then well-nigh savage solitudes of

Yorkshire?

It was not wonderful, therefore, that Yorkshire was one of

the places which yielded rich fruit to the devoted labours of

Whitefield and Wesley. It is scarcely fair to lay upon those

preachers the onus of the extravagances into which some of their

early followers fell. Rather such may be attributed to the

dense ignorance and animalism in which the bulk of the population

had been left, so that their minds and hearts could scarcely be

reached without producing some morbid psychological paroxysm.

As Shakespeare says:—

|

"Diseases, desperate grown,

By desperate appliances are relieved,

Or not at all." |

It is significant that abnormal manifestations seldom

attended the spiritual awakening of those who had been well

brought-up, surrounded by good influences, and fairly amenable to

them. Many such, rather readily responsive to the new teaching

than startled by it, were found among the Yorkshire converts.

One of these was George Story, whose boyish nature had been so

tender that he awoke o' nights regretting a stone he had thrown at a

bird, who devoted his youth to self-improvement, and who had the

keen insight to ask himself at Doncaster Races, "What is all this

vast multitude assembled here for? To see a few horses gallop

two or three times round the course as if the devil, were both in

them and the riders! Certainly, we are all mad if we imagine

that the Almighty made us for no other purpose but to seek happiness

in such senseless amusements."

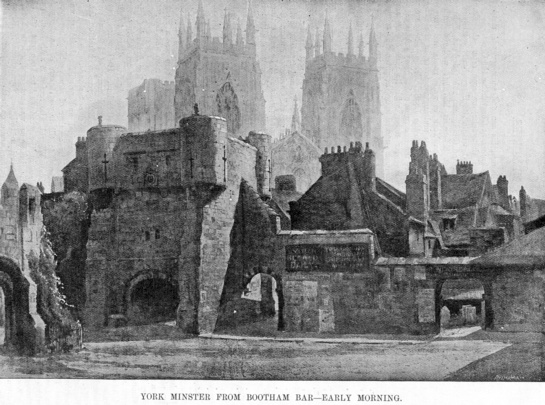

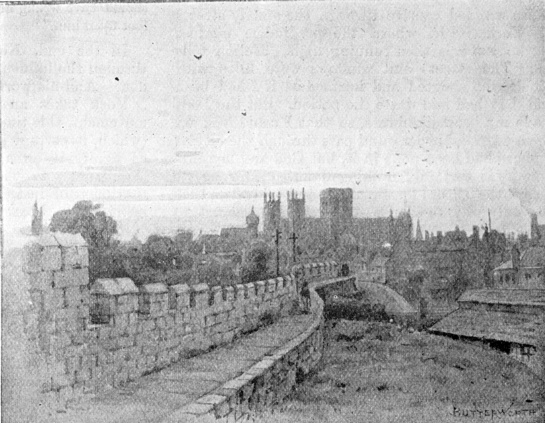

York Minster from the walls.

Yet all the while he had been aware of a sense of spiritual

loneliness. He did not know his Divine Father, still less was

he at one with Him. Yet he was in that mood of diligent search

for the haven of peace, when any ugly thing will serve to warn off

the rocks, even if it can scarcely point to the harbour. The

life of Eugene Aram, executed for murder in Yorkshire (the story of

whose "Dream" has been told

by Thomas Hood), came to Story's band in the ordinary course of his

printing business, and he took to heart that Eugene Aram's

intellectual acquirements, such as he himself was seeking, had not

sufficed to save him from theft and murder, and that therefore such

matters, however desirable, were no end in themselves. It is

pleasant to know that it was at his mother's request that Story

began to attend the Methodist meetings, at which he resolved to

devote himself and his life to God's service. In his humility,

he was rather troubled and fearful to find he did not pass through

the throes and ecstacies he saw in so many about him. But in

the end he entered into "an ever-permanent peace which kept his

heart in the knowledge and love of God."

There is rather more stir and romance in the story of another

Yorkshireman, one of Wesley's earliest lay-preachers. John

Nelson heard the great preacher, while in London, engaged as a mason

on the building of the Exchequer. John was evidently an

emotional and impressible man, and he felt as if Wesley had made a

direct appeal to him. He said to himself "This man can tell

the secrets of my heart." A change in Nelson was soon manifest

to his acquaintances, though as a biographer says "in all his inward

conflicts there was in his outward actions a coolness and steadiness

of conduct which is the proper virtue of an Englishman." The

following incident may illustrate how John's change was manifest.

"He risked his employment by

refusing to work at the Exchequer on a Sunday, when his master's

foreman told him that the King's business required haste, and that

it was common to work on the Sunday for his Majesty (George II.)

when anything was upon the finish. But John stoutly averred

that he would not work upon the Sabbath for any man in England,

except it were to quench fire, or something that required the same

immediate help. 'Religion,' said the foreman, 'has made you a

rebel against the King.' 'No, sir,' he replied, 'it has made

me a better subject than ever I was. The greatest enemies the

King has, are the Sabbath-breakers, swearers, drunkards, and

whoremongers, for these pull down God's judgment both upon King and

country.' He was told that he should lose his employment if he

would not obey his orders. His answer was, 'he would rather

want bread than wilfully offend God.' 'What hast thou done?'

asked the foreman, 'that thou needest to make so much ado about

salvation? I always took thee for as honest a man as any I had

in the work, and could have trusted thee with £500.' 'So you

might,' answered Nelson, 'and not have lost one penny by me.'

'I have a worse opinion of thee now.' said the foreman.

'Master,' he replied, 'I have the odds of you, for I have a much

worse opinion of myself than you can have.' But the end was,

that the work was not pursued on the Sunday, and that John Nelson

rose in the good opinion of his employer."

But it is not always thus, and those who stand on any

principle must do so prepared to pay the price. John was not

called to any martyrdom then nor even when he returned to his

Yorkshire home and opened his new views to his own household.

Indeed, the first great trouble of his religious life seems to have

been the mandate which made him a lay preacher. He said he

would rather have been hanged on a tree, and once, when a great

congregation awaited him he ran away to the fields. John

Wesley soon recognized his value, and indeed it is likely that

Nelson's success decided the scheme of Methodist lay-preachers.

But John was soon to suffer tribulation enough. In his

native village, an ecclesiastic and the publicans, indignant that he

drew away the congregation of the one and the customers of the

other, agreed that he should be pressed for a soldier, according to

then existing methods of involuntary enlistment. He had to

learn what it is to have one's protests ignored and snubbed by those

in authority, what it is to have to sleep in dungeons though not

without such consolations, divine and human, as may have attended

the early Christians themselves.

He was led captive through the stately streets of York

itself, where the predjudice against Methodism was then running

high. Nelson tells us: "The streets and windows were filled

with people who shouted and huzzaed as if I had been one that had

laid waste the nation. But the Lord made my brow like brass,

so that I could look on there grasshoppers, and pass through the

city as if there had been none in it, but God and myself."

John was certainly nothing daunted; for he rebuked the officers for

swearing, and told them that the only way to silence such rebukes,

was not to swear in his hearing. He told them that he would

never fight, because it was against his way of thinking. If

they forced him to bear arms, he would bear them "as a cross," but

that nevertheless unless he were discharged lawfully, they might be

sure he would not run away.

St. Mary's Abbey.

In short, they presently found that all they had done was to

secure Methodist preaching for the regiment! When the ensign

told him with an oath that he would have no preaching or praying

there, John replied: "Then surely, sir, you ought to have no

swearing or cursing either: surely I have as much right to pray and

preach as you have to curse and swear." This ensign annoyed

John in every way he could. One cannot like the stalwart

Yorkshire mason less because he candidly confesses:—

"It caused a sore temptation to

arise in me to think that an ignorant, wicked man should thus

torment me—and I able to tie his head and heels together! I

found an old Adam-bone in me: but the Lord lifted up a standard,

when anger was coming on like a flood: else I should have wrung his

neck to the ground, and set my foot upon him."

In the end, Nelson's discharge was secured through the

influence of the Countess of Huntingdon. And his work went on.

York takes an honourable place in another movement, this time

of direct social amelioration (which, important in itself, is still

more important as signifying an uplifting of the general moral

standpoint), to wit, the humane and scientific treatment of

insanity. The pioneer in this movement was a French doctor

Pinel, and all credit must be given to the National Assembly of

France, who amid the heat and frenzy of the Great Revolution, gave

him every encouragement and furtherance. Almost

simultaneously, the same movement was made by William Tuke, a member

of the Society of Friends in York. We may mention that George

Fox was once a prisoner in York castle, and his Society has always

been, and still is, an active power in the city, having a large

meeting-house in Clifford-street, and adult Sunday-schools and other

agencies in the poorer parts of the city.

Previous to the time of Pinel and Tuke, therefore up to the

very end of the last century, society had recognised no duty towards

the insane. The unfortunate lunatic was unnoticed, unhelped

and unguarded, until such time as his state had become hopeless and

dangerous, when he was loaded with chains and flung into a madhouse

dungeon. Even there his misery was exposed to the heartless

mirth and cruel baiting of the public. While the last scene of

Hogarth's Rake's Progress shows what the interior management of a

madhouse used to be, partial convalescents were turned out of doors,

labelled, to wander and beg. The very "medical treatment" of

these unfortunates consisted of exasperations which might well have

driven the sane into frenzy. So many "lashes" were prescribed,

or "surprise baths" or "rotating chairs." The attendants, few

in number, were generally the lowest and worst of mankind.

In Great Britain, therefore it was William Tuke of York who

inaugurated an order of things at once more scientific and more

humane. It was he who began to show that insanity in itself is

a disease and not a crime, and that all the patient needs is the fit

regimen and the proper amount of seclusion calculated either to

bring about his cure, or to prevent him from being a torment or a

risk to society. In learning to regard insanity as an

affliction to be assuaged and not a crime to be punished, people

ceased to conceal it, and it became, at least in its acuter

manifestations, more amenable to treatment.

The "Retreat," Tuke's Asylum, which thus has the honour of

being the first in which the humaner principles were applied, is on

the Neslingden Road, outside Walmgate Bar. Returning to the

heart of the city we pass under the Walmgate and follow a long,

irregular old street, now in somewhat "reduced circumstances," but

still rich in fine old churches. We notice a quaint and

picturesque Merchants' Hall, approached through an archway,

surmounted by a brilliantly-coloured coat of arms and bearing the

motto "God give us good adventure." Out of the old streets,

branch many narrow passages opening into little courts, some

surrounded by tidy family dwellings, and others by the little

almshouses of some of the charitable foundations with which York

abounds.

Indeed, though the minster will always remain the crowning

glory of York, yet it has many other interests and is full of

picturesque "bits." Besides the Walmgate its other four old

gates still stand—the Monk Gate, "most perfect specimen of this sort

of architecture in the kingdom, the Mickle Gate, ending an old

street of noble proportions, and many stately houses," Fishergate,

dating from the fourteenth century, and Bootham Bar, beside which we

find the quaint old Manor House, where kings have lodged and where

the blind are now sheltered and trained, while hard by stands the

Yorkshire Fine Art and Industrial Institution, with a good permanent

gallery, and excellent accommodation for loan collections.

Before we passed Bootham Bar we had noticed a Girls' Training

Home. We had not passed it far before we came on the buildings

of the Salvation Army, and in the same street we saw a boy in the

uniform of the newspaper brigade. The Christian Associations

of young men and young women are also in full evidence.

The churches of York are numerous, and most of them are

interesting for their antiquity, their architecture and for the

delightfully restful old-world air which surrounds them. Every

dissenting denomination seems represented in the city, and generally

by large and handsome houses of worship. The chief municipal

buildings, including the fine old Guildhall, are to be found in

Coney Street which is the favourite shopping promenade. Almost

all the streets of old York can delight the eye of the artist and

the heart of the dreamer. They have some old mansions too,

which seem the ideal dwellings of "merchant princes." But,

alas, in the newer and humbler outskirts we find too much of the

petty monotonous uniformity which seems the special architectural

feature of the present century.

Still, the memory we carry from York is of turret and tower,

gable and gate, as we beheld them, either from her old walls, or

when resting under the stately trees beside the quiet Ouse.

ISABELLA FYVIE MAYO.

Note.

Fire has seemed to be the evil genius of York Minster. Even in

the present century it has suffered severely. One

conflagration, the work of a maniac, cost £65,000 to repair.

Another arose from the carelessness of a workman.

――――♦――――

|

(from The Sunday at Home, annual edition, 1898-99,

The Religious Tract Society.)

_______________

|

THERE are certain

corners of England, quiet enough now, whose quietness makes us

realise how the course of national life may change, and how it seems

to be mercifully inevitable that battle-grounds shall blossom into

cornfields and meadows, and that the peaceful ploughshare shall turn

up the rusted weapons of the forgotten warrior.

There is perhaps no part of England that is to-day more

peaceful in aspect than those rich agricultural counties often

grouped together under the name of the "Fen Country." Two of

the most sympathetic poets of our time, Alfred Tennyson and

Jean Ingelow, have been laureates

of this land, and have stored our consciousness with imagery of

"haunts of ancient peace," and of "cowslip time when hedges sprout."

Even the tragedies of these poets are but of the silent heart-agony

of "Mariana" in the lonely grange with its shivering poplar, where

|

"For leagues no other tree did mark

The level waste, the rounding gray," |

or of the great unmalicious forces of Nature, as when the "High

Tide" comes up—

|

"And boats adrift in yonder towne

Go sailing up the market-place." |

Yet these peaceful fields have been the scene of battles as

fierce and wild as any; and these placid lowland agriculturists must

mingle in their veins the blood of forefathers of varied and warlike

races, who, each in its turn, surrendered the land to a new invader.

From the very beginning of British history this Fen country

had been a point where stand was made against invasion. There

the ancient Britons rallied against the Romans long after the rest

of the country was subdued. Here, when the Roman power was

fading, the British made another stand against the Saxons; and

again, when the Saxons were incorporated with the native race, it

was here they withstood the onslaught of the Danes, and when the

Danes in their turn had settled down in the land, had intermarried

with Angles and Saxons, and rebuilt the stately abbeys which their

sires had destroyed, here, once more, was the last unavailing stand

made against the haughty Norman conquerors.

In its natural aspects the fen country is very different from

what it was in those dark and stormy days, and indeed it had passed

through changes even then. The Romans found it a great swampy

jungle within the compass of whose marshes and quagmires lay many

veritable inland islets—as the Isle of Ely itself—slight elevations

often surrounded by water, but never covered by it, and so offering

favourable situation for camps or temples. The Romans seem to

have cut down much of the forest, and they drove one of their great

roads through the heart of the country, probably on the line of some

rude British highway. They raised certain embankments to

protect this from the waters, but when the Romans went away the

waters reasserted themselves despite such efforts as the successive

Saxons and Danes might make in those distracted times, and in due

course the whole district lapsed back into morass. No

effectual method of dealing with it by drainage seems to have been

attempted till the reign of Charles I., and even then the work

proceeded with many interruptions, and was not perfected till

comparatively recent times [Ed.—see Samuel Smiles on

Telford].

Before this, locomotion in the fens was often accomplished on

stilts; and the fens boys still love to play at walking on these—the

necessity of their forefathers having become their pastime. A

local authority says that the only piece of "real old fen" existing

at the present day "is is found near Burwell, south of Ely and east

of the Cam."

The traditions of the early British fen dwellers are lost in

the mist of the past, and our first defined knowledge of the place

belongs to the Saxon period. It was a Saxon princess

Etheldreda, who founded the first conventual church of Ely.

Etheldreda was twice married, and the "Isle of Ely" came to her

through her first husband. She spent many of the last years of

her life in the cloisters which she attached to her foundation,

numerous servants and retainers following her to its retirement.

Undoubtedly the site of Etheldreda's conventual establishment

had been originally selected from the same considerations which

afterwards directed the foundation of the neighbouring establishment

of Ramsey, concerning which the antiquarian Sharon Turner gives us

many interesting particulars in his "History of the Monk of Ramsey."

To ecclesiastical promptings that a monastery should be founded in

the district, the Saxon "ealdorman," the elder of the local tribe,

commended a site on Ramsey, in the following terms (most of which,

it will be seen, would have been equally applicable to Ely).

He had, he said, "some hereditary land surrounded with marshes, and

remote from human intercourse. It was near a forest of various

sorts of trees, which had several open spots of good turf, and

others of fine grass for pasture. No buildings had been upon

it save some sheds for his herds who had manured the soil."

The bishop and the landed proprietor went together to view the land.

"They found that the waters made it an island. It was so

lonely and yet had so many conveniences for subsistence and secluded

devotion that the bishop decided it to be an advisable station.

Artificers were collected. The neighbourhood joined in the

labour. Twelve monks came from another cloister to form the

new fraternity. Their cells and a chapel were soon raised.

In the next winter they provided the iron and timber and utensils

that were wanted for a handsome church. In the spring amid the

fenny soil a firm foundation was laid. The workmen laboured as

much for devotion as for profit."

This circumstantial account of the growth of Ramsey would

doubtless serve equally well for that of its earlier neighbour at

Ely, and of many another religious establishment of that time and

district. Some of these have totally passed away, while others

linger in ruin, and only a few, like Ely, have cast roots so strong

that they can adapt themselves to changed conditions and still hold

their own in our national life.

The tomb of one of Etheldreda's attendants, Ovin her steward,

is now to be seen in Ely Cathedral. It was found, some years

ago, in a neighbouring village where it had been used as a horse

block. As it is now it shows the lower portion of a stone

cross with a pedestal round which runs a Latin inscription in Roman

characters (save for the Saxon E). Translated it reads,

"Grant, O God, to Ovin Thy light and rest." It appears that

Ovin is a "Welsh" name, which means a name of aboriginal Britain,

and it is likely that when Ovin followed his mistress to Ely, he, or

at least some immediate ancestor, was not a stranger there, since

aboriginal Britons had held Ely long after the Saxons had taken hold

of most of England.

Bede tells us that Etheldreda was in the habit of spending

her nights in prayer; that she took only one meal daily; and among

other proofs of her sanctity he mentions that she never wore linen,

but only woollen. It is significant that nineteenth century

sanitary wisdom would certainly recommend this attire in the damp

climate of the Fens, where in winter, or wet seasons, the rivers

still overflow the "Wastelands" and give the local people

opportunity to become the fleetest skaters of the land. There,

too, in the olden days the blue lights of the "Will o' the Wisp,"

flitting over the marshes, must often have added the superstitious

horror of fiendish presence to all the other miseries of poor

fugitives, plashing in the damp earth, and hiding from their foe

amid dank reeds and rushes, or at best groping in their little round

huts, scarcely yet modified from those of the ancient

Britons—beehive in shape, windowless, with a hole in the roof to let

out the smoke.

What havens of light and warmth and safety the great monastic

houses must have seemed in such times! In their imperfect way

they stood as outward signs of the spiritual shelter to be found in

the church of the living God, as well as of the strength and purpose

of the Saxon lawgivers. For whatever the limitations

inevitable to their period, and whatever the practical shortcomings

common to human nature, these had at least an ideal. The dawn

was with them. Even the Saxon kingship, though commonly

assigned within one family, was, within that range, subject to

election, the original purpose for which a king was chosen being

always kept in sight— to wit, that he should be a person capable of

carrying on the government and of conducting the enterprises of the

nation. Large tracts of land remained public property—the

"folks-land"—the few "common-lands" of the England of to-day being

the poor remnants of this, the remainder having been converted into

"crown-land " under the feudal spirit of Norman conquest.

Saxon legislation, as traced to the time of Alfred, was laid

down, theoretically, on such lines as these: "Ever as any one shall

be more powerful here in the eyes of the world, or through dignities

higher in degree, so shall he the more deeply make compensation for

his sins, and pay for every misdeed the more dearly, because the

strong and the weak are not alike and cannot raise a like burthen."

And again, "Let every deed be carefully distinguished, and doom ever

be guided justly according to the deed, and be modified according to

its degree before God and before the world; and let mercy be shown

for dread of God, and kindness be willingly shown, and those be

somewhat protected who need it, because we all need that our Lord

oft and frequently grant His mercy to us."

It must be owned, however, that the Saxons frankly admitted a

mercenary spirit into their code. Almost every offence, even

murder, could be expiated by money. In the case of the death

or injury of a freeman, this "compensation" was paid to his

relatives; if the sufferer were a slave, to his master. It was

a more "costly" offence to deprive a man of his beard than of his

leg! Any offender who failed to duly "compensate" could be

made a slave. Anglo-Saxons could become slaves only in this

way, or by being sold in infancy by their parents. Also

anybody over thirteen years of age was free to sell himself.

Most of the slaves, however, were conquered Celts—aboriginal

Britons.

Etheldreda died, in 679, of an affection of the throat, which

tradition says she regarded as a "judgment" on her youthful fondness

for necklaces! It is surely a much more significant "judgment

"that her stately name of Etheldreda or "Noble Strength" has been

vulgarised into "Awdrey," and that her memory has been familiarly

perpetuated to more modern times by "St. Awdrey's Fair," at

which—possibly in remembrance of her feminine weakness—pilgrims used

to buy chains of lace or silk which had been laid upon her shrine

and which were called "St. Audrey's Chains." In time their

flimsy texture and gaudy colouring gave rise to the word "tawdry" an

attribute indeed at the opposite pole from "noble strength!"

Etheldreda, who had been the first abbess on her own

foundation, was succeeded by her sister and then by other Saxon

princesses. The district lay in peace, except for petty feuds

and minor incursions of Northmen, for nigh two hundred years.

Then in 870 came that awful Danish invasion which desolated England

early in the reign of the great Alfred. At that period the

Isle of Ely and its abbey fell into the hands of the fierce sea

warriors. The fare was burnt, and the inhabitants of the

establishment put to the sword.

After that no restoration was attempted for fully a hundred

years. Indeed, the Saxon kings who succeeded Alfred employed

the revenues of Ely for their own private purposes, some of them

still having Danish incursions to contend with. At last, in

970, the Bishop of Winchester, by direction of King Edgar, restored

the monastery. This King Edgar's character seems to have

gained a false gloss of sanctity through the mercenary gratitude of

his monkish chroniclers. For this "builder of churches," as he

was dubbed, was a thoroughly bad man, who did not scruple to violate

convents and to forcibly carry away unwilling women—a terrible crime

at any period of the world's history, but of appalling significance

at a period when the generally recognised sanctity of these retreats

made them the last and only hope of unguarded innocence or helpless

bereavement.

The abbey, as built at this Saxon period, is said to have

been a stately stone edifice crowned by a tower and a steeple to

guide wayfarers among the meres and swamps. It was put under

the rule of the Benedictine order, and from this time dates the

abbey's character for boundless hospitality, which was so extended

that during the troubles of the next century its demesne gained the

honourable name of the "Camp of Refuge."

Not long after King Edgar's death the new building at Ely

received a visit from his widowed Queen Elfrida (stepmother to his

son and successor Edward). She was accompanied by her own

little child Ethelred. The little prince, probably instigated

by his mother, vowed a special devotion to Ely's patron saint St.

Etheldreda, and doubtless there were many solemn services and much

stately pageantry. But all the time, two awful crimes were

crystallising in the breast of the dowager-queen, though she, as the

widowed mother of an only son, seemed doubtless rather a touch of

pathos on the brilliancy.

Elfrida's stepson Edward had succeeded to his father's crown

when he was thirteen. Ere he was seventeen he was dead,

stabbed in the back by one of his stepmother's servants while she

herself held him in courteous parley and gave him a cup to drink.

She was already guilty of the murder of Brithnoth, the first abbot

of Ely, which she had brought about with such diabolic cunning that

his corpse bore no trace of violent death, and her wicked deed would

have gone unsuspected but that when remorse finally overtook her for

her treacherous dealing with her light-hearted, loving step-son, she

confessed this crime also.

It is said that this traitor-like method of despatching

enemies or "obstacles," by stabbing them in the back while offering

them a friendly cup, became so common among the Anglo-Saxons as to

give rise to the custom of each one requiring another of the company

to be his "pledge," who, when he stood up to drink, should stand up

also, facing him drawn sword in hand, to protect him if required.

Such was the origin of a drinking practice which, in modified form,

persists to this day—which is, indeed, incarnated in the "loving

cup." For as each person rises and takes this in his hand to

drink the man seated next to him rises also, and when the latter

takes the cup in his turn the individual next to him does the same.

Alas! were we to search out the origin of many of the so-called

"fine manners and customs of the olden time" we should find them

rooted in the grim needs of elemental savagery!

Violent and cruel blood therefore mingled in the veins of

Elfrida's own son Ethelred, when his mother's crime thus set him on

the throne. When he could not succeed in buying off the

invading Danes, who perpetually harassed his coasts, he resolved to

massacre any of the race found throughout his kingdom. This

only drew down the invasions of the Danish King Sweyn and his son

Canute. The conflict ended in Canute's great victory in Essex

when "all the English nation fought against him," and all the

"nobility of the English race was there destroyed." Canute

soon found himself in almost undisputed dominion. But he

proved a conqueror of rare calibre for those days—perhaps for any.

For though he taxed the English people heavily to reward his Danish

followers, yet, on the human and social side, he proved himself a

wise prince, for he determined to reconcile the English to his rule,

and to this end sent back to Denmark as many Danes as he could

spare, restored and upheld Saxon customs, made no distinction

between Danes and English in the distribution of justice, but sought

to protect the lives and goods of all alike. He had his reward

in finding that presently his English troops went against his

enemies not only honestly but with loyalty and zeal. In those

days, when the king checked his flatterers by his famous object

lesson on the Sussex beach, or bade his rowers lift their oars while

he listened to the Ely psalm-singing, it seems as if English life

really had happier auguries than it had had since the later years of

Alfred the Great, or was to have again for many a long year

afterward.

Another pleasant incident connects Canute and Ely. It

appears that he went to visit the abbey at the beginning of February

in a hard winter when all the waters were frozen. The

courtiers, probably afraid for themselves, protested against the

monarch trusting himself on the treacherous ice. But Canute

declared that if only one bold fenner would go ahead to point the

way, he himself would be the next to follow. Such a fenner was

found in the person of one Brithmer, a serf, nicknamed the Pudding,

because he was so fat. When Canute, who was a small light man,

saw him, he said, "If the ice can bear thy weight, it can well bear

mine. Go on and I follow." And so they did, and so one

by one the courtiers plucked up heart and advanced also. Then

King Canute made the serf Brithmer a free man, and gave him some

land, which Brithmer's posterity held for many generations.

King Canute seems to have had a particular kindness for the

great church at Ely, for he brought his wife Queen Emma to visit it,

and she made rich offerings of jewelled embroideries at the shrines

of St. Ethelreda and the other saints.

A chequered and troubled life had this Queen Emma, and it may

serve as a type of many that must have been like it, more or less,

among humbler folk, in those difficult times. Emma was a

Norman princess, who, in due time, numbered among great-nephews no

less a personage than William the Conqueror himself. She had

been married in her youth to the cruel King Ethelred, who arranged

the massacre of the Danes. She was the mother of his children.

She must have had little sympathy indeed with her first husband, for

she seems to have had no hesitancy in becoming the second wife of

his triumphant conqueror Canute. She saw the sons of her Saxon

spouse set aside for her Danish son, in whose interest she

stipulated that her stepson, Canute's own eldest-born, should be

passed over also. Such a state of things could only lead to

fratricidal quarrel. After Canute's death, her eldest Saxon

son coming to claim his rights, was taken to prison and blinded, and

soon died in the monastery of Ely, in reach of the rich offerings

presented by his unnatural mother. Her own Danish son

eventually succeeding his Danish half-brother, loaded his

stepbrother's dead body with ignominy and hastened to oppress his

Saxon subjects. His speedy death made way for Edward the

Confessor, Emma's remaining Saxon son, who, resenting her treatment

of himself and his dead brother, deprived the queen of the enormous

wealth she had amassed, and obliged her to pass the rest of her life

in conventual seclusion.

Among her other strange experiences, she underwent a trial by

the ordeal of walking among hot ploughshares. By doing this

she was supposed to prove her innocence of whatever charge was

brought against her. But, as the test was in the hands of the

clergy, whose favour she had won by her immense benefactions, there

is little doubt that they had skill and cunning to arrange the

matter.

Such was the royal family history and one woman's career in

that stormy period. Yet terrible as were the deeds enacted,

these people were probably weak rather than wicked, and became great

criminals only by the strange complication of circumstances

surrounding them. To some of them their closing days in the

convent cell, even as prisoners, may often have been welcomed as a

quiet rest and a sure retreat, where they might at last enjoy

"A peace above all earthly dignities. . . ."

The next epoch in the history of Ely was the gallant stand

made by the English squire Hereward against William the Conqueror.

Kingsley's story of "Hereward the Wake" gives a graphic picture of

the times and their struggle, though it has been shown that the

noble lineage which he assigns to Hereward, and the domestic

circumstances with which he surrounds him, have no foundation in

historic fact. The abbey was finally surrendered to the

Conqueror by Abbot Thurstan, the capitulation being hastened, it is

whispered, by monkish impatience under the short rations imposed by

a state of siege. Hereward himself, with his men, had

previously succeeded in marching out, and eventually made peace with

William. The resistance of Ely, however, had been so stout

that the Conqueror dealt severely with it, stripping it of its

jewels and furniture, and dividing its lands among the Norman

nobles. In this matter, however, he soon met with an

unexpected check. The Norman monk whom he presently appointed

Abbot of Ely, insisted on the restoration of all the gold and

precious things. Norman knights and soldiers were quartered in

the abbey, sharing the refectory with the Saxon monks. It is

one more commentary on the little hatred which really exists between

races (save as promoted by ambitious leaders or evil governments)

that, despite all that had so recently passed, the Saxon monks and

their Norman visitors grew so friendly that when, by-and-by, the

Norman soldiery were withdrawn to fight the Conqueror's battles

against his own contumacious sons, the Saxon monks accompanied them

on their way with solemn song and procession, and they all parted

with mutual expressions of regret and goodwill.

The foundation of the present cathedral was laid at this

period, and parts of the Norman work still remain. In the

reign of Henry I. the first Bishop of Ely was appointed.

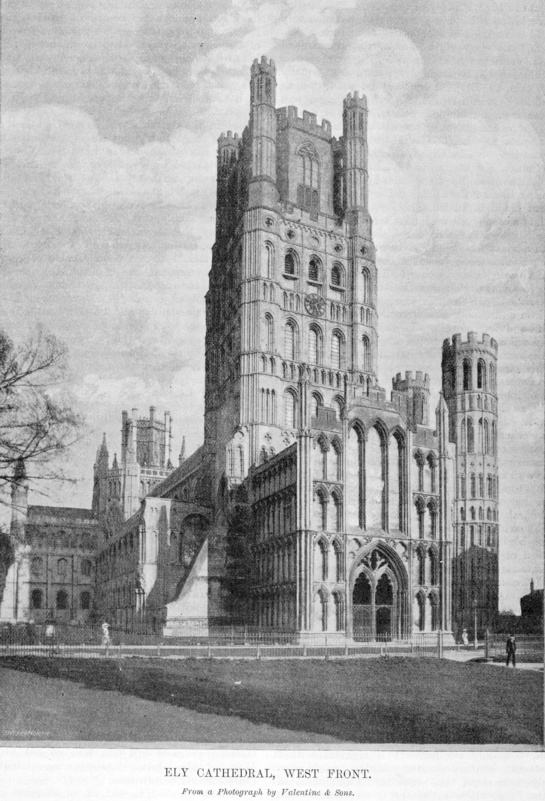

The cathedral, as it stands now, is said to completely

illustrate the history of Church architecture in England from the

Conquest to the Reformation. It is most interesting to note

the child-like simplicity with which some of the earlier builders

went about their work, caring nothing for the "symmetry and finish"

for which so much is sacrificed nowadays. Its special features

are its wonderful octagon tower, the "only Gothic dome in

existence," and its "lady chapel," both the work of the famous

ecclesiastic architect, Alan de Walsingham, who for some reason was

prevented by the Pope from becoming Bishop of Ely as the monks

desired. The "lady chapel," now known and used as Trinity

Church, is but the very wreck of its former self. Of the

innumerable careen figures which once adorned it, all suffered

damage at the hands of Cromwell's soldiery. One only remains

entire. The sacrist said it represented Philippa, queen of

Edward III., and that other effigies of hers elsewhere had likewise

escaped injury. This chapel was once as gorgeous in colouring

as in carving, but as Cromwell's troopers chipped it, so somebody

else has whitewashed it!

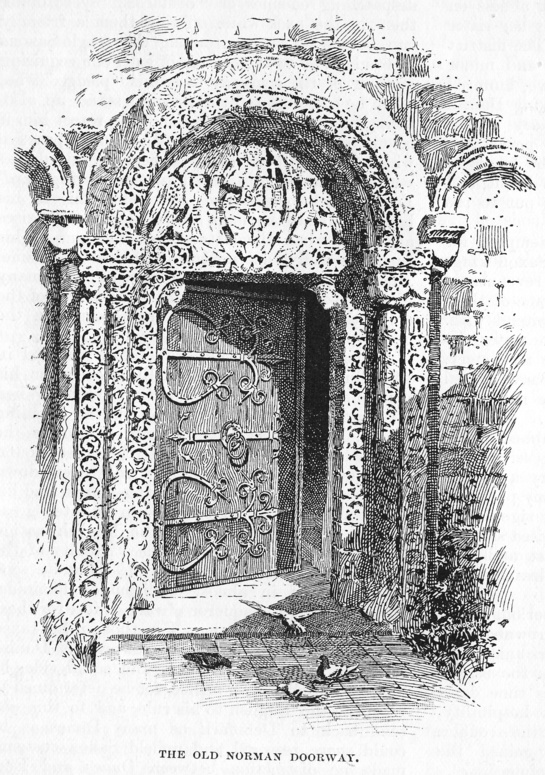

Another object of great interest is an old Norman doorway,

formerly the prior's entrance from the cloisters. It is richly

decorated on the exterior. Above the door are figures of the

Saviour with two angels, while at each side are three pilasters

covered with running foliage and with medallions containing figures

of flowers, birds, animals, and even scenes of human life, in some

of which the old-world sculptor has indulged a sense of humour, as

in the one near the ground, where a man and a woman in a boat are

rowing different ways!

The cathedral contains memorials of many people, especially

ecclesiastics, famous in their day, but whose names mean little now.

Among the bishops of Ely, however, are two of whom it is worthy of

remark that words of theirs have grown familiar to millions who have

never heard of the men themselves. Thomas Goodrich, who was a

zealous promoter of the Reformation, and was Bishop of Ely from 1534

to 1554, was the compiler of those two statements as to our duty to

God and our duty to our neighbour, which give such a practical and

universal value to the English Church Catechism. He seems to have

been devoted to the labours of his see. He built a gallery

between the cathedral and the bishop's palace opposite the west end

of the cathedral, so that he might readily pass to and fro.

The gallery no longer exists, though it has given its name to the

road that it crossed. The front of the palace still bears the

arms of Bishop Goodrich, supported on either side by panels carved

respectively "Duty towards God," and "Duty towards our neighbour."

It seems but appropriate that the exquisite prayer "for all

sorts and conditions of men" was composed by a bishop of the

district which had been the "camp of refuge" for Briton, Saxon,

Dane, and Norman. The large charity which commends to God's

fatherly goodness "all those who are in any ways afflicted or

distressed, in mind, body, or estate," makes Bishop Gunning seem as

a personal friend, to each of us, since all of us are folded in his

prayer.

The precincts of the cathedral are full of interesting

buildings, of which the most remarkable is a little Norman chapel

dating from about 1321. For many years it was left neglected,

choked by three floors which were inserted to be used as

store-places. It has now been put in order and carefully

preserved, though its windows have been filled with stained glass

containing figures so heroic in size that they seem to crowd up its

tiny dimensions. It is used as the Chapel of the Cathedral

Grammar School, to whose purposes other of the monastic buildings

are now devoted, among these the stately old porter's lodge, dating

from a hundred years later than the little Norman chapel.

Ely itself is a quiet sleepy place; all its life, wealth, and

culture, are evidently concentrated in its glorious cathedral, which

dominates the landscape. Beyond the little green opposite the

west front we find the parish church of St. Mary, almost as old as

the cathedral, though it does not seem to have been allowed to

gather to itself the softening graces of antiquity.

As we wandered in the rather dreary churchyard, we caught

sight of a tablet outside the church, whereon we read the following

inscription:—

"Here lye interred in one grave, the bodies of

William Beamiss, George Crow, John Dennis, Isaac Henley, and Thomas

South, who were all executed at Ely on the 28th June, 1816, having

been convicted at the special assizes holden there, of divers

robberies during the riots at Ely and Littleport in the month of May

in that year. May their awful fate be a warning to others."

That slab serves a good purpose for which it was not

intended. It is a milestone to show us how far both

legislation and public feeling have advanced in the course of the

century. We have ceased to hold life forfeit for theft of any

kind. Nor can we help remembering that at the date in

question, the necessitous classes were driven well-nigh to despair.

For, owing to continental wars and unfavourable seasons, food was at

its very dearest. Trade was bad, and the number of unemployed

was increased by discharged soldiers and sailors, already trained in

deeds of violence. Machinery had just appeared on the

industrial stage, to the further bewilderment of the worker, who

could see in it only a mysterious entity which snatched from his

mouth the bread which was already but too scanty. The country

was lit by incendiary fires, and the manufacturing towns resounded

with the smashing of machines yet such crimes were little more than

the inarticulate expression of unutterable misery. Says a

popular song of that day:—

|

"Father clemmed thrice a week,

God's will be done!

Long for work did he seek,

Work he found none.

Tears on his hollow cheek

Told what no tongue could speak:

Why did his master break?

God's will be done!" |

But apart from the capital punishment for robbery—and apart

from the evidently entire lack of consideration of the dire need and

bitter oppression which "drives men mad"—let us dwell for a moment

on the spirit which could put up such a "warning " to meet the eyes

of those who approached to worship God—gentle old folks, happy

children; perhaps some woeful creatures akin in blood or love to the

men who had perished on the scaffold! But no; for how could

such come near that slab? God's house would be henceforth

closed to those who most sorely needed its shelter and its rest.

Did the people who put up that awful monument—well-intentioned

people, probably—ever think of the closing scenes of the Master's

life? Did they remember that His latest words to humanity were

spoken to a dying thief, and that the thief, guilty as he was, could

understand and love Jesus, when the priest and the Pharisee saw in

Him but a pernicious destroyer of public peace?

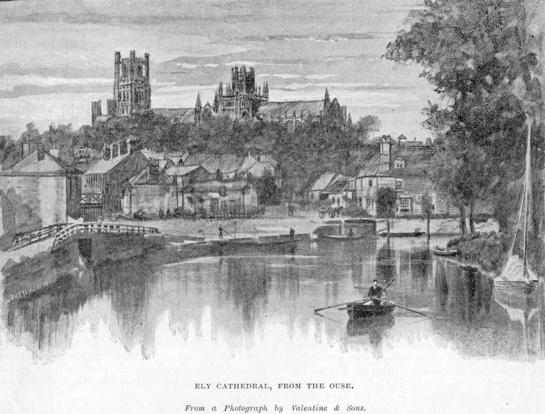

The thought of "man's inhumanity to man," casts its shadow

over us, as we wander down among the soft green meadows till we

reach the riverside, whence the cathedral looks fairest and

stateliest as it lifts its noble towers above the red-roofed

housetops. We have been spending time among memories and

monuments of storm and struggle, of the darkest passions and keenest

agonies. We see that even the very "Camp of Refuge," blessed

as it must have seemed to many a poor wanderer, could offer no

sanctuary from all the worst evils that beset human life and

character. But after all, God knew them all and each—each of

those poor fugitives, each of those hunted, bewildered women.

He could "comfort and relieve them, according to their several

necessities He could give them patience under their sufferings, and

a happy issue out of all their afflictions." Sitting there in

the spring sunlight with the silver waters spreading wide around, we

could pray.

"Remembering others as we have to-day

In their great sorrows, let us live alway

Not for ourselves alone, but have a part

Such as such frail and erring spirits may

In Love which is of Thee, and which indeed Thou art!" |

I. FYVIE-MAYO.

――――♦――――

|

|