|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER IX.

AB'S FIFTH LETTER TO HIS WIFE CONTINUED.

"MISS KITTIES " AND RAPIDS.

I NEVER wur so

loth at leeavin a shop as I wur when we left owd Roslie's. Everythin

wur so nice and quiet, an' dreamy. Somebody said it wur like "lotus

atin," tho' what that is I dunno' know, as I never tasted any. I

think th' house, an' th' londlort must have had summat to do with

it, becose after Niagara there's nowt to be seen outside. No bits o' neezlin country like "Daisy Nook;" nor wild, tumblin mooreland like

"Bill's o' Jack's." Booath Ameriky an' Canady are short o' that, or

they're so far out o'th' road o' one another. O about Niagara for

miles is as flat as owd Thuston's "five acre." But there must be a

ridge or two somewheere—happen thousands o' miles away, for t' bring

as mich wayter t'gether as would drown o England, Scotland, an'

Wales, besides makkin pigs an' potatoes very scarce i' Paddy's-land. Little as there is to be seen after th' Falls, an' th' river, I mun

say ut I strapped my bag wi' a heavy heart that 15th o' May, when

we'rn gettin ready for crossin Lake Ontario, an' on to Quebec; a

passage that would tak us two days an' two neets, if we didno'

break our journey at Montreal. Owd Roslie went with us to th'

station, for t' see us off; an' th' partin wur like a feyther sendin

four of his lads off to some war or other. I noticed that he'd summat under his arm ut wurno' exactly like a pair o' shoon; an'

when he honded it into th' car we fund it wur a bottle o' brandy.

Another an' another shakin o' honds, an' again we'rn rowlin past

miles o' ugliness i'th' shape o' snake fences; an' thousands o'

acres o' lond ut no mon could swing a scythe on for stumps o' trees

an' boother stones. We seeted Lake Ontario about twelve o'clock,

after we'd passed Hamilton; an' I thowt surely we'd gettin to th'

sae-side, it's sich a size; an' yet it's leeast o'th' four lakes ut

are drained into th' St. Lawrence. We could see ships on it wi' ther

white sails, lookin as busy among it as if they'rn floatin about th'

Bell Ship, outside Liverpool. About one o'clock we rowled into

Toronto, wheere we'd another sniff o' that cuss o' any country

wheere folk are born wi' noses, petroleum. Lors a-me, how we'rn

poisent! We didno' think at stoppin at Toronto for moore than a

halt, till we fund it out we couldno' get on as we wanted. Ther no'

boat across th' lake till Monday, an' this wur Setturday. We should

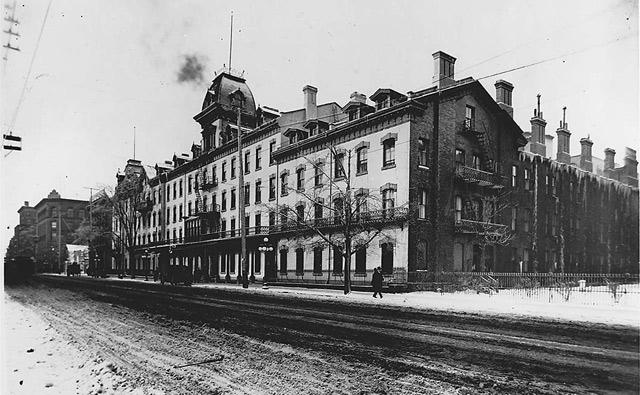

ha' to string up our clooas-line till Sunday wur o'er. We bundled of

to Queen's Hotel, wheere ther one comfort—we hadno' to goo upstairs

to bed, an' th' weather wur gettin above warm.

|

|

|

Queen's Hotel, Toronto (ca. 1856-1927).

Source: City of Toronto Archives. |

I rayther liked Toronto. Th' streets are moore like what we seen i'

Manchester than any we'd met wi'; an' th' folk, somehow, wur of a

gradlier pattern than any we'd seen sin we left Paterson. Th' women

wurno' so mich like paesticks as they are i' New York; an' th' owd

fashint sort o' slippers an' white stockins could be seen anywheere. If we hadno' to walk upo' plank "side-walks," an' could ha' yerd a

bit moore English spokken, I should ha' thowt we'd bin i'th' owd

country.

Hardly knowin what to mak our time away with, as we hadno'

calkilated upo' stoppin theere, we thowt we'd do a bit o' sailin on

th' lake. So we'd six cents apiece wo'th on a steeamer, after lunch,

an' sailed to an island ut they co'en th' "West Point." But th' sail

wur everythin.

I'd a bit of an exparience afore I geet on board

again ut I didno' expect, an' I'm sure never bargained for. We'rn

watchin th' marlockin of a racoon ut wur cheeaned to a stump, when o

at once Will o' Jimmy's gan a jump, an' off he darted, shoutin—"Yo'n

be bitten to deeath; yo'n be worried." What with? I wondered. Th'

racoon couldno' get to us; an' if it could I should hardly ha' thowt

ther any worryin power about it. I looked for snakes, but could see

no signs o' one o' thoose pleasant companions about an' lions an' tigers wur out o' question.

"What is there?" I shouted, when he'd stopped. Th' tother chaps

could see nowt, noather.

"Miss Kitties," he shouted back.

"Wheer are they?"

"Thou'rt among 'em now."

Whether Miss Kitties crawled or flew I'd never read, nor bin towd;

so at fust I looked about my feet, expectin to see summat about th'

size of a frog. But seein nowt theere I looked up, as ther mit be

summat about th' size of a wasp buzzin about. I could see nowt

nobbut a cloud o' midges theere. But Sammy o' Moses's had his

fingers in his neckhole; an' ther one or two beside him wur doancin

about. He must ha' catcht one, or elze one had catcht him.

"I see nowt nobbut these midges," I shouted to Will.

"Thou'll feel summat e'ennow," he shouted back. "They'n gi'e thee

midges, if thou'll be hard."

An' they did. Ther one geet howd o'th' back o' my ear, an' fairly

twisted me round. I feel sure it sent its gimlet reet to th' booan

fust delve. I slapt my hont upo' th' spot in a crack, but could feel

nowt. It must ha' struck its borin machine so far into my neck

timber that th' little dule's body, wings an' o, must ha' gone with

it. I'd very nee as lief have a hummabee drillin holes int' my husk

as one o' these Miss Kitties. Thou "guesses" reet—I did gie mouth

above a bit, for this one I felt wurno' th' only hand on th' job. Ther two or three coome a-helpin him; an' th lot on 'em wur workin

piecewark. Ther others had kest anchor i' my companions' necks; an'

they'rn talkin blue leetenin as weel as me. We cleared away fro'

that spot i' double quick time; an' we took care it should be th'

last visit.

A blanket-jumper is a great neet disturber, an' an enemy to dreeams. Sometimes one 'll put th' stopper on a neetmare. Then it's o' some sarvice. But these Miss Kitties are as bad as th' neetmare, for they

carryn a band o' music wi' em, an' never stoppen playin till they'n

buried their instruments in a piece o' fresh beef. Then they're so

fond o' fire they'n ate a lamp leet up before thou could blow it

out. I're towd a tale about two Irishmen i' Newark ut slept t'gether,

when they could sleep, an' they're so bitten they could hardly get

their clooas on. Someb'dy advised them t' go to bed without lamp,

becose wheet a leet wur th' little varmints would come i' clouds. They took th' advice, an' one neet they groped their road upstairs,

an' into their chamber. Before gettin i' bed they oppent th' window,

so ut if there wur any Miss Kitties on that particular huntin-ground

they'd have a chance of gettin away. These chaps had hardly getten

under cover when they yerd th' band comin, hummin away like fifty

peg-tops. This visit they didno come by theirsels. Ther a regiment

o' leetenin-bugs wi' em, flashing about like Billy. One o' th'

Irishmen seeing these, roars out to th' tother, "By jabers, Mick,

but the little divvels are bringing their own lanthruns wid 'em!" As th' Yankees say'n about a spree, they'rn havin a

hee owd time on't.

I'm just thinkin, Sal, ut if a woman had as mich stingin power, i'

proportion to size as a Miss Kitty has, a lot o' chaps would be

peggin off to oather one wo'ld or another, an' no' gi'e theirsels

time to look their clooas up, or calkilate what th' journey would

cost, or whether ther a chance of a sattlement.

Th' Canadians are like th' Yankees, they takken a great pride i'

their buryin greaunds. They never seem to be happy till they'n

getten someb'dy under th' clod. Then dunno' they show off? Nowt no

commoner than white marble. An' if there's a nice spot o' ground anywheere they're dot it o'er wi' moniments

whether any-body dees

or not. An owd bachelor ut's nob'dy to rejoice o'er, and spend moore

dollars than tears on, buys a "lot" for hissel; puts his own

moniment up; an' gets so used to gooin a-lookin at it, an' comparin

his show wi' thoose of his neighbours, that he actily thinks he's

deead.

I've bin led to think this by a pleasant droive we had after we'd

londed fro' th' lake. It wur a nice bit o' country just outside th'

city. Th' grass wur actily green; an' ther even green hedges. It wur

as mich different to bein upo' th' island as our house would be if I

showed thee a suvverin after thou'd thowt I'd spent it.

"Thou'd hardly think ther a bit o' country like this outside

Toronto," Sammy o' Moses's said, as we trotted on. "Speshly after

what we'n seen on th' lake."

"Nawe," I said, "it's very nee as nice as some parts o'th' owd

country. I'll be bund t' say we shall see a cemetery afore lung."

"That's just what we shall," Sammy said, "we're at one now," an' he

pointed out o' his side o'th' "buggy" to a place ut wur fairly

snowed o'er wi' marble.

I dunno know how it comes about, but we go'en into these places wi'

a different feelin to what we carryn with us into an owd English

churchyard, when th' bell's towlin; an' there's some owd grey planks

lyin about among grayer stones that are worn wi' feet an' time; an'

shattered urns that han crumbled till their shape is lost. I' one o'

these cities o' polished marble we feel'n as if we're lookin round a

waxwork show, wheere ther nowt nobbut royal families in, an' thoose

o donned i' white. What a blessin it must be to be deead wi' o this

grandery about 'em! I'm no' quite sure that it's th' gradely thing

to be done, spendin th' lot o' brass ut these moniments must cost,

just for th' pleasure o' thinkin "Jake Peabody's owd whiteweshed

chimdy-pot is nowheere at side o' mine." Flowers are th' fittest

companions for thoose we liken ut we con keep no longer; an' moore

likely than stones to be brushed wi' an angel's wing.

Sunday dragged heavily o'er. It wur too dusty to goo out mich, an'

too wet to keep wakken in a church, as thou knows how soon I goo

o'er if thou doesno' keep shakin me, or givin me pinches. So I spent th' afternoon chiefly i' hangin my legs off th' pier, an' lookin at

th' boat ut I thowt I should ha' to ride an' sleep in th' day after,

obbut it wurno' it. When that geet too dull I watched 'em unload

baggage at th' hotel, an' wur curious to see whoa it belonged to. I

seed one name ut's weel known i' Manchester. It wur "Furneaux

Cooke," th' actor. I think it wur checked on to Montreal. When I

could find nowt elze to get time on with I wrote to thee.

Monday mornin we'rn up as soon as th' sparrows, gettin ready for a

bit moore emigration. We'rn for off now to th' tether end o'th'

lake. What bustlin ther wur when th' owd rapid-shooter, "Corsican,"

drew up to th' pier, or, as some co'en it, th' wharf, an' th'

gangway wur flung out. We'd a sort o' companions I'd seen noane on

before, gradely red Indians; noane o' yo'r common black niggers. Fine lads they wur, too. I didno' like havin mich o' nowt to do wi'

'em, as I'd read about 'em whippin th' middle tuft of a chap's

toppin off afore he knew wheere to scrat when th' place itched. Their talk to one another sounded to me summat like French, tho' it

mit ha' bin Welsh for owt I knew. But they could spake English as

weel as I could; becose one on 'em axt me for a match as plainly as

if thou'd bin axin me for a shillin. He talked quite civil, too; an'

I could hardly think he're one o' thoose ut could creep at th' back

of a chap like a cat, an' tommiawk him in a snifter. But he hadno'

his war paint on; an' that happen made th' difference.

Ther one owd squaw among 'em wi' a face about th' size an' shape an'

colour o' that pon thou boils plums in at pursarvin time. Hoo're a

gradely owd blossom, an' spent th' mooest of her time wi' nussin a

"papoose," ut I dar'say hoo're th' gronmother to. An' Indian nussin

is different to any thou sees i' our fowt now-a-days. No wheelin 'em

about while they lookin through shop windows, an' run among folk's

legs, but havin 'em aulus with 'em, as if they didno' want to get

rid on 'em, or wanted 'em to take care o' theirsels.

Sailin on Lake Ontario wur just like bein on th' sae an' I sometimes

thowt I're gooin whoam to thee, ut made me feel melancholy. We'rn out

o' seet o' lond directly, but we kept puttin in at places, looadin

an' unlooadin, ut kept us fro' being deead alive. When we geet among

th' "Thousand Islands" things began to be a bit moore lively, for

they aulus a bit o' nice lond to look at. Beside, it wur like playin

at "hide an' seech," speckilatin which o'th' gaps th' boat would go

through. Then we'rn aulus shootin through bits o' rapids, till we

geet Lachine; then everybody wur towd to look out. Th' captain had

getten his spy-glass to his e'e, an' wur lookin o'er th' wayter for

summat.

"It'll be a job for us if th' owd Indian doesno' turn up," a chap

said to me, ut I'm sure wur fro' th' owd spot.

"What Indian?" I axt him.

"Indian John, the pilot," he said.

"Why, what is there to pilot for?"

"Th' Rapids. If he doesno' come an' steer us we're lost. Nowt could

save us. We shall be dashed on th rocks. He's noane i'th' seet yet."

Then someb'dy shouted out—

"Thoose ut care about their clooas strip."

Well, whether I're lost mysel or not I didno' want my clooas to be

spoilt; so I'd prepared for th' wo'st. I'd just getten my jacket

off, an' wur mutterin a word or two about thee, when ther a shout

set up. Ther a little boat i'th' seet; an' it wur comin to'ard us. Th' captain's face breetened up; an' ther a bit o' a stir gooin on. Th' owd Indian pilot wur rowin to our salvation. "Here th' owd lad

is," an' not a minit too soon. He's on board, an' up aloft i'th'

steerin box. Four strong chaps han howd o'th' wheel; an' th' owd

Indian's een are pointed at summat; an' when I looked i'th' same

direction I could see th' wayter boilin up like an egg pon when th'

egg's brokken. Everybody wur as quiet as if ther some leetenin flyin

about, an' they didno' know which it would strike. Then th' engine

stopped, ut made things moore fearful. What, are we goin to be boilt

i' that hole? Th' owd Indian's een are fixed theere yet, pointin

to'ard that boilin wayter like th' muzzles of a double-barrel gun. We're sinkin. Th' nose o'th' boat's gooin down, an' th' heel's gooin

up. "If ever yo' prayed i' yo'r lives pray now," someb'dy shouts. I

took his advice, an' said summat about thee. It's o'er wi' us. We're goin like leetenin,—cleean on a rock; an' th' next minit we shall

be—Nob'dy taks their wynt. Crash!—Nawe, we'n just missed it; an'

Sammy o' Moses's said—

"Ab, thou'll live to plague that best friend o' thine a bit longer. We'n shot th' Rapids."

Return thanks for th' safety o'—Thy lucky yorney. AB.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER X.

AN OLD BATTLEFIELD.

LET me give our

friend Ab a brief holiday,—lay him comfortably on the lounge in the

grand hall of the Ottawa Hotel, while he gets over the almost

tropical heat, and the effects of climbing over too many "stone

fences," when nothing but the stars ought to have been shining.

"I'm done up," says the philosopher of Walmsley Fowt, as he rakes a

debris of broken ice from among his hair gradely done up. "Sammy,

here, says it's stone fences ut han done it. But I know a good deeal

better;—it's th' weather. I'm sure I conno' stood it mich longer.

I'm gooin as fast now as a candle on a fender. If it keeps this road

another day there'll be nowt left on me but a parchment bag full o'

booans. Wheere's Sammy?"

"Getting ready for a drive over Mount Royal."

"What; that hill wi' o that brushwood on it?"

"That hill that appears to be covered with trees."

"An' how con yo' get up it? Yo' mit as weel talk about droivin o'er

Pots an' Pon's, i' Saddlewo'th."

"There is a road winds round to the top, about six miles in length. We can reach it that way."

"Well, goo an' wind round it; an' have yo'r yure brunt off yo'r

yeads; I'm for stoppin wheere I am. Is there any moore ice about? I

could do wi' tuppin my yead again a whul berg."

"Go into the barber's shop, and be shampooed. That will cool your

head."

"Ay, an' goo whoam wi' a toppin as clear as if a red Indian had bin

tamperin with it. Nawe, not me. I tried a dose o' that i' New York,

an' I thowt he wouldno' ha' left as mich yure on my yead as would

ha' done for tuftin a shuttle. Another skeawer like that, an' our

Sal wouldno' know me when I geet whoam. Nawe, I'll be as I am, an'

weather it out. Oh, for a Niagara, an' another owd Roslie!"

Taking up the pen at the point where our friend has laid it down, I

must take the reader along the St. Lawrence, and on to Montreal. Here two of our party left us to proceed by rail to New York, the

rest having resolved upon a few days' tour through lower Canada. We

had on setting out purposed "striking" Montreal for a couple of

days' stay; but finding there was a steamer going down to Quebec,

and ready to depart, we boarded her at once, and were immediately

under way. After sailing three hundred and fifty miles, and spending

two days and a night on board, we had now before us a night voyage

of an additional hundred and eighty miles. Rather taxing one's power

of endurance after nine days' ocean sailing, a night on the Hudson,

and a memorable journey on the Erie Railroad. But, with all its

perils and inconveniences, river travelling, both in America and

Canada, is by far the pleasantest and cheapest way of seeing the

country. We have neither the dust nor the draughts to give as a most

trying discomfort; and we can walk about at will, and refresh when

necessary.

The sun was preparing for its seeming rest as we steamed away from

the wharf at Montreal; and a sunset in these regions of water is

something to behold. It is far more imposing than when seen on land;

and the twilight appears to hold out longer. The changing colours of

the sky were remarkable in their transition from orange to amber;

and then to a bright light green that darkened into a sombre grey,

ushering in the night, and the stars. The lights from the fishing

boats, and the numerous lumber rafts that brightened up the shore

line, were pleasant company after other objects had disappeared; and

they caused us to linger on the deck till those of the passengers

who had not engaged "state rooms," were laid and posed in all kinds

of postures among the freight; reminding us of a similar experience

on our way from Albany to Rochester.

When we turned in upstairs we found we had the saloon to ourselves,

with the exception of a steward, and a couple of stewardesses; all

of whom I took to be quadroons. The latter were the most ladylike,

and pleasantly spoken, of any we had met; no matter what colour. Their appearance and demeanour struck our friend Ab; and quite

reconciled that worthy to their claim of brother and sisterhood with

the stuck-up whites. He would have a word of observation before we

retired to our berths.

"I consider, Sammy," I heard him saying to his other friend, "ut

these two women are quite as good as thoose we makken wives on

i' our country."

"An' why not?"

"Ay, that's what I'm gooin to say. I'm sure they'r a deeal better lookin than some I know; I meean i' sich like looks as belong to

their behaviour. What their Maker has gan 'em they conno' help. An'

how nicely spokken these are! I wonder how they'd goo on if their husbants went whoam about hauve past eleven at neet, wi' one cooat

lap torn off, an' his hat like an owd pair o' ballis."

"They'd happen no' talk so nicely then."

"Well, it's likely that would raspen up their tongues if owt would. I wonder sometimes, Sammy, if we dunno' do a bit wrong to our wives;

an' it's that ut causes th' bit o' roughness ut polishes our ears up

when we should be asleep. Thoose women happen never sitten ov a neet

grinnin at four or five cinders i'th' bars o'th' firegrate while

their husbants han bin singin i' some alehouse nook, an' shakin honds about every two minits, as if they hadno' seen one another for

years. I'm feart we'n a good deeal to onswer for, Sammy." These

remarks by our friend Ab sent us to bed thinking.

Although the state rooms on these river boats are exceedingly small,

the berths are ample and commodious; and the bedding, in this

instance, as well as in most others, could not be surpassed for

cleanness and comfort. I never rested better than I did on these

boats; not even at that time of life when we have no anxieties about

the morrow; and did not live in fear of what the next post might

bring.

It was calm and peaceful rest that brought a streak of sunshine

through the window ere it could possibly be past midnight. Another

wink or two, and there was a hurrying to and fro of noisy feet; the

engine was motionless; and then came a knock to our stateroom door.

"We want your tickets, gentlemen."

How is that, so early? Hallo! Why, we are moored along the wharf at

Quebec; and the famed "Heights of Abraham" are—no, not frowning

down upon us, for the sun is throwing too much light on the face of

that sky-kissing fortress to say otherwise than that it smiles. I

may have taken that impression from the circumstance that there are

to be great doings there in a few days; and that the old French city

is now putting on its holiday attire. How is it that there is such

bustle in the streets? Why are the military galloping about from

place to place? Why so many flags flying? And why such a buzz of

Canadian-French in our ears? Don't we know; and Englishmen too? Don't we know that on the 24th of May, 1819, Princess Victoria, now

queen, was born? We did not happen to remember it at the time. Are

we not aware that on the anniversary of that day the people

throughout the Dominion hold holiday? Certainly not. Astonishing! We Britishers, countrymen of our Sovereign, not only do not celebrate a

national event, but actually do not remember when that event takes

place; whilst here, an alien race, speaking a language that to us is

"downright Greek," make general holiday on the occasion of an

English monarch's birthday. Verily we "aire" a strange people! I did

not hear this said, but the words passed through my mind.

Having run the gauntlet of a crowd of clamouring porters that make

prey of disembarking passengers, and nearly devour them by their

importunities, we made straight for the St. Louis Hotel, where we

put ourselves up for the day. But no rest was there to be for the

soles of our feet. We had barely housed our baggage, and refreshed

our bodies, when we were climbing the Heights, and entering the

square of the Citadel. Over these all but impregnable defences we

were conducted by a private of the garrison, who very civilly and

instructively pointed out to us the principal objects, historical

and military, to be seen there. From the battery we had a bird's-eye

view of the opposite shore of the St. Lawrence, which is one of the

most picturesque and magnificent sights in the world. I speak

advisedly when I make this assertion, as the statement is backed up

by authority that it would be rash to challenge. For miles in front

of us, and on each hand, on the sloping bank of the river, rise

terrace above terrace of glittering white villas, sleeping among low

clumps of forest growth, like eggs dropped in nests of bright and

leafy green. Stretching our gaze on that peaceful and lovely

prospect, it was not difficult to forget that we were in the

vicinity of military turmoil, with my hand resting on a cannon's

mouth, and in view of the field where the bloodiest and most

decisive battle of the frontier wars was fought. There Wolfe and Montcalm staked empire on the fight, which the former won, but at

the price of his life.

Having feasted the eye, though not to satiety, on a scene that can

never be forgotten, we had a drive about the city. It could not be

with feelings otherwise than patriotic that we approached the

monument erected on the "Plains of Abraham," to the memory of

General Wolfe, and which marks the spot where the gallant soldier

fell. It is a plain unpretending column, on the base of which is

inscribed the following—

"HERE DIED WOLFE, VICTORIOUS, SEPTEMBER 13, 1759."

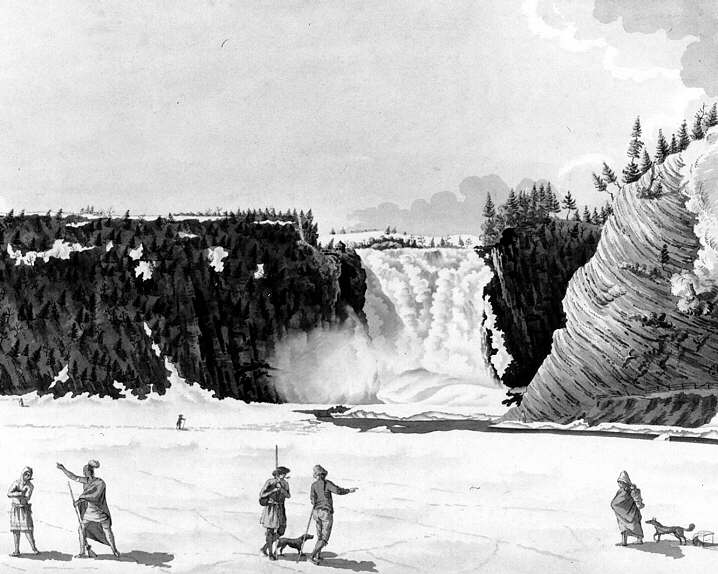

After dinner we drove to the "Falls of Montmorenci," about nine

miles from Quebec. This is one of the sights of a country that

appears to be richer in tumbling waters than America; for, after

sharing Niagara with the States, Canada has of its own the famous

cataract we were now visiting, as well as the "Falls of Lorette,"

which we intended seeing on the morrow; and the Falls and Rapids of

the "Chaudiere," on the Ottawa. On the road we saw that which we

might look for in vain in the eastern States of Yankeeland. We had

to pass through several small villages scattered here and there by

the wayside; the habitations of the dwellers therein, with fewer

exceptions than are worth naming, being picturesquely constructed,

and to appearances, very neatly kept. All of them had gardens either

at the front, or behind, with what struck me as being potato "patches" in the farther rear. In nearly all these, women with broad

backs, and faces that bespoke their Indian origin, were hard at

work; delving and hoeing, with strong limbed and strong minded

purpose. Only fancy a Yankee "gal" doing that! "Yaas, and one of

your tarnation Britishers," brother Jonathan might retort. Young and

old, it mattered not, their hands found work to do; and they were

doing it with a right good will. They just raised their heads as we

passed, their dark piercing eyes peering from beneath their hats or

sunshades, with mingled looks of curiosity and good humour. We

supposed their husbands, or brothers, or fathers, were employed on

the farms; and had left to these amazons the work of providing for

the necessities of the kitchen.

I am afraid the further we go away from the confines of savage life,

the less we become fitted for duties that are quite as essential to

domestic comfort, or a nation's well-being, as the strumming of a

piano; but are regarded as only suitable for a very low order of

beings to perform. I am not quite sure that we can all be ladies and

gentlemen in the way the terms are popularly understood, and the

world go jogging on, as if the fields would cultivate themselves,

and the harvests be gathered in by means of lessons in Greek, or

afternoons spent in games of lawn tennis. Somebody will have to

plough and harrow and cook and bake, irrespective of the size of

gloves they take, or whether their tailoring is supplied by Regent

Street or Shudehill. Otherwise to the "demnition bow-wows" we must

go; and before long.

We came upon the Falls of Montmorenci as we did upon those of

Niagara, without any very remote indication of their whereabouts. We

were inclined to ask our driver if he was not going wrong; or was

quite sure of the way. He at last pulled up at the door of an

hostelry situated in a picturesque glen, from which we could hear a

faint brawling sound wafted by the wind in musical cadences through

a fringe of forest. Our hostess pointed out the way we had to go;

and, after a few minutes' walk, we were at our destination.

|

|

|

The Montmorency Falls, Quebec.

Source: Wikipedia. |

There is more of the pretty than the stupendous in these falls—well,

we think so after Niagara; but when we consider that the water leaps

in an unbroken sheet into a depth of 250 feet, scattering clouds of

spray about till it is rendered dangerous to descend the wooden

stairway that leads to the bottom, it would be accounted a grand

sight if it was washing some ledge of rock in the old country. We

were told that, during one severe winter, this magnificent cascade

was fixed by the frost as if the whole sheet was of solid glass. Steps were cut in the frozen shell; and people ascended by them,

whilst the great body of the cataract tumbled and roared beneath. Our friend Ab considered that the whole continent was being washed

away; and that England would exist as an island long after the

Alleghanies had hidden their backs in the Atlantic ocean.

Our next day's excursion, as I have intimated, was to the Indian

village of Lorette. This, in one respect, was exceedingly

disappointing. I was in hopes of seeing redskins in their native

costume, and wigwams hung around with scalps. Instead of that we

found a village composed of as neatly built cottage dwellings as any

we had seen. The place and the inhabitants were quite of an English

type; and it was only by the depth of the eyes, and the prominence

of the cheek bones, that we could distinguish these children of the

prairie from the fairest of Europeans. Their house furnishings, as

we could see through open doors, were similar to those we meet with

in our Lancashire cottage homes. The housewives dressed after the

fashion of our own, and the male descendant of perhaps "Chingagook"

drove his cart and handled his spade like any other man. The

philosopher of Walmsley Fowt said he would not be surprised if he

heard the rattle of a loom, and saw the motion of the "twelve

apostles;" by which term he meant the bobbin wheel. We were not to

be scalped after all, nor compelled to take to each of ourselves a

squaw of royal blood. And when we came upon an hotel much after the

English fashion of such places, with a jolly Indian landlord, and a

jollier Indian landlady, we voted the whole thing a sell: we were

not in a savage land. And the farms, and the country round!—no:

civilisation has planted its foot in this at one time a wilderness,

and the varied types of the human race are becoming less distinct.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XI.

AN INDIAN VILLAGE.

MINE host of the

hotel where we had called at Lorette was just opening a box of

cigars, which was made up in a curious, and, I should say, primitive

fashion. The box was formed out of a reedy shell, that had

apparently enclosed a nut of some kind, and was petalled like a

tulip; but in several folds. This shell was packed with the

"weeds;" and on the outside the maker's name was branded in quite as

official a manner as if it had been issued from Cope's.

But the Lorette Falls! Well; they are a succession of

cascades, that leap, step by step, in clouds of spray, till, taking

a final bound, the roaring mass plunges beneath a cavernous cleft,

and is lost to immediate view.

These falls have more of the awful in their character than

even those of Niagara; and the faint reproduction of them in my

memory will at any time make me shudder. I had forgotten to

say that, though the day was hot, we frequently met with drifts of

snow several feet in thickness. In fact, it was only just a

week since the good people of Quebec had enjoyed their last

sleighing. We saw more than one of these machines, the slides

of which were not yet rusted.

Leaving Lorette, the objects of curious squaws and screaming

"papooses," we returned to Quebec, intending to take the night boat

to Montreal. We were within a near shave of being detained

another night in the city of Jacques Cartier; but our horse, like

most others of its species, knew his way home; and the road was more

kindly to his feet than it was on our journey out. The result

of this superior animal instinct was, that we were put down on the

quay so near to the time of starting that I found my washing there,

waiting to be taken on board.

Going up this river was somewhat like the coming down, with

this difference, the little daylight spared to us we had where in

our voyage down we passed in darkness and in sleep. It gave us

an opportunity of seeing how vast is this lumbering region; and how

different from our own must be the habits of people who almost live

on naked rafts, and are constantly encountering the perils of the

numerous rapids. We arrived at our destination about half-past

six of a glorious morning; and, not before we were in want of it, we

were doing "ample justice," as the penny-a-liners say, to the "good

things" that, in the shape of breakfast, were set before us.

There is nothing beats a morning appetite. Heap it well up,

and you require no additional fuel till the evening brings

dinner-time.

So comfortably were we quartered at the Ottawa Hotel that our

friend Ab declared his disposition to be blanked if he stirred from

there to see anything till he had rested himself, and fetched up

considerably his arrears in feeding. He would be double

blanked if we were not the uneasiest lot that he had ever the

misfortune to go out with.

"Yo'r wurr," he said, "than owd Donty Etches when he went a-fishin

i'th' Cryme. Him an' young Donty had sit watchin for a bite

above four hours, without as mich as havin a nibble. Th' owd

un couldno' sit long i' one place, but kept tryin about, an'

grumblin savagely. But th' yung un kept sittin theere, as

still as if he'd been i'th' stocks, watchin his flatter (float), an'

chewin baitin dough, fort' keep th' hunger worm fro' botherin him.

At last his patience broke down; no' becose he'd catcht nowt, but

becose his fayther was so unsatisfied, an' kept breakin out wi' his

fits o' grumblin. Turnin to th' owd chap, he said,—'Dam thee,

dad, thou'rt never yezzy.' Yo chaps are th' same. Yo

never putten yor heels down i' one place, but yo wanton to be turnin

yo'r toes to'ard another. As for Sammy theere, carryin' th'

weight he does,—I'm surprised he doesno break down. I'm

terribly bent now."

Montreal, like Quebec, was preparing itself for the 24th; but

after a different fashion. Here the Queen's birthday fétes

were at one time held, and the Catholic procession festival of "St.

Jean de Baptiste," which even outstripped the review in the

splendour of its "get up." But now the Mount Royal was not to

echo the boom of artillery; nor were the streets to be bedizened

with pious pageantry. The whole paraphernalia, if the word is

appropriate, was to be transferred to Quebec. We cared not for

sights such as human vanity, or caprice, or ambition, had created.

These could be seen at home. We were there to see what Nature

had done in her mighty works, and commune in a humble spirit with

what we beheld. But Montreal was preparing to go out of town,

and the announcements of "cheap trips" and "special trains" covered

the walls. This old French city is much like Toronto; and

beyond Mount Royal and the waterworks the sights are little varied.

There is a splendid Roman Catholic Cathedral there; so are there at

many places in Europe, but that need not be particularised. We

spent the day in lounging about, refreshing our energies for the

coming morrow, when we were to proceed to the capital of the

Dominion, Ottawa; another run by rail and water of one hundred and

sixty miles.

The morning following we had to "hurry up;" the train to

Lachine being tabled to start early. We were obliged to go

this distance by rail on account of the impossibility of going up

the rapids by boat. There had been rain somewhere—heavy

rain—perhaps many hundreds of miles away; and the Ottawa, which

joins the St. Lawrence at Lachine, was much swollen. We could

see the difference in the colour of the two rivers. Arrived at

Lachine, we took the boat; and notwithstanding the weather being

inclined to be wet, the voyage between the woody and fair banks of

the chief of lumbering rivers was a most delightful and interesting

one. On arriving at St. Ann's a cottage was pointed out to me,

but which I failed to distinguish from the rest, in which Tom Moore

wrote his celebrated "Canadian Boat Song." The genial Irish

poet could not, however, have been very well acquainted with river

navigation, as is evident by the song. But as we approached

the rapids I could not help humming to myself—

|

Faintly as tolls the evening chime,

Our voices keep tune, and our oars keep time,

Soon as the woods on shore look dim,

We'll sing at St. Ann's our parting hymn.

Row,

brothers, row; the stream runs fast;

The rapids

are near, and the daylight's past.

Why should we yet our sails unfurl?

There is not a breath the blue wave to curl;

But when the wind blows off the shore,

Oh, sweetly we'll rest our weary oar.

Blow,

breezes, blow, &c.

Utaway's (Ottawa) tide, this trembling moon,

Shall see us float over thy surges soon.

Saint of this green isle, hear our prayer;

Grant us cool heavens, and fav'ring air.

Blow,

breezes, blow, &c. |

Whatever may be its poetic or lyric standard, the above song

does not indicate that Tom Moore was very proficient in his

knowledge of river navigation. If the "rapids were near, and

the daylight past," it is not likely that Canadian boatmen would

wait on the river till the "woods on shore looked dim" before

landing. I feel persuaded they would have moored their boat

before the daylight had passed, if they did not wish to be engulfed

in the fearful rush of water which is immediately opposite St.

Ann's.

The scenery on the banks of the Ottawa may not be as romantic

as that of the Hudson; but it is quite as pleasing, or, we thought,

must be, when the weather was propitious, and the river had not

encroached too far on the farming lands, and the trees were not up

to the waist in newly-formed lakes. After leaving the lock at

St. Ann's, it became quite evident to us that the channel of the

stream had been very much extended in width. Farmers do not

usually build outhouses, or "heneries" in the midst of large pools

and the fowls would very soon be tired of trying to "peck" up a

living among branches of larch. But the king of the roost was

quite as jubilant on his foliage-hidden perch as he would have been

on the more familiar dunghill. Possibly he knew that his exile

was only temporary.

It was interesting, and sometimes alarming, to see the

varieties of debris that floated past us; sometimes in the

form of lumber, as if a yard had been swept out; and in successive

instances something suggestive of raids upon household

effects;—tubs, boxes, and turned materials, that led us to fear we

might see a cradle, if not a baby, dancing among the eddies.

One of the strangest sights that could greet an untravelled

eye is a lumber raft, such as may be seen on rivers like the Ottawa.

They are like floating villages. You may see women at their

tubs washing; others cooking; and lines of drying clothes that are

flapping in the breeze would almost suggest that the raft was being

driven by them. One of these so amused our friend Ab that he

waxed quite enthusiastic on the subject of the life it was possible

to lead on board such novel craft. He expanded their

usefulness immensely.

"I consider," he said, "that livin in a palace wouldno' be

hauve as grand as livin on one o' thoose; no bad smells comin fro'

neglected sinks; no beggars; no poor relations comin a-ownin yo'; no

box organs; no gooin round wi' th' hat for chapels i' debt; no rent

chaps; no gooin to th' owd Bell; no drunken folk knockin yo' up, an'

wantin to know what day o'th' month it'll be at twelve o'clock; no

looms, no bobbinwheels; no dogs smellin at yo'r stockins w' their

teeth; no cats takkin lessons i' music when they should ha' bin

mousin; nob'dy wantin to know if it would mak no difference paying

for th' stuff afore it wur sent; no fife an' drum bands; no bazaars;

no drunken pick-nickers yelin past yo'r dur; no elections, nor

collections; no gooin wi' th' wife to a shop, an' stondin at th'

window till hoo comes out; no feelloss-o'-speeds; no gooin into th'

church last, so ut they con be better seen, when they'n had a pound

or two spent on their yead; no wantin to read a chapter for yo', as

if yo' couldno' read it yo'rsel. It would be like a week o'

Sundays, sailing down a hundert an' odd miles, aulus livin in a

fresh place, an' havin no lodgins to pay, seein fresh neighbours and

fresh faces, an' no bother o'er gettin fresh tickets, an' no fear o'

gettin into th' wrong train, or bein left at a station if yo' happen

to get out for summat."

We arrived at Ottawa, the capital of the Dominion, before the

night fell, and found the streets of this new city exceedingly muddy

in consequence of the rain, and the ankle-depth of dust. We in

England know nothing of muddy streets, as much as we grumble about

them in newspapers. We had not many yards to go to the Porter

House Hotel; but we were obliged to take a street car, although we

had only our hand baggage with us. It is not to be wondered at

that the roads are bad, the city has grown so rapidly since the seat

of government was removed to there. We found things very much

similar to what we find them in second-rate cities in the States,

and which must be highly prejudicial to the eyes of foreigners;

especially Englishmen. We had to pay very dearly for our

whistles. I could live hotel life in that old worn-out country

called England for two-thirds the cost of similar living in the New

World. Everything, to use a homely phrase, is "brass savvort."

We hired a carriage the following day, which cost us three dollars,

or twelve and sixpence of our money, for a sort of sauntering drive

of two hours, during which we did not cover more than twice as many

miles. But it was Sunday; and possibly the price might have

been "put on" in consideration of its being the Sabbath.

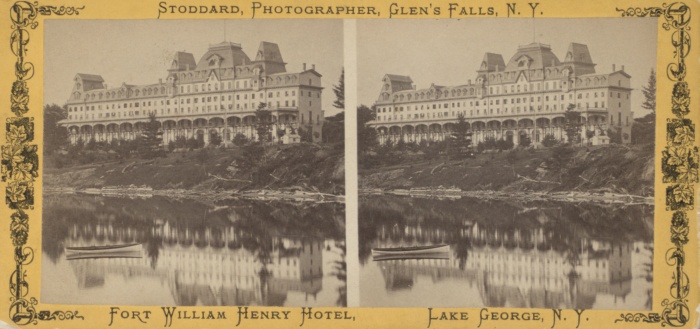

The wonders of Ottawa are its Falls and its lumber yards.

The latter extend for miles; and the piles of sawn timber that meet

the eye everywhere suggest the thought, that a number of new cities

have to be built and furnished and otherwise completed at the rate

of one per day. The saw-mills are on a par with the lumber yards;

and are all driven by water power. We were informed that the

whole of the material we could see, and as much as could be sawn up

to September, was already bespoke.

The Falls of the Chaudiére, which area good second to

Niagara, only of quite a different character, are spanned by a

suspension bridge, which is the principal connection between Upper

and Lower Canada. From this bridge we had a splendid view of

the cataract; which, though not so majestic as Niagara, is equally

awe inspiring. Like Lorette, it is more a succession of rapids

than a clear-falling cascade; and the terrible jumps and furious

rushing of angry water make you feel that, secure as is the footing

on which you stand, the flood in its wrath may yet reach higher with

its mighty arms, and drag you into its fearful depths to be seen no

more. Some passengers over the bridge had a horrible sight

presented to them only a few days before we were there. A man

in a boat was seen struggling in the upper rapids; and it was a

struggle, as, no doubt, he felt, for life. Once get among

those huge "lumps" of tossing water, and you may lay down your oars,

and resign yourself to the care and keeping of the Almighty; for

probably your end is near. The stricken crowd saw the speck of

a boat and the arms flung wildly about as if in supplication for aid

that it was impossible to give; and there was a few moments—only a

very few—of suspense, as one by one, each larger than its

predecessor, of those whirling and lashing fiends grip and toss the

frail craft and its doomed occupant on their rapid and plunging

course. Not a breath is drawn; but eyes are strained, and

un-uttered prayers go forth that—he has shot the Falls, and—Great

God!—there are a few splinters of wood whirling about below; a

something is being ground in a mill of water for just while one

could think, and all is over. He is sucked into the vortex and

seen no more.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XII.

AB'S SIXTH LETTER TO HIS WIFE.―LOST AND LEFT.

Parker House Hotel, Boston, Mass., May 28th.

MY

GUIDIN ANGEL,—I've

never bin i' greater need i' my life o' havin thee wi' me than I

have bin this last three or four days. When a mon trusts to

hissel he's very little to trust to. That I've fund out above

once. A wife's guidance is th' next dur to everythin to him;

an' saves him mony a time fro' gooin blunderin about like a wall-eed

dog; an' gettin into scrapes ut are no credit to his bringin up.

I hardly know how to begin o' tellin thee what I've gone through

sin' I wrote to thee last time—how to soften things down ut I know

are sure to goo hard again me, an' mak thee think I'm noane fit to

be trusted above th' length of a bull-rope fro' our rain-tub.

Happen it'll be th' best to let out gradely; an' leeave thee to

deeal wi' me as thou thinks fit when I get within raich o' thy

nails.

For a start, I've bin lost! lost, as I may say, i' my own

house; for it wur i'th' hotel I're stoppin at; an' that I consider's

my whoam as long as I'm theere. It coome about this road.

While we'rn stoppin at th' Ottawa Hotel, i' Montreal, an'

it's very nee as big as some factories, whenever we went to bed

we'rn wun up by what they co'en th' "elevator." I'th' owd

conntry they'd co it a "hoist." After bein londed at our level

I could find my road to our sleepin shop when I'd bin shown it a

time or two tho' ther mony a twinin an' turnin, an' durs an' corners

ut looked like ours, but wurno'. One afternoon I wanted summat

out o' my bag,—I may as weel tell thee what,—it wur thy likeness, ut

I made a practice o' lookin at as oft as I thowt nob'dy wur watchin

th' effect it had on me. This time I thowt I'd go by th'

stairs, as I'd botheret th' young chap ut looked after th' elevator

so oft that, whenever I happened to go past th' cage dur, he oppent

it an' bounced into th' cage, as if he expected me to follow.

I'd bauk him for once; so upstairs I went,—two storeys—an' began a-ramblin

about. Wur ever anybody sent o' sich a gawmless arrand?

I'd forgotten th' number o' our dur; an' tho' it wur on th' key I

never once thowt at lookin at it. Eh, lorgus a-me, Sal; what a

trapes I had fro' lobby to lobby as wide as our lone; an' o'er

carpets ut are padded under, till it's like walkin o'er so mony

fither-beds. "Tummas" seechin "Nip" wur a foo of a job to what

I had i' hond. It wur as bad as tryin to slip thee at a wakes

time. I kept moanderin about fro' dur to dur, peepin through

keyholes for t' see if ther owt I could tell th' chamber by; an'

sometimes tryin if my key would fit. It wur no use; so after

huntin about twenty minits, without ever gettin on th' scent, I gan

it up, an' would go down th' stairs again.

Ay, would go down stairs; but I mun find 'em th' fust.

I co'ed mysel to ha' planted a lond-mark or two, so ut when I had to

retrace I could do so without blunderin. But I couldno' tell

these lond-marks again, so wur as fast as ever. I're gettin

into new roads, an' new places. As for meetin anybody for t'

sper 'em, I mit as weel ha' bin i' some wilderness between Dan and

Beersheba, if t' knows wheere that is. I're as cleean lost as

thou wur once when thou're seechin th' "Sorrow's Arms,"

* i' Manchester. I'th' depth o' my solitude

I sit mysel down on a step for t' rest a bit, an' consider what I

should do i'th' case of a fire breakin out. A thowt struck me,

an' it coome buzzin into my yead like a hummabee—I'd go to th'

elevator, an' start fro' theere. But I couldno' find th'

elevator. I mit as weel look for th' stairs as that; so I gan

things up. At last I yerd what I took to be th' craikin of a

boot sole, an' I hearkened till I dar' say my ears grew an inch

longer. Crusoe never looked at a speck upo' th' sae wi'

greater lippenment than I hearkened for that sound ut kept comin

narr. "Ship-a-hoy!" I're saved, I calkilated; when a

summat broke on my seet i' th' shape of a young woman wi' a cleeanin

rag in her hont. I felt then as if I'd a had her if thou'd bin

out o'th' road.

"Con yo' tell me wheere I con find th'—th'—a—hoist?" I said

to her. I couldno' think o'th' word "elevator" then.

Hoo grinned at th' fust, as if hoo thowt I're havin her on th'

stick a bit; but at last hoo said—

"I guess I'm a Yank, an' don't know French."

"That thing ut they wind up by," I said; an' I began a-playin

wi' a five cent piece ut I'd poo'd out o' my pocket.

Hoo hung her yead down a bit; then looked round, an' wiped

her lips wi' her appron. Then hoo cocked up her jib, as if hoo

expected me takkin out five cents wo'th of a—of a—smack.

"It's noane o' that I want," I said; but at th' same time

feelin desperately tempted—as thou'll believe; "it's that;"

an' I began actin as if I're pooin at a rope, and windin up.

"Elevator? around the corner there;" an' hoo pointed about a

dozen roads in a jiffy; then off hoo skipped, but—not without th'

five cent piece.

I fund th' elevator "around the corner there," an' had

another fair start. I're o reet now, I thowt; so set out on my

wandering again. I did what I considered my share o' turnins,

on' coome to a corner ut wur rayther darkish, wheere I co'ed mysel

sure o' findin our dur. Strange th' dur wur part oppen, an'

then a key i'th' hole. Sammy o' Moses's hadno' come in, I're

sure, unless he'd made his way theere while I're blunderin about th'

hotel on my vowage o' discovery. I pushed th' dur oppen, an'

marched in; but wur turned on wi' a chap ut stood at th' lookin-glass.

"If you think you've as much right to this room as I have,

come in," th' mon said rather sharply, as I thowt.

"Wheay, it's my shop," I said but believe me, Sal, I'd my

deauts about it at th' time.

"I guess it aint," th' mon said; an' I didno' like his looks

a bit. "Hav'nt got so much baggage that I can spare any; so

yer needn't prowl around here; for by Jimminy you won't git it."

I're never takken for a thief afore; an' if it had no' bin ut

I could see things about that I hadno' seen afore, ut made me think

I're i'th' wrong shop; I'd ha' had howd of a hontful o' pants in a

hauve a minit. As it wur I slunk out as if I'd stown summat,

an' went in for a bit moore explorin.

When I geet back to my startin point, I fund then two

women,—I reckon they'rn ladies, gettin out o'th' cage o'th'

elevator. Then I seed Sammy o' Moses's at th' back on em; but

he never offered to get out.

"What art' dooin theere, Ab?" he said; as if he're gloppent

at seein me.

"I've bin about three quarters of an hour tryin t' find our

snoozin shop," I towd him.

"Ay, thou mit try a week, an' no' find it upo' this floor,"

Sammy said. "Thou'rt a storey too low. Get in here, an'

I'll put thee to reets. Thou'rt no' fit to be trusted by

thysel."

I geet into th' cage without twice tellin, as thou may be

sure; an' I're some fain at seein a sign o' deliverance. It

never coome into my yead ut I could get on th' wrong storey. I

reckon thou'll think it's just like me.

"It's lucky I lit on thee," Sammy said, when we'd londed upo'

th' reet floor. "I're gooin on th' spec o' findin thee i'th'

chamber, dooin a snooze, becose they towd me thou'd takken th' key

about an hour sin."

"Well, I're never i' such a funk i' my life," I said.

"I've walked mony a mile as sure as a yard. I're very nee

makkin a mistake once ut mit ha' ended i' blood."

"How did that happen?"

"I geet into th' wrong hoose, an' wur very nee turnin a mon

out."

"That is if he'd ha' letten thee, I reckon."

"Well, if his pants had bin strong enough to ha' held his

weight he'd had to ha' gone."

"It's a wonder he didno' shoot thee as it wur."

"I didno' think o' that. By goss, Sammy, he mit oather

ha' killed or winged me."

Sarah, I believe ut if I hadno' somb'dy to look after me, an'

keep me straight, thou'd never see me no moore. I should

oather be kilt, or drownt, or lost. As it wur, Sammy put me to

reets without makkin a wrong turn, an' I'd th' happiness o' lookin

at thy portergraft once again. What a blessin! This

happened after th' pilgrimage to Ottawa an' Quebec. But it wur

nowt to what happened a day or two after that. We'rn booath on

us i'th' mess this time; but thou conno' say 'at we'rn oather on

us i'th' faut, if thou thinks so. We went through a cooarse o'

roastin, an' clemmin, an' dryin up, an' powlerin about, ut wur even

wurr than what we'rn dosed with on th' road fro' Albany to th' Falls

o' Niagara.

We'd left Montreal for t' "rail " it, as they sayn, to Boston

intendin to break our journey at Lowell an' see th' factories theere.

Five "pieces" of our baggage we'd checked on to th' fur end; an'

took a bag apiece, wi' just a change o' skin coverin, for t' carry

with us. These we had i'th' car we travelled in. We'd

calkilated o' havin a grand out, th' mornin wur so fine; an' th' day

bein very young it wurno' so wot as it turned out to be later on.

Th' train crept slowly o'er th' wooden bridge ut crosses a narrow

part o'th' St. Lawrence—nobbut about a sprint race length short o'

two miles; an' then we spun an' jowted through a country ut wur made

for a railroad, becose there'd be no cuttin to be done; wi' thickly

wooded slopes o' booath sides, ut made it look a bit like England.

Wheere it wurno' like th' owd country wur when wer'n crossin narrow

points o' Lake Champlain; an' by rivers sich as we'n noane awhoam.

Th' beginnin o' our misery wur when gooin through a valley ut wur

filled wi' flowerin willows. If th' windows wur shut we'rn

roasted, becose we'rn gettin into a warmer country; an' if we had 'em

oppen we mit as weel ha' bin ridin through a scutch-hole in a cotton

factory. This willow blossom flew about like a shower o'

riddled snow; an' covered us o'er till we hardly knew one another.

But we should stop at St. Albans, an' ha' twenty minits allowed for

packin our insides, ut wur gettin wofully slamp; an' a brushin an' a

weshin would mak us feel like new uns.

Well, we did stop at St. Albans, an' twenty minutes, too; but

we'd better never ha' stopt at o, for as we'd left Canady, an'

getten int' Ameriky, we had to have our baggage examined, what

little bit we had. Then we had to get fresh tickets; an' by th' time

we'd done that we had to run for t' get into th' train. Ther noather

bitin, nor suppin, nor weshin, nor brushin to be done. We had to be

fain we hadno' bin left on th' "dippo," as, they co'en th' stations

i' Yankeeland. What sort o' language passed between Sammy an' me

would ha' getten us into a hobble if anybody else had yerd it. If th' owd brass bird, ut wur peearcht up at th' end o'th' car, wi' its

wings spread out, could ha' had just a minit's life put into it, it

would ha' pecked our een out. It wur one blaze o' temper after that,

becose we'd nowt to cool it with nobbut about two hauve noggins o'

iced wayter, ut wur sarved out like doses o' brimstone an' traycle

i'th' warkhouse. Didno' we carry on? Thou'd ha' thowt so if thou'd

yerd us. But th' wo'st had to come yet. When we'd bin peppered wi'

dust an' willow blossom for above ten hours, wi' insides as empty as

a red herrin on a gridiron, we poo'd up at a place co'ed Manchester.

It wur like havin a swig i' champagne pop to us yerrin that name.

"Come on, Ab," Sammy said; "there's a sign o' summat now." An' we

scrawled out o' our seeats, as wambly as two roosters ut han fowten

till they con hardly stond, an' crept to th' dur. We could see a bar

window oppen, ut had biskets, an' other things i' glass cases.

"Is there time to have a drink here?" Sammy said to th' conductor.

"Plenty of time."

We didno' stop for t' yer owt any moore, but dropt on th' flags,

like two dried mops ut hadno' had th' sond wesht eaut, an' wriggled

oursels to th' bar window. A sleepy sort of a young woman, ut

couldno' find th' corkscrew when hoo wanted it, an' ut favvort hoo'd

rayther no sarve us than do it, kept us longin till we'rn ready t'

drop. Then when hoo did teem summat out, an' we thowt our troubles

wur comin to an end, ther new uns startin. Before we could get howd

o' our glasses an' have a swig th' train wur off, wi' unchecked

baggage at anybody's mercy. If our faces had bin portergraft, then

they'd ha' made a fine picture o' disappointment, gloppentness,

bewilderment, vexation, revenge, seediness, an' hauve fried

beefsteaks. There's a mixture for thee. Then, when we could unglue

our tongues, we let out—reet fro' th' shooter—till th' bar window wur

banged down, an' th' shutters put up, for fear o' summat takkin

fire. When we'd blown th' steeam off, we went to th' talegraft box,

wheere ther a young woman, rather wakkener-lookin than that at th'

bar, axt us what we wanted.

"Talegraft to th' station agent at Nashua (th' next dippo), for t'

tak two bags out o'th' second car, an' send 'em by th' next train

back." That wur our order.

Hoo did so an' when we'd waited for t' yer back, th' station agent

"wired" ut he hadno' time to look for 'em. Then we wired in wi' our

tongues, till th' telegraft box wur filled wi' reech.

Then we telegraft to Boston for t' keep th' bags theere, if they

could find 'em, an' put 'em to our checked baggage, as it would be

too late for t' send 'em back. What made things wurr, thou sees,

ther no' train fro' Manchester that neet; an' we'rn londed theere, dusty

an' raw, wi' nowt for t' change on, up to th' ankles i' blazin wot

sond, an' wi' tempers three times as wot. We towd that young woman

ut if our baggage wur lost we should send for t' British Lion an'

he'd chew up that owd ragged-winged sparrow-hawk o' theirs afore it

could croak. That feart her so ut hoo wouldno' be paid for th' last

o'th' telegrafts. I darsay hoo'd never yerd two Englishmen give a

war-whoop before.

Fort' make th' best o' things we went an' tried to cool oursels by

th' side o'th' River Merrimac, ut turns about four factories theere. An' we geet a bit soothed wi' watchin th' factory wenches loce,—not

as they dun i' England, wi' shawls o' their arms, an' cloggin it

whoam four abreast. Waggonettes wur waitin for 'em, thoose ut lived

at a distance; an' what surprised us when they drove past, wur to

see 'em dressed up as if for a pic-nic, an' yer 'em jabberin French.

What happened after I'll tell thee sometime else. I ha' no time now, becose th' chamber wench 'll be comin a-makkin th' bed directly, an'

I've nowt on nobbut my stockins an' shirt; an' bein roasted even i'

that state. So good day, owd crayther—an' believe I'm still.

Thy whoam-sick rambler,

AB.

* The old "Sawyer's Arms," now the Wellington Hotel, Nicholas Croft,

was at one time a favourite calling place for handloom weavers. Its

name got corrupted into "Sorrow's Arms;" and I never in those days

heard it called by any other.—B.B.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XIII.

AB'S SEVENTH LETTER TO HIS WIFE.—

YANKEE LADS AND LASSES.

Continental Hotel, Philadelphia, Penn., June 3.

OWD

POW-STAR—I'm

i'th' Quaker city; but how I've getter here would bother me to tell.

I've plashed through some wayter, an' dashed o'er some lond since th'

last letter I wrote to thee. At one time I thowt that if ever I're

shifted out Y Boston I should ha' to be carried in a seek; an' then

there'd be nowt nobbut booans, an' thoose part brunt, as if they'rn

bein made int' charcoal. It's noane so cool here when one gets into

th' sun; an' there's no keepin out on't, unless we're inside

somewheere.

I' my last letter I towd thee about bein left at Manchester, i' New

Hampshire; an' what a fix we'rn in, wi' shirts glued to our skins,

an' our faces like beef steaks Bonded o'er i'stead o' bein sauted.

How we'd nowt to change on, nobbut fresh cooats o' dust; an' th'

yeat wur 127 degrees i'th' sun. After we'd welly set fire to th'

station—dippo, I mean; by th' way we carried on o'er losin our

baggage, we Grappled into th' city; an' looked out for a place

wheere they'd tak us in, an' put us under th' pump. Th' fust place

we "struck" wur Manchester Hotel; an' we Battled on trying theere.

I never seed a londlort look so puzzled as ours did when we stood

afore him, as if waitin for our lowance after gettin coals in, an'

sweepin a factory out. He seemed to be sayin to hissel,—"What,

travellers, fro' England, an' no baggage with 'em! They must be a

queer lot. However, if they payn their bill before they toucher a

bite, or han a swig, it's nowt to me." This we did; an' we'rn looked

on as gentlemen, but of a strange breed, when we'd stumped down our

green rags. After suckin a "schooner" o' lager, like suckin a egg, I

went out for t' see wheere I could find a barber's shop; for my chin

felt like a burr, or an urchant's back. I fund one close by, an' in

I went.

"How mich dun yo' charge for shavin?" I axt.

"Ten cents," I're towd.

"Ten cents! Wheay, I could ha' my yead shaved i' England for that,"

I said, quite gloppent at th' price.

"I guess yew kin here," th' barber said.

"How mich would yo' charge for th' loan of a razzor?" I axt, thinkin

I'd get it at hauve price.

"Ten cents."

"Let's be havin howd o' one. I'll show yo' how its Britishers con

scrape a chin."

He did so; but he turned white when he'd done it, an' seen my wild

looks. I dar'say he thowt I're gooin t' do summat elze than shave.

But I rubbed some sooap o'er my chewin power, an' my nose flap; an'

i' just one minit by a cuckoo clock I' cleared my lond o' every bit

o' stubble there wur. I'd dun that while he're gettin howd of

another chap's nose.

"I've five friends at th' Manchester Hotel, an' they wanten shavin,"

I said. "I con just net a hauve a dollar while yo'r dooin ten cents

wo'th." But he'd th' dur baricaded up afore I could make a move.

I set up a crack o' laafin; an' he did th' same, for he could see

I're nobbut havin him on th' stick. Then he gan me five cents back;

an' offered to shave my friends at th' same price; but I towd him

they'rn i' England; an' it would be rayther too far for 'em to come

o' purpose o' bein shaved. He stared to some pattern when I towd him

a mon i'th' owd country could have shave, an' yer o th' news o'th'

day, an' be towd as mony lies as would fill a Yankee newspaper, for

a penny, or two cents. If it wurno' for fear o' clemmin other

barbers to death, I'd stop in Ameriky, an' run a shavin shop. I

thowt I'd do a bit of a stroke for owd Jack Bull.

When neet set in, an' we could get a window oppen to sit at, we

began to feel a bit cooler. Th' temper worked off a bit; an' as we

knew ther nowt getten by frettin, we agreed not for t' care a cent

for our baggage chus whoo'ad getten it. We'd tak things as they

coome; but still it wur "tarnationly" provokin. I dunno' think it

lost us a minit's sleep, we'rn so tired; an' when mornin coome we'rn

up, an' had our collars turned inside out afore ther mony Yankees

stirrin. It wur a grand mornin afore th' owd sun had blown his fire

up gradely; so we sauntered out, an' looked about us, an' counted th'

number o' druggists' shops there wur, an' agreed among us at ther

summat beside physic swallowed inside 'em.

If we'd seen Manchester under different circumstances than havin

lost our baggage, as we thowt, I believe we should ha' liked it.

Like what con be seen i' every Yankee city that we went to, there's

reaum for folk to tak their wynt, an' that's moore than con be said

about towns i'th' owd country. Just fancy, owd craythcr, there bein

a park i'th' middle o' Manchester, England. Fancy childer lookin

healthy, an' cleean, an' weel donned. Fancy it lookin like a haliday

o th' week round, yet everybody workin,—no singin beggars i'th'

streets; no auvish lads stondin at corners; nob'dy followin thee,

an' wantin just a pint; no signs o' clemmin, nor that sort o'

idleness ut conno' be helped! "Ah, but," thou may say, " th'

country's young yet; wait till someb'dy wants to ha' moore power

than another; gets into th' President's cheear, and says nob'dy

shall shift him. Let him parcel th' lond out to a lot o' folk like

him, ut wanten power too. Let these gether round 'em a two-thri

thousants o' fool ut'll shout, an' feight, an' give up their liberty

for a bit o' glitter. Let 'em swap "Yankee Doodle " for "God save

the King;" an' thoose parks i'th' middle o' their cities 'll goo out

o'th' seet. Someb'dy's rent audit mun be made bigger; never mind

noather health, nor comfort; build back-to-back houses; let th'

streets be swarmin wi' ragged an' dirty childer; pauperise one hauve

o' folk, an' let th' tother hauve live o' one another, an' then,

like us, th' Yankees 'll ha' summat to swagger about. No country's

gradely civilised till every town's made into a human middin.

If we'd had it as wot i' Manchester, England, as it wur i'

Manchester, New Hampshire, nob'dy could ha' lived. They'd ha' bin

sweltered to deeath, becose they couldno' ha' fund room for t' get

up a bit of a cool breeze. Here, wi' th' sun reet o'er our yeads,

an' sendin down a yeat like comin out o' our oon ov a bakin-day,

when thou looks how th' mouffins are risin, there's a bit o'

comfort, becose we are no' choked wi' soot, an' Huss, an' reech, an'

bad smells, an' a general thickness o' air ut owt to be thin. For o

ut I had turned my collar, an' had a shirt on ut wouldno' pass

muster even i'th' owd country, I felt quite leet. That bit o'th'

park wheere th' war moniment stonds wur like rowlin i' new cut hay

to me. There's summat good, I feel sure, i' trees; an' wheeze

they're deein out, as they are i' England, th' country winno' long

be fit to live in.

After leeavin Manchester we geet to Lowell about th' middle o'th'

afternoon, an' fund th' place very mich like other cities—white

houses, sond, and trees. We'd a droive i'th' country, as us'al, for

goo wheere we choose, Sammy o' Moses's would be at th' back of a

tit's tail wi' three sticks howdin a cover up at his elbow. This

time Sammy drove Kissel. We'd th' cheek for t' goo an' ax a •chap

for t' lend us a Koss an' buggy, as if he'd known us

fro' bein childer; but as soon as he yerd us talk, an' knew we'rn

Englishmen, he'd ha' trusted us wi' owt -an' when an owd Irishman ut

hostled for him towd him wer'n Lanky, I believe he'd ha' -an us his

clooas an' never felt if they owt in his pockets. I shawm sometimes

when I think how forrin folk are o'erseen in us.

An' now for Lowell factory wenches, ut we'n yerd so mich about. We'd

gone theere o' purpose o' seein 'em. I know what thou'll think when

thou reads that. An' thou'll say to thysel'—"Dear-a-me! travelled I

know not how moray thousant mile, an' their yorneyishness no' rubbed

out on 'em yet!" But we planked oursels under a tree—we couldno' ha'

done that i' Owdham—an' waited till th' factories loced. In a while

a procession began a-windin down th' street. We took it to be some

ladies' skoo wi' their sweethearts followin 'em for t' know wheeze

they must meet 'em at neet. On they coome; some on 'em marchin two

un' two, but never takkin o th' flags to theirsels. Th' modest on 'em

had blue veils o'er their face, ut prevented us fro' seein what

they'rn like; an' they'd printed frocks on, made o'th' same shape,

an' nearly o'th' same pattern o' print. I wish they'd begin a-wearin

th' same sort i' our country, an' could look as cleean. Th' faces we

seed bare wurno' exactly o' my sort. Ther no apple cheeks; no

dimpled chins; no e'en rowlin about wi' that sort o' wickedness ut

makes a lad feel like a dampt foo, an' act like one; no clogs, wi'

summat just above th' insteps neaw an' then peepin fro' under th'

region o' frills like a pair o' white mice. Nawe, nowt o' that sort.

They look like machine-made uns, so mich a dozen, an' two an' a

hauve per cent off when th' bill's paid. Believe me, or believe me

not, Sal; but I could look at a crowd o' these Lowell "gals,"

without my arm bein drawn to'ard any on em an' thou'll think that's

summat for me.

They tell me these wenches con write books, play th' payano like

angels, an' talk like saints. But I wonder what they'd do wi' a

stockin ut's too much dayleet letten in at one window; if they know

which side of a dumplin is th' reet un; if they could tell when a

loaf wur baked enoogh by feelin at it wi' th' end o' their nose; if

they could mak a new senglet for a youngster out of an owd pair o'

pants; if they could get to know everybody's bizness without gooin

out o'th' house; if they could "skelp" a three-year-owd till he

couldno' sit, an' then give him a buttercake for t' give o'er cryin;

if they could fotch a husbant fro' a " saloon " without leeadin him

by one ear, an' poo a dish out o'th' oon wi' yesterday's porritch in

it for his supper; if they conno' do these things, what's their

larnin an' their music wo'th? Nowt. Lanky lasses for my brass, if

they are a bit noisy-mouthed, an' conno' write books; they con turn

a mon out so ut he'll no' forget whoa he is, an' put him i'th' way

o' knowin he isno' someb'dy elze if he goes whoam late o' neets.

After we'd looked through Lowell, an' seen their blocks o' smookless

factories, we set out for Boston, an' ' long afore we geet theere.

"Now for it," we said to one another; "ruin or dick; baggage or no

baggage." Wi' tremblin clooas, an' insides givin way, we made our

way to th' baggage-reaum as soon as we londed. Hurray! Th' fust

thing ut I clapt my een on wur th' bag ut had slipped me at

Manchester, wi' th' talegraft papper stuck i'th' hondle. I felt like

a lad ut had just escaped a good hoidin when I seed that; an' when

we fund o th' tother things wur reet anybody mit ha' swum i' lager.

Yankeelond wur a grander country by th' hauve then; an' even th'

women wur nicer—bless 'ern!

Wi' hearts as leet as my pockets wur th' day we'rn wed, we drove to

th' Parker House Hotel, wheere thou'd my last letter fro'; an' drank

one another's healths i' lager till we'rn like balloons. Thou may be

sure we geet inside some cleean calico as soon as we could get at

it; an' what wi' that, an' th' swillin we had inside an' out we felt

new made o'er again; and looked so, too. I'd a notion ut we owt to

ha' had a brass knocker a-piece fixed to our waistcoats, we felt,

and looked so grand. We began o' explorin th' city at once. Surely

that wur noane Ameriky; we'rn i' Liverpool. We could see th' ships'

pows, an' "Dicky Sam " marchin down Lime Street, tellin everybody

he's a gentleman afore they con find it out. Th' folk we met, too,

wur summat like what they are awhoam; an' if th' owd red cross had

bin flyin i'stead o'th' stars an' stripes, I should ha' bin axin

what time ther a train to Walmsley Fowt. Here again ther a park i'th'

middle o'th' city. They co'en it a "common;" but I'll leeave thee to

gex how mich of a common it is when we con walk about under trees ut

th' sun conno' get through.

Th' day after wur another blazer, an' we felt it wurr than we did i'

Manchester and Lowell. Ther must ha' bin some thunner about, I thowt,

for th' yeat fairly geet us down. But we'd th' courage to ride as

far as "Bunker's Hill," wheere th' fust Independence battle wur fowt;

but how we geet to th' top I dunno' know, though it's no heer than

th' buildins. However, we geet paid for our wark. Sittin i'th'

shadow o'th' monniment theere, ther a nice breeze coome sweepin fro'

th' sae, an' wafted us better than a Chinese fan. But we had to be

paid back th' tether road afore th' day wur o'er; it happened this

way.

It wur bedtime; an' we'rn i' my sleepin shop, wi' th' windows wide

oppen, tryin to cool oursels wi' lumps o' ice put into a glass, ut

had a "hinder" brown liquor in, for t' melt th' ice so mich sooner.

While we sit theere, gettin a little bit nary freezin point, but

still a mile or two off, we yerd some singin, an' shoutin, an'

thumpin o' tables. We'd seen waiters go past our dur, carryin summat

like glass skittles, wi' white tops; an' we judged by that, an' th'

singin, ut someday wur havin what "Uncle George," at Fall River,

would co "a high old time" on't. We didno' care to doff us while

that wur gooin on; not that we cared for havin anybody's ice beside

our own, but there'd be no chance on us sleepin. We geet on our

feet, an' stretched oursels; then sauntered into th' lobby, an' went

so far as t' peep into th' reaum wheere th' singin wur gooin on. "

Come in!"— an' we didno' need twice axin. Th' two " Britishers " wur

made as welcome as if we'd bin two Presidents; an' we'd our knees

bent under th' table as soon as they used to be at our porritch

time. We soon fund it out what Choose glass skittles, wi' white tops

wur, by feelin at 'em, an' puttin th' smo end downart.

We'rn among a jolly lot. They'rn young chaps fro' th' Harvard

College, havin their yearly dinner, an' they'rnjust i' that state a

men's in when he doesno' care whether he goes whoam or not. They

sung i'th' honour o' owd England; an' we had to get on our hinder

legs. an' thank 'em i' our own way,—makkin use of a decal o' thick

words, ut wouldno' come out o at once.

Ther a young Chinee chap among the lot—" Mon Chain Chung," he're

coed, an' th' son o'th' Governor o' Canton. He sung a Chinee song ut

I didno' quite understood, an' Sammy said it wur a bit out o' his

line. But we clapt, an' thumpt, an' shouted as if we knew every

word, an' had never yerd it better sung. Th' company, o' somehow,

kept gettin less till we'rn left by oursels, an' strange, someb'dy

had browt a wesh-stand an' dress in -table into th' reaum, an' a bed

had bin put up at back on me. What I took to be Sammy wur a

towel-rail, an' I'd bin axin th'towels, I dunno' know how oft, if

ther any moore ice knockin about. Mornin wur just oppenin one e'e,

an' wur blinkin o'er th' house tops. It wur no use o' me tryin t'

find my own chamber, I thowt, so I'd turn in wheere I wur, an'

chance it. When I wakkent I fund mysel i' my own bed, though how I'd

getten theere wur a puzzle to me; happen one o'th' darkies carried

me while Pre asleep.

I du'stno' goo out ov o day for fear o' having sunstroke, my yead

wur so queer; so I stopt i'th' hotel, an' wrote that letter to thee.

We went out at neet; but it wur like walkin about in a eon; an'

we'rn so done up we wobbled about like two owd wheelbarrows ready

fort' tumble i' pieces. We lit o' " Mon Chain Chung " again, an' it

wur a good job for me; for, when we could howd up no longer, we