|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XVI.

AB'S EIGHTH LETTER CONTINUED.

IN THE ADIRONDACK REGION.

IT wur about

baggin-time when we geet to Albany, wheere we'd th' satisfaction o'

feelin th' air wur a deeal cooler, an' that we should have a chance

of a comfortable stretch-out at neet. We had till th' neet-boat

coome in; an' then th' wharf wur alive an' noisy, an' folk like

picnickers wur grinning through th' sharp mornin' air, an' strowlin

about th' streets as if they didno' know wheere to goo.

We had to be up wi' th' sparrows; for th' train ut had to tak

us on started soon an' we'd a long distance to travel; but ther one

comfort, we'd nobbut our hond bags with us. Th' tother lot

we'd left at Brooklyn. We'd about as pleasant a ride on th'

railroad as any we'd had. Th' country wur nice ut we had to go

through, an' wurno' so dusty as we'd had it i' some journeys.

We'd another glent at th' Mohawk Falls as we passed through Troy,

an' that factory a quarter of a mile long we seed again. Then

we passed through Saratoga, th' Leamington of Ameriky, wheere th'

hotels are some o'th' wonders o' this lond o' wonders, for they're

as big as some o'th' biggest o'

factories. There are moore beds in 'em than con be found i' o th'

city beside.

It wur about noon when we geet to "Glens Falls," wheere we had to

leave th railroad, an' have a gradely owd-fashint ride on an

owd-fashint coach. Noane o' yo'r omblibusses, ut looken like bein

made for flittin house goods, but one like th owd "Red Rover," wheere folk could see summat when they're peearched on th' top. This

had to tak us nine miles on an owd plank road; an' a nice spin we

had. If we'd ridden so far on a road like th' Broadway, i' New York,

we should ha' had every button jowted off our clooas. So how would

our insides ha fared? As it wur we'd a nice chatty company, an'

could yer what one another said. It wur a bit like droivin through

sich a country as there is about Mottram, so thou may be sure we

liked it. I nobbut wanted t' see a face ut wur summat like thine

an' yer someb'dy shout "Come to thy porritch," an' then I should

ha' felt happy.

Our journey's end for that day wur to be "Lake George," wheere we

are now, wi' hardly a soul i'th' hotel beside us, if I dunno' reckon

about a score o' darkie waiters, an' as mony young women gettin' th'

house ready for crowdin time, ut they expected would begin in about

a week. Ther a lot o' darkies shakin carpets in a meadow—carpets ut

anyone on 'em would cover our fowt—an' dust rose i' clouds. I

should think a darkie's face, when it's covered wi' dust, is abeaut

as comikil a seet as con be seen. It's next to bein whitewesht. On th' foot-road leeadin through this meadow we could hardly put afoot

down for treadin on ant hills. We could see hunderts on 'em, wi'

their little holes at th' top ut they used for durs, lyin as thick

as wormholes on a bowlin green. On our road, just before we coome to

th' hotel, we passed th' "Bloody Pond." Here, it's said, that at th'

time o'th' border wars a party o' French soldiers wur camped one

neet, havin their supper, when th' English surprised 'em, an' killed

so mony ut their blood turned th' wayter red. Th Indians about towd

us that, an' I reckon they'd had it fro' their gronfeythers.

This is a grand place, so very different to some parts of Ameriky. It's like bein i' Cumberland, obbut th' lakes are so much bigger,

an' th' hills are green i'stead o' bein grey. We'd a strowl by th'

edge o'th lake for t' watch th' sun set; an' what wi' now an' then

th' chirpin of a whistling frog, an' th' croakin of a water hen, ut

th' Indians co'en th' "Dumplin bird," an' ut maks a noise like th'

workin of a pump, I felt sich a loneliness creep o'er me ut I're

fairly chilled. Beside, ther some Indian farms about, an' I wurno

quite sure ut they're gradely civilized. But they couldno' ha'

getten a scalp off my toppin, chus how.

I'd ha' bowt thee an Indian bonnet if I could ha' carried it safe,

but bein made o' chips it would ha bin smashed int' toothpicks afore

I'd getten it to New York. Thou would ha' looked a bit of a blossom wi' one on thy yead, marchin through Hazlewo'th. Th' childer would

ha' thowt thou'd brokken out of a show wheere ther some penny play-actin

done. It's wonderful how they mak em; an' so is mony a thing they

trucken in.

I fund we'd nobbut come'n to this hotel for lodgins; for this mornin, as I're writin this letter, Sammy o' Moses's comes to me,

an' says—

"Ab, thou mun cut off."*

"What for? " I said,

"Th' boat 'll be off in a two-thri minits; an' it's Sunday t' morn.

We conno' cross th' lake then, an' we ha' not a day to' spare. So

dry up."

______________________

Chasm Hotel, Birmingham, New York State, June 7.

Thou sees I did cut off, an' dry up, too, as Sammy towd me, an' now

I'm gooin in for a finish. I scrambled my papper up at once an' i'

five minits after we'rn on board th' little steamer "Horican," bund

for Ticonderoga, or "Old Ti," as they co'en it. This would be a

grand sail on a fine day, but it wur black an' weet when we set

out; an' a little bit chilly. Our "circus's" wur o' some use then

an' it wur th' fust time they had bin.

A dark weet day in a strange country, an' i'th' wildest part o' that

country, isno' so very comfortin; an' what made it wur, ther no

comfort to be getten on th' boat. But we made th' best we could o'th'

circumstances, an' hutched t'gether under th' awnin', like two

chickens wi' outside berths under th' owd hen's wing, an' spekilated

on it bein' fine th' day after. But as things wur it wur like lookin'

at a grand pictur wi' curtains drawn o'er it; an' we'rn missin one

o'th seets we'd come'n so far to see. Th' mountains, an' th' islands

kept rowlin past us, till when we'd sailed about twenty mile, or a

little above th' hauve road, th' owd sun drew his apporn fro' o'er

his face, an' wi' one of his breetest smiles axt us how we wur.

Then we could see summat—green hills rowlin o'er one another as if

they're playin at rowly-powly, streaks o' sunshoine braidin' 'em wi'

gowd, an' bringin into our seet little white neests o' cottages petcht here and there, as if they'd bin built by some sorts o' brids,

or beavers had larned bow to build their houses wi' green windows to

'em, and had tiny boats for t' goo a-fishin with moored by th' lake

side. A place co'ed "Sabbath Day Point" is so pratty that one mit

forget what day o'th' week it wur, and co every day Sunday. An' everywheere's full o' tales o' wars, an' brushes wi' Indians. As we

passed th' "Hermit Island" I're shown a bit o poetry ut's so good I

know even thou'll like it. It wur th' fust time it had bin i' print, an's co'ed—

|

"THE JESUIT PRIEST; A LEGEND OF LAKE GEORGE."

BY MISS H. M. AMEDEN.

If you ask a story teller

Of this old and ancient legend;

Of this story of the Jesuit;

He would tell you that in old-time,

When the mountains on the lake shore,

And the woods between the mountains,

Were the abode of Indian hunters,

And the wild game of the forest;

When no white man yet had entered

On its waters, blue and tranquil,

That a band of holy Fathers,

In a far-off country eastward,

Had established mission stations,

That the red man of the forest

Might receive the Jesuit customs;

Worship at the Jesuit altars.

He would tell you there was treachery

On the part of many red men;

There was suffering with the Fathers,

There were ugly wars and fightings

'Twixt the different tribes and clansmen.

And the prisoners that were taken

Suffered tortures; suffered torment

Till the life that once burned brightly

Slowly flickered out and perished;

And the Jesuit Fathers suffered

With the suffering like the others.

At the burning stake they perished,

Asking mercy they received not.

Down among the eastern missions

Came a wandering tribe, and hostile;

Waited, till by shrewd and cunning,

They could get a pale-faced captive.

Then with prisoner strings they bound him,

Till his flesh was torn and bleeding,

Set their faces towards the forest,

With their prisoner in among them.

Down beside the Hermit Island,

On Lake George, the eastern shoreway,

Where its mountains yet had never

Echoed to the human voices,

Save the cry of savage warriors,

With their women, and their children.

Out beside a birchen tree-top,

From the shoreway, lone and silent,

Shot a light canoe, and veering,

Landed safe on Hermit Island.

Carefully the boatman landed

Pulled the light canoe to inland

Underneath the brakes and bushes.

But his mien is not a savage,

And his robes are priestly garments.

Now he rises—lifts his bony

Fingers towards the light of heaven;

Then he makes the sign of crosses,

And his lips move as if praying.

After these devotions over,

Down he sinks as if exhausted,

Borne to earth as if to rise not.

Underneath his soiled garments

Forth he draws a much-worn missal;

Looks it over; waits, like doubting;

Turns back to the whitened fly-leaf,

And with pencil writes upon it—

"Pere St. Bernard of the Missions

Of the East has been a prisoner."

Then he writes a brief narration

Of his sufferings and his hardships,

So that if he, wandering, perish,

Some one in the years that follow

May perchance receive the message.

In a hollow stone behind him

Places he that written leaflet;

With a larger stone he covers

Up the message, thinking, hardly,

Will a human hand ere get it?

Half exhausted, half discouraged,

Down he sat alone in silence,

Hardly knowing where to turn him,

Which was safest route to follow.

Then he heard a steady plashing

Of oars upon the water;

Looking towards the western shoreland

Saw a lithe canoe and master

Making towards him in the distance.

Passive sat he in his covert,

Knowing that retreat was useless—

Then as if a new thought gave him

Greater strength and greater courage,

Drew the birch canoe to cover

More concealed than first he placed it.

Then advancing in the sunshine

With a friendly gesture, greeted

Him who landed on the island.

Now the wondering savage listens

Till his greeting was well over.

Then began the painted chieftain;

"Pere St. Bernard, can you tell me

What red man is speaking to you,

How I know the holy Father?

How I know the hungry pale face?

Me forget? The Indian chieftain

Writes not with the pale face's pencil,

But his heart is great, and holds much;

Does not say much, but remembers,

And gives back as he is given.

"Pere St. Bernard! at the eastward

When the red man, not a chieftain,

Quarrelled with your pale face's brother,

It was you who saved my life then.

You have been a prisoner yonder

In another tribe than mine is;

You are faint, and you are hungry,

But the redman not forget you;

You shall come across the water,

Travel with me and my people

Till you come among your brothers

At the eastward where you left them."

So the Hermit Isle, deserted

By the priest and by the chieftain,

Kept its little secret hidden

And if ever you may linger

On the shore of Hermit Island,

At the southward, towards the Lake Head,

You may weave into your fancies

Jesuit Father, Indian chieftain;

They upon the shore then, standing

Just where you stand in the sunlight.

And before you leave the island

Search the hollow rock behind you,

See where lay the hidden message,

Secret of the Hermit Island.

__________________ |

After londin we'rn takken by train to Ticonderoga, wheer we'rn

shipped again for t' cross "Lake Champlain," another run of 130

miles. This lake lies in a flatter country than Lake George,—well,

just about th' wayter; but th' mountain i' th' distance looken

grand.

Then there's th' "Queen City of the Lake," Vermont, wi' its tin

towers glitterin i'th' sun like newly polished ale-warmers, on our

reet, ut shows ther someb'dy beside Indians i' this wilderness. We londed at Port Kent; an' felt a little bit done up wi' our day's

sailin; an' ther an owd shandry waitin for passengers to th' next

city. We scrambled into th' owd leather box, an' gan orders for t'

be dropt at th' "Lake View House," about three mile on th' road. Th'

droiver towd us that hotel wurno' oppent for th' season yet, so we

couldno' get in. Ther th' Chasm Hotel across th' river we could

happen bunk theere. Any port in a storm but if th' hotels wur owt

like the country we'rn gooin through there'd be thin pastur, for th'

fields about had hardly a tuft o' grass to th' square yard.

When we began a-gooin down th' broo th' lond looked better, an' when

we geet to th' bottom we could see an' yer ut we hadno' come'n for

nowt. Birmingham lies here in a little neest, wi' a nail factory for

t' keep everybody ut lives theere. We'd a glent at th' Falls as we

crossed th' river, an' as neet wur closin in th' chasm looked a

fearful hole. Our hearse pood up at an owd house ut favvort havin th'

windows nailed up, an' we'rn towd ut that wur th' Chasm Hotel. It

made my flesh creep for t' look at it; an' Sammy's face wur as

blank as if ther a boggart at th' door.

"I'm no' gooin i' that shop till I know sommat about it," he said,

lookin th' picture o' disappointment. "Ab, get out an' punce th'

dur, for t' see if there's owt wick about beside ettercrops. If not we'n goo on."

I tumbled down an' mounted th' step, then geet howd of a knocker ut

favvort bein made out of an owd reawsty quoit, an' leet it bang

again th' dur. It made sich a strange sound ut I jumpt back, an'

would ha' run away if there'd bin nob'dy wi' me. But th' dur oppent,

an' a face showed itsel ut put me i' mind o' owd "silver-yead." Th'

body it wur fixed on wur tall an' lank, an' it nobbut wanted a

candle inside, I thowt, for t' ha' made it int' a lantern. I axt him

if he could tak two travellers in, an' he said he could, tho' they

hadno' oppent yet. Seein ut I looked a bit down about th' place, he

axt me to took through an' satisfy mysel about it. I towd Sammy an'

th' coachman for t' keep their ears oppen, an' if they yerd a shout

owt like "murder" they'd know what to do; then wi' a sinkin pluck

I ventured into th' owd castle.

Ther just enoogh o' leet when th' windows wur unbooarded for t' let

me see what th' place wur like. Strange, it wur as cozy a shop as

any we'd bin into, booath upstairs and down; an' when I seed two as

bonny wenches as any we'd met, I said to mysel, "I'm gooin t' let

my anchor down here whether Sammy does or not." I took my report to

Sammy, an' he didno' want mich coaxin for t' turn in, as we'rn

booath on us quite fagged out. We'rn as comfortable as two

sondknockers directly; an' when th' supper wur ready, an' th'

wenches wur cotterin about us wi' cleean apporns on, then no two

Yankees could ha' made theirsels feel moore awhoam than we did. We'rn a little bit dropt on, too, when we axt for a lager apiece,

an' wur towd it wur a teetotal shop. Ther nowt nobbut bed for us,

after supper; so we turned in i' good time, an' slummert soundly

till mornin. Noather boggarts nor robbers disturbed us.

I'th' mornin we emptied th' hencote of o th' eggs they had, an'

flung some good sweet ham after 'em, an' then we felt quite ready

for what th' day mit bring us. Th' landlort towd us visitors wurno'

allowed into the Chasm o Sundays; an' that wur a bit of a damper

for us: we should ha' to stop another day. But we could see a part on't fro' th' bridge; so we'd go down that road. When we geet back

we fund th' londlort had bin out, too, an' he gan us th' welcome

news ut he'd getten leeave for us to go through th' Chasm that day,

an' a guide would goo wi' us. He said it wur becose we'rn Britishers. Th' owd chap looked quite another mon i' our een then; for he

favvort he'd ha' done owt for us.

We set off at once to the Chasm House, wheere we met th' guide. A

young woman leet us in, an' oppent a dur ut led to a "stairway." We'rn towd to look at nowt nobbut th' steps as we went down, as a

slip o'th foot would be th' last we should ever mak i' our lives. That advice wur so comfortin ut I said I'd wait at th' top till they

coome back; but as Sammy said if I didno follow he'd turn back and

throw me down, I thowt I mit as weel mak use of a chance; so I

followed.

Lorgus o me, Sarah! when we geet to th' bottom o'th' stairs, an'

looked up an down, I felt o of a tremble. We'rn like between two

walls o' rock 200 feet hee, an' lookin so close t'gether ut they

could whisper to one another. Between these two walls a river rushes

at th' rate of about 15 miles an hour; an' th' guide towd us that i'

some places it wur 70 feet deep. This Chasm conno be a rift. There's

nowhere for th' rocks to set back to. It must ha' bin worn an' weshed out wi' th' river; un it must ha' takken ages upo' ages to

do it. At one place there's a bend, an' here it's made a big

chamber, ut reminds one o'th' Whirlpool Rapids at Niagara. Close to

this there's a big cave they co'en th' "Devil's oven" an' it looks

as if Owd Nick had baked his dinner in it some time. Then there's a nattural stairway made o' ledges o' rock; and this is coed "Jacob's ladder." I shouldno' like to try t' mount it. It would be

odds again thee seein' me again if I did. We had to walk by ledges

o' rock, like shelves; an' every time we stirred a foot we'rn towd

not to look down. At some places wooden galleries are fixed,

wheere if a nail slipped it would be wo-up!

|

|

|

The Ausable Chasm – A deep gorge carved by the Ausable

River.

Source: Wikipedia. |

When we'd walked, or rayther crept, about a quarter of a mile—it mit

be a hauve a one—we'rn led down some stairs to th' edge o'th river. Here they a little boat fastened up, an' we'rn towd to get into it. As I couldno' be i' greater danger than I'd bin in, I tottered into

th' boat, an' tried to balance mysel'. Then Sammy followed, an' it wur same as teemin a looad o' coals in it. I felt like as if I'd

fast howd o' mysel, an' doestno' leeave lose. Then we shot off down th' river at a rate ut made me mazy—shot some rapids neck-or-nowt,

till we geet to a hole ut I thowt would be my last restin-place, for

it seemed to be throwin out its arms for t' get howd on us.

"Surely we're no' gooin i' that hole," I bawked out.

"No," th' guide said. An' he turned his boat into a bit of a creek,

an' I took my wynt again.

"Is there no plan o' getting back nobbut gooin th' same road as we'n

come'n?" I said to th' guide.

"You can't go the same way back," he said. "It's as much as I can

do to pull myself back by that rope." An' he pointed to a rope ut

wur laid by th' rock side, like a taligraft wire. "You can go by a

footpath along here."

"Thank thee," I said. "I've no doubt but thou'rt a dacent lad o'

someb'dy's. If I had thee at th' owd Bell, thou should have a sope

o'th' best there is."

We left him, an' wi' mich ado climbed th' rocks, an' londed safely

out o'th Chasm after gooin through about a mile on't, an' feelin i'

sich a pickle as I never meean bein in again.

This is th' last ventur' upo' th' list. Th' next move 'll be for whoam. So, by-bye, till thou sees th' face o' thy prodigal husbant, AB.

* Cutting off among weavers means they must take in as much cloth as

they have woven, when such cloth is urgently wanted.—B. B.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XVII. AND CONCLUSION.

A GREAT EVENT—HOMEWARD BOUND—HOME AGAIN.

_________________

|

'Tis sweet to hear the watch-dog's honest bark

Bay deep-mouthed welcome as we draw near home;

'Tis sweet to know there is an eye will mark

Our coming, and look brighter when we come.

LORD

BYRON. |

WE are again in

the city of Paterson, New Jersey; and our friend "Ab" is relating

some of his adventures with, I am afraid, a little tendency towards

drawing the long bow. "Sammy o' Moses's" is enjoying over again most

of these adventures, giving now and again a shrug of the shoulders,

as much as to say—"Abram, thou'rt ridin thy big hoss." Pipe-breaking

"Frank" is again with us, colouring a new meerschaum, and

regretting that he did not "do" the whole tour, instead of

"lotus-eating" on the Passaic Falls. "Will o' Jimmy's" and his wife—a

very dear cousin of mine—are manifesting their delight in real

Lancashire fashion; and other members of a once closely knit family

are listening with the air of mixed doubt and credulity with which

the recital of strange adventures is sometimes received. And there

are present several gentlemen of high standing in the city,—aldermen

and councilmen and officials of the corporation, come to welcome the

"Britishers" on the completion of their 4,000 miles tour.

There are to be "high jinks" in the city: I am to have a grand

"reception" at the Opera House; and every preparation for the event

has been made. Whilst we have been travelling east and west,

Anglo-American citizens have been busy to give the occasion a

national importance, as may be gathered from the following paragraph

which appeared in the Evening Press of June 1st: "Anglo-Americans

interested in the Lancashire poet and dialectician, Ben Brierley,

will meet at the City Hall this evening to arrange for a fitting

reception on his return from his western trip, about the 7th." Large

posters are on the walls; and my name, along with the line,

"Memories of Old Lancashire," is conspicuously blazoned forth. The

English element is actively astir, for the event is to come off on

the morrow. There have been doubts as to whether we should turn up

in time, as nothing had been heard of us during the past fortnight. Newspapers have been busy with gossip; but the

Daily Guardian sets

the public at rest by announcing in its issue of June 9th:—"Mr.

Brierley returned last evening, after a pleasant tour through the

eastern States, Niagra Falls, and other places of attraction in that

direction." But rumour had gone before, and that occasioned this

gathering. A merry one it is, and full of enthusiasm about the

proceedings so soon to be inaugurated. There is singing and reciting

and Will o' Jimmy's is again on the platform at the "old school"

in his native Failsworth, telling the audience assembled there that

his "name is Norval," and that, "on the Grampian Hills,

his father

feeds his flocks."

The morn hath come, and with it unusual bustle. The time of our

departure for England is drawing near, and we have many friends,

some of them new ones, to see and take leave of. It is now the ninth

of June, and we leave New York on the twelfth. On the evening of

this day, and that of to-morrow, I have to give "Readings" in the

Opera House: that is the form the reception is to take. I am

exceedingly nervous as to the success, but am assured that it will

be most flattering.

The day is drawing to a close, and there is a carriage at the door. Nervousness is on the increase. The event not having been looked

forward to when I left home, I have no "dress" suit to appear

in—nothing but my "navy blue," which will look much out of place on

a platform. No matter; the ordeal has to be passed through, and I

must gird up my loins to face it.

I am at the "wing" of the Opera House stage, waiting for my "cue,"

and there is a cheering hum of voices in front. It is an anxious

moment when the chairman, ex-Mayor Buckley, rises to announce me. And now I must write in the past tense, as the affair has become

historical.

I had on my appearance a reception that at first appalled me. There

was a perfect hurricane of voices, and the hand applause came with a

crashing sound. My whole system was shaken as if by electricity; and

the fear that after all I might be a disappointment made my heart

sink within me.

But when the choir burst forth with—"Shall auld acquaintance be

forgot?"—in which the audience joined, another feeling came over me,

and confidence followed. Surely I could not be in America, was the

dominant impression; this must be a Lancashire Theatre, and all

these people before me sons and daughters of old "John of Gaunt." There were many faces that I had seen before—ay, "three thousand

miles away;" and the gap of time and distance had been bridged over

by a very pleasing structure. At the very first utterance I found I

"had them," as professionals say; and I kept my grip of them the

rest of the evening. It was the night of all nights during the whole

of my career. The audience were not only excited by hearing the old

familiar talk, but they looked on me as having brought in my person

a gleam from the bright firesides of their native land; and tears

and laughter sprang from their fountains at the same moment. It was

worth going to America for to have seen, and been the object of,

that demonstration.

The night following I had the pleasure of standing before the same

faces again, and on the same platform. The enthusiasm of the former

occasion repeated itself; and a never-to-be-forgotten experience

came to an end. I had some difficulty in getting away when all was

over. The hand-shaking I had to go through, and the many farewells

that had to be uttered, was an entertainment of quite another kind.

I had the satisfaction of hearing, before I left the city, that a

handsome sum would be handed over to the funds of the Paterson

Orphan Asylum, as the result of the second night's entertainment.

I have awakened out of a bright dream and we are treading at

midnight the silent streets of New York, on the way to our

temporary ocean home, the "City of Berlin," which sails on the

morrow. There is not the silence of the streets on that crowded

wharf, for the good ship is lading. Wherever all the cargo lying

about is to be stowed is a marvel to us; but it is rapidly

disappearing. "We sleep on board, to-night, captain." "All right!" We climb the gangway, and are again among familiar scenes. We must

have lived there for years, every corner and every face is so mixed

up in our memories. Our baggage is bundled into our stateroom;

and little Johnny Hughes is proud to be our berth-steward. Why, we

must belong to the ship's company, we are so heartily greeted. We

meet the doctor, and the two Bridges, and "Walter," and that dry

"auld" North Briton, "Cam'll," the chief engineer—hands all round. Were it not that we were tired we would have a "high old time of

it." But our wanderings are over; and we are "homeward bound." A

nine days' rest we feel will be welcome; and the first stretch in

our berths is quite refreshing. Notwithstanding there is a noise

going on as if the enemy was boarding us, it cannot keep off sleep,

nor the dreams that attend it.

"Away; nor let me loiter in my song!"

It is a bright Saturday morning; and there is a large crowd on the

wharf. Our Brooklyn friends are there, and we hail them; and somehow

a box of cigars is passed to us. Many anxious eyes are strained

towards the vessel to catch glimpses of friends, most of whom are

leaving home for a tour through Europe.

The gangway is withdrawn and the first throb of a pulsation that

seems as if it would never cease lifts us on our uncertain way. What

handkerchiefs are waved from wharf and boats, and cheers grow faint

as the shore recedes! Our friend Ab was in one of his moods; and as

a familiar object disappeared from view he unburdened himself in

this strain—

"Thou'rt a big country, an' thou's some big folk. Some would be thowt big ut are no' becose talk conno' mak 'em so. If it could it

would have to do. Ther's a good deeal o' things about thee ut I

like; an' some I dunno' care for. If we'd thy wayter—but that

couldno' be, becose one o' thy lakes would swamp us, an' put us

cleean out o' seet. But if we'd thy Niagara it ud ha' to do moore

wark than it does. We wouldno' have as mony long chimdies as we han;

nor as mich reech flyin about. It ud give us a chance o' havin trees

as green as thine; an' buildins as cleean outside. If we'd as mony

blessins i' wayter, an' lond, an' sun, an' sweet air, as thou con

give, we wouldno' be feart o' other folk threshin us i' noather wark

nor nowt elze. We wouldno' ax nob'dy to pay duty to us, for t' keep

up prices, an' help to carry th' gover'ment on. We'd mak it so ut

nob'dy could lick us, without protection. Thou'rt a fair lond,

Ameriky; grand for a trip like ours; but I deaut if ever thou're

intended for white folk to live in. They gotten too mich loce skin

about their jaws when they'n bin here a year or two for to mak me

think thou suits 'em. If it wurno' for

so mich new blood bein poured in fro' England, an' Garmany, an'

Paddy's land, it wouldno' be mony hundert year afore th' Red Skins

wur th' mesthers o'th' job again. But tak thee as thou art, thou'rt

a pattern of a new wo'ld; an' some owd uns mit tak lessons fro'

thee. Farewell, Yankee Doodle; we're gooin a-seem th' owd pot-lion

again!"

Our voyage home partook very much of the character of our voyage

out, so far as the sailing and the incidents on board may be taken

into account. There was, however, this difference in our

fellow-voyagers—we had a greater number of saloon passengers, and

considerably fewer in the steerage. But although we were going home

the time did not pass over half so pleasantly as when we were going

away. Most of our companions were Yankees, of that insufferable type

only to be met with in their true character on board ship. Selfish

and unsocial, their society was not to be courted; and the manner in

which they appropriated the deck for their spoiled partners, to the

exclusion and annoyance of everybody beside, was a mean and

disgusting exhibition of assumed privilege. There, on deck chairs,

lay strong women from morn till night, swathed in shawls and

wrappers; their husbands dancing about them always, so as not to be

one step behind in their attentions, and by the slightest neglect

draw down petticoat wrath. Their meals had to be brought to them;

and the manner in which the eatables were disposed of would not have

been one of the most welcome sights to a person inclined to

sea-sickness. Had these people been unwell they would have had our

sympathy. But they were as well as we; and the sea never was rough. We had none such a company going out. We made up quite a happy

family—mixed freely and sociably with each other; and created

friendships that will not readily be forgotten. Our friend Ab and a

jolly Scotch-Yorkshire farmer from the neighbourhood of Rotherham

conspired to overthrow these deck-squatters by accidentally tumbling

among them; but they did not carry their design into effect.

Our friend the grower of corn was the life of our party going out,

and it was with unfeigned delight that we hailed his presence on

board on our return. He was rich in jest and story, and Ab and he "foregathered" oft. He knew how to use an "eish plant" effectively

to protect his growing corn, and the anecdotes he told of his

prowess in that capacity made the Yankees envy us our fun.

"We wanten oather an ask plant or a pair o' clogs here," remarked Ab,

as he took a survey of the crowded deck, from their joint seat on

the chain guard. "Nowt like a bit o' timber for makkin folk stond

furr. If my owd smoothin iron wur here, hoo'd mak a clearance i'

yond cote smartly. There'd be a cat among th' pigeons afore they

could shake a wing, an' if they didno' offer to get out o'th' road,

feathers would begin a flyin. Nowt like some women for settin others

reet."

Late one evening—I am not sure whether we had then cleared the

"banks" of Newfoundland or not—I was sitting upon the upper deck

alone, contemplating the sky, which was a marvel of stellar display. The captain was pacing to and fro a few yards from me, evidently on

the look-out for some special object, as he knew from information he

had received in New York that the sea was not yet clear of icebergs. Seeing me alone he crept under the rope to join me for a short time. We had a pleasant chat together, and the captain, being a Scotchman, recited "Tam o' Shanter," giving all the pith of the racy

Lowland dialect in a manner that I had never heard before. Almost as

suddenly as if a door had been opened the temperature fell. The air

was quite winterly.

"I shall have to stay on deck to-night," the captain said, and he

got up from his seat and left me. Were we to have a storm, I

wondered.

Not feeling over comfortable about the matter, I retired to my

birth, where I lay awake for some time; but not noticing any

perceptible increase in the motion of the vessel, I suppose

confidence asserted her sway, and I dozed over. In the morning I was

awakened by a loud knocking at our stateroom door, followed by a

vigorous salute from the steward.

"Mr. Brierley, icebergs in sight!" That was all.

I sprang out of my berth with unwonted alacrity, for I occupied the

top shelf, and managed this time without the assistance of my "elevator," which was my portmanteau set on one end. My "bunk mate" I

found was already abroad. Half dressed I rushed on deck, and from

thence saw the floating mountains—four of them—a few miles distant

on our larboard bow. We had sailed eighty miles out of our course to

avoid them. In the farther distance they had the dark blue tint of

our own land mountains, but as we neared them they changed one by

one into huge rocks of quartz, that threw back the rays of the sun

as if from a focussed glass; shifting and brightening up where had

been shadow, as the mighty agents of destruction moved over the

deep. As we parted company they again wrapped themselves in their

mountain blue, and we were, not sorry that they had taken their

departure so peaceably.

We had yet another sight in store for us ere the day was spent; a

pair of whales came frolicking through the "briny," and spouting

jets of water from their "blow-holes" to an immense height. Ab

could not see of what use they could be, because he was sure they'd

never have any fires to put out.

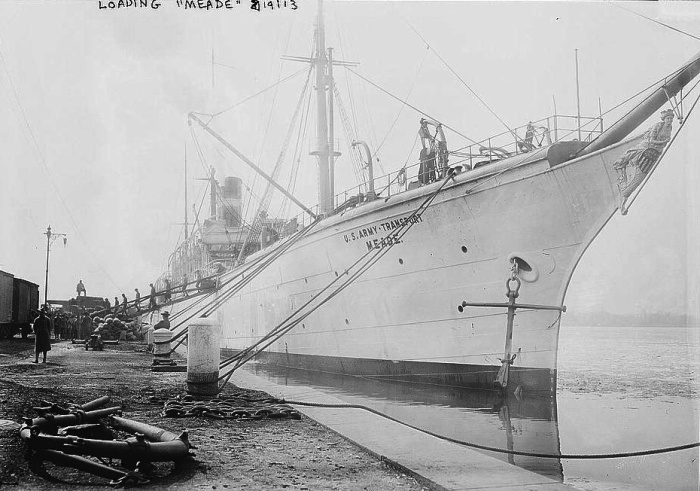

|

|

|

Inman Line's "City of Berlin" in her final role.

Source: Library of Congress. |

We made a splendid passage; and although the sea was not exactly

what we often hear described as being like a "mill-pond," the steady

purpose of the "City of Berlin" made up for the difference, by taking

each wave as a bull would take a dog, and tossing it out of the way. It was our second Sunday as we sailed along the shores of "ould

Ireland," the sight of which made our voices rise in thankfulness

when at service, which on this occasion was led by the dean of

Chester. Another night on board, and then "Thy shores, fair Albion,"

would greet our gladdened eyes, and the welcoming hands of dear ones

would be clasped about us.

"It is the morn;" but we are yet far from port, though the "Skerries" are past, and the blue mountains on the Welsh coast are

in sight. And what is that speck on our bow? Nearer it comes, and

larger it grows. It is the tender coming to meet us. The tide is

out, and our vessel cannot pass the bar. What hearts are beating;

and how strained eyes are peering in the distance, as if to discover

some face that was the light of home! Suddenly our friend Ab

exclaims—

"Theere hoo is! I knew hoo'd come. Dunno' tak any notice o' my

pranks now, for I'm not mysel'. Her face isno' a bit autured. Now hoo's seen me; an' th' sun's shoinin as it never shoined before. Mind out, I'm gooin t' have a jump if they dunno' shape better at

comin close. Bang!"

It were fit I draw the curtain here; for there are moments in the

lives of men and women that should be consecrated to the sight of

the Almighty alone; and these moments were of them. Farewell all of

you, fellow-voyagers! If a touch of nature has not made us kin,

dangers shared in common have made us of one family.

――――♦――――

SECOND TRIP.

CHAPTER I.

A LIVELY TIME ON THE ATLANTIC.

TO undertake a

journey of many thousands of miles, and start on the first of May,

which the poets of old were wont to laud so much, but which is now

no more genial than the first of January, is not a circumstance

calculated to put a man in the best of spirits, especially when he

has to perform that journey alone, and cannot boast the youthful

blood of thirty. With the cold and the rain, and the gloom of the

day of village queens, garlands, and "bell horses," the day on

which I sailed for New York, heralded by forecasts of immediate

storms, inspired me with a doubt as to whether I had acted wisely in

selecting that date upon which to commence my journey. But it had

been chosen a month before, when fruit trees were white with

blossoms, and lanes were bright with the favourite flower of the

late Lord Beaconsfield, and everything in nature betokened the early

advent of

summer. Why, I might have reasoned, after such a promise of a

splendid time, should we fall back upon the cold and bluster of

March? As well might we have expected the temperature of the

dog-days. But we did return to it.

As I paced the streets of Liverpool, with my wife on my arm, and in

company with others, amongst whom was a true and genial friend, once

a fellow voyager to the land for which I was now bound, then looked

on the bleak ruffled surface of the Mersey, I would not have

objected being taken into custody, and subjected to a period of

"false imprisonment," if I could have obtained damages to the amount

of thirty-five guineas, and costs. I could not have blamed myself if

my trip had been compulsorily deferred. But I had set my

fortune—aye, my life upon the cast, and must stand the hazard of the

die. There was no backing out of the situation, even if cowardice

had prompted such a proceeding: I must go.

Cold blew the wind, and colder beat the rain, as

we stepped upon the tender that was to bear us to the Inman

Company's steamer, the City

of Berlin, then lying out about four miles down the river. Inhospitable looked the black sides of the huge ship, with rain

pouring down them like tears, and the windows glaring at me with a

watery glare, as if they were so many eyes of a monster waiting to

get me into its clutches. But when I had inspected my berth, which

was the one I occupied four years ago, and renewed my acquaintance

with the comfort-suggesting and splendidly furnished saloon, my

spirits went up a few degrees; but my heart did not bound. The

bustle on deck, where luggage was being knocked about as if to try

the strength of the various cases that contained it, and the

satisfaction that I had not to part with my wife and friends until

we reached Queenstown, instilled a little bravado into my breast,

and I defied both wind and rain, and even challenged mal de mer

to come at once and attack me.

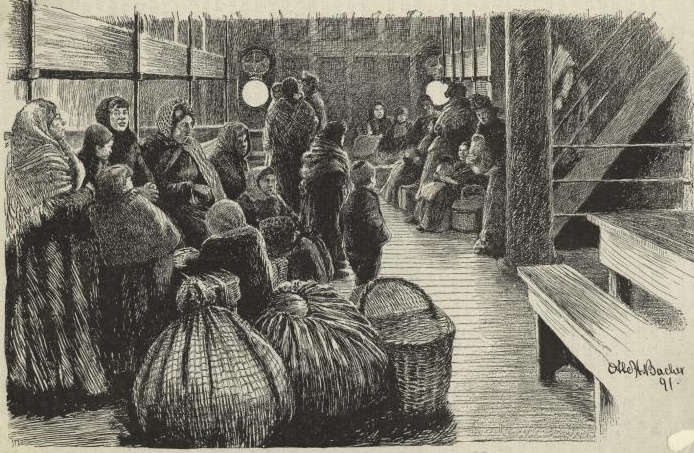

It was a curious if not a saddening sight to see, outside all this

lively turmoil, faces peering from behind the "ropes" with

something like the interest expressed in them that we occasionally

notice in the straining eyes of cattle packed like ripe peas in

their husk, in a railway truck, and watching proceedings they cannot

comprehend the import of, yet feel a curiosity to know. These faces

belonged to emigrants from the north-east—Norwegians, Danes and

Swedes; the fair hair of the Scandinavian girls flowing freely when

not covered with a shawl. Bonnets there were none; and hats were

few. I felt concerned as to what their feelings were in a strange

land, the people speaking a strange tongue, and yet three thousand

miles from their destination in another strange land—and what would

they do when they got there. Some of these foreigners were handsome,

and many would compare favourably with the average of our English

girls; whilst for health and strength, and fitness to be sent out to

colonize a wilderness, I have not seen any to come up with them.

The appearance of these people caused me to reason with myself. Here

was I, fitted out with the means of every physical comfort that

could be desired, with a palace for my home, and fare as good as any

hotel could provide, and with friends to greet me when I land; and

yet, what a miserable dog I feel. I am afraid I should make a poor

traveller for the sake of travelling.

None of these emigrants appeared to be in the least downcast in even

that trying weather; but their faces were bright, as it seemed, with

hope; and there was a vein of jollity running through the group that

was not apparent among their better-to-do fellow voyagers. There was

not much time for my friends to look through the ship; but when my

wife saw the cosy berth that had been assigned to her use, she

wished, for the first time, that she was going with me the whole of

the voyage. Could she have fore-known what I and others had to pass

through before we landed at New York, she would have wished she had

accepted the invitation to visit Killarney, in preference to running

the risk of ever seeing Niagara.

I had a spell of sea-sickness before we reached Queenstown, but a

few hours on land, and a drive out into the country, made me believe

I was all right again; and in the evening I faced the dinner table,

in a way, too, that might have led other diners to think I was going

to eat the tablecloth. This was Friday; and it was twenty-four

hours, or more, ere I could face that table again. We had a dreadful

night. The wind we encountered at Queenstown had on its way lashed

the sea into a rebellion of water and I felt that an early

retirement from the deck was safer than remaining, as "breakwaters"

were being placed at the doors and "Richard" looked troubled. It

was an almost sleepless night with most of us. I was afraid, not of

the ship's safety, but of being pitched out of my berth. My window

was as if being washed by a two-inch hosepipe. In the darkness my

hat flew across the room like a bird of ill omen, and this incident

did not add to my equanimity.

The whole of Saturday the sea continued in its rebellious state, and

the deck was clear of human life, save of a few emigrants who

preferred to huddle in a corner to being downstairs, where the

experience must have been of the most sickening kind. Before the

effects of the gale were fully developed, although the wind was

intensely cold, these hardy sons and daughters of the Fjords were

dancing merrily to the music of the concertina, if dancing it could

be called that was nothing more than a bobbing up and down and a

shaking of dishevelled hair. Possibly they had been used to cold and

kindred sorts of weather in their "ain countrie."

|

|

|

In the steerage (1891).

Source: New York Public Library. |

The cock of the deck, who could stand anything, and would like to

plant a flag at the top of the North Pole, succumbed at last, and it

was sometime before we heard of him again; when he did make his

appearance the starch had been washed out of him, and his body and

spirits were limp. He no longer strutted majestically about the deck

and sighed for the North Pole.

My sickness returned to me with ten-fold virulence, and I had to

keep to my room the whole of the day, stretched upon the couch, and

declining with a shudder every invitation to meals. Most of the

following night the sea kept on its mad career, and I was afraid it

would never be induced to listen to good counsels. When the morrow

came there was a perceptible moderating of the offended Atlantic's

fury, but the deck was still deserted, and so were the tables. I had

a cup of tea and a bit of dry toast in my room, but it took me all

day to get myself into anything like "form." By degrees the

drowsiness that brings not sleep left me, and I returned to my

stateroom, feeling like one who had been suffering from delirium and

was wakening out of it. I was ready again to face the table. From my

miserable setting out I began to have a flow of good spirits, and

the sea now behaving itself, I felt as if land was made for only

women and carriages and pug dogs. The elements seemed to know that

it was the Sabbath, so put on their Sunday clothes. But we seemed to

have forgotten, as we had no service that morning. The

should-have-been worshippers preferred bodily comfort to spiritual

duty, and were still in their wraps and overcoats, the latter with

the "sideboards" up, as if intended for "breakwaters." Still they

lay in a listless state wherever a seat could be made into a couch. The waves, however, had howled and kicked themselves to sleep, like

big, naughty children. Our vessel seemed to rest too, and it

deserved its repose after receiving the charges and cutting through

the ranks of King Neptune's merciless battalions.

It now became a pleasure to look out upon the deep, watching the

slabs of green and white marble float past, displaying such patterns

as no artificer in real stone could ever hope to imitate, and all so

varied that not one could be reproduced in millions of years, and

possibly never. These slabs were fringed with sprays of white coral,

fitting tablets for such a grave.

We had been three days out before my fellow passengers had had an

opportunity of becoming acquainted with each other, and it was

amusing to see with what an owlish stare they met and spoke. They

had had too much to do in looking after themselves, immured in their

little prison homes, to devote any time to social intercourse. But

now they came out like butterflies in summer, flitting around with

friendly greetings that were no less hearty from their having been

compulsory reserved. Everybody wanted to know everybody; and

although several spoke a foreign language it did not seem to matter;

somehow they got at each other. Children danced and rolicked in the

sun—when there was any—but even dullness was sunshine compared to

what we had been accustomed to, and was welcome, too, so that no one

provoked the ire of the autocrat of the deep. Some found new

fathers, and for a time preferred them to the old ones; and flirting

behind the wheel-house came all at once into season. But the season

was a short one, as will be seen a little further on.

The comparative calm was succeeded by a dense fog on the Monday. It

was dangerous for the vessel to go at full speed. So it went on its

hands and knees while the curtains were down, and crawled along. As

a matter of course, little progress was made during the fall of this

semi-night. An old lady who had not yet got over the terror of the

gale, on hearing that there was more danger in a fog than in a

storm, accosted me with, "Do you think we shall ever land? " "Well,"

I replied, "if we don't come into collision with another vessel, or

an iceberg, the probability is we shall land sometime. At this speed

it would be about the end of July. This fog is a sign that there are

no more gales ahead, and if it will lift we may have a good time." I

am afraid that in my prediction the wish was father to the thought.

"Thank you," said the old lady, and she looked thankful, "I'm

getting tired of this kind of work. I was told that this was the

best time to cross the Atlantic. Whatever must the worst be like?"

and the old girl subsided with a gleam of satisfaction in her face.

It somehow happened that my prediction came true. Tuesday morning

was bright and calm. Again the moths that fly about the saloon

fluttered up to the deck and we had "society" until lunch time.

|

"But pleasures are like poppies spread;

We seize the flower—the bloom is shed.

Or like the Borealis race,

That flit ere we can name the place." |

A bright morning, even in England, the sunniest (?) clime in the

world, is not to be trusted, especially if it be very bright, for

then the sun is shining through a thin vapour, like a bright eye

glancing through a tear. About mid-day the sun left the watch, and

the cold took its place. The saloon moths fluttered on deck until

wraps were of little use, then were seen no more in the upper

world—poor things! But the hardy bees behind the "ropes" hummed and

buzzed as merrily as if they were in a field of flowering clover on

a warm sunny day; and this difference confirmed an opinion I have

long held that luxuries stand in the way of real pleasures.

Rain followed, and kept company with the cold. Our newspapers had

been read and re-read until their appearance was such that they

might have done a year or two's service round a copper kettle, and

as every subject for debate had been exhausted it was either saloon

or bed we chose the former. But the sea was getting up again, and no

one could stand to sing. We abandoned the idea of a concert when we

saw that it was impossible to hold one, and dribbled off to bed,

with sore forebodings for the night. Our worst fears were realized. The gale rapidly gathered in strength, and the waves began to play

leapfrog in the most defiant and demon-like fashion. I retired to

bed early, preferring to be "rocked in the cradle of the deep" under

blankets to being knocked about from pillar to pillar in the saloon,

notwithstanding its electric lights, its brilliant bouquets of many

coloured glasses that were swinging to and fro in an airy dance, and

the chairs pirouetting like the automaton figures we sometimes see

on the top of a musical box. I slept soundly until a little after

six, when my sleep was broken by a strange, and certainly unearthly

noise. It came with a bang—went on with a swis-s-s-sh-sh-sh—and was

followed by a gurgle, as though the ship had been scuttled. I sprang

out of bed,—or rather, I allowed myself to be tumbled out—flung open

my stateroom door, when I had a sort of pleasure in seeing the

passage converted into a brook that would have delighted my

childhood's days. We had shipped an enormous sea. Poor barber! two

hours after he had not finished lading and mopping his little shop. "This reminds me," said my next door cabin neighbour,

"of what I

once heard my father say, a man who goes to sea for pleasure ought

to go to h—l for pastime." Notwithstanding all this I was ready for

breakfast as soon as it was ready for me—quite an unusual thing. But

I could not fall to without Daddy Neptune having a "marlock" with

me. He tumbled my eggs upon the tablecloth and smashed them, a

portion of the yolk flying up my sleeve, nearly reaching my elbow. My tea-cup was turned topsy-turvy (so were others), and my tea-pot

was rolling about like a billiard ball, and "cannoning" against my

neighbours.

But to me, then, there was fun in all this, as I had got over my

constant trouble, my liver doing its work properly, and could have

enjoyed anything short of wreck. But the best fun I had of this kind

was chasing a shirt stud in my state-room, when the ship was rolling

its worst. This incident reminds me of a chase after a cockroach my

wife and the servant once engaged in. This insect belonged to a

breed of racers, and defied pursuit. It was in vain they crashed

among fire irons, chair legs, table legs, making raids upon boots,

and demolishing cinders, the pest continued to elude the vengeful

slipper; so the pursuing party gave up the chase. "Missis," observed

the girl, as they were getting back their breath, "I think yo'

didn't cop it." It was the same with my stud, I "didn't cop it "

until two days after, when it rolled out of its hiding place, and

allowed me to pick it up without further chasing. It is provoking

enough when a stud rolls under your dressing-table at home; but when

you have to go on your knees, and peep under your berth,—the vessel

rolling at the time—and see the little fugitive winking at you as

far in the distance as it can get, and you wrench a lath from your

bed to use as a rake just in time to see something bright roll past

you, and take refuge under the couch, it then becomes a question of

either fun or profanity. I chose the former, and had a good laugh at

the incident. A fellow voyager, to whom I related the circumstance,

observed, "Well, you can boast of something that perhaps no other

man can: it isn't everybody who can wear an Atlantic roller in his

shirt front." I dropped my "nose-pincers" in the same manner, and

they must have instantly slipped out of sight. But the following

morning I saw something glitter on the carpet, and that seemed to be

slowly working its way across with a pair of oval arms. The thing

turned out to be my glasses.

The gale continued the whole of Wednesday, and there was no getting

about from one place to another without great difficulty, and a

little risk. I did manage to scramble upstairs to the smoke-room by

holding on from pillar to pillar, as a child learns to walk by going

from chair to chair. But when I got upstairs I found that things

there were no better than they were below. The water was playing at

"Johnny Lingo," rushing from one side to the other as the ship

rolled; and defying all the efforts of "Richard" and his assistants

to get clear of it. An elderly gentleman whom I took to be a

Russian, but spoke tolerable English, I had noticed could pace the

deck with the ease of one accustomed to the sea. This gentleman came

splashing into the room to light his cigarette; but he had no sooner

stepped on the wet boards than their slipperiness betrayed him. All

on a sudden his feet shot out, and he was laid as flat on his back

as if he had been tossed for a pancake. The fall gave me a good

splashing. It was as good a "back fall" as any wrestler could

desire, but the performer was in no way anxious to repeat it.

On wading round the vessel I found that the sea had carried away the

iron door of one of the "quarter ports," and portions of both chain

boxes. It had also whitewashed the funnel right up to the white band

with varied and picturesque tracery. As the dreary day was drawing

to a welcome close, and the leaden haze fell upon the turbid waters,

I overheard an observant Welshman saying in reference to the gale—"It was getting no better very fast. I should wonder if it would get

no better all night. Yes."

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

NEW YORK.

ALTHOUGH the

object of my visit to the United States was to treat of Americans

and American Society, it would have been a pity to bid good-bye to

my fellow voyagers without saying a word about them, or how the

voyage was finished. I may say for the latter that the rest of the

passage was in remarkable contrast with the commencement. After the

third gale the weather was delightfully fine; but it did not prepare

us for the temperature we had to encounter in New York. At the grey

dawn it was bitterly cold—we were then passing Sandy Hook, and being

afraid that I might miss seeing something of the land we had been

looking out for all the previous afternoon, I shelled out of my husk

ere the sun had lighted up Staten Island, the fine landscape lying

in dreamy shadow that gradually lighted up with a morning smile. And

now, while we are waiting to cross the bar let me say

something of the family of our temporary home.

The "Saloonists" represented ten nationalities beside "Owdham,"—English,

Irish, Scotch, Welsh, German, Russian, Norwegian, American, French,

and Canadian, and it might be a wonder to many how we got on

together. Well, we did get on together, and very well too. All

could speak English except the one Frenchman, and he picked up so

much of our language that he was able to say "good morning," and

"good night," which effort appeared to be a source of amusement to

him. The Russian was the most demonstrative fellow on board.

He talked with his hands and his arms; and when he was fast for a

word to sufficiently express his meaning, he somehow rolled it out

of his eyes in a way that was quite as good as if his tongue had

articulated it. The German would have it that he was Bismarck

in disguise, at which name the Frenchman shrugged his shoulders and

shook his head. The face was not unlike the portraits I have

seen of the German Prince, but the latter does not wear a beard, and

our Russian friend did.

He was a strange character was this subject of the Czar; and

we were a long time in making out what his profession was. But

we tumbled to it at last, and were not long after the discovery in

drawing him out in his true colours. He was a mesmerist or

something of the kind; and he gave us a séance which excited our

wonder and surprise. Getting one of the table guards, a board

about four feet long, and something like three inches broad, he

charged it with animal magnetism by rubbing his hands over the

surface; then set the board on end, although the ship was rolling at

the time, and made it stand erect. Then by a motion of his

chest, his arms being spread out, he caused the board to lean, like

the Tower of Pisa, for a moment, then it fell into his chest.

This we thought a marvellous performance, but the next was more

wonderful still. After re-charging the board with electricity,

he placed it flat upon the floor, then raised one end several

inches, in which position it remained five or six seconds. Had

I not witnessed that phenomenon and seen for myself that there could

have been no trick, or deception in it, I should have placed the

thing among the category of sea serpents, frogs in coal, and

pin-finding. How is it to be accounted for? Are there

more things in earth and heaven than are dreamt of in our

philosophy? Verily, there must be.

Dismissing the Russian I come to another character—the

Irishman. This fellow was "of infinite jest," the life and

soul of the smoking cabin. Full to the brim with anecdotes,

which he had a racy manner of giving. He had travelled over

the whole or greatest portions of the southern and western world;

and his "yarns" were of his travels. He could sing and dance

like a professional "comique," and I suspect, even yet, that he

belongs to that fraternity—either the music hall or the theatre.

His connection with the American gentleman, in whose company he

appears to have done most of his travelling, gave strength to my

suspicions; the other being a theatrical manager and part owner of a

theatre in New York.

The German was a Norwegian by adoption. He was a very

fine fellow, and spoke remarkably good English, having lived in

London several years, and married a London lady. He had a fund

of traditional stories of Norway, mostly of a superstitious

character. One for illustration of what the rest were like.

Said he, by way of preface, "we have been told of a certain

personage whom we all fear, but do not venerate; who is known by a

greater number of names than any other being: I mean the devil.

I find that in Norway we give him, for the sake of politeness, a

similar name to what I have heard you give him in your

Lancashire—you call him the 'Old Lad,' and he is known to us as the

'Old Gentleman.' We give him credit for having a much more

respectable appearance than you give him. We dispense with the

horns, the tail, and the cloven hoof and invest him with the

appearance of a real Norwegian gentleman, wearing broadcloth, and

bearing all other outward signs of a man to manners born. In

the dense Norwegian forests, of which there are many, he is held in

constant terror; and at nightfall, if the wayfarer happens to meet

anyone well dressed, especially if his figure be small, he is

believed to be the Old Gentleman, and a certain amount of respect is

paid to him to get into his good graces."

"One evening a boy, rather a plucky little fellow, was

rambling in the wood, when he picked up a nut that had fallen from

one of the trees, but he found it was no good; a grub had eaten the

kernel, and left a small hole in the shell. Just as the boy

had finished his examination of the nut and was about to throw it

away, he became aware of the presence of a little old gentleman

answering the description of the anti-divine. He became much

interested in this new acquaintance, eyed him over, scrutinized his

appearance and dress. At length, venturing to address the

little old gentleman, the boy said—

"Who are you?"

"I am the—" was the reply.

"Well," said the boy, neither frightened nor abashed, "if you

are the old gentleman you could get through this hole into this

nut."

Instantly there was nothing seen of the old gentleman but the

broad brim of a hat, and that at last disappeared through the hole

in the nut. To secure His Majesty in the prison-house the boy

plugged up the hole, and went on his way rejoicing that he had got

into his possession the source of all mischief. But the old

gentleman did not like his confinement, and begged to be set at

liberty. The boy engaged to let him go free on certain

conditions to the advantage of the jailor.

"But how must I get you out?" the boy asked to know. "I

can't get the plug out of the hole."

"Crack the nut," said the ――

The boy placed the nut between his jaws; but sound as were

his teeth, he could make no impression on the shell. He tried

hammering it with a stone; but, no, the nut would not yield.

"What shall I do?" said the boy. "I can't break the

shell; it is too hard."

"Take it to the blacksmith," said the ―― "he and I are old

friends, and shall be better acquainted by and bye."

The boy did so, and the smith examined the nut with a

peculiar interest.

"You say you can't crack it," he said.

"No," said the boy, "I've tried it with a stone, but the

shell is too hard."

"Well, I'll try what I can do," said the smith; and he placed

the nut upon the anvil. But in vain he hammered at it with his

small hammer; the shell would not give way. "The devil must be

in it," he exclaimed, after he had worked upon the nut until he

sweat; "but if he is I'll find him." So he took hold of his

sledge-hammer, and giving it a swing, let it fall upon the nut with

a crushing blow. The effect was startling. A figure shot

out of the broken shell—passed through the roof of the smithy,—and,

after assuming the length of the tallest pine, disappeared in a

blaze of light. "I thought," said he, when the effect of the

blow he had given had passed away, "The devil must be in it."

Other stories were told night after night; and I can assure

the reader that Lancashire was fairly represented. We had a

good time of it when we could sit without being pitched into each

other's stomachs. And in the saloon the piano was pretty well

punished.

For the greater part of the voyage our Oldham friend lay

coiled up like a hedge-hog, and refused to partake of any kind of

nourishment except a cup of tea, and a little biscuit. He

sighed for "Tommy Field;" and when he was told we were not yet

half-way across, he rolled himself up in his armourless coil, and

either slept or tried to sleep. But when he got over his

mal-de-mer, and had begun to find additional employment for his

teeth, he entertained the company on an evening with merry

discourses on a flute, of which he appeared to be a master. He

and I, and a Manchester Yorkshireman, were companions the

rest of the voyage. In the latter I found a friend after we

had landed, and that is something to say of a man who, up to that

time, had been comparatively a stranger to me. The rest of my

fellow voyagers were dispersed to the winds, and much as we had

suffered on our way, it was a matter of regret that we had to part.

But the landing,—and then I have done with matters exclusively

personal.

From the intense cold of the early morning the barometer

began to rise until it got well up the stairs; we could dispense

with our overcoats, and about noon we could have felt much more

comfortable without our body coats. My Yorkshire friend asked

me if it was always so hot, to which question I replied—

"This is scarcely average English summer heat; we shall have

it about thirty degrees hotter yet."

He seemed to collapse at this information, and to the

amusement of the crowd in Broadway, hoisted his umbrella. But

what was his astonishment on going to inspect his room at the

Metropolitan Hotel to see in one of the private rooms,—the

drawing-room of an itinerating family, a class of people who appear

to have no settled home—a large fire, almost stacked up into the

chimney. He was staggered.

"If this is winter," he said, "I shall never summer in

America; not good enough."

But the coldness of the night, in a measure, reconciled him

to the variableness of the climate, and he thought for the time that

he could stand it. When we had got our "baggage" safely

housed, and had secured our rooms, we went to see a little of "the

wickedest city in the world."

And now a word of advice given to me by an English gentleman

long resident in New York. It is well to give it here, as it

may be of use to some other "greenhorn" visiting the States.

"My young friend," said he (I am about ten years his senior),

"you don't appear to know much about New York; you don't appear to

have sufficient caution; like you have seen country people in

Manchester, you look about you too much. You don't see a New

Yorker doing that. He's always thinking about his business,

and fixes his eyes on the side walks, kinder thinking a patch of it

was there. A New Yorker aint like the Yanks. He don't

wear a goatee, nor hair on his collar. He just has his head

and chin as bare as a pumpkin, and brings out all his hair force on

his moustache. Now I guess that plug o' yourn aint the New

York fashion; too much Johnny about it. Git a squar' felt, and

boots to match,—toes as broad as a toomstone; shave off yer not-mach

of beard; git a false moustache, more like a broom the better; try

to look as though your experience of the world had soured your

existence; and you'll pass for a New Yorker."

"But I don't wish to pass for a New Yorker," I observed; at

which he smiled, and covered the floor with a streak of brown juice.

"That ain't bad of you, stranger," he replied, with another

squirt; "but you hitch yourself too much on to British pride.

I'm a Britisher myself, but I've learnt to sink the old country into

the Atlantic when I'm on the jaw. It aint well to buck agin

the stars and stripes, nor the saasy bird on the top of the flag

pole. Sw'ar by the hatchet of Washington, and yo'll get along;

but don't go too far. If you hope it may cut off the old

lion's tail, the'll git you. They've a kinder respect for the

British menagerie at the bottom; and they won't stand to tease the

animal. Buck agin him, and you strike lightning out of the

buttons of the genuine sons o' the west."

"Thank you for your caution," I said.

"Very good, stranger, but I ain't done yet. If you've

got a friend along with you don't go out alone. If you do the

chances are you'll get your pool scooped out. You haven't to

look for sharks; they'll follow you like a ship; and if they hail

you, and ask you how you're getting along, and how did you enjoy

your trip, they're fishing with their best bait. If you show

yourself flattered, and get to think you are somebody, you've got to

find out you are a darned fool, if you don't act up to my advice.

The sharks have watched you in and out of your hotel. They've

got your number when you've given up your key. Then they refer

to the book, and find your name to the number; that's the way they

git at you; and if you don't give them just the whole of Broadway

for their recreation ground, you're a gone foo; it's just a dollar

to a hickory nut you git cleared out."

"But I've a pair of eyes," I observed.

"What's the good o' them eyes if you don't know how to use

them. When a coon sees the open jaws of a snake, it's bound to

jump into its throat; can't help itself no more than being sucked

into a whirlpool when you get into the rapids. If you aint got

any business in New York, clear out of it smart, and you're safe;

git across the ferry; it don't matter where to, so long as there's a

splash of water betwixt you and this h—ll; for by ―― there aint no

brimstone hotter. But don't think the Americans have made New

York what it is. The sweepings and scourings of all countries

under the light of our glorious sun have been dumped here.

That is New York's misfortune. I kinder guess the old eagle

would give a feather out of its wing if the scamps could be got

together and shot, like old chaff beds, into the sea about a couple

of leagues east of Sandy Hook. There'd' be just about as much

rejoicing as there is on the fourth o' July: that would, stranger."

I took our friend's advice, and cleared out of New York as

soon as I could see my way; and took the Pavonia Ferry to Jersey

city; thence by rail to Paterson where I let go my anchor.

Here I found an agreeable change. From the iron edged bustle

of the metropolis I had dropped into a green and cozy nest, where

the shark could inspire no dread. Beneath its shady trees

hands held out to me; and their friendly grasp was reassuring.

Had my native Failsworth been the Failsworth I have known it to be,

with its roads overhung with trees, I might have imagined I was

there, only the green, shuttered white houses would have had to be

taken out of the picture, and brick ones put in their places.

Here I could listen to my native dialect in its almost pure state,

and stumble upon faces that I had missed without knowing to what "bourne"

they had gone. I had nightly receptions, of which I was

getting tired, and it was a relief to me when the Sabbath came.

|

Sabbath I thou art my Ararat of life,

Smiling above the deluge of my cares. |

I went to church in the morning, and was highly edified.

It is what they call the Reformed Church, much like our

congregational. The service was beautiful and the congregation

of a character that we do not find too many of in Manchester.

All were in their places before service commenced. There was

no staring round at late comers nor any comments on that "fright of

a bonnet." Fussiness would have been as much out of place as

spittoons, and would have brought down pity, or contempt upon anyone

indulging in it. The vocal music and organ accompaniments were

light and sweet, as if the difference betwixt the breathing of soft

harmonies and the bellowing of spasmodic thunder was properly

recognised. The congregation joined in the first, and closing

hymns; the rest were sung by the choir only. When I heard the

strains of the "Old Hundredth," they touched a chord that brought

the space of three thousand miles to within a span; and I heard in

it the echo of

A voice that has long been hushed,

the sweetest music my ear could have listened to. The ruffled

spirit which danger and turmoil had harassed, I felt to calm down,

and at last peace fell upon my soul.

The morning was gloriously bright, such as we see none in

England and as the sun sent its streams of gold through windows

which were not constructed to keep out the light, the trees outside,

with their full leaf ornaments, reflected scintillations of a still

brighter effulgence. I felt that we had something to learn

from our cousins, if it was only the building of churches.

What a contrast, I thought, was this place to the gloom, and the

dingy surroundings of St. John's, Miles Platting.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

AMERICAN PROGRESS.

FOUR years have

wrought a change in American tastes, and made an impression on its

institutions. These changes may have not been perceptible to

frequent visitors, but they are not the less striking to those whose

visits, like angels', are "few and far between." When General

Grant "struck" Manchester (England) and saw the magnificent pavement

in front of the Town Hall, he had not an eye for anything besides.

The splendid monument of the late Prince Consort—

|

A piece of marble was to him,

And nothing more; |

but the square sets upon which he stood, so neatly fitted to each

other, and which made such an even surface, were more to him than

the chiselled stone which seemed to breathe the breath of noble

life. No doubt his mind was running over things beyond the

"silver streak:" New York, the centre of everything American, with

its grand Broadway, the pride and scandal of its civilization: the

well-dressed lady with the ugly boots; for to such I compared it on

my visit four years ago.

The pavement of this noble street is one of the changes I

have noticed. Square "sets" have taken the place of

the round cobbles of something like half-a-hundred weight; and no

man can now lock his foot in crossing, or need be alarmed about the

safety of his ankle. Can this change be attributed to the visit of

Gen. Grant to England? In the buildings on each hand there has

been a transformation as though the Harlequin's wand had exercised

its magic power in the pantomime of real life. The "jerry" of

a new country is being swept away and piles of elegant buildings are

rising on their foundations. Another eyesore is being removed.

The improved class of warehouses and offices have banished the

associations of the older tenements. We no longer encounter an

array of plaster Indians, "hooking-in" at tobacconists' doors.

No longer is Punch looking out for his countrymen, to put

them on their guard against people who make a living out of sucking

the blood of strangers. I claim the hunchbacked humorist to be

the English nationality notwithstanding whatever may be said to the

contrary. "Depots" on railroads (America has no railways) are

disappearing, and the English term "station" is being substituted.

America is evidently following in the footsteps of the mother

country.

But more striking still is the change that is being felt in

the tone of American politics and politicians. By the latter I

do not mean the people who "run" governments; but outsiders, whose

opinions, as well as their votes, are a power in the