|

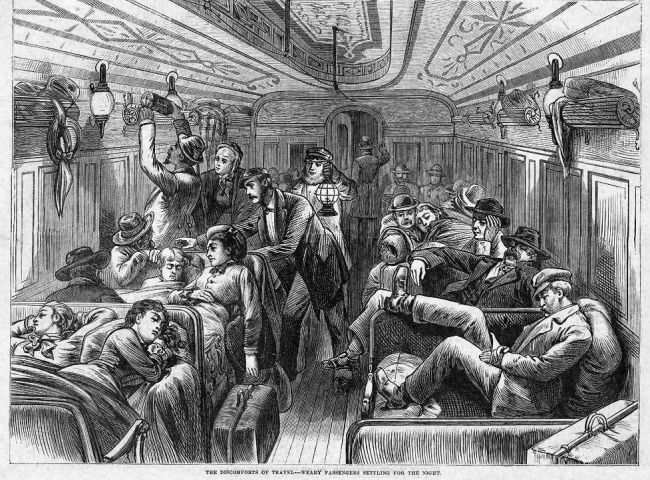

AB-O'TH'-YATE IN YANKEELAND.

FIRST TRIP, 1880.

CHAPTER I.

THE VOYAGE OUT.

THE idea of

taking my old friend "Ab" to grass among "fresh fields, and pastures

new," originated with me some years ago; but allowing circumstances

to get the better of my determination, the project had to be

shelved, where it had remained only to be dusted, and redusted, ever

since. The time came at last, when the trip could be put off

no longer; and on the 22nd of April Ab bade farewell to Walmsley

Fowt, accompanied as far as Liverpool by his "old rib," and "troops

of friends," to wish him God speed on his voyage.

It was not an everyday matter for our friend to get away from

his home. There were associations that were dear to him.

There was his garden, already lighted up with a lustre of flowers;

his beehive, that while he was away would be musical with industrial

life; his loom, that would be silent until it was covered with dust

and cobwebs; the old bobbinwheel, now no longer doing duty as a

"feel-loss-o'-speed;" the gate which for hundreds of hours he had

sat upon absorbed in dreams of his peculiar philosophy—these would

be among the first things missed. Then there was the "Old

Bell!" What could he do without his accustomed nightcap at

that glorious "rallying point," and his frequent skits with "Fause

Juddie?" What was there in the land he was going to that would

compensate for the loss of all these? There was nothing that

the future yet promised; and, lacking this, his spirits succumbed to

melancholy.

But there was one thought that would cause him to smile when

the dumps were deepest. If he could fleece a Yankee, or scalp

an Indian, or shoot a buffalo, or tell the biggest lie, these

extraordinary feats might afford a little satisfaction to one who is

not in the habit of expecting too much. But who would "catch a

weazle," or "shoot a thief?"—and who would be his companions in the

practical joking, which had hitherto been the salt of his life?

More than all, who would comfort his old "stockinmender" in his

absence? That thought caused the tear to flow many a time when

no one witnessed it. The old girl had her peculiarities, no

doubt; and a little of that which all women possess, temper.

Neither of these would trouble him; but when in her loneliness she

would cry out "Wheere's my Ab? Wheere's that foo, but one o'th

best o' foos?" and there is nobody there to reply, she might be

tempted to follow, or in a desperate moment try the navigation of

the mop-hole. "Th' childer had groon up," he said, "an' like

young sparrows when they'd forsaked th' neest, cared nowt for it;"

so he felt no regret about leaving them.

There was, however, one drop of comfort in his mixture of

many troubles; the friends he was leaving behind would do what they

could to fill up his place. Jack o' Flunter's had promised to

look after his hens, and Siah at owd Bob's, who had recently killed

a pig, would see that the old rib did not go short of bacon.

Jim Thuston promised that the milk-score should not be limited, and

Billy Softly would overtop the kind offices of the rest at a very

cheap rate—he would read for her a chapter every Sunday out of the

old Book; not forgetting that about Jonah and the whale. Fause

Juddie declared his readiness to do anything he could for the

family, if the Americans would "keep th' foo' o' their side o' th'

wayter, or drop him about th' hauve road across." All the

neighbours appeared to be desirous of doing something for Ab; but

how far these desires would find expression in deeds was quite

another thing, and might never be realised. However, it was a

source of consolation to our old friend when he was most in need of

it, and it helped the poor fellow to loosen the ties that bound him

to his native earth without lacerating the flesh that adhered to

them.

When Jim Thuston's donkey-cart drew up to the door, to take

down the luggage to the railway station, I thought Ab looked like a

man who, standing above a crowd, was listening to the ministrations

of a representative of divine mercy, whilst another individual was

coolly toying with the noose end of a rope, that was not to be

employed in fishing something out of a well. When the luggage

had been hoisted up, and Ab was asked if that was all he wanted, the

poor fellow fairly broke down; and, saying that he did not know what

he had done amiss that he should be sent three thousand miles away

from home, he took hold of several proffered hands, and shook them

until he had gone three or four times round the group, and would

have been shaking now if time had permitted him. That over, he

threw a few crumbs to the poultry that had assembled to witness his

departure, knowing that at the same time they were losing a friend,

and, seeing that they were too full of emotion to indulge in a

single "peck," he tore himself away, and never spoke, nor looked up,

till he reached the old Bell, which he seemed to think he was

visiting for the last time.

"Th' last pint," he said, throwing himself down on a chair in

the kitchen. "I may never have another. Th' next I drink

may be saut wayter. But there's one comfort, if a shark gets

howd on me, he'll have a toughish job for t' get through his meal,

speshly when he comes to my ears. A pair of shoon would be a

foo' to 'em, if it wurno for th' nails. But it's like out o'

place jokin at summat ut's wurr than a buryin; so, come,—farewell!"

What a crowd followed us to, or met us at the station and

what a crowd accompanied us to Liverpool! The Cheshire Lines

Company kindly placed a couple of saloon carriages at our service,

and both were well filled. Our friends grew quite hilarious as

soon as the train left the station, where handkerchiefs were being

waved by those left behind. It might have been a welcome home,

instead of a farewell, the merriment went so "fast and furious."

Ab was somewhat disconcerted at this, and observed to me, dolefully—

"Yer yo, how fain they are becose I'm gooin away! Well,

I reckon sich is life."

I had to ply our old friend with a few drops of his favourite

"cordial" to keep his spirits floating; and when medicine time came,

his mouth was always ready.

Ab expressed himself as being alive to the fact that—"if a

mon wants to be looked after he should sit in his dumps. If he

felt brisk, he'd get nowt." A little more of his left-handed

philosophy, I thought. After feasting right royally at the

"Queen's," in Liverpool, we made for the landing-stage, where the

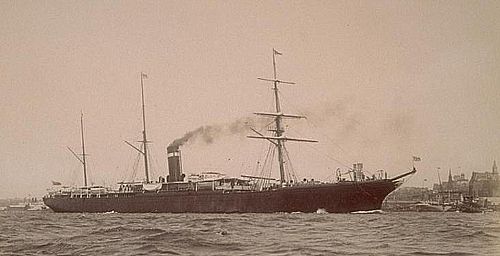

first object that caught our attention was the "City of Berlin," the

vessel that was to convey us across the Atlantic. Our future

home had in its appearance such a promise of safety that the fears

which had from time to time haunted my sleep subsided at once.

The sight of the noble ship had the same effect upon Ab; and as he

gazed at its formidable outline, he ventured on the opinion that it

was "safer than loud."

|

|

|

Inman Line's City of Berlin.

Launched 1874-broken up 1921. Holder of

the Blue Riband, 1875.

Source: Wikipedia |

There the many-eyed monster lay that was destined to

"—walk the ocean like a thing of life;"

the captain's flag waving from the yard; and the crew moving about

the deck as if "clearing" for action with some unseen enemy.

The long trail of smoke that was being vomited from the coalpit-wide

funnel told us that everything that was being done now was in

earnest, and we must at once prepare ourselves for the worst.

The tender was crowded with people who had come, perhaps, to

say the last words they might ever speak to relatives or friends

departing, and whom the huge monster, snorting, and seeming to paw

the sea, was eager to get in its power. The size of this

monster grew upon us as we approached its anchorage, and the huge

walls of timber presented to us the appearance of an impregnable

fortress.

"I dar goo anywheere wi' that," said our friend Ab, as he

looked up at the hull and yards, and the funnel that would have done

for the casing of a coal shaft. "There's not a bit moore

danger bein theere than bein i' owd Thuston's barn in a March wynt.

I should no' care a bit if th' owd rib wur gooin across wi' me, an'

wouldno' be poorly. I mun say, an' I'll tell th' truth for

once, if I commit a sin by it, ut I dunno' like leeavin her beheend

me, hoo looks so weel to-day. But then, yo' seen, if hoo're

usin a tub at th' same time as I wur, an' I couldno' look after her,

there'd be sich a dooment, as far as a tongue an' a pair o' lungs

wur concarned, as never wur known i' that cote. I shouldno'

wonder if she turns eaut like Ruth at last, an' says where I goo

hoo'll goo. Women are queer."

By the time our friend had finished his remarks, which were

highly characteristic of the man, we were ordered up the gangway

communicating with the tender and the ship. No sooner had Ab

set his foot on the deck of the noble vessel than he exclaimed—

"I'm upo' th' scaffold now; th' next thing'll be swingin off.

It'll oather be life or eternity then."

Through the kindness of Mr. Wilson, the Manchester agent for

the Inman Company's steamers, our friends, to the number of forty,

were shown over the interior of the vessel; and it was edifying to

hear the observations that were made by them in relation to the

accommodation for passengers, the provision made for their comforts,

and the luxurious character of the surroundings. But the time

was too short to see everything as we have seen it since.

Those on board who were not prepared for a voyage of three thousand

miles were warned to depart. But one, a lady of good

dimensions, stuck to the last; and I had the unusual treat of

witnessing the introduction to a scene that had its ludicrous, as

well as its impressive side. The philosopher of Walmsley Fowt

had his handkerchief in his right hand, and about twelve stone of a

"dear owd crayther" on his left arm. The working of his

features had the elasticity, and the variety of expression which a

good manipulator can get out of the face of an India rubber doll.

But here I must draw the curtain.

|

"Farewell, a word that must be, and hath been,

A sound which makes us linger, yet farewell!" |

There is a splashing in the river; and we have a

consciousness of something receding from us. It may be a sad

face; a group of many loving hearts; bright scenes of many, many

years ago, remembered at that moment as if they had occurred but

yesterday; and all might be leaving us for us. White

handkerchiefs are waving; there is a throbbing motion beneath our

feet. Is it the Pulsation of the many hearts on board,

responding to those that are nearing shore? Or is it the

engine? Perhaps both.

"Then rose from sea to sky the wild farewell."

And all was over.

"Come, Ab, let's liquor," said "Sammy o' Moseses," one of our

party, and about the jolliest.

"Stop a bit," said Ab, with his breast firmly jammed against

the bulwarks, and his eyes fixed upon something in the direction of

Liverpool, "I con see her yet."

"What her?" said Sammy.

"Wheay, there is nobbut one her i' this wo'ld,"

replied Ab, "an' hoo's just wringin her napkin now. Jack o'

Flunter's, an' Siah at owd Bob's, an' Jim Thuston, are sayin summat

to her. An' now th' bottle! Thou'll do, Sarah, owd

wench, in a bit. God bless thee!"

When we had got Ab's waistcoat unglued from the bulwarks we

took him into the smoke cabin, and in about ten minutes after,

"Walter," a very amiable and attentive steward, had ministered to

our wants, my lord Abram was crooning over a love song, which I must

confess I never heard before.

|

"'We never miss the water till the well's run dry,' 'tis

said;

We never know what hunger is until we're short of bread;

Nor know we woman's love, nor yet the fulness of her heart,

Till the moment comes when fate decrees we must forever part." |

"There's about sixteen more verses," he said, when he had

finished the first, "but I feel as if I could not get through 'em o.

Yon poor wench has howd on me yet with a grip like a pair o'

pincers, an' hoo's loth to leeave loce. Beside, I'm havin me

last glent of owd England for a while. It's settin now like a

love-star. Farewell. Thou's a good deeal o' fauts; but

I'm th' same wi' thee as a woman is wi' a drunken husbant, I like

thee through 'em o, nobody mun say nowt again thee, nobbut me.

If they dun they may look out for timber."

Some people, I found, are not the least affected by a change

which I consider a great one. To them a voyage of three

thousand miles is not worth a passing thought. No sooner was

the luggage, or as the Yankees call it, "baggage," disposed of, than

out come sundry packs of cards, and in a few minutes they were

"Nap"-ing it all round. Sentiment was either not with them, or

was hushed for the time, as they were eager on sport, or merry over

winning. Our friend Ab was in hopes that some of the players

had return tickets, as he "calkilated" that by the speed in which

they were emptying their pockets their "bottom dollar" would soon

make its appearance. I was told in New York that one of our

fellow-voyagers had won about a month's sea-fare. That would

have been a matter for congratulation if nobody had lost the same

amount. It was Nap, Nap, Nap, every day but two, and one of

them was Sunday. Of the other day, anon; it will not be

readily forgotten.

We had very steady sailing across the Irish channel, and we

took it to augur a pleasant voyage throughout.

"It's far safer than bein upo' lond," Ab remarked, in a

running comment on seafaring in general. "There's no

earthquakes here; nor no tall chimdies rockin. Yo' conno'

tumble down a coalpit; nor get hanged in a clooas-line of a dark

neet. There's no danger o' gettin run o'er wi' a butcher's

cart, or a nob's carriage. Then yo' conno' get into a doytch

when th' whisky has th' upper hond. An' yo' con find yo'r

clooas i' th' mornin without knowin they're on a cheear-back afore

th' fire, dryin. Th' sae has its advantages."

With the fall of evening came the shores of Ireland, lovely

under the westering sun; and peaceful as the sleep of childhood.

When its outlines were hidden in the dark and still darker grey of

night, we began to feel that we were not of earth, but children in

the lap of a new mother, the mighty deep. And more than that,

we knew that our adopted parent would have much of her own way with

us; and would take care that we were at home before "ungodly hours"

broke the morn's repose.

"Ay, hoo'll do that," said Ab, about the "tab-end" of a

reverie. "Hoo'll no' stond shoutin at th' bottom o'th' fowt,

an' threatenin for t' throw someb'dy i'th mop-hole if they dunno'

come i'th' house. Hoo'll gether 'em into th' nook beaut any

trouble; an' if they trien t' get out o'th' road of a good hoidin,

they'n nobbut so far to run afore they'n find a fence they dar' no'

get o'er. If our Sal had me so safe every neet, wouldno' th'

owd ticket look breet? I can see her cockin her spectakles at

me, as hoo's drawin a stockin on her arm, an' sayin 'Abram, I ha'

thee now.'"

A STORM.

It was a novelty to me that I cannot now realise the effect

of, climbing into my berth, as if I was putting myself away on a

shelf, ticketed as clothes in pawn. It is a marvel that I

slept, as I had looked forward to a night on the sea as the greatest

trial of the voyage. But I slept; and when the morn broke I

took a peep through my eyeglass of window, and was gladdened to see

that the sun was dancing on the waves, inviting us to rejoice with

it. On reaching the deck I found our friend Ab taking in a

view of Paddy's land, which lay in strips of grey and purple to the

west. This morning's sail was a delightful one, hugging, as we

did, the ever changing shore, till we reached Queenstown, where we

had to take in the Irish mails. Here we were detained seven

hours, the victims of beggar solicitude, which is intolerable.

A blessing for a penny, and a good cursing if we gave nothing.

The land must be lost that suffers this.

"A nice bit o' lond," said Ab, as we were leaving shore; and

he showed me a bunch of primroses that he had gathered. "One

would ha' thowt it would ha' made nicer folk. I'd an owd woman

at me just as I're getting to th' end o'th' plank; an' I thowt

hoo're gooin to strip every rag I had off my carcas'. Th'

blessins an' blarney hoo gan me made me feel that I mit waste a

penny on it, an' be no wurr off. But when I felt i' my pocket

I'd nobbut a haupenny; an' when I gan her that I thowt hood ha'

flung it i' my face; but hoo didno'. Hoo gan me a good cussin

i'stead."

What a pity, I thought,—a people so neglected.

We are again on board the "City of Berlin;" the steam is up;

and the first throb from the breast of the broad Atlantic signals

our departure from the last stretch of our Northern Isles. The

next land we see will not be our own; but as Ab tritely remarked,—

"It's nobbut my uncle Sam's fowt; an' I dar'-say he'll be

fain t' see us. I should think that lad of his, Jonathan, is

groon up by this time. He're aulus a tall un for his

age. If he'll nobbut be summat like that blunderin owd foo of

a Jack Bull, he may do; but he winno' have as mony centuries o'

wickedness an' misrule to onswer for; no' yet, at anyrate.

Yond's th' last bit o' loud, like a streak o' dun cloud. It's

farewell after this."

It was farewell. The land melted into the memory like a

glory of the past; and the "watery waste" was now to be our home.

After all, it was a relief, like the drawing of a tooth, when it was

over.

And now for a new, and terrible experience in my brief

seafaring life. I had had two days of violent retching and

when the spasms were on me I had no care whatever for anything.

But those two days over and I was a new made man; and the sea, and

the vessel, were as playthings to me. I entered into the

social life of the company; took an interest in their pastimes; and

felt that if things grew no worse, the remainder of our voyage to

New York would be a most delightful one. But I found I had

calculated upon chances that were far beyond my ken.

It was on the day before we were due at New York that the

company of cabin passengers arranged to hold a concert in the

saloon, previous to their saying "good-bye" to each other. The

programme was written out; rehearsals were "fixed;" the piano had

been tinkling all morning; when about noon suspicious-looking clouds

were observed to windward; and anxious glances were given in their

direction by the officers of the vessel. The wind, from a

moderate freshness, rapidly increased to a gale. The sea

swelled into heaps of angry water, that chafed, and bellowed in a

frightful chorus. A storm was inevitable, and preparations

were being made to meet it. When the gale was near its worst I

dodged out of the saloon, where I had been lying on a lounge, and

was afraid of being pitched among the crockery that was being set

for dinner,—and struggled to get on deck. I was banged about

fearfully; and when I reached the head of the stair, I felt myself

quite unprepared for the sight that was presented to me. But

as Ab has given a full description of the scene in a letter to his

wife, and which will appear in our next chapter, I will pass on to

an interesting incident.

I found Ab sitting at the door of the smoke room, apparently

in deep meditation, if not in earnest prayer. There was no

playing at "Nap," anxious eyes were strained over the wide field of

watery strife; and voices were only heard in "bated breath."

"Art' i' thy dumps, Ab?" I whispered, rousing up my old

friend into a consciousness of my presence.

"I am," he replied, with a sigh; "up to th' knees in 'em.

I'm tryin to mak up my club books, so ut they con goo afore th'

Great Committee witheaut bein a farthin wrong; for I can see ut we

shanno' be lung upo' these booards. Yer yo', heaw th' ship

keeps gettin hommered wi' th' waves! It's a wonder we are no'

at th' bottom this minit. But th' owd crayther stonds it like

a stone wall. I've been wonderin whoa I've done owt wrong to i'

my life; but conno' reckon upo' nowt nobbut one thing—takkin a

hontful o' Joe-at-th'-Knowe's marbles when he'd won o mine off me;

an' he're th' least lad o'th' two. If there's forgiveness for

that I con be yezzy. Our Sal 'll fret awhile, I know; but hoo

may clog again, an' forget me. I dunno' know whether it's a

sin or not for t' be a foe. If it is I'm done for. But I

never hurt nob'dy, unless it wur wi' gettin th' owd rib's temper up

a bit above th' boilin mark. But hoo could aulus cool hersel

wi' a fly at my yure; so that owt no' stored i' my road. I've

prayed mony an heaur i' my time, but without makkin a noise, as some

folk dun; an I've happen bin yerd by th' Great Judge of o' as weel

as th' biggest shouter ut ever rent a throat. Will that do for

me?"

I told him I thought it would; but, as dinner was ready, we

had better defer these considerations until it was over.

"Let's go down, then," said Ab, getting up from his seat, and

giving me a butt in the stomach. "We mit as weel go down wi' a

full senglet; we shall sink sooner."

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

AB ON STORMS, AND OTHER THINGS.—HIS FIRST

LETTER TO HIS WIFE.

Metrolopitan Hotel, Broadway, New York,

May 3rd, 1880.

OWD

BLOSSOM!—I'm wick!

If that's as mich as thou cares for thou's satisfaction. But I

know thou cares for moore than that; an' ut thou'rt fairly itchin

for t' know how I've bin on th' road to here. I thowt I'd let

thee know ut I're livin th' fust thing of owt; so ut thou could lay

thy spectakles down, an' give a good soik of relief. Now,

then, for summat moore.

When I lost seet o' thee at Liverpool; an' after I'd wrung my

rag a time or two, I began a-wonderin' what I'd laft thee beheend

for. It's true thou'd towt me th' use of a needle an' threed,

so ut I could linder a button to a shirt as weel as some women con;

but I soon fund out that wurno' o ut a mon wants a wife for.

It had never crossed my mind before ut a woman wur a men's best

companion,—speshly when he's a bit poorly, as I've bin, goodness

knows. I should mak a poor widow, tho' I con bake, an' wesh,

an' mend stockins, an' do other bits o' odd jobs ut seem nowt to

women; but summat when a mon tries his hond at 'em.

Losing thee so suddenly, I felt as if I'd lost my reet arm. I

moped about th' deck o' th' ship till Sammy o' Moses said I favvort

a boilt owl; tho' what that is I dunno' know, as I never seed one.

What I should ha' done if it hadno' bin for th' brandy that good

woman ut keeps th' Tower Hotel gan me, I fear to think. Co,

an' thank her for it th' next time thou goes to Manchester; an' tell

her if it hadno' bin for thoose sperrits I should ha' lost my

own.

By th' second day I coome round a bit, an' I could talk to

folk; an' th' sae hadno' bothered me yet, becose it nobbut skipped a

bit, as if it wur having a quiet frolic. But I fund it could

be a lion, as weel as a lamb, before it had done wi' us.

However, I mun tell thee about that when it comes in. Sammy

an' me had to sleep i' th' same cote, but that thou knows oready.

I're feart o' gooin' t' bed th' fust time, as I didno' know what mit

happen while I're asleep. But musterin a bit o' courage, I

scrambled on th' top shelf at last, barkin one shin, an tuppin my

yead again th' ceilin. That done, I stretched mysel down, pood

the clooas o'er me, an' thowt about thee. But I yerd someb'dy

singin, an' I said to mysel, if anybody's pluck to sing, surely

there's no 'casion for any dumps i' me. Then I toped o'er, an'

dreamt about seein a mermaid—just like thee hoo wur as far as her

stays, if hoo'd had any; but hoo wore th' skin of a fish for

unwhisperables, an hoo'd booath legs i' one sleeve. But even i'

that dress hoo wurno' mich unlike some young women, ut are so

tightened up they con hardly walk. Hoo said hoo wur thee,

an' had bin transmogrified into what hoo wur for wishin I'd get

drownt. I towd her ut if hoo hadno' bin guilty o' that dampt

lie I'd ha' helped her into th' ship; but tellin me sich a thumper

about thee hoo mit dive, an' be danged to her! So hoo dove—wi'

her thumb to her nose an' her fingers spread out like a hen's tail.

Th' plunge this merwoman gan when hoo went down wakkent me, an' I

could yer Sammy o' Moses's wur droivin pigs finely. An' then

sich a thumpin noise goin on ut I wondered what wur up, when they a

hudther, ut shook the vessel as if there'd bin a saequake.

"How art' gettin on, Ab?" Sammy shouted fro' th' bottom bunk.

"Gettin th' wost o'er," I said.

"I deaut it," Sammy said. "We'n had no weather yet.

Wait till th' ship lies o' one side like a drunken jackass, or a

stoo wi' nobbut one leg, an' thou flies out o' that bunk same as if

someb'dy had lifted thee out o'th' owd Bell wi' their foot.

That's th' time for tryin' what a chap's made on." That caused

my fingers to tingle.

"What's that noise ut's bin gooin on o neet?" I axt him, for

I'd bin bothert with it.

"What's it like?" Sammy said.

"Well, it put me i' mind o' James o' Joe's loom, when he used

to wayve o' neet," I towd him.

"Oh, it wur th' engine," Sammy said; an' ever after that it

went by th' name o' "James o' Joe's loom."

Sammy towd true i' one thing. He said we'd had no

weather yet. But I booath seed an' felt some in about two days

after. Sunday wur a quiet day. Th' sae seemed as if it

had had its Setturday's neet's sleep, an' furgetten it wur daytime;

for to my thinkin I du'st ha' ventured on it i' our owd kayther

(cradle), if th' rockers had bin pood off. We'd church sarvice

i'th' mornin',—everythin obbut th' sarmon, an th' "I believes."

Th' captain wur th' pa'son; but o' somehow he looked at th' wrong

job; un' so did his clerk. Their faces wur too mich like rough

weather for churn-milk-and-traycle wark. I're as devout as

anybody, for I felt as if I're i' Someb'dy's honds beside my own.

That wur about th' only quiet day we had. Th' wynt

began of a spree, an'—so did I th' day after; but we'rn different.

Th' sae wur "merry," some said. Others said it wur "lumpy;"

an' I began a-feelin a bit of a sinkin my inside. I're watchin

'em play "Nap" i'th smookin shop, when o of a sudden I had to run as

if someb'dy had shouted on me, for t' see 'em tak their last.

"Wheere art' off to, Ab?" Sammy o' Moses' shouted, when I

twitched out o'th' dur, as if I're slippin thee.

I dustno spake, for—oh, dear me!—wheere's they a quiet

corner? I fund one at th' starn end; an' I stopped, theere,

starin at th' rudder-froth, an' now an' then givin a bit of a crow,

like a choilt does when it's th' chinkcowgh. I should say I're

a stone leeter afore I laft that shop. My senglet flapped

about me as if I'd bin a lad, an my grondfeyther's. I thowt

I'd done then; but I hadno', I'd another left-handed prayer-meetin

th' day after; an' when I'd cleared out th' sins o' my in'ard flesh,

I felt like a new made mon,—fairly a lad again. I knocked

about the deck like a young swell showin his new clooas at a

pastime, little thinkin what wur i' pickle for us. An' when I

tell thee how weel off we wur to what wur th' lot o' some folk ut

had Christian feelins like oursels, thou'll wonder how it is ut they

con see, or feel, or taste, anythin to live for. I dunno'

think, Sarah, ut th' good things o' this wo'ld are fairly divided;

but th' richest areno' th' happiest, for o that.

I're clompin up th' stairs to th' top deck one mornin, just

for t' have a bit of a breeathin, when I yerd someb'dy shout out—

"Ab, how's th' owd rib?"

"I'd as soon ha' expected yerrin an angel's trumpet as that

i'th' middle o'th' sae, about fifteen hundert miles fro' whoam.

I looked down among the steerage passengers, wheere I thowt th'

sound come fro', when among the crowd, ut were packed like folk at a

playhouse dur at a pantymime time, an' I seed three or four faces ut

looked like gradely uns.

"Wheere dun yo' come fro?" I axt 'em.

"Owdham an' Mossley," they said.

"Wheere are yo' goin to?"

"To Fall River."

"Han yo' shops to go to?"

"Nawe, but we'n friends theere."

An' yo'n want 'em, too, I thowt—God help yo! "Anybody

wi' yo?"

"Ay th' owd hens, an' th' chickens."

Then I noticed some women an' childer sittin on th' bare

deck, wi their backs reared again th' cookhouse. They're

jollier than thou could ha' bin under the same circumstances.

For my sake they oppent some music books an began a singin—one

o'Sankey's hymns, it wur—"Pull for the Shore." That melted me

fairly to my heart's deepest tallow. Th' little uns joined in

wi' their sweet trebles, an' their feythers knelt down outside th'

ring, dooin th' bass. When they'd done they axt me if I'd have

a drop o' "jacky" wi' em. Thou knows whether I'd refuse it, or

not—under th' circumstances. When they'd done I

promised 'em i'th' name o' my companions ut they shouldno' go short.

"Eh, we'n moore than we shall want," they said; an' that wur

a bit o' satisfaction to me. Oh, rare independence, my

Lancashire lads!

"Tell Sam Smithies," one on 'em said, "th' next time yo go'ne

to Mossley, ut yo'n seen Buckley."

I promised him I would; an' I will. We did a good deeal

o' neighbourin after that, when th' weather wur reet. But they

must have had a hard time on't when we'rn crossin th' "Devil's

Hole," or th' "Roarin Forty." I had, as thou'll see.

Lorgus me, Sal, I thowt I must never ha' seen thee no moore.

Ther a storm coome on as sudden as if it had bin ordered to

th' minit, an to be browt in wot. I clenched my nails i' my

honds, an' set my teeth, ready for what mit come. I wished I'd

bin sae-sick then. If I had I shouldno' ha' bin feart o' nowt,—not

even him ut theau used to freeten our childer with when

they're auvish. Sammy o' Moses's wur on his back wi' a sore

throat, an' knew little o'th' storm. But I couldno' ha' slept

if I'd had two cupful o' owd Jacky wife's cordial. Th' sae wur

like a thousant cloofs rowlin o'er one another, wi' a million o'

hedges on th' top, an' th' sides, covered wi' white blossoms, or wi'

haliday shirts. Sometimes we'rn at th' bottom; sometimes

dashin through th' middle; sometimes at th' top, as if we'rn flyin

o'er; an then plungin down soss, like throwin a dog i'th' middle o'

owd Thuston's pit. When th' wo'st wur at the wo'st, an' I'd

gan mysel up, I're axt down to my dinner. Rayther a strange

feelin coome o'er me at th' thowts o' feedin, happen th' last hour

o' one's life.

A thowt struck me. As I didno' want to swim so long,

when ther no chance o' bein saved, I'd an idea that a pound or two

under my waistcoat would do i'stead of a stone round my neck.

So I floundered down to th' Sal-oon, an' housed my last meal, as I

thowt. But before I'd finished I're slat o'er wi' soup, an' my

e'en wur plaistered up wi' mutton fat, becose th' table kept wautin,

an' me wi' it, till I're sometimes o' my nose, an' sometimes o' my

back. My "boss" axed me if I could do wi' a drop o'

silver-necked pop. As it wur th' last do we should ever

have t'gether, unless we londed inside o'th' same shark, I said I

didno' mind. It would be like gooin to one's fate filled wi'

glory an' fireworks. We had it, an' when th' last drop had

fizzed I felt quite ready for my share o' saut wayter. But

while we're primin oursels for a new sort o' wark th' rockin an'

bumpin geet slacker, an' th' lamps didno' swing about as mich as

they had done. Th' whistlin music i'th' riggin geet deawn to a

moan, an' a chap ut I'd seen lookin very white abeaut th' gills

coome down wi' th' news ut th' storm wur deein away, an' we'd a new

leease o' life made out to us. That wur rayther like a

disappointment after we'd made up our minds for th' grand change;

but I took things as weel as I could put up wi' 'em, an' went

upstairs. Ther a bit moore life stirrin, I fund then, than

there wur when I went down. It wur like th' difference in a

gambler's face between winnin an' losin.

We should ha' had a bit of a singin do that neet; but o th'

singers wur i' their bunks, makkin a different sort of a noise to

singin. So it had to be put off till th' neet after. We

sung upstairs, too, rejoicin, like, ut our clooas wur dry. An'

th' cards coome out, as if nowt had happened. How soon we

forgetten danger when it's passed! It's like a lad when he's

just missed a good hoidin, he goes straight int' mischief th' next

minit.

We'd a fine day o' Setturday; an' everybody began a-brushin

up for londin, just as if we'd nobbut an' hour, or so, for t' be on

board. We'rn towd we shouldno' lond afore Sunday afternoon.

One mon said he didno' care if he never did lond. He'd bin

nine days, an' spent nowt, tho' he'd lived like a feightin-cock o th'

time. As soon as he londed he knew his hont would ha' to be

divin into his pocket at every turn.

Just as we'rn pooin up for t' lond o' Sunday afternoon I seed

two faces on th' londin-stage ut wurno' quite strange to me.

They belonged to two owd marble companions,—Jack o' Jimmy's, an'

Will o' Jimmy's. They'd yerd I're comin; so coome for t' leead

me up. They'd laft mony a score beheend 'em waitin for t' gie

me welcome. How I went on I mun tell thee i' my next letter.

I think I've towd thee enoogh at once. I'm drinkin nowt

stronger than "lager-bier;" an' nob'dy con mak a foo o' theirsels

off that; so thou may feel yezzy abeaut me. Ta-ta! fro' thy

lovin yorney,

AB.

Taking up the thread of my narrative where our friend Ab has

left off, it will be my duty to chronicle the lesser events of our

voyage. Our concert on the Saturday evening was quite a

success, and the saloon presented an unusually gay appearance.

A temporary proscenium, formed by the intermingling of the British

and American flags, was erected in front of the piano; and as the

vessel rode very steadily, there was no difficulty in the performers

keeping their legs. It would be unfair to criticise that which

could not be heard, the thumping of the engine being the principal

part of the performance—except the collection. That I might

contribute my share towards the proceedings I had to write a "copy

of verses," which were read, by way of prologue, by a Dr. McManus,

of Texas. They were as follows:—

|

When we sailed from the Mersey, as strangers, on board

The "City of Berlin," a ship without brother;

Long ere the loved shores of old England were lost

We spoke to each other.

Though the husband would feel for the wife left behind

And the youth new to life might then think of his mother,

We pledged "new acquaintance" in tears not yet dried,

And we talked with each other.

No sooner had Erin's green shores left our view,

When the struggle was hardest our feelings to smother;

Then we were all "Johnny Butterworth's lads" o'er again,

And we grew to each other.

The first morn that broke on the Atlantic's broad breast

Each woman a sister had found, and a brother;

And a newly-made family, wedded to home,

Now clung to each other.

In calm or in tempest, in sunshine or haze,

When a sister in pain lay we did all to soothe her;

And a face that was missed was as one passed away,

And we mourned with each other.

Though the memory of old friends may lie next the

heart,

When we find among strangers a new friend and brother,

'Twere a glorious feeling that, go where we may,

We shall think of each other.

Then toast we the captain, the doctor, and crew,—

With the Bridge* that hath rendered our roadway much

smoother,

And the stewards, who our ministering spirits have been,

May we drink in another.

Through the voyage of life may we brave every ill,

Feeling stoutly prepared to face rock, shoal, or weather

And when in Eternity's haven we're moored,

May we greet one another! |

*The purser's name is Bridge.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

A YANKEE DONE "SLICK."—AB'S SECOND LETTER.

At Will o' Jimmy's, Paterson,

New Jersey, May 7th, 1880.

OWD

TULIP!—I've bin a day or

two tryin for t' collect my thowts an' my wits an' my recollections

together, an' made a very poor hond o'th' job. They keeper

whizzin about me like a swarm o' vexed hummabees, ut winno' be

driven into their cote. Do what I will I conno' think ut

thou'rt far off me. When a branch of a tree maks a patterin

noise at th' window I turn round, thinkin it's thee come'n a-axin me

if I've a penny for th' sond chap. Then I soik, an' think

about big waves, an' James o' Joe's loom, an' Sammy o' Moses's, an'

that everlastin "Nap." Then I see a stretch o' green wayter,

changin into blue, until it gets pieced to th' sky, an' so'dert

round wi' a dark seeam. But th' idea ut I'm above three

thousand miles fro' wheere I know thou'rt sittin, thinkin about me,

I conno' gawm at o.

How I geet here is a puzzle to me. I con just recollect

stondin by a wayter side ut I reckon must be th' sae, an' some sort

of a ship wi' a big hole at th' end, an' driven by an "owd Ned"

engine ut worked on th' top outside, comin plashin to'ard me.

I recollect, too seein hoses, wi' carts at their tails, gallopin

into that big hole. Then seein th' lond leeavin me at one

side, an' comin nary me on th' tother, an' Sammy draggin me into a

railroad carriage as long as our fowt, an' tellin me I should be

oather kilt or drownt if I didno' give o'er starin at women. I

think I yerd him say ut we'd crossed a ferry. An' now it comes

to my mind our londin at New York th' last Sunday. I wonder if

it's wi' gettin o'er too mony "Stone-fences" ut's bothered me a bit.

They're wurr than as mony doses o' owd Bell whisky, speshly when

they're mixed up wi' young icebergs.

One never knows wheere trouble is to be met, nor when there's

a chance o' losin th' seet on't. Sae sickness is bad enough,

but there's sich a thing as lond sickness, an' o' th' two it's th'

wo'st. At th' time I should ha' bin coodlin wi' thee, an'

bargainin for a "Jacky" tae, I stood like a lost donkey under a

shed, waitin t' ha' my what they co'en "baggage" examined.

This wur one o' thoose trials I wurno' prepared for, becose I didno'

expect my bit o' stuff would ever be noticed. If I'd thowt it

would ha' to be overhauled I shouldno' ha' browt that pair o'

thou-knows-whats, thou sent as a present for Mary at thy uncle

John's dowter. Lors a mercy, Sarah! When I seed a chap

maulin among Sammy o' Moses's shirts, an' knowin it would be my turn

next, an' a crowd o' folk watchin, I went as sick as if I'd bin i'

love. I knew th' mon mit be sure they wurno' for my wearin.

Just at th' last minit I bethowt mysel of a plan for throwin th' mon

off his guard. I fished up that box thou gan me, ut's like a

book, an' laid it th' topmost. I knew there'd be some fun when

it wur oppent, an' thowt th' mon would get so laafed at ut he'd look

no furr. But it taks a clever chap t' dodge a Yankee. It

coome to my turn at th' last, an' I could see Sammy's shoothers

shakin, an' his face covered o'er wi' waves o' merriment. I'd

towd him what there wur among my baggage.

This custom's officer, as they coed him, wur a tall, lanky

chap, wi' a hont like a bent gridiron, an' he coome clawin at my

"work-box" like th' owd 'Meriky aigle does its pearch, as we seen

pictured everywheere.

"Nothing here only for your own use?" th' mon said, as he

lapt his fingers round th' box.

"Nowt ut I'm aware on," I said. This wur th' fust lie

I'd towd i' Yankeeland.

He wouldno' tak my word, noather, but oppent th' box. I

dar'say he expected findin a lot o 'jewelry an' stuff, an' ut I

should have some dollars for t' fork out. But I dunno' think

th' mon wur ever so gloppent in his life. That ballis-leather

face of his went like as if it had bin newly-damped for stretchin,

an' ther cracks o' laafin went off, like shots at a sham-fight.

He turned th' things o'er as soberly as he could, but a hen could

ha' done th' job as weel. It wur a study for t' watch his lips

mutter—

"Four rows o' pins; one paper o' needles, two bobbins of

cotton—white and black; two stocking needles; one ball of worsted;

one pair of scissors; one pair of spectacles; one dozen shirt

buttons; four pants; one knot of tape; one bodkin; piece of watch

spring; tailor's thimble; tooth brush; star watch-key; box of pens;

two holders; two pencils; rubber; beeswax; boot laces; Cockle's

pills."

"Has he bin gooin through thy museum, Ab?" Sammy o' Moses's

shouted as weel as he could for chinkin.

"Ay, I've letten him in beaut payin," I said. "He's on

my free list."

We cleared eaut o' that owd barn, for it looks like one, or

moore like owd Williamson's show ut used to come to Hazelw'th at a

wakes,—an' I set my foot for th' fust time upo' gradely 'Meriky lond.

"Let's goo an' have a lager," Will o' Jimmy's said.

An' he motioned to'ard a buildin ut looked like a public-house.

"What's a lager?" I axt him.

"A sort o' ale ut doesno' mak 'em drunken," he said. "Thou'll

smack thy lips when thou's tasted. If yo' drank it i' England

yo'd goo a straighter road whoam than yo' dun, an' not abuse yo'r

wives as mich. Thou'll like it, I con tell thee."

We hadno' mony yards for t' goo to th' corner o'th' street

wheere this house stood; but, lorgus, Sarah, I thowt I should ha'

brokken my neck afore I'd getten theere. Talk about pavements!

If thou geet thy foot i' one o'th' ruts o' New York thou'd shout o'

someb'dy for t' lift thee out. Owd Thuston's cow-lane after a

frost, an' snow, an' rain, an' a week's cartin stuff for t' put on

th' meadows, would be a love-walk i' comparison. A Yankee

never crosses without gooin round by th' crossin stones. A "Britisher's"

known by his takkin a slantindikilar cut, an' getten his feet fast,

or his ankles thrown off. I managed to flounder across without

any greater misfortin than rippin a gallows button off; an' we shot

through a dur-hole ut wur guarded wi' nowt nobbut a little pair o'

wickets made out o' yeald shafts, an' hung about th' middle way

between th' top an' bottom. Th' place wur summat like a

Manchester vault , an' we had to stond up at th' keaunter.

"Four lagers," Will o' Jimmy's said. They sound th'

word as if it wur spelt "lawger."

When th' glasses were smashed on th' keaunter—they dunno' put

th' things down quietly—th' stuff looked like bein o froth; an' I're

feart o' dippin my nose in it.

"Come!" I said; an' a chap at th' fur end o'th' "saloon "

said—

"Do!"

Everybody pricked his ears at yerrin that; and i' hauve a

minit ther sich hond-shakin as I ha' no' seen for some time.

He proved to be a Glossoper; an' had nobbut bin i' New York for a

two-thri months. That afternoon hardly looked like Sunday when

we parted. But ther no hurt done ut I know on.

Lager winno' mak folk int' foos. But when folk o'th' same

kither meeten i' forrin parts they like, go'en off it for a bit.

Well, lager's nice drinkin; an' th' Yankees moppen it up like

Ralph Bailey's pig did its swill. If they did as mich o'th'

owd Bell tiger they'd never be wakken, sayin nowt about bein sober.

When we'd had our fill we set off to th' Metrolopitan Hotel, where

th' fust things I seed when I geet i'th' lobby wur our baggage.

Sammy o' Moses's had had it checked on to theere while I're botherin

wi' th' Custom House chap. Sammy's a good deeal t' onswer for,

as thou'll see. But moore of our dooins when I write again.

Keep thy pecker up, owd wench!—Thy snivellin foo.

AB.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER IV.

NEW YORK AND NEW YORKERS.

AB'S THIRD LETTER TO HIS WIFE.

Same Shop as before,

May 10th, 1880.

OWD

THIMBLE-"SLINGER,"—I'd

yerd so mich ut wur noane so good about New York, an' th' folk ut

liven in it, that I felt rayther wakken, if no' lively, when I fund

I'd thrown my lot in among 'em. I fancied I could see a pistil i'

every men's pocket ut I met, an' murder in his face. If I yerd a dur

bang i'th' hotel, it wur a shot; an' a shufflin o' feet i'th'

lobbies wur th' carryin of a corpse to his chamber. These fears I couldno'

get rid on for mony a day; an' seein a darkie grinnin

beheend me every time I turned round wur sure to bring on a mild

sort of a fit. Ther four on us t'gether ut, like, coed oursels

chums. But what could we ha' done in a row when we carried nowt

about wi' us harder than our fists? It's keawrdly feightin, feightin

at a distance.

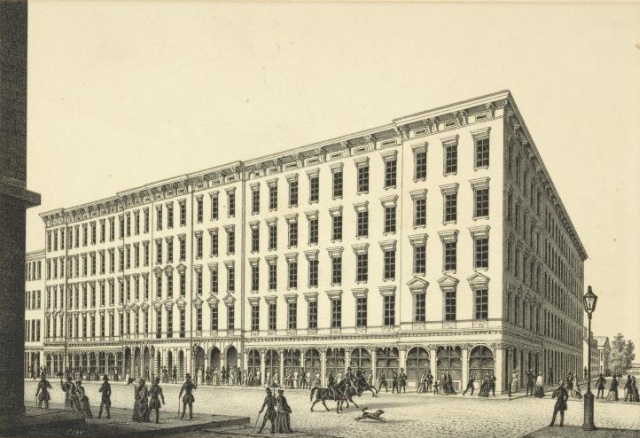

|

|

|

Metropolitan Hotel, New York. Opened 1852, demolished in

1895.

Source: New York Public Library.

|

"Niblo's Theatre, or as it

is generally called, "Niblo's Garden," is

situated in the rear of the Metropolitan

Hotel, with an entrance on Broadway.

It is one of the largest and handsomest

theatres in the city, and by far the coolest

in warm weather. It is devoted

principally to the spectacular drama."

"Lights and Shadows of New

York Life"

by James Dabney McCabe,

1872. |

|

Dear a-me, Sarah, what a place that Metrolopitan (sic) Hotel is! Fairly bewilderin to a yorney like me. It's three front

durs to it: an' if

a chap doesno' mind which he goes in at he may go slap into a

theaytre. I missed my road th' second neet; an' becose I couldno'

show a ticket I're ordered back. I thowt it wur a queer hotel if

they had to ha' tickets for t' goo in with. However, I went into th'

street, an' made a fresh start. I thowt I happen mit ha' getten to th' wrong shop. But I hadno', I're at th' reet pleck, but had gone

in at th' wrong dur; an' somehow couldno' get reet wi' my turnins. Th' second start londed me; but through a side dur I could see th'

mon ut turned me back. It wur th' blaze o' leet there wur ut I

believe threw me wrong. It wur summat like owd Jammie at Abram's, ut

wur so used to gooin t' bed without candle it bothered him to find

th' road when it wur moonleet.

Th' fust thing ut wur done at us when we geet to this hotel wur

shuttin us up in a cage ut they coed th "elevator," while th' hotel

sank down three storeys. When they leet us out they showed us our

sleepin shops. I've wondered sin' why they couldno' ha' wund us up

i'stead o' lettin th' buildin sink down.

When we'd looked at our beds, an' relieved our faces of a day's

dirt, we geet into this cage again; an' th' hotel wur wund up. If an

Englishman had planned that, we should ha' bin wund up, an' letten

down i'stead o'th' hotel. But what con they expect out of a wooden

nutmeg? We'rn shown into a room wheere a black mon took our hats,

an' put 'em on a shelf; then we went into a bigger shop ut wur

filled wi' tables, an' blacks wi' white senglets.

"What is there t' be done here?" I said to Sammy o' Moses's, ut had

howd o' my hont, for fear on me bein lost.

"We're gooin t' have a bit o'baggin," Sammy said.

"But what are o these Sambo's dooin here?" I axt.

"They're Christy Minstrels," he towd me. "They're gooin t' sing for

us while we're feedin."

"What, o'th' Sunday neet?"

"Oh, it maks no difference here. If it goes under th' name o' 'Sacred Music,' owts reet fro' 'Yankee Doodle' to 'Bob an' Joan.'

If thou'll goo i'th' next street thou'll see a shop wheere young

women singers are donned i' very nee nowt, singin sich like songs as thou'll yer any neet at th' Alick. An' thou'll see it printed up at

th' dur 'Sacred Music on Sundays.'"

"Sammy," I said, " is that so?"

"Ay, that is so," he said. "Thou may see for thysel if thou's a

mind."

"Dear-a-me!" I said, "wheerever we go'en to this wo'ld is full o'

shams."

We'd getten oursel's "fixed" at a table; an' two niggers wur doancin

about us like a couple o' barbers.

"Dinner, or tea?" one o' these sons of a coal-hole axt me; an' he

showed me a card.

"Dost think we'n reaum for a dinner?" Sammy said.

"If ther a potato pie on th' table, calkilated for four, I could fix

about th' hauve on't," I towd him.

"Then we'n ha' dinner," he said. "What dost think thou con fancy?"

an' he looked at his card.

I looked at mine; an' tried to fumble my road through this list—

|

Windsor a la crême.

Consomme Brunaise au pâte d' Italie.

Baked shad farcie, au finis herbs.

Turkey aux concombres a la poulette.

Beef a la mode a I' allemande.

Blanquet of veal á la Toulouse.

Macaroni á la Solferino au jus. |

I went no furr, becose I're out o' my depth for a start.

"Try that second on th' list," Sammy said, seein what a stew I're

in. I'll tell thee what, Sarah, I swat wur than if I'd bin in a hay

meadow; for th' place we'rn in wur like a oon. They han it made wot

so ut folk conno' ate so mich.

"But what mun I ax for?" I said. "These 'Meriky words are too big

for my mouth."

"It's French," Sammy said. "Everybody ut comes here is supposed to

understond French."

"Thee ax for me, Sammy, that's a good lad." So he said summat like

this, but I'll not be sure I'm reet—

"Kong-so-mai Brungay o paut Italie."

If I'd had to say that I should ha' brokken my jaw, or getten my

tongue teed of a knot. But I never tried. While the mess wur i'

comin I spekilated as to what it would be like; but when it wur

pushed under my nose I felt reet. Whether it wur broth, or soup, I

dunno' know, an' little I cared so ut th' smell wur reet. I polished

it off like winkin, an' sit starin again.

"Baked shad farcie," I said, so as to show ut I wurno' sich a

gaumblin as I looked.

That I fund wur a nice bit o' fish stuffed wi' yarbs; an' I licked

my lips at it. Then I went down th' list, pointin what I wanted out

to th' blackymoores; an' geet

through it that road. Just as I're scrapin up I yerd a fluffin

noise; an' at th' same time ther a flash like leetenin. It wur th'

gas lit by electric wire. It made my inside jump, it coome so

sudden. Ther mony a hundert leets; an' I could see moore o'th'

company than I cared to see. Ther blacks without end; an' one or two

would stond o'er me while I're atin, as if they'rn feart of a knife

an' fork, or a spoon gooin out o'th' seet; an' I fancied their clooas had bin mixed up wi' a hamper o' onions. I gan one a hint ut

he'd better be gettin his music ready, as I're just windin up my

affairs, an' could do without him. Sammy said summat to him, an' he

shot off. But i'stead o' stoppin away he coome back, an' browt a

long-necked bottle wi' him, wedged in a bucket o' ice. When th' cork

were drawn ther a sound rumbled among th' glass shades like a bit of

a anthem. That wur th' sacred music ut Sammy wur thinkin about.

It wur a sort o' music I didno' object to if it wur good Sunday. I'd yerd

a strain or two on it before; an' when I'd tasted on't, it

like reconciled me a bit to Yankee life. When we'd done a

comfortable housin I stroked my senglet down, an' said I're ready

for owt obbut a bullet. It would be a pity if a piece o' leead

should disturb th' serenity o' my feelins. But Sammy made a bit of a

row under my waistcoat without a bullet, after he'd axt me—

"How did t' like that Kong-so-mai Brungay?"

"That wur th' fust looad, wurno' it?" I said.

"Ay, th' fust."

"Well, it wur middlin good; an' thoose bits o' flesh ut wur in it

wur tasty. But I'd rayther have a basin o' gradely leg stew, an'

some toasted wut-cake, an' a coolish mornin."

"Some folk would rayther have it than green fat."

"Well, th' taste isno' mich unlike it."

"It shouldno' be," Sammy said. "Ther's no' so mich difference

between a frog an' a turtle."

"What dost meean by that?" I said.

"Well, if there is any difference a turtle is th' ugliest o'th'

two," Sammy said.

"Wheay, what has a frog to do wi' that soup?"

"It gives it that nice flavour. If it hadno' bin for frogs' legs

thou wouldno' ha' cared for it."

"An' wur thoose bits o' flesh frogs' legs?"

"Just that bit o' fillet inside; that's o. They dunno' put th' whul

leg in. Folk would find out what it wur if they did, an' mit no'

care for atin th' stuff. Drink thy glass up, an' let's goo out. I

see there's summat up wi' thee."

An' there wur summat up wi' me, too. Th' idea on me atin frog soup

made me feel as I felt a time or two on th' sae but a glass o'

lemonade, sucked through a straw, sattled me, an' th' ship gar o'er

rowlin. After o, th' soup wur nice takkin. I shall remember th' name

as long as I live—"Kong-so-mai Brungay." I've wondered mony a time

sin' if Sammy wur havin me on, becose I catcht him laafin as we'rn

gooin out. How that nigger ut took our hats could sort 'em out fro'

amung about forty is a marvel to me. But he laid his honds on 'em at

once. I couldno' ha' piked my own out without tryin three or four. He'd be a useful chap at a buryin, that darkie would.

"How soon dost think we shall be shot at?" I said to Sammy o'

Moses's when we'd getten on th' swing, an' put on that swaggerin

look ut nob'dy nobbut a "Britisher" con do, when he wants to let

folk know whoa rules th' waves.

"Oh, there isno' so mich o' that sort now as there used to be,"

Sammy said, as if he felt quite comfortable about things. "I conno'

yer ut they knocken above a dozen a day o'er now."

"Getten down to a dozen a day, han they?" I said; an' I looked

round for t' see if ther owt pointed at us.

"An' that bit o' execution's chiefly done i' one street, an' ov a

Sunday neet," Sammy said.

"What street's that?" I axt.

"Th' Fifth Avenue; we're gooin theere."

"Hadno' we better put it off till some other neet?" I said. "We ha'

no' seen mich of Ameriky yet; an' it happen mit hinder us."

"If thou'rt feart thou con walk th' fust. They aulus shooten 'em

i'th' back," Sammy said.

"It isno' becose I'm feart," I said. "But if thou geet shot I

should be lost." Th' tother chaps had gone another road. They'd a

bit of an objection to gooin into th' target bizness. So had I. But

I thowt I'd show a bit o' sham English pluck, if I'd noane o'th'

real stuff.

"Ab," Sammy said, wi' that twinkle in his een ut thou's seen mony

a time, "thou'rt an' owd humbug!" I darsay thou thinks th' same; but if

I am, I'm thy lovin "humbug." AB.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER V.

A CITY OF THE DEAD.

HOTEL life is one

of the institutions of the States. The "Delmonico," the "Aster

House," the "Metropolitan," and the large establishments in and

about Madison Square, are so many temporary homes for the swarming

population of New York. In these places the élite of the city

spend their Sundays, and in many instances the evenings of week

days. The large dining rooms are so arranged that each family of

boarders can sit round its own table, without forming more than one

isolated section of the assembly. The ease and nonchalance displayed

by each person, whether pater or mater, or the

youngest of both sexes, strikes you as being the result of familiar

acquaintance with such kind of life. Why they prefer spending their

Sundays and evenings in this manner is variously accounted for. One

reason given is the love of show. If Materfamilias has a daughter

not too plain to take out, she dresses her for this market, as the

farmer would the occupant of his shippon. And the Yankee ladies can

dress. It is quite essential to a passable appearance that they

should. Put one of these fragile creatures inside the garments of

some of our would-be-fashionable people, and what a sorry figure she

would make. What nature has left short in her work, silks and

jewellery have to make up.

Another reason advanced is that the American women are either

too lazy, or too much indulged, to attend to culinary matters when

an extra dinner has to be provided; and the hotels can supply such

wonderful varieties. The cost is not allowed to be a

consideration. Cheeseparing enters not into the calculations

of a son of the west when the requirements of the dear bit of skin

and bone that claims to be flesh of his flesh have to be attended

to. Be it in the purchase of rags, or rings, or refreshing

meats, the "bottom dollar" is ever ready to be called forth; and

there is nothing more striking in American life than this slavish

indulgence shown by men towards their wives. There is scarcely

a woman to be met that is not ringed to her finger-nails; and the

labour bestowed upon her toilet is a proof that very little time is

spent on anything else. There is a saying that "America is

heaven for women, but another place for men and horses;" and the

truth of this axiom, so far as my experience goes, I can verify.

But more of this in future chapters. I have to deal with our

friend "Ab" at present.

|

|

|

A fashionable promenade on Fifth

Avenue (1872).

Source: New York Public Library. |

The "philosopher of Walmsley Fowt" took special interest in

the various traits of character which distinguish our American

cousins from our kinsfolk at home; and in the matter of hotel life,

and the manner of "feeding," he was peculiarly at issue. He

pronounced both to be "strong weaknesses," that would imperil the

strength of their national life. His experiences in this

direction were to him a source of anxiety and misgiving, which found

expression in his characteristic style.

"I dunno' like th' thowts on 'em gooin' again th'

wall," he would say in a serious mood, "for they'n some of our blood

in 'em, thoose that han any blood at o, an' are no' like corks, or

dried apples. But watch 'em ate! No mon could do justice

to a bit o' beef if he never takes his nose six inches fro' th'

plate. If it's a bit towgh—an' some on't is none so very

tender—it must go down his throttle in a lump. Look at that

mon," he remarked, pointing to a spare individual whose knife and

fork were in exceedingly active movement; "what must be th' state of

his inside after sich housein as he's dooin? I seed a sarpint

havin its dinner once, an' I could watch th' one lump it swallowed

go slidin down to'ards its tail like a slow boat in a tunnel.

I con see it goo down yond mon's throat just th' same. His

neck must be made o' indy-rubber, or elze it wouldno' stond th'

ratchin. An' what good will it ever do him? I reckon

he's etten o' that fashin ever sin' he could hondle his tools , an'

look at him! Sammy, here, could double him up an' shove him

through that stove-pipe hole; an' he's etten very nee as mich as th'

stove would howd. Wheere's it gone to? When a mon delves

into a potato pie, an' leeaves reaum for th' steam to get out, he'll

side his mess in a thowtful way, as if atin wur a pleasure not to be

getten through in a hurry. An' he'll now an' again rear back

in his cheear, an' stroke his senglet down comfortably, like as if

his soul had summat to do with it; then, swiggin off his pint at th'

finish, would say 'theigher!' He'd rise fro' th' table like an

Englishman, ut had some thowts of another day; but yon mon would

have his face scauden before he could get to work gradely. Eh,

my!"

"Like stuffin blackpuddins," Sammy o' Moses's observed.

"Thou's just hit it, Sammy," said Ab; "for o th' wo'ld like

ladin in thoose lumps o' fat, an' fillin up wi' thin stuff. If

yond mon wur cooked like a rappit they'd ha' to put him i' th' oon

skin an' o. There'd be nowt nobbut summat like a long basket

beside. An' what con a country stond ut feeds itsel o' that

fashion? A generation or two would see it jiggered up if it

wurno' for th' fresh blood ut's bein sent into it. Fifteen

hundert folk we browt wi' us across th' sae; an' welly so mony are

comin every day for t' keep th' stock up. Th' childer o' these

'll begin a-suckin gum an' candy afore they con walk. Then

when they'n bin lengthened out, like pooin a sugar-stick, they'n

begin a-swallowin their mayte whul, an' chewin bacco i'stead.

That sort o' feedin winno' mak muscle; an' what con a country expect

to come to when thoose ut should be its props are nowt nobbut bags

o' sawdust? If we'd this country, Sammy; or they'd let us have

a bit o' their grand sky, we'd show 'em a different dub. We'd

ha' summat elze beside wrinkles at th' back o' our ears; an' about

five yures hangin at one's chin. I dunno wonder at 'em shootin

one another i'stead o' gradely feightin. If they wur t' have a

go at our sort there'd be a noise like a crash o' paesticks when

they went down. An' their women, Sammy! Well, they conno'

help bein not o'th' prattiest; but if they'd get some o' owd Shaw's

sort o' energy reviver, a good 'eish plawnt' (ash plant); an' let 'em

ha' middlin strong doses on't between mealtimes, they'd mak 'em t'

stond o' their feet a bit moore than they dun. They'd find

summat for their fingers t' do, too, than aulus bein hooped round as

if they'rn cracked. There's plenty o' wark for a good

skoomester wi' a heavy hont."

"But thou munno' put 'em down as bein o' alike," Sammy said.

"I've seen a difference."

"So have I," replied Ab; "but the prattiest an' best ha' no

bin born here. Thoose ut are th' latest fro' th' owd sod are

th' moost like gradely women. I con tell one as soon as I see

her. Hoo doesno' walk on her toes, an' hoo doesno' wear two

sets o' rings—one for her bare fingers an' th' tother for her hont

when it's getten its leather clooas on. Nor hoo hasno' that

kerly-merly yure petched i'th' front of her yead, like th' orniments

round a lookin-glass. Thou remembers thoose women we seed at

Paterson, Sammy?"

"Ay, I should co thoose a gradely sort," said Sammy.

"Just so," said Ab. "They're no moore like these white-livert

buzzarts than a chawk image is like flesh an' blood. They'n

some bant about 'em, thoose han, an' fit to be th' mothers of a

young nation. Beside, they'n lost noane o' their English

prattiness, an' they are no' feart o' wark. I believe it's

nowt nobbut their mardness an' their way o' livin ut causes these

New York dolls to be so mich like faded waxwork, ut's been melted

down for any sort of a face, fro' a queen to a mermaid. If

they'd live gradely, an' be gradely, an' do their share o' wark like

other women, I see no reeason why they should no' be as pratty as

thoose in New Jarsey. Does thou?"

"Nawe; gradely wark an gradely livin has made our English

stockin-menders what they are," Sammy said. "But if we begin

a-pamperin 'em—"

"We're done for," concluded Ab, with a fist emphasis on the

table. "Candy an' monkey nuts—never!"

These remarks ended the conversation; and we adjourned to

make preparations for seeing two of the finest sights to be seen in

the world, the Cemetery at Brooklyn, and the Falls of Niagara.

To a stranger New York is a prison. He cannot get out

of it without crossing a ferry at one point or other. Enclosed

between the two forks of the River Hudson, which take the names of

the North and East rivers, it is completely surrounded by water; and

a person who wishes to cross to a certain point finds it exceedingly

difficult to hit upon the right ferry. We were in a continual

"fog" all the time we were in the city; and sometimes travelled

miles to find ourselves at the wrong place after all. On one

occasion, having been by accident separated from my companions, I

found myself at Jersey city when I imagined I was at Brooklyn.

And at another time, we were landed at the Pennsylvania Railway

Station, when we ought to have been at the depot of the Erie line.

Once get wrong, and the difficulty in getting right is ten times

greater than when starting from Broadway as the centre.

It happened to be Sunday when we crossed to Brooklyn.

Had it been Saturday we might have been groping about the streets

the whole of the day, and possibly have been landed at the wrong

place as a reward for our pains. The scarcity of traffic on

the Sunday helped us over our difficulties; and we only made the

mistake of landing at the wrong part of Long Island, upon which

Brooklyn is built. A few changes of street cars; any number of

inquiries; the annoyances of the exact five cent. fare, neither more

nor less, to be dropped in a nick; a few cross purposes, and a great

deal of strong language, and we reached the destination we set out

for.

We were hospitably entertained by a family of Newton Heath

Americans, the head of which has lost none of his Lancashire

idiosyncrasies; and after our bodies and our tempers had been

somewhat cooled by ablutions of lager, applied inwardly, we took a

car for Prospect Park and Greenwood Cemetery, our entertainers

accompanying us.

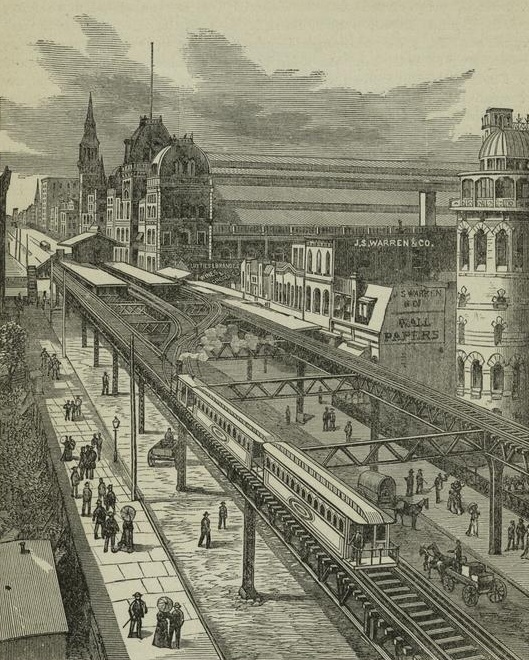

|

|

|

New York elevated railroad near Grand Central Station

(1889).

Source: New York Public Library |

You seem to breathe a freer and fresher atmosphere in

Brooklyn than you do in New York. In the latter city you feel

oppressed by the height of the buildings, and the many

contributories to the dangers of the streets whilst the abominable

stink given out by one of America's greatest sources of wealth,

petroleum, pervades everywhere. Our friend Ab said it was

"like following a foomart o t'gether." As regards the street

dangers, the "Walmsley Fowt philosopher" had a startling experience

of them the day before. We happened to be passing along a

street, the middle course of which is canopied by an iron network in

the form of a branch of the "Elevated Railroad;" a delightful

structure regarded from a tradesman's point of view, as it prevents

the sun from spoiling the goods in his windows, and would-be

customers from entering his door. We were dodging as well as

we could the tramcars and other traffic below, when our attention

was called to the dashing past of a train of cars over our heads.

This would have been sufficient of itself to have alarmed us; but

when it was accompanied by a yell, and the pouring forth of a

torrent of language that could only be printed in dashes, the

excitement was doubled. Ab had got his fingers in his collar;

and the way in which he was tearing at it was suggestive of his

having a wasp, or more probably a mosquito, in active work there.

"What's up now, Ab? Is it bitin?"

"Bitin be—dashed!" he exclaimed "it's takken a piece out, an'

part o' my collar."

"It must ha' bin an owd dog, then it's never been bred this

summer. It wouldno' ha' had its teeth set."

"Teeth set, eh? I didno' know ut a cinder had teeth."

"Wheay, isno it a miss-kitty?"

"It's moose like a fizz-kitty, for it's bin fizzin i'

my neckhole. I wish I'd howd o' that infernal Yankee ut

invented these sky railroads. I'd crom a red wot cinder wheer

he couldno' shake it out in a hurry—that I would. I'd mak him

sing 'Yankee Doodle' wi' variations, an' doance to his own music,

too."

The reader will easily infer from these explosions of temper

on the part of Ab that the cause of his suffering and pardonable

wickedness was a cinder that had dropped from the engine on passing,

and found a lodgement beneath his bump of philoprogenitiveness,

where it was reluctant to be disturbed. These elevated

railroads are a great nuisance in many ways, and not likely to be

adopted in England.

By this time we had arrived at Prospect Park, a large tract

of well-wooded and well-watered land, which calls for no especial

remark when we consider that we are in near proximity to the sight

of all sights to be seen on Long Island. After resting

ourselves on a piece of the higher ground, which commanded a view of

many miles of land and sea, and from which we could observe the

constant and swallow-like flitting to and fro of the ferryboats that

ply in the Sound, we prepared the tone of our thoughts and feelings

so as to accord with the character of the place we were about to

visit—the "City of the Dead"—Greenwood Cemetery.

It were not fit that we should approach the place in a

buoyant and joyous spirit, although the bloom of the dogwood tree

sheds light and loveliness on a scene where Beauty had made her home

ere the florist's spade, or the sculptor's chisel, essayed to make

what seemed perfection even more lovely. The shadowless noon

is past; and the sun in its westering glory picks out with purest

gold the marble chasteness of the blossoms which droop

sympathetically over kindred stone that marks the spot where heroes

sleep. Here, stealing among the fretwork of light and shade,

the ghostlike form of a woman arrests our attention. In

deepest black she is attired; and now she pauses at a wicket-gate

that leads to a "plot" in which a small white headstone is the

central object. She kneels, and trims the flowers growing on a

mound near the stone. Perhaps her little one lies there; and

she can fancy the spirit of one so loved is hovering among those

sweet emblems of a sweeter soul, and her fingers yearn to fondle

among them. No; her soldier husband sleeps in his death

bivouac beneath that turf, and he fell in defence of his country's

unity. Honour to his name, although it may be among the

nameless! And now other sisters are seen kneeling at similar

graves, a mournful host. If the prayers which I can imagine to be

articulate on their lips are heard, slavery can never again

overshadow that glorious land.

|

|

|

Green-Wood Cemetery, opened in 1838, is now a

National Historic Landmark.

Source: Wikipedia. |

We drive about for miles, forgetful of the character of the

place we are visiting, for it seems too lovely for a tear to be shed

near it. If the dead are there we feel not their presence,

only as though they were with us in the flesh, but a purer flesh

than we know. Two hundred thousand soulless tenants inhabit

these quiet homes, and there are half-way resting places for bodies

to find a temporary shelter when frost or snow prevent the strongest

builder of all from completing his edifice. See Greenwood

Cemetery, and learn to love without tearful regret, is the

benefaction of one heart that is not unacquainted with the deepest

sorrow.

――――♦――――

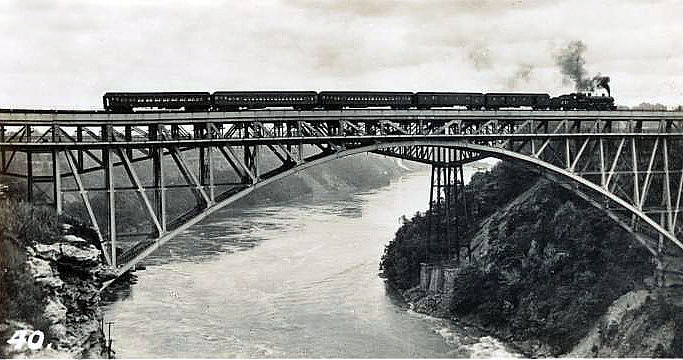

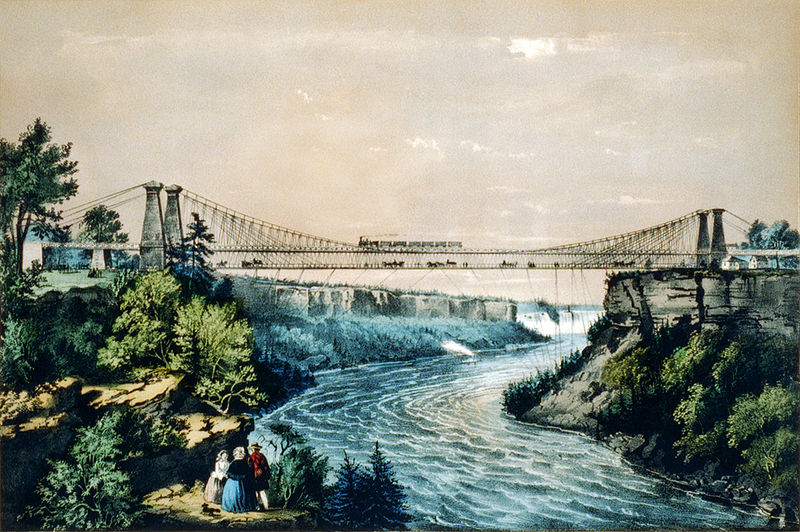

CHAPTER VI.

ON THE WAY TO NIAGARA―AB'S FOURTH LETTER TO HIS WIFE.

Queen's Hotel, Toronto, Lower Canada,

May 16, 1880.

SARAH,—As it's

Sunday I'll co thee by thy Sunday name, an' not "Owd Ticket," or

summat o' that sort. Sin' thou yeard about me th' last time,

lorgus me, what a lot o' ground we'n gone o'er! I should think

we're very nee tumblin off th' edge o' th' wo'ld. I dar'say

thou'll want to know how I am i' health, as it leaves me at present;

an' whether I've bin bitten wi' owt or not. I may tell thee

I'm o reet, as far as flesh an' booan are concarned. But my

"husk," as owd Jack Robinson used to say, has bin a bit damaged.

It reminds me now an' again ut I'm mortal, an' subject to mortal

ailments, not o together brought on by my own dooins. I've had

a bit o' bad luck lately wi' th' hangin quarter—my neck, as thou'll

understood. A rope round it would hardly feel comfortable just

now. Last week I're bitten wi' a cinder ut fell out o' th'

engine fire of a sky railroad i' New York. I wish I'd howd o'

th' mon ut invented that neck-or-nowt way o' travellin. He'd

be roughly dealt with, I con tell thee. I'd crom a cinder, an

a big un too, wheere th' owd pa'son had th' hummabees. Sammy

o' Moses's winno' believe ut a cinder would drop out o' th' engine,

an' just leet i' my neck, as if my collar wur a dust cart. He

says I must ha' bin i' some hesshole, or other, somewheere.

For t' show thee ut that couldno' happen I may tell thee ut there

are no hessholes i' Yankeeland; so I couldno' tumble i' one; an' I

should ha' moore sense than wrostle a stove pipe, even if it wur

winter, an' it's anythin but winter just now, tho' I've bin welly

starved to deeath within th' week. I'll tell thee how that

happened e'ennow.

Last Sunday we went across th' wayter i' one o' thoose "owd

Ned" beats to the "city o' churches," that's Brooklyn; wheere

Beecher an' Talmage, as thou's yerd spake on, makken folk be good

again their will. Theere I seed one o'th' grandest seets ut

ever thou seed i' thy life, tho' thou's seed many a one, not

forgettin a merry meal or two, an' th' babby's frock ut a kessunin,

beside a hoss race, an' a henpecked club procession. But my

"boss" tells me he's been writin about that, an' if I trespass upo'

his ground he'll hommer me. But there's one thing he tells me

he hadno' mentioned, a mechanical cow. That's an animal of a

breed thou's no' seen i' England. I'm noan hintin at th' pump,

but a gradely cow, an' one ut would let thee milk it without strikin

out, or showin signs ut it ud mak its yead int' an "elevator," an'

gie thee a lift. We'd gone to a place they co'en Coney Island;

that's at th' top end o' Brooklyn. It's a sort of a place like

Blackpool, or New Brighton, or Daisy Nook if ther any sae theere;

obbut ther no lodgin houses nor wot wayter shops. There's nowt

nobbut th' sae, an' a lot o' atin an' drinkin places, an'

photorgraph chaps, beside th' average number o' yorneys, ut one sees

everywhere.

These atin an' drinkin shops dun a good bizness when th'

weather's wot, an' they'rn gettin ready for it then. I'd

noticed a cow stondin very quietly by itsel. It had nobbut

three milk jets. Sammy o' Moses's said it had lost th' tother

wi' havin th' milk feyver. I wonder how he knew ut it had had

it. Considerin ut ther no pastur theere, I wondered how it wur

ut it would stond so quietly, an' let anybody milk it. I said,

"Cope, wench," same as Peggy Thuston used to talk to 'em! but it

never stirred nor mooed. I wondered then if it didno'

understond English; or if ther sich a thing as a cow bein deeaf an'

dumb. While I stood theere, a young woman coome a milkin it.

Hoo swirted out two glasses full but when hoo tried a third it coom